Recent research into the musical life of eighteenth-century Britain has uncovered a wealth of new information on the lives and musical achievements of the country's native composers, many of whom have been overlooked in favour of their continental rivals.Footnote 1 Of all these foreign musicians, the most notable was Handel, whose works came to dominate eighteenth-century concert programmes and did much to eclipse the native talent. Handel's achievements were indeed great, but the neglect of the domestically composed music led to a general acceptance that this music was not worthy of attention.Footnote 2 Other important foreign musicians, such as Haydn, Mozart and Mendelssohn have likewise received notice for their contribution to British music, even though they spent relatively short periods in this country.Footnote 3 In the second half of the twentieth century there was a growth in appreciation for the music produced by Britain's domestic composers, and it is now accepted that Britain was not the barren musical wasteland that some would have us believe.Footnote 4 Today, some of the most highly regarded London-based native composers from the eighteenth century are William Boyce, William Croft, Thomas Arne, Maurice Greene and John Stanley. Even the numerous British composers that worked in the provinces have been acknowledged for their contribution to British music; some of the most distinguished of these are Charles Avison, Thomas Linley and his son Thomas Linley junior, William Hayes, William Felton and Richard Mudge. Furthermore, this research has proved that eighteenth-century Britain was far from being a musical wilderness, and that music was widely composed and performed throughout the entire country, where it found favour as an attribute of middle-class life. Important musical centres outside London included Durham, Newcastle upon Tyne, Bath, Oxford, Manchester, Leeds, Edinburgh and Dublin.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, there still remains a great deal of work to be done on provincial music in Britain and a significant number of medium to large towns and cities, many of which were also significant hubs of musical life, have yet to be investigated in any depth.

Most towns of importance had their own resident professional musicians, many of whom had relocated to that place to fill a vacant position, often as organist at a local church. Other places, particularly those of a rural situation, drew upon what local talent they had and were either unwilling or unable to finance the salary of a more capable musician from elsewhere.Footnote 6 Towns such as Newcastle were more fortunate with their indigenous musicians, for their musical life owes a great deal to Charles Avison, the organist at St Nicholas’ Church and son of a Newcastle town wait.Footnote 7 Others, such as William Avison, Edward Miller, John White, and Matthias and Thomas Hawdon, relocated from their birth towns to fill a suitable organist position.Footnote 8 These new arrivals would organize concerts and other public events that involved music in order to increase their incomes, a move that burgeoned the musical life in these places. At Durham there was a huge increase in the number of concerts and other public entertainments as a result of the removal of a large number of able musicians from the south of the country, all of whom were attracted to that city by the unusually high salaries that the cathedral offered.Footnote 9 Durham Cathedral's chapter was able to afford these high salaries because of the vast tracts of land the cathedral owned, from which coal was mined and shipped to London. Other north-eastern towns such as Newcastle, and to a lesser extent Sunderland and Hull, grew wealthy on the back of the Industrial Revolution and became important ports for the shipment of coal. As these ports developed they attracted other industries, such as ship-building, and there was a growth in the number of secondary professionals including accountants, bankers, architects and dentists.Footnote 10 Furthermore, as the wealth of the inhabitants grew, many of these towns also cultivated a rich musical life. It is undoubtedly because of its prosperity that Newcastle had one of the first subscription series out of London, established by Avison in 1735.Footnote 11 Other, smaller, ports witnessed significant growth over the course of the eighteenth century, as the thirst for mined resources grew. The most remarkable of these was Whitehaven, which grew from an inconsequential coastal hamlet into one of the most important provincial ports in the country and, in doing so, cultivated a musical life that rivalled that of any other major town.Footnote 12

Whitehaven is one of the most unlikely places to have been an important musical centre. Its location on the west coast of Cumberland (now Cumbria) made it difficult to reach, and the Lakeland fells, which hemmed in the town and prevented its expansion, isolated it from mainland Britain. Access to the town was further hampered by the poor quality of the roads.Footnote 13 The most accessible route to Whitehaven was by sea, and it was through its harbour that it developed into a centre of considerable wealth.Footnote 14 Its affluence, like that of Newcastle, was founded on the shipping of coal, although in Whitehaven's case the ore was transported to Dublin and the colonies.Footnote 15 The town was also, for a time, an important centre in the trade of Virginian Tobacco and to some degree the export of iron. Whitehaven's expansion was entirely due to the efforts of the Lowther family, particularly John Lowther (1606–1675) and his son James (1673–1755). They made a fortune from their endeavours, so much so that James was considered the ‘richest commoner in England’.Footnote 16 There was, as part of this expansion, a huge migration to Whitehaven, evident from population numbers: in 1693 there were still a relatively modest 2,222 inhabitants, which rose to around 4,000 in 1714 and over 9,000 in 1762.Footnote 17 Although Whitehaven's population never came close to that of other important ports, such as Liverpool and Bristol, according to Daniel Defoe it was ‘the most eminent Port in England for shipping off Coals, except Newcastle and Sunderland’ and, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was viewed as the largest town in the north of England after Newcastle and York.Footnote 18 It was even important enough to warrant an attack by the American privateer ‘Ranger’ in the American War of Independence.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, such growth was not without its consequences. As the population grew, most new building work was accommodated within the town's existing boundaries and, as a result, certain areas, particularly around the harbour, degenerated into slums of disease and vermin.Footnote 20

The town itself was arranged like other eighteenth-century ‘new towns’, in the pattern of a right-angled grid. Hutchinson recorded that the town consisted ‘of wide elegant streets; the houses built in a modern style and good taste.’Footnote 21 There were three churches, the oldest of which was dedicated to St Nicholas and located prominently at the town's centre. It was rebuilt in 1693 to accommodate the increase in population. The other two churches, dedicated to the Holy Trinity and St James, were consecrated in 1715 and 1752. Of these three churches, the most important musically was St Nicholas’.

Fig. 1 St Nicholas’ Church, Whitehaven, from Hutchinson The History and Antiquities of Cumberland (1794), II, 43. Reproduced from the author's collection.

Although it is unlikely that quality of the music produced at St Nicholas’ Church ever rose particularly high in the first half of the eighteenth century, the erection of an organ in 1756 by the eminent builder John Snetzler marked a turnaround in the musical situation of that church and ultimately of Whitehaven itself.Footnote 22 The organ's installation would not have been without its concerns, as there were few skilled organists in the county and, as in Doncaster, Hull and Beverley, the churchwardens were forced to look elsewhere for a suitable candidate; as a result, the church's first organist, William Howgill, was procured from Newcastle upon Tyne.

William Howgill appears to have spent all of his formative years in the north-east of England. He was born in Sedgefield, Country Durham in 1735 and baptised at his parish church of St Edmund on 12 August. He was the youngest of six children,Footnote 23 and a son of William (c.1690/1–1768), the schoolmaster at Sedgefield's Grammar School, and Jane (1693/4–1765).Footnote 24 Nothing certain is known about the younger William's early life, but he must have studied at Sedgefield Grammar School and been given the opportunity to learn music. He presumably received lessons from the eminent composer and concert organizer, John Garth (1721–1810), the organist at Sedgefield Church. Howgill may also have played in Garth's Durham-based concert orchestra, in which Avison also participated. By 1755 Howgill had relocated to Newcastle where he most likely played in Avison's orchestra and cut his teeth as an organist at one of the town's churches.Footnote 25 He subsequently moved to Whitehaven in 1756. On 4 September 1766 he married Ann Rochfort, the daughter of the parish clerk at Holy Trinity Church.Footnote 26 They had six children, four of whom survived childhood. These were William, Matthew, Ann and Thomas. William (hereafter referred to as William Howgill junior) was christened on 2 July 1769 at St Nicholas’ and was the most musical of that family. Ann, baptised on 10 May 1775, also became an organist.Footnote 27

There is no record of Howgill senior's early musical life at Whitehaven. The Cumberland Pacquet, the main source of information on events in the town and the first established newspaper in the county, did not commence until 1774.Footnote 28 The first recorded concert at Whitehaven was held on 27 February 1775 in the Assembly Room on Albion Street, the regular venue for such activities.Footnote 29 Public concerts had first been established at London in 1672 and had quickly spread. They had certainly reached the north-east by the first decade of the eighteenth century.Footnote 30 Howgill, given his association with Garth and Avison, must have been aware of the profits that could be made from concert organization, and he almost certainly held his first concert soon after his arrival, perhaps even to mark the opening of the Whitehaven organ. He held concerts biannually at the Assembly Rooms, usually in March and November, both of which were followed by a ball.Footnote 31 He also held smaller weekly concerts at his home.Footnote 32 Howgill's ticket prices, at two shillings each, were substantially cheaper than those in the capital and even cheaper than those at other provincial centres such as Durham and Newcastle.Footnote 33 He may also have initiated the Whitehaven Musical Society, which subscribed to Avison's op. 9 concertos in 1766.Footnote 34

Little is known about the programmes of Howgill's early concerts. He did subscribe to several works, the music of which must have been used at Whitehaven. Almost all of these works have a north-east connection, and include Avison's opp 3 and 4 concertos (1751 and 1755), Thomas Ebdon's keyboard sonatas (c.1765), Garth's op. 2 keyboard sonatas (1768), Garth's English version of Marcello's psalms (1757), Robert Barber's op. 1 keyboard sonatas (c1775) and Matthias Hawdon's An Ode on the King of Prussia (c1760).Footnote 35 From 1778 programmes began to appear in the Pacquet alongside concert advertisements. These lists reveal that, in spite of Whitehaven's isolated location, the domestic concerts included some of the most recently published music. For example, the harpsichord concerto by Johann Samuel Schröter, which was performed on 25 March 1778, was probably from his op. 3, published in London in 1774.Footnote 36 There was an even shorter time lag between the London and Whitehaven performances of William Shield's ‘Ode in Honour of Captain Cook’ from the pantomime Omai; it was performed on 3 April 1786 after its Covent Garden premiere on 20 December 1785.Footnote 37 The fact that some of the most contemporaneous music was performed at Whitehaven indicates that either the Howgills made regular trips to London to acquire the most recent publications, or that they had contacts in London who were able to forward new music to them. This contact does not appear to have been one of Howgill's siblings, as they remained in Sedgefield and had little cause to visit the capital. However, his wife's family were firmly established in London and may have provided assistance.

Another place where Howgill may have been involved with music production is Whitehaven Castle, the town residence of the Lowther family; James Boswell recorded that in January 1788 the dancing there was accompanied by ‘two fiddles, a bass, a tabor pipe, and two clarinets.’Footnote 38 Music was also played at the Whitehaven theatre, and Howgill senior supplied them with an orchestra.Footnote 39 The theatre was a regular venue for ballad operas and pantomimes, a large number of which were composed by Shield.Footnote 40 Howgill senior clearly had a huge impact on the musical life of this insular community. The high esteem in which he was held by the local populace is evident from his obituary:

Friday last, in Roper-street, in the 55th year of his age, and after a long illness sustained with much fortitude, Mr. WILLIAM HOWGILL, organist of St. Nicholas's Chapel in this town; which office he filled with great propriety during a period of thirty-four years; respected in his profession, and in private life, by a very numerous acquaintance. His remains were interred at the said chapel, on Sunday evening, attended by a large concourse of people. He is succeeded in the office of organist by his eldest son, Mr. William Howgill, who has performed the duties of it for some years past.Footnote 41

William Howgill junior, like his father, was an able musician. He was also something of a child prodigy and participated in his father's concerts from a young age. In 1779, at age ten, he played the upper part of a harpsichord duet that ‘gave astonishing proofs of an early knowledge of the science in which he promises to be very eminent.’Footnote 42 Less than two years later he had his first opportunity to play for both Sunday services at St Nicholas’ Church:

Sunday last, at the Old Church, Master Howgill (who is only eleven years of age) son of Mr. Howgill, organist of this town, performed the whole service on the organ both parts of the day, which consisted of six psalm-tunes, and four voluntaries. The former were executed with such steadiness and solemnity as would have done credit to a performer of long practice; and when it is considered that this instrument has a hard touch, it is a matter of astonishment how such a smooth succession of tones could be produced by the fingers of so young a person. His voluntaries were not less surprizing. The intermediate one in the evening service, however, gave him an opportunity of displaying still more uncommon abilities at his years. It contained four different movements, and his frequent and easy transitions from the chair organ, to the swell, and the full organ, while it afforded great pleasure to all those who are alive to the divine impressions of music, excited real amazement in those who are acquainted with the construction of the instrument. – It may very reasonably be presumed that Master Howgill is in the way of becoming very eminent in his profession if these exertions of so young a genius do not already entitle him to that character.Footnote 43

A few months later another performance at one of his father's concerts aroused the attention of the Pacquet:

Wednesday evening there was a very genteel company at the Public Concert, and a more numerous one than has been for some years past. The performances gave universal pleasure, particularly [George] Rush's celebrated Harpsichord Concerto, the harpsichord by Master Howgill, which he played in a manner that astonished and delighted all present. His performance as to exactness of time, and neatness of execution, was allowed to be such as might have been applauded by the greatest connoisseurs in Music.Footnote 44

In some ways the achievements of Howgill junior mirrored those of another child prodigy, William Crotch (1775–1847). In 1781, at the tender age of six, Crotch visited Whitehaven where he performed at a benefit concert on 21 November alongside Howgill junior.Footnote 45 Crotch's abilities are particularly evident from a report of a second performance, this time at the organ of St Nicholas’:

Thursday last Master Crotch played upwards of an hour upon the organ in the Old Church, and, if possible, surprized his auditors more than he had done before by his performances on the harpsichord and piano-forte. The curtains were tucked up close, to give all present a view of this musical prodigy, who was seated on his mother's lap, and ran his fingers over the keys with a fluency peculiar to himself, in perfect harmony, through a great variety of pieces, and occasionally on the full organ producing such a tone (the weakness of an infant's fingers considered) as must exceed all belief, except in those who have had an opportunity of feeling and hearing him.Footnote 46

Howgill junior continued to participate in his father's concerts where he played some of the latest and most fashionable music available. In 1785 he performed a keyboard sonata by Luigi Boccherini, presumably taken from his popular op. 5 set from 1775, while in 1787 he executed a keyboard concerto by Johann Sterkel.Footnote 47A Favorite Concerto from Sterkel's op. 20 was published at London in 1786 and it was probably this edition that was used.Footnote 48 This work and others may have been acquired in 1786 when Howgill junior went to London to receive music tuition.Footnote 49 Howgill senior took advantage of his son's trip for further profit as he offered to procure musical material from the capital for interested parties.Footnote 50 After his father's death, Howgill junior provided a similar purchasing service and made several trips to London to acquire new music and instruments.Footnote 51 According to an 1814 advertisement, new music was sent to him once a month and he sold pianos from his house.Footnote 52

In the years immediately after his father's death, Howgill junior appears to have carried on his father's musical activities with little interruption. The biannual concerts were still held at the Assembly Rooms, the programmes for which appeared in the Pacquet until 1797. Howgill junior expanded his musical productions into other neighbouring towns and organized concerts at Cockermouth in 1789 and 1791. However, as the end of the century approached there was a clear reduction in the number of concerts organized at Whitehaven, a situation that has already been observed at other provincial towns and cities.Footnote 53 The reason behind this decline appears to have been financial, caused by a reduction in the numbers of tickets sold. It is perhaps more than a coincidence that at this time Britain was at war with France, and it was presumably the threat of an invasion that diverted people's attention onto more pressing matters.Footnote 54 Howgill junior also continued his father's role as a music teacher, and he appears to have enjoyed considerable success. He set up a music school at Cockermouth, which ran from at least 1791 until 1793.Footnote 55 At Whitehaven, Howgill junior taught the pianoforte, harpsichord and violin on Monday, Tuesday and Thursday at his home on Church Street and at the homes of his pupils. Like James Hesletine, Ebdon and Garth, Howgill junior taught in the country, but the rate he charged was subject to the pupil's distance from Whitehaven.Footnote 56 In 1802 he proposed to return to teach in both Cockermouth and Workington once he had sufficient pupils in those towns, but it is unknown whether this proposal came to fruition.Footnote 57 Presumably many of Howgill junior's pupils made up his concert orchestra, although little is known about who they were. At a concert held in 1789 two pupils, ‘a brother and sister the eldest 14 years of age’, performed a harpsichord duet by Tommaso Giordani.Footnote 58

At St Nicholas’ the Howgills, aided by their parish clerks, played an important role in the training of the singers.Footnote 59 From the 1750s, the parish clerk was Joseph Wilde (1711/2–1785), who may have been ill at Christmas 1774 when the pupils of a Mr Parcival sang.Footnote 60 Wilde was succeeded by Isaac Wilkinson (1743/4–1795) in 1785 and he was followed by Wilkinson's son Matthew in 1795.Footnote 61 The Howgills certainly had access to a choir from an early stage and were able to perform choruses at concerts from at least 1779. In 1788 there was an established ‘Choral Society’, presumably run by William Howgill junior.Footnote 62 For Easter 1785, a ‘Choral Hymn’ setting of Psalm 96 by William Jackson, organist at Exeter Cathedral was sung, a performance that was spoilt by the ‘intrusion and rude behav[i]our of some people’.Footnote 63 Another performance in 1786 was directed by Wilkinson and performed by his scholars with the assistance of ‘several bass and tenor voices’.Footnote 64 By 1786 the choir had grown to ‘46 men and boys’.Footnote 65 On one occasion the ‘Sunday Scholars’ that had attended the evening service, which numbered one hundred and sixty strong, sang several psalms with the organ after the service's conclusion and there were plans to repeat this event every second Sunday.Footnote 66 Such large numbers of young singers was not unusual, and places such as Box in Wiltshire had similarly sized choirs of boys much earlier in the century.Footnote 67 The church at Lancaster also had a large number of boy trebles in their choir.Footnote 68 After the death of his father, Howgill junior took over the tuition of the Sunday school singers, assisted by Edward Miller's important hymnbook The Psalms of David. Footnote 69 This collection of hymns was, according the Miller, ‘the first publication of congregational psalmody that … [had] appeared since the Reformation’, and it was exceptionally well subscribed.Footnote 70 The Pacquet thought that its introduction had greatly enhanced worship at St Nicholas’, and produced printed books of the words.Footnote 71 It may have been because of Howgill junior's recommendations that in February 1792 it was agreed that pews would be erected on either side of the organ to seat the choir in emulation of the practice at other provincial churches where the choir was positioned on the west gallery.Footnote 72 Other works performed at around this time at St Nicholas’ include an anthem from Ebdon's first collection of Sacred Music, sung on Christmas Day 1793; another by Ebdon, ‘Teach me, O God’, was executed in 1817.Footnote 73 John Alcock junior's anthems ‘Clap your hands ye people’ and ‘This is the day which the Lord hath made’ were both performed in 1791; for the latter performance, also held on Christmas Day, Howgill junior performed ‘two solos’ and a ‘verse’ while Ann Howgill was praised for the way she sang a high C ‘full and clear; a height which very few voices can reach’.Footnote 74 Ann's participation in the anthem was not unusual as mixed choirs were in existence at this time. The choirs of both the Hey and Shaw chapels in Lancashire had included women since the 1750s, and the Halifax 1766 musical festival used female sopranos rather than boy trebles. Cowgill attributed the presence of female trebles to the fact that Halifax was not a cathedral city; however, even though there was no salaried cathedral choir at Whitehaven, boys were commonly employed to sing the treble line.Footnote 75 The extent of the involvement of female voices at Whitehaven is unknown, but a few may have been used to support the treble line on a regular basis and take on the more difficult solos.

In terms of organ music, Corelli's ‘Natale’ (the ‘Christmas Concerto’ op. 6, No. 8) was frequently performed on Christmas Day.Footnote 76 The organ voluntaries of Matthias Hawdon also appear to have been popular.Footnote 77 A more usual performance took place in 1783 when William Howgill and his son gave the premiere of a version of the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’, arranged for organ duet by the Whitehaven amateur musician Thomas Bacon.Footnote 78

Although the Howgill family was the dominant musical force in the Whitehaven area, they were by no means the only professional musicians to live or work in that place, although most of them were of little or no competition to either Howgill senior or his son.Footnote 79 Many of the dancing instructors who worked in the town were capable musicians, but they never sought to infringe on the Howgills territory and did not organize any concerts. One of the most notable of these dance masters was a Mr Hadwen, who organized an annual ball at the theatre that showcased his pupil's abilities.Footnote 80 Another amateur musician was a Mr Wilson who set a song in memory of William III.Footnote 81 Even outside Whitehaven itself, the Howgills appear to have experienced little rivalry. Public concerts at other west Cumbrian towns appear to have been rare events and, even when they did happen, they were usually organized by Whitehaven-based musicians. One of the few advertised concerts not organized from Whitehaven was held at Workington in 1781 and promoted by a Mr Eckford and a Mr Mingay.Footnote 82

Like many other provincial towns, Whitehaven was visited by numerous transient musicians, though few are recorded. In 1800, Charles Dibdin came as part of his tour of the northwest; Charles Incledon (1763–1826) was there in 1820.Footnote 83 Other visitors include a Signor Rossignol, who imitated a violin and produced birdsong with his voice, the singer Mrs Boyle and a Mr Roche, who played the psaltery.Footnote 84 Mr Saxoni, the tightrope dancer, was there in 1798; Howgill junior certainly attended one of his performances as he composed a set of variations on Saxoni's favourite Dance.Footnote 85 The polish dwarf, Joseph Boruwlaski, visited in September and October 1799, and described the town as ‘a hive of industrious bees, forbidding the butterfly to taste their honey.’Footnote 86 He was assisted at one of his concerts by the Band from the Regiment of the Isles.Footnote 87 It was common for visiting bands to be used in this way, and they were similarly employed for concerts at Carlisle, Newcastle and Durham.Footnote 88 In 1783 the Howgill's were assisted by the forty-seventh regiment, who played between the acts of the concert; they presumably also played at the subsequent ball which featured country dances and ‘continued till after three the next morning.’Footnote 89 Another visiting musician was notable for his strange behaviour. He was the Frenchman Mr Martinis, who had arrived in Whitehaven in May 1789. Like Rossignol, he had the ability to imitate numerous musical instruments with his voice and was well received at his first performance.Footnote 90 Another performance was arranged for the following week but, even though the audience assembled for his recital, Martinis never appeared. He subsequently reappeared at Ulveston without any prior announcement from whence he disappeared after only two nights.Footnote 91

Howgill junior continued to dominate musical production at Whitehaven in the years immediately after the death of his father although his importance began to wane as others sought to gain a bigger foothold in the town. The start of Howgill junior's decline appears to have been his decision to resign from the organist's post at St Nicholas’ in 1795. There is no known reason why he suddenly gave his notice, but it may have been due to a dispute with the minister or another senior member of that church. The first evidence that there was a problem comes from the Pacquet where the following advertisement appeared:

To ORGANISTS

WANTED, an ORGANIST for ST. NICHOLAS's CHAPEL.

No Attendance required but on SUNDAYS. Salary

TWENTY POUNDS. Application to be made to the Chapel

Wardens.Footnote 92

There must have been few applicants, for a month later the advertisement reappeared with the following addition: ‘It is requested that any Person inclinable to offer, will be speedy in the Application.’Footnote 93 By mid-August, the issue that forced Howgill junior's resignation appears to have been at least partially resolved, as he opted to remain in post. However, even though this storm had passed, another appears to have struck in 1799, when Howgill junior resigned a second time.Footnote 94 If he believed that his reinstatement was assured then he was to be disappointed, as a Mr Gledhill, a pupil of Johann Salomon, was appointed in his place.Footnote 95 Losing his post would have only been the start of Howgill junior's troubles, for Gledhill set himself up as a rival tutor and seller of music and instruments. Later that same year Gledhill proposed to re-establish the weekly concerts, which had presumably been discontinued in 1797. This move led to Howgill junior's proposition for a weekly series the following year.Footnote 96 Fortunately for Howgill junior, in 1801 Gledhill was elected organist at the New Chapel in Horbury, and Howgill was able to regain the organist's post at St Nicholas’.Footnote 97 He must have received some satisfaction from his reappointment, but any complacency was to be short-lived, as other competitors began to appear. In 1802 a Mr Cummins, who taught at one of the Whitehaven schools, offered lessons on the violin and piano. A more serious threat emerged in 1815, when a self-proclaimed ‘Professor of Music’, James Scruton, set himself up as a music teacher and concert promoter at Whitehaven and offered to procure instruments from London.Footnote 98 For an 1816 concert Scruton was assisted by the Whitehaven ‘Harmonic Society’, a group that appears to have been established in that year.Footnote 99 The Harmonic Society quickly grew in stature, and they instigated a subscription series in 1818.Footnote 100 Another of Howgill junior's competitors, George Frederic Orre, led the orchestra for one of Scruton's concerts in 1816.Footnote 101 In 1819 Orre was appointed organist at St James’ after that instrument's installation; he also taught music and ran concerts, some of which were held at the theatre.Footnote 102 There is no reference to Howgill junior participating in any of Scruton's or Orre's concerts and it appears he was shunned by the competition.Footnote 103 He was conspicuously absent from the concert that marked the opening of the organ at St James’; another concert, run by Orre in 1819, included Thomas Hill, the organist at Carlisle Cathedral, and a Mr Parrin, the organist at Penrith, but not Howgill junior.Footnote 104 Orre went on to hold an annual benefit concert and branched out into other local towns such as Cockermouth.Footnote 105 Other competitors, such as Henry Sloan, set themselves up as music teachers, while William Stuart established a music business in Whitehaven.Footnote 106 Howgill junior, perhaps unwilling to step back into the fray, stopped advertising his concerts in the newspaper.Footnote 107 All of his later advertisements were aimed at those seeking instrumental lessons, or to promote his recent publications.Footnote 108

One of the biggest musical events to take place at Whitehaven in Howgill junior's lifetime occurred in October 1815 when a ‘Grand Musical Festival’ was organized by brothers General and Charles Ashley, and held at St Nicholas’ Church and the theatre.Footnote 109 Such musical festivals were not uncommon and most were in emulation of the London Handel commemorations, first held at Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon in 1784.Footnote 110 Other provincial cities and towns that held musical festivals in the wake of the Handel commemoration include Liverpool and Birmingham (1784), Leicester (1785), Sheffield and Louth (1786), Doncaster (1787), Derby and Norwich (1788), Manchester (1789), York and Newcastle (1791), Durham and Kendal (1792), and Carlisle (1807).Footnote 111 For the Whitehaven festival, Scruton played the oboe and Howgill junior the organ; the remainder of the band came from places such as London, York, Leeds, and Manchester. The selection included the motet ‘O God, when thou appearest’ by Mozart, excerpts from Haydn's Creation, Beethoven's Mount of Olives, Handel's Coronation Anthem, and a version of Messiah with additional accompaniments by Mozart.Footnote 112 A ‘Miscellaneous Concert’ was held each evening that included music by Corri, Bach (probably Johann Christian), Gluck, Webbe, Knyvett and other contemporary musicians. The Covent Garden organ was transported to Whitehaven for use in the theatre. Tickets were by no means cheap: £1 11 s 6d for all six events. Single tickets, except for the theatre gallery, were 7 s 6d.

Even though Howgill junior's importance in Whitehaven's musical life had begun to depreciate significantly by the early 1820s, there were some who still praised him for his musical talents. In October 1822 a substantial piece on Howgill junior and his music appeared in the Whitehaven Gazette that extolled his many achievements, particularly his musical publications, and drew heavily on the numerous reviews that had appeared in the Monthly Magazine. Howgill junior was clearly pleased with the Gazette's tribute, for he included a copy in the prefatory material to his Four Voluntaries (1824).Footnote 113 The week after the Gazette's accolade, the Pacquet added their praise:

The musical talents of Mr. Howgill have received so many and merited acknowledgements, that the necessity of saying more appears almost to be superseded. We should feel ourselves, however, liable to the charge of a want of taste did we withhold our tribute from Mr Howgill, or any one who has so successfully cultivated a science which communicates to all, in the least susceptible of feelings that at once “embellish and exalt,” the noblest and most refined satisfaction.Footnote 114

Howgill junior died childless in November 1824, at age 55, and his obituaries reflect the high esteem in which he was held. The Pacquet said that he was:

eminent for his musical talents, and much beloved of those who had opportunities of knowing him for many good qualities – firmness and independence of character, goodness of heart, and perfect integrity. To these he added an enthusiasm in every thing connected with his profession. His works are an honourable monument of his genius.Footnote 115

The Gazette said that:

[though he was ] somewhat eccentric in his manners, he possessed a noble and generous disposition. Few men could equal him as a performer; and he was the author of a variety of works which have justly obtained celebrity in the musical world. – But however high his name may rank as a musician, and however long his fame may live after him, it is for the kindly quality of his heart, his perfect integrity, the unassuming modesty of his demeanour, and for his good-humoured frankness towards his friends, that they will deeply mourn his loss and respect his memory.Footnote 116

His wife, Mary Ann (nee Bragg), whom he had married at St Nicholas’ on 13 November 1796, lived until August 1831.Footnote 117

There is little that we can say about the musical achievements of Howgill's two brothers, Matthew and Thomas, and neither appears to have had any involvement with the Whitehaven concerts. Matthew relocated to London, where he married his first cousin, Augusta Rochford (c.1768–1844), on 22 August 1799 at St Paul's Church, Covent Garden.Footnote 118 He followed in the footsteps of his father-in-law, Walter, and became a pawnbroker; Matthew died in 1813.Footnote 119 Thomas’ career is something of a mystery, although he may have worked with Matthew. He had moved to London by 1800 where he appears to have died in 1833.Footnote 120 Ann was unquestionably the most musical of William Howgill junior's siblings. She was appointed organist at Staindrop Church, County Durham in 1793, where she succeeded George Chrishop (1772–1803), the new sub-organist at Durham Cathedral.Footnote 121 In 1797 Ann became organist at St Andrew's Church, Penrith. She was still in post in 1805 when her mother died, but had left by 1816.Footnote 122 At Penrith she taught the harpsichord and the piano, and was able to procure music and instruments from London.Footnote 123 Ann disappears, presumably after her marriage, and it has been impossible to trace her subsequent movements.Footnote 124

Although it seems likely that all members of the Howgill family would have composed music, most extant pieces were written by William Howgill junior. The only secular piece that may have been composed by his father is the hunting song, ‘The Glowing East Aurora streaks’. It was published in 1786, but no copy has been traced.Footnote 125 Howgill junior was a fertile composer and had a considerable amount published. In this respect he was not unique, as other provincial composers had their own works published.Footnote 126 However, despite the number of Howgill junior's publications, few specimens have found their way into public libraries and only two items are held in multiple copies.Footnote 127 Another item, Sweet is the Seraph – a song with parts for piano, violin, and trumpet – is known to survive in a private collection.Footnote 128 Nonetheless, a good cross-section of material survives, and most of these publications were reviewed in the Monthly Magazine. Both of Howgill junior's collections of sacred music were issued by subscription; the earliest of these, An Original Anthem and Two Voluntaries… with a Selection of Thirty eight Favorite Psalm Tunes, appeared in 1800. It appears to have been a success, for it received 174 subscribers for 267 copies.Footnote 129 His Four Voluntaries, from 1824, was also well supported and received 351 subscribers for 377 copies. However, there were long delays in the issue of the latter as Howgill junior had difficulty procuring subscribers.Footnote 130

Howgill junior's earliest known composition, which was never published and is now lost, is a duet for performance by two musicians on one organ. It received its premiere at St Nicholas’ in October 1783, played by the composer and his father. According to the report, the work consisted of three movements, one of which was an adaptation of a ‘favourite Andante’ from Arne's Artaxerxes. Footnote 131 Another organ duet, performed the following year, had two movements, an ‘Andante’ and an ‘Allegro’.Footnote 132 A third duet, executed in May 1785, received an excellent review in the Pacquet:

It contains a great variety; and every idea of the youth of the composer must be lost, in attending to the ingenuity displayed in this most difficult species of musical composition. We suppose it would require a considerable share of knowledge in the science to distinguish in what the chief merit of this piece consists; the judges of music will probably soon have an opportunity of examining it; some of the passages adapted for the swell, and one movement for the flute-stop, will be found to possess uncommon beauty, –and we have only to add, that there is evidently a great and uniform sublimity of thought throughout the whole, the effect of which is solemnly grand and pleasing.Footnote 133

Of the songs that Howgill junior published in the 1790s, only ‘Gaffer Gray’ survives, although not in its first impression. It was popular enough to be included in two Whitehaven concerts. A slightly later song, ‘Marian's Complaint’, is also lost, but received a scathing review in the Monthly Magazine:

‘Marian's Complaint’, is one of those compositions which may defy criticism, because the reviewer, lost in the quantity of its defects, knows not where to commence his remarks.Footnote 134

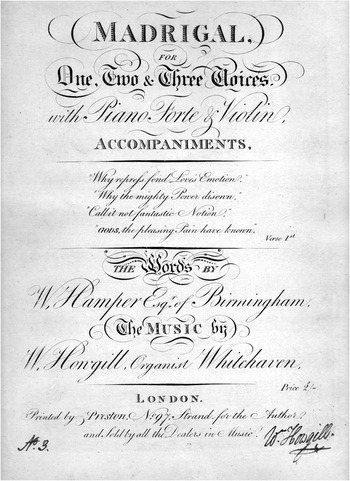

His Madrigal, for One, Two and Three Voices (see Figure 2) and his lost setting of the Ode on their Majesties’ Coronation received more favourable reviews in the Monthly Magazine. Footnote 135 The Madrigal, which has little in common those from the Renaissance period, has integral parts for piano and violin; it is a euphonious, but wholly Classical in style.Footnote 136 Another two songs, ‘Crazy Jane's Epitaph’ and ‘The Shopkeepers’, are extant; in the latter of these Howgill junior introduced several well-known themes, including ‘Rule, Britannia’, ‘Hearts of Oak’, ‘The Duke of York's March’ and the ‘Roast Beef of Old England’.Footnote 137 Howgill junior commonly included popular tunes in his compositions, and this is particularly evident in his secular piano sonatas. The use of popular tunes in keyboard sonatas was not unusual, and numerous examples can be found in the works of Jan Ladislav Dussek and, to a lesser extent, Muzio Clementi.Footnote 138 Many native British composers similarly employed such tunes in their sonatas, examples of which include those by James Hook, Matthew Camidge, Thomas Haigh and George Pinto.Footnote 139 One of Howgill junior's lost sonatas, dedicated to Lady Viscountess Lowther, included an exceptionally large number of these popular melodies.Footnote 140

Fig. 2 Title page of Howgill junior's Madrigal, for One, Two & Three Voices. Reproduced from the author's collection.

Most of Howgill junior's secular keyboard works, which are in the form of a keyboard sonata, were influenced by what was being published in the capital at that time; this important arena for the development of piano technique has become known as ‘The London Piano School’. Two of the most important proponents of this movement were J.C. Bach and Clementi, composers whose music featured in Whitehaven concert programmes.Footnote 141 In his sonatas, Howgill junior elected for a three-movement structure formed of an initial slow movement, followed by a faster and much longer central movement, and concluding with a theme and variations.Footnote 142 This tripartite layout was quite rare; far more sonatas from this period were written with two outer fast movements that enclose a central slow movement. Nevertheless, such a schema can be found in the sonatas of Leopold Kozeluch.Footnote 143

Most of Howgill junior's sonatas were written for pianoforte alone, although two have accompanying parts. His sonata dedicated to the Doncaster organist, Edward Miller, has accompaniments for a flute and a tenor (i.e. viola) while a later example, dedicated to a Miss Younger, has parts for flute and cello.Footnote 144 It appears in both cases that the accompanying instruments had an equal role to the keyboard. Little can be said of that role with Miller's sonata, as the accompanying parts are missing, although there are several instances, most conspicuously in the theme and variations, where the keyboard part adopts an accompanying role.Footnote 145 The equal sharing of melodic material is more evident in his sonata to Miss Younger where the flute frequently takes the lead.

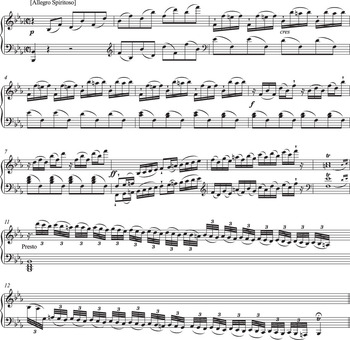

The style of writing in these sonatas demonstrates a wide range of influences. One of the strongest of these was Dussek who, like Howgill junior, had a fondness for full, thick chords. Another important influence was Clementi, who was known for his rapid writing in thirds, sixths and octaves.Footnote 146 His influence is evident in the central movements of Howgill junior's sonatas, which have long passages of rapid octaves and thirds, fast semiquaver arpeggios and scales, the crossing of hands and large leaps of up to an eleventh. This virtuosic nature can be seen from the closing bars of the penultimate movement of the sonata dedicated to Lady Lawson (see Example 1).

Ex. 1 Howgill junior: Sonata dedicated to Lady Lawson, second movement, bars 194–204

The central movement of the sonata dedicated to Miller stands out among Howgill junior's sonatas, as it has a clear sense of structure, evident from the use of sonata form (see Table 1).

Table 1 Plan of the ‘Allegro Spiritoso’ from Howgill jnr's sonata dedicated to Edward Miller.

Although the material used in the ‘development’ is more transformed in nature than in earlier British sonatas, the music is not truly developmental; in fact, the music gets stuck in G major and there is little effort to push it any further from the tonic, which is unlike the mature sonata forms of Mozart and Haydn or even those of Howgill junior's London contemporaries. Instead, his ‘development’ is little more than a series of rapid semiquaver scales and arpeggios.Footnote 147

Howgill junior's preferred structure for his long central sonata movements was to have two tonally closed sections, each of which are through-composed with no recapitulated material. This plan can be seen in his sonata dedicated to Mrs Dykes of Dovenby Hall, near Cockermouth. The first half of the central movement is in B♭ major, and the second in E♭.Footnote 148 Although it is unlikely that Howgill junior was the only composer to use this form, it never caught on.Footnote 149 Even though Dyke's sonata has a distinctly Mozartian flavour, as seen in Example 2, this entire movement is little more than a series of disparate, and rather tedious, pianistic textures.Footnote 150

Ex. 2 Howgill junior: Sonata dedicated to Mrs Dykes, second movement, bars 1–14

In his sonata dedicated to Miss Younger, Howgill junior opens with a short prelude by Handel and concludes with a series of variations on ‘Je suis Lindor’.Footnote 151 Mozart was almost certainly Howgill junior's influence in his choice of ‘Lindor’ as his theme. Mozart's ‘Lindor’ variations were written at Paris in 1778 and published in London by 1802.Footnote 152 The final movement of Howgill junior's lost sonata, dedicated to Miss Dawson, uses another Mozart theme for its variations, ‘Lison dormoit’.Footnote 153

Other points of note in Howgill junior's sonatas are the four-movement layout of his sonata to Lady Lawson. In this work the first two movements are short, and full of rapid keyboard flourishes, while the third movement is a substantial bisectional movement. The sonata concludes with a march written for the Royal Lancashire Volunteers. Military marches were common at this time and many composers wrote then to support their own local militias. Examples were published by Shield, John Friend, Humphrey Hime, John Clarkson and William Russell.Footnote 154 Howgill junior's other extant sonatas are both dedicated to local hunts, the Inglewood Hunt and the Whitehaven Hunt, and follow in the wake of similar sonatas by H.B. Schroeder and James Hook.Footnote 155 Both of Howgill junior's hunt sonatas are programmatic and provide, in music, an account of a day's chase.Footnote 156 Most individual movements in these two sonatas are through-composed, although some, such as the movement ‘Returning home’ from the Inglewood Hunt, have a ternary form. Several movements are challenging with the use of hemidemisemiquavers that rapidly cross the keyboard. The Whitehaven Hunt concludes with an arrangement of ‘God save the King’.Footnote 157

Other works for keyboard by Howgill junior include his variations on Saxoni's dance and his hundred variations on the ‘Welsh Ground’,Footnote 158 spuriously attributed to Purcell.Footnote 159 Another piece for piano, a capriccio, was included in his Four Voluntaries. Footnote 160 This capriccio begins with a theme and four variations before Howgill junior launches into the main body of the work, a series of incongruent movements that explore the piano and pianistic technique. One uninspired movement is based upon the ‘Old 100th’ psalm tune (see Example 3):

Ex. 3 Howgill junior: A Capriccio, sixth movement, bars 1–10

Other sections are more ‘mechanical’, such as the extract from the ‘Allegro’ in Example 4; similar devices appear habitually throughout his piano music.

Ex. 4 Howgill junior: A Capriccio, second movement, bar 19

Capriccios were not uncommon in Britain at this time. Published examples include those by Clementi, Pleyel, Thomas Cooke, Fredrich Kalkbrenner, Daniel Steibelt and Johann Baptist Cramer.

None of Howgill's orchestral works have survived. His Grand Symphony for an orchestra with parts for piano, strings and flutes was, according to the Monthly Magazine, ‘highly successful’.Footnote 161 They also held in high esteem his Overture to the Hero of Vittoria, which was written for a similar orchestration, but without piano.Footnote 162

Howgill junior wrote a considerable amount of church music. I have already mentioned the three organ duets that were performed between 1783 and 1785, but one such duet, dedicated to William Hamper, was published in 1807.Footnote 163 This work, which can be easily played on a piano, consists of two movements, a ‘Largo’ and a ‘Con Brio’.Footnote 164 Keyboard duets were rare at the time of publication, even though this genre can be traced back to the sixteenth century.Footnote 165 It is possible that Howgill junior may have known the two keyboard duets by Charles Rousseau Burney, published in 1781 and 1786.Footnote 166 A further duet by John Marsh, specifically written for organ, was published in 1783 along with two duets adapted from the works of Handel.Footnote 167 Of Howgill junior's published organ voluntaries, the earliest appeared in his collection of sacred music, An Original Anthem & Two Voluntaries. Footnote 168 These are again rather secular in style, and formed into suites with a strong pianistic feel. A pleasant minuet opens the second voluntary (see Example 5).

Ex. 5 Howgill junior: Voluntary II (1800), first movement, bars 1–15

Other movements, such the second of Voluntary II with its use of the ‘cornet’ stop, were clearly influenced by the eighteenth-century organ voluntary.Footnote 169

A further collection of ten voluntaries, now lost, was published in 1811. They were written for different seasons of the year and were criticized in the Monthly Magazine for their lack of distinguishing features.Footnote 170 Others, however, such as Edward Miller, praised them for their originality.Footnote 171 Howgill junior's final work was a collection of Four Voluntaries, all of which are cast in a similar mould to his earlier examples; several have opening movements influenced by the ‘cornet’ voluntary.Footnote 172

Perhaps the feature of most interest in Howgill junior's voluntaries is that they are written for an instrument with three manuals. Whether the Snetzler instrument at Whitehaven had three manuals is debatable. As we have already seen in the 1781 account of Howgill junior's performance on that instrument, there are references in the newspapers that indicate that this organ had three manuals. Howgill junior also described the instrument as having three in the prefatory material to his Four Voluntaries. Footnote 173 He gave the specification as:

The issue with Howgill junior's stop list is that both John Sperling and Alexander Buckingham independently recorded that the organ had two manuals.Footnote 174 A possible solution is that the swell was played on the choir, as it was on the Snetzler organ at St Margaret's Chapel, Bath.Footnote 175 Nevertheless, the Whitehaven instrument was thought of highly enough to be described in 1809 as ‘the best organ in the north of England, (Durham [Cathedral] only excepted)’.Footnote 176

Howgill junior composed a significant sacred vocal music, all of which must have been performed at Whitehaven. An anthem by him was sung at St Nicholas’ on Easter Day 1794; this may have been the anthem that he included in his 1800 collection. The Monthly Magazine said that this ‘anthem, though not without some traits of disuse in this species of composition, possesses many points that entitle it to our commendation.’Footnote 177 This work is quite typical of other anthems composed in the late eighteenth century, pleasing but not progressive and, as such, it is similar to those by Ebdon. The organ part, which is written out in full, is pianistic in style, which is unusual for its time.Footnote 178 The work includes several duets, a trio and a solo for tenor or bass. The fact that Howgill junior could write cathedral style anthems for use in a relatively small town church is unusual but not unprecedented, as anthems written for church use had already been published.Footnote 179 Nevertheless, few parish churches had organs at this time and most relied on an instrumental band to accompany the singing. A further sacred vocal work by Howgill junior, a trio setting of the ‘Third Chapter of the Wisdom of Solomon’, was included in his 1824 collection.

Howgill junior included 42 psalm tunes in his 1800 collection of sacred music.Footnote 180 Naturally, there are examples from Howgill junior's pen, but there are also tunes by Garth, James Nares, Greene, Croft, John Langshaw (the organist at Lancaster), Theodore Smith, Ignace Pleyel, and Dibdin, as well as two by William Howgill senior. Many of Howgill junior's own tunes were given local names, such as ‘Penrith’, ‘Appleby’, ‘Workington’ and ‘Wigton’. Others psalm tunes were adapted from the works of Avison, Geminiani and Handel.Footnote 181 A further set of six were included in his Four Voluntaries, all of which are more substantial than the earlier examples with sections for solo organ.Footnote 182

The Howgill family, despite their importance as provincial musicians, are hardly known today. Even in Whitehaven, few are aware of their town's distinguished musical heritage, nor how that place came to dominate the musical life of Cumberland in the second half of the eighteenth century. On a national level the Howgills are not of great importance, as the majority of them had little or no impact outside the north of England. William Howgill senior, as was typical of a provincial organist, promoted concerts and balls and provided music tuition in his adopted town. Rather sadly, he left few original compositions. Ann was also a respected organist, but she also had little impact beyond her immediate surroundings, and Matthew and Thomas appear to have had no interest in a musical career. William Howgill junior, through his publications, achieved a much wider fame, and a great deal of his music was favourably received in London. However, in spite of this approbation, he had no influence on the development of music in Britain during the early nineteenth century. An analysis of his surviving compositions, particularly his sonatas, reveals that he was aware of the latest developments in keyboard technique, a surprise given Whitehaven's isolation from London; these works also disclose that he was by no means equal as a composer to his London contemporaries. Some of his secular compositions do have merit, but far too much of his piano music consists of little more than a series of difficult and banal pianistic textures. His sacred music also has value, but makes no effort to advance the sacred style of that time. In spite of these deficiencies, it was through his published works that Howgill junior drew attention to himself and his home town of Whitehaven, a move that garnered him the deep respect and admiration of that town's inhabitants and secured himself a place, however small, in the history of music composition in Georgian Britain.

Appendix A: List of the known publications issued by William Howgill junior, with year of publication. (Unless otherwise stated, all appear to have been issued in London by Preston.)

Appendix B: Programmes for concerts organized by the Howgill family. All concerts, except those marked otherwise, were held at the Whitehaven Assembly Rooms. Original spellings are retained.