1. INTRODUCTION

In this article, we discuss ‘get’-passives in Icelandic, with some comparison to other Germanic languages.1 By ‘get’-passive, we refer broadly to constructions where a word translating to English get is followed by a verb phrase headed by a verb in its passive participial form. While Icelandic has played an important role in our understanding of case marking and valency alternations, ‘get’-passives have not, to our knowledge, been studied in this language before. The present study presents the empirical landscape of Icelandic ‘get’-passives with a special focus on how their case-marking patterns shed light on the structures generating them. It has been shown that Icelandic case-marking patterns can distinguish, among other things, (i) verbal passives from adjectival passives and (ii) direct object datives from indirect object datives. These properties of the Icelandic case system make Icelandic an ideal testing ground for the analysis of ‘get’-passives. While it goes beyond the scope of the present article to develop a full analysis of ‘get’-passives across all of Germanic, we hope that the data and analysis presented in this article can be used to inform their analysis in other Germanic languages, and will provide some suggestions for this along the way.

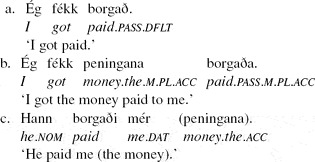

In this section, we provide a brief overview of several classes of ‘get’-passives, along with an analysis of them, before turning to a more detailed discussion in subsequent sections. The first class of ‘get’-passives is the ‘recipient “get”-passive’ (RGP). At first sight, RGPs seem to be derived from ditransitive verbs with dative indirect objects, such as senda ‘send’. The surface subject is interpreted as a goal or recipient, and the object is the theme. However, while dative indirect objects retain dative case under canonical passivization in Icelandic, as illustrated in (1b), dative arguments of verbs like senda ‘send’ seem to change from dative to nominative in ‘get’-passives, as illustrated in (1c).Footnote 2

(1)

Like the canonical passive, the passive participle agrees with its derived subject in number, gender and case when the latter is nominative or accusative, but takes default agreement (which is the same as the 3rd singular neuter form) when its derived subject is some other case, such as dative. In this introduction, we will fully gloss all passive participles, but in the remainder of the article, we will simply gloss them as ‘passive’ whenever agreement is not relevant. An analogous class of ‘get’-passive can be found in German, Dutch, and the other Scandinavian languages.

We take this ‘get’-passive to correspond to English sentences of the sort in (2a) rather than (2b). In the English construction in (2a), in order to get a recipient reading for the subject, a PP like to her, with her coreferential with the subject, is almost obligatory. In Icelandic, a PP is allowed, but not obligatory, as shown in (3).

- (2)

a. Maryi got the book sent ??(to heri).

b. Mary got sent the book.

(3)

The robustness of the recipient reading can be illustrated with a ‘pick-up line’ that exists in both English and Icelandic, but as a ‘get’-passive only in Icelandic.

(4)

In this case, a ‘get’-passive is very awkward in English; borrow is used instead (??I've lost my phone number, can I get yours loaned to me?/?I've lost my phone number, can I get loaned yours?). We discuss the properties and analysis of RGPs in Section 2.

The second class of ‘get’-passive, the ‘causative “get”-passive’ (CGP), involves a causative and/or agentive reading of the surface subject; this class seems to closely resemble English CGPs, except that it seems to be lexically somewhat more restricted, and the range of verbs which may appear in the CGP varies across speakers. Note that the case pattern of (5a) is like (1c). In (5b), the dative case assigned by the verb breyta ‘change’ is preserved; this case pattern is found in RGPs as well, as will be shown in Section 2.

(5)

The participle agreement facts are the same with the CGP as with the RGP. As for interpretation, the subject in the sentences in (5) is interpreted as a causer, or as an agent of the causing event. As far as we have been able to tell so far, Icelandic typically resists the purely benefactive reading that frequently shows up in English and other Germanic languages (including Scandinavian languages), and very strongly resists the maleficiary reading. Despite the ‘for’-phrase in (5a), the interpretation is that the subject is the agent and/or causer, not just the beneficiary. We discuss CGPs and the resistance to pure benefactive/malefactive readings further in Section 3.

Both RGPs and CGPs alternate with ‘anticausative “get”-passives’ (AGPs). AGPs involve the verb fá ‘get’ marked with the -st clitic that marks anticausatives (along with other varieties of the ‘middle voice’; see H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson1989:259–263, Anderson Reference Anderson1990, and Wood Reference Wood2012:64–77 on the various classes of -st verbs).Footnote 3 The thematic object of the embedded verb is then promoted to the matrix subject position.

(6)

(7)

Note that as in (5b)/(7a), the dative case assigned by breytt ‘changed’ is preserved in the AGP in (7b). Once again, the participle agreement facts are the same for AGPs as for RGPs and CGPs. AGPs are discussed further in Section 4.

For the final class of ‘get’-passive, which we will call ‘manage “get”-passives’ (MGPs), the term ‘passive’ might be a misnomer (though see Taraldsen Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010). This construction differs from the others in three ways. First, the verb form is that of a perfect participle rather than a passive participle, as evidenced by the fact that it never agrees in case, number and gender with the theme. Second, the meaning is active and agentive; that is, the surface subject is understood as the external argument of the participial verb. The meaning often comes close to English infinitival sentences headed by the verb manage, as in (8a), or has an ability modal reading, as in (8b). Third, the thematic object generally occurs to the right of its selecting participle, unlike the case with the other ‘get’-passives, where the object generally moves to the left of the participle.Footnote 4 Some attested examples of this construction are given in (8).Footnote 5

(8)

MGPs allow unergative intransitives, as shown in the following examples. (9a) is from a poem by Margrét Lóa Jónsdóttir.

(9)

The interpretive difference can be seen clearly when a verb like senda ‘send’ is used. Unlike in the RGP example in (10a), the subject of the MGP in (10b) cannot be construed as a recipient, but can only be the agent of the sending event.

(10)

For the purposes of the present study, we set aside the MGP, focusing instead on the cases where the participle is in the passive form, such as the recipient, causative, and anticausative ‘get’-passives.

We propose that RGPs and CGPs have a structure like (11), which illustrates (1c).Footnote 6 This structure is simplified in a number of respects, but it serves to illustrate some of the basic points we want to make about the analysis of ‘get’-passives. In Section 6, we make one kind of refinement to this structure, where we treat fá ‘get’ as a semi-lexical light verb rather than as a lexical verb. But the simplifications we make should not affect the main points in this article.

(11)

In this structure, the DP María is externally merged as the external argument of the verb fá ‘get’, which means that it starts in SpecVoiceP (following Kratzer Reference Kratzer, Rooryck and Zaring1996 and much subsequent work). SpecTP, the subject position, is filled when T0 attracts the closest DP to its specifier; in this case, this is María, so María moves to (or internally merges in) SpecTP. The verb fá head-moves to Voice0 and to T0, just as any verb in Icelandic does (and probably further, in most cases; see Angantýsson Reference Angantýsson2011 for a recent overview and empirical study). Fá ‘get’ is treated as an ECM verb, and its complement is a passive VoiceP, which we call ‘PassiveP’. The internal argument of the passive verb moves to the edge of PassiveP and then raises to SpecVP, as in Chomsky's (Reference Chomsky, Freidin, Otero and Zubizarreta2008) analysis of ECM as raising-to-object.

AGPs are derived by anticausativizing the transitive structure in (11). According to the analysis in Wood (Reference Wood2012), building on Schäfer (Reference Schäfer2008) and H.Á. Sigurðsson (Reference Sigurðsson2012a), this is done by merging an expletive clitic -st in the specifier of VoiceP, which prevents an external argument from merging there. The structure of (7b) is shown in (12). Here, for simplicity, we illustrate cliticization as simple right adjunction to the finite verb complex in T0.Footnote 7

(12)

Since the -st clitic occupies the external argument position, but cliticizes to the verb complex instead of moving to an argument position, the closest DP to T0 is the thematic object of the passive verb þessu ‘this’, so þessu moves to the subject position, SpecTP. We assume that this cliticization allows the internal argument to move past the SpecVoiceP position, similar to what is seen in the following French examples discussed by Chomsky (Reference Chomsky1995:305). The cliticization of French experiencer arguments, as in (13b), has been taken to license otherwise illicit A-movement of an embedded infinitival subject to the matrix subject position, as in (13a):

(13)

Richard Kayne (p.c.) reminds us that the French facts are more complicated than (13) alone indicates (as also mentioned in note 79 in Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995:388). We assume that the basic phrase-structural assumption is sound. That is, since -st does not distribute like (or is not licensed as) a full DP, it is not an intervenor for movement of full DPs; see McGinnis (Reference McGinnis1998:174ff.) and Anagnostopoulou (Reference Anagnostopoulou2003) for a more detailed discussion of A-movement past clitics.

In the next section, we look in more detail at the RGP construction, and defend the proposal that María in (1c) is externally merged as an argument of the matrix verb fá ‘get’, but that bókina ‘the book’ is merged lower, as the thematic object of the embedded passive verb.

2. THE RECIPIENT ‘GET’-PASSIVE

The recipient ‘get’-passive (RGP) has played a prominent role in cross-Germanic work on ‘get’-passives. In recent work, Alexiadou, Anagnostopoulou & Sevdali (to appear) studied case alternations between datives and nominatives, discussing German and Dutch alternations such as the German sentences in (14). This alternation resembles the Icelandic alternation seen earlier, repeated in (15).

(14)

(15)

Alexiadou et al. (to appear) propose that the nominative recipient subject in sentences like (14b) is base-generated in the same position as the dative indirect object in sentences like (14a).Footnote 8 Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010) proposes an analysis for Norwegian ‘get’-constructions which is similar in this respect. These analyses differ in the mechanisms invoked to account for the change in case from dative to nominative. Alexiadou et al. (to appear) propose that German dative is licensed by a feature of the external-argument–introducing Voice head, and that it is at the VoiceP level that dative case is absorbed in the ‘get’-passive. Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010), invoking case ‘peeling’ in the sense of Caha (Reference Caha2009) and Medova (Reference Medova2009), proposes that the dative case feature is stranded by movement; this feature stranding is then responsible for the verb spelling out as ‘get’.

However, there are several arguments supporting our proposal that the DP María in (15b) is not externally merged as an indirect object, followed by some mechanism that prevents it from being realized as dative. The first argument comes from a closer look at how case-alternations work in Icelandic. Under canonical passivization, dative objects remain dative when they move to the subject position (Andrews Reference Andrews1976, Thráinsson Reference Thráinsson1979, Zaenen, Maling & Thráinsson Reference Zaenen, Maling and Thráinsson1985, H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson1989, Jónsson Reference Jónsson1996).

(16)

(17)

However, while this is true of both dative direct objects, as in (16), and dative indirect objects, as in (17), there are important differences between direct object datives and indirect object datives (see Wood Reference Wood2012:131ff. for an overview and references). One difference involves the -st morphology seen above in (6)–(7). Accusative objects become nominative with both passive, as in (17b) and -st, as in (19b). However, when -st prevents a dative-assigning verb from merging an external argument, a direct object dative becomes nominative, as illustrated in (18), while indirect objects stay dative, as illustrated in (19) (H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson1989:270, Reference Sigurðsson2012a:220; Jónsson Reference Jónsson2000:89; Thráinsson Reference Thráinsson2007:290–292).Footnote 9

(18)

(19)

In fact, for ditransitive verbs such as úthluta ‘allocate’ and skila ‘return’, which take two dative objects, only the direct object dative becomes nominative; the indirect object remains dative. This is illustrated with the attested examples in (20b) and (21b), which would correspond to the constructed transitives in (20a) and (21a).

(20)

(21)

To account for this, Alexiadou et al. (to appear) propose that indirect object datives in Icelandic are assigned dative differently from both direct object datives in Icelandic and indirect object datives in German; specifically, they propose that indirect object datives in Icelandic are assigned dative inherently, such that the dative case cannot be manipulated by the Voice/v system.Footnote 10 It should now be clear why this analysis cannot extend directly to Icelandic ‘get’ passives: it would involve some part of the Voice system making an indirect object dative into a nominative, to account for (15) above, but this possibility has just been ruled out to account for (19)–(21).

Moreover, we can show that direct object datives can actually stay dative in the ‘get’-passive, again by looking at verbs which take two dative objects in the active form, such as úthluta ‘allocate’ in (22a). In the canonical passive, both datives remain dative, as illustrated in (22b). In the ‘get’-passive, however, the recipient surfaces in the nominative, but the theme retains its dative case, as shown in (22c). (22d) illustrates a simplified version of the example in (20b) (to facilitate comparison of the case patterns across constructions).

(22)

In order to maintain the analysis that the recipient and theme are merged in the same positions in (22a) and (22c), we would have to say that ‘get’ somehow absorbs indirect object datives but not direct object datives, while the anticausative middle in (18b)–(19b) absorbs direct object datives but not indirect object datives. This might be possible. However, there are at least two more arguments that the surface subject of RGPs and the indirect object of the corresponding active are not merged in the same position.

First, ditransitive verbs with obligatory indirect objects, as in (23a), do not form ‘get’-passives, as shown in (23b).Footnote 11 The examples in (24a–b) show that eigna ‘attribute’ may be passivized, but only if the indirect object dative is retained. Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Cardinaletti and Guasti1996:211) and Lødrup (Reference Lødrup1996:80) report the same facts for verbs with very different meanings in Norwegian, including bebreide ‘reproach’, frata ‘confiscate’, nekte ‘refuse’, and pålegge ‘impose on’; what these verbs share with Icelandic eigna ‘attribute’ is that their indirect object is obligatorily overt (and not any clear aspect of their meaning).

(23)

(24)

If ‘get’-passives like (15b) above involved A-movement from the indirect object position of the passive verb, it should be able to do so in (23b). If the surface subject of (15b) is an argument of fá, (23b) is ungrammatical because the obligatory argument of eigna ‘attribute’ is not projected. That is, the PassiveP is ungrammatical before fá ‘get’ is even merged, as schematizedin (25).

(25)

In fact, as expected, given (25), ‘get’-passives are possible under the causative reading if the dative is expressed overtly. For example, let's imagine we know a poet very well. However, we dislike or even hate her. We know about an unpublished poem by her, but no one else knows that she wrote it. After she dies, it gets very popular, and then we lie and say it was written by another poet (also dead). In this scenario, it is possible to say (26).Footnote 12

(26)

Thus, as long as the dative is expressed, the argument structure of eigna ‘attribute’ inside the PassiveP is satisfied, and a ‘get’-passive is possible. However, since there is a distinct recipient expressed within the PassiveP, it has a causative reading.Footnote 13

Second, certain ditransitives, in the passive, allow either the indirect object or direct object to move to the subject position, as shown in (27a) and (27b).

(27)

If ‘get’-passives simply involved A-movement with a distinct case-marking pattern, the recipient or theme should be able to move to the subject position; in fact, however, only the recipient may move there. In illustrating this, the expected pattern depends somewhat on one's analysis of case. However, no manipulation of case, word order, or agreement morphology results in a grammatical ‘get’-passive sentence with the theme in the subject position.Footnote 14

(28)

This would require an independent explanation if the nominative in (15b) were first-merged in the position of the dative in (15a), but follows from locality if the nominative is first-merged higher than the passive participle, as in (11) above. Locality conditions in a ditransitive structure can be devised such that either an indirect object or a theme can move to the subject position (see McGinnis Reference McGinnis1998, Platzack Reference Platzack1999, Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou2003, and Wood & H.Á. Sigurðsson to appear for distinct proposals), but such conditions cannot extend to the configuration in (11) to make the embedded theme able to move past the matrix external argument.Footnote 15

Note that this second argument does not extend in the same way to the proposal in Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010), where in order for the verb to spell out as ‘get’, it must be the dative argument that moves, stranding its [dat] feature through case peeling. However, the problem is that the peeling analysis of case has not, to our knowledge, been reconciled with the Icelandic facts showing that morphological case is in general dissociated from licensing position (see H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson2012a for recent discussion and references). For example, in the passive sentence in (27a) above, the dative indirect object A-moves to the subject position for (‘Case’-)licensing without stranding any dative feature; the nominative stays low, without any need to move and peel off case layers. In order for the analysis in Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010) to extend profitably to explain the data in (28), we need an account of when movement peels off case layers, when it does not, and why.

In sum, case alternation patterns in Icelandic make it difficult to maintain that the derived subject of a RGP is derived by A-movement from the indirect object position. Moreover, RGPs of ditransitives which take direct and indirect object datives show that fá ‘get’ has no problem occurring with a dative DP. The facts strongly suggest that the theme is merged as the object of the embedded passive verb, while the recipient is merged as an argument of the matrix verb fá ‘get’. We provide further arguments below that this is an external argument. First, however, we turn to a brief discussion of the CGP.

3. THE CAUSATIVE ‘GET’-PASSIVE

As mentioned earlier, the causative ‘get’-passive (CGP) also has the structure in (11) above. However, speakers vary somewhat as to which verbs may occur in the PassiveP complement of fá ‘get’. All speakers we have talked to find breytt ‘changed’ acceptable. Some speakers find the verb drepinn ‘killed’ odd or ungrammatical, while others find it acceptable; an attested example with drepinn ‘killed’ is given in (29a). Further attested examples of the CGP are given in (29b–c).

(29)

The structural properties of the CGP are much like (if not identical to) those of the RGP discussed in the previous section. For example, direct object datives are preserved if the embedded verb assigns dative; (30c) is thus like (22c).

(30)

If the verb assigns accusative in the active, then the object is accusative in the CGP; (31c) is thus like (15b).

(31)

As far as we have been able to tell, Icelandic seems to lack the so-called ‘adversity’ reading of ‘get’-passives seen cross-linguistically, such as English I got my car stolen, where the subject is not a cause or a recipient, but an adversely affected participant, or ‘maleficiary’. The sentence in (32) only has the odd, marginally available reading that the subject got someone to steal his/her own car. It does not have the most salient reading of the English sentence I got my car stolen, which is similar to ‘My car got stolen on me’.Footnote 16

(32)

It is less clear how robustly Icelandic lacks a purely beneficiary interpretation of the subject of a ‘get’-passive. In most examples we have looked at, it seems to be absent. In (31c), for example, the subject is clearly an agent or causer, whereas its English counterpart can easily have a reading where the subject simply benefitted from the door opening. However, there are contexts which may involve a beneficiary reading, such as in the following example:

(33)

The characterization and source of the restrictions on beneficiary and maleficiary readings will have to be left for future work.Footnote 17

It is worth pointing out that while many verbs strongly bias toward either a causative or a recipient reading, it is often possible to manipulate elements of the structure to bring out readings other than the most salient one. For example, senda ‘send’ can have a causative reading, especially if a different goal is named within the participle, as in (34); see also the discussion surrounding example (26) above.

(34)

The biggest difference between the CGP and the RGP is their interpretation, as well as the fact that there is no argument of the active (such as an indirect object) which intuitively corresponds to the subject of the CGP. However, if the proposal in the previous section is on the right track, then the apparent correspondence between the indirect object of the active in (15a) and the subject of the ‘get’-passive in (15b) is an illusion. The RGP is structurally just like a CGP, the difference being that the external argument is understood as a recipient. We discuss a possible explanation for this interpretive relation between the external argument of ‘get’ and the semantics of its PassiveP complement in Section 6.

4. THE ANTICAUSATIVE ‘GET’-PASSIVE

In previous sections, we have proposed that the surface subject of recipient and causative fá-passives is externally merged as an argument of ‘get’. In this section, we argue that the anticausative ‘get’-passive (AGP) supports the claim that this argument is an external argument. Haegeman (Reference Haegeman1985) proposed that English get-passives as in (35b) were derived as unaccusative or anticausative variants of get-causatives such as (35a).

(35)

Icelandic AGPs will be shown to support this analysis, but only when supplemented with the claim that English get-passives are ambiguous (Brownlow Reference Brownlow2011, Reed Reference Reed2011, Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2012), so that (35b) is not the only way to derive an English get-passive.

While most of the arguments we provided in Sections 2 and 3 show that the surface subject must be an argument of fá ‘get’, they do not necessarily show that this argument is an external argument. For English, it has been proposed that get is the unaccusative of give (Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky1995, Harley Reference Harley2002; the structure given in Richards Reference Richards2001:188 is much closer to the one we propose in Section 6). This is supported by the fact that it is difficult or impossible to passivize many uses of get; see Section 5 for further discussion of passives with fá ‘get’. That give and get share structure is supported by shared idioms, such as They gave me the boot ‘They fired me’ and I got the boot ‘I got fired’. In Icelandic as well, gefa ‘give’ and fá ‘get’ share idioms, such as in the following examples:

(36)

The idea that English get is unaccusative, however, faces some challenges, including the fact that it can occur as a ditransitive (He got me a present) and that it can pass agentivity tests. Icelandic fá ‘get’ can be agentive as well, in simple transitive and even some RGP readings, as illustrated in (37a–b). It can also be ditransitive, as illustrated in (37c).Footnote 18

(37)

In Section 6, we will propose a structure which captures the intuition that ‘give’ and ‘get’ share structure, but in which ‘get’ does take a structural external argument (and is thus not unaccusative). In this section, we discuss the relevance of the AGP to this claim.

In (38), we see an alternation similar to (35) above, except that the -st clitic is added to the verb fá ‘get’ in (38b). (39) presents attested versions of these kinds of examples.

(38)

(39)

The -st clitic is also involved in deriving anticausatives from transitives, as shown in (40a–b).

(40)

Dative case is assigned to þessu ‘this’ in (38) by the passive verb breytt ‘changed’, and is preserved under A-movement to the object position; this is just as in canonical ECM configurations, as illustrated in (41a). Eliminating the external argument with -st morphology for such verbs, as shown in (41b), has the same effect as in (38b), with the embedded argument moving to the matrix subject position.

(41)

Dative case is preserved in (41b) in the same way that it is preserved in (38b).

While it is true that -st morphology appears in a variety of syntactic configurations, the alternation such as in (38) is quite systematic, and clearly reflects the elimination of the external argument to derive a ‘raising-to-subject’ verb. As mentioned in the introduction, the same alternation can appear on RGPs as well.

(42)

Wood (Reference Wood2012), building on Julien (Reference Julien, Ramchand and Reiss2007:226–232), Schäfer (Reference Schäfer2008) and H.Á. Sigurðsson (Reference Sigurðsson2012a), proposes that the -st clitic in anticausatives is a thematic expletive occupying the external argument position syntactically, which prevents an external argument role from being assigned. This is illustrated for the sentences in (40) above in the tree diagrams in (43) (which are again simplified to some extent).Footnote 19

(43)

Combining the analysis of RGPs and CGPs in the previous sections with this analysis of the -st clitic results in the structure in (12) above, repeated here in (44).

(44)

The dative case and -st morphology in (38b) straightforwardly supports the notion that intransitive ‘get’-passives can be derived as anticausatives of causative ‘get’-passives: -st appears in the absence of an external argument, and the dative case shows that the surface subject has A-moved from the complement of the participle, just as in Haegeman's (Reference Haegeman1985) analysis.Footnote 20

Agentive ‘by’-phrases are possible in these constructions, but are, in many cases, better in the anticausative fást-passive than in the recipient or causative fá-passive; see, for example, (39c) above for an attested example. This seems to hold in English as well, again suggesting a relationship between the two constructions. Even in (45a), where a by-phrase is quite bad, the dative case on the theme shows unambiguously that we are dealing with a verbal passive, as will be discussed further below. Given this, the oddness of a ‘by’-phrase in the English CGP should not be taken as evidence against analyzing it as a verbal passive; rather, something about the interaction of the passive with the causative ‘get’ structure must be to blame; see also (46).

(45)

(46)

However, thematic differences between Icelandic fást-passives and English get-passives are now in need of an explanation. For example, the surface subject of Icelandic fást-passives, unlike English get-passives, cannot be construed as an agent (examples adapted from McIntyre Reference McIntyre2011).

- (47)

a. Mary got fired on purpose.

b. Mary got arrested by smoking weed.

(48)

This can be explained by the proposal of Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012), who, drawing on work by Fox & Grodzinsky (Reference Fox and Grodzinsky1998), Reed (Reference Reed2011) and others, proposes that English get-passives are ambiguous (see also Brownlow Reference Brownlow2011). They have a causative structure which embeds a null PRO, as in (49a), and a verbal and adjectival passive as in (49b) and (49c), respectively.Footnote 21 She suggests in note 3 that the causative structure in (49a) might alternate with causative get-passives like Samantha got John hurt, but otherwise does not discuss the causative get-passive. Our proposal, of course, is that the causative get-passive is a variant of (49b) rather than (49a).

(49)

The structure in (49a) allows the subject to be interpreted as an agent, as in (47). Here, Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012) is citing Lakoff (Reference Lakoff1971) and Lasnik & Fiengo (Reference Lasnik and Fiengo1974) for sentences like I think that John deliberately got hit by that truck, don't you?

While sentences of the sort in (49a) can have an agentive interpretation of the overt subject, Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012) notes that ‘get’-passives of the sort in (49b) tend to be judged unacceptable with purpose clauses and agentive adverbials identifying the implicit external argument, as in (50a). Reed (Reference Reed2011) and Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012) propose that this is not because they lack an implicit external argument; rather, it is because the get of get-passives is an achievement verb, and achievement verbs tend to be incompatible with agentive adverbials and purpose clauses; see (50b) below. Given the right context, adverbs and purpose clauses are, in fact, possible with get-passives, as shown in (50c); the same goes for many achievement verbs, as in the example in (50d).

- (50)

a. *The book got torn on purpose.

b. *Mary deliberately won the race today.

c. Professor A: Well, from what you're saying, that sounds like one long and boring meeting.

Professor B: Yes, and what really irks me is what intentionally didn't get discussed just to preserve the illusion that we all agree.

d. Secondly they deliberately won the world cup by maliciously playing better football than us.

(http://webspace.webring.com/people/lb/blackadderhomepage/specials_army_script.html)

This proposal, if correct, removes empirical barriers to the analysis of get-passives as involving a passive, verbal complement with an understood external argument. This is a welcome result, since the case-marking patterns in Icelandic indeed suggest that the complement is a verbal passive, as discussed further below.

At this point, we may note that Icelandic lacks the control structure in (49a). It cannot take a passive complement with a null subject and an agentive reading, as shown in (51) (where we test both nominative and accusative forms of the passive participle, given that we are testing a potential control structure; see H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson, Holmberg, D'Alessandro, Fischer and Hrafnbjargarson2008). We are not testing the -st version here since we have already shown that it cannot be an instance of the control structure in (49a).

(51)

So far, then, we can explain the difference between English sentences like (47) and Icelandic sentences like (48) by appealing to the ambiguity of English get-passives which is not shared by Icelandic fá(st)-passives. Icelandic fá ‘get’ does not have the control structure in (49a), and fást-passives such as in (48) are anticausatives and would be expected to correspond to the structure in (49b). That is, Haegeman's (Reference Haegeman1985) analysis is not wrong, it just does not apply to all strings of get plus a passive participle in English.

However, we can show that Icelandic also does not allow adjectival passive complements as in (49c). One very clear way to tell the difference between adjectival passives and verbal passives in Icelandic is to use a verb which assigns dative (or genitive) case to its object. Verbal passives preserve this dative and use a non-agreeing passive participle (referred to as the ‘default’ form, which is 3rd person singular neuter), whereas adjectival passives do not preserve the dative and use a passive participle which agrees with the derived subject in case, number, and gender (Benediktsson Reference Benediktsson and Hovdhaugen1980:115–117; Thráinsson Reference Thráinsson1986:44, Reference Thráinsson1999:42; Friðjónsson Reference Friðjónsson1987:79; H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson1989:334–335, Reference Sigurðsson2011; Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Manninen, Nelson, Hiietam, Kaiser and Vihman2006).

(52)

The contrast between (53) and (54) shows that only the verbal passive is possible as a complement of fá(st) ‘get’.

(53)

(54)

This is possibly related to the fact that Icelandic, again unlike English, does not allow adjectival complements of any kind, whether they are adjectival passives or not.Footnote 22

(55)

Drawing on work by Doron (Reference Doron2003) and Alexiadou & Doron (Reference Alexiadou and Doron2012), Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012) proposes that the difference between (49b) and (49c) above is not structural, but arises from the underspecified interpretation of a middle voice head, μ0, which can be either medio-passive, resulting in (49b), or anticausative, resulting in (49c); the verbal be-passive uses an entirely distinct passive voice head, π0. The choice between the two interpretations of μ0 is governed by several factors, including an interaction between properties of the verbal root and the middle voice head μ0; μ0 attaches directly to the verbal root and determines this interaction. For example, she proposes that the passive interpretation becomes available when an ordinary, canonical passive is not available (either for a particular verb or for an entire language).Footnote 23

This analysis does not seem to be available for Icelandic fást-passives. First, Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012) proposes that the middle head attaches directly to the verbal root, and that the root plus the μ0 head spell out as the participle. In Icelandic, the morphology of the participle seems to suggest that more structure is present. In Distributed Morphology (adopted by Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2012), a verb consists of a category-neutral root attached to a category-determining v0 head (see Arad Reference Arad2003, Reference Arad2005 for a thorough overview). In Icelandic, in addition to the participle morpheme, there are overt realizations of the v head (including -a, -ka, and -ga, among others), as well as one or more agreement morphemes spelling out case, number and gender. The case, number and gender morphemes could conceivably be added post-syntactically (McFadden Reference McFadden2004, Bobaljik Reference Bobaljik, Harbour, Adger and Béjar2008), but overt instances of v suggest that participles are built on verbs rather than roots.Footnote 24 Second, the verb fá ‘get’ itself occurs in the anticausative middle form (i.e. with the -st clitic). It seems implausible to say that fást spells out a light verb in the context of a middle voice head, especially since it is the middle -st form on its own that seems to have the ‘middle voice’ properties Alexiadou discusses (see, for example, (56b) below). Fást ‘get’, unlike English get, is not a good candidate for the spellout of a middle voice light verb, since it is so restricted in its uses; in fact, the limited scope of fást+participle in comparison to get+participle is what makes it an especially useful probe into the possible structures of ‘get’-passives, and the results of investigating its behavior seem to show that ‘get’-passives can be generated separately from the middle voice structures discussed by Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012). Third, as mentioned above, the fást-passive does not have the adjectival passive ambiguity that English get-passives do; it only takes verbal passives as complements.

There are some reasons to think, however, that Alexiadou's main insight – that certain English get-passives share a structure with middle voice structures – is on the right track. This would explain the fact that some verbs occuring with the middle -st clitic, such as those in (56b), are naturally translated into reflexive get-passives in English. Such cases are reflexive in interpretation, not in morphology: John gets dressed is interpretively similar to John dresses himself. As shown in (56a), these roots cannot form ‘get’-constructions in Icelandic. Note that all of the Icelandic examples (56a) involve adjectival passive participles except for vanur ‘used to’, which is a simple adjective sharing a root with the verb; note also that several cases correspond to English participles that do not form active verbs at all (with the same meaning) (e.g. get engaged, get used to it).

(56)

This supports Alexiadou's view that English get is a semi-lexical verb which, in English, can spell out structures that other languages spell out with the middle voice morphology. Crucially, however, the overall picture seems to suggest that there exist verbal get-passives which are structurally distinct from middles.

The simplest analysis of the Icelandic fást-passive is that it is the anticausative of the causative or recipient fá-passive: it involves merging -st in the external argument position (preventing an external argument from merging there), thus prompting the promotion of the internal argument of the passive verb to the subject position. For this account to go through, we must accept that the surface subject of RGPs and CGPs originates as an external argument of fá ‘get’. This analysis suggests that in English, too, an AGP derivation should be among the legitimate get+participle constructions. That is, the Haegeman analysis was correct, but only for a subset of English get-passives. In the next section, we address a question that arises under the proposal that the surface subject of RGPs and CGPs originates as an external argument: can ‘get’ be passivized in such structures, and if not, why not?

5. PASSIVES AND THE ‘NEW IMPERSONAL PASSIVE’

The appearance of -st in sentences like (38b) supports the analysis of RGPs and CGPs as involving an external argument, since it is the external argument that is removed by -st in causative alternations. What remains unexplained is why it is impossible (or highly degraded) to form a personal passive, as in (57).

(57)

In this section, we note that (i) this is not limited to ‘get’-passives, (ii) there is some variation in the acceptability of examples like (57), and (iii) there are other constructions which do suggest an external argument for RGPs and CGPs.

Turning to the first point, the problem of passivization seems to be a general one for ECM verbs with very small complements. For example, the verbs help, let, have, see, and hear resist passivization with bare infinitive (possibly VoiceP-sized) complements.

- (58)

a. I helped him attack his friend.

b. *He was helped attack his friend

- (59)

a. I let him attack his friend.

b. *He was let attack his friend.

- (60)

a. I had him attack his friend.

b. *He was had attack his friend.

- (61)

a. I saw him attack his friend.

b. *He was seen attack his friend.

- (62)

a. I heard him attack his friend.

b. *He was heard attack his friend.

These verbs (with the notable exception of have, which, however, may passivize in idioms such as A good time was had by all) generally allow passivization in other contexts, often with similar meanings and/or similar θ-roles assigned to their subjects, so something other than the base-generated position of the subject is presumably at issue.Footnote 25

- (63)

a. He was helped by his mother.

b. He was let into the club by the bouncer.

c. He was seen by everyone.

d. He was heard by everyone.

Second, there is variation in the acceptability of passives of ‘get’-passives. In mainland Scandinavian languages, -s passives are possible on få ‘get’-passives (though not analytic ‘be/become’-passives).Footnote 26

(64)

Halldór Sigurðsson (p.c.) responded to (57) by saying that it was not necessarily fully out for him. He provided the following example:

(65)

Not all Icelandic speakers agree on the judgment of this example. However, in English too, there turns out to be speaker variation; there are attested examples, such as those in (66), which improve in acceptability quite a bit, especially when be is itself in the perfect participle form.

- (66)

a. In the past 50 years, no student had died in a fire but in the past 20 we know how many have been gotten killed in school shootings.

(http://www.newswest9.com/story/14925643/school-shooting-training-at-misd?clienttype=printable)

b. The thing is, if the 17 year old had been gotten killed by someone speeding and texting everyone would be crying on his facebook saying that the driver deserves the death penalty or something.

c. Sorry to say this, but religion has been and always will be a source of business to get money. In the medieval times, you would have been gotten killed if you didn't want to get turned to god's side, now the situation is gladly different.

d. it's not that i don't trust guys but i've just been gotten hurt so many times, that i think i kinda give up with guys.

(http://nutsyriri.blogspot.com/2011/05/girl-just-speak_22.html)

Since these are examples from the web, some caution is of course warranted; however, what is striking about these examples is that for the second author and a number of other English speakers we have consulted, they are surprisingly natural. Other speakers judge them as unacceptable. This kind of variation suggests that we do not want to analyze ‘get’-passives in a way that rules out ‘double passives’ in principle; whatever is responsible for the general unacceptability of passives with sentences such as in (58)–(62) above could be behind the frequent unacceptability of passivizing CGPs and RGPs. Note that some of the paradigms in (58)–(62) are also subject to speaker variation; in particular, according to Johnson (Reference Johnson2011), examples like (61b) are acceptable in his Appalachian English.

Third, it is possible to form a ‘New Impersonal Passive’ (NIP) of the RGP/CGP, as shown in (67b).Footnote 27 The NIP is a recent syntactic innovation of modern Icelandic (though see H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson2011:153 fn. 5 for some skepticism of its recency) in which a passive-like construction has several clustering properties distinguishing it from canonical passives, such as lack of A-movement to subject position even for definite pronominal DPs (often resulting in a first-position expletive það), preservation of structural accusative case, and lack of agreement on the participle. (The percentage sign indicates speaker variation.)

(67)

According to one line of analysis, the NIP is not really a passive construction at all, in the sense that there is a syntactically active null pro argument (Sigurjónsdóttir & Maling Reference Sigurjónsdóttir and Maling2001; Maling & Sigurjónsdóttir Reference Maling2002, Reference Maling, Sigurjónsdóttir, King and de Paiva2013, in press; Maling Reference Maling, Lyngfelt and Solstad2006). If this is correct, then the NIP facts do not say anything about the present proposal one way or another. However, H.Á. Sigurðsson (Reference Sigurðsson2011) and E.F. Sigurðsson (Reference Sigurðsson2012) propose that this null argument is generated as a syntactic external argument as part of the Voice system, which, if correct, would support the present analysis of RGPs and CGPs in the same way that -st morphology does (see also Ingason, Legate & Yang Reference Ingason, Legate and Yang2012 and Schäfer to appear).Footnote 28 According to another line of analysis, there is no null argument in the NIP, the idea being that the NIP is just like canonical passives in this respect (Eythórsson Reference Eythórsson and Eythórsson2008, Jónsson Reference Jónsson, Alexiadou, Hankamer, McFadden, Nuger and Schäfer2009). If so, then (67b) still supports the present analysis, since it shows that passivization is possible in principle (as expected if there is an external argument), and that it is (57) that is in need of an independent explanation. For now, we will leave (57) unexplained and note that for a variety of analyses of the NIP, (67b) supports the present analysis of fá ‘get’ as taking an external argument.

In sum, there are three reasons that (57) does not undermine the analysis of RGPs and CGPs as taking an external argument. First, there are other ECM constructions with external arguments that do not allow passives. Second, there is variation in the acceptability of passivizing recipient and causative ‘get’-passives. Third, there are other constructions, including anticausative ‘get’-passives and the NIP (under at least two analyses), which support the external-argument analysis.

6. WHAT IS ‘GET’?

The analysis presented so far has treated fá ‘get’ as a lexical verb that can take a passive verb phrase complement. This, however, would be a rather exceptional property for a lexical verb. In addition, it has trouble explaining the fact that idioms are shared by ‘get’ and ‘give’, as discussed in Section 4 (see the examples in (36)). It also treats as an accident the fact that ‘get’, cross-linguistically, has similar multiple uses; it is presumably these multiple uses which at least in part lead us to translate verbs like fá as ‘get’ (rather than ‘receive’, etc.). The uses of fá ‘get’ in (68) all have analogues in English, for example. (The labels used here are informal.)Footnote 29

(68)

This range of uses suggests that fá ‘get’ should be treated as a semi-lexical light verb. Within the framework of Distributed Morphology, this means that it is the spellout of a little v head in some context, rather than the spellout of a root attached to a little v head. Drawing in part on the work of Freeze (Reference Freeze1992) on possessive ‘have’, an influential proposal by Kayne (Reference Kayne1993) argues that various uses of ‘have’ verbs cross-linguistically are derived by the assumption that the verb ‘have’ is the spellout of a verb like ‘be’ with an incorporated determiner or preposition.Footnote 30 Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Cardinaletti and Guasti1996, Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010) has extended this idea to Scandinavian ‘get’, proposing that it spells out a functional complex including a light verb ‘become’ and a preposition or applicative head.Footnote 31 Here, we will propose, like Taraldsen (Reference Taraldsen, Duguine, Huidobro and Madariaga2010), that the surface subjects of (transitive) ‘get’-passives are thematic arguments of an Appl(icative)0 head in the sense of Pylkkänen (Reference Pylkkänen2002, Reference Pylkkänen2008), Cuervo (Reference Cuervo2003) and Schäfer (Reference Schäfer2008), among others. Unlike Taraldsen, however, we take this to be essentially a ‘high’ Appl0 in the ‘get’-passive construction, one which takes the PassiveP as its complement directly.

The proposal is as follows. Paying attention only to the functional structure, and ignoring lexical roots, the syntactic structure for both the CGP and RGP is as in (69). Here, Appl0, v0 and Voice0 form a morphosyntactically complex head, and one of the terminals will spell out as ‘get’ in this context (see Svenonius Reference Svenonius2012 and H.Á. Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson2012b:379 for related alternatives).

(69)

When this structure is interpreted, v0 introduces the eventive interpretation; following Reed (Reference Reed2011) and Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2012), the relevant ‘flavor’ of v will be/yield a causative achievement verb. Appl0 may introduce an applied θ-role, the interpretation of which is determined on the basis of the PassiveP complement. Voice0 may introduce an agent role, or may be semantically null. When Appl0 and Voice0 both introduce a role, the result will be an interpretation where the external argument is both the agent of the causing event, and the bearer of the applied role. This is the case for sentences like (37b), repeated in (70), where the purpose clause shows that the recipient is also understood as an agent.

(70)

When only Appl0 introduces a role, the interpretation will be that the subject in SpecVoiceP bears only the applied role, and is not an agent. This is the case for pure recipient readings of sentences like (1c), repeated in (71).

(71)

The most salient reading of (71) is that María is just a recipient, and not an agent (though some speakers do find the agentive reading natural). When Appl0 introduces a beneficiary role and Voice0 introduces an agent role, the result is the causative reading: the subject in SpecVoiceP is understood as the agent of the causing event, but also a beneficiary of the caused event. This is the case for causative readings with no recipient such as (5b), repeated in (72).

(72)

In this analysis, the puzzle mentioned in Section 3, namely why Icelandic is so restrictive in the availability of the non-agentive beneficiary/maleficiary reading, amounts to the question: Why does Voice0 have difficulty being semantically null when the applied role is benefactive/malefactive?Footnote 32 Finally, in the anticausative, when -st is in SpecVoiceP, neither Voice0 nor Appl0 introduces a role, since there is no DP to bear it. This is not possible when a full DP occupies SpecVoiceP because something has to integrate the interpretation of that DP into the interpretation of the structure.Footnote 33

We turn now to some consequences of implicating a high Appl0 in the analysis of RGPs and CGPs. First, Appl0 generally has the property that the thematic role it introduces is a relation dependent on the properties of the complement. High Appl, for example, often introduces beneficiaries or maleficiaries in transitive sentences. Very often, however, the applied argument is construed as a possessor if possible.

(73)

In (73a), the applied dative is a beneficiary as well as a possessor of the wound, and in (73b) the applied dative is the possessor of the glasses as well as the maleficiary. This is exactly what has been reported for recipient ‘get’-passives and causative ‘get’-passives. In (74b), the nominative subject is the possessor of the eyes as well as the beneficiary.

(74)

In Cook's (Reference Cook, Hole, Meinunger and Abraham2006) LFG analysis, such ‘free datives’ are added via an argument structure operation in the lexicon. She takes it to support her analysis in that the embedded lexical item must be adjusted in order to match and fuse with the argument structure of ‘get’, since ‘get’ needs a beneficiary. In the present proposal, if the analysis of Icelandic extends to German, the element used to add the extra dative in (74a) is present in (74b), so it is expected to share thematic properties across constructions.Footnote 34

Second, high Appl does not combine well with unergatives. Thus, it is ungrammatical to add an applied dative to an unergative intransitive as in (75a). This also holds for ‘get’-passives, which are not acceptable with plain impersonal passives of unergatives.

(75)

Note that the complement of Appl0 need not always have a structural thematic object; that is, the ungrammaticality of (75b) cannot be attributed to the need for the embedded verb to take an overt object. This is shown by verbs where, as Lødrup (Reference Lødrup1996:85) points out for Norwegian, ‘an implicit object is enough to get the passive interpretation’. Lødrup (Reference Lødrup1996) gives (76) as an example:

(76)

The same holds in Icelandic, where a very common example is with the verb borga ‘pay’; note that while the implicit object of (77a) can be mentioned explicitly, as in (77b), it does not seem to be syntactically active, in that the participle takes the default agreement form rather than an agreement form betraying the properties of the implied object. (See Wiese & Maling (Reference Wiese and Maling2005) for relevant phenomena.) Note that the recipient of the verb borga ‘pay’ can be an applied indirect object, as in (77c), but that the theme is optional here as well.

(77)

The data in (77) show that the explanation for (75b) cannot have anything to do with some requirement for overt syntactic transitivity. Instead, it seems to amount to the evaluation metric of Appl0 on its complement: for some reason, Appl0 is not able to add an applied role to unergatives, and this holds in (75a) as well as (75b); for borgað ‘paid’, on the other hand, the semantics of PassiveP makes it straightforward for Appl0 to be interpreted as introducing a recipient role.

In this section, we have proposed that Icelandic fá ‘get’ is a semi-lexical light verb, a complex predicate which consists of a Voice0 head, a v0 head, and an Appl0 head. The v0 head introduces eventive semantics (making ‘get’ a causative achievement verb). The fact that ‘get’ and ‘give’ can share idioms stems from the presence of Appl0 in both. Moreover, at least two aspects of ‘get’-passives can be explained on the hypothesis that they involve an Appl0 head attached directly to the PassiveP complement. Like with high applicatives, there is a strong bias toward a possessive/recipient interpretation and attachment to unergative activities is ungrammatical. The fact that a recipient is not always entailed, as in the CGP, suggests that this bias, rather than a low applicative structure, is responsible for recipient semantics in RGPs. However, we presented in previous sections evidence that the argument of ‘get’ is an external argument. This is explained by taking Voice0 to be present to introduce the external argument syntactically and add the possibility of an agentive interpretation for the subject as well. The properties of ‘get’-constructions thus emerge from the interaction of independently-needed functional elements, rather than from stipulated properties of a lexical verb.

7. SUMMARY

In this article, we have used the following two properties of the Icelandic case-marking system to probe the structure of ‘get’-passives: (i) dative objects remain dative in the verbal passive, but not the adjectival passive; and (ii) indirect object datives do not become nominative under middle -st morphology, while direct object datives do (see especially (20) above). The first property shows that Icelandic ‘get’-passives are verbal passives and the second raises difficulties for the possibility of analyzing ‘get’-passives as involving A-movement from an indirect object position. We provided further support for the view that the nominative subject of RGPs and CGPs is an argument of ‘get’. The availability of the ‘New Impersonal Passive’, under some analyses, further suggests that the nominative is an external argument. The appearance of the -st clitic on AGPs supports the external argument analysis as well, and moreover supports the analysis of intransitive ‘get’-passives as unaccusatives of transitive ‘get’-passives (provided we accept that English get-passives are ambiguous, so that this is not the only analysis of them). Finally, we provided an outline of how the present analysis might be linked to a decompositional view of verbs like ‘get’ which treats them as semi-lexical light verbs consisting of several functional heads which form complex predicates in the semantics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Halldór Sigurðsson, Stephanie Harves, Richard Kayne, Joan Maling, Florian Schäfer, and three anonymous reviewers for providing comments on earlier drafts of this paper which have led to significant improvements. Thanks to Jeff Parrott for encouraging us to write this paper. Thanks also to Eefje Boef, Eiríkur Rögnvaldsson, Hlíf Árnadóttir, Tricia Irwin, Jóhannes Gísli Jónsson, Itamar Kastner, Kuo-Chiao Lin, Inna Livitz, Terje Lohndal, Neil Myler, Marcel Pitteroff, Joel Wallenberg, Linmin Zhang and Vera Zu for helpful discussions of the material in this article. We take responsibility for any remaining errors. Our names are listed in alphabetical order.