1. Colourful French Instrumentation versus Equalised German Orchestration

In distinguishing between instrumentation and orchestration, Manuel Rosenthal recounts a short conversation with Maurice Ravel:

I had been studying with Ravel for some time and he kept repeating, ‘You still don't understand orchestration. This is only instrumentation.’ Then finally I brought him a score and he said, ‘Ah! Now that's orchestration.’

‘But what's the difference?’ I asked.

‘Instrumentation,’ he said, ‘is when you take the music you or someone else has written and you find the right kind of instruments – one part goes to the oboe, another to the violin, another to the cello. They go along very well and the sound is good but that's all. But orchestration is when you give a feeling of the two pedals at the piano: that means that you are building an atmosphere of sound around the music, around the written notes – that's orchestration.’ (Cited in Nichols Reference Nichols1987: 67–8)

While the terms ‘instrumentation’ and ‘orchestration’ are often conflated and treated as synonyms, each of these two time-tested terms maintains a certain distinction. This distinction is based in part on the number of instruments employed in the process. In the example he gives Rosenthal, Ravel suggests that instrumentation specifically concerns the use of individual instruments, whether alone or in combination, to realise individual musical parts. Orchestration, on the other hand, produces a more diffuse, ‘atmospheric’ envelope of sound: a two-pedalled piano creates a penumbra of resonance in the sonic space ‘around the written notes’. On the modern piano, depressing the sustaining pedal increases the resonance of the impacted strings and blurs the characteristic sound of the piano's individual pitches, allowing each string to resonate sympathetically with all the others and to some degree mixing the individual pitch colours into a cloudy, more homogeneous sonority. As a term that contains the word ‘instrument’, ‘instrumentation’ tends to define and emphasise the particular characteristics of individual instruments. ‘Orchestration’, in contrast, aims to create distinctive composite sonorities through instrumental combinations often found within an ‘orchestra’ or other large ensemble. In effect, Ravel views the piano as a pseudo-orchestra, a common analogy given the popular reciprocal transformation of piano scores and orchestral scores in the late nineteenth century.

Moreover, nineteenth-century French instrumentation regularly associated instrumental sounds with vivid sensations or images. According to Hector Berlioz's Reference Berlioz1844 Grand treatise on modern instrumentation and orchestration (notice he uses both terms), each of the B-flat clarinet's various registers offers ‘menacing’, ‘heroic’, ‘tender’ and ‘noble’ colours that are compositionally valuable in themselves (1844: 124–5). Other vivid anecdotal characterisations include the pastoral oboe, the comic bassoon, the lamenting English horn, the solemn trombone, the military drum and the Spanish castanets. At the same time, the final section of Berlioz's treatise, dedicated specifically to the orchestra as a whole, contains eleven recipes for massive orchestral sonorities: recipe no. 9 specifies the ‘joyful, brilliant mezzo-forte’ created by mixing ‘thirty pianos, six jeu de timbres, twelve pairs of antique cymbals, six triangles, and four Turkish crescents’ (1844: 331). Such recipes are characteristic examples of a nineteenth-century French orchestration that engulfs individual instrumental timbres within diffuse, mixed sonorities.

While Berlioz's treatise promotes the value of instrumental colour, Hugo Riemann's Reference Riemann1890 Catechism of Aesthetics insists that ‘certain instruments – the bassoon, for instance – possess a sound colour which absolutely repels and does not touch “sympathetically” but has a comic or ridiculous effect. … This ridiculous quality attaches especially to instruments whose tone we call “nasal” – besides the bassoon, principally to muted trumpets and, in a lesser degree, to the oboe’ (1890: 20). If the ‘ridiculous quality’ of a wind colour repels the listener, Riemann suggests that the listener is unable to properly assimilate (or ‘subjectivate’) the compositional design. While French instrumentation projected individual wind colours and French orchestration conjured up massive sonorities, nineteenth-century German orchestration sought to subordinate and thereby cleanse individual wind colours within a clear, efficient, monochromatic orchestration. The examples from Riemann's Reference Riemann1902 Catechism of Orchestration double and thereby neutralise an ‘objective’ wind colour in order to create a more ‘easily-subjectivated’, string-centred sonority:

[While] the wind instruments became more independent by having assigned to them melodic progressions differing from those of the strings and crossing their paths … a real individualization of the single wind instruments is not yet to be found, and a solo-like use of a single instrument for a considerable time is avoided …. We now find the use of covering of wind instruments by strings playing in unison with them, that is, of levelling the special tone colour. (1902 32–3)

While German orchestration to some extent separates wind colours from the string sonority, the determinate colour of a solo wind instrument is still ‘covered’ or ‘levelled’ by its unison combination with the less colourful timbre of string instruments. Riemann insists that German orchestration sets the parts of an equalised string sonority into relief without creating the vivid, objective solo colour characteristic of romantic French instrumentation. Thus, as illustrated in Figure 1, German orchestration mediates between the vivid individual colours of French instrumentation and the dense sonorities of French orchestration. While French instrumentation features extended oboe solos and French orchestration combines orchestral forces into diffuse, ‘atmospheric’ sonorities, German orchestration carefully deploys an individual yet doubled wind colour without spoiling the equalised, string-centred whole.

Figure 1 Mediating between instrumentation and orchestration.

2. Pierre Schaeffer's Instrumental and Orchestral Values

Just as nineteenth-century German orchestration discounted the oboe's ‘nasal’ sound quality and pastoral associations, twentieth-century German aesthetics of musical autonomy often portrayed the French use of sampled sound materials as a compositional caricature. Since they relied on microphone-recorded samples of the instrumental, vocal and natural sonic environment, Pierre Schaeffer's early Noise Studies (1948) were portrayed by German aestheticians as a trivial footnote to the Cologne studio's non-referential, pure electronic music that synthesised sound material from electronically generated sine waves. Karlheinz Stockhausen suggested that the ‘first criterion for the quality of an electronic composition’ is ‘the degree to which it is free from all instrumental or other auditive associations. Such associations divert the listener's comprehension from the self-evidence of the sound-world presented to him because he thinks of bells, organs, birds, or faucets’ (Reference Stockhausen1959: 62). Stockhausen's early work Elektronische Studien (1953) valorises sound materials that will properly realise the differentiated collection of twelve equally salient pitches. Since the natural hierarchy of acoustic overtones created by a traditional string or wind instrument emphasises certain pitches above the fundamental – the third, fifth and octave – Stockhausen chose a partial-free sine tone in search of the complete control of timbre. For the Cologne studio, the neutral sine tone avoided the problematic referential qualities of inflexible traditional instruments. Aesthetically speaking, the anecdotal nature of early French electroacoustic music has effectively been dominated by autonomous German electronic music. Finding unmediated referential samples too ‘noisy’ to integrate into a musical structure, Schaeffer coined the term ‘reduced listening’ to describe the phenomenological reduction of samples. Using anecdotal sounds as a starting point the research process, the goal of Schaeffer's musique concrète is to extract a more abstract musical object with the aid of reduced listening. When mimetic sonic signifiers are torn from their signified meanings in order to create more malleable materials, concrete music virtually melded with pure Elektronische Musik to create what Schaeffer later termed an ‘experimental music’. In neutralising mimetic references, this approach tends to blur the identity of concrete sounds in favour of ‘purer’ non-referential sounds. Ten years after creating his Noise Studies, Schaeffer withdrew the term musique concrète in favour of even more entendre-centred musical research that became the focus of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales.

2.1. Écoute musicienne: ‘losing oneself in the orchestral mass’

Instead of obeying our reflexes, let us place ourselves in a contemplative attitude; instead of choosing one source across a multitude of disparate perceptions, let us try hard – as a step toward reduced listening [l’écoute réduite] – to hear, if possible, all at once. A return to passiveness? Not at all. More an active écoute musicienne, as though we were listening to an orchestra and trying to take in all the sources at the same time. Weary of listening to music passively, or idiotically to the singing of the first violins, one decides to open one's ears, to catch orchestral activity in its entirety, as the conductor does in the highest degree. A reduction has already taken place: the goal of exterior objects, of causes, of sources, is not to follow the events each proposes for itself, but to appreciate their collaboration; how, while entering into an ensemble, they nevertheless still distinguish themselves. It is the very dialectic of the orchestra, the etymology of symphony, always a pluralistic unity. If the écoute [musicienne] we describe is not reduced at the level of sound objects, one can say that we seek it at the level of the orchestra or in the hubbub that we took for the field of experience. It constantly mobilises attention and also avoids it by its richness and its diversity. Even the best professionals thereby lose themselves in the orchestral mass. (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1966: 332; original emphasis)Footnote 1

This passage from Chapter 19 of Schaeffer's Traité des objets musicaux describes the ‘dialectic of the orchestra’ as an interaction between individual instrumental sounds and the pluralistic orchestral whole. Perceiving the latter involves a particular kind of listening that ‘aims at all the sources at the same time’, a ‘conductor's hearing’ that Schaeffer terms écoute musicienne. Active listeners, Schaeffer suggests, go beyond the perception of single instrumental sources and focus on the new sounds created by the entirety of the ‘orchestral mass’. While this aural perspective expands the field of listening beyond the melody in the ‘first violins’ to include other instrumental combinations, it also entails an aural and visual reduction of individual instrumental causes and sources. Espousing a more ‘contemplative attitude’ and moving toward ‘reduced listening’, écoute musicienne brackets away the individual instrumental details – the physical sources – captured by natural, habitual listening in favour of sounds whose sources are difficult to identify. The orchestra promotes écoute musicienne by combining and thereby neutralising the colourful material identities of individual instruments; the vivid aural and visual image of a violin is dissolved into the orchestra.

Écoute musicienne occupies one side of a Schaefferian musicale/musicienne pair that distinguishes a listening that perceives scales, registers and other traditional musical structures (musicale) from an approach that seeks new sound objects (musicienne). Both approaches differ from a ‘natural’ listening that aims to identify sound sources.Footnote 2 Michel Chion describes the musicale/musicienne distinction:

Generally, l’écoute or l'invention musicale refers to traditional experiences with structures and with established and assimilated valeurs that one tries to rediscover or to recreate; on the other hand, l’écoute or l'invention musicienne tries to find new interesting phenomena or to innovate in the facture of the sound objects. L'attitude musicale relies on traditional valeurs; l'attitude musicienne actively researches new valeurs. (1983: 41)

Values (valeurs) are important aspects of sound objects for both approaches. Écoute musicale attends to scales of pitch-centred values while écoute musicienne searches for new values with which to create new scales. Schaeffer suggests that a child blowing on blades of grass draws on both écoute musicienne and écoute musicale. First, in pursuit of new sound objects, the child explores many different grass-playing techniques and their resultant sounds: ‘one huskier, another more strident; some short, others interminable; some strident, the others rough’ (1966: 339). Second, the child treats the grass as a musical instrument ‘in which he spots a more high-pitched sound, another lower, a short, a long, etc.’ (1966: 339). Through the discrimination of écoute musicale, some sound objects will become values within a scale. Écoute musicale is also the tool of the violinist who strives to more accurately and fluently realise wider ranges of pitch and dynamics. While l'invention musicienne aims to enlarge the pool of musical sound objects by exploring noises, the violinist and l'invention musicale reject and/or refine sound objects, ensuring that a sonic novelty still fits within the traditional bounds of music.

What is musical listening? The sense this word has in our musical civilisation is this: refined, but frozen listening. We can compare it with the term ‘écoute musicienne’, which would correspond to the renewal of listening, to the questioning of the sound object, for its virtualities. One could say, and it would be better than a play on words, that traditional écoute musicale is listening to the sound of stereotypical musical objects, while écoute musicienne would be musically listening to new sound objects proposed for musical use. (1966: 353; original emphasis)

While the ‘renewal of listening’ created by écoute musicienne discovers new sound objects, it is musical criteria that ultimately determine whether any particular proposed sound object will properly function as a value within a particular musical composition.

2.2. Instrumental écouter, acousmatic ouïr and orchestral entendre

In its analytical search for new sound objects within the realm of noises, écoute musicienne works best within what Schaeffer terms an ‘acousmatic situation’. ‘Acousmatic’ denotes the visual separation of a sound from its source, a separation intended to minimise the objective referential status of the ‘acoustic’ source in order to elevate the sound as such. Between its ancient Pythagorean roots and this twentieth-century revival, acousmatic sound could also be considered a nineteenth-century phenomenon: Brahms's equalised, heavily doubled orchestration and Berlioz's massive orchestral forces aurally hide individual instrumental sources by doubling them or burying them within other sounds. While the relative source ambiguity created by the acousmatic situation is reminiscent of a diffuse, doubled orchestration's neutralisation of individual instrumental colours, Schaeffer's aesthetic does not subscribe to a post-compositional orchestration. For Schaeffer, orchestration is a post-compositional process that concretises abstract musical notation to create a musique abstraite with varied timbral realisations (e.g. Richard Wagner's and Gustav Mahler's various orchestrations of a Beethoven symphony). ‘Instead of notating musical ideas by solfège symbols and entrusting their concrete realisation to known musical instruments, [musique concrète] was a question of collecting the concrete sound, wherever it came from, and of abstracting the musical values which it potentially contained’ (1966: 23). Musique abstraite begins with abstract symbols and leads to an often conditional timbral realisation. In contrast, the process that leads to musique concrète begins with concrete sonic phenomena – whether instrumental sound or, more often, recorded natural noises – that are subsequently reduced into more neutral ‘sound objects’ suitable for compositional organisation. These two musiques position the abstract and the concrete at opposite ends of their respective processes: musique abstraite is the product of concretisation while musique concrète is the product of abstraction. Schaeffer's primary research is devoted to the latter.

In cultivating the process that derives the abstract from the concrete, Schaeffer devotes the Traité to discovering and classifying a multitude of sound objects and musical valeurs suitable for musical organisation. The researcher properly discovers compositionally useful, neutral sound objects through an acousmatic reduction involving what he terms ‘ouïr’, one of four listening modes enumerated in the Traité. Two modes capture objective information: mode 1, écouter, captures the objective referential index of a sound (e.g. the sound of an oncoming car or a violin) while mode 4, comprendre, understands an abstract musical syntax (e.g. pitch notation) obtained by traditional musical listening. In keeping with écoute musicienne, modes 2 and 3 are subjective modes that depend on the depth of the listener's internal investigation of a sound. In mode 2, ouïr, the listener avoids the objective information received in mode 1 in favour of the sound object itself. In mode 3, entendre, also termed ‘reduced listening’, the listener once again reduces the acousmatically reduced sound object in order to discover musical objects within the sound object. Perhaps better termed musical qualities or musical aspects, these musical objects are the essential stuff of Schaeffer's research. As illustrated in Figure 2, Schaeffer's numerical ordering of these listening modes (top row) creates processes that are central to his programme. An ordered move from left to right creates a concrete-to-abstract process (bottom row) as well as a circular objective–subjective–objective process (middle row).

Figure 2 Schaeffer's numerical ordering of listening modes.

Schaeffer's research programme is largely devoted to the journey from mode 1 to mode 3 – from écouter through ouïr to entendre, from objective to subjective, from concrete to abstract. Brian Kane (Reference Kane2006) describes the significance of two ‘interlocked’ phenomenological reductions in the context of Schaeffer's project. To find musical objects within an indexical sound, the sound must undergo both an ‘acousmatic reduction that helps diminish the priority of indexical and significative modes of hearing (écouter and comprendre) in order to bring forth the possibility of modes of hearing that remain closer to the manner in which sounds are ‘given’ in perception’ and ‘an eidetic reduction that further removes the residual signification which attaches to sounds, in order to focus on the manner in which perspectival adumbrations (whether given in perception or imagined in free variations) synthesise around an identity-providing essence’ (2006: 116–17). Ouïr enacts an acousmatic reduction in order to identify sound objects within an indexical sound, while entendre enacts another ‘eidetic’ reduction in order to qualify musical objects (aspects) within a sound object. Écoute musicienne relies on entendre in its search for new valeurs. Moreover, preserving identity and finding new qualities are significant for instrumentation and orchestration: unlike French orchestration's ‘organ-like’ sonorities, French instrumentation very often retains an individual instrument's vivid instrumental identity (e.g. Berlioz's ‘noble’ clarinet register, pastoral oboe, Spanish castanets) in order to project an image and/or a melodic gesture. Brahms's prototypically German orchestration tends to reduce or sublate instruments into equalised sound qualities through a process of sound mixture.

2.3. Reducing instrumental timbres into Schaefferian values

In the metaphysics of Western music, the ‘note’ is the prototypical musical object; notes traditionally function as Schaefferian ‘values’ (valeurs) suitable for producing scales and compositional structures. Values are united into scales by more permanent sonic characteristics that Schaeffer terms ‘characters’ (caractères). A traditional instrumental timbre such as that of an organ, violin or piano functions as a prototypical character that unifies a striated register of values. Thus unified, no particular value will stray or distract from the constant instrumental timbre. While the pitches of a single instrument often function as values within a scale, the varied instrumental timbres of several instruments are less adept at creating values. Schaeffer points to unsuccessful theoretical attempts to create Klangfarbenmelodie in which pitch is a character that grounds a register of timbral values. If a particular timbre becomes too permanent or characteristic, it disrupts the unified scale:

A bassoon, a piano, a kettledrum, a cello, a harp, etc., playing the same pitch are supposed to be creating a melody of timbres … . Here, as all the sounds have the same caractère of pitch, we need to look elsewhere for values. But when we try to do this we are not inevitably going to find a clear value in front of us; perhaps we will still recognise instruments and not a true Klangfarbenmelodie. These timbres are either too pronounced or too blurred for a clear value to result from them and for us to perceive them. (1966: 302)

For Schaeffer, timbre-as-value is a dubious concept due to the complexity of each individual timbre. Since they have difficulty integrating into a sonic continuum or scale, non-familial instrumental timbres rarely function effectively as values.

In addition to critiquing a Klangfarbenmelodie's lack of consistent character, the Traité evaluates an individual orchestral instrument's ability to create both a permanent character and varied values. Building on Figure 1, Figure 3 illustrates the instrumental and other sounds that Schaeffer aligns with the corresponding listening mode. Sector 1 concerns the generally acknowledged characteristic identity of an instrumental timbre, ‘the pastoral sound of an oboe’, for example. Chion describes the first Sector as ‘that which is made on the score. In effect one can consider that there is a general notion of the timbre of an instrument to which the score refers’ (Reference Chion1983: 69). The permanent character of an instrument is best captured by écouter, and the sounds in Sector 1 – the squeak and complex electronic sound – create permanent, colourful characters. Sector 2 concerns characteristic concrete instrumental sounds that are not indicated in the score. Schaeffer describes the second sector:

In Sector 2 there remains a contingent residue, the particular alone, ultimately the concrete alone, that the score, even by exhausting the contents of its symbols and of its implications, cannot determine. It is about the margin of freedom reserved for the performance. Situated in the austere conditions of the material only, we do not even recall the style of the virtuoso but only his technique. This technique produces characteristic notes, linked, of course, to his personal instrument; it is these particular sonorities which come to register themselves in Sector 2. (1966: 321)

Figure 3 Sounds that correspond with listening modes (Schaeffer 1966).

In keeping with ouïr and the acousmatic reduction, Sector 2 separates the instrumental sound from a particular source to create a sound object. To some extent virtuosic performance negates the referential identity of the instrument; an oboe playing rapidly in an extremely high register loses some of its characteristic oboe timbre. The solo violin and solo voice are adept at creating characteristic sound objects that mitigate somewhat the instrument's or voice's permanent timbral identities yet still preserve an objective character in keeping with ouïr. Sector 3 reduces the virtuosic sound object into non-normative (non-pitch-centred) values. Schaeffer describes the purpose of Sector 3:

Let us also acknowledge that, in [Sector 3], we posit (by thought) only that which is general, that which can be abstracted from the particularity of any execution. We shall know, for instance, that a string sound will have, to be sure, independently of the violin and the violinist (or of the viola, the cello), complementary values of sonority (resonance, harmonics, fluctuations, contours, etc.), that certain low sounds (piano, bassoon, contrabass) will allow a grain to be heard (entendre), or a value of thickness, which make them different from other parts of the register, and which are in practice independent of particular instruments and of particular performers. The composer knows it, and by orchestrating, he forsees it, employs it in advance. (1966: 321)

Rather than creating a scale of pitch values, Sector 3 searches for other aspects of instrumental sound that might function as values. Discovering these values entails the reduction created by entendre. Unlike the relatively simple sonorities and the regular pattern of vibrations created by a piano or violin, the complex irregular noises listed in Sector 3 – the gong, electronic sound and the squeak – have great potential to create new values if their sounds are properly analysed through entendre. In describing how sound values are ‘abstracted’ from particular instruments performed by specific performers, Schaeffer aptly describes how French orchestration uses mixed colours to bracket away particular instruments and performers in order to focus on sonority itself. In dissolving individual instrumental timbres in order to create novel orchestral combinations, French orchestration conceptualises individual instrumental sounds in terms of abstract aspects such as harmonics and grain.

3. Critiquing Electroacoustic and Orchestral Noise Reduction

3.1. Some post-Schaefferian critiques of electroacoustic noise reduction

The Traité des objets musicaux inspired various analytical approaches to sound, some more closely aligned with Schaeffer's method than others. While some attempted to create a music derived from Schaeffer's research, others found the products of reduced listening less productive. Denis Smalley, for example, describes the potential ‘perceptual distortions’ and compositional dangers of entendre:

Many composers regard reduced listening as an ultimate mode of perceptual contemplation. But it is as dangerous as it is useful for two reasons. Firstly, once one has discovered an aural interest in the more detailed spectromorphological features, it becomes very difficult to restore the extrinsic threads to their rightful place. Secondly, microscopic perceptual scanning tends to highlight less pertinent, low-level, intrinsic detail such that the composer-listener can easily focus too much on background at the expense of foreground. Therefore, while the focal changes permitted by repetition have the advantage of encouraging deeper exploration, they also cause perceptual distortions … . Retaining a realistic perceptual focus is, finally, a precarious balancing act. (1997: 110–11)

In contrast to the repetitive ‘microscopic perceptual scanning’ that ‘highlights less pertinent, low-level, intrinsic detail’, Smalley's ideal composer/listener restores some of écouter's natural inclination to assign a source to a sound. It is this restoration that makes newly discovered valeurs objective enough to become viable within a compositional syntax. If regarding entendre as ‘an ultimate mode of perceptual contemplation’ prevented Schaeffer's research from creating music, Smalley intends to put reduced listening into a more compositionally productive perspective.

Jean-Jacques Nattiez notes how later theorists of electroacoustic music reconsidered and reinvented the Schaefferian notion of a sound object in order to create a compositional process. For Nattiez, Schaeffer's notions of reduced listening and the sound object describe a particularly ‘neutral’ analysis, ‘too restrictive, especially by comparison with musical semiology’ which ‘after all, seeks to grasp the phenomenon associated with the musical fact in relation to the materiality of musical works’ (Reference Nattiez1989: 95). A ‘mere succession of objects’ emphasises the neutralised object at the expense of the process created by musical composition. While reduced listening functions esthesically in order to decide ‘how we go about making segmentations’ of musical organisation, Nattiez suggests that the composer's poietic and esthesic ethos must go beyond reduced listening. In his critique of Schaeffer, Chion (Reference Chion1988) notes how the suitable Schaefferian sound object – an object with a well-formed masse and facture – marginalises sonic gestures that extend beyond a limited time window:

In the classification that Schaeffer makes of different types of sounds, in effect those he chooses to be considered as ideal, because they are more perceptible by memory, more useful for listening, and more useful for musical construction, are delimited objects etched in time, those which he calls formed objects. These he enthrones in the centre of his typographical classification as potential ‘musical objects’, sound objects ‘suitable’ to the musical. But there are others: long sounds or at least not limited in length, the sound-turns, sound-spirals, sound-explorations, sound-respiration, all these sounds which Schaeffer chooses literally to marginalise. Named ‘woofs’, ‘big notes’, ‘accumulations’, etc., they will be shunted to the periphery of his typographical picture. And, of course, it is precisely in this discharge that concrete music is later going to scoop out its material. Especially at the end of the 60s, it will make a commonplace of endless sounds, sounds without outlines, sound processes, sounds which are more ‘à-travers-le-temps’ than ‘dans-le-temps’ and that do not introduce in the ear a memorisable line restricted in time. (1988: 56)

The suitable aspects of a ‘formed’ Schaefferian musical object correspond with the traditional characteristics of a musical note, a neutral object ripe for musical organisation due to its own inherent lack of complexity. In critiquing Schaeffer's strict classification of ideal musical objects, Chion promotes a less temporally delimited, more complex ‘sound without outlines’ whose own internal composition can create a musical process. Chion distinguishes the sound object from a sonic ‘being’, a ‘thing’ that gives rise to gesture and action: ‘While the sound object fills its place exactly in time, the thing is an entity which exists across time as an object, a being, an entity. Sound is the manifestation of states and activities, and sometimes the life of the thing; sound is the manifestation of the thing which is perceptible by us as though we were blind to it’ (1988: 57). Chion specifically notes how Pierre Henry's electroacoustic music creates an êtricule or ‘small being’, ‘something other than a sound object: its sound manifestation is unpredictable, intangible, often intermittent, but it evokes a united being, always the same from renewed aspects’ (1988: 58). The next section offers a critical examination of Schaeffer's aesthetic using a work created by Henry, one of Schaeffer's closest colleagues and collaborators. Capturing and critiquing the process of reduced listening, Henry's 1962 Variations pour une porte et un soupir creates an active musical discourse between mimetic referential beings and suitable musical objects.

3.2. Lamenting noise reduction: Pierre Henry's Variations pour une porte et un soupir

Henry's Variations would seem to be the sort of piece of which Schaeffer would disapprove. The opening two movements clearly present the mimetic sounds of a human sigh and a creaky wooden door. But Henry's Variations offers more than a montage of respiration and squeaky hinges; it musically manifests the virtual continuum between écouter's referential gestures and entendre's abstract sound objects. While the visceral sound of a creaking door initially interacts with more abstract sounds, later movements reduce the door to a neutral rhythmic pulse. Henry's musical variations enact the reduction process, making écoute musicienne a music-compositional phenomenon. As anecdotal sounds are phenomenologically reduced into sound objects and musical objects, Henry evokes the historic disappearance of anecdotal sounds in favour of more abstract musique concrète.

The following analysis employs spectrograms as visual listening guides to a composition featuring source-uncertain gestures as well as mimetic gestures of a closing door and sighing. Referential gestures are reduced through ouïr and entendre throughout the course of the work. While ouïr retains some of the sound object's causal identity, entendre transforms the sound object into a suitable quality, a valeur, a specifically musical object. A musical object with a suitable masse and facture – a sound akin to the traditional concept of a ‘note’ – will clearly appear as a defined rectangle on a spectrogram. The more discrete and defined the visual rectangle on the spectrogram, the more suitable the musical object. Conversely, cloudier, undefined shapes correspond to more complex, colourful timbral gestures. Since it is most sensitive to musical objects, the spectrogram is least adept at visually capturing and differentiating what écouter most easily hears. A series of complex referential sounds would overwhelm the spectrogram's visual field with amorphous clouds. The spectrogram visually identifies and validates suitable Schaefferian musical objects that feature discrete frequencies (masse) and durations (facture). Visually emphasising suitable frequencies and durations, the spectrogram reobjectivates phenomenologically reduced phenomena. Perhaps somewhat counterintuitively, reduced musical objects produce more defined spectrographic rectangles that manifest the determinate masse and facture of a bona fide musical object. Mimetic gestures captured by écouter generally create more amorphous horizontal and vertical clouds while the more abstract gestures of entendre create more clearly defined dots and rectangles. This visual distinction will aid in demonstrating how Henry's Variations realises the reflexive transformations between indexical sounds created by a referential thing – Chion's sonic ‘being’ – and phenomenologically reduced sound objects.

Before introducing the indexical sound of the door, movement 1, ‘Sleep’, begins with source-uncertainty. Two brief sound objects open the movement: one a percussive low frequency, the other a high-frequency glassy or metallic attack impulse. Although the lower sound might refer to contact between door and door frame, its relatively defined low frequency suggests a more abstract gesture. While these impulses seem suitable enough to participate in a register of musical objects, no other frequencies appear to fill in the wide gaps between the objects and create a register of values. Instead, these rather well-defined pitches are joined by relatively amorphous sonic clouds indicating a more indexical gesture: a gradually descending (sighing) white noise. This amorphous third sound is even less suitable as a musical object than the two previous onsets, and, since the complex sigh does not undergo any significant phenomenological reduction during the movement, it, too, is unable to create a register of values. By the end of the movement, the low- and high-frequency attack-impulses and effluvial sigh, seemingly unaware of each other, fade away without enough reconciliation to create a register. Movement 1 introduces sound materials without sonic transformations, a static theme rather than active variations.

In contrast to the relatively neutral sound objects of ‘Sleep’, movement 2 – ‘Swaying’ – introduces a creaking wooden door. The spectrogram's lack of defined vertical shapes indicates energy throughout the spectrum and a complex masse – an unstriated, unfocused frequency that is unsuitable for external musical organisation. On the other hand, the horizontal definition – the distinct spaces between the vertical bars – indicates some degree of facture; each of the door gestures has a beginning, middle and end. The rather varied onset intervals of each door-creak initially indicate a realistic door-creaking, but later in the movement the door creaks much more evenly; repeated vertical shapes between 0′24″ and 0′35″ indicate evenly spaced onsets and durations uncharacteristic of realistic door-creaking. This moment marks the beginning of the door's reduction from a referential sound into a more abstract musical pulse. In subsequent movements the door gradually loses its referential character in favour of pitch, pulse and other musical objects. Visual images gradually become neutralised.

While the door began a reduction into pulse in ‘Swaying’, in movement 4 – ‘Awakening’ – the vivid personality of the door is momentarily reduced into a more suitable frequency for creating a register of values. Illustrated in a spectrogram of the left channel in Example 1 by relatively long horizontal lines between 0′20″ and 0′30″, the sample of the door is neutralised into a more focused frequency, a more suitable masse. This movement's relatively well-defined horizontal lines contrast the vertical clouds in a spectrogram of ‘Swaying’. ‘Awakening’ begins to detach the door-creaking from its previous colourful, referential identity, moving it toward a more remote sound object.

After sporadically crafting a suitable masse through sonic stretching in movements 4 and 6, movements 7 and 8, ‘Gestures’ and ‘Rhyme’, more consistently focus the facture of the sounds to create the most suitable sound objects and most remote gestures so far. Door-creaking reduces into ‘door-notes’ – melodic ‘major thirds’ between 0′55″ and 0′95″. While these pseudo-pitches are still somewhat approximate and undefined, they are comparable to many of the flexatone's more focused sounds. The left channel spectrogram of ‘Rhyme’ features still more defined shapes that indicate the brief, saxophone-like sound objects created by high-frequency door-squeaking. In creating neutralised pseudo-instrumental sound objects, the phenomenological reduction leaves little trace of a wooden door. Moreover, this simpler internal composition of each sound object facilitates more complex musical organisation that includes the noisier sigh sound. The various gestures of ‘Rhyme’ employ more variety in contour and duration than earlier movements, still leaving enough sonic space for the sigh's more diffuse gestures.

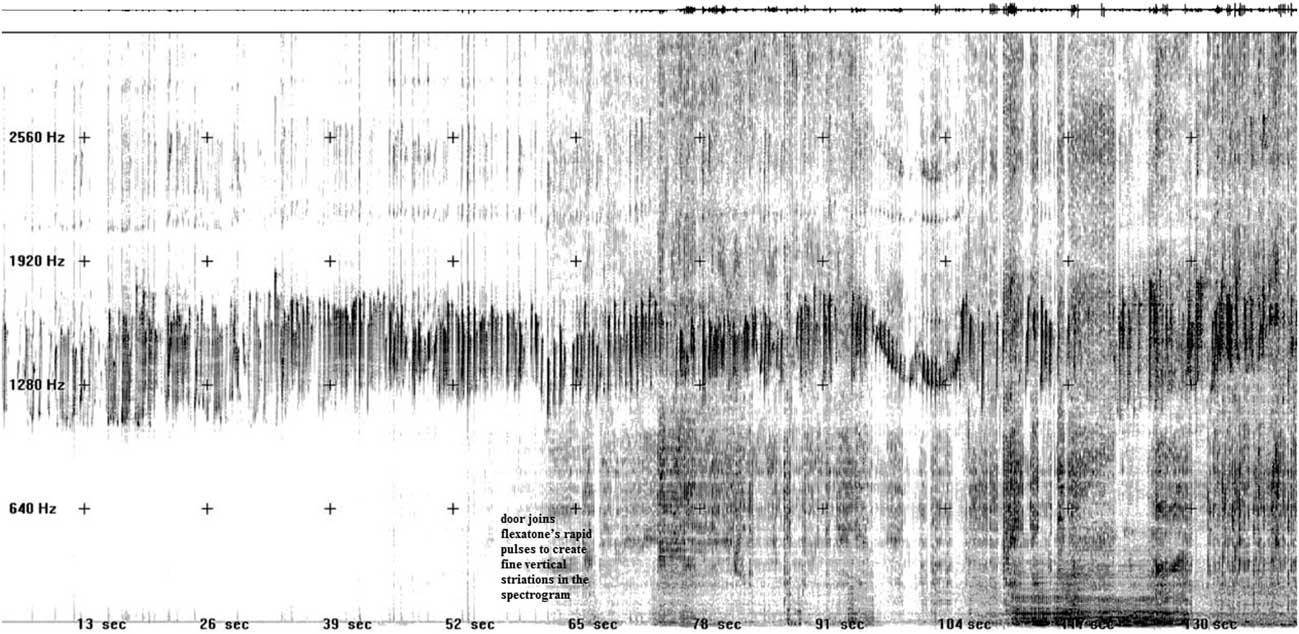

After movements 2–8 gradually reduce the door's gestures into musical objects by stretching door-creaking into pitch, movement 9, ‘Fever’, begins a process that shortens the duration of each door-note so severely as to dissolve pitch into extremely short impulses. After demonstrating its ability to create flexatone-like sound objects, the door anxiously assimilates the rapid rhythmic pulse created by the flexatone. As shown by the regularly spaced, close vertical lines throughout the spectrogram of the right channel in Example 2, the door joins the flexatone's pulse and, in the process, loses its focused masse, sacrificing pitch in order to create short bursts of sound that fill the entire vertical spectrum of the spectrograph. In effect, this process damages the door-note's masse and facture without substantially recovering any of the referential door noise. In movement 10 – ‘Yawning’ – one door presents a suitable masse and facture in the left channel while another door presents noise fragments in the right channel. The left-channel door sound is stretched into sustained, relatively defined lines at several moments throughout the movement while the right-channel door is unable to create any significant vertical definition. Rather, the right door creates dark vertical blocks that are striated into finely spaced vertical strands, each strand representing an extremely short, unsuitable sound fragment. These fragments are the only remnants of the door to be found in the final movement, ‘Death’. Figure 4 illustrates the door's gradual transformation from indexical timbre (left side of chart) to neutralised fragment (right side of chart).

Figure 4 The door's gradual transformation from indexical timbre to neutralised fragment.

Unlike a piano sonata or Baroque dance suite, the anecdotal door-caractère of Henry's Variations extends well beyond Schaeffer's circumscribed category of suitable, note-like musical objects. Schaeffer carefully separates Henry's Variations from his own project:

Let us say that [Henry's Variations] is about a study of the play of an instrument … Limited to a domain of objects defined by their common source, the experimenter, here the composer [Henry], explores the entire margin of possible expression of these objects, thanks to the instrument's variations of play. One cannot better show the existence of a sense in the dispositions of objects, even if one refuses them the title of musical objects. Experimental composition thus reveals unsuspected possibilities of listening … Such is not our purpose because, however strange it appears, it is the upper level of composition and not the solfège of suitable objects that we are in search of. (1966: 355; original emphasis)

For Schaeffer, Henry's instrumental ‘play’ produces a new batch of sound objects, but it does not create a new register of abstract musical values. Since the various sound objects created by the door are united by their relatively obvious physical source rather than shared essential characteristics, a door ‘slam’ and a door ‘creak’ cannot unite into a scale of musical objects. Schaeffer contrasts his experimental refinement of values to Henry's unrefined compositional use of anecdotal ‘monsters’:

In spite of the Dionysian drunkenness of the initial creation, I always felt more like an experimenter than a musician. I was very quickly motivated by a need for more and more investigation. I am a fan of knowledge. Pierre Henry, much more a musician than me, made our monsters shout without trying to clarify them. While I moved away from musical tradition with dread, measuring all that I had just destroyed, Pierre Henry was there, rejoicing, moving toward the future. (1977: 74)

Admitting that the search for musical objects depends on musical tradition – écoute musicale and composition musicale – Schaeffer falls back on his self-proclaimed status as a researcher rather than a composer. While Henry often employed anecdotal objects in his earlier works, he, like Schaeffer, later selected sound materials almost exclusively through ouïr or entendre. Variations pour une porte et un soupir was one of Henry's last works to feature referential samples.

3.3. Critiques of orchestral noise reduction

Prototypical German orchestration often performs acousmatic reductions of individual instrumental colours in order to build larger registers of musical objects; that is, orchestrators isolate the more neutral ‘chest voice’ ranges of instruments and combine these individual ranges together to create a large, homogeneous, equalised instrumental register that can effectively realise a pre-existent design. The slightly mistuned strings of both the seven-octave piano and the string orchestra are traditional tools for creating such chest-voice registers. When creating new tools for realising a textural design, the technological apparatus of orchestration strives toward more extensive yet unified instrumental ranges. Since acoustic instruments and the individual agents playing them are often unable to produce the necessary ranges of frequency and duration, orchestration attempts to transcend individual instrumental limitations. Expanding on Figure 1, Figure 5 aligns Schaeffer's listening modes with French instrumentation, German orchestration and French orchestration. Both French instrumentation and écouter focus and preserve the immediate source of the sound. Just as entendre reduces instrumental sources in search of new values, French orchestration dissolves individual instrumental timbres in order to create massive, diffuse orchestral sonorities. Evoking the complex balance of causal objectivity and source uncertainty captured by ouïr, the classic timbral doubling of German orchestration makes musical textures and gestures discernible but instrumental sources unclear. Of course, the nationalistic distinction softens if not disappears when the ‘New German’ orchestration of Wagner and Strauss both retains vivid individual instrumental colours and dissolves them into massive orchestral sonorities.

Figure 5 Comparing Schaeffer's listening modes, instrumentation and orchestration.

Example 1 Pierre Henry, Variations pour une porte et un soupir (1963), movement 4, ‘Awakening’, left channel (8192 FFT).

Example 2 Pierre Henry, Variations pour une porte et un soupir (1963), movement 9, ‘Fever’, right channel (8192 FFT).

Smalley's, Chion's and Henry's critiques of ouïr and entendre have an earlier precedent in instrumental music. In contrast to Riemann's and Brahms's German orchestration – which prefers doubled, equalised sonic material for its ability to unify a design without distracting from it – Berlioz's French instrumentation values the referential, anecdotal characteristics of individual instruments. Instead of reducing away instrumental identities, such instrumentation emphasises the individual instrumental source in painting extra-musical pictures and/or articulating melodic lines within a texture. Rather than reducing the trombone colour through orchestral saturation, for example, Berlioz demonstrates how a particular melody should be created for the heroic colour of the trombone section. This nineteenth-century appreciation for individual instrumental colour re-emerges in the twentieth century as a critique of massive postromantic orchestration created by large orchestral combinations. Egon Wellesz (Reference Wellesz1929) critiques Riemann's ‘levelling’ orchestration while promoting Arnold Schoenberg's virtuosic use of individual colour in Erwartung (1909), and Adorno (Reference Adorno1949) critiques the more acousmatic sonority in Schoenberg's later ‘orchestration-as-organ registration’ while praising the acoustic clarity of Alban Berg's Frühe Lieder instrumentation. Rather than trimming instrumental ranges and subsuming them within an orchestra, instrumentation gives individual instruments the durational and acoustical time and space to establish their referential identities as well as create extended musical gestures. An articulate colour becomes an effective ‘carrier’ of a melody as it both delineates a particular voice within a texture and connects the individual pitches within a melody by way of a consistent instrumental source. The vivid image of an agent – an instrument or a performer – can make a particular colour more salient. In contrast to an acousmatic orchestration, instrumentation shows an intimate concern for the anecdotal qualities of the instrument, qualities beyond the instrument's practical range and volume. The critical move away from Riemann's equalised orchestration to Wellesz's ‘new’ colourful instrumentation mirrors the move away from entendre-centred writing toward Chion's/Henry's colourful sonic ‘beings’. The aesthetic issues and cultural anxieties that underlie orchestration as historical practices remain in electroacoustic music.