Introduction

Turkey has become a prominent and permanent donor country, with its official development assistance (ODA) gradually reaching more than six billion US dollars by 2016, up from 500 million US dollars in 2005. This increase has definitely affected Turkey’s visibility in the developing world and international community in a positive way. What is the motivation behind this increase? Do historical and religious affiliations with recipients affect the pattern of Turkish aid? Do economic relations matter for determining Turkish aid? In this paper, we will undertake a quantitative analysis in order to discover the determinants of Turkish foreign aid for the period 2005–2016. In addition, the paper aims to reconsider the Justice and Development Party’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) Ottomanist, Islamist, nationalist, or trade-based economic motivations through an examination of the aid behavior of the AKP governments.

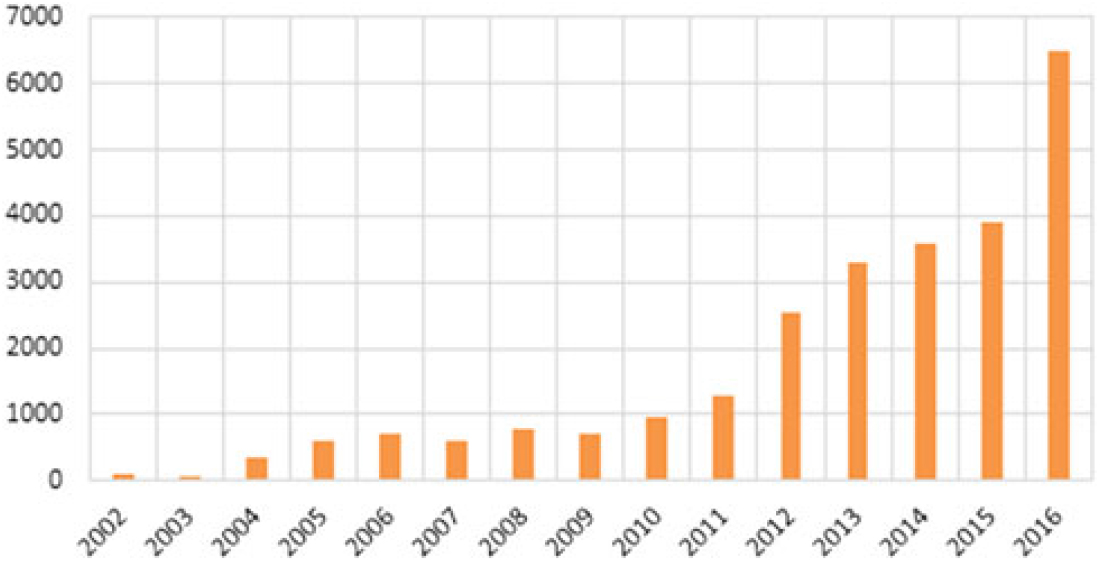

While the first instances of Turkish foreign aid date back to 1992, this aid was provided in only a very limited amount and across a relatively narrow geographic scope for over a decade, until Turkey gradually started adopting an internationalist foreign policy beginning in 2005.Footnote 1 The recovery of Turkey’s economy after the 2001 crisis and the subsequent positive boom in the markets, alongside constructive relations with the European Union (EU), helped the AKP to increase its aid budget, which in turn resulted in the adoption of foreign assistance as one of the state’s key foreign policy tools, or as a niche diplomacy. Figure 1 illustrates the exponential increase in the amount of money that Turkey has allocated to aid over the last decade.

Figure 1: Turkish official development assistance, 2002–2016 (figures in million US dollars)

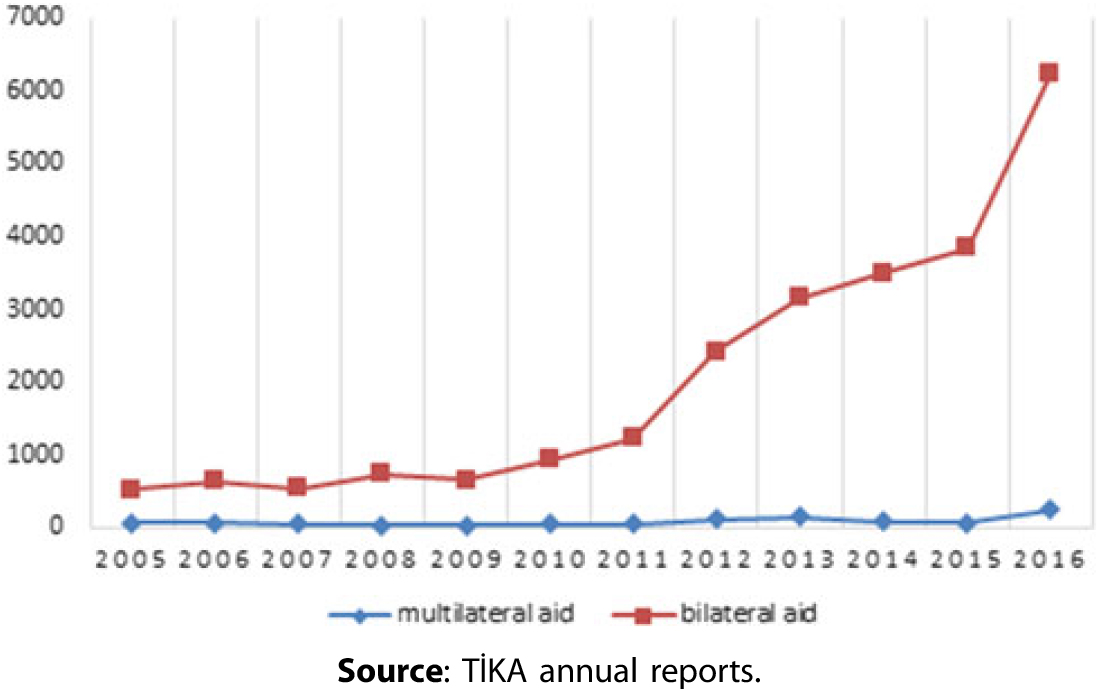

As seen in Figure 1, after 2005 the general tendency to increase the amount of aid continued without falling under the 500-million US dollar threshold. Turkey is a prominent rising donor whose aid disbursement in 2016, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) ODA statistics, surpassed that of other non-member donors of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), with the sole exception of Saudi Arabia. The difference between the amounts of bilateral and multilateral aid disbursed by Turkey is quite large in favor of bilateral aid, as seen in Figure 2. The ratio of multilateral aid in total flows was 11 percent in 2005. The ratio, however, has been decreasing over time: in 2015, for instance, while the total amount of aid flow from Turkey was about four billion US dollars, the amount of multilateral aid was only 73 million US dollars, corresponding to 1.86 percent of the total aid. This fact might stem from a desire to enhance Turkey’s visibility in the foreign aid realm, from reservations about the efficiency of multilateral mechanisms, or from the endeavor to develop deeper bilateral relations with recipients.Footnote 2

Figure 2: Turkish bilateral and multilateral official development assistance, 2002–2016 (figures in million US dollars)

Younas finds that donors might want to favor those recipients who have a greater tendency to import goods.Footnote 3 This may be another reason why Turkish aid is delivered largely through bilateral mechanisms. Another possibility is that Turkey’s motivations may be different from those of multilateral aid agencies, such as OECD-DAC, and thus Turkey might not wish to delegate control to an international institution. Finally, as suggested by the 2003 Rome Declaration on Harmonisation, there are certain concerns about the inefficiency of the processes used for preparing, delivering, and monitoring development assistance. For all these reasons, the aid disbursement structure of the OECD contains certain unproductive transaction costs.Footnote 4 Utilizing bilateral mechanisms as a way of avoiding institutional and bureaucratic costs might well be the reason why some countries prefer bilateral aid to multilateral aid. But whatever the case may be, understanding Turkey’s behavior as a donor country requires an empirical analysis that shows the importance of trade, religion, and other motivations.

The substantial increases in the amount of foreign aid provided by Turkey have primarily been discussed in terms of how Turkey is successfully pursuing nation-building activities in certain African countries;Footnote 5 to what geographic extent Turkey is proving able to convey its foreign policy tools;Footnote 6 how a sub-state agency, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (Türk İşbirliği ve Koordinasyon Ajansı, TİKA), has been successful in promoting Turkey’s image;Footnote 7 and, finally, how Turkey (intrinsically) is acting without abandoning humanitarian means while providing aid.Footnote 8 Foreign aid studies dealing with the experience of Turkey refer chiefly to the AKP’s tendency toward IslamismFootnote 9 or Ottomanism.Footnote 10 Nevertheless, there remains a considerable gap in the empirical analysis of the determinants of Turkish foreign aid. To the best of our knowledge, only Kavaklı has adopted an empirical method in order to analyze Turkey’s aid policies, with special focus on domestic politics and Turkey’s differences from established donors.Footnote 11

In this paper, we aim to reveal the determinants of Turkish foreign aid to the recipients of regular aidFootnote 12 for the period 2005–2016. This will be done by employing a system generalized method of moments (GMM) approach. Initially, we specify a base model used to test for the regularity of Turkish foreign aid, the solidity of state-firm relations, Turkish aid policy’s sensitivity to recipients’ income level, and the extent to which Turkish aid is in accordance with that of OECD-DAC. Subsequently, we hypothesize our claims based on the AKP’s increasingly common references to the Ottoman Empire, Islam, and prolonged ties with Turkic republics. In this connection, it is expected that historical affiliation, common religion, and status as a Turkic republic will have crucial positive effects on receiving Turkish foreign aid. Table 1 below presents a tabulation through which some insight can be gained into the importance of these variables in Turkish aid allocation over time.

Table 1. Turkish foreign aid tabulation for key indicators (figures in million US dollars in the constant term)

Source: OECD, “Aid (ODA) Disbursements [DAC2a].”

This paper comprises six sections. The following section will review the literature on recent Turkish foreign aid-based activities and provide a general idea of Turkey as a rising donor country. The third section will introduce our research hypotheses and present the theoretical framework for the discussion of foreign assistance, with a special focus on state-firm and state-society relations. The fourth section will test the factors that we attribute to explaining Turkish foreign aid behavior, as well as presenting the relevant results and discussion. The fifth section will enumerate robustness checks. Finally, the conclusion will debate the matter and provide insight into the policy implications of the results based on an econometric modelling, as well as conceptualizing Turkey’s stance and behavior as a major donor. That is, our model is expected to provide results that will describe Turkish foreign aid behavior via economic and cultural/political determinants.

The literature on Turkish foreign aid behavior

As a rising donor country, Turkey has been the subject of a good deal of analysis in the vast literature on foreign assistance. Recent and comprehensive articles on Turkish foreign assistance include Haşimi, Hausmann and Lundsgaarde, Aras and Akpınar, Hausmann, Özkan, Çevik, and Altunışık, all of which produce admirable inferential determinations concerning Turkey’s prospective foreign assistance abilities and constraints.Footnote 13 The literature on Turkish foreign aid policy, which is mainly based on TİKA’s activities and reports, has tended to see aid policy as a tool of foreign policy. With some exceptions, this paves the way for Turkey’s rise as a humanitarian actor on international platforms and in the underdeveloped world.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, in spite of the intense emphasis on humanitarianism, Islam is still considered by some scholars to be one of the most important determinants of Turkish foreign assistance.Footnote 15

The embeddedness of political motives within ostensibly humanitarian aims has become a characteristic of Turkish foreign aid, one that differentiates Turkey from both emerging and established donors, whose motives have been primarily energized through either development-based or politics-based ends, respectively.Footnote 16 In this regard, according to Altunışık, “cultural and historical affinity” has proven a major determinant of Turkish foreign aid, especially after the eruption of uprisings across the Arab world. Altunışık argues that, first, Turkey’s behavior as a donor has not been thoroughly affected by the needs of the recipients, and second, the probable repercussions of foreign aid on domestic Turkish politics are also significant in addition to humanitarian means.Footnote 17 The latter argument is compatible with what Çevik suggests in her study on state-based Turkish foreign aid, which conceives of public diplomacy as a tool for narrating an idealized Turkish image that can be utilized to consolidate the domestic constituency.Footnote 18

Another consolidator for the consecutive AKP governments has become to spread an ideology of the Ottoman dynasty and its heroic successes to all layers of Turkish society, as pointed out by Ongur: “As the previously established discontinuity between the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish state appears to erode, discussions of the concept of ‘Ottomanism’ attract increasing interest.”Footnote 19 According to Murinson, the roots of neo-Ottomanism in Turkish foreign policy date back to the era of Turgut Özal in the 1980s and early 1990s, during which time national and conservative morals were incorporated with free market enterprises. However, neo-Ottomanism’s scope, aim, and implications for both domestic and foreign policy were first thoroughly conceptualized at the beginning of the AKP era, using the insights and discourse of “strategic depth” (stratejik derinlik) as formulated by Ahmet Davutoğlu, who would later serve as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Prime Minister. In this approach, Turkey bridges established formations with new regional foreign policy paradigms and acts in such a way that both “Ottoman nostalgia” and “internationalist modernism” prove to have an impact on the state’s foreign aid behavior.Footnote 20 This variety of eclecticism might be regarded as part of a “new geopolitical imagination,”Footnote 21 one that is among the main elements of the AKP’s foreign policy practices in its manner of constituting Turkey-specific norms like “Muslim solidarity” and “Ottoman-related responsibility.”Footnote 22

The ascendance of Turkey as an emerging donor country has also attracted newly emerging quantitative studies on Turkish foreign aid. Kavaklı, for instance, conducts a Tobit model analysis covering the period 1992–2014, with panel data consisting of low- and middle-income countries and a special focus on humanitarian and economic aid.Footnote 23 His findings suggest that Turkic republics’ share in Turkish aid plummeted by 15 percent after the AKP came into power; that Muslim nations typically receive more humanitarian aid from Turkey than non-Muslim recipients; and that trade recipients who import Turkish goods at even an average level are expected to receive significantly more aid.Footnote 24 In terms of the matter of emerging and established donors, Kavaklı states that, while religious and ethnic similarities matter less for OECD-DAC countries than for Turkey, trade partnership is ultimately a more important factor than political affinity in determining aid, which is true for both OECD-DAC members and Turkey.Footnote 25

Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

National preferences, state priorities, and the policies enacted and followed by state-level organizations are all shaped around the way in which policy makers have personal proclivities toward a variety of identities and purposes to which these policy makers are incentivized by members of different domestic and transnational civil societies.Footnote 26 In parallel with Moravcsik, Wolfish and Smith regard non-state actors (e.g., NGOs, firms, business associations, and even certain religious sects) as power centers in international relations, since “the raison d’être for many NGOs [and other non-state actors] […] is to establish standards of behavior and influence state policy.”Footnote 27 That is to say, firms and business associations can sometimes be a determining factor that policy makers should bear in mind. In the Turkish case, it would be appropriate to emphasize the notion of controlled neo-populism, a term coined by Ziya Öniş, in order to better contextualize the matter of non-state issue in a roll-out neoliberalism process.Footnote 28 In the age of conservative globalism, the AKP’s formal and informal redistributive economic strategies have helped conservative Islamist entrepreneurs create their own business conglomerates and associations, such as the Independent Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association (Müstakil Sanayici ve İşadamları Derneği, MÜSİAD).Footnote 29 Moreover, perennial and to some extent exclusive secular business associations in local markets have pushed the AKP and the conservative business élite to start ventures abroad, in addition to gradually “monopolizing the center” in Turkey, both politically and economically.Footnote 30 This may well be tacit or even unintentional lobbying on the part of certain firms whose stakes depend on Turkey’s image in the international community and, specifically, aid-recipient countries.Footnote 31 To this end, we seek to test whether an indicator related to firm interest (i.e., the volume of export to the recipients) has been directing or incentivizing the state to increase the amount of assistance. Since we do not have any specific business association’s export performance for each recipient country, the study necessarily must include the amount of total export to the recipient countries. What is more, the very nature of aid leads one to presuppose that a donor country considers the most popular economic indicator, gross domestic product (GDP),Footnote 32 when deciding what amount of aid it should disburse to recipients.

In sum, our base model tests for the following hypotheses:

H1. Turkey is a regular donor: the amount of Turkish foreign aid in the current year will be affected by the amount of Turkish foreign aid in the previous year.

H2. Recipients who import more Turkish goods from Turkish firms will receive more Turkish aid.

H3. The lower the GDP of a recipient country, the more Turkish aid it receives.

Following these hypotheses, which concern the primary economic elements of aid behavior, as a second step we focus on the relationship between recipients and the established donor world (i.e., members of the OECD-DAC). To model the aforementioned relationship, we consider how much foreign aid OECD-DAC members disburse to the recipients. Additionally, besides its internal economic goals and political/cultural motivations, Turkey’s foreign aid decision—as is also the case for any donor nation—can also be driven by three motivations vis-à-vis established donors: (i) competition with OECD-DAC members; (ii) coordination with OECD-DAC members; and (iii) creation of its own domain of aid (i.e., independent donor behavior). If (i) and (ii) are the case, then the amount of Turkish foreign aid must be linked with that of OECD-DAC members.Footnote 33 In contrast, in the case of (iii), that link disappears. Therefore, the relevant hypothesis can be specified as follows:

H4. Turkey is an independent donor whose amount of foreign aid is not linked with that of established donors.

In the next step, we investigate the political/cultural motives that might have significant effects on determining the shape and magnitude of Turkish foreign aid inasmuch as foreign aid is a policy tool where domestic and foreign policies intertwine. Common cultural affiliations and historical affinities between the societies of recipient and donor may well have an impact on determining the amount of aid provided, since, as AltunışıkFootnote 34 and ÇevikFootnote 35 suggest, foreign aid can be used as a means of promoting the state’s image in the eyes of the domestic constituency. In many cases, the foreign aid literature includes colony indicators (British, French, or Spanish) as independent variables so as to capture any possible relation or effect existing between historical ties and foreign aid. In addition, a common history and shared religion are used as elements in a wide variety of studies that shed light on state behavior in this regard.Footnote 36

Insofar as this study aims to extend the foreign aid literature by using Turkey as a case study, the country’s Turkic heritage, Ottoman legacy, and Islamic affiliationFootnote 37 forms another main concern here. In Turkey, constituting ideological legitimacy via the use of neo-Ottoman symbols, emphasis on Islamic values, and nationalistic foreign policy is a means of élite survival strategy.Footnote 38 As pointed out by Bayulgen et al., the “symbolic representation of the new Ottomans resonated well with many segments of the population. It also served to cement the AKP’s ideological bond with its conservative supporters by giving them a rediscovered sense of historical pride.”Footnote 39 Using these cultural, ethnic, and religious a priori determinants, then, this study also tests for the following additional hypotheses:

H5. On average, Turkic republics will attract a greater amount of Turkish foreign aid than other countries.

H6. A recipient who was once a part of the Ottoman polity will have a higher aid flow from Turkey.

H7. The ratio of the Muslim population in a country has a massive effect on the amount of Turkish foreign aid.

In addition, to elaborate on this discussion, we have split former Ottoman lands into three sub-categories: the first includes former Ottoman territory in the east (in the Middle East and North Africa), the second former Ottoman territory in the west (in the Balkans and Eastern Europe), and the third former Ottoman territory located in other parts of the world.Footnote 40 In doing this, we are able to evaluate whether there is any regional pattern to the Ottomanist tendency in Turkish foreign aid policy. Subsequently, we specify another modified model so as to test whether the influences of Islamism on the amount of Turkish aid develops a different aspect in former Ottoman lands. Finally, we interact both the Ottoman dummy and the Muslim population’s rate variables with other explanatory variables in order to see whether these two variables have a meaningful effect on the interacted variables.Footnote 41

Data, model, and empirical results

Data

In order both to test our approach based on state-society relations and to inquire into the commonly accepted beliefs about Turkish foreign aid, we have constructed a dataset of aid transfer from Turkey to a hundred recipient countries that regularly host Turkish foreign aid. The dependent variable in the study is the amount of Turkish foreign aid. The data is provided by the OECD, with the current amount of aid transformed to real terms through the use of an export value index of the recipient countries provided by the World Bank.

As for the explanatory variables, the model initially employs one-period lagged value of the Turkish foreign aid in order to prove that Turkey is a consistent and regular donor country whose disbursement in the current year is a function of the disbursement of the previous year. This is also done to reveal any latent effects of unobserved variables within the lagged value. Turkish exports to the recipient countries serves as the second independent variable of our base model. This independent variable is especially important in that it directly tests the theory of Moravcsik, which posits firms as determinants of foreign policy practices as well as the concept of controlled neo-populism. Thirdly, as another independent variable the GDP levels of recipient countries are considered in order to see whether Turkey’s donor behavior is compatible with the OECD’s Millennium Development Goal, which foresees that donors give more aid to countries with less income. We take a one-year lag of these variables because we argue that the variables’ effects only come into being in the following year.Footnote 42 After estimating the base model, we incorporate OECD-DAC members’ aid into the analysis in order to control for possible relationships between the recipient countries in question and the established donors. This is also done because it is important to determine whether Turkey keeps up with the established donors or acts in its own way within the donor world.

The political/cultural determinants of our model consist of three variables, two of which are dummy variables indicating whether a state is, first, the Turkic republics and, second, has an Ottoman past or not. The reason why these dummy variables are included in the model originates from both the raison d’être behind the establishment of the TİKA and the neo-Ottomanism debate that emerged within the scope of the AKP’s foreign policy vision. The ratio of the Muslim population among Turkish aid recipients, which is a prominent variable in the sense that the literature on Turkish foreign aid has attributed undeniable importance to religion, is the third political variable in the model. Table 2 below summarizes our variables, alongside some descriptive statistics and sources.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

The panel dataset is strongly balanced according to the Ahrens-Pincus index, with a value of 0.849.

Detailed information about political/cultural variables is presented in Table 8 in the appendix.

Model

The model is specified in a dynamic nature as follows:

$${\bf{lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}} = {\bf{\alpha lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{t}} = 1}^{\bf{T}} {{\bf{\theta }}_{\bf{t}}}{{\bf{D}}_{\bf{t}}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{e}} = 1}^{\bf{E}} {{\bf{\beta }}_{\bf{e}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}^{\bf{e}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{p}} = 1}^{\bf{P}} {{\bf{\gamma }}_{\bf{p}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\bf{p}} + {{\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}}{{\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}} = {{\bf{v}}_{\bf{i}}} + {{\bf{\epsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}}$$

$${\bf{lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}} = {\bf{\alpha lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{t}} = 1}^{\bf{T}} {{\bf{\theta }}_{\bf{t}}}{{\bf{D}}_{\bf{t}}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{e}} = 1}^{\bf{E}} {{\bf{\beta }}_{\bf{e}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}^{\bf{e}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{p}} = 1}^{\bf{P}} {{\bf{\gamma }}_{\bf{p}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\bf{p}} + {{\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}}{{\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}} = {{\bf{v}}_{\bf{i}}} + {{\bf{\epsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}}$$

where (lfai, t ) is the foreign aid provided by Turkey to recipient country (i) at time (t), with i = 1, …, N, t = 1, …, T; (lfa i,t -1) is the one-period lagged foreign aid and (1-α) the speed of adjustment to equilibrium; the (Dt )’s are the yearly dummy variables; the (X′)’s are the explanatory variables (namely, Xe denotes economic variables and Xp political and cultural variables); (εi,t ) is the disturbance, with ( vi ) the panel fixed effect (which may be correlated with the covariates) and (εi,t ) the idiosyncratic error; and finally, (θ, β, γ ) are the parameters to be estimated. In the model above, Turkish foreign aid, exports, and income level, as well as the OECD-DAC aid variable, are expressed in natural logarithms. As is well known, for a stable dynamic model, the coefficient of the lagged value of the independent variable (i.e., lfa i,t-1) is expected to lie between +1 and −1. The parameters to be estimated—namely, ( θ, β, γ )—represent the short-run effects of the relevant variables on determining the amount of Turkish foreign aid. Furthermore, it is possible to calculate the long-run effects of relevant variables based on the speed of adjustment and the short-run effects. For instance, the long-run effects of the economic variables may be calculated as follows:

The model is estimated by the system GMM two-step estimatorFootnote 43 pioneered by Arellano and BoverFootnote 44 and Blundell and Bond.Footnote 45 The procedure is implemented by the Stata software using Roodman’s xtabond2 routine,Footnote 46 which is widely accepted in the foreign aid literature.Footnote 47 The main advantage of the system GMM two-step estimator is to consider a possible correlation between the lagged dependent variable and the panel fixed effects, as well as to consider the “small T, large N” restriction. Windmeijer’s procedureFootnote 48 is also implemented so that standard errors become robust after getting the small sample size of the dataset under control. For the possible weaknesses of the estimation results—such as unobserved heterogeneity, endogeneity, autocorrelation, and weak instruments—we present the Arellano-Bond AR test for autocorrelation, the Hansen-J tests for overidentifying restrictions and thus the instrument exogeneity, and finally the conventional F test.

Estimation results

To perform a basic robustness check, we initially estimate the model using only economic variables. Then, we sequentially incorporate the OECD-DAC and political/cultural variables into the model. The estimation results are presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Estimation results, Ia

Parentheses stand for corrected standard errors. *, **, and *** imply significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively. Numbers in square brackets are the probability values of the relevant test statistics. The models above also include time dummies presented in a separate table in the appendix.

a The unit of the dependent variable is 1,000 US dollars. Because the natural logarithm of zero is not defined, we add one to this variable before taking its logarithm.

The estimated coefficients related to the lagged values of the Turkish foreign aid variable meet the aforementioned stability condition, implying that the models are stable and that Turkey is a persistent donor.Footnote 49 The estimation results pass diagnostic checks. The models are estimated to be statistically significant; there is no autocorrelation of the second order, and the instruments are valid according to the F-test, Arellano-Bond test, and Hansen-J test, respectively.

Based upon the estimation results presented in Model 3 of Table 3, it is determined that a one percent increase in Turkish exports to a given recipient country leads to a 0.251 percent increase in Turkish aid to that country. Besides this, it should also be noted that Turkey gives more aid to countries with less income: a one percent increase in a given recipient’s GDP results in a 0.224 percent decrease in the amount of Turkish aid. After controlling for the economic variables, it is estimated that Turkish aid advances together with OECD-DAC aid: a one percent increase in OECD-DAC aid results in a 0.289 percent increase in Turkish aid as well. Overall, the estimation results reveal that Turkey is a consistent and regular donor that considers Turkish firms’ presence in recipient countries while also paying attention to the economic performance of the recipients as well as to OECD-DAC’s aid allocation.

Model 3 also produces information related to nationalism, Ottomanism, and Islamism. All other things being equal, Turkic republics receive approximately 305 percent more aid than non-Turkic recipients.Footnote 50 Similarly, recipients get 95 percent more aid from Turkey if they were once ruled by the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 51 In addition to these political dummy variables, the ratio of the Muslim population to the total population in recipient countries is also estimated to be statistically significant. A one-point increase in the Muslim population of recipient countries leads to a one percent increase in Turkish aid.Footnote 52 Strictly speaking, then, a recipient country whose population is wholly Muslim would attract 100 percent more Turkish aid than a country where no Muslim lives, all other things being equal. To sum up, if a nation has historical ties to the Ottoman Empire and a wholly Muslim population ratio, it will receive 195 percent more aid than a nation with no Ottoman history and no Muslim population, provided that these two cultural indicators are independent of each other.

To further understand the Ottoman impact on Turkish aid behavior, the former Ottoman states have been categorized as eastern, western, and other, as mentioned above.Footnote 53 As seen in Model 4 of Table 4 below, the Ottoman impact on Turkish foreign aid behavior does not matter in the eastern states. However, western and other recipient countries with an Ottoman past attract more Turkish foreign aid by 271.35 percent and 100 percent, respectively, as compared to other countries, all else being equal.Footnote 54

Table 4. Estimation results, II

Parentheses stand for corrected standard errors. *, **, and *** imply significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively. Numbers in square brackets are the probability values of the relevant test statistics. The models above also include time dummies, presented in a separate table in the appendix.

In order to discuss whether the influence of Islamism varies in determining the amount of Turkish aid in former Ottoman lands, Model 3 is modified. The Muslim rate variable is multiplied by the Ottoman dummy variable so as to generate two new variables; namely, Muslim rate in former Ottoman lands and in lands that were never Ottoman. Model 5 indicates that Islam has an important impact in attracting Turkish foreign aid if and only if the recipient was not once a part of Ottoman territory.

The fact that Turkish foreign aid is thus motivated by Ottomanism and Islamism led to an investigation of whether these political/cultural variables have some influence on policy makers’ outlook on economic indicators. The effects of the economic indicators may vary across the recipients. For instance, if a recipient is former Ottoman territory or has a high ratio of Muslim population, the income level of the recipients or the export performance of Turkish firms to the recipients might not matter when decision makers are allocating aid. The empirical analyses above assume that the effects of the economic variables do not differ across the nations covered by the dataset. However, the effects of these variables may vary throughout the cultural and political characteristics of the recipients. To handle this presumption, we have designed more detailed empirical models.

In the first additional model, all variables are multiplied by the Ottoman dummy variable. Model 6 in Table 4 below presents the empirical results related to Ottomanist effects on the other explanatory variables. Here, there are two differences between Ottoman and non-Ottoman recipients. The latter receive less Turkish aid as their economies grow, while the former receive slightly more Turkish aid even if they have a growing economy. Countries that were never Ottoman receive 0.216 percent less Turkish aid when their economies grow by one percent, while former Ottoman recipients receive 0.077% more Turkish aid in the same situation.Footnote 55 Thus, a key economic indicator is ruled out when a historical identity comes to the fore in the Turkish aid case. Moreover, an interesting result emerges when we interact the Muslim rate with the Ottoman dummy variable. A one-point increase in the Muslim population of a recipient causes a 1.2 percent increase in Turkish aid, but if the recipient also has an Ottoman past, the impact of religion almost disappears: to wit, a one-point increase in the Muslim population in a recipient with an Ottoman past decreases Turkish aid by 0.4 percent.Footnote 56

An empirical analysis focusing on the impact of religion was also conducted. In this setup, the Muslim rate variable was multiplied by other explanatory variables in order to test whether Islam has an impact on them. The relevant estimation results are presented in Table 4 as Model 7. This model suggests that Islam has some impact on the Turkic and Ottoman dummy variables. A former Ottoman recipient with no Muslim population receives 363.66 percentFootnote 57 more Turkish aid, but a one-point increase in the Muslim population in this recipient decreases this ratio to 361.76 percent.Footnote 58 This is consistent with the previous model, which implies that Ottomanism and Islamism are mutually exclusive. Similarly, a one-point increase in the Muslim population decreases the amount of aid given to Turkic republics by 3.33 percent.Footnote 59

Generally speaking, the empirical analyses strongly indicate that Turkish foreign aid is distributed because of certain economic indicators, such as the export performances of Turkish firms and the income level of recipients, in addition to the aid allocated by OECD-DAC members, which serves as a measurement of the extent to which recipients are intertwined with the established world. This implication is also completely valid for recipient countries that were never ruled by the Ottomans, have no Muslim population, and cannot be classified as Turkic. Nevertheless, the picture becomes more complicated when political/cultural determinants come to the fore. Recipient countries that have an Ottoman past but are not located in the Middle East or North Africa attract more Turkish aid (see Model 4). Similarly, being classified as Turkic proves to be another incentive for the recipients to obtain more Turkish foreign aid (see Models 3–7). Having a larger Muslim population also has an effect on whether or not a given country receives more Turkish foreign aid, even for recipient countries that do not have an Ottoman past and are not classified as Turkic republics (see Models 6 and 7). Finally, it should be noted that recipients with an Ottoman past continue to receive more Turkish foreign aid even if their economies grow, a phenomenon that does not hold for recipients without an Ottoman past (see Model 6).

The current Turkish foreign aid literature predominantly uses TİKA’s reports along with in-depth interviews from the field to make certain inferential determinations. This study, on the other hand, provides an empirical platform to initiate a new discussion on Turkish aid, especially insofar as it both supports and contradicts previous findings. First, studies on Turkish aid that concentrate on the effects of Islam as a universal phenomenon are supposed to exhibit the same effect all across the globe. In this study, however, although Islam’s overall effect is shown to be largely in parallel with the results indicated in the literature, at the same time Islam’s effect on Turkish aid is shown to differ if the aid recipient is a former Ottoman state or a Turkic republic: in countries with an Ottoman past and/or that are Turkic, Islam’s substantial effect dramatically decreases. Second, the study finds that Turkish aid is strictly (and reversely) affected by the income levels of recipients overall, but again, if the recipient has an Ottoman past, increasing level of income does not cause a decrease in the amount of Turkish aid. This supports Altunışık’s assertion that Turkish aid is not thoroughly determined by the needs of recipients, at least for the Ottoman case. Third, Özkan’sFootnote 60 contention that Turkish foreign policy is not based on neo-Ottomanism at all seems questionable, since the models outlined here indicate the authenticity of a counter-argument, at least in the case of foreign aid behavior. Moreover, although Özkan considers Turgut Özal’s foreign policy paradigm, which puts relations with Turkic republics at the very core of the state’s priorities, to be a now obsolete approach, the models outlined in this paper suggest that the opening toward Central Asia following the dissolution of the Soviet Union still has valid and statistically meaningful remnants.

Robustness Check

As discussed earlier in the paper, we have added explanatory variables block by block in order to check how sensitive the estimated coefficients are to the inclusion of new variables. In Model 1 and Model 7, the estimated coefficients do not have any changing signs. Moreover, the magnitudes of the coefficients do not vary dramatically. In this section, we will check for the robustness of the results in four additional dimensions.

The first of these is motivated by the fact that the conventional ordinary least squares (OLS) and the least square with dummy variables (LSDV) estimators are inconsistent for dynamic panel models due to the Nickell bias. As discussed in Bond, OLS estimators of dynamic panel models are biased upward, while LSDV estimators are biased downward; Bond suggests that a consistent estimator should lie between the OLS and LSDV estimators.Footnote 61 Running OLS and LSDV estimators for the models here, we see that the coefficients of the lagged foreign aid variable for system-GMM results lie between those of the OLS and LSDV. For instance, in Model 3, the coefficient of lagged foreign aid is 0.367, whereas the related coefficients are 0.644 for OLS and 0.306 for LSDV. Because the Nickell bias diminishes as the sample size grows and the time span utilized here covers 12 years, which is relatively high for short panels, it seems plausible that the GMM estimates lie near the LSDV estimated values.

Second, due to the possibility that bilateral foreign aid comes with a stipulation that influences trade as well, export can be considered not only endogenous, but also predetermined and exogenous.

Third, a basic rule of thumb for GMM estimations is that the number of sections should be bigger than the number of instruments. Even though this study’s estimation procedure meets this criterion in all models, the models are re-estimated by reducing the instrument counts so as to avoid instrument proliferation. The results remain robust because the estimated coefficients do not dramatically vary in either case.Footnote 62

Finally, it was necessary to analyze whether there was any structural change in parameter values throughout the AKP era. For this, separate time dummies covering the period 2011–2016 were created, and the model was respecified as follows:

$${\bf{lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}} = {{\bf{\alpha }}^{\rm{*}}}{\bf{lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{t}} = 1}^{\bf{T}} {\bf{\theta }}_{\bf{t}}^{\rm{*}}{{\bf{D}}_{\bf{t}}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{e}} = 1}^{\bf{E}} {\bf{\beta }}_{\bf{e}}^{\rm{*}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}^{\bf{e}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{p}} = 1}^{\bf{P}} {\bf{\gamma }}_{\bf{p}}^{\rm{*}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\bf{p}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{e}} = 1}^{\bf{E}} {\bf{\beta }}_{\bf{e}}^{{\rm{**}}}{{\bf{D}}_{\rm{*}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}^{\bf{e}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{p}} = 1}^{\bf{P}} {\bf{\gamma }}_{\bf{p}}^{{\rm{**}}}{{\bf{D}}_{\rm{*}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\bf{p}} + {\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\rm{*}}{\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\rm{*}} = {\bf{v}}_{\bf{i}}^{\rm{*}} + {\bf{\epsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\rm{*}}$$

$${\bf{lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}} = {{\bf{\alpha }}^{\rm{*}}}{\bf{lf}}{{\bf{a}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{t}} = 1}^{\bf{T}} {\bf{\theta }}_{\bf{t}}^{\rm{*}}{{\bf{D}}_{\bf{t}}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{e}} = 1}^{\bf{E}} {\bf{\beta }}_{\bf{e}}^{\rm{*}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}^{\bf{e}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{p}} = 1}^{\bf{P}} {\bf{\gamma }}_{\bf{p}}^{\rm{*}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\bf{p}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{e}} = 1}^{\bf{E}} {\bf{\beta }}_{\bf{e}}^{{\rm{**}}}{{\bf{D}}_{\rm{*}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}} - 1}^{\bf{e}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{{\bf{p}} = 1}^{\bf{P}} {\bf{\gamma }}_{\bf{p}}^{{\rm{**}}}{{\bf{D}}_{\rm{*}}}{\bf{X}}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\bf{p}} + {\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\rm{*}}{\bf{\varepsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\rm{*}} = {\bf{v}}_{\bf{i}}^{\rm{*}} + {\bf{\epsilon }}_{{\bf{i}},{\bf{t}}}^{\rm{*}}$$

where (D*) is a dummy variable taking values of 1 for periods later than 2010 and 0 for other periods. If the coefficients (

![]() $\beta _e^{**}$

) and (

$\beta _e^{**}$

) and (

![]() $\gamma _p^{**}$

) are estimated to be statistically significant, it means that Turkish foreign aid behavior during the period 2005–2010 is different from that of the period 2011–2016. As seen in Table 5 in the appendix, coefficients (

$\gamma _p^{**}$

) are estimated to be statistically significant, it means that Turkish foreign aid behavior during the period 2005–2010 is different from that of the period 2011–2016. As seen in Table 5 in the appendix, coefficients (

![]() $\beta _e^{**}$

) and (

$\beta _e^{**}$

) and (

![]() $\gamma _p^{**}$

) are in fact not estimated as statistically significant, revealing that Turkish aid behavior was stable throughout the period studied. However, there was one exception, which implied that the importance of nationalism was in decline for the period 2011–2016 as compared to the period 2005–2010. This is also consistent with what Kavaklı finds in his article.

$\gamma _p^{**}$

) are in fact not estimated as statistically significant, revealing that Turkish aid behavior was stable throughout the period studied. However, there was one exception, which implied that the importance of nationalism was in decline for the period 2011–2016 as compared to the period 2005–2010. This is also consistent with what Kavaklı finds in his article.

Conclusion

This study has aimed to reveal the determinants of Turkish foreign aid over the last decade. To this end, we specified an econometric model where the amount of Turkish foreign aid is regressed via the system-GMM estimator on certain economic and political/cultural indicators, as well as its one-period lagged value, thereby conveying the unobservable effects of other variables that cannot be included in the model; this represents the regularity of Turkish foreign aid. The paper’s dataset includes a hundred countries that received Turkish foreign aid during the period 2005–2016.

As suggested by the liberal intergovernmentalism formulated by Moravcsik and the non-state power centers detailed by Wolfish and Smith, when making a decision (such as determining how much aid to disburse and to whom), a state considers the impacts of the decision on society as well as how the economic actors would be affected by that decision, because the extent to which a government can retain its power depends on the level of satisfaction of these non-state actors (i.e., the domestic constituency and, simply put, the firms). The endeavor to create a new conservative wealthy class might be seen as a kind of cooperative interaction between the state and certain firms. What is more, in Turkey foreign aid is also used as a domestic policy tool to enhance the AKP’s humanitarian, historical, and religious visions in the eyes of the domestic constituency. This is why the models in this study consist of variables that indicate cultural and religious affiliations as well as economic activities. Foreign aid allocation policy in the AKP era is assumed to be shaped around historical, ethnic, and religious ties with the recipient countries. To this end, neo-Ottomanism and pan-Islamism are two crucial Turkish foreign policy keystones that call for elaboration through econometric models.

The empirical results of this paper reveal that Turkey is a regular donor whose amount of foreign aid, without exception, is positively influenced by the export-based embeddedness of Turkish firms in recipient countries. Recipient countries in an aid relationship with OECD-DAC members also receive more foreign aid from Turkey. Recipients with an Ottoman past attract more Turkish foreign aid than countries without an Ottoman past. Islam’s overall effect is statistically significant, but this significance disappears in former Ottoman lands, suggesting that the Islamic motivation no longer exists for the decision makers in the formerly Ottoman geography. In addition, low level of income and high level of Muslim population in recipients are other incentives prompting Turkey to disburse more foreign aid to recipients without an Ottoman past. That is to say, even though income level has an inverse relationship with Turkish aid, income does not have the same relation in former Ottoman lands. Being a Turkic republic is another distinguishing feature of Turkish aid, but its effect was in decline in the period 2011–2016 as compared to the period 2005–2010. In terms of the Ottomanism and Islamism debates on Turkish foreign policy in the AKP era, the study finds that, although both the Ottoman and the Muslim rate variable are statistically significant, Ottomanism is in an exclusionary position for the Muslim rate, since Islam’s effect on the disbursement of Turkish aid has been ruled out in connection with formerly Ottoman lands. Finally, the power of Ottomanism and nationalism to attract Turkish foreign aid compensates for the negative influences that Islamism exerts on the aid amount allocated to both former Ottoman and Turkic recipients.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/npt.2019.1

Appendix

Table 5. Structural stability of Turkish foreign aid behavior

Parentheses stand for corrected standard errors. *, **, and *** imply significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively. Numbers in square brackets are the probability values of the relevant test statistics. The models above also include time dummies, presented in a separate table in the appendix.