1. INTRODUCTION

Electroacoustic music repertoire addressing voice, poetry and text has been an influence in shaping my compositional outcome since I started acousmatic creation in 2004 (Albornoz et al. Reference Albornoz, García-Gracia, Schumacher, Brnčić, Becerra-Schmidt and Candel2006; Albornoz Reference Albornoz2016). Over the years, my artistic practice has been nurtured by several forms of experimental poetry, ranging from authors of the historical avant-garde to electroacoustic poetryFootnote 1 and hybrid art forms such as media poetryFootnote 2 or electronic literature.Footnote 3 In particular, this article focuses upon a selection of specific ideas that are of high relevance for the composer’s practice, including aspects of the historical avant-garde where Vicente Huidobro’s aesthetic theory, named Creacionismo, stands out as the main driving force.

2. VICENTE HUIDOBRO AND THE CREACIONISMO

The Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro was born on 10 January 1893 in Santiago de Chile. He was the son of an aristocratic family and his mother, María Luisa Fernández, was an active writer, artist and feminist. Indeed, it was her support and inspiration that pushed him in 1911 to publish his first text at the age of eighteen (Goic Reference Goic and d. Costa1975). Until 1916, his poetry was very close to Modernismo,Footnote 4 but it was starting to expose some personal ideas regarding the creative process, claiming the need for an art avoiding mimesis and favouring instead an intermedia approach to creation to achieve this avoidance. In fact, in 1914 he gave a presentation at the Ateneo Footnote 5 de Santiago entitled ‘Non Serviam’Footnote 6 (Arenas Reference Arenas and d. Costa1975), a manifesto which inaugurated his new ideas. The manifesto was published originally in 1925 in Manifiestos (Huidobro Reference Huidobro2009: 15–16). This book, reprinted in 2009, is a collection of various theoretical texts covering his aesthetic ideas, including his notions of the creative process, the role of the poet in the twentieth century, and analysis and comparisons with the previous literature and others artistic movements of his time, such as futurism and surrealism. Some lines of the manifesto are extremely direct in terms of the transforming aesthetic of Huidobro:

The poet says to his brothers: ‘Up to now we have done nothing but imitate the world in its aspects, we have created nothing. What has come out of us that was not previously in front of us, around our eyes, challenging our feet or our hands? … Non serviam. I do not have to be your slave, Mother Nature; I shall be your master … I shall have my trees which will not be like yours, I shall have my mountains, I shall have my rivers, I shall have my sky and my stars. And you will not be able to tell me: “This tree is bad, I don’t like that sky … mine are better.”’ (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999)Footnote 7

This passionate statement against mimesis is consistent with his will of autonomy for art with regards to real-world objects and entities as models to be imitated: ‘For Huidobro, the aesthetic phenomenon should exist like a plant, a star, or a fruit, with its own reason for being’ (Sarabia Reference Sarabia, Greene, Cushman, Cavanagh, Ramazani and Rouzer2012: 316). At the same time, Huidobro emphasises the crucial role of the poet as an individual, a demiurge creating worlds and beings: ‘The poet is a little God’ (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999).Footnote 8 Creation is personal, therefore its outcome, the artwork, is independent of the way the world works; in this way, the artist creates a new world. Argentinian architect and art researcher Alejandro Crispiani, explains Huidobro’s theory:

the poet … gives birth to a universe that is his own and that is closed in a certain way. The creationist poem represents a parallel world that is not touched with the real; is installed in reality as a different reality, absolutely resistant to it and its operating principles. (Crispiani Reference Crispiani2011: 66–7)Footnote 9

In this way both poetry and art more generally would imitate nature not in its realisations and constructs but in its way of acting, that is, as a creative entity (Sarabia Reference Sarabia, Greene, Cushman, Cavanagh, Ramazani and Rouzer2012: 316). In other words, if nature creates original things that are placed in the world, Huidobro asks to avoid imitation of these objects and rather encourages us to create as nature does.

In a conference given in 1916 at the Ateneo of Buenos Aires, Huidobro claimed: ‘the first condition of the poet is to create; the second, to create, and the third, to create’ (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999).Footnote 10 This statement motivated the Argentines to baptise him as a creationist in a foundational moment where the name of the theory was coined: Creacionismo, thereby summarising Huidobro’s ideas of avoiding imitative art in the search for sheer invention.Footnote 11 Huidobro’s goal, namely the invention of new facts and new objects, is tackled by him through the exposure of unexpected relationships between pre-existing elements (things from the real world) (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999). Thus, the artist uses elements of the objective world and, by means of combining and transforming them, obtains new facts to be added to the world (Huidobro and Goic Reference Huidobro and Goic2003: 1311). From this, we might identify a range of key procedures advocated by Huidobro, including the relocation, re-contextualisation and transformation of concepts, images and sounds. These procedures are realised by creating new words, combining pre-existing ones, connecting adjectives to nouns in unexpected ways, and ultimately through the dislocation of language in pursuit of a pure sonic content of syllables and phonemes.Footnote 12

In addition to what has been discussed earlier, Huidobro claimed to have identified a conceptual path for his theory, which is different from the guidelines of two of the most relevant avant-garde movements of the twentieth century: Italian futurism and surrealism. With futurism, the poet maintains a certain distance, especially regarding specific principles by considering them as old or absurd (the admiration for recklessness, the exaltation of war, contempt for women), although he valued the idea of liberation of words and verses (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1914: 163–71).Footnote 13 Regarding surrealism, the Chilean poet rejects the advocacy of the subconscious as the main engine for artistic creation, since he considered this surrealist premise impossible and also an attempt to fragment the human mind. In fact, Huidobro believed that humans act according to both, reason and the subconscious (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999).Footnote 14

In accordance with the aforementioned, Huidobro argues that poetic activity involves two aspects: reason and imagination. This duality, he argues, is representative of the dual nature of human beings. Consequently, he states a condition that enables one to achieve the creationist goal: the poetic delirium or superconsciousness. This is a particular state in which delirium involves fluctuations between reason and imagination, producing a conjunction: ‘a kind of intensive convergence of our entire intellectual mechanism’ (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999).Footnote 15 The poet’s delirium allows for the discovery of unexpected relationships between elements (words, images, sounds) by means of the different techniques mentioned: creation of new words, connection of adjectives to nouns in unexpected ways, and highlighting of sonic content of words and phonemes. Section 3 of this article describes the way this procedure is applied to acousmatic composition and section 4 gives a specific example of it. It is interesting to note that the outcome of this procedure, the unexpected relationships, is coherent with several notions and findings established by researchers on creativity and cognitive science in the last decades of the twentieth century. This is the case of ideas by David Gelernter (Reference Gelernter1994: 16–17) and Keith J. Holyoak (Reference Holyoak, Smith and Osherson1995: 286–9), who state the central role of restructuring information and creation of unexpected analogies as tools of creative thinking.

Although Huidobro refused to describe his poems as cubist (Castro Morales Reference Castro Morales2008: 153), certain techniques associate his works with cubist poets such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Pierre Reverdy and Max Jacob; techniques such as fragmentation and juxtaposition are heavily used in their works, and these became cornerstones of the cubist style. Having arrived in Paris in 1916, Huidobro joined the avant-garde circle, interacted with various artists and released several poetry books (Arenas Reference Arenas and d. Costa1975).Footnote 16 Albeit keen to pursue his own artistic agenda, in his endeavour there are clearly connections with dadaism, surrealism and futurism, and these connections are reflected in some ideas and techniques, such as calligrammes,Footnote 17 painted poems Footnote 18 and simultaneism,Footnote 19 which were used in his poetry or enunciated in some projects (Huidobro and García-Huidobro Reference Huidobro and García-Huidobro2012). All the ideas reviewed so far coalesce in his masterpiece, Altazor (Huidobro Reference Huidobro2016) also known as Altazor o el viaje en paracaídas.Footnote 20 This poem in seven sections named chants was started in 1919, but only published in 1931 in Spain. Altazor is a sky voyager, described by Sarabia (Reference Sarabia, Greene, Cushman, Cavanagh, Ramazani and Rouzer2012: 315–16) as ‘an anti-poet and a “high-hawk” aeronaut … (travelling) into the realms of nothingness, the “infiniternity”’. The poetic journey is in fact a metaphysical trip in seven stages corresponding to each chant of the poem, gradually leaving behind an old language in favour of a new one and, eventually, leading to the disintegration of meaning through the use of only the sonic semblance of Spanish words and, at the very end, just phonemes lacking any linguistic meaning. According to Cussen (Reference Cussen2014), this famous poem is regarded as one of the foundations of sound poetry Footnote 21 in Chile and Spanish America by several authors and it has been the subject of much analysis. Beyond this, there are numerous musical pieces inspired by the poem; although various chants have drawn critical attention, most have focused upon the final chant, due to its sonic properties (Cussen Reference Cussen2014: 82–6). I have avoided using Altazor as direct source or to undertake the task of a new musical version of it.Footnote 22 As result of the previous idea, my compositional process during the last years was influenced only by the idea of language fragmentation present in Altazor.

Summarising, the creationist artwork has three characteristics: independence from the real world, resistance to the real world and action according to its own other-worldly rules (Crispiani Reference Crispiani2011: 66). Considered in such a way, the poem can be understood as a device that functions as a system of elements or actions (words, images and sounds evoking an aesthetic reaction from the receiver) or, perhaps, as a machine. In his manifesto El Creacionismo, Huidobro stated parallels between artistic activity and the creation of machinery: ‘What has been done in mechanics has also been done in poetry’(Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999).Footnote 23 In the manifesto La Creación pura: ‘Is not the art of mechanics also the humanization of nature …?’ (Huidobro and Goic Reference Huidobro and Goic2003: 1311).Footnote 24 According to Crispiani (Reference Crispiani2011), poetry, under the light of Huidobro’s ideas, is able to articulate new human potentials afforded by machines. In this way, poems and machines share the same function; one has as much artificiality as the other (Crispiani Reference Crispiani2011: 66).

3. CREACIONISMO APPLIED TO ACOUSMATIC MUSIC

The compositional method I have, intentionally draws upon a number of these concepts. The system, both subjective and heterogeneous, has been described thoroughly in my PhD thesis (Albornoz Reference Albornoz2018), which included eight acousmatic compositions and can be summarised as a combination of planning general notions and conditions with an experimental and intuitive approach to sound objects (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1966) and spectromorphologies (Smalley Reference Smalley1997) production. This combination of intense rational and imaginative actions led to:

-

Selection and rejection of materials from the real world according to a personal system (Huidobro and Goic Reference Huidobro and Goic2003: 1311–13). In this way, the elements from reality enter the artist’s subjective world.

-

Transformation and combination of selected elements from the world (images and sounds), by means of techniques appropriate to their nature, the aesthetic intentions and expected concrete form of a given piece. Since the main part of my work corpus deals with voice and poetry as inspiration and material, this implied the recording of recitations in the studio, the subsequent selection and edition of them and the use of sound transformations applied to them. In this way, the combined elements were delivered back to the real world in the form of a piece. Again, although there are some systematic actions carried, the general procedure was open, not rigid and specific to each piece. The establishment of adequate techniques appropriate to the nature of each element, the aesthetic intentions of the author and the concrete form of the pieces require a longer text, which in fact is a detailed description provided in the doctoral thesis previously mentioned.

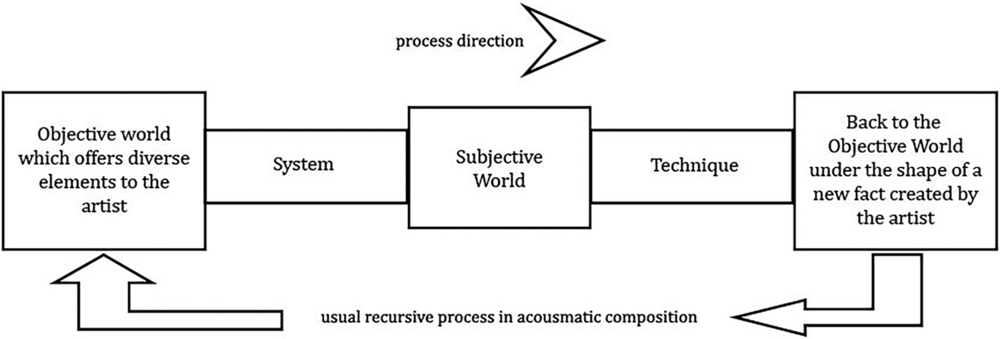

In Figure 1, Huidobro visualises the creative process through a diagram in his manifesto La Creación pura (Huidobro and Goic Reference Huidobro and Goic2003: 1312).

Figure 1. Huidobro’s diagram of poetic production (the arrow signalling the process’ direction is not in the original).

As Marta Rodríguez explains:

In Huidobro’s scheme ‘two bridges’ of interaction are considered: system and technique. The first includes similarity and abstraction operations, by means of which some elements are selected, i.e., some properties are chosen while others are eliminated. The second bridge is technique whose function is to combine those elements. (Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2000: 22)

Poetic delirium or superconsciousness, the special human condition described by Huidobro in his Manifiesto de manifiestos (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999), is the essence of the pair system-technique, first and second bridges respectively. Since poetic delirium involves fluctuations between reason and imagination, the poetic production process ‘could be originated by sensibility or intuition, but when it sees the light, intelligence starts to function’ (Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2000: 23). The second bridge, technique combines and transforms the selected elements and shapes the poem in doing so. The criteria which guides the processes of abstraction and similarity within the system would depend on the poet as an integral human being, with his or her specific sensibility, intelligence, interests and cultural background. What exactly constitutes the second bridge, technique, depends on the poet, his or her skills, concrete means and ultimately his or her knowledge. According to Huidobro (Huidobro and Goic Reference Huidobro and Goic2003: 1312) the degree of concordance between poet’s technique and the selected elements from the objective world, determines his or her artistic signature, the style.

Having considered this scheme, its functionality and definitions can be applied to acousmatic composition. Since the acousmatic creative procedure implies the creation of sound and structures at any point during the composition, the resulting sounds (and even the final piece) can be incorporated into a recursive process as many times as the author thinks necessary to conclude a specific work or to generate materials for different pieces (Moore Reference Moore2016: 7; Chion Reference Chion2017: 15–16). This can be represented as in Figure 2, slightly changing Huidobro’s original diagram.

Figure 2. Huidobro’s diagram adapted to acousmatic compositional process.

According to this, the compositional method produces a novel outcome (a new fact,Footnote 25 an artwork) each and every time it is used. Furthermore, this outcome is deemed to be self-sufficient, in other words, its own existence constitutes its purpose. Following the manifesto La Creación pura, the new fact given back to world is an aesthetic phenomenon completely free and independent, ‘like any other phenomenon of the external world, such as a plant, a bird, a star or a fruit, and like these, has its reason of being in itself’(Huidobro and Goic Reference Huidobro and Goic2003: 1311).Footnote 26

Accordingly, in reference to the development of this method drawn from the ideas of Huidobro, the term acousmatic-creationist has been adopted to define the pieces I have composed from this period and on.

4. ACOUSMATIC-CREATIONIST NATURE OF THE OCTOPHONIC CYCLE LA LUMIÈRE ARTIFICIELLE

The cycle La lumière artificielle was composed between 2015 and 2018 and was inspired by an idea of a specific project by Vicente Huidobro and includes five octophonic pieces dealing with voice, poetry and non-semantic materials provided by four feminine performers speaking in three languages: French, Spanish and English. Thus, this cycle deals with voice and poetry as inspiration and actual sonic material addressed through the acousmatic-creationist procedure described and influenced by both electroacoustic music background and avant-garde poetry.

The idea emerged from an interview with Huidobro by Ángel Cruchaga Santa María for El Mercurio newspaper on 31 August 1919, where the poet talks about the avant-garde artistic environment in Europe within the first two decades of the twentieth century. The interview reveals his panoramic vision of poets and artists and, at the same time, outlines some of his own activities and projects. There is an interesting statement in this document, referring to a project, an idea that was never released. When the interviewer asks him ‘¿Qué obras tiene en preparación?’ (‘Which pieces are you preparing?’) (Huidobro 1919 cited in Huidobro and García-Huidobro Reference Huidobro and García-Huidobro2012: 34), the Chilean poet discusses some of his later completed works, but his comments on the non-implemented work are particularly inspiring:

The creationist and simultaneist poem La lumière artificial, for three voices on gramophone with new procedures. (Huidobro 1919, cited in Huidobro and García-Huidobro Reference Huidobro and García-Huidobro2012: 34)Footnote 27

It is possible to see similarities with techniques and notions already developed by Huidobro’s contemporaries, including Ilja Zdanevic, Tristan Tzara and Jules Romains, Russian futurist, dadaist and unanimist, respectively.Footnote 28

At the same time, the project suggested a physical setup, namely three voices on gramophone evoking a multi-channel distribution. Since in Huidobro’s statement there is a proposal of simultaneism, it was imagined that there would be three gramophones surrounding a central space, as in multi-channel set ups for acousmatic music.

As has been mentioned, Huidobro was a pioneer in the creation of intermedia pieces and a referent for sound poetry and sound art in Spanish America. The fact that the poet lived in Santiago de Chile and Paris and wrote in both Spanish and French is a central inspiration for the cycle La lumière artificielle. Huidobro valued the translation of poetry from one language to another and, as a matter of fact, in his manifesto El Creacionismo (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999) the artist explicitly articulates this idea and gives an example of the same verse in French, Spanish and English.Footnote 29 In this manifesto, the poet points out that it is impossible to translate the sonority of a poem, the inner musicality of words. But if the central element is an image or an image/idea, it can be translated to any language. In doing so, the poem is enriched with different sonorities of the different languages (Huidobro Reference Huidobro1999).

Considering this and the theoretical framework defined, the driving ideas of the project as a whole were to:

-

Compose using words and speech sounds from three languages: French, Spanish and English. This was motivated by the concepts explained earlier (‘three voices on gramophone’ statement, simultaneism and the valorisation of translation).

-

Compose in a multi-channel format. The motivation for this was the implicit spatiality in Huidobro’s concept of ‘three voices on gramophone’, from where it was assumed arbitrarily each of them located in a different gramophone. The octophonic format was selected for two reasons: it was available in the University of Sheffield Sound Studios where the cycle was composed and it is considered one of the most widely implemented standards (Vande Gorne Reference Vande Gorne2010: 165).

-

Use vocal materials, ranging from semantic content expressed through words to non-semantic materials by means of word fragmentation and disintegration; in other words, to compose using the movement between these two poles, semantic/non-semantic as an articulatory and structuring procedure. This is one of the core aspects of the cycle and the rest of the PhD portfolio. The first two minutes of Hundreds of milliseconds (Finale) can be listened to in Sound example 1, providing an idea of some of the ways in which these procedures have been addressed.Footnote 30

-

Use extensively simultaneity or juxtaposition of sounds in the immersive space provided by the octophonic format. Sound materials can be clarified, interweaved, densified through multi-channel composition, while at the same time spatial configurations and movements can be defined and traced respectively. Those possibilities were used to generate unexpected relationships between the intersected and juxtaposed materials. Again, this is widely supported by the previous theoretical notions.

-

Encompass the use of simple audio editing techniques alongside sophisticated digital processing, such as cut and paste and granular synthesis. Sound example 2 shows a typical development transiting from a discreet materials montage to a complex texture that includes cross-synthesis between voice and electronic synthetic sound, an example taken from La Luz, from 3′28″ to 4′28″. This characteristic, typical of this artistic genre, allowed a creationist approach to the compositional process, crafting and extracting unexpected relationships and new objects respectively.

-

Use of pre-existent texts, taken from philosophical and scientific sources, in order to enrich the conceptual content and, at the same time, show that the use of already-existing cultural products is possible following the acousmatic-creationist diagram (Figure 2).

The cycle is made up of five pieces: Overture, La Lumière, La Luz, The Light and Hundreds of Milliseconds (Finale). Each of these five sections of the cycle engages with a range of specific and general ideas. This pentalogy can be listened to as whole, in the order proposed or not, or as individual pieces. The sound source material for the entire cycle was generated from the original Huidobro interview and the phrase ‘la lumière artificielle’ recited by three female voices, each in one of the three languages defined: French, Spanish or English. Sound materials related to the gramophone as direct samples with connotative features were also used.

Two more texts were added to form the initial sound/conceptual palette:

1. A text by Friedrich A. Kittler, taken from his book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, a publication translated from the original in German by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Kittler, Winthrop-Young and Wutz Reference Kittler, Winthrop-Young and Wutz1999). The book is a historical review of the techniques for sound and image recording and of the printed word, and at the same time is a theoretical discussion of the ontological, artistic, linguistic and discursive aspects generated by these technologies. Some sentences, featuring ideas related to aesthetical and communicational implications of recording and reproduction of sound and image, were selected from the introductory paragraph of the book. The original sentences and words in the English version of the book are:

• ‘What phonographs and cinematographs … were able to store was time … Time determines the limit of all art … To record the sound sequences of speech, literature has to arrest them in a system of 26 letters, thereby categorically excluding all noises sequences’ (Kittler, Winthrop-Young and Wutz Reference Kittler, Winthrop-Young and Wutz1999: 3).

• ‘Gramophone’

• ‘Phonograph’.

These words were subsequently recorded in English, French and Spanish.

-

2. A selection of paragraphs, sentences and words from a scientific article on human language by Colin Phillips and Kuniyoshi Sakai; this text, entitled ‘Language and the Brain’ (Phillips and Sakai Reference Phillips and Sakai2005: 166–9), was recorded after the first four pieces were finished; the reading was done by a new female voice and only in English. Originally, the text was part of an alternative project to this cycle. That project, entitled Ruido, consisted of a dance-theatre play directed and performed by Sheffield-based dance artist Lucy Haighton, involving acousmatic music and live electronics by myself and carried out between October 2016 and February 2017. Some sounds derived from this text were added to the previously composed sections (especially to the Overture); the main paragraph was slightly adapted by the performer by including the words ‘such as’; the text and words from this article are:

• ‘Many species have evolved sophisticated communication systems’ such as ‘(birds, primates and marine mammals), but human language stands out in at least two respects which contribute to vast expressive power of language. First, humans are able to memorize many thousands of words, each of which encodes a piece of meaning using arbitrary sound or gesture … Second, humans are able to combine words to form sentences and discourses, making it possible to communicate an infinite number of different messages and providing the basis of human linguistic creativity. Furthermore, speakers are able to generate and understand novel messages quickly and effortlessly, on a scale of hundreds of milliseconds’ (Phillips and Sakai Reference Phillips and Sakai2005: 166).

-

• ‘Evolve’

-

• ‘Humans’

-

• ‘Sound’

-

• ‘Expressive’

-

• ‘Communication systems’

-

• ‘Encodes’

-

• ‘Species’

-

• ‘Arbitrary’

-

• ‘Linguistic’.

The appropriation of these theoretical texts and the subsequent re-contextualisation of them into a poetic environment allowed the generation of an expressive artistic process propitiated by the acousmatic-creationist approach. The intention was to provide ambiguous material, situated in a blurred frontier, where it could be possible to assume them to be scientific, philosophical or poetic texts. This was possible thanks to the intuitive selection of the texts combined with a rational focusing in specific content related to human language. This selection process is part of what it was defined as the system in the acousmatic-creationist scheme in Figure 2.

The directive for the three women was to record the sentences in different ways, in an attempt to form a diverse palette containing both neutral and more expressive versions. Sound examples 3, 4 and 5 are samples of the original recording sessions, showing a normal speech in English with different intentionality, vocal games around syllables and non-semantic materials by the Spanish-speaking performer and vocal intonation of vowels in French, respectively. A significant degree of freedom was granted in the recordings, in agreement with each of the three speakers. Nevertheless, specific instructions were provided as general guidelines and some particular actions were requested as well. General instructions included speaking normally, in whispers, toned and aloud, emphasising certain aspects of their own natural intonation. Fortunately, each of the speakers delivered original propositions from these starting points. These vocal actions and ways of speaking were applied to all the texts, but special instructions were given for Huidobro’s sentence. In addition, it was requested of each performer to vocalise words, syllables and letters separately using the previous characterisations. In a natural way, some specific features of each language emerged in the process, prompting a request for the performers to accentuate these and to explore them freely, leading to the extension of durations and shifting of frequencies of some sounds, all of this during the direct recording of the performed voice.

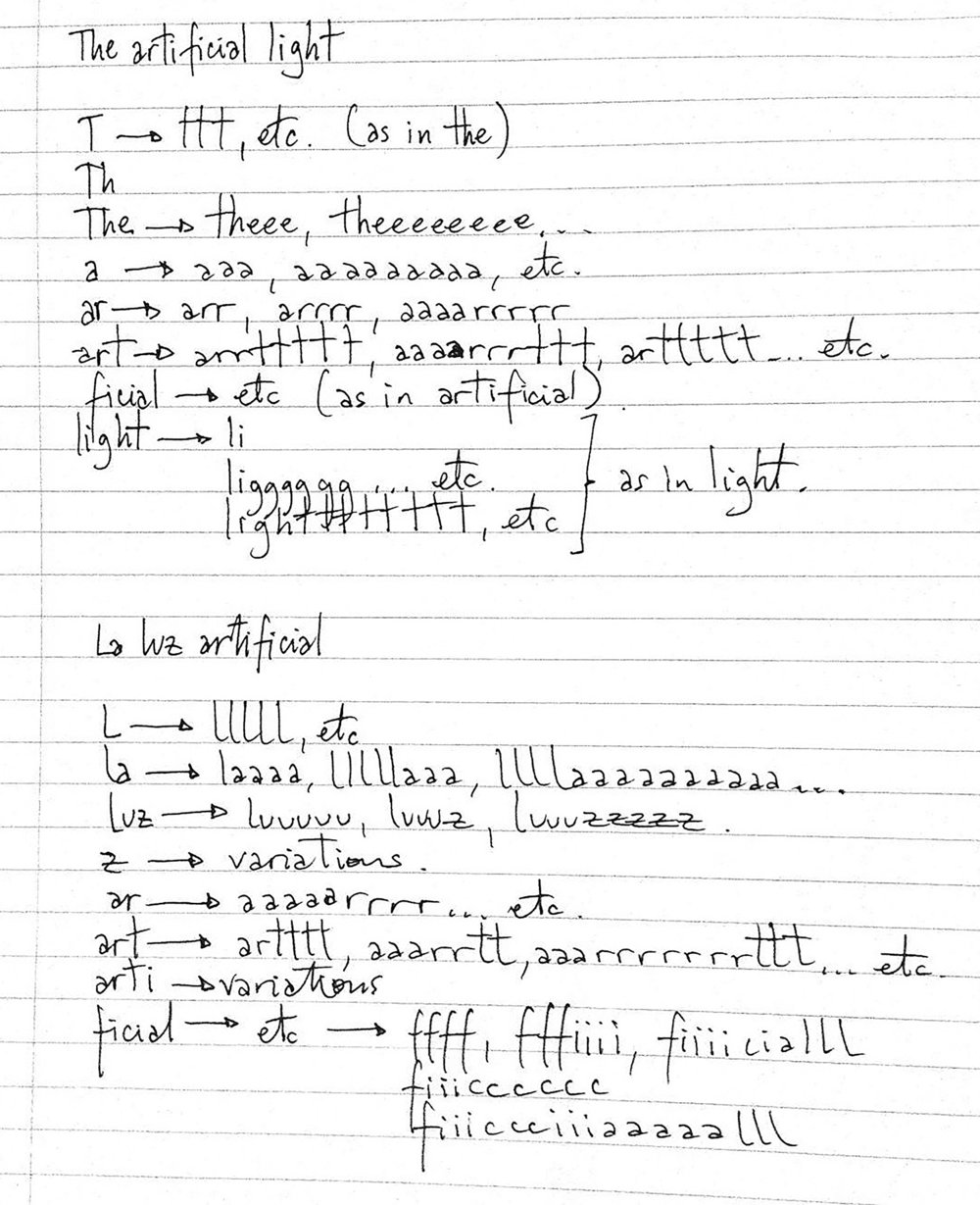

Using instructions inspired by Trevor Wishart’s own directions for Red Bird (Wishart Reference Wishart2012: 17–27), the initial set of commands can be seen in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Handwritten text with the instructions for the French speaker.

Figure 4. Handwritten text with the instructions for English and Spanish speakers.

All these sounds were arranged by a montage procedure, during which sequences, mesostructures and the pieces’ macro-forms were composed. As is proposed previously, by following the procedure described in the adaptation of Huidobro’s diagram (Figure 2), new sounds emerged in a recursive dynamic from this process. Additional non-vocal sounds, specific for each piece were produced by means of new recordings or synthesis and classified in similar ways (short, long and so on). Finally, all these techniques, conditioned by the concrete means used and the actual composer’s skills on this procedures, constitute the second bridge in the acousmatic-creationist scheme (Figure 2), which is precisely named technique: its use was through a hybrid action, guided by the balance between reason and imagination. This can be appreciated in the equilibrium of planed actions and the free space for improvisation and game, both during the recording sessions and afterwards during the acousmatic studio work process, all of which created a new fact, the piece, from elements taken from the real world combined in imaginative ways, following Huidobro’s guidelines.

5. CONCLUSION

This article has shown how the octophonic cycle La lumière artificielle was conceived, developed and forged into its final shape following the central notions of Huidobro’s creationism. During the selection of sound materials, composer’s imaginative intuition and rational thinking acted combined (superconsciousness state according to Huidobro). This is the first bridge, the system, in the acousmatic-creationist scheme. The same applies for the second bridge, the technique, which corresponds to the crafting process described in the previous section. At the same time, it has been stated that the convergence of several artistic notions, ranging from electroacoustic music to sound poetry, operating by the multi-layered intersection of cultural trends, including musical, poetic and scientific ideas, are implied by the texts present within the pieces. Accordingly, the idea of acousmatic composition in a multi-channel format has been shown to be efficacious to give a concrete multi-layered structure, where the concept of juxtaposition has a prominent function, thus connecting this formal aspect with the theoretical background addressed. Alongside juxtaposition, other techniques were key procedures, such as relocation, re-contextualisation, transformation, creation of new words, combination of pre-existing ones, connection of adjectives and nouns in unexpected ways and ultimately dislocation of language in pursuit of a pure sonic content of syllables and phonemes. These procedures were used in order to obtain the raw material (‘materia prima’ in Spanish) for the cycle according to creationism, namely with the intention of finding unexpected relationships between ideas, forms and sounds, through a creative process carried by merging reason and imagination.

Acknowledgements

This article has been written from the author’s PhD thesis which was funded by Advanced Human Capital Program, of the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research (CONICYT) of the Chilean government. The author would like to thank to the National Music Fund (FONMUS) of the National Culture and Arts Council (CNCA) of Chile that financed the release of the CD Fluctuaciones during the course of the doctoral research; to the World Universities Network and the Research Mobility Program at the University of Sheffield that provided funds to do a research visit to the University of Bergen and run the project Algorithmic poetry and electroacoustic music: possible connections and developments, which allowed the author to expand his knowledge and strategies for the whole research.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771820000291