1. Introduction

Listeners experience electroacoustic music as full of significance and meaning, and they experience spatiality as one of the factors contributing to its meaningfulness. Perceived sound is always spatial, and spatiality is an integral part of every auditory experience. Sometimes the spatiality is in the foreground of attention and is a primary conveyor of meaning. At other times, it slips into the background. If we want to understand spatiality in electroacoustic music, we must understand how the listener’s mental processes give rise to the experience of meaning.

The feelings and thoughts that the listener associates with the experience of sound in space appear to arise from a deeply embodied knowledge of space and spatial movement. This spatial knowledge is acquired through sensory experience that presumably starts at the beginning of life and continues through interactions with the everyday world. Notions of space, acquired and understood through bodily experience, underlie a great deal of our everyday thinking. Spatial analogies and spatial metaphors run through our language and our reasoning. It is no wonder then that space can be a potent component of meaning in electroacoustic music.

When considering multichannel loudspeaker systems in particular, an important part of the discussion should be focused on the distinctive and idiomatic ways in which this particular mode of sound production contributes to and situates meaning. The listener’s experience depends on many factors, among which are acoustic factors that directly affect the listener’s spatial hearing and ultimately influence the spatial meanings understood by the listener. In particular, there are many idiosyncrasies to spatial perception with multiple loudspeakers that distinguish it from other forms of audio reproduction and which contribute to its distinctiveness. Concerts of electroacoustic music in multichannel reproduction are also an artistic idiom in which the listener’s prior experience and understanding play a key role in the apprehension of artistic meaning.

1.1. The chain of (dis-)connection

Auditory spatial imagery and spatial meanings can arise when listening, when remembering or when imagining. This tells us that the listener’s spatial capabilities are not simply a product of immediate perception. Listeners think spatially. The spatial meanings that the listener experiences when sitting in an audience are the final result of a complex chain of thoughts and actions. At one end of the chain is the work of the composer imagining spatial meanings and auditioning sound while assembling the composition’s components. The typical products of this effort are the tracks of sound brought to the concert hall and the directions for how these tracks are distributed among loudspeakers. At the time of the performance, there may be someone, possibly the composer, who manipulates the reproduction system and performs live diffusion. This person brings his or her own intentions for spatial meanings and nuance to the situation. The sounds projected into the hall provide the stimuli for the audience members’ experiences, which may be quite diverse. For one thing, these listeners are spread about in different locations that affect their perceptions. They also have different reasons for being present, different associations with the sound sources, different levels of experience with electroacoustic music, and so on. There are bound to be variations in the apprehension of meaning that are shaped by the situation, by intention and more.

In the midst of all this diversity, there remain some fundamental commonalities in listeners’ experiences. Some of these commonalities arise from the general characteristics of spatial hearing, which are relatively uniform across all people. This enables us to discuss many details of multichannel perception in terms that are applicable to all listeners. Also, given the commonalities of living in the everyday world, we can assume that the audience members have many shared experiences and understandings of everyday spatial relationships that evoke shared meanings. Given the specifics of any particular listening situation, there are just so many percepts and plausible understandings for a listener who is attentive to the experience.

The goal of spatial audio in electroacoustic music should be to evoke experiences in the listener with artistic meaning: in particular, meaning emerging from the spatiality of the perceived sound. Therefore, the goal of a multichannel audio system should be to deliver acoustic signals to the ears of the listener that provide the stimulus for such artistic spatial experiences and understandings. The more that we understand about the complex relationship between spatial sound systems and the listener’s spatial thinking, the better we will be able to harness the capacities of such systems for artistic purposes.

2. Spatial audio and spatial cognition

2.1. The spatiality of events

When a listener hears sounds in space, what the listener perceives and understands can be most accurately described as events that take place in space (Kendall Reference Kendall2008). These are events that typically involve objects, actions and agents. Over the course of human maturation, each person gradually learns to understand more complex and more nuanced relationships among these three. Events and their object–action–agent constituents are experienced through multiple sensory modalities, and one’s grasp of sensory experiences as events is fundamentally multimodal. So it is not surprising that, when listeners have sensory experiences of sound alone, they are able to make sense of these experiences as events that take place with objects, actions and agents, even though these constituents may be unobserved, obscure or unknowable. Importantly, we also understand events as intrinsically spatial because events take place in space. Listeners can often infer the physical scale of the actions, objects and agents that produce events, as well as the likely physical context in which events take place. These are conceptual properties of how the listener understands what is heard, the conceptual event that the listener envisions.

When one listens to recorded sound, the recording and reproduction system mediates between the original acoustic events and the signals that finally reach the listener’s ears. This mediating system may have some effect on the fidelity and timbre of the perceived events, but it almost certainly has an effect on the spatial experience of the listener, spatiality being the aspect that is generally the least well preserved. The spatial image of an orchestra performing may appear to emerge from between a pair of stereo loudspeakers or, in the case of headphone listening, it may appear inside of the listener’s head. Human beings adapt their understanding to these shifts of scale and perspective with amazingly little effort.

This illuminates an important distinction between the spatial properties of the conceptual event and the spatial imagery that the listener experiences directly. The two may have little to do with one another. On one hand, the direct perception of auditory spatial relationships is one of the ways in which humans develop their multimodal conceptual understanding of events. On the other hand, the conceptual event may influence and constrain the perceptual image: for example we are more likely to hear an airplane above our heads than below us. There is a constant interaction between immediate perception and our understanding of the world around us. Clearly what we perceive can be influenced by what we expect. Importantly, in the context of electroacoustic art, the listener must relax the tight grip of plausibility to accommodate potential artistic meanings that arise from unexpected or novel spatial relationships. This is the same way that we relax our framework of spatial relationships when viewing a painting that stretches and distorts space for expressive purposes.

2.2. The attributes of spatial imagery

The perceptual attributes of the spatial imagery produced with loudspeakers have been well studied by researchers in the audio engineering community who often describe this as research into spatial quality. There is a long history of studies that connect the attributes of spatial imagery with specific terminology (Zacharov and Koivuniemi Reference Zacharov and Koivuniemi2001; Berg and Rumsey Reference Berg and Rumsey2003). Particularly instructive for our purposes is an article by Rumsey (Reference Rumsey2002) in which he proposes a framework for a very concise vocabulary. Rumsey’s spatial attributes start with the dimensional attributes among which he includes distance, width and depth. He then goes on to describe the immersive attributes, which he separates into presence (‘being inside of an enclosed space’, 2002: 662) and several kinds of envelopment (being surrounded by sound). Rumsey’s article provides a cogent conceptual foundation for describing spatial imagery, but his list of attributes is somewhat limited because of a focus on conventional recordings and reproduction systems. In order to itemise the spatial attributes of electroacoustic music reproduced with loudspeakers, the list must be slightly enlarged.

Dimensional attributes:

• Direction

• Distance

• Extent: depth, width and height

Immersive attributes:

• Presence

• Envelopment

To Rumsey’s original list, we have added direction, which was not relevant to Rumsey’s original discussion, and height, which is important for systems with loudspeakers at multiple levels of elevation. We have also grouped together the three attributes that relate to spatial extent as depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1 Illustration of the attributes of spatial imagery in loudspeaker reproduction.

Undoubtedly, the most important contribution of Rumsey’s article is that these spatial attributes characterise spatial images that range from the micro- to the macro-level. Rumsey proposes a scene-based paradigm organised in terms of sources, ensembles, rooms and scenes. For Rumsey these are hierarchic groupings: sources maybe grouped into ensembles that are contained within rooms that are enclosed within scenes. Rumsey’s terminology may only have been intended to describe the spatiality of conventional recordings, but his concept can easily be extended to describing spatial imagery in electroacoustic music (see Emmerson Reference Emmerson1998 and Smalley Reference Smalley2007 for related concepts). And yet, there are two fundamentally different ideas at work, one in relation to the spatial image and the other to the conceptual event. In the first case, Rumsey’s levels provide a way of thinking about the spatial arrangement of images: inclusion, aggregation, overlapping, and so forth. In the second case, these are ways in which the listener makes cognitive sense of auditory phenomena. For example, identifying a plurality of sound events as an ensemble signifies a category in which there is a likely commonality of behaviour. A spatial image by itself may or may not have this conceptual characteristic. Then, too, the notion of room is not merely a particular kind of source with spatial attributes, but also an understanding in which one thing contains another. Rooms can contain sources, ensembles and sometimes listeners. Importantly, the perception of envelopment and presence may influence the listener to assume a perspective from inside the room. But as Kendall (Reference Kendall2007) points out, in audio reproduction the room can just as easily be reduced to a narrow point source with the listener on the outside. Once again, the spatial imagery that is directly perceived and the conceptual spatial organisation that is understood are potentially quite distinct.

2.3. The space around the body

How the listener experiences artistic meaning in auditory spatial art depends greatly on the everyday experience of space, and clearly the listener’s most important spatial framework is anchored in the body. For example, the separation of left from right defines a primary axis for the body’s space, the one axis of the body that is truly symmetrical. We understand the left–right axis first and foremost as a bodily distinction. The separation of the ears along this axis gives rise to the interaural differences in time and intensity that are cues to the direction of sound events. In directional hearing, the left–right axis is fundamental. Left–right judgments are the least error-prone and the greatest directional acuity is centred in the middle of this axis. People seldom misjudge whether a sound is on the left or right.

The front–back axis is another axis of bodily symmetry and is fundamental to manoeuvring our way around in the physical world. Both the orientation of the eyes and the means of locomotion accentuate the distinction between what is in front and what is behind. In directional hearing, the front–back distinction is very dependent on the dynamic movement of the head, which clarifies what is in front from what is behind. Secondarily, the front–back distinction depends on the acoustics of the pinnae, which face forward and create spectral differences between sound events from the front and the back. Front–back distinctions are somewhat error prone, especially in the absence of head motion.

The up–down axis is experienced differently from the other axes. For one thing, it is the axis that aligns with gravity, and gravity imbues it with special significance. It has forces at work on the body and the environment. Gravity binds figure to ground and defines the ‘floor’ of the space. We rarely travel vertically in an acoustic environment or experience sound events below us. In directional hearing, elevation cues are primarily provided by the acoustics of the pinnae, which are completely asymmetric from top to bottom. Elevation perception is the least accurate. Directional hearing above the head is very imprecise and directional hearing below the body is almost non-existent. Importantly, the acoustic cues to elevation created by the pinnae are confounded with the spectral characteristics of the sound source. In general, the higher the spectral energy distribution of the source, the higher the perceived elevation. This is verified in listening tests with a variety of filtered signals (Bloom Reference Bloom1977; Roffler and Butler Reference Roffler and Butler1968a, Reference Roffler and Butler1968b; Susnik, Sodnik and Tomazic Reference Susnik, Sodnik and Tomazic2005). In general, high-frequency sound events appear more elevated than low-frequency events, and bright events appear more elevated than dark ones.

The deeply meaningful sense of space that is aroused when listening to electroacoustic music has its roots in a lifetime of embodied spatial experience. Beneath the apparent continuity of everyday space are the axes of the body giving structure and context to the experience of spatial events. For example, objects, actions and agents are most easily grasped in terms of the familiar: objects that are manipulated by one’s self. It should come as no surprise then that so much of the spatial movement in electroacoustic music is curved like the movements of the body. Then, too, in the context of the body, motion requires effort. The listener’s felt experience of spatial motion in electroacoustic music is typically imbued with the flow dynamics of bodily effort. (See Kendall Reference Kendall2010 for a discussion of events and felt experience.)

2.4. The space of the mind

From our preceding discussion, it should be obvious that the axes of spatial hearing are quite different from each other. For a practical understanding of the space around us to emerge, it cannot simply be constructed moment-to-moment from immediate perception. Our understanding must have persistence and it must be independent of any one perceptual modality (though there is good evidence that vision plays a pivotal role in the evolution of our spatial understanding, Thinus-Blanc and Gaunet Reference Thinus-Blanc and Gaunet1997). Our everyday spatial activities are taken in through the senses and integrated into and in accordance with our ongoing mental representation of the world around us. But the space of the mind is not the space of the physical world. The space of the physical world is stable and requires no effort to be maintained. The space of the mind is an active construct that is dynamic and seeks conformation. If one compares a particular space as conceived with the actual physical space, the conceptual space is typically distorted in comparison to the physical space (Tversky Reference Tversky2009: 202).

One factor that aids listeners in maintaining their spatial framework is their ability to keep track of the location of things. If we turn during a sound event, it remains fixed relative to the environment. Even multiple events maintain their relative positions despite rotations of the body. The way in which such relative positions are preserved helps us to construct a stable sketch of what is going on around us. Dynamic changes in a sound event, say changes in pitch and timbre, may aid us in updating our understanding of the event, but we do not need constant perceptual input to maintain our notion of where things are located. The persistence of a plausible location in the face of contradictory acoustics is illustrated by the Franssen effect (Hartmann and Rakerd Reference Hartmann and Rakerd1989), which demonstrates that listeners must be mentally constructing and updating some form of spatial representation in which events have spatial persistence. A corollary to the fact that ‘events’ are intrinsically multimodal is that we expect them to be multimodal. If we see a glass drop to the floor, we expect to hear it too. This helps us to understand the influence of vision on the plausibility of auditory spatial perception. Events with visible sources are more plausible than ones where nothing can be seen.

All of this reveals how the mind sustains spatial thinking. At early stages of development, there is presumably a great deal spatial learning and testing while we develop our ability to think in terms of space. It becomes imagined space and even metaphorical space. Recurrent patterns of spatial thinking become codified at many different levels of specificity. For example, Lakoff and Johnson discuss image schemas, which capture some of our most basic spatial patterns (Johnson Reference Johnson1987; Lakoff Reference Lakoff1987; Lakoff and Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999). One of these is the image schema Object that captures the spatial commonalities of everyday objects such as the fact that objects have a location in space (Johnson Reference Johnson1987). Over a lifetime, we have also learned the acoustic behaviours that we associate with Object, such as the fact that actions can cause a sound to emanate from the object’s location.

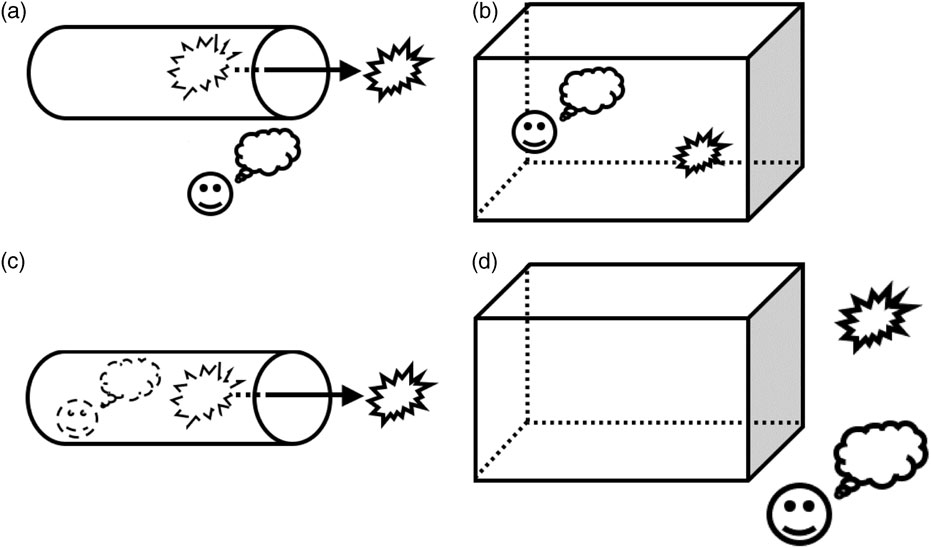

In electroacoustic music, one of the ways in which spatial events take on artistic meaning is by violating the acoustic behaviours that we associate with image schemas. Kendall (Reference Kendall2007) discusses how the typical acoustic behaviours associated with the schema Containment can be violated by signal processing to situate listeners inside a container where they should not be. (This happens in Denis Smalley’s Empty Vessels when the listener’s perspective is shifted inside of a large garden pot.) Listeners and rooms can also be separated from each other in violation of the acoustic behaviour expected of the schema for Room. These examples are illustrated in figure 2. How image schemas help us to make sense of events that are difficult to grasp is illustrated by the image schema Path, which can imbue fragmented spatial movement with a sense of coherence. Then, too, Path can provide a thread of continuity to a combination of events moving along a shared trajectory (figure 3). The continuity of Path psychologically implies some continuity of agency or action.

Figure 2 The schemas for Container and Room are represented in (a) and (b); (c) and (d) illustrate violations of those schema easily produced through spatial DSP (after Kendall Reference Kendall2007).

Figure 3 How the schema Path gives spatial continuity to fragmented movement or multiple spatial events.

2.5. Frames and journeys

The space beyond the framework of the body may appear to be a priori to most people, but in fact this space must be traversed to be properly grasped. Infants actively explore the world and they experience space through actions requiring both time and effort. The movement of the body, the movement of objects, the movement of other people – all of these contribute to an understanding of space through spatial actions and behaviours. We develop basic mental frameworks for spatial perspective. The egocentric perspective (body-centred) and the allocentric perspective (external landmark-oriented) appear to arise quite spontaneously (Taylor and Tversky Reference Taylor and Tversky1996). We also learn that certain places and certain contexts are characterised by particular spatial behaviours and we construct mental reference frames that capture these associations (Tversky Reference Tversky2009). For example, we associate the concert hall with a reference frame as well as the forest. Our frame for the concert hall could be evoked by being at a concert, listening to a recording, or just imagining something being played at a concert. Electroacoustic listeners hold a frame for their physical location whether it is a concert hall or a living room, while at the same time they are activating other frames in order to understand what is heard. Denis Smalley (Reference Smalley2007) provides an extensive catalogue of reference frames of various kinds, frames that he associates with terms such as gestural space, microphone space, prospective space, and so forth. Beside such general frames, we often have prototype frames for familiar or particularly meaningful spaces. We may envision a prototypical concert hall or a prototypical forest. Then, too, we may have particularly rich frames associated with specific places, specific concert halls or specific forests, whether they are real or imagined. Such places often are associated with signposts and landmarks that serve as anchor points in our spatial orientation, whether it is the fountain outside Avery Fisher Hall or the home tree in Avatar. The electroacoustic listener not only makes sense of immediate spatial events but also experiences meaning when connecting these events to frames which situate the events within a complex network of associations. How impoverished would it be to listen to Luc Ferrari’s Presque rien n o 2 or Hildegard Westerkamp’s Kit’s Beach Soundwalk without a sense of location?

Of course, art does not carry the constraints of real world situations. A journey does not need to lead to realistic consequences and may even be purely metaphorical (Kendall Reference Kendall2010), but navigation does imply time and effort. In simple cases, the listener navigates space within a single spatial framework and follows a path of changing location within that framework. The journey may rush or linger. The listener may anticipate upcoming events and signposts, but the time at which they arrive is probably uncertain. When listening to Barry Truax’s Island, we imagine that we are exploring a Pacific island, but we have no notion of when the next landmark will arrive. In many other pieces, navigation is best described as a series of connections. Separate places and their spatial frameworks are abridged and connected together. Such combinations of spaces could be likened to a cognitive collage (Tversky Reference Tversky1993).

2.6. The reference frame of multichannel reproduction

When listening specifically to electroacoustic music, we bring with us reference frames and associations that situate the meanings we construct. Just being in a concert hall situates meaning in a way that is different from being in an art gallery or a shopping mall. In multichannel reproduction, we activate reference frames that also shape our expectations and our sense of plausibility. This is a context in which we know that loudspeakers represent the most plausible locations of sound events, even though these locations may be only loosely related to spatial imagery and totally unrelated to conceptual sound events. We know that some events may conform to the spatial behaviours of the physical world, but most events will not. While striving to understand the ongoing experience, the listener will probably group and interpret events within one or more spatial frames familiar from the real world or from electroacoustic art. There are, of course, different traditions for how the spatialisation is handled and listeners also may adjust their frame depending on the extent that they recognise the idiomatics of such traditions. Treating loudspeakers and the room as being the composition’s environment produces one kind of result. Treating the loudspeakers and room as a vehicle for creating illusory images and spaces produces another. In either case, what the listener experiences depends on these mental reference frames as well as the acoustic and perceptual details of the multichannel reproduction.

3. Idiosyncrasies of multichannel reproduction

3.1. The view from the sweet spot

The listener’s ideal physical location is the sweet spot. In stereo reproduction, the sweet spot is equidistant from the two loudspeakers and set back to form an angle of 60°. From the vantage point of the sweet spot, the listener is not only able to perceive spatial imagery at the loudspeaker locations, but also phantom images in between. In multi-loudspeaker reproduction, the sweet spot is roughly equidistant from all loudspeakers. It has been long known that the behaviour that we associate with phantom images in front of the listener in stereo reproduction does not continue around to the sides. Phantom images are extremely fragile on the sides. During the era of quadrophonic sound, Ratliff (Reference Ratliff1974) studied the perception of phantom images to the front, side and back of a listener. His data for the front pair of loudspeakers conformed to expectations and the rear pair produced similar results, but:

The side quadrants exhibit a great degree of uncertainty,

…

It would appear that the ‘stereophonic-image’ phenomenon breaks down at the side of the head … Also there is preferential reception of the front loudspeaker,

…

There is a distinct threshold interchannel level-difference in this region, about which small variations cause the image to jump towards the front or back. (Ratliff Reference Ratliff1974: 12)

Even from the sweet spot, it is difficult to achieve a compact phantom image to the side. This phenomenon of spatial images shifting and spreading between loudspeakers on the side we will call image dispersion. In one sense it represents a localisation error. (Tom Holman describes it as a problem to avoid in 5.1 systems: Holman Reference Holman2008: 182–3). In another sense, it is one of the idiosyncrasies of multichannel audio that can be exploited for artistic purposes.

If quad loudspeakers with 90° of separation create these issues, then the obvious question is how close do the loudspeakers need to be to avoid this? Ratliff’s study was followed by Theile and Plenge (Reference Theile and Plenge1977) who investigated phantom images with loudspeakers 60° apart and at different angles in relationship to the listener. In respect to image dispersion, their results confirm Ratliff’s. One consequence of Theile and Plenge’s results is their recommendation to avoid relying on phantom images to the side and instead to position loudspeakers to the left and right of the listener.

In a study of localisation with an eight-channel loudspeaker system, Simon, Mason and Rumsey (Reference Simon, Mason and Rumsey2009) determined that the direction of phantom images produced by amplitude panning varied for every pair of loudspeakers. Their eight-channel system was a familiar octophonic arrangement with a vertex to the front. This study demonstrates that, even in the case of listening from the sweet spot, simple panning does not produce the same result in all directions. Important too are the differences observed in the certainty of the phantom image’s location which indicate that image dispersion may be reduced but is not eliminated by additional loudspeakers.

3.2. The view from outside the sweet spot

Outside of the sweet spot, every listener is closer to one loudspeaker than another, and the precedence effect (Wallach, Newman and Rosenzweig Reference Wallach, Newman and Rosenzweig1949; Haas Reference Haas1951; Blauert Reference Blauert1971) has a crucial impact on the listener’s spatial imagery. Precedence is often described as the auditory system’s mechanism for clarifying directional hearing in reverberant environments. When encountering a combination of direct sound and indirect sound, the auditory system effectively gives precedence to the direct sound, the first arriving sound. The perceptual consequence is that the listener is better able to localise the sound source despite the presence of sound reflections. But precedence is the same whether the delayed sound comes from an environmental reflection or a distant loudspeaker. Consider the simple situation in which there is a listener and two loudspeakers. Sound emanating from either loudspeaker will arrive at the listener’s ears with interaural time and intensity differences, part of the directional cues to the loudspeakers’ locations. When identical signals emanate from the two loudspeakers, the acoustic signals reaching the listener will differ in arrival time, intensity and direction. The precedence effect varies depending on these three factors and the source’s characteristics, but the arrival–time difference (ATD) is the most critical for our discussion. Because the difference in distance between the two loudspeakers and listener is greater than the distance between the ears, ATDs are of a higher order of magnitude than interaural time differences, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4 Illustration of arrival-time difference (ATD) at the ears for two loudspeakers at different distances.

Precedence is a multifaceted phenomenon and an excellent contemporary review of the precedence effect is offered by Litovsky, Colburn, Yost and Guzman (Reference Litovsky, Colburn, Yost and Guzman1999). One facet of precedence has to do with the perceived direction of the sound event. Consider the case in which our two loudspeakers are located to the front-left and front-right of the listener. When there is no ATD between the two loudspeakers, listeners typically perceived a single phantom image located between the loudspeakers. When gradually moving the ATD from 0 to 1ms, the apparent location of the phantom image will shift toward the loudspeaker that is leading in time. This is the zone of summing localisation, in which the contributions of both loudspeakers are integrated. From 1ms to at least 5ms there is a region of fusion in which a single sound event is perceived at the location of the leading loudspeaker while the lagging loudspeaker’s contribution is largely suppressed. This is also the region of localisation dominance in which the leading sound dominates the perceived direction. Depending on the source material, at some point after 5ms there is a transition region in which the listener begins to hear sound events at each of the loudspeakers. This is called the echo threshold, the point at which precedence is said to be released. For transient material such as clicks, the echo threshold begins around 5ms. For sonic material with more continuous content, the echo threshold may range from 20 up to 50ms.

As shown in Table 1, ADTs in the range affected by precedence occur when loudspeakers are offset by relatively small distances. Consider the common arrangement of eight loudspeakers in a circle shown in figure 5. At the sweet spot, sound from all loudspeakers arrives at the same time and at the same relative intensity regardless of the diameter of the circle. But the size of the circle makes a huge difference for listeners outside of the sweet spot. Table 2 illustrates the ADT and intensity ratio of loudspeaker pairs B–C and H–B for the listener halfway between the sweet spot and loudspeaker C. When comparing typical small and large circles (diameters of 4m and 12m respectively), the amplitude ratios between pairs of loudspeakers are the same, but the ADTs change in proportion to the relative size of the circles. This is a clear demonstration of why precedence can dramatically change a composition’s spatial imagery when the reproduction system is scaled up from a small room to a large room.

Table 1 Offset in the distance of two loudspeakers for arrival-time differences (ATD) in the relevant range for precedence.

Figure 5 Familiar arrangement of eight loudspeakers in a circle. Two listener positions are represented, one in the central sweet spot and one halfway between the sweet spot and loudspeaker C.

Table 2 For the loudspeaker arrangement shown in figure 5, the intensity ratios and the arrival-time differences (ATDs) for a listener halfway between the sweet spot and loudspeaker C and for two different diameters of the circle.

Martin, Woszczyk, Corey and Quesnel (1999) studied phantom imagery in a five-channel surround sound system with loudspeakers at 0°, +/− 30° and +/− 120°. What makes this study interesting for us is that it investigated both interchannel amplitude and interchannel time differences. The interchannel time differences produce ATDs at the listener’s position akin to those produced by having loudspeakers at different distances. The study provides an insight into image dispersion in the context of precedence. When the 30° loudspeaker leads, its location dominates the listener’s judgement of direction until the ADT is around 0.6ms. At that point, the localisation spread increases dramatically and is not markedly reduced even when the rear loudspeaker has a 2ms lead. Importantly, the authors confirm that ‘the integrity of the images as appearing from a single location is seriously compromised, with the high and low frequencies appearing to originate from different directions’ (1999: 7–8). (See Ootomo, Tanno, Saji, Huang and Hatano Reference Ootomo, Tanno, Saji, Huang and Hatano2007 for a related study with trade-offs between ATDs and intensity ratios.)

Knowledge of image dispersion and precedence enables us to explain a practice that occurs regularly in live sound diffusion of electroacoustic music. Consider the situation in which the person operating the faders positions a stereo source signal simultaneously in a front pair and a rear pair of loudspeakers. From the vantage point of the sweet spot, the operator will experience image dispersion that spreads the sound images from the front to the back on both sides. Every other listener is in a different location with differing distances from the loudspeakers. But since image dispersion occurs over a wide range of ATDs, most listeners will perceive the effect even though the imagery probably varies with each location. Adjusting the relative balance of the front and rear channels changes imagery across the listening space and also affects the listener’s impression of being enveloped by the sound (Adair, Alcorn and Corrigan Reference Adair, Alcorn and Corrigan2008). The image dispersion effect is strongest for broadband signals and source signals made up of a mixture of events (as happens with live diffusion of stereo tracks). Figure 6 represents the way in which spatial images spread in relation to a range of ATDs. The figure is extrapolated from Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Woszczyk, Corey and Quesnel1999) and is simply a different way of conceptualising their results.

Figure 6 The relationship of image dispersion to ATDs in the case of a front and a rear loudspeaker both on the same side.

3.3. From image width to envelopment

There is a flip side to the influence of the precedence effect on spatial imagery. Perrott, Strybel and Manligas (Reference Perrott, Strybel and Manligas1987) point out that there are important conditions under which the precedence effect does not occur: there is no fusion and no localisation dominance. As an example, they point out that when one noise signal is presented with another noise signal uncorrelated to the first, the listener perceives not one, but two identical sounding sources which are hardly affected by ATDs. How this phenomenon can be extended to arbitrary source signals is thoroughly discussed by Kendall (Reference Kendall1995, Reference Kendall2007). The prerequisite is that the individual versions of the source signal have micro-variations or other ongoing differences that cause them to be decorrelated while leaving the identity of the source unaffected. This can be accomplished either during synthesis or by post-processing. When such signals are routed to separate loudspeakers, they are spatially segregated.

The absence of precedence in this situation improves the scalability of spatial imagery between small rooms and large rooms. For decorrelated signals, imagery is determined by the directions and relative intensities of the individual loudspeakers without regard to ATDs. Referring again to Table 2, since the relative intensity ratios are constant when size of the reproduction system scales up, imagery created with uncorrelated signals scales up too. Then again, signal processing can control the degree of decorrelation among signals so as to create a spatial continuum between single, fused images and imagery spread among all active loudspeakers. And, as Rumsey (Reference Rumsey2002: 660) points out, ‘at what point does the attribute we call source width become another one called envelopment?’ The lack of a clear boundary encourages artistic exploration.

3.4. Pause to reflect

The above discussion of image dispersion and precedence illustrates the complexity of the relationship between the perceived spatial imagery, the acoustic source material, and the relative locations of loudspeakers and listeners. The notion that spatial perception is uniform as signals are uniformly panned around multiple loudspeakers (or that spatial perception is independent of the characteristics of the sound source) is far too simple. But it is well worth mentioning that signal processing can reshape the situation. For example, the sweet spot in multichannel reproduction is located where it is only in the absence of moving it. Etlinger (Reference Etlinger2009) demonstrated that the sweet spot could effectively be moved by adjusting the outputs of the loudspeakers to produce zero ATDs and unity intensity ratios at other locations within the audience space.

Image dispersion and signal decorrelation are two ways in which sound artists can create spatial images with extraordinary width. This also helps us to understand an important aspect of the practice of loudspeaker orchestras such as the Acousmonium (Gayou Reference Gayou2007), the Gmebaphone (Clozier Reference Clozier2001) or the BEAST (Harrison Reference Harrison1999). The distribution of subwoofer, mid-range and tweeter loudspeakers in space creates a canvas over which the spatial image of the sound event is spread.

3.5. Beyond the horizontal plane

While elevated loudspeakers are not an everyday experience, the early pioneers of electroacoustic music Pierre Schaeffer (Teruggi Reference Teruggi2007), Karlheinz Stockhausen (Toop Reference Toop1981) and Edgar Varèse (Treib Reference Treib1996), all used elevated loudspeakers. It must have seemed a natural thing to do! A characteristic of the many large-space multichannel systems emerging today is the use of loudspeakers at multiple levels of elevation. These include the ZKM Klangdom, BEAST and the Sonic Lab at the Sonic Arts Research Centre, Belfast. Experience with producing electroacoustic music in such a venue teaches some important lessons. For example, the higher the elevation of the loudspeakers, the less that azimuthal panning works similarly to the horizontal plane. Interaural relationships above the head are quite different! Vertical panning appears to work well only with broadband sources. In fact, for elevated loudspeakers sound images are frequently disassociated from the loudspeaker locations. This is especially true for ‘de-elevated’ loudspeakers such as those below the floor in the Sonic Lab. During an interview concerning live diffusion in this space, an electroacoustic composer was asked why he did not utilise the basement loudspeakers. His answer: ‘But it doesn’t work’ (Bass Reference Bass2010). Clearly ceiling and basement loudspeakers work in a way that is different from common expectations. As discussed before, elevation perception is confounded with the spectral characteristics of the source. In the Sonic Lab, only low-frequency, narrow-band sources and sources with sharp attack transients are localised below the floor. Then, too, sources are localised in the ceiling loudspeakers only when they have relatively high frequencies or when they have sharp attack transients. An insightful comment from the same electroacoustic composer about elevated loudspeakers: ‘I think my ears are not as sensitive to height fluctuations as they are to lateral fluctuation’ (Bass Reference Bass2010). As discussed before, the left–right axis is fundamental to spatial hearing and the least prone to error. This is probably why so many composers find it practical to organise their tracks in stereo pairs.

3.6. The influence of source characteristics

Spatial hearing is complex and multifaceted. One of its interesting facets is how onset characteristics affect the listener’s directional judgements. Sharp attack transients create a momentary burst of energy across the whole range of audible frequencies and provide the richest stimulation to the listener’s perceptual system. Listeners are generally very poor at localising sine waves, but they are very good at localising sine waves with transient attacks. In a study of precedence with loudspeakers and room reflections, Rakerd and Hartmann (Reference Rakerd and Hartmann1986) found that subjects were able to localise sine waves with short onsets in the range 0–100ms despite the presence of room reflections. They also found that room reflections dramatically degraded the localisation accuracy of continuous sounds without these sharp attacks. In general, the more transient the source, the shorter the delay before the release of precedence. Broadband signals generally have a shorter echo threshold than band-limited signals (Blauert and Col Reference Blauert and Col1992), and very narrow-band signals weaken localisation dominance (Braasch, Blauert and Djelani Reference Braasch, Blauert and Djelani2003).

The initial spatial impression triggered by an attack transient can have a decisive impact on the listener’s judgement of where a sound event is located. And first impressions tend to persist. Whatever the characteristics of the continuing acoustic signal, it appears that the listener’s initial judgement of the event location remains in effect until some countervailing cue triggers a change. In the case of slow continuous changes, the listener’s impression of the location can be stuck or can lag behind what acoustics would indicate is the instantaneous location (Hartmann and Rakerd Reference Hartmann and Rakerd1989; Etlinger Reference Etlinger2009). But the introduction of a new transient in an otherwise continuous event can trigger an update of the event’s perceived location, and sound events with ongoing transients tend to continually update the listener’s judgement. The rapid attacks of the high-frequency tone in the beginning section of Chowning’s Turenas create a vivid sense of a moving sound source despite the limitation of being reproduced only in quad. If sharp transients assist the listener in localising sound events, then slow onsets produce quite the opposite situation. In the absence of an attack transient, the listener’s localisation judgement depends on the relationship of the continuous acoustic signals arriving at the listener’s ears. Slow onsets greater than 50–100ms are generally sufficient to avoid the transient localisation effect, but onsets in the range of a few seconds will certainly avoid it (Rakerd and Hartmann Reference Rakerd and Hartmann1986). On the other hand, it is difficult to quantify the influence of slow onsets with broadband noise because the perceived source tends to break up into separate frequency bands in different locations. This effect also occurs with many acoustic sources that contain both transient and continuous components. Sometimes the transient component localises in one location (generally at the loudspeaker) while the continuous sound is elsewhere.

Depending on the spectral characteristics of the source, phantom images are often elevated above the height of the loudspeakers (Ratliff Reference Ratliff1974: 12), a fact well known to recording engineers. Similar illusory elevations can be created with ceiling and sub-floor loudspeakers. Possibly because localisation above the head and below the body is so imprecise, the localisation of signals from these loudspeakers is easily influenced by the source’s spectrum. In the Sonic Lab, it is sometimes difficult to know when a signal is originating from the ceiling or from below the floor! Only very low-frequency narrow-band signals localise below the floor and only very high narrow-band signals localise at the ceiling. Most typical musical sound events localise somewhere in between, and most of these spatial images appear closer to the listener than to the loudspeakers. This is especially true when ceiling and sub-floor loudspeakers are used together (Gregorio Reference Gregorio2009).

4. Conclusion

Electroacoustic music embraces a multiplicity of approaches to multichannel reproduction, and, whatever one thinks about the aesthetic issues, the technical schemes or the compositional methodologies, every approach ought to be informed by the realities of spatial perception and also acknowledge that listeners are making meaningful sense of spatial events. No viable approach to spatial audio can ignore how the listener perceives and thinks, nor can it limit its considerations simply to the physical acoustics of reproduction. We need to engage spatial audio in all of its intricacies. Any approach to spatial audio appropriate to our time ought to be based in knowledge of human perception and cognition.

There is a distinctive and intricate linkage between meaning and space. Spatial meaning emerges from the embodied aspect of spatial perception. It emerges in ways that are idiomatic to spatial thinking and spatial experience, and it emerges from the idiosyncratic characteristics of multichannel reproduction, the nature of the artistic medium itself. Through the combination of technical and artistic exploration, we will be able to search out those new and unique possibilities for meaning that are yet to be discovered through spatial audio.