Introduction

Dignity and its multiple dimensions have always been central goals within medicine and especially among terminally-ill patients and their relatives being cared for in palliative care. In contemporary patient care, the concept of dignity is imperative (Julião, Reference Julião2015) as a means of shifting the culture of care from one dominated by patienthood to one that is inclusive of personhood, not only for adult populations but also for younger people living with advanced illnesses. Research on dignity in the terminally-ill began to emerge with the seminal work of Chochinov et al. (Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002), with the construction of the Dignity Model of the terminally-ill and the subsequent creation of dignity therapy (DT; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005). DT is a brief, individualized intervention, which provides terminally-ill patients with an opportunity to conveying memories, essential disclosures and prepare a legacy document, addressing psychosocial and existential issues, and bolstering a sense of meaning and purpose. During DT, trained therapists guide a psychotherapeutic session based on a framework of questions (coined the DT question framework [DT-QF]) developed from key tenets of the Dignity Model. DT is presently well established in adult populations, with international research supporting its effectiveness and a recent literature review reporting robust evidence for DT's overwhelming acceptability, rare for any medical intervention, especially in psycho-social–spiritual care (Fitchett et al., Reference Fitchett, Emanuel and Handzo2015). Similar approaches need to be integrated into care plans for terminally-ill youth, thereby improving their quality of life. In a structured review aimed at summarizing and synthesizing the research that explored DT and related meaning-making interventions in palliative care in young populations, Rodriguez et al. (Reference Rodriguez, Smith and McDermid2018) found only one study focusing on young people (7–17 years), using a DT-based approach, where participants engaged in digital story-telling with the help of a professional videographer to document their experiences and stories through visual media (Akard et al., Reference Akard, Dietrich and Friedman2015). The authors of the review concluded that few studies have included people 24 years of age and younger, indicating a clear gap in the literature and the need to develop and evaluate DT and related meaning-making interventions to support younger people.

To the best of our knowledge, DT-QF has never been adapted to the Portuguese adolescents' population. To explore the utility and application of the DT-QF for Portuguese adolescents, we conducted a study aiming to adapt the Portuguese adult DT-QF for adolescents.

Methods

Measure under study: DT and the QF

DT is a brief psychotherapeutic approach designed to bolster the patient's sense of meaning and purpose, reinforcing a continued sense of worth within a framework that is supportive, nurturing, and accessible for those near death (Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2011). Patients enrolled in DT are guided through a conversation, in which aspects of their lives they would most want their loved ones to know about or remember are audio-recorded. DT offers patients the opportunity to talk about issues that matter the most to them, to share moments that they feel were the most important and meaningful, to speak about things they would like to be remembered by, or to offer advice to their family and friends. These recorded sessions provide the basis of an edited transcript or generativity document, which is returned to patients for them to share with individuals of their choosing. Therapeutic sessions, usually running between 30 and 60 min, are guided using an interview framework — DT-QF — comprised of 12 questions that are based on the fundamental tenets of the Dignity Model (Figure 1). Each question is meant to elicit some aspect of personhood, provide an opportunity for affirmation, or help patients reconnect with elements of self that were, or perhaps remain, meaningful or valued. Although there is far more to delivering DT than simply posing each of the protocol questions, the framework provides a guide to eliciting a legacy-based therapeutic intervention. Before performing DT, patients are provided with the standard framework of questions, thus giving them time to reflect and shape their eventual responses. The DT-QF is not intended to be rigid or prescriptive. Trained therapists have the latitude and responsibility to explore other legacy-related issues and must skillfully guide the flow of DT based on patients' interests, cues, and individual responses. Hence, it is critical that DT therapists assume a facilitative and attentive role while guiding DT based on the framework of questions. Performing DT and using DT-QF should follow the protocol as described by Chochinov (Reference Chochinov2011), and DT therapists should have formal training with DT.

Fig. 1. The adult Portuguese DT-QF (Protocolo de Perguntas da Terapia da Dignidade para Adultos).

The Portuguese adult DT-QF version (Figure 1) was already published elsewhere (Julião, Reference Julião2014) and has been used in the Portuguese population (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014, Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2017).

Study phases

The development of this study was comprised of five different stages between the period of June to October 2018.

First, after obtaining permission to adapt the adult DT-QF for adolescents from the original author (HMC), the principal investigator (MJ) — an experienced and trained DT therapist and researcher — adapted the Portuguese adult DT-QF to an initial version of the DT-QF-Adol, based on his expertise, including clinical experience in caring for adults and children with complex palliative needs. This initial adapted framework of questions was independently translated to English by a bilingual native Portuguese and sent to DT's original author (HMC) who agreed that the initial version created for adolescents captured the fundamental elements of the Dignity Model and DT itself.

The second step consisted of an expert committee panel analysis on the DT-QF-Adol. The panel was comprised of 20 members, previously introduced to the fundamental aspects of DT and question protocol, three of whom were formally acquainted with DT. The expert panel was composed by pediatricians, adult and pediatric palliative care physicians, family physicians, adult and children psychologists, pediatric palliative care nurses, and a child psychiatrist. Panel members were asked to provide feedback on the Portuguese DT-QF-Adol initial version regarding the following: (a) overall approval of the adapted version, (b) belief that the questions' framework captured fundamental dimensions of personhood and dignity-related issues pertinent to adolescents and their lived experiences, using their clinical expertise, (c) clarity, (d) comprehensibility and ambiguity of each item, and (e) comments, amendments, and possible inclusion of other relevant questions or supporting ideas.

After receiving all the expert input, an initial consensus version of the DT-QF-Adol was created with at least 80% agreement between experts. After completing the latter, the expert committee was reconvened for the second and final round of analysis on the revised DT-QF-Adol. They were asked to provide any additional revisions. To resolve any discrepancies, an agreement was obtained by consensus, with the final consensus set at least 80% agreement. To strengthen the process, a linguistic expert was consulted and no changes were deemed necessary. Experts were also asked to provide any additional feedback, including how this could inform their practice, assist patients and families, and to reflect on the age range of patients appropriate for this intervention.

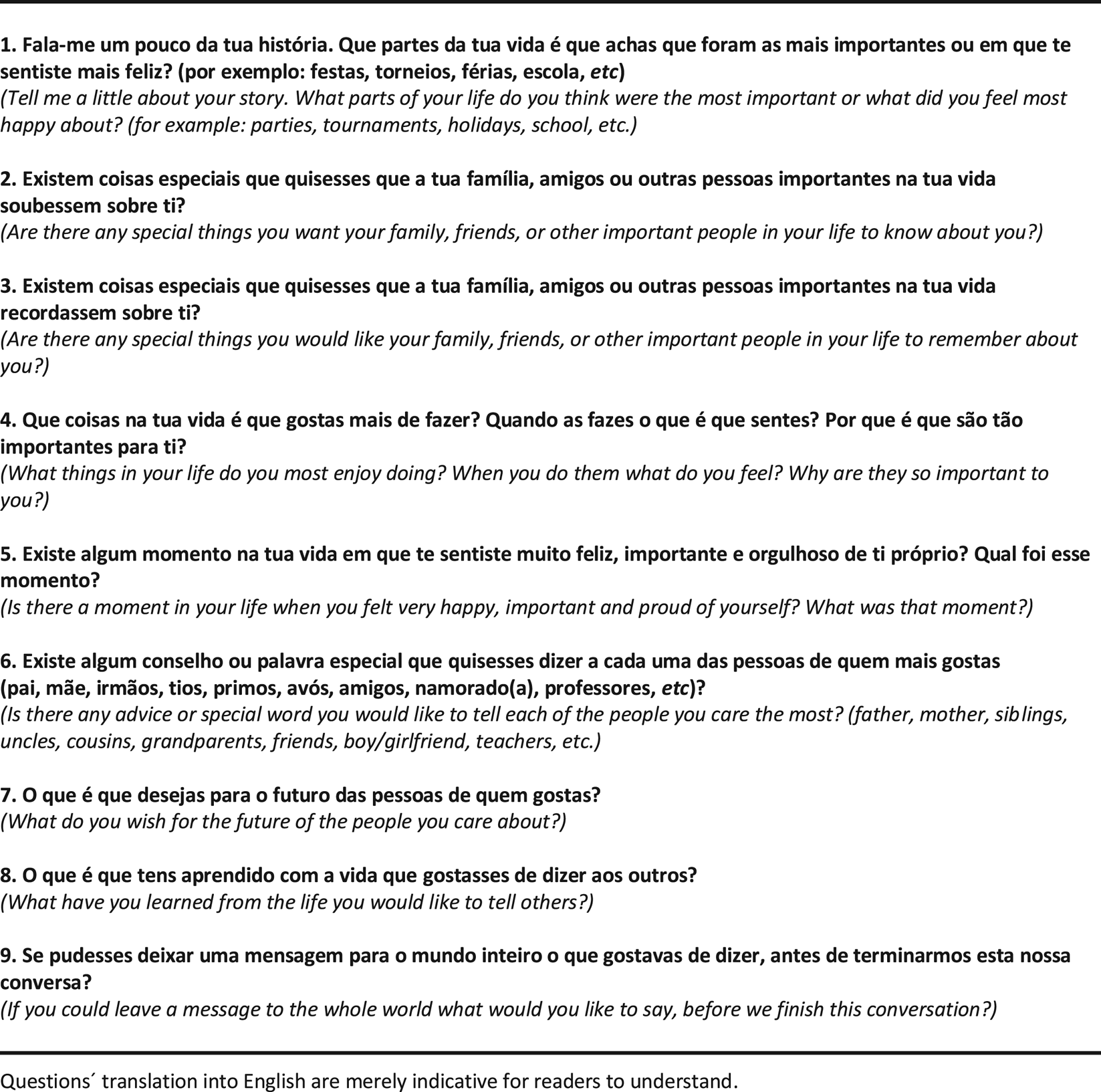

The last stage was the validation process of the final consensus DT-QF-Adol version (Figure 2) using a sample of adolescents followed in an ambulatory psychology clinic.

Fig. 2. The Portuguese DT-QF-Adol (Protocolo de Perguntas da Terapia da Dignidade para Adolescentes – 10–18 anos).

Data collection

Between June and October 2018, adolescents from an ambulatory Psychology Clinic in Lisboa (PIN — Progresso Infantil) were invited to participate in the study by an adolescent psychologist (AS). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) adolescents understanding the study's objective, willing to participate and able to provide written informed consent, (b) regular psychology follow-up in the clinic, (c) parents willing to provide written informed consent, and (d) ability to read, speak, and understand Portuguese. Subsequently, AS verified eligibility, obtained parent's informed consent, and sociodemographic data. In this first research contact, an explanation of DT was provided, along with being told they were being invited to take part in a revised form of this intervention specifically designed for very sick adolescents, living with a life-threatening disease. It was also mentioned that her/his participation in the study could be very helpful to those adolescents in need of holistic and person-centered care at the end of life. A second research contact was planned one week later, in which each participant was given the time to ask questions about the study protocol and was reassured that emotional support would always be available during the interview and/or afterwards if needed. The adolescent received a printed copy of the DT-QF-Adol (alone or with AS) and think about the answers they imagine that others would feel most comfortable in sharing if diagnosed with a life-limiting condition. After completing this initial part, participants were asked to complete a feedback questionnaire on their appreciations, perceptions, and effectiveness of DT-QF-Adol (rated on a Likert scale: 1 “strongly disagree” – 7 “strongly agree”) (Table 1). Adolescents were also invited to write a comment at the end of the questionnaire. No qualitative analysis was performed. These data are presented in Figure 3, illustrating the acceptability adolescents felt toward DT-QF-Adol. This study received ethical approval from the PIN — Progresso Infantil Ethical Advisory Board.

Fig. 3. Written comments by the participants in the feedback questionnaire.

Table 1. Participants' appreciations on the DT-QF (N = 17)

DT-QF, Dignity Therapy Question Framework; SD, standard deviation.

a Responses rated on a Likert scale: 1 “strongly disagree”—7 “strongly agree”.

b 1 invalid answer.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) software 23.0 for Windows®. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and responses to the feedback questionnaire.

Results

The Portuguese version of DT-QF-Adol was coined Protocolo de Perguntas da Terapia da Dignidade para Adolescentes — 10–18 anos. The full questionnaire is presented in Figure 2.

Expert panel

According to the experts' evaluations and experience working within the pediatric and palliative care setting, the Portuguese DT-QF-Adol was clear, precise, comprehensible, and captured critical dimensions of personhood as well as core issues pertinent to facing adolescent existence. To those experts acquainted with DT and its protocol, this Portuguese DT-QF-Adol was well aligned with the core fundamental aspects of the dignity conserving care tenets. The experts also added that offering DT to the pediatric palliative care population would be of great importance and could add additional value to their care plans as one more effective and useful tool that supported dignity, quality care, and remembrance for both relatives and health professionals. There was a 100% agreement on the final version, with ages 10–18 deemed most appropriate.

Participants

Seventeen adolescents out of 20 who were invited to take part in the study agreed to do so. Three participants were excluded as their parents declined participation, in fear that answering these questions could affect their child's psychological wellbeing (85% response rate). Nine out of 17 participants were female. The average age was 12.7 years, ranging from 10 to 17. No participant was diagnosed with a serious/advanced disease. Participants' characteristics are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary characteristics of the participants (N = 17)

SD, standard deviation.

a Life-related events: parents' divorce.

The interviewed adolescents considered that the DT-QF-Adol was clear (5.8, SD = 1.7), and they did not identify any ambiguity (2.1, SD = 1.6) or difficulty in answering questions (3.5, SD = 2.4). They assumed that this information could positively affect the way parents (6.6, SD = 0.5) and friends (6.3, SD = 0.7) see and care for them, allowing others to understand their concerns (5.4, SD = 1.9) and preferences (5.7, SD = 1.6). Participants felt that the DT-QF-Adol could be a good starting point for a conversation with their loved ones (5.7, SD = 1.0) (Table 1).

Adolescents considered vital for health professionals to access their answers (5.0, SD = 2.4), and they also felt strongly that the DT-QF-Adol might be essential to sick adolescents (6.4, SD = 1.1) and they would recommend it to others (6.4, SD = 0.9). When asked about the format for their responses, 8 of 17 of the participants would prefer the audio recording, followed by the written text (7/17), the video (2/17), and only one adolescent chose other formats, i.e., “face-to-face” (Table 1). All participants were comfortable with the questionnaire and saw no need for emotional support.

Discussion

This study reports the adaptation of the Portuguese version of the DT-QF-Adol coined Protocolo de Perguntas da Terapia da Dignidade para Adolescentes — 10–18 anos. Overall, participants found the measure clear and easy to understand. They saw applications for adolescents with life-limiting conditions regarding their life experience and indicated that it could influence how health professionals and family members would see them and remember them. The expert panel considered the measure captured aspects of personhood and described it as a useful tool to use in practice. They felt that if used in adolescent patients with life-threatening and life-limiting conditions, it could enhance quality care and contribute toward the creation of a personal legacy and remembrance.

Most participants seem to grasp the importance of the subject being discussed (see Figure 3), regardless of their age. This is important, given that adults tend to act as gatekeepers to protect children from thinking about more serious situations and sad life events. However, adults may be more reluctant to have their children to address these issues than are children themselves. In our sample, even younger participants had useful insights and reflections on how this would apply to those their age facing significant life-limiting illness. For this reason, we believe that adolescent patients can engage in this intervention, being mindful of their individual development, even though 10 year olds and 17 years old have distinct cognitive and emotional developmental differences, they can potentially benefit from this intervention, at their own developmental level.

It is well established that children as young as 8 years old may respond in socially desirable ways when answering questions posed by an adult, especially if they are in a questionnaire format resembling a school test situation (De Leeuw, Reference De Leeuw2011). By providing the questionnaire before the interview date and explaining that this intervention was about other adolescents facing critical illness, that there were no right or wrong answers, and that they could drop out of the study at any time, we believe reduced any social desirability bias.

The main limitation of our study is that the sample used came from one site only (private psychology practice) and participants were not diagnosed with a severe illness.

In the future, it would be important to test the impact of the Portuguese DT-QF-Adol on the intended population, determining its acceptance and how they feel about the information that it elicits. Furthermore, it would also be essential to understand how health care providers feel about the information gathered by way of DT-QF-Adol, given that it may offer healthcare providers insight into the patient narrative, thereby enhancing their response to patients' emotional and spiritual needs. Finally, it would be interesting to see if the Portuguese DT-QF-Adol influences Portuguese health care professionals' attitudes, care, respect, empathy, compassion, and sense of connectedness with patients and their families and if it heightens their personal satisfaction in providing care.

The Portuguese DT-QF-Adol is clear, precise, comprehensible, and well aligned with the fundamentals of DT and personhood. This tool has the potential to enable an intervention which will enhance pediatric palliative care. Future research on end-of-life adolescents is now warranted, namely to pilot test the QF regarding its clinical applications and also the translation of the DT-QF-Adol into other languages, enabling the conduct of DT trials in adolescents with advanced disease. As with adult DT, the future use of this tool by healthcare professionals in clinical practice as an intervention is subject to previous formal training and understanding of the Dignity Model and DT. It is important to learn with examples from the past, which have proved that interventions without testing and without training can be and are harmful not only for patients, but also for their families and formal and informal carers.

Contributors

MJ, BA, and AS were responsible for the conception and design. They were responsible for supervising the study, analyzing the data, and writing the initial draft and final report. AS and SA were responsible for the collection and assembly of data. All co-authors supervised the statistical analysis, revision of the final report, and had full access to all of the data.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank João for triggering the need for this research and each adolescent and parents who agreed to enter our study. The authors also owe a special word of gratitude to Dr. Nuno Lobo Antunes for supporting the study and sincere thanks to the following elements who participated in the expert panel: Cândida Cancelinha, Elisabete Bento, Emília Fradique, Hugo Lucas, Isabel Cunha, Joana Mendes, Márcia Cordeiro, Mafalda Lemos Caldas, Maria Jesus Moura, Margarida Crujo, and Susana Corte-Real.

Funding

Bárbara Antunes is funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) PhD Fellow Grant number PD/BD/113664/2015 Doctoral Program in Clinical and Health Services Research (PDICSS) funded by FCT Grant number PD/0003/2013; Filipa Fareleira is funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) PhD Fellow Grant number PD/BD/132860/2017 Doctoral Program in Clinical and Health Services Research (PDICSS).

Conflict of interest

None exist.