1. Introduction

The intersubjective and rhetorical aspects of evidentiality and epistemic modality is an increasingly important area in functional linguistics (e.g. Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003, White Reference White2003, Simon-Vandenbergen & Aijmer Reference Simon-Vandenbergen and Aijmer2007, Stivers Reference Stivers, Tanya, Lorenza and Jakob2011, Hanks Reference Hanks2012, Heritage Reference Heritage2012, Marín Arrese Reference Marín, Juana, Marín Arrese, Marta, Jorge Arus and Johan2013, Cornillie & Gras Reference Cornillie and Gras2015, Foolen, de Hoop & Mulder Reference Foolen, de Hoop and Mulder2018). At the core of epistemic modality is an estimation of the reliability of what is said. Evidentiality pertains to one’s access to information, and the link between the information source and the utterance is somehow displayed and made relevant. However, when interlocutors use epistemic and evidential expressions, they not only express their estimations on the reliability of an issue, or refer to a source of information, but also perform interactional acts, such as making claims, giving justifications, or inviting a response from others. This analysis examines the meaning of evidential-epistemic expressions that occur in a written dialogic genre. The focus will be on Finnish near-synonymous adverbs that express a writer’s access to knowledge, derived from mental verbs, such as käsittääkseni ‘as far as I understand, according to my understanding’ and tietääkseni ‘to my knowledge, as far as I know’,Footnote 1 and the data consist of reader comments published in the online version of the leading Finnish daily newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat. The meaning of these adverbs is approached in two ways. First, this article aims to provide an overview of their interactional and textual functions in a written argumentative genre: What are the typical contexts where writers feel the need to refer to their own access to information? Second, it analyses the polysemy of near-synonymous adverbs that share the same morphological structure: How the writers, by selecting one of these adverbs, operate with different types of evidence and access to information?

In languages that do not have evidentiality as a grammatical category such as Finnish, speakers and writers can choose between different strategies when they refer to a source of information or a mode of knowing and their choices are motivated by the ongoing context.Footnote 2 When writers decide to use adverbs such as tietääkseni or käsittääkseni, they express that they rely on their own reasoning or experience, and the factuality of their expression is based on the information that they have access to. This easily leads to an epistemic interpretation of questioning the likelihood of the utterance. This type of hedging is illustrated in (1): The writer bases her statement concerning Google and Twitter on her own access to information, what she knows that has been stated in public discussion (she refers to different media earlier in the comment). This is explicitly conveyed by her use of tietääkseni.

However, a hedging function may also be weak, and writers may also express highly detailed information and position themselves as knowing interlocutors, as in (2), when the writer presents precise numerical data concerning a special field.

Even the figure that is in the scope of tietääkseni is expressed as a decimal, and this exactness combined with the reference to personal access to information emphasises the writer’s ability to know. This type of example is not unique in my data. In addition to ‘real’ epistemic hedging, as a marker of uncertainty, the writers also use käsittääkseni adverbs in contexts with extensive expertise as in (2), or when they present certain opinions (e.g. As far as I understand, electronic tobacco is a better choice than a traditional one). Thus, this analysis for its part illustrate that the expression of hedging constitutes a particularly interactional action (e.g. White Reference White2003; see also Fraser Reference Fraser2010), and in actual language use, hedging often merges with other functions, such as organising argumentation, rhetorical cohesion, or textual irony.

This analysis approaches the relation between evidentiality and epistemic modality through the evidential verb+kseni construction (a conventionalised form–meaning pair, see Langacker Reference Langacker, Hans Christian and Mirjam2005:158; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006:5). This set of near-synonymous adverbs share the same morphological structure, which consists of the mental verb stem + translative case suffix (-kse- ‘to, for’) + possessive suffix (-ni) referring to the speaker/writer. A characteristic of these adverbs is that they occur flexibly with different subtypes of indirect evidentiality (see, for example Plungian Reference Plungian2001:353–354; Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004:367; Squartini Reference Squartini2008:925; Marín Arrese Reference Marín and Juana2017:199–200). They also perform similar interactional and rhetorical functions in the data. This multifunctionality, or semantic flexibility, reflects a layered semantic structure. In analysing the polysemy of the verb+kseni lexemes, I adopt the concept of profiling from Cognitive Grammar, where linguistic meaning has been characterised as a knowledge frame with elements that are foregrounded and backgrounded in the semantic structure of the expression (Langacker 2005:164; Reference Langacker2008:39, 66–67). A foregrounded element therefore functions as a focus of attention, which constitutes a conceptual profile. The verb+kseni lexemes profile, that is, explicitly express the writer’s own access to knowledge, and that functions as a conceptual basis for their meaning. In addition, with each adverb, the specific aspects of epistemic and evidential processes are foregrounded or left backgrounded.

In order to gain a deeper understanding of these adverbs, I combine different approaches which complement each other: Cognitive Grammar provides a usage-based description of the semantic structure of the adverbs, and discourse analysis and interactional linguistics are applied to examine the textual and interactional features. The structure of this paper is as follows: First, I introduce the data and the verb+kseni construction in Section 2. Section 3 presents a discussion of evidentiality and epistemic modality in relation to the verbs used in the evidential verb+kseni construction. Section 4 provides a brief overview of their textual functions, and Section 5 focuses on the effect of the verb stems in their use. Finally, Section 6 concludes the results and discusses the different dimensions of inferential evidentiality that occur in written argumentation.

2. The data

The data are from the HS.fi Corpus (http://www.csc.fi), gathered from the internet site of the largest daily newspaper in Finland, Helsingin Sanomat (https://www.hs.fi). I focus on the reader comments, as the construction is extremely rare in news texts.Footnote 3 The data used in this study consist of 86,971 comment texts (from September 2011 to September 2012). The comments on the site range from one-sentence notes to longer, thirty-sentence texts. The texts represent a relatively free style of writing but are written predominately in standard Finnish. I have retained the spelling in the examples (and marked the typos with [!]) but shortened the texts when necessary, indicated by …). The discussion forums in HS.fi are moderated, but the published texts are not edited. Contributors must register in order to submit their comments, but they may adopt a nickname or pseudonym.

Johansson (Reference Johansson2017:9) makes an interesting observation on the comments submitted to news discussion to editorials in French journals. The participants typically express their ‘everyday opinions based on individual and subjective expressions that emerge from users’ private spaces’ instead of expressing explicit sources or verifications (see also Johansson Reference Johansson2014:41). Likewise, the contributors to HS.fi rarely refer to any explicit source, but on the other hand, they negotiate evidential access in their discussions, that is, to what extent other speakers can know or understand the same as the writer. Within these negotiations, the evidential adverbs are used as tools.

In present-day Finnish, the verb+kseni form has two main interpretations: the purpose construction ‘in order to do’, and an evidential-epistemic construction ‘as far as I know/understand, according to my knowledge/understanding’ (Leino Reference Leino, Ilona and Laura2005), and the latter is analysed in this article. The purpose construction is fully productive, but the evidential construction is restricted to mental verbs.Footnote 4 Both constructions are characteristic of written language. Table 1 illustrates the structure of the evidential construction in the first person.

Table 1. Constructional schema of evidential verb+kseni adverbs (first-person singular).

The core of the construction is an infinitival verb form (formed with the infinitive marker a/ä), marked by the translative case ending (-kse-). The Finnish translative expresses change, and it typically marks NPs that express an endpoint, a purpose or consequence (Voutilainen Reference Voutilainen2008), which is compatible with the ‘in order to do’ meaning. The verb+kse- form is inflected in all persons, marked by a possessive suffix (tietääkseni ‘as far as I know’, tietääksemme ‘as far as we know’, tietääkseen ‘as far as she/he knows’, etc.). The evidential construction may also include an optional possessive pronoun ( minu - n tietääkseni (1sg-gen know-tra-3sg-poss), häne - n tietääkseen (3sg-gen know-tra-1sg-poss) ‘according to her knowledge’).Footnote 5 However, the first-person singular forms dominate in the evidential construction. The third-person form, marked by the third-person possessive suffix, is used in reported speech. This latter form occurs in the HS.fi data almost entirely in the news articles, whereas the extremely rare second-person form sinun tietääksesi ‘to your knowledge’ can be found in the reader comments in questions or utterances in which the other writer is somehow challenged.

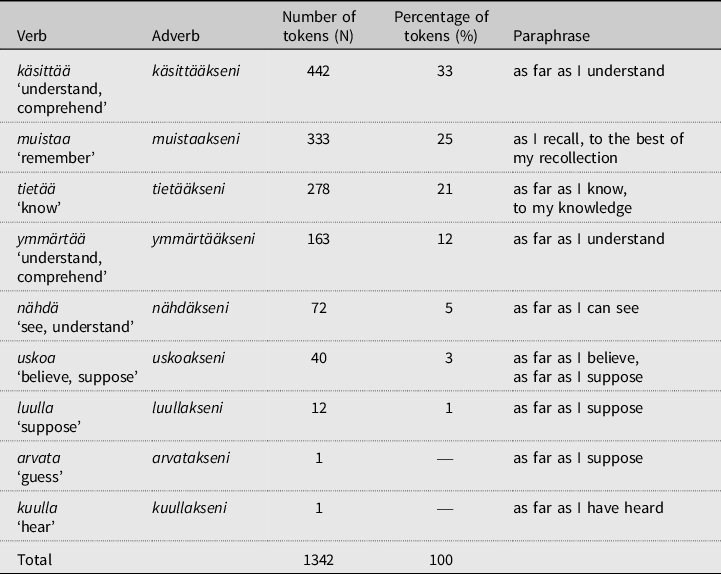

Table 2 introduces the basic data: all the tokens of the verb+kseni forms that are used as evidential-epistemic markers in reader comments.Footnote 6

Table 2. The evidential verb+kseni adverbs in HS.fi corpus reader comments.

The most frequent verb+kseni adverbs in the data are käsittääkseni ‘as far as I understand’, and muistaakseni ‘as I recall, to the best of my recollection’. The near-synonyms käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni account for almost half of the evidential verb+kseni tokens in the corpus (45%).Footnote 7 The single occurrences of the forms arvatakseni (< ‘guess’) and kuullakseni (< ‘hear’) are interesting in that they illustrate the flexibility of the construction, as both stems typically create purpose reading (a few additional verbs are used in the construction in other data, and I will return to the list of possible verbs in Section 3). The adverb muistaakseni (< ‘remember’) is excluded from this analysis, as it pertains to memory processes and this leads to a specific type of usages of the word. The analysis is therefore based on a total of 1009 examples. From these data, I have analysed the following: the syntactic form of the verb+kseni sentence in terms of tense, voice, and construction type; the state of affairs in the scope of the adverb (generic, specific, personal; negotiable, irrefutable); and the preceding and following context of the verb+kseni sentence such as whether it follows a question, quote, or a claim made in other texts. The analysis also focuses on the order of different points of view, especially whether the previous sentences express the writer’s own claims or views, or those of others. When necessary, I have also examined the other texts from a discussion thread in order to recognise the different voices in a given text.

3. Epistemic and evidential categories and the verb+kseni adverbs

Since the 1990s, the relation between epistemic modality and evidentiality has been a permanent topic in linguistics. Functional linguistics often defines these two concepts as different but intertwining or overlapping (see van der Auwera & Plungian Reference van der Auwera and Plungian1998; Squartini Reference Squartini2008; Aijmer Reference Aijmer2009; Marín Arrese Reference Marín, Juana, Marín Arrese, Marta, Jorge Arus and Johan2013, Reference Marín and Juana2017; Langacker Reference Langacker2017; Nuyts Reference Nuyts2017). From an interactional perspective, the most promising description of these concepts is to consider them as separate semantic features that arrange differently in linguistic expressions and that can also be analysed independently even though they often interlace in language use. For example, a statement that is based on direct experience is easily interpreted as more reliable than a statement based on either hearsay or inference. Finnish verb+kseni adverbs refer to the writer’s own access to knowledge and understanding and in this sense, they index evidentiality. Moreover, these adverbs easily create epistemic interpretations by representing the writer’s evaluation of her own level of knowledge.

The verb+kseni construction requires certain types of verbs to enable an evidential reading. The types of possible verbs fall into three categories: KNOW (tietää and muistaa), UNDERSTAND (käsittää, ymmärtää, and nähdä), and SUPPOSE verbs (uskoa and luulla). The KNOW and UNDERSTAND verbs differ from the third, SUPPOSE group in that the former are factive verbs, which means that the utterance in the complement clause expresses a proposition that the speaker/writer offers as true (see Kiparsky & Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971). Verbs that express supposing and believing do not create such an interpretation but instead leave the epistemic status of the proposition open and in this sense, they are non-factive.

The factive–non-factive dimensions intertwine with the different phases in the speaker’s epistemic process. Langacker (Reference Langacker2008:450–451) presents four epistemic steps, from assessing to truly knowing a fact: The initial step designates a writer’s exploration (‘assessment’) of the possible validity of an utterance, which is expressed by verbs such as English wonder, ask, consider and examine. The second step involves verbs that describe the process of an approval or rejection of the proposition (‘inclination’), such as the English verbs think, believe, and suspect. These two initial phases belong to the semantic domain of non-factive verbs, whereas the following two steps are expressed by factive verbs. Factive verbs promote the proposition as being real, but their difference lies in the construal of knowing. In the third step, verbs express a knowing as a process, an ‘action of accepting’ that something is real, such as learn, find out, realise, decide, and conclude. During the final fourth phase, expressions indicate the highest degree of certainty and, moreover, knowing is construed as a result of epistemic action, ‘the stable situation where the proposition has already been incorporated in the [writer’s] reality conception’ (Langacker Reference Langacker2008:450).

Applied to the Finnish verb+kseni format, the evidential construction covers the three latest phases. The verbs that denote assessment (step 1) appear only in the purpose construction (e.g. tutkiakseni ‘in order to examine’), but the other three steps can be expressed by evidential verb+kseni adverbs: supposing (step 2, uskoakseni, luullakseni), understanding (step 3, käsittääkseni, ymmärtääkseni, nähdäkseni) and knowing (step 1, tietääkseni). Table 3 summarises the division of these verbs in relation to their epistemic process and factuality.

Table 3. Classification of the verbs in the present study.

Inference is often defined as a key concept between epistemic modality and evidentiality (e.g. see van der Auwera & Plungian Reference van der Auwera and Plungian1998:85–86; Squartini Reference Squartini2008; Aijmer Reference Aijmer2009:64; Marín Arrese Reference Marín, Juana, Marín Arrese, Marta, Jorge Arus and Johan2013:417; Langacker Reference Langacker2017:19). For the semantics of the verb+kseni adverbs, this appears to be a relevant starting point. The verb stems that occur in the evidential verb+kseni construction are verbs of propositional attitude, referring to the semantic field of inference, which involves either assuming, understanding or knowing. What is expressed in the scope of the adverb is based on something the writer knows, thinks, or infers to be real, rather than the writer reporting a direct perception. Even sentences such as kuva on nähdäkseni ulkona otettu ‘as far as I can see, the picture has been taken outside’ emphasise the idea of the speaker’s interpretation.

The construction nonetheless displays some flexibility in relation to verb stems. First, examples of other mental verbs used to express evidential meaning are rather easy to find, especially in non-formal media such as Internet discussion forums. This implies that the construction [mental verb+kseni] itself can trigger evidential meanings, and an appropriate mental verb, most easily SUPPOSE (olettaa, otaksua, arvella ‘suppose’, occasionally even epäillä ‘doubt, suppose’, a verb that can question the reliability of the proposition), can slip into the construction and become interpreted as evidential rather than a purpose construction.Footnote 8 Second, due to their semantic structure, the evidential verb+kseni adverbs are interchangeable in many contexts, or the semantic difference is subtle (see Section 5). Most importantly, all the evidential verb+kseni lexemes profile the writer’s access to knowledge and inference as an all-encompassing schema, conveyed through the combination of a mental verb stem and the suffixes. In addition to this profiled meaning, some meaning aspects are not necessarily activated in all contexts but can either become foregrounded and relevant in the situation, or remain backgrounded and not activated, such as implying the relevance of external information sources.

In the following sections, I will illustrate this semantic flexibility. Section 4 focuses on textual and interactional functions, and Section 5 offers an overview of the epistemic and evidential dimensions in relation to different verb stems.

4. Functions of the verb+Kseni in reader comments

The most fundamental feature in all the verb+kseni lexemes is the explicitly expressed conceptualiser’s individual access to knowledge. This motivates the basic function of verb+kseni adverbs: to mark a given utterance as being the writer’s opinion, claim, evaluation, etc. In addition to specific facts (example (2) above), the evidential verb+kseni adverbs combine easily with evaluations (how good, bad, suitable, or probable something is), as in example (3), and with sentences expressing expectations, as in (4).

The verb+kseni adverbs construe a specific type of access and therefore index a specific type of dialogic orientation, a position toward the other and interpretation and anticipation of their actions (see Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin, Holquist and Austin1981[1935]:280; White Reference White2003). First, the other interlocutors are not expected to have similar access to knowledge. This meaning is created by the explicit first-person reference, but the interpretation is also supported by other constructions that express shared access (such as meidän tietääksemme ‘as far as we know’, or the productive passive participle construction, ymmärrettävästi ‘understandably’, tiettävästi ‘as far as is known’, see Jaakola Reference Jaakola2012, 2018:131–134), and the writer can select the type of access to express. Another point is that through verb+kseni adverbs, the writers suggest and consider that in addition to their personal point of view, there might be other opinions or ways of understanding a given situation. Thus, the interactional function of verb+kseni adverbs is to ‘expand’ the dialogic frame in discourse, to keep the floor open for other viewpoints (see Martin & White Reference Martin and White2005:98, 123; Simon-Vandenbergen, White & Aijmer Reference Simon-Vandenbergen, White, Aijmer, Anita and Gerda2007:36). This, in turn, explains the emergence of hedging in texts (as in example (1)) and illustrates the interactional and rhetorical basis of this type of hedging strategy. The following sections illustrate the main functions of the evidential verb+kseni adverbs that typically occur in the reader comment data. These include hedging (Section 4.1), organising different voices (Section 4.2), and ironic uses (Section 4.3). Textual and interactional functions easily intertwine, but the aim of this section is to give an overview of the uses of this type of modal adverbs. The analysis is based on the position of the verb+kseni utterance in the text, most importantly its relation to the argumentation and the different viewpoints in the discussion, and the nature of the presented information in the scope of the adverb (whether it is a generic, specific, or personal knowledge, negotiable or irrefutable fact).

4.1 Hedging

A specific outcome of the dialogic expanding is that the reader is not necessarily pressed to share the claim. Instead, writers often use these adverbs in their texts to create and maintain the impression of interlocutors arguing over different viewpoints. This is illustrated in (5) and (6), where the writers express their own viewpoints, but do not present them as the only possible alternatives. In (5), the scope of ymmärtääkseni is a claim that concerns which medicines are reimbursed by the Finnish Social Insurance system.

The last question is directed to other readers and invites them to participate. The writer explicitly requests further information to either support or contest her knowledge, which also explains the meaning of the adverb ymmärtääkseni ‘to my knowledge, as I understand the situation to be’. Similarly, in (6), the writer initially uses the same evidential adverb and also describes her access to the information (her own experiences) in the second sentence.

Through these explicit references to the writer’s own access, the readers can evaluate the claims and interpret the comment as a turn in discussion.

A specific type of hedging occurs when the scope of the adverb is a number, date, boundary, or an extreme value (see also example (2) above). The possible hedging in these utterances pertains to the accuracy of a particular detail (see Kaltenböck Reference Kaltenböck2010:247–248):

The question mark in parentheses in (8) confirms the interpretation that the writer has hedged on the duration of the problems, not their existence per se. Even in these examples, the choice of the verb+kseni is motivated by interactional goals. By construing the specific number or other detail as slightly less definitive, the writer also anticipates possible corrections. This is an even more general principle; with a slightly less categorical argument the writer can make it stronger against counter arguments (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca Reference Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca1971; Hyland Reference Hyland1998:163,166). This effect of hedging a specific detail is most prominent with muistaakseni ‘as far as I remember’, but it is likewise prominent with other lexemes, of which more than one-third occur with a detailed or an extreme value.

4.2 Organising voices in the text

As I have pointed out, verb+kseni adverbs are also used when the reading of an epistemic hedge is weak, and they fulfil other, textual and interactional functions. As the reader comments are part of a written discussion with comments published after a minor delay, the writers use different means to refer or point to something that has been stated previously. In this regard, evidential adverbs also play a role in differentiating between the various claims and viewpoints that are expressed in the texts. The verb+kseni adverbs function as an explicit marker of a writer’s claim, and in this sense they are tools to organise polyphony in texts. In (9), the differentiating function is rather clear, as there are two different viewpoints. The writer of this extract first refers to the column and its claims and then expresses her own evaluation of these claims in a sentence that contains nähdäkseni.

There are at least two possible evaluators: the writer of the column who did not question the issue sufficiently, the writer of this reader comment (who does), and possibly some other discussants. However, the passive voice (ei ole kyseenalaistettu ‘have not been questioned’) in the sentence leaves the evaluator open (since there is no subject referent), but nähdäkseni ‘as far as I can see’ defines the evaluator to be the writer of the comment text.

When the verb+kseni is placed at the beginning of a comment, readers interpret it in the frame of the news text or discussion. When this adverb occurs in the sentence-initial position, the typical interpretation is that the writer disagrees, or expresses some either additional or new viewpoint in relation to earlier texts, as in (10).

The writer in this example also appears to be rather knowledgeable on this issue, as the following declarative sentence indicates. As a consequence, the hedging function of ymmärtääkseni in this example is not as prominent as its dialogical and cohesive functions, as the adverb both links and contrasts the comment to previous texts.

The combination of a personal pronoun + verb+kseni rarely occurs in the data (34/1009), but the effect of the pronoun is obvious. The pronoun strengthens the interpretation of the writer’s own access, and this is predominantly found in contrastive positions, as in (11).

About a quarter of the occurrences of the personal pronoun + verb+kseni are comment-initial and contrastive in relation to what has been said earlier in the thread (8/34), about a quarter are preceded by a (rhetorical) question (9/34), and also the remaining mark a somewhat dissenting claim or viewpoint in other position. Respectively, 17% of the plain verb+kseni adverbs in my data are comment-initial and 10% responses to (rhetorical) questions. The verb+kseni sentences that follow a question express a disagreement, or challenge a point made in the question, as in (12) and (13).

A contrastive claim may also follow a concession, as in (14).

The adverb ymmärtääkseni occurs after the concessive sentence, and the adverb explicitly marks the sentence scope as the writer’s claim. The verb+kseni adverbs may occur in a concessive pattern, which is a specific interactional formula consisting of an initial claim, a concession, and the writer’s claim (see Antaki & Wetherell Reference Antaki and Wetherell1999; Barth-Weingarten Reference Barth-Weingarten2003; Couper-Kuhlen & Thompson Reference Couper-Kuhlen, Thompson, Auli and Margret2005), but these adverbs do not denote concession per se.

When the verb+kseni adverb occurs in a concessive sentence – and thus precedes the writer’s claim – the entire sentence either describes a generic opinion or refers to some other source than the writer. The first – the generic opinion – applies in (15), where the predicate verb is in the passive voice.

The concessive pattern in this extract emerges with ymmärtääkseni ‘as far as I understand’ and mutta ‘but’. By using ymmärtääkseni, the writer indicates that she is aware that such an opinion exists (‘outsourcing is always justified because it will be cheaper for the municipality’), and when the writer uses mutta ‘but’, she denies its rationality and continues with her own statement.

4.3 Irony

Finally, related to polyphony, an interesting context for verb+kseni adverbs are the comments in which in the scope the adverb is a factual, unquestionable piece of information, as in (16), or something the writer has experienced herself, as in (17).

Both examples create an ironic or humorous tone, and the writer of these examples appears to be playing with the epistemic and evidential meaning of verb+kseni. The ironic interpretation in (16) emerges through a combination of mismatching knowledge frames (see Rahtu Reference Rahtu2011): an undeniable fact (the sum of 0 euros is less than 29,500), and a hedge marker (‘as far I can understand’). The mismatch in (17) evolves between a hedge and a personal territory of knowledge (Heritage Reference Heritage2012). In other words, the writer indicates that she does not fully engage in the truthfulness of the utterance, even though she writes about her own experiences to which she has epistemic primacy. These ironic examples illustrate the use of the verb+kseni adverbs as a dialogical resource. In (16), the adverb invites the other readers to question the competence of the experts interviewed in the news text. In (17), the mild swearword, luullakseni and the wink sign, each contribute to a tone that is conversational and addressee-oriented.

5. The effect of the verb stem

The propositions that occur within the scope of the verb+kseni adverbs are typically specific and non-conventionalised facts (excluding ironic utterances). Thus, these are negotiable issues. All the verb+kseni adverbs share the schematic meaning of reasoning that is based on a writer’s access. However, they differ slightly in how that access is construed. The key difference between these adverbs lies in the verbs stem, which construe the knowing as a result (tietääkseni < ‘know’), or an action (see Langacker Reference Langacker2008:451). The latter type divides into two: the process of understanding (käsittääkseni, ymmärtääkseni < ‘understand’, nähdäkseni < ‘see, understand’), or supposing (uskoakseni < ‘believe’, luullakseni < ‘suppose’), and the verb stems are respectively factive or non-factive (see Kiparsky & Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971:147; Hakulinen et al. Reference Hakulinen, Vilkuna, Korhonen, Koivisto, Heinonen and Alho2004:§1487). Among these six adverbs, tietääkseni (< ‘know’) and luullakseni (< ‘suppose’) have the most specialised semantics, whereas käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni (< ‘understand’) are the most polysemous. Nonetheless, these adverbs are usually interchangeable in the sense that they trigger only slightly different interpretations.

Next, I will focus on the use of these adverbs in relation to evidence. This proves to be the main difference: whether a given lexeme typically combines with a reference to other texts or discourses, to personal experiences, or general (cultural) knowledge, and how this affects its meaning. Reader comments typically do not include an explicit reference to an information source (see also Johansson Reference Johansson2017). However, for news discussions, it is important to be able to differentiate voice, and all the verb+kseni adverbs are used to fulfill this function in the data. The basic interpretation is that the writers rely on their inference concerning their own observations on the issue, and when they do not explicitly refer to any external source of evidence, all the six adverbs are possible variants (see example (31) below), even though some differences arise in how the writer’s inference is construed.

The outline of this section follows the division of mental verbs discussed in Section 3 (and summarized in Table 3 above): knowing as a state (Section 5.1), understanding (Section 5.2) and assuming (Section 5.3).

5.1 Tietääkseni ‘to my knowledge, as far as I know’

The verb tietää ‘know’ is a factive verb that denotes knowing as a static state and it therefore represents the final step in the epistemic process (see Langacker Reference Langacker2008:451). This meaning is also reflected in the uses of the adverb tietääkseni. What is characteristic of tietääkseni is its unspecificity in relation to inferential processing and the evidential sources (whether the information is based on the other texts or discourses, or the writer’s own experience). Compared to the other evidential verb+kseni adverbs, tietääkseni does not imply a linkage to the previous text in a discussion, but instead foregrounds the writer’s own knowledge. The tietääkseni in (18) marks a specific fact (the safe alcohol limit for women) to be something the writer knows.

The comment does not reveal the source of the information, and it would even be odd if the writer had made an explicit reference to a news article as a basis for inference (?As far as I know, judged by the article). This is typical for the tietääkseni examples: In the immediate context, there either is no reference to other sources or the information source is displayed as not providing supporting evidence (e.g. Tietääkseni oikein mikään asiantuntijatieto ei puolla nuorten seksikokeilujen rajua tuomitsemista ‘As far as I know, no expert knowledge favours the condemnation of teen sex experiments’), or the the statement is based on general knowledge, as in (19).

The writers also combine tietääkseni with general and even irrefutable facts, as in (20), to create an ironic tone. While the writers declare themselves aware of the matter in the sense of ‘this is self-evident’, they invite the other discussants to see the prior issue in a questionable light.

In general, tietääkseni differs from the other evidential verb+kseni forms in that it expresses a rather high epistemic commitment and an interpretation of an unspecificity of information source. Thus, tietääkseni triggers a reading that the writer relies on her own knowledge and sources that are independent from what has been written in the other texts. In this regard, the semantics of tietääkseni backgrounds an inferential evaluation and instead particularly foregrounds the writer’s personal knowledge on the matter.

5.2 Käsittääkseni, ymmärtääkseni ‘as far as I understand’ and nähdäkseni ‘as far as I can see’

The Finnish UNDERSTAND verbs, käsittää and ymmärtää, are near-synonyms (Arppe Reference Arppe2005), and the adverbs käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni are interchangeable in all contexts (in the reader comment data, however, käsittääkseni is more frequent). The verbs käsittää and ymmärtää are factive, but they differ from tietää ‘know’ in the sense that they construe knowing as a process that involves an increase in understanding that leads to an awareness of a fact. This is also reflected in the semantics of käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni. What is foregrounded is the writer’s own interpretation of whatever it is based on: previous texts in discussion, as in examples (21) and (22) below, other evidence, as in (23), or evidence that can easily be left implicit in the comment. (The evidence source is indicated in italics in the following examples and their translations.)

Since ymmärtääkseni and käsittääkseni foreground understanding and are neutral in relation to information sources, they have the widest variation of contexts of all the studied evidential verb+kseni forms. This flexibility also makes them an easy option to replace all the other verb+kseni adverbs (including the tietääkseni (< ‘know’) examples mentioned above).

The third UNDERSTAND verb stem in the evidential verb+kseni group is nähdä ‘see’. The metaphorical extension from visual perception to understanding or knowing is documented in many languages (e.g. Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990:33–34; Gibbs Reference Gibbs1992), and the Finnish nähdä ‘see, understand’ is similarly polysemous (there are also other conventionalised epistemic-evidential derivatives of the verb stem, such as nähtävästi ‘presumably’). Nähdäkseni resembles käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni (< ‘understand’) by sharing the prominence of inferential processing. This allows them to be used in similar contexts, juxtaposed with reference to the news article or previous comments, to other texts, or without reference to evidence. In (24), the basis for the writer’s understanding is in the news article, and she explicitly refers to it.

The evidential readings in (21) through (24) are very similar ‘as far as I can see’, with ‘see’ used in the sense of understanding, and these adverbs would easily be interchangeable (if one ignores the effect of repeating the verb stem ymmärtää ‘understand’ in (24)).

However, the concrete meaning (perception) remains somewhat present in (24), and it is interesting that a typical context for nähdäkseni in the reader comment data is when writers base their interpretation on a prior statement, that is, on what they have been able to see (in both senses). Still, the visual perception (e.g. reading a text, or looking at the picture) is only the starting point, and the importance of the writer’s reasoning is present in all the usages of nähdäkseni, and even when a reference to direct perception is made, as in (25).

The text refers to a comparison based on visual perception (between dogs and wolves), but nähdäkseni directs the argumentation from perception to inferential evaluation. This interpretation is confirmed by the following sentences in which the writer discusses the problems of identification (also the lack of a photo in the original news article).Footnote 9 The form nähdäkseni in (25) particularly emphasises the writer’s processing of the input instead of pure perception.

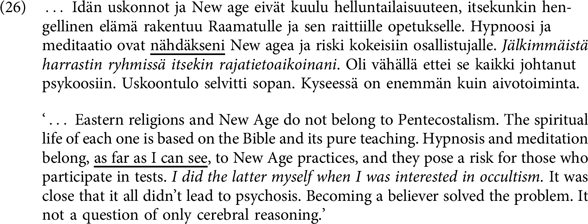

In addition to previous context types, nähdäkseni also occurs in reader comments when the writer relies on her own experiences. This experience is described explicitly in (26):

In example (26), one justification for the statement (that hypnosis and meditation are both New Age phenomena) is based on what the writer herself has witnessed. As in the previous contexts, (24) and (25), käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni would also be natural in (26), but the difference lies in whether the link to the writer’s own experience is foregrounded (by nähdäkseni) or not (by käsittääkseni, ymmärtääkseni). Since these two context types of nähdäkseni (reference to previous texts, or to own experience) dominate in the data, the writer’s own perceptions and experiences are prominent in all uses of the word.

To conclude, the importance of the writer’s reasoning is profiled in all the usages of käsittääkseni, ymmärtääkseni and nähdäkseni, but they differ in how the evidence is linked to the reasoning. Through the use of käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni (< ‘understand’) the sentence emphasises the writer’s own reasoning, and leaves the evidence open, whereas nähdäkseni (< ‘see, understand’) foregrounds the evaluation of information in relation to some available evidence, or to prior experience.

5.3 Luullakseni ‘as far as I suppose’ and uskoakseni ‘as far as I believe’

The least frequent evidential verb+kseni adverbs in the data are the forms derived from non-factive SUPPOSE verbs, uskoakseni (< ‘believe’) and luullakseni (< ‘suppose’) as these two lexemes cover only 4% of all the evidential verb+kseni adverbs in the reader HS.fi data (Table 2). On the epistemic scale, SUPPOSE verbs represent the initial step with propositional attitude, where speakers evaluate the truthfulness of a proposition, but expresses less strong commitment to its reliability than with the KNOW and UNDERSTAND verbs (see Langacker Reference Langacker2008:451). Moreover, the Finnish verb luulla tends to be interpreted as contrafactive ‘erroneously assume something’ in all other forms except the first-person present tense (Lakaniemi Reference Lakaniemi2019): With the past tenses, the interpretation of erroneous knowing (contrafactive) dominates in all persons, also in the first-person singular (e.g. Luulin, että pitäisit siitä ‘I thought you would like it [but you obviously do not]’). In this sense, tietääkseni (< ‘know’) and luullakseni represent the two endpoints of an epistemic scale of the verb+kseni adverbs. This is illustrated in the examples in which these two are juxtaposed, as in (27).

The writer specifies the mild hedge (tietääkseni ‘as far as I know’) with another, somewhat more effective hedge (tai luullakseni ‘or as far as I suppose’). The formulation resembles a self-repair as a rhetorical act with parentheses and the disjunctive conjunction tai ‘or’.Footnote 10

The meaning of hedging becomes more prominent in the semantic structure of luullakseni than with the other verb+kseni adverbs, which may partly explain its low frequency of occurrence in argumentation; it is rare in the reader comment data (12/1342), and its frequency is equally low in other data on internet discussions at csc.fi. After all, luullakseni in the data integrates assumptions and hedges, but erroneous understanding is not prominent in these comments (which is in line with the first-person present tense non-factive uses of luulla). Similar to other evidential verb+kseni adverbs, luullakseni creates an interpretation of an opinion that may change if any further information arises, as in (28).

It is interesting, however, that even though the luullakseni examples do not promote a contrafactual reading, the writers appear to prefer the other suppose-related verb+kseni forms.Footnote 11 In HS.fi data, uskoakseni (< ‘believe’) is slightly more frequent than luullakseni, and the other internet discussion data (e.g. Suomi24 discussion forum data in csc.fi) include other SUPPOSE stems, such as otaksuakseni and olettaakseni (< ‘assume’). The contexts of uskoakseni can be roughly divided into two: It serves as a neutral marker of an opinion (29), or it is combined with states of affairs that are supposed to occur in some other reality, either in the future (30) or in some hypothetical space.

Luullakseni and uskoakseni resemble the forms käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni (< ‘understand’) in that they all foreground knowing as a process but differ in that they indicate a slightly less strong basis for the claim. In this data set (although the frequencies are small), believing appears to be more convincing than supposing. This is in line with the uses of the respective finite verbs: It has been demonstrated that the first-person construction uskon, että ‘I believe that’ expresses the author’s stronger epistemic commitment than luulen, että ‘I suppose that’, as the former is often used in sentences that emphasise the author’s position, and even express a contrast (Juvonen Reference Juvonen2011:245, 247, 249; see also Fetzer Reference Fetzer2009).Footnote 12

5.4 Section summary

Even though the different verb stems foreground different evidential and epistemic aspects, stems do not fully determine the usage of a given adverb, and the verb+kseni adverbs may even be interchangeable in the data. For many examples, any of the six adverbs would create a sensible and natural reading, while each of them foregrounds certain aspects that are evidential, modal or interactional. This is illustrated in (31). The topic concerns drugs, and the comment is oriented to the previous comment. No reference is made to information sources in this example, which makes the context even more flexible for all the six verb+kseni adverbs.

The writer uses ymmärtääkseni, which like käsittääkseni (< ‘understand’), focuses on the writer’s reasoning, whereas tietääkseni (< ‘know’) would foreground the specific level of knowledge and the idea of the writer’s mind as a ‘Data Warehouse’ serving as a basis for the claim. By contrast, nähdäkseni (< ‘see’) would emphasise the writer’s experiences as a basis for the claim, or link to previous texts in a discussion. And finally, uskoakseni (< ‘believe’) and luullakseni (< ‘suppose’) would express a well-founded conjecture.

6. Discussion

This analysis illustrates the interactional nature of evidentiality and epistemic modality as well as the use of specific lexical means to construe dialogic frames in a communicative digital genre. These adverbs are evidential in that they denote to the writer’s own inference and its evidence, but they are also epistemic because they indicate the writer’s level of commitment to the reliability of the proposition.

In relation to textual and interactional functions, this study also reinforces the understanding of hedging as an interactionally motivated action (e.g. Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen2003, White Reference White2003, Kaltenböck Reference Kaltenböck2010). Within these adverbs, hedging often merges with other functions, such as anticipating other views, or creating textual polyphony and even ironic readings. The writers often offer their claims as one possible means of interpreting matters, but particularly the contrastive rhetorical patterns with verb+kseni adverbs also direct the addressee’s attention to the utterance offered as the most promoted by the writer.

The effect of genre and media is also important because these adverbs are primarily a feature of written language. It may be that in written texts, due to the properties of written interaction, there is a specific functional demand for a variety of evidential and epistemic expressions as well as for near-synonyms. Reader comments are one part of internet discussions, and in addition to facts, the texts include a variety of dialogical and rhetorical elements. When the writer’s access is expressed explicitly, this creates an impression of a dialogue in that people argue and discuss, and in this sense, this type of expression may have a role in the construal of the ‘discussion forum text’.

The textual analysis reveals the semantic flexibility and even the interchangeability of the evidential verb+kseni adverbs. Despite each of these adverbs having a specific semantic structure in relation to evidential and epistemic dimensions, they also perform similar interactional and rhetorical functions in the data. The constructional meaning profiles the writer’s own access to the information source and its processing as a basis for what will be claimed. What varies from lexeme to lexeme is the foregrounding of specific dimensions of the inferential basis, but at the same time, the interplay between foregrounded and backgrounded dimensions also enables the polysemy of a certain lexeme. The verb semantics affect the use, but does not determine it, as the constructional meaning levels out the differences. Each of these lexemes foregrounds certain dimensions, but at the same time, semantic flexibility is characteristic of this adverb type in general.

The verb stems of these adverbs are verbs of propositional attitude, and their epistemic meanings play a role in the semantics of a respective adverb and in how reliable the speaker evaluates the evidence to be. When these adverbs occur in the reader comment argumentation, they are most often used as markers of understanding on the basis of the available evidence (käsittääkseni, ymmärtääkseni < ‘understand’ and nähdäkseni < ‘see, understand’) but also as markers of ‘pure’ knowing (tietääkseni < ‘know’). Lexemes with factive verb stems represent the highest writer commitment, and they form a core of the evidential verb+kseni adverbs. Tietääkseni (< ‘know’) foregrounds the specific level of knowledge and the knowing of a result, and with it, the writers express the highest commitment to the proposition. The near-synonyms käsittääkseni and ymmärtääkseni (< ‘understand’) are the most frequent, have the most flexible meaning and the widest contextual variety, that is, they occur in different positions of a comment and in different rhetorical patterns. The meaning of hedging may be rather weak, and the idea of the writer’s inference is the most prominent. Almost as flexible is nähdäkseni (< ‘see, understand’) which especially foregrounds the idea that reasoning is based on a certain information source (for example, the news article).

The adverbs with non-factive stems, luullakseni (< ‘suppose’) and uskoakseni (< ‘believe’) result in a more pronounced reading of hedging, or an interpretation of speculation as it pertains to a hypothetical scenario. However, these adverbs are infrequent in these data. This may indicate several things. Most importantly, the evidential verb+kseni adverbs are often used when writers are rather committed to the validity of their expressed opinions and claims, and the factive verb stems obviously offer a more suitable basis for argumentation. This, in turn, may also indicate that the usage of inferential adverbs in internet discussions is based more on the need to textually mark the writers’ personal opinions than to merely reduce the writers’ commitment to their claims. Different types of data would offer more insight into SUPPOSE stem adverbs, their use in various texts and interactional use (see also Footnote 12).

In relation to the more general taxonomies of evidentials (e.g. Plungian Reference Plungian2001; Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004:367), the verb+kseni adverbs contribute to indirect evidentiality, and more specifically to the domains of inference (reasoning on the basis of evidence that can be perceived) and assumption (reasoning without perceivable evidence, including general knowledge). A characteristic of these adverbs is that they are not restricted to the expression of any specific type of information source (the multifunctionality of inferential expressions have been noticed in other languages as well, such as Simon-Vandenbergen & Aijmer Reference Simon-Vandenbergen and Aijmer2007; Cornillie Reference Cornillie2009; Nuyts Reference Nuyts2017:67). In the reader comment data, the verb+kseni lexemes indicate a small division of labour: Nähdäkseni (< ‘see, understand’) often combines with evidence that is based on the news article and thus resembles inference based on perceived evidence (see Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004:367), whereas tietääkseni (< ‘know’) promotes the general knowledge and assumption-type of indirect evidentiality, but the other lexemes blur the division between inference and assumption.

Finnish is an example of a language that has not a grammatical evidentiality system, and the semantic domain of evidentiality is primarily expressed through lexical elements. In such languages, hearsay and inferentiality seem to be the most frequent evidential meanings (Cornillie Reference Cornillie2009:46). Expressing the source of information or the mode of knowing is a linguistic choice (as these can remain unspoken), and they are always accompanied by interactional acts (making claims, giving justifications, answering questions, storytelling, etc.). As evidenced in the data, inferential adverbs readily lead to epistemic interpretations in argumentative contexts, and in this sense, evidentiality and epistemic modality intertwine in their semantics.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the three anonymous NJL reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments. I am also grateful to Tiina Onikki-Rantajääskö for her helpful comments and discussions. This study has been supported by the Kone Foundation.

Data Source

A Cognitive Grammar of Finnish in comparison with other Finno-Ugric languages research project, Department of Finnish, Finno-Ugrian and Scandinavian Studies, University of Helsinki (2014). The HS.fi News and Comments Corpus [text corpus]. Kielipankki. Retrieved from http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2014052718 (accessed 10 May 2020).