Introduction

During Juan Manuel de Rosas's two near-consecutive governments (1829–32 and 1835–52), Argentina (at that time called the Argentine Confederation) was politically divided in two antagonizing factions: the federalists and the unitarians (in Spanish federales and unitarios). Rosas, a federalist, is best known to history for persecuting and killing unitarians, effectively censoring any political opposition.Footnote 1 A para-police force called Sociedad Popular Restauradora (Popular Restoration Society), more commonly known as Mazorca, enforced Rosas's policies on the streets.Footnote 2 Fear of retribution from the regime permeated all aspects of life in Buenos Aires, even down to everyday fashion: for instance in the obligatory use of the divisa punzó (red ribbon), or through the men's facial hair.Footnote 3 As a result many unitarians were forced into exile in bordering countries. Although censorship was an ever-present tool of the regime, many newspapers from Buenos Aires also served as platforms for an ongoing attack on the unitarians who were critiquing the regime from abroad. During the 1840s, however, the region achieved a certain economic and political stability, leading to a decrease in the violent persecution of his opponents. Yet there was one event that shook society and in which Rosas once again turned to violence in order to assert his power. In 1847 Camila O'Gorman (the 19-year-old daughter of a well-to-do, federalist family) eloped with the Spanish priest Uladislao Gutiérrez. Their elopement challenged the moral norms of Buenos Aires society regardless of political persuasion, empowering Rosas to set an example for the public by punishing the couple for their transgression. They were executed.

By this time, Italian opera had made its reappearance in the theatres of Buenos Aires. During the early years of the nineteenth century, the ruling elites in the city (as well as in other parts of Latin America) used opera and theatre as a vehicle to establish norms of taste, civility and morality.Footnote 4 Opera, in particular, had been central to cultural life in Buenos Aires before Rosas but after he consolidated his political power no operas were publicly staged for more than a decade. Only in 1848 did opera reappear, eagerly awaited by local audiences.Footnote 5 The seasons between that year and 1852 were of particular importance – Bellini's and Donizetti's operas were the most performed – but we have little access today to information that can help us fully understand them: some of our only surviving sources are librettos (sold a week before the performances), reviews in the local newspapers, and some accounts in the newspapers of neighbouring capital cities, such as Montevideo and Santiago de Chile.

It was not uncommon for federalists and unitarians to use reviews and letters to the editor published in the newspapers of Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Santiago de Chile as battlefields on which to advance their political views. According to theatre historian Martín Rodríguez, the function of art at this time was to educate the audience and to contribute to the development of society; thus, theatre was an activity subordinate to politics – as the press was also perceived to be.Footnote 6 Similar fields of debate opened up between politics and opera; these were not reflected directly in reviews of the works but rather in discussions among readers and opera critics.

Newspaper accounts have been explored previously by scholars and local opera historians, but librettos have not formed a focus for discussion, as they are often considered to be a token of the experience and a direct translation of the Italian or French originals. However, from a close reading we can see that the librettos were not static or fixed, but were instead modified and utilized to fit local ideals. In this article, I examine one opera in particular, Vincenzo Bellini's Norma, arguing that, following the Camila O'Gorman and Uladislao Gutiérrez scandal, its representation in Buenos Aires seems to bear political overtones that display some parallels with the affair. I seek, therefore, to resituate scholarly understanding of the opera in terms of local politics.Footnote 7 By creating a parallel between Camila and Norma's stories, I will argue that the libretto used for the Buenos Aires performances could have served a moralistic purpose, as well as removing the guilt – that is the general condemnation of the ‘people’ driven mostly by the unitarians – associated with Rosas's decision to execute the couple. This includes stripping the character of Adalgisa (the young priestess in love with Pollione, Norma's lover) of her religious embodiment and reinforcing the character's treason to her fatherland rather than her religion, and thereby justifying Norma's death as the only form of redemption.

Mary Ann Smart has proposed a relationship between politics and music in which the latter gives meaning to the former. She states that ‘[f]or music to be considered as “political”, it should be possible to demonstrate that it has affected some aspect of concrete reality: the experience of hearing the music must have changed events in some fundamental way for listeners’.Footnote 8 Yet, I would like to invert this relationship – as I aim to show in the Argentine case – by investigating not how music can produce social change but rather the opposite: how political events can affect and condition listeners’ hearing and understanding of music. This coincides with Catherine Clément's understanding of the relationship between opera and politics. Contrary to Smart, Clément discusses the malleability of musical meaning or ‘moral ambiguities’ of opera and how its interpretation changes according to particular contexts. As an example, Clément shows how the staging of Beethoven's Fidelio in Vienna during the Nazi regime, and again seven years after the end of World War II, managed to portray the values of both antithetical situations.Footnote 9

Following Clément's ideas, in broader terms this paper will not only shed light on the political implications of operatic performances during the Rosista regime, thus contributing to the history of music in Argentina, but it will also explore the genre's inherent malleability as it moved from place to place, fitting particular contexts and fulfilling political expectations in ways that remain invisible without the sort of detailed local investigation that I present here.

A Historical Glance

Two major political groups emerged after the May Revolution of 1810 and the Declaration of Independence of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in 1816, carrying opposing views of how the country, known today as Argentina, should be ruled. The unitarians championed liberal economic ideas and advocated for the centralization of power in Buenos Aires, while the landowners dominating the federal party favoured the egalitarian union of the provinces and fought to maintain the feudal economy inherited from Spanish colonial times.Footnote 10 This rivalry culminated in a civil war at the end of the 1820s, allowing Rosas to come to power in 1829. Under Rosas, Argentina had not yet become a nation, and it would not until the Rosista regime fell in 1853, that a Constitution would be drawn up and the process of national organization would begin.Footnote 11 Although Rosas was a supporter of independence for each province under their own governments in a de facto union under the name of Federación (Federation) (which would proclaim the triumph of federalist ideals), he paradoxically consolidated the hegemony of Buenos Aires.Footnote 12 Rosas's intention to reinstate the colonial order led to his sobriquet, the ‘Restorer of the laws’.Footnote 13 This renewed sense of ‘order’ defied the liberal ideas promoted by the unitarians after independence (1810).Footnote 14 A group of dissenting intellectuals – known as the ‘Generation of 1837’ – formed during Rosas's second government to act as the critical conscience of the Rosista regime.Footnote 15 Over time, these dissidents constituted a strong opposition group, and became part of the unitarians.Footnote 16

Political historians and literary scholars have addressed this tumultuous period often,Footnote 17 and their excavations have uncovered the foundation of Argentinian literature in the novels and essays by these unitarians that necessarily denounced the actions of the Rosista government.Footnote 18 The historical binary of civilization and barbarism promulgated by the politician and writer Domingo Faustino Sarmiento to distinguish unitarians from federalists (as well as the city from the countryside) buttresses the dominant scholarly narrative that Rosas's period was bereft of the arts.Footnote 19

The unitarians contrasted Rosas's brutality with the sweet character of his daughter, the ‘angelic Manuelita’ (as she would be called in the 1917 opera by Eduardo García Mansilla). While unitarian depictions of Rosas were obviously unfavourable, their Manuelita was the image of pureness and civility, a victim of her father's cruelty.Footnote 20 After the death of her mother, Encarnación Ezcurra, in 1838, Manuelita represented the regime at social and cultural activities in Buenos Aires. As a member of high society, she attended the theatre and organized balls and tertulias for the federal aristocracy, events in which Rosas almost never took part.Footnote 21

In the final years of the Rosista government the economy started to grow (allowing the reinstatement of Italian opera in Buenos Aires) and political persecution gradually faded, due in some part to the dissolution of the Mazorca in 1846.Footnote 22 In a signal of regime support for the arts, Manuelita was a fixture at theatre performances in the late 1840s. But just as the Rosista regime seemed to relax its social and political mores, the Camila O'Gorman case would test its limits.Footnote 23

The Camila O'Gorman Scandal

In 1848, the case of Camila O'Gorman, a ‘young girl from a wealthy family’ who had eloped with a priest became a pressing issue among porteños,Footnote 24 including federalists and exiled unitarians. The two factions were united in viewing this affair as a moral crime.Footnote 25 The first person to inform Rosas about Camila's elopement was her own father, Adolfo O'Gorman, who repudiated the situation. In defying the laws of both country and church, the affair, in the words of O'Gorman, was ‘a scandal never heard of in this country’.Footnote 26 Two clerical figures (a priest and a bishop) also wrote to Rosas showing their concern and asking the Governor to intervene.Footnote 27 In the eyes of Camila's family, the priest in question, Uladislao Gutiérrez (a friend of Camila's brother Eduardo, also a priest),Footnote 28 had kidnapped the young girl.Footnote 29 In the eyes of the Church, Camila had seduced the priest and was thus the guilty party.Footnote 30 Rosas disregarded the letters from Camila's father and the two priests until exiled unitarians published articles blaming the (im)morality of Rosas's federal society as the cause of the elopement. In these articles, written by Valentín Alsina in the Comercio del Plata of Montevideo (Uruguay), Domingo Faustino Sarmiento in El Mercurio of Chile, and Bartolomé Mitre in El Comercio of Bolivia,Footnote 31 they argued that Camila was not to blame, but rather the federal government, which had corrupted the moral integrity of both the Catholic Church and its people, as well as the priest, who seduced and kidnapped the young woman.

In June 1848, several months after their elopement, Camila O'Gorman and Uladislao Gutiérrez were found in Goya in the province of Corrientes where – under fake identities – they were working as teachers at the town school.Footnote 32 Camila was almost eight months pregnant and yet, in spite of his awareness of this fact, Rosas sentenced her and Uladislao to death by firing squad. In a statement before the Justice of the Peace of San Nicolás de los Arroyos near Santos Lugares (where the lovers were executed), Camila asserted that she had not committed any crime. Assuming her own responsibility for initiating the affair with Uladislao Gutiérrez, Camila accepted her fate. According to María Teresa Julianello, Manuelita sent a letter to her father interceding on behalf of the couple. Julianello states that Rosas was enraged by Camila's complete lack of guilt, and told Manuelita that he needed to assert his power more than ever, being the moral and religious values of the whole society at stake.Footnote 33 Yet, according to Valentina Iturbe-La Grave, Manuelita was unable to intercede.Footnote 34 In his memoirs Antonino Reyes – Rosas's aide-de-camp in charge of Camila and Uladislao's execution – explains that he sent a letter to Manuelita so she could intercede on the couple's behalf, but the letter was delivered to Rosas instead.Footnote 35 Reyes also mentions a letter that Uladislao asked him to give to Camila, which, among other things, said: ‘I have learned that you will die with me. Although we were not able to be together on earth, we will be together before God in Heaven.’Footnote 36 Even though there is no surviving evidence of this letter, Reyes’ recollections underline how after their fatal end, the two lovers’ tragic romance captured the imagination.Footnote 37

Because of the social pressure on Rosas from the Church, the federal society and the unitarians, Reyes claimed that Rosas sought legal advice in order to justify the execution; especially since the law stipulated that a pregnant woman could not be executed.Footnote 38 Despite Rosas's (supposedly legal) decision, Camila's death still shocked contemporary society. It is evident that he made his decision in order to avoid any sign of weakness – as Julianello describes – especially when respect for him, built on fear and political persecution, was by this time on the decline.Footnote 39 However, following the execution, the unitarians’ views were tempered: they pitied the young couple, whom they came to see as ‘victims of passion’,Footnote 40 and used the execution to again accuse Rosas of despotic rule.Footnote 41 While the regime still presented Camila and Uladislao as fugitives accused of committing a ‘horrendous crime’,Footnote 42 the unitarians generated a romanticized depiction of the affair that remains well known even in the present day.Footnote 43 Almost a month after the unfortunate couple's execution, an opera company arrived in Buenos Aires. They were the first troupe in the city after an absence of nearly 20 years and would put on performances until Rosas's fall from power in 1852.

Opera in Buenos Aires

Full performances of opera began in Buenos Aires in 1825 during a period of strong cultural expansion.Footnote 44 Although some theatres performed French opera, Italian opera dominated the stages during the so-called período rivadaviano.Footnote 45 The works of Rossini took up an outsized portion of the repertoire, with Il barbiere di Siviglia being the first opera staged and the most popular. At this time there was only one theatre in Buenos Aires – the Coliseo Provisional – which during Rosas's time would be renamed the Teatro Argentino. The theatre was originally built in 1804 and closed for a few years until it was reopened in 1810.Footnote 46 According to Thomas George Love – at the time a British traveller who some years later would end up residing in Buenos Aires and becoming the editor of the newspaper The British Packet and Argentine News – at the top of the stage there was a sign that read: ‘Es la comedia espejo de la vida’ (‘Comedy is the mirror of life’).Footnote 47 Before an opera company arrived in 1825, the theatre mostly performed Spanish plays, including comedies, sainetes (farces), tonadillas and zarzuelas. These kinds of spectacles were seen as old-fashioned and linked with the colonial past, so, in an attempt to modernize the theatre, in 1817 a group of politicians and intellectuals created La Sociedad del Buen Gusto por el Teatro (Society of Good Taste for the Theatre). This society advocated for Italian opera (although at this time operas were not performed in full, but as excerpts) in order to ‘modernize’ and ‘civilize’ the theatre.Footnote 48

The opera seasons ran from 1825 until 1829, when the financial crisis and political situation in Buenos Aires drove the previously flourishing touring companies to seek their fortune elsewhere, resulting in a period of almost 20 years with no fully staged performances of operas.Footnote 49 This did not mean Italian opera was no longer performed, but rather that it took forms other than staged performances. During these years, operas were rearranged for domestic settings or potpourri concerts in which one or two singers with a piano and/or violin accompaniment would perform. The taste for Italian opera followed the European trends: by 1838 the romantic aesthetics of Bellini and Donizetti were preferred over the now ‘old-fashioned’ Rossini. This change of taste happened even though the operas had not been heard in their entirety or staged. The press reflected this change, with the musical journals Boletín Musical (1837) and La Moda (1838) publishing extensive articles on both composers, and fragments of the operas in piano and vocal versions circulated among the salons of Buenos Aires.Footnote 50

A new theatre was built in 1838. According to Vicente Gesualdo the interior of this new theatre, called the Teatro de la Victoria, was painted red to indicate its political association with the federalists.Footnote 51 A description of the theatre was published by Figarillo (the pseudonym of Juan Bautista Alberdi, a member of the ‘Generation of 1837’ and, thus, an opponent of Rosas's politics):

What can I tell you about my first impressions of the building's interior? It looks like a large aviary, it looks like an enormous bookcase or apothecary's cabinet, it looks like a parrot cage, a cistern … it looks like … I don't know what it looks like!Footnote 52

According to a chronicler from the English newspaper British Packet and Argentine News (possibly Thomas George Love), there was a sign attached to the proscenium of the Teatro de la Victoria that read: ‘Se reúne en este punto deleite y utilidad. Pugna la virtud y el vicio: y se enseña moralidad’ (‘Pleasure and purpose meet at this point. Virtue and vice struggle: and morality is taught’).Footnote 53 Given Rosas's general apathy for cultural activities, it is difficult not to imagine that this slogan was for the benefit of Manuelita Rosas and the young women from the federal elite who were regulars in the audience.

Although Rosas did not generally concern himself with the artistic life of the city, this changed in his final years of government. By 1847, in the words of Pilar González Berlando de Quirós, ‘the regime began to open up’, allowing a cultural renewal.Footnote 54 The reinstatement of complete Italian operas in Buenos Aires in these last years of Rosas's government provides an interesting facet of the role of the arts that remains almost entirely unexplored to date.Footnote 55 While Rosas himself was not interested in attending the theatre, federalist ideology was not absent from the stage or auditorium: during operas and plays, actors wore the regime's red ribbon and began performances by shouting the famous Rosista slogan ‘Viva la Confederación Argentina. Mueran los salvajes unitarios’ (‘Long live the Argentine Confederation. Death to the savage unitarians’).Footnote 56 Indeed, the Spanish chronicler Benito Hortelano recalled:

Another of the absurdities of those times [during Rosas's regime] was that in the theatres, before the start of each performance, all the artists appeared dressed as their characters but wore, over the costume of Carlos V, for example, or Nebuchadnezzar, the well-known federalist red ribbon. They had to form a single line in front of the audience, and the director shouted ‘Long live the Argentine Confederation! Death to the savage unitarians! Long live the Restorer of the Law! Death to the enemies of the American cause!’ Then the curtain would fall and the orchestra would start playing.Footnote 57

According to theatre historian Raúl Castagnino, from 1837 to 1848 stage performances were regulated by a Censorship Commission, which was dissolved by the government in 1848.Footnote 58 This did not denote the end of censorship, which was present until the end of the regime, but it suggests a certain laxity compared with the measures taken in previous years.

In this same year and under this political climate, Italian impresario Antonio Pestalardo brought to Buenos Aires an Italian lyric company that had toured in Brazil some years before.Footnote 59 With the exception of the first year, each year was divided in three seasons: the first season from April to July, the second season from July to October, and the third season varied each year.Footnote 60 The company performed exclusively at the Teatro de la Victoria, while the Teatro Argentino (formerly the Coliseo Provisional) was dedicated to performing Spanish plays and some variety concerts.Footnote 61

Between 1848 and 1851, most of the performed operas were by Donizetti and Bellini, with a few by Verdi, one by Mercadante, one by Nicolai and another by Ricci.Footnote 62 While Donizetti and Bellini's operas were broadly popular, the reception of Verdi's operas was somewhat mixed.Footnote 63 The selection of operas may have been limited to those already in the singers’ repertoire, and it was also likely affected by what critics and opera attendees expressed in the newspapers. By 1848 there were only four newspapers being published in Buenos Aires: The British Packet and Argentine News, La Gaceta Mercantil, Diario de la Tarde and Diario de Avisos.Footnote 64 The second (La Gaceta) was Rosas's mouthpiece and did not publish theatre reviews. Diario de la Tarde and Diario de Avisos were both federalist, but expressed their political views in different ways. They both published theatre reviews and generated several debates among opera attendees. The more combative readership of the Diario de Avisos often sought to nullify and demean opposing arguments with wanton accusations of unitarianism. The offensive tone of this newspaper led Pestalardo to remove his adverts from its columns, so he too was accused of being a unitarian.Footnote 65

The first opera staged in 1848 was Lucia di Lammermoor, the immediate success of which led to seven consecutive performances.Footnote 66 The first season of 1849 opened with Bellini's Beatrice di Tenda on 8 April, but premiered the same composer's Norma for the anniversary of the most important celebration of the country, the Independence Revolution on 25 May.Footnote 67 At the beginning of the performances held during national or Rosista celebrations, audiences shouted the federalist slogan (‘Long live the Argentine Confederation. Death to the savage unitarians’) and sang the National Anthem, along with the hymn ‘Gloria (o Loor) Eterno al Magnánimo Rosas’ (‘Eternal Glory to the Magnanimous Rosas’) (see Table 1).Footnote 68

Table 1 Operas performed during National and Rosista Celebrations, 1848–51

The Performance of Norma during Rosas's Regime

It was not the first time Buenos Aires audiences encountered Norma.Footnote 69 Excerpts had already been performed in the city, such as on 27 July 1839, when Justina Piacentini sang the famous aria ‘Casta Diva’ for the first time at the Teatro de la Victoria, inaugurated the previous year.Footnote 70 By the mid-1840s, news of the operas performed in Brazil (especially in Rio de Janeiro) reached the shores of the Río de la Plata through articles and letters from readers published in the local Argentine newspapers. Musically minded individuals of the Rosista regime may therefore have been aware of Norma's impact in Brazil, where it was performed seven times in 1844 at the Teatro São Pedro de Alcântara in Rio de Janeiro, starring the well-known Italian diva Augusta Candiani. The young female audiences in Brazil identified with Norma, who was seen as the prototypical model of a woman torn between duty and love.Footnote 71

The British Packet and Argentine News referred to the premiere of Norma in Buenos Aires in an article covering the celebrations of the May 1810 revolution:

After witnessing the splendid exhibition of fireworks in the Plaza the immense assemblage repaired to the theatres, which were literally crowded to suffocation, especially the Victoria, where, as if it were to mark an epoch, Bellini's grand opera–Norma–was for the first time brought out.Footnote 72

The packed theatre indicates the importance these gatherings had for Buenos Aires society and also confirms the excitement surrounding this particular opera.Footnote 73 If nothing else, audience members were eager to see two rival divas, Carolina Merea and Nina Barbieri, sing together for the first time. This rivalry between the divas could have been invented by the press, which in 1851 went on to foment a rivalry between Merea and Ida Edelvira before the latter even arrived in Buenos Aires.Footnote 74 Although I have been unable to find articles referring to the premiere beyond the one in the British Packet, after the second performance a review appeared in the Diario de la Tarde in which the writer recorded the opera's success and argued that Adalgisa's ‘unknown struggle between love and duty’ performed by Nina Barbieri ‘reached the same height as the passions that tore Norma’.Footnote 75

Between 1849 and 1851 Norma was performed in its complete version 20 times: 11 times in 1849 (between its premiere on 25 May and its final performance of the year on 11 October); once in 1850 (a second planned performance was replaced by another work in the repertoire due to the indisposition of one of the singers); and eight times in 1851, with the recently arrived soprano Ida Edelvira in the role of Norma (see Table 2).Footnote 76

Table 2 Performances of Norma, 1849–51

Despite not having many sources, based on the number of performances and what few reviews we have it is possible to assume that Norma's reception throughout the Rosas period was generally very positive. Some notable exceptions come from 1850, when some of the company's singers left the country and the roles were filled by stand-ins until new singers (including the soprano Ida Edelvira) arrived in 1851.Footnote 77 Inevitable personnel limitations also meant that Bellini's orchestration was treated as a suggestion rather than dogma. According to the Diario de la Tarde, for example, the military band instruments (presumably referring to the brass section) that should play in the introduction – as in Bellini's score – were unavailable until 1851 (likely due to a lack of musicians) when the original orchestration could finally be realized with the aid of a local military band, allowing the audience – already accustomed to a different sound – to form new impressions.Footnote 78 Despite the opera's 1850 problems, Norma reappeared with great success in the eyes of audiences and critics alike in January 1851, with a theatre ‘filled with distinguished ladies, notable among them Miss Manuelita Rosas who honoured the evening as well’,Footnote 79 and was again performed several times from March to September.

New political tensions arose with Justo José de Urquiza's (the federal governor of the province of Entre Ríos who would defeat Rosas in the Battle of Caseros in 1852) challenge to the Rosas government.Footnote 80 The federalist political play El entierro de Urquiza (The burial of Urquiza) by Pedro Lacasa was staged at the Teatro Argentino in July 1851 as an ultimate (and clearly unsubtle) expression of Rosista politics and the arts.Footnote 81 Looking at the plot of the operas performed in Buenos Aires between 1849 and 1851, Norma seems to bear a close resemblance with the tragic story of Camila O'Gorman, whose life tragically ended almost nine months before the opera's premiere.

The Moral, Political and Religious Challenge: Camila and Norma

The stories of Norma and Camila intertwine. Camila's break with prevailing moral values provided the ammunition for the opposing unitarians to charge the Rosista government with ‘morally corrupting’ the people of Buenos Aires. Norma's story explores a similar forbidden love – and its larger implications for the welfare of a people. Based on the French play by Alexandre Soumet and adapted by the prolific Italian librettist Felice Romani, Norma is the story of the eponymous Gallic priestess who falls in love with Pollione, the Roman proconsul, by whom she secretly has two children.Footnote 82 Where Norma betrays both God and country, in Camila's case it was the man, Uladislao, who betrayed God (although both were sinners in the eyes of the Rosista regime).Footnote 83 Norma also has a third party: Adalgisa, a priestess who falls in love with Pollione but abandons him after Norma reveals her own love affair with the Roman proconsul.

Even though the resemblance between the female protagonists of the two stories may be perceived as a mere coincidence, performances of the opera during regime celebrations and the differences found in the Buenos Aires libretto in comparison to others during a tense political period, imply several connections between the stories that could yield a similar moral lesson for local audiences. Despite the condemnation of her elopement, the execution of Camila was shocking to contemporary society. It is possible that presenting a manipulated version of the opera may have symbolically offered a rebellious alternative to the regime's rigid morality. As explained, Camila felt no guilt for her actions and accepted her fate. In the opera, the Gallic priestess decides to sacrifice herself, to find redemption in the wake of religious, political, and moral betrayal. This is clearly acknowledged by the Italian phrase in Stendhal's novel Le Rouge et le Noir which Catherine Clément quotes with regard to the woman's role in opera: ‘Devo punirmi, se troppo amai’ (‘If I loved too much, I should be punished’).Footnote 84 Both heroines Norma and Camila died because they loved too much. It also reinforces the Romantic trope of the lovers’ reunion in heaven, which resonates with Uladislao's last letter to Camila. The proper young women of the federal elite were clearly challenged by the passion imbuing both Camila's story and those of the female characters that they saw on stage some months after her death. The sign placed on the proscenium of the Teatro de la Victoria reminded them each time they attended that in the theatre: ‘morality is taught’.

But we can read further between the lines when it comes to the performance of Norma under Rosas's government. The ordinary censorship imposed on all plays in different places around the world reflected a direct political affiliation between the production of art at the time and the aims of the regime.Footnote 85 Norma is a clear example of the combination of religion and politics in which both antagonistic forces (the foreign domination in Italy and the local revolutionaries), are represented through two main characters: Pollione, a character of doubtful morals who belongs to the Roman militia, and Oroveso, a Druid high priest who executes the law with the utmost rigor, to the extent that he even sentences his own daughter.Footnote 86 The parallels with the contemporary political situation seem unavoidable: Pollione can be read as a unitarian or political and moral enemy, and Oroveso as a federalist (and also as a representation of Camila's father Adolfo O'Gorman).

The dyadic relationship of Gallic/federalists and Romans/unitarians may also be identified from a contemporary narrative written by an exile that mentions the performance of the Italian opera on the Buenos Aires stage. According to several sources, an article attributed to Miguel Cané, Sr was published in several issues in the Comercio del Plata of Montevideo between 15 and 20 July 1850.Footnote 87 The satirical article gives an account of a trip to Buenos Aires by a foreigner, who attends a performance at the Teatro de la Victoria after visiting Rosas's residence, the Estancia in Palermo.Footnote 88 Although the opera is tangential, a couple of relevant details are recorded: first, the traveller attends a performance of Norma; second, at the beginning of the opera the foreigner draws the attention of his partner – a porteño federalist – to the fact that the Druids, the Gallic priests, are wearing the red federalist insignia, the divisa punzó. Footnote 89 It also mentions that the performance could not start until Manuelita arrived, with the commentator remarking (ironically) that it was as if she were a new prima donna.Footnote 90 This narrative is based on established facts, as Miguel Cané had been in Buenos Aires a month before the release of the article. Because of Cané's personal enthusiasm for Bellini, Norma's mention in the story highlights Cané's attendance at the opera during his stay in the city more than any attempt to emphasize its politicization. Although Cané does not mention particular aspects of the performance, he understood the political symbols used in the staging.

Differences in the Libretto

Focusing on the opera's libretto as published in Buenos Aires, I uncovered several differences that could have helped in supporting a political or moral meaning. As is well known, far from being static fixed documents, nineteenth-century librettos varied depending on circumstances and individual performers.Footnote 91 In this particular context, I will compare the libretto used in Buenos Aires (NBA)Footnote 92 with the ‘original’ (NO),Footnote 93 and also with two almost contemporary versions of the Buenos Aires performance: one to be staged in Spanish theatres and published in Madrid in 1841 (NM),Footnote 94 and another one published in Venice to be staged at the Teatro La Fenice during 1844–45 (NI).Footnote 95 I will analyse in detail the most notable differences in meaning, among other changes in structure, such as act and scene divisions, and variants in the text distribution over duos and/or trios. When compared, the literary content of the libretto published in Madrid coincides almost exactly with the one printed in Buenos Aires, suggesting that the libretto came via Spain instead of Italy. Yet, by looking at the few available sources – such as Manuelita's musical notebooks containing excerpts of Norma replicating the Italian version – it is possible that the libretto from Madrid was chosen over the Italian in order to better align with Rosas's agenda (or was a better ‘translation’ of Rosista values). There are a few structural differences between the Buenos Aires and the Madrid librettos that further point towards a local adaptation or use of other foreign variations in the latter, as I will show below.

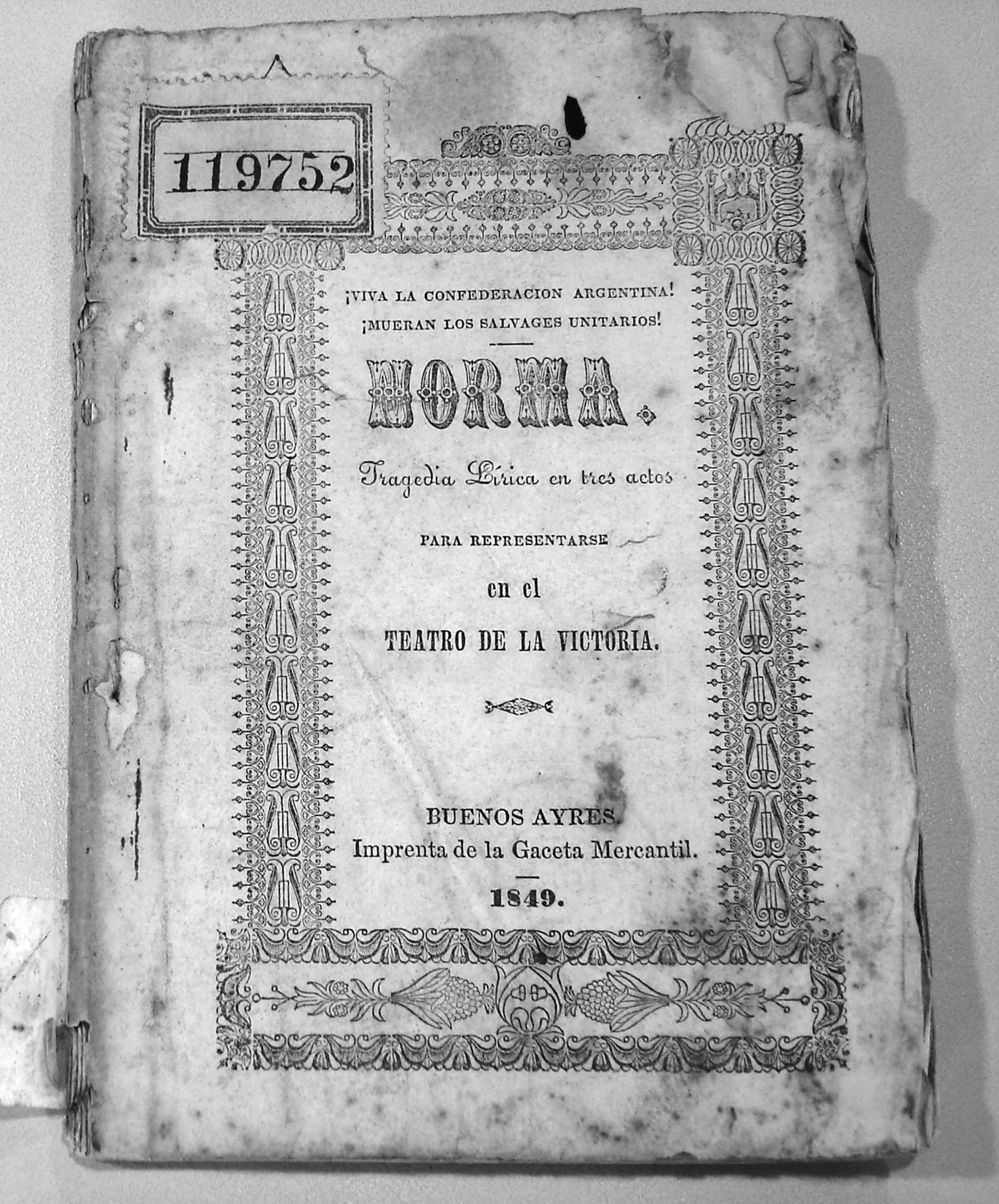

The cover of the Buenos Aires libretto indicates it had been printed by the Imprenta de La Gaceta Mercantil, Rosas's mouthpiece (see Fig. 1), which is a relevant detail given that some previous opera librettos had been edited by the Republicana and De la Independencia printing presses. Although most newspapers of the time were ‘official’ in some way, this publication reflected the direct intentions and influence of the Governor.Footnote 96

Fig. 1 Norma: Tragedia lírica en tres actos (Buenos Aires: Imprenta de la Gaceta Mercantil, 1849), front cover. Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional Argentina ‘Mariano Moreno’ (Libros, Colección General, S2BG291209AT)

In perusing the cast list on the first page, what catches the eye is that Adalgisa is featured as ‘Pollione's lover’, a description that pointedly omits the phrase that follows in the other librettos: the ‘young priestess’. This particular exclusion, also omitted in the Madrid libretto, would be particularly relevant to the porteños, who could have seen in Adalgisa's ‘secularized’ moral conundrum a corrective to the O'Gorman scandal, emphasizing for the impressionable federalist women that they must choose duty (that is faithfulness to the fatherland) over passion.

The libretto is divided into two sections with the text in Italian on the even pages, and the Spanish translation on the odd pages. In Act I Scene II,Footnote 97 in the dialogue between Pollione and his friend Flavio, the Roman Proconsul reveals that he no longer loves Norma, the mother of his children, but rather a young Gallic girl named Adalgisa. The text in this part of the Buenos Aires and Madrid libretto reads: ‘Qui nel tempio/ Di questo dio di sangue, ella vi appare/ Come raggio di stella in ciel turbato’ (‘Here in the temple of this bloody god, she appears as a star's bright beam through an unsettled sky’).Footnote 98 While in the other librettos Pollione says: ‘Ministra al tempio/ Di questo dio di sangue,/ Ella v'appare/ Come raggio di stella in ciel turbato’ (‘She is a priestess in the temple of this bloody god; she appears as a star's bright beam through an unsettled sky’).Footnote 99 This is further evidence of the intentional omission of Adalgisa's role as a priestess.

In the fifth scene (of the NO version), Adalgisa is alone and says: ‘Sospirar non vista alfin poss'io,/ Qui … dove a me s'offerse/ La prima volta quel fatal Romano,/ Che mi rende rubella/ Al tempio, al dio’ (‘At last I can sigh unseen, here … where he first came to me, the fatal Roman whose love made me a traitor to the temple, to god’).Footnote 100 In the local and Madrid versions, the mention of the temple and God has been excluded and instead, it reads only: ‘Che mi rende rubella … Oh dolor mio!’.Footnote 101 In the Spanish translation of the NBA libretto this sentence has been discarded.Footnote 102 At the end of this scene Adalgisa says: ‘Deh! proteggimi, o Dio: perduta io sono’ (‘Ah! protect me, o God: for I am lost’). This phrase appears in the Italian and Madrid librettos but not in the Buenos Aires one.Footnote 103

In the next scene, Pollione tries to persuade Adalgisa to elope with him. She refuses and reminds him of the vow she took: ‘To the temple, to the holy altar whose sworn bride I am’ (‘Al tempio,/ ai sacri altari/ Che sposar giurai’) according to the original text.Footnote 104 However, in the Buenos Aires and Madrid librettos, Adalgisa wants Pollione to stay away from her and the temple verse does not appear.Footnote 105 These examples are a sampling of such changes, leading to the end of this first act (according to the NBA version, in which the opera is divided into three acts, but not the NM, NO and NI which are divided in two), when Pollione and Adalgisa sing a duet. She says: ‘Alla patria mia spergiura,/ Ma fedele a te sarò’ (‘My fatherland I shall renounce; but to you I will be faithful’), and he says: ‘L'amor tuo mi rassicura,/ Tutto omai sfidar sapró’ (‘Your love reassures me, I shall dare to defy everything’).Footnote 106 In the original version, the words of Adalgisa are: ‘Al mio Dio sarò spergiura,/ Ma fedel a te sarò!’ (‘My God I shall renounce, but to you I will be faithful!’); and Pollione says: ‘L'amor tuo mi rassicura,/ E il tuo Dio sfidar sapró’ (‘Your love reassures me, and your God I will defy!’).Footnote 107 In the Buenos Aires libretto, in contrast with all the others, the first act concludes here, creating a three-act division instead of two. This could have been a local variant, or could have been copied from other foreign versions, since other librettos divide the opera into three acts.Footnote 108 Whether it was a local or a foreign variant, it is possible to believe that this particular division was used for a particular dramatic effect: while the curtain at the Teatro de la Victoria was being lowered, Adalgisa's words on defying her fatherland reverberated among spectators – especially among the young women of Buenos Aires, who would have seen in Adalgisa's words the struggle between ‘virtue and vice’ that could be read on the sign hung on the proscenium.

At the beginning of Act II Scene II of the Buenos Aires libretto, and Act I Scene VII of the other three, Adalgisa confesses to Norma that she is in love, and that she is about to leave everything behind and run away with her lover. During this confession, any references to her broken vows are also omitted, but the mention of leaving the country remains. Towards the end of the scene, Norma expresses happiness for her, without knowing that Adalgisa's love is Pollione. In the original version, Norma frees the young priestess from her vows,Footnote 109 but in the NBA and NM librettos, this line appears again to be deliberately omitted. In these librettos, when Norma asks Adalgisa about her lover's name, she assumes that her crime is that she has fallen in love with a Roman soldier, whereas in the NO libretto his nationality is indicated without evincing any guilt on her side.Footnote 110

The next scene represents the end of the first act in the original version (as well as the NI and NM), and of the second act in the Buenos Aires version. It consists of a trio sung by Norma, Adalgisa and Pollione, in which the love triangle is revealed. Here there are textual differences which, although not significant, show the resemblance between the local and Spanish libretto, as well as the differences from the original and La Fenice versions. Among the manuscript scores found in one of Manuelita Rosas's notebooks dated 16 July 1847 (held in the Museo Histórico Nacional), this trio appears in a piano vocal score with the same text as the original libretto. It differs slightly in musical and formal terms from other piano-vocal score reductions of the opera, and of the librettos for the full score.Footnote 111 But the text is exactly the same. This suggests that there may have been different versions of the libretto circulating in Buenos Aires: a version used for the stage production and specially sold for the Teatro de la Victoria performances, and others that circulated through the scores. While it seems that the libretto used for the theatre could have been copied from the Madrid version, the act/scene differences as well as some minor deviations from the latter, could lead us to conclude that the Buenos Aires edition spliced together the Madrid libretto with other foreign editions, or be an indication of some sort of local adaptation.

At the beginning of the second act of the original libretto, a vengeful Norma enters her children's bedroom with a dagger in her hand, but, horrified by her intentions, she backs down and filicide is averted.Footnote 112 In the NBA and NM versions, at the beginning of the third act no mention is made of a dagger in the stage directions, nor is Norma's impulse to kill her children suggested.Footnote 113 In addition to ‘smoothing’ the story for the general opera-going public, this omission could have served to prevent the audience from recalling the death of the child Camila O'Gorman was carrying when she was killed. Another significant change is when Norma tells Pollione that, if Adalgisa is unfaithful to her country, she will have to be sacrificed.Footnote 114 This is in contrast to the NO version, in which she is unfaithful to her vows. Finally, in the last scene of the librettos, Norma reveals her betrayal to God and to her country and decides that it is she who must be sacrificed. Moved by her altruism, Pollione decides to die with her in the flames.

Based on the differences listed above, it seems that the NBA replicates the NM intentions of removing all signs of religious connotation from Adalgisa's character. This could be, on the one hand, to differentiate her from Norma and, on the other, to emphasize the betrayal to her country. Adalgisa is a banal character ready to do anything in the name of love, but through Norma's teaching she becomes aware of the fatal error she is about to commit, and decides against it. I believe that Adalgisa's role in the plot functions not so much as part of the love triangle, but as Norma's alter ego; she represents Norma in her youth and Norma can see herself in Adalgisa. Norma is inclined to set the example and decides that she is the one that must be sacrificed. David Kimbell states that the love triangle in the opera Norma is not that of conventional romanticism but of a psychological plot, in which there is no external danger typically represented by a tyrant, and that the development of the story claims for new insights into the national aspect.Footnote 115 This interpretation, consciously or otherwise, supports a stance that reinforces the decision to perform the opera as a political one on the part of the Rosista government, which ultimately aims to remove any suggestion of blame towards political power as incarnated by Rosas. If, as Paolo Cecchi suggests, Bellini's Norma anticipates the Romantic and private dramas of the bourgeoisie (adultery, treason, possessive and filial love), then Rosas's Norma makes it a reality.Footnote 116

Conclusion

Performances of Bellini's Norma in mid nineteenth-century Buenos Aires offered new interpretations of the opera in relation to local political events that took place during Rosas's government. We could highlight that the changes made to the character of Adalgisa emphasized the moral-political behaviours of the time. She is not invested with a sacred feminine dimension as in the case of Norma; rather she is represented as an ordinary woman seduced by a man, whom she later perceives to be immoral and corrupt. Thanks to Norma's example, Adalgisa avoids betraying her fatherland and therefore avoids Camila O'Gorman's ignoble end, unlike Norma herself.

In a single character Norma embodies all possible means of betraying established social values. There is no other possible ending than that of her death, not only because of the judgment of others but because of her guilt, which spurs her to choose duty over love. It seems that the modifications of the libretto in Buenos Aires were meant to serve as a warning for the young female audience not to follow in Camila/Norma's steps. Thus, in an indirect way and in concordance with the message echoing over the proscenium throughout the entire performance: ‘Pleasure and purpose meet at this point. Virtue and vice struggle: and morality is taught’. The performance would become in some way a moral lesson, turning each national or federal celebration in which Norma was performed into a perpetuation of this message.

There is, as noted above, a scholarly void on the history of Italian opera in mid-nineteenth-century Argentina. The scarcity of sources is clearly one of the main reasons for this neglect. There are no surviving scores except for Manuelita Rosas's own music books, the librettos, and some reviews in the newspapers. Yet in contrast with the historiography that has portrayed the Rosista period as completely lacking cultural activities, my reading of the source, and the possible connections I have drawn between Camila's story and Bellini's Norma, contribute certain proof that this period was much more nuanced than has hitherto been asserted. In this way, the study of opera in Argentina can unveil new perspectives for the country's own (music) history, as well as contributing to the wider global history of nineteenth-century opera.