Note to reader:

Because Puerto Rico is part of the United States, for the purposes of this article, the initialism “US” is being used to refer only to the 48 contiguous states, Alaska, and Hawaii, not including Puerto Rico or any of the other insular areas of the United States; all references to Puerto Rico are considering the island as a discrete region, and not as a part of the United States.

Introduction

Puerto Rican patients

Puerto Rican patients who live in Puerto Rico are socioeconomically disadvantaged relative to Puerto Rican patients living in the continental United States (US) and Hawaii (the totality to be referred to from here forward as the “US”); the island has a higher poverty rate, higher unemployment, and lower levels of educational attainment compared to the US (Morales et al., Reference Morales, Lara, Kington, Valdez and Escarce2002; Proctor, Semega & Kollar, Reference Proctor, Semega and Kollar2016; Perez & Ailshire, Reference Pérez and Ailshire2017). The relatively disadvantaged social and economic position of Puerto Rico suggests that Puerto Ricans residing on the island have more socioeconomic risk factors for poor health than do their US counterparts.

Low mental health care utilization among Puerto Ricans and other Latinxs has been reported in the literature (Jimenez, Cook, Bartels & Alegria, Reference Jimenez, Cook, Bartels and Alegría2012; Gellis et al., Reference Gellis, McGinty, Horowitz, Bruce and Misener2007; Taylor & Irizarry-Robles, Reference Taylor and Irizarry-Robles2015). The literature also suggests a system with barriers to mental health treatment for Latinxs that includes cost of care/lack of health insurance coverage, limited time with providers, low knowledge about resources, and lack of linguistic and culturally competent services (Anastasia and Bridges, Reference Anastasia and Bridges2015; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Bruce, Koch, Laska, Leaf, Manderscheid, Rosenheck, Walters and Wang2001; Rubenstein et al., Reference Rubenstein, Jackson-Triche, Unützer, Miranda, Minnium, Pearson and Wells1999; Ruiz et al., Reference Ruiz, Aguirre and Mitschke2013; Shattell et al., Reference Shattell, Hamilton, Starr, Jenkins and Hinderliter2008; Uebelacker et al., Reference Uebelacker, Marootian, Pirraglia, Primack, Tigue, Haggarty, Velazquez, Bowdoin, Kalibatseva and Miller2012; Vargas et al., Reference Vargas, Cabassa, Nicasio, De La Cruz, Jackson, Rosario, Guarnaccia and Lewis-Fernández2015).

Despite historically poor social and economic conditions, however, Puerto Rico may provide a more supportive context for cancer coping than does the US (Crimmins, Garcia & Kim, Reference Crimmins, Garcia and Kim2010). Puerto Ricans have a strong national identity and are embedded in a collectivist culture that shares the Spanish language, cultural traditions, and an emphasis on familism (Perez & Ailshire, Reference Pérez and Ailshire2017). Familism and spirituality has been linked, in Latinxs, to better health behaviors and greater health care utilization (Falicov, Reference Falicov and Falicov2014; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2007). However, Puerto Ricans face several barriers when seeking help for mental health. According to Domenech et al. (Reference Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann, Vázquez, Amador-Buenabad, Franceschi Rivera, Ortiz-Pons and Parra-Cardona2018), Mental Health in Puerto Rico is practically a taboo and some of the barriers that can be found among Puerto Ricans are created by themselves. Puerto Ricans tend to think that mental health problems could be resolved by itself, and also think that seeking help for mental health is a waste of time (Domenech et al., Reference Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann, Vázquez, Amador-Buenabad, Franceschi Rivera, Ortiz-Pons and Parra-Cardona2018). Further, over time, insurers have increased the costs of medical plans and reduced services, particularly limiting access to mental health services (Domenech et al., Reference Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann, Vázquez, Amador-Buenabad, Franceschi Rivera, Ortiz-Pons and Parra-Cardona2018). The World Organization (2012) reports that just 10% of the funds that are assigned for health in Puerto Rico goes to mental health services.

Spirituality among Latinx

Latinx theological literature describes spirituality as an integral part of Latinx culture. Latinx are not a monolithic or homogenous group; there are fundamental cultural influences that must be considered in an exploration of spirituality among Latinx (Deck, Reference Deck2017; Dolan, Reference Dolan1994; Rodriguez, Reference Rodriguez2010). A Latinx core cultural value that influences spirituality, familismo, is characterized by an enduring commitment and loyalty to immediate and extended family members (Campesino & Schwartz, Reference Campesino and Schwartz2006). These faith experiences are often embedded in one's relationship with the family and members of the community, which may or may not include involvement with the church (Campesino & Schwartz, Reference Campesino and Schwartz2006). In 2014, 79% of Latinx in the United States identified with a religious affiliation, and the majority identified as Catholic (Pew Research Center, 2015). Among Latinx immigrant families, church attendance and communal religious activities may provide opportunities to meet other Latinx, thereby offering a place of belonging and familiarity (Comas-Díaz, Reference Comas-Díaz2006; Falicov, Reference Falicov and Falicov2014). Latinx spirituality reflects both indigenous and Christian influences (Baez & Hernandez, Reference Baez and Hernandez2001; Pew Research Center, 2014), and may likewise be a source of support when coping with difficulties. For example, more than half of Latinx in the United States (57%) believe in spirits, and 47% say that they pray to saints to ask for help when facing difficult moments in their lives (Pew Research Center, 2014).

Existential distress among Latinx cancer patients

The importance of caring about the spiritual needs of Latinx cancer patients is well documented (Moadel et al., Reference Moadel, Morgan, Fatone, Grennan, Carter, Laruffa, Skummy and Dutcher1999; Hunter, Costas & Gany, Reference Hunter-Hernández, Costas-Muñíz and Gany2015; Wang, Molassiotis, Chung & Tan, Reference Wang, Molassiotis, Chung and Tan2018). Some research studies have proven that interventions addressing distress in the Latinx cancer patient population should also include treatment components aimed at improving patients’ spiritual well-being (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Tyson, Gonzalez, Small, Lechner, Antoni, Vinard, Krause, Meade and Jacobsen2018). Overall, the studies allege, spirituality helped the various participants endure the cancer experience and provided them with personal insight and comfort (Ashing-Giwa et al., Reference Ashing-Giwa, Padilla, Bohorquez, Tejero and Garcia2006). Religious practices and integrating a given patient's spiritual approaches facilitate that individual's resilience in the face of potentially adverse life events, such as cancer, and also impact the effectiveness of managing and coping with the consequences of cancer (specifically) in survivorship (Hunter, Costas & Gany, Reference Hunter-Hernández, Costas-Muñíz and Gany2015). The growing literature has highlighted lack of meaning and purpose in life as being central to the existential distress that often accompanies the diagnosis of an advanced chronic illness (Travado et al., Reference Travado, Grassi, Gil, Martins, Ventura and Bairradas2010). Our team performed a systematic review and found that a handful of interventions have also targeted spiritual and existential issues in patients with advanced cancer, but Latinxs have been underrepresented or not represented at all in these intervention studies (Ettema, Derksen & Van Leeuwen, Reference Ettema, Derksen and van Leeuwen2010; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito, Rosenfeld, Vickers, Li, Abbey, Olden, Pessin, Lichtenthal, Sjoberg and Cassileth2012; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Cobb, O'Connor, Dunn, Irving and Lloyd-Williams2015).

Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy

Attention to spiritual and existential distress among Latinx patients with advanced cancer is a critical component of palliative care (Hunter, Costas & Gany, Reference Hunter-Hernández, Costas-Muñíz and Gany2015). Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) was designed to target the specific psycho-spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Gibson, Pessin, Poppito, Nelson, Tomarken, Timm, Berg, Jacobson and Sorger2010; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito, Rosenfeld, Vickers, Li, Abbey, Olden, Pessin, Lichtenthal, Sjoberg and Cassileth2012, Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Pessin, Applebaum, Kulikowski and Lichtenthal2015). MCP is a seven-session, manualized behavioral intervention developed by William Breitbart; it is based on the principles of logotherapy and the work of Victor Frankl (Reference Frankl1984). The integration of logotherapy in each session addresses specific themes related to an exploration of the concepts and sources of meaning, the relationship and impact of cancer on one's sense of meaning and identity, and placing one's life in a historical and personal context (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Pessin, Applebaum, Kulikowski and Lichtenthal2015). Several randomized control trials (RCTs) of MCP in both individual and group formats have demonstrated significant improvements in spiritual well-being, quality of life, depression, hopelessness, and desire for death in predominantly non-Hispanic white patients living with advanced cancer (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Gibson, Pessin, Poppito, Nelson, Tomarken, Timm, Berg, Jacobson and Sorger2010; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito, Rosenfeld, Vickers, Li, Abbey, Olden, Pessin, Lichtenthal, Sjoberg and Cassileth2012, Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Pessin, Applebaum, Kulikowski and Lichtenthal2015). Further, a study conducted by Fraguell, Castillo, Limonero & Gil (Reference Fraguell, Castillo, Limonero and Gil2016) reported significant changes in well-being in nine patients who underwent MCP; patients declared having a better emotional and spiritual well-being than before. In fact, results of scales effectively showed that they did have statistically significant improvements (Fraguell, Castillo, Limonero & Gil, Reference Fraguell, Castillo, Limonero and Gil2016).

Given the apparent effectiveness of MCP for advanced cancer patients, we present a case study focused on a Puerto Rican advanced cancer patient who underwent MCP. The critical need for interventions for Latinxs and the disparities in access to psychosocial services for that population suggest the need for culturally appropriate interventions, and this case study is presented to assess the implementation of MCP with Puerto Ricans (Costas-Muniz et al., Reference Crimmins, Garcia and Kim2017). The main goals of this article are to present a case study focused on a Puerto Rican advanced cancer patient who underwent MCP to assess the comprehension and acceptance of the MCP intervention.

Methods

A case study of a participant from an initial cultural adaptation of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) is presented, with a focus on the comprehension and acceptance of the sources of meaning to the Latinx advanced cancer experience. The research protocol was submitted to the institutional review board (IRB) of the Ponce Health Sciences University. We divided the protocol into two methodological phases. In the first phase, qualitative (semi-structured interviews) and quantitative (inventory) data were analyzed. In the second phase, different qualitative (ethnographic notes) and quantitative (pre-test and post-test) data were analyzed. As part of the second methodological phase, a case study was conducted of one patient who completed the Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP). For this article, we will present only the results of a case study of a participant who underwent an MCP intervention.

The participant was recruited at an oncology clinic, referred by his oncologist. After the participant consented to participate in the study, the distress thermometer (DT) screening tool was administered, and his score was six, which indicates high distress, a scaled normed to the Latinx population (Almanza, Rosario & Perez, Reference Almanza, Rosario and Pérez2008). After completing the DT, the participant was invited to complete a more comprehensive scaled assessment normed for the Latinx population, which included spiritual well-being (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being [FACIT-Sp], Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Canada, Fitchett, Stein, Portier, Crammer and Peterman2010) and quality of life scales (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General [FACT-G], Dapueto et al., Reference Dapueto, Francolino, Servente, Chang, Gotta, Levin and del Carmen Abreu2003). Then the participant was invited to participate in MCP and the intervention was conducted in Spanish from December 2017 to April 2018.

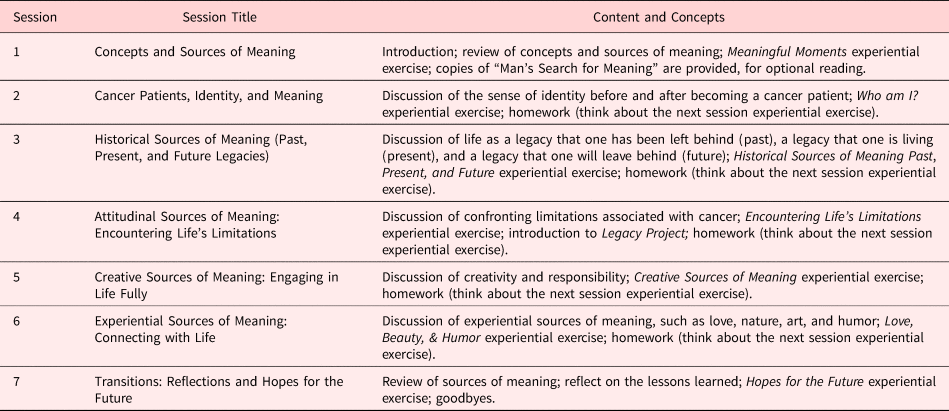

Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy is a seven-session manualized behavioral intervention based on existential psychotherapy. In our participant's first session, a Spanish translation of the book, “Man's Search for Meaning,” was provided for optional reading. Sessions one to five were conducted at the oncology clinic after the patient's medical appointments. Sessions six and seven were conducted by phone. The phone sessions were shorter than the face-to-face sessions, 25 to 30 minutes as opposed to 50 to 60 minutes. Descriptions of the intervention's content and concepts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for cancer patients: weekly topics, content, and concepts

Note. Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy descriptions of the intervention's content and concepts

The ethnographic notes were evaluated to determine the patients acceptance and understanding of the concepts of the intervention. A qualitative deductive analysis was performed with the software ATLAS.ti, with multiple coders (minimum of three) representing different cultural backgrounds (Spain, Puerto Rico, and Mexico). Deductive categories were developed and defined a priori following standard deductive analysis procedures (Elos & Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008; Mayring, Reference Mayring2015). The patient's comprehension and acceptance of the intervention's content was evaluated using the ethnographic notes. The codes included high, moderate, low, and ambiguous comprehension and high, moderate, low, and ambiguous acceptance. A structured coding matrix with categories and definitions was developed prior to the coding activities (Elos & Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008; Mayring, Reference Mayring2015). To improve validity and rugosity (Barbour, Reference Barbour2001), the codes were discussed until a consensus was reached. To illustrate and summarize the findings, data from the ethnographic note were quantified (Elos & Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008; Mayring, Reference Mayring2015) and an adaptation plan was developed summarizing the discussion and recommendations of the consensus meetings.

The pre- and post-assessments explored the distress, spiritual well-being, and quality of life (QOL) levels of the participant. The measure details used in the pre- and post-assessments are explained in Table 2. Raw scores are presented for pre- and post-assessments. The scales used were the FACIT-Sp, FACT-G, and the DT. The Spiritual FACIT-Sp is a brief self-report measure designed to assess an individual's spiritual well-being; it has two sub-scales: Spirituality and Meaning/Peace (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Canada, Fitchett, Stein, Portier, Crammer and Peterman2010; Peterman et al., Reference Peterman, Fitchett, Brady, Hernandez and Cella2002). The FACT-G will be used to assess the quality of life of the participants (Dapueto et al., Reference Dapueto, Francolino, Servente, Chang, Gotta, Levin and del Carmen Abreu2003). The DT (Holland & Bultz, Reference Holland and Bultz2007) is a problem checklist that identifies practical, spiritual, physical, emotional, and family problems.

Table 2. Description of study scales

Note. Scaled normed for the Latinx population (Almanza, Rosario & Perez, Reference Almanza, Rosario and Pérez2008; Dapueto et al., Reference Dapueto, Francolino, Servente, Chang, Gotta, Levin and del Carmen Abreu2003; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Canada, Fitchett, Stein, Portier, Crammer and Peterman2010).

Results

Mr. X was a 78-year-old male diagnosed with colon cancer who lived with his eldest sibling and two grandchildren in a rural area of Puerto Rico. He used to be a construction worker and a handyman before he retired. The patient showed low comprehension of the definitions of meaning, the finite, and legacy and moderate comprehension of the concepts encompassing the search for hope, having a purpose in life, connecting with life, courage, life's limitations, and sources of meaning. The patient showed high comprehension and low acceptance of the death and dying concept (i.e., meaningful death). The patient evinced moderate acceptance of the concepts encompassing the search for hope, having a purpose in life, connecting with life, courage, life's limitations, and sources of meaning and high acceptance of idea of integrating family members into his therapy. During the sessions, the participant declared that he would have liked to have incorporated his family members into the intervention. Since this intervention was designed to be delivered to an individual, family members were not able to participate in the therapy sessions. See Table 3 for the discussion of the comprehension and acceptance by the patient.

Table 3. Comprehension and acceptance of the patient

Note. Discussion of comprehension and acceptance by the patient.

The most salient MCP themes expressed by this Latino patient with advanced cancer are presented below in Table 4. Regarding the patient's historical sources of meaning, the most common themes were being raised in the Catholic faith, spending time with his large family, especially his siblings (past), being a supportive father and grandfather (present), and being remembered as a warrior (future). Throughout the Attitudinal Sources of Meaning session, he exhibited a fighting spirit and searching-for-meaning coping mechanisms that were strengthened after the cancer diagnosis. The Creative and Experiential Sources of Meaning session prompted the theme of getting in touch with family and friends through dance and music.

Table 4. Salient themes of the patient

Note. The most salient MCP themes expressed by this Latino patient with advanced cancer are presented.

By the time he started on MCP, Mr. X was experiencing significant emotional distress (see Table 5 for the pre- and post-assessment results). The patient's distress rate was six (DT, high distress); he had a spiritual well-being score of 50 (FACIT-Sp, low spiritual well-being), and a quality of life score of 45 (FACT-G, low quality of life). Mr. X had never sought any kind of psychiatric help and had never received professional mental health services. This high distress he was experiencing interfered with his sleep and his ability to concentrate and to enjoy daily life activities he used to like. He also reported that sometimes he felt desperate about the future. Moreover, he stated that he had been feeling abandoned by his family members, who, according to the patient, worked most of the time. By the end of the intervention, the patient showed clinically significant improvement in his distress, going from the score of six (DT, high distress) to a score of two (DT, low distress); his spiritual well-being increased from 50 (FACIT-Sp, low spiritual well-being) to 90 (FACIT-Sp, high spiritual well-being), and his QOL from 45 (FACT-G, low quality of life) to 85 (FACT-G, high quality of life), see Table 5.

Table 5. Pre- and post-assessment

Note. The pre-and post-assessment results of the Distress Thermometer, Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp) and Quality of Life (FACT-G).

Discussion

With prevailing concerns about the inclusion of Latinx in the generalizability of evidence-based treatments in the real-world practice setting, the findings of this article provide broad attention to the potential changes of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) to ensure fit with a diverse population. The contribution of the methodology and results present a focus on the comprehension and acceptance of the sources of meaning to the Latinx advanced cancer experience, as a first step in the cultural adaptation process. The ongoing work in the Cultural Adaptation of MCP is highlighted in the findings of this case study to illustrate key issues and recommendations.

The comprehensibility and acceptance of the MCP intervention, in this case study, supports the use of spiritual domains with elderly Puerto Rican men coping with cancer. The literature identifies spirituality as an essential component in terms of coping with advanced cancer (Travado et al., Reference Travado, Grassi, Gil, Martins, Ventura and Bairradas2010). Furthermore, clinical intervention targeting existential issues for patients approaching the end of life have the potential to dramatically improve quality of life in this final phase (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Gibson, Pessin, Poppito, Nelson, Tomarken, Timm, Berg, Jacobson and Sorger2010). Existential issues may underlie many related psychological elements of the end of life on Latinxs and frame a unique opportunity for intervention targeting the meaning of life. However, the state of the science of intervention development and adaptation for Latinx patients with advanced cancer remains underdeveloped and understudied (Hunter-Herdandez, Costas-Muñiz & Gany, Reference Hunter-Hernández, Costas-Muñíz and Gany2015; Ashing-Giwa et al., Reference Ashing-Giwa, Padilla, Bohorquez, Tejero and Garcia2006). It remains limited due to the lack of studies adapting interventions to the cultural and linguistic needs of ethnocultural groups (Bernal, Jimenez-Chafey, Domenesh, Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009; Costas-Muñiz et al., Reference Costas-Muñiz, Garduño-Ortega, González, Rocha, Breitbart and Gany2016).

Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP) is a novel therapeutic approach intended to address the existential issues commonly experienced by advanced cancer patients (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Gibson, Pessin, Poppito, Nelson, Tomarken, Timm, Berg, Jacobson and Sorger2010; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Poppito, Rosenfeld, Vickers, Li, Abbey, Olden, Pessin, Lichtenthal, Sjoberg and Cassileth2012, Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld, Pessin, Applebaum, Kulikowski and Lichtenthal2015). The case study example highlights the comprehension and acceptance of the MCP with modification to an elderly Puerto Rican man coping with cancer. Examples of these modification of the MCP intervention are described in Table 4. This study describes the clinical psychological challenges of an elderly Puerto Rican with advanced cancer whose symptoms improved after receiving Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy. It adds to the relatively sparse literature on intervention development to socioeconomically disadvantaged elderly cancer patients (Hunter-Herdandez, Costas-Muñiz & Gany, Reference Hunter-Hernández, Costas-Muñíz and Gany2015; Ashing-Giwa et al., Reference Ashing-Giwa, Padilla, Bohorquez, Tejero and Garcia2006). Signs of psychological improvements were noted in the three-assessment tool (Table 5): six (DT/high-distress) to two (DT/low-distress), spiritual well-being from 50 (FACIT-SP/low-spirituality) to 90 (high-spirituality), and QOL 45 (FACT-G/low) to 85 (high).

This case study provided examples in which the exploration of four sources of meaning in life may have served as a coping resource for an elderly Puerto Rican man who felt emotional distress due to his advanced cancer trajectory. The exploration of legacy in this case study, for example, identified the historical factors that contributed to the patient's desire to have his family involved throughout the cancer trajectory. The discussion of attitude during the sessions allowed the patient to see his current limitations and strengthen his ability to view to those limitations from another perspective. This could translate into meaningful transformative experiences for those who struggle with cancer-related limitations. Helping a Puerto Rican elderly patient to recognize that through finding meaning in love, beauty, and humor he can enjoy moments of peace and transcendence can have the potential to be a transformative process. Furthermore, findings suggest that MCP has the possibility of being a feasible intervention for Puerto Rican patients with advanced cancer who suffer from distress, low spiritual well-being, and low QOL. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to increase the cultural fit, addressing cultural themes, and improving the acceptance and comprehension of the MCP concepts and content.

Acknowledgments

Normarie Torres-Blasco received support from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (5G12MD007579, 5R25MD007607, and R21MD013674).

Eida M. Castro-Figueroa received support from the National Cancer Institute (2U54CA163071 and 2U54CA163068) and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (5G12MD007579, 5R25MD007607, and R21MD013674).

Iris Crespo-Martín received support from “Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte en el marco del Programa Estatal de Promoción del Talento y su Empleabilidad en I + D+i, Subprograma Estatal de Movilidad, del Plan Estatal de Investigación Científica y Técnica y de Innovación 2013–2016.”

Rosario Costas-Muñiz received grant support from the National Cancer Institute R21CA180831-02 (Cultural Adaptation of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Latinos) and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center grant (P30CA008748).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

We thank Bob Ritchie of the Publications Office of Ponce Health Sciences University–Ponce Research Institute for helping with the manuscript.