Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common finding in patients with advanced cancer with a frequency of 14.9% (95% CI 12.2–17.7) (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Chan and Bhatti2011). In addition to its high frequency, MDD represents a source of morbidity and negatively impacts survival in patients with advanced cancer. Among its many repercussions, MDD is associated with worse functioning, survival rates, quality of life, and treatment compliance, as well as with wishes to hasten death and a higher frequency and intensity of physical symptoms (Lloyd-Williams et al., Reference Lloyd-Williams, Dennis and Taylor2004; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Pinquart and Duberstein, Reference Pinquart and Duberstein2010; Rodríguez-Mayoral et al., Reference Rodríguez-Mayoral, Ascencio-Huertas and Verástegui2019, Reference Rodríguez-Mayoral, Cacho-Díaz and Peña-Nieves2020). Although it is a common complication, it is underdiagnosed and therefore undertreated (Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, Strong and Allen2004).

MDD in cancer patients is more prevalent compared with the general population (Medina-Mora et al., Reference Medina-Mora, Borges and Benjet2007). Case-finding tools and mechanisms that facilitate the timely identification and assessment of this disorder by a mental health professional are needed in order to achieve detection and treatment (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Meader and Davies2012). A brief instrument that considers this population, with high sensitivity and negative predictive value, would be a valuable tool in the clinical setting, in order to screen patients during their usual appointments. In this regard, multiple efforts have been made to validate instruments that may aid in identifying patients with advanced cancer under palliative care who are candidates for a more extensive evaluation by a mental health professional. One of the most used accepted tools is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Butow and Aaronson2015), developed by Zigmond and Snaith (Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983). This is a self-administered tool consisting of 14 items with four different available answers, ranging from 0 to 4, and integrated by two subscales (anxiety and depression). Its strength lies in excluding MDD symptoms that may overlap with those of cancer and its treatment, allowing a better assessment of depression. It has been validated in many languages and clinical scenarios (López-Alvarenga et al., Reference López-Alvarenga, Vázquez-Velázquez and Arcila-Martínez2002; Galindo Vázquez et al., Reference Galindo Vázquez, Meneses García and Herrera Gómez2016; Barriguete Meléndez et al., Reference Barriguete Meléndez, Pérez Bustinzar and de la Vega Morales2017).

The HADS tool was validated in a Mexican population of patients with cancer by Galindo Vázquez et al. (Reference Galindo Vázquez, Benjet and Juárez García2015). This study included 400 hospitalized and ambulatory patients. The depression subscale (HADS-D) resulted in an internal consistency of 0.80 as measured by Cronbach's alpha, allowing for solid psychometric properties in Mexican population with cancer and a concurrent validity with Beck's Depression Inventory (Jurado et al., Reference Jurado, Villegas and Méndez1998). Cutoff scores were set as follows: 0–5 no depression, 6–8 mild depression, 9–12 moderate depression, and >12 severe depression (Galindo Vázquez et al., Reference Galindo Vázquez, Benjet and Juárez García2015).

The Brief Edinburgh Depression Scale (BEDS) is a self-administered tool consisting of 6 items (Rodríguez-Mayoral et al., Reference Rodríguez-Mayoral, Rodríguez-Ortíz and Ascencio-Huertas2018) and was recently validated in Mexican patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care service, including 70 ambulatory subjects, and then contrasted with a clinical evaluation. An internal consistency of 0.71 measured by Cronbach's alpha was found, with a cutoff score of ≥6 points for depression, 64.3% sensitivity, and 75% specificity. However, when using a ≥5 cutoff score, sensitivity is increased to 85.7% and specificity decreased to 62.5% with a global measure of exactitude of 0.825, rendering this useful for the screening of depression in this population.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no consensus as to the ideal case-finding tool for MDD in patients with advanced cancer who are undergoing palliative care. Although the HADS is more widely used, it has not been extensively evaluated in this particular setting (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Meader and Symonds2010). The objective of this study was to compare the HADS-D subscale and BEDS as case-finding tools for depression in advanced cancer patients in palliative care.

Methods

The study was approved by the local Bioethics and Research Review Boards of the National Institute of Cancerology, Mexico (registration numbers 017/004/CPI and CEI/1114/17, respectively). All subjects signed an informed consent prior to participation.

Patients and data collection

This was a prospective, observational study with non-probabilistic sampling. Consecutive patients attending the Palliative Care Unit at the National Cancer Institute of Mexico (INCan) from January 2017 to September 2018 were prospectively included in this study. All patients who had a confirmed diagnosis of advanced cancer were invited to participate. The diagnosis for advanced cancer was performed by specialized oncologists in each of the tumor clinics at the institute and included patients with cancer which is unlikely to be cured with treatment. Inclusion criteria considered literate Spanish-speaking patients of any age (>18 years of age) or sex, regardless of the primary site of the neoplasm, with a score of 0 to 2 in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scale (ECOG), and a Karnosfky index of ≥50. Additionally, information was also collected during the interview in order to calculate the palliative prognostic index (PPI), a score which considers the Palliative Performance Scale, calculated from the Karnofsky Performance Scale, and other clinical variables including oral intake, edema, resting dyspnea at rest, and delirium. The PPI is used to predict survival in palliative cancer patients. Patients are classified according to their score into group A (PPI ≤2), group B (PPI 2–4) and group C (PPI >4). Survival is worse in group C compared with group B, and better in group A compared with the other two groups (Morita et al., Reference Morita, Tsunoda and Inoue1999). Exclusion criteria included refusal to participate and the inability to understand or complete the scales. Subjects with delirium, psychosis, central nervous system (CNS) tumor activity (including CNS primary tumors or CNS metastases), patients receiving antidepressants, or who presented with uncontrolled physical symptoms (such as pain) were also excluded.

Scales and measurements

BEDS and HADS were self-administered in the palliative care service, and subjects were later evaluated by a Psychiatrist blinded to the scores to provide an MDD diagnosis through a semi-structured interview according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in its 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2014). The HADS includes six items that compose the depression subscale, each is rated on a 5-point scale (0–4). Overall, the minimum score in the HADS-D scale is 0 and the maximum score is 18. For the BEDS, six items are included and scored. Patients screened for depression are considered cases when scoring ≥5 in this scale in our population (Rodríguez-Mayoral et al., Reference Rodríguez-Mayoral, Rodríguez-Ortíz and Ascencio-Huertas2018).

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis of sociodemographic, functional, and clinical characteristics was carried out, including medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as well as absolute and relative frequencies according to each variable type. To establish the screening diagnostic capacity of HADS-D and BEDS in classifying patients as depressed or non-depressed, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were determined comparing the area under the curve (AUC) for each test in comparison with clinical diagnosis. Data analysis was carried out using STATA version 12.0 (StataCorp, 2011).

Results

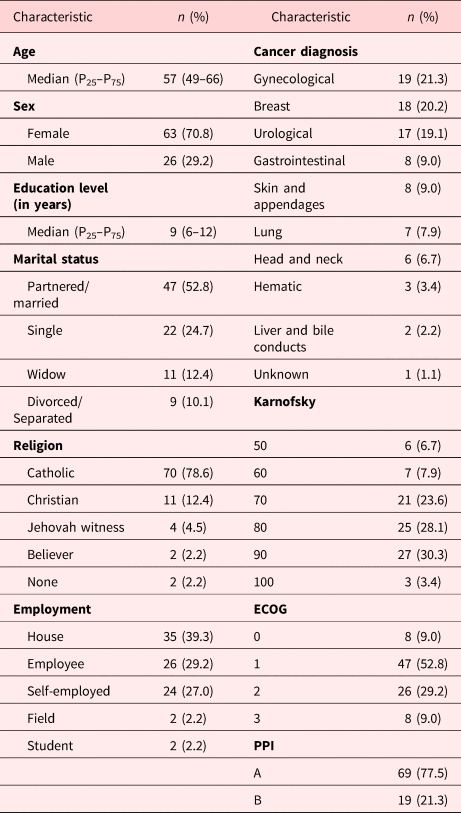

A total of 110 patients were screened for inclusion and invited to participate in this study, 89 patients agreed to participate and were included, with a median age of 57 years (range 20–85). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and the clinical characteristics of the subjects. Overall, most patients were married/partnered (52.8%), catholic (78.6%), had a Karnofsky score of ≥70 (85.4%), and a group A PPI score in 77.5%. Median score in the HADS-D scale was 3 (IQR 1–6), while the median score in the BEDS was 4 (IQR 2–6). Among the total sample, 19 patients (21.3%) had an MDD clinical diagnosis according to the psychiatric interview. Figure 1 shows the cutoff values for each diagnostic tool. BEDS had a better performance when discriminating between depressed and non-depressed patients as compared to HADS-D (AUC 0.8541 vs. 0.7665), although the difference between both curves did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05), in terms of AUC, BEDS numerically outperforms HADS. Similarly, considering the implications of depression on the lives of cancer patients, it is important for the test to have a high negative predictive value, which is the case for BEDS (Table 2).

Fig. 1. ROC for Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) and Brief Edinburgh Depression Scale (BEDS) in comparison to clinical diagnosis for depression.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (N = 89)

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PPI, Palliative Prognostic Index.

Table 2. Positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) for HADS and BEDS according to the 6 cutoff points assessed

HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, depression subscale; BEDS, Brief Edinburgh Depression Scale; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Discussion

A cancer diagnosis entails a considerable source of distress for patients facing this disease; as such patients with cancer are often at a high risk for developing MDD. Nonetheless, MDD is commonly underdiagnosed, despite the well-known effect of this comorbidity in terms of survival and quality of life. There are several tools which have been developed in order to provide a simple and efficient manner to screen patients for MDD, and therefore aid in optimizing resources and offering timely treatment. Among these, the BEDS and HADS have been widely used and validated across a wide array of subjects.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to make a head to head comparison among two of the most widely accepted and validated case-finding tools for MDD in Mexican patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Results show that global BEDS performance was better compared with HADS-D, when both screening tools are contrasted to a psychiatric evaluation using the current gold standard.

Results from this study are of relevance both in the clinical and research setting. The objective of identifying which instrument can best perform in terms of identifying possible cases of MDD through a high sensitivity and a low negative predictive value was approached through a head-to-head comparison of both instruments. The scales were administered at the same time to a representative population of advanced cancer patients in order to have them answer each tool under the same clinical and social conditions. There are many advantages to using self-administered tools in order to screen patients for MDD. These questionnaires are widely available, are validated in many different languages, represent a very low-cost screening tool, and are short and simple so that patients can answer without requiring assistance.

The benefits of improving MDD diagnosis in advanced cancer patients are considerable. Timely diagnosis translates to improved treatment and better mental health which could impact in quality of life, physical symptoms, treatment compliance, suicidal risk, wish to hasten death, and survival rates (Lloyd-Williams et al., Reference Lloyd-Williams, Dennis and Taylor2004; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Pinquart and Duberstein, Reference Pinquart and Duberstein2010; Rodríguez-Mayoral et al., Reference Rodríguez-Mayoral, Ascencio-Huertas and Verástegui2019, Reference Rodríguez-Mayoral, Cacho-Díaz and Peña-Nieves2020). Large-scale studies with considerable follow-up have consistently shown the beneficial effect of depression treatment in patients with good or bad prognosis malignancies, both in terms of reducing major depression and improving quality of life (Mulick et al., Reference Mulick, Walker and Puntis2018).

Results from this study suggest that using BEDS with a cutoff score of 5 for case-finding of MDD can aid in identifying cases with high sensitivity. When comparing the two curves (HADS-D vs. BEDS), BEDS outperforms HADS in terms of accuracy. Quantitatively, it is established that the closest the value under the curve is to 1 (the resulting measure of the combination of sensitivity and specificity), the better performance by the test, therefore showing a better performance for BEDS compared with HADS-D in this study (Kumar and Indrayan, Reference Kumar and Indrayan2011; Yang and Berdine, Reference Yang and Berdine2017).

For instruments which seek to screen for cases, such as the instruments evaluated in this study, it is of particular interest to the researcher to identify as many potentially depressed patients as possible (high sensitivity), with a high negative predictive value, given the impact of the underdiagnosed disease on several cancer-related outcomes, including quality of life and survival. Patients who are not timely diagnosed are unable to access treatment by a field expert in mental health, and this in turn will negatively impact quality of life, intensity of physical symptoms, treatment compliance, wishes to hasten death, and overall survival (Lloyd-Williams et al., Reference Lloyd-Williams, Dennis and Taylor2004; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Pinquart and Duberstein, Reference Pinquart and Duberstein2010, p. 7; Arrieta et al., Reference Arrieta, Angulo and Núñez-Valencia2013; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalgleish and Chochinov2016). This recommendation could help achieve the World Health Organization goals for mental health in our country (Heinze et al., Reference Heinze, Bernard-Fuentes and Carmona-Huerta2019). Better performance by BEDS considering the item alignment with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria is a possibility, though considering the fact that DSM-5 is the current gold standard that is not, in our consideration, particularly limiting, as we are seeking a tool which can better screen, and this alignment might work towards this goal. On the other hand, there are considerable overlaps in terms of some of the diagnostic criteria items and cancer symptoms in advanced patients, as well as some which are the result of chemotherapy and other treatment modalities. As such, the diagnosis for MDD in cancer patients has constantly been considered to have several assessment challenges related with these confounding factors with disease load (Lie et al., Reference Lie, Hjermstad and Fayers2015), nonetheless, our study is particularly relevant in considering the fact that the interviews were performed by a specialized psychiatrist from the palliative care unit who specializes in the assessment of cancer patients, and has therefore vast experience in terms of emphasizing cognitive symptoms and ruling out overlaps with somatic symptoms in order to arrive at a diagnosis.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. This study included a small sample size of patients (which might have impacted the statistical significance of the results) with different primary neoplasms. Additionally, all patients were recruited at the National Institute of Cancer, a third level oncology reference center. Therefore, it is possible that a selection bias could be present in the study. Nonetheless, strengths include a homogeneous evaluation of the patients by a palliative care psychiatrist and the application of both questionnaires at the same time point.

Conclusions

Results from this study suggest that BEDS outperforms HADS-D for identifying cases of MDD. Larger multicenter trials are warranted in order to further validate these results.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rodrigo Pérez-Esparza, M.D., MSc. for his valuable collaboration in the development of this paper. Also, we would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

No funding was received.

Conflict of interest

Oscar Rodríguez-Mayoral and Silvia Allende-Pérez received partial support from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) Sistema Nacional de Investigadores and declare no potential conflict of interest. Adriana Peña-Nieves and Mari Lloyd-Williams do not report actual or potential conflicts of interest.