The coexistence of diverse musical cultures and intensive absorption of influences from abroad seem to be the chief characteristics of the nineteenth century in Bucharest. The city boasted a strong social and multi-ethnic dynamic, and its professional and institutional structures leaned towards westernization.Footnote 1 Migratory streams were open in both directions: on one side, young Romanians left for studies in ‘Europe’, and on the other, foreigners – Italians, Germans, English, French and Austrians – settled in Romanian territory in large numbers. Numerous foreign musicians were active in Romania, where they contributed to the make-up of princely military bands, philharmonic societies, musical theatres and conservatories.

By 1900 the centre of Bucharest had the glitter of a true capital city, with a European style of life and a cosmopolitan bourgeoisie receptive to the new, but a century earlier, in 1800, the picture was very different. What differed was not the splendour and opulence of the rich townsfolk or the level of education enjoyed by the upper classes (trained according to the principles of Greek higher education), but rather the type of education and the almost complete enclosure within the patriarchal traditionalism of the ‘oriental’Footnote 2 world. Mobility, communication with the West, the bourgeois revolution, reforms, the founding of the new state of Romania from the union of Wallachia and Moldavia (1859), and its transformation into a Kingdom under a sovereign from the House of Hohenzollern (1866) were to change things radically. By the end of the nineteenth century, Bucharest had been transformed from a city with a multi-ethnic petty bourgeoisie to one with an haute bourgeoisie interested in concert music. But if fin de siècle cosmopolitanism differed from the multi-cultural patchwork of the first decades of the century, then this was due to a profound change in the Romanians’ self-image.

The Boyars and Bourgeoisie in Multi-Cultural Bucharest

Numerous studies have shown the importance of travel literature in gradually shaping knowledge of the Balkans and South-East Europe in the nineteenth century.Footnote 3 It was thanks to travellers, scientific expeditions and diplomats that the West ‘discovered’ Turkey and Greece before it did the Romanian Lands, which were regions of transit and at the same time the periphery of three empires keen to extend their influence: Ottoman, Austrian and Russian. Bucharest was situated in southern Wallachia, approximately 39 miles from the frontier post with the Ottoman Empire (now the border with Bulgaria) at Giurgiu, on the northern bank of the Danube.

Despite including some superficial, subjective, incomplete and even fictive information, the accounts left by foreign travellers abound in observations of foreign elements in the local society.Footnote 4 Whether in transit through the Romanian Lands or settled there temporarily, the authors describe the life of the local inhabitants with an eye for the exotic. The snapshots of everyday life are sometimes random and subjective. The quotations are descriptive and do not go deeper than the surface. Taken together, they constitute not a page of history, but only brief fragments. Nevertheless, these fleeting views combine to provide a coherent image, redolent of the ambience of the age, in which may be glimpsed the musical habits that formed a part of the social lives of the people of Bucharest.

The topos of diversity is also to be found in highly different contexts in travel diaries. It was not difficult to observe that the very composition of society itself was heterogeneous, and dwelling places, costumes and customs were eclectic. The language spoken in the towns was ‘mixed’ and, like costume, displayed ‘the most bizarre combination’Footnote 5 of Slavic, Turkish and demotic Greek elements, alongside French, Italian, German and other new influences. This eclecticism extended to musical practices. Even if musical pursuits did not especially draw their attention, Western travellers often describe elements specific to their own cultures (e.g. music-making at home, opera performances), which they were surprised to encounter in such a faraway land. Furthermore, the authors frequently point out the presence of foreigners and non-Romanian ethnic groups, perhaps due to their economic significance.Footnote 6 Although the statistical figures they provide are inaccurate,Footnote 7 they help us to outline the socio-historical background of the musical pluralism we shall discuss below.

About the demography and ethnic makeup of the city of Bucharest, travellers remark upon the foreign element in every social stratum, from landowners and bankers to the common people. For example, an epistolary report sent to the Prince of Wallachia, Ioan Gheorghe Caragea (1754–1844, r. 1812–18), by his former secretary François Recordon, lists the ethnic groups that made up the population of Wallachia: ‘More than 80,000 individuals who are absolutely foreign to the nation, being for the most part Greeks, Armenians, Germans, Russians, Jews, Serbs, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Transylvanians and even Frenchmen and Italians, and finally the race of Gypsies’.Footnote 8 F.G. Laurençon, who learned to speak Romanian during the 12 years he spent in Wallachia, claims that the political class is largely of foreign origin,Footnote 9 and refers elsewhere to many of the Greek merchants, bankers and language teachers employed as tutors in boyar households.Footnote 10 Eugène Poujade describes the Jewish minority, who were granted religious freedom but forbidden to own land. In the provinces, the Jews were segregated from Christian society, but in Bucharest, according to Poujade, ‘Jewish bankers are received in every house’.Footnote 11

Music mostly played a secondary role in travellers’ accounts. Like a leitmotif, the foreign element complemented the native at every social level, be it in the ceremonial of welcome or in the atmosphere of parties. The diversity of influences that coloured the locals’ habitus is not merely a backdrop here, but a constitutive part of musical culture.Footnote 12

As travellers chiefly came into contact with the boyar class, we shall first look at the music played within public and private settings in the upper echelons of society. In Romanian, the word ‘boyar’ denotes both a landowner, not necessarily of noble lineage, and a holder of a high position in the state (dregătorie),Footnote 13 conferred by the ruling prince along with a noble title and exemption from taxes. Although the noble titles were not hereditary, in time a ‘grand boyar class’ arose (2.2 per cent in Wallachia according to a statistic from 1859),Footnote 14 made up of families that held high positions at court over successive generations. The middling and petty boyars (boiernaș) were regarded as being of low rank. The different levels of the boyar titles had been established by the eighteenth century, and in the nineteenth century the boyar class included individuals of varying degrees of wealth, some of them coming from a bourgeois or even peasant background. Rich merchants and bankers were part of the upper class in the towns, but as they were not exempted from taxes they were not ‘boyars’ in the proper sense. The closeness between the boyar class and the bourgeoisie in the nineteenth century resulted in a similar lifestyle, and was maintained by the procedure for obtaining titles and positions. In the mid-nineteenth century, shortly before boyar privileges were abolished, honorific titles were still being bestowed: for example, kappelmeister Ioan Andrei Wachmann received the title of Pitar al Valahiei (Pitar of Wallachia).Footnote 15

In the present study I shall look mainly at the musical preferences and practices of educated city dwellers; the focus of the research will be not the boyars but the bourgeoisie. After 1821, the open border drew to the Wallachian towns foreign entrepreneurs and merchants knowledgeable in the various trades that were then in demand. These immigrants included dozens of writers, artists, musicians and private tutors, who can be found in the public and private records of life of Bucharest in this period.Footnote 16 From a sociological perspective, immigration therefore contributed to a growing urban bourgeoisie that frequented theatres, concerts and the like, and also made music in their homes.

Although European elements were few, the mixture of ethnic influences and the hybridity and eclecticism of everyday life were striking, even prior to the 1820s and the wave of reforms that would later be unleashed.Footnote 17 In the first phase, European music and dances found their way to the salons of the Romanian boyars thanks to contact with Russian officers during the occupation of 1806–12.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, the move towards ‘Europe’ was possible only when the grip of Ottoman power,Footnote 19 which had restricted communications with the West, had loosened. Over the course of the following decades, not only was the musical and artistic scene largely made up of foreigners, but numerous ‘musical products’ were imported from the West. Demand was on the rise for imports of all kinds, especially musical ones from centres such as Paris, Vienna and Leipzig. At the same time, older musical traditions (examined briefly in the sub-section that follows) continued to thrive.

Diversity of Musical Pursuits: Brief Overview of the Main Categories of Non-Western Music

Before recreating the period atmosphere and the social context of musical practices with the help of travel diaries, let us look briefly at the characteristics of the various categories of non-classical music, which will be discussed below: folk music from the Wallachia region,Footnote 20 the music of the lăutari (fiddlers), and so-called ‘oriental music’.

Regional or folk music was drawn from the musical repertory of the peasantry of Wallachia, including the particularly rich folk culture of Oltenia. This repertory began to be familiar to the educated urban class in the nineteenth century via songs and dances in particular: numerous folk quotations are to be heard in pieces for piano, orchestra and musical theatre. Although rural in origin, these melodies were collected from urban lăutari Footnote 21 by musicians with a European musical education, most of them immigrants to Bucharest working as instrumentalists, conductors or music teachers. They recorded the melodies without any indication of their source and without the original words. They also altered the melodies: stylizing, simplifying and adapting them to the Western musical system, to the notation and acoustic properties of the instrument/orchestra available, to the didactic demands of their pupils, and to public expectations.Footnote 22

The lăutari were usually Gypsy slaves or freemen. They lived and performed in villages as well as towns, and thus brought elements of the village repertoire to the boyar houses and to urban entertainments of every kind. Music was their profession, and they excelled as virtuosos, performing and recreating various melodies through improvisation and variation. In the nineteenth century, besides virtuoso improvisation in chromatic and folk modes, the music of the lăutari also encompassed ‘fashionable’ European genres such as romanzas, patriotic revolutionary songs and opera arias, and the lăutari passed on village melodies in versions that they altered to a greater or lesser extent. Mostly accompanied by a taraf, a small instrumental ensemble usually consisting of violins, pan pipes and a cobza, fiddler music presented a stylistic mélange of Turkish, Balkan, European and folk elements.Footnote 23 In 1864 Bucharest writer and musical journalist Nicolae Filimon described such hybrid musical works, which he claimed were fashionable between 1830 and 1858, as ‘amphibious compositions’, the results of a multi-cultural syncretism.Footnote 24

Finally, ‘oriental music’ is a vague and general term that denotes a repertoire of Constantinopolitan origin and its influences on the local musical culture. In this category may be included a secular repertoire consisting of vocalFootnote 25 and instrumental pieces generally described as Turkish or Greek, and sometimes even as Persian or Arabic, which were familiar to and enjoyed by the boyars, who sometimes also performed them on instruments associated with oriental classical music.Footnote 26

We find the most eloquent examples of local/regional and non-European influences on the secular vocal music of nineteenth-century Bucharest in the ‘worldly songs’ that set anonymous folk poetry and poems by Greek and Romanian authors.Footnote 27 Such ‘mixtures’ of post-Byzantine melos and Romanian folk music – of ‘oriental’ and European – can be found in the collections published in 1850Footnote 28 by Anton Pann, a musician wholly characteristic of the Bucharest of the first half of the nineteenth century, who in addition to Romanian spoke Turkish, Greek and ‘a little Russian’.Footnote 29 As I shall argue below, the worldly songs in his collection were popular at boyar balls, meals, weddings, garden parties and promenades in parks and vineyards. And the genre was enjoyed not only by boyars, but also by the capital’s poorer inhabitants. Worldly songs were performed by lăutari or cantors educated in post-Byzantine schools of church music and might be accompanied by a cobza or by a taraf. Like fiddler music, the genre – situated at the intersection of the classical music of the eighteenth-century Greek-Turkish elites and the Wallachian folk song and European ballad – incorporates a host of styles, themes and styles of playing. Nevertheless, unlike fiddler music, which was transmitted orally, and therefore closer to the sphere of ‘folk’ music, the worldly songs were in large part cultured creations, composed and/or notated by literate musicians, using post-Byzantine notation. Literary historians apply the term ‘worldly songs’ to poems from the period between 1800 and 1830, the texts in question being mainly love poems; in general, the epithet ‘worldly’ (de lume) points to the poems’ non-religious nature. Their musical vestment was essentially Greek/Turkish/Persian/Arabic, to which were added village or European influences. These European influences were similar in character to ballads or opera arias. There were different varieties or sub-genres of the worldly song, whose titles now have a distinctly old-fashioned flavour: cîntare veselitoare (gladdening song), versuri desfătătoare (delightful verses), cîntec de soţietate (society song), romansă (romanza), irmoase ce se cîntă după masă (religious hymns to be sung after dinner), cînt teatral, cîntec de mahala (suburban song), cîntece de petrecere (party songs), canţonete (canzonettas).Footnote 30

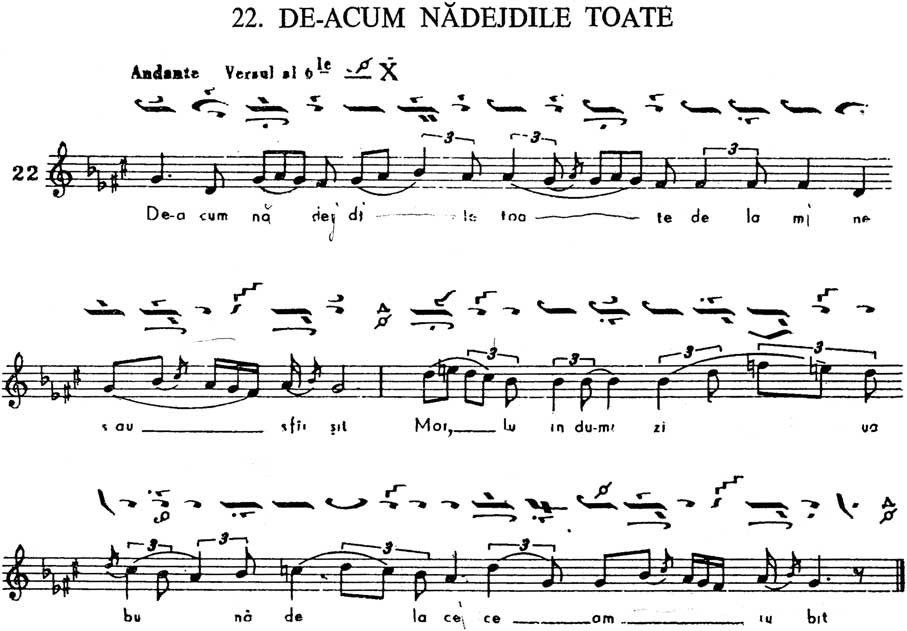

Let us look at a ‘worldly song’ that shows the influence of ‘oriental’ music (Ex. 1): a setting of a poem by Costache Conaki (1777–1849), from the Olimbiadi Monahi Tudori manuscript.Footnote 31

Ex. 1 ‘De-acum nădejdile toate’ (Henceforth all hopes), transcribed from the psaltic notation by Gheorghe Ciobanu in Izvoare ale muzicii romanesti, vol. 1, p. 243.32

The Footnote song has four melodic lines with the following text:

The song is written in the sixth mode (ᾖχος)Footnote 33 with the tonic on G (di according to the names of the steps in the Byzantine modesFootnote 34 ), exceeding the range of an octave, and therefore corresponding to the larger scale, which occasions modifications in the intonation of some of the steps.Footnote 35 The first, second and fourth lines are written in the chromatic scale of the sixth voice (tetrachords 1 and 2), with the tonic of G. Given that some notes are missing from the tetrachords of the scale or are altered, the melody is partly de-chromaticized (lacking the specific chromatic step, i.e. augmented seconds). Lines two and four end with a repeated cadence. Chromatism is present in the third line, which unfolds in tetrachord 2 and the upper modified tetrachord. On the word ‘bu-nă’ there occurs the enharmonic phthora agem,Footnote 36 indicating the intonation of a quarter tone from c (ni) to h (zo), i.e. a higher, untempered b.

Researchers Gheorghe Ciobanu and Vasile Nicolescu distinguish ‘oriental’ worldly songs from those that are obviously of ‘Western’ influence given the structural particularities of the former: rich ornamentation; binary metre; irregular accents; lack of metrical pulsation; possibly uneven divisions (groups of melismatic notes intoned on a single syllable, like triplets, quintuplets or asymmetrical formulas); form lent by the melodic lines; use of specific scales and cadences; major or minor diatonic modes (êikhoi), e.g. Dorian on D or Phrygian on E;Footnote 37 various chromatic modes, where augmented seconds occur, with transitions between modes, between diatonic–chromatic and inflections in so-called ‘enharmonic’ modes, characterized by quarter tones (named agem, hisar Footnote 38 and nisabur).Footnote 39 Songs with ‘Western’ influence (see Ex. 2) reveal mainly diatonic intonations (but not excluding the chromatic, just as the ‘oriental’ songs may also have lengthy diatonic passages), a tendency toward syllabic (less ornamented) melody, possibly symmetrical rhythmic/melodic motifs, divisible rhythms, and regular metre.Footnote 40 The mode of the song ‘Tu-mi ziceai odată’ (Ex. 2), described as a ‘romanza’ in Anton Pann’s collection Spitalul amorului sau Cîntătorul dorului (The Hospital of Love or the Singer of Yearning),Footnote 41 corresponds to the scale of d minor harmonic, and the fourth step (G♯) is fleetingly raised (bar 7). The text is by C.A. Rosetti, a poet and publicist, and one of the boyars’ sons who led the 1848 Revolution in Wallachia. It is a love poem, the lament of a lover wounded by an unfaithful mistress. I quote only the first four lines:

Ex. 2 ‘Tu-mi ziceai odată’ (Thou once used to tell me), transcribed from the psaltic notation by Gheorghe Ciobanu in Izvoare ale muzicii romanesti, vol. 1, 251 and 258.

Musical Practices in the Context of Everyday Life

Against this backdrop, we may view musical practices in the everyday life of the people of Bucharest as those practices were observed by foreign travellers.

Music in the Home

In the spring of 1812, Count Auguste de Lagarde noted that at the table of Ban Brîncoveanu, the host’s daughters ‘play the piano and the harp, sing in Greek or Russian, and even dance’.Footnote 42 During another visit to a boyar of Bucharest, where one of the guests played ‘Greek arias’ on the piano, Lagarde noted that the meal was served ‘in the French style’.

In 1818, physician William Macmichael,Footnote 43 a former student of Oxford University, arrived in Bucharest on his way from Moldavia to Constantinople. During a visit to the princely court, the prince and his daughters sat cross-legged on a divan; the guest witnessed promenades and card games. Around the year 1821, Laurençon noted that European music instruments were attracting increasing interest on the part of the nobility. He met violin, guitar, flute and piano teachers, who complained of the conceitedness of pupils who believed that once they learned to play a waltz or a quadrille they were consummate musicians.Footnote 44

In the spring of 1824, Karl von Klausewitz, an adviser with the Danish legation, described the modest level of women’s musical education, although it was of interest to women who influenced musical taste. He reports that Romanian women converse in French and dance the Polonaise, the waltz and English measures, as well as the local horă (ring dance).Footnote 45

But by the 1830s, the dominant influences were French, as noted by Marc Girardin, a young writer and later professor at the Sorbonne, who arrived in Wallachia after travelling down the Danube from Germany in 1836.Footnote 46 Similarly, William Rey finds that the Romanian affinity with France was a cultural option: ‘The Wallachian boyars have borrowed from the French everything that makes them closer to the peoples of the West’.Footnote 47 Rey observes that in idolizing Parisian fashions, the boyars believed that they could demonstrate their Latinity, but he also sees the educational side of things: in most families French was spoken with the same ease as Wallachian or Greek, and in most houses there were native French tutors, as is also confirmed by Stanislas Bellanger, who was in Bucharest in the same period.Footnote 48 Also in the 1830s, Frenchman Raoul Perrin wrote that Romanian women were ‘excellent musicians’ and conversed ‘in a French as pure, correct and choice as that of the inhabitants of Blois’.Footnote 49

Accounts of domestic musical practices signal the earliest penetration of Western influences, via the education of young ladies, who were either sent to boarding schools, where they learned music and ‘modern’ dances, or entrusted to private tutors hired from abroad.Footnote 50 The students or tutors kept handwritten notebooks of favourite musical pieces. Some are written in psaltic notation, others in linear notation, with the melodies usually being for piano.Footnote 51 Most of the notebooks that have been preserved in libraries in Romania date from the period 1830–1850, and they confirm the musical preferences described by travellers. The manuscript album Chansons et Danses Grecques, Des Postreffes et Chanson Turque, Airs et Danses Wallaques composées [pour] le Piano-Forte Footnote 52 illustrates the variety of the musical influences present in the private settings described in the travellers’ accounts.

The album demonstrates the popularity of the Romanian horă, which was also mentioned by Clausewitz. Hore appear frequently in a lively![]() metre, alongside dances termed ‘walaque’ or songs that betray a lăutar origin. I shall look at a few of the Wallachian songs and dances, which convey the particularities of the local musical culture at that time.

metre, alongside dances termed ‘walaque’ or songs that betray a lăutar origin. I shall look at a few of the Wallachian songs and dances, which convey the particularities of the local musical culture at that time.

The horă is the result of a cultural transfer from village to town. Along with the Sîrbă and the Brîu (a men’s dance), it was one of the most widespread mixed-group folk dances in Wallachia. Most were danced in a circle or semi-circle: the dancers held each other’s hands (in the horă) or laid their arms on each other’s shoulders (in the Sîrbă

Footnote

53

). The predominant metre of Romanian dances is binary,Footnote

54

and dances in ternary metres are regarded as being foreign imports. In the nineteenth century, hore in![]() were typical of the towns. All the horă melodies reproduced in Examples 3–7 are in binary metres. Nevertheless, the rhythmic formulas are far from reproducing the variety that existed in regional folk music, and the same goes for the accompaniment. The most obvious specific feature is the modal scales. Given their exoticism, the melodies, which probably originated from the lăutari, posed problems for the composers when it came to harmonization, which was either solved awkwardly or avoided by monochromatic recourse to the Alberti bass.

were typical of the towns. All the horă melodies reproduced in Examples 3–7 are in binary metres. Nevertheless, the rhythmic formulas are far from reproducing the variety that existed in regional folk music, and the same goes for the accompaniment. The most obvious specific feature is the modal scales. Given their exoticism, the melodies, which probably originated from the lăutari, posed problems for the composers when it came to harmonization, which was either solved awkwardly or avoided by monochromatic recourse to the Alberti bass.

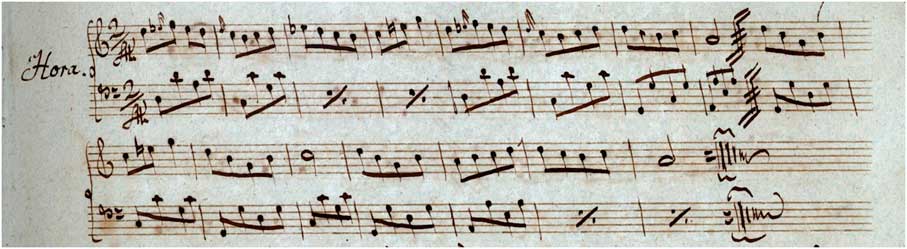

Ex. 3 Hora, from Library of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Musical Collection, MS Rom 2575, 13r

Example 3 is a dance melody that is modal in nature, as is obvious from both the melody and the accompaniment. The scale employed is A minor with a mobile sixth that is altered in a descending pattern (identical with acoustic mode 3Footnote 55 ).

Ex. 4 Wallaque, from the manuscript album preserved in the Library of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Musical Collection MS Rom 2575, 13v

The melody of the Wallachian dance in Example 4 is constructed on the note A. By upper alternation of F (=fis) in bars 5 and 7, there results a scale comprising two minor tetrachords (the Dorian mode). As noted above, binary metre is characteristic of Romanian dances.

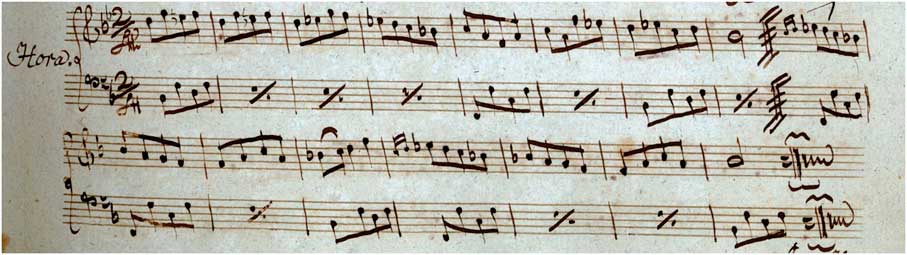

Ex. 5 Hora [1], from the manuscript album preserved in the Library of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Musical Collection MS Rom. 2575, 14r

Example 5 shows a mixture of formulas typical of exercises for pianistic dexterity (reminiscent of Czerny’s études) with modal intonations drawn from the acoustic world of the lăutari. Bars 5 to 8 are constructed on a harmonic pentachord (D–A, with an augmented second between E♭ and F♯) followed by a ‘Phrygian’ minor second (D–C♯).

Likewise, in Example 6 (Hora), the alteration of E (becar, bemol) in bars 1 to 2 results in an augmented fourth (Lydian) in a scale constructed on B♭, the rest of the piece being diatonic, with the same feel of being a piano exercise grafted onto the formulas of a Romanian folk dance.

Ex. 6 Hora [2], from the manuscript album preserved in the Library of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Musical Collection, MS Rom 2575, 14r

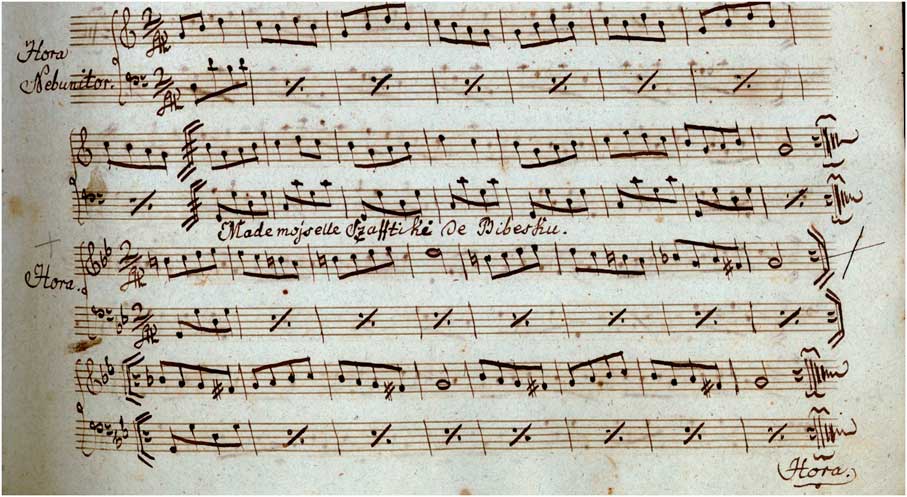

The modesty of the material and simplicity of such didactic pieces for dilettantes, is obvious in the pair of melodies with the titles ‘Hora Nebunilor’ (The Madmen’s Hora) and the horă dedicated to Miss Săftica Bibescu (Ex. 7), an amateur musician from the family of Prince Gheorghe Bibescu, Prince of Wallachia from 1843 to 1848. The ‘Madmen’s Hora’ was performed before and after the horă dedicated to Miss Săftica. The minor harmonic is transformed by upper alteration of the third (mobile) stage into a harmonic major; modal colour is lent by the accompaniment, which seems to imitate a lăutar taraf.

Ex. 7 Hora nebunilor and Hora Săftichii, from the manuscript album preserved in the Library of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Musical Collection MS Rom 2575, 16r

The piece ‘Între Olt și-ntre Olteț’ (‘Between Olt and the Little Olt’, Ex. 8) is based on a quotation from a song that probably had a parlando rubando-type rhythmic development – an apparently free rhythm, frequently found in syllabic (recitative, cantabile or melismatic) melodies. Characteristic of this rhythm is the augmentation and diminution of notes, punctuated values, metrically indivisible units of time, improvised elongations and shortenings,Footnote 56 with durations therefore determined by the nature of the melodic line, and, in the case of vocal pieces, lyrics.

Ex. 8 ‘Între Olt și-ntre Olteț’, from the manuscript album preserved in the Library of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Musical Collection MS Rom 2575, 7v

Piano exercises of this type provide a suggestive illustration of the preferences of amateur musicians from the Bucharest of the 1830s. Besides the samples we have briefly examined, MS Rom 2575 contains more than 60 short arrangements of songs and dances for piano, including pieces whose title points to a Greek original, along with Wallachian pieces, an Albanian song (‘Kintika Arnautcek’, 3r), a Turkish pestref (‘Pestreffe turque’, 3v–6v), and society dances whose titles seem to have been specially chosen to demonstrate the cosmopolitanism of the salons: two krakowiaki, eight ecossaises, three waltzes, a polonaise, a kalamajka, an anglaise, and so forth. With the exception of the ceremonial Turkish pestref, which stretches to seven pages, the pieces are no longer than two or three staves, but despite the simplicity of their form and content, they display remarkable melodic variety. To the diversity of the types of ethnic music with which Wallachian pupils were familiar may also be added the Western elements to be found in manuscript albums such as this one, in the form of not only society dances but also the texts of melodies hand notated in the original French or German, languages spoken by the pupils.

Music at Weddings and Balls, in Clubs and Cafés

The same diversity held sway at public musical events and at the boyars’ large parties. To return to the travellers’ accounts, Frenchman Lagarde recounts among other things a Greek dance performed at a wedding, with dancers ‘whirling on the spot and holding their hands above their heads’.Footnote 57

Recordon describes a betrothal party on the day before a wedding, at the house of a Wallachian boyar. The ceremony includes songs celebrating the bride’s chastity, to the accompaniment of two violins, two ‘Turkish guitars’, a flute and a tambourine. On the wedding day, after the ceremony in church, the celebrations continue day and night until the third day, by which time the wedding guests are exhausted. The ceremony of ‘coiffing the bride’ (the coiffure appropriate to a maiden is undone and then rearranged in the style befitting a married woman) is also performed in front of all the guests.Footnote 58

Englishman Robert Ker Porter travelled from the Danube to Bucharest across Wallachia in 1820. He attended a ball to which the princely family were also invited. The concert consisted of professional violinists, occasionally accompanied by amateur performers. But the guests in general paid little attention to this part of the entertainment; they employed themselves in adjoining rooms, playing cards, smoking pipes and drinking punch. Then, ‘when the ball began, the huge caps of the boyars were thrown off; their splendid pelisses followed the same fate; and each former inhabitant of such panoply of vast magnificence, appeared by the side of his intended partner, in a smart tasty jacket of red, grey, or other colours, fancifully embroidered’.Footnote 59 The dances were Greek and Wallachian. During some of them, the company ‘danced, jumped, whirled and clapped their hands’.Footnote 60 Around a decade later, Perrin mentions that the quadrille and mazurka as preferred at dances and masked balls.Footnote 61

Arriving in Bucharest with high-society recommendations from his diplomat uncle, Stanislas Bellanger spent a few months in the city in 1836.Footnote 62 The traveller recounts his visit to the salon of a Bucharest society lady, where boyars stretched out on divans gravely smoked hookahs, while Albanian servants ‘in glittering costumes’ waited on them. In the corners, young girls chatted together in French, and elegant women kept up with the latest fashions with a copy of Follet open on their knees.Footnote 63 At another soirée Bellanger was surprised during the meal to hear ‘une musique âcre et discordante’ struck up by a Gypsy orchestra in the adjoining room. The hosts were enchanted, but the guest applauded only out of politeness. After a while, the ball began and the quadrille was danced.Footnote 64

Also in the mid-1830s, Anatol Demidov was invited to the country house of Alexandru Ghica,Footnote 65 where he was entertained in the garden by ‘Gypsies who played well for dancing’.Footnote 66 At a ball given by Ban Filipescu, the host ‘still wears the beniș, over which his white beard spreads’,Footnote 67 but at the theatre, where a performance of Rossini’s Semiramidis is given, the prince appears in a frock coat.

Whereas in private homes, dance music might be performed on a piano, at balls and parties such melodies were performed by instrumental ensembles, either a taraf of lăutari or an orchestra of Western instruments. As far as public places of entertainment are concerned, Recordon mentions an aristocrats’ club, granted a privilege by the prince, where cards and billiards were played and unmarried girls danced wearing masks. The club met twice a week during the winter months.Footnote 68 It was also in this period that Laurençon visited a club noble or casino, where the quadrille and other dances were danced.Footnote 69 Robert Walsh was also aware of the Wallachian cabarets frequented by the boyars, where women danced and sang and ‘une extrème dissolution des mœurs’Footnote 70 was to be found. Likewise, Macmichael describes the balls held at a club where German actors performed a poor farce before the boyars, who translated it into Greek for themselves. The men wore Greek costume, while the women wore European modes, with girdles and slippers fashionable in Constantinople. In Bucharest, Demidov was also invited to the ‘nobles’ club’.Footnote 71

In the 1850s, French university professor Ulysse de Marsillac, employed by the Bucharest Military School, recalled performances and concerts at the Salle BosselFootnote 72 and Salle Slătineanu,Footnote 73 the second of which was popular for masked balls. European ‘light’ music became popular thanks to promenade concerts in parks and gardens (for example the highly successful concerts given by Ludwig Anton Wiest in the Cișmigiu and Rașca gardens), balls and festivities. In 1840 the Swiss community in Bucharest laid the foundations of the Union Suisse, which under the name Salle Union would endure in the city’s memory as a much-loved music venue even after the Swiss club ceased to function on the premises, which were hired out in summer for performances and café concerts.Footnote 74

The Urban Periphery

At the same time, the urban periphery remained the preserve of the lăutari. Recordon relates that the Gypsies, who have ‘beaucoup d’adresse et de dispositions … particulièrement pour la musique’ (plentiful skill and inclinations, particularly for music), play melodies and dances on the violin and other instruments which they fashion for themselves.Footnote 75 He sees European cafés and cafés à la manière turque, which persons of a ‘certain rank’ do not frequent, where the silence is broken by Gypsy music and dancing, by jugglers and acrobats, whose contortions and indecent grimaces entertain the clientele.Footnote 76

According to the account of Austrian Ludwig von Stürmer, who passed through Bucharest on his way to Constantinople in 1816, the main entertainment of the boyars was card games and carriage rides along the shore of Lake Herăstrău, among the vineyards and gardens, while ‘the ordinary man enjoys the music played by the Gypsies, who are capable of learning “even the most difficult arias”’.Footnote 77

In Giurgiu in the 1830s, Russian prince Anatol Demidov, who was later to marry Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, witnessed a nocturnal concert of Gypsy music, where a horă was danced.Footnote 78 More than a decade later, Parisian architect Felix Pigéory describes a scene that he witnessed on the road from Giurgiu to Bucharest: a crowd of tattered singers and musicians were performing in an inn and ‘despite the late hour there was a hubbub impossible to describe; Turks, Albanians, Wallachians and Gypsies played the violin, the tambourine and some kind of infernal bagpipes, singing, screaming, cackling things that cannot be named in any language’.Footnote 79

At the Theatre

At the theatre, foreign travellers became acquainted with another facet of the city. In 1818, there was a German theatre company in the city, which gave four performances weekly in an auditorium that usually served as a club and seated 1,000.Footnote 80 Despite the fact that few members of Bucharest society spoke German, they displayed an unexpected interest in the stage. Some of the plays were in demotic Greek, translated from French authors. Laurençon was also impressed by Bucharest’s small theatre,Footnote 81 where he watched a performance by an Italian company in the autumn of 1820, not long before the revolt led by Tudor Vladimirescu swept the city, in 1821.

The almanac of the Wallachian Court for the year 1838Footnote 82 records three theatres in Bucharest financed by Alexandru Ghica, the ruling Prince of Wallachia: a ‘national theatre’ directed by Professor Aristias of the St Sava College,Footnote 83 a German theatre registered as an ‘operatic society’, and a French theatre (‘Société de drames, comédies et vaudevilles’), directed by Ignaz Frisch.

Édouard Antoine Thouvenel, who would serve as the French Foreign Minister from 1860 to 1862, describes an evening at the opera in Bucharest in his account of his visit to the city in 1840.Footnote 84 A month before his arrival, the vaudeville Le Marriage de Raison by Scribe and Varner had been performed in the city, with the lead being played by Paolo Cervatti, a ‘tenor of the Italian opera’. Thouvenel watched a programme of pieces from the Italian opera, including a ‘cavatine del Pirato’, ‘del Furioso’ and ‘grands airs’ from ‘il Themistocle’, probably the opera by Giovanni Pacini first performed in 1823. The theatre building was nothing more than a large wooden structure, albeit well furbished inside.Footnote 85 The audience had gathered ‘au grand complet’: the women, dressed according to the latest fashion, gracefully showed off their glittering jewels, and the men, with very few exceptions, wore Western costume. Thouvenel saw officers in parade uniform covered in braid strutting in front of the ladies and Prince Ghica taking his seat in a theatre box upholstered in red damask. Paolo Cervatti, ‘petit lombard fort replet’, and ‘Mme Wis, Allemande de même encolure’, tackled the most demanding arias of Donizetti and Bellini, earning thunderous applause. In the interludes, the performers’ merits became a topic of argument, and the author notes, ‘presque toutes ces conversations avaient lieu en français’ (almost all these conversations took place in French). Meanwhile, in the stalls, the audience was made up of ‘le plus singulière mélange de Grécs, d’Arméniens et de Bulgares’ (the most singular mixture of Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians).

In the mid-1850s, E.N. Hénocque-Melleville described the theatre as

perfectly laid out inside; the foyer above all, without displaying unnecessary luxury, was decorated in a taste that left nothing to be desired … The sets were masterfully designed. Italian operas enjoy the privilege of being the only ones performed. Mlle Corbary, the prima donna, was judged and appreciated at her full talent by a Wallachian public that takes the love of art to the point of fanaticism.Footnote 86

In unison with other travellers, Hénocque-Melleville comments on the same ‘goûts et usages françaises’ not only in the theatre, but also in ladies’ modes, in the opulent luxury ‘the same as in London and Paris’Footnote 87 and the fashion for carriage rides ‘à la Chaussée’.Footnote 88

Conclusions

To return to the question that opened this article: how did the effects of musical transferrals from the West shape the taste of Bucharest society in the nineteenth century? By the 1830s, not all individual styles held the same significance or enjoyed the same public approval. Greek-Turkish chamber and military music was abandoned soon after the turn of the 1830s; the interest in ‘worldly songs’ would last until the 1860s.Footnote 89 All considered, the coexistence of diverse styles – folk, Levantine, Byzantine ecclesiastical and Western music – among the social elite effected a unique transition to a European way of life.

Sources from the first decades of the nineteenth century, situate the musical habits of the Romanian boyars at the intersection of the Levantine world (a mixture of Greek, Turkish, Wallachian etc.) and the rustic milieu. The boyar wedding described by Recordon shows that some peasant folk traditions with ancient roots were preserved among the aristocracy.Footnote 90 Yet, the Greek dance described by Lagarde in roughly the same period points to the integration of foreign, and in particular Greek, elements at wedding celebrations. At balls, the boyars danced in oriental costume and Gypsy orchestras also played. We may therefore conclude that in contrast to the Western- and Central-European nobility, whose musical canons of taste were strict, Romanian boyars during the ‘old regime’ fostered flexible norms in their handling of music. They were receptive to the Other and permitted relative closeness to multi-ethnic and even ‘lower-class’ music. Consequently, pluralism did not lead to the fragmentation or segmentation of society, but to inter-ethnicity, a situation in which the musicians and audience belonged to different ethnic groups. There was a similar situation in the towns of the late Ottoman Empire, constituting what Rudolf Brandl calls ‘supra-regional urban music’.Footnote 91

Likewise, theatre-going, clubs, card games and private music tuition for children point to the inroads made by the Western lifestyle in Romanian aristocratic circles prior to 1821. ‘High’ society displayed a marked interest in Western culture (see for example Macmichael’s 1818 account of the boyars who translate into Greek the German text of the play performed at their club), albeit one restricted by political bounds. Being chiefly a female occupation, music in the home was the first to be westernized, and western elements co-existed with Greek, Wallachian and other elements in a stylized, aesthetic setting.

Later, in the 1830–50 transition period, audiences of educated city-dwellers seem to have been divided into different groups according to their separate tastes. Faced with a strong influx of foreign (both European and non-European) elements, music lovers were able to sample the various musical styles on offer and select their own favourite repertoire. This freedom of choice seems to have been a gain that came after the 1820s, and would have been hard to imagine in Phanariot Bucharest. Ethnomusicologist Gheorghe Ciobanu links ‘salon music’ to the ‘cosmopolitan tastes’ of the young boyars and ‘worldly songs’ to the ‘popular tastes’ of the lower middle class.Footnote 92 Others (e.g. Ion Ghica and Vasile Alecsandri, who mention that the young boyars had a taste for ‘worldly songs’Footnote 93 ) argue that such categorizations are relative. Consequently, stratification according to the boyar or the middle class is of only partial assistance in distinguishing categories of audience. It is obvious that other factors, such as age, gender, education, inter-cultural experience and ethnic origin influenced musical choices considerably. The elderly, men and the urban periphery still preferred ‘older’ music (such as ‘worldly songs’ or ‘muzică lăutărească’); women, young people, who had been educated in the West, and the immigrant bourgeoisie adopted Western musical tastes. The 1830s to 1850s were therefore characterized by wide musical variety, with the various social sub-groups responding positively or negatively to the different styles on offer.

At odds with what has been presented up to this point is Thouvenel’s account of his evening at the opera in 1840, quoted above: in the boxes, the elevated public spoke French, while in the stalls the audience was made up of merchants of various Balkan and Eastern ethnic groups. In the setting described, categories apparently different in social rank, spoken language and costume make the same musical choice, namely Italian opera. This points to two interesting refinements of the picture.

First, it may be concluded that the boundaries of taste between the boyars (also including the upper-middle class) and the lower-middle class were not watertight, but permeable, perhaps as a result of an education oriented towards similar values. It is known that in this period, while the sons of the boyars travelled to study in Europe, many merchants and tradesmen sent their children to the schools of Bucharest,Footnote 94 which were undergoing reform. French was taught from 1832 at the prestigious St Sava College by Professor Jean Alexandre Vaillant (1804–1886), whose wife ran a school for girls. In 1833, the Philharmonic Society was founded.Footnote 95 At the Philharmonic Society, Ioan Andrei Wachmann ran a free public school teaching vocal and instrumental music. By the end of its first year (1835–36), the school had succeeded in giving the first operatic performance in Romanian (Rossini’s Semiramidis).

Second, Thouvenel’s account points to an interesting phenomenon of inversion of the conventions pertaining to costume.Footnote 96 Only the ethnic origin of the townsfolk, the small traders and petty bourgeois, could still be determined by their costume. Nevertheless, some were beginning to adopt European costume (‘the garb of equality’), which erased outward differences between the classes and different ethnic groups. Clothes did not make the man, but they could conceal him.Footnote 97 Motley ethnic costume pointed to a more modest social standing, while the European costume and impeccable French accents of the audience in the theatre boxes concealed from the traveller their real origins: they belonged to the upper classes, but as we have demonstrated, their roots were partly multi-ethnic. The criterion of difference was in fact money: not ethnic background, but the ticket price made the difference between a box and the stalls.

The performance of European music and dances at balls and celebrations signalled greater openness to the West in the 1840s. In this context, it was an ideological factor that contributed to the homogenization of musical consumption. In the first decades of the century, the (predominantly non-Romanian) middle class did not have any sentiment of belonging to a ‘class’ and was not involved in politics. The middle class did not therefore form a ‘national’ bourgeoisie.Footnote 98 The consciousness of belonging to a particular social category and to a nation was to be shaped in the decades that followed, and after two or three generations some of the descendants of families that had immigrated before 1821 regarded themselves as assimilated within the Romanian nation.Footnote 99 People of culture, including musicians (regardless of ethnic origin), supported the national ideal, and in the multi-cultural city the central concern of the intelligentsia was to confer a sentiment of individual identity upon the nation.

The European model that was regarded as the gateway to ‘civilization’ was Latin in general and French in particular.Footnote 100 French cultural influence was adopted by the upper class and bourgeoisie as a ‘second identity’. And the nation’s centre of gravity, given the ethnic mixture of the cities, was to be identified with the villages, where 81.2 per cent of Romania’s population lived around the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 101

The boyars’ tastes therefore ceased to be ‘flexible’. In terms of Bourdieu’s theory of social distinction, Western music and knowledge of European languages (particularly French) became a symbol of education and wealth, and thus an indicator of social status. From the moment Romanians adopted the European value system, their musical preferences began to be regulated by the aesthetic norms proper to Western culture. In particular, the music provided by uneducated (mostly Gypsy) minstrels was no longer acceptable except conditionally. In the 1850s, Vasile Alecsandri wrote with a certain detachment about the boyars’ custom of entertaining guests with folk musicians: ‘although it seems to us rather indecent, such was the custom of old and we must needs respect it’.Footnote 102 Lăutar melodies were now stylized in piano collections for a salon public,Footnote 103 thus confirming their popularity. In parallel, a segment of the intellectual class engaged in abolitionist politics, which would lead to the emancipation of the Gypsy slaves between 1843 and 1855.

At this stage, the audience for musical theatre underwent a further stratification, choosing its preferences from within the European repertoire. Simplistically, it might be said that the taste of more sophisticated urban audiences tended towards Italian opera, while ordinary people found entertainment in operetta and Romanian-language theatre. However, there have been no wide-ranging, systematic studies on this subject.Footnote 104

Musical preferences changed concomitantly with changes in the structure of the Bucharest bourgeoisie as a whole, which after 1864 underwent a renewal. Boyar privileges (for example, exemption from taxes) were abolished, and urban society was restructured according to bourgeois criteria (property and education) and along the lines of new social categories: large landowners, politicians, university-educated professionals (lawyers, physicians, teachers, pharmacists, etc.), and functionaries.Footnote 105 Immigrants (according to census of 1878, the majority were Austrian subjects, including Romanians, Saxons, Hungarians and Jews from Transylvania, as well as other regions of the Habsburg Empire) were to contribute to the development of Romanian musical life. Italian, French, German and Hungarian theatre companies toured Romanian theatres.Footnote 106 Naturalized foreign musicians and entrepreneurs (publishers, printers, merchants, musical impresarios) were active in Bucharest, some of them over the course of many generations. The repertoire was European, and Italian composers were at times dominant, for example Rossini in the 1820s and Verdi in the 1850s. The dates of premieres reveal how Bucharest was synchronized with the pulse of the times: Bellini’s Montecchi and Capuletti (Venice 1830, Bucharest 1834); Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable (Paris 1831, Bucharest 1835); Verdi’s Rigoletto (Venice 1851, Bucharest 1854), and so on.Footnote 107

The most significant drivers of this change had of course been institutions: the conservatoire, concert societies and musical theatre. They drew not only the attention of professional musicians interested in the opportunities offered by an emerging musical market, but also the energies of intellectuals and boyars’ sons passionate about music, one example being George Stephănescu, who was to sell his ancestral estate to finance from his own pocket the Romanian-language opera company he founded in 1885.

What became of the old, multi-ethnic repertoire, previously exemplified by worldly songs and fiddler music? This repertoire continued to exist; it addressed an audience that was increasingly on the ‘periphery’, but it was to inspire musical works belonging to both ‘high culture’ and ‘popular culture’. On the one hand, what had been acceptable within the circles of the urban centre was relegated to the margins of the city, a path followed by the Turkish term mahalle (Romanian mahala, pl. mahalale) itself: before 1830, the word had denoted a central or marginal urban district, but it later came to mean solely the urban periphery, with connotations of coarseness and vulgarity, in contrast to the cosmopolitanism and modernization represented by the centre.Footnote 108 While manners imported from the French-speaking West lent a note of internationalism to the lifestyle of wealthy city-dwellers, their distance from ethnically mixed peripheral world became increasingly pronounced. Quasi-popular Greek, Turkish, Albanian, and Gypsy influences became coarser and were viewed pejoratively and as out of date. In other words, they became typical expressions of ‘Balkanism’,Footnote 109 associated not only with a low level of education, but also with negative moral traits, such as triviality, violence, promiscuity and vulgarity. Remnants of the Constantinopolitan heritage survived modestly in the precarious world of the mahalale, which perpetuated the memory of a musicality excluded from higher cultural registers (at least in its raw form, unpolished by the tools of professional artistry).

On the other hand, the old non-Western musical heritage underwent a metamorphosis, a re-evaluation within the field of ‘high culture’. The attention paid to the exotic by composers such as Liszt and later Bizet and Brahms placed South-East European ‘popular music’ within the context of ‘art music’, allowing the elites ‘elevated’ access to a musics now shunned in their ‘raw’ form. By the end of the nineteenth century, when the public had become a concert-going audience, lăutar music gained a new acceptance within the framework of musical orientalism. From this viewpoint, modernization brought not a levelling or uniformity, but rather a re-conceptualization of the traditional within a professionalized artistic language that the Romanian public was gradually to discover and assimilate.

Some nineteenth-century Romanian artists would seek ways to integrate the ethnic dimension in literature, painting and music using means similar to those of Romanticism. For example, chromatic modes occur as a separate pigment of ‘fairy enchantment’ in operettas, among which Old Woman Hîrca by Alexandru Flechtenmacher (which premiered at the Momolo Theatre in 1850) also thematized the exploitation of Gypsies. The topic of the lăutari, accompanied by quotations from minstrels’ songs, appears in the stage ‘canzonetta’ Barbu Lăutaru (Barbu the Lăutar) by Flechtenmacher, a setting of a play by Vasile Alecsandri. Fiddlers supplied stage music with countless dance melodies, songs of yearning or mourning, brisk finales and atmospheric musical interludes. Yet as early as the 1830s, it is possible to detect satirical, parodic notes directed both at ‘orientalism’ and ‘Frenchifying’ (the ‘can-can’ is employed with a satirical meaning in vaudevillesFootnote 110 ).

‘In a country where music was confused with lăutăria [the trade of the folk musician, or lăutar], a young man required true fanaticism to dedicate his life to a thorny musical career’, wrote Mihail Jora in 1937,Footnote 111 looking back on the founding of the George Enescu Composition Prize (1913) as a significant step towards stimulating inter-war Romanian music creation. Only one century had passed since travellers described the incipient interest of the boyar class in Western music. Viewed from the interior the change seemed too slow, and many wondered whether a reform had really taken place – or merely a simulacrum of reform: Romanians may have changed their costume, but not their ‘bad habits’; they were attracted more by the glitter of the West than by bourgeois morals or, as Junimist Footnote 112 criticism would have it, more by the forms than the content. They colluded in the ‘equivocal’ and ‘intermediate’, in a sine die state of transition. In the dialectic of history, with its crises and regresses, Romanians were ‘condemned’ to stagnate between epochs and civilizations, without really belonging to any of them.

Nevertheless, musical preferences show that the mentality had changed: the educated public of the late nineteenth century viewed pre-1821 musical habits through a lens similar to the travellers of former times. At weddings and celebrations, ‘oriental’ or ‘Balkan’ influences seemed like splashes of exotic colour, bizarreries or archaisms, and perhaps also reminiscences of an ever more remote and consequently increasingly idealized past. Audiences had different reference points, preferences and expectations. In spite of the differences between the centre and the periphery, between village and town, the nineteenth century had proven to be one of accumulations and assimilations. The presence of foreigners in the life of the capital attested in fact to its prosperity and vitality. The newly founded institutions, an education system modelled on that of the West and freedom of movement and communication, had left a lasting mark, bringing, despite misgivings, a change not only in the form but also in the content of Romanian society.