1. INTRODUCTION

Bare nouns, often described in contrast with nominal determination, definiteness and partitivity, have always been a central subject of inquiry and interpretation in the linguistic literature, both cross-linguistically and within grammatical studies of single languages.

In its treatment of bare nouns, the Danish linguistic tradition has focused especially on incorporation (Nedergaard Thomsen Reference Nedergaard Thomsen1991; Herslund Reference Herslund1994, Reference Herslund, Schøsler and Talbot1995; Asudeh & Mikkelsen Reference Asudeh, Mikkelsen, Cann, Grover and Miller2000; Nedergaard Thomsen & Herslund Reference Nedergaard Thomsen, Herslund, Thomsen and Herslund2002; Petersen Reference Petersen2010, Reference Petersen, Hansen and Widell2011, Reference Petersen, Borchmann, Hougaard, Togeby and Widell2013; Hansen & Heltoft Reference Hansen and Heltoft2011), while the phenomenon as such, understood as the syntactic and semantic implications of bare nouns in a broader perspective, has been left relatively untouched (see, however, traditional works which mainly focus on genericity, see Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen1975[1911]; Hansen Reference Hansen1927; Hansen & Lund Reference Hansen and Lund1983 and Hansen Reference Hansen2001[1994]).

Against this background, the present paper will cover two main areas. First, it aims to give an account of the distributional differences between Bare Plural count nouns (BPs) (or mass nouns) and Bare Singular count nouns (BSs) in Danish and, second, to discuss whether BPs and BSs in object position show identical or different syntactic and semantic properties, and to what extent they can be considered to pseudo-incorporate under the verb.

The first part of the paper seeks to substantiate the general claim that BPs have a much wider distribution than BSs. It is shown that BPs can occur in both pre-verbal and post-verbal subject position, as well as in object position, and that they are not subject to limitations with respect to the aspectual classes of the verbs with which they combine. Moreover, it is argued that BPs in subject position can receive both generic and existential interpretations, dependent on the specific context, while in object position their reading as either generic or so-called modificational NPs is disambiguated by prosodic prominence, i.e. main vs. weak stress, of the verb. This means that BPs, in fact, can obtain three distinct meanings: generic, existential and modificational.

By contrast, the distribution of BSs turns out to be strongly restricted in comparison with that of BPs. The paper will provide evidence for the claim that syntactically BSs cannot occur in pre-verbal or post-verbal subject position, and that in object position they only permit a modificational, not a generic or an existential, interpretation. Despite the fact that there is no one-to-one correspondence between lexical-aspectually defined verb classes and the licensing of BSs in object position, the data analyses conducted in the study clearly reveal that the internal temporal structure of the verbal events – in the form of durativity – has significant bearing on whether a given V+BS structure is considered felicitous. However, to capture acceptability variation within structures headed by accomplishment and stative verbs, the notions of availability and possession seem to provide the extra explanatory factor needed to account for these empirically attested inter-class contrasts.

It is a consequence of the distributional analysis that BPs and BSs with modificational meaning actually coincide in object position of activity verbs, as well as subsets of verbs of accomplishment and stative verbs. Viewed in the light of these results, the second part of the paper will focus on analysing similarities and differences between V+BP and V+BN structures from the perspective of pseudo-incorporation (PI).

In present-day linguistics the term incorporation has been expanded to cover phenomena that go beyond the creation of verbal compounds with the structure [NV]V or [VN]V through morphosyntactic absorption of the unmodified N0-component by the V-component (see e.g. Booij Reference Booij2009:5). However, it is evident that bare nominals in argument position cross-linguistically, both in the form of BSs, BPs and bare mass nouns, share a number of features which are usually said to characterise nominals which incorporate morphosyntactically under V (Stvan Reference Stvan2009). They lack the properties of free nominals (Mithun Reference Mithun1984, Reference Mithun1986; Klaiman Reference Klaiman1990) in the sense that they are not preceded by left peripheral nominal functional categories, such as case, articles, quantifiers, demonstratives or possessors (Massam Reference Massam2009), but at the same time they allow (albeit to a limited extent) certain kinds of modification (Massam Reference Massam2001, Borik & Gehrke Reference Borik and Gehrke2015a), for instance by means of adjectives, as well as separation from V. The following examples from Danish attest to these facts:Footnote 1

-

(1)

In (1a) the BS is directly juxtaposed to the V, while sommerhus ‘holiday cottage’ in (1b), apart from being a compound noun, i.e. an NP, is separated from V by the modifying adjective nyt ‘new’ and the adverb desværre ‘unfortunately’. (1c) illustrates that inverted (question) V–S word order systematically implies that the bare object NP is split from the V by the subject.

Consequently, the term PI (pseudo-incorporation) will be used in this paper to refer to the process by which an NP, which may or may not be separated from the V, ceases to be a free nominal, under standard assumptions a DP, or a full-fledged argument in the terms of Farkas & de Swart (Reference Farkas and de Swart2004), as it is deprived of its functional categories. According to Borik & Gehrke's (Reference Borik and Gehrke2015a) comprehensive introductory article on the syntax and semantics of PI, the label of PI has been applied to the study of bare noun constructions in a number of languages (for a non-exhaustive list, see Borik & Gehrke ibid.:11 note 5), but it does not show strict uniformity in its use across languages, and in many cases it seems to share semantic properties with neighbouring phenomena such as e.g. weak referentiality. For instance, typical cases of Danish BSs will translate into German and English structures with indefinite or definite articles – see e.g. the contrast between spille violin and its English translation ‘play the violin’ – and have a number of, but not all, semantic features in common with them. However, in spite of different language-specific characteristics typically related to the degree of bareness of the pseudo-incorporated noun, discussions of PI, regardless of the specific language(s) under scrutiny, seem to revolve around some central morphosyntactic and semantic properties which are common to this construction type across languages, namely modificational and word order restrictions, narrow scope, number neutrality, discourse opacity/transparency, predication and predicate types, nameworthiness, prosody and telicity (see also Dayal Reference Dayal2003, Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015). In the following, I will discuss these factors to the extent that they are relevant to Danish V+BP/BS structures, and I will apply the notion of PI to the study of the Danish data in accordance with how PI is dealt with in, for instance, Dayal (Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015) and Borik & Gehrke (Reference Borik and Gehrke2015a).

Specifically in Danish, the lack of realisation of nominal functional categories entails that V+BS and V+BP structures gain the shared properties of narrow scope, fixed V+ BP/BS word order (Hansen & Heltoft Reference Hansen and Heltoft2011), unit accentuation (Rischel Reference Rischel1983) and atelicity (Nedergaard Thomsen & Herslund Reference Nedergaard Thomsen, Herslund, Thomsen and Herslund2002), along with showing identical patterns as regards fronting, dislocation and pronominal representation (see a selection of relevant references concerning the manifestation of these properties in different languages in Booij Reference Booij2009:4 and Massam Reference Massam2009:170). These joint properties generally distinguish V+BP/BN structures from weak referentiality structures with indefinite or definite articles and, thus, easily lead to the assumption that V+BP/BN structures form a coherent linguistic category. Yet, at the same time, systematic differences can be detected between V+BPs and V+BSs with respect to the pseudo-incorporated noun's possibility of modification, its function as antecedent of anaphoric reference, as secondary predication pivot and as focus element in sentence transformations, as well as its number interpretation.

It will be argued that these differences in terms of both form and meaning specification correlate with a progressive integration between the V and the NP in three subtypes of PI, namely (i) PI of BPs (low degree of integration as in Per skriver breve ‘Peter writes letters’), (ii) PI of type 1 BSs (medium degree of integration as in Per vasker bil ‘Per is washing (his/the) car’), and (iii) PI of type 2 BSs (maximum degree of integration as in Per spiller violin ‘Per plays (the) violin’). Accordingly, the key objective of this part of the paper is to show that PI in Danish is not an absolute phenomenon, but can be conceptualised along a continuum, where at one end the noun is clearly grammatically restricted and at the other has a freer (but still constrained) role in syntax and semantics.

The paper is structured into three parts. In Section 2, it is verified on the basis of correlations between syntactic position, generic vs. non-generic readings, prosodic cues and aspect that BPs have a wider distribution than BSs. Section 3 shows that BPs and BSs with so-called modificational meaning coincide in object position of activity verbs and stative verbs that induce the implicature of possession. However, despite their distributional equivalence, V+BP and V+BS structures have a number of both shared and divergent properties, which leads to the suggestion of an integration continuum based on PI. In Section 4, the main conclusions of the paper are presented and a general discussion is provided of potential analyses of the facts described in the paper.

2. DISTRIBUTIONAL FACTS ABOUT BARE NOUNS IN DANISH

Danish bare nouns can occur in three positions (the status of the nominal as BP or BS is disregarded here): (i) in argument position as subjects or objects, (ii) in predicate position as subject or object predicates, and (iii) as arguments of prepositions, illustrated in (2)–(4).

-

(2)

-

(3)

-

(4)

However, bare predicate nouns and bare noun arguments introduced by prepositions fall outside the scope of this paper, which focuses exclusively on bare nouns in subject and, in particular, object position.

The main purpose of this section is to show that BPs and BSs exhibit a significantly different distribution and, therefore, cannot be analysed in the same way.

2.1 Bare plurals (BPs) in argument position

In Danish, BPs (and mass nouns)Footnote 2 can appear freely as both pre-verbal and post-verbal subjects as well as in object position of all types of verbs, as in (5)–(8).

-

(5)

-

(6)

-

(7)

-

(8)

As is common across the Germanic languages (see e.g. Adger Reference Adger2003), Danish is a strict V2 language in which the finite verb goes in verb second position and can only be preceded by one single constituent. This means that the subject of any main clause will move to a post-verbal position if another constituent, e.g. an adverbial, an object, etc., is fronted. However, this is a strictly syntactic mechanism that has no bearing on the main interpretations of clauses as either categorical or thetic (for a discussion of these basic sentence types, see e.g. Ladusaw Reference Ladusaw, Harvey and Santelmann1994), where the prototypical word order is as indicated in (5) and (6), respectively.

Basically, Danish BPs in subject position either activate a generic or an existential interpretation. In subject position of contextually unrestricted categorical sentences, BPs systematically receive a generic reading, see e.g. (5), while a particular contextual setting can induce an existential reading. For instance, the embedding of (5) under a matrix clause which restricts the domain of reference to a specific situation, as in [Jeg har set [krokodiller drukne deres bytte]] ‘I have seen crocodiles drown their prey’ clearly would lead to an existential reading. In thetic constructions with the locative subject marker der ‘there’ as formal subject, as in example (6) above, BP subject nouns must occur in post-verbal position – independently of whether the subject is an internal argument (an unaccusative intransitive subject) or an external argument (an unergative intransitive subject) – and, thus, obligatorily acquire an existential interpretation, since the locative der ‘there’ is considered to be an existential preform whose function is to introduce new information into the discourse (Hellberg Reference Hellberg1970). This analysis is corroborated by the fact that definite NPs, which, other things being equal, typically refer to known entities, are not licensed in der-constructions, compare the contrast between (9a) and (9b), and that the passive of factive verbs (in the sense of Kiparsky & Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Jakobovits and Steinberg1971) when taking a complementiser phrase are incompatible with der, compare (10a, b) (Hansen Reference Hansen2001[1974]).Footnote 3 The rationale behind this lies in the assumption that factive verbs presuppose knowledge that is already part of the discourse record, while non-factive verbs assert new information (Hansen ibid.:128). The subordinate complement clause embedded under the factive verb beklage ‘regret’ in (10b) constitutes presupposed knowledge and, thus, corresponds to the known entities referred to by the definite NP in (9b), while the content of the subordinate complement clause embedded under the non-factive verb påstå ‘claim’ in (10a) is asserted as new knowledge and, therefore, corresponds to the new entities referred to by the indefinite NP in (9a). In other words, there is a clear correspondence between presupposed and asserted complement clauses, on the one hand, and definite and indefinite NPs, on the other.

-

(9)

-

(10)

As object complements, BPs are consistent with both a generic and a modificational interpretation, where the latter term indicates that the BP modifies the V by restricting its denotation so that the V+BP structure names a subkind of the activity or state denoted by V (see e.g. Dayal Reference Dayal2011). This ambiguity of reference between generic and modificational interpretations is mediated extra-syntactically on the basis of prosodic prominence of the verb, compare the examples in (11a–c).Footnote 4

-

(11)

The V+DP structure in (11a) and the generic V+BP structure in (11b) show identical prosodic patterns in the sense that the V and the object are stressed individually. By contrast, the V+BP expression in (11c) has unit accentuation with weak stress on the verb. This means, in principle at least (exceptions occur), that the BP in (11b) refers to all the members of the set denoted by katte ‘cats’, whereas an adequate paraphrase of (11c) would be that the subject referent does cat training or is a cat trainer, which, of course, does not imply training of the whole set of cats in the world. Consequently, in (11c) the V+BP expression 0 dressere | katte designates a specific subkind of training, namely the one that involves cats. In this case, the BP is not referential or existential, but rather it attributes a property to V and, therefore, functions as an event modifier, see Dayal's (Reference Dayal2011) account of PI.

Left-dislocation configurations provide further evidence in support of recognising a fundamental distinction between BP objects with generic and modificational interpretations, respectively. Example (12a) illustrates that the topic element, whether it is a DP or a generic BP, is linked to a resumptive anaphoric pronoun, dem ‘them’, which shows number agreement with the dislocated object. Example (12b) contrasts with (12a) in that the dislocated topic object has a non-generic meaning, i.e. a non-referential, modificational function with respect to V and, consequently, is doubled by the neuter pronoun det ‘that.n’ (see also later discussion).

-

(12)

Following Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2010, Reference Josefsson2012) for Swedish, also the Danish pronominal reference system in the third person distinguishes between S(yntactic) and R(eferential) pronouns. The S-pronouns den ‘it.c(ommon)’ and det ‘it.n(euter)’ – whose plural forms de/dem ‘they.nom/ them.acc/dat’ are unmarked for gender – agree in formal gender and number with an antecedent NP in the preceding discourse, while the R-pronoun det, which can be realised either as a stressed strong form (corresponding to English that) or an unstressed weak form (corresponding to English it), makes no number or gender distinctions. On the basis of the assumption of a privative opposition between S- and R-pronouns, Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2012:134–135) convincingly argues that while S-pronouns convey a bounded reading of the referent, which is very likely to be interpreted as an individual or token (although the type reading is not excluded), the R-pronoun conveys the meaning that the referent is not bounded and, hence, cannot be an individual or a token, which by pragmatic inference leaves the type reading as the only interpretation available. So, according to Josefsson's analysis, the R-pronoun det, in fact, has very little inherent meaning of its own. It lacks a number feature and, therefore, it can make reference to all kinds of arguments devoid of boundaries, such as substances, events and propositions (see Josefsson Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2010, Reference Josefsson2012), and also actively trigger a reading of unboundedness in cases of underspecification.

Following these insights, det in (12b) can then be interpreted as an R-pronoun, which – by virtue of R-pronouns not having a number feature – imposes a non-referential type perspective on the dislocated BP object antecedent biler ‘cars’. As I see it, this is compatible with regarding the BP as a modifier which restricts the set of events referred to by the V to a subset of events with the property ascribed by the BP.

The contrasting examples in (13a, b) below show, once again, that DPs and generic BPs behave similarly in terms of accepting passive transformation, while it seems difficult for modificational BPs to be subjects of passives.

-

(13)

The data presented in this section lead to two main considerations. First, they indicate that BPs themselves are not inherently generic, existential or modificational. As we have seen, their interpretation depends on the parameter of syntactic position in combination with the use of the locative subject marker der ‘there’ and prosodic prominence of the verb. Second, the data show that BPs with generic reference side with DPs with respect to being licensed in pre-verbal subject position, generating identical prosodic patterns in object position, and pronoun doubling in connection with object left-dislocation. This means that generic BPs in all respects must be considered referential, i.e. they refer directly to kinds of individuals, and, therefore, do not constitute good candidates for forming part of PI constructions. From a PI perspective, only BPs of the type exemplified in (11c) comply with the criterion of not linking directly to a referent in the discourse. Instead, as we have seen, they have the function of narrowing down the type of activity denoted by the V and in that way they create a closer bond with the V, which is characteristic for PI (see Dayal Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015; Borik & Gehrke Reference Borik and Gehrke2015a).

2.2 Bare singular count nouns (BSs) in argument position

Apart from special types of discourse such as proverbs (kvinde er kvinde værst ‘lit.: woman is woman worst’ [a woman is a woman's worst enemy], newspaper headlines (politimand dræber demonstrant ‘policeman kills demonstrator’), titles of pictures (kvinde leger med barn ‘woman plays with child’], etc., in Danish the pre-verbal subject position is not available for BSs, see (14) (see also Müller Reference Müller2014).Footnote 6

-

(14)

In general, they cannot appear in post-verbal subject position of unergative or unaccusative verbs either, e.g. (15a, b), but there are certain exceptions.Footnote 7

-

(15)

The occurrence of BSs in object position correlates with the aspectual properties of the verb with which they combine.Footnote 8 In this position, Danish BSs are allowed, as a general rule, with what is usually referred to as activity verbs (following the event model of Vendler Reference Vendler and Vendler1967 and his definitions of dynamicity, durativity and telicity); see (16) below.Footnote 9 These predicates are dynamic, durative and atelic, i.e. they denote events which involve iterated changes, imply a continuous, undefined duration – in cognitive terms something homogeneous or unbounded (Kearns Reference Kearns1991) – and have no inherent endpoint built into them. In contrast with BPs, BSs in object position never obtain a generic interpretation.

-

(16)

Moreover, some verbs of accomplishments, which only differ from activity verbs on the telicity parameter, allow BSs in object position, as seen in (17) below. Lexically, bygge ‘build’ describes an event whose duration in time potentially leads to an endpoint, namely when the process culminates in a resulting state of the (incremental) Theme argument (Dowty Reference Dowty1991). Therefore, such verbs are telic.

-

(17)

However, other verbs, which clearly also express accomplishments, seem less prone to accept BSs in object position. This contrast is illustrated in example (18), where nedrive ‘demolish’ describes the opposite event of bygge ‘build’ in (17).

-

(18)

This variation within the group of accomplishment verbs is probably related to the general asymmetry between constructive accomplishment predicates, which imply the coming into existence or appearing on the scene of the Theme argument as a result of the event, and non-constructive accomplishment predicates, which imply the cessation or disappearance of the Theme argument as a result of the event, and presuppose the existence of this argument prior to the occurrence of the event (Grimshaw & Vikner Reference Grimshaw, Vikner, Reuland and Abraham1993). Crucially, Grimshaw & Vikner (ibid.:146) emphasise that the change of state triggered by the constructive predicates ‘makes the element undergoing the change available in a way that it was not available before’, and it is most probably this availability of the Theme to the subject referent that renders an example like (17) felicitous, while the non-availability of the Theme to the subject referent implied by the non-constructive predicate in (18) has the opposite effect. Furthermore, as will be elaborated in more detail below, the factor of availability can be seen as a prerequisite for the implicit or explicit possessive relation that seems to license object BSs with certain stative verbs.

In contrast to accomplishment verbs, the lexical aspectual classes achievement verbs and so-called semelfactive verbs (in the sense of Comrie Reference Comrie1976) show internal consistency. Both systematically reject BSs in object position, see (19) and (20). Crucially, these two aspectual verb classes differ from activity and accomplishment verbs in that they are not durative. They denote punctual events, i.e. events that only take a moment in time.

-

(19)

-

(20)

One of the most basic aspectual distinctions is the one between stativity and dynamicity. Without taking into consideration possibilities of event-type shifts, it is customary to distinguish fundamentally between, on the one hand, activity, accomplishment, achievement and semelfactive verbs, which denote different types of dynamic events, and state verbs, which express non-dynamic qualities or properties. Put differently, stative predicates, such as verbs conveying meaning related to senses (hear), sentiments (hate), desires (want), possession (have), etc., essentially do not imply transitions, while dynamic predicates do (Dowty Reference Dowty1979, McClure Reference McClure1994).Footnote 10

With respect to stative verbs, the general rule seems to be that they do not accept BSs in object position, here exemplified in (21) by the perception verb høre ‘hear’.

-

(21)

However, in contrast to the general pattern in Danish, BSs in object position are actually licensed by certain stative verbs, namely predicates that induce an availability implicature between the subject and object argument, which very often by virtue of pragmatic inference triggered by the bareness of the noun leads to a possessive interpretation. For instance, the last example of (22) Ana bruger stok ‘Ana uses (a) stick’ suggests that a stick is available to her in some sense, but, unlike its non-bare counterparts, the BS also implicates a possessive relation, i.e. leads to an enrichment of meaning (see de Swart & Zwarts Reference de Swart and Zwarts2009). Henceforth, I will refer to this as a possessive interpretation. Here and in the following examples, the double slash indicates separation of sentences or expressions consisting of several words, while a single slash separates individual words.

-

(22)

Cross-linguistically, it is not an uncommon phenomenon that BS objects are licensed by verbs from which a relation of possession can be distilled (see e.g. Borthen Reference Borthen2003 for Norwegian; Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam & Espinall Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam, Espinal, Tasmowski and Vogeleer2006 and Dobrovie-Sorin Reference Dobrovie-Sorin2009 for Romanian; Espinal & McNally Reference Espinal, McNally, Kaiser and Leonetti2007, Reference Espinal and McNally2008, Reference Espinal and McNally2011 and Espinal Reference Espinal2010 for Spanish and Catalan).

Thus, in this perspective, it becomes apparent why a verb of accomplishment like bygge ‘build’ allows object BSs, whereas its counterparts expressing a converse semantic relationship, i.e. nedrive ‘demolish’, refuses, or at least is reluctant to accept, this option, see (17) and (18) above. While the verb build implicates availability of something as the result of a construction process, a similar relation of availability between subject and object referents cannot be inferred on the basis of the verb demolish. Furthermore, the bareness of the noun in the structure bygge hus ‘build (a) house’, following the argumentation above, produces an implicature of a possessive relation. In this way, the parameter of possession can be said to also affect the ability of accomplishment verbs to combine with BSs, at least indirectly.

3. SHARED AND DIVERGENT PROPERTIES OF V+BPs AND V+BSs

3.1 Shared properties

The following treatment of example material will make it evident that V+BP and V+BS structures have a lot in common. Specifically, in Danish they share the properties of obligatory narrow scope, fixed V+BS/BP word order, unit accentuation and atelicity.

3.1.1 Scopal relations

It is well documented across an array of languages (see e.g. Carlson Reference Carlson1977a, Reference Carlsonb for English, Dobrovie-Sorin & Laca Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Laca and Godard2003 for examples from Spanish, Italian and Romanian, and Dayal Reference Dayal2011 for Hindi) that the scopal (non-)specificity of BSs and BPs differs from that of singular indefinites in the sense that the former only allow a scopally non-specific or narrow scope interpretation, whereas the latter are ambiguous with respect to inducing a scopally non-specific or specific reading, i.e. narrow vs. wide scope interpretation, compare (23a, b).

-

(23)

(23b) is ambiguous between two interpretations, one which corresponds to ‘there is a horse we consider buying’, where the singular indefinite in object position takes wide scope with respect to the predicate and refers to a specific horse, and another which can be paraphrased into ‘we consider buying any horse’, where en hest ‘a horse’ is within the scope of the predicate. (23a) can only be interpreted as ‘we consider buying any horse or plurality of horses’, i.e. the bare nominals are unambiguously confined to having narrow scope in relation to the predicate.

These observations concerning (non-)specificity and scope relations are by many researcher (see e.g. Borik & Gehrke Reference Borik and Gehrke2015a and Dayal Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015, and references therein) taken to represent a cross-linguistic stable property of (pseudo)-incorporation with respect to expressions of negation, modality and quantification, which invariably operate on the full expression, never partially on some of its elements. The fact that the bare nouns have non-specific reference and remain under the scope of the predicate, i.e. they stay within the VP because they are void of functional elements that could motivate their movement out of the VP (see also Dobrovie-Sorin et al. Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam, Espinal, Tasmowski and Vogeleer2006), could be interpreted as an indication that BPs and BSs in object position function as property denoting modifiers of V, rather than ‘real’ arguments denoting individuals (see Dayal Reference Dayal2011:146). According to Dayal (ibid.), this is also in keeping with the idea that the pseudo-incorporated nominals do not denote individually, but form a unit with the verb, which denotes a subevent of the events referred to by the V (recall also the discussion earlier in the paper).

3.1.2 Word order

Under normal conditions of intonation and prosody, BSs and BPs can occur in post-verbal position only, which is in opposition to full arguments, compare the examples in (24a, b).

-

(24)

The example in (24a) shows that BSs and BPs cannot be fronted under normal conditions, while the DPs bilen/bilerne ‘the car/the cars’ in (24b) accept this type of operation.Footnote 11

In Danish, it is possible to dislocate BSs and BPs to the left, but then they must be followed and referred to by the neuter pronoun det ‘that.n’, irrespective of the formal gender and number of the noun in question, while DPs are doubled by gender and number agreeing pronouns (recall the previous discussion in Section 2.1. above). In (25a, b) this contrast is illustrated by the common gender noun bil ‘car’ occurring in left-extraposition in its two bare forms and as DPs, respectively.

-

(25)

In line with what was suggested by the aforementioned scopal relations, these constraints on BS and BP fronting, as well as left-dislocation structures with respect to pronominal non-agreement with antecedents, are indications that both BSs and BPs do not have the status as free arguments, but should rather be seen as modificational elements tightly linked together with the verb. They are not subject to individuation by pronominal reference and their left-dislocation cannot take place without an indication (provided by the neuter pronoun det ‘that.n’) that the ‘prescribed’ phrasal V–O word order has been violated. Accordingly, also the parameter of word order seems to provide evidence for regarding Danish V+BP/BS structures as instances of PI, rather than just some kind of ‘irregular’ case of sentential standard complementation.

3.1.3 Prosody

It has been long recognised in the linguistic literature about Danish that prosodic cues are related to syntactic structure in the way that if the NP does not carry a determiner, the V is unstressed, and vice versa (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1934; Diderichsen Reference Diderichsen1946; Rischel Reference Rischel1983; Hansen & Lund Reference Hansen and Lund1983; Nedergaard Thomsen Reference Nedergaard Thomsen1991; Scheuer Reference Scheuer1995; Petersen Reference Petersen2010, Reference Petersen, Hansen and Widell2011, Reference Petersen, Borchmann, Hougaard, Togeby and Widell2013; Hansen & Heltoft Reference Hansen and Heltoft2011). Consequently, the parameter of stress groups together BSs and BPs in object position, and distinguishes V+BS/BP from V+DP structures, compare the examples in (26a, b) (see also the discussion of examples (11a–c) above).

-

(26)

The phenomenon of unit accentuation, i.e. when a lexical item is reduced prosodically and is followed by another lexical item with full stress as in (26a) above, is an indication that the elements enter into a tight syntactic and semantic relation. A prerequisite for unit accentuation is 0X . . . | Y word order (Hansen & Heltoft Reference Hansen and Heltoft2011:338), meaning that the weak stress element (the verb) must occur before the full stress element (the noun), which should be considered in connection with the observations made above concerning fronting and left-dislocation constraints. Semantically, unit accentuation implies that V+BS/BP structures denote specific (sub)types of activities – that is to say that, for example, playing the violin and reading the newspaper are special ways of playing and reading. This status as complex units of meaning can be illustrated as follows: Maria [[spiller] simplex verb [violin] NP ] complex predicate ‘Maria plays (the) violin’, and is in accordance with Dayal's (Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015) definition of PI in Hindi, which predicts that Vincorp. takes a property denoting noun as modifier and in this way forms a unit denoting what she refers to as a ‘unitary action’ (Dayal Reference Dayal2011:146), where the bare noun restricts the scope of the V to a subtype of the V's denotation (see also discussion in Section 4 and previous comments).

3.1.4 Telicity

It has been stated many times that the nature of the internal argument affects the interpretation of the event denoted by the predicate (see e.g. Verkuyl Reference Verkuyl1972, Krifka Reference Krifka, van Benthem, Bartsch and van Emde Boas1989) with respect to telicity, or in cognitive linguistics terms boundedness. Unlike DPs, BSs and BPs are not capable of stimulating a telic interpretation of verbs which are not lexically specified for telicity. The transformation of the object from DP to BP/BS illustrated in the examples (27a, b) concurrently causes an aspectual disambiguation, meaning that the V+BP/BS structures denote an activity, instead of an accomplishment, semantically compatible with atelic adjuncts such as hele dagen ‘all day’ that express duration of time, but conflicting with telic adjuncts that express a fixed time span such as på en dag ‘in a day’. The hashtag mark ‘#’ indicates that the sentence is semantically anomalous.

-

(27)

Nevertheless, some V+BS/BP expressions actually give the impression of being ambiguous between a telic and an atelic interpretation, compare (28) and (29) below, although the V-element is clearly an activity verb with no inherent specification of an endpoint. As we can see, the (a)telicity interpretation of (28) and (29) appears to be disambiguated through the use of durative vs. time-span adverbials.

-

(28)

-

(29)

However, this (a)telicity ambiguity is only apparent and can be explained as being the result of the distinction between inner and outer aspect (for a thorough discussion of these concepts, see e.g. Pustejovsky Reference Pustejovsky1991, Smith Reference Smith1991, Travis Reference Travis, Tenny and Pustejovsky2000). Crucially, the outer aspect coding triggered by the telic adjunct på fem minutter ‘in five minutes’ delimits the events themselves in the sense that the relevant activities of care-washing and tooth-brushing take place within a time span of five minutes, but has no bearing on whether the events culminate in a completion in the form of a resulting state. In other words, the events described in (28) and (29) are non-incremental (in the sense of Dowty Reference Dowty1991), and hence atelic, because the affected arguments, or rather BP/BS modifiers, cannot be considered to undergo a change-of-state, irrespective of whether a durative or time-span adverbial is used.

On the other hand, there is no denying the fact that the versions of (28) and (29) with telic adjuncts are likely to lead to incremental interpretations where the BS/BP referents experience a change-of-state, as the V+BS/BP expressions in question refer to stereotyped situations we normally associate with an end-point. Car-washing, tooth-brushing, etc. usually bring the object referents from one stage to another, from dirty to clean, but this change-of-state reading is due to pragmatic inference, not to the semantics of the linguistic structures, which inherently convey an atelic meaning. Consequently, a clear distinction has to be made between inherently atelic constructions which due to outer aspect encoding by a telic adjunct, such as på fem minutter ‘in five minutes’, lead to a change-of-state reading on pragmatic grounds, and inherently telic constructions which are telic due to the measuring out effect of the DP (Krifka Reference Krifka, Sag and Szabolcsi1992), i.e. inner aspect encoding, as in (27a).

This aspectual discussion becomes especially relevant when we consider constructions formed by accomplishment verbs in combination with bare noun effectum objects (Filmore Reference Fillmore, Bach and Harms1968:4), see (30).Footnote 12

-

(30)

Here, in line with what was the case in (28) and (29), the atelic durative adjunct hele året ‘all year’ encodes the predicate as an activity, but the time-span adjunct på et år ‘in a year’ implies that the event invariably has an endpoint which corresponds to finishing a house or a non-specific number of houses at the rate of one each year. This means that when V describes an event of accomplishment and, thus, is specified for telicity, and its object is incrementally achieved by the verbal action, the status of the internal argument with respect to determination does not have a final disambiguating effect on the aspectual interpretation of the event. In other words, the BS/(BP) and DP version of Dan byggede hus/et hus på et år ‘Dan built house/a house in one year’ are neutralised with respect to telicity as they both culminate in a resulting state, i.e. the finishing of a house. So, in opposition to (28), (29) and similar examples, in the case of (30) the time-span adjunct på et år ‘in a year’ consistently entails a telic reading, independently of pragmatic inferences.

Finally, consider the following example, where an endpoint is imposed on the events of violin-playing and TV-watching through the use of the auxiliary få ‘get’ and the past participle form of the verbs spille ‘play’ and se ‘watch’:

-

(31)

These bare noun expressions contrast with vaske bil ‘wash car’, bygge hus ‘build house’, etc. in that they can never be interpreted incrementally, as the BS referents of violin and TV are understood as existing antecedently to the subject referent's activities and, even more importantly, as unaffected by them. Violins and TVs do not end up in a new state by being played at and watched. Furthermore, the relevant BSs show defectiveness with respect to number and determination when occurring in the expressions in question, as in the semantic anomaly of e.g. *spille violin-en ‘play violin-det’ and *se TV’-er ‘watch television-pl’ (see Petersen Reference Petersen, Borchmann, Hougaard, Togeby and Widell2013 for the view that the similar expression spille klaver ‘play (the) piano’ is a backformation from the nominal compound klaverspil ‘piano-playing’).

Contrary to what seems to be the prevailing line of thought among linguists studying bare nouns in object position in Danish (see e.g. Asudeh & Mikkelsen Reference Asudeh, Mikkelsen, Cann, Grover and Miller2000, Nedergaard Thomsen & Herslund Reference Nedergaard Thomsen, Herslund, Thomsen and Herslund2002; Hansen & Heltoft Reference Hansen and Heltoft2011) (and to a large extent also in other languages, see references in note 9), V+BS/BP structures do not unambiguously denote activities (or states), although this is undoubtedly the most common tendency.Footnote 13 We have seen that the inner aspectual encoding of V+BS/BP structures can be affected by different linguistic manifestations of outer aspect, and that their impact with respect to achieving a change-of-state reading of the bare noun referent varies according to the nature of the constitutive parts of the specific expression. There is a gradual difference from expressions that maintain their inner aspectual reading as activities, irrespective of outer aspectual coding, such as spille violin ‘play (the) violin’, across expressions whose bare noun referent can be read incrementally given the right contextual circumstances, such as vaske bil(er) ‘wash (the) car(s)’, to expressions where outer aspectual telic elements inevitably trigger a resultative state reading, as in bygge hus(e) ‘build (a) house(s)’.

These observations on telicity support the general claim presented in the introduction of the paper that there is ample reason to suggest that V+BS/BP structures, when applying finer-grained analytical lenses, actually come in different subtypes of PI. Specifically, on the basis of the analysis conducted above we can draw a line between PI structures which unconditionally convey an atelic meaning (spille violin), and PI structures which to varying degrees are susceptible to outside influences with respect to their aspectual meaning (vaske bil(er), bygge hus(e)). What was referred to in the introduction as type 2 BSs, consequently, due to their morphological defectiveness and their syntactic ‘inertness’ show a higher level of integration or unification with V than is the case for BSs of type 1 and BPs.

3.2 Divergent properties

Just as it appeared evident that BSs and BPs share an array of properties, it will become equally clear from the following sections that they also differ from each other in terms of possibilities of modification, construction of secondary predications, discourse referential properties and number neutrality.

3.2.1 Modification

An issue that clearly illustrates the difference between BSs and BPs in object position is the wider modification possibilities of BPs compared to BSs. BPs can be freely modified by qualitative and descriptive adjectives (including postponed past participles), whereas BSs are generally incompatible with this type of modification, as seen in the contrast illustrated in (32a, b) (see also Müller Reference Müller2014, where the examples come from).

-

(32)

Moreover, object BPs can be modified by non-restrictive relative clauses, as in (33a), while such clauses cannot function as modifiers of nominal heads in the form of BSs in object position, as in (33b).

-

(33)

These facts suggest that BSs have a less independent role in syntax than BPs, which can function autonomously from V as individual referents. So, even though a unified PI analysis at first could seem as a rational solution for the description of V+BN/BP structures when only taking into account the shared properties treated in Section 3.1, we see that bareness alone is not a sufficient criterion for forming an unambiguous category. Rather, the distinction between BSs and BPs results in different degrees of integration, or PI, between V and NP.

3.2.2 Secondary predication construction

The difference between BPs and BSs is further corroborated by the fact that object BPs can be small clause subjects of predicative APs in causative constructions – often referred to as resultative small clauses (see e.g. Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra1988, Doetjes Reference Doetjes1997) – whereas BSs cannot fulfil this function.Footnote 14 In (34) this contrast is illustrated on the basis of a structure whose matrix verb, in root clauses, license both BSs and BPs in object position.

-

(34)

Another, perhaps less robust, contrast between BPs and BSs relates to the observation that while object BPs are always fully compatible with locative PP-modifiers, seen in (35a) below, locative PPs functioning as modifiers of object BSs are only acceptable when they specify places or locations which are denotatively included in the subject referent through a part–whole relation, as in (35c). If the locative PP-modifiers specify places which cannot be defined as parts of the subject referent, as in (35b), they appear semantically odd.

-

(35)

In (35b) the referents of the PP-complements skuffen ‘the drawer’, æsken ‘the box’ and garderoben ‘the wardrobe’ are not denotatively included in the subject referent hun ‘she’, while lommen ‘the pocket’, fingeren ‘the finger’ and hovedet ‘the head’ in (35c) can be said to specify parts of their corresponding whole represented by the subject referent.Footnote 15

3.2.3 Cleft sentences and passive

Examples (36) and (37) below show that BSs cannot appear in cleft sentences and as subjects of the passive, i.e. move away from their natural post-verbal position, while this is totally unproblematic for BPs.Footnote 16

-

(36)

-

(37)

On the basis of the observations made so far, we can conclude that in general object BPs are open to syntactic manipulation, i.e. they can be accessed by sentence constituents that usually require some sort of discourse prominence of the elements they modify or predicate something about (see also Espinal & McNally Reference Espinal and McNally2011). By contrast, BSs seem inaccessible to the external syntax and, thus, behave more like lexical components which form a tight union with V and, to a certain extent at least, are subject to principles of lexical integrity (Anderson Reference Anderson1992). So, once again, we observe that the degree to which an NP is pseudo-incorporated into V varies according to whether it is explicitly marked as plural, or not.

3.2.4 Anaphoric reference and predicate type

The discourse transparency-opacity status (in the sense of Farkas & de Swart Reference Farkas and de Swart2004) of pseudo-incorporated nominals is a complex and somewhat controversial issue, as it is sensitive to a number of factors, such as e.g. aspectual information (Dayal Reference Dayal2011), number marking (Dayal Reference Dayal, Matthews and Strolovitch1999; Farkas & de Swart Reference Farkas and de Swart2004) and type of anaphor (Borthen Reference Borthen2003), and, at the same time, seems to vary quite substantially across languages. That said, (38) and (39a, b), where, as well as in relevant subsequent examples, antecedents and anaphors are marked in boldface, show that apparently BSs and BPs in Danish can function as both token and type antecedents (see also Borthen's Reference Borthen2003 description of Norwegian for similar observations). As far as the type interpretation is concerned, this is further corroborated by the fact that they are equally acceptable in left-dislocated focalising contexts, where they are both doubled by the R-pronoun (type-anaphora) det ‘that.n’, see also (25a) above.

-

(38)

-

(39)

In (38), the common gender BS bil ‘car’ functions as antecedent of both the S-pronoun den ‘it.c’ and the R-pronoun det ‘that.n’, and (39a, b) show that the common gender BP grise ‘pigs’ can also be referred back to by both types of pronouns (see previous discussion on the distinction between S- and R-pronouns). So, this suggests that there is, in fact, no difference between BSs and BPs in terms of anaphoric reference. However, if we change the sentence from describing a static event, as in (38) and (39a, b), to expressing an episodic event, as in (40a, b), it appears that BSs and BPs differ from each other.

-

(40)

Even though neither BSs nor BPs can be considered ideal antecedents of S-pronouns (in comparison with DPs), i.e. they don't lend themselves that easily to an interpretation as tokens, the examples above suggest that BPs are poorer antecedent candidates of S-pronouns than BSs in similar contexts.Footnote 17 At the same time, we can observe that BPs function well as antecedents of R-pronouns in contrastive contexts, where they receive a type reading due to the unboundedness reading signalled by R-pronouns, whereas parallel constructions with BSs are (close to) incoherent, compare (41) and (42).

-

(41)

-

(42)

Without performing a complete analysis of the ability of BSs and BPs to serve as antecedents, it seems safe to assume that BSs tend to be less acceptable as antecedents of R-pronouns, and more acceptable as antecedents of S-pronouns, while for BPs the situation is the opposite. However, this does not imply that object BSs denote tokens and object BPs types, only that these are the interpretations that are most easily triggered by anaphoric pronouns.Footnote 18

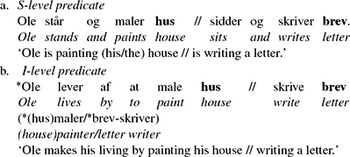

This type/token interpretation distinction corresponds very well with the fact that V+BS structures are only compatible with S(tage)-level (episodic) predicates, while V+BP structures both match with S-level and I(ndividual)-level (static) predicates (Carlson Reference Carlson1977a, Reference Carlsonb), although the static reading is probably the most likely in these cases. Examples (43a, b) illustrate that the predicate type serves as a distinctive feature in acceptability judgments of V+BS structures.

-

(43)

If the answer to the question Hvad laver Ole? ‘What is Ole doing?/What does Ole do?’ is Han maler hus ‘He paints (his/the) house’, we understand that the subject referent is engaged in an activity which is true of a temporal stage, whereas the answer Han maler huse ‘He paints houses’ can be interpreted both as a true description of an activity which lasts a certain amount of time, or as something which holds true throughout the existence of the individual Ole and, therefore, tends towards being read as what he does for a living (see also Petersen Reference Petersen, Hansen and Widell2011 and Müller Reference Müller2014).

The possibility of establishing either anaphoric type or token reference to pseudo-incorporated BPs and BSs is strongly related to the S-level vs. I-level compatibility distinctions presented above. The transitory property of the subject denoted by S-level predicates places the subject referent in a specific spatio-temporally bounded situation, which provides a reasonable contextual basis for inferring the possible existence of a specific referent of the object BS. It is this potential specificity reading of the BS which is activated by the S-pronoun den in e.g. (40a), and which also makes the BS less acceptable as antecedent of an R-pronoun, as in (42), which, as we have seen, activates a type reading of the noun. By contrast, V+BP structures like male huse ‘paint houses’ tend to express generalisations over a large number of recurring stage level events or situations and, thus, function as I-level predicates which express habituality (see Manninen Reference Manninen2001:3). Consequently, in these contexts the BP components are not likely to be interpreted as referring to specific entities and, therefore, they are generally reluctant to accept S-pronouns as anaphors, even in cases where the event is delimited by a time adverbial like hele dagen ‘all day’, as in (40b). On the other hand, an expected consequence of the iterative habituality context is that the BP elements perform well as antecedents of R-pronouns, which stimulate a type reading of the nominal, see e.g. (41) above. So, as we can see, the demonstrated difference between BSs and BPs as regards anaphoric reference seems to connect to a larger explanatory system where the parameters of static vs. episodic events as well as type of predicate play a significant role.

Finally, drawing a line back to the previous section's discussion on telicity, the expressions which firmly reject the resultative state reading of the BS under any circumstances of outer aspect, e.g. spille violin ‘play (the) violin’, are compatible with both I-level and S-level predicates, see (44).

-

(44)

This last observation contributes to understanding that, apart from differences of reference between BSs and BPs and their semantic effects, there is good reason to take into account two types of V+BS structures represented by spille violin ‘play (the) violin’ and male/bygge hus ‘paint/build (a/the) house’, respectively. The fact that V+BN structures like spille violin are actually underspecified as to the semantic distinction between predicate types clearly suggests that in these cases the nominal, i.e. a so-called type 2 BS, cf. previous comments in Section 3.1.4. above, plays a less autonomous role with respect to influencing the interpretation of the expression. Consequently, this finding contributes to supporting the assumption that spille violin represents the PI subtype which shows a maximum degree of integration (see also the previous discussions in Section 1 as well as in Section 3.1.4. and Section 3.2.1. on different subtypes of PI forming a progressive continuum of integration between V and BP/BS). Moreover, this view is further corroborated by the analysis of number presented in the following section.

3.2.5 Number (neutrality)

From a syntactic perspective, Danish BSs are clearly singular since they only license modification by singular adjectives, can solely be referred back to by singular pronouns, are incompatible with collective predicates, and enforce singularity on the subject when they occur in predicate position; consider the following examples (see Borthen Reference Borthen2003 for similar observations on Norwegian):

-

(45)

On the other hand, it is also clear that plural implication contexts of various sorts can make BSs compatible with non-atomicity entailments, i.e. interpretations that involve a plurality of individuals; consider (46)–(48). According to Farkas & de Swart (Reference Farkas and de Swart2003:14) compatibility with atomicity as well as non-atomicity entailments coming from the predicate or from the context is what defines number neutrality.

-

(46)

-

(47)

The plural subject in (46) implies that there must be several apartments, most probably one for each family. Likewise, in (47) the locative PPs på Mallorca, i Sverige og på Vestkysten ‘on Mallorca, in Sweden and on the West Coast’ trigger an understanding of several houses.

This, of course, raises the important question of what is the interpretational difference between the plurality reading of object BSs obtained via circumstantial inference and the plurality reading of BPs, which are morphologically marked as plural. Consider the following two examples with BPs in object position in relation to (46) and (47) above:

-

(48)

-

(49)

In the case of (46) and (47), we are likely to infer a distributive reading of the predicate, meaning that there is one flat for each family, and one house corresponds to each of the places mentioned, while the cumulative reading of the predicate (Krifka Reference Krifka, Sag and Szabolcsi1992), i.e. one which implies that one or more families want more than one flat, and that more houses are built in one or more of the locations, is very improbable, but perhaps cannot be ruled out completely. By contrast, (48) and (49) are true only of situations in which the subject referent looks for several flats in each place and builds several houses in each place, respectively, i.e. the examples must be read cumulatively. This contrast is further corroborated by the example in (50).

-

(50)

As the first sentence activates the default reading that the BS lejlighed ‘flat’ refers to one atomic individual, it is consistent with the second sentence where the disjunctive pair enten/eller ‘either/or’ introduces an exclusive relation, but inconsistent with the third sentence in which både/og ‘both/and’ indicates a relation of inclusion and, thus, forms a plurality.

The observation that BSs are compatible with interpretations that involve a plurality of individuals, but only if the specific reading of the predicate qualifies as distributive, not cumulative, makes them directly comparable to overtly marked indefinites in this respect; consider the following examples, where the two types of structures are neutralised in terms of their number reading:

-

(51)

From this we can deduce that the default reading of a BS is that it has atomicity of reference, but that this atomicity, by context, can be extended to cover different singular entities, i.e. a distributive reading of the predicate is possible, while the cumulative one seems inaccessible. This corresponds well with the fact that BSs are syntactically singular, as seen in (45a–d) above, meaning that their structural singularity status can be coerced semantically, but still permeates through to the interpretational level.

However, also in this respect the V+BS structures of the type spille violin/se TV/køre lastbil ‘play (the) violin/watch TV/drive lorry’ stand out as being insensitive to different interpretations of number. These structures are truly number-neutral in the sense that contextual factors of the sort discussed previously in connection with the former examples have no influence on the interpretation of the BS, which bears no specification or has any traces of the number category.

Consequently, one of this paper's central claims, namely that two distinct subtypes of V+BS PI can be identified in Danish, finds additional support in the observation that type 1 BSs differ from type 2 BSs also in terms of number neutrality. On a more general level, this means that the present analysis does not consider number neutrality to be a defining characteristic of PI in Danish. Rather, as we have seen, it can be regarded as a gradable phenomenon which varies according to the specific V+BN construction in itself and, in broad terms, the number implicatures invoked by the context.Footnote 19

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The data analyses presented in this paper show that while the distribution of BSs is limited to the object position of a restricted subset of verbs, BPs can occur in both subject and object positions of all kinds of verbs, but with different interpretational effects.

Typically, in subject position BPs receive either a generic or an existential reading. The generic reading of an example like Krokodiller drukner deres bytte ‘Crocodiles drown their pray’ can be represented as follows, where ‘∀Gen’ is a quasi-universal quantifier that allows exceptions: ∀Genx[crocodiles(x) → drown_their_pray(x)]. Roughly, this translates into ‘in general, every crocodile drowns its pray’, where, for simplicity, the complex predicate drown their pray is treated as a simple, unanalysed one-place predicate (for a formal study of genericity, see Krifka et al. Reference Krifka, Pelletier, Carlson, ter Meulen, Chierchia, Link, Carlson and Pelletier1995). Existential readings of subject BPs, such as in Der lever bjørne i Europa ‘There are bears in Europe’, are standardly captured by positing an existential quantifier in a formula like ∃x[live(x) ∧ bears(x)] (here the locative subject marker der ‘there’ is disregarded), which in this case asserts that the property denoted by bjørne holds for some members of the domain, i.e. ‘there is a plurality of bears which live in Europe’.

In object position, BPs receive either a generic or a modificational interpretation, whereas BSs exclusively are capable of providing the latter reading. The modificational reading differs from the generic reading by not being referential – recall that, as we have seen, generic BPs side with normal DPs – and from the existential reading by not asserting the existence of the entity referred to by the NP, i.e. sentences with modificational BPs like e.g. Han kan 0 dressere | katte ‘He has competence in cat training’ would still be meaningful to utter in the case cats became extinct. This means that BPs and BSs coincide in object position of a certain subset of verbs where they both have the function of ascribing a property to the V, which restricts its denotational scope to a subtype, i.e. the expressions 0 dressere | katte ‘train cats’ and 0 vaske | bil ‘wash car’ name a kind of training that applies to cats and a kind of washing that applies to cars. Analysing these BPs and BSs as denoting properties – rather than individuals – which act as event modifiers, i.e. adding a so-called modificational meaning to V, is consistent with those analyses in which the nominals in such cases pseudo-incorporate under V to form a complex unit or predicate (Farkas & de Swart Reference Farkas and de Swart2003; Dayal Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015, among several others). Following Dayal's (Reference Dayal2011:146) suggestion for PI in Hindi, the semantics for a PI structure can be represented as in λP λy λe [P-V(e) ∧ Agent(e) = y], where the internal argument of the corresponding regular transitive structure has been replaced by a place-holder P, which instead of functioning as a Theme should be interpreted as a property denoting predicate modifier restricting the denotation of V (see also Dobrovie-Sorin et al. Reference Dobrovie-Sorin, Bleam, Espinal, Tasmowski and Vogeleer2006). The PI approach to BPs and BSs in object position expressing modificational meaning is additionally substantiated by the fact that they share a number of properties, specifically obligatory narrow scope, fixed V+BS/BP word order, unit accentuation and atelicity, which are usually taken to be, to a certain extent cross-linguistically stable, characteristics of PI, because they are indications of a closer bond between V and NP than we observe in standard complementation structures, where the DP complements occur unrestrictedly with respect to their realisation.

However, the analyses conducted in this paper also show that generally there is a difference between the two types of bare objects, singular vs. plural, both in terms of their susceptibility to syntactic manipulation and the semantic and pragmatic implications of the structures.

The systematic differences between V+BSs and V+BPs with respect to modification, secondary predication and focus transformations indicate that BPs have a more independent role in syntax, and are thus less integrated in V, than BSs. However, the fact that BPs have a comparatively freer role in syntax, in my view, does not challenge the claim that BPs with modificational meaning basically pseudo-incorporate under V in object position, as they clearly show evidence of being more restricted than regular DPs and also comply with a number of the standard requirements for PI, as noted earlier in this paper.

The parameter of number corroborates this picture of a difference in degree of integration between BPs and BSs and their verbs in the sense that BPs have a richer morphological structure than BSs, as they invariably carry with them their plural marking and, therefore, denote pluralities, which always generate non-atomicity entailments (see Farkas & de Swart Reference Farkas and de Swart2003). By contrast, BSs, under certain conditions and dependent on type, can be interpreted as having both atoms and pluralities in their denotational domain, which is a signal of functional non-independence from V, following the logic that the less interpretation-sensitive to a specific number implicature the np is, the more it has gained the status of a modifier.

The type/token distinction in anaphoric reference and its correlation with I-level vs. S-level predicates perhaps cannot be seen as an indication of different degrees of integration between the V and the NP, but it supports the general feasibility of a fundamental distinction between V+BP and V+BS structures. The richer morphological structure of BPs makes V+BP structures compatible with both I-level and S-level predicates, while the higher degree of bareness of (type 1) BSs restricts the use of V+BS structures to expressions of transitory properties.

Finally, arguments were presented in favour of distinguishing between two subtypes of V+BS structures according to the degree of integration between the V and the bare object. In PI structures with type 2 BSs, such as se fjernsyn ‘watch television’, spille violin ‘play (the) violin’, køre lastbil ‘drive lorry’, the BS is resistant to anaphoric activation, is always an object affectum, allows only atelic readings, is completely number neutral and is compatible with both I-level and S-level predicate readings. These factors indicate a maximum degree of integration between the constituents in the sense that the BS is completely insusceptible to outside influence. It is striped of any independent meaning features which potentially could be activated by contextual elements, and its only function is to act as a modifier which forms a complex unit with V and semantically restricts its denotation. By contrast, in PI structures with type 1 BSs, such as bygge hus ‘build (a) house’, vaske bil ‘wash (the) car’, the BS, although significantly reduced in terms of functional features as well, can both be an object effectum and an object affectum – leading to the licensing of both telic and atelic readings – and also bares a clear trace of singular noun number coding, which makes it prone to token anaphora activation and restricts the use of these V+BS structures to expressions of transitory properties.

On these grounds, it can be concluded that only a subset of bare nouns in Danish can be considered to obtain the status as pseudo-incorporated elements, as generic and existential interpretations of BPs must be kept apart from the modificational meaning triggered by BSs and BPs in object position. Although there are relevant contrasts between modificational object BSs and modificational object BPs, which suggests that PI in Danish should be seen as a flexible phenomenon – a continuum of integration between V and BP, BStype 1 and BS type 2 – it is argued that basically V+BS/BP structures distinguish themselves from regular complementation by behaving as tightly knit units whose nominal part functions as a modifier which pseudo-incorporates under V. However, dependent on the type of PI structure, specific contextual clues, such as e.g. the use of S-pronouns, can coerce otherwise discourse opaque modifiers of the complex predicate into playing a more salient referential role in the subsequent discourse. Finally, it is important to recognise that the continuum of integration goes beyond the border of bare nouns investigated in this paper, as also e.g. weak DPs in several languages share some of the defining features of PI (see e.g. Borik & Gehrke Reference Borik and Gehrke2015a:32–35).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the yearly seminar of the Danish Grammar Network in the autumn of 2014 and at the Societas Linguistica Europaea (SLE) conference in Leiden in September 2015. I wish to express my gratitude to the participants in these venues for their helpful comments and invaluable suggestions. A preliminary and simplified version of the analysis has been published in Danish (Müller Reference Müller2015). I would also like to express my gratitude to the NJL reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments. Finally, I want to thank my colleague Inger Mees for her suggestions for improvement and for correcting my English. I am, of course, responsible for all remaining obscurities and mistakes.