Introduction

There is a growing interest among today’s Turkish youth in a type of writing called “underground literature” (yeraltı edebiyatı), which raises issues of contemporary importance in Turkish culture. Yet the exact meaning of the term, its relevance, and even its very existence is the subject of intense debate. This study attempts to better understand the nature of underground literature in Turkey, the role it plays in the lives of Turkish youth, and its relationship to the Western countercultural literature that is being translated into Turkish in ever-increasing numbers. In order to fully understand the underground literature phenomenon and its social relevance to Turkey, we need an account of who is reading these works and the impact they have on mirroring and shaping the thoughts of their audience. This study seeks to provide such an account. Underground literature is one of the cultural sites in Turkey where such controversial issues are vented in youth culture, and thus it behooves us to understand the nature of this debate and its possible wider relevance for Turkish culture.

The immediate impact of this mixed-media study is to provide a clearer understanding of what exactly constitutes underground literature in the minds of Turkish youth and the relevant issues it raises for them in contemporary Turkey. Although Turkish youth culture is not defined exclusively in terms of its relationship to underground literature, this genre is receiving increasing attention, and the reactions it engenders have the potential to tell us much about the opinions and thinking of the genre’s primary audience; namely, Turkey’s young adults. This study also contributes to the burgeoning field of youth studies in Turkey by providing concrete data about the demographic make-up of this group and their beliefs regarding important issues central to Turkish culture, such as issues of politics, ethics, gender and sexuality, religion, and attitudes toward Westernization / globalization. An analysis of the influence of underground literature on Turkey’s youth thus provides a means of understanding how this group relates to the touchstone issues facing Turkish society today. While it is impossible to predict the future, an analysis of the role underground literature is playing in the lives of Turkey’s youth could provide a glimpse into the shape of things to come.

The debate

What exactly is underground literature? The history of the term, its definition, and even its very existence are the subject of much debate.Footnote 1 The bulk of discussion on this topic has occurred in dossiers contained in the literary journals Varlık Footnote 2 and Notos.Footnote 3 All the authors, critics, and editors participating in the discussion agree that underground literature involves texts that lie outside social norms, but the exact nature of this outsider status has fueled heated debate. Most contributors present two overlapping conceptions of the term. The first trend views underground literature as a term that signifies works that are distributed outside normal distribution channels. Here, the underground is closely associated with samizdat, self-published works that eschew mainstream audiences. The other trend focuses on the themes, issues, and characters of underground literature. This group argues for a definition based on content: underground texts transgress social norms.

For critics who view underground literature in terms of distribution, the key question becomes just how “underground” underground literature should be considered. Many call attention to the brisk sales enjoyed by such texts and point out that the term has generated widespread interest, and indeed seems to be growing. Most of the critics involved in the debate associate the underground with the clandestine, and thus many have argued that such exposure amounts to simply a “marketing gimmick” designed to sell books.Footnote 4 Thus a contradiction arises: if “underground” is meant to denote works lying outside the mainstream, can books that are published by large publishing houses and receive government approval really be considered underground?Footnote 5 While this debate can sometimes be considered academic hair-splitting, it does raise questions concerning the perception of underground literature by its readers, as well as what reading underground texts might signal.

Critics who focus on underground literature’s thematic elements typically discuss the transgressive nature of these works. Underground literature presents characters engaging in very different lifestyles that lie outside social norms. Oftentimes, these protagonists are unable or unwilling to adhere to social dictates, leading to works that become characterized as pessimistic. This has led to many critics employing the terms “dark” (kara) or “evil” (kötülük) when discussing the genre, though not all critics employ these terms in pejorative ways.Footnote 6 For most, this challenging of authority is seen as capable of expanding the boundaries of literary language and questioning the social assumptions in Turkish society. Underground literature’s association with transgressive characters, themes, and culture is important for understanding its appeal to Turkish youth struggling to find a means of questioning society in an acceptable manner.

While all of these positions have merit and help to paint a picture of underground literature’s origins and functions in Turkey, it is our belief that concrete information concerning reader opinions in these matters would go a long way toward clarifying and perhaps refocusing this debate on the function of underground literature in the lives of Turkish youth. Our hypothesis—namely, that underground literature is one of the main arenas for addressing delicate subjects in Turkish society by today’s youth—has not been adequately addressed by the existing literature. This is because the debate concerning underground literature and its worth is often centered on the stylistic and formal properties of the texts or their place in the Turkish literary tradition. All of these approaches are interesting, yet they fail to address the cultural work that underground literature is performing among its Turkish youth readers. This study approaches the field from the opposite side of the fence, asking how readers respond to the “underground” themes that this literature forces to the surface.

Underground literature in the media

Articles devoted to underground literature have also appeared in mainstream print media. In terms of its Western, imported variant, discussions typically revolve around a single author or text. These pieces are for the most part descriptive, presenting the lives and works of writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, or William S. Burroughs to readers who are probably unfamiliar with these names. Oftentimes such articles appear upon publication of a translation or the release of a film dealing with such figures. Translations of such writers appeared as early as the 1970s, but the bulk of translations began in the 1990s and has continued into the present. There are three primary types of printed media outlets that cover the genre: established literary journals such as Notos and Varlık, newspapers (typically those more left-of-center politically), and weekly arts supplements such as Radikal Kitap. Although fanzine culture has abated from its height in the early 1990s, several noteworthy publications, such as Underground Poetix, still provide translations and informative pieces on underground figures to their readers as well. Given that all these print publications choose to discuss the topic of underground literature and frequently address new textual products appearing in the cultural sphere, all of this coverage has so far been laudatory.

When mainstream print does delve into the issues raised by such Western countercultural imports, the focus tends to be on the rebelliousness of underground literature. The focus here is almost exclusively on “Beat Generation” texts, though other countercultural products do make an appearance. Beat and countercultural works are seen mainly as engines of social change. Attention so far has tended to focus on the means of this rebelliousness in the American context; few critics discuss the potential such underground products hold for Turkish society at any great length. The bracketing of imported underground products into a strictly Western context allows many topics sensitive in the context of Turkey to be discussed quite openly. Homosexuality and drug use, for instance, are addressed repeatedly, though seldom in relation to Turkish examples. Occasionally critics will venture into the question of literary style, usually to discuss the use of slang. But even here, slang typically raises the question of whether such language is transgressive, and the ways in which it is co-opted by mainstream society and rendered less threatening.Footnote 7

The reception of Turkish underground literature in the printed press outside of the pages of Notos and Varlık has focused around the question of the “loser” (kaybeden). For many, Turkish underground literature has its origins in Oğuz Atay’s 1972 modernist classic, Tutunamayanlar (literally, “those who cannot hold on,” often translated as The Disconnected). The emergence of the concept of the “loser,” or those unwilling or unable to fit into the dictates of society, gained momentum in the late 1980s and the 1990s in Turkey. It was also during this time that Western countercultural literature entered Turkey, mainly through translations and articles appearing in fanzines and rock-and-roll magazines such as Stüdyo İmge, Çalıntı, and Rol. Thus, the reception of Beat and countercultural products became associated with a burgeoning rock culture that drew upon anarchist, punk, and grunge elements to wage an individual (rather than collective) assault on Turkish culture.Footnote 8 Radio programs such as “Kaybedenler Kulübü” (the Losers’ Club), which was made into a film of the same name in 2011, and the rise of the underground publishing house 6:45 (Altıkırkbeş) signaled a retreat from the collectivist politics of the past in terms of a new form of individual cultural rebellion. Western underground literature, with its emphasis on lifestyle choice and personal discovery, was perfectly situated to contribute to this sea change in Turkish cultural life.

Online discussion of underground literature, in both its Western and Turkish variants, occurs in several forms. The most prominent of these include online journals and publisher’s websites. Edebiyathaber and Sabitfikir are two prime examples of the former. While not exclusively devoted to underground literature, both provide reviews of books and translations, art news, and profiles of writers, as well as discussion of topics relevant to Turkish youth, such as the Gezi Park demonstrations. Publisher’s websites are likewise an important source of information on the issues surrounding underground literature. Sel Yayıncılık’s site, for instance, kept readers abreast of the court developments surrounding the censorship trials of William S. Burroughs’ The Soft Machine (Yumuşak Makine) and Chuck Palahniuk’s Porn Death (Ölüm Pornusu). Perhaps the most important example here is the underground publishing mainstays 6:45. In addition to offering an extensive catalog of underground texts, their website promotes a range of products, from books to T-shirts to handbags, designed for underground literature fans.

The internet also provides an important forum for readers themselves. Numerous fan websites, blogs, and Facebook pages devoted to underground literature and specific authors disseminate news, facts, and opinions to a wide range of readers. The most notable of the personal websites and blogs are 6:45 publisher Şenol Erdoğan’s “Trash Kulture,” Altay Öktem’s “Karakalem,” and “Arızalılar Kulübü,” a page devoted to Bukowski fans. While more could certainly be mentioned, these websites epitomize the sort of do-it-yourself aesthetic which dominates underground literature circles. In much the same manner as earlier fanzines, they provide readers of underground literature with up-to-date information on events, new releases, and goings-on in the genre while also providing a forum for discussion. Facebook pages are even more numerous. Although they seldom delve deeply into the issues that underground literature raises, these sites provide internet users with a range of images, quotes, memes, and suggestions for further reading that raises the profile of the genre immensely. They also provide discussion threads that allow fans to debate the merits of their chosen authors or to provide additional information that others might find interesting. Discussion is often terse, in keeping with the medium’s typical brevity, but both personal webpages and Facebook pages provide readers with additional information concerning underground literature outside existing channels of communication.

Reader response to underground literature reaches its zenith in Turkey’s famous website “ekşi sözlük.” This “sour dictionary,” which was created in 1999 by Sedat Kapanoğlu,Footnote 9 allows anonymous users to respond to topics in a mostly uncensored and uninhibited manner. While it would be impossible to chronicle the various entries that appear under the topic “yeraltı edebiyatı” and attempt to define, explain, and comment on underground literature, the vast majority of these are admiring in tone. Nor is the subject of underground literature a minor consideration on the site: all the major authors associated with the genre, both foreign and domestic, have their own threads. The Turkish poet küçük iskender, for example, has generated 626 responses as of January 26, 2015, with discussion of his homosexuality and poetry generating heated debate. Terms like “Beat Generation” (Beat Kuşağı), journals such as Underground Poetix, and even the publishing houses Ayrıntı Yayınları and 6:45 have topic threads that can contain hundreds of entries. Given that “ekşi sözlük” is considered a site where the youth of Turkey can voice their concerns uninhibited, it appears as though underground literature is a topic worthy of consideration for this group.

Literature review

What makes the act of reading so difficult to understand is that it is influenced by numerous factors that play a role in textual interpretation. The linguist and literary theorist Roman Jakobson attempted to tackle this problem by pointing to six functions of language that influence verbal communication. Literary texts are a special case, as they involve a time lag between the addresser of the message and the addressee who must decode the text without direct access to its originator. By amending Jakobson’s model, however, it becomes clear that literary communication is subject to recontextualization at every step of the process. Not only does the author seek to convey a particular meaning or attitude, but once the text becomes independent of its creator, it takes on a status of its own. Add to this the institutions seeking to highlight certain aspects of the text and the medium of delivery and its generic considerations, not to mention the historical and cultural context, and it is easy to see how the reader is bombarded with filters for understanding literature. Reading practices are thus overdetermined from the very start.

The sociology of literature has tended to find meaning either in the institutional nature of the literary exchange or in the cultural objects themselves. Wendy Griswold, in her article “The Fabrication of Meaning,” discusses the scientific thinking on the relationship between society and culture. She observes that the field is caught in a bind: both society and culture must retain autonomy in order to be studied effectively, yet there is mutual influence between them as well. Social scientists who favor an institutional approach, the most famous of whom is Pierre Bourdieu, view cultural objects like literary texts only to the extent that they “have been influenced by, and influence, socioeconomic structures and institutions.”Footnote 10 The text itself, along with the individual autonomy of the reader, is elided. The other trend in the field is to examine the cultural objects themselves. This interpretative approach, epitomized by critics such as Clifford Geertz, Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson, and Dick Hebdige,Footnote 11 gets closer to the reader, but such studies, Griswold argues, are “neither generalizable nor confirmable.”Footnote 12 Moreover, the group dynamic subsumes the autonomy of the individual, with the cultural object coming to represent the group because the group projects its meaning onto the cultural object. But how did this meaning become constituted in the first place?Footnote 13 Ultimately, Griswold argues for the inclusion of readers into this discussion as a way out of this impasse. She argues that “by looking at the construction of cultural meaning to discover what is taken for granted, presupposed, by a group of cultural recipients, one may begin to map the commonsense, shared understandings and ideology of the group.”Footnote 14 As Griswold’s later work on the production and reception of Nigerian fiction demonstrates,Footnote 15 the reader must be actively engaged in order for a full understanding of the literary process to be achieved. Readers are an important, if neglected, element in the meaning-making process, and deserve further consideration.

The journey to the acceptance of the reader as worthy of study did not come easily. Although interest in the reader can be traced back to Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller as well as to the English Romantics and the New Critics,Footnote 16 it was not until the late 1960s and early 1970s that the role of readership began to be seriously theorized. In a reaction to the textual formalism espoused by the New Criticism, University of Konstanz theorists such as Wolfgang Iser in his The Implied Reader (1972) and The Act of Reading (1976) and Hans Robert Jauss in Toward an Aesthetic of Reception (1982) began to discuss the reader in a serious manner. However, the authority of the text still held sway.Footnote 17 Iser, in both of his books, posited “an ideal reader whose expectations are contradicted and whose responses are corrected by the authoritative text.”Footnote 18 The other luminary in the field, Stanley Fish, likewise sought to decenter the text by arguing for “interpretive communities” that provide readers with reading strategies. Readers share an internalized understanding of language that helps guide interpretation to a subset of possible meanings. Janice Radway criticizes Fish’s work as too narrowly focused on reading practices within academia,Footnote 19 while Molly Abel Travis, in Reading Cultures: The Construction of Readers in the Twentieth Century, believes Fish’s concept “does not adequately account for changes in interpretive conventions and differences among interpretations, and it also ignores questions of agency in reading.”Footnote 20 Try as they might to shift focus toward the act of reading, these early theorists were loath to abandon the primacy of the text.

The next stage came with the idea of the resistant reader. Roland Barthes’ S/Z (1970) and The Pleasure of the Text (1973) both emphasized a reader who challenged the text rather than passively accepted its dictates.Footnote 21 Now the reader came to the fore as the constitutive element in interpretation. Susan Rubin Suleiman and Inge Crossman’s edited volume The Reader in the Text (1980) was also an important moment here.Footnote 22 Jauss was ahead of Iser in this regard: Toward an Aesthetic of Reception examined literary reception as it occurs across time, highlighting the difference between the text’s construction and its reception.Footnote 23 Here the reader becomes a subject with agency, able to contribute to the construction of meaning. The move toward the reader was likewise underway in the Media Group at Birmingham University’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, critics like Stuart Hall, David Morley, and Angela McRobbie examined interactions between popular texts and audience reception. This group likewise posited a reader who was capable of producing meaning. Unlike the Frankfurt School theorists who saw the “culture industry” as a monolithic, hegemonic force that easily influenced its audiences, these Marxist-inclined critics found redemption in a reader who was able to challenge ideological messages instead of accepting them—the reader became the “bricoleur” rather than the “dupe.” A new era of cultural studies was born, with critics such as Hall and John Fiske focusing on consumers who used cultural products to arrive at their own meanings.

This study follows in the wake of such cultural studies, but seeks to bolster claims about readership through an appeal to quantifiable data. In this sense, our work is most closely related to that of Janice Radway. In her important work Reading the Romance, Radway examines the reading practices of romance readers themselves. Employing interviews and questionnaires, Radway’s work is a touchstone for those who want to discuss reader response in a detailed and critical way. Radway claims that her work attempts to examine “the way such cultural forms are embedded in the social life of their users.”Footnote 24 While there are numerous readers, each with their own concerns, “there are patterns or regularities to what viewers and readers bring to texts in large part because they acquire specific cultural competencies as a consequence of their particular social location.”Footnote 25 Thus, for the purposes of this study, though all readers are individual, we can say something about a difference in Beat reading strategies based on differing cultural contexts. We also need to be aware that distribution networks and institutional practices have likewise lent a different cast to Western Beat and countercultural products.Footnote 26 Not that such a study is unbiased. As Radway herself claims in her introduction, à la Clifford Geertz, “even ethnographic description of the ‘native’s’ point of view must be an interpretation.”Footnote 27 Such a caveat also applies here. Ultimately, this study seeks to understand the ways in which underground literature is used by (predominantly young) Turkish readers and the impact it has on influencing youth thinking on sensitive topics in Turkey.

While the international scholarship on Turkish underground literature is unfortunately scant, several Birmingham Centre theorists have looked specifically at the meaning and relevance of subcultures. Dick Hebdige’s Subcultures: The Meaning of Style is seminal in this regard.Footnote 28 Along with Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson’s Resistance through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain, Hebdige’s study exemplifies the sort of cultural studies approach conducted by those working at the Centre.Footnote 29 Drawing on studies conducted with youth gangs in the early twentieth century at the University of Chicago, these critics examined youth subcultures and the reasons young people are attracted to them. This approach has proved influential, informing work done by Donna Gaines and Henry Giroux, who look at American youth cultures in the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 30 Such recent scholarship as Rupa Huq’s Beyond Subculture: Pop, Youth, and Identity in a Postcolonial World and David Muggleton’s Inside Subculture: The Postmodern Meaning of Style (Dress, Body, Culture) has productively engaged this approach in light of postmodernism and globalization.Footnote 31 Such work is useful in helping us to understand why anti-establishment genres might be an attractive draw for a certain segment of Turkish youth dissatisfied with the current state of affairs in Turkey. Compelling as these accounts may be, however, they do not fully explain the situation in Turkey.

Historically, socially, and culturally, Turkey is very different from the West, and in order to understand underground literature’s unique role in this country we needed further contextualization from scholars working in the specific field of youth research in Turkey. At the end of the Ottoman period and into the early republic, the concept of “youth” was associated with modern transformations in society. However, with the advent of the Cold War, economic and social changes in Turkey resulted in a shift in perspective toward the problems faced by youth and their desire to build youth movements. With the coup of 1980, solutions for managing youth and the problems they were seen to represent became dominant in the literature. Current research has moved beyond this model, examining issues of identity formation, lifestyle choice, class, gender, and religious issues, as well as ethnic and economic concerns affecting Turkey’s youth. As the role of underground literature has yet to be studied, this project represents a unique contribution to the field of youth research. Turkish youth research has been dominated by psychological and pedagogical studies, with social and cultural approaches receiving less attention.Footnote 32 Our research draws broadly on the work of scholars like Leyla Neyzi, Demet Lüküslü, and Ayşe Saktanber, whose work explores youth identity construction as they intersect with socioeconomic concerns.Footnote 33 As a consumable product caught up in the logics of self-definition, underground literature needs to be theorized within a framework of young people’s attempts to give expression to personal beliefs, and our study seeks to make that connection explicit.

The originality of this project is twofold. So far, the writers and critics of underground literature, and not the readers themselves, have dominated discussion on this topic. To fully understand underground literature’s relevance, we need to add to this valuable scholarly debate an objective appraisal of who is reading this material and why they are reading it. In order to accomplish this, a methodological approach novel to literary studies is required. Typically, literary analysis proceeds from close readings of texts coupled with a theoretical framework that helps to make sense of the work. Our study furthers such endeavors by employing the more quantitative methods of the social sciences. Understanding reader response can only come through a mixed method that combines in-depth interviews and media analysis with focus groups and questionnaires designed to provide a clearer picture of reader demographics and their correlation with attitudes and opinions on the issues that underground literature raises.

Methodology

The main objective of this project is to provide a clearer understanding of the role that underground literature is playing in the lives of Turkey’s youth. In order to accomplish this goal, this study set itself two interrelated tasks. The first involved developing a sense of reader demographics through in-depth interviews and media analysis. Once we had an idea of who is discussing underground literature and why this discussion is taking place, we then proceeded to form focus groups that allowed for the construction of more detailed questionnaires that examined reader beliefs about issues of paramount importance to Turkey today. These focus group responses were honed into two longer questionnaires that were distributed to a group of underground literature readers (n=302) and non-readers of roughly the same demographic composition (n=306). This process provided a sense of the comparison of underground literature readership and its relation to other non-underground literature youth readers. But we were also interested in perceptions and attitudes, as well as underground literature’s role (if any) in shaping these. Our study reveals not only who is reading underground literature and their reasons for doing so, but also the importance readers of underground literature place on this phenomenon and the influence it has on shaping attitudes towards critical national issues such as political beliefs, ethical considerations, sexuality and gender, religion, and beliefs about Westernization and globalization.

The first step was to determine exactly how large the readership is for underground literature in Turkey, as well as its age, class, gender, social, and geographic parameters. In-depth interviews with publishers, book distributors, translators, editors, and critics gave a better picture of reader demographics. This provided us with a better sense of the topics under discussion, clarified the demographics of underground literature’s readership, and thus allowed us to refine the questions we posed to readers in the second stage of the project. In tandem with these interviews, we also conducted a focused analysis of underground literature’s print and online media presence. Our team perused the extant print literature on the topic and gathered information on the various websites devoted to or associated with underground literature. By examining the quantitative data collected from this analysis of print sources and websites associated with underground literature, we developed a clearer understanding of reader demographics and the sort of issues that are attracting readers to this type of literature.

Armed with this information, we were prepared to conduct the second phase of the investigation. In this phase, we utilized focus groups and questionnaires to collect qualitative and quantitative data on the thoughts and opinions readers of underground literature had on a range of topics. Data was collected through two sources. The first was university students. Working with Tanfer Tunç, the vice president of the American Studies Association of Turkey and an assistant professor at Hacettepe University in Ankara; Işıl Baş, an associate professor at Boğaziçi University in İstanbul and the director of that school’s cultural studies program; Ahmet Beşe of Atatürk University in Erzurum; and Zafer Parlak of İzmir University, as well as with students at Koç University, we formed a series of focus groups at each university that (on average) consisted of three sessions with seven to ten students each. This had the advantage of informing us about the extent to which underground literature has permeated Turkish university youth culture, what topics are important for those it has affected, and what types of students are reading it.

Once this data had been correlated and analyzed, we drew on the results of our focus groups to create detailed questionnaires that were distributed as a quota sampling (n=608) of both those who have heard of underground literature and those who have not. Quota sampling was used again to determine how widespread knowledge of underground literature is within both a group of self-reported readers and a set of “non-readers” of underground literature of the same age group and with similar reading tendencies. The questionnaires designed for readers were meant to elicit responses concerning their opinions about underground literature, the issues of importance that it raises for them, and their personal backgrounds. In addition to the same demographic questions asked of readers, non-readers were given a series of eight (8) quotes taken from both Western underground texts in translation (n=4) and from Turkish underground works (n=4). The result was a useful comparison of how underground literature’s readers viewed the genre and how non-readers exposed to such texts felt about the issues that they raise.

Findings

Overall, the findings of this mixed-media study confirmed many of the initial assumptions about readers of underground literature that we had gleaned from our media and web analyses, interviews, and the focus groups we conducted in four Turkish cities (İstanbul, Ankara, İzmir, and Erzurum) among university-level students. There were, however, many notable exceptions that are worthy of examination. As the “readers” group (n=302) generated the most important results of our study, we will focus mainly on this group, supplementing discussion with results from a “non-reader” group (n=306) composed of roughly the same demographic makeup as the “readers” but who did not report any knowledge of “underground literature.”Footnote 34

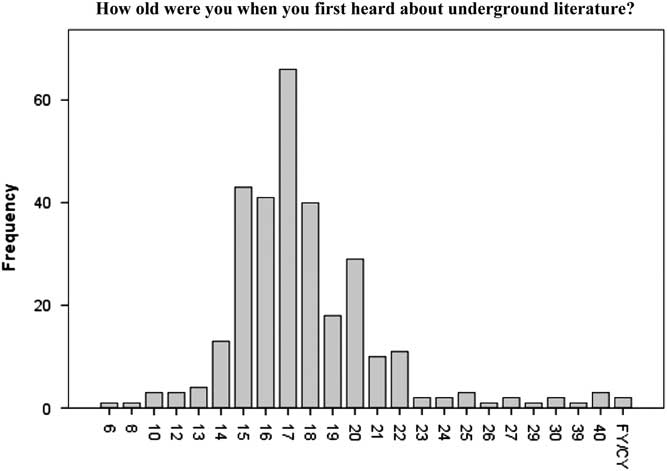

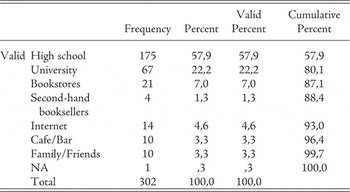

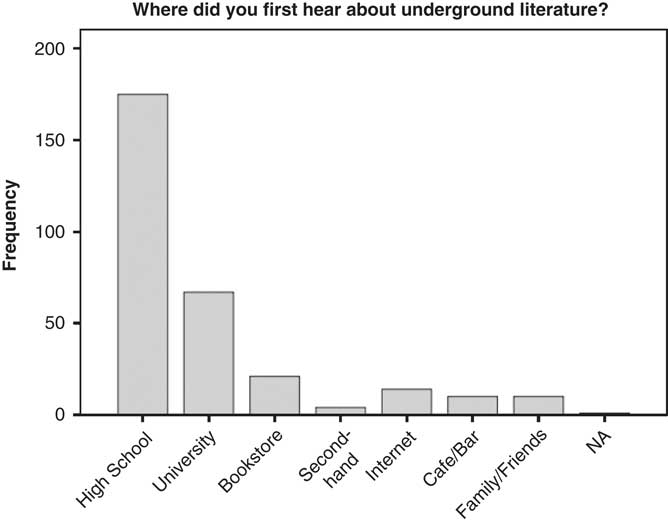

First, let us look at the demographics. As predicted, readers of underground literature are young—averaging 23–24 years of age. This was in line with the preliminary data we gleaned from interviews with both publishers of underground literature, editors of underground journals, and several critics involved in the underground literature discussion. This average hides a high number of even younger readers. 57.9 percent of readers first heard of the genre in high school, when they were 17–18 years of age (see Appendices 1 and 2). This constitutes what is to us a surprisingly early age for being introduced to the genre. This was not an entire surprise, as some publishers had mentioned very young readers among their subscribers, but to see readers as young as 14–15 years of age—27.8 percent were first introduced at this age—was a bit of a shock.

Underground literature is a male-dominated genre. The majority of its writers are male, and most texts present protagonists with a decidedly masculine viewpoint. While conducting a focus group at Boğaziçi University, for example, one female master’s student quipped that the genre mainly attracted males trying to “pick up” young women. Numerous other female focus group participants also noted misogynistic tendencies in the genre, though many nevertheless remained readers of such work, overlooking such male bias. We had thus been led to believe by our preliminary investigations that, due to the often misogynistic content of underground material and the fact that this literary world tends to be inhabited by (deviant) male characters, the resulting readership would be predominantly male. However, we discovered that our readers were not predominantly male, as focus groups and initial research had suggested.

Out of the 302 readers questioned, 46.7 percent were actually female. This large female reading base demonstrates that women, too, are finding something to like in the genre.Footnote 35 This gender balance in the readership might be due to the fact that the genre does contain several female writers who offer strong female characters and deal specifically with gender issues in Turkey. Compared to Turkish male underground writers, Turkish female underground authors were read less, but their numbers of readers were not negligible. Kanat Güner’s Eroin Güncesi, for example, was read by 17.9 percent of readers, Sibel Torunoğlu’s Travesti Pinokyo by 10.6 percent, and Ayça Seren Ural’s Pogo by 4.3 percent, as compared to küçük iskender’s poetry at 43.7 percent, Metin Kaçan’s Ağır Roman at 44 percent, and Hakan Günday’s Piç at 37.7 percent. Underground literature is still a male-dominated genre in terms of authors and themes, but these numbers demonstrate that the genre holds potential for female readers as well, a point worthy of further consideration as women’s issues take on increasing relevance in Turkey.

Most of our readers were from İstanbul, and most reading of underground literature occurs in the three largest cities of İstanbul, Ankara, and İzmir, though there are traces of the genre in eastern Turkey as well. We found readers in focus groups who had first encountered underground literature in Urfa and Tokat, and the publishers we interviewed, like Şenol Erdoğan of 6:45, did admit that even a few fans in Diyarbakır receive copies of his publishing house’s Underground Poetix. Nevertheless, underground literature tends to be an urban and western phenomenon.

Underground literature readers, in many ways, are very similar to the general population of İstanbul. However, one significant difference is their outlook on religion. Most underground literature readers do not consider themselves very religious. On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most religious, 48.7 percent of readers responded in the 0–4 category. In fact, when asked to specify their religion, 21.9 percent declared “none,” which was more than twice the amount of non-readers (10.8 percent). This was perhaps one of the most surprising discoveries concerning reader demographics that we encountered.

In addition to a study of the demographic make-up of underground literature readership, we were also very interested in discovering the sort of attitudes and opinions associated with underground literature’s fan base. As our initial research into the debate surrounding the genre conducted mainly in the journals Notos and Varlık revealed, there was a great deal of uncertainty as to the existence of the genre at all, with many critics believing that the term was just a “marketing gimmick” to sell copies. Marketing gimmick or not, we discovered that the majority of those reading the genre know exactly what they are reading. We had initially been led to believe that finding people who self-identify with the term “underground” would be difficult. The results, however, proved otherwise. A startling 78.1 percent of readers had heard of the genre before, while a significant 59.9 percent defined themselves as “underground literature readers.” Their level of reading is quite high. Not only are they voracious readers in general—half of the readers read at least 10 books last year—on average they have read 7 underground texts in the past year. In the interview stage, the most common statement made by our Turkish interviewees was that “Turks don’t read.” This is of course an overstatement, but our study shows that underground literature readers do read, and read a lot.

We also found that most of this reading is done in translation. Our study revealed that 60.9 percent of the readers read underground texts only in translation, while 31.5 percent sometimes read them in the original, with only 6.3 percent always reading the originals. Although most read in translation, the number of texts read in the original seems to us somewhat high, which can be explained by the fact that many of underground literature’s readers are university students who probably have some knowledge (and in some cases strong knowledge) of the English language.

What did not surprise us was the nature of the community formed around underground literature. Our analysis of underground literature’s internet presence indicated that there is a strong following among devoted fans. Most websites devoted to the topic are run by individual underground literature readers who employ their sites as a means to disseminate biographical information, photographs, and links to other pertinent underground literature sites. There is, then, a strong underground literature community on the internet which routinely shares information about their favorite authors and works. In addition, a number of critics and even writers, such as Altay Öktem, have a strong internet presence as well. The vast majority of the discussion is conducted in a celebratory manner, with occasional forays into controversial topics such as censorship and the Gezi Park demonstrations.

As its name implies, this genre shares much in common with the conception of a “subculture” as expounded in the literature by the theorists Hebdige, Hall and Jefferson, Huq, and Muggleton.Footnote 36 The reading of underground texts begins early and mainly involves friends. The majority of readers (57.9 percent) first heard of the term in high school, and their friends were generally the ones who introduced them to the texts (82.1 percent were so referred). This data was unsurprising, since many students in our focus groups were likewise introduced to underground literature in high school (though a significant number only encountered the genre at the university) and the vast majority had first heard of the genre through friends (see Appendix 3). Though they were all internet users and watched a great deal of television, it appears as though most of the discussion surrounding these texts and their acquisition is done through friendship networks. Underground literature is clearly a “word of mouth” phenomenon, as befits its “subcultural” nature.

Underground literature readers are, for the most part, a very liberal group. This makes sense, given the often provocative and challenging nature of underground texts. Politically, they tend to fall to the “left” of center (59.9 percent), though there were a significant number of extremely right-leaning respondents (7 percent). By comparison, the non-readers situated left of center amounted to 33.7 percent, while non-readers on the far right constituted 26.7 percent. Overall, the readers are a very “open” group, viewing women’s rights, foreigners, and minority groups with an open mind. For example, 89 percent agree that freedom of expression should be preserved under all conditions, while 66.6 percent support the idea that women should be allowed to wear headscarves in governmental institutions. 82.1 percent do not agree with the idea that education is more important for boys than it is for girls. The readers are a very tolerant group, though not more so than the non-readers in our study. They are, however, less conservative. Given that readers tended to seek “new perspectives” (yeni bakış açıları getirmesi) (17.4 percent), “rebellious feelings” (isyan duygusu) (14.5 percent), and “social injustice” (toplumsal adaletsizliğin konu edilmesi) (14.5 percent) from their underground literature reading experience, the fact that readers are more tolerant comes as no surprise.

One notable exception here are views expressed concerning homosexuality. Despite the fact that homosexuality is a theme in many (though mainly Western) underground texts, respondents were critical of it in practice: 16.9 percent are opposed to the idea of homosexuals living as one’s neighbors, whereas they were far more tolerant of other kinds of minority groups. While this is much lower than the non-reader group (27.1 percent), it is still high, especially when compared to their attitudes towards other minority groups. Only 2.6 percent (versus non-readers at 4.6 percent) are opposed to the idea of living next to Jews, Greeks, and Armenians, with a slightly higher 4.6 percent (versus 5.2 percent for non-readers) being opposed to dwelling near Kurdish people. Our interview with the publisher of the strongly heterosexual writer Charles Bukowski confirms this bias: sales for the heterosexually-focused Bukowski title Women, for example, exceeded 100,000 copies, which is a strong showing for any book in Turkey, and especially for an “underground” title. By comparison, Burroughs’ The Soft Machine, a strongly homosexual novel that has recently undergone an obscenity trial, sold a mere 5,000 copies. Clearly, the issue of homosexuality is still extremely taboo, and, despite willingness to question their beliefs, the readers are clearly uninterested in exploring this very delicate topic in Turkish society.

Responses to the passages given to non-readers reinforce the conclusion that homosexuality remains a delicate subject in Turkey. As stated earlier, non-readers were given eight passages (four by American underground authors and four by Turkish underground authors) and were asked to respond to five statements on a scale from disagreement to agreement: the text has literary worth, introduces worthy topics of debate, uses unsuitable language and is obscene, is not suitable for Turkish youth, and is unsuitable for women. The passages were selected in terms of the themes and problems they might raise, including anti-authoritative stances to society, women’s issues, anti-nationalist statements, stylistic innovations, questioning of family and collective values, and transgressive sexuality (including homosexuality). For these non-readers, the differences between Turkish texts and Western ones (passages included the author’s name as well as the work’s title) were not significant. Most found all the passages worthy of value and useful for introducing important topics and felt that they were not obscene, were suitable for Turkish youth, and should be read by women.

There were, however, notable exceptions. A passage by the Turkish poet küçük iskender that included reference to gay bars (gay barlar) was judged less positively in most categories than the rest of the passages. For instance, when asked to respond to the statement that the passage “contained literary value,” the response “entirely disagree” hovered at or below 10 percent for all the other passages, while for küçük iskender it was 28.4 percent. The same held true for the statement that the passage was “obscene,” with küçük iskender’s passage garnering double the rate of the other texts. Overall, non-readers were still basically positive about küçük iskender’s passage, yet the fact that they were less positive about it than they were about the other passages is telling. It is difficult to precisely know the cause of these results. küçük iskender’s passage also includes reference to several political parties and makes disparaging remarks about the army, which could account for such a response. The title of the poem is, after all, “Türkiye” (“Turkey”), and thus might have raised the ire of Turkish respondents who normally would not have found anything disagreeable with the text. Yet the second least favorable passage was from Allen Ginsberg’s poem Uluma (Howl), which also contained homosexual references: 15.4 percent agreed that it is “obscene,” as compared to the other passages at 6.2 percent (Hakan Günday), 8.8 percent (Jack Kerouac), 9.5 percent (Kanat Güner), 10.8 percent (both William S. Burroughs and Süreyyya Evren), and 9.5 percent (Chuck Palahniuk). Thus, it seems fair to conclude that while non-readers were overall very positive concerning the underground literary texts they were offered, homosexuality still remains the one issue raised by the genre that finds a (slightly) more difficult reception.

Readers of underground literature are, at the same time, more critical of the West. This came as a bit of a shock, as much of the genre is either direct imports from the West or Turkish writing that is oftentimes self-consciously inspired by such Western countercultural models. Surprisingly for this American researcher, the non-readers of our study were actually less critical of the United States and Europe: 62.1 percent of non-readers believe that the United States has a negative impact on Turkey, whereas among readers this percentage increases to 70.2 percent. In terms of Europe, 41.7 percent of non-readers believe European culture poses a threat to Turkey, while the number is slightly higher for readers, at 50.6 percent. This is best explained by the readers’ left-leaning political positions: as befits the Turkish left in general, readers of underground literature tend to be critical of the West while embracing its countercultural literature, a point that will be taken up again in the next section.

This critique of the West is even more surprising because underground literature’s readers tend to view Western underground texts more favorably than their Turkish counterparts. When asked to rank foreign versus domestic underground texts in terms of rebelliousness (isyankarlık), literary worth (edebi değer), optimistic outlook (iyimser bakış açısı), and pertinence to social issues (sosyal meselelere değinme becerisi), readers unanimously chose Western texts over Turkish ones. And while readers were most familiar with Turkish writers such as küçük iskender, Hakan Günday, and Metin Kaçan, American authors such as Chuck Palahniuk, Charles Bukowski, and Jack Kerouac were also very popular (see Appendix 4).

Readers of underground literature feel that the genre is important for Turkey. 26.5 percent believe its importance lies in opening new perspectives for readers (hayata yeni bakış açıları sunması), while 23.2 percent believe that underground literature is most important for allowing readers to question the perceptions and prejudices of society (toplumsal algıları ve ön yargıları sorgulatması). While, for some, style is an important consideration, most readers are looking to the genre for social reasons.

Perhaps most importantly, readers of underground literature are fairly positive about the future of Turkey. Our initial interviews with critics of underground literature suggested that the genre holds little potential to influence Turkey. Our findings, however, suggest otherwise: of our readers, 39.4 percent believed that reading underground literature has changed them, and 33.1 percent believe it holds a positive potential for Turkey, which is a clear indication that these texts are viewed as socially meaningful for their readers. Our initial interviews and literature reviews had tended to demonstrate the opposite, and even many of the publishers and editors of underground literature were reticent about its ultimate effectiveness in changing Turkey. But clearly, for readers, the genre does hold potential, on both a personal and a social level.

Conclusion

This study set itself the goal of examining the influence underground literature is having on Turkish youth. Our results indicate that this form of literature is certainly an important component in the lives of many young Turkish citizens. Turkish youth of both sexes are reading these works and finding something valuable in the process. While underground literature is by no means a general phenomenon in Turkey, for those that encounter this literature among friends and classmates its appeal is undeniable.

The rise of underground literature as a genre is inextricably bound to a sea change in Turkish society as a whole. As critics such as Demir, Lüküslü, and Neyzi have discussed, the 1980 coup stands as a benchmark for both Turkish society and youth studies.Footnote 37 This date was repeatedly echoed in interviews with publisher and editors (and even came up in a few focus groups) as a watershed moment in Turkish history when direct political conflict occurring “in the streets” was replaced by a new form of cultural critique. While a detailed discussion of this change is beyond the scope of this report,Footnote 38 suffice it to say that the importation and distribution of underground materials dates to this new era in Turkish society. As such, it represents a new mode of dissent, one that has undertones of collectivity but is overall deemed a more individualistic form of rebellion that replaces direct political action with “consciousness raising” and ideological demystification as its primary objectives.

Yet what exactly is the effect of such literature on Turkish young people’s attitudes toward the important topics of contemporary Turkey? The answer to this question is both subtle and complicated. As previously mentioned, underground literature’s readers are a mainly liberal and leftist group. However, it is difficult to determine whether reading underground literature caused their viewpoints to change or whether the genre appealed to them precisely because of its open and challenging nature. While almost half of the respondents reported that reading underground literature changed them and a substantial percentage cite the opening up of attitudes as an important contribution of the genre, it is difficult to determine whether underground literature was the (sole) cause of a shift toward the left or whether it simply reinforced existing beliefs. In any case, it is clear that, for those young people with liberal opinions, underground literature holds a strong appeal.

One thing underground literature appears not to be doing is changing attitudes about the West. This is an interesting result, since one would assume that reading and appreciating texts from the West would cause a corresponding increase in positive attitudes toward Europe and the United States. Not all underground texts are Western, but readers ranked Western underground literature higher than its domestic counterparts with regards to rebelliousness, literary worth, optimistic outlook, and the ability to address social questions. But readers seem to distinguish between politics and aesthetics. Despite this positive assessment, overall readers were critical of the United States and Europe, more so than their counterparts in the non-readers group. This might be explained by Western underground literature’s own critique of America and Europe: readers were clearly in agreement with the attack this genre wages on conformity and commercialism.

Ultimately, underground literature is a fairly marginal genre with a huge potential for influence. Given that it is generally disseminated outside the home among friends of the same peer group, as its name implies it enjoys an “underground,” subcultural status that will always appeal to that segment of youth culture interested in questioning the accepted tenets of society. Despite this challenging nature, readers were selective rebels, finding in underground literature viewpoints that reinforced some of their opinions while rejecting others, such as the positive views of homosexuality that many of these texts entertain. Underground literature is probably best thought of as a necessary outlet for Turkish youth, allowing them to explore controversial and taboo topics in private or within their peer groups. It is thus less a call for revolution than a means to open up readers to new viewpoints and possibilities that they may or may not ultimately accept.

As recently as 2012, İlkay Demir, in her article “The Development and Current State of Youth Research in Turkey: An Overview,” has claimed that “we have very limited knowledge of youths’ lives, experiences, identity constructions, and school-family-work transitions.”Footnote 39 This study has been an attempt to help remedy that situation. While no one study can singlehandedly explain the vast topic that is Turkish youth, we hope that we have elucidated a small yet significant aspect of the lives of Turkish youth; namely, their desire to question and confront. Given the recent events of Gezi Park, it is clear that Turkish young people are seeking change. Underground literature is clearly not the only avenue to explore such change, nor is it the most widespread, but it does have the potential to offer a diverse set of Turkish youth readers the chance to expose themselves to a different point of view. Given that no one wants to see a return to the sort of street violence that characterized the pre-coup years and seems to be erupting with some consistency today, the social critiques found in genres like underground literature offer a chance for rebellious ideas, thoughts, and concepts to be discussed openly and positively without the need for violence. And that, in the end, might be underground literature’s most effective legacy in Turkey.

Appendix 1

Graph and chart showing age distribution among readers and average age of first hearing about genre for both male and female readers

Report

How old were you when you first heard about underground literature?

Appendix 2

Chart and graph depicting where readers first became aware of the genre

Where did you first hear about underground literature?

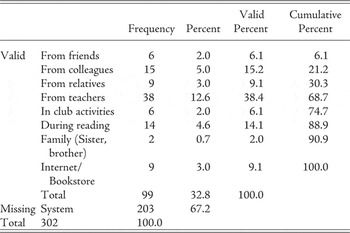

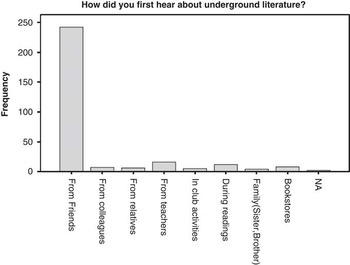

Appendix 3

Chart and graph depicting how readers became aware of the genre

How did you first hear about underground literature?

Appendix 4

Chart shown to readers to gauge familiarity with various underground texts and authors