Introduction

The Southeastern Anatolia Project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, GAP) is one of the largest regional development projects ever undertaken in Turkey. When GAP was officially initiated in 1977, the project aimed primarily at the construction of 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power plants (HPPs) on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, along with extensive irrigation networks, in order to produce hydroelectric energy and irrigate 1.8 million hectares (ha) of land in the Southeastern Anatolia Region (henceforth, the GAP region). The scope of the project has significantly widened over the ensuing decades. Development goals—such as improving agricultural and industrial production and efficiency in the region, improving the region’s socioeconomic standards, preventing migration from the region, and eliminating regional inequality in land ownership—have been added to the project agenda. Following this expansion, the multidimensionality of GAP and its multifaceted implications have become clearer. For instance, the project has created international controversies in regard to the Kurdish question and to water sharing among Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. It has also created domestic controversies regarding ecological destruction, the flooding of historical sites, and the displacement of local peoples in the GAP region. As a result, the project has become more visible and influential not only in political and public discourse, but also in the region itself. However, despite the increased visibility and impact of GAP, the question of how the project’s characteristics, vocabulary, rationales, and mechanisms have changed since its inception remains underdiscussed.Footnote 1

This article seeks to fill this gap and ask what GAP was in the past and what it has more recently become. It seeks to examine the gradual transformation of the project over the course of forty years, specifically taking into account the continuities and ruptures in development discourse, theory, and practice since the 1950s.Footnote 2 The article begins with a concise history of major development theories. This is followed by a brief background of the GAP region and the different stages of the GAP project, presenting the most significant developments within each stage. Finally, the article concludes with an overall evaluation.

Development in the post-World War II period

The post-World War II period marked the beginning of development as a political goal and a field of enquiry,Footnote 3 and development has ever since been associated with growth, change, and progress. In 1949, then United States President Harry S. Truman’s Point Four Program was announced via a speech that marked the division of the world into “underdeveloped” and “prosperous” areas.Footnote 4 The Cold War superpowers subsequently accorded a good deal of importance to promoting the development of “Third World” countries. States also took an interest in development so as to address the question of how the economies of the British, French, Portuguese, and other European colonies could be transformed and made more productive.Footnote 5 It was in the context of the demands of this new thinking that, in the 1950s, development theories began to emerge in order to meet those demands.

During the 1950s and 1960s, modernization theories proved exceptionally popular. At this time, economic growth was considered the antidote to “backwardness.” In a Keynesian manner, states came to play an active role in creating industrial capacity, extracting natural resources, improving agricultural efficiency, and implementing large-scale infrastructure projects.Footnote 6 Five-year development plans and development agencies were introduced in many developing and post-colonial countries.Footnote 7 Ever since this period, development has been based on the dichotomy between traditional and modern,Footnote 8 and has called for a transition from traditional to modern principles of social organization. Development, seen as a uniform process through which all societies pass, was assumed to be experienced primarily by Western societies, whereas the non-Western societies were assumed to merely replicate the Western development trajectory.Footnote 9 Elites were given a key role in the spread of modern values outward from the center,Footnote 10 and hence modernization came to include elements of elite-driven social engineering along with the interventionist ambition to shape economies and societies through dictating to others what they should do.Footnote 11

Structuralism has criticized modernization theories for their positivist orthodoxy, ahistoricity, traditional/modern dichotomy, silence on inequality, and Western-centrism.Footnote 12 In the 1970s, the convergence of Marxism/Neo-Marxism and structuralism prompted the emergence of dependency theories.Footnote 13 These argued that poverty in the “Third World” is a result of exploitation by industrialized nations and their imperialist policies.Footnote 14 The argument was that colonization prevented the colonized from developing their industries because the profits that would normally contribute to growth were instead siphoned off to colonial powers.Footnote 15 As such, the development of the “First World” was fundamentally dependent on the underdevelopment of the “Third World.” Given these obstacles created by the global capitalist system, it has been asserted that, within such a system, the improvement of developing countries is either impossible or, if governments are allowed to possess full autonomy in directing their development processes, only somewhat possible.Footnote 16

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the tide turned and developmentalism began to fall out of favor. Import substitution industrialization began to be marked as corrupt protectionism, financial aid as money spent in vain, and governments as barriers against entrepreneurship.Footnote 17 Such perceptions decreased trust in government intervention while increasing expectations in freely operating markets. It was in this context that, in the 1980s, neoliberalism emerged as the hegemonic development approach. Many countries subsequently came to embrace privatization, deregulation, free trade, and foreign investment, while major development institutions like the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) began to impose neoliberal reforms onto developing countries, forcing them to pursue structural adjustment programs. Since the 1990s, “getting the institutions right” has been emphasized under the rubric of “good governance,” and this in turn has led to the introduction of numerous institutional imperatives meant to achieve successful development on a universal scale.Footnote 18 Capacity building, public-private partnership, community involvement, and public responsibility also began to be emphasized as preconditions of development.

In the 1980s, the discourse of development reached an impasse that accompanied the process of increasing liberalization. Development began to be intensely criticized for being biased, exogenously imposed in a “one-size-fits-all” manner, insensitive to social forces, destructive to the environment, and technocratic rather than participatory.Footnote 19 There have been attempts to overcome such deficiencies and find alternatives of development, with some of the major alternative perspectives being the introduction of gender into development in the 1980s, the emergence of the notion of “sustainable development” in 1987, the release of the Human Development Index in 1990, and the rise of participatory approaches in the 1990s and their inclusion into development practices.Footnote 20

Around the same time, it also began to be claimed that development had “become outdated.”Footnote 21 These critical insights and calls for alternatives to development have come to be known as post-development approaches. Post-development is influenced by the works of Michel Foucault, by the linguistic turn in the social sciences, and by post-structuralism.Footnote 22 According to this perspective, development is “a top-down, ethnocentric, and technocratic approach, which treat[s] people and cultures as abstract concepts, statistical figures to be moved up and down in the charts of ‘progress.’”Footnote 23 It is both an instrument of economic control over “Third World” countries and a mechanism through which they are imagined and marginalized.Footnote 24 Development discourses allow the West to portray itself as “civilized” while portraying others as “backward.”Footnote 25 Such discourses, the new paradigm claims, also depoliticize contested issues and turn political problems into technical problems to be “neutrally” managed by experts. For these reasons, this paradigm proposes that the idea of development must be abandoned, or at least left to itself to disappear naturally.

The evolution of GAP

The GAP region

The GAP region includes the provinces of Adıyaman, Batman, Diyarbakır, Gaziantep, Kilis, Mardin, Siirt, Şanlıurfa, and Şırnak and encompasses around 10 percent of Turkey’s total surface area and population. It includes large plains such as those of Harran, Suruç, Ceylanpınar, and Mardin, as well as vital rivers like the Tigris and Euphrates. Approximately one-fifth of the total irrigable land and one-third of the energy potential of Turkey are located in the region.Footnote 26 The region ranks above the national average in terms of annual population growth rate, fertility rate, average household size, infant mortality rate, and unemployment rate. However, it performs below the national average in terms of urbanization rates and average gross value added per capita.Footnote 27 Even though migration, urbanization, and the transformation of large landowners into capitalist farmers have eroded local tribal social organizations, these are not yet completely dissolved, especially in rural areas.Footnote 28 Inequality in terms of land ownership is widespread: approximately 65 percent of farmers own around 10 percent of the land, while around 10 percent of the landowners own around 65 percent of the land.Footnote 29 The population in the region is ethnically heterogeneous: one survey indicates that 50.9 percent of the population in the region speaks Kurdish, 34.2 percent speaks Turkish, 9.4 percent speaks Arabic, and 5.5 percent speaks Zazaki.Footnote 30 These distinct characteristics are a significant part of the reason why the region has been selected as a space of intervention.

GAP as a water and land resources development project: 1970s–mid-1980s

The idea of constructing a dam and an HPP on the upper Euphrates dates back to the 1930s, when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the republic, introduced the idea based upon his fascination with the Soviet Union’s plans for the Dnieper.Footnote 31 While the Electrical Power Resources Survey and Development Administration (Elektrik İşleri Etüt İdaresi) conducted studies to this end in the 1930s and 1940s, the idea was only translated into concrete plans after the establishment of the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (Devlet Su İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü, DSİ) in 1954.

Initially, GAP was planned by the DSİ as a combination of 13 projects on the Tigris and Euphrates aiming at water resources development, irrigation, and hydropower generation. In 1964, the DSİ formulated the Reconnaissance Report for the Euphrates Basin, projecting the construction of two dams and two HPPs on the river mouth of the Keban Dam.Footnote 32 The construction of the Keban Dam was initiated on the Euphrates in 1966. In 1968, the DSİ formulated the Reconnaissance Report for the Tigris Basin, projecting the construction of 20 dams and 16 HPPs.Footnote 33 Modifications were made after the 1973 oil crisis in order to increase the energy production capacity and the amount of the land to be irrigated. In 1975, Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel emphasized how these plans were among “the special plans [meant] to develop the eastern and southeastern regions,” describing the plans as follows:

This project is about building four dams to generate 20 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity in the 200-kilometer-long area between Keban and Birecik on the Euphrates, and transferring nine billion kWh of this 20 billion to a 21-kilometer-long tunnel through a pumping station to be built in Bozova in Urfa to reach the Harran Plain over Urfa […] The Karakaya and Karababa dams are the second and third stages of this project.Footnote 34

In 1977, the number of dams and HPPs to be built were modified again. Eventually, all the projects for the Tigris and Euphrates were merged together and renamed GAP.Footnote 35

The dominant expectation was that GAP would quickly solve the socioeconomic and sociopolitical problems of the region. For instance, as early as 1975 Ömer Naimi Barım, a member of parliament representing Elazığ, emphasized the need to accelerate “public investments and implementation of infrastructural, industrial, husbandry, and irrigation projects” in order to “immediately save these regions from backwardness.”Footnote 36 Similar expectations remained largely intact in the 1980s. In this regard, in 1984 Saffet Sert, a member of parliament for Konya, explained the prospects of GAP as follows:

When GAP is completed, large areas of land in southeastern Anatolia will become as fertile as they are in Çukurova […] 16 billion kWh of energy, equal to half of Turkey’s current production, will be produced by the Atatürk and Karakaya dams […] Putting these projects into operation will change the face of Turkey. It is the greatest step toward realizing the legend of the economically “strong Turkey” of which we have dreamed.Footnote 37

From the mid-1980s onward, the limited technical focus of GAP, primarily on water and land resources development, began to change. In the words of a former deputy undersecretary from the State Planning Organization (Devlet Planlama Teşkilatı, DPT), GAP’s coverage widened so as to “transform sectoral planning into multisectoral and spatial planning and link it with a regional plan” because “the socioeconomic structure of the region would change after technical infrastructural investments.”Footnote 38

GAP as a multisectoral and integrated project: mid-1980s–1989

In 1986, the DPT replaced the DSİ as the new coordinator of GAP and began to implement a number of institutional changes so as to better administer the project. Various units were established within the DPT—among them the Undersecretarial Research and Project Promotion Group (Müsteşarlık Araştırma Grubu, MAG), the Project Management Unit (Proje Yönetim Birimi), and the Southeastern Anatolia Project Group (DPT Müsteşarlık Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi Grup Başkanlığı)—and given such responsibilities as determining the priorities of infrastructure establishments, using resources efficiently for plans and programs, and facilitating the planning and implementation of regional development.Footnote 39 Moreover, industrial, transportation, social, and related sectors were also included in the project. One expert from the GAP Regional Development Administration (GAP Bölge Kalkınma İdaresi, GAP-BKİ) explained this need in the following manner:

Irrigation automatically triples farmers’ income. First, farmers expand their cropping patterns and start producing agroindustrial goods […] Second, industries flourish thanks to these goods and raw materials and, therefore, labor requirements arise […] Urban transformation occurs. [Therefore], individual, societal, and urban capacities should be expanded in order to avoid infrastructural and social problems.Footnote 40

Politicians supported these changes, too. For example, Hikmet Çetin, a member of parliament for Diyarbakır, emphasized in 1988 that his party conceived GAP not “solely as an engineering project,” but rather as “an integrated, broad regional project that can change the destiny of the whole region.”Footnote 41 Erdal İnönü, a member of parliament for İzmir, reiterated that GAP “is not solely an energy production and irrigation project. This project must be evaluated as a whole with its economic, social, and cultural contributions.”Footnote 42

The formulation of the GAP Master Plan and the establishment of GAP-BKİ in 1989 had a powerful influence on the subsequent trajectory of the project. For the first time, the GAP Master Plan identified environmental, human, and financial resources as “critical” resources requiring development in addition to water and land resources.Footnote 43 The plan’s designated objectives are shown in Table 1:Footnote

Table 1 Development objectives of the GAP Master Plan44

The fundamental scenario was to transform the GAP region by 2005 into an agro-related export base in three phases: preparation for take-off, economic restructuring and accelerated growth, and stable and sustained growth.Footnote 45 The region was expected to become “one of the growth and industrialization centers of not only Turkey, but also the whole Middle East.”Footnote 46 To this end, three alternatives were proposed: alternative A prioritized irrigating all planned areas by 2005, alternative B prioritized maximizing power generation and actualizing priority irrigation projects by 2005, and alternative C prioritized implementing only priority irrigation and hydropower schemes by 2005.Footnote 47 Due to public finance constraints, alternative C was adopted as a framework. Accordingly, it was projected that GAP would be completed at a total cost of USD 32 billion by 2005.

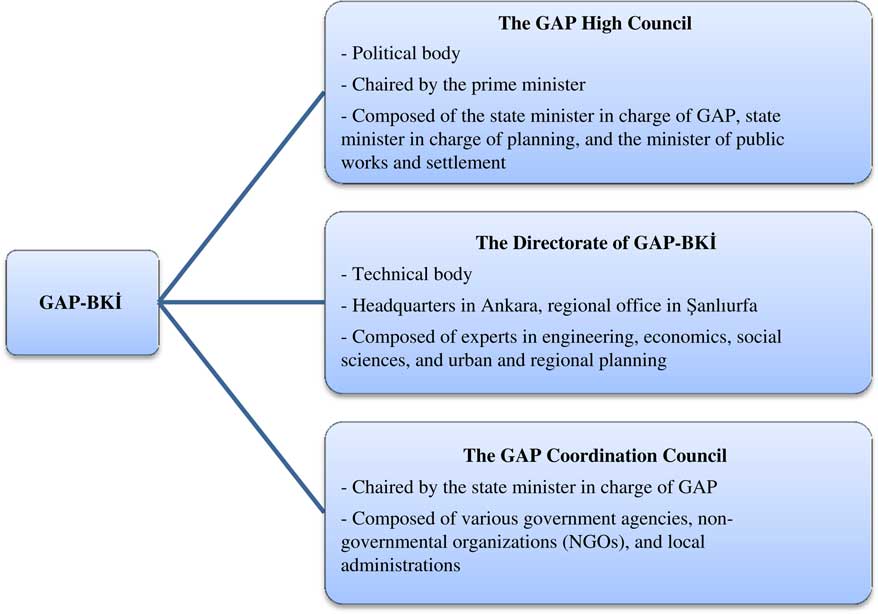

The DPT’s organization and internal dynamics led to a need to administer GAP in a different manner, as the organization consisted of three bodies dealing with (1) social and economic planning, (2) coordination among different sectors, and (3) the implementation of investments operated at the level of the deputy undersecretary and under the supervision of the DPT’s undersecretary. However, MAG also operated under the supervision of the undersecretary and was made responsible for conducting research on critical sectors and for providing consultancy to the undersecretary. The DPT developed a top-down, three-stage planning approach that involved macro, sectoral, and project levels.Footnote 48 Yet it lacked regional or local organizations, and this organizational structure created problems because GAP grew too comprehensive to be administered exclusively under a rubric of social or economic planning and through sectoral and centralized planning. Due to such incompatibilities, GAP came to be seen as a research topic in and of itself, and was delegated to MAG. However, as a former deputy undersecretary for the DPT explained, over time “experts from the DSİ, mining engineers, chemical engineers, city planners, and sociologists joined MAG,” which created another ambiguity.Footnote 49 Based on the anticipation that a separate administrative body with relative autonomy could prevent further problems, GAP-BKİ was established in 1989.Footnote 50 (See Figure 1 for the organizational structure of GAP-BKİ.) According to Abdülkadir Aksu, the Minister of the Interior (İçişleri Bakanı) at the time, GAP-BKİ was founded in order to:

rapidly develop territories under GAP’s coverage; deliver planning, infrastructure, licensing, housing, industry, mining, agriculture, energy, transportation, and other services so as to realize investments or have them delivered; take or have taken required measures to raise the education level of the local population; and ensure coordination among agencies and organizations.Footnote 51

Figure 1 The initial organization of GAP-BKİFootnote 52

Since its inceptionFootnote in 1960, the DPT had been the primary state actor in relation to public investments. It prepared five-year development plans underlining the priorities and strategies of all public investment institutions.Footnote 53 These plans were then implemented through annual investment programs also prepared by the DPT, with the plans being reviewed by the DPT’s High Planning Council and approved by the republic’s Council of Ministers (Bakanlar Kurulu).Footnote 54 Within this framework, the GAP High Council was devoid of the authority to make decisions related to investment and resource allocation. The DPT’s High Planning Council was separate from both GAP-BKİ and from the GAP High Council, and the government minister in charge of GAP had never been included as a member of the High Planning Council. Therefore, GAP-BKİ’s role remained confined primarily to coordinating and monitoring state institutions and providing advice to governments regarding investments via the GAP High Council. The implementation of projects was a subsidiary task, but due to its limited budget, GAP-BKİ implemented projects only when it received funds from other governments, intergovernmental organizations, international institutions, or philanthropist foundations; among those who thus provided funds were the government of Japan, the European Union (EU), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the Packard Foundation.Footnote 55 GAP-BKİ thus “remained an outsider institution with limited influence on the overall planning and implementation systems and structures.”Footnote 56

GAP in limbo: 1989–1993

From 1989 onward, it has been widely emphasized that GAP included not only dams and irrigation schemes, but also “agriculture and transportation infrastructure facilities, urban and rural infrastructures, investments in industry, commerce, health, education, housing, and services.”Footnote 57 This, however, was not in fact the case. As explained by a former deputy undersecretary for the DPT, “even though the DSİ’s former engineering, infrastructure, energy, and irrigation project became an integrated project, [the government] poured every dime into the Atatürk Dam […] The planning project once again became an engineering project.”Footnote 58 Politicians also raised concerns. Celal Kürkoğlu, a member of parliament for Adıyaman, said in 1992 that “irrigation infrastructure and irrigation canals have been neglected” and “GAP has been dealt with in its economic and technical aspects, [but] not in its social aspect.”Footnote 59 According to a former DPT employee, one important reason for this situation was that the Minister of Public Works and Housing (Bayındırlık ve İskan Bakanı) was more powerful than the other ministers on the GAP High Council.Footnote 60 Since the DSİ was under this ministry’s supervision, more importance—and, allegedly, resources as well—was accorded to dam and infrastructure projects as compared to agricultural projects.Footnote 61 It was amidst these ongoing discussions that the GAP Region Action Plan of 1993–1997 was formulated. This plan aimed to increase the level of investment and income in the region; to improve health, education, transportation, and infrastructure services in urban and rural areas; to increase employment opportunities; and to address other similar socioeconomic problems.Footnote 62 In particular, the plan aimed to rectify the gaps left by the earlier GAP Master Plan.

GAP as a sustainable human development project: 1994 onward

This period has marked a “radical reorientation towards a regional people-focussed rather than water-oriented development project” and has witnessed efforts “to propel the region, seen as backward, in terms of education, agricultural practices, gender relations, environmental conditions, and participation.”Footnote 63 In the words of one coordinator from GAP-BKİ, “sustainable development, participation, social development, and human-centered development became the essential principles of GAP,” especially after a seminar organized by GAP-BKİ and the UNDP was held on the subject of sustainable development and GAP in 1995.Footnote 64 Global events such as the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, and the World Summit for Social Development in 1995 also facilitated the inclusion of such concepts into GAP.Footnote 65 This pursuit required collaboration between “anthropologists and sociologists working at the micro level [and] economists and irrigation technologists at the macro level in order to achieve a result which [would make] optimal use of both physical and social features of the GAP region.”Footnote 66

The then president of GAP-BKİ, Olcay Ünver, noted around this time that the “human” was always at the center of sustainability, whether as an object or as an agent, or both.Footnote 67 The essential elements of sustainability within GAP were the inclusion of the poor into the development process (i.e., equity and fairness); the active participation of the local population, local administrations, and voluntary organizations in decision-making processes (i.e., participation); and the provision of minimum standards to everyone for a humane and secure life (i.e., human resources development).Footnote 68 This paradigm shift necessitated not only that those involved “produce knowledge about the sociocultural structure of the region and people’s expectations and inclinations,” but also that they “develop concrete action plans in the light of this knowledge to be shared with the implementing institutions.”Footnote 69 To achieve this, a number of studies were conducted between 1992 and 1994, among them the Management, Operation, and Maintenance Project Socioeconomic Studies; the Survey on the Trends of Social Change in the GAP Region; Population Movements in the GAP Region;Footnote 70 the Survey on the Problems of Employment and Resettlement in Areas Affected by Dam Lakes in the GAP Region; and Women’s Status in the GAP Region and Their Integration into the Process of Development. Based on these studies, the GAP Social Action Plan was formulated in 1994. The plan aimed to ensure participatory social development, to strike a balance between technical and economic projects and human resources, and to include disadvantaged groups into the development process.Footnote 71 One former coordinator from GAP-BKİ emphasized that “the social aspect of GAP had been missing in the GAP Master Plan, but subsequent plans, especially the GAP Social Action Plan, always included the social aspect.”Footnote 72 According to an expert from GAP-BKİ, this new plan was necessary because “it is easier to solve problems in engineering [while] [s]ocial events are different. Social intervention is mandatory to equalize different levels.”Footnote 73 There were also additional projects carried out during this period on the reuse of irrigation return water, on land consolidation and extension activities, on participatory resettlement, on the rehabilitation of street children, on the re-relocation of displaced people to their villages, and on public health, biodiversity, environmental education, and archaeological sites.Footnote 74

Four major developments merit special attention in regard to GAP’s transformation. To begin with, in 1995 Multipurpose Community Centers (Çok Amaçlı Toplum Merkezleri, ÇATOMs) were established. As a former coordinator from GAP-BKİ explained, these were “modeled on community centers from around the world, but adjusted to Turkey’s and the region’s context. [They] targeted women and target groups of high priority in order to prompt their further participation in social and economic life.”Footnote 75 The ÇATOMs’ objectives included raising women’s awareness about their problems, increasing their participation in the public sphere, enhancing their levels of employment and entrepreneurship, and empowering them toward a more gender-balanced development.Footnote 76 Numerous programs and activities on health, education, entrepreneurship, social support, and culture were carried out in order to achieve these objectives. The ÇATOMs were run by committees consisting of trainers selected from among the local population because, in the words of one expert from GAP-BKİ, “promising women with high leadership skills from the region […] know [more] about the local dynamics and social fabric.”Footnote 77 The ÇATOMs were also, however, criticized on the basis of their objectives and implications. For instance, it has been argued that they actually exploited women to provide the labor market with a cheap, unqualified workforce. Similarly, a sociologist criticized ÇATOMs for becoming “a structure where the focus is always on women’s household labor” and for “justif[ying] gender roles.” In her view, even though the ÇATOMs may have “taught women how to read and write, handicrafts and so on, [and though] some women have become small entrepreneurs, these are small gains in terms of women’s empowerment.”Footnote 78 A former coordinator from GAP-BKİ also criticized the operation of the ÇATOMs in the following terms:

Thanks to an established system and infrastructure, things somehow work. But we cannot move beyond this. We cannot quite ensure women’s participation in the economy and income-generating activities and raise their awareness. Our efforts are limited to courses on literacy, computer usage, sewing, hairdressing. In terms of marketing, empowerment, organization … we have not achieved much.Footnote 79

Another important development during this period was the increase in environmental and cultural awareness. Sustainability had not been altogether neglected in the initial stages of GAP. In the GAP Master Plan, it was acknowledged that “economic growth in any region, especially under severe natural conditions, cannot be sustained without having concomitant proper management of the environment.”Footnote 80 It was recommended that an environmental impact assessment should be initiated, and that greater efforts should be made to address problems concerning erosion, waterlogging, salinization, climatic change, and waterborne diseases.Footnote 81 In this regard, a former president of GAP-BKİ explained that since planning necessarily features such principles as rationality, functionality, integrity, sustainability, and continuity, “sustainability is inherent in planning anyway.”Footnote 82 Nevertheless, one coordinator from GAP-BKİ emphasized how “economic objectives were prioritized in planning” during the early 1990s. Accordingly, “environmental sensitivities and concerns regarding the conservation of cultural heritages were taken into consideration” only in the second half of the decade.Footnote 83 During this period, GAP-BKİ not only implemented projects on the environment, biological diversity, and culture, but also urged other state institutions to embrace sustainability. In the words of a former coordinator, GAP-BKİ told “other institutions that [they] should not look at [GAP] solely from a technical lens, that there is a social aspect, an environmental aspect,” and in this manner “changed their vision.”Footnote 84

The manner through which problems concerning the displacement and relocation of local people were handled also changed after the mid-1990s. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Keban Dam had “deprived the local communities of their means of production and dislocated them from their former sociocultural milieu. While compensation was paid, it hardly reached the ones most in need.”Footnote 85 In the 1980s, the Atatürk Dam led to the submergence or semi-submergence of three towns, four townships, and 135 villages, and 55,000 people were displaced.Footnote 86In contrast, when many villages were flooded and around 30,000 people were displaced by the Birecik Dam in the 1990s, a Resettlement Action Plan was formulated in order to provide people with assistance. Moreover, between 1997 and 2000, GAP-BKİ, the UNDP, and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) carried out a participatory project relating to the resettlement and employment of people and their employment. One professor involved in the project explained that they “moved a whole town to a new location” after asking the local communities what they wanted and needed.Footnote 87

Another significant development during this time was the increase in the emphasis placed on private sector investments, a development that ran in parallel to the neoliberal transformation of the Turkish political economy in the 1980s. The liberalization and deregulation of the energy sector, the privatization of irrigation water management, the establishment of irrigation associations, the introduction of the build-operate-transfer (BOT) model, and similar changes all influenced the trajectory of GAP.Footnote 88 In the late 1980s, the argument being formulated was that “GAP will create a myriad of business opportunities which in turn will necessitate a wide range of financial services. The full potential of GAP can only be realized through foreign and local investment.”Footnote 89 Similar ideas gained greater currency in the 1990s. In 1991, the establishment of an economic development agency was proposed, which would support industrialization based on private entrepreneurship, improve the region’s business and investment environment, and increase the technology, efficiency, and competitiveness level of regional industries.Footnote 90 Similarly, in 1996 the president of GAP-BKİ reiterated that “the role of the state is gradually diminishing in the development process in southeastern Anatolia […] Private investments must be the real engine of development.”Footnote 91 In 1997, GAP Entrepreneur Support Centers (GAP Girişimci Destekleme ve Yönlendirme Merkezleri, GAP-GİDEM) were established to provide consultancy services to foreign and domestic entrepreneurs and investors. GAP-GİDEM also sought to prevent capital from flowing outside the GAP region. One former coordinator from GAP-BKİ explained the rationale behind this objective as follows:

Irrigation systems in Urfa had a terrific impact on the change […] [People] made huge amounts of money. First, they experienced a “richness crisis.” They married their second, third wives. They went to nightclubs (pavyon) in Gaziantep. They bought cars. The money was spent for nothing. That was the reason for us to establish GİDEM: […] we thought about channeling this capital toward investment.Footnote 92

The final development in this regard was the formulation of the GAP Regional Development Plan in 2002. In 1998, it had become clear that GAP could not be completed by 2005 as a result of economic crises, political and military conflict in general and the activities of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, PKK) in particular, and the changing sociopolitical landscape of the GAP region throughout the 1990s.Footnote 93 After the Committee of Interministerial Implementation and Coordination decided upon the completion of GAP by 2010, the idea of coming up with a new plan emerged.

“Globalization, new development approaches, and international relations” were cited as the major reasons behind the new plan.Footnote 94 One project coordinator from GAP-BKİ also explained that the plan was formulated because “projects that looked right from an engineer’s perspective totally changed in reality when [they] were discussed with the people and when their social and cultural structures were taken into consideration.”Footnote 95 The new plan sought to “increase income and welfare through protecting and enhancing environment and resources based on the principles of equity and fairness; to consider and integrate disadvantaged groups into development; and to ensure sustainability and private sector and public participation at all stages.”Footnote 96 This plan was also participatory. A former coordinator from GAP-BKİ explained the plan’s preparatory process in the following manner:

We delegated studies directly to NGOs […] For example, something about health. We went to Diyarbakır. We told the Chamber of Doctors, “We are withdrawing. You formulate GAP’s health policy. Then we pass your framework along after working with the technical group and the state.” […] These were nice, bottom-up works.Footnote 97

However, this plan was ultimately never put into practice, partly because of the emergence of new development concepts that entered into the GAP framework on the heels of Turkey’s EU membership process. At this point, the project’s trajectory took yet another turn.

GAP as a market-based project: 2002 onward

After assuming EU candidate status in 1999, as a condition of potential full EU membership Turkey became obliged to change its conception of regional development and formulate a national policy aimed at reducing regional disparities. The state made attempts to implement these changes so as to receive from the EU financial assistance, incentives, and funds for regional development purposes.Footnote 98 For instance, it was through EU funding that the GAP Regional Development Program was initiated. This program aimed primarily to enhance the capacities of local small- and medium-sized enterprises, to support local and foreign entrepreneurs and investors, and to prepare a cultural heritage strategy. In connection with this, one former coordinator from GAP-BKİ indicated that the EU “created a conceptual awareness of production techniques, markets, material values of production […] Projects are based on participation, sustainability. They emphasize the environment and women. [Thus] EU grants and credit supports have made a significant difference.”Footnote 99

Another EU-induced change was the adoption of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) classification in 2002. This was done in order to formulate regional development policies, collect regional data, and create a comparable statistical database that would be in accordance with the EU regional statistics system. Turkey was divided into 12 NUTS I, 26 NUTS II, and 81 NUTS III regions.Footnote 100 The idea of making local potential the engine of development gained currency during this period. Instead of concentrating only on the GAP region, it was proposed that development projects should be spread throughout Turkey. Abdüllatif Şener, the deputy prime minister at the time, had this to say:

[We] have 81 provinces and GAP-BKİ covers only nine provinces […] However, all countries are in international competition. Countries that fail to compete [and] mobilize the country’s full potential at a maximum level will decline and drift away from competition. Hence, all the development potentials of the entire country should be mobilized.Footnote 101

The law meant to establish regional development agencies in the 26 NUTS II regions entered into force in 2006. These agencies’ primary goals were to attract investment for regional development purposes, to connect public and private sectors, and to lead to greater NGO participation in the development process.Footnote 102 For Şener, the agencies represented a model in which “the logic of the private sector comes into play.”Footnote 103 A sociology professor also confirmed this claim: “GAP was not a priority for the government [between 2002 and 2007]. The priority was the development agencies […] The logic was this: ‘Why would we block private sector? Let them do [the work]. We need to take risks to develop.’”Footnote 104 Competitiveness was accorded a great deal of importance during this period. Previously, “local entrepreneurs of the GAP region” had been seen as “extremely prudent,” “reluctant and scared of cooperation,” “narrow-minded and short-sighted,” and “inexperienced.”Footnote 105 In 2007, the Competitiveness Agenda for the GAP Region was prepared so as to transform the GAP region into “a new, value-added economy” based on the identity of “the cradle of sustainable civilization,” thereby rebranding with a positive international image, sustainable agriculture, “clean tech” manufacturing, and innovative service industries.Footnote 106 The agenda’s goal was to inject into GAP principles like competitiveness, risk-taking behavior, regional distinctiveness, and multilevel partnerships.

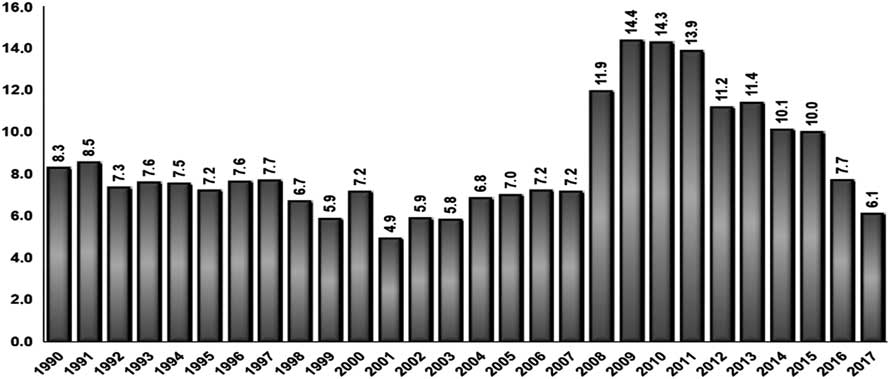

The GAP Action Plan (2008–2012) was formulated based largely on such ideas as these, which were also presented within the scope of the Competitiveness Agenda and the Ninth Development Plan (2007–2013). In the words of a coordinator from GAP-BKİ, this new GAP Action Plan was “a comprehensive package with a budget of 27 billion Turkish liras, 21 billion of which would be spent from public funds and the rest from other mechanisms, such as BOT.”Footnote 107 The main objective of the plan was to accelerate the project’s schedule and have it completed by 2012. The increase in the share of public investments allocated to GAP after the introduction of the plan is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Share of public investments allocated to GAP (1990–2017) (%)Footnote 108

Footnote The plan included four major development axes: economic development, social development, infrastructure building, and institutional capacity building.Footnote 109 The plan also introduced several novelties. For instance, the Social Support Program (Sosyal Destek Programı, SODES) was initiated with the expectation of enhancing human capital and social cohesion through employment projects, including disadvantaged groups in social and economic life, and integrating youth and women into society via cultural and sporting activities.Footnote 110 A deputy undersecretary from the Ministry of Development (Kalkınma Bakanlığı) explained the logic behind SODES as follows:

The government was using an expression like “social restoration.” Even though there is no such expression in the literature, we interpreted it and designed a program toward this goal […] Economic and social development must go hand in hand […] It is a program designed to bring mobility and vitality by providing support for social inclusion, culture, arts, sports, and employment projects.Footnote 111

Another novelty was the establishment in 2008 of the Dicle, Karacadağ, and İpekyolu regional development agencies in Mardin, Diyarbakır, and Gaziantep, respectively. In this regard, the head of one department in the Ministry of Development said the following:

Agencies played an active role in bringing local contributions into the process […] Even a man in the remotest town says the agency would come and ask his opinion. This is also an important public relations activity in the region. We would not have gone as deep in another region, but here there is such a need. People are glad to be heard. They think, “The state has come here.”Footnote 112

In this sense, the agencies extended the state’s visibility and reach in the GAP region rather than strengthening local administrations and contributing to decentralization.Footnote 113 The agencies functioned largely as extensions of the central government, and in this regard it is telling that the heads of their administrative boards are governors, with no other board member, including the secretary-general, able to be superior to governors. One former coordinator from GAP-BKİ has criticized this mechanism:

Agencies are established at a local level, but administered by governors who reside in these cities for only a limited time and know little about the local dynamics apart from their bureaucratic services […] Agencies are like the branch offices of the DPT in the region. Everything is approved and investment priorities are determined by the DPT in Ankara.Footnote 114

The relocation of GAP-BKİ’s headquarters from Ankara to Şanlıurfa in 2009 was another novelty.Footnote 115 There are, however, conflicting opinions about this decision and its outcomes. For instance, a member of parliament representing Şanlıurfa supported the decision because “GAP-BKİ has been like the sole authority for giving permission to all kinds of works within the nine provinces. [After the relocation,] nobody has to go to Ankara from the GAP region just for a signature anymore.”Footnote 116 Similarly, according to a deputy undersecretary from the Ministry of Development, “it is not a wrong decision considering the logic behind the GAP Action Plan […] The goals to be achieved within five years were very ambitious […] Therefore, these had to be done in the local environment, in their own place.”Footnote 117

In contrast, one expert from GAP-BKİ described the relocation as “a disaster for the administration, for the region, and for employees” because:

GAP is part of a centralist system. We have a regional directorate in Urfa. All the ministries are in Ankara. We were organizing meetings, intervening in investment programs, setting priorities. The regional directorate was doing its job there. Coordination meetings were really systematic. The relocation did not provide any benefits.Footnote 118

Similarly, a coordinator from GAP-BKİ shared her experience as follows:

We were suddenly told to go to Urfa. After we went there, our families were split apart. We experienced a “staff slaughter.” We lost at least 70 regional development experts. The new staff is predominantly new graduates. They do not have experience even in their own fields, let alone in regional development. How can you run a project of this scale under these conditions?Footnote 119

In summary, in the words of a former coordinator from GAP-BKİ, these developments illustrate that:

Decentralization is just a myth. If you do not have the authority, it does not matter whether you are in Urfa or Ankara. Decisions are made here [in Ankara]. A regional development administration must make financial allocation according to the plans within its jurisdiction […] In their current forms, they are nothing but the extension of central authority.Footnote 120

GAP as the “new GAP”: 2012 onward

Despite the ambitious goals of the GAP Action Plan, GAP was unable to be completed in 2012. The Minister of Development at the time, Cevdet Yılmaz, christened the post-2012 period as “the new GAP era” when he said that “the old GAP is closed and the new GAP is opened.”Footnote 121 GAP-BKİ emphasized how “in the classical sense, GAP is in the process of finalization.”Footnote 122 Similarly, a member of parliament representing Şanlıurfa underlined how, through 2012, “money had been spent on dams or large canals and buried in the ground without getting any returns. The next five years will be the years when GAP will provide returns and citizens will experience GAP directly.”Footnote 123 That is to say, there is a tendency to consider post-2012 GAP as a project distinct from pre-2012 GAP.

It was within this context that the GAP Action Plan of 2014–2018 was formulated. Although this plan has been formulated for the “new GAP,” it actually shares numerous similarities to previous plans. For instance, its overarching goal is the completion of the projects and investments proposed in the previous action plan. The new plan was prepared with participatory methods in mind. It was also influenced by the Tenth Development Plan (2014–2018) and the National Strategy for Regional Development (2014–2023). With the new plan, “increasing the livability of cities” was added as the fifth development axis to the already existing development axes specified in the previous plan.Footnote 124 In this sense, then, the two project constructs have actually merged rather than diverging. Yet regardless of how GAP is now defined, official figures indicate that 74 percent of the energy projects and 26.4 percent of the irrigation projects under the GAP umbrella have been completed as of 2016.Footnote 125

A bird’s-eye view of GAP

GAP defies easy labels and simple distinctions such as that between “the old” and “the new.” Analysis of how GAP’s designers and implementers—that is, the project authorities—have perceived the project since its inception proves a better illustration of the project’s multifaceted features and recent state. Between 1975 and 2015, GAP was narrated under six major categories: (1) characteristics of the GAP region; (2) characteristics of GAP; (3) objectives of GAP; (4) drawbacks of GAP; (5) factors behind the delay of GAP; and (6) factors behind GAP’s loss of popularity.

The GAP region has been perceived as an arid and barren, backward and underdeveloped, discriminated and neglected, and feudal and unjust region—but also as resourceful, diverse, and full of potential. The region has been associated with low rainfall and extreme temperatures, low socioeconomic standards, a low level of education, discrimination against the Kurds, and unequal land ownership. However, it has concurrently been associated with abundant land, water, and human resources and potential.

The GAP project itself has been perceived in diverse ways. It has been seen as a long-established, massive, vital, multisectoral, integrated, sustainable, participatory, and human-focused project. It has also been viewed as a non-political project owing to its highly technical character, while at the same time being considered a political project for its potential to attract voters from the GAP region. In addition, the project was conceived as a suprapolitical, national security, and peace-oriented project for allegedly representing the strength of the Republic of Turkey and playing a strategic role in Turkey’s international relations. Nevertheless, it was simultaneously marked as a transformative, exploitative, and assimilative project meant to assimilate the Kurds and transfer the resources of eastern Turkey to western Turkey.Footnote 126

GAP’s objectives and contributions have been perceived in a variety of different ways as well. On the one hand, GAP was associated with highly technical objectives, such as the improvement of agricultural and industrial production, the irrigation of agricultural land, energy production, the raising of infrastructural standards, and the rational utilization of natural resources. On the other hand, it has also been associated with such socioeconomic objectives as eliminating inter- and intraregional disparities, generating national income, raising socioeconomic standards, and changing the destiny and face of Turkey. Moreover, it has also been connected with more political objectives, like preventing migration by containing the local population, eliminating feudalism and inequalities in land ownership, and contributing to the state’s efforts to fight against the PKK.

Among the drawbacks of GAP that have been discussed are criticisms of the project’s ecological and social consequences, such as damaging the environment, harming cultural and historical heritages, and causing displacement, inequality, and social degeneration. The project has also been criticized for its administrative drawbacks. It has been perceived as a delayed project that deviated from its integrated approach in order to prioritize energy projects, that was detached from the local population insofar as it failed to “trickle down” and provide the expected benefits, and that ultimately lacked a scientific focus due to limited partnership between academic and public institutions as well as to inadequate high-quality and practical research into the project.

As for why GAP remains an uncompleted project, among the factors cited for the delay in this regard have been administrative issues such as a strong centralized governance structure, cumbersome bureaucracy, and lack of coordination among state agencies; a lack of qualified personnel; poor and insufficient planning; and GAP-BKİ’s ambiguous tenure, insufficient capacity, and lack of practical authority. Also cited have been such economic issues as the lack of financial resources, public funds, and public and private investments, which have all been perceived as barriers preventing the project’s advancement. Political issues have also been brought up in regards to the project’s shortcomings and incompletion, including the supposed presence of “dark powers” preventing Turkey from fully implementing GAP, claims that the PKK has been sabotaging the project, and a general lack of political will, stability, and competence.

Finally, there has been a perception that, over time, GAP has lost its initial popularity owing to processes both global, such as changing development paradigms, and domestic, such as the privileged implementation of other ambitious, sensational, and thus vote-garnering projects; disappointment on the part of the local population due to goals unmet goals; and the indifference of society to the project in general.

Conclusion

Over time, how states, governmental and non-governmental institutions, and local communities interpret development has grown so diverse that development has come to mean anything and everything at the same time. Just as an empty signifier signifies a totality or universality,Footnote 127 development has come to signify, in different contexts, concepts and processes ranging from water resources development, infrastructure building, an increase in income level, modernity, and sustainability to social inclusion, self-sufficiency, entrepreneurship, security, good governance, and freedom. In other words, development is a vessel that can be filled with virtually any content. “Developmentspeak” has been simultaneously “descriptive and normative, concrete and yet aspirational, intuitive and clunkily pedestrian, capable of expressing the most deeply held convictions or of being simply ‘full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’ This very elasticity makes it almost the ideal post-modern medium, even as it embodies a modernizing agenda.”Footnote 128

In a somewhat similar fashion, GAP has since the 1970s evolved from a predominantly technical, largely state-led, and mainly infrastructural and economic development-oriented project into a primarily social, largely market-friendly, and chiefly sustainable and human development-oriented project. This shift was by no means an automatic outcome. Rather, it is linked to the very instability of the meaning of development and how development has been interpreted and practiced worldwide, with global development discourses often shaping how GAP’s key drivers have perceived development. Like a chain reaction, their perceptions have shaped how they steer the pace and direction of the project and prescribe roles to the project’s target groups, as each development paradigm adopts a different approach to addressing development problems. At the same time, however, changes in the project’s character and framework have not necessarily meant the abandonment of one development paradigm and its replacement by another. Instead, the degree of dominance of a given paradigm has increased or decreased in line with the rise and fall of development paradigms around the world. In short, GAP is to a great extent a product of concepts, norms, and standards borrowed from elsewhere and adjusted, or partly adjusted, to local contexts without fully taking into account “homegrown” sensitivities, concerns, and demands.

Furthermore, just as development signifies everything and nothing at the same time, many different concepts and practices have been conflated under the GAP heading, among them dam construction, energy production, irrigation, sustainability, women’s empowerment, and security. Even opposing terms—political and non-political, exploitative and sustainable, human-focused and national security—have been simultaneously chosen to define the project. In that sense, GAP also resembles an empty signifier-like container into which a wide variety of meanings can be placed according to context. Indeed, GAP has never been a monolithic project: it has rather been an umbrella project covering a wide range of sub-projects. However, the project’s current form is beyond hybridity since it is devoid of well-defined limits and a fixed content. It instead resembles a flexible and adaptive structure that is constantly being redefined, redesigned, and rebranded in accordance with contextual conditions, changing worldviews, and the institutional and/or personal interests of those responsible for the project. Arguably, a significant motivation for the involved actors to thus attach different meanings to development and to GAP has been to reap various benefits from their subjective characterizations. These benefits can take many forms: actors can gain legitimacy in international affairs (e.g., having the upper hand in water rights in the Middle East), attract more resources for their institutions (e.g., more budget allocation to the DSİ as compared to GAP-BKİ), or garner more political support (e.g., an increase in votes and/or popular support).

In summary, it can be asserted that there is no—or no longer—one precise and well-defined GAP. There are rather multiple, amorphous, and loosely defined GAPs all loaded with different meanings and attributions and permeating almost every aspect of life in the GAP region. This fluid structure has facilitated and continues to facilitate the justification of GAP’s imperfections and negative outcomes, the concealment of GAP-related and often political contestations and controversies, and the insulation of the project from a rigorous problematization and investigation to the extent possible.