1. Introduction

As with most languages, Anglicisms that appear in Norwegian generally adapt their morphology to the domestic model as they become established in the language. Verbs borrowed from English are virtually always instantaneously adapted to the Norwegian verbal system, whereas other word classes sometimes maintain morphological elements from the English system. By and large, nouns readily take domestic inflectional endings to form definiteness and plurality, but the morpheme -s can sometimes also be used to mark an unadapted plural, and for some words, e.g. cookie (sg), cookies/cookier (pl), adapted and unadapted plural forms coexist, leading to the phenomenon of overabundance (see Thornton Reference Thornton, Maiden, Smith, Goldbach and Hinzelin2011). In traditional and standardised Norwegian, the -s suffix is only used as an inflectional possessive suffix in nouns, not as a plural marker. One early researcher on Anglicisms observed that ‘it is therefore difficult for this suffix to function as distinctive of plural in foreign words’ (Stene Reference Stene1945:158). However, more recent research has documented its use as a plural marker with both recent and well-established Anglicisms (Graedler Reference Graedler1998; Johansson & Graedler Reference Johansson and Graedler2002; Andersen Reference Andersen2012a), and in some cases with domestic or non-English words (Sunde Reference Sunde2018).

A curious fact also observed in the literature is the occurrence of a phonological segment -s in nominal stems such as caps ‘cap’ (indef.sg), which has lost its plurality marking function and become part of the lexical stem, leading to forms such as capsen ‘the cap’ (-en being the Norwegian definite singular suffix). We take this as a sign of reanalysis of the lexical stem from an s-less form to an s-form which is not interpreted as a plural marker but as part of the stem: [cap]+[s]Footnote 1 (pl) → [caps] (sg). We henceforth refer to this process of reanalysis as s-lexicalisation (full discussion in Section 2.2). However, since the singular forms cap ‘cap’ and capen ‘the cap’ actually coexist with the forms caps and capsen containing the reanalysed lexical stem, we thus observe two types of variability relating to non-possessive -s in Norwegian, one concerning the presence or absence of a reanalysed s-form in the stem of Anglicisms like [cap(s)], and another concerning the use of a foreign -s versus a domestic plural suffix in Anglicisms and some other words.

This article explores this variability through a study drawing on written Norwegian data.Footnote 2 Our aim is to document the occurrence and productivity of non-possessive -s in contemporary Norwegian and to chart the lexico-grammatical categories instantiated by this morpho-phonological segment. Thus, the article gives a corpus-based survey of categories where non-possessive -s occurs, (i) as the plural marker of Anglicisms, e.g. drinks; (ii) in colloquialisms such as dritings ‘dead drunk’ – a reanalysed combination of a domestic stem and an English (or Norwegian) -ing + non-possessive -s; (iii) in nouns like en caps ‘a (baseball) cap’, where it has lost its plurality marking function and become part of the lexical stem; and (iv) as a plurality marker of domestic/non-English words such as temas.

We first give a brief outline of the literature on borrowing of morphological plural -s and on Anglicisms in Norwegian (Section 1.1). Next, we provide an overview of the usage of non-possessive -s, including an assessment of the extent to which this foreign suffix is productive beyond originally English words (Section 1.2). We explore the integration of the foreign suffix in two large and continuously expanding sets of data, a large newspaper corpus and a national text archive. The material is presented in Section 2. We can expect that the date of borrowing has a bearing on usage, so that well-established Anglicisms presumably are less prone to s-plural usage than incipient or very recent ones (e.g. Stene Reference Stene1945, Schmidt Reference Schmidt and Filipovic1982, Graedler Reference Graedler1998). We therefore explore further, in Section 3, the variability of usage of non-possessive -s in four case studies of different stages of borrowing, by zooming in on [trick] (first documented c. 1860), [cap] (c. 1930), [taco] (c. 1950) and [bagel] (c. 1970). For each item, we assess variation between a domestic and foreign plural suffix and the degree of s-lexicalisation. Finally, in Section 4 we discuss how s-lexicalisation appears to be affected by phonological and morphosyntactic factors, by reviewing the four case studies and by zooming out to consider a wider set of lexemes. Thus, the overall objective is to offer an initial corpus-based and hypothesis-generating rather than a hypothesis-testing study of non-possessive -s.

1.1 Previous research on borrowing of English plural formatives with special focus on Norwegian

There is a wide array of research that focuses on borrowing and Anglicisms in general, but relatively few contributions that address the topic studied here, the morphological borrowing of plural formatives from English to other languages. For German, Onysko (Reference Onysko2007) investigates the impact of Anglicisms, noting that ‘[p]lural formation is particularly interesting due to a partial overlap of English and German plural morphs’ (Onysko Reference Onysko2007:180). For domestic words ‘-s functions as the default morpheme if no other rules [for plural formation] apply’ (Onysko Reference Onysko2007:181, citing Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2002). Thus, in assessing the integration of -s as a plural morpheme in German and Norwegian, one important systemic difference must be acknowledged, namely that the suffix already exists as a domestic plural marker in German, albeit numerically outnumbered by other domestic suffixes. This marks the plural of so-called ‘non-canonical roots’, such as onomatopoeic words, truncated roots and acronyms (e.g. Össis, BMWs), unassimilated borrowings (Jobs) and pluralising names and eponyms (Maiers, Porches). Citing Marcus et al. (Reference Marcus, Brinkmann, Clahsen, Wiese and Pinker1995:242), Onysko notes that the suffix entered German in the 18th and 19th centuries ‘through borrowings from Low German, Dutch, English, and French’ (Onysko Reference Onysko2007:182) and that this makes it complicated to distinguish plural formation in German from borrowed plural nouns. Nevertheless, Onysko observes that Anglicisms marked for plural in his newspaper corpus ‘exhibit a marked predilection for -s plural’, with 60% taking the -s suffix, while the remaining have zero marking (especially those with a stem ending in -er) or (rarely) a domestic plural suffix.

Saugera’s (Reference Saugera2012, Reference Saugera2017) work explores the inflection of English-origin nouns in French, which usually take a regular domestic plural, but notes an exceptional subset of nominal Anglicisms which take a bare plural, e.g. de terribles hang-over, and describes the morphosyntactic conditioning of such bare plurals. More relevant to the current study, she also notes that ‘[t]he borrowing of bound morphemes, although a rare phenomenon in language contact (Weinreich Reference Weinreich1953), is attested in French with the borrowing of English plural suffixes, which co-occur with native ones: English-like des sandwiches, des baggies, des barmen vs. French-like des sandwichs, des baggys, des barmans’ (Saugera Reference Saugera2012:134; our highlighting). Although this pertains not to the importation of the morpheme -s itself (which forms the regular plural in both English and French, as with German above), it presents an interesting case of a parallel variability to the one observed for Norwegian, e.g. in plural cookier/cookies. Saugera’s study also makes it evident that the French language council prescribes a regular French plural for loanwords (un jazzman, des jassmans, to the extent that such loans are standardised in the first place), which reflects a linguistic purism akin to Norwegian language policy. This is clear from the fact that recent (2019) standardisation of the Anglicisms brownie, cookie and cupcake in Norwegian only licences their domestic inflection cookier and cookiene but not s-plurals despite their common occcurrence in writing.Footnote 3

Further, González (Reference González2017) studies the realisation of plurality of Anglicisms in Spanish and observes considerable variability in its graphemic and phonological formation. An English-based plural like clubs alternates with domestic adaptations clubes and even clus, a simplificaton of the final consonant cluster. The -s/-es variability particularly affects monosyllabic nouns ending with a consonant not usually found in this position in Spanish (e.g. /b d g p t k/ as in drug, geek, etc.) or with nasals (fan, film). Some longer nouns enter a class of zero-plurals where plurality is clear from the morphosyntactic context, as in los sandwich mixtos ‘mixed sandwiches’. González also considers a few relatively rare classes of ‘hypercorrection’ which provide relevant points of comparison to Norwegian. This includes the ‘double plurals’ such as güisquises ‘whiskeys’ and jerseyses ‘jerseys’, and ‘singular use of plural forms’ (González Reference González2017:326, our translation and highlighting) as in un pin’s and un pins ‘a pin’ (cf. our discussion of caps in Section 1 above), which the author considers a phenomenon of ‘contamination and graphic hypercorrection’ (ibid., our translation).

There is also research that assesses morphological borrowing in comparison to other types of borrowing on the basis of hierarchies such as Weinreich (Reference Weinreich1953:35). The traditional view that it is easier to copy derivational rather than inflectional morphology stands refined by Gardani (Reference Gardani, Johanson and Robbeets2012), who argues that some types of inflection, in particular the nominal plural, are more accessible to borrowing than other types (see also various chapters in Johanson & Robbeets Reference Johanson and Robbeets2012). He predicts that markers of inherent inflection such as number and gender of nouns are more easily copied than contextual inflection such as case. In a typological study of a wide variety of source and recipient languages, his cross-linguistic evidence supports the argument that ‘plural is more similar to derivation than other categories of inflection and, second, in most instances, the plural borrowings investigated are formed via agglutination’ (Gardani Reference Gardani, Johanson and Robbeets2012:93). Citing Myers-Scotton (Reference Myers-Scotton2002), he concludes that ‘the borrowing of plurals is in line with the maintenance of plural inflection observed in bilinguals during code-switching’ (ibid.:77). Of particular relevance to the current study, Gardani notes that the pressure exerted by English ‘has led to the borrowing of the plural suffix -s in Welsh, especially in the dialects of Bangor and Caernarvon’ (Gardani Reference Gardani, Johanson and Robbeets2012:87). Predictably, this occurs mostly in recent loan words from English such as sgemers ‘schemers’ (alongside native Welsh plural sgimyr) and in long-standing loans such as ffarmwrs (alongside native Welsh ffermwyr) ‘farmers’, but it also applies to some native Welsh nouns, as his examples show.

The example studies so far show that plurality marking of Anglicisms quite commonly vacillates between native forms and the borrowed plural marker -s in remote (French, German, Spanish) as well as close (Welsh) contact situations. More generally, we can expect major variation between different languages with regard to the adaptation and use of English plural -s according to factors such as the degree of pressure from English, seen by the amount of borrowed Anglicisms and the national population’s English competence, etc. (e.g. Onysko Reference Onysko2007:184). In the remainder of this section we focus on research of Anglicisms in Norwegian.

Although contact between English and Norwegian has been documented from the Viking Age onwards, English has only had a remarkable influence since the technical and industrial revolution. In the 19th century, some English vocabulary was transferred to Norwegian, which is reflected in a few early dictionaries of foreign words and expressions (e.g. Hansen Reference Hansen1842) and a list of compiled Anglicisms (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1902), where only a few of the nouns were presented with -s endings (see Table 3 in Section 1.2 below). However, until the mid-20th century, only a small part of the population was exposed to and proficient in English, and Norwegian Anglicisms were not investigated in a meticulous manner until immediately prior to World War II, with Stene’s (Reference Stene1945) manual collection of Anglicisms. As indicated above, one of her conclusions was that ‘[t]he idea of plural is not connected with the morphological element -s in N[orwegian]’ (Stene Reference Stene1945:158). At that time English had not become the main foreign language in Norway, and ‘the plural function of -s is lost when the words become well assimilated’ (Stene Reference Stene1945:163). What Stene did observe, though, is that the -s appeared as part of the nominal stem of some nouns, both of neutral gender (tricks) and common gender (clips), as well as in uncountable nouns (pickles).

In the post-WWII era exposure to the English language steadily increased through various channels, and both language competence and borrowing from English expanded. Throughout this period -s has gradually been conceived as a marker of plurality in Norwegian. The bulk of loanwords have come after 1945, and several studies, both during the second half of the 20th century (see Graedler Reference Graedler, Furiassi, Pulcini and González2012) and more recently, have attempted to measure the impact of English on Norwegian. Schmidt (Reference Schmidt and Filipovic1982) describes the adaptation and integration of Anglicisms as a ‘movement along a scale’, illustrated by the development for nouns of different categories (gender, countable vs. uncountable, and singular vs. plural loanword). Notably for our purposes here, she argues that the plural -s is evident in loanwords at stages that precede the emergence of the domestic indefinite plural ending -(e)r, as illustrated in Table 1. However, she also admits that ‘[t]he dividing lines between these stages will always be somewhat fluid’ (Schmidt Reference Schmidt and Filipovic1982:364).

Table 1. Schmidt's model of the adaptation and integration of English loanwords.

* Parentheses in the penultimate row mark the uncertain status of this stage.

During the 1990s, the extensive research project English in Norway was carried out (see Johansson & Graedler Reference Johansson and Graedler2002 for details), and Graedler’s (Reference Graedler1998) study was based on manually collected data compiled as an Anglicism database. This work addressed a wide range of factors pertaining to the use and integration of Anglicisms. With regard to plural integration, the use of -s was shown to correlate with age and frequency in predictable ways (Stene Reference Stene1945, Schmidt Reference Schmidt and Filipovic1982) so that older and more frequent Anglicisms take domestic plural forms more so than recent and infrequent ones. Further, it was also shown to correlate with several other factors including the nouns’ length and complexity (short and simple elements tend to be more frequently integrated than long and complex ones like compounds and phrases), spelling (adapted forms tend to take domestic plurals), stem ending (Anglicism stems with ‘domestic-like’ forms -er/-ing tend to take domestic plurals), as well as semantic factors, users’ attitudes towards languages, and spoken vs. written language (Graedler Reference Graedler1998:127–146; Johansson & Graedler Reference Johansson and Graedler2002:187–192).

From 2000, another cooperative project spanning seven language communities, MIN (Modern Loanwords in the Languages of the Nordic Countries Project), aimed to investigate the actual use of loanwords and attitudes towards interference (see Kristiansen & Sandøy Reference Kristiansen and Sandøy2010 for details). This project focused mostly on inventory issues and quantification of use of Anglicisms in newspapers from the years 1975 and 2000 (Sandøy Reference Sandøy2009). The mention of the plural suffixes was rather sporadic and quite general in these studies.

More recently, Sunde (Reference Sunde2018) proposes a typology of Anglicisms in Norwegian that takes into account phraseological as well as structural borrowing, which hitherto ‘have received relatively little shcolarly attention’ (Sunde Reference Sunde2018:71; see also Sunde Reference Sunde2019). She bases her study on data retrieved from the Web, on the reasonable assumption that ‘features deviating from the normal language standard appears more frequently on the Web than in other corpora’ (Sunde Reference Sunde2018:83). Following Thomason & Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988), structural borrowing includes phonology, morphological and syntactic traits, and the plural -s is among the structural features that Sunde investigates (alongside the derivational -ish and presumably English-induced change in use of the domestic indefinite article and wh-clauses). In concordance with our own observations, she notes that nowadays ‘it is fairly common for direct English nouns to be inflected with the plural -s’ (Sunde Reference Sunde2018:102). Interestingly, she has also collected several examples which ‘indicate that the plural -s is tending to become productive for Norwegian nouns … that are not borrowed from English’ (Sunde Reference Sunde2018:102). She includes a set of ten lexemes that she has found at least three times on the web: nettbretts ‘tablets’, skjemas ‘forms’, temas ‘topics’, opphengs ‘hangups’, klikks ‘clicks’, klipps ‘clips’, videosnutts ‘video clips’, forums ‘forums’, muffins ‘muffins’ and datas ‘data’. We consider three of these, klipps, klikks and muffins, to be misplaced in this category because they must be regarded as Anglicisms (although the two first happen to have domestic homographs to their adapted orthographies): klikks in the exemplified sense of ‘instances of users following a web link’ is a semantic loan from English, as is klipps in the sense of ‘short online videos’, while muffins is straightforwardly a direct borrowing. As for the other forms, it is interesting to note that another three, temas, forums, and datas are from Latin/Greek. Sunde seems right in assuming that the motivation may be that speakers resort to an English inflection as an avoidance strategy amid uncertainty about the sometimes irregular inflections of such foreignisms. We also believe that her conclusion that ‘the English plural affix may indeed be catching on in Norwegian’ (Sunde Reference Sunde2018:103) may be right. However, to anticipate the discussion that follows, we have found no evidence to suggest that the plural -s with domestic stems has entered the realm of written texts outside the internet.Footnote 4 A notable exception to this are the informal -ings words like dritings ‘dead drunk’ etc. that we discuss in Section 1.2.2. Our own contribution here is meant to shed new light on the use of -s in non-possessive contexts based on two large corpora of texts that represent the standardised written norm, containing published texts from newspapers and books.

1.2 Overview of the use of non-possessive -s and historical inventory

1.2.1 Non-possessive -s with loanwords

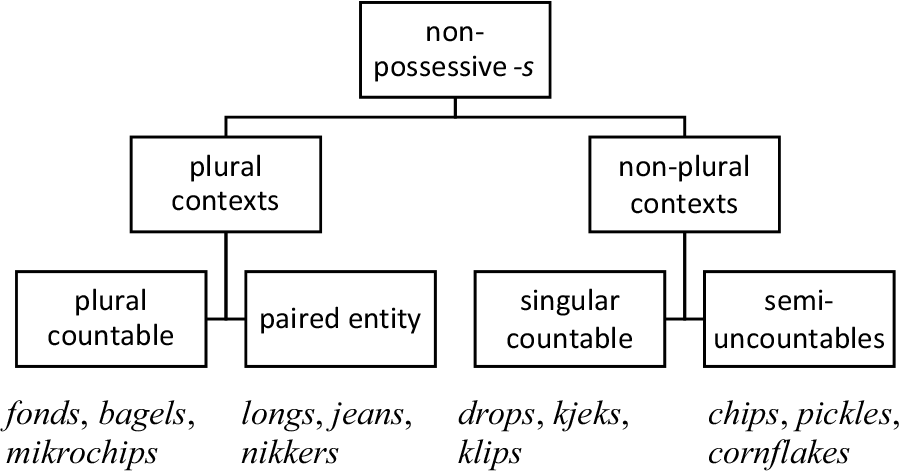

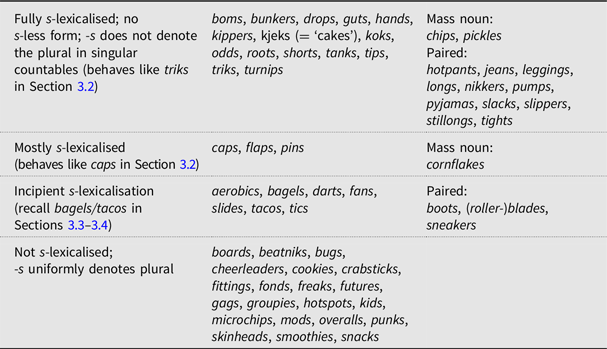

As will have become clear from the previous discussion, our notion of non-possessive -s captures two phenomena, a plural morpheme -s that occurs mostly with Anglicisms but occasionally also with domestic nouns, and a phonological segment /s/ which is no longer a plurality marker but has become the final part of a reanalysed nominal stem. It seems reasonable to categorise non-possessive -s according to two semantic criteria, namely whether it denotes plurality as well as the countability of the noun. This is illustrated and exemplified in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Use of non-possessive -s in Norwegian Anglicisms.

Non-possessive -s is used in both plural and non-plural contexts in Norwegian. The plural contexts include ordinary countable nouns such as fonds ‘securities’ and bagels. It should be pointed out that Figure 1 does not imply exclusivity of the listed forms; on the contrary, as observed in the literature review above, a neuter noun like [fond] vacillates in the plural between the -s plural and a regular and standardised domestic zero-plural in the indefinite, and a masculine noun like [mikrochip] can also have the domestic mikrochipper in the indefinite plural in addition to mikrochips.

The use of -s in the plural also includes a set of borrowed nouns whose etymons are pluralia tantum in English. These denote paired entities such as [jeans] and [nikkers] ‘knicker(bocker)s’ and make up a distinct category from the above in that only the countable nouns have singular forms like fond and bagel, but *jean and *nikker do not occur (in these senses). In terms of plurality, these nouns to some degree resemble their pluralia tantum etymons, in that they can trigger plural agreement with singular reference in contexts such as grønne longs ‘(a pair of) green longs’ and with the particularised form et par longs ‘a pair of longs’. But this usage co-occurs with quantification as regular countable nouns as in en longs ‘a pair of longs’ and to longser ‘two pairs of longs’ (see next paragraph). Similarly, jeans commonly triggers plural agreement with singular reference as in han var nemlig iført trange svarte jeans ‘he was in fact wearing tight, black jeans’ but also behave like ordinary countables as in en jeans ‘a pair of jeans’ and den hvite jeansen hennes ‘her white pair of jeans’. The variability of this group is evident even in long-standing Anglicisms like nikkers. Common to all of these forms is that s-less forms do not appear. The two usage types – as pluralia tantum or as regular countable noun – entail two different morphological structures. In the case of grønne longs the -s can be regarded as a suffix morpheme: [long]+[s]. As a countable noun, the -s has been reanalysed into a phonological segment that is part of the word’s stem [longs] and is thus similar to the group to which we now turn, the so-called klips nouns.

The non-plural contexts of -s include singular usage of countable nouns such as [drops] ‘candy’ and [klips] ‘clips’. For the words listed under this branch of Figure 1, we argue that the process of s-lexicalisation has come to completion. This is seen from the fact that they have no s-less forms as alternatives in the singular (*drop, *klip) but it is clear that -s is reduced to a stem-final phonological segment without plural denotation. The completion of this process is perhaps most readily observable in [kjeks], which has derived from English cakes and which has changed to such a degree that it is no longer perceived as an Anglicism by Norwegian speakers in general. In terms of inflection, some nouns of this class behave like regular domestic zero-plurals in the masculine (en kjeks ‘a biscuit’ – kjeksen ‘the biscuit’ – kjeks ‘biscuits’ – kjeksene ‘the biscuits’) or, more commonly, in the neuter (et drops ‘a piece of candy’ etc. – dropset – drops – dropsene), and some words can have either masculine or neuter inflection (e.g. drops and klips). Other s-lexicalised words take a regular plural ending -er in the indefinite, such as [pyjamas] (en pyjamas – pyjamasen – pyjamaser – pyjamasene). Yet other words allow both these plural inflections and are standardised accordingly; this applies for instance to [shorts] (en shorts – shortsen – shorts/shortser – shortsene). In other words, for a great many words that exhibit (early) signs of s-lexicalisation, there may be vacillation along several dimensions: between forms with or without the non-plural /s/ segment in the stem throughout the paradigm, between two different regular inflectional paradigms (zero-plural like kjeks or with suffix -er like pyjamas), and between a domestic or foreign realisation of the indefinite plural (with suffix -s as for fan, or with -er as for pyjamas). As a consequence, a word like [cap] could in theory be realised with the inflectional forms as seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Survey of possible realisations of morphological categories for [cap].

Most of the forms unequivocally show whether or not s-lexicalisation has occurred. The only exception is the form caps used in the indefinite plural, as there is no way of telling whether it represents a foreign plural -s appended to the stem [cap]+[s] or a case of a zero-plural of the s-lexicalised stem [caps]. (This has consequences for our quantitative analysis in Section 3, from which this realisation is discarded in the counts for indef.pl) As for the other plural variants, caper and capene are clearly not s-lexicalised, and we consider the form capser and capsene to be the result of s-lexicalisation thus: [caps]+[er] and [caps]+[ene], whose latter forms are regarded as unitary portmanteau morphs encoding both number and definiteness.

The final set of nouns with non-possessive -s in Figure 1 form a category that we have labelled ‘semi-uncountables’ for their ability to be used as uncountable mass nouns or occasionally with plural countable meaning. Like drops above, the members of this category have no -s-less forms and include [chips] in the sense of ‘potato snacks’ (note that in the sense of ‘computer chip’ this is a regular countable noun, as with mikrochip in Figure 1), [pickles] and [cornflakes]. Although Graedler (Reference Graedler1998:207ff.) describe these as uncountable nouns (alongside aerobics, fans and a few others), recent corpus findings make us somewhat reserved towards this label. While [chips] has a strong tendency to be used as an uncountable mass noun as in da blir chipsen sprø ‘then the chips (def.sg) gets crispy’, and å spise mye chips ‘to eat a lot of chips’, we also find tokens of definite plural chipsene with particularised reference, as in alle chipsene ‘all the chips’ (denoting individual chip entities, not brands of chips), de smakløse/salte chipsene ‘the tasteless/salty chips’, etc. Similarly, [pickles] generally denotes a mass in the singular, as in picklesen virket som en vietnamesisk variant ‘the pickles seemed like a Vietnamese variant’ and finhakket/hjemmelaget pickles ‘finely chopped/home-made pickles’. But there is also the occasional use with countable meaning in the indefinite plural, as in sursalte/smakfulle/søt-syrlige/hjemmelagde pickles ‘sour-salty/tasteful/sweet-sour/home-made pickles’. The same variability can be seen for [snacks], where contexts like annet/noe/mye/perfekt snacks ‘other/some/a lot of/perfect snacks’ generally give evidence of uncountable usage, while there are also occasionally countable plural contexts such as sunne/håndholdte/fargerike snacks ‘healthy/hand-held/colourful snacks’. Further evidence of occasional use with particularised reference are a few indefinite singular tokens of en snacks ‘a snack’ and en chips ‘a chip’. This discussion is meant to justify our label ‘semi-uncountable’ in Figure 1. Regardless of countability, the members of this category uniformly contain the segment /s/ as part of the stem, and we consider this to be another group where the process of s-lexicalisation has come to completion, as with drops above.

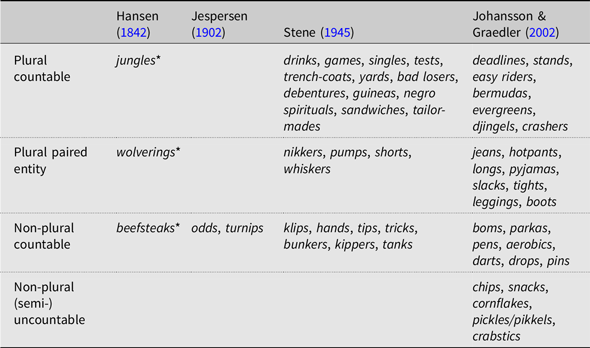

The categorisation in Figure 1 can be correlated with the literature survey in Section 1.1, and Table 3 gives an overview of forms cited in the most seminal previous studies on Norwegian and their lexical category.

The table reflects differences in size of inventory in these contributions, and it is interesting to see that the forms discussed by the oldest contribution, Hansen’s (Reference Hansen1842) foreign language dictionary, are now all obsolete. As seen from the more recent contributions, all four categories appear to be acquiring new members in modern Norwegian. In fact, a number of more recent Anglicisms could be added to this survey: bugs, fonds, tics, kids, smoothies and cookies are among the new members in the plural countable category, blades has emerged in the paired entity category, etc. (see Section 4, where the inventory of s-lexicalised forms is further documented and discussed).

1.2.2 Non-possessive -s with domestic stems

As has been documented previously (Graedler Reference Graedler1998, Johansson & Graedler Reference Johansson and Graedler2002), non-possessive -s is actually productive beyond Anglicisms, being used with a restricted set of domestic stems.Footnote 5 The most common type of usage is limited to the context of [stem]+[ing]+[s], where the -s cannot be interpreted as a plural marker but as part of a reanalysed stem; as in the expletive [fuck]+[ing]+[s] → [fuckings], thus parallelling the case of s-lexicalisation discussed above (Andersen Reference Andersen, Furiassi and Gottlieb2015). We have documented 42 types of such use of non-plural and non-possessive -s in the corpus data investigated, as seen in Table 4.

Table 3. Nouns with non-possessive -s in previous studies.

* Obsolete/no longer used in this sense.

Table 4. Colloquial -ings words found in the corpora.

These are mainly nominal, such as pulings ‘fucking’ (in a literal sense) and ordnings ‘order, clearing’, some are adjectival, such as dritings ‘dead drunk’, and a few are formulaic, such as the greeting mornings, short for ‘good morning’. They are all highly colloquial and not found in formal contexts. Another notable feature concerns their lexical tonemes, which makes this group distinct from their ordinary deverbal-noun ‘cousins’ with -ing, in that the former always have toneme 1, as in pulings and ordnings, while the latter always have toneme 2, as in puling ‘fucking’ and ordning ‘clearing’. This might suggest that speakers perceive of this former group as somehow unintegrated foreignisms in a way in which the latter group are not, as new loans tend to be realised as toneme 1.Footnote 6

In addition, there is the occasional and conventional use of -s with a plural meaning in band names such as Tre Busserulls, Vazelina Bilopphøggers and Ole Ivars, a usage also observed by Graedler (Reference Graedler1998) and Johansson & Graedler (Reference Johansson and Graedler2002).Footnote 7 As for the last one of these, it could be interpreted as a possessive -s in the sense of ‘Ole Ivar’s band’, but it is not. Rather, the name was modelled after the Swedish dance band Sven-Ingvars, which is clearly plural in that it signifies ‘two times Sven and an Ingvar’.Footnote 8

The above examples are drawn from stylistically restricted contexts, most notably slang usage. This raises the question whether non-possessive -s is generally productive beyond such restricted contexts and whether it has permeated the language of most speakers and is gaining foothold in the language more generally. We believe this not to be the case. As we pointed out in the literature review (Section 1.1), Sunde (Reference Sunde2018) reported seven cases (and three where it attached to English-based stems), of which three were Greek/Latin-based stems. Having looked up all of Sunde’s (Reference Sunde2018) cases of domestic stem + plural -s in the large corpora investigated here (see Section 2), we have found no evidence that non-possessive -s is productive as a plural marker of domestic words in written texts outside the internet.

2. Material used in the case studies

While earlier accounts of Anglicisms such as Stene (Reference Stene1945), Graedler (Reference Graedler1998) and Johansson & Graedler (Reference Johansson and Graedler2002) relied on manual methods or relatively limited corpora for documenting their usage, we are in a position to use large computational resources for this purpose. The use of Anglicisms in contemporary Norwegian is documented in the Norwegian Newspaper Corpus (Andersen & Hofland Reference Andersen and Hofland2012) (henceforth NNC). The NNC is a large dynamic corpus of Bokmål and Nynorsk containing roughly 1.5 billion running words. The texts have been retrieved from the web edition of 24 national, regional and local newspapers covering the period from 1998 to 2013.

Earlier usage of Anglicisms is documented by the resource Bokhylla.no, which is the searchable digital text archive of the National Library of Norway (Nationalbiblioteket, henceforth NB). This is a massive collection that includes all books published in Norway until 2000 and a wide selection of newspapers from 1763 until the present time, periodicals and other text types. Being a text archive rather than a dynamic corpus, this resource is well-suited for documentation of historical usage, but its current interface is less flexible for the documentation of frequency statistics and variation.Footnote 9

3. Case studies

In order to shed light on various usage types of non-possessive -s, we now present four case studies of Anglicisms which date from different periods of borrowing from English into Norwegian. These are the lexemes [trick] (first documented c. 1860), [cap] (c. 1930), [taco] (c. 1950) and [bagel] (c. 1970). For each item, we assess the degree of s-lexicalisation and variation between domestic and foreign suffix for each form in the inflectional paradigm.

3.1 The Anglicism [trick]

The first case study concerns the noun trick, which is among the oldest Anglicisms in modern Norwegian. The earliest documentation was found in a newspaper from 1862 (there were actually even earlier findings, but they were instances of code-switching into English and not categorised as loanwords into Norwegian). As shown in example (1) below, trick, as part of a compound noun, is used with quotation marks and hence still appears to be related to English as a foreign language, but it was already partially integrated and had been assigned with neutral gender (seen in the neuter determiner det ‘the’).Footnote 10

(1) Et af de mest indbringende Krigspuds er det saakaldte ,,Kvæling-Trick”.

(NB AB 1862-02-25)‘One of the most lucrative war pranks is the so-called “choking trick”.’

The same source, the newspaper NB contains another article with the same noun 24 years later, seen in (2).

(2) … for at more vor ledige Nysgjerrighed, eller endog for at gjøre ,,Tricks”.

(NB AP 1886-09-16)‘in order to amuse our open curiosity, or even to do “tricks”.’

Here it is still printed with quotation marks, and also used with an English plural ending.

However, it was not until the early part of the 20th century that instances of Norwegian plural suffixes were found in the NB data, as with the definite plural suffix -ene in (3).

(3) Alle manererne var der. … Hele «opfatningen», alle trickene.

(NB AP 1913-02-16)‘All the manners were there. The entire “perception”, all the tricks.’

During the same period, s-lexicalisation appeared in both singular nouns, as in (4), and in the plural definite, as in a book about sports, in (5).

(4) … altsaa var dette her et triks av min bror for at gjengjælde det før omtalte …

(NB B-D 1912-08-30)‘so this was a trick by my brother in order to return the previously mentioned’(5) Det er ogsaa et av triksene som kun læres ved lang øvelse

(Kristiania Kredsforbund for Idræt. 1918. Trænings-boken: veiledning for nybegyndere i: boksning, brytning, cykling, fotball, fri idræt, roning, skiløpning, skøiteløpning, svømning. Kristiania: Aschehoug. Page 61)‘That is also one of the tricks that one can only learn by long-time practice’

At that time orthographic adaptation also occurred – in (4) and (5) the representation of /k/ in trick has been conventionally changed from <ck> to <k>, suggesting that all three processes of adaptation – spelling, suffixation and s-lexicalisation – are related and concurrent. By the late 20th century, the Anglicism triks has aquired a more general meaning than the earliest examples suggest, and it has become fully morphologically integrated, and even converted into a verb (trikse ‘play a trick’). Figure 2 shows a graph for each occurring form of the noun in the NB’s n-gram viewer.Footnote 11

Figure 2. Frequency of occurrence of [trick/triks].

Two main observations can be drawn from this data. First, the unadapted forms containing <ck> are on the decrease and have all but died out, with the exception of the forms trick/tricks. The resilience of these forms is not due not to [trick] alone but must be ascribed to a set of imported phrasal compounds, namely [basic/mind/dick/dirty/hat trick]. Of these, hat trick is even standardised with this unadapted spelling. It is clear from available statistics that especially in the singular the unadapted form hat trick forms a very strong collocation. Second, and most importantly for our current research objective, the forms with -s as part of the stem (both in singular and plural) have gradually become more frequent than the stem without the -s, as seen unambiguously from the surge of trikset and triksene (second and third most frequent in 2013).

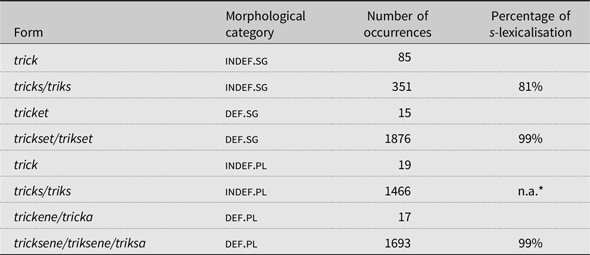

Let us look into data that show this tendency more conspicuously. The figures in Table 5 give the statistics from the NNC data, which show that -s has become a permanent part of the word stem, i.e. s-lexicalisation is close to 100 per cent. The tabular data corroborates what was shown in Figure 2 in that the indefinite singular trick/tricks has a lower degree of s-lexialisation, with roughly 81 per cent. As mentioned, this can largely be attributed to compound contexts with hat trick and other forms imported ‘wholesale’ as phrases. These are semantically distinct from [trick] itself, as they denote more specific concepts (e.g. freestyle skiing tricks, etc.). As mentioned in Section 1.2.1, the indefinite plural cannot be trusted as an indicator of s-lexicalisation, since we cannot know whether the form tricks/triks represents an s-plural of [trick] or a zero-plural of [tricks/triks]. Hence, no percentage is shown for this category in Table 5, but it can nevertheless be observed that the -s form dominates here also (99%).

Table 5. Distribution of inflectional forms of [trick/triks] (including hat trick, etc.).

* See the main text for discussion.

3.2 The Anglicism [cap]

The next Anglicism, [cap], was found in a newspaper from 1930, even though it was not included in Stene’s (Reference Stene1945) list of English loanwords from the late 1930s (again, there were earlier findings, but they were part of English phrases and not categorised as a Norwegian loanword). Just like the earliest instance of trick in example (1) above, cap in (6) is part of a compound, here with -s as a plural ending; hence the noun had not been integrated into the Norwegian system yet.

(6) … at personer som bærer de saakaldte «skull caps», ikke løper noen stor risiko …

(NB SSD 1930.08.12)‘that persons who wear the so-called “skull caps” do not risk any danger’

Just like in the previous case, [trick], most of the occurrences of [cap] come quite a bit later, as shown in Figure 3.Footnote 12

Figure 3. Frequency of occurrence of [cap].

The figure shows that, unlike [trick], the unadapted forms have not given way to the adapted ones for any part of the paradigm (caps > kaps, capsen > kapsen, etc. for the whole paradigm and the whole period). This is counter to the prescriptive norm, which, since 1996, only allows the adapted form [kaps]. We also note that the s-less forms are outnumbered by their s-lexicalised equivalents, which can be seen unambiguously for the definite singular capsen/kapsen > capen/kapen, the indefinite plural capser > caper (no adapted forms) and the definite plural capsene (no unadapted or s-less form).

More consipucous data for this relation can be found in Table 6. Here the token frequencies for each morphological category are based on the NNC data. It shows that singular forms are much more common than plural forms; hence most occurrences of the lexeme are realised by caps and also the definite singular form capsen in the newspaper corpus (especially common in journalistic accounts of crime suspects as in en raner påkledt caps og regnjakke ‘a robber wearing a cap and a raincoat’). Table 6 also reveals that the s-lexicalisation has reached a high percentage for this lexeme, close to or above 90 per cent for all morphological categories. The indefinite plural realisation caps is technically not identifiable as either s-lexicalised or non-s-lexicalised, since it could be analysed either as an s-lexicalised realisation [caps]+[Ø], with a null plural suffix, or as a non-s-lexicalised form [cap]+[s], with an s-plural suffix. Hence, this realisation is discarded from the percentage counts, which can still be calculated on the basis of the -er-suffixed forms. We note that cap coexists in this variety with caps/kaps in the indefinite singular. A word of caution is called for regarding the other morphological categories. The unadapted s-less forms capen/caper/capene (marked with * in Table 6) are homonymous with another and much older Anglicism, cape and it may be difficult to determine the intended sense of the word in some contexts (e.g. Vesker, korsetter, sko, caper ‘bags, corsets, shoes, capes/caps (?)’).

Table 6. Distribution of inflectional forms of [cap].

* See the main text for discussion about the cap/cape ambiguity in these forms.

** In this and the following two tables, brackets are used to indicate that an indefinite plural realisation such as caps is not identifiable as either s-lexicalised or non-s-lexicalised, since it could be analysed either as an s-lexicalised realisation [caps]+[Ø], with a null plural suffix, or as a non-s-lexicalised form [cap]+[s], with an s-plural suffix. Hence, these tokens are excluded from the percentage calculation.

Examples (7)–(10) below illustrate s-lexicalisation occurring in the different morphological categories, both singular and plural definite and indefinite forms.

(7) Han hadde en caps på hue, og var nybarbert på overleppa.

(Jon Michelet, Hvit som snø. Oslo: Gyldendal norsk forlag (1980). Page 181)‘He wore a cap on his head, and was freshly shaved on his upper lip.’(8) Semb har den etter hvert karakteristiske capsen på hodet sitt.

(NNC VG 1998-08-20)‘Semb has the by now characteristic cap on his head.’(9) … fargerike T-skjorter for alle anledninger, gensere, capser, slips og skjerf.

(NNC AA 1999-09-28)‘colourful T-shirts for all occasions, sweaters, caps, ties and scarves.’(10) Guttene … dro capsene og luene godt ned i øynene

(NNC AP 2005-12-01)‘The boys pulled the caps and the hats well over their eyes.’

In sum, unlike [trick], [cap] still appears as a foreignism in the newspaper corpus because of its unadapted orthography containing the ‘non-Norwegian’ letter <c> and its pronunciation /kæp/. However, generally speaking, the -s has become reanalysed as part of the stem in Norwegian, albeit coexistent with s-less forms throughout the paradigm.

3.3 The Anglicism [taco]

Although originally of Spanish origin, taco is nevertheless considered an Anglicism, as it is likely to have emerged in Norwegian via English, thus following the path of other gastronomic words like hamburger, etc. which represent concepts adopted in the anglophone sphere before making their way into the Norwegian culture. The earliest documentation of the word in written Norwegian dates from 1949, in the translated novel Stekt høne hver søndag (Chicken every Sunday), written by Rosemary Taylor and set in Arizona.

Although scarce in its early decades, the NB data show a strong growth after 1980, when tacos became a regular dish in Norwegian homes, as seen in Figure 4. [taco] does not appear with adapted orthography. Note also that only a limited set of paradigmatic forms has emerged in the data contained in NB’s n-gram viewer; for instance, there are no tokens of indefinite plural tacoer, while tacos occurs. Compare this to the token frequencies of occurrence in NNC of the various paradigmatic forms in NNC in Table 7.

Figure 4. Frequency of occurrence of [taco].

Table 7. Distribution of inflectional forms of [taco].

It is clear from the NNC data that [taco] has only been partially adapted to Norwegian inflectional morphology, in that the -s plural tacos is clearly dominating for the indefinite plural, despite tacoer being the standardised inflection of the Bokmålsordboka dictionary. Relevant examples are shown in (11)–(12).

(11) Når du skal invitere venner til middag, er det mye flottere å kunne servere fantasifulle burgere enn for eksempel tacos.

(NNC FV 1998-10-16)‘When you are inviting friends for dinner, it is much nicer to serve fanciful burgers than tacos for example.’(12) Du trenger verken kniv eller gaffel for å gå løs på ekte tacoer i Mexico – det ser bare fryktelig dumt ut.

(NNC DA 2012-09-21)‘You need neither knife nor fork in order to attack (lit.) real tacos in Mexico – that just looks really stupid.’

On the other hand, the definite singular and plural are regularly formed according to Norwegian morhpology, as seen in (13)–(14).

(13) Og derfor synes de tacoen som moren lager, er bedre.

(NNC AP 2006-03-11)‘And therefore they think that the taco that their mother makes is better.’(14) Men tacoene var faktisk gode, og jeg ble god og mett, sier han.

(NNC DB 2000-06-03)‘But the tacos were actually good, and I became good and full (lit.), he says.’

Note that the token frequencies for the definite plural are very low and therefore unreliable. One token, tacosene ‘the tacos’ in (15), may be taken as a sign that s-lexicalisation is emergent.

(15) Hit må vi tilbake. Men tacosene er litt høyt priset.

(NNC DB 2013-12-01)‘We must come back here. But the tacos are a little highly priced.’

In other words, there are only very weak (or early) signs of reanalysis of -s from plural suffix into a stem constituent, restricted to the definite plural and with only one occurrence in the large newspaper corpus. This one token could be interpreted as idiosyncratic or even a spelling error; hence we are reluctant to conclude that this lexeme is undergoing s-lexicalisation.

3.4 The Anglicism [bagel]

The Anglicism bagel is of even more recent date. Its first documentation in NB is from the translated book Amerika – De forente staters historie (Alistair Cooke’s America), published in 1973, where the concept of a bagel is explained as de smultringformede kakene som kalles bagels ‘those doughnut-shaped cakes called bagels’ (page 274). Again, we are dealing with a word that has previously been borrowed into English, in this case from Yiddish.

The frequency graph from NB, seen in Figure 5, shows not a linear growth of the lexeme, but a moderate dip in the 1990s followed by considerable growth up to the early 2000s and subsequent decline/stabilisation.

Figure 5. Frequency of occurrence of [bagel].

The figure contains a graph for the uninflected adapted form beigel, but this must be interpreted with some degree of caution. First, most of the tokens represent the homographic surname Beigel, but the n-gram interface would not allow us to set the search criterion to case-sensitive and still retrieve relevant tokens of this form. Second, the text archive does contain some tokens of beigel but we are hesitant to conclude that they represent cases of spelling adaptation of an English etymon:

(16) og ville han ofre sin siste kopek kunne han kankskje få en beigel også.

(Eva NB Scheer, Tre er fedrene, fire mødrene. Oslo: Aschehoug (1981))‘and if he would sacrifice his last kopek, he could perhaps get a bagel also.’

The tokens of beigel are set in literate contexts depicting Jewish culture mostly in central Europe. We thus consider them not to be spelling adaptations of an English lexeme, but of its Yiddish source with the original spelling beygel (OED online: bagel). Figure 5 also contains the form bagelsene, suggesting incipient s-lexicalisation, but this is relatively infrequent and only for a very short period of 2003–2008.

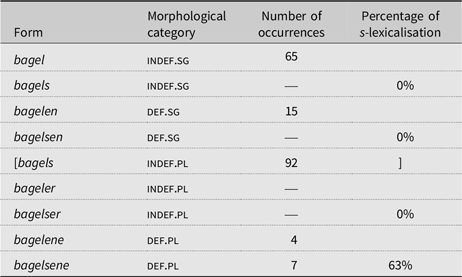

Table 8 gives the token frequencies according to morphological category and (17)–(20) contain illustrative examples.

(17) Colaen var god og kald, men bagelen var hard og vanskelig å tygge.

(NNC AP 2007-04-26)‘The Coca Cola was nice and cold, but the bagel was hard and difficult to chew.’(18) Sandwicher og bagels kan ikke ligge lenger enn 48 timer hos 7-Eleven før maten blir for gammel til å selges.

(NNC DN 2004-07-22)‘Sandwiches and bagels cannot stay more than 48 hours at 7-Eleven before the food is too old to be sold.’(19) Pass på at bagelene ikke ligger inntil hverandre under kokingen

(NNC DN 2014-12-04)‘Make sure that the bagels are not placed too closely during cooking’(20) Når alle bagelsene er kokt og dekket med frø setter du dem i ovnen og baker i 5 minutter.

(NNC DB 2011-05-01)‘When all the bagels have been cooked and covered with seeds, place them in the oven and bake for five minutes.’

Table 8. Distribution of inflectional forms of [bagel].

It is clear from the NNC data that [bagel] has only been partially adapted to Norwegian inflectional morphology, in that the -s plural bagels is used invariably to denote the indefinite plural. In other respects, the lexeme follows regular Norwegian morphology, although there are signs of s-lexicalisation in the definite plural.Footnote 13 The seven tokens of bagelsene outnumber the s-less form, with 63 per cent. However, the overall number of tokens for this category is small and the result must be interpreted with caution.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The preceding four cases – [trick] (1862), [cap] (1930), [taco] (1949) and [bagel] (1973) – can stand as representatives of different stages of lexical borrowing, from well-established to more recent or incipient. We have seen that these lexemes differ in the extent to which non-possessive -s has been integrated into the stem (s-lexicalisation). The oldest lexeme [trick] is fully s-lexicalised across all morphological categories (but note the exception for recently borrowed compounds such as hat trick). For the second oldest lexeme, [cap], the ratio of s-lexicalisation is close to 90 per cent for the lexeme as a whole, but despite its age, the variability in presence vs. absence of -s is observed in all morphological categories. The indefinite plural realisation caps is technically not identifiable as either s-lexicalised or non-s-lexicalised, since it could be analysed either as an s-lexicalised realisation [caps]+[Ø], with a zero plural suffix, or as a non-s-lexicalised form [cap]+[s], with an s-plural suffix. If we set aside this realisation of the indefinite plural, the ratio of s-lexicalisation is close to 90 per cent and it is equally distributed across the paradigm (see Table 6 above).

The two most recent cases of s-lexicalisation in [taco] and [bagel] can at best be characterised as incipient. For [taco] the ratio of s-lexicalisation is close to zero, and only observable in the definite plural tacosene with one token, which amounts to 20 per cent for this morphological category. For [bagel] the ratio of s-lexicalisation is also close to zero if we consider the lexeme as a whole (3.8%), but the definite plural category has a remarkably high ratio of s-lexicalisation at 63% (although the numbers are small; n = 11; see Table 8). These observations lead to some hypotheses that might be explored in future research: that s-lexicalisation is never categorical in newly borrowed lexemes, although it may become categorical with time, as seen from cases such as [kjeks] and [triks], and that s-lexicalisation emerges gradually and spreads from one morphological category to other parts of the paradigm. It would seem from our observations about [taco] and [bagel], that the definite plural provides the most fertile ground for early s-lexicalisation, before it becomes realised in other morphological categories. However, it is too early to say whether s-lexicalisation will prevail for these two most recent lexemes.

Another point of comparison for the case studies concerns orthography, to which we have devoted less attention. It was shown that [triks] categorically has an adapted orthography, while [caps] has generally retained its original orthography with <c> despite official standardisation prescribing only the adapted form with <k> since 1996. The two most recent lexemes have not been orthographically adapted. This corroborates the findings from an earlier study which found that official standardisation often does not have the normative effect intended by the standardisation authority (Andersen Reference Andersen2012a).

A general testable hypothesis that can be drawn from the four case studies in Section 3 is the following: the longer an Anglicism has existed in Norwegian, the higher the chance of s-lexicalisation. This comes as part of a more general process of adaptation through which borrowed forms lose their status as Anglicisms, as in the case of kjeks, for example, which only etymologically-oriented researchers would perceive as being connected with an originally plural English form cakes. The data investigated also suggest a systematicity of reanalysis, since incipient s-lexicalisation seems to gain foothold in the definite plural context before other paradigmatic contexts (supported also by the NB data for bagel; see Figure 5 above). In the remaining part of this section we explore this and other tendencies regarding incipient s-lexicalisation for the purpose of formulating hypotheses that may be tested in the future.

The observations from our case studies raise questions about the generalisability of our findings thus far and of possible factors that may influence the degree of s-lexicalisation. In order to shed more light on the issue, we investigated a set of 70 Anglicisms that together make up the accumulated inventory of relevant forms of the above-mentioned studies (see Sections 1.1–1.2), supplied with some more recent words like tics. Of these, a few had to be set aside since they are now in effect obsolete or non-occurring in the sense reported in the literature (e.g. beefsteak, whisker). The method involved charting the token frequencies in the NNC for the paradigmatic forms with or without -s, restricting the corpus search to lower-case realisations where relevant, in order to avoid a number of tokens that were part of proper nouns (such as The Mods). A summary of the forms investigated is shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Documentation of s-lexicalisation in the Norwegian Newspaper Corpus.

A great many words have different meanings or belong to different lexemes in the -s vs. s-less forms. For instance, tank is a container while tanks is a vehicle, tight occurs only as an adjective while the noun tights refers to a garment, slack may be an adjective or a noun but is certainly a different lexeme than the garment slacks, etc. For such words, the homography is effectively barring the possibility of an s-less form denoting the singular, so tank could not be taken to mean the singular of tanks, which, by virtue of being fully s-lexicalised, can have singular or plural reference.

An observable pattern that emerges from this exploration is that words that become s-lexicalised tend to be monosyllabic. In this category we find boms, drops, guts, etc. Setting aside mass and paired nouns, altogether 12 of the 15 fully s-lexicalised words are monosyllabic. Conversely, the words in the non-s-lexicalised category are mostly polysyllabic; here we find 17 polysyllabic words out of 20. Previous research has shown that length in syllables has a bearing on plural formation and gender assignment (Graedler Reference Graedler1998:158ff.; Onysko Reference Onysko2007:154ff.), and it has been shown that monosyllabic words are generally more fully integrated morphologically than are polysyllabic words (Graedler Reference Graedler1998). However, the interplay of number of syllables and degree of s-lexicalisation of Anglicisms has not been explored in previous research, to our knowledge. Future research should be aimed at testing whether monosyllabicity is a reliable predictor for s-lexicalisation in Norwegian.

There is also the possibility that segmental phonetic effects could be at play. One such effect that might be read out of Table 9 is that consonant-final stems may favour s-lexicalisation more than vowel-final stems. Although the data are only indicative on this point, we observe that consonant-finality characterises all the words in the fully s-lexicalised category, again, setting aside mass and paired nouns. Conversely, all words with a stem that ends in the vocalic pattern -ie /i/ (cookie, groupie, smoothie) are categorically non-s-lexicalised. Another observation is that as many as 12 of the 15 s-lexicalised words end in voiced or voiceless stops (drops, guts, etc.). This seems to underscore Graedler’s (Reference Graedler1998) suggestion that ‘the phonological and orthographic shape of a borrowed element are factors relevant to its integration’. As indicated above, previous literature has suggested that phonological factors may have an effect on gender assignment (Onysko Reference Onysko2007:154ff.). For Norwegian, Haugen (Reference Haugen1953/1969:444) observes that borrowed nouns tend to be assigned the same gender as phonologically similar but otherwise unrelated groups of words in the recipient language (see also Graedler Reference Graedler1998:163f.). Assuming that such a ‘principle of phonological shape’ (ibid.) may be in effect, it is possible that a similar analogy may be affecting the reanalysis of -s from plural suffix to stem-final segment. Considering the two phonological factors of number of syllables and consonant-finality in combination, we arrive at the possible hypothesis that s-lexicalisation tends to be favoured in phonological contexts where a preexisting class of similar words exists. Thus, the reanalysis of kjeks, koks, tics and triks could be explained by the existence in the recipient language of a phonological category that already contains aks ‘straw’, boks ‘box’, saks ‘scissors’, voks ‘wax’, etc., the reanalysis of chips, drops and tips could be explained by a phonological category that already contains gips, korps, kreps, raps, veps, and so on. Although it would seem easy for language users to assign new members to such phonological categories, we agree with Graedler (1988:164) that it would be ‘notoriously difficult’ to find an empirically sound way of testing such a hypothesis, both since it would be problematic to operationalise these categories of near-rhyming forms, and since the cognitive salience of the categories and their individual members presumably varies considerably across speakers and speaker groups. Nevertheless, we conclude that consonant-finality of the stem may be a relevant phonetic predictor for s-lexicalisation that should be tested in future research.

If we consider the groups of mass nouns and paired nouns in Table 9, it becomes apparent that it is not their phonological but their semantic properties that unite them. The mass noun category contains three members that are phonologically heterogeneous but semantically homogenous, namely chips, pickles and cornflakes, all denoting masses of multiple small edible items. The mechanism for their s-lexicalisation (only partial with cornflakes according to our corpus data) seems to be a semantic reanalysis by which a source language plural form denoting multiple small entities becomes construed as a mass in the recipient language. In this process the possibility of particularisation by means of singular forms chip, pickle and cornflake appears to be lost in the process. The particularised concept is presumably experienced by speakers of the recipient language as less cognitively salient, usage-relevant or communicatively needed than the mass noun interpretation of the lexeme. Hence, the latter stands a much better chance of surviving in the long term, with the consequence that the segment -s loses its relevance as a plurality marker.

Further, we observe that the paired entities categorically denote different types of wearables. Most of these have no s-less forms and are s-lexicalised, but they can trigger singular agreement (e.g. hotpantsen er tilbake ‘the hotpants (lit.) is back’) or plural agreement with reference to a singular pair (e.g. for mindre viktige ting enn de hotpantsene ‘for less important things than those hotpants’). It is possible that this usage also represents a type of semantic reanalysis akin to the one affecting mass nouns, in that what is originally a plural entity with two parts – the legs of trousers or shoes of shoe pairs – gradually becomes construed as a singular entity. An interesting difference emerges between the fully s-lexicalised lexemes and the non-fully s-lexicalised ones, in that the former are all different types of trousers, while the latter are all different types of footwear, namely boots, (roller-)blades and sneakers, where particularisation is conceivable in a way which it is not possible for the legs of trousers.

This latter group is interesting for other reasons as well, namely their recent date and incipient s-lexicalisation. Remarkably, for two of the members in this group, s-lexicalisation can only be observed in the definite plural forms bladesene (one token in NNC) and sneakersene/sneakers’ene (eight and two tokens, respectively). For the third member, it is mostly observed in the definite plural forms bootsene/bootsa (33 and 10 tokens), but also in the definite singular form bootsen (seven tokens). For none of the members in this group do we find evidence of s-lexicalisation in the indefinite plural, which is always realised with plural -s as in English; i.e. *bootser/(roller)*bladeser/*sneakerser do not occur. Nor do we find s-lexicalisation in the indefinite singular (*en boots/*en (roller)blades/*en sneakers), but they quantify regularly as countable nouns as in selger snart sin siste sneaker ‘soon selling their last sneaker’. This corroborates our findings from the case studies above, in that the definite plural seems to provide the most fertile ground for the s-lexicalisation reanalysis. In fact, the data lends itself to further interpretation, and we should like to postulate the following implicational scale for the morphological contexts in which s-lexicalisation can emerge, with reference to the degree of s-lexicalisation observed in the case studies and the data reported in this section:

definite plural > definite singular > indefinite singular and plural

The implication of this scale is that words that s-lexicalise in the indefinite contexts by necessity also do so in the definite contexts, and words that s-lexicalise in the definite singular also do so in the definite plural. Support for this hypothesis can be found in the paradigmatic realisation of other lexemes where s-lexicalisation is incipient, beyond what was said about tacos and bagels in Sections 3.3–3.4. For instance, s-lexicalisation can only be observed in the definite plural slidesene/slides’ene (one token each, no tokens of *slidene), while slide otherwise inflects as a regular noun in the singular with slides being used uniformly to denote the indefinite plural (in accordance with the standardised inflection prescribed in the Bokmålsordboka dictionary). Partial support is found in the corpus data for tics, where again the definite plural ticsene/tics-ene (six and five tokens) is categorically s-lexicalised (no tokens of *ticene). Here the indefinite singular is realised as tic with five tokens and in one instance as tics (et tics kan kanskje sammenlignes med et nys ‘a tic can perhaps be compared with a sneeze’). As there are no tokens of the definite singular with either of the forms ticset/ticet, we cannot be conclusive as to whether s-lexicalisation of the definite singluar precedes the indefinite forms for this lexeme. The next member of this category, fans, is a special case which generally supports our proposed implicational scale. The s-lexicalised form fansene is categorically used in the definite plural (in writing its non-lexical counterpart fanene would be homographical with the def.pl of another lexeme, fane ‘banner’, which presumably works as a counterforce in this case). The word behaves idiosyncratically because the morphologically definite singular form fansen is used overwhelmingly with plural reference to a group of fans (Faarlund, Lie & Vannebo Reference Faarlund, Lie and Vannebo1997:139), as in prøvde å roe ned fansen ‘tried to calm the fans’, unlike any of the other Anglicisms considered in this paper. This use as a collective noun mirrors the semantic change into mass noun that the edibles like chips, pickles, etc. are undergoing, but we cannot rule out its potential use with a singular reference, although no tokens were found, and fan on the whole retains its properties as a countable noun. At any rate, the paradigmatic form fansen is categorically s-lexicalised (fanen would again be homographic with def.pl of fane ‘banner’). We still consider s-lexicalisation to be only incipient for this item, since the indefinite singular is mostly realised as fan, although we also observe s-lexicalisation in this context, as in en stor/kvinnelig/ihuga fans ‘a big/female/die-hard fan’ and since it is the s-less form that is the basis for compounding (e.g. fanbrev ‘fan letter’), unike a fully lexicalised item like guts (gutsjente ‘guts girl’). As for the indefinite plural, it is always realised as fans, and *fanser does not occur.Footnote 14 We find altogether 25 tokens of the s-lexicalised indefinite singular en fans in the corpus, but no tokens of the s-lexicalised indefinite plural fanser. If we take this evidence to be more generally indicative of the degree to which words get s-lexicalised in the indefinite, it would suggest that the penultimate morphosyntactic context to trigger s-lexicalisation is the indefinite singular, while the final and least likely context to do so is the indefinite plural. Thus, the implicational scale proposed above can be modified as follows:

definite plural > definite singular > indefinite singular > indefinite plural

fans+ene > fans+en > en fans > fans+er

There is a plausible explanation for why precisely the indefinite plural should be the last context to trigger s-lexicalisation, namely the salience of the form fans which follows the imported pattern [stem]+[s]. As we saw in the case studies, this structure is massively recurrent in the corpus for words with incipient or more advanced s-lexicalisation, and language users do not ‘need’ to construct a new plural form by adding the suffix -er since a fully functional alternative has already been imported wholesale and adopted with the plural meaning.

We have not yet commented on the last two members of the class of words with incipient s-lexicalisation in Table 9, namely darts and aerobics. Darts does not occur with inflectional forms in the corpus, but it is nevertheless interesting as an illustration. Despite its standardisation as an s-less form throughout the paradigm (en dart – darten – darter – dartene), it is occasionally used with the -s form darts in eight instances in the corpus (outnumbered by 113 s-less tokens). We have no reason to think that Norwegian users perceive this as a plural form of dart; it is clear from the context that the reference is categorically to the game (det føles litt som å spille darts ‘it feels a bit like playing darts’), i.e. the same singular concept as the standardised form. Thus, we consider this to be a case of incipient s-lexcialisation. As for aerobics, it behaves in the same way; some tokens of the uninflected aerobics are outnumbered by a standardised s-less form aerobic. Although seemingly counterexamples to our conjectured trajectory, these lexemes do not disprove it. The reason is that nouns denoting games and sports, such as darts ‘darts’, sjakk ‘checkers’, fotball ‘football’, etc., behave morphosyntactically as mass nouns in Norwegian and cannot take the indefinite article (unless fotball refers to the ball, not the game), e.g. spille *en sjakk ‘play *a checkers’; although plural forms sjakker/sjakkene have been standardised, these are merely theoretical constructs that do not occur in actual usage.

We should also, in conclusion, point out that the term ‘incipient s-lexicalisation’ may misleadingly suggest that all lexemes characterised as such eventually become fully s-lexicalised. We do not think that this is the case. In fact, darts is a good example of a word where reanalysis of -s into the stem occurs only sporadically and where we would not predict that this form prevails in the longer term.

In this discussion we have pointed out phonological and morphological factors that may seem to shape the ways in which Anglicisms become s-lexicalised – monosyllabicity and consonant-finality of the stem, definite forms before indefinites, etc. Of course, there are also usage-related factors that may have significant effects. Judging by the four case studies, the date of entry seems to have a clear bearing on reanalysis, in that older Anglicisms are more likely candidates for s-lexicalisation than newly adopted ones. It also seems reasonable to conjecture that the reanalysis could be an effect of increased usage in the short term, so that more frequent Anglicisms are more likely candidates than than rare ones. Relatedly, it would seem likely that Anglicisms that belong to general domains are more likely candidates for s-lexicalisation than those that belong to specialised domains, such as finance (e.g. fonds and futures, both financial instruments, in Table 9).

Another factor to be considered is the effect of increased knowledge of English in the population. Since all Norwegian speakers of English at some level ‘know’ that the logically ‘correct’ form to use in the singular should be one that does not contain any segmental /s/, we might assume that s-lexicalisation would gradually become a thing of the past and that the increased competency would eventually make this reanalysis an obsolescent phenomenon. However, we do not wish to speculate to that effect. On the contrary, we regard s-lexicalisation as a fairly productive process in the adaptation of modern-day Norwegian Anglicisms. We hear young and highly English-competent speakers say things like doodlesen ‘the doodle’ even with ‘brand new’ Anglicisms.

In summary, this article has had a hypothesis-generating rather than a hypothesis-testing objective. The case studies and the survey of a set of forms presented have shown that phonological, morphosyntactic and usage-related factors may influence the degree to which and the manner in which the English plural suffix -s is reanalysed into word stems, not just in nouns but also in the -ings words surveyed in Section 2. In general terms, our study has also shown that the plural -s is thriving in Norwegian contexts, even in some words that are not of English origin.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the three anonymous NJL reviewers and to editor Gunnar Ólafur Hansson for their valuable comments on the first version of this article.

Appendix. Newspaper sources

Abbreviations of newspaper titles used in example-source annotations in the text. The newspapers were drawn from the National Library of Norway and the Norwegian Newspaper Corpus.

AA = Adresseavisen

AB = Aftenbladet

AP = Aftenposten

B-D = Bratsberg-Demokraten

DA = Dagsavisen

DB = Dagbladet

DN = Dagens Næringsliv

FV = Fædrelandsvennen

SSD = Smaalenenes Social-Demokrat

VG = Verdens Gang