1. Introduction

English scholarship on the Christian apocrypha had a much slower start than that on the European continent. The scattered publication of early editions in the sixteenth century came out of the printing centres of Basle and Cologne; these were assembled, refined and expanded by Johann Albert Fabricius in his landmark collection Codex Apocryphus Novi Testamenti, published in three volumes in 1703 and 1719.Footnote 1 It is Fabricius’ editions that served as the basis for the first printed compendium of apocryphal texts in English translation by Jeremiah Jones in 1726, assembled as support for his arguments in A New and Full Method of Settling the Canonical Authority of the New Testament.Footnote 2 But early modern scholarship was not confined to print. Hand-copied books continued to appear alongside printed ones for several centuries after Gutenberg, and indeed longer still outside Europe. These books had much smaller reach than books in print, and many of them no longer survive. But two handwritten copies of an early collection of apocrypha in English, neglected and largely forgotten among the holdings of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (University of Toronto) and the Cambridge University Library, reveal a missing chapter in the history of English scholarship on the Christian apocrypha. The two copies, both entitled Opera Evangelica (hereafter OE) but with many significant material and textual differences between them, together attest to a work of late seventeenth- or early eighteenth-century scholarship created after the early editions, without apparent knowledge of Fabricius, and before Jones. The work has gone largely unnoticed in previous scholarship; even subsequent English compilers – such as Jones, M. R. James and J. K. Elliott – appear not to have been aware of it. So it may not have circulated outside a very small group of interested readers. Nevertheless, it brings attention to an area of apocrypha research that has not previously been explored but one that is particularly appropriate for a field that focuses on texts that were composed and circulated outside conventional channels of production and dissemination.

2. Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, MSS 01202

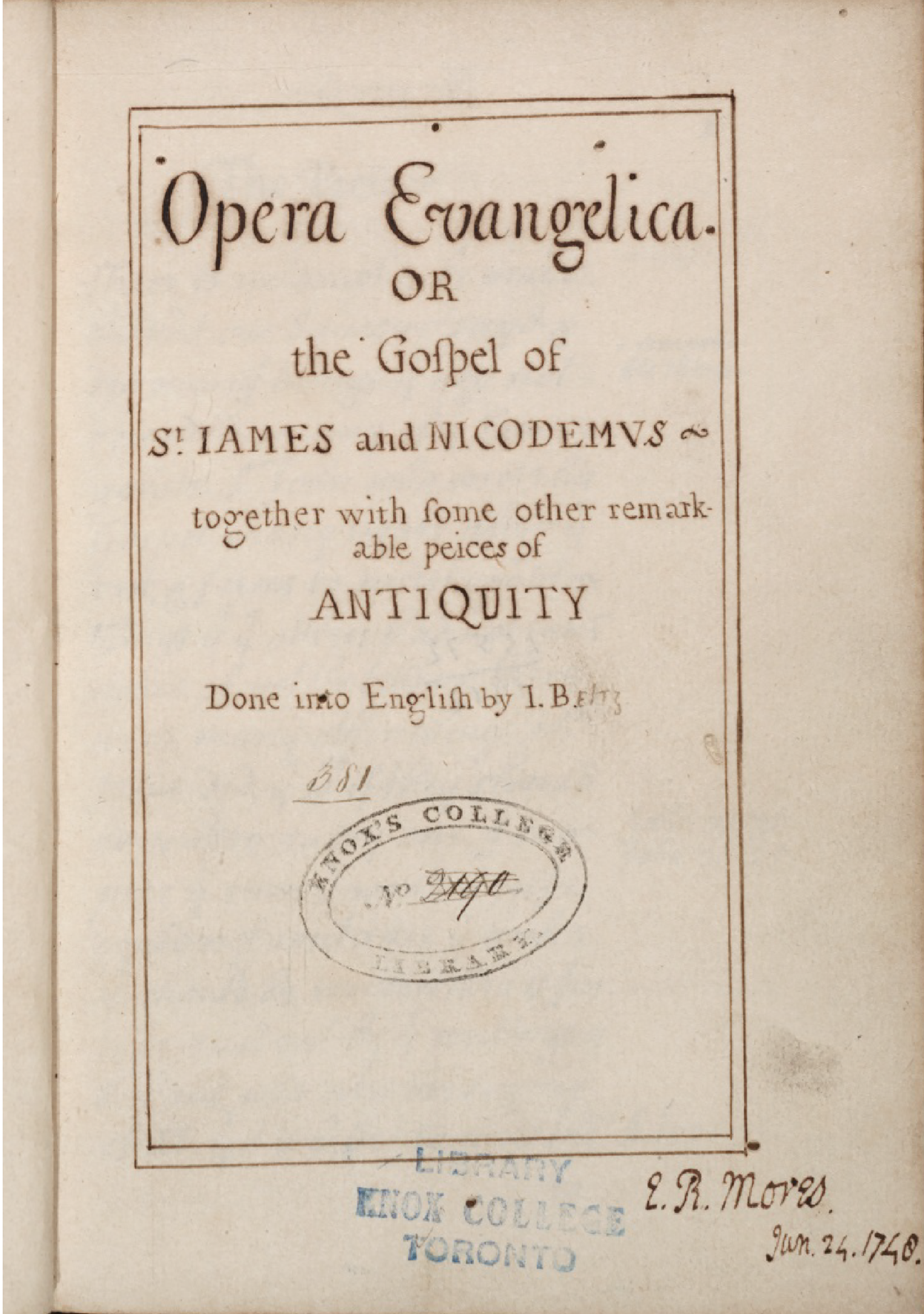

The Toronto manuscript (T) bears the title Opera Evangelica: Or the Gospel of St. James and Nicodemus, together with Some Other Remarkable Pieces of Antiquity and claims to have been ‘Done into English by I. B.’ (Fig. 1).Footnote 3 Unlike its counterpart in Cambridge (C), T has a fairly simple structure (to be discussed in greater detail below). English translations of a selection of apocryphal Christian works occupy the balance of the pages, preceded by a lengthy Preface justifying the existence of the volume while also providing historical and theological comments on Christian apocrypha broadly and on the selected works for translation more specifically.

Figure 1. Title page, Opera Evangelica (Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, MSS 01202)

The book is a small codex, measuring 18.5 × 7 cm, with thirty-one regular gatherings for a total of 248 pages, although apparently in a non-standard format.Footnote 4 And it is a fair copy, inscribed with care and precision, though with some inconsistencies and corrections.Footnote 5 The copyist was fond of abbreviations, especially for ‘the’ (= ye), ‘that’ (= yt) and ‘which’ (= wch), while favouring the letter I instead of J (e.g. Iesus). The copyist also abbreviated some names, such as ‘Clem:Alex:’ for Clemens Alexandrinus (T, p. xix; cf. C, p. 9). But there remain instances of plene spelling of these words, sometimes in the same sentence as an abbreviation, along with the occasional use of the letter J.Footnote 6 The vast majority of the thirty-eight corrections occurred during the initial inscription: interlinear additions of a letter, word or phrase signalled by a caret; crossing out of a word that was duplicated or erroneously copied; or writing over a word that was misspelled. Six other corrections were made at a later date with a different ink, but still by the same hand, modifying spelling or rewriting a word that had faded.

The copyist, who inscribed the entire volume, took great pains to imitate the appearance of a printed book, evident especially in the title page with its simple border and script that resembles Roman typeface. Throughout the rest of the book, each page has consistent spacing between lines, page numbers, running heads and catchwords for transitions from one page to the next.Footnote 7 A light brown, reverse leather binding was most likely added after the volume was copied. The end papers differ from those that make up the rest of the book and escaped the appetite of worms, who penetrated through some of the external, now-yellowed pages. It is likewise hard to imagine that the careful copyist could have inscribed the lines of each verso page so close to the gutter. Some time passed between the purchase of quires of paper, probably at a stationer's shop, and its inscription by an unknown copyist.

Watermarks on the paper of the manuscript indicate that the sheets were manufactured in one of the paper mills in Angoulême (or Angoumois), France, owned by the Huguenot Abraham Janssen. According to W. A. Churchill, ‘Arms of London’ watermarks – the type that is found on the leaves of T – appeared only in 1694.Footnote 8 This paper was probably imported to England by Abraham's son Theodore, who had emigrated to London in 1683 and by 1685 had established a successful but short-lived importing business.Footnote 9 T, therefore, could not have been copied before 1694.Footnote 10

Although it is possible to establish a terminus post quem for this particular artefact, it is less clear where the book stands in a history of transmission. It may well have been inscribed by its author, identified on the title page simply as ‘I. B.’, but the quality of its hand and textual layout suggests that this copy was based on a draft or some other copy, produced not long before the creation of the Toronto volume. In any case, from the paper's production in France, its inscription and binding in England, to its eventual deposit in Toronto, this copy of OE passed through the hands of a number of owners and readers. Some evidence for this chain of ownership is found in an inscription on the lower right-hand corner of the title page providing the name of an early owner of the volume, E. R. Mores, with the date of 24 January 1748 (see Fig. 1). This E. R., or Edward Rowe, Mores was an Oxford-educated antiquarian and typography enthusiast. Given that Mores was born on 13 January 1730, he would have received this book just before his eighteenth birthday during the second year of his studies at Queen's College.Footnote 11 Mores would go on to become a noted antiquarian who published editions of ancient works and corrected existing ones. He was also interested in typography, having possessed a collection of stamps and type, and composed a Dissertation upon English Typographical Founders and Founderies based on his collection.Footnote 12 Although OE was only one small volume within what was a fairly extensive personal library, its mimicry of the typographic book and translations of ancient works would surely have satisfied Mores’ budding antiquarian and typographic interests. Following his untimely death in 1778, Mores’ copy of OE was auctioned off in London by the well-known bookseller Samuel Paterson to an unknown buyer for three shillings.Footnote 13

Almost nothing is known of the subsequent life of this copy of OE following Mores’ death. Some rough scribbles in pencil on one of the endpapers indicate that the book was ‘Bot at’ a sale for 7 shillings and 6 pence, a considerable increase from its going price in 1778 (Fig. 2). Someone else inscribed ‘Nicholas & Al’ in brown ink on the same page. Eventually, the copy traversed the Atlantic and was acquired by Knox College in Toronto at some point in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Numerous stamps from the Knox College library adorn the endpaper, the recto of the first page, and the title page, with the latter inscribed with the call number 2190. Further, a librarian of Knox College appears to have had some insight into the identity of I. B. In a practice characteristic of early Knox librarians, someone wrote ‘Bel’ in the top left-hand corner on the endpaper, which corresponds with the inscription ‘eltz’ added to the ‘B’ on the title page. Unfortunately, this I. Beltz or J. Beltz remains unknown.

Figure 2. Endpaper, Opera Evangelica (Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, MSS 01202)

Whereas there is no record of the circumstances of T's accession into the Knox collection, there were a number of opportunities for this to have happened. As Brian Fraser reports, in the early 1840s, several influential leaders at the University of Edinburgh made solicitations throughout Scotland for funds and books for a theological college associated with the Free Church of Scotland, which would soon become Knox. The effort resulted in the assemblage of approximately 2,000 volumes that came to Upper Canada with one of Knox's earliest instructors, Robert Burns.Footnote 14 It seems likely that T made its transatlantic voyage among those 2,000 volumes. Over the next fifty years, however, the College's collection swelled to some 12,000 volumes, thanks in part to donations by local clergy.Footnote 15 It is entirely possible that T entered the collection in one of these periodic donations. At the very least, we know that T must have entered the Knox collection sometime after 1825. A nineteenth-century hand copied on the flyleaf (Fig. 3) two verbatim excerpts about the Protevangelium of James and the Gospel of Nicodemus from a copy of the fourth corrected edition of Thomas Hartwell Horne's An Introduction to the Critical Study of the Holy Scriptures, also held in the Knox library (Knox 01292).Footnote 16 Although it was published in 1825, it unfortunately remains unclear when the Horne volume came to Knox. However, Horne's Introduction was being used as a textbook in classes on biblical criticism by the mid 1850s.Footnote 17 More significantly, however, the inscription demonstrates that the volume was experiencing at least some sort of active engagement by theological students over a hundred years after its initial inscription. In 1995, approximately 5,000 volumes of Knox's historic collection were placed on permanent loan to the Fisher Library, including both OE and Horne's Introduction.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Flyleaf verso, Opera Evangelica (Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, MSS 01202)

Two large sections make up the entirety of the Toronto OE: a Preface spanning seventy pages and the English translations occupying an additional 156. The Preface is a fine example of early eighteenth-century erudition, steeped in and liberally citing current scholarship on Christian antiquity. Its opening line clearly establishes an important premise that justifies the collection of translations that follow: ‘There is no doubt to be made but that our Sauiour sayd & did many things yt are not recorded, in any of ye Evangelists’ (p. i). This declaration is followed by references to John 20.20 and 21.25 – claims by the evangelist that his book alone cannot contain the deeds and sayings of Christ. In the pages that follow, the author narrates the early history of the Christian church, structured according to an agonistic contest between orthodoxy and heresy – the former has reliably preserved the stories and teachings of Jesus while the latter fabricated them with falsely attributed books. The author also contributes rich scholarly and historical discussion of eight out of the nine works and extracts included in the volume, and concludes with an apologia for making vernacular translations of non-canonical texts available to a reading public.

The collection is made up of a cluster of non-canonical works related to Christ (see Table 1). The Protevangelium of James treats the birth of Jesus while the lengthy Gospel of Nicodemus covers Jesus’ death and descent into the underworld. Physical descriptions of Jesus appear in the Epistle of Lentulus and in an excerpt from the thirteenth-century ecclesiastical historian Nicephorus Callistus (Eccl. hist. 1.40). Two other works are ostensibly non-Christian sources about Christ: the Epistle of Pilate to Claudius (here addressed to Tiberius) and the Testimonium Flavianum (Josephus, Ant. 18.3.3). Three remaining works appear to be chosen at random: the Epistle of Pseudo-Dionysius to Polycarp; one of the spurious Ignatian epistles to John; and the pseudo-Pauline Epistle to the Laodiceans.

Table 1. Contents of the Toronto Manuscript

3. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Royal Library Ii.1.8

The Cambridge manuscript is less refined than its Toronto counterpart, appearing less like a typographic imitation and more like a personal notebook.Footnote 19 Certainly some portions are more formal than others, with the preface and text of the first work (Protevangelium of James) written in a careful block script, with running heads and catchwords; the Gospel of Nicodemus then follows in cursive, with running heads but no catchwords; the remaining works vary in style. Abbreviations (ye, yt, wch) are present but far less common than in T. The cataloguer describes it as a ‘small quarto’, measuring 30 × 16.5 cm and comprising 184 pages. Its binding is typical of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with brown boards and gold leaf in the Cambridge panel style.Footnote 20 The writing area is surrounded by a red border, with occasional additional horizontal lines. A flower image decorates the title page, which, unlike that of T, bears no author's name. The introduction is given a subtitle lacking in T: ‘a preliminary discourse concerning the following Treatises together with the Latine Copy from which they were translated’. The frontispiece (Fig. 4) features the Oxford motto; the page has become detached from the manuscript, but it was probably originally bound into the book. Both T and C, therefore, have connections to Oxford.

Figure 4. Frontispiece, Opera Evangelica (Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Royal Library Ii.l.8)

The book plate on the reverse of the title page (Fig. 5) was created in 1715 by John Pine for the collection of John Moore (1646–1714), Bishop of Norwich (1691–1707) and of Ely (1707–14).Footnote 21 After Moore's death, King George I bought the collection and donated it to the University of Cambridge. The collection, known as the Royal Library, contained almost 29,000 books and 1,790 manuscripts. George's donation tripled the size of the Cambridge library.Footnote 22 It is not known when the book was purchased by Moore, nor to which prior collection it once belonged. A catalogue of Moore's library was published by Edward Bernhard in 1697/8 but it does not contain OE;Footnote 23 acquisitions by Moore made after Bernhard's catalogue can be found in a handwritten list made in 1700 by Thomas Tanner (catalogued as MS Oo.7.502), but this too lacks mention of the book; presumably it was acquired by Moore sometime between 1700 and 1714.Footnote 24 The title page bears the expunged inscription ‘E libris Thomae Davies’ (Fig. 6), who the Cambridge cataloguer thought ‘may possibly have been the translator’.Footnote 25 This Davies may be a vicar of Syston in Leicestershire known to Moore; the collector was present at one of Davies’ sermons in Norwich Cathedral in August 1699, and a handwritten copy of the same sermon is in Moore's collection (MS Ff.4.20) – presented, like OE, ‘in imitation of print’, and with a dedication to Moore.Footnote 26 Perhaps Davies gave OE to Moore as a gift, or in exchange for another volume. Davies also prepared a catalogue of Moore's manuscripts in 1697, perhaps to be passed along to Bernhard for his Catalogi, and continued to act for Moore until at least 1709.Footnote 27 Another possibility for the identity of Davies is a former bookseller (1631–80) who was mayor of London from 1676 to 1677.Footnote 28

Figure 5. Book plate, reverse of title page, Opera Evangelica (Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Royal Library Ii.l.8)

Figure 6. Title page, Opera Evangelica (Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Royal Library Ii.l.8)

C is comprised of as many as seven different hands, or at least styles. Curiously, the translation of the Gospel of Nicodemus breaks off on p. 72 and then continues in the same hand on p. 141; notes on both pages guide the reader over the break (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Marginal notes for the Gospel of Nicodemus, Opera Evangelica (Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Royal Library Ii.l.8, pp. 72 and 141)

The English translations in the collection follow the order of T up to the Ignatian epistle to John (see Table 2); the following text in T, the Epistle to the Laodiceans, is missing, despite it being included in C's discussion of the manuscript's contents in the Preface (p. 22). As the title page promises, a number of works and excerpts appear in Latin. For the most part these correspond to the English translations except that C lacks the Latin text of the epistles of Ignatius, Ps.-Dionysius and Nicephorus Callistus, Eccl. hist. 1.40, and adds Nicephorus Callistus, Eccl. hist. 2.8 and the Abgar Correspondence. The order and selection of the Latin texts is owed to their source: Johannes Herold's Orthodoxographa, published in 1555.Footnote 29 Despite the claims of the manuscript, Herold's texts may not be ‘the Latine Copy from which [the texts] were translated’, or at least not all of the translations – the added texts would indicate otherwise as do the differences between the Latin text of Gos. Nic. (which terminates at 15.1 in C) and its English translation (which runs to its conclusion at ch. 29). As it turns out, at least four of the texts appear to have been translated from an edition of the Magdeburg Centuries (see below).

Table 2. Contents of the Cambridge Manuscript

The Preface of C differs in small and large ways from T. The small differences amount to a reduction of abbreviations and the occasional substitution of single words (e.g. ‘who’ for ‘that’, p. 3, line 3). The large differences result in a shortening of the Preface by roughly 20 per cent (see Table 3). One of these omissions, running thirteen lines in T, is observable on p. 8 of C (T, pp. xvi–xvii), but most of them occur after p. 16 (the portion of the Preface that describes the texts in the volume). At least two of these omissions are due to parablepsis (eye skip) – on p. 20 the eye of the Cambridge copyist seems to have slipped from ‘answers that’ in T, p. lii line 7 to the same words at line 13, and on p. 24 C with the two occurrences of ‘no harm’ (T, p. lxix, line 15; p. lxx, line 4). In two cases the copyist indicates missing material with ‘& c.’ (p. 23). Note also that two brief portions of text from T are placed in the margin in C (pp. 18 and 24).

Table 3. Omissions of T in C

T also has some omissions, though in two cases the missing material is placed above the line (see Table 4).

Table 4. Omissions of C in T

Finally, at several places the text of both manuscripts differs significantly (see Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Comparisons between Toronto and Cambridge volumes of Opera Evangelica (Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, MSS 01202 & Cambridge, University of Cambridge, Royal Library Ii.l.8)

8.1. C, p. 18.8–9 vs T, p. xlvi.5–7

8.2. C, p. 20.19–20 vs T., p. liii.3–5

8.3. C, p. 23.20–4 vs T, p. lxvii.4–8

The Preface in C has far fewer marginal glosses and citations than C – pp. 1–15 have only one, but on pp. 16–23 they are plentiful, though they do not always agree in content with those in T. The English translations have a number of minor variations (primarily spelling, but also occasional small omissions). All of these differences suggest two possibilities about the relationship between the manuscripts: C is an imperfect copy of T, or both derive from a common exemplar that has yet to be discovered. Certainly T cannot derive from C, given the cases of parablepsis and the omission of the Epistle to the Laodiceans.

As for the translations, the majority of the differences between the manuscripts are minimal, amounting mostly to synonyms – e.g. ‘said’ (T) for ‘answered’ (C; at Prot. Jas. 2.3) – or spelling variations – e.g. ‘go’ (T) for ‘goe’ (C; at Prot. Jas. 14.1). More substantially, T lacks three small phrases from the Protevangelium of James that are found in C and Postel's Latin text: ‘and prayed for her’ (at Prot. Jas. 8.3), ‘from Bethlehem’ (18.1) and ‘from the top to the bottom’ (24.3). In the Gospel of Nicodemus, C lacks the phrase ‘but thou being a Grecian how understand thou Hebrew?’ (at Gos. Nic. 1.4; C, p. 40) and T lacks a large portion of Gos. Nic. 2.3–4 (corresponding to C, pp. 42.9–43.9); in addition, a marginal reference in T on p. 90 (‘And the scripture teacheth that the prophet Elias was taken up into heaven’) seems to be a correction by the T copyist (the material is found in Gos. Nic. 15.1, but not in C). The Toronto volume has several other marginalia not present in C: at Gos Nic. 17.3, the note ‘date nobis singulos thomos terrae’ (T, p. 103) gives the Latin textFootnote 31 for the problematic reading ‘pieces of earth’ (probably meaning ‘sheets of paper’); in the Epistle of Lentulus appended to the phrase ‘man of a tall stature’ is ‘compare the copies in the orthodoxographa and Magdeburg together and you find this to be the truest sense’ (T, p. 144), and to ‘his brow is smooth’ is ‘frontem planam et serenissimam: chearfull’ (T, p. 145); in Nicephorus, Eccl. hist. 1.40 to the phrase ‘his eyes were lovely’ is appended ‘oculos faluos qui nominantur Charopi. his eyes were a fallow colour, such as are called pleasant’ (T, p. 146), and to ‘his look was still humble’ is ‘ne prorsus erectus incederet: this is certainly the meaning of it’ (T, p. 147); and in the Epistle of Dionysius to Polycarp to the phrase ‘seeing it was not the time of the conjunction’ is appended ‘that it was not the new moon’. C has only one marginal reference not found in T: in the text of Ignatius’ Epistle to John, to the phrase ‘and way of speaking’ is appended ‘modo conversationis’ (T, p. 79). And three titles are presented differently: in T, ‘our Lord and Saviour Jesus’ is lacking from the title of ‘The Gospel of Nicodemus concerning the Passion and Resurrection of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ’; to the title ‘The account that Flavius Iosephus the Iew gives of our Saviour Christ’ T adds ‘in his Antiquities of the Iewes. Lib: xviii. Cap: 4’; and whereas T has ‘Out of the letter to the wise Polycarp’, C has ‘Out of the Letter of Dionysius to Polycarp’ and then a second title: ‘Dionysius to the wise Polycarp & c.’

While no trace of T has been found in previous scholarship, C has not gone entirely unnoticed. Christ's Eternal Gospel by O. Preston Robinson and Christine Robinson, published in 1976, contains an English translation from the Epistle of Lentulus that is exactly the same as the one found in OE.Footnote 32 The authors say that it was found on pp. 73–4 (the precise location in C) in an ‘ancient manuscript’ in the Cambridge University Library – note also that they state that such manuscripts ‘are obviously very old and probably date back to the early part of the Christian era’.Footnote 33 The statement is clearly misleading, if not intentionally false. This particular manuscript is not ‘ancient’, though the authors are correct that some apocrypha manuscripts are indeed ‘very old’.

4. The Contents and Sources of the Collection

The assortment of works found in OE is typical of the approach to publishing apocrypha in the early modern period, when scholars would attach whatever texts had become available to their studies of canonical and patristic literature, typically at the end – as for example in Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples's 1512 edition of Paul's epistles (which included the Epistle to the Laodiceans, the Epistles of Paul and Seneca and the martyrdoms of Paul and Peter by P.-Linus), Michael Neander's appendix to his Latin translation of Luther's Short Catechism (in three editions of varying contents, 1557, 1564 and 1567), Johannes Herold's Orthodoxographa (1555) and its expansion by Johann Grynaeus in his Monumenta sanctorum Patrum orthodoxographa (1569).Footnote 34 Although the OE author engages numerous secondary sources and demonstrates familiarity with editions of ancient Christian works, they are not fully transparent concerning the sources for the translations. Nevertheless, the translations are distinctly different from those made by Jeremiah Jones, who compiled the first printed collection of apocrypha in English in 1726. Most likely the compiler has made their own translations from the published works, and probably all from Latin. A few potential sources are mentioned in the Preface, including Guillaume Postel's discovery and publication of the Protevangelium in 1552 (p. xli).Footnote 35 In a section found only in the Preface of the Toronto volume, the author references the so-called Magdeburg Centuries – an ecclesiastical history running to 1298, published in Magdeburg from 1559 to 1574 – as the source of the Epistle of Lentulus (pp. xlviii–xlvix), but it appears to serve as the source for a cluster of four of the translated works.Footnote 36 In OE's discussion of the Epistle of Pilate to Claudius, the author notes that it is ‘usually printed wth ye former treaties, & is of a latter date, this letter is to be found in Fol: 66. in the edition I now use’, with a marginal reference reading ‘Edit:Basil:1544’ (T, p. lx). The Magdeburg Centuries does indeed include the Testimonium Flavianum, the Epistle of Pilate to Claudius, the Epistle of Lentulus and the excerpt from Nicephorus, Eccl. hist. 1.40 in sequence, albeit one that the translator slightly rearranged.Footnote 37 It would certainly have been convenient for the author to translate all four of these works from the same source, and this is precisely what the copyist of the Cambridge volume did with Orthodoxographa. In addition, citations of the Latin text of the Epistle of Lentulus and Nicephorus placed in the margin near their translations (T, pp. 145–7) align with the text of the Centuries and differ from other available editions, which secures the Centuries as the source for at least those two works. No source is given for the Gospel of Nicodemus, though it was printed in Latin incunabula as early as 1473 and frequently thereafter.Footnote 38 The origins of the final three epistles remain a mystery, though they were widely available; the 1498 edition of Ps.-Dionysius prepared by Lefèvre even includes the Ps.-Ignatian epistles.Footnote 39 Given that the translator appears to have favoured texts found in the same printed edition, it is highly possible that Lefèvre's edition was indeed the source.

5. Authorship and Dating

The identity of the composer of OE is a tantalising mystery. Both the Toronto and Cambridge volumes include the phrase ‘Done into English’ on the title page, with Toronto adding by ‘I. B.’ Internal evidence provides further clues, although none of them conclusive. A parenthetical defence of manuscripts, scholarship and printing in England (T, pp. xxxii–xxxv; cf. C, pp. 12–14) implies that the author is English, and elsewhere the author calls the famous Bishop of Lincoln Robert Grosthead (Grosseteste) ‘our countryman’ (T, p. lxvii; cf. ‘our Countrey-man’ in C, p. 24). Likewise, the mention of manuscripts of Ignatius ‘in our own library in Oxõn’ may locate the author more specifically in Oxford (T, p. xxxii; cf. C, p. 13). Unfortunately, the combination of initials, even guided by the later Knox librarian, and the author's implied fellowship in an Oxford College does little to establish their identity.

There is much more to be said, however, concerning the dating of the work. Though the genealogical relationship between the two manuscripts is difficult to ascertain precisely, it is probable that neither was the apograph of the other. Even if it is possible to determine a fairly specific date for each manuscript, the age of the original composition of OE remains less clear. This result is disappointing from a text-critical standpoint, but the temporal difference between the composition of the work and the copying of both the Toronto and Cambridge volumes is small enough to have little bearing on when to locate these volumes in a historical context.

In addition to the age of the paper of T, established from the ‘Arms of London’ watermark, the clearest evidence for dating the manuscript derives from a series of marginal citations. The author frequently cites the opinions of contemporary scholarship on the history of Christianity in the body of the text, sometimes accompanied by marginal reference to the specific work and page number. The author also quotes ancient writers, occasionally with excerpts in the original language in the margin or with a reference to the edition that was used. Comparison between the quotations inscribed in the margins and those printed in the cited editions give further temporal coordinates in which to place this book, thus providing a definite terminus post quem as well as a suggestion towards a terminus ante quem. One of the challenges of this method of dating, however, concerns the fact that T contains many more marginal citations than C, including one citation that proves to be the most instructive.

The author cites widely and deeply from scholarly writings and editions of ancient works. But there is a definite cluster of citations from the late-seventeenth century – from Thomas Comber's Christianity No Enthusiasm published in London in 1678 (T, p. lxv) to Thomas Dodwell's Dissertationes in Irenaeum printed in Oxford in 1689 (T, pp. xx, xxxvii).Footnote 40 Whereas several of the works in this range appeared in a single edition, others were published in multiple editions. Richard Baxter's Paraphrase of the New Testament (T, p. ii), for example, was printed in London in 1685, with a second edition in 1695.Footnote 41 The author seems to have made efforts to use the most recent edition of a given work, referring in one instance to a line in book 6 of Clement of Alexandria's Stromata, which is ‘in all the editions … I have seen’, including the ‘newest edition I now have printed at Colle in 1688’ (T, p. xix). This is, in fact, a reference to Friderico Syllburgio's edition of Clement, cited also in the margin of the previous page.Footnote 42

The most crucial evidence for dating OE, at least in its Toronto form, comes from the citation in T (but lacking in C) of Irenaeus, Haer. 1.17 in Greek: ἀμύθητον πλῆθος ἀποκρύφων καὶ νόθων γραφῶν (‘an unspeakably great number of apocryphal and spurious writings’, T, p. xxvii) (Fig. 9). Irenaeus was primarily known from a Latin version, represented especially in the editio princeps of Erasmus in 1526.Footnote 43 But towards the end of the sixteenth century, other Humanists began extracting Greek fragments, mainly from Epiphanius of Salamis, and including these witnesses in their editions. François Feuardent introduced Greek into his first edition of 1576, but not this particular citation. His second of 1596 (and its reprints) includes in a note at the bottom of the page only the phrase ἀποκρύφων καὶ νόθων γραφῶν and omits ἀμύθητον πλῆθος.Footnote 44 It was not until Joannes Grabe printed an edition of Irenaeus in Oxford in 1702 with the Latin text and Greek text in parallel columns that the Greek text of Haer. 1.17 became available.Footnote 45 Other Greek editions followed. Renati Massuet, for example, printed the Greek text in Paris in 1710. This edition, however, introduces a new division of chapters (now in common use). Whereas ἀμύθητον πλῆθος ἀποκρύφων καὶ νόθων γραφῶν appeared as Haer. 1.17 in Grabe, it appeared as 1.20 in Massuet.Footnote 46 It seems most likely, then, that the phrase was copied into the margin of the Toronto OE in 1702 at the earliest and 1710 at the latest, before Massuet's edition was printed and circulated.

Figure 9. Page with citation of Irenaeus, Haer. 1.17, Opera Evangelica, p. xxvii (Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, MSS 01202)

6. Opera Evangelica and the History of the Study of Christian Apocrypha

OE, we have argued, was composed in Oxford around the turn of the eighteenth century, with at least two copies produced before 1710 (T) and 1715 (C). This date range locates the production and dissemination of the work at a crucial moment in early modern scholarship, especially English, on Christian apocrypha. In addition to the various earlier sources, such as the Magdeburg Centuries, that the author used for the translations, the turn of the eighteenth century saw the publication of significant collections of Christian apocrypha, most notably Fabricius’ Codex Apocryphus Novi Testamenti in 1703 and 1719. But whereas this continental anthology presented its numerous apocryphal works and fragments in Greek and Latin, several English scholars were creating translations of the apocrypha in their vernacular.

One of the earliest hints of this movement can be attributed to John Toland, perhaps best known for his controversial Nazarenus eventually printed in English in 1718.Footnote 47 Nine years earlier, however, Toland had published a catalogue of apocrypha with titles in English that spanned fifty printed pages, a catalogue that he would later expand upon.Footnote 48 The catalogue itself is embedded in his book Amyntor; Or, a Defense of Milton's Life, in which Toland recounts an accusation made before the British House of Commons by the cleric Ofspring Blackhall: Toland was ‘shameless and impudent enough … publickly to affront our holy Religion’, by casting doubt on the authenticity of ‘several Pieces under the Name of Christ and his Apostles’ (emphasis original). In Blackhall's view, these several pieces ‘must mean those now received by the whole Christian Church’.Footnote 49 Toland thus took the opportunity in Amyntor to clarify that he did not, in fact, ‘mean the books of the New Testament’, and used this catalogue to show how many writings were written in the name of Jesus, the apostles and other early Christian figures.Footnote 50

Although his translation went no further than titles, Toland's ‘Catalogue’ and the controversy in which it was embedded demonstrate that the publicising of apocryphal works in England, especially in the vernacular, could be a matter of serious concern. Toland may not have been entirely ingenuous with the claim that his ‘Catalogue’ had no bearing on the books of the New Testament.Footnote 51 As Justin Champion has argued, Toland was a master of scholarly mimicry and parody, and often sought to provoke controversy in the way he marshalled and exposed existing scholarship and scholarly forms.Footnote 52 His ‘Catalogue’ indeed revealed what was at stake in the admission of forged apostolic writings and the vernacularisation of apocryphal works when canonical boundaries could be viewed as tantamount to the integrity of Christianity itself, policed by Christian clergy in a decidedly political sphere.

Views on the value and contribution of the apocrypha, however, varied among their translators. William Whiston, the famous mathematician, theologian and translator of Josephus (writing ca 1706–50), saw in many apocryphal works, most notably the Apostolic Constitutions, a window into early, authentic Christian doctrine and polity that had been otherwise obscured by Athanasian-inflected orthodoxy. The Trinitarian theology of contemporary English Christianity as it followed the trajectory set by Athanasius, he argued, could be reversed through a return to ‘primitive’ forms of Christian dogma.Footnote 53 Despite these assertions, Whiston does not appear to have held particular animosity towards the 27-book New Testament; rather, he sought to rehabilitate the term ‘apocrypha’ and introduce English publics to a wider array of works from earliest Christianity. Whiston's introductions and translations of the Constitutions and other works in his two-volume A Collection of Authentick Records bear this out.Footnote 54

Jeremiah Jones, by contrast, offered his historical account of Christian apocrypha and their translations as an essential component of his larger project: to articulate the boundaries of the New Testament canon and argue for its authority – a strategy in sharp contrast to the work of Toland. Jones’ argument was rigorously antiquarian, and constituted a somewhat parsimonious account of ecclesiastical history. This history established the emergence of the New Testament canon as an early and widely agreed upon body of texts, but one that emerged alongside the composition of other works, though apostolic in name only. Jones saw apocryphal writing as the purview of heretics, though some certainly ‘were composed by honest and pious men’.Footnote 55 The bulk of Jones’ effort, therefore, is erudite discussion of these works, cataloguing ancient testimony alongside the learned opinions of other modern European intellectuals. Only occasionally does he actually include translations of the works themselves, such as in his discussion of the apocryphal correspondence of Paul and the Corinthians; its brevity and then-recent discovery may have warranted its translation over and above the other works mentioned in the volume.Footnote 56

The knowledge of scholarship demonstrated in OE fits nicely within the landscape of English apocrypha scholarship more broadly, which is characterised by the diversity of works by such intellectuals as Toland, Whiston and Jones. There is little evidence in OE of the type of anti-clerical sentiment expressed by Toland, although the author's positive citation of James Ussher's work on the Ignatian epistles probably would have held religious qua political connotations concerning the status and shape of the episcopacy.Footnote 57 The author likewise differs from both Whiston and Jones with respect to the views expressed concerning the value of apocrypha and the authority of the New Testament canon. The author's narrative of the emergence of apocryphal writings follows, as noted above, a fairly conventional line whereby orthodoxy resisted the persistent onslaught of heretics and their forged writings, a position quite unlike Whiston's position on the hegemony of Athanasian orthodoxy. Though the author sees the works translated in OE as inoffensive to orthodox sensibility, they nevertheless maintain a sense of the special integrity of the New Testament canon. Incredulity is expressed, for example, at the Quakers’ apparent belief that the Epistle to the Laodiceans was genuine, but the author considers such belief rather harmless compared to those ‘who dare insert a counterfeit writing amongst the inspired records of the Church of God, without any mark of distinction set upon it’ (T, pp. lxv–lvi; cf. C, p. 23). In the view of the author, the apocrypha serve antiquarian interests and the accurate reconstruction of the early history of Christianity, but their distinction from authoritative canonical texts remains important.

Unfortunately, the views on the apocrypha expressed in OE did not become widely known because it never appeared in print. The Toronto manuscript closely imitates the print conventions of its day, but it is not certain that the book ever was intended to be printed, even though the author expressed an expectation, or at least a desire, that their ideas would become known: ‘There is no body I think of any tolerable temper will finde fault that these treatises are made publick in our own language’ (T, p. lxvii). Handwritten books were still quite common in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and formed a viable alternative to print in some disciplines.Footnote 58 Poetry, alchemical works, news and political and legal debate regularly appeared in handwritten form, as did academic works for use in the university classroom and religious works with the potential to cause controversy. Print and manuscript were complementary, not consecutive, forms of publishing, and both were sold at bookstores.Footnote 59 Some could even be bestsellers; Anthony Grafton notes the existence today of 200 to 300 copies of single handwritten books made after the advent of print.Footnote 60 An author's reasons to choose manuscript over print varied: artistic preference, prestige, concern over printer errors, the desire to retain ownership of the work and fear of censorship or recrimination.Footnote 61 This final concern led Hermann Reimarus to circulate his study of the historical Jesus, Apologie oder Schutzschrift für die vernünftigen Verehrer Gottes (‘An Apology for, or Some Words in Defence of, Reasoning Worshipers of God’), only in manuscript form. The study was printed by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing after Reimarus’ death, and even then as Fragmente des Wolfenbüttelschen Ungennanten (‘Fragments by an Anonymous Writer’) – the identity of the author was not revealed until 1813.Footnote 62 Several handwritten copies of the Apologie still exist, one in Reimarus’ own hand (catalogued as Hamburg, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, Cod. in scrin. 119).Footnote 63 Another example of handwritten scholarship, one closer to the field of Christian apocrypha, is Toland's Nazarenus. Toland circulated an early version of Nazarenus in 1710 prior to its expansion and printing in 1718.Footnote 64 Additionally, a manuscript copy of Toland's ‘Catalogue’, entitled ‘Amyntor Canonicus ou Eclaircissement sur le canon du Novum Testamentum’, appears to have accompanied the manuscript of Nazarenus to its dedicatee Eugène de Savoie in Vienna (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Ms 10325, d).Footnote 65 The example of Toland's combined publication regime of both manuscript and print demonstrate that scholarship could and would be circulated in a variety of material forms.

The two OE manuscripts seem to reflect the two methods of publication for handwritten books: by a specialist scribe for sale (T) and by an individual for a personal copy (C).Footnote 66 Given the inferior qualities of C (including scribal errors, the apparent excision of marginal notes and multiple scribal hands), it would seem that the author's decision to circulate the book in manuscript form did little to prevent alteration of the work – perhaps even theft, if the copyist of C is responsible for the removal of the attribution to ‘I. B.’, whoever that may be. But C also demonstrates a benefit of the flexibility and adaptability of manuscript transmission in its incorporation of Herold's Latin texts, thus adding to the utility of the work, even if it fails to give due credit to the material's creator.

7. Conclusions

So much remains unknown about the origins and transmission of OE. At present, only two copies are preserved, and at least one other must have existed to account for the differences between them. These three could represent a small sample of the number of copies that were once available, or they could represent the full reach of the text. Given that OE has gone largely unnoticed in scholarship for three centuries, it probably did not circulate widely. Nor does it seem to have had any observable impact on the study of Christian apocrypha. It is a prime example of what Don R. Swanson calls ‘undiscovered public knowledge’Footnote 67 – works existing here and there ‘like scattered pieces of a puzzle’ in manuscript catalogues and book lists but whose various parts have never, until now, been gathered together and presented to the scholarly world. As far as discoveries go, OE is not as dramatic as a new first- or second-century papyrus fragment found in the debris of an archaeological site or a jar of codices snatched from the skeletal clutches of a deceased monk interned in an ancient cemetery, but it is a curious artefact from the beginning of modern scholarship on Christian apocrypha. It is the earliest known effort to present a selection of the apocryphal texts then known by scholars to English readers. And the author of the Preface speaks of them, surprisingly, in a largely irenic way – the closing words, a comment on the Gospel of Nicodemus, are particularly notable: ‘I say that the worst I could conjecture of the way that it would be looked on as a rarity and do no harm, or else I should soon have determined what to have done with it, I mean have burnt it’ (T, p. lxx; cf. C, p. 24). The comment hints that the author was concerned about the reception of their work. Such concern may be why OE circulated only in manuscript form and (perhaps intentionally) among a limited audience of ‘ordinary Readers’ (T, p. lxix; cf. C, p. 24). If so, the context of this apocrypha collection is similar to how scholars often imagine apocryphal texts circulated in late antiquity and the Middle Ages: copied, circulated, read and interpreted in the shadows. That view has been re-evaluated in recent years, with discussions of certain extremely popular apocryphal texts occupying a quasi-canonical position and some apocrypha occasionally appearing within the canon. As OE seems to indicate, this now inadequate assessment of the reception and transmission of Christian apocrypha might be more appropriate to the early modern period, when scholars and theologians did have to be careful about arguments that challenged the political and theological orthodoxy of their day.