Introduction

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, musical practices at the princely and boyar courts of the Danube Principalities of Wallachia (or the Romanian Land) and Moldavia presented a heterogeneous picture, and the ritual of ceremonial Byzantine chant and the taraf of the prince’s musicians coexisted very successfully with Turkish military bands (mehterhâne and tabl-khāne) and European-style orchestras (‘German’ or ‘European music’).Footnote 1 This acoustic mélange within a multi-ethnic atmosphere was nothing more than a consequence of the fact that Romanian society itself, still under Phanariot rule at the time, was amalgamated and motley in its cultural manifestations, a society that brought together nations, languages, intellectual backgrounds, aspirations and ways of doing things that were, more often than not, highly distinct.

The signing of the peace treaties of Küçük-Kaynarca (1774) and, in particular, Adrianopolis or Edirne (1829) between the Ottoman and the Russian Empires – documents that set their seal upon a considerable reduction in the power of the Ottoman Porte over the Romanian Lands, while increasing the power of the Tsar in the same region, facilitated ever closer contacts with Russia and Western Europe, causing almost every aspect of Romanian political, social and cultural life to be influenced and transformed. And so, within half a century, the Romanian elites changed their mentality and lifestyle so profoundly that between a boyar of the period 1810–20, for example, and an aristocrat of 1870 only few similarities remained. The first wore ișlic and a caftan, the second a top hat and frock coat; besides Romanian, the boyar spoke Greek and maybe Turkish, whereas the aristocrat spoke French, Italian and even a little English and German. Oriental manners were replaced by the code of elegant manners current in the upper echelons of European society, and education was received not only at the princely academies of Iaşi and Bucharest, but also the most prestigious universities of Western Europe.Footnote 2

When it comes to music, these changes in mentality and behaviour meant the presence, whether temporary or permanent, of foreign musicians at the princely and boyar courts of Wallachia and Moldavia, particularly after the year of the Balkan revolution (1821). The great majority having arrived from the Habsburg Empire,Footnote 3 these musicians either played in orchestras and itinerant theatre and opera companies, or were solo vocalists and instrumentalists, or taught the piano, an instrument that enjoyed a great vogue among the bourgeoisie and the scions of the local elites.Footnote 4

In parallel with this infusion of Western European sound, the Ottoman military bands, as an official palace ensemble, continued to serve a ceremonial role for the Romanian princesFootnote 5 until they were abolished, probably in 1830, when the modern army was established.Footnote 6

The Establishment of the First European-Style Military Bands in the Romanian Principalities

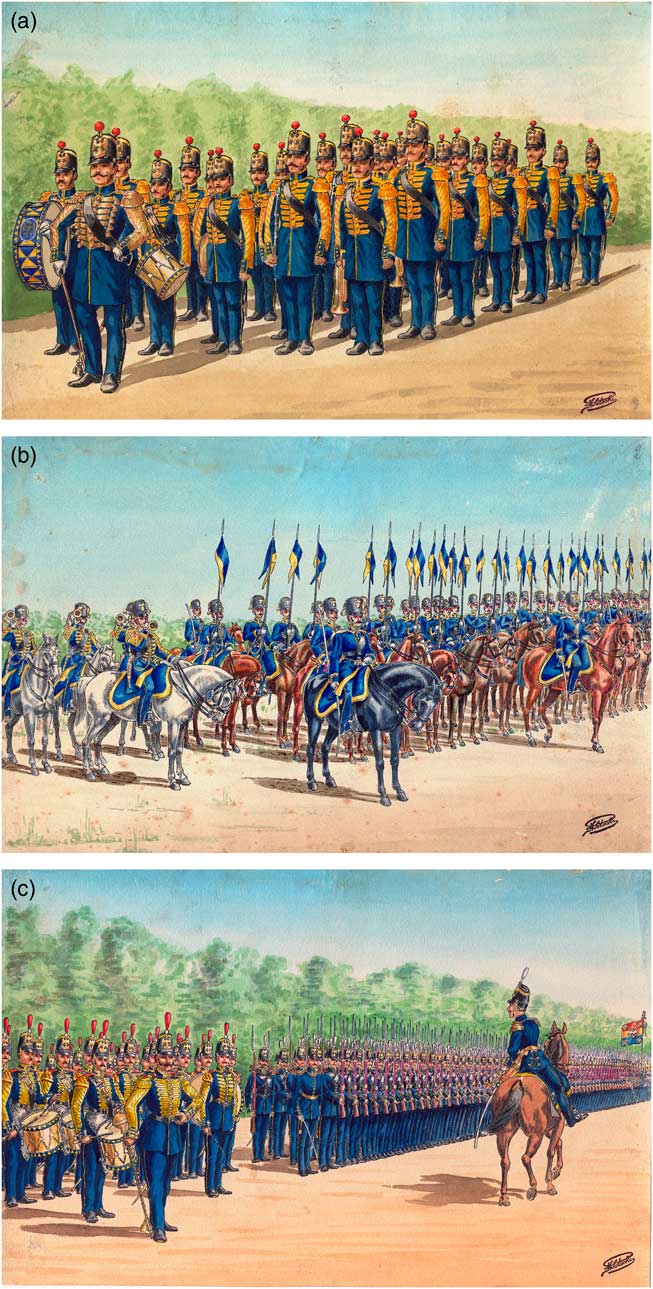

Among other things, the Peace of Adrianopolis (1829) allowed the Danubian Principalities to re-establish their own armies, and so it was that one year later, in April 1830, the Divans of the two capitals, Bucharest and Iaşi, each passed a law setting up a standing army, which contemporaries called Straja pămîntească (The Land Guard). Modelled on the organizational structure of the armies of the western powers, the Straja pămîntească stipulated, among other things, the existence of a medical corps and a brass band-type instrumental ensemble (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 From Albumul Oștirii, Bucharest, 1852: (a) Ștabul Oștirii Musical Band (The Band of the General Staff) in 1831 (b) The Cavalry Squadron of the Second Infantry Regiment in 1831 (c) The Land Guard (Straja Pămîntească) full-dress uniforms. The First Infantry Regiment (1847).

It should be noted that in the newly formed army the transition from oriental to Western-European military uniforms and insignia came about abruptly and with immediate effect. Albina românească (The Romanian Bee), one of the leading political and literary gazettes published in Iaşi, and the first Romanian-language newspaper in Moldavia, vividly reports this change:

On Sunday, 14 September 1830, Mr Constantin Paladi the Hetman, General Inspector and Chief of the Land Army, having shaved his beard and divested himself of his Asiatic [Ottoman] costume, donned the national uniform, the same as all the officers and soldiers under his command, and now wears a cockade and the national flag, in the colours of blue and dark red.Footnote 7

Chronologically, the first band of this type was formed in Iaşi, the capital of Moldavia, on the basis of an act (poruncă, or order) that came into effect on 25 August 1830.Footnote 8 The act tasked the Czech Franz Ruzitski (1795–1860?),Footnote 9 a pianist, cellist and author of a collection of melodies for piano which he described as ‘oriental’,Footnote 10 to purchase from Vienna instruments, musical scores, practice methods, and instrumental studies. The funds for this were substantial (more than 12,150 lei)Footnote 11 and consisted of private donations from the ecclesiastical, political and intellectual elites of the time,Footnote 12 who were convinced that their gesture would play a vital role both in reviving the old military virtues and in educating the nation.Footnote 13 Franz Ruzitski thereby became the first Kapellmeister of the Moldavian military bands. In the beginning, his band was made up entirely of German-speaking musicians.Footnote 14 Four of these (Laitner, Vazel, Briza and Dub) were later additionally assigned to instructing the soldiers who were to become members of the band.

The initiative of founding the first military band with modern instruments was hailed and praised in both Bucharest and Iaşi, which demonstrates the important role and credibility that this musical organization enjoyed in the society of the time, which was itself in the midst of a far-reaching process of emancipation. The first military band of the Straja Pămîntească had 38 Western instruments: 12 clarinets of various keys, two oboes, three bassoons, one contrabassoon, four flutes of various keys, three waldhorns, one keyed bugle, eight simple (cavalry) trumpets, one drum, one pair of cymbals, one corno di postiglione and one bass trombone.Footnote 15 Ruzitski’s conductorship of the Iaşi band was short-lived, however. It is known that in March 1831 he was replaced by Joseph Herfner-Esterházy (1795–1865),Footnote 16 apparently a scion of the Esterházy noble family, a musician highly active in the capital of Moldavia (Fig. 2).Footnote 17

Fig. 2 Josef Herfner-Esterházy

Unpublished documents from the State Archives in Iaşi seem to indicate that the commander of the Straja Pămîntească had an intense lack of faith in Ruzitski’s ability to administer the funds intended for the military bands. The list of instrument prices, for example, reveals a significant difference between Ruzitski’s financial evaluation and that of the battalion and squadron commander, Polkovnik (from the Russian полковник/colonel) A. Bodgan. Moreover, six of the instruments purchased by the Austrian Kapellmeister were ‘rotten’, ‘old and worthless’.Footnote 18

In spite of these drawbacks, the Iaşi military band, conducted by Kapellmeister Josef Herfner, made its first public appearance on 23 August 1831, on the occasion of the consecration of the arms of Moldavia and the taking of the military oath, when a large military parade was held, at which the marches of the Straja were played and also sung. The event stirred considerable interest in the pressFootnote 19 and Kapellmeister Herfner was promoted to the rank of sub-lieutenant (praporgic: sub-lieutenant in the Russian Army), thereby becoming the first army music officer in the Romanian Principalities.

In Wallachia, the first military band appeared in the same year, 1830, but in a different context than in Moldavia. The band was linked to the name of Grigore Alexandru Ghica the High Spatharius (c. 1807–1857), who later became Prince of Moldavia (r. 1849–53 and 1854–56). The moment was connected to a plague epidemic which so greatly frightened the inhabitants of Craiova, located in the south of what is now Romania, that they decided to fetch the relics of St Gregory the Decapolite from Bistrița Monastery in order to save the city. Relevant in this respect is the late-nineteenth-century account of musicologist Teodor T. Burada:

In order to welcome the holy relics with all the fitting pomp, they decided that all the soldiers quartered in the city should go ahead to the edge of the city to greet them; but the army lacked embellishment for such a thing, which is to say a band; therefore Alecu Ghika the High Spatharius ordered that one be founded, hiring for a wage a number of musicians from the private band of Constantin Golescu the High Dvornik. Clothing them in military uniforms, he made them into a band of musicians, adding guitars and flutes taken from the guild of barbers, and making a Hungarian musician called Doboș the Kapellmeister and one of Golescu’s Gypsies, Dinică, Under-Kapellmeister, who was also the first clarinettist.Footnote 20

The first Wallachian band was called Banda Ștabului Oștirii (The Band of the General Staff) and was to form the nucleus of the later military music of the city of Craiova, being funded not by the state, but, the same as in Iaşi, using public subscriptions from officers, who donated two parale (para, pl. parale, 100th part of 1 leu) from their wages. This so-called ‘honorarium’ was named the ‘music para’ and formed the basis of the military bands’ wages until 1858, when the army command took over their maintenance and funding, also establishing new bands.Footnote 21

In Bucharest, the military bands emerged in their institutional form in 1832, following the establishment of an infantry regiment under the command of Polkovnik (Colonel) Constantin Filipescu. As a result of the public subscription organized by Filipescu, but mainly at his own expense, Wallachia’s second military band came into being.Footnote 22 It was similar to the one in Iaşi and was conducted by Carol Engel.Footnote 23

In the spring of 1831, a few months after the establishment in Moldavia and Wallachia of the first three infantry and cavalry regiments, the first military regulations were published and put into effect. In order to gain an understanding of the evolution of the military bands, it is important to note that in the acts that organized and established military forces, ‘musician soldiers’ were also stipulated (48 in the infantry regiments and 12 in the cavalry regiment), which shows that the military authorities were beginning to pay appropriate attention to this category of soldier. It seems that the establishment of military bands in Iaşi, Craiova and Bucharest stimulated other such initiatives, and in the years that followed bands could also be found in other towns of the two historical Romanian provinces: Roman (1847), Piatra-Neamț (1847), Galați (1850), Ismail (1859), Ploiești, Brăila and elsewhere.

Music and Kapellmeisters in the Danubian Principalities

Trends in Repertoire

As was the case of salon music in the other Balkan states in the nineteenth century,Footnote 24 the repertoire of the Principalities’ military bands was striking both for its lack of any determining stylistic unity and for the broad spectrum of its provenance, on the one hand, and the diversity of the audiences at which it was aimed, on the other – audiences whose musical and cultural horizons were extremely varied. The archival documents reveal that, in addition to musical instruments, Franz Ruzitski also brought a repertoire from Vienna in 1830: for the most part miniature pieces – waltzes, marches, cavatinas, Polonaises, mazurkas, rondos and potpourris – which were highly fashionable in the salons of the time, but also works inspired by Ottoman music, which shows that the taste for oriental music was still alive among audiences. Similarly, in addition to various method books for clarinet, flute, bassoon and oboe, the Viennese musician purchased arias from different operas, and also longer works, such as the overtures to Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito, Rossini’s La Cenerentola and Tancredi and Beethoven’s Fidelio. To these were added works by local composers, such as the marches of Răzniceanu and D. Cuna.Footnote 25 Cuna was the first violinist of a French orchestra conducted by Kapellmeister Herfner himself between 1832 and 1833,Footnote 26 and later becoming a professor at the Philharmonic and Dramatic Conservatory in Iaşi, founded in 1836 by Gheorghe Asachi (1788–1869).Footnote 27

It seems that besides Vienna, St Petersburg was another cultural centre from which musical scores and instruments were provided. On 28 September 1835, hetman and knight Teodor Balș placed at the disposal of Josef Herfner, the conductor of the military band in Iaşi (which numbered 26 instrumentalists), the following new Western musical scores purchased in St Petersburg: four overtures, seven French quadrilles, seven marches (including one from Warsaw and one from Turkey), six waltzes, six mazurkas, and nine other pieces for buglers and drummers … ‘in total 39 pieces that I shall teach the militia musicians … Josef Herfner. Maitre de Chapelle’.Footnote 28

Thereafter, the purchase of instruments from abroad remained a constant. More often than not, they were bought in the capital of the Hapsburg Empire, as was the case in 1838Footnote 29 and in October 1854, when Herfner purchased 39 new instruments from Viennese manufacturer Ignatz Stowasser. On that occasion, the Viennese Kapellmeister was promoted to the rank of captain (chief of music, first class).Footnote 30

With each passing year, the military bands came to hold an increasingly important place in both the everyday life of the barracks and civilian society. In addition to taking part in military and civil honours and ceremonies, the bands gave cycles of concerts in public parks and gardens, providing not only free entertainment, but also an efficient means of musical education for the masses. Up until at least 1880, the Romanian Principalities benefitted from a generation of ‘imported’ Kapellmeisters and instrumentalists, who either were hired for limited periods or settled permanently, becoming citizens and attempting to identify with the aspirations and ideals of their adopted homeland.Footnote 31 The wind ensembles were to become ‘laboratories’ for the training of military musicians, many of whom frequently joined ad hoc symphonic orchestras or itinerant opera and theatre troupes. Numerous princely decrees published in the press of the time officially acknowledged the artistic merits of the military instrumentalists and Kapellmeisters, granting them pecuniary rewards, medals, or advancements in rank. For example, by the porunca of Barbu Știrbei, Prince of Wallachia, published in Buletinul Oficial in Bucharest in 1850, Costache Antoniu, ‘under-officer of the Ștabul Oștirii musical band’, and Niță Stan Drăgoiu, ‘staroste [conductor] of the musicians of polk [troop] 3’, were cited for a medal, being granted the right to wear a ‘braid temleac [cord] on their sword’ and ‘a wage the third part of a praporgic’.Footnote 32

As can be observed, the conductors and instrumentalists of the military bands were veritable shapers and promoters of musical opinion and culture, regardless of origin. This led many of them, familiar with the public taste, to not limit themselves to arrangements and orchestrations for celebrated pieces from the West, but to draw upon native folk music, creating numerous fantasias, suites, overtures, potpourris and rhapsodies. Prince Anatole Demidov (1813–1870), the leader of a Franco-Russian scientific expedition to meridional Russia, published a Marche valache encountered during his sojourn in Iaşi and Bucharest in 1837 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 ‘Marche valache’, in Anatole Demidov, Voyage dans la Russie Méridionale et la Crimée par la Hongrie, la Valachie et la Moldavie (1837), 12th edition (Paris: Bourdin, 1854).

Consisting of two couplets and a developed trio, the march was based on a native folk form: Hora Roumaniaska. The example is all the more noteworthy given that the well-known French draughtsman, engraver and painter Denis Auguste Marie Raffet (1804–1860), who accompanied Demidov to the two Romanian capitals, immortalized the scene of the hora (ring dance) held in Bucharest on 16 July 1837 in a remarkable period engraving (Fig. 4), as well as providing us with an important explication:

At the start, the soldiers are those that accompany the first figures; but in their turn they have become dancers and perform la roumanieska, the dance that is the most characteristic and performed all over the country. In this large circle which revolves now to the right, now to the left, each person has the right to enter and take his place, just as each may leave as he wills. The aria that accompanies this dance is an interminable melody … in which the Gypsies try to outdo each other.Footnote 33

Fig. 4 Ronde Valaque.

Another example of the valorization of the Romanian folk sound is the Uvertura Națională (National Overture) by Kapellmeister Josef Herfner, a piece that was conducted by its composer in 1845 in a performance by a veritable symphony orchestra made up of the Iaşi military band and a group of string instrumentalists.Footnote 34 The following is an account from a daily newspaper describing the first performance of the composition, which took place on the name day of the Prince of Moldavia, Mihail Sturdza (r. 1834–1849):

The evening of 8 November of the current year was a day that testified to the most authentic sentiments of the Moldavians. The theatre was the predestined place where the inhabitants of the capital, of every rank, were publicly to congratulate their illustrious Prince on the eve of his name day. On His Lordship’s entrance into the auditorium, the orchestra struck up harmonious chords, after which a choir of twenty Moldavians, actors and actresses, began to sing the national anthem. The silence and the concentration were so complete that both the chords and the words were very well heard, understood and felt by the listeners, who in this anthem cherished a public wish for the happiness of their Prince and cherished homeland. All the music was new, to a Moldo-Romanian melody, composed by Mr Herfner, the Kapellmeister of the military band and the theatre, with whose good taste our public has been familiar for many years. … Then began a National Overture, in which the Moldavian easily recognises the verse of his childhood songs, the melancholy tone of the doina [melancholy Romanian folk song–author’s note] with which the people of the plains and the mountains gladden the days of their lives. At the public’s request, the Overture was repeated, thereby finding a pleasing echo in the hearts of the Moldavians, in which the passion and national feeling made themselves known.Footnote 35

It seems that the work was the first attempt to introduce folkloric intonations into a larger orchestral genre.

The Military Bands within the Framework of Armed Conflicts in Nineteenth-Century Romanian Lands

The 1848 Revolution

After 1840, the Romanian press regularly reported the military bands’ promotion and cultivation of nationalistic musical genres, in which marches, patriotic songs and, above all, ‘national anthems’ held a central place. Almost every festive entertainment, national holiday or, as we have seen, ruler’s name day featured a military band and this type of repertoire.

At the same time, nineteenth-century Romanian social and political movements wagered heavily on the mobilising effect of the army’s wind orchestras. The Romanian Revolution of 1848, for example, which was part of the Europe-wide upheavals of the same year, fully marks the military bands’ solidarity with and presence among the masses. Deșteaptă-te, române! (Romanians Awake!), now the Romanian national anthem, was in this period a symbol of the 1848 Revolution; it came to be not only the Romanian Marseillaise,Footnote 36 but also an anthem for the Balkans, given its numerous translations and performances throughout the Hapsburg Empire and even in the heart of Republican France.Footnote 37

But the instrumentalists of the military bands and the members of the Ștabul Oștirii Band were not always appreciated for their art, especially if the music they promoted detracted from the image of the rulers of the time. They were sometimes even punished harshly for their involvement in the social movements of the day, as in the case of brothers Beli and Plaino, who were tried by the reactionary regime for having ‘walked up and down the deck (Victory Avenue – author’s note)Footnote 38 with the military band all night and played the Marseillaise on the streets’.Footnote 39 The depositions of some of those investigated illustrate the fact that the military bands’ participation in the revolutionary event was sometimes a response to orders issued by its instigators, but was also often a spontaneous manifestation. As an example we can cite the declaration of Costache Steriadi, who, in connection with the burning of the Organic Regulations and Archondology (the book of boyar ranks) in the autumn of 1848, related the following:

In the burning of the Regulations, there was no official or even private connivance in the Department. The revolutionaries’ plans were not known to the chancellery workers. But all of a sudden, on the morning of 6 September, having assembled in the chancellery, we found ourselves confronted with a great and a crowd of people in the Administrative Court, preceded by the military band and shouting: Down with all the employees! Footnote 40

But the Revolution also provided a spur to the energies of native military composers, and thus we find a march dedicated to the new provisory Government, a work suggestively entitled În numele guvernului (In the Name of the Government), composed by unter-ofițer (sub-officer) Pascu Purcărea. Having joined the Army as a bugler in 1835, Purcărea became an instrumentalist sub-officer in the band of Regiment no. 2, conducted by Johann Engel, and in 1846 he became conductor of the buglers of the Ștabul Oștirii Band.Footnote 41 His qualities as a composer were acknowledged even by Barbu Știrbei, the Prince of Wallachia, in whose moving chancellery document can be detected not only the noble ruler’s esteem for the talented sub-officer, but also his encouragement of young composers:

We, Barbu Știrbei, by the mercy of God ruling lord of all the Romanian Land. Commandment to the Romanian Army.

We receive with satisfaction the march composed by the unter-ofițer of the Ștabul Oștirii Band, Pascu Purcărea, which was performed for us, and we, in order to encourage and urge others to earn Our reward through exemplary industriousness in their duties, give him the right to wear the braid cord together with the third part of the wages of a praporgic and at the same time it is particularly recommended that Kapellmeister Vist (Ludwig Anton Wiest – author’s note)Footnote 42 shall foster his talent, bringing it to perfection, reporting his progress to us every three months. Signed Barbu Știrbei, no. 120, anno 1850, June 24.Footnote 43

Unitary as a whole and Romanian in content (the work draws upon folkloric themes), the În numele guvernului march makes Purcărea one of the first local military musicians to have been interested in this genre,Footnote 44 having composed and orchestrated the oldest Romanian musical score for a military band currently known to exist (Fig. 5).Footnote 45

Fig. 5 Pascu Purcărea, În numele guvernului, arranged by Constantin Costoiu (Bucharest: Military Editing House, 1980).

The Union of the Romanian Principalities (1859)

During the process of the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia, in 1859, when the presence of Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza was saluted either with Alexandru Flechtenmacher’s folk Ring Dance of Union by or other occasional marches, it became necessary to create an official national anthem to represent both states. It seems that another contributing factor was that a number of foreign anthems had begun to circulate, while the Ministry of War published an edict banning military bands from playing ‘foreign anthems’ at ‘reviews and other occasions’.Footnote 46 This is not at all surprising, given that almost all the military bands were conducted by foreign Kapellmeisters. Beginning in 1859, on the annual national holiday to celebrate the Union of the Principalities (24 January), composers, poets, music teachers and actors from the national theatres marked the event by writing festive anthems, school anthems, national anthems, Romanian anthems and other similar works. In order to choose an official anthem, in 1861 the Ministry of War held a national competition, ‘in consideration of the need for the military bands to have a national anthem to play on high occasions’. The prize was 100 gold pieces. Of the 13 entries in this difficult contest First Prize was awarded to Eduard Hübsch (1833–1894), former concertmaster of the Hamburg Opera, then conductor of the National Theatre in Bucharest and the first inspector of army bands (from 1867 to 1894) (Fig. 6). Second Prize went to Iosif Ivanovici (Fig. 7), composer of the famous Danube Waves waltz and Kapellmeister of the Fifth Line Regiment. And the Third Prize was taken by Pascu Purcărea. The results were announced in the Order of the Day for the Whole Army no. 20 of 22 January 1862, which informs us that the six-member juryFootnote 47 responsible for examining the 13 competition entries placed Purcărea’s March to Greet Every Rightful Leader in third place, behind Hübsch’s Triumphal March to Greet the Flag and His Excellency the Prince, in first place, and Ivanovici’s Daybreak with the Prayer, in second place.Footnote 48 Thus, Hübsch’s Triumphal March, opus 68, became not only the army’s official anthem from 1862, but also the National Anthem until the full Soviet takeover of Romania on 30 December 1947, the date when the history of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen monarchy came to an end (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6 Eduard Hübsch

Fig. 7 Iosif Ivanovici

Fig. 8 Imnul Național (The National Anthem) by Eduard Hübsch

Although few in number in this period and confined to the largest cities, the military bands introduced the new sound of Western European music, doing away with the last traces of oriental tradition, offering a rich repertoire, one that was unfamiliar to the lăutari (Gypsy musicians), and above all impassioning, with their ring dances and marches performed in public squares, parks and theatres, the masses desirous of unification of all Romanians under the same ruler.Footnote 49 It may be deduced that many of these works were dedicated to Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza, for example The Ring Dance of Kuza Vodă by Dimitrie Florescu (1827–1875), composed on the occasion of the entry into Bucharest of His Excellency Prince Aleksandru Joan I and the Cousa Marche by Elena Botianu.

The War of Independence (1877)

In the war to gain national independence from the Ottoman Empire (1877–78), fighting alongside the Russian Empire, the Romanian troops at the front had military bands and buglers, which meant that the musicians and Kapellmeisters came into close contact with the battlefield. Their presence on the front line contributed to bolstering the troops’ morale, as is apparent from the following account by the war correspondent for Allgemeine Zeitung, written before the attack at Plevna:

[W]ith their national anthems the regimental bands draw the off-duty soldiers … to a lively dance and it is an enchanting sight to see entire battalions do the ring dance by the light of the moon, and sometimes even the officers join in, which makes the soldiers even merrier. Often the hour will have passed midnight, but on the green sward there will be whirling hundreds of dancers. I think that if the music were left to their will, they would dance until dawn.Footnote 50

The gaining of national independence created a wave of compositions whose themes were inspired by the bravery and heroism of Romanian soldiers. As musicologist Elena Zottoviceanu observes, these compositions are ‘a kind of musical war diary’,Footnote 51 their titles in effect evoking all the phases and themes of the War of Independence. For example, it is from this period that the Crossing of the Danube march by Johann Jalowitski (c. 1825–1888) dates. Jalowitski was the conductor of the Fifth Line Regiment from Galați, and the piece was commissioned for the imperial military bands of Tsar Alexander II by the Kapellmeister of Grand Duke Nicholas, the commander of the Russian Army in the war against the Ottoman Empire, when he was in the city of Pitești. It was also Jalowitski who composed the Taking of Plevna march, which was performed for the first time at the war headquarters of Prince Carol I in Poradim.Footnote 52 We can add also the marches The Entry into Vidin and The Attack at Grivița by Iosif Vollmar, the conductor of the Genius Battalion band, The Taking of Plevna by Anton Kratochvil, senior (1829–1920), The Attack at Rahova by Eduard Neudörfer (1851–c. 1915), and The Danube Watch, op. 209 (1878), Les Fanfares, Smîrdan and Our Brave Men (1884) by Eduard Hübsch, who had become general inspector of military bands in 1867.

It was also in this period that the foundations of a repertoire of military marches were laid. These often had folkloric influences and can be collectively named the ‘hore (ring dances) of Independence’. Of these the following are of note: The Grivița Ring Dance and The Plevna Ring Dance by Gavriil Musicescu, The Ring Dance of the Little Foot Soldiers by Iosif Ivanovici, The Grivița Ring Dance and The Ring Dance of the Foot Soldiers by Theodor Georgescu (1824–1880), The Ring Dance of the Turkeys by Nicolae Ștefu (1855–1914), The Ring Dance of the Carpathians by Anton Kratochvil, senior, The Ring Dance of the Soldiers by Ludwig Anton Wiest and The Ring Dance of the Grivița Foot Soldiers by Eduard Neudörfler.

In the history of nineteenth-century military bands in the Romanian Principalities, the year 1877 marked the maturing and crystallization of the choral and/or instrumental soldier’s song, which is sometimes grouped according to branches of the military (infantry, cavalry, artillery, alpine troops). There was a shift from the Gypsy or peasant national horă, mainly based on quotations from folk music and structured in a simple couplet-refrain form, which predominated in the middle of the nineteenth century, to a new type of cultivated, salon horă, with broader architectonic forms and a more complex harmonic language, which had crystallized by the time of Independence. The full extent of the dissemination of this genre in the period of the 1877–78 War can be grasped only by means of the collection Horele noastre (Our Ring Dances), assembled by folklorist Dimitrie Vulpian (1848–1922) and containing 500 musical compositions and texts.Footnote 53

The proclamation of the Kingdom of Romania and the coronation of Carol I in 1881 were to produce a profound echo among the army’s composers. The Cantata triumfală (Triumphant cantata) for mixed choir and orchestra, set to verses by Alexandru Macedonski, Zece Mai 1881 (Ten May 1881) by Eduard Hübsch, Steaua României (The Star of Romania) by Ludwig Wiest, România Liberă (Free Romania) by Anton Kratochvil, Senior, Imnul regelui Carol (The Anthem of King Carol) by Wilhelm Humpel (1831–c.1899), and the România waltz by Iosif Ivanovici marked, by way of the art of music, Romania’s entry into the ranks of Europe’s great monarchies.

Choral Activity in the Military Bands

In 1836, the ‘Choir of the Singers of the Ștabul Oștirii’ was founded in Bucharest by the regiment’s former priest, a Russian archimandrite by the name of Visarion. Having joined the army as a priest with the salary of a captain, Visarion, or ‘Popa Rusu’ (Russian Priest) as he was known in the period, established the first church choir ‘according to the image of the imperial Kapelle in Petersburg’,Footnote 54 an ensemble that took part in liturgical services on certain festive occasions. Archimandrite Visarion in effect proposed the introduction of Russian harmonic liturgical chant set to Romanian words, as opposed to the Byzantine monody which at that time dominated the whole of Orthodox ritual in the two Danubian Principalities. In time, however, the ‘Choir of the Singers of the Ștabul Oștirii’ was required to broaden its activities, training the instrumentalists needed in the new historical and cultural context (including bands members), as well as opera singers.Footnote 55 The courses were spread over four years, and besides Byzantine musical notation, the theory of music and harmony were also studied. In 1849, two separate branches of musical training were introduced: vocal courses and instrumental courses.Footnote 56 Over the course of its three decades of existence (1836–1863), the choir, which underwent several title changes (including The Military School of Ecclesiastical Music), was the only form of institutional musical education in Bucharest in that period.Footnote 57

On 2 July 1848, serdar (a middle-rank boyar position, from the Turkish serdār) Alexandru Petrino (c. 1816–c. 1865) was appointed, by High Princely Order for All Moldavia, choral professor to the lower ranks of the Line Regiment in Iaşi. A born teacher, Petrino compiled and published for the regiment’s officers a book containing the elementary principles of music, to which he also added solfeggio exercises: Gramatică de muzică vocală pentru clasul filarmonic filarmonic (Grammar of Vocal Music for the Philharmonic Class) (Iaşi, 1850) (Fig. 9). Unfortunately, the school functioned for less than two years (2 July 1848–16 November 1850),Footnote 58 and the ‘professor of vocal music at the Veniamin Seminary and the Military Kapelle’, as Petrino is described on the title page of the book, was also required to serve as choir professor to the Russian troops of the Lyublin Regiment between 1848 and 1854.Footnote 59

Fig. 9 Alexandru Petrino, Gramatică de muzică vocală pentru clasul (Iaşi, 1850)

Choral activity in the military bands during the period of the War of Independence was not institutionalized, and more often than not it unfolded according to the context, being limited to patriotic, martial or society music. Of the few war documents that have survived, worthy of note is the diary (Note de front), kept between 1876 and 1888 by Sergeant Constantin C. Berceanu (1857–1947), who laid the groundwork of the ‘first vocal choir to be established in the army’, as he claims,Footnote 60 despite the fact that the first vocal groups had been organized as early as 1836 (see, the ‘Choir of the Singers of the Ștabul Oștirii’). Comprising 14 soldiers with a musical education, the group that he organized as a regimental choir performed every evening for the regiment fighting at the fronts of Vidin and Plevna (towns in what is now Bulgaria), becoming a model of choral education for other structures in the army: ‘Our choir aroused great enthusiasm and a resounding success. Officers came from other regiments, took part in the exercises we did, and took notes. Afterwards, choirs began to be formed in the other regiments’.Footnote 61

The compositions recorded over a period of 12 years in Sergeant Berceanu’s Notes are from the then-current repertoire, which undoubtedly reflects the musical taste of the middle class and the vogue for patriotic works. According to Viorel Cosma, who has possession of the diary, it mentions ten compositions dating back to the epoch of the Independence War of 1877–78 or even earlier. It is interesting to note that these patriotic creations also include a work that Cosma believes may be a pastiche based on an aria from Rossini’s Tancredi.Footnote 62

The Regulations and Structures of the Military Bands

The increasing number of military bands and their growing complexity, both in terms of repertoire and instrumentation, led the Ministry of War to establish in 1864 a special department to administer the eight bands in existence in Moldavia and Wallachia at that date. The department was headed by Captain of the General Staff Nicolae Dona. Three years later, on 19 March 1867, the department became the General Inspectorate of Military Bands, this time under the directorship of a first-class head of music, Eduard Hübsch. Hübsch was to draw up the Regulations for Military Bands, which organized them according to military branch (artillery, cavalry and infantry),Footnote 63 and also wrote a major study of military bands in Europe.Footnote 64 Hübsch was in charge of the military bands until his death, in Sinaia, on 9 September 1894.

After 1878, the position of band conductor was filled on the basis of a competition presided over by a commission made up of five members from the ranks of the heads of music and civilian professors in the field, appointed by the Minister of War.Footnote 65 Likewise, candidates were required to present a testimonial from the Music Conservatory and a certificate of good conduct.Footnote 66

After the War of Independence, as a result of reorganization of the infantry regiments, and given their shortfall of military musicians as well as the fact that many regiments had already received from the local civilian authorities proposals to join in the establishment and upkeep of military bands, the army’s ruling bodies decided that each infantry regiment should have such an ensemble, so that ‘the counties and communes have the right to enjoy the regiment’s band in public parks and at parades and solemn occasions’.Footnote 67 The putting into effect of this decision meant that, in addition to duties in their military units, the bands engaged in extensive public activity, in particular during the summer, when they performed in parks, public squares and spa resorts, a veritable concert season that made an essential contribution to their artistic level and to enriching their repertoire.

Iosif Ivanovici, who on 26 May 1895 became the general inspector of military bands in the Principalities, made a further invaluable contribution to the training of military musicians. In addition to his outstanding qualities as a pedagogue and composer (he composed more than 300 miniature pieces), Ivanovici also proved to be a highly able leader, reorganizing the military bands and supplying them with instruments and rich and varied repertoires. It was also Ivanovici who organized the first institution for the musical education of young people: the children of the troops.Footnote 68 With regard to their professional education, which began at the age of 14, the Regulations of the Institutions and Education of Children of the Troops established two possible paths: ‘one designed to train military combatants and instructors, and the other to create craftsmen and musicians for army service’, depending on their aptitudes.

Up until the foundation of the Military School of Music in 1936 by Colonel Egizio Massini (1894–1966),Footnote 69 it was in this framework that all the sub-officers of the Romanian military bands were trained, as well as almost all the wind instrumentalists of the symphonic theatre, opera and operetta orchestras of the country’s various cities, thereby making a major contribution to the musical life of the nation.

Epilogue

As we can see, as part of the wider phenomenon of inter-culturalism and artistic influences that characterized the Romanian nineteenth century, the military bands played a vital role in laying the groundwork for the emergence and promotion of Western musical culture in the two Danube provinces. In addition to their military duties, these wind ensembles took part in all the musical events of the time, initiating concert seasons in the proper sense and sometimes supplying musicians to play in the wind sections of the ad hoc symphony orchestras that were being organized in all the major cities of Wallachia and Moldavia.

It should be emphasized that direct contact with all the forms of Western musical life not only resulted in the closing of a historical gap, which was in any event the goal of the native social elite, but also provided the ideal framework for musicians in the genre to make careers and names for themselves at every level: as conductors, instrumentalists, composers, pedagogues, music critics and organizers of civil and military musical life, thereby making a decisive contribution to the modernization and professionalization of the military orchestras and, implicitly, to the construction of an acoustic identity within the wider framework of the Romanian nineteenth-century national musical culture.