We will not cut from the people’s medicines.

—Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, September 2009

We will make very serious savings in health.

—Minister of Finance Mehmet Şimşek, September 2009

Introduction

The Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) has governed Turkey since November 2002. This period is commonly understood as one of “neoliberal restructuring.”Footnote 1 To be sure, the 2000s and 2010s have witnessed many neoliberal policy reforms, including the mass privatization of state-owned enterprises, the reduction of marginal income tax rates, and labor market flexibilization.Footnote 2 Yet the AKP’s economic and social policy regime has not been one of neoliberal orthodoxy.Footnote 3 The party’s commitment to neoliberal policy principles such as marketization has been regularly compromised by its conservative ideology and its ardent concern with maintaining popular and elite support. The presence of these countervailing forces has manifested itself, for instance, in the expansion and reorganization of social assistance and in the strengthening of the role of the state in the housing market.Footnote 4 Scholars have used terms such as “neoliberal populism,” “social neoliberalism,” “heterodox transition to neoliberalism,” and “passive revolution” to conceptualize the unorthodox nature of the AKP’s neoliberalism.Footnote 5

A particularly widespread notion in this context is that the AKP has been both neoliberal and populist. Often building on earlier work on “neoliberal populism” in Latin America,Footnote 6 scholars of Turkish politics have examined the ways in which the AKP government has combined neoliberal and populist characteristics.Footnote 7 This literature is complicated by the fact that the term “populism” has at least two broad meanings.Footnote 8 In the substantive/economic meaning, populism refers to policies of redistribution and nationalization (often presumed to have negative fiscal consequences),Footnote 9 while in the formal/political meaning it refers to a “a mass movement led by an outsider or maverick seeking to gain or maintain power by using anti-establishment appeals and plebiscitarian linkages.”Footnote 10 Both of these meanings are valid and will probably continue to coexist in the literature. But it is important to recognize that they have different implications for how one thinks of “neoliberal populism.” Scholars who adopt the formal definition of populism tend to think of neoliberal populism as neoliberal policies introduced with the help of populist politics. In contrast, those who adopt the substantive definition think of it as some combination of populist and neoliberal policies.Footnote 11 In this article, I use the substantive definition of populism and therefore adopt this latter policy-based understanding of neoliberal populism.

Despite the relative abundance of studies demonstrating that the AKP government has followed both neoliberal and populist policy principles, we still know relatively little about the political processes behind the AKP’s “neoliberal populism.” In this article, I contribute to a more fine-grained understanding of the political dynamics that have underpinned the economic and social policy making of the AKP government. I empirically study Turkish pharmaceutical policy and, in particular, explain the AKP government’s major reform of pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy that occurred in September 2009. This case is relevant for several reasons. Given that pharmaceutical expenditure makes up a large share of total public health expenditure, pharmaceutical policy is a significant component of health policy, which, in turn, has played an important political function for the AKP government. Yet many existing studies on the politics of Turkish health policy in the 2000s leave aside the dimension of pharmaceutical policy.Footnote 12 Moreover, Turkey’s pharmaceutical policy reform of September 2009 is interesting because it was the result of the conflicting interests of the various groups that have supported the rule of the AKP government; namely, the three segments of the business community (foreign, domestic-secular, and domestic-conservative), Turkey’s lower-class electorate, and international institutions. Pharmaceutical policy therefore represents a privileged field for analyzing the political economy of the AKP era.

In September 2009, Turkey’s pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy experienced an abrupt and major change. After years of rising public expenditure under a pricing system that allowed pharmaceutical producers generous profit margins, the AKP government introduced a “global budget” that capped public pharmaceutical expenditure for the 2010–2012 period.Footnote 13 Crucially, the lion’s share of this expenditure cut was implemented by stricter price controls that reduced the profit margins of pharmaceutical producers and distributors (the populist policy solution) rather than by privatizing the cost of medicines through, for example, raising out-of-pocket payments (the neoliberal policy solution).Footnote 14 As a result, the AKP’s post-2009 pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy were characterized by significant redistribution: over three years, an estimated amount of 20 billion TL was redistributed from pharmaceutical producers and distributors to pharmaceutical consumers, who for the most part are reimbursed by the Turkish state. The reform of September 2009 represented a profound break with the previous policy regime in that Turkey’s pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy transformed, practically overnight, from being relatively lenient and business-friendly to being very strict and anti-business. This reform is a major empirical puzzle for observers familiar with the AKP government’s usual preference for lenient and business-friendly regulation.

In a previous study, İpek Eren Vural argues that the “increasing stringency of price and expenditure controls” is a reflection of the interests of a capitalist alliance, including “internationalised fractions of the Turkish capital and the transnational financial capital,” whose main concern during the global economic crisis in 2009 was to preserve Turkey’s overall economic model; namely, its “short term capital led growth model.”Footnote 15 Accordingly, she argues that Turkey’s post-2009 pharmaceutical policy regime was a result of the broader macroeconomic policy context, in particular the government’s commitment to fiscal discipline. This account goes some way to explaining Turkey’s new pharmaceutical expenditure policy; that is, the introduction of a strict global budget. But it does not explain Turkey’s new pharmaceutical price policy; that is, the implementation of the global budget primarily by means of price cuts rather than by means of increasing private pharmaceutical financing. After all, there was fierce opposition by both domestic and foreign pharmaceutical producers against Turkey’s new system of strict pharmaceutical price controls.

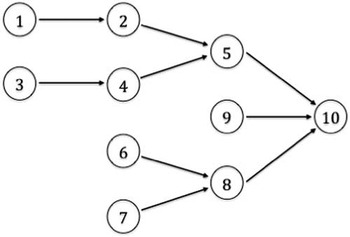

In contrast to Eren Vural’s Marxist account, I provide an explanation of Turkey’s post-2009 pharmaceutical policy change that focuses on the political actors and processes that produced this outcome. In a nutshell, my argument is that the AKP introduced a global pharmaceutical budget because it wanted to make substantial “savings in health” (sağlıkta tasarruf) during negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the aftermath of the 2008–2009 global economic crisis, and not because it had any inherent concern with either high pharmaceutical expenditure or prices. Initially, the technocrats in charge of economic policy, in particular Deputy Prime Minister for the Economy Ali Babacan and Minister of Finance Mehmet Şimşek, planned to implement the global budget with the help of a policy instrument from the orthodox neoliberal toolbox; namely, the privatization of cost through higher out-of-pocket payments.Footnote 16 Aware of the potential political cost of restricting public health care financing and thus “cutting from the people’s medicines,” the AKP’s political leadership, in particular Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, intervened by demanding that “savings in health” must not reduce popular access to public health care services. With the neoliberal solution (“retreat of the state”) thus off the table, Babacan and Şimşek turned to the remaining policy solution that could achieve sizeable savings in public pharmaceutical expenditure; namely, much stricter government regulation of prices and private sector profits. I argue that this populist, anti-business reform of pharmaceutical policy should be understood not only with reference to post-crisis fiscal discipline, but also with reference to, on the one hand, the absence of powerful business interests in high medicine prices, and, on the other hand, to the absence of a developmentalist commitment to a high-price industrial policy strategy for the pharmaceutical sector. Figure 1 graphically summarizes the political process-based argument of this article.

Figure 1 Explanation of Turkey’s shift to strict pharmaceutical price controls.

1) AKP government seeks IMF's approval of Turkey's three-year economic program in order to maintain macroeconomic stability; 2) Introduction of a global budget for public pharmaceutical expenditure; 3) High salience and popularity of health policy among the AKP's electorate; 4) AKP's political leadership vetoes plans to increase private pharmaceutical financing; 5) Announcement of strict pharmaceutical price controls; 6) Foreign pharmaceutical producers have little influence on the AKP government; 7) “Anatolian capital” has no strong interests regarding pharmaceutical price controls; 8) Absence of powerful business interests in high medicine prices; 9) Absence of an industrial policy strategy for the pharmaceutical sector; 10) Introduction of strict pharmaceutical price controls.

This article is based on research conducted between 2012 and 2014. Descriptive statistics on public pharmaceutical expenditure, prices, and market size are employed to demonstrate that Turkey shifted to stricter pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy. Data on market size and public discounts were obtained from the pharmaceutical industry and the drug regulatory agency. For market prices, I draw on high-quality data collected by the global healthcare consultancy IMS Health. For my explanation of the political process, I draw on news reports, expert interviews, and descriptive statistics. 36 semi-structured, anonymous interviews were conducted between May 2012 and April 2013. Interviewees included pharmaceutical regulators, industry executives, and other pharmaceutical sector experts. Wherever possible, I cite publicly available records, including news pieces, industry reports, and descriptive statistics. In addition, further descriptive statistics are used throughout the article to provide evidence for central claims. I also draw on the secondary literature that deals with the same historical juncture.Footnote 17

The remainder of this article consists of four sections. The next section provides an overview of the relevant developments prior to 2009, in particular the AKP’s health reform as well as the concomitant restructuring of the pharmaceutical market. The third section describes the political process that led to the introduction of a tight global pharmaceutical budget and strict price controls in late 2009. The fourth section proposes an explanation of this puzzling policy reform. The final section concludes by drawing out some of the more general lessons for scholars of Turkish politics.

The transformation of health and pharmaceutical policy, 2002–2009

The introduction of strict pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy in late 2009 came largely unexpected. But with the benefit of hindsight, one can identify the longer-term developments that set the stage for this earthquake-like policy change.Footnote 18 In the following, I will discuss health reform, which turned into one of the central political projects of the AKP during its first term in government, as well as the relevant pharmaceutical policy changes of the 2002–2009 period.

In the early 2000s, the need for health reform arose against the background of an inegalitarian corporatist health care system, where service provision was public but also highly fragmented.Footnote 19 This had generated substantial inequalities of access, especially between the insiders and the outsiders of public health care, but also between the different social security programs.Footnote 20 In 2002, only 67 percent of the population was covered by the public health care system,Footnote 21 and an even lower share of 58 percent had access to pharmaceutical reimbursement, as the Green Card program did not cover pharmaceuticals prior to 2005. The AKP government’s Health Transformation Program (Sağlıkta Dönüşüm Programı) was launched in 2003 and created a single-payer health care system offering a basic benefits package to the entire population by unifying existing social security funds.Footnote 22 The reform led to a significant expansion of access to public health services. In 2010, the new system reached a near-universal formal coverage rate of 96 percent for both health services and pharmaceutical reimbursement.Footnote 23 As a likely result of this expansion in access, public health outcomes significantly improved during the 2000s.Footnote 24 The reform also led to more public health care spending. The share of public health care expenditure in the GDP rose from 3.78 percent in 2002 to 4.43 percent in 2008.Footnote 25

The process of health reform also led to important changes in the regulation of the pharmaceutical market. In February 2004, Turkey’s government fundamentally reformed the framework of pharmaceutical price regulation by introducing a system of “external reference pricing.”Footnote 26 Under this system, the legally permitted maximum price of a medicine in the Turkish market is determined in relation to the price of the same product in a group of reference countries. This replaced the previous system of “cost-plus pricing,” dating back to 1984, under which producers were theoretically allowed to set prices freely as long as they remained within certain profit margins (15 percent for total revenues and 20 percent for any single product).Footnote 27 One major reason for the 2004 reform was the difficulty of determining the cost structure of pharmaceutical production and hence the proper implementation of the 1984 pricing system. At the time of the reform, Minister of Health Recep Akdağ referred to high pharmaceutical prices and the “burden” they place on public pharmaceutical expenditure as the primary reason for the reform.Footnote 28 In fact, this problem had already been identified at the beginning of the Health Transformation Program:

Proportionally speaking, expenditures on pharmaceuticals are very high in Turkey. […] We know that the increases in drug prices do not rest on a scientific basis. As part of the Health Transformation Program, stakeholders will be brought together in dialogue and agreement, in order to solve, according to scientific principles, the longstanding problems with pharmaceuticals, one of the most important elements of health care.Footnote 29

Despite this rhetorical commitment, however, pharmaceutical price controls did not become substantially stricter prior to September 2009.

In December 2004, the state and the three industry associations signed the Public Pharmaceutical Purchase Protocol (Kamu İlaç Alım Protokolü), which liberalized and expanded the pharmaceutical market. First, the 35 million members of the largest social security fund, the Sosyal Sigortalar Kurumu (SSK), were allowed to purchase their medicines on the free market. Previously, they had only been eligible for reimbursement when purchasing from pharmacies affiliated with the SSK. While this restriction was unpopular among many of its members, it allowed the fund to purchase through tenders, and thus at overall lower prices.Footnote 30 Second, the protocol also entailed the beginning of pharmaceutical reimbursement for approximately 13.5 million Green Card holders. Clearly, both changes implied substantial profit opportunities for producers. In return, producers agreed to grant the state special public discounts of 4 and 11 percent. Important in this context is that around 85 percent of pharmaceutical consumption in Turkey is financed by the state—one of the largest so-called public shares in the world—thus constituting a quasi-monopsonistic market structure.Footnote 31 Concerning the protocol, Minister of Finance Kemal Unakıtan commented that “this was a win-win situation.”Footnote 32

A final important characteristic of the Turkish pharmaceutical market is the relatively strong protection of intellectual property rights. When Turkey adopted the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) in the 1990s, it used few of the flexibilities provided. This policy change, which was primarily to the benefit of multinational pharmaceutical companies, came in the context of Turkey’s regional economic integration with the European Union.Footnote 33 In the 2000s, the AKP government did not fundamentally challenge this strong protection of intellectual property in Turkey’s pharmaceutical sector, but it did implement a rather weak form of data exclusivity legislation, which was more in the interests of domestic generic producers than those of foreign producers of original medicines.Footnote 34

The business-friendly nature of pharmaceutical regulation in the first seven years of the AKP government allowed for exceptional market growth. From 2002 to 2009, nominal public pharmaceutical expenditure grew by 17.4 percent annually. The market for prescription medicines grew by 16.5 percent annually in the same period—no surprise considering Turkey’s high public share. This strong value growth was the result of both volume growth (8.5 percent annually) and price growth (7.4 percent annually).Footnote 35 While profit data is difficult to collect, the stable value and price growth in the 2002–2009 period suggests that overall producer profitability was not substantially compromised by any of the AKP government’s regulatory changes prior to September 2009.

This boom period in the Turkish pharmaceutical market was accompanied by a wave of foreign acquisitions of local producers.Footnote 36 Even after the onset of the global economic crisis, producers expected this boom to continue. In February 2009, one foreign executive remarked that the pharmaceutical sector had been “least affected by the crisis” compared to other sectors of the Turkish economy and that he saw a “bright future” for it.Footnote 37 This sentiment was widely shared: in April 2009, an article in the magazine Pharmaceutical Executive selected Turkey as one of the world’s seven “pharmerging markets” and predicted annual growth of 11–14 percent through 2013. Turkey, with its exceptionally high public share, was especially attractive to multinational pharmaceutical producers during the global economic crisis because “growth in publicly funded markets is likely to ameliorate some of the stress.”Footnote 38 These expectations were to be disappointed very soon.

The shift to stricter pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy, 2009–2012

While the 2008–2009 global economic crisis had not directly affected Turkey’s pharmaceutical market, it eventually triggered the Turkish government to do so itself by means of stricter regulation. With GDP contracting by 4.7 percent in 2009 and unemployment climbing from 9.9 percent in 2008 to 14 percent in 2009, Turkey’s economy was severely hit by the crisis.Footnote 39 To address the crisis, the government began negotiating a stand-by agreement with the IMF in December 2008. While the agreement was never concluded, negotiations continued throughout 2009. Öniş and Güven have argued that Turkey’s government was not actually interested in the credit line, but rather in the positive psychological effect that the appearance of successful negotiations with the IMF would have on investors. Turkey therefore employed “the process as a quasi-anchor to manage market expectations.”Footnote 40 As will become clear in this section, these negotiations with the IMF constituted a critical juncture during which Turkish policy makers introduced a global budget and stricter price controls for pharmaceuticals.

In practice, the managing of market expectations meant that policymakers were drafting an economic program for 2010–2012 and were seeking the IMF’s (public) approval of it. Unsurprisingly, the IMF demanded commitment to structural reforms, including measures to contain public health care expenditure.Footnote 41 When it became clear by mid-2009 that substantial cuts to the health budget had to be made, the question for policy makers became where these savings could be realized. At this point, attention turned to public pharmaceutical expenditure in particular. Coincidentally, 2009 also happened to be the first year since the launch of the health reform in which public pharmaceutical expenditure grew at a higher rate (23.9 percent) than public non-pharmaceutical health expenditure (9.0 percent). This development had become foreseeable to policy makers by mid-2009. In fact, it was reported to them that pharmaceutical expenditure in Turkey had been growing faster than in any other country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).Footnote 42 It was at this point that policy makers began to perceive pharmaceutical expenditure as a target both promising and deserving for the realization of significant cuts to the health budget.

The government’s commitment to stable and predictable public finances was to be signaled through three-year “global budgets”; that is, predetermined upper spending limits. It was in late July 2009 when it was first reported that Deputy Prime Minister Babacan was planning to introduce separate global budgets for the state’s hospital and pharmaceutical expenditures.Footnote 43 From the first conception of the policy idea, things proceeded quickly and apparently without much consultation of the pharmaceutical sector. In late August 2009, Minister of Finance Şimşek announced that global budgets would be introduced for public expenditure on private, state, and university hospitals (including inpatient pharmaceutical consumption) as well as for public pharmaceutical expenditure (covering outpatient pharmaceutical consumption).Footnote 44 The global health budgets were eventually announced on September 15, 2009 as part of the 2010–2012 Medium Term Program (the “IMF budget” discussed above). Minister of Labor and Social Security Ömer Dinçer announced that public health care expenditure would be reduced by a total of 3 billion TL in 2010, half of which would be realized in the pharmaceutical budget.Footnote 45

However, there was no automatic link between the decision to cut public pharmaceutical expenditure and the introduction of stricter pharmaceutical price controls. Instead, Turkish policy makers had two alternative policy solutions to the problem of public pharmaceutical expenditure cuts. The first of these, the neoliberal policy solution, would have reduced public pharmaceutical expenditure primarily by increasing the private share in pharmaceutical financing. This could have been achieved by such policy instruments as higher co-payments, higher out-of-pocket payments, and the delisting of medicines from the reimbursement positive list. However, such a “retreat of the state” by and large did not occur in the years after the 2009 reform.Footnote 46 Instead, policymakers went for the second option, the populist policy solution, where the aim of lower public pharmaceutical expenditure is primarily achieved by financing the same volume of medicines at lower prices. In the case of Turkey, this was primarily achieved by stricter price controls and, to a lesser extent, by increased generic substitution of prescribed original drugs.

That Turkish policy makers had eventually embraced the populist policy solution became clear when the details of the 2010–2012 Medium Term Program were announced on September 16, 2009. The 1.5 billion TL of envisioned pharmaceutical savings were to be realized through reducing supply sector profitability. Minister of Labor and Social Security Dinçer announced at the budget presentation that “nothing will change in the way citizens receive their health service. But we will negotiate with the service, drug, and device sectors from which we purchase.”Footnote 47 He added that the primary policy tools would be to reduce manufacturer prices and to implement public discounts.

This announcement was followed by two-and-a-half months of government negotiations with the three large pharmaceutical industry associations, who eventually accepted severe price cuts in order to implement the global pharmaceutical budget by signing an agreement in December 2009.Footnote 48 The agreement specified the three-year budget: after an initial cut of 9 percent (the 1.5 billion TL promised in September) to 14.6 billion TL in 2010, the budget would be allowed to grow by 7 percent in 2011 and 2012 (to 15.5 and 16.7 billion TL, respectively). However, because the budget was to be enforced over the three-year period, overshooting in one year would lead to additional cuts in the subsequent year. This is why the actual development of expenditure in 2010–2012 followed a different path. Overall, the impact of the global budget was massive. Had public pharmaceutical expenditure continued to grow at 17.4 percent (the compound annual growth in 2002–2009) after 2009, then the total expenditure in 2010–2012 would have been 67 billion TL. Compared with this fairly realistic baseline scenario, the global budget of 46.8 billion TL implied a savings of 20.2 billion TL, or 30 percent, over three years.

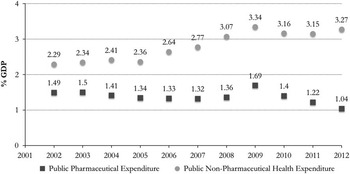

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the effect of the global budget on the development of public pharmaceutical and health expenditure. In nominal terms, public pharmaceutical expenditure grew steadily from 2002 to 2009, while public non-pharmaceutical health expenditure grew equally steady, but faster. With the introduction of the global budget, pharmaceutical expenditure stagnated, while non-pharmaceutical health expenditure continued to grow (Figure 2). Industry representatives sarcastically remarked that they would be “the ATM of the government.”Footnote 49 In relative terms, pharmaceutical expenditure was slowly declining from 2002 to 2008, while non-pharmaceutical health expenditure was growing (with the crisis year of 2009 representing a bit of an outlier). After the introduction of the global budget, pharmaceutical expenditure rapidly decreased, while non-pharmaceutical health expenditure more or less stagnated (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Turkey’s Nominal Public Health Care Expenditure, 2002–2012.

Figure 3 Turkey’s Relative Public Health Care Expenditure, 2002–2012.

One might wonder why all three producer associations accepted the global budget. Thanks to Wikileaks, we know that the American embassy cabled home that “under the terms of the deal, the [Turkish government] moved only marginally from its initial negotiating stance, and reserved the right to modify the terms of the deal if economic conditions change. […] Industry analyst appraisals of the deal have ranged from ‘ruinous’ to ‘disastrous,’ but all agreed that even the minor improvements were better than no deal at all.”Footnote 50

Over the three-year duration of the 2010–2012 global budget, Turkish policy makers zealously implemented the price controls necessary to meet the budget. Three policy instruments were particularly effective in this regard.Footnote 51 First, the framework of external reference pricing was employed to bring down maximum market prices by reducing the reference factor, especially, of generic and off-patent original pharmaceuticals.Footnote 52 Second, mandatory public discounts were increased and applied disproportionately to on-patent original pharmaceuticals.Footnote 53 Third, the exchange rate used for external reference pricing was kept fixed at 1.9595 TL/Euro from April 2009, and therefore significantly undervalued for most of the 2010–2012 period.

Overall, the stricter price controls proved very effective.Footnote 54 After the pharmaceutical average price had steadily increased from 2002 to 2009 (7.4 percent annual price growth), this trend was reversed from 2009 to 2012 (–4.6 percent annual price growth).Footnote 55 For many of the best-selling medicines, price deterioration was even more significant. The average prices of the ten best-selling pharmaceuticals in 2009 fell annually by 13.5 percent from 2009 to 2012.Footnote 56 However, success at reducing prices was uneven across different categories of pharmaceuticals. While prices of off-patent original and generic pharmaceuticals decreased substantially, it appears that the government was less able to reduce the prices of crucial on-patent original pharmaceuticals.Footnote 57 By and large, however, pharmaceutical prices decreased substantially between 2009 and 2012 due to the stricter price regulations.

Explaining the policy shift: electoral interests, business interests, and industrial policy

In the previous section, I outlined how Turkey shifted from a lenient and business-friendly to a strict and anti-business pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy in late 2009. This naturally raises the question of why this policy shift occurred. More specifically, the question is why the Turkish government adopted the populist rather than the neoliberal policy solution to the problem of public pharmaceutical expenditure cuts. In this section, I propose that this outcome can be explained with reference to (i) the pronounced electoral interests of the AKP’s political leadership in not substantially reducing access to public health services, (ii) the absence of powerful business interests in high medicine prices, and (iii) the absence of a developmentalist commitment to an industrial policy strategy for the pharmaceutical sector.Footnote 58

Electoral interests in access to health care services

One of the key drivers of Turkey’s shift to stricter pharmaceutical price controls was the role of health policy in the electoral politics of the AKP. To make this point, we need to step back and take another look at the political process that unfolded in September 2009. While Turkey’s government did eventually adopt a populist policy in order to reduce pharmaceutical spending, initial proposals pointed in a very different direction. When Babacan and Şimşek first discussed possible policy instruments in public, their proposals focused on increasing generic substitution, promoting “rational drug use,” and increasing private out-of-pocket payments.Footnote 59 Therefore, at the time it appeared as if Turkey was heading toward the neoliberal policy solution so as to achieve “savings in health.” At this point, a political intervention by Prime Minister Erdoğan occurred that challenged this looming policy choice. At a public event, Erdoğan commented on the proposed budget cuts:

In the history of the Republic of Turkey, never was as much money spent on social security as in the current era. […] This is priceless. “Sir, the budget has a deficit.” You cannot foreclose this, you cannot stop this by saying the budget has a deficit, whatever it is. Because this project is priceless, we will do whatever it takes. From time to time I disagree on this topic with my ministers. There are some steps we need to take, because we are in a race and we need to succeed.Footnote 60

Erdoğan thus publicly rejected the idea of making cuts to public health care expenditure. Later he was also quoted as having specifically said that “we will not cut from the people’s medicines.”Footnote 61 A few days after Erdoğan’s intervention, Şimşek responded in such a way as to realign with the prime minister.

Our esteemed prime minister, of course, supports our work, under the condition that there is no deterioration in access to health services and the quality of health services we provide. I think the message there has been misunderstood. Our esteemed prime minister supports us within that frame. You will see that we will make very serious savings in health.Footnote 62

This represented a conflict between the AKP’s technocratic economic policy makers on the one hand and its election-minded political leadership on the other hand. The technocrats Babacan and Şimşek were primarily concerned with making savings in the health budget in order to fulfill IMF conditionality and thus safeguard macroeconomic stability; whether by ideological conviction or default, they originally planned to achieve this with relatively standard neoliberal instruments. Importantly, the election-focused party leader Erdoğan did not propose or demand the introduction of stricter pharmaceutical price controls, but he did effectively constrain the technocrats’ ambitions to “make very serious savings in health” in such a way as to leave price cuts as the only option left on the table.

This leads us to the question of why Erdoğan made this assertive intervention, which was to lead to strict, anti-business regulation. In a nutshell, I propose that he was worried that reducing public financing of pharmaceutical consumption or other health services would be unpopular, and could thus result in a substantial loss of electoral support due to the high issue-salience of access to public health care services, especially among the AKP’s relatively poorer voters.

Indeed, health policy has been among the most popular policy areas of the AKP government, especially during its first (2002–2007) and second (2007–2011) terms in office. Even though most health sector trade unions and professional organizations opposed the reform, popular satisfaction with public health care services had increased from just 40 percent in 2003 to 65 percent in 2009.Footnote 63 That this development was exceptional becomes clear when comparing popular satisfaction with public health care services to the popular satisfaction with other public services, such as judicial services, for instance, where popular satisfaction had decreased from 46 percent in 2003 to 39 percent in 2009.Footnote 64

Public satisfaction with the government’s health policy appears to have paid off for the AKP at the polls. Surveys have suggested that a majority of voters considers health policy as the most successful policy area of the AKP government, and the prominent pollster Adil Gür argued that health policy had been the most important factor in the AKP’s second election victory in 2007.Footnote 65 There have been estimates that 10 percentage points of the AKP’s 47 percent in 2007 could be attributed to popular support for the government’s health policy. Whether this actually was the case or not does not matter much. What is important for my argument is that the political leadership of the AKP, which does have a reputation for meticulous popular opinion polling,Footnote 66 perceived its health policy performance as important for its political success, and so embraced health policy as one of its key political projects. This seemed to be especially the case in the period after the 2007 election; that is, the time period during which strict drug price controls were introduced.

The fact that health policy became a vote-winner for the AKP during the 2000s, and came to be perceived as such, is related to the salience of this policy area among the party’s potential electorate. The rural and urban lower classes, “the traditional base of the Islamist movement” in Turkey, have been the key constituency of the AKP in terms of electoral support.Footnote 67 According to surveys, the voters of the AKP are poorer, more rural, and more religious than the voters of the main opposition, the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, CHP).Footnote 68 Many of the AKP’s supporters are employed in the informal economy and had traditionally been excluded from Turkey’s corporatist welfare system. In other words, many of the AKP’s supporters were previously welfare state outsiders, but had newly become insiders, especially due to the health reform of the 2000s.

In conjunction, this evidence supports the thesis that Erdoğan’s intervention in the policy debate over “savings in health” was motivated by his understanding of the electoral importance of health policy for his government and his concern that cutting health care expenditure by cost privatization could come at high political cost. Because Babacan and Şimşek were committed to cutting the health budget, stricter pharmaceutical price controls remained as the only available solution.

Absence of powerful business interests in high prices

The Turkish government’s political will for low medicine prices that emerged in September 2009 was a direct result of the electoral interests of the AKP leadership in maintaining access to public health care services. In other words, the high salience and popularity of health policy clearly implied a political logic of low medicine prices. However, these electoral interests alone cannot explain why Turkey’s government was able to maintain its strong political will for low medicine prices throughout the ensuing negotiations with the industry. After all, governments around the world frequently place the issue of stricter drug price controls on the political agenda, but they often dilute their initial reform proposals.Footnote 69 Hence, I propose that Turkey’s government was able to maintain its strong political will for low medicine prices because of the absence of two factors that would have implied a competing political logic of high medicine prices. This requires me to make two counterfactual arguments about the sources of a political logic of high prices.Footnote 70

The first of these counterfactual arguments is that the Turkish government’s political will for low medicine prices would have been significantly diluted if powerful business interests in high medicine prices had existed. However, this was not the case, as the segment of the business community that had a strong interest in high medicine prices—i.e., foreign pharmaceutical companies—had lost influence on Turkey’s government during the AKP era, while the segment of the business community that arguably had some influence—i.e., “Anatolian capital”—was not very active in pharmaceutical production and thus had little interest in the level of medicine prices.

Foreign multinational pharmaceutical producers have found it increasingly difficult to have their concerns heard by the Turkish government in the AKP era. In order to convince the government to relax price regulations and budget constraints, the Association of Research-based Pharmaceutical Companies (Araştırmacı İlaç Firmaları Derneği, AİFD), an association of multinational producers, presented a comprehensive report about Turkey’s pharma-industrial prospects in September 2012. The primary purpose of the report was to provide Turkey’s government with a reason to relax pharmaceutical price and reimbursement regulations and allow public pharmaceutical expenditure to expand again. But the executives of these foreign firms had problems to be heard by the government. As of early 2013, the AİFD had been unable to get an appointment with Ali Babacan and the Economic Coordination Council (Ekonomi Koordinasyon Kurulu, EKK) to present the report, a sign of the government’s indifference toward the special interests of this group of pharmaceutical producers.Footnote 71

Foreign pharmaceutical producers had not always had such problems in getting their concerns heard by the Turkish government. In 2002, the coalition government that preceded the AKP government was also struggling with the aftermath of an economic crisis. As part of its stand-by agreement with the IMF, it planned to contain public pharmaceutical expenditure through increased generic substitution. In May 2002, one month after the reform was first proposed, the American corporation Pfizer sent to Ankara an eleven-member delegation under the leadership of its global vice president Sidi Said. It was the delegation’s pronounced aim to convince the government to abandon the reform. Within a short time, the delegation managed to arrange appointments with all relevant ministers, including Kemal Derviş, who was then the influential minister of state for economic affairs and in charge of the stabilization program.Footnote 72 Speaking with the press, Sidi Said claimed that the policy would harm the introduction of new medicines into the Turkish market,Footnote 73 and he announced that, due to the new policy, Pfizer had already cancelled investments worth 80 million USD.Footnote 74 Other multinationals, such as Merck Sharp & Dome, were making similar threats.Footnote 75 After his term in office, the responsible minister, Yaşar Okuyan, gave two interviews regarding the issue, stating that he had been pressured by the American ambassador in Turkey, Deputy Prime Minister Mesut Yılmaz, and Kemal Derviş to abandon the reform. Pfizer had apparently also managed to mobilize the IMF for their concerns. According to Okuyan, the IMF negotiators told the Turkish policy makers during a meeting that the generic drug policy was “creating problems.”Footnote 76 It seems reasonable to conclude that the protest of the foreign pharmaceutical companies and the special access they had to Turkey’s government played a key role in the abandoning of these stricter regulations. During the AKP era, foreign pharmaceutical producers seem to have lost this special access to Turkish policy makers.

While the interests of foreign pharmaceutical producers were not powerful enough to countervail the AKP’s own electoral interests, “Anatolian capital,” which may have had more influence on the AKP government’s policy making, had no strong interest in the content of Turkey’s pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy.Footnote 77 Besides the party’s lower-class electorate, “Anatolian capital” has been the second key constituency of the AKP. When the later prime minister Erdoğan and his political allies decided to split from the radical Islamist movement in 2001 and establish the AKP, crucial early support came from this group of conservative business people, who are today primarily organized into three voluntary business associations: the Independent Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association (Müstakil Sanayici ve İşadamları Derneği, MÜSİAD), the Anatolian Lions Businessmen’s Association (Anadolu Aslanları İşadamları Derneği, ASKON), and the Turkish Businessmen’s and Industrialists’ Confederation (Türkiye İşadamları ve Sanayiciler Konfederasyonu, TUSKON).Footnote 78 Many of these conservative businesspeople have actively employed their capital to further the political power of the AKP, for instance by investing in the media sector and in this way increasing their impact on public opinion. Some of these conservative entrepreneurs even became political representatives for the AKP on the national or local level. In return, many of these “politically connected” businesspeople have come into increased wealth thanks to privileged treatment by the government, for example in the field of public procurement.Footnote 79 Given the close relationship that “Anatolian capital” has with the AKP, the interests of this segment of the business community are likely to weigh heavier in the policy making of the AKP government.

Even so, no significant pharmaceutical producer was owned by “Anatolian capital” in the 2009–2012 period. While many businesspeople close to the AKP have been active in the health sector, especially the private hospital market, their presence in the pharmaceutical industry has been limited. At the time when the AKP government decided to introduce a global budget and implement it through strict price controls, Turkey’s pharmaceutical market was dominated by foreign ownership. The remaining large domestic producers, Abdi İbrahim and Bilim İlaç, cannot be considered as “Anatolian capital.”

It should be noted that some local generic producers close to the AKP have been emerging in recent years. Most prominently, the Sancak family (Saya Group) founded the company Pharmactive in 2010 and has since built a large production plant in Çerkezköy in the province of Tekirdağ. This new company aims to quickly become one of Turkey’s largest generic manufacturers, as well as to become a significant exporter of pharmaceuticals.Footnote 80 Such large new investments were met with little understanding from domestic industry representatives, given that other domestic producers are allegedly even running deficits in a low-profitability environment.Footnote 81 This may imply that “Anatolian” investors trust in the future profitability of their investments despite the current regulatory environment. In the future, “Anatolian capital” may therefore well develop a stronger interest in high medicine prices once these new pharmaceutical producers grow larger, which may in turn influence the government’s pharmaceutical policy. However, in the 2009–2012 period, “Anatolian” pharmaceutical producers remained small and appear to have been active primarily in the hospital market (some 5 percent of the total market), in which purchases are made through tenders. Since neither the global pharmaceutical budget nor the post-2009 price controls apply to the hospital market, the presence of some “Anatolian capital” in this market segment is unlikely to have diluted the government’s political will to reduce pharmaceutical prices.

Absence of a high-price industrial policy strategy

The second counterfactual argument about an alternative political logic of high medicine prices is that the Turkish government’s political will for low medicine prices would have been significantly diluted if Turkish politicians and bureaucrats had been ideologically committed to a high-price industrial policy strategy for the pharmaceutical sector. Political commitment to the industrial development of the domestic pharmaceutical sector generally implies more lenient regulation of pharmaceutical prices. If national regulators of a capitalist economy wish to increase investments in domestic production, they need to ensure that these investments are profitable. If price controls become stricter, then investments in domestic production become less likely. In the words of Gary Gereffi, “high prices of drugs thus may be viewed as an acceptable trade-off for the consolidation of a local industrial bourgeoisie.”Footnote 82 From the perspective of industrial policy, the pharmaceutical sector has often been considered as a “priority area […] on account of the positive spillovers throughout the industrial sector that pharmaceutical industries can generate.”Footnote 83 This sector is particularly important from a developmentalist perspective, as it is considered to generate high-value added production and high-quality employment. Somewhat ironically, economic policy makers with a more developmentalist perspective may therefore have opposed the kind of strict price controls that Turkey introduced after September 2009.

However, the AKP government and its economic bureaucracy, especially in the 2009–2012 period, did not have any real ideological commitment to an industrial policy strategy for the pharmaceutical sector, at least not to the point where they would have significantly relaxed price controls for this purpose. While the AKP government had an official objective to develop domestic pharmaceutical production, as illustrated by Erdoğan’s call for the development of a “national pharmaceutical” (millî ilaç) in January 2013,Footnote 84 there have been no signs that this nominal commitment has led the government to adopt a political logic of high prices. For instance, although the Ministry of Science, Industry and Technology has founded a unit responsible for the industrial development of the pharmaceutical sector, it has also left it woefully understaffed.Footnote 85 The government has introduced an investment incentive scheme to increase domestic production, but it has refrained from reconsidering its position on price controls. Historical experience may have taught regulators that loose price regulations alone do not attract investments in local production. For many years, profitability in the sector was much higher, but local production was declining in relative terms.

Pharmaceutical producers are well aware of the effect that an industrial policy strategy could have on price controls and, in turn, on profit margins. As a result, they frequently use the promise of domestic industrial development as a “carrot” to motivate national governments to relax price controls. Since strict price controls were introduced in late 2009, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Turkey (İlaç Endüstrisi İşverenler Sendikası, İEİS), an association of generic producers, as well as the AİFD, which is an association of mostly multinational original producers, have presented comprehensive reports on Turkey’s prospects for pharmaceutical industrial development.Footnote 86 For instance, the AİFD “believes” that by 2023 Turkey can become a regional hub for pharmaceutical production and R&D, and thereby “a net exporter of pharmaceutical drugs with an export surplus of more than USD 1 billion (as compared to a 2011 foreign trade deficit of USD 4.1 billion).” Few industry insiders believe this to be a realistic possibility. Instead, the primary purpose of the report was to provide the Turkish government with a rationale to relax pharmaceutical price controls and increase public pharmaceutical expenditure. However, as mentioned above, as of early 2013 the AİFD had been unable to even get an appointment with Ali Babacan and the EKK to present its report.Footnote 87 This absence of a developmentalist commitment to pharmaceutical-sector industrial policy, along with the absence of powerful business interests in high prices, allowed the AKP government’s political will to introduce strict pharmaceutical price controls to remain undiluted.

Conclusion

In this article, I have examined the case of Turkey’s post-2009 pharmaceutical expenditure and price policy. Despite the AKP government’s reputation for business-friendly, neoliberal regulation, during the time under consideration it challenged the generally powerful interests of the pharmaceutical industry. In the 2010–2012 period, Turkey saved some 20 billion TL in public pharmaceutical expenditure through the introduction of a global budget. The lion’s share of this was achieved by reducing the profit margins of pharmaceutical producers (and distributors) rather than by privatizing the cost of medicines. It is important to note, however, that neither the AKP’s technocratic policy makers nor its political leaders were inherently interested in the stricter regulation of pharmaceutical prices and profits. Instead, Turkey’s strict drug price controls were the unintended consequence of, on the one hand, Babacan and Şimşek’s technocratic concern with macroeconomic stability, and, on the other hand, Erdoğan’s political concern with electoral support. Moreover, the reform became possible because the primary losers of this policy, foreign pharmaceutical producers, had insufficient political leverage over the AKP, as well as because Turkey’s economic policy makers had no developmentalist commitment to industrial policy that could have translated into a political logic of higher medicine prices.

The evidence of this particular case of pharmaceutical policy reform supports several more general conclusions regarding the political dynamics that have underpinned the economic and social policy making of the AKP government. First, it appears that the “social face” of the AKP is of a mostly instrumental nature. The strict regulation of prices and profits in the pharmaceutical sector that was implemented after September 2009 needs to be viewed as a redistributive, pro-poor reform. Yet the reform was merely the unintended consequence of other political dynamics. This case therefore demonstrates that the AKP is, in principle, capable of implementing pro-poor policies, even if that would require strict business regulation, and also that the AKP has the ideological flexibility to forego neoliberal policy recipes—if only the interests of its major constituencies are favorably aligned. However, such a favorable alignment of interests appears to be increasingly difficult in an environment where few policy areas have the salience and electoral potential of health policy and where “Anatolian capital” is expanding into more and more sectors of the Turkish economy, including the pharmaceutical sector.

Second, the economic and social policy making of the AKP government appears to be driven largely by the interests of its two major constituencies: the party’s lower-class electorate and the emerging group of conservative businesspeople known as “Anatolian capital.” It is important to stress that this does not mean that the more established group of secular businesspeople (commonly associated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association [Türk Sanayicileri ve İşadamları Derneği, TÜSIAD]) or foreign capital hold no power over the AKP government. But the case of pharmaceutical policy reform shows that the AKP government is willing and able to move against the interests of these two groups if it is politically expedient to do so. It is furthermore likely that the influence of the AKP’s lower-class electorate is stronger in more salient policy areas such as health and pharmaceutical policy. Hence, this article does not suggest that all, or even most, of the AKP’s economic and social policy making has been driven by the interests of lower-class voters.

Lastly, the AKP’s economic and social policy makers are not a monolithic group with the same concerns and priorities. The policy outcome examined in this article was shaped by the interaction of the different concerns and priorities of neoliberal-minded technocrats on the one hand (Babacan and Şimşek), and election-focused party leaders on the other hand (Erdoğan). Policy outcomes in other areas may thus be shaped predominantly by either one of these two camps, or by their interaction. Taking this internal heterogeneity of the AKP’s policy makers more explicitly into account should provide a more fine-grained and eventually better understanding of the political dynamics that have driven Turkish economic and social policy making under the rule of the AKP.