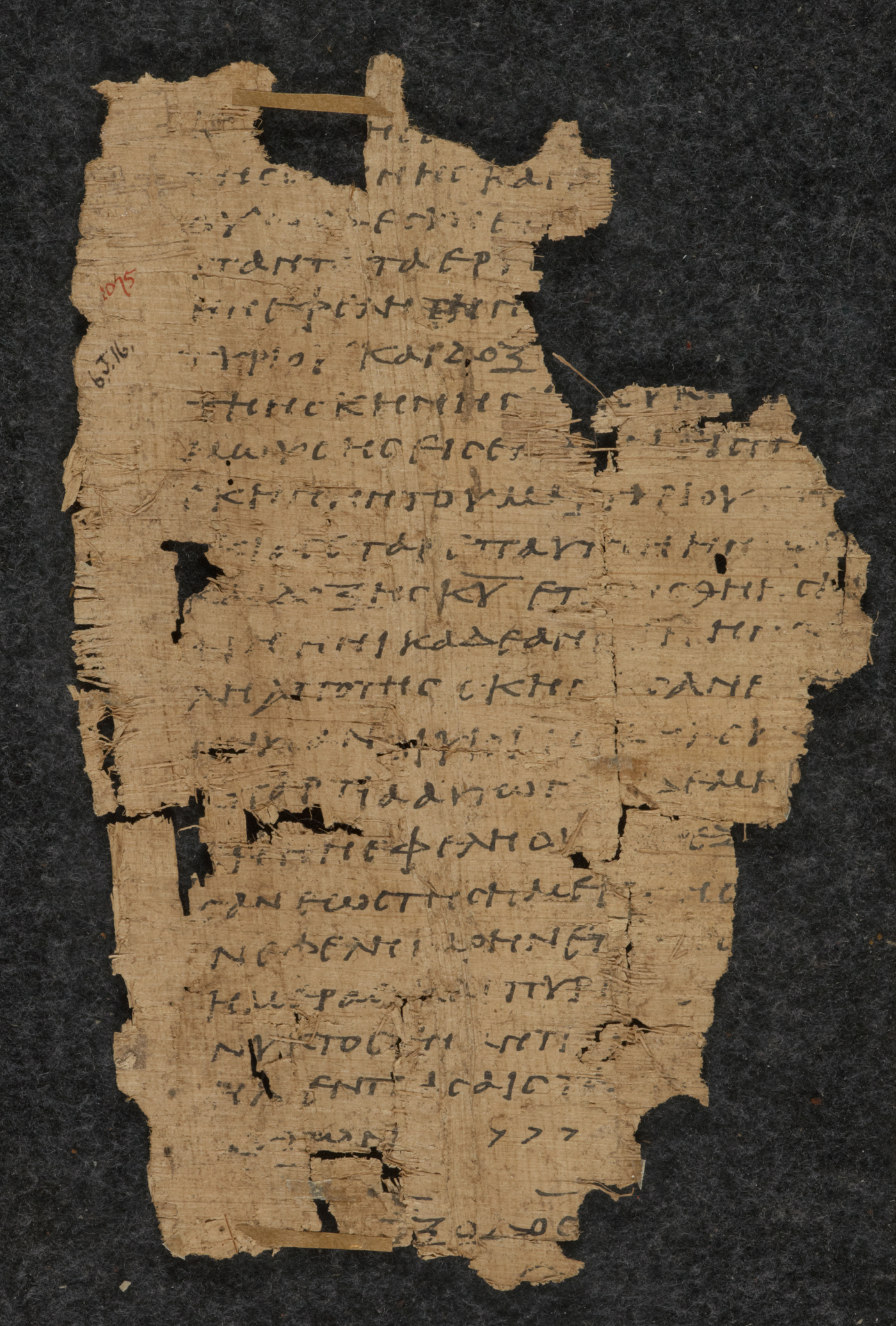

Housed in the British Library under the inventory number Pap. 2053 verso, P.Oxy. viii.1079 (![]() 18; LDAB 2786; TM 61636) was published by Arthur S. Hunt in 1911.Footnote 1 The fragment contains parts of Rev 1.4–7 on the side written against the fibres; in its current state, it measures 9.8 × 15.1 cm (B × H) (see Figure 1).Footnote 2

18; LDAB 2786; TM 61636) was published by Arthur S. Hunt in 1911.Footnote 1 The fragment contains parts of Rev 1.4–7 on the side written against the fibres; in its current state, it measures 9.8 × 15.1 cm (B × H) (see Figure 1).Footnote 2

Figure 1. British Library Pap. 2053 verso. ©British Library Board.

Hunt depicted the hand of P.Oxy. viii.1079 as ‘a clear, medium-sized cursive, upright and heavily formed’, tentatively assigning a date in the fourth century, without excluding the possibility of an earlier date.Footnote 3 And the earlier date was also suggested by Pasquale Orsini and Willy Clarysse, who compare the ‘cursive and informal documentary’ hand of P.Oxy. viii.1079 with that of PSI iii.199 (203 ce; TM 20027); they date the manuscript broadly to 200–300 ce.Footnote 4 Given that Hunt does not adduce any specific comparanda in support of his dating and that the attested script does indeed seem to sit better in the third century, it seems that Orsini and Clarysse's broader, though overall slightly earlier, dating is to be preferred. As regards the scribal practice, P.Oxy. viii.1079 betrays some minor traces of punctuation such as raised dots and vacant spaces; the scribe employed inorganic tremata, and effected one correction.Footnote 5 Despite the informality of the hand, the text was copied with care, showing no obvious errors or iotacisms. Although the manuscript's fragmentary state precludes definitive conclusions concerning its textual affinities, it appears to agree quite often with codices Alexandrinus and Ephraemi Rescriptus.Footnote 6

Although the fragmentary state of the papyrus precludes certainty concerning the extent in which it originally preserved text of the Apocalypse, it is most likely that the entire book was included: the extant passage is continuous rather than a selection, and neither textual nor physical features of the page are suggestive of an excerpt, amulet or a writing exercise. Yet the reconstruction of the manuscript's initial dimensions, as well as of its original contents, largely depends on what sort of book one envisages. We now turn to this problem.

1. A Reused Roll or a Miscellaneous Codex?

Ever since Hunt's 1911 edition, P.Oxy. viii.1079 was held to be a back side of a reused roll. This makes good sense, given that the side written along the fibres, published separately as P.Oxy. viii.1075 (LDAB 3477; TM 62314), contains ending of a different work (Ex 40.26–32, followed by the subscription) written by a different hand (see Figure 2).Footnote 7 Recently, however, this claim has been called into question by Brent Nongbri, who suggested that, rather than a ‘curious Christian roll’, perhaps we might be dealing with a ‘curious Christian codex’.Footnote 8 In what follows, I shall briefly review Nongbri's case and offer my own conclusions in turn.

Figure 2. British Library Pap. 2053 recto. ©British Library Board.

First of all, Nongbri notes that the format of the original page and column broadly fit with patterns observable in other contemporary papyrus codices, compatible with Turner's Group 8 – after all, what the extant fragment preserves, on both sides, is a single column of text along with a margin.Footnote 9 While, in general, Nongbri's observation is correct, it does not impress as an argument against the roll format. After all, single-column fragments of what once were more extensive rolls are not uncommon. Just from among the New Testament papyri, we might adduce P.IFAO ii.31 (![]() 98; LDAB 2776; TM 61626) – another fragment of Revelation which Nongbri cites along with other examples of early Christian rolls.Footnote 10 Compared to the de luxe literary rolls, the column of P.IFAO ii.31 is also quite wide and could be compared with some of the attested codex formats as well.Footnote 11 As regards the page dimensions, Nongbri himself acknowledges that the height of the reconstructed page of P.Oxy. viii.1079 is ‘common for both rolls and codices’.Footnote 12 And finally, the fact that the reconstructed page of an extant papyrus fragment fits with one of Turner's groups is perhaps unsurprising, considering that the range of Turner's groupings could cover just about any page dimensions.Footnote 13

98; LDAB 2776; TM 61626) – another fragment of Revelation which Nongbri cites along with other examples of early Christian rolls.Footnote 10 Compared to the de luxe literary rolls, the column of P.IFAO ii.31 is also quite wide and could be compared with some of the attested codex formats as well.Footnote 11 As regards the page dimensions, Nongbri himself acknowledges that the height of the reconstructed page of P.Oxy. viii.1079 is ‘common for both rolls and codices’.Footnote 12 And finally, the fact that the reconstructed page of an extant papyrus fragment fits with one of Turner's groups is perhaps unsurprising, considering that the range of Turner's groupings could cover just about any page dimensions.Footnote 13

Secondly, Nongbri reminds us that ‘we now have good evidence (unavailable to Hunt in 1911) for the existence of Christian codices with an eclectic mix of contents copied by different scribes’, hence P.Oxy. viii.1079 could potentially be regarded as yet another instance of this phenomenon.Footnote 14 Here Nongbri adduces the Bodmer Miscellaneous Codex, where the opposite side of the final leaf of the Apology of Phileas (P.Bodmer xx; LDAB 220465; TM 220465) begins with Psalm 33 (P.Bodmer ix) written in a different hand.Footnote 15 Again, it is not impossible that our papyrus is an instance of such a codicological arrangement, so that the book of Exodus and the Apocalypse may have been, for whatever reason, copied by different scribes within the same codex. It must be noted, however, that the Bodmer Composite codex would not seem to be the most fitting parallel in this particular case: it is a compilation of a wider array of comparatively shorter texts with a rather complex codicological make-up.Footnote 16 In our case, however, we would appear to have two substantial works copied consecutively. Rough calculations suggest that some 65 pages (32.5 leaves) would be needed for the text of Revelation alone. Using Ralphs’ edition as a rough guide, we would need a further 168 pages (84 leaves) for the preceding book of Exodus. Granting that miscellaneous papyrus codices of this size are not unheard of in the late third/early fourth century,Footnote 17 the odd combination of books,Footnote 18 coupled with some codicological difficulties that would have to have been involved,Footnote 19 renders the miscellaneous codex, in my mind at least, a less attractive hypothesis.Footnote 20

And finally, Nongbri observes that, in reused rolls, the writing on the back is often upside down relative to the writing on the front.Footnote 21 While it is difficult to falsify or substantiate this observation, given the lack of information provided in editiones principes (especially the early ones), papyrological experience nonetheless does seem to confirm that rotating the roll was the more usual procedure.Footnote 22 Even so, reused rolls beginning the same way up occur fairly regularly, of which Hunt is likely to have been well aware. It would seem that, in the end, a reused roll that was not rotated 180° might well appear a little less curious than a kind of composite codex that Nongbri envisages – particularly in view of the informality of the production reflected in the Revelation portion.

In support of the ‘traditional view’, we might also recall a recent counter-argument proposed by Peter van Minnen.Footnote 23 He observes that, if P.Oxy. viii.1079 was indeed a reused roll, ‘the text on the back of the roll would not have been written immediately following but long after the text on the front and one should be able to tell this from the writing on the back: the back of reused rolls is damaged from use, and writing on it is a struggle’.Footnote 24 If, on the other hand, we have a codex, Van Minnen posits that ‘the writing on the back should not show signs of struggle’.Footnote 25 With this in mind, he concludes that he has ‘no doubt that the editor was right’, and that P.Oxy. viii.1079 is written on the back of a roll.Footnote 26 Incidentally, Van Minnen's argument has been recently cited with approval by Juan Chapa,Footnote 27 who considers the front size of the roll to be of a Christian origin, as evidenced by the third-century date and the presence of a nomen sacrum.Footnote 28 Interestingly, Chapa there also draws attention to at least one further roll containing a Greek Old Testament passage (Gen 16.8–12) that is of possibly Christian origin, namely P.Oxy. ix.1166 (LDAB 3114; TM 61957).Footnote 29 If his analysis proves correct, we have a meaningful parallel to P.Oxy. viii.1075, the front side of our roll.

2. A Socio-Historical Postscript: The Social Setting(s) of a Reused Roll

In view of the foregoing remarks and in the absence of a more convincing case to the contrary, we should probably continue to count P.Oxy. viii.1079 among the rare instances of the early Christian use of the roll format. Either way, however, we are clearly dealing with a book betraying signs of informal production, even if a more precise social setting might seem difficult (if not impossible) to reconstruct. On the one hand, C. H. Roberts famously remarked that ‘any texts written on the back of a roll or sheet discarded as waste declare themselves to be private copies, a view at times borne out by the manner of writing’.Footnote 30 This line of reasoning has also been adopted by Thomas J. Kraus, who submits that ‘the two awkward texts grouped together’ in P.Oxy. viii.1079 suggest that ‘the fragment was definitely not used for public or liturgic use. It may have served the purpose of private reading or it just represents notes for certain purposes.’Footnote 31 Even so, I fail to see why a church community cannot have employed a reused manuscript for the purposes of communal worship – whatever form that communal worship may have taken. After all, even Roberts himself acknowledges: ‘Not all texts written on improvised material need have been private. It may have been a paper shortage or just poverty that led one church to economize.’Footnote 32 Indeed, in principle one cannot rule out the possibility that a reused roll – or even a miscellaneous codex, for that matter – may have been produced for and/or utilised in a church setting. We must not forget that our papyrus was most likely produced in the third century, when, no doubt, some churches at least would have been of quite modest means – hence, employing a reused copy in ‘public’ worship might have been a viable option. From the little that is known of the relevant socio-economic circumstances in third-century Egypt, it would seem that ‘private’ ownership of Christian books was in any case not a common occurrence.Footnote 33 The fundamental problem, perhaps, with the above-surveyed scenarios is the very nature of the ‘public/private’ binary that is on occasion used in descriptions of (especially early Christian) literary papyri.Footnote 34 Discussion of such matters, however, must be reserved for another venue. For now, we should content ourselves with a conclusion that, whatever the social setting one might envisage, such historical guesswork is on firmer ground in presuming that P.Oxy. viii.1079 was a reused early Christian bookroll.