1. INTRODUCTION

It is without doubt that digital technologies are creating rapid, unprecedented change in the way we do things. Humanity has always lived with the impact of technology, but most would agree the pace of change on the everyday lives of people is accelerating. The distribution of music throughout history is a good example of this increased pace of technological change – starting by sharing from one performance to another by ear, then through to notations, the addition of wax cylinder recordings and then – in our lifetimes alone – LPs, tape, laser and mini disks, DAT, CDs and, most recently, streaming. We communicate through our watches, test driverless cars, adopt robotics and engage artificial intelligence as personal assistants. These propositions change the fundamental ways we relate to each other, which includes the way we make music together.

Yet despite this rapid technological adoption, and an evident ongoing love of and engagement with music, composers and performers have been relatively unenthusiastic about adopting digital tools, outside of those used in recording, distribution and the creation of electronic and popular music. Portable tablet computers and wireless technologies enable sound engineers to mix as they roam the auditorium, access instant decibel meter readings, run multiple wireless microphones and foldback over the internet. Yet the most acoustic musicians seem to want is to be able to tune their instruments, access a metronome and record on their mobile phone, or markup and turn ‘electronic’ score pages handsfree. Composers have MIDI playback sounding like a real symphony orchestra in the notation programs on their laptops, and despite a few exceptions, this software remains formulaic and aligned to classic fonts that support established styles of music. Despite some powerful examples describing music with spectrographic and illustrative designs, there has been little technological evolution of music notation for music reading.

2. REPRESENTING THE MATERIALS OF SOUND

There are alternative notations that seem to remain on the fringe of music practice. Focused primarily on the facilitation of improvisation, the wonderful graphic notations that exploded onto the music scene in the early twentieth century – almost a hundred years ago now – were never adopted into common practice. And despite a wide range of electronic instruments and processes, the development of notation for these has been very slow. Perhaps we are still coming to terms with a way to think about electronic sounds and understand the way they function. Christopher Cox’s article ‘Beyond Representation and Signification – Toward a Sonic Materialism’ argued for new tools to think about sound more broadly. Cox describes music notation as a static form of recording that privileges the eye over the ear – effectively making it all wrong for its intended task. Cox also makes the somewhat contentious claim that visual notations have had their role superseded by the existence of recording, a medium more able to capture and represent the flow and temporal qualities of sound (Cox Reference Cox2011: 148). But it is difficult for a recording to function as a score to be read by performers in realtime. Despite some interesting work undertaken by composers using audio scores to instruct performers, by composers such as Luke Nickel and others, recording remains descriptive, rather than instructive. Kathleen Coessens claims that recording added ‘a radically new trace, auditory rather than visual, to notation’ (Coessens Reference Coessens, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013b: 123), flagging it as a complement to, rather than a replacement of, the stable of materials engaged in the creation and propagation of music.

The pop artist Beck undertook an interesting project in 2012, substituting the release of a recorded album with a Song Reader (Hansen Reference Hansen2012) – a book featuring twenty pages of sheet music. This was in response to Beck being sent piano transcriptions and guitar chord charts of one of his earlier albums by a fan. The release can be seen as a provocation of commercial popular music where the recording is considered to be the definitive, fixed version of the work, that could never be accurately notated. Recordings contain information about performance not provided in the score, as has been demonstrated by the many researchers who compare multiple recordings of the same works performed by different artists, with the hope of better understanding the composer’s intentions. But they are also limited in their ability to enable recreation by others. Similarly, the idea that visual notation has all the information ever needed to play a piece exactly as the composer had in mind, or ‘fixed for performance’ (Dalhaus quoted in Lewis Reference Lewis1996: 96), is easy to refute. Beck’s Song Reader points to an open idea – that there are many ways a song can be made, beyond the recorded version, often enriched by high levels of post production. The Song Reader, as the name implies, offers a framework to collaborate in the music-making process.

But overall, the majority of Western music being made today no longer relies on common practice notation as a methodology for its creation. Commercial pop, most electronic music and folk traditions around the world do well without it. Tablature and simple melodic lines are occasionally drawn upon to provide song books designed to enable the performance of popular hits for those with basic music reading skills – but these are at best a skeletal guide to some very basic elements that make part of ‘the music’, and are unable to represent the detail of the electronic production that defines modern popular music. An effective and comprehensive notation system will maintain the core collaborative aspects of music-making, and reflect the qualities of the music of the day. The openness of graphic notations invites possibilities for a composition style that no longer holds emphasis on chord structures and melody, but instead focuses on the actual sound produced, rather than pitch organisation, as can be found in much electronic music. This attention to sound encourages a collaborative approach across different instruments, styles and forms that can be enabled by dynamic graphic notations.

3. OWNING COLLABORATION

Common practice notation in Western music has survived because it is seen as a type of truth for the faithful to follow, analyse, distribute and reproduce – and often for a fee. Publishers and licensing agents are still looking to profit from their stable of published scores, clinging to an outdated business model whilst trying to build their income, stifling the possibility of new models of distribution and falsely inflating the importance and ownership of ‘documents’. Scores are also still the first stop for musicological analysis, despite the plethora of recordings usually available. But at a most fundamental level, these scores facilitate some kind of reproduction of the musical idea, a step towards rendering the composer’s idea into sound, through generations of composers and musicians. The creation of a score can be a useful process for composers who wish to sketch ideas out again and again, providing the opportunity to refine. Many electronic composers undertake a similar process, but with multitracks in the studio, or through a process of sound treatment, each screen interface leaving a trace of process. Even spontaneous, generative electronic music such as live coding, (Magnusson Reference Magnusson2011: 22) can leave a trace for study into the systems and processes of its maker, where the computer is the mute and obedient performer unavailable for comment.

These methodologies create copyright challenges for our digitised, collaborative communities, since current copyright law does not support flexible authorship or distributions. Change is low here, though some countries are investigating possibilities. New Zealanders are reconsidering their copyright law from the ground up anew:

The Copyright Act was written in the pre-internet age, and does not address any of the complexities surrounding file sharing, format shifting, and other modern issues. (quoted in El Gamal Reference El Gamal2012: 89)

Historically, copyright law has been approached in pieces, adjusting segments of the law as technologies change and evolve. The Cato Institute’s copyright think tank member Rasmus Fleisher outlines how copyright has been stretched beyond its initial purpose, which was that of the protection of distinct ‘printed’ works, and has been twisted and turned as new media formats and distribution emerge (Fleisher Reference Fleisher2008). The singular medium of the internet has erased the need for different bodies to be responsible for different tasks; for example, to sell (as in record shops: now downloading) and broadcast (from radio stations: now streaming) are now handled by the singular medium of the internet. The entertainment industry is hanging on to the old business model, slowing innovation, removing civil liberties and outlawing useful and important technologies. But it is not just the way we distribute material that needs revisiting, but also the whole process of creation. If there is significant copyright reform, the possibilities for collaborations brought about by new scoring methods have an opportunity to be addressed, and the collaborative potential of animated notations will be unlocked.

This is more radical than it sounds. Software development provides something of a model, as one area that has dealt with high volume multiple co-authorship for some time, but art is an area still very much dominated by the ‘sole genius’ construct. Performers are coming to realise the value of their input as integral to the creation of a new work, and it is unlikely that the same number of composers today can claim the clear-cut sole authorship role as they have done in the past. The collaborative possibilities of digital technologies highlight the division of labour when it comes to making a work; how we credit and balance the idea, versus the aspects that contribute to the rendering of that idea – the score, any live electronic processing required, mechanisms of delivery and the performance. Performers and programmers now make a significant contribution to a more open form of music-making, where the skills of programmers and the musicianship of performers becomes an essential component of the work moving forward. In a range of new works, the performer is no longer the rank and file executant who transmits the creators’ vision – they enable it, and are part of its formation; their contribution could be thought of as what Jeremy Cox calls ‘triangulation tools’ (Cox Reference Cox, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013). Performers of new works no longer just ‘add what wasn’t notated’, they are more likely to be part of the creation of the work entirely. Different models for authorship and how it is ascribed are needed. Copyright needs not just revising, but serious revisioning.

4. TRUTH, FIDELITY AND POTENTIAL

The further back in history we go, the less likely we are to know everything about how much sonic material notation of the day was intending to signal. The idea of ‘score fidelity’ has many different parameters according to function, style, period and materials. Jeremy Cox’s examination into composer’s performances of their own works argues that the idea of a true and final version of a scored work may never exist, no matter how it is notated. Composers often revise their works during their lifetime, with many ‘favourite’ versions of performances proving an aesthetic choice that may have nothing to do with ‘accuracy’. Cox’s idea of ‘durable evidence’ (Cox Reference Cox, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013: 13) or Coessens ‘boundary object’ (Coessens Reference Coessens, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013a: 61) better describe what a score represents. Terms such as these reinforce the idea that within every piece of music there are multiple ‘truths’ at play before, during, and after the composition and performance. These include but are not limited to the original idea of the composer, their understanding of or desire for interpretation and the performers’ experience, ability and willingness to engage. Therefore, the process of creating and/or notating is always a personal one, suited to the composer’s intentions and familiarity with methods and tools. Descriptive, prescriptive, open, complex, text, interactive and action scores – it is important that our need for archiving and analysis not be confused with the drivers for creating music in the first place.

A scoring format that enables varying degree of openness and acknowledges the contributions of performers – electronic and acoustic – is desperately needed in contemporary practice. There is a persistent view amongst many performers and musicologists that graphic scores are always intended to be open, just a short step away from free improvisation. However, graphic scores can present a range of control levels, allowing composers to decide what elements they wish to determine, how much fidelity is required and what type of potential is desirable. Not all composers desire to offer instruction for every parameter of musical activity, and others will retain traditional notation for certain aspects of communication. Further, graphic notations can relate to recordings in a particular way. It is much less likely that a ‘definitive version’ of a graphically notated work could be created as the result of recording a performance. It would be more likely that multiple and sometimes drastically different versions be created.

5. WHAT DO ANIMATED NOTATIONS DO?

Digital technologies provide new ways to present graphic notations; offering possibilities such as animation, realtime creation as well as coordination on local and internet networks for example. The graphic score for ‘Snæfellsnes’ (2015) by Marta Tisenga, shown in its entirety at Figure 1, is an example of an open, hand-drawn score that probably represents something close to what most people would imagine when they think of a classic ‘graphic score’. The recording of the work by the Chicago Civic Orchestra is beautiful, and belies what many may predict a graphic score to ‘sound like’.Footnote 1 Imagine what putting this drawing into motion could achieve in terms of encapsulating or enhancing the process of performance – animation could be used to control and coordinate the rate of progress of performers through the page, colour could be added and changed over time, details could appear, disappear and evolve – this list is endless.

Figure 1. Marta Tisenga ‘Snæfellsnes’ (2015).

Animated graphic notation can be defined as ‘a predominately graphic music notation that engages the dynamic characteristics of screen media’ (Hope Reference Hope2017: 21). These scores provide the tools to increase the number and manipulation of control points, as there are additional parameters that can be added – or taken away. For example, a score could unfold in realtime, revealing aspects at a certain pace, and that pace could be established by the composer, and/or varied by the computer, or performer – randomly or planned. This pace could alter the presentation to the performer, the speed of reading, or the combinations of parts. Information can be changed or updated during the performance, further ‘unfixing’ the notation and providing different performance outcomes. Notation can appear and disappear randomly or in a controlled fashion. It can drive and respond to sound. It can contain or evolve sounds of its own. There are many possibilities.

Animating existing prescriptive and descriptive graphic scores is possible, and the process can result in the provision of additional tools for analysis. A digitally automated electronic reading of Karlhienz Stockhausen’s 1954 Electronic Studie No. 2 was undertaken by Georg Hajdu (Figure 2).Footnote 2 This score for this work can be thought of as descriptive, yet Hajdu makes it prescriptive, by facilitating a realtime reading of the work, moving beyond the score as an ‘illustration’ of work undertaken in the studio.

Figure 2. Georg Hajdu, electronic reading of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Electronic Studie No. 2 (1954) created in MaxMSP (2012).

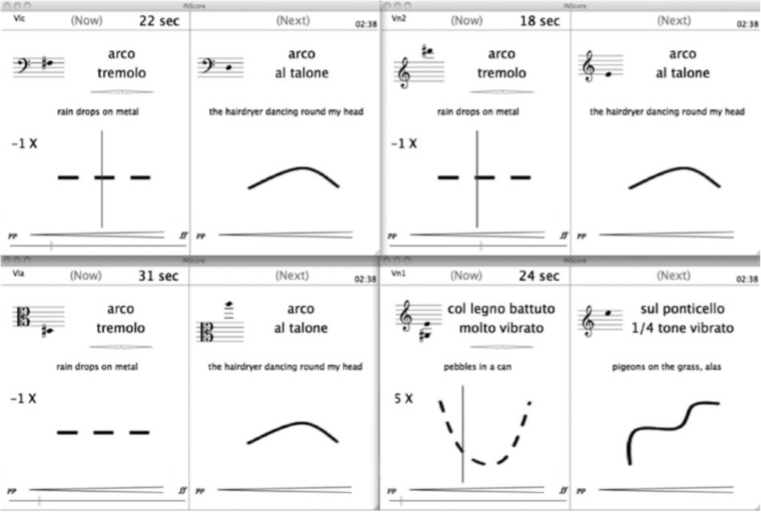

A range of software is available to create animated notations, and use animation to enrich analysis. Pierre Couprie’s ‘iAnalyse’ software provides animated analysis tools that enable slideshow, temporal and dynamic representations of audio to enhance the capacity to analyse recordings and electroacoustic music (Couprie Reference Couprie2004, Reference Couprie2019). Dominique Fober’s ‘INScore’ software provides an environment for the design of interactive, augmented music scores that include a range of graphic objects in addition to symbolic music notation, including video and sonic representations (Fober, Gouilloux, Orlarey and Letz Reference Fober, Gouilloux, Orlarey and Letz2015). The screen shot of an animated score for string quartet by Sandeep Bhagwati in Figure 3 shows how the composer used notation created in ‘INScore’ to describe not only what is happening now but also what will be happening next, in a relatively small space on the page. The vertical red line passes over the score image, from left to right, a starting pitch and a ‘concept’ for the sound are provided.

Figure 3. Sandeep Bhagwati, Monochrom, 2011, for string quartet (working version; note the playheads are red).

6. FROM SCORE TO PERFORMER TO SOUND

The dynamic nature of animated notation could redefine what can occur in the spaces between the score, the performer and the sound in music notation because it highlights the embodied potential of a work, to whatever degree a composer may choose. Animated notations provide a reliable and efficient mechanism for communicating composer intentions, whilst making space for stylistic interpretations and developments. Recordings can be embedded and triggered as part of these scores.

As Cecil Taylor remarked:

The whole question of freedom has been misunderstood. If a man plays for a certain amount of time – scales, licks, what have you – eventually a kind of order asserts itself. There is no music without order … This is not a question, then, of ‘freedom’ as opposed to ‘non freedom’, but rather it is a question of recognising ideas and expressions of order. (Shatz Reference Shatz2018)

Animated notations provide idea tools ideal for expressing this kind of ‘order’.

7. LITERACY

The best performances of graphic and animated notation are undertaken by experienced musicians who have well-developed aural and ensemble skills, rather than ‘score-reading’ ability. Whilst the reading of common practice notations is undoubtedly a musical skill, it is one most often aligned with the classical canon, and, as pointed out earlier, does not apply to the majority of music practised today. This then brings up the question of literacy when it comes to reading notations more broadly. How can we develop a literacy around alternatives to common practice notations, whilst maintaining the key aspects of music practice – listening, collaborating and independent stylistic development?

The ease of reproducing animated scores is problematised due to the lack of a common system applied to these notations. As with sound spatialisation – despite the interesting propositions developed by Denis Smalley, Stuart James and others – there is currently no consistent rule of thumb established for reading or presenting animated notations and the digital systems that support them. The TENOR network, established by Sandeep Bhagwati at MatraLab in 2018, is joining researchers and practitioners exploring notations worldwide, seeking to bring together this range of fragmented approaches, platforms, software and applications to develop an understanding of how we can best organise and retain alternative notation approaches, whilst maintaining decodable, flexible literacy in the area.

When looking at a variety of graphic and animated notations, the dilemma becomes apparent. Each one seems to have its own legend of literacy: the oft invisible levels of automation between one score and the other can change radically, the degree of openness is variable, and any related software is often bespoke and at risk of imminent obsolesce. Even seemingly simple musical constructs, linked to a long history of common practice notations, can be deceptively complex when presented in this format. For example, a commonly understood part of reading graphic notations has been the engagement of proportional or time space notation. The screen in animated notations, as the page in traditional Western notations, is used to define a series of parameters. The top is often the highest, the bottom the lowest. But of what? The instrument’s range? Or of all the instruments in the piece? Where is the top – top of the screen? Is it the same for every instrument? Often it is left for the performers to decide. When is the material pictorial, when is it symbolic? Do we always need a ream of bespoke instructions to understand the piece? These hierarchies may be intuitive to acoustic instrumentalists, but are likely to be less so for electronic musicians.

This is where some common practice guides could be formulated, or taught. Composers need to provide clarity around their aims, noting the parameters important to them, as well as those less so. This has implications for the way we teach composition, as well as the methods we choose to analyse extant works. As pointed out earlier, recordings help assist our reading of these scores beyond the life of a composer, and will serve an increasingly valuable role when it comes to the preservation and understanding of these works into the future.

Perhaps one area that needs attention in the process of realising the potential of animated notations is the musical literacy of colour. Currently, it seems colour in graphic and animated notations is assigned largely ad hoc. Once prominent in music scores of the Renaissance period, colour eventually become too expensive for reproduction via the printing press. But digital technologies have made colour both affordable and distributable again. Apart from a few examples of using colour to highlight certain aspects in tablet score readers and notation programs, there is little creative engagement with the potential of colour in contemporary score design. What musical concepts could be better communicated quickly and more effectively with colour? As a simple first step, colour has been used to discriminate individual players parts in a graphic score clearly. In the Lindsay Vickery/Cat Hope work ‘The Talking Board’ (2011), each performer is ascribed a coloured circle to follow (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Lindsay Vickery/Cat Hope, ‘The Talking Board’ (2011). Score showing circles that would each have a separate colour (original image in colour).

Performers parts are represented by different animated coloured circles that traverse an image on the screen, reading what is inside the circle as music notation. The circles have behaviors that include following each other, flocking together, getting larger or smaller or remaining static. Shades of colour can refer to volumes, sonic textures or provide guides to pitch and rhythm. Works such as this raise questions about cognitive preferences for which colour or shade communicates certain values. Colour is commonplace in descriptive imagery for data visualisation such as sonograms and spectrograms, but rarely in scores. We could be applying research from other disciplines such as design and colour theory to better realise what is possible, and recent publications explore this idea in more detail (Vickery, Devenish, James and Hope Reference Vickery, Devenish, James and Hope2017). Colour could contribute to a more intuitive process for performance, perhaps even with a degree of synesthesia, which could lead to a type of ‘semantic soundness’ where it looks more like it sounds (ibid.: 20).

Further to Vickery’s research, animated notations provide opportunities for non-linear solutions to score reading, as seen in ‘The Talking Board’. There is also potential for a more embodied, physical approach to music, and scores read by musicians could also be read by dancers and actors. Whilst choreographers have attempted to notate movement through a range of systems, animated notations may guide the facilitation of the body as an instrument in real time. They can engage and determine movement in and through space and time – an area yet to be fully explored.

Common practice notation has not been particularly successful in navigating the flow of musical materials. This became particularly evident with the onset of electronic music, and extant notation struggling to prescribe or describe electronic music in any useful or meaningful way. Additionally, page turns, metric subdivisions, vague phrasing and articulation indications amongst other things have meant that much of a musician’s time is spent understanding how to use the marks on a score to create the flow so clearly intended in certain harmonic transitions and melodic nuance. This learning has developed a kinaesthetically embedded relationship to tonal musical literacy, perhaps explaining the difficulty of letting go of tonality as the foundation of ‘real music’.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi investigated the idea of creative flow in the late 1960s, describing it as a highly focused mental state, in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter, and used composers as some of his first subjects in his testing. Musicians have to almost defeat common practice notation to get to this state of flow, a state often discussed in relation to the reading of compositions during the early days of the new complexity movement. What if similar results were possible through more direct pathways? Animated notation presents musical materials in motion, which could facilitate the creativity flow; information may unfold and be decoded at any desired rate, direction, frequency or density. The smooth and ongoing nature of animated notations can guide a sense of flow, rather than dictate it.

Since the 1800s, common practice notation has been cited as a barrier to musical engagement. Animated notation provides a more accessible literacy for reading music, using colour, shape and movement as key indicators over dots and lines. In the digital format, it can be easily shared and navigated. It has the possibility to be understood by musicians globally, and it should also be informed by notation practices globally. Digital graphic and animated notation allow traditional Western music notation readers (such as classical musicians), non-music reading improvisers (such as jazz, pop) and non-music reading folk musicians to follow the same music together, and combine it with other art mediums.

Musical games have existed through music history, recent popular forms being found in video games such as ‘Guitar Hero’ and ‘Dance Dance Revolution’. It has been argued that these games play an important part in a process of democratisation of music, making a different type of engagement with musical ideas available to a wide audience, now collaborating internationally over the internet. The popularity of these animated notations signals a transition to an engagement with music that does not depend on any formal music training, just aural familiarity. They have the potential to put a degree of musicality in reach of a great number of people. The rapid growth of digital tools has seen a move towards hands-on, realtime production. Additionally, since the introduction of MIDI in the 1980s, the increasing accessibility of digital workstations within portable computers has removed barriers associated with music production and performance, just as the internet has with collaboration (e.g., Google Docs). Whilst profit motivations of some hardware, software and licencing companies tends to turn music practices away from the exploratory, the open source market is still growing and new independent distribution technologies are constantly being developed. A younger generation of people have a different relationship to digital technologies, expecting most things they do will have some digital, if not online, component. The success of the Score Follower YouTube page hints at this interest in its presentation of even the most common traditional Western notation as mobile, rather than static, scores. Composers ignore this digital expectation at their peril, and could embrace a new era of more collaborative outcomes in music creation.

The replacement of traditional notations or practices is not what is needed; rather, a change of emphasis towards a more democratic, collaborative way of thinking about music. The impact wielded by ensembles such as Cornelius Cardew’s ‘Scratch Orchestra’ (Cardew Reference Cardew1972) and the influence of Butch Morris Conduction in the improvers orchestras (Morris Reference Morris2006) worldwide are only one part of what is possible. Composers engaging with animated notations seek something of a half-way place, where the most controlled and free can come together.

8. POTENTIAL

It is worth noting that similar levels of technology are not necessarily ubiquitous in all corners of the world. But neither is access to music libraries or other custodians of music copy. There will be little increase of hard copies in our libraries around the world, and soft storage will need to grow faster. The complex, often multifaceted nature of digital music poses a challenge to our archivists, and a national standard needs to be developed around how to preserve, store and share digital scores and their associated software. There is no doubt that a considerable portion of music has not been stored or archived in a reliable way, with some commentators noting that at least 15% per cent of material between 1980 and 1995 is lost or irretrievable (Jeffery Reference Jeffrey2012: 562). Rather than standardising an approach to creation – something extremely unlikely – archives will need to create flexible and open methodologies for representation and providing access to digital music in all its forms. Their practices, which have until the last century focused on singular items, need to facilitate plurality. Perhaps now is the time for what Morton Subotnick called the ‘ghost score’ (Bhagwati Reference Bhagwati, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013: 169) to render itself a visible and preservable part of the package providing a true notation for works featuring computer software.

This idea of the score being a multiplicity of things supports the potential of animated notations to contain as well as convey sound, realising what Simon Emmerson came to call the ‘superscore’ – where notations could embed sound within them (Emmerson Reference Emmerson2016: 127). This is an extremely exciting development that is yet to be fully explored, not just for new works, but also for historic works involving instruments and tape, for example. This could bring a new life to these works, seeing increased access, accuracy and facility. The iPad score for the co-composed work ‘The Last Days of Reality’ by Cat Hope and Lionel Marchetti (Hope and Marchetti Reference Hope and Marchetti2018; Figure 5) features what Marchetti calls a ‘partition concrète’, an audio file embedded into the score file uploaded to the reader application, the Decibel ScorePlayer (Hope, Vickery, Wyatt and James Reference Hope, Vickery, Wyatt and James2015; Wyatt, Hope, Vickery and James Reference Wyatt, Hope, Vickery and James2013). The score unfolds at the rate of Marchetti’s ‘partition concrete’, carefully synchronised with it.

Figure 5. Cat Hope and Lionel Marchetti ‘The Last Days of Reality’ (2018). Score with a ‘partition concrète’ embedded in the Decibel ScorePlayer (original image in colour).

9. CONTEXT, CULTURE AND A COMMUNITY OF PRACTICE

In moving from a text-based culture to one mediated by image and sound, global and cultural awareness is increasingly more collaborative and polystylistic. The performance of music provides an intimacy to this monolithic mixing pot of materials. A score can not only facilitate the realisation of a performance, but also the expectations of a community (Coessens Reference Coessens, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013a: 63). It is a signal to a community of practice, not a representation of it. A work embodies a community of practice, making the score a construct of the traditions in that community. A score for a work propels this sense of community, time and place.

To date, animated notations have been categorised in musicology as ‘experimental’, that place where only the strangest and most alien of music is found. Rather, the animated score could become a place where disparate fields of interest intersect, and the range of diversity that constitute a community of practice can sit by side, and with other communities – through internet collaborations, or polystylstic readings. Figure 6 shows a screenshot of the microtonal chimes that feature in score for the Twitterphonicon (Armstrong and Cole Reference Armstrong and Cole2014). This work demonstrates that animated notations can facilitate the integration of new media for automated performance or for later performance by musicians. The work is almost ambient in nature.

Figure 6. Warren Armstrong and Amanda Cole, Twitterphonicon (2014) (original images in colour on a black background).

10. CONCLUSION

It would seem that this is the time for notation to come of age, and facilitate music reading for electronic music as well as other musics more traditionally associated with the process or reading. Animated notations have the capacity to encapsulate sound both literally and descriptively, making them ideal for a more inclusive and collaborative music-making. They better serve the materials of contemporary practice, where electronic sounds play a central role and composers are working more collaboratively with performers. The capacity of animated notation to mix many different notations in a dynamic digital format is still being understood. If we look at the different types of written notations in use today, in their neumic, symbolic, graphic and verbal forms (Bhagwati Reference Bhagwati, de Assis, Brooks and Coessens2013: 171), animated notation can include, and enable, them all.

Animated notations offer the possibility of a more collaborative, democratic and world-encompassing approach to music notation that could bring together musicians from different styles, empowering musical praxis for both performers and audiences.

Common practice notation is not dead – rather, it will continue to serve music wedded to predetermined harmonic and rhythmic structures. There will always be music that needs no notation at all, that will continue to thrive and evolve as it embraces the new sonic possibilities brought to bear through technology. Animated notation leverages the contemporary digital technologies that are already a large part of our lives, making notation dynamic, accessible and easy to share. Screen notations, including animated notations, can facilitate the inclusion of audio recordings into the score paradigm, creating a major shift in the way we read, understand and remember music. With a revisioning of copyright, animated notation will enable music reading to thrive, enabling truly collaborative and participatory creative art making that can grow and develop with our times.

Acknowledgements

The ideas for this article originated in a keynote address given at the Fourth International Conference for Technologies of Music Notation and Representation, held in Montreal, 2018, at the invitation of Sandeep Bhagwati.