INTRODUCTION

Medical improvements have led to longer survival of pediatric patients (Goldman et al., Reference Goldman, Hain and Liben2006; Benini et al., Reference Benini, Spizzichino and Trapanotto2008). As a result, the number of children with life-limiting and life-threatening illnesses is increasing. This explains why pediatric palliative care (PPC) is becoming an important subspecialty within the setting of overall healthcare. The illness of a child alters family relationships, and family members often experience psychological and emotional distress as a result (Mooney-Doyle & Deatrick, Reference Mooney-Doyle and Deatrick2016). Therefore, PPC aims to care for children and their loved ones in a multidisciplinary fashion. It focuses not solely on pain and symptom management, but also on the social, psychological, and spiritual well-being of patients and their families.

Palliative care developed first within adult cancer care. Its history is closely related to that of the hospice movement. For almost two decades, the terms “palliative care” and “hospice care” were used interchangeably, until the World Health Organization (WHO, 1990) fostered a conceptual distinction between the two (Foster, Reference Foster2007). Unlike hospice care, palliative care was no longer identified with “end-of-life care,” but was “applicable earlier on in the course of illness, in conjunction with anticancer treatment” (WHO, 1990). In 2002, the WHO promulgated a further amendment of the general definition of palliative care (WHO, 2002). From then on, palliative care would be defined as an appropriate approach to care for anyone with a life-threatening condition irrespective of prognosis (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2011). Other organizations have since adopted this broader understanding in their palliative care recommendations: the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (Institute of Medicine, Reference Field and Behrman2003), the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) (the IMPaCCT standards; IMPaCCT, 2007), and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH, 2005).

The field of palliative care for children and neonates developed in the 1980s under the stimulus of palliative care for adults (Davies, Reference Davies, Stillion and Attig2014). Still, it was mainly from the 1990s onward, with the formation of the Association for Children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and Their Families (ACT) (currently called “Together for Short Lives”) and ChiPPS (the Children's Project on Palliative and Hospices Services) that palliative care for children became more diffuse. “A Guide to the Development of Children's Palliative Care Services” (ACT, 1997) was one of the first documents to define palliative care as a total approach to care for children and the family (Harrop & Edwards, Reference Harrop and Edwards2013). “Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care in Children” (WHO, 1998) represented another significant milestone for the acceptance of PPC. This latter document states that pain management for children should begin at diagnosis and continue throughout the course of illness alongside curative treatment. Early integration of palliative care is highly beneficial for children with chronic and life-threatening conditions, as they often have complicated illness trajectories that come with a high degree of prognostic uncertainty (Levine et al., Reference Levine, Lam and Cunningham2013). This integrative model was soon also embraced by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (AAP, 2000; Davies, Reference Davies, Stillion and Attig2014).

Following the palliative guidelines (ACT, AAP, WHO), the current gold standard definition of PPC includes: (1) concurrent administration of curative and palliative treatment from diagnosis onwards, (2) attention to the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients and their families; (3) provision of services 24/7 at home, in the hospital, or in health community centers that should not stop with the child's death; and (4) a team composed of at least physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and family members. The main aim of PPC is to enhance the child's quality of life rather than focusing on the quality of the dying process (Stayer, Reference Stayer.2012).

Although the number of palliative care facilities for children has grown, it still lags behind the number of those for adults (Gethins, Reference Gethins2011; Moody et al., Reference Moody, Siegel and Scharbach2011). However, even when they are available, the existing guidelines are not adequately implemented. Many children who could benefit from palliative care services in fact do not receive them, or at least not in a timely manner (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Poehling and Billheimer2006; Keel et al., Reference Keele, Keenan and Sheetz2013; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Nagel and O'Halloran2007). A significant difficulty in the United States has been that, until the introduction of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010, palliative care for pediatric patients was determined following hospice regulations for adults, meaning that disease-related treatments were not covered and reimbursement was limited to the last six months of a patient's life (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Munson and Hwang2014). However, low referral rates have been reported in Canada (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Nagel and O'Halloran2007) and in Europe as well (Craft & Killen, Reference Craft and Killen2007; Midson & Carter, Reference Midson and Carter2010). Since the number of children with life-threatening and life-limiting conditions is still on the rise, it is even more important to address the underlying reasons for these late or nonreferrals.

Various studies have identified barriers to palliative care in general (Brown, Reference Brown2011; Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, Cobb and Gott2011; Kavalieratos et al., Reference Kavalieratos, Mitchell and Carey2014) and PPC in particular (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Sehring and Partridge2008; Knapp & Thompson, Reference Knapp and Thompson2012), but mostly from the perspective of the patient, healthcare provider, or family member. None of these studies have documented these barriers through the looking glass of the PPC guidelines themselves. Therefore, our literature review had the following aims: to identify (empirical and theoretical) studies that discuss PPC guidelines in order to: (1) explore the development and evolution of these guidelines; (2) assess the barriers to their proper implementation; and (3) identify and address possible gaps in the guidelines.

METHODS

A systematic literature review was completed by searching the following online databases: Scopus, PubMed, PsycINFO, the Web of Science, and CINAHL (see Table 1). The following search terms were combined using Boolean logic: “Pediatric*,” “child*,” “adolescent*,” “palliati*,” “palliative care,” “hospice care,” “guidelines,” and “recommendations.” The inclusion criteria were: (1) published between 1960 and May of 2015 and (2) written in English or German. A 50-year publication window was chosen to capture earlier studies that most likely utilized a different conceptual framework than more recent works (in particular, since WHO [1990], AAP [2000], and WHO [2002]) when discussing and assessing palliative pediatric guidelines. No restrictions were placed on type of methodology (quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods, or theoretical). In addition, literature reviews, abstracts, comments, conference proceedings, dissertations, and books were excluded.

Table 1. Search terms

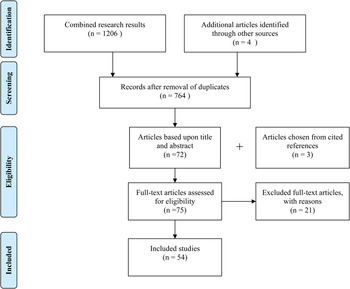

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff2009) was employed to organize the research (see Figure 1), which resulted in 1,210 papers. After removal of duplicates, 764 remained. During the first step of the review, three researchers screened all 764 titles and abstracts. All articles that discussed pediatric palliative guidelines (in general or a particular subaspect like pain and symptom management, psychosocial, spiritual, cultural, or bereavement care) were included. With respect to guidelines, we intended to deal not only with nationally and internationally recognized ones from pediatric organizations, but also those developed within a hospital context. The guidelines themselves (those issued by the AAP, WHO, etc.), however, were not part of the review, having been assessed in another publication (blinded for peer review). Studies that dealt exclusively with neonatal and/or perinatal palliative guidelines were excluded. Papers discussing one specific type of pain management (e.g., a particular drug or palliative sedation) or psychological support (e.g., music therapy) were also excluded. Discrepancies between reviews were evaluated by a fourth reviewer, who determined which articles were potentially eligible based on the abstract. In total, 692 articles were excluded.

Fig. 1. Search process using a PRISMA systematic review of the literature.

The reference lists of the remaining 72 papers were checked to identify any additional studies. Three papers were added through this process. The final sample thus included 75 papers. During the next phase, the first author read the full-text versions of the articles. After evaluating each article, 21 were excluded because they (1) focused mainly on adult palliative care and only superficially on palliative care for children; (2) touched only implicitly on palliative care guidelines, addressing instead certain subaspects of PPC like decision making or the notion of a good death; or (3) focused in detail on certain pain medications.

To assess the remaining 54 articles, a data extraction framework was created with the following information: year of publication, country of study, methodology, references to PPC guidelines, type of PPC, barriers to implementation of guidelines, and recommendations for overcoming these barriers.

RESULTS

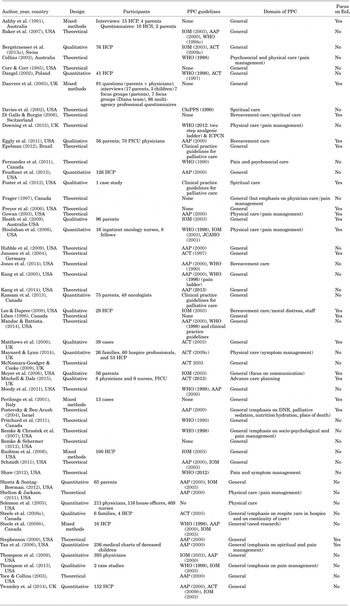

Among the 54 papers included in our analysis, 29 were theoretical papers, that is, they proposed a theoretical framework of PPC or critically reviewed PPC models and practices. Of the remaining 25 studies, 10 employed quantitative methods, 10 qualitative methods, and 5 mixed methods. Most of the papers (n = 46) were published after the 2002 WHO amendment. Some 30 papers were from the United States, 7 from the United Kingdom, 7 from Canada, and the remaining ones from Australia, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Israel, and Poland, and one from two countries. The most frequently cited guidelines were WHO (1998), AAP (2000), IOM (Reference Field and Behrman2003), and ACT (various editions between 1997 and 2013). Concerning the domains of PPC, 38 papers discussed palliative care in general. From the remaining 16 papers, 3 focused on two dimensions at the same time. The other 13 papers addressed one specific domain of PPC. End-of-life care was the main focus in a total of 21 papers, but only 4 of these dated from the most recent period, and 2 focused on bereavement care (see Table 2).

Table 2. List of included studies

AAP = American Academy of Pediatrics; ACT = Association for Children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and Their Families; ChiPPS = Children's Project on Palliative and Hospices Services; DNR = do not resuscitate; EoL = end of life; HCP = healthcare professional; HCS = healthcare staff; ICPCN = International Children's Palliative Care Network; IOM = Institute of Medicine; JCAHO = Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; PPC = pediatric palliative care; WHO = World Health Organization.

The Development of Pediatric Palliative Care Guidelines

To explore the development of PPC guidelines, we divided the studies into four different periods to correspond with the publication of the most important documents in PPC.

The 1980s and 1990s: The “Thirst” for Guidelines

We assessed four studies (one mixed-methods and three theoretical studies) that dated from before the 1998 WHO and 2000 AAP guidelines (Corr & Corr, Reference Corr and Corr1985; Ashby et al., Reference Ashby, Kosky and Laver1991; Liben, Reference Liben1996; Frager, Reference Frager1997). These papers welcomed the increasing trend toward honest and open communication about dying as a result of the hospice movement for adults, but stressed that the death of children was harder to discuss. They also underlined the importance of comfort and quality of life within the hospice philosophy and the need to include children in this type of care. They already introduced some of the central tenets of palliative care for children: the need for (1) total or holistic care; (2) bereavement care for patients, family, siblings, and staff; (3) adequate pain assessment and control; (4) an interdisciplinary care team; and (5) continuity of care. Two studies focused exclusively on the needs of the dying child and did not make a clear conceptual distinction between hospice and palliative care (Ashby et. al Reference Ashby, Kosky and Laver1991; Liben, Reference Liben1996). Corr and Corr (Reference Corr and Corr1985) defined hospice care as a form of palliative care for both terminal and chronic conditions, but failed to explain the difference. Frager (Reference Frager1997) marked a kind of transition point, as this was the first paper among the four being discussed here to explicitly refer to an inclusive model of palliative care that should begin at diagnosis and be available not only for those with an imminently terminal condition, but also for individuals with a life-threatening disease, independent of outcome.

In the Direct Aftermath of Landmark Guidelines (1998–2002)

We assessed five papers (Collins, Reference Collins2002; Dangel, Reference Dangel2002; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Brenner and Orloff2002; Perilongo et al., Reference Perilongo, Rigon and Sainati2001; Stephenson, Reference Stephenson2000) that were published shortly after or during the publication of internationally recognized palliative care guidelines (AAP, 1997; ACT, 1997; ChiPPS, 2001; Masera et al., Reference Masera, Spinetta and Jankovic1999; WHO, 1998b ; 2002). Although most of them acknowledged the crucial role that guidelines play in promoting acceptance of the palliative care paradigm in pediatrics, some (empirical) studies raised the concern that these well-intentioned guidelines would remain purely theoretical in the face of the lack of national palliative care programs for children (Dangel, Reference Dangel2002). Stephenson (Reference Stephenson2000) stated that hospice guidelines for adults (life expectancy of fewer than six months and no life-prolonging treatment) are too restrictive for pediatrics (due to difficulties involved with prognosis). Together with Collins (Reference Collins2002) and Dangel (Reference Dangel2002), he embraced a total and integrative model (“from diagnosis onward”) of palliative care, but failed to make a clear distinction between palliative and hospice care. Dangel (Reference Dangel2002) insisted that prognosis at diagnosis should be poor in order to initiate PPC. Perilongo and colleagues (Reference Perilongo, Rigon and Sainati2001) equated palliative care with terminal care for the dying child.

The First Decade of Pediatric Palliative Guidelines (2003–2009)

The 23 papers dating from this period praised the increasing interest in palliative care within pediatrics but underlined the limited availability of pediatric palliative services, as well as a lack of knowledge and specialized staff. Gowan (Reference Gowan2003) and Thompson and colleagues (Reference Thompson, Knapp and Madden2009) highlighted the difference between palliative and hospice care. However, they noted that this adult model of end-of-life care is unrealistic for children with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions due to the restrictive policies regarding length and type of treatment (especially in the United States). In line with the guidelines, a growing number of articles underlined that, given the prognostic uncertainty, the pediatric population would benefit most from a holistic and integrative approach to care, that is, they insisted that palliative care should take place alongside curative treatment and begin at diagnosis (Freyer et al., Reference Freyer, Kuperberg and Sterken2006; Gowan, Reference Gowan2003; Hubble et al., Reference Hubble, Ward-Smith and Christenson2009; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Hoehn and Licht2005; McNamara-Goodger & Cooke, Reference McNamara-Goodger and Cooke2009; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Totapally and Torbati2006; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Knapp and Madden2009). This concurrent approach was also believed to improve the acceptance and thus implementation of palliative care guidelines for children (McNamara-Goodger & Cooke, Reference McNamara-Goodger and Cooke2009; Hubble et al., Reference Hubble, Ward-Smith and Christenson2009; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Totapally and Torbati2006). At the same time, 12 of the 23 articles explicitly focused on PPC guidelines for end-of-life care (Danvers et al., Reference Danvers, Freshwater and Cheater2003; Di Gallo & Burgin, Reference Di Gallo and Burgin2006; Freyer et al., Reference Freyer, Kuperberg and Sterken2006; Gowan, Reference Gowan2003; Heath et al., Reference Heath, Clarke and McCarthy2009; Houlahan et al., Reference Houlahan, Branowicki and Mack2006; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Friedland and Richter2004; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Gambles and Ellershaw2006; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Ritholz and Burns2006; Postovsky & Ben Arush, Reference Postovsky and Ben Arush2004; Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Sellers and Heller2005; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Totapally and Torbati2006). Two of them (Danvers et al., Reference Danvers, Freshwater and Cheater2003; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Friedland and Richter2004) discussed guidelines for end-of-life homecare in which pain and symptom control, good coordination, and continuity of care, together with a partnership approach with respect to the family, are central tenets. Several papers emphasized the importance of honest and open communication with family members regarding prognosis and death (Di Gallo & Burgin, Reference Di Gallo and Burgin2006; Heath et al., Reference Heath, Clarke and McCarthy2009; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Ritholz and Burns2006; Postovsky & Ben Arush, Reference Postovsky and Ben Arush2004; Remke & Chrastek, Reference Remke and Chrastek2007). Rushton and colleagues (Reference Rushton, Rede and Hall2006) addressed the problem of moral distress among healthcare staff due to competing professional ethical obligations and interdisciplinary conflicts. They proposed a facilitation model of education to support caregivers. Two papers offered guidelines for pain and symptom management (Houlahan et al., Reference Houlahan, Branowicki and Mack2006; Remke & Chrastek, Reference Remke and Chrastek2007). Several (both empirical and theoretical) papers acknowledged the need to adapt guidelines to a child's individual needs, depending on age, maturity, culture, and religion (Danvers et al., Reference Danvers, Freshwater and Cheater2003; Di Gallo & Burgin, Reference Di Gallo and Burgin2006; Hubble et al., Reference Hubble, Ward-Smith and Christenson2009; Freyer et al., Reference Freyer, Kuperberg and Sterken2006; McNamara-Goodger & Cooke, Reference McNamara-Goodger and Cooke2009). The empirical study authored by Steele and colleagues (Reference Toce and Collins2008a ; 2008b) emphasized the need for more research on family experiences, pain management, and bereavement care in order to improve existing PPC guidelines. In the present sample, 12 of the 23 papers were empirical. Two qualitative studies by Heath et al. (Reference Heath, Clarke and McCarthy2009) and Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Ritholz and Burns2006) reported on parental satisfaction with end-of-life care and the need to integrate their priorities (honest communication, emotional support, care coordination, integrity of parent–child relationships, and faith) to facilitate good PPC. Four other empirical studies focused instead on the experiences of pediatric healthcare personnel: two articles addressed the issue of moral distress (Lee & Dupree, Reference Lee and Dupree2008; Rushton et al., Reference Rushton, Rede and Hall2006); two others concentrated on their preparation and training and concluded that, although staff members assessed themselves as knowledgeable; their awareness of the guidelines was limited (Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Sellers and Heller2005; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Knapp and Madden2009). The quantitative study of Thompson and colleagues (Reference Thompson, Knapp and Madden2009) also reported that, although half of their 303 physicians (all AAP members) would refer patients before the end of life, very few of them would refer them at diagnosis. Their findings showed that implementing PPC in practice might be problematic. The authors expressed the need for a more practical service-related definition of palliative care to avoid any connotation of hospice care.

The Most Recent Period (2010–2015)

The 22 studies that dated from 2010 to 2015 reported that PPC is increasingly recognized as a priority by policymakers and hospital staff. Three theoretical studies conducted in the United States (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Munson and Hwang2014; Mandac & Battista, Reference Mandac and Battista2014; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2011) referred to the 2010 change in federal legislation (the Affordable Care Act), which allowed for concurrent care (cure-related and palliative) for children until the age of 21. Still, despite recommendations and growing support worldwide, an important practice gap continued to exist between valued services and those that effectively reach the family (Kassam et al., Reference Kassam, Skiadaresis and Habib2013; Maynard & Lynn, Reference Maynard and Lynn2014; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Meinert and Barker2013). In some of the world's most populous countries, PPC services are not readily available (Downing et al., Reference Downing, Jassal and Mathews2015), and even within the same country there might be important differences in terms of number of staff, level of funding, and education, depending on the region or state (Feudtner et al., Reference Feudtner, Womer and Augustin2013). Various studies expressed the need for further research on PPC in order to assess financial benefits (Feudtner et al., Reference Feudtner, Womer and Augustin2013); improve pain management (Downing et al., Reference Downing, Jassal and Mathews2015; Shelton & Jackson, Reference Shelton and Jackson2011), show clinical benefits (improved quality of life and survival) (Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Inglin and Abbruzzese2013a ), define familial needs, identify moral distress in members of the healthcare team, and explore the use and implications of advance directives in a pediatric population (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2011). Almost all of these papers highlighted the importance of providing holistic care that addresses the needs of all involved parties. One qualitative study focused on spiritual care for patients and families (Foster et al., Reference Foster, Bell and Gilmer2012); five studies concentrated on bereavement care for the family during and after the child's death (Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Inglin and Abbruzzese2013a ; Eggly et al., Reference Eggly, Meert and Berger2011; Foster et al., Reference Foster, Bell and Gilmer2012; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2011; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Contro and Koch2014); and five studies took into account the needs of healthcare professionals (Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Inglin and Abbruzzese2013a ; Downing et al., Reference Downing, Jassal and Mathews2015; Epelman, Reference Epelman2012; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Contro and Koch2014; Kassam et al., Reference Kassam, Skiadaresis and Habib2013). In line with the guidelines, various papers indicated that holistic care requires an interdisciplinary approach (Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Inglin and Abbruzzese2013a ; Downing et al., Reference Downing, Jassal and Mathews2015; Foster et al., Reference Foster, Bell and Gilmer2012; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Contro and Koch2014; Mitchell & Dale, Reference Mitchell and Dale2015). Another core concept supported by most of these papers is the idea that palliative care should be integrated into the routine care of patients with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions, from diagnosis onward, due to its beneficial impact on patients and families. Finally, two theoretical studies addressed the lack of and need for specific palliative care guidelines for adolescents (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Fraser and Freeman2011; Pritchard et al., Reference Pritchard, Cuvelier and Harlos2011).

Barriers to Adequate Implementation of PPC

Most of the 54 papers discussed the barriers to adequate PPC implementation, which can be subcategorized into eight different types of obstacles (see Table 3). The most common barriers discussed in these papers were connected to policy, operational, healthcare staff, and research factors. Other frequently occurring barriers to effective delivery of palliative care to children were associated with the uniqueness of the pediatric context: uncertainty about prognosis and lifespan make it difficult to determine which children should receive palliative care and when to start it. This uncertainty undermines communications between providers and families, who are generally more optimistic about a child's condition than the former and thus (perceived to be) hesitant about implementing palliative care in a timely fashion. Another insidious obstacle is the conceptual confusion between palliative and hospice care among both parents and healthcare providers. Interestingly enough, two recent papers (Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Inglin and Abbruzzese2013a ; Twamley et al., Reference Twamley, Craig and Kelly2014) reported that, even in the case of adequate knowledge of and support for PPC principles, healthcare staff unwittingly associate palliative care with end-of-life care, highlighting society's inexperience with childhood death. A limited number of manuscripts focused on conceptual and operational shortcomings within the guidelines (among others, see Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Inglin and Abbruzzese2013a ; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Contro and Koch2014).

Table 3. Barriers to pediatric palliative care

PPC = pediatric palliative care.

Recommendations to Overcome barriers to Implementation of PPC

Seven areas of improvement were presented in the papers to help get around the barriers to PPC implementation noted above (see Table 4). Training and education of healthcare staff (and parents) were the most frequently listed recommendations to overcome operational barriers, although there were few references to precise teaching and training methods. Various papers identified training in pain and symptom management necessary to assess and alleviate pain in a timely manner and to confute the myth of opioid addiction among children. Education about the principles of PPC was considered crucial to avoid any conceptual confusion between hospice and palliative care. In particular, the principle of early integration (from diagnosis onward) was frequently cited as a way to make palliative care more acceptable. The underlying idea was that, if palliative and curative treatments are implemented at the same time, gradual transition of goals can occur. For the same reason, many studies emphasized the need to seek for the support of the PPC team (or specialized nurse) at an early stage. They could function as a kind of “glue” between families and primary care staff. Several papers also insisted on the importance of open and honest communication about prognosis and death and the need for guidelines to prepare parents and siblings for the child's death. Some articles spoke of the need for reflective practice among healthcare staff to address their (often unconscious) negative attitudes toward palliative care as end-of-life care. Four articles discussed advance care planning as a way to facilitate this process. Closely connected to this is the concern with structured bereavement care (during and after a child's death) to support patients, families, and healthcare staff in their grief and moral distress. Two papers provided recommendations for spiritual care. Several insisted upon the need for evidence-based research in order to develop clear standards for various subfields of PPC.

Table 4. Recommendations for pediatric palliative care

PPC = pediatric palliative care.

DISCUSSION

In light of the increasing number of children with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions, national and international organizations have developed a holistic and integrative model to care for this group and their families, as well as to provide guidance for healthcare professionals. Although PPC is gaining momentum, there is still an important gap between the guidelines and their implementation into medical practice. Our literature review identified strategies on how to overcome this gap so that all children who are eligible for PPC services might receive them. From the 54 studies included in the review, we found that most have looked at this problem mainly from a policy, clinical, or societal point of view, while only a few have examined the practical and conceptual pitfalls inherent to the guidelines. Our review suggests that some PPC principles are not always easily translated within a medical setting—they are seen as too theoretical to be able to deal with the complexity of the different stages of illness.

Some Trends Throughout the Literature

Upon exploring the development of guidelines, we have found several trends that highlight both the emerging and continuing challenges faced by PPC over the last six decades.

First, the very limited number of studies before 1998 is an indication of the slow growth of PPC. At the same time, the literature from this time period expressed an increased interest within the medical field for practice guidelines that inform staff and parents about the management of chronically ill and dying children. From 2000 onward, there is a growing recognition of the important role that guidelines play in the further diffusion of PPC. This is testified to by the steady increase in the number of publications. With the development of specific PPC guidelines, the main concern is the lack of palliative care services due to the absence of adequate policy support (such as health insurance or national strategies that permit broad access). Attention is further placed upon the differences in availability of PPC services both across and within countries. In the studies published from the late 2000s onward, however, this concern takes a different form. There is an uncomfortable awareness that, despite increased policy support and available services, PPC is not readily accessible to all the children who could benefit from them.

Second, the inadequate implementation of PPC guidelines is mainly attributed to shortcomings within clinical practice and a lack of empirical research on PPC. This explains why recommendations concentrate primarily on educational and training programs for healthcare staff (including critical self-reflection), on the importance of multidisciplinarity (in particular, on the integration of PPC specialists into the primary care team to sustain the staff and guarantee seamless care without brusque transitions), and on the need for more evidence-based research on the benefits of PPC. The latter concern is manifested in the increase in empirical research on the perceptions of parents and caregivers with regard to PPC from 2003 onward.

Third, the publications in the 2000s became more careful in respecting a clear conceptual distinction between hospice and palliative care. Although the hospice movement has been important to break the veil of silence surrounding death, these papers emphasize that this type of care should be redefined in function of the challenges posed by pediatric healthcare. They also underline that hospice care, due to its association with death, is still rife with stigma. Therefore, in line with the guidelines and motivated by the prognostic uncertainty within pediatrics and the family's improved quality of life, they embrace the paradigm shift within palliative care from a strict dichotomous to an integrative approach.

Finally, among the 54 included articles, 21 focus on end-of-life issues; however, only 4 of them date from the period between 2010 and 2015. Two of these four studies focus on bereavement care in relation to the family and caregivers, and thus not directly on the death of the patients. This indicates that, for a long time, death and dying were considered to be central aspects of palliative care, whereas this connection has become less important recently. This finding is in line with those of other studies have highlighted the strained relationship between palliative care and the reality of death (Bergstraesser, Reference Bergstraesser2013; Cacchione, Reference Cacchione2000; Pastrana et al., Reference Pastrana, Junger and Ostgathe2008; Trotta, Reference Trotta2007).

Some Missing Links and Prospects for the Future

Despite being a core principle of PPC, only a small number of publications report on the absence of clear guidance in PPC documents regarding bereavement care, the challenges of multidisciplinary care teams (e.g., hierarchy, competing values, communication), and training methods. More research needs to be done on bereavement care pathways (ACT, 2009b ) and effective teamwork. Also, further study is needed of effective teaching and training methods in regard to palliative care (Yazdani et al., Reference Yazdani, Evan and Roubinov2010).

Another difficulty is linked to providing palliative care “from diagnosis onward.” Although considered necessary to promote the acceptance of PPC, within medical practice it is often seen as unfeasible. Tools that can help physicians identify children and families with palliative care needs can be a way to address this concern and advance PPC. Some of these referral instruments are already under development (Bergstraesser et al., Reference Bergstraesser, Hain and Pereira2013b ; Shaw, Reference Shaw2012).

Closely connected to the previous point, although PPC is not only meant for imminently dying patients, the question is whether the pendulum has not swung too far from end-of-life issues (Bergstraesser, Reference Bergstraesser2013). Palliative care has increasingly profiled itself as a more holistic medicine and as an alternative to the technical dehumanized medical tradition. This overall emphasis on quality of life and matters concerning the living might have contributed to the conceptual confusion around palliative care among both physicians and the lay public (Bergstraesser, Reference Bergstraesser2013).

Having considered all of this, a critical assessment of both the research guidelines and medical practice is indeed needed in order to improve the implementation and outcomes of PPC care.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

For this systematic literature review, a total of 54 studies were assessed. Our results should be interpreted with caution, as articles in languages other than English and German have remained unexplored. Some studies relevant to the issue might have been overlooked as a result of the search terms chosen. Aside from these limitations, ours is one of the first studies to explore barriers and recommendations for proper implementation of palliative care from the perspective of PPC guidelines in order to overcome the gap between recommendations and practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The evolution of guidelines in PPC confronts us with a true paradox: while in the 1980s and 1990s there was an increasing demand on the part of healthcare professionals to develop clear palliative care standards that would take into account the uniqueness of the pediatric population, two decades later there is a reluctance on the part of healthcare professionals to implement the model that was specifically developed in function of that population. Most studies address either the clinical gap or research gap to address this paradox. Accordingly, the recommendations found in a wide range of articles are related to the need to focus on training, education, and evidence-based guidelines. Future studies should continue to pursue empirical research on PPC and foster comprehensive educational and implementation programs that would make PPC an inextricable part of pediatric medicine. Aside from research on the perceptions of caregivers and parents about PPC, more research is needed from the child's perspective in order to gain better insight into their needs and preferences, and thus enhance PPC services. With some important exceptions (e.g., Hsiao et al., Reference Hsiao, Evan and Zeltzer2007), the child's perspective on PPC is missing. Finally, to better align guidelines and medical practice, studies should begin to focus on the conceptual and practical shortcomings of published PPC guidelines.