The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote:

Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press unanimously praised it to the heavens.Footnote 1

D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’s merits but, in the same article, also urged caution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (I Goti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person who will perpetuate our musical glory?’Footnote 2 This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse.

D’Arcais’s question mirrored an anxiety that went well beyond mere curiosity. During the 1870s and 1880s, operas by foreign composers flooded into Italian opera houses, primarily as a result of the Sonzogno publishing house’s attempt to challenge his competitor Ricordi.Footnote 3 As Julian Budden aptly summarized: ‘The operas most in demand during the 1880s were Carmen, Lakmé, Die Königin von Saba and the early Wagnerian canon. Native works were at discount … whereas a foreign work once introduced would be taken up by one opera house after another’.Footnote 4 The growing popularity of French and German works in Italy not only made it difficult for young Italian composers to emerge; it also reduced the possibility of finding someone who could seize the position Giuseppe Verdi had occupied for the past half century.Footnote 5 Such a situation was further complicated by the decision of the Italian Government, in June 1867, to transfer the administrative duties of opera houses to the local authorities; from that date, the cities became responsible for financing their own theatres. Those cities that did not shut down their opera houses had to raise funds to keep them open, which resulted in citizens having to pay for the staging of an increasing number of foreign works.Footnote 6 This series of circumstances posed a serious political problem in a country that had been unified only for a few decades and where opera was the most important form of entertainment.

Clearly, D’Arcais’s question was not limited to Mascagni’s future achievements but addressed a broader question: when and on account of whom would contemporary Italian opera again hold a sustained dominant position in its native opera houses? Thanks to the critical and financial success of the early performances of Cavalleria, it seemed that a new operatic movement called verismo had been established, and that this trend would eventually be favoured on Italian stages. As Amintore Galli, a well-respected music critic and teacher, wrote after the Milanese premiere of Cavalleria: ‘with [this work] verismo opera begins its kingdom in Italy’.Footnote 7 This view, which became prominent in the early years that followed Cavalleria’s premiere, has been passively perpetuated in several historical accounts of the period until recently.Footnote 8

In the past few years, scholars have made significant efforts to open up new perspectives on and enrich our understanding of verismo.Footnote 9 Not enough emphasis, however, has been placed on both the negative reactions to verismo in Italy during the 1890s and early 1900s – that is, after the initial enthusiasm for Cavalleria and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (21 May 1892) faded away – and the possible alternatives offered to it.Footnote 10 Most music critics had difficulty accepting the idea that new and successful Italian operas could be set in such degraded environments.Footnote 11 Stage settings resembled impoverished districts from contemporary Southern Italy inhabited by disreputable characters belonging to lower social classes, such as prostitutes or camorra henchmen, whose stories often ended with violent murder.Footnote 12 As Giorgio Ruberti has recently noted, ‘the coarsening of the [verismo] subjects … pushed the critics … to take a stance against this repertory and the few who supported it’.Footnote 13 In particular, the Neapolitan debut of Umberto Giordano’s Mala vita in April 1892 was a turning point in the reception of verismo opera, with an increasing number of reviewers criticizing this repertory.Footnote 14 Several critics also found it puzzling that in order to fight the now-dominant position of foreign composers in Italian opera houses, one should exploit stories that conveyed a negative image of the country. The popular success of verismo was particularly disturbing to many of these critics because the audience seemed to respond positively to a repertory that brought bad publicity to Italy.Footnote 15

Many reviewers also pointed out the anti-melodic – that is, not ‘Italian’ – and even vulgar musical effects that characterized verismo works.Footnote 16 These effects included the use of dissonant clashes (cozzi armonici) and extra-musical devices (for example, screams) that exaggerated the dramatic impact of paroxysmal passages.Footnote 17 Finally, reviewers criticized the lack of syntactic regularity in the vocal prosody, and the orchestration as too massive and gloomy.Footnote 18

This criticism of both the quality of the music and the content of the plots made it clear that radical changes were necessary, at least to show audiences how Italian operatic novelties did not have to stoop to the stereotypes of verismo. This change sought to bring back idealism and a patriotic spirit associated with a positive image of Italy, to reassess the importance of the melody as it was conceived before the advent of verismo, and to aim for more refined orchestration as well as a more extensive use of counterpoint. Critics who supported the dissemination of Richard Wagner’s operas in Italy, such as Giuseppe Depanis and the so-called wagneriani, were particularly vocal about this last point; others, who championed the early- and mid-nineteenth-century Italian operatic repertory, placed melody at the centre of their narrative.

Franchetti’s Operas and the Cultural Context of fin-de-siècle Italy

Desire for a change was much in evidence in the reviews that followed the premieres of Franchetti’s two turn-of-the-century works (both librettos by Luigi Illica): Cristoforo Colombo (Genoa, Teatro Carlo Felice, 6 October 1892) and Germania (Milan, Teatro alla Scala, 11 March 1902).Footnote 19 I argue that, thanks to their idealistic content, their intimate connection with Italian history, and the refined style in which they were written, both operas functioned as symbols of national pride and heralded an alternative to verismo.Footnote 20 I also want to argue that Franchetti’s skilled use of counterpoint and orchestration, mixed with a talent for writing effective, well-structured melodies, made him the ideal candidate to settle the debate between the wagneriani and the stalwarts of the Italian tradition (who were sometimes generically labelled as anti-wagneriani), thus allowing him strategically to claim a coveted, yet also politically-sensitive spot in the operatic pantheon.

In spite of the rivalries that existed between Ricordi and Sonzogno, and the no less fierce competition for cultural influence that prevailed among the critics, the consensus was that Colombo and Germania marked a decisive step forward in the development of modern Italian opera.Footnote 21 According to the overwhelming majority of reviews, the two works’ noble aims and patriotic aspirations cemented Italian unity through the celebration of a shared, indeed mythologized history, and revived the sacred ideals of the Romantic period – especially the 1840s and part of the 1850s.Footnote 22 In doing so, Colombo and Germania fit Italy’s turn-of-the-century cultural agenda exceptionally well. The historical cliché bears repeating here: for centuries, Italy had been a cultural rather than a political entity, but following unification the goal was to create a shared, collective memory – and prominent historical figures from the medieval through the early Romantic period provided a convenient means by which to do so.Footnote 23 As musicologist Luca Zoppelli noted, in the early decades that followed the unification of the Italian Kingdom, the ruling classes pursued a national identity by ‘searching for its roots in the civilization of the Italian past … National memories therefore identified with a portrait gallery of illustrious forebears, a Pantheon of intellectual glories … which became a historiographical canon and a stimulus to political action’.Footnote 24 In order to build upon this tradition, Italians publicly celebrated Christopher Columbus and other major figures as icons that perpetuated Italy’s reputation even when it did not exist as a country.Footnote 25

A similar discourse can be applied to the leading figures of the Risorgimento. As most of the Nation’s founding fathers passed away during the 1870s and 1880s, Italians felt the need to keep their patriotic consciousness alive.Footnote 26 In the last two decades of the nineteenth century a multitude of statues, monuments and squares were dedicated to Risorgimento heroes to immortalize their ideals and epic gestures, and celebrate the newly created country.Footnote 27 The proliferation of public tributes to Italian Romantic figures served, especially under Francesco Crispi’s tenure as a prime minister (1887–91 and 1893–96), to keep peace among the social and political forces that competed in post-unification Italy.Footnote 28 Crispi’s strategy consisted of diluting these ‘ideological conflicts’ by creating a ‘national religion based on the syncretistic myth of the Risorgimento’ that would convey a message of unity and fraternity to the Italians.Footnote 29

Both Colombo and Germania provided ample opportunity for the sort of historical and musical commentary that was employed by the critics, many of whom wielded patriotic rhetoric to the disadvantage of verismo opera. The first of these two operas was commissioned to celebrate the four-hundredth anniversary of the explorer’s discovery of the New World.Footnote 30 Italians celebrated Columbus as the supreme symbol of Italian bravery and, in Franchetti’s work at least, he also became the one-man hero who fights against overwhelming enemy forces (such as the powerful noblemen of the Spanish court and the Catholic Church) to achieve his dream of reaching the Indies – but eventually succumbs to the intrigues and scheming of his enemies. Columbus serves as an enlightening force, but also as a foil to obscurantist foreign powers, thus meriting elevated status in Italy’s ‘Pantheon of intellectual glories’, not only for what he represented for the country, but also as a martyr to his own, idiosyncratic ideals. At the same time, this opera helped to bridge the divide between Italian supporters and opponents of Wagner; the former highlighted Franchetti’s extensive studies in Germany, while the latter argued that with him Italy had found a potential Verdian heir.

Even though Germania was set in Germany, as the name suggests, the key theme of this work – the German patriots’ struggle for independence from French invaders during the Napoleonic wars – closely paralleled the Risorgimento experiences in fighting the Austrians. Franchetti’s opera translated into a new context the vibrant passions that characterized the three Italian Wars of Independence, making it possible for the audience to relive the heroic battles and events of a few decades ago. Germania also brought a message of unity that was very similar to the values Crispi was trying to convey. In critical discourse at least, the scene in which lead characters Federico Loewe and Carlo Worms agree to suspend their duel and put down their swords in order to fight side by side against the French army, worked as an active metaphor of political integration and cohesion.

Moreover, both Colombo and Germania generated a longing for works that would host ‘positive’ characters (the fearless Columbus, the selfless German patriots) and nostalgia for the idealized, legendary past populated by such charismatic personalities. This nostalgia was not peculiar to opera but became an integral part of the historiographical narrative that celebrated Italian Romantic heroes. For example, as scholar Eva Cecchinato has observed, the two influential books on the great patriot and revolutionary leader Giuseppe Garibaldi written by naturalized Italian writer Jessie White Mario featured a ‘dominating sense of nostalgia … for [Risorgimento] ideals’.Footnote 31 Restoring those ideals became a priority of Italy’s political and cultural agenda as early as the 1880s, and the widespread sentiments of nostalgia played a crucial role in this process.Footnote 32

Cultural theorist Svetlana Boym has coined the expression ‘restorative nostalgia’ to indicate a kind of nostalgia that ‘characterizes national and nationalist revivals’ and focuses on ‘national symbols and myths’.Footnote 33 This definition suits Franchetti’s Colombo and Germania very effectively not only because they promoted Italian symbols and myths like Columbus, Risorgimento and Garibaldi, but also because these works were interpreted as a ‘healthy’ revival of operatic forms and subjects from the Romantic period in opposition to verismo models.Footnote 34 This reading, which was common among Italian music critics, significantly contributed to Franchetti’s enormous popularity and generated the expectation that he could keep writing successful operas as a response to the Italian turn-of-the century fascination with Romantic nostalgia in both politics and music.

Not only did this expectation go unfulfilled, but such fascination also had an adverse impact on the development of Italian opera, as it was based on the assumption that earlier models could serve as a viable answer to the challenges that awaited this art form in the twentieth century. The eventual disillusionment with Franchetti’s work and its disappearance from the stage by the mid-1910s demonstrates that they could not.

Verismo, Wagnerismo and Cristoforo Colombo

The 1891–92 operatic season witnessed a surprising number of Italian premieres throughout the peninsula, including Mascagni’s L’Amico Fritz, Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, Alfredo Catalani’s La Wally, Umberto Giordano’s Mala Vita, Francesco Cilea’s La Tilda, and Leopoldo Mugnone’s Il Birichino. This string of new works followed the thunderous acclamation of Cavalleria and, as though casting off the shackles of prolonged foreign domination, it seemed for a while that Italian composers had partially regained control of their own opera houses. Franchetti’s Colombo was the first important production of the 1892–93 season, and the fervent anticipation from both the press and audience heightened as the date of the premiere approached. The expectation was that this work would reinforce, and perhaps even consolidate, the positive trend established during the previous season. This sense of anticipation stimulated critical contributions that went beyond the purely musical aspects of the work and actively engaged with patriotic rhetoric.Footnote 35

Moreover, Verdi’s suggestion to assign Franchetti the task of writing this work charged the opera with a highly symbolic meaning. In 1889 the Mayor of Genoa, Stefano Castagnola, asked Verdi to write an opera based on the story of Columbus, which would premiere in the same city during the ‘Italian-American Artistic, Industrial and Commercial Exhibition’ (Esposizione Italo-Americana Artistico-Industriale-Commerciale) of 1892. Verdi, likely occupied with Falstaff and maybe unwilling to link his name to such a blatantly commercial venture, recommended Franchetti. The young composer, who had achieved widespread popularity with his first opera Asrael (premiered in Reggio Emilia in February 1888), accepted this offer and received the commission from the city of Genoa on 20 May 1889.Footnote 36

Franchetti fulfilled and even exceeded both the critics’ and audiences’ expectations: after the successful premiere in Genoa, Colombo received incessant praise not only in the Northern regions, where the influence of his wealthy and aristocratic family was stronger, but also in Central and Southern Italy.Footnote 37 One could have anticipated the extremely positive (maybe even sycophantic) reviews that Milan-based Gustavo Macchi and Giovanni Battista Nappi wrote after Colombo’s Genoa premiere and La Scala’s premiere, respectively.Footnote 38 Perhaps less expected was the unconditional praise that followed the performances of Colombo in Florence (by Giulio Piccini) and Naples (by Rocco Pagliara) in the mid-1890s.Footnote 39 Another welcome surprise was Lorenzo Parodi’s enthusiastic review in Il teatro illustrato, organ of the leading verismo publisher Edoardo Sonzogno. Since Colombo had been published by Sonzogno’s fierce competitor Ricordi, one might have predicted a mild or even cold review from this journal. On the contrary, Parodi expressed his admiration for Franchetti’s talent and predicted a brilliant future for him.Footnote 40 Franchetti was able to spark considerable interest among critics from very different backgrounds and geographical areas, and convince them that his opera was a valid alternative to verismo.

Indeed, during the years immediately following the Genoa premiere, a narrative emerged that portrayed Colombo as a work that fortified both Italian opera and patriotic pride. Part of this narrative was established in the emphatic comments that appeared in Corriere della sera of Milan and Il secolo XIX of Genoa on the day of the world premiere. Achille Tedeschi, critic of the Corriere, stated that there was a ‘desire, in the heart of every Italian, that the glorious and sorrowful epic of such a noble figure as the Genoese explorer should finally live again in a masterpiece of the scenic art’, and the critic of Il secolo XIX expressed his ‘faith that Colombo will assert itself as a new, beautiful and vigorous work, to honour the Italian operatic scene – the only new work which is flourishing, and which may interest a multitude of young [Italians]’.Footnote 41 Alike in their pomposity, both articles asserted the centrality of Columbus as a historical figure and of Franchetti as a composer who was able to attract the attention of a new generation of Italian opera lovers. A few months later, the music critic Aldo Noseda set the bar even higher, claiming that Colombo’s success burdened Franchetti with a ‘solemn responsibility … toward the country’, implying his patriotic duty to perpetuate the country’s good name as Verdi had done for the past half century.Footnote 42 The use of such hyperbole is significant because it clarifies how much critics wanted to link Franchetti’s opera with the patriotic sentiments of Italian people – if not everyone, as argued by Noseda, then at least the most committed operagoers.Footnote 43

The unrestrained approval bestowed on Colombo was explicitly juxtaposed with disparaging comments applied to verismo opera. In particular, several reviewers expressed confidence that Colombo would work as a rival to Cavalleria rusticana, Pagliacci and Mala vita, among others. In the early 1890s Italian critics were aware that an overwhelming variety of operas was offered in their country (to the point that so much competition could be confusing to the average operagoer) but also recognized that verismo had gained a special place in the audience’s hearts.Footnote 44 However, already in 1892, following the premiere of Giordano’s Mala vita, such favour waned considerably.Footnote 45 The Colombo premiere took place only seven months after the first performance of Mala vita (21 February) and five months after its very unsuccessful debut in Naples (26 April).Footnote 46 This failure offered the critics already sceptical toward verismo an opportunity to write negatively about the various works by, for instance, Mascagni, Leoncavallo and Giordano – and to compare them with Franchetti.

Broadly speaking, these reviews can be divided in two main categories. The first category featured articles written by those critics who would push the verismo repertory out of the Italian opera houses altogether, in the hope of making more room for operas like Colombo. A notable example was Francesco Tonolla’s review in La sera: after the La Scala premiere of Colombo he commented that this was an opera ‘significantly different from the bungled, gibberish [verismo works] that has infested the Italian theatres for more than two years [that is, since the premiere of Cavalleria]’.Footnote 47 Other similar examples included reviews by Giovanni Battista Nappi (in La perseveranza) and Agostino Cameroni (in La Lega Lombarda) as late as two and ten years after the premiere, respectively.Footnote 48

The second category of reviewers had a more subtle goal, which was to favour Franchetti’s work over the verismo repertory not only for the affirmative, idealistic undertones, but also because it could help to bridge the gap between wagneriani and anti-wagneriani.Footnote 49 To explain why this musical (and political) reconciliation was desirable for so many critics requires some explanation. Nearly every major study of the reception of Wagner in Italy has demonstrated the fierceness of this dispute, which had raged ever since the early appearances of Wagner’s ideas in journals around the mid-1850s and, even more forcefully, after the Italian premiere of Lohengrin in Bologna in 1871. During the early years of the Italian Kingdom’s existence, and especially in the 1870s and 1880s, the discussions often included accusations of anti-patriotism aimed toward Wagner’s supporters.Footnote 50

The situation was partially ameliorated by Giulio Ricordi’s decision to perform Lohengrin at La Scala again in 1888 after the fiasco of 1873. This decision was motivated by his purchase of Giovannina Lucca’s publishing house during the same year – and with it, the rights to perform Wagner’s works in Italy. An increasing number of critics, including those who had attacked Wagner in the past such as Alessandro Biaggi and Francesco D’Arcais, started to express a moderate appreciation for his operas; nonetheless, prejudices and stereotypes about Wagner and German music did not die easily.Footnote 51

One persistent stereotype was the association of Wagner’s music and writings with Otto von Bismarck’s imperialist ideology, which strengthened further the composer’s image as an icon of German nationalism.Footnote 52 Italian intellectuals and politicians had very ambivalent feelings about the German Empire and Bismarck’s plans – an attitude that bore significant parallels with the way Italian critics viewed Wagner.Footnote 53 Prominent figures such as Prime Minister Francesco Crispi, future Nobel Prize poet Giosuè Carducci, and leading musicologist Luigi Torchi – to mention only a few – publicly praised German achievements in the military sciences, the humanities, the arts, the academic system and so forth.Footnote 54 They fully endorsed the ties with Germany established in 1882 by means of the Triple Alliance (the third member being the Austro-Hungarian Empire), with the assumption that such a close relationship would be beneficial to Italy.

Such an association with Germany, however, did not provoke a particularly positive response from the majority of the Italians; as historian William C. Askew noted, ‘to many [of them] Austria was the eternal enemy, and militaristic, autocratic Germany was almost equally repugnant. Many Italians preferred friendship with France, the cultural model and the home of liberty, equality, and fraternity’.Footnote 55 Obviously, the tensions that followed the French occupation of Tunisia in 1881 had strong repercussions for the relationship between the two countries, as France frustrated the early Italian colonial ambitions and pushed Italy closer to Austria and Germany.Footnote 56 Nonetheless, when more friendly relationships with France were re-established during the 1890s, major political and cultural figures felt free to profess a marked preference for this country and to express strong reservations toward Germany, for fear that it could become an aggressive competitor in Europe.Footnote 57

Another widespread stereotype, not limited to Wagner’s music, was that German composers were better trained in counterpoint than Italians, who instead wrote more successful melodies.Footnote 58 Albeit surprisingly popular, such a cliché was obviously a crass oversimplification that clashed with a much more complex reality. For example, in 1871 Verdi called for young Italian composers to learn and practice fugue, and recent research has shown how nineteenth-century students in Italian conservatories received extensive training in counterpoint.Footnote 59 Possibly, the critics took for granted the Italian composers’ counterpoint practice as a part of their preparatory work and emphasized instead their capacity to write memorable melodies.Footnote 60

Colombo won enthusiastic praise from both the Wagnerian and the anti-Wagnerian fronts, and provided an antidote to the anxieties (and misconceptions) about Wagner. In this opera, Franchetti successfully blended and juxtaposed techniques that could be readily identified with the Italian and German schools – or what critics thought represented the typical musical features of these two countries. Several times the reviews highlighted Franchetti’s graduate work in Germany, where he studied from 1881 until 1885; it was during this period that he perfected his counterpoint and orchestration skills, even going to Bayreuth to attend Wagner’s operas.Footnote 61 Many pointed out Franchetti’s impressive mastery of Wagnerian techniques, including the use of leitmotifs. Nonetheless, the overwhelming majority of the reviews also clarified that he was still a quintessentially Italian composer, able to draw on melodic style and formal procedures that belonged to the nineteenth-century Italian operatic tradition – notably the pezzi concertati.

Franchetti’s technique of assigning a distinct orchestral colour to the most important characters (Roldano, Isabella) and elements of the opera (for example the ocean at night) was repeatedly praised. Columbus’s antagonist, Roldano Ximenes, is introduced by the tuba; Isabella of Aragon by the harp; the instrumental passage that precedes Columbus’s monologue in Act 2 mimics the calmness of the ocean – Franchetti assigns to the strings a simple, consonant accompaniment that only occasionally interjects the melodic line of the winds. Franchetti’s talent for writing effective symphonic excerpts was also frequently acknowledged; the general consensus was that his orchestral passages could hardly be matched by any living Italian composer.Footnote 62

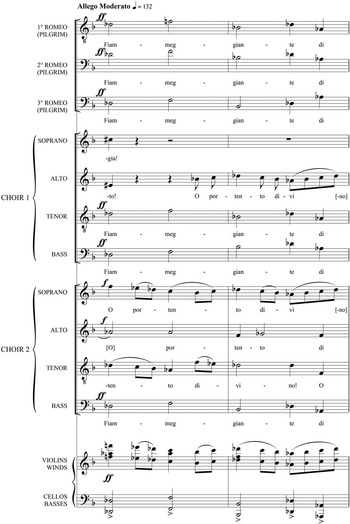

Most critics, however, were primarily impressed with Franchetti’s contrapuntal skills. Following a terminology that was routinely applied to German music, these critics repeatedly defined his technique as ‘supreme’ and ‘erudite’.Footnote 63 A compelling case in point is the 54-bar musical number taken from the Ballata dei romei (or pilgrims’ ballata) in Act 1, Scene 3. The ‘Allegro moderato’ passage, which narrates the legend and travels of Saint Brendan of Clonfert, begins with a three-voice imitative counterpoint and develops into an elaborate concertato.Footnote 64 The growing number of voices that join in mirrors an increasing complexity in texture and harmony. The texture becomes progressively thicker as Franchetti combines winds, two choruses and eventually the strings; meanwhile, harmonically, Franchetti begins with an eight-bar diatonic subject (see the first four bars in Ex. 1.1) and adds occasional chromatic touches to the answer and to the third voice. In spite of the relatively straightforward initial modulations (from F major in the subject to C major in the answer and back to F major when the third voice enters) Franchetti plays with the audience’s expectations after the end of the exposition by presenting again the initial theme in the very distant tonalities of E major and D-flat major (Exx. 1.2a and 1.2b) before ending with a perfect cadence in F major. The number later develops into extensive chromatic episodes (see Ex. 1.3) that show Franchetti’s ability to manage large-scale passages. By means of this number, strategically placed at the beginning of the opera, Franchetti demonstrates an uncommon capacity to manage extensive contrapuntal passages and control harmonic progressions.

Ex. 1.1 Franchetti, Cristoforo Colombo, Act 1, Scene 3. Milan: Ricordi, 1893 (Ballata dei romei, bars 112–115)

Ex. 1.2a Franchetti, Cristoforo Colombo, Act 1, Scene 3 (Ballata dei romei, bars 138–139)

Ex. 1.2b Franchetti, Cristoforo Colombo. Act 1, Scene 3 (Ballata dei romei, bars 148–149)

Ex. 1.3 Franchetti, Cristoforo Colombo, Act 1, Scene 3 (Ballata dei romei, bars 156–158)

Yet, a few reviewers pointed out that Franchetti’s contrapuntal intricacies necessitated compensation, by way of ample passages of ‘melodic relief’. Parodi, a moderate supporter of Wagner, argued for instance that ‘concerning harmonic and orchestral procedures, Franchetti draws a lot from German sources; this is an excellent source, as long as one tempers [its] natural coldness with the warm breath of the South’.Footnote 65 This critic also drew on stereotypes that juxtaposed the ostensibly ‘cold’ procedures Franchetti had learned in Germany (often described in the press as ‘scientific’) with the melodic ‘warm breath’ usually linked to Italy (‘the South’). Parodi likely wanted to emphasize that Franchetti had taken full advantage of his studies in Germany without compromising his integrity as an Italian composer. He was certainly not alone in this respect, since many of his colleagues associated terms such as ‘Italian’ or ‘pure Italian’ with Franchetti’s melodies.Footnote 66 Clearly, Franchetti’s writing style matched the critics’ expectations and was even called forth by it; yet, one wonders what exactly the ‘Italian’ qualities of his melody were.

Composers’ resistance against the innovative verses that the Italian librettists produced during the late nineteenth century can offer one possible answer. As Nicholas Baragwanath argued in his study on the nineteenth-century musical traditions in Italy:

[T]he musical reforms that took place over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, although undeniably effective in introducing progressive foreign influences in Italy, left many of the foundations of the original traditions intact. Composers were not always inclined, for instance, to match the freedom and irregularity of the new style of versification ushered in by Boito’s reforms with similarly asymmetrical phrase structures.Footnote 67

Franchetti’s regularity in melodic phrasing and structure, and resistance to Illica’s uneven (and little appreciated) versi sciolti, offers one possible interpretation of the critics’ standpoint about the ‘Italian’ qualities of melodic contour in Colombo.Footnote 68 One instance is in Act 1, Scene 9, after Columbus has learned that the Council assembled in Salamanca has rejected his project to reach the Indies (see Ex. 2). Here, the explorer launches himself in a disheartened aria in ‘Larghetto mesto’:

Ex. 2 Franchetti, Cristoforo Colombo, Act 1, Scene 9

Illica organized each line in endecasillabi (11-syllable) verses, but in order to be syntactically complete the second line needs the verb (fugge) located at the beginning of the third. Since the first line was set to a customary four-bar musical phrase, Franchetti faced the problem of keeping the second phrase symmetrical with the first, in spite of the three extra syllables (mi fug-ge) needed for the line to retain its syntactic meaning. He solved the matter by using shorter notes in the second part of the musical phrase (starting at ‘del pensiero mi fugge’). By doing so, and despite Illica’s uneven versi sciolti, the composer managed to preserve the four-bar symmetry customary in Italian arias. This procedure was clearly indebted to Verdi’s late operatic works, particularly Aida; even in those verses that lacked regularity, the older maestro was still able to write melodies that were largely symmetrical.Footnote 69

Franchetti reinforces this symmetry in several other ways. He places a crotchet rest at the end of the first phrase (after m’afferra) and an even longer one after mi fugge, probably to mark the unusual organization of the poetic text. Then he has the violins imitating, over the crotchet rest in the voice line, the same melodic figure that Columbus sings in the second bar. Franchetti also keeps the design of the bass line consistent in each of the two halves; he holds the bass steady in the first four bars on the tonic and then has it move at a regular pace of a crotchet in the second four bars (cellos play during the first part of this phrase, and the bass clarinet brings it to a close). Between bars 9 and 12 (which corresponds to the end of the third line) the bass contour resembles once again bars 1 to 4. One final means of marking the symmetry is by way of tonic-dominant construction: from bars 1 to 8 Franchetti leads the phrase from the tonic of B-flat minor to its dominant, F major.

Franchetti treats the relationship between melody and harmony more ambiguously, since the succession of notes that make up the former run counter to the harmonic and tonal structure. The melody, for example, never emphasizes the tonic (B♭) and only occasionally marks the dominant (F). Moreover, even though the passage is in B-flat minor, the raised leading tone of A is never sung. One would almost be tempted to conclude that Franchetti wanted to distance himself from the earlier Italian opera and keep a more original, personal approach to it. The composer, however, consistently made use of a series of intervals that, according to Abramo Basevi’s renowned Studio sulle opere di G. Verdi, constituted the ideal recipe to create the ‘catchiest melodies’ in opera.Footnote 70 Even though this study was first published some 30 years before Franchetti started working on Colombo, it was still influential in the 1880s. In particular, Basevi mentioned the use of the ascending fourth, the major sixth, the third and the descending fifth. Interestingly, Franchetti utilized all of them in the first four bars of the aria. Even though comments about the alleged ‘Italian’ qualities of Franchetti’s melodies may not simply originate from the use of intervals commonly associated with former nineteenth-century Italian opera, it is likely that a series of recognizable interval patterns partially contributed to the critics’ use of that adjective.

When Illica offered Franchetti more conventional verses, the composer obliged with consistent phrase patterns for both melodic contour and rhythmic designs. Although neither poetry nor music show the consistency that the ‘lyric prototype’ provided in earlier Italian opera, one can still recognize the A–Aʹ–B–C music structure associated with it.Footnote 71 For example, Columbus’s aria in versi lirici ‘Aman lassù le stelle’ in Act 2, Scene 2, follows a consistent seven-syllable pattern (settenario) with the first two lines organized in hemistich that create an Alexandrine verse.Footnote 72 In this ‘Allegretto scherzoso’ passage Columbus anthropomorphizes the stars and describes them as being in love with each other albeit separated by great distances (only the first two of the four stanzas, A and Aʹ, are shown).

The melodic and rhythmic contours of the two hemistichs (which correspond to bars 1–4 and 9–12) bear significant similarities (see Ex. 3). In the first bar of the first phrase Franchetti introduces a melody based on the three notes of F major (C–F–A), which is the starting tonality of this stanza. This melodic figuration is inverted in bar 9, although the composer omits the fifth (F–A–F) and places the phrase in a more ambiguous harmonic territory, thanks to the descending orchestral chromatic line in bars 9 and 10. Another parallelism is in bars 2 and 10, where Franchetti writes a melody that has a similar rhythmic pattern, even though the second note in bar 2 is broken down in one crotchet and one quaver note, while the second note in bar 10 is a dotted crotchet. Finally, a parallelism occurs in bars 4 and 12, where both melodies present a strikingly similar profile.

Ex. 3 Franchetti, Cristoforo Colombo, Act 2, Scene 2

Franchetti, however, also distinguishes A and Aʹ by differentiating the second halves: the hemistich of stanza A (bars 1–4) contrasts with the two settenari (bars 5–8, the only exception being the vague resemblance between bars 4 and 8) while the melody and rhythmic contours of the hemistich of stanza Aʹ (bars 9–13) is almost identical to the two settenari (bars 13–16). Although less noticeable, Franchetti also highlights this contrast between A and Aʹ by emphasizing the brasses in the first stanza (bars 3–4 and 7–8) and the strings in the second stanza (bars 11–12 and 15–16). The remaining two stanzas (B and C) present contrasting elements with A and Aʹ: the harmony of B is increasingly ambiguous, and the melody bears no resemblance to the previous sections. In stanza C (and in the brief coda) the melodic contour is still considerably different from the previous ones, but Franchetti brings this passage to its logical end by returning to F major.

It is no surprise that in his review of the world premiere of Colombo, Giuseppe Padovani of the Bologna newspaper Il resto del Carlino, praised Franchetti for providing a ‘meeting point between the most fervid apostles of the great divinity of Leipzig, and the pertinacious supporters of the sugary melodies of our beloved grandparents’.Footnote 73 Its position as a ‘meeting point’ between two musical cultures was one of the reasons for Colombo’s remarkably positive reception; several reviewers (Padovani included) felt confident that Franchetti was on the path toward a brilliant career.

Franchetti’s success, however, brought about at least three major repercussions in his professional life. The most obvious is that, despite being associated with the members of the so-called giovane scuola who wrote verismo opera, he was now identified as the anti-verismo composer.Footnote 74 (This is ironic, considering that today Franchetti is firmly associated with the giovane scuola.) Franchetti also quickly gained international visibility, reinforced by the numerous performances of Colombo in Italy and abroad.Footnote 75 This success charged the composer with responsibilities that were too big to handle. Noseda’s comment, quoted earlier, according to which Franchetti was now facing a ‘grave responsibility … toward the country’, is just one of many similar examples.Footnote 76 So much pressure, which would have been difficult to handle even for an experienced composer, became unsustainable and probably emotionally unbearable.

The stress on Franchetti to meet expectations only brought about the unsuccessful Fior d’Alpe (Milan, Teatro alla Scala, 1894) and Il Signor di Pourceaugnac (Milan, Teatro alla Scala, 1897).Footnote 77 The former received biting reviews from the Milanese critics, but enjoyed some success in Naples where it lasted a few performances.Footnote 78 The comic opera Il Signor di Pourceaugnac endured a similar lacklustre reception in Milan, though it did receive a few follow-up performances in Genoa and Rome.Footnote 79 Verdi’s sharp comment on this work (‘Franchetti has fallen for that Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, which even God would find impossible to turn into a decent opera’) served as the kiss of death, offering the opera no obvious way back to the stage.Footnote 80

The Risorgimento Transposed in Time and Place: Germania as a Metaphor

It was only after the two negative experiences of Fior d’Alpe and Il Signor di Pourceaugnac that Franchetti accepted his father’s advice to turn again to Illica. In June 1897, during a meeting held in Milan, the librettist proposed to both Franchetti and Ricordi a libretto titled Germania. In this work, a love triangle becomes an excuse to celebrate the German patriots’ resistance against the invasion of the Napoleonic army in the early nineteenth century. Even though this plot was set in a different geographical and historical context, the allusions to Italian events of the Risorgimento period were obvious: the French army stood in place of the Austrians, the young Germans who belonged to the Tugendbund (the secret organizations that fought for a free Germany) paralleled the members of Giuseppe Mazzini’s Giovine Italia, and the idealist (and fearless) hero Federico Loewe embodied the figure of Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Even though political scandals, military defeats and social difficulties had affected Italy in its early decades, the cult of the Risorgimento heroes remained strong.Footnote 81 I argue that this cult of heroes, reinforced by the strategy of creating throughout Italy an urban space populated by patriotic monuments, influenced Franchetti and Illica during the process of writing Germania.Footnote 82 Furthermore, critics commented very positively about this opera not only because they perceived it as a healthy return to the style that had made Franchetti famous, but also because they quickly realized what topic really stood at its core – and enthusiastically embraced it.

In a letter that he sent to his father when the work was still in its early stages, Franchetti described Illica’s libretto as ‘grand, powerful and elevated’.Footnote 83 Franchetti conveyed these feelings in arias (most famous is the one sung by the patriot Federico, ‘Studenti, udite!’) and, even more effectively, in powerful, collective scenes populated by German patriots.Footnote 84 The scene in the Prologo that immediately follows ‘Studenti, udite!’ shows Federico Loewe introducing his closest friend, Carlo Worms, to several prominent historical German figures that fought against the French. These included August Wilhelm von Schlegel and his brother Karl Wilhelm Friedrich, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, the composer Carl Maria von Weber, the philosopher and diplomat Friedrich Wilhelm von Humboldt, lieutenant general Ludwig Adolf von Lützow and the poet and soldier Karl Theodor Körner among others.Footnote 85

However, a pioneer of musicology in Italy, Luigi Torchi, pointed out in his famous essay lambasting Germania that not all of these figures were actually involved in anti-French activities. Furthermore, he argued that both Illica and Franchetti offered a picture too idealized of the early nineteenth-century German patriots. Torchi studied in Germany between 1877 and 1884 and knew its history very well, to the point that he could criticize several aspects of Germania in great detail.Footnote 86 For example, he mentioned that in 1806 (the year in which the Prologo takes place) not all of these patriots were young and enthusiastic; Fichte, to name just one, was by then 44.Footnote 87

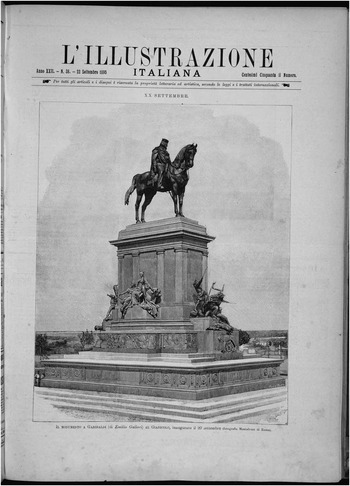

Torchi’s observation, although correct, missed the point; Illica and Franchetti wanted to create an ideal tableau vivant of historical figures who contributed to the formation of German identity in times of foreign occupation rather than a philologically accurate scene. This tableau vivant worked as a parallel to the many monuments built in various Italian cities toward the end of the nineteenth century to honour the protagonists of the Risorgimento. One outstanding example would be the busts and statues located on the Janiculum Hill in Rome; in addition to the equestrian monument dedicated to Garibaldi (see Fig. 1), inaugurated in 1895 and located on the highest point of it, by 1902 (the year of Germania’s premiere) the Janiculum already hosted 21 marble busts of patriots.Footnote 88 These included garibaldino leader Nino Bixio, General Alessandro La Marmora, politician Nicola Fabrizi and various personalities who stood on the side of the Repubblica romana during the 1849 siege of Rome – among them Angelo Masina, Pietro Roselli, Luciano Manara and Ludovico Calandrelli.

Fig. 1 Drawing of the equestrian monument to Giuseppe Garibaldi from the cover page of L’Illustrazione italiana 22/38 (22 September 1895). The monument, created by Emilio Gallori, was inaugurated on 20 September 1895. Image used by permission of the Marucelliana Library in Florence, Italy. Coll. RIV.A.27. This image cannot be reproduced without written consent of the Marucelliana Library Director.

In Germania, the scene that immediately follows the arrival on stage of the historical German characters quickly reaches a climax when the young patriots all sing the hymn Lützows Wilde Jagd (text by Theodor Körner and music by Carl Maria von Weber) to reassert their loyalty to the cause of a free Germany. Franchetti included this hymn, still identified as a patriotic song in Germany, as an example of local colour.Footnote 89 Indeed, Lützows Wilde Jagd (retitled by Illica and Franchetti as La Wilde Jagd di Weber) recurs at five key moments in the opera to remind the audience of the pervasiveness of the patriotic sentiments that inspire the characters’ actions. The initial rendition, however, is most important because it works as a cathartic, collective experience shared by the main characters of the opera (Federico Loewe, Carlo Worms, Giovanni Palm, Crisogono, Ricke, Jane) and the historical figures mentioned earlier.

Franchetti does not alter Weber’s original melodic and rhythmic profile but adds elements that would readily convey the fighting spirit of the Tugendbund members; for example, he marks the piece ‘Allegro con fuoco’ and alternates piano dynamics at the beginning of each phrase with sudden forte bursts at the end. He also organizes it following a clear A–B–Aʹ form, with the first 11 bars in D major and homophonic, and the central four bars in the dominant A major and monophonic (the first five bars of the A section are in Ex. 4). Finally, the composer alters the piece in two more ways: he adds a brass accompaniment at the beginning to convey more solemnity and includes both male and female voices. These are two noticeable changes because Weber’s original version is a cappella and for male voices only.

Ex. 4 Franchetti, Germania, Prologo. Milan: Ricordi, 1902 (La Wilde Jagd di Weber, beginning)

With this piece Franchetti likely wanted to highlight the importance choral singing had in defining German identity and patriotism, establishing a parallel with Italian history.Footnote 90 Choruses in Italian operas had played a significant role in building patriotic feelings since the 1820s. They emerged as ‘collective individuality’ that helped forge a strong sentiment of unity during the period of the Risorgimento battles, and would subsequently be used to cement the attained independence.Footnote 91 Franchetti grew up in unified Italy (he was born in 1860), but he certainly had the opportunity to listen to these choruses and learn what they meant for the earlier generations; it is reasonable to suggest that with the Lützows Wilde Jagd he intended to convey a patriotic message to the Italian audience.

Music critic Ugo Pesci seems to confirm this hypothesis in the review on the world premiere of Germania that appeared in the Ricordi-owned Gazzetta musicale di Milano. Pesci claimed that the ‘patriotic feelings’ that emanated from some of the most important passages of the opera (which included the Lützows Wilde Jagd) ‘[shook] the audience and [made] it spring up from the benches’ of La Scala.Footnote 92 Of course, it may be possible that this critic purposefully exaggerated the effects that Franchetti’s music had on the audience in order to please Germania’s publisher, Ricordi. However, reviews of the same event and of later Germania performances in various Italian cities (Bologna, Naples, Florence) seem to confirm Pesci’s claim.Footnote 93 The librettist and musicologist Luigi Villanis predicted a great future for this opera not only for its musical qualities, but also because it evoked collective memories of the Risorgimento struggle. Even though Villanis had not lived during the Risorgimento (he was approximately Franchetti’s age) he compared the oppressed Germans with the Italians from a few decades past and clarified that such a plot could only recall the revolts inspired by Garibaldi and his army.Footnote 94

In addition to the extensive remarks on the Risorgimento and patriotism, two more tendencies emerged from the reviews: one included persistent anti-verismo statements, while the other constantly referenced the ‘Italian’ qualities of Franchetti’s music. Both tendencies present remarkable parallels with the comments that appeared ten years earlier, and should be investigated in a more nuanced, sophisticated framework that addresses the changes that took place during that period in Italian operatic history.

In the 1890s a multitude of composers wrote operas inspired by verismo-related subjects hoping to emulate Mascagni and Leoncavallo; although a few of these works enjoyed some popular success, the majority left the critics disillusioned with verismo.Footnote 95 This is likely one of the reasons several reviews of Germania’s premiere asserted that the time was ripe for idealism to come back as a central element in Italian musical life. Franchetti’s music was repeatedly labelled as ‘aristocratic’ and ‘elevated’, as opposed to the ‘vulgar’ and ‘deleterious’ verismo.Footnote 96

The most adamant in juxtaposing Franchetti’s achievements with verismo opera was probably the conservative Agostino Cameroni. Frustrated with the verismo composers and librettists, and with the audiences who still showed interest in these operas (he severely chastised the ‘most morbid taste of the crowds’), in 1902 Cameroni enthusiastically thanked Franchetti for fulfilling the ‘legitimate needs [of] a healthy and educated theatrical audience’.Footnote 97 This was a major change from anti-verismo criticism that primarily focused on (and blamed) the composers. Cameroni realized that Cavalleria, Pagliacci and many other verismo works could not have survived for so long without the public’s support, and expressed his gratitude to Franchetti for producing an opera that appealed to an audience with more sophisticated tastes.

Other leading critics echoed Cameroni’s view and juxtaposed Franchetti with verismo works that were still being performed in the early 1900s.Footnote 98 However, comments that appeared within months of Germania’s world premiere also suggest that this work was now juxtaposed with other operatic movements as well – including, for example, exoticism.Footnote 99 One outstanding example is that of Giulio Piccini in the newspaper La nazione at the time Germania premiered in Florence in late 1902. After praising Franchetti, Piccini blamed Mascagni for utilizing music (a ‘divine art’) to depict the ‘most sad episodes of taverns and brothels – and even Japanese brothels!’ in his ‘exotic’ opera Iris.Footnote 100

This and other comments that compared the positive qualities of Franchetti’s music to the various Italian fin-de-siècle musical ‘isms’ (verismo, esotismo, simbolismo and so forth) possibly indicate that this composer still provided a solid standard against which a number of his colleagues were measured.Footnote 101 Ten years after the success he had achieved with Colombo, Franchetti stood again at the centre of the discussions on Italian opera with the major difference that his newest work was now compared to verismo as well as other movements then present on the operatic stage. A key element of Franchetti’s musical benchmark was, once again, the ‘pure Italian source’ of his inspiration – especially in reference to his melody.Footnote 102 In the words of Amintore Galli, writing in the Sonzogno newspaper Il secolo, ‘The characters of Germania sing melodies whose contours are broad, [made with] regular periods, which unfold with a well-defined and relentless musical eloquence – nothing is vague or nebulous’.Footnote 103 Adjectives like ‘clear’, ‘square’ and ‘balanced’ abounded in the reviews, essentially confirming that Illica’s irregular verses did not affect Franchetti’s melodic style.Footnote 104

The repeated references to the ‘Italian’ qualities of Franchetti’s work seem to confirm the growing obsession for the cult of Italian-ness (italianità) in music at the turn of the century. Scholars have shown that music, and opera in particular, compensated for the shortcomings of contemporary politics in fin-de-siècle Italy.Footnote 105 Italian music went from being just one of the many artistic traditions of the unified country to representing an ‘archetype’ that stood at the basis of the ‘ethnic-geographical [Italian] stem’, with the primacy of melody becoming the quintessential symbol of this archetype and identity.Footnote 106 This cult of italianità may be one of the reasons for the two main differences one notes between the reviews of Germania and Colombo: one is that, as opposed to what happened in 1892, Wagner’s influence was barely mentioned. This may seem ironic considering that Germania addresses a topic closer to Wagner’s ideology, and that Franchetti made use of leitmotifs even more than he did in Colombo.Footnote 107 Another irony is that Wagner’s influence on Italian composers and the presence of his operas in Italian opera houses became increasingly noticeable throughout the 1890s, to the point that they were eventually accepted as a matter of fact.Footnote 108

It is likely that once this influence was established, most critics decided to focus on musical parameters – such as melody – where they could still assert their national identity. For many of them, Franchetti’s musical style epitomized the ideals of an ‘Italian’ model based on the keywords mentioned earlier (‘clear’, ‘balanced’ and so forth) that best represented this identity. Moreover, the absence of Wagner in the reviews makes sense if one considers that by the early 1900s the debate between wagneriani and anti-wagneriani had lost momentum. Discussions about Wagner’s music and its significance for the Italian operatic repertory continued well into the early decades of the twentieth century but never again reached the intensity of the years between the early 1870s and early 1890s.Footnote 109

Another difference was the criticism of Franchetti’s excessive use of counterpoint, which in some instances obscured the clarity of the melodic lines – a kind of criticism that rarely occurred at the time of Colombo. The nationalist critic Romeo Carugati, for example, praised Germania’s melodies for being ‘simple, fluid, in the Italian style’ but also attacked Franchetti’s ‘erudite’ contrapuntal technique since ‘the melody’s simplicity did not appear during a first hearing [as] it was entangled with the skilled harmonic setting’.Footnote 110 If one may expect Carugati, who was notably against foreign influences, to express such opinion, it was probably more surprising to read Nicola D’Atri (still a conservative critic but certainly more moderate than Carugati) to censure Franchetti on the same exact ground.Footnote 111 No one denied Franchetti’s talent for writing highly effective contrapuntal passages, but if the key value of italianità coincided with that of a clear, recognizable melody, such melody should not be blurred by an excessively dense texture.

Finally, one surprising element about the reviews of both Colombo and Germania is the scarcity of references to Giacomo Puccini. This may not be so unexpected at the time of Colombo’s premiere, as in 1892 Puccini had not yet achieved any major international success. This absence, however, is remarkable in the reviews of Germania, because by 1902 Manon Lescaut, La bohème and Tosca had all received international recognition. One possible reason is that Puccini and Franchetti, despite their long-standing relationships with Illica, were stylistically too different and devoted themselves to plots that had no similarities; as David Kimbell remarked, ‘Puccini … expressed no spiritual aspirations in his operas and had no moral ambitions for them’.Footnote 112 Moreover, Franchetti’s works were considered anti-verismo; indeed, Mascagni and other composers who wrote at least one opera labelled as verista were occasionally mentioned and juxtaposed with Franchetti. Although some of Puccini’s operas share common elements with verismo, he was never as closely associated with this movement as other composers of the giovane scuola. In both cases, reviewers likely realized that it would make little sense to compare the two composers.

No matter how reasonable these hypotheses might be, it is still worth considering a third one that centres on the uneven reception of both La bohème and Tosca – and how this reception connects with the critics’ response to Germania. Several music critics perceived La bohème as an opera that lacked ‘organic wholeness’ and Tosca as an ‘insincere’ work that was ‘fraudulent at all levels’.Footnote 113 Opposite terms, such as ‘organic’ and ‘sincere’, recurred on a regular basis in the reviews of Franchetti’s operas – and especially of Germania.Footnote 114 It is certainly not surprising that critics used these terms in connection with Puccini and Franchetti; discussions about organicism and the composers’ artistic integrity (or sincerity) were prominent in the musical debate of fin-de-siècle Europe, and Italy was no exception. Italian music critics, increasingly preoccupied with the concept of organicism, found in Germania the qualities of unity and homogeneity that they could not detect in La bohème. At the same time, they found Franchetti’s ‘honest’ and ‘frank’ musical inspiration was carefully attuned to powerful ideals of patriotism that stood at the core of Germania’s plot – the exact contrary of Tosca’s ‘fraudulent’ insincerity.

It is likely that, in spite of Ricordi’s long-term plans to make Puccini the new ‘national composer’ and the ideal candidate for the role of Verdi’s ‘heir’, a substantial portion of Italian critics opposed this officially selected heir. By 1902 Franchetti had published four operas with Ricordi (Asrael, Cristoforo Colombo, Il Signor di Pourceaugnac and Germania), but the publisher never seemed to have thought of launching him as the new leading figure in the operatic realm. While Franchetti did not have the advantage of Ricordi’s elaborate myth-making apparatus enjoyed by Puccini, he still received the resounding endorsement of several critics. As a result, at least around the time of Germania’s premiere, the reviews deliberately ignored Puccini and instead discussed Franchetti as a plausible successor of the recently deceased Verdi.Footnote 115 Yet, both Puccini’s lasting success and the disappearance of Franchetti’s operas work as a reminder of the relatively limited impact that the music critics had on both audiences and impresarios. Music publishers had a much stronger influence, and Ricordi, consciously or not, wielded it in a way that was more beneficial to Puccini than to Franchetti.

Conclusion

Commenting on a revival of Colombo in October 1902 in the newspaper La perseveranza, Nappi expressed disappointment with the development of Italian opera in the last decade: ‘Ten years have passed … since the [world] premiere of Franchetti’s Colombo. Ten years … have not clarified what Italian opera in Italy is or wants to be’.Footnote 116 More than a disappointment with the supposed lack of direction Italian composers had shown, Nappi’s comment seemed to imply discontentment with the fact that only Franchetti had followed the direction that he and many of his music critic colleagues had suggested. Indeed, during the ten years (1892–1902) that passed between the premiere of Colombo and that of Germania, new verismo opera continued to be staged. Plots that focused on major figures of Italian history never became popular (with the exception of Leoncavallo’s I Medici), and very rarely did composers devote themselves to librettos based on patriotic ideals.Footnote 117

It is hardly surprising that a substantial number of Italian critics repeatedly expressed exceptionally positive opinions about Franchetti in the years that immediately followed Germania’s world premiere – to the point that some even claimed he could be Verdi’s true successor.Footnote 118 Yet, such an unrealistic claim only makes sense if one considers that this opera arrived at the ideal moment to relieve the anxieties generated by Verdi’s death in January 1901. Since no new composer emerged to follow the values and directions suggested around the time of Colombo’s premiere, Germania probably convinced at least a few critics that it was worth granting Franchetti another chance.Footnote 119

Not only did Franchetti ultimately fail to meet their expectations, but Germania and Colombo finally succumbed to that characteristic, late-nineteenth-century jinx of excessive initial acclamation; both operas fell out of favour, disappearing almost completely by the first half of the 1910s. Several reasons stand behind this double failure and, of course, only some of them depended upon Franchetti himself. By 1902, Franchetti was no longer a promising young composer and, in the years that followed, he repeated the mistakes of a decade earlier, choosing subjects and librettists that did not fit his musical style.Footnote 120

With regards to the disappearance of the two operas, one should also mention the difficulties of staging Colombo (already apparent at the time of its early performances) and the much-changed political climate that attended the subsequent reception history of Germania. By the outbreak of World War One Italians were, understandably, no longer enthusiastic at the prospect of attending an opera that supported the cause of a free Germany. Moreover, operas based on patriotic ideals or stories that addressed the Risorgimento never became popular in Italy; Franchetti was not able to establish the basis for an operatic movement the same way Mascagni (whether he planned it or not) had done with verismo.

A few adverse comments also served as a possible warning that Franchetti’s operas may not stand the test of time: immediately after Colombo’s premiere, for example, Depanis pointed out that while the first two acts and the epilogue contained many excellent ideas, both the music and plot of the third and fourth acts were not as effective.Footnote 121 Franchetti felt very conscious about this imbalance and adopted a variety of solutions in an attempt to right it; these ranged from fusing the two acts to cutting them altogether, but he never found a solution on how to reorganize them – or how to offer a clear, definite physiognomy to this opera.Footnote 122 Still in October 1902, for example, Giovanni Pozza of the Corriere della sera remarked that Colombo had received few performances in Milan after its premiere because of the ‘difficult’ music that characterized these two acts.Footnote 123

Similar comments occurred with Germania: following a performance at the Costanzi theatre in Rome in 1903, the music critic of La tribuna argued that in spite of the deserved success, one of the main problems of Germania was that Illica had crammed too much action in this opera, and Franchetti had been forced to devote a very limited amount of space to the ‘passional element’.Footnote 124 Whether this may or may not be true (the love duet between Federico and Ricke in Act 2 was one of the most successful passages of the work), the critic seemed to imply that the lack of romantic duets might be detrimental to the long-term success of Germania.

Finally, and probably most importantly, both operas were highly praised because they reassured the Italians about their glorious past but, ironically, this turned out to be a disadvantage in the long run. Colombo and Germania fell victim to Romantic nostalgia which, combined with a variety of factors – including the financial problems that forced the opera houses to become more conservative in their repertory choices, or the publishers’ tendency to invest less on younger composers – made it impossible for Italian opera to renew itself and, within a few decades, led to its dissolution.Footnote 125