1. INTRODUCTION

We have a heritage in radio art and sound art to be proud of. Radio art and sound art form an important chapter in our common cultural history … (Erik Mikael Karlsson)

Karlsson's declaration was made while he was the Ars Acustica Coordinator for the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) from 2005 to 2009 and demonstrates the EBU's acknowledgement of radio art as a significant art form within European culture. Established in 1989, the EBU Ars Acustica Group has been an international hub for the exchange of radio art information and works.

Interestingly, Karlsson's background is that of an electroacoustic music composer, who studied at EMS in Stockholm and has been awarded prestigious international prizes for his music. Nonetheless, Karlsson identifies the core output of the EBU Ars Acustica Group as ‘radio art and sound art’ and not as sonic art or electroacoustic music. While undoubtedly some of the works broadcast by the EBU Ars Acustica Group can be categorised as electroacoustic music or sonic art, the language used by Karlsson implies a closer association with the radio medium and the artistic exploration of sound for this medium. This article aims to historically investigate this association with the radio medium to create art, as viewed from various international perspectives, and argues that radio art is a specific art form with transdisciplinary properties. Moreover, while it is not within the scope of this article to enter into an in-depth discussion of what is and what is not radio art, our use here of the term radio art will henceforth include experimental approaches to radio dramas (or plays) and artistic work (including conceptual) created as a radio specific art form.

1.1. Further nomenclatural considerations emerging from Erik Mikael Karlsson's declaration and radio art culture

While I hesitate to delineate genre categories due to the contrasting and/or pluralistic international viewpoints that exist and are constantly evolving, for the purposes of this article I will however use the following brief explanations of the terms radiophonic, sonic art, sound art and electroacoustic music from which to nuance this review of radio art history (see Table 1).

Table 1 Brief glossary of terms for the purposes of this article

Notably, Karlsson also chose not to use the term radiophonic, although on the surface there seems to be an intrinsic connection with radio and the terms radiophonic and radio art. However, when investigating the word radiophonic, we in fact find a strong link with music practices. For example, Oxford Dictionaries define radiophonic as ‘relating to or denoting sound, especially music, produced electronically’ (Oxford Dictionaries n.d.). While Grove Music Online does not have a clear definition, it mentions the term under a number of related entries, including that for electroacoustic music, where radiophonic is described as a sub-category that ‘favours recognizable “real-world” sounds (including other music), a more radiophonic approach, which can border on the documentary, and is sometimes referred to as “anecdotal” music’ (Reference Emmerson and SmalleyEmmerson and Smalley n.d.). Although the term radiophonic was coined at BBC Radio in the 1950s and originally devised as an element of radio drama (as I will discuss in more detail later), it was also quickly adapted as a sonic element for TV evolving more towards electronic music practices, as best exemplified by the theme music for Doctor Who. Therefore, while media academic Tim Crook claims that radiophonic ‘can be simply understood as a preoccupation with the production of creative sound for radio programmes’ (Crook Reference Crook2012: 214) I would argue that this ‘preoccupation with the production of creative sound’ is not constrained to, nor most widely known for its application in radio; moreover, it is apparent that this preoccupation has strayed from the original intent, proposed in the 1950s, and has chiefly evolved around electronic music production. Nevertheless, radiophonic activities have included transdisciplinary aspects, offering music practice an avenue to explore new creative territory and hybrid working modalities.

The term sonic art is embedded in music practice in an even more pronounced way, originating when Trevor Wishart (who was not connected to radio production) declared that it was ‘merely a convenient fiction for those who cannot bear to see the use of the word “music” extended’ (Wishart Reference Wishart1985: 4). This is perhaps one of the reasons why Karlsson chose not to use the term sonic art to encapsulate the radio-specific activities of EBU Ars Acustica Group. Nonetheless, sonic art brought focus to the art of organising sound events in linear structures and has contributed to stylistic approaches for radio programmes, as they are also presented in a linear form. More recently Tony Gibbs has attempted to expand the definition of sonic art past its musical confines by suggesting that Simon Emmerson's quote that ‘music is a subset of sonic art and sonic art is a subset of soundscape’ (Emmerson quoted in Gibbs Reference Gibbs2007: 64) can imply that not all sonic art is music (Gibbs Reference Gibbs2007: 9), and now sonic art can also occupy activities ‘from fine art to performance, from film to interactive installations, from poetry to sculpture’ (Gibbs Reference Gibbs2007: 9). Gibbs’ expanded scope for sonic art is also shared by Leigh Landy, who simply refers to sonic art as an ‘art form in which the sound is its basic unit,’ (Landy Reference Landy2007: 10), indicating that it can now be seen as an overlapping term with sound art, media art, literature and more. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this article, I will constrain the use of the term sonic art to focusing on its original relationship with music practice.

What is puzzling about Karlsson's declaration is his inclusion of the term sound art, as Alan Licht and others have argued that ‘Sound art belongs in an exhibition situation rather than a performance situation’ (Licht Reference Licht2007: 14). However, as key exhibitions have also included experimental music the term has become somewhat more amorphous, as musicians with experimental bents have also started to label themselves as sound artists. Within radio culture, sound art is a term that is somewhat confused and has, to some level, been inaccurately adopted. Donald Richards’ 2003 PhD thesis, which researched the activities of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Radio's explorative radio programme The Listening Room, used the term sound art as an umbrella term, within which his standpoints could have added nuance (Richards Reference Richards2003: 43–5). I would argue, however, that Richards’ standpoint adulterates the contextualisation of this body of work by effectively shifting the terms of reference away from a specific radio media framework. I am not alone in my argument, as radio producer and composer Dr Michal Rataj, in his book Electroacoustic Music and Selected Concepts of Radio Art, has also found Richards’ repositioning of radio art under sound art practices controversial (Rataj Reference Rataj2010: 47–9). Moreover, the Kunstradio manifesto ‘Toward a Definition of Radio Art’ states that ‘Sound art and music are not radio art just because they are broadcast on the radio’ ( Kunstradio n.d. ). In considering the Kunstradio statement, I suggest that Karlsson's inclusion of the term sound art implies that there is a further level of embedding in radio art culture required to make the term sound art appropriate for the radio art context. Additionally, bearing in mind Max Neuhaus’ statement that ‘Much of what has been called “Sound Art” has not much to do with either sound or art’ (Neuhaus quoted in Licht Reference Licht2007: 10), for the purposes of this article – and to save further debate – I will constrain the term sound art to focus on its relationship with exhibition and installation, primarily in art gallery spaces.

While it is generally perceived that electroacoustic music emerged out of Western art music practices of the twentieth century, it has simply been defined as ‘Music in which electronic technology, now primarily computer-based, is used to access, generate, explore and configure sound materials, and in which loudspeakers are the prime medium of transmission’ (Reference Emmerson and SmalleyEmmerson and Smalley n.d.). The distinction I would like to highlight, for the purposes of this article, is that ‘Electro-acoustic music is dependent on loudspeakers as the medium of transmission’ (Reference Emmerson and SmalleyEmmerson and Smalley n.d.) and this ‘transmission’ usually means the diffusion or projection of the work in concert presentations and not the transmission of the works on radio. As Simon Emmerson and Denis Smalley point out, it is ‘the types and qualities of loudspeakers, their ability to project sound and their placement relative to the listener [that] are important factors in the reception’ (Reference Emmerson and SmalleyEmmerson and Smalley n.d.). So in that sense, the loudspeaker is seen as a transparent transducer, relaying the composer's work to the audience or analogous to aspects of a musical instrument placed in the concert environment, performing the composer's work. This control of the listening environment is in vast contrast to radio art culture where, as the Kunstradio manifesto ‘Toward a Definition of Radio Art’ points out, ‘The radio of every listener determines the sound quality of a radio work … . [and] Each listener hears their own final version of a work for radio combined with the ambient sound of their own space’ (Kunstradio n.d.). Therefore, for the purpose of this article I would like to make the distinction that electroacoustic music is a genre of music that is intrinsically fixed in music culture and practice.

2. Early Artistic Experiments With The Medium of Radio

A special technique of singing and playing for radio will develop, and sooner or later we will begin to find special instrumentations … new types of instruments and sound-producing devices may develop …

The artistic significance of radio can be glimpsed only in the development toward this special type of radio art, and by no means in a continuation of the prevailing concert system. In the radio art of the future … [the] personal interaction between podium and auditorium … would have to be consciously and intentionally eliminated in its entirety. At that point nothing would stand in the way of a purely artistic development of radio.

Kurt Weill (Reference Weill1993)Footnote 1

When discussing new developments in media, Marshall McLuhan has exclaimed that ‘We look at the present through a rear-view mirror’ (McLuhan, Fiore and Agel 1967: 75) as ‘We tend always to attach ourselves to the objects, to the flavor of the most recent past’ (McLuhan et al. Reference McLuhan, Fiore and Agel1967: 74). Many of the early examples of creative telephonic radio were also flavoured by ‘the most recent past’ and attempted to remediate existing forms by transmuting the book, the concert hall and the theatre into radio. However, there were some cases that emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, advocated by Kurt Weill and others, that strived to create a new media-specific art form.

On 15 January 1924, BBC Radio aired A Comedy of Danger by a young Welsh dramatist, Richard Hugh, who conceived a narrative for radio that was set in the dark of a mining accident (Crook Reference Crook1999: 6). This acute awareness for the media effectively placed the audience and the actors in the same ‘blind’ setting, which no longer utilised or invoked the spectacle of theatre as radio drama did.

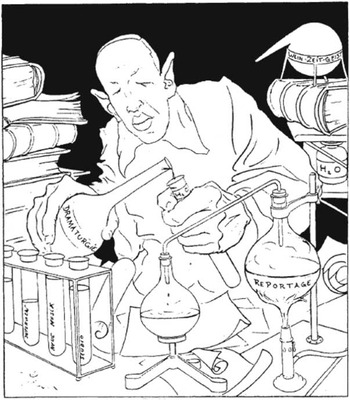

In Germany Hans Flesch was also exploring the potential of radio when he ‘put forward an artistic genre peculiar to the radio through the harmony of noises’ (Flesch, quoted in Gilfillan Reference Gilfillan2009: 70). Exploring radio's innate sonic and dramaturgic possibilities, Flesch created and broadcast Zauberei auf dem Sender (Radio Magic) on 24 October 1924 unannounced, in place of the scheduled Blue Danube Waltz. Daniel Gilfillan in his book Pieces Of Sound: German Experimental Radio, describes Zauberei auf dem Sender as ‘a cacophony of arguing voices, urgent whispers, and commanding shouts, which quickly devolved into a range of odd noises, ghostly sounds, out of synch instruments, and unsourced music’ (Gilfillan Reference Gilfillan2009: 70). A caricature of Hans Flesch published in 1931 (see Figure 1) gives us an insight into the excitement that surrounded Flesch's media specific experiments. Flesch is depicted as a mad scientist, with his rack of test tubes labelled ‘interview’, ‘new music’ and ‘studio’, adding a drop of dramaturgy to a test tube of ‘H2O’ while the ‘reportage’ is being distilled on the Bunsen burner into an unlabelled flask. Tomes and a container labelled ‘WEIN-ZEIT-GEIST’ (which translated into English means ‘WINE-TIME-SPIRIT’) also surround Dr Flesch. If the words ‘ZEIT-GEIST’ are joined together to form ‘zeitgeist’ (meaning the spirit of the times), then perhaps the artist is trying to tell us that Dr Flesch is intoxicated by the knowledge that is being infused in his laboratory.

Figure 1 ‘The Radio Play Mixer’ caricature of Hans Flesch, which appeared in Der Deutsche Rundfunk (issue 20, 1931)

Flesch also created a body of experimental sound-based works for broadcast with Hans Bodenstedt that were generated from site-specific location recordings called ‘sound portraits’ (Hörbilder), including ‘Die Straße’ and ‘Hamburger Hafen’. In a sense these works also responded to Luigi Russolo's 1913 desire to use urban sounds as material from which to form creative works (Russolo Reference Russolo1986). Bodenstedt states that with these ‘sound portraits … the whole world offers itself as studio’ (Cory Reference Cory1992) from which to create radio art. Later in 1928 Flesch commissioned Walter Ruttmann to create Wochenende, an audio montage made by utilising film sound technologies to collect audio material over one weekend in Berlin. Hans Richter later declared that Wochenende was ‘among the [most] outstanding experiments in sound ever made. There was no picture, just sound (which was broadcast)’ (Richter Reference Richter1949: 114). During this period Kurt Weill, also striving to create a media specific art form (Weill Reference Weill1993), formulated an idea for ‘absolute radio’ which was composed from the sounds of nature and noises with the addition of what he describes as ‘unheard sounds’ (Freire Reference Freire2003: 69).

Also during this early period for radio in 1933, Italian Futurists Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Pino Masnata devised the ‘La Radia’ manifesto, which called for the abolishment of ‘action unfolding on a fixed and constant stage … time … unity of action … [and] … dramatic character’ (Marinetti and Masnata Reference Marinetti and Masnata1933) in radio. Marinetti's radio work Dramma di Distanze, with its instructions to broadcast 11 seconds of sound from various parts of the world in series, was one such work that attempted to accomplish the aims of the manifesto. However, the ambitious mandate set by the manifesto, to create works with ‘Freedom from all point of contact with literary and artistic tradition’ (Marinetti and Masnata Reference Marinetti and Masnata1933), was perhaps unachievable, but nevertheless propelled radio art to seek its own treatment and voice.

3. After the Second War World

After the Second World War, Pierre Schaeffer developed musique concrète at the Club d'Essai de la Radiodiffusion–Television Française. While it is unclear if Schaeffer was influenced by, or indeed had knowledge of, preceding radio experimentation, he furthered the practice by using more complex editing and sonic manipulation techniques, initially achieved using phonographic recordings and, later, using tape recorders (Reference Emmerson and SmalleyEmmerson and Smalley n.d.). But unlike Flesch, Bodenstedt, Ruttmann and Marinetti's works mentioned above, Schaeffer's works, I would argue, were not developed solely as a radio specific art form, as they were designed for both broadcast and performance in the concert hall. This suggests a duality of intentions from Schaeffer in his development of musique concrète, and indicates that when Schaeffer's work is nuanced from the perspective of radio art, his work and approach exhibits amorphous and multidisciplinary qualities. Nevertheless, Deutschlandradio Kultur's, Klangkunst programme website states that Pierre Schaeffer ‘remains today one of the most important milestones of radio art’.

During the 1950s in England, Donald McWhinnie developed an aesthetic preference away from using realistic sound effects, in favour of more minimal but carefully selected abstracted sound effects to propel the radio drama's narrative. McWhinnie explains that ‘in radio, as in poetry, we attain definition by concentrated intuitive short cuts, not by mass of elaboration and detail’ (McWhinnie Reference McWhinnie1959: 51). McWhinnie's subtle approach re-examined how the sound elements of radio could function together artistically by adapting Schaeffer's increasingly sonically abstract musique concrète techniques for his radio dramas. An example of McWhinnie's approach can be heard in Samuel Beckett's All That Fall (which was broadcast on BBC Radio in 1957 and produced by McWhinnie) with the sound effect of the arrival of the ‘up-mail and down trains’ that occurs from 38′20′′ to 39′50′′ (Samuel Beckett Works for Radio, CD). But as some of the works were evolving into ‘more music than play [drama]’ (Cooper, quoted in Niebur Reference Niebur2010: 28), the BBC feared that this controversial musique concrète would not meet with the approval of a conservative British audience. To ease the debate over whether musique concrète was in fact music or not, the BBC chose to re-label this type of sonic material for radio as ‘radiophonic’ so as to contextualise it as a radio-media-specific element (Niebur Reference Niebur2010: 29). When referring to Frederick Bradnum's work Private Dreams and Public Nightmares [subtitled as A Radiophonic Poem], which was an exploration of these new radiophonic sounds, McWhinnie stated in 1957 that ‘We think it is worth broadcasting as a perfectly first attempt to find out whether we can convey a new kind of emotional and intellectual experience by means of what we call radiophonic effects’ (McWhinnie Reference McWhinnie1957: 27). Later in 1958 the BBC established the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

4. American Radio Art

While the majority of experimental works for radio in Europe were conducted in state-owned and -financed radio stations, in contrast, in USA, the American government declared that the airwaves would be chiefly used for commercial and military purposes (Gorman and McLean Reference Gorman and McLean2003: 45–50). This effectively focused the development of radio media exploration and experimentation into two polarised directions: commercial outcomes for mass public consumption that could generate advertising/sponsorship revenue (e.g. popular radio dramas), and art or avant-garde music practices. Orson Welles’ 1938 radio adaptation of War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells is arguably the most famous example from the first group, with its meta-referencing radio treatment of fictional news updates and sociological implications associated with the widespread panic it caused on the east coast of America. In a more avant-garde music approach, John Cage's Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939) utilised the radio station as an instrument by broadcasting phonographs (that he manipulated) to the adjacent theatre, as part of a performance at the Cornish School in Seattle (Dyson Reference Dyson1992: 379), while his indeterminate score for twelve radios and twelve performers, Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (1951) brought the radio apparatus to centre-stage in a work, which in the scope of this article could be considered radio art. However, like Pierre Schaeffer's works, with Cage there is also a duality of perspectives that can be viewed with the aforementioned works, which indicates amorphous and multidisciplinary qualities when nuanced from a radio art perspective. Both works intrinsically use radio media and technology, but they are also intended as a musical performance for the concert hall, complete with prescriptive scores.

In April 1949 KPFA-FM in Berkeley, California was set up as the first non-commercial self-funded radio station in the USA (Pacifica Radio Archives n.d.). In the following years more and more non-commercial stations were established which, while offering opportunities for artist engagement, lacked the substantial funding support of the stated-owned European stations. Also, as non-commercial USA stations were always at the mercy of their major donors and sponsors, it was highly problematic to establish large-scale and sustained programmes for the exploration and experimentation of the radio medium. Nevertheless, American art practitioners have created vibrant works for radio, including Max Neuhaus’ Public Supply I (1966), which was a live mix of ten talkback phone lines, broadcast on WBAI 99.5 FM (New York), and his work Drive In Music (1967), a multiple radio transmitter installation along the Lincoln Parkway in Buffalo, which broadcast different tones from the various transmitters on the same radio frequency (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2006: 154–6).

These examples indicate that the broad range of what can be considered radio art activities in the USA historically had a much wider amorphous, multidisciplinary scope, with less sustained focus in one area, than that of European counterparts.

5. Re-emergence of German Radio Art

In 1933 the National Programming Director for German Radio deemed the early experimental radio works of Hans Flesch and others ‘perversities’, heralding many years of constrained broadcasting in Germany. Re-emerging from this period of authoritarian regimes, economic collapse and artistic repression, in 1951 West Germany Radio (WDR), Cologne, established the Studio für Elektronische Musik (Studio for Electronic Music). But instead of re-engaging with the exploration of radio media, the studio's main focus was the creation of electronic musical works that chiefly explored the physics of sound and/or mathematical musical structures (Holmes Reference Holmes2002: 103).

Nevertheless, in 1961 Friedrich Knilli called for a return to innovative approaches to radio content with his paper ‘Das Hörspiel: Mittel und Möglichkeiten eines totalen Schallspiels’ (Knilli Reference Knilli1961) (The Radio Play: Means and Possibilities of a Total Sound Play), signalling a new focus of radio-specific artistic exploration in Germany. Knilli proposed that all sound elements within a radio play (text, music and sound effects) could be given equal weighting and that works need not rely on the semantics of language to dominate. Knilli's ideas were later adopted by radio producers in Germany and led to the creation of the neues Hörspiel (new sound play) (Huwiler Reference Huwiler2005). An early example of this style of work is Paul Pörtner's Schallspielstudie I (1964), which Mark Cory describes as ‘a deliberate attempt to take verbal material and non verbal sound effects as far as possible in the direction of pure sound’ (Cory Reference Cory1992: 354).

Influenced by Knilli, radio drama producer Klaus Schöning (who worked at WDR, Cologne) became an important spokesperson for neues Hörspiel and was critical to the development of a ‘language for acoustic art on the radio’ (Media Art Net n.d.). Schöning not only commissioned a large body of new works, but also helped to open up the aesthetic groundwork and documented the emerging genre, linking it historically and theoretically to earlier German experimental radio works (Cory Reference Cory1992). One of Schöning's theoretical notions for radio included the blurring of distinctions between the categories of neues Hörspiel and new music in a pluralistic sense (unlike Pierre Schaeffer's approach towards radio), which fascinated contemporary composer Mauricio Kagel. In 1970 Kagel devoted the Cologne Seminar for New Music (in association with the WDR radio drama department) to the topic of ‘Music as Hörspiel’. This was a timely seminar as the distinctions between the categories of neues Hörspiel and new music had previously been blurred to such an extent that Hörspiel works had been published as scores rather than text and composers had started to be recognised as authors. Contemporary critic and theorist Reinhard Döhl later exclaimed that during this period Kagel had achieved what Kurt Weill aimed to do in 1925, which was ‘to search through the entire acoustical landscape for sources and means – regardless of whether they be called music or sounds – to structure one's own art’ (Döhl, quoted in Cory Reference Cory1992: 365). As a result, Germany entered a sustained period of engagement with radio art, supported by large budgets from state-owned public radio stations and bolstered by key figures such as Schöning and Kagel.

6. Sample of Other International Developments

In 1958 Pierre Schaeffer set up the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) (Group for Musical Research) with the assistance of Luc Ferrari, amongst others. During the course of the 1960s Ferrari challenged the direction in which Schaeffer was taking musique concrète, which was increasingly sonically abstract and expressionistic, while expounding his theoretical phenomenological principles of organisation. Ferrari instead preferred his own notion of ‘electroacoustic nature photographs’ (Pauli Reference Pauli1971: 58), which used completely recognisable sounds as narrative elements within his work. An early work in this genre, which Ferrari termed anecdotal music (Emmerson Reference Emmerson1986: 35), was Hétérozygote (1963–64). By 1970 Ferrari developed anecdotal music in a more extreme audio documentary vein with his work entitled Presque rien no. 1 le lever du jour au bord de la mer, which was created by editing down a continuous four-hour recording of a Yugoslavian village, sourced from a fixed spatial perspective, into a 21-minute work that kept the chronology of audio events intact. Ferrari states, ‘It was badly received by my GRM colleagues, who said it wasn't music! (Laughs) I remember the session where I played it to them in the studio, and their faces turned to stone … I was quite happy, because I thought it wasn't bad at all’ (Ferrari quoted in Warburton Reference Warburton1998). The name ‘anecdotal music’ also suggests that Ferrari regarded it as a type of music, and perhaps this is why this type of work was later contextualised by Leigh Landy (Reference Landy2007: 109) and others as a style of music. This indicates that, while there was some initial uncertainty at the GRM as to whether or not Presque rien no. 1 was in fact music, in the end the GRM seems to have accepted the ‘music’ definition, as they favoured the creation and promotion of musical styles and not radio forms. Nevertheless, Ferrari's contribution to radio art is demonstrated by his later works, which received international acclaim by winning multiple awards, including the 1972 and 1988 Karl Sczuka Prize and the 1987 and 1991 Prix Italia award.

In 1964 child prodigy and classical pianist Glenn Gould suddenly withdrew from public performances to focus on creating radio documentaries for Canada's state-owned radio station CBC. Gould, like Friedrich Knilli, was dissatisfied with the standard radio production values of the 1950s dictating that, as Gould states, ‘all other activity has to grind to a halt or at any rate come down by fifteen decibels’ (Gould, quoted in Jessop Reference Jessop1998) as soon as someone starts to speak. Gould, exclaiming that ‘The average person can take in and respond to more information than we allow’ (quoted in Jessop Reference Jessop1998), created a number of small-scale, multi-focused radio works. In 1967 he developed his first long-form work featuring his ‘contrapuntal radio’ technique, entitled Idea of North.

Also during the late 1960s, management of the state-owned Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) was increasingly supportive of the development of innovative radio work, with the aim of achieving international recognition. One such example was the commissioning of the Australian composer Nigel Butterley, who, working closely with sound engineers, juxtaposed multiple recordings of a choir and orchestra recorded at various proximities in order to superimpose the various aural perspectives. To this mix Butterley added spoken dialogue and created In the Head the Fire. Later in 1966 the ABC's investment paid off when Butterley's work won the 1966 Prix Italia ahead of Berio's Laborintus II (ABC Classic FM n.d.). In a sense Butterley developed a style of radiophonic music production – similar to Hans Flesch's aims for radio media – that would not be transferrable to the concert hall (Flesch, quoted in Gilfillan Reference Gilfillan2009: 70).

Throughout the decades from the 1950s onwards, radio art has been supported at various global radio stations and organisations, including those listed below in Table 2.

Table 2 International radio art initiatives

7. Conceptual and Evolving Trans-Media Developments

During the 1990s – under the stewardship of Heidi Grundmann – Kunstradio (Austria) engaged conceptual artists including Robert Adrian, Gottfried Bechtold and Lawrence Weiner to explore aspects of radio art. Some of the results ensuing from this engagement opened the way for a telematic art approach to radio art, where artists explored the ‘electronic space’ of telecommunication networks. Grundmann explains, ‘Artists working in this realm, in which radio is just one point of reference, are not so much concerned with the recording and representation of sound or music as with delineation, by using lines and channels, of electronic/digital space itself’ (Grundmann Reference Grundmann1994: 132). This developed into the notion where the Kunstradio artists started ‘to consider the radio (broadcast) space as a public sculptural space in which music, sound and language are the material of sculptures’ (Grundmann Reference Grundmann1994: 137). Expounding these developments, Kunstradio engaged Robert Adrian to formulate the manifesto entitled ‘Toward a Definition of Radio Art’.

TOWARD A DEFINITION OF RADIO ART

1. Radio art is the use of radio as a medium for art.

2. Radio happens in the place it is heard and not in the production studio.

3. Sound quality is secondary to conceptual originality.

4. Radio is almost always heard combined with other sounds – domestic, traffic, tv, phone calls, playing children etc.

5. Radio art is not sound art – nor is it music. Radio art is radio.

6. Sound art and music are not radio art just because they are broadcast on the radio.

7. Radio space is all the places where radio is heard.

8. Radio art is composed of sound objects experienced in radio space.

9. The radio of every listener determines the sound quality of a radio work.

10. Each listener hears their own final version of a work for radio combined with the ambient sound of their own space.

11. The radio artist knows that there is no way to control the experience of a radio work.

12. Radio art is not a combination of radio and art. Radio art is radio by artists. (Kunstradio n.d.)

An example of Kunstradio's telematic art approach to radio art was the 1995 work entitled Horizontal Radio. For this work a collaborative non-synchronous network of over twenty radio stations worldwide was set up. Heidi Grundmann explains that ‘Participants at each node usually curate their own contribution and the specific on site and/or on air renderings they give to the data circulating in the network.’ (Grundmann Reference Grundmann2007: 209). In effect, Horizontal Radio deconstructed and replaced the usual ‘vertical’ syndicated network (with its hierarchical implications) with a ‘horizontal’, decentralised network, where each node was free to contribute to and use whatever they pleased and where no two nodes experienced the same collision and/or mix of sound elements for the resulting broadcast in each location. However, Horizontal Radio consisted not only of the resulting audio broadcasts (as these were mere components of the whole work) but conceptually encompassed the entire process and network.

There are many other examples of the telematic art approach to radio art used by Kunstradio, including Robert Adrian's Radiation, Bill Fontana's Landscape Soundings I and Richard Kriesche's ARTSAT. For ARTSAT, Kriesche tuned into a live radio feed from an astronaut on the MIR space station and used this signal to trigger ‘a synthesizer to play the Blue Danube waltz, [and] directed an industrial robot to weld a pattern onto a huge steel disc … [which] was also recorded on audio tape’ (Grundmann Reference Grundmann1994: 133). Afterwards, the audio recording was sent to ten composers who each created short compositions from the recordings. These compositions were subsequently broadcast on radio and the ‘huge steel disc’ was installed as a public monument. In this context again, the resulting broadcasts of the short compositions and public monument are not the work itself, but merely seen as documentation from parts of the work (which explored channels of electronic/digital space).

Moreover, Robert Adrian argues that with this type of telematic art approach to radio art we start to conceptualise ‘communication as content’, and he expounds that ‘Just the fact of turning the machines on and being present in the [electronic] space was the work. What happened with the work was inconsequential, and basically once the machines were off it was gone anyway … and these things referred into radio’ (Adrian, quoted in Gilfillan Reference Gilfillan2008: 209). Furthermore, Roy Ascott has argued that ‘meaning/content is no longer something which is created by artists, then distributed through the network and received by the recipient. Meaning is rather the result of an interaction between the observer/participant and the system, the content of which is in a state of flux, … until it is reconstituted at the interface as image, text or sound’ (Ascott Reference Ascott1990: 19). Unlike the networked music performances of The Hub, who conceived of their work as a form of music, Kunstradio's telematic art approach to radio art overlaps increasingly with media art and diverges more discernibly from the confines of music practice.

Notably, from a German perspective, academic and radio art producer Andreas Hagelüken has polemically argued that the Austrian conceptual approach to radio art undermines the whole of German Hörspiel history, as the Austrian approach no longer centres around the merits of the pre-produced sound works. Moreover, Hagelüken, reflecting on and analysing the Austrian approach, which he describes as ‘art on air … [and] live transmitted performance art’, logically concludes that the ‘Pre recorded pieces in that sense aren't radio art’ (personal communication, 5 October 2008).

With the Internet gaining widespread uptake during the 1990s, accelerated by the development of the World Wide Web and the Mosaic graphical web browser in 1993 (Reference AndreessenAndreessen n.d.), artists started to consider the consequences of an increasingly global and trans-media landscape within an evolving context of radio art. Atau Tanaka was one such artist to explore this new territory, which, as Tanaka states, ‘extends the traditions of experimental radio art to digital techniques and network infrastructures’ (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2004: iv) with his work entitled Prométhée Numérique – Frankenstien Netz. Subtitled a ‘Hörspiel for Radio and Internet’ (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2002), the work was commissioned by Südwestrundfunk (SWR) (Southwest German Radio) in 2002. Consisting of a participatory space where visitors to the project website could ‘contribute to the evolution of a life-like data creature’ (Weill Reference Weill1993: 26–7) and enhancing this mechanical performer with geographically separated networked human musicians situated in Karlsruhe (Germany), Montreal (Canada) and Ogaki (Japan), Tanaka momentarily brought his cybernetic radio art organism to life.

Also exploring the potential of the Internet to extend, reinterpret and re-invent radio art, Swedish state-owned Sveriges Radio invested in developing a dedicated experimental radio art web-channel simply called SR c. Under the leadership of Marie Wennersten from 2001 to 2008, SR c engaged 300 artists globally to experiment with creating content, to design innovative graphical user interfaces for their website (http://sverigesradio.se/src) and to create installations or performances in Stockholm and Uppsala. SR c in essence investigated a range of online interactive access points for the audience to engage with radio art that went far beyond the experience of streaming audio or the podcast, which in 2005 Apple was promoting as the ‘rebirth of radio’. Moreover, Wennersten, inspired by Marcel Duchamp, conceived of radio to include ‘anything made within the institution of radio’ (Wennersten Reference Wennersten2007: 85), not just the medium of radio. This conceptually extended the notion of what could be radio art in a Duchampian sense to include artworks and performances that were only related to radio via the connection that they were made within the institution of radio. This allowed for works to be developed that did not utilise the medium of radio to be considered radio art within this conceptual framework, and for works that do not use sound as their basic unit to be developed within this paradigm and conceptually still be labelled radio art.

7.1. Final thoughts

With the current ubiquitous uptake of wireless networked mobile devices and twenty-first-century radio that is now on air, networked ad hoc and online, Kurt Weill's 1926 claim that ‘The artistic significance of radio can be glimpsed only in the development toward this special type of radio art’ (Weill Reference Weill1993: 26–7), I would argue, still has relevance, with only the lack of support, direction and imagination impeding the development of a vital and vigorous radio art ecology evolving and flourishing worldwide in the future.

8. Conclusion

While there are clear overlapping fields of activity and blurring of categories (especially between new music and neues Hörspiel) there are also clear delineations between the two art practices. Besides the obvious artistic intention of the artist or composer for the work, or the culture and language used by the practitioners, it is also the impact of the radio media and evolving theoretical framework that influence the works that are developed. For example, both Kunstradio's ‘Toward A Definition Of Radio Art’ manifesto and the conceptual approach to radio art by Kunstradio and Sweden's SR c, can eventuate in works that fall outside of the subset of sonic art.

Furthermore, by surveying radio art practices historically, it becomes apparent that there are idiosyncratic international standpoints that influence the approach to the art practice.

Even though I have presented examples and frameworks that indicate that radio art is not inherently a subset of sonic art, radio station initiatives and radio art practices nevertheless have historically played a significant role in stimulating the development of electroacoustic music and new music. This nexus of practices can today still provide a fertile junction point to propel both composers and radio artists to explore new creative territory and hybrid working modalities. In an evolving trans-media landscape where radio is terrestrial, online and technologically transforming, it is more critical than ever that radio stations continue to support experimentation (with substantial commissioning budgets, allocated online space, development of radio art apps and scheduled airtime), universities integrate radio art more intensely into curriculum and research, and funding bodies support opportunities for the creation and development of, and research into, the practice.

Historically, radio art has offered artists and composers a significant platform from which to present their work to both national and international audiences while providing a vital access point for the wider public to engage with the practice. With advances in technologies, radio art potentially offers an ever-increasing range of engagement modalities and opportunities for artists and composers to distribute and present their works globally.