1. BACKGROUND

‘Repair’ refers to ‘practices for dealing with problems or troubles in speaking, hearing or understanding the talk in conversation’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007:503). If the repair is initiated by anyone other than the speaker whose turn caused the problem, this is referred to as ‘other-initiated repair’ (e.g. Schegloff, Jefferson & Sacks Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977, Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997). There is a typical sequence of turns, such that repair initiations occupy the position following the repairable utterance, and are followed by a repair utterance by the speaker whose preceding turn caused the problem. The sequence of turns is given in (1), following Drew (Reference Drew1997:74) (see also Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013 among others). This is the turn sequence relevant for the present study.

(1) Sequence of events in other-initiated repair

Speaker A: ‘Repairable’ utterance (Trouble source)

Speaker B: Repair initiation

Speaker A: Repair

An example from British English (International Corpus of English (ICE-GB), http://www.ucl.ac.uk/english-usage/projects/ice-gb/; Nelson, Wallis & Aarts Reference Nelson, Wallis and Aarts2002), from a legal cross-examination, is given in (2). Throughout the paper, the trouble source (‘repairable’ utterance in (1)) is marked →, the other-initiated repair expression is marked •, and the repair utterance is marked ![]() .

.

(2) Other-initiated repair (ICE-GB: s1b-065 #067-073)

A: Did Mr uh did you or Mr Hook make any reference whatever to the uh the the uh the the the the matter of uh the negotiations in in nineteen eighty-six

B: → I would think that is most unlikely

It was pro

A: Do you think quite

• What did you say

B:

No it was most unlikely I said

No it was most unlikely I saidIt was common knowledge in our industry

The trouble source is Speaker B's utterance I would think that is most unlikely. Speaker A initiates repair (or: repetition) using What did you say. Speaker B repeats what he said, changing the wording slightly, and he also gives an explanation as to why he thinks he is right about what he said.

Elements used to initiate repair include primary interjections (e.g. English huh) and the wh-word what, more complex syntactic constructions containing the interrogative pronoun what (e.g. English What did you say), as well as expressions such as sorry and pardon among others (see e.g. Schegloff et al. Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977, Drew Reference Drew1997, Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997, Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013). By using these expressions alone, the speaker initiating the repair does not focus on any particular part of the troublesome utterance. For example, the repair-initiating expression What did you say in (2) does not focus on any particular part of the troublesome utterance I would think that is most unlikely. These kinds of expressions, which focus on the troublesome turn as a whole, are referred to as ‘open-class’ expressions of other-initiation of repair (e.g. Drew Reference Drew1997, Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013, Dingemanse, Blythe & Dirksmeyer Reference Dingemanse, Blythe and Dirksmeyer2014), because the part of the utterance that caused the problem is left open, i.e. unspecified; we will follow this terminology here. Other repair-initiation techniques include rephrasing or (partial) repetition of some part of the troublesome turn, sometimes in combination with question words (e.g. You went where?; You would think what?) (Schegloff et al. Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977, Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997).

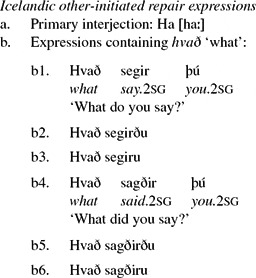

The present paper focuses on the intonation of a subset of other-initiated repair elements in Icelandic. As in other languages (Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013), open-class other-initiated repair expressions in Icelandic include the following: (i) a primary interjection corresponding to English Huh (see (3a)), and (ii) a wh-question containing the question word hvað ‘what’ (see (3b)). Throughout the text, Icelandic repair-initiating expressions occur without punctuation marks in order to avoid a bias on intonation on the part of the reader.

(3)

In Icelandic, the question word hvað cannot be used as a bare form in this function (Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013:367; Gisladottir Reference Gisladottir2015:315). Instead, the more complex forms given in (3b) are used, where (3b2) and (3b3) represent phonetically reduced forms of (3b1), and (3b5) and (3b6) represent phonetically reduced forms of (3b4).

Examples of these two Icelandic expressions used as open-class other-initiated repair expressions and of typical turn sequences are given in (4) and (5) below. These examples are taken from a data set elicited in a map-task experiment by the author of this paper (see Section 2 for details). In order to elicit interrogative utterances and in line with common practice in map-task experiments (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Brown, Shillcock and Yule1984, Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Bader, Bard, Boyle, Doherty, Garrod, Isard, Kowtko, McAllister, Miller, Sotillo, Thompson and Weinert1991, Helgason Reference Helgason, Ambrazaitis and Schötz2006, Savino Reference Savino2012, Fletcher & Stirling Reference Fletcher, Stirling, Durand, Gut and Kristoffersen2014, among many others), the maps used by the two members of a pair playing the map-task game together were not completely identical. It was therefore not always possible for the recipient of the instructions to follow the instructions of the instruction-giver. The task for each participant in the pair-wise game was to find specific landmarks, which were present on the instruction giver's map, but not the instruction follower's map. In (4), speaker Ó10 is directing speaker Ó09 to a particular landmark, which can best be reached by using a particular street on the map, called Lundahólar. Throughout the examples taken from the map-task dialogues, dots indicate hesitation.Footnote 1

(4)

Speaker Ó09 is looking for this street on her map, cannot find it, then seems to either have forgotten which street she is supposed to find or else wants to be sure about the street name, and thus uses the expression Hvað segirðu ‘What do you say?’ to initiate repetition. Speaker Ó10 immediately repeats the name of the street, which speaker Ó09 then finds.

In (5), speaker R16 describes to speaker R17 the route she should take.

(5)

In this case, speaker R17 indicates that it is possible to take the suggested route by saying Ókei. Það passar ‘Okay. That fits’, which speaker R16 does not understand, probably due to her being busy with finding the best route for R17. Speaker R16 therefore uses the repair-initiating interjection Ha to ask speaker R17 to repeat what she said, which speaker R17 does.

In Icelandic, both Ha and Hvað segirðu and its variants listed in (3b) above can also be combined with partial repetition of the troublesome turn. While in (4) and (5) Ha and Hvað segirðu are open-class repair initiators and thus focus on the troublesome utterance as a whole, in combination with a partial repetition of the troublesome turn they focus on the particular part of the turn that caused the problem. These belong to what Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Blythe and Dirksmeyer2014) refer to as ‘restricted formats’ for the initiation of repair. Examples are given in (6) and (7) for Hvað segirðu, and in (8) and (9) for Ha, all taken from the same map-task experiment.

(6)

(7)

(8)

(9)

In (6), Speaker Ó10 tells her interlocutor where she is situated: on the corner of two streets, Lómastræti and Mangavegur. Speaker Ó09 picks up Mangavegur, but not Lómastræti. She thus uses the repair-initiating expression Hvað segirðu and then repeats the part of the utterance she understood. Speaker Ó10 then repeats not only the missing part but the whole coordinated noun phrase Lómastræti og Mangavegur. Similarly, in (7), speaker R17 understands that Myndastytta is at a crossroads, which is what she repeats in combination with Hvað sagðiru, but she asks for repetition of the street names. In (8), Speaker Ó10 apparently did not understand which road she was supposed to go up next. To initiate repair, she uses Ha in combination with the directional preposition, which she understood, asking for the name of the road she is supposed to go up. In (9), Í13 asks for partial repetition of the list of street names which speaker Í14 gave him. Part of his repetition is incorrect, though: Melastræti was not among the street names in Í14's preceding turn. In her repair utterance, Í14 repeats the street names she mentioned in her previous utterance and thus corrects speaker Í13's partial repetition. These are the types of repair-initiating expressions that this paper will be systematically concerned with: Ha, Hvað segirðu and its variants, as well as combinations of these expressions with partial repetitions of the troublesome turn.Footnote 2

It has been shown in cross-linguistic research (Dingemanse, Torreira & Enfield Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013, Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) that the other-initiated repair element ‘Huh’ is typically realised with rising intonation, i.e. with an H% boundary tone. In Enfield et al.'s (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) sample of 21 languages, there are only two exceptions to this tendency: Icelandic and Cha’palaa, both of which have falling intonation associated with ‘Huh’. Both Enfield et al. (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) and Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013) claim that it is interrogative prosody that accounts for the exceptional status of Icelandic. More specifically, they argue that falling intonation is the default for questions in Icelandic and that the other-initiated repair interjection shares its intonational features with interrogatives. In this paper, I will analyse the intonation of both Ha and its syntactically more complex relative Hvað segirðu and its variants. The results for Ha will confirm Dingemanse et al.'s (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013) and Enfield et al.'s (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) earlier results with respect to the falling intonational contour. The results for Hvað segirðu and its variants, which also have falling intonation, establish that fixed other-initiated repair expressions in Icelandic have the same falling pattern throughout. I will argue against the assumption that ‘question prosody’ (Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) or ‘the local system of interrogative prosody’ (Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013) is enough to account for the Icelandic pattern for a number of reasons. Instead, I believe that these elements are not specifically marked for prosody at all, but that the H* L% combination of pitch accent and boundary tone (i.e. falling intonation) is neutral across utterance types.

Drawing on data from a map-task experiment, Section 2 will show that the repair-initiating elements Ha and Hvað segirðu in Icelandic are realised with an H* L% nuclear contour and thus have falling intonation. Section 3 will discuss these results. Section 4 concludes the discussion.

2. MATERIALS, ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

The materials used here are taken from a map-task study carried out by the author of the paper in Iceland during the months of October 2013 to January 2014, and May/June 2014. Overall, 84 participants (42 pairs) were recorded. In order to allow for a study of regional variation, speakers from the following parts of the country were recorded: Reykjavík for the variety of the capital area (R; 24 speakers), Ísafjörður for the north-western (Western Fjords) variety (Í; 26 speakers), and Ólafsfjörður (Ó; 14 speakers) and Húsavík (H; 20 speakers) for the northern variety. Of these 84 speakers, two speakers recorded in the Western Fjords were not considered here because they were non-native speakers. The remaining 82 participants entered the analysis reported on below.

Four maps were created: two Tourist (instruction follower) maps and two Guide (instruction giver) maps; they are given in Figures 1 and 2. The maps were designed such that they were chequered town maps with street names and names of landmarks given. All names of streets and landmarks were chosen such that they were (i) maximally sonorant, and (ii) there were identical numbers of names of streets and landmarks with open first syllables (streets: N = 11, e.g. Nínugata; landmarks: N = 5, e.g. Nínuverslun; first syllable [niː]) and closed first syllables (streets: N = 11, e.g. Lundahólar; landmarks: N = 5, e.g. Lundasafnið; first syllable [lʏnˑ]). This was done because Icelandic has word-initial primary stress (Einarsson Reference Einarsson1973; Árnason Reference Árnason1985, Reference Árnason, Gregersen and Basbøll1987, Reference Árnason and Werner1998; Thráinsson Reference Thráinsson, König and van der Auwera1994, among others). Controlling for syllable structure allows optimal study of pitch-to-segment alignment (e.g. Dehé Reference Dehé2010 for Icelandic). However, in the present context, names of streets and landmarks are not important.

Figure 1. Maps used by participant A; upper panel: Tourist map Bx; lower panel: Guide map An.

Figure 2. Maps used by participant B; upper panel: Tourist map B; lower panel: Guide map Ax.

The Tourist maps (maps B and Bx; see upper panels in Figures 1 and 2) had lists of landmarks at the bottom and Xs in every corner as potential sites of landmarks. The Guide maps (maps An and Ax; see lower panels in Figures 1 and 2) had all the landmarks placed in the corners, allowing for the guide to give directions to the tourist. No routes were drawn on any map. An experimental session was such that two participants, A and B, did the map task together. They were paired in such a way that they knew each other well (e.g. close friends, life partners, parent and son or daughter) in order to allow for informal speech in a comfortable situation. The maps were paired such that each participant in an experimental session received one Tourist map and one Guide map. Specifically, participant A received Tourist map Bx and Guide map An (see the pair in Figure 1), and participant B received Tourist map B and Guide map Ax (see the pair in Figure 2). Hence, both participants played both roles, Tourist and Guide, in one experimental session.

The task of the Tourist was to locate all landmarks given at the bottom of the map by asking the Guide for directions. The task of the Guide was to guide the Tourist to these landmarks by giving directions, using the street names given on the map and avoiding the words áfram ‘forward, straight on’, vinstri ‘left’, and hægri ‘right’.

All four maps were slightly different from each other in that the landmarks and street names were identical, but their locations on the maps differed. The candidates were seated such that they did not see each other's maps and they were not told in advance that the maps were not the same. They had to interact with each other in order to nevertheless locate their landmarks correctly.

Participants typically changed turns in being Tourist and Guide after each landmark they located on the map. For example, participant A (Tourist role) began by asking participant B (Guide role) for the location of Lundasafnið on her map Bx. Participant B used his map Ax to guide participant A from her point of departure (‘upphafsstaður’) to this landmark. Since the maps were not identical, there had to be some interaction (such as questions and answers, imperatives, repair sequences) before A found the landmark. Once the landmark was located, the participants swapped roles. Participant B, now Tourist, asked A for the location of landmark Landakirkja on his map B. Participant A now used her map An to give directions until the landmark was located on A's map B. The procedure was repeated until each participant had found the last of the ten landmarks on their maps. To find the first landmark, participants started at their point of departure. For every following landmark, they started from the previously located one.

The subjects were recorded on separate channels in order to avoid an overlap between the subjects when they were speaking simultaneously. Recording was done using two Microtrack II (M-Audio) recorders and two Rode NT-5 condenser microphones. All map-task dialogues were orthographically transcribed by native speakers of Icelandic before each utterance was edited into an individual sound file and saved and sorted according to utterance type.

For the present purpose, only instances of Ha and Hvað segirðu and its variants were included in the prosodic analysis. Uses of these elements other than as repair-initiating expressions were excluded from the analysis. Generally speaking, cross-linguistically, elements used as other-initiated repair expressions are not limited to this one function (see e.g. Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997 for English). In Icelandic, Hvað segirðu is lexically identical to the Icelandic equivalent of English ‘How are you?’; however, such cases did not occur in the map-task corpus. Icelandic Ha can also be used to express, for example, surprise or incredulity, without initiating repair (see (10) and also (16) in Section 3 below; see also Gisladottir Reference Gisladottir2015 on other uses of Ha in Icelandic). These uses of Ha (N = 17) were excluded from the analysis because they did not simultaneously initiate repair (see (10)).

(10)

Overall, the 82 speakers included in the present analysis produced 73 instances of repair-initiating Ha and 101 instances of repair-initiating Hvað segirðu and its variants, listed in (3) above. These were divided according to whether they were open-class expressions focusing on the troublesome utterance as a whole (Ha: N = 59; Hvað segirðu: N = 35) or were focusing only on parts of the troublesome turn and combined with material from that turn (Ha: N = 14; Hvað segirðu: N = 66). All items were prosodically analysed in Praat (Boersma Reference Boersma2001, Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2012) by the author of this paper. The monosyllabic Ha was analysed on two tiers: a tonal tier for intonational analysis in terms of pitch accents and boundary tones, and a text tier (see Figure 3). The analysis of the more complex Hvað segirðu included an additional segment tier (see Figures 4 and 5). Where relevant and for longer sound files, a second text tier was included for the interlocutor of the speaker (see Figure 5, where the bottom tier spells out the beginning of the repair utterance).

Figure 3. Open-class Ha (Speaker H01, female).

Figure 4. Open-class Hvað segirðu (Speaker R18, male).

Figure 5. Hvað segirðu combined with material from the troublesome turn (Speaker R16, female; example (7)).

The results of the prosodic analysis were such that all 73 cases of Ha (100%) and all 101 cases of Hvað segirðu and variants (100%) were realised in their own Intonational Phrase (IP) with an H* pitch accent (the peak being reached early in the vowel of Ha and Hvað, respectively) and subsequent fall of the f0 contour terminating in L%, regardless of whether they were open-class expressions or focused only on parts of the troublesome turn. These findings confirm Enfield et al.'s (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) results, who also found falling contours for Ha. In addition, essentially the same intonational pattern as found for Ha was also found for the syntactically more complex repair initiator Hvað segirðu and its variants, i.e. an H* pitch accent followed by downward pitch movement towards L%. Representative examples are given in Figure 3 (open-class Ha), Figure 4 (open-class Hvað segirðu), and Figure 5 (Hvað segirðu combined with part of the troublesome utterance, see example (7) above). In Figure 5 note the L% terminating the prosodic constituent spanning Hvað sagðiru, followed by midlevel pitch associated with á gatnamótum ‘at the crossing’ signalling incompleteness. Note further that the speaker's turn ends after gatnamótum. The remaining part of the figure pictures the beginning of the interlocutor's repair utterance (Malar-, associated with rising pitch, but plotting only part of the speaker's utterance).

Monosyllabic Ha (Figure 3) is associated with a fall from H* to L%. The more complex Hvað segirðu (Figures 4 and 5), too, is realised with a fall from H* and it is phrased in its own IP terminating in L% regardless of whether it is used as an open-class expression (Figure 4) or combined with material from the troublesome turn (Figure 5), focusing on the remaining part of that turn. In Figures 4 and 5, note the association of H* with the question word hvað. This is due to perceived prominence associated with this syllable, but also to the assumption that Hvað segirðu is a fixed expression which forms one prosodic word. Since word stress is initial in Icelandic, H* associates with the first syllable of Hvað segirðu.Footnote 3

3. DISCUSSION

The results presented above are clearly consistent with the findings of Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013) and Enfield et al. (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) on the intonation of the Icelandic other-initiated repair expression Ha (see also Gisladottir Reference Gisladottir2015): it is realised with a falling contour, specifically a contour consisting of an H* pitch accent followed by a downward pitch trend and terminating in L%. In addition, I have shown that Hvað segirðu and its variants are realised with the same kind of contour throughout. Both elements, Ha and Hvað segirðu, are phrased in their own Intonational Phrase and have falling intonation (i.e. end in L%) regardless of whether they are used on their own or in combination with partial repetitions from the troublesome turn.

So why does Icelandic have falling intonation associated with repair-initiating elements when so many other languages have rising intonation (Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013, Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013)? Enfield et al. (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013:362) suggest that it is ‘question prosody’ that accounts for this fact. Given that in Icelandic the ‘low boundary tone is typically used at the end of utterances (both declaratives and questions) to mark finality (Árnason, Reference Árnason and Werner1998; Dehé, Reference Dehé2009)’ and given that ‘the preferred nuclear question contour in wh-questions and polar questions is a falling bitonal pitch accent followed by a low boundary tone, H*L L% (Dehé, Reference Dehé2009)’ it is not surprising, Enfield et al. (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013:362) argue, that other-initiated repair expressions can also be realised with falling intonation. Similarly, Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013:3–4) maintain that because ‘falling intonation is the preferred intonation in wh-questions’ in Icelandic, and because ‘the interjection shares its intonation with the question word-based expression for open repair initiation’, the falling intonation found for Icelandic Ha ‘appears to be calibrated to the local system of interrogative prosody’. Note, however, that no results as to the intonation of ‘the question word-based expression for open repair initiation’ are reported in Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013). In what follows, I will provide a number of reasons why ‘question prosody’ or ‘the local system of interrogative prosody’ cannot be enough to account for the Icelandic pattern. I will instead argue for an alternative account, one in which Ha and Hvað segirðu are not specifically marked for prosody at all but are realised with a combination of pitch accent and boundary tone which is unmarked across utterance types. In particular, ‘falling intonation’, i.e. L%, is typical across utterance types.

3.1 Icelandic intonation

To begin with, a few remarks are in order about Icelandic intonation. Icelandic question intonation has not in fact been systematically studied and relatively little is known about intonational meaning. The default intonation in both polar questions and wh-questions is to date assumed to be falling to a low boundary tone (L%; e.g. Árnason Reference Árnason2011). According to Árnason (Reference Árnason2005:476), polar and wh-questions are both falling but differ in their nuclear pitch accent. While L*+H (i.e. a low pitch target associated with the accented syllable followed by a rise) combined with L% is typical of neutral polar questions, a typical wh-question has an H* type of nuclear pitch accent (i.e. a high pitch target associated with the nuclear syllable, as in the first syllable of kartöflurnar ‘potatoes’ in (11b)) followed by a low boundary tone L%. This is illustrated in (11) (example (11a) is from Árnason Reference Árnason2011:323, (11b) from Árnason Reference Árnason2005:476).

(11)

In addition, Árnason (Reference Árnason2005:477) argues, the interrogative pronoun in wh-questions (hvar in (11b)) will be associated with a prenuclear high pitch accent (H in (11b)) unless unnecessary, for example, due to repetition in a given context.

Along with these typical patterns, both falling (L%) and rising (H%) question contours have been reported for polar and wh-questions by Árnason (Reference Árnason2005, Reference Árnason2011) and Dehé (Reference Dehé2009). According to Árnason (Reference Árnason2011:323), questions with rising intonation ‘have special connotations’. For example, in polar questions, L*+H combines with L% in ‘matter of fact’ polar questions functioning ‘as simple requests for information’ as in (11a), while H% may, for example, be used in a polar question which functions more like a ‘friendly suggestion . . ., which calls for an immediate reply’ (Árnason Reference Árnason and Werner1998:56; his example: Eigum við að koma til Nönnu? ‘Should we go and see Nanna?’ with a L*+H H% nuclear contour realised on Nanna). In wh-questions, H% may, for example, convey surprise or impatience (Árnason Reference Árnason2005:477). For example, the same wh-question as in (11b) but produced with an L*+H H% nuclear contour is conceivable in a situation in which the speaker has been looking for the potatoes for a while, cannot find them in the usual places and wonders where they are (Árnason Reference Árnason2005:477).

However, it has to be noted again that none of these suggestions are based on a systematic analysis of spoken language data. Dehé (Reference Dehé2009:30) states explicitly that ‘[f]uture research on question intonation will have to show how meaning relates to intonation’; this ‘future’ work is in progress at the time the present paper goes to press. Note also that Dehé's (Reference Dehé2009) material was not designed specifically to address question intonation. Árnason (Reference Árnason and Werner1998) studies only polar questions, but not wh-questions. While it does seem to follow from all this that question intonation is typically falling in Icelandic, it is not very safe at this stage to draw conclusions about why Ha has falling intonation from previous work on Icelandic question prosody.

Moreover, falling intonation in Icelandic is not indicative of interrogative meaning alone. In fact, it is likely that it is not indicative of interrogative meaning at all, since other utterance types, such as declaratives, have falling f0 contours, i.e. are terminated by L%, too (Árnason Reference Árnason and Werner1998, Reference Árnason2005, Reference Árnason2011; Dehé Reference Dehé2009, Reference Dehé2010). If intonation marks an utterance as question in Icelandic, parts of the f0 contour other than the final fall to L% must be responsible. This could be the pitch course in the nuclear accent (e.g. Árnason Reference Árnason2005:475–476, Reference Árnason2011:322–323 assumes that L+H* may be the typical nuclear accent in Icelandic declaratives, while L*+H may be typical in polar questions) or the prenuclear region (see e.g. Petrone & Niebuhr Reference Petrone and Niebuhr2014 for the role of the prenuclear region in German), or it could be the slope of the pitch contour (e.g. van Heuven & Haan Reference van Heuven, Haan, Gussenhoven and Warner2002 for Dutch, Kaiser & Baumann Reference Kaiser and Baumann2013 for German, among others). As far as Icelandic is concerned, this is a topic for future research.

Another aspect to keep in mind is dialectal variation in the intonation of Icelandic. While dialectal variation has yet to be studied systematically, it has been suggested (and is a common assumption among speakers of Icelandic) that speakers in the north of Iceland have more rising terminals (H%) in declaratives than speakers in the south and that the functions of the final rise may be more neutral in the north (Árnason Reference Árnason1994–95:104–105, Reference Árnason2005:479, Reference Árnason2011:324). If this holds for declaratives, it may also hold for questions. If the intonation of Ha is in line with question prosody, we would then expect regional differences (specifically perhaps more final rises in northern Icelandic data) also in the intonation of repair elements. However, this is not the case. As reported in Section 2 above, all contours for Ha and Hvað segirðu were falling regardless of the origin of the speaker or the location of testing.

3.2 Question intonation in other languages

Next, consider question intonation in other languages, specifically languages which have rising intonation associated with the other-initiated repair expression ‘Huh’. While Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013:6) claim that ‘[i]ntonation melodies appear to be linked to the interrogative prosodic system, which may differ from language to language’, question prosody in other languages is not addressed in their study in the same way as Icelandic. It is therefore possible that in Icelandic, the intonation of Ha fits in with general question prosody, but that in other languages it does not. In fact, wh-questions in particular are typically realised with falling f0 contours in a number of languages, crucially including languages which have rising ‘Huh’. In Italian, for example, H+L* L%, i.e. a nuclear contour falling towards a low boundary tone, which is also typical for broad focus declaratives, is most common for information-seeking wh-questions (Gili-Fivela et al. Reference Gili-Fivela, Avesani, Barone, Boci, Crocco, D’Imperio, Giordano, Marotta, Savino and Sorianello2015; see also Chapallaz Reference Chapallaz and Abercrombie1964, D’Imperio Reference D’Imperio2002). In Gili-Fivela et al.'s (Reference Gili-Fivela, Avesani, Barone, Boci, Crocco, D’Imperio, Giordano, Marotta, Savino and Sorianello2015:195) words, ‘wh-questions show a statement-like intonation (that is, H+L* L%)’. Nevertheless, in Italian the primary interjection [ɛː] used for other-initiated repair is realised with rising intonation (Enfield et al. Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013). The falling contour, terminating in L%, is also common in neutral wh-questions in two other Romance languages in Enfield et al.'s (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) corpus: French (e.g. Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Sichel-Bazin and Yoo2015) and Spanish (e.g. Sosa Reference Sosa2003; Vanrell & Fernández Soriano Reference Vanrell, Soriano, Campbell, Gibbon and Hirst2014; Hualde & Prieto Reference Hualde and Prieto2015). According to Enfield et al. (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013), both have a rising contour associated with their other-initiated repair interjection (French: [![]() ], Spanish: [e]). The falling (declarative) contour is also considered the basic contour for wh-questions in English (e.g. Schubiger Reference Schubiger1958, Bartels Reference Bartels1999, Hedberg & Sosa Reference Hedberg and Sosa2002) and Russian (Leed Reference Leed1965), two further languages in Enfield et al.'s (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) corpus, which have rising contours associated with the primary interjection used in other-initiated repair contexts (Russian: [haː]). Therefore, in these languages, the intonation of repair-initiating expressions cannot be accounted for along the lines of question prosody.Footnote 4

], Spanish: [e]). The falling (declarative) contour is also considered the basic contour for wh-questions in English (e.g. Schubiger Reference Schubiger1958, Bartels Reference Bartels1999, Hedberg & Sosa Reference Hedberg and Sosa2002) and Russian (Leed Reference Leed1965), two further languages in Enfield et al.'s (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013) corpus, which have rising contours associated with the primary interjection used in other-initiated repair contexts (Russian: [haː]). Therefore, in these languages, the intonation of repair-initiating expressions cannot be accounted for along the lines of question prosody.Footnote 4

3.3 Further considerations

In addition to the above points, there is perhaps no need for other-initiated repair elements to have question intonation. It is true that repair-initiating elements may be lexically and syntactically identical to wh-questions (English: What? What did you say?) and that semantically, they are asking for information about a unit which may be a phrasal or clausal constituent in syntax (see the examples above), just like wh-questions (which are therefore also referred to as constituent questions). However, other factors contribute to their unambiguous meaning as repair initiators in context even without question intonation. One such factor is their sequential positioning (Schegloff Reference Schegloff1997). For example, as noted in Section 2 above, Icelandic Hvað segirðu has more than one meaning/use, one as a repair initiator and another as a greeting, equivalent to English How are you?. Clearly, these two uses occur in different sequential positions in a conversation, which renders confusion of the two meanings unlikely. Similarly, Ha can have more than one meaning in Icelandic (see example (10) above for a meaning other than repair initiator). Even within prosody, falling vs. rising intonation in general (or: an L% vs. H% boundary tone) may be complemented by other features contributing to the interpretability of Ha/Hvað segirðu in context. For example, we know from the literature that along with the final boundary, listeners are sensitive to the prosodic realisation of the prenuclear contour (Petrone & Niebuhr Reference Petrone and Niebuhr2014) and the slope of the pitch contour (van Heuven & Haan Reference van Heuven, Haan, Gussenhoven and Warner2002, Kaiser & Baumann Reference Kaiser and Baumann2013) when identifying questions vs. declaratives. Another factor may be voice quality. For example, Rialland, Ridouane & Kassan (Reference Rialland, Ridouane and Kassan2009) report that in African languages, voice quality contributes to the distinction between questions and assertions.

Given the above considerations, it does not follow from what we know about question prosody in general that it can account for the intonation contours found with repair-initiating expressions in Icelandic. For all we know, lexical and sequential-positioning factors may suffice to identify these expressions and their meaning in context and it may be unnecessary to mark these expressions prosodically, in addition to lexical and syntactic form and position. It may also be the case that prosodic features other than high boundary tones help to unambiguously mark repair initiators. It is conceivable that several distinct factors from different linguistic modules contribute to the interpretation of repair-initiating expressions, and that the relative impact of these factors varies across languages. For example, if high pitch at the end of utterances is more likely to result in question interpretation (e.g. Bolinger Reference Bolinger and Greenberg1978, Ohala Reference Ohala1983, Gussenhoven & Chen Reference Gussenhoven and Chen2000), then this is still only one factor among many available factors, among them syntax (interrogative word order), lexical meaning and sequential position. To be sure, for repair-initiating expressions, syntax is only available with complex structures such as English What did you say? or Icelandic Hvað segirðu; lexical meaning is, however, also available for one-word expressions such as English Huh/Icelandic Ha and interrogative pronouns such as what. It has been argued that the primary interjection huh is a word ‘in the sense of being a conventional lexical sign which must be learnt’ (Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013:1). However, if it is a ‘lexical word’ (Dingemanse et al. Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013:6) with a certain specified meaning, and if the sequential context only allows for one meaning (namely, asking for repair/repetition of a troublesome utterance), then simultaneous intonational marking may be unnecessary and may thus be suspended.

3.4 Other-initiated repair expressions Ha and Hvað segirðu compared to related utterance types

Other-initiated repair elements and questions clearly have at least one thing in common: both utterance types are used to ask for information which the speaker assumes the listener can provide. Other-initiated repair expressions are arguably most closely related to wh-questions, asking for information typically expressed by a syntactic constituent such as a clause or a phrase. This also accounts for the syntactic similarities between wh-questions on the one hand and other-initiated repair expressions such as English What did you say or Icelandic Hvað segirðu on the other. However, repair on the part of the speaker can also be initiated by the listener using expressions which are syntactically identical to polar questions, such as English Can you say that again (Icelandic: Viltu segja þetta aftur). At the same time, the intonation of wh-questions and polar questions differs in many languages. For example, the standard assumption for languages such as English and German is that neutral polar questions are typically rising and neutral wh-questions are typically falling (e.g. Schubiger Reference Schubiger1958, Bartels Reference Bartels1999 for English; Grice & Baumann Reference Grice and Baumann2002, Grice, Baumann & Benzmüller Reference Grice, Baumann, Benzmüller and Sun-Ah2005 for German). In Icelandic, the default intonation in both question types (as in declaratives) is to date assumed to be falling, with rising intonation serving additional functions or having ‘special connotations’ (Árnason Reference Árnason2005, Reference Árnason2011). However, even if Icelandic polar questions and wh-questions are typically realised with the same L% boundary tone, their intonational realisation has been said to differ with respect to the nuclear accent (L*+H in polar questions, H* in wh-questions; Árnason Reference Árnason2005, Reference Árnason2011).

The map-task corpus contains a number of examples of the polar question Viltu segja þetta aftur? ‘Will you say that again?’ used as repair initiators, some of which are realised with falling (L%), some with rising (H%) intonation. In (12), the f0 contour associated with viltu segja þetta aftur used as repair initiator together with Hvað segiru is falling towards L% (see Figure 6). In (13) it is rising towards H% (see Figure 7).

Figure 6. Falling polar question as repair initiator (Speaker H18, female; example (12)).

Figure 7. Rising polar question as repair initiator (Speaker H09, female; example (13)).

(12)

(13)

Speaker H09 in (13) seems to be totally confused about her task at this stage, even asking whether she is using the right map. In her repair-initiating utterance, Hvað sagðirðu is combined with the polar question Viltu segja þetta aftur? ‘Will you say that again?’, asking explicitly for repetition. While Hvað sagðirðu is realised with its typical intonational contour terminating in L%, the following polar question has rising intonation terminating in H%. The rising pattern is found despite the fact that both the default intonation of polar questions and the intonation of the repair initiators Ha and Hvað segirðu are falling. If Ha and Hvað segirðu have falling intonation because the default (wh-)question intonation is falling, then perhaps the intonation of Viltu segja þetta aftur? should follow the default intonation of polar questions, which is to date also assumed to be falling. However, this is not the case in (13)/Figure 7. To be sure, other pragmatic factors may demand H% in (13), but crucially, H% is never found with Ha and Hvað segirðu. I take this as further evidence that it is not question prosody (or not question prosody alone) which accounts for the falling intonation of Ha and Hvað segirðu in Icelandic. Another utterance type that can be used as repair initiator in Icelandic (and other languages) is the imperative; see (14) and (15) below. Both polar questions and imperatives are verb-first in Icelandic (see e.g. Thráinsson Reference Thráinsson2007). Moreover, both in question formation and in imperative formation, the pronoun (þú ‘you’-2sg) can be cliticised to the verb (as seen in examples (12) and (13) above: viltu = vilt + þú). The imperatives in (14) and (15) differ from the polar questions in (12) and (13) in the verb form, which is indicative in (12) and (13), but imperative in (14) and (15) (compare imperative segðu in (14) and (15) with indicative segirðu). Interestingly, the imperative repair initiator, like the polar question used as repair initiator, may be produced with either falling intonation (see (14)/Figure 8) or rising intination (see (15)/Figure 9).

Figure 8. Imperative with falling contour (Speaker Ó01, female; example (14)).

Figure 9. Imperative with rising contour (Speaker Ó01, female; example (15)).

(14)

(15)

Finally, note that Ha, when serving a function other than repair initiator, can be used with rising intonation and is then not understood as a request for, and does not trigger, repair or repetition. Consider the example in (16).

(16)

The dialogue in (16) contains three occurrences of Ha, all uttered by speaker H02 and numbered 1–3. The first one is clearly a repair initiator, realised with falling intonation and triggering exact repetition of the troublesome utterance. The second instance expresses amazement rather than asking for repetition, and the same speaker continues immediately, answering H01's question. The third instance, plotted in Figure 10, has rising intonation and does not trigger repair/repetition. It is followed by a silent stretch of approximately five seconds, after which the same speaker continues. Note that it is not only the final boundary tone which is different in this case (H%), but also the nuclear accent, which is L*+H (instead of H*), the L being aligned early in the vowel.

Figure 10. Ha not used as repair initiator (Speaker H02, male; example (16)).

3.5 An alternative approach

A number of reasons have been given in the preceding sections as to why it is not immediately plausible to assume that the invariant intonation of Icelandic Ha and Hvað segirðu is accountable for in terms of Icelandic question prosody. The present line of argumentation thus goes against the one put forward in Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013) and Enfield et al. (Reference Enfield, Dingemanse, Baranova, Blythe, Brown, Dirksmeyer, Drew, Floyd, Gipper, Gísladóttir, Hoymann, Kendrick, Levinson, Magyari, Manrique, Rossi, Roque, Torreira, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013). But then the question arises: if it is not question prosody that determines the intonational realisation of Icelandic Ha and Hvað segirðu, what is it? One possible answer is that we are dealing with a kind of conventionalised, or, as an anonymous reviewer suggests, grammaticalised pattern. This would suggest a fixed relation between a lexical item and an intonational contour. Specifically, the primary interjection Ha, analysed by Dingemanse et al. (Reference Dingemanse, Torreira and Enfield2013:6) as a lexical word, and the fixed lexicalised phrase Hvað segirðu would both be linked to an intonational contour consisting of an H* pitch accent followed by an L% boundary tone. While in light of a 100% result such a direct relation seems to suggest itself, this analysis would also raise the question of how this relation between lexical item and intonational contour comes about in an intonational language like Icelandic, which does not otherwise have lexical specification of tonal contours. Note further that in research on grammaticalisation and prosody, grammaticalisation has been linked to phonetic reduction, attrition, erosion or loss of segmental material, and also to loss of prominence and to prosodic integration (see Wichmann Reference Wichmann, Narrog and Heine2011 for a recent overview), but never to a specific intonational contour.

Another approach, one we will pursue here, is to assume that the Icelandic repair expressions Ha and Hvað segirðu are simply not specifically marked for intonational features, and in particular not for the H* L% sequence or falling intonation. The neutral contour in Icelandic declaratives and questions ends in L%, with (L+)H* being the neutral pitch accent in declaratives and wh-questions, the same contour as found with the repair-initiating elements Ha and Hvað segirðu. Deviating intonational patterns signal special connotations. The specific function of repair initiators follows from their lexical entry (assuming, as above, that both Ha and the more complex (but lexicalised) Hvað segirðu have their meaning specified in the lexicon), as well as from their sequential position in discourse. Their meaning is postlexically paired with neutral intonation, i.e. a nuclear H* accent to support the conveyed meaning, followed by L%. No special meaning or connotation is added which would require non-default intonation. An analysis of this kind seems to predict that rising intonation with repair initiators should in principle be possible if the request for repair is paired with some kind of special connotation. However, I argue that this does not normally happen. Recall that for wh-questions, potential candidates for special connotation signalled by H% would be, for example, surprise or impatience (Árnason Reference Árnason2005:477). Surprise is unlikely in the context of repair-initiating elements if we assume that it is impossible for listeners to be surprised by something they have not understood and which they request to be repaired/repeated. When Ha is used to signal surprise, such usage crucially indicates understanding on the part of the speaker uttering Ha, i.e. Ha loses its repair-requesting function simply because there is no need for it (as in example (16) above), and it may then at best be confirmation-seeking. Impatience paired with a request for repair, on the other hand, is conceivable. Imagine a situation in which an interlocutor has to ask for repetition again and again, becoming increasingly impatient. While it does not occur in the present data set, and is perhaps rare in general, such a situation does not seem to be implausible. However, notice that when produced with a rise, the non-neutral, special meaning, i.e. the meaning other than the request for repair, may prevail and may thus result in a discourse situation in which Ha/Hvað segirðu fails to be understood as a request for repair, which would not be intended. Therefore, in order not to have its repair-requesting meaning overridden by some other meaning and to serve its repair-requesting function, default intonation will not normally be changed.

The fact that imperatives and polar questions in repair contexts may have rising intonation (as observed in (12)/Figure 7 and (14)/Figure 9 above) can then be accounted for as follows. Neutral polar questions (and presumably imperatives, although I am not aware of any study on the intonation of Icelandic imperatives) have falling intonation (L%). H% may signal different or additional aspects of meaning. While the request for repair may be seen as an additional aspect of meaning in polar questions and imperatives, intonational marking of this request is unnecessary, given the compositional lexical meaning of the respective utterance (e.g. segja aftur ‘say again’ as request for repetition). Therefore, L% occurs. Other special connotations may then play a role for the use of H%. Recall that Árnason (Reference Árnason and Werner1998:56) suggests H% for the use of a polar question as a friendly suggestion, calling for an immediate reply, and easily conceivable in a repair context. In the dialogue in (13) (see the final rise in Figure 7), impatience on the part of the speaker is also possible, given that the speaker does not even know which map to use at the time of utterance. The variation observed with polar questions and imperatives serving in repair contexts thus seems to be in line with the variation found in declarative and interrogative prosody: L% is used in neutral utterances, H% may be associated with special connotations. Ha and Hvað segirðu in their function as other-initiated repair expressions, on the other hand, do not normally come with special connotations, and are thus used with L% throughout. If a special connotation is added (e.g. impatience), this seems to be done by means of another phrase, which may either be used instead of Ha/Hvað segirðu (e.g. as in (14) and (15), where an imperative is used on its own) or follow it (e.g. the polar questions in (12) and (13), or partial repetition of the troublesome utterance).

4. SUMMARY

On the basis of evidence from a map-task experiment, this paper has shown that the Icelandic other-initiated repair expressions Ha and Hvað segirðu are realised with falling intonational contours, which sets them apart from related expressions in many other languages. Instead of tying the intonation of these expressions too closely to question prosody, I have argued that they are in fact not specifically marked in intonation at all, or at least not by pitch accent and boundary tone or ‘falling intonation’, and instead follow a neutral pattern also found with other utterance types in Icelandic, including (but crucially not exclusively) questions. Given their unambiguous lexical meaning paired with sequential position, prosodic marking is not necessary and would in fact suggest additional shades of meaning, which are not in line with a mere request for repair/repetition and thus not intended. Future research will show whether and how other prosodic features (e.g. pitch range, voice quality) help to further set repair initiators apart from other meanings of their homophones.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The empirical work presented here was partly supported by a Snorri Sturluson Fellowship from the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies to the author, which I hereby gratefully acknowledge. The maps used in the map task were designed in collaboration with Þorbjörg Þorvaldsdóttir, who also drew the maps. I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for NJL for their helpful comments.