In several countries of the world, Ascension Day, the sixth Thursday after Easter, is a public holiday. This is the case, for instance, in Germany and Austria, the Scandinavian countries, France, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, and Indonesia.Footnote 1 In yet other countries, lively debates take place whether the fortieth day after Easter should be made a public holiday.Footnote 2 It is clear that wherever Ascension Day is celebrated as a holiday, the date is dependent on an interpretation of the well-known passage in Acts 1.1–11, an interpretation which maintains that Jesus appeared to his disciples ‘during forty days’ (v. 3) after his resurrection and was taken up to heaven only at the end of this forty-day period (vv. 9–11). The dependence is of course indirect, via the church calendar.

Considering the impact of the ‘forty days’ of Acts 1.3 on society at large in various parts of the world, it would be an interesting and not unimportant matter to consider whether Luke did indeed mean to say that Jesus ascended to heaven on the fortieth day after his resurrection. I will argue here that it is less than certain that this is what the text actually says; in fact, that this was almost certainly not what Luke meant to say.Footnote 3

1. The Contradiction between Acts and Luke Widely Accepted, but Problematic

Virtually all expositors of Acts 1.1–11 agree that Luke in this passage intends to say that Jesus' ascension took place forty days after Easter, in other words, that there was an interval of forty days between Jesus' resurrection and his ascension. The exegetes who hold this view include C. K. Barrett, Jürgen Becker, François Bovon, James Dunn, Joseph Fitzmyer, Gerhard Lohfink, Daniel Marguerat, and Richard Pervo.Footnote 4 Of course, anybody who interprets Acts in this way immediately faces the difficulty of reconciling this view with the ending of Luke's Gospel, for according to most expositors Luke 24.50–52 places the ascension of Jesus on the evening of the day of his resurrection, that is, on Easter Sunday.Footnote 5 Only a small number of exegetes still object that, if one accepts this interpretation, this day becomes so overloaded that the ascension of Luke 24.51 must have taken place on another day. But these timekeepers are reprimanded for their literalism by other scholars, among them Odette Mainville and Joseph Fitzmyer, who maintain that Luke 24.50–51 cannot but mean that the ascension took place on Easter Sunday evening.Footnote 6 The vast majority of commentators on Luke and Acts have decided to acquiesce in accepting an insoluble contradiction between the chronology of the ascension in Luke and that in Acts.

However, this resignation is open to serious objections. Why should we let this glaring inconsistency pass so easily? Why do we accept that one and the same author should deal with the chronology of one and the same event in such different ways? Joseph Fitzmyer even goes so far as to declare: ‘Why Luke has dated the ascension of Jesus in these two different ways no one will ever know’.Footnote 7 Is it not strange that we resign ourselves to such a flagrant contradiction within the work of one author, the more so since Acts 1.1–2 (τὸν μὲν πρῶτον λόγον…ἀνελήμφθη) refers back to Luke 24.51 (ἀνεφέρετο εἰς τὸν οὐρανόν)? The difficulties at issue are the following.

(1) The events narrated in Acts 1.4–14 correspond to such a degree with those related in Luke 24.36–53 that, if one assumes that the events of Acts 1.4–14 cannot have been the same as those of the resurrection day in Luke 24, one charges Luke with an unlikely repetition of two series of practically identical events on two different days: first on the day of the resurrection, and then again forty days later.

(2) In fact, the text of Acts 1.2–3 does not seem to suppose at all that Jesus' resurrection and his ascent to heaven were separated by an interval of forty days. In v. 2, Luke says that his first volume runs ‘until the day when he was taken up to heaven, after giving instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles’. Immediately after this, in a relative clause dependent on ‘the apostles’ just mentioned (v. 3), Luke points out that, after his death, Jesus presented himself to them alive during a period of forty days. Both the syntax and the order in which the events are narrated strongly suggest that, according to the author of Acts, the ascension took place, not after the forty days, but prior to them.Footnote 8

(3) In Acts 1.4, Jesus orders his apostles not to leave Jerusalem, but to wait there for the descent of the Holy Spirit. Since this scene (vv. 4–8) merges seamlessly into the scene of the ascension (vv. 9–11), Jesus gave this order on the day of his ascension, shortly before he was taken up to heaven. However, if the risen Jesus wanted the apostles to stay in Jerusalem, why did he not tell them so on the very day of his resurrection? Why did he wait forty days to tell them this, thereby running the risk that they would leave Jerusalem weeks before the Spirit descended? Would Jesus not have warned the apostles soon after his resurrection in order to prevent them from leaving Jerusalem and thus from missing the descent of the Holy Spirit? Compare how the disciples from Emmaus left Jerusalem on the day of Jesus' resurrection.

2. Previous Solutions

Over the centuries, numerous solutions have been proposed to remove the problem of the chronological discrepancy between Luke 24.51–53 and Acts 1.9–11. Here I can only mention a limited selection of them.

(1) Perhaps the earliest attempt to dispose of the problem is the deletion of the words ‘and he was carried away’ in Luke 24.51. This typically ‘Western’ reading of the Lukan text may go back to the second century. I agree with the great majority of recent and present exegetes that the resulting shorter text of vv. 51–52 is secondary, seemingly introduced to remove the chronological contradiction under consideration.Footnote 9 As a result of this shortening of the text, the ending of Luke (24.50–53) is no longer an account of the ascension. Jesus just takes leave of his disciples and disappears. Consequently, the ascension will indeed take place on the fortieth day after Jesus' resurrection, as the ‘Western’ editor of Luke thought Acts 1.2–11 suggested. In this way, Jesus' departure in Luke 24.50–53 and his ascension become different events. The ascension in Acts becomes the completion of the resurrection after five and a half weeks.

(2) Another old solution is to adapt, not the text, but the timetable of Luke 24 to that of Acts 1. Many authors admit that the ascension in Luke seems to take place on the evening of the day of Jesus' resurrection, but claim that in reality the forty days of Acts 1 must be thought to have fallen somewhere between the end of the appearance to the eleven in Luke 24.43 and the ascension in vv. 51–53. Augustine in his De consensu evangelistarum places the forty days between v. 50 and v. 51.Footnote 10 He is followed in this by Bede and Thomas Aquinas.Footnote 11 Early modern scholars indicated various other places in Luke 24 where the forty days of Acts should or could be inserted.Footnote 12 More recent authors, too, locate the forty days of Acts at different points in Luke 24, some between v. 43 and v. 44, others between v. 44 and v. 45, still others between v. 49 and v. 50.Footnote 13

(3) Another way of making Luke's timetable conform to that of Acts was to qualify the ending of Luke (24.50–53) as an interpolation, introduced when Luke–Acts was split into two separate books. Once Kirsopp Lake had launched this hypothesis, others applied it to both Luke 24.50–53 and Acts 1.1–5.Footnote 14 These interpolation theories removed the chronological problem efficiently but rather drastically, for they lacked any basis in the textual history of Acts as reflected in the manuscripts. Notwithstanding this, they have exercised a surprising attraction until recent years.Footnote 15

(4) Conversely, the chronology of Acts 1.2–11 could of course also be adapted to that of Luke 24. This happened when scholars became less interested in the history behind the ascension narratives than in how the narratives themselves emerged. According to J. G. Davies, for instance, the forty days of Acts 1.3 were introduced by Luke as an allusion to the story of Elijah (1 Kings 19.8); they therefore have only a typological, not a chronological meaning. Menoud followed suit and argued that forty was only a round number, typical of periods of revelation (Exod 24.18). Hence, in Acts 1.3, the forty days would have no chronological, but only a theological meaning: Luke introduced them to warrant that the eleven were well equipped as witnesses of Jesus' resurrection. In this way, the ‘forty days’ serve to legitimize the authority of the apostles.Footnote 16

(5) Several scholars tried to reconcile the occurrence of the forty days in Acts with their absence in Luke's Gospel by claiming that ‘[t]hat was a piece of information which he [Luke] may easily have gained between the publication of the Gospel and of the Acts’.Footnote 17 Still less probable, and less satisfactory, is the suggestion of another expositor who observes that ‘we must allow for the possibility that by the time he [Luke] came to write Acts, Luke had quite simply forgotten what he wrote in Luke 24’.Footnote 18

(6) Still other authors, although defending the longer reading of Luke 24.51 as the more authentic one, attempted to remove the apparent chronological contradiction between Luke and Acts by arguing that in Luke's view the ascension of Luke 24.51 and that of Acts 1.11 happened on different occasions.Footnote 19 Others had already done the same on the basis of the shorter text of Luke 24.51.Footnote 20 Michael Wolter, who retains the longer text, rightly notices the parallelism between Luke 24.44–53 and Acts 1.4–14, but points out three differences: the appearance of the angels and their message in vv. 10–11; the fact that the disciples do not return to the temple, vv. 11–12; and the enumeration of the names of the eleven in v. 13. Wolter sees these differences as evidence that the two passages refer to two different ascensions.Footnote 21 However, the agreements between Luke 24.44 and Acts 1.4–14 seem to be more striking and more important than the differences, and assuming two ascensions does not solve the difficulties mentioned at the end of section 1 above.

(7) At present, the prevailing approach to the discrepancy between Luke 24.50–53 and Acts 1.3–11 is to abandon any attempt to harmonize the two narratives, and rather to attribute the differences to the specific literary and theological function that Luke intended for each story, the one at the end of the Gospel, the other at the beginning of Acts. Luke 24.51–53 intends to conclude the Gospel with a brief but solemn description of Jesus' parting, which winds up the account of the appearances on the resurrection day. Acts 1.3–11, with its forty days, is claimed variously to give an answer to the disciples' and the readers' disappointment or uncertainty about the delay of the parousia (Wilson), to convey the idea of continuity between the time of Jesus and the time of the Church (Maile), to make an appropriate new start for Luke's second book (Van Unnik), to provide entry into the narrative world of Acts (Parsons–Pervo) and to provide the eleven (in retrospect) with incontestable and exclusive authority to guarantee the apostolic truth of the Church against other possible claimants to the Christian truth (Dunn).Footnote 22 Luke 24.50–52 underscores Jesus' ongoing presence despite his absence, whereas Acts 1.1–11 underscores Jesus' rigorous absence despite traces of his occasional presence (Bovon).Footnote 23 Many exegetes nowadays hold that, on the discourse level of Luke and Acts, we have two discrete and conflicting narratives relating the same event (the ascension), but dated to different days in order to fulfil different purposes.Footnote 24 According to this now widespread view, the two Lukan narratives must be allowed to stand side by side, each in its own right, in spite of the blatant chronological contradiction; either narrative can be explained as meaningful in its own way. We are so accustomed to this conciliatory view that we tend to overlook the seriousness of the chronological problem that troubled so many exegetes in the past, and to close our eyes to the absurdity of two different timetables being applied to one important event by one and the same author.

3. Chronological Difficulties within Acts 1.1–11 Itself

However, even if we accept the incompatibility of Acts 1.3–11, which places the ascension after forty days, with Luke 24.51–53, which dates it on the resurrection day, there remain the inconsistencies and anomalies within Acts 1 itself. We have noted these already. (1) According to vv. 2–3 Jesus was first ‘taken up’ (ἀνελήμφθη, v. 2) and then he appeared (παρέστησεν ἑαυτόν, v. 3) to the apostles during forty days. By contrast, the interpretation of vv. 3–11 now popular would have us believe that he first appeared during forty days (v. 3) and was then taken up to heaven (vv. 9–11). (2) If we accept this current interpretation, the question remains why Jesus waited forty days to order the eleven to stay in Jerusalem, thus giving them the chance to leave long before the Spirit descended.Footnote 25 (3) In addition to these difficulties, there is still another problem. Since the ascension mentioned in Acts 1.2 belongs to the events Luke says he has related in his ‘first volume’, this ascension must be identical with that mentioned in Luke 24.50–53. If the ascension mentioned in vv. 9–11 is supposed to take place after the forty days of v. 3, the result is that Luke in his prologue to Acts makes Jesus ascend twice to heaven: first in v. 2 (ἀνελήμφθη) and then once again in vv. 9–11 (ἐπήρθη, v. 9; ἀναλημφθεὶς…εἰς τὸν οὐρανόν, v. 11).Footnote 26 On the supposition that the second ascension took place after forty days, one cannot but conclude that Luke narrates two different ascensions of Jesus. But is this conclusion really plausible?

It appears that assuming two different timetables for the ascension in the Gospel and in Acts does not solve the problems, but exacerbates them. And if our resignation in the matter of chronology does not help to remove the exegetical difficulties in Acts 1.1–11, it is perhaps time to ask whether we do well to accept the temporal difference between Luke 24 and Acts 1 in the first place. I think that the current, ingrained interpretation of Acts 1.4–11, which places the ascension after the forty days of the appearances, needs to be reconsidered.

4. The Literary Structure of Acts 1.1–14 Revisited

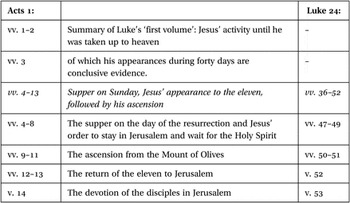

In order to attain a better understanding of Luke's timetable in Acts 1, it may be useful to look once again at the opening section of Acts and especially at its literary structure. The question of where the introductory section of Acts ends has been much discussed.Footnote 27 Since Luke begins his second volume, in the style of a traditional preface, by summarizing what he has told in his first volume, it seems reasonable to delimit the opening section by asking exactly where he begins to relate events not yet mentioned in his Gospel. In my view, it is not until v. 15, with the appointment of Matthias as the new twelfth apostle, that Luke breaks new ground.Footnote 28 Verses 1–14 are all paralleled in the Gospel (see Table 1 below). Consequently, there is good reason to see vv. 1–14 as the opening section of Luke's second volume. It is true that there is a certain shift in Luke's style between v. 3 and v. 4, since in vv. 1–3 he mentions previous events in a more general, summary manner, whereas from v. 4 onwards he relates particular events in more detail. Yet all the events mentioned in vv. 1–14 have their parallel in Luke 24. The opening, recapitulative section of Acts seems to comprise, therefore, the first fourteen verses of the chapter.

Table 1. The parallelism of Acts 1.1–14 and Luke 24.36–53

Table 2. The twofold literary structure of the prologue to Acts (1.1–14)

Let us now have a closer look at this section and try to retrieve its story line and its literary structure.

In vv. 1–2 Luke introduces his second volume by giving a concise summary of his first volume, running from the beginning of Jesus' ministry until the day of his ascension, including the ascension itself, briefly narrated in Luke 24.50–51 (ἀνεφέρετο εἰς τὸν οὐρανόν) and now picked up in Acts 1.2 (ἀνελήμφθη). The ascension took place after Jesus had given certain instructions to the apostles (Acts 1.2 ἐντειλάμενος; cf. Luke 24.47–49). In a relative clause (v. 3) qualifying the apostles just mentioned, Luke adds that Jesus, after his resurrection and ascension (v. 2, ἀνελήμφθη), continued to appear to them during a period of forty days. This is information Luke had not yet given in his Gospel. He adds it here, more or less parenthetically, because in Acts it is important that the apostles are eyewitnesses to Jesus' resurrection.Footnote 29 The apostles must have established with their own eyes that Jesus was alive, for it is precisely this that qualified them as guarantors of the truth. In Luke's Gospel, the apostles see the risen Jesus on one day only, the day of his resurrection (Luke 24.34, 36–51). In Acts, Luke extends the period during which the apostles are eyewitnesses of the renewed life of Jesus to forty days. During this longer period, they not only see him a number of times, but they are also instructed by him ‘about the kingdom of God’ (Acts 1.3). In Luke's view, this instruction makes the apostles reliable teachers of the Church, authorized guardians of the truth, and an effective tool against deviant ideas. The addition of the appearances during forty days is something Luke had not yet needed to mention in his volume on Jesus; but in Acts, his volume on the Church and the course it took in its first decades, this addition was important. The result of this addition was ‘the awkward break-off of the initial sentence’Footnote 30 of the prologue.

In v. 4, Luke resumes the summary of his Gospel and returns to the account of Jesus' conversation with the apostles on Easter Sunday evening. There is nothing to suggest any lapse of time between v. 2 (the day that ended with Jesus' ascension) and v. 4. Several commentators and translators insert an interval of time here, so that vv. 4–11 take place at the end of the forty days of the appearances.Footnote 31 But this seems not to be the case. For, first, there is nothing in v. 4 to indicate that what follows happened at a later date. Second, the meal mentioned here is evidently the same as that related in Luke 24.36–49, during which Jesus appeared to his disciples at the end of the day of his resurrection and gave them his orders. Third, Jesus' order to stay in Jerusalem and await the coming of the Spirit (Acts 1.4) is the same as the one he gave on Sunday evening in Luke 24.49. Fourth, as has correctly been observed by Menoud and Mainville, the term of forty days mentioned in v. 3 is not the term for the ascension, but for the duration of the period in which Jesus appeared to the apostles and gave them instructions: ‘appearing to them during forty days’ (δι' ἡμερῶν τεσσεράκοντα ὀπτανόμενος αὐτοῖς). The forty days are linked to the appearances, not to the ascension.Footnote 32

In vv. 4–8 Luke relates that Jesus gave the apostles certain instructions during a meal: that they were to stay in Jerusalem, to await the coming of the Spirit, and to become witnesses to Jesus, beginning in Jerusalem. For several reasons we are justified in assuming that this meal and the instructions given by Jesus are identical with the meal of Easter Sunday evening and the instructions given there, as recorded in Luke 24.36–49. For, first, in Luke 24 too, the disciples are together at a meal (it included broiled fish, v. 43), and the instructions Jesus imparts to the disciples are identical to those he gives in Acts 1.4–8. Obviously, in Acts 1.4–8, Luke is still summarizing what ‘Jesus did and taught…until the day when he was taken up to heaven’, as he had announced he would do in vv. 1–2.

Second, in Acts 1.2 Luke says that, according to his first volume, Jesus was taken up to heaven after giving instructions to the apostles. Again, Luke is referring here to the instructions given on the Sunday evening of the resurrection day (Luke 24.47–49). However, since in Acts 1.4–8 Luke is just giving the instructions mentioned in v. 2 in a more extensive form, the meal and the instructions of Acts 1.4–8, too, have to be dated to Easter Sunday.

Third, in Acts 10.40–42 Luke has Peter say that ‘God raised him [Jesus] on the third day and allowed him to appear, (41) not to all people but to us who were chosen by God as witnesses and who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead. (42) He commended us to preach to the people and to testify…’ This is an unmistakable reference to the episodes related in Luke 24.42–49 and Acts 1.2, 4–8. Acts 10.40–41 dates this episode to ‘the third day’, the day of Jesus' resurrection. Acts 10.40–42 is thus a strong indication that Luke likewise understood the meal and instructions of Acts 1.4–8 as events to have occurred on the evening of the day of Jesus' resurrection.Footnote 33

At least three passages thus suggest that the episode of Acts 1.4–8, Jesus' instructions given at a meal of the apostles, as well as the ascension, fell on Easter Sunday: Acts 1.2 (on the day of Jesus' resurrection, ‘after giving instructions to the apostles, he was taken up to heaven’), Luke 24.36–49 (the apostles' meal and Jesus' orders), and Acts 10.40–42 (the same meal and orders, now dated ‘on the third day’). In my opinion, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that, according to Luke, the events related in Acts 1.4–8, among them the ascension, were considered to have taken place on the day of Jesus' resurrection.

One consequence of this reading of Acts 1.4–8 is that v. 4, with its meal setting (συναλιζόμενος),Footnote 34 resumes and continues the scene of v. 2, which occurred on ‘the day when he gave instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles’. Verse 2 mentions Jesus' instructions only cursorily and generally, in no more than one word, ‘ἐντειλάμενος’. Verses 4–8 record the same instruction but in more detail, even more extensively than Luke 24.47–49.

5. The Mention of the Appearances during Forty Days in Acts 1.3: A Flash forward

If vv. 4–8 resume and continue v. 2, the literary position and role of v. 3 turns out to be somewhat special. Verses 2 and 4–8 speak about what Jesus did and said on the day of his resurrection. They are part of the summary of the Gospel which Luke announces and begins to give in v. 1. By contrast, v. 3 briefly anticipates Jesus' appearances during the forty days after his resurrection. We have already noticed why it is important for Luke to mention these appearances during forty days: they make the apostles better witnesses to Jesus' resurrection, more solid bearers of Jesus' teaching, and thus better guarantors of the truth professed by the Church Luke regarded as the true Church. In his Gospel Luke had not yet mentioned these forty days. But in Acts, Luke deemed it useful to insert a mention of the forty days as soon as he had said that Jesus ‘had been taken up’. He wanted to preclude the idea that the apostles had seen Jesus only on his resurrection day and had received his instructions only at the supper of that evening. No, Jesus had convinced them that he lived by appearing to them, not on one day only, but repeatedly during the forty days from the day of his resurrection and ascension. In other words, v. 3 is a brief flash forward: it speaks about appearances, which were still yet to happen at the moment when Jesus appeared and gave his instructions in v. 2 and vv. 4–8. To a certain extent, v. 3 interrupts the course of vv. 1–14, by running ahead of the events recapitulated in vv. 1–11.Footnote 35

‘Flash forward’ is a literary device which Luke uses also elsewhere in his work: to complete a story, he sometimes relates how it ended before narrating certain events that happened previous to that ending. A well-known case in point is Luke 3.19–20, where Luke concludes his account of the proclamation of John the Baptist by relating that Herod the tetrarch shut him up in prison. Yet in the following verses (vv. 21–22), Luke says ‘that all the people were baptized’, that is, the people who came out to be baptized by John (v. 7).Footnote 36 The baptisms mentioned in vv. 21–22 can only be baptisms by John, who, however, was already in prison. The result is that the mention of John's arrest and imprisonment in vv. 19–20 becomes a flash forward, albeit a rather awkward one. Another instance is Acts 11.28, where Luke completes his account of Agabus' prophecy about a great famine by the remark: ‘this happened in the time of Claudius’. This is a ‘reference to the future’Footnote 37 which leaps over at least twelve years. In Luke 6.16, at the end of the list of the twelve, Luke likewise employs flash forward when he rounds off his mention of Judas by saying that he ‘became a traitor’.Footnote 38

In all cases mentioned Luke uses the flash forward to round off a passage before resuming his story. This is also true in Acts 1.3.

6. The Structure of Acts 1.1–14 as a Whole and the Parallelism between vv. 4–14 and Luke 24.36–53

As we have seen, the whole of Acts 1.1–14 can be considered the summary of Luke's previous volume announced in 1.1, but this summary is articulated in two phases. It begins with a very general reference to ‘all that Jesus did and taught’, his instructions to the apostles on the resurrection day, and his ascension, vv. 1–2. This first phase of the summary is concluded by the flash forward in v. 3, which mentions Jesus' appearances during the forty days after his ascension. From v. 4 onwards, Luke resumes the narrative of the day of Jesus' resurrection and begins to recapitulate Luke 24.36–53 in more detail. The following table lays out the striking parallels between Acts 1.1–14 and Luke 24.36–53. With v. 4, Luke returns to the day of the resurrection and repeats his story of that day, as told in the Gospel, but now in more detail (and even with some additionsFootnote 39): the main features of this narration comprise the meal at which Jesus appeared to the apostles, his ascension, the return of the eleven to Jerusalem, and the devotion in which they spent their days there.

From this table it is clear that Acts 1.4–14 is a repeat or reprise of Luke 24.47–53. Consequently, Luke must have dated Acts 1.4–13, including the ascension, on Easter Sunday. Between v. 8 and v. 9 he assumes the time needed for a walk from Jerusalem to the Mount of Olives, a Sabbath day's journey,Footnote 40 perhaps a quarter of an hour, but not the lapse of forty days.Footnote 41 It is not until v. 14, with the periphrastic imperfect ‘they were constantly devoting themselves to prayer’, that the narrative reaches beyond the day of the resurrection and ascension. This is the beginning of the forty days of the appearances (none of which is narrated; they are only referred to in v. 3). This is also the beginning of the fifty days until Pentecost.

We can now represent the literary structure of the prologue to Acts (1.1–14) in the following table.

There is a join or light caesura between v. 3 and v. 4. One might say that what Luke does at the beginning of v. 4 is reculer pour mieux sauter.

7. Conclusion and Consequences

In Acts, Luke dates Jesus' ascension to the day of his resurrection, just as he had done in his Gospel. The forty days mentioned in Acts 1.3 are viewed by Luke as subsequent to the ascension, not as previous to it. The forty days are not the term fixed for the ascension; they are not linked with the ascension at all.Footnote 44 They are linked with the post-Easter, post-ascension appearances.

Here it should be remarked that several early Christian authors interpreted Acts 1.2–11 correctly as meaning that the ascension took place on the day of the resurrection, not after forty days. This applies, inter alios, to the author of Mark 16.19, Justin, and Irenaeus.Footnote 45 However, the wrong interpretation, which takes the forty days as the interval between resurrection and ascension, is represented by the ‘Western’ reading of Luke 24.51, by Tertullian, Cyprian, Lactantius, Chrysostom, and by many others.Footnote 46

In chronological terms, the difference which this interpretation of Acts 1.1–14 makes with the current and commonly accepted explanation of the ascension story in Acts is perhaps limited. The main point is that the ascension ought to be regarded as preceding the forty days of Jesus' appearances rather than following them. But the consequences of this revised chronology are numerous and far-reaching.

(1) The discrepancy between Luke's dating of the ascension in his Gospel and that in Acts ceases to exist. In both volumes of his work, Luke places the ascension at the end of the day of Jesus' resurrection: in both volumes Jesus' resurrection and ascension take place on the same day. Luke has not dated the ascension in two different ways, but in only one way.

(2) The ascension is not the final encounter of Jesus with his apostles; it is only the last encounter that happened on Easter Sunday. According to Acts 1.3, there followed other appearances and encounters during the next forty days, none of which is mentioned by Luke. He does not even mention the very last encounter.

(3) The so-called ascension in Luke 24 and Acts 1 is nothing but the conclusion of Jesus' third appearance on Easter Sunday, the first two being that to the disciples from Emmaus (Luke 24.15) and that to Simon (Luke 24.34). The ascension story is the closure of the narrative of the appearance to the eleven (Luke 24.36–52; Acts 1.4–12). Therefore, it is not a rapture story (‘Entrückungsbericht’); it is the closing of an appearance story.Footnote 47

(4) That the ascension story is part of an appearance story and not an independent rapture story follows also from the fact that, according to Luke, Jesus was already exalted and glorified since the moment of his resurrection. In Luke 24.26, the risen Jesus says to the disciples from Emmaus: ‘Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?’ Apparently, while he is on the walk to Emmaus, Jesus has already entered into his glory. ‘Here “glory” represents the term of Jesus’ transit to the Father; his destiny has been reached. Even while he converses on the road to Emmaus, he tells the disciples that he has already entered upon that status—he is in “glory”, and from there he appears to them'.Footnote 48 In Luke, the tomb is empty because Jesus is in heaven. This means that when Jesus appears after his resurrection (as he does three times that same day), he appears from heaven;Footnote 49 when he disappears, he disappears to heaven. For each appearance he descends temporarily to the surface of the earth, travelling up and down between heaven and earth. The first disappearance occurs at Emmaus (Luke 24.31). The second, concluding the appearance to Simon, is not mentioned (Luke 24.34). The third is the so-called ascension (Luke 24.50; Acts 1.9–11). Though Luke may have described the scene of the ascension with some traditional ‘apocalyptic stage props’ current in rapture stories,Footnote 50 this narrative unit is no less the closure of an appearance story.Footnote 51

(5) There is no reason to assume, as Lohfink does, that between his resurrection and his ascent to heaven, Jesus was in some mysterious intermediate state, a state of transition, glorified but not exalted.Footnote 52 Some exegetes have located Jesus ‘on earth’ or even in ‘some hidden place on earth’ in the time between resurrection and ascension.Footnote 53 But this is incompatible with what Jesus himself says to the men from Emmaus, namely, that he has already been glorified (Luke 24.26).Footnote 54 Consequently, Jesus appears to the disciples from Emmaus (Luke 24.15–31), to Simon (Luke 24.34) and to the eleven (Luke 24.36) from the heavenly glory which he had attained through his resurrection. ‘To Luke, Jesus is…the Exalted One from the resurrection onwards and he [Luke] does not postpone the exaltation forty days. The post-resurrection appearances described in the Gospel and Acts are all appearances of the already exalted Lord “from glory” or “from heaven”.’Footnote 55

(6) It is not correct to say that Luke has abandoned the traditional unity of resurrection and exaltation and postponed the exaltation of Jesus in glory.Footnote 56 As from his resurrection, Jesus is the exalted one, taken up to heaven. This is the case both in Mark and Luke: Luke does not separate Jesus' exaltation/assumption from his resurrection. He has Jesus taken up to heaven at the moment of his resurrection. However, according to Luke, the ascension is not Jesus' exaltation/assumption; the ascension occurs at the end of the day on which Jesus was raised and taken up to heaven, that is, some fifteen hours after his resurrection and exaltation.

(7) One advantage of the proposed explanation of Acts 1.1–11 is that now Jesus does not wait forty days before ordering his apostles to stay in Jerusalem. He now gives them this instruction on the day of his resurrection, making sure that they would not depart before the appointed time. This timing of Jesus' instruction to the apostles of course makes much more sense than such an instruction being given after forty days.

(8) Another consequence, and perhaps an advantage as well, is that Luke's chronology of Jesus' resurrection and exaltation/assumption to heaven can now be considered as agreeing with that of practically the entire early Christian tradition. In the first century the resurrection of Jesus and his exaltation/assumption/glorification are generally conceived as taking place in one movement and virtually simultaneously. This tradition is attested by, inter alia, Phil 2.9; 1 Thess 1.10; Rom 8.34; Mark 16.1–8; Heb 12.2; 1 Pet 1.21; 3.21–22; 1 Tim 3.16, and Mark 16.3b (codex k).Footnote 57 The tradition in which Jesus' resurrection and exaltation are one process is rooted in the Jewish martyrological tradition, according to which God vindicates the righteous one who loses his life as a consequence of his faithfulness and obedience to God by raising him and renewing his life in heaven.Footnote 58 Luke is in full agreement with this old and widespread tradition in that he regards Jesus as risen and exalted on Easter Sunday, early in the morning, in one act. However, the ascension is not part of this process of resurrection, exaltation, and glorification. At the moment of Jesus' ascension, his resurrection, exaltation, and glorification are already things of the past.

(9) In Luke one should distinguish between Jesus' exaltation, that is, his entering upon his glory, encompassing his being taken up into heaven and his being raised at the right hand of God, on the one hand, and the ascension in Luke 24.51 and Acts 1.2, 9–11, on the other. The resurrection and the exaltation are one event; the ascension is another event. They are separated by a whole day: the Sunday of the resurrection. Consequently, it is not really correct to say that, for Luke, resurrection and ascension are two sides of the same coin.Footnote 59 In Luke and in Acts, the story of Jesus' ascension is neither a part nor a corollary of the resurrection. It is the end of a subsequent story, namely that of Jesus' third appearance.Footnote 60

(10) Consequently, it is not correct either to say, as many exegetes do,Footnote 61 that Luke's ascension stories are an attempt to historicize, materialize, and visualize the kerygma of Jesus' resurrection/exaltation/glorification/enthronement. This is incorrect because the ascension in Luke and Acts is not a component of the resurrection/exaltation/glorification/enthronement complex. It is an element of an appearance that occurred subsequent to Jesus' entering on his glory.

(11) If Acts 1.9–11 is neither a rapture story nor an account of Jesus' exaltation, all emphasis in this passage falls on the announcement given by the two men in v. 11: ‘He will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven’. Luke's main intention in vv. 9–11 is not to depict the ascension, but to encourage his readers and hearers to hold on to their hopes for the coming of Jesus in the future. Luke could have the two men say anything, for instance, ‘Now you know that he is the Son of God’ or ‘Now you know that he is at the right hand of God’. However, the fact that Luke chooses to make them say ‘He will come in the way you saw him go’, indicates that Luke wants to exhort his audience to a sustained belief in the parousia.Footnote 62 Luke is aware of the delay of the parousia, and wants to reaffirm the expectation of Jesus' intervention at the end of time for his own day.

Finally, one should begrudge nobody a day off, but the observance of Ascension Day on the fortieth day after Easter is due to a misunderstanding of Acts 1.3–11.Footnote 63 This misunderstanding is as old as the shorter, ‘Western’ reading of Luke 24.51 and Tertullian's Apologeticum, and thus goes back to 200 c.e. at the latest; but it remains a misunderstanding.