1. Introduction

In this article, we present a set of criteria for the identification of the focus of negation in Spanish and outline the general framework used for its annotation in the NewsCom corpus. The identification of the focus of negation is an important issue in natural language processing (NLP) because the focus not only identifies the most important negated element in a negation structure but also has effects on the semantic interpretation of the overall sentence. Identifying the focus of negation is an important challenge in all NLP applications (such as information extraction, information retrieval, and sentiment analysis) and NLP tasks (such as the detection of temporal and factual events, irony and hate speech). However, due to the difficulty of the task, the detection of the focus of negation has received little attention in NLP compared to the research carried out on the identification of negation markers and scope. The detection of the focus cannot be tackled relying on formal—morphological and syntactic—criteria because it is a phenomenon that goes beyond the limits of syntax and often involves communicative intentions, world knowledge, and paralinguistic information, such as gestures, prosody, and stress. The difficulty of the task increases when we deal with written texts, for which this kind of information is not available. The complexity of the phenomenon explains the scarcity of annotated corpora and detailed identification criteria able to cover a wide range of negated structures. The current situation is that, firstly, theoretical proposals from linguistics are not always easy to implement in terms of concrete criteria for corpus annotation. Additionally, linguistic theory does not always cover all the variety of negative structures that appear in real data. The situation becomes more critical when dealing with informal written texts extracted from the web or with sublanguages such as that of medical reports, in which linguistic conventions are not always followed.

Our aim is to contribute two new linguistic resources to the study of negation both for linguistics and NLP research: the NewsCom corpus and initial criteria for focus identification. To our knowledge, this is the only corpus annotated with negation markers, scope, and focus in Spanish.

We followed the Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002) proposal that defines the focus of negation as the part of the scope that is most prominently or explicitly negated.Footnote a This is the most-widely accepted definition of the focus of negation in NLP (Blanco and Moldovan (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014), Morante and Blanco (Reference Morante and Blanco2012) Guzzi et al. (Reference Guzzi, Taulé and Martí2017) and Francis and Taboada (Reference Francis and Taboada2017)), and we have taken into account the works of all these authors to establish the criteria for focus identification, given the lack of such studies for Spanish.

This article is structured as follows: in Section 2, we present corpora annotated with the focus of negation and describe the NewsCom corpus. In Section 3, we present the general criteria for the identification of the focus of negation. Section 4 is devoted to the description of the specific criteria for focus identification in Spanish. In Section 5, we present how the corpus was annotated, the inter-annotator agreement tests performed, and quantitative information about the annotation of the NewsCom corpus. Finally, our conclusions and future work are set out in Section 6.

2. Corpora annotated with the focus of negation

To the best of our knowledge, there are few corpora annotated with the focus of negation in the literature and most are for English. All the corpora mentioned in this section annotate the focus and the negation markers, and all of them take into account the discourse context for focus detection. Some of them also annotate the scope of negation.

Blanco and Moldovan (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2011) presented the first corpus annotated with the focus of negation in English. They annotated 3993 verbal negations that were marked with the Negation Marker role in the PropBank corpus (Palmer, Gildea, and Kinsbury 2005). They consider that “the focus corresponds to a single role or the verb. In cases where more than one role could be selected the most likely focus is chosen; context and text understanding helps solving ambiguities. We define the most likely focus as the one that yields the most meaningful implicit information” (Blanco and Moldovan Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014: 520).

These authors assume that the focus of negation is the “element of the scope that is intended to be interpreted as false to make the overall negative true,” and therefore, a negated statement can carry a positive implicit meaning. The final aim of these authors is to build an approach for representing the semantics of negation by revealing implicit positive meanings. For instance, examples (1–3) are a selection of negated sentences taken from Blanco and Moldovan (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014: 508) that carry an implicit positive meaning.

1. (a) John did not build a house to impress Mary.

(b) John build a house (for another purpose). (Underlying positive meaning)

2. (a) I do not have a watch with me.

(b) I have a watch (but it is not with me). (Underlying positive meaning)

3. (a) They did not release the UFO files until 2008.

(b) They released the UFO files in 2008. (Underlying positive meaning)

In examples (1a) and (2a), the implicit positive statement is obtained by removing the focus of negation and the negation cue, resulting in (1b) and (2b). In example (3a), other modifications are needed, for instance, a change in the preposition (“in 2008” (3b)). In this way, it is possible to obtain a positive statement, which is implicitly included in the original negated statement. Therefore, new knowledge (positive statements) can be obtained and, at the same time, this criterion is helpful for the identification of the focus.

This criterion is applicable only in restricted cases, mainly when the focus is the most oblique argument. In Section 4, we identify the cases in which this criterion is applicable. Henceforth, we will refer to this criterion as the “positive implicit meaning” criterion.

Blanco and Moldovan’s corpus has been used by different researchers to carry out experiments on the focus of negative expressions. Morante and Blanco (Reference Morante and Blanco2012) used part of this corpus (3544 instances)—which they called the PB-FOC corpus—as a training and test corpus in the Focus Detection Task held as part of the “2012 SharedTask: Resolving the scope and focus of negation.”

Anand and Martell (Reference Anand and Martell2012) re-annotated 2304 examples from the PB-FOC corpus in terms of questions under discussion (QUD, Rooth Reference Rooth1996) revising the annotations and proposing a different model that incorporates the pragmatic concept underlying QUD, in which the focus is determined by coherence discourse constraints. Banjade, Niraula and Rus (Reference Banjade, Niraula and Rus2016) developed the Deep Tutor Negation corpus (DT-Neg), a corpus of English dialogues that contains 1088 instances of negative structures and for which they also followed the QUD model to identify the focus.

Kolhatkar et al. (Reference Kolhatkar, Wu, Cavasso, Francis, Shukla and Taboada2019) annotated with negation cues, scope, and focus 1043 comments from the SFU Opinion and Comments Corpus (SOCC), a collection of opinion articles, and the comments posted in response to the articles. They followed the criteria proposed by Blanco and Moldovan (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014) considering the focus of negation to be the element intended to be false and carrying the most meaningful information.

It is also noteworthy the work carried out by Altuna, Minard, and Speranza (Reference Altuna, Minard and Speranza2017), who annotated two corpora in Italian: a news corpus containing 71 documents (1290 sentences) from the Fact-Ita-Bank (Minard, Marchetti, and Speranza Reference Minard, Marchetti and Speranza2014) and a corpus of 301 tweets used as a test set for the FactA pilot task (Minard, Speranza, and Caselli Reference Minard, Speranza and Caselli2016). Footnote b In both cases, the annotation includes the scope, the negation marker, and the focus of negation for the purpose of studying temporal information and factuality.

Matsuyoshi, Otsuki, and Fukumoto (Reference Matsuyoshi, Otsuki and Fukumoto2014) annotated the focus of negative expressions in a Japanese corpus consisting of reviews and newspaper articles. The review corpus consists of 5178 sentences and the newspaper corpus consists of 5582 sentences. The total number of negation cues annotated is 1785, and the annotated foci are 490. They also followed the same annotation criteria as Blanco and Moldovan (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014).

All these authors agree that the linguistic context, that is, the context in discourse, is crucial for identifying the focus of negation. The way in which the context is modeled varies depending on the type of text, such as dialogues, narratives, discussions, comments, and reviews. For example, Banjade et al. (Reference Banjade, Niraula and Rus2016) work on negation in dialogues and take into account for the detection of the focus the utterance preceding the one containing the negation structure. Blanco and Moldovan (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2011) and Morante and Blanco (Reference Morante and Blanco2012) take into account the full syntactic tree in which the negation occurs and the previous and following sentences. Zou et al. (Reference Zou, Zhu and Zhou2014) demonstrate the importance of inter-sentential features for the automatic identification of focus by means of different experimental settings. Their results show that using intra-sentential and inter-sentential features together for focus detection (i.e., contextual discourse information) gives better results than only considering intra-sentential information.

Our proposal takes advantage of some of the ideas and criteria proposed by these authors, namely the positive implicit meaning, the discourse context, and the obliquity criterion. Relying on these criteria, in this article we present the linguistic analysis of the focus of negation in Spanish that is the basis for the criteria applied in the annotation process of the NewsCom corpus. The criteria we have defined are described in detail in the annotation guidelines.Footnote c

2.1 The NewsCom corpus

The NewsCom corpus, the first corpus annotated with the focus of negation in Spanish, consists of 2955 comments posted in response to 18 different news articles obtained from online Spanish newspapers from August 2017 to May 2019. These news articles cover nine topics (two articles per topic): immigration, politics, technology, terrorism, economy, society, religion, refugees, and real estate. We have only annotated those comments that contain at least one negative structure. Table 1 shows the distribution of the comments per topic in terms of total of comments (column 2), total of tokens of the comments (column 3), the number of comments containing at least a negation structure (column 4), the percentage of comments with negation (column 5), and the number of negative structures annotated with focus (column 6). Footnote d

Table 1. Distribution of comments per topic in the NewsCom corpus

In order to facilitate further comparisons, we have selected topics comparable to those in the SOCC (Kolhatkar et al. Reference Kolhatkar, Wu, Cavasso, Francis, Shukla and Taboada2019), which contains a subset of 1043 comments annotated with negation, constructiveness, and appraisal.

Comments were selected in the same order in which they appear in the time thread in the web. The corpus contains all unique comments after removing duplicates. The comments are written in informal language; therefore, we found ungrammatical comments.

57.80% of the comments (a total of 1708) contain at least one negation structure. The total number of negative structures annotated with focus is 2965. It is worth noting that 40% of the comments containing negation have more than one negative structure, because negation structures can be coordinated (4), nested (5), or juxtaposed (6).

4. [[No todos pueden][ni quieren asumirlo]].

“[[Not everybody can] [nor wants to take it on]].”

5. [No aceptáis un referéndum [no vinculante]].

“[You do not accept [a non-binding referendum]].”

6. [No hay que estereotipar el maltrato],[nunca hay justificación para ello].

“[One musn’t stereotype abuse]; [there is no justification for it].”

3. Focus of negation in the NewsCom corpus

In what follows, we present the general assumptions that we have made to build our criteria for the identification of the focus of negation in Spanish. The basic linguistic assumption on which we base our proposal is the Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 790) approach, in which the focus of negation is the part of the scope that is most prominently or explicitly negated. This approach is followed by most of the NLP researchers in this task. Regarding the scope, we follow the definition we presented in Jiménez-Zafra et al. (Reference Jiménez-Zafra, Taulé, Martín-Valdivia, Ureña-López and Martí2018), that is, the scope includes all the words affected by the negation (Demonte and Bosque Reference Demonte and Bosque1999, Española 2009). We follow the criteria of the maximum range of words affected by the negation (Vincze et al. Reference Vincze, Szarvas, Farkas, Móra and Csirik2008; Konstantinova et al. Reference Konstantinova, De Sousa, Cruz, Maña, Taboada and Mitkov2012; Francis and Taboada Reference Francis and Taboada2017). However, in contrast to these authors, we include the negative marker or cue within the scope like Morante and Daelemans (Reference Morante and Daelemans2012) and Banjade et al. (Reference Banjade, Niraula and Rus2016).

Given that our work investigates negation from the NLP perspective and is consequently based on data, that is, a corpus of real language use, we developed a framework for the annotation of focus based both on general linguistic assumptions and on empirical data obtained from the corpus. Our guidelines for the identification of the focus of negation are the result of an iterative process contrasting data and the criteria developed during the first steps of the annotation process (see Section 5). Taking into account the Huddleston and Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002) general assumption of focus, our annotation proposal assumes three criteria for identifying the most explicit negated element within the scope.

First, we consider the discourse context criterion. In our proposal, we take into account as discourse context the whole comment that contains the negation structure. We do not consider the previous and the following comments because they are not necessarily connected to the comment under analysis: the temporal thread does not guarantee that there exists a connection between a comment and the ones preceding and following it. Therefore, we take into account the inter-sentential relationships within the comments. All the comments refer to one online news article that can be considered their referential world. This news article also contains an important part of the pragmatic world knowledge necessary to understand the content of the comments. Therefore, we take into account this information in the annotation process.

Second, we consider the obliquity criterion. We assume that the most oblique argument in a sentence or in a clause is the most plausible candidate to be the focus, with the adjuncts the most oblique of the arguments. Footnote e The underlying idea is that negation affects the most specific (oblique) information, otherwise this information would not be explicitly stated, and this information is expressed because it is what we want to negate.

Third, we consider the criterion of implicit positive meaning (Blanco and Moldovan Reference Blanco and Moldovan2011, Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014), when possible: “(the focus of negation is) the element of the scope that is intended to be interpreted as false to make the overall negative true, therefore a negated statement can carry a positive implicit meaning.”

Following these semantic-pragmatic principles, we established a hierarchy of annotation criteria that we followed for the definition of the concrete guidelines described in detail in Section 4.

First of all, we distinguish between the explicit and implicit focus. The explicit focus is expressed by means of formal markers such as displacement and explicit pronominal subjects. We define the implicit focus to be when there are no formal markers for its identification. In this case, we apply the most oblique argument criterion (Guzzi et al. (Reference Guzzi, Taulé and Martí2017) and Francis and Taboada (Reference Francis and Taboada2017)), as long as the context does not give other information. Taking into account the oblique criterion, we distinguish between arguments and adjuncts. When in a negation structure there is an adjunct we consider it to be the most oblique element and, therefore, the focus. If there is more than one adjunct, we consider manner to be the most oblique argument followed by place and time, although in this specific case we are considering the possibility of accepting more than one focus in a future updated version of the corpus.

Regarding arguments, the most oblique argument will be the indirect object, followed by the prepositional object, the direct object, and the least oblique argument will be the subject. When the negated sentence contains only one verb, it will be the focus. These cases correspond to intransitive verbs without an explicit subject or adjuncts.

4. Criteria for focus identification in Spanish

In this section, we present the concrete criteria for the annotation of the focus of negation in Spanish. For this purpose, we used the NewsCom corpus as a benchmark to test our hypotheses and as a source of empirical data. We annotate the whole negation structure, which includes the negation marker or cue, the scope, and the focus.

The negation structure corresponds either to a sentence, a clause, or a phrase. In our approach, the focus is always included in the scope and corresponds to a verb form (7), an argument (8), or an adjunct (9). Arguments and adjuncts can be syntactically realized as a phrase (8) and (9) or as a clause (see Section 4.2.2, Section c). This is in accordance with Blanco and Moldovan’s (Reference Blanco and Moldovan2011, Reference Blanco and Moldovan2014) proposal, in which the focus is always the full text of a semantic argument (or adjunct).

7. [Nopasará], ya ha pasado.Footnote f

“[It isn’tgoing to happen], it’s already happened.”

8. El mierda de Kent metiéndosela con vaselina a sus votantes. Nada nuevo bajo el sol. Es lo que tiene pactar con un miserable [que no asume su responsabilidad].

“Kent is a jackass and is sticking it to his voters. That’s nothing new, it’s what happens when you do a deal with a shady guy who doesn’t keep his promises. He/She has to deal with a miserable man [who doesn’t take on his responsability].”

9. [No lo consideran así].

“[They don’t consider it to be that way].”

Example (8) demonstrates the difficulty of the task, and the importance of real world knowledge for understanding the meaning of the comment. In this comment, “Kent” stands for the Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, and the “shady guy” is Pablo Iglesias lider of the opposition party Podemos.

From a linguistic point of view, we consider that focus can be expressed explicitly (Section 4.1) by means of displacements, explicit pronominal subjects, contrastive constructions, reinforcement and typographic clues; or implicitly (Section 4.2). In the case of implicit focus, we consider that to be the most oblique argument within the scope of negation. It can be applied to simple or coordinated sentences. We go beyond the sentence that contains the negation marker to account for foci that are present in the preceding or following sentences (Section 4.3). Because of the written character of our data, we cannot take into account those cases in which the focus is marked by means of prosody, probably the clearest means for marking it.

In what follows, we present the criteria for the identification of both explicit and implicit focus, as well as elliptical scope and focus. These criteria are the result of an analysis of the Spanish language, but we think that they could also be applicable to other languages, especially Romance languages. Footnote g

4.1 Explicit focus

In Spanish, we can identify five ways to explicitly express the focus of negation in written texts: displacements, explicit pronominal subjects, contrastive constructions, reinforcement, and typographic clues. In all cases, the sentence where the negation appears can be simple or coordinated.

4.1.1 Displacements

Displacement is a focalization mechanism consisting of moving the focused element into a marked, usually fronted position (see examples (10) and (11)).

10. (a). [A su sobrino, no le había tocado un piso de protección oficial].

“[His/Her nephew, he/she hasn’t been awarded subsidized housing].”

(b). [A mi, no me parece mal introducir un poco de mentalidad anglosajona] No puede ser que en este país no se pueda tocar nada y que cualquier intento de reforma abra las puertas del infierno.

“[I, I don’t think it’s a bad idea to introduce a little Anglo-Saxon mentality]. How can it be that in this country everything is untouchable and any attempt at reform opens up the gates of hell.”

11. Eso sí, tenemos el nivel de alquiler de Europa, somos “la polla”. [Y de los sueldos europeos (de los que no disfrutamos los españoles)no dicen nada?].

“That’s right, we have the same rent prices as Europe, we are the ‘bee’s knees’. [And what about European salaries, don’t they say anything about them?].”

The indirect object A su sobrino (10a) or A mí (10b) are examples of a leftward displacement used to emphasize this constituent as the focus. In (11), the noun complement de los sueldos europeos is an example of a leftward displacement of a noun complement.

A specific type of displacement is the pleonastic focus. It happens when an argument is expressed twice in a sentence, one in a displaced position A su sobrino (10a) or A mí (10b), and the other as a pronoun—le (10a) and me in (10b)—inside the sentence and before the verb. In order to distinguish between these two focus expressions, we tag the former as pleonastic focus (displaced focus) and the latter (the pronoun) simply as focus.

Another type of displacement is the emphatic subject, that is, when the subject (Luisa or yo) is displaced to a postverbal position (12). In the case of (12b), the use of the personal pronoun yo makes the subject even more emphatic as a focus, because Spanish is a pro-drop language in which the subject may be omitted because it can be inferred from the verbal inflection (pienso is translated in English as “I think”).

12. (a) Dice [que no vendrá Luisa].

“He/She says that [it is Luisa who won’t come].”

(b) [No pienso joderme yo por su culpa], ni quitarle la posibilidad a otra persona de tener un puesto de trabajo.

“[I’m not going to get screwed because of him], or deprive another person of the chance of getting a job.”

We tag as displaced those verb arguments that have been displaced to the beginning of the sentence. We do not consider adverbial complements (adjuncts) that express time, location, and manner to be displaced focus when they appear in a preverbal position because their position in a sentence is free in Spanish.

In this kind of structures, the positive implicit meaning criterion can be applied: a positive statement can be obtained by removing the negation marker and the focus. For instance, in (10a) the underlying positive meaning is ha tocado un piso de protección oficial (a alguien), that is, somebody has been given awarded a subsidized housing.

4.1.2 Explicit pronominal subject

Spanish is a pro-drop language and the subject is not usually explicitly expressed. We consider that, in these cases, the speaker/writer wants to highlight the communicative role of the pronoun in the sentence. We consider these explicit pronominal subjects to be the focus of the negative structure when they appear with an intransitive verb (13a) or in a contrastive construction, as in (13b):

13. (a) El agnóstico es el que dice: “[Yono creo], pero no vaya a ser…’’

‘The agnostic is the one who says: “[I don’t believe], but it could be…”’

(b) [Si ellosno hacen nada], nosotros tampoco.

“[If they don’t do anything], neither do we.”

4.1.3 Contrastive constructions

Contrastive constructions, introduced by pero, no obstante, sino, Footnote h among others, help in the detection of the focus of negation as they express the element which is in contrast to the focus (14) and (15). The contrastive construction in (14) marks the focus (una religión) by introducing the alternative object un sistema político (“a political system”), which is its contrast. However, in (15) the focus is the prepositional object en mercados locales (“in local markets”) because the element in contrast is the prepositional object en mercados globales (“in global markets”).

14. [El islam no es una religión], sino un sistema político. El más agresivo de sus postulados lo defienden los salafistas financiados por Arabia Saudí.

“[Islam is nota religion], but a political system. Its most aggressive teachings are defended by the Salafists financed by Saudi Arabia.”

15. Es el mundo globalizado y ha llegado para quedarse. [Ya no se compite en mercados locales], sino en globales, donde se trabaja.

“This is the globalized world and it’s here to stay. [There is no longer competition in local markets], but in global markets, which is where we all work.”

In contrastive constructions, the positive meaning tends to be explicitly expressed in the second part of the contrast. The underlying positive meaning in (14) is “Islam is a political system” and in (15) “There is competition in global markets.” The positive meaning is introduced by the conjunction sino (“but”) in both examples.

4.1.4 Reinforcement of negation

Reinforcement is another explicit mechanism for marking the focus of negation. Reinforcements are negative constructions that contain two or more negation markers or cues. They usually consist of the no adverb and a second, usually discontinuous, negative marker, as in (16) and (17).

16. [No he defendido nuncaesto].

“[I’ve nevernot defended that].” (literal translation)

17. [No ha comprado nada].

“[He/She hasn’t bought nothing].” (literal translation)

In these cases, the implicit positive meaning criterion cannot be applied. For instance, example (16) implies that the speaker has defended another position but, in (17), saying No ha comprado nada (“He/She has not bought nothing”) does not imply that the 3rd person referent has bought something.

4.1.5 Typographic clues

Typographic clues are considered explicit markers and a strategy to emphasize one of the elements of the negation structure, the focus of negation. They include uppercase letters, bold, underlined elements, and italics. The element affected by these typographic changes is often the focus of negation (18) and (19).

18. [Yo jamás he visto A NADIE quejarse de que unos territorios gasten más que otros en pensiones].

“[I’ve never seen NOBODY complain that some territories spent more on pensions than others].” (literal translation)

19. No parecían tan listos [si no tuvieran prácticamente TODOS los medios de información bajo su control].

“They wouldn’t seem so clever [if they didn’t have ALL the media under their control].”

4.2 Implicit focus

We use the term implicit focus of negation to refer to those cases in which there are no formal markers that allow us to identify the focus. In this case, we assume that the most oblique argument or adjunct in a sentence is the most plausible candidate to be the focus. The underlying idea is that negation affects the most specific (oblique) information, otherwise this information would not be explicitly stated, and this information is expressed because it is what we want to negate.

20. Bueno, [no le atribuyamos méritos a Rajoy]. Que PDR ya se pone en ridículo él solo.

“Well, [we shouldn’t give any credit to Rajoy]. PDR makes a fool of himself.Footnote i”

21. Pero [las autoridades no pueden responder con una acción ilegal]. Si los encuentran en el Mediterráneo es posible mandarlos devuelta pero una vez en Europa hay que hacer muchas formalidades y un juez debe aprobar la deportación.

“But [the authorities cannot respond with an illegal action]. If you find them in the Mediterranean you can send them straight back, but once they’re in Europe you have to do a lot of paperwork and a judge has to approve their deportation.”

Following the oblique criterion, in (20) the focus should be a Rajoy (“to Rajoy”) because it is the most oblique argument: what is negated is not giving the credit but rather giving the credit to a specific person, Rajoy (indirect object). In this example, PDR still reinforces the focus more on a Rajoy, because it contrasts the two politicians. In (21), the focus is con una acción ilegal (“with an illegal action”) since what is negated is not that the authorities can respond but that they cannot respond with an illegal action; therefore, “with an illegal action” is the most oblique argument. Once again, the context also helps us to identify the focus, “but once they’re in Europe you have to do a lot of paperwork and a judge has to approve their deportation” highlights (or emphasizes) that illegal action cannot be their response.

In the case of implicit focus, the criterion for obtaining positive implicit meaning works better than in case of explicit focus since it facilitates the identification of focus. We use this criterion, when possible, to identify the focus.

In implicit focus, we distinguish between focus in constructions without a verbal predicate and focus in constructions with a verbal predicate.

4.2.1 Focus in constructions without a verbal predicate

Constructions without a verbal predicate can be nominal phrases, adjective phrases, or adverbial phrases. In these constructions, the negative structure is the modifier of the head of the whole construction (no muy preocupante (“not very worrying”) in (22) and sin cafeína (“without caffeine”) in (23)), and the focus of negation is the specific element negated by the negation marker (muy preocupante and cafeína, respectively), not the whole construction.

22. Un problema [nomuy preocupante].

“[A notvery worrying problem].”

23. Coca-cola[sincafeína].

“Coca-cola[withoutcaffeine].”

Note that in (22), the focus is muy preocupante (“very worrying”). Although the quantifier adverb (“very”) could be interpreted as the focus, because what is negated is the degree of the property, not the property per se, we selected the whole argument following the general criterion (see Section 3).

In these cases, the positive implicit meaning criterion is applicable. The underlying positive meaning in (22) is that there is a problem and in (23) that it is a Coca-cola.

4.2.2 Focus in constructions with verbal predicate

We distinguish two types of focus in constructions with verbal predicate: (a) when the focus is an argument and (b) when the focus is an adjunct. We describe how to represent the focus when an argument or an adjunct is expressed by a subordinate clause in subsection (c) below.

(a) Argument as focus of negation. In the case of intransitive verbs without adjuncts, the focus can be the verb or the subject (external argument) depending on the context (24). The meaning is often ambiguous, and, in these cases, we apply the oblique criterion and mark the explicit subject as the focus, when the context does not help in its identification.

24. (a) [No pasará], ya ha pasado.

“[It isnotgonna happen], it’s already happened.”

(b) No tengo ni idea de si hay un enriquecimiento para alguien con ese sistema, yo solo pretendo decir [que ese sistemano funciona].

“I have no idea whether someone is getting rich off this system, I only mean [that this system isn’t working].”

(c). [Estono cambia].

“[This won’t change]”.

In example (24a), the focus is the verb pasará (“is gonna happen”), whereas in (24b) the focus is the subject ese sistema (“this system”). In both cases, the interpretation of the focus depends on the content of the context: the second clause in (24a) and the previous sentence in (24b). However, if we did not have access to this information, we would apply the oblique criterion and the focus would be the subject (24c).

In the case of existential verbs, the focus of negation is the internal argument, that is, the existential subject, because the verb is lexically empty (Morante, Schrauwen, and Daelemans Reference Morante, Schrauwen and Daelemans2011) (25).

25. [No hay trabajo].

“[There isn’tany work].”

In the case of verbs with two arguments, that is, transitive verbs (26), copulative verbs (27), and verbs with a prepositional object (28), the focus of negation is the direct object, the attribute, and the prepositional complement, respectively.

26. [No se especifica el precio].

“[The price is not specified].”

27. [La fe no es premoderna] y tampoco es ninguna superstición.

“[Faith is notpremodern], and neither is superstition.”

28. Los catalanes se quieren ir y España aun se pregunta por qué. [España no reacciona ante estas barbaridades] y además lo dicen tan tranquilos y la gente no reacciona.

“The Catalans want to leave and the Spanish are still asking themselves why. [Spain isn’t reacting to these atrocities] and what’s more they show no qualms and the people don’t react.”

Ditransitive verbs require three arguments: subject, direct object, and indirect object or prepositional complement. The criterion applied in these cases is to consider the most oblique argument as the focus (29).

29. [María no regaló la camisa a Pedro].

“[María didn’t give the shirt to Pedro].”

In the case of periphrastical verbs, we apply the same criterion as for verbs with one, two, or three arguments, taking into account the argument structure of the verb in the non-finite form (gerund, past participle, or infinitive) (30).

30. [La rabia no va a vencer al odio].

“[Rage cannot defeat hatred].”

When the focused verbal argument has a complement, the focus is the whole argument, including the head and its complements. The head of an argument can be a noun (31), an adjective (32), or an adverb (33):

31. (a). [No defiendo el modelo de capitalización].

“[I’m not defending that model of capitalization].”

(b). [No hay alternativa que valga la pena].

“[There is noalternative that is worth it].”

(c) Lo mejor es hacerse una cartera propia con ING o algún broker [que no cobre comisiones desorbitadas].

“The best thing to do is to get up a portfolio with ING or a brocker [who don’t charge astronomical commissions].”

32. Está claro [que no es tan fácil].

“It’s clear, [that it isn’tthat easy].”

33. Otra generalización: “Los británicos son ratas como ellos solos, no gastan un céntimo”. Esperemos [que a los españoles no nos etiqueten tan libremente cuando hacemos turismo].

“Another generalization: ‘the British are complete misers, they don’t spent a penny’. Let’s hope [that Spanish tourists don’t get labelled so freely when we travel abroad].”

In these cases, the criterion of positive implicit meaning is applicable when the focus of negation is an argument (26) or an adjunct others than the verb (24a) or the subject (24b); it is also applicable when the verb is a copulative (27) or existential verb (25).

(b) Adjuncts as focus of negation. Since adjuncts are optional, their presence in negative structures denotes that they carry important information (34-36) and constitute the focus of negation.

34. [Las pruebas no han proporcionado, hasta el momento, resultados aplicables].

“[Till now, the tests have not provided appreciable results].”

35. [No quiere comer aquí].

“[He/She doesn’t want to eat here].”

36. [No puede explicarse en pocas palabras].

“[It cannot be explained in few words].”

The criterion of positive implicit meaning is also applicable. For instance, in (35) he/she does not want to eat here, but he/she wants to eat.

It is worth noting that the restrictive adverbs such as solo, solamente, únicamente Footnote j are the focus of negation. In this case, what is negated is the restriction denoted by the adverbs. In (37), what is negated is that something can be exclusively explained by culture.

37. [Eso no se explica solo con la cultura].

“[This cannot be explained solely as culture].”

(c) Focus and subordinate clauses. When the most oblique argument is a subordinate clause (a nominal or an adverbial clause) the focus is the whole clause.

Sentences (38–41) are examples in which the focus is a nominal subordinated clause with different syntactic functions: subject (38), attribute (39), direct object (40), and prepositional object (41).

38. [Lo malo no es que te guste] sino que dejes que afecte a tu vida.

“[The bad thing is notthat you like it] but that you let it affect your life.”

39. Esto parece que [no es lo que desean nuestros amados líderes].

“[This doesn’t seem to be what our beloved leaders desire].”

40. [No sé si ves la diferencia]

“[I don’t know if you can see the difference].”

41. [La gente no se queja de que hagas horas extras].

“[People don’t complain about you doing overtime].”

Sentence (42) is an example in which the focus is an adverbial subordinated clause.

-

42. [No estoy dispuesto a mentir para que consigas más ventajas].

“[I’m not willing to lie so that you can gain more advantages].”

In these cases, the criterion of positive implicit meaning is applicable in the same cases that we mentioned in Section 4.2.2a.

4.3 Discontinuous scope and elliptical focus

There are negative structures in which the scope is discontinuous, that is, part of the scope is outside of the clause containing the negation marker and the focus (43).

43. [Las pensiones se asignan] por individuo y [nopor territorio].

“[Pensions are assigned] on an individual basis, [nota territorial basis].”

In (43), the discontinuous scope is las pensiones se asignan, which is located outside of the second coordinated clause no por territorio.

In other negative structures, the scope and the focus are located in the sentence or clause that is previous to or following the one containing the negation marker. These clauses can be independent from the syntactic point of view (44) or connected by coordination or juxtaposition (45). We consider that the focus is elliptical in these cases. In (44) and (45), the scope and the focus of negation are located in the preceding clause or sentence (planes de pensiones privados “private pensions” and vivos “alive”).

44. [Planes de pensiones privados]? [No, gracias].

“[Private pensions plans]? [No, thanks].”

45. Les da igual si [llegan vivos] o [no].

“They don’t care if [they make it alive ] or [not].”

In these cases, the criterion of positive implicit meaning can also be applied, depending on whether the discontinuity occurs in a coordinated sentence (like in (43) and (45)) or in two independent sentences like in (44), and it will also depend on the number of arguments and adjuncts involved (like the cases that we mentioned in Section 4.2.2a.).

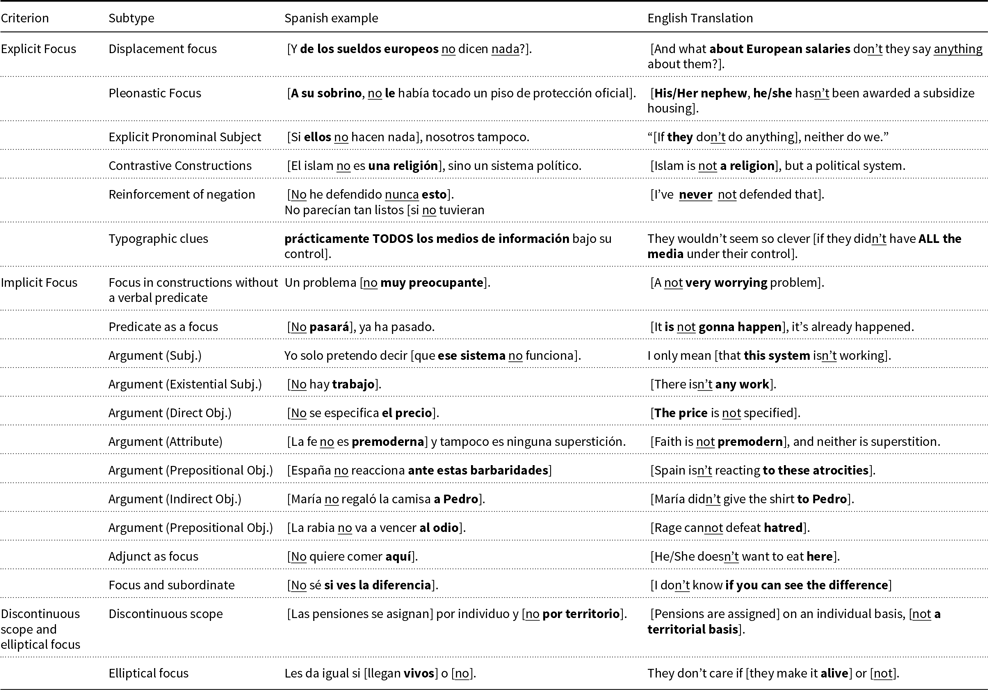

Table 2 shows a summary of the criteria applied for the annotation of the focus of negation in Spanish: the name of the criterion (column 1); the subtype criterion (column 2); an example in Spanish (column 3), and the translation in English (column 4).

Table 2. Summary table of the criteria for the annotation of the focus of negation in Spanish

5. Annotation process: Inter-annotator agreement tests

The NewsCom corpus was annotated automatically with the PoS tagger available in the Freeling open source language-processing library (Padró and Stanilovsky Reference Padró and Stanilovsky2012) Footnote k and manually annotated with negation: the negation marker, scope, and focus. The corpus was annotated by two annotators trained in the specific task of negation. Footnote l We performed the annotation process in three steps: in the first step, we annotated the negation structure including negation markers and their scope following Martí et al. (Reference Martí, Taulé, Nofre, Marsó, Martín-Valdivia and Jiménez-Zafra2016) and Jiménez-Zafra et al. (Reference Jiménez-Zafra, Taulé, Martín-Valdivia, Ureña-López and Martí2018), whose work included a complete typology of negation patterns in Spanish. In the second step, we restricted the annotation to the identification of the focus, applying and testing the previously established criteria (see Section 4). In the third and final step, we checked the whole corpus in order to verify definitively that all the criteria had been applied correctly.

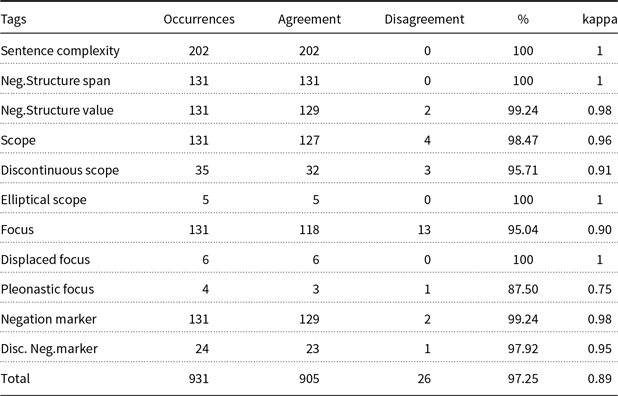

In the second step, the two annotators underwent a 2-month training program on the specific task of identifying the focus of negation. The training consisted of the annotation of a small subset of the corpus by the two annotators working in parallel without consulting the other. The training corpus consisted of 202 comments corresponding to the economy topic, which included a total of 131 different negative structures and a total of 942 tags (occurrences) that were annotated and tested. In this step, we conducted a first inter-annotator agreement test calculated on these 942 tags in order to evaluate the reliability of the annotation and the guidelines. These 942 occurrences correspond to 11 different tags, which are listed in the following paragraph. As a result of this first inter-annotator agreement test, we detected problematic cases, updated the guidelines when necessary, and then conducted a second inter-annotator agreement test using the same comments. Tables 2 and 3 below show the results obtained for each tag in the first and second inter-annotator agreement tests. As the results of the second inter-annotator agreement test were highly positive (97.25% observed agreement, 0.89 kappa), we proceeded with the annotation of the whole corpus by the two annotators who worked separately on half of the corpus each. Even then, due to the complexity of the task, we met once a week to discuss problematic cases during the whole annotation process.

Table 3. Inter-annotator agreement test (1)

The tagset used for the annotation of negative structures including the negation markers, scope, and focus is the following:

<sentence_complexity>: this tag can have two values “simple” if the sentence only contains one negative structure or “multiple” if there is more than one.

<neg coord>: is used to mark coordinated negative structures.

>neg structure>: is assigned to a syntactic structure, corresponding either to a sentence, a clause, or a phrase. It can include the attribute <polarity modifier=‘increment”> if the negation is expressed through a reinforcement (see Section 4.1.4).

<value>: indicates the meaning expressed by the negative structure. This tag has four values, which label whether the negation structure indicates negation, contrast, comparison, or structures including a negative marker but which do not negate.

<scope>: delimits the part of the negative structure that is within the scope of the negation.

<discontinuous_scope>: indicates when part of the scope, but not the focus, occurs in the sentences preceding or following the sentence containing the negative structure.

>elliptical_scope>: is used when the scope and focus occur in the sentences preceding or following the sentences containing the negative structure.

<negexp>: includes the word or words that express negation. Negation in Spanish can be expressed by one or more than one negative element. In the latter, the elements can be continuous or discontinuous. In that case, negation cues show the attribute <discid>.

<focus>: indicates the element directly affected by negation. This tag can have the attribute <pleonastic_focus> when the focus is displaced and repeated.

<displacement_focus>: indicates when the focus is displaced to a fronting position.

The criteria applied for the evaluation of the inter-annotator agreement test were the following:

1. In the case of tags related to sentence complexity (with two possible values) and negative structure (with four possible values), we consider there is disagreement when the annotators assign different values to these attributes and we consider that there is agreement when they assign the same value.

2. In the case of negation markers and discontinuous negation markers,Footnote m we consider there is agreement when the annotators tag the same exact word(s) as negation markers.

3. For the rest of attributes, we consider there is agreement when the span of the negative structure, focus, and scope match exactly, if the span coincides partly or does not match at all it counts as disagreement.

We want to highlight the fact that only exact matches had been considered as agreement, which is a strict criterion, making our data more reliable. We calculated observed agreement and Cohen’s kappa (Cohen Reference Cohen1960). Tables 3 and 4 show the results obtained for each tag in the first and second inter-annotator agreement tests.

Table 4. Inter-annotator agreement test (2)

The results of the first inter-annotator agreement test are summarized in Table 3. The observed agreement obtained was 91.76% (0.83 kappa). Most of the disagreements arose from issues concerning the discontinuous and elliptical scope—specifically in the delimitation of the scope—and “displacement focus,” due to a misunderstanding in the interpretation of this tag and “pleonastic-focus.”

Regarding the discontinuous scope, the two annotators disagreed on which exact words should be considered to be the first part of the discontinuous scope (tagged as discount_scope1). Thus, one of the annotators marked a wider context as discontinuous scope with the idea that the whole discourse was necessary in order to fully understand the subsequent negative structure. In contrast, the other annotator chose as discontinuous scope only the words necessary to reconstruct the subsequent sentence. Example (46) shows the difference between a narrower (46a) and wider (46b) discontinuous scope.

We finally agreed on a narrower discontinuous scope and marked only the words that would help reconstruct the negative structure.

46. (a) [Las pensiones se asignan]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

por individuo y [ no

por territorio]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

por individuo y [ no

por territorio]

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.“[Pensions are assigned]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

on an individual basis, [not

a territorial basis]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

on an individual basis, [not

a territorial basis]

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.”

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.”(b) [Las pensiones se asignan por individuo]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

y [ no

por territorio]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

y [ no

por territorio]

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.“[Pensions are assigned on an individual basis]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

, [not

a territorial basis]

$_{discount\_scope1}$

, [not

a territorial basis]

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.”

$_{discount\_scope2}$

.”

As for the pleonastic focus, both annotators disagreed on which one of the two pronouns should be marked as pleonastic in the examples in which an indirect object was repeated. After some discussions in which disagreements were analyzed, we decided to mark as pleonastic the displaced focus in examples like (47a), that is A mí, as this is the pronoun that could be eliminated from the sentence. In contrast, the pronoun me must appear in the sentence, otherwise it would be ungrammatical (47b).

47. (a) [A mí <pleonastic> nome parece mal introducir un poco de mentalidad anglosajona].

“[I, I don’t think it’s a bad idea to introduce a little Anglo-Saxon mentality].”

(b) [ A mí no parece mal introducir un poco de mentalidad anglosajona].

Another source of disagreement was determining the focus when there was more than one adjunct that could be interpreted as the focus and the context did not contain enough information for its identification. This dilemma tends to arise when manner, time, and location are present in the same negative structure. For instance, in example (48), one annotator selected con una buena vigilancia (48a) and the other aplicando medidas drásticas (48b), and both can be interpreted as the focus.

48. (a) [Eso no debería ser posible con una buena vigilancia aplicando medidas drásticas].

“[That wouldn’t happen if there was adequate supervision applying extreme measures].”

(b). [Eso no debería ser posible con una buena vigilancia aplicando medidas drásticas].

“[That wouldn’t happen if there was adequate supervision applying extreme measures].”

When the context does not give a cue for disambiguating the focus, the annotators do not always agree in their selection. Therefore, this is a source of disagreement that is difficult to eliminate. We are considering the possibility of accepting either more than one focus when such ambiguity occurs or considering the last element in the sentence to be the focus (aplicando medidas drásticas). At the moment, in these cases, the selection of the focus depends on the criterion of each individual annotator. All these disagreements correspond to the most difficult cases to solve and are concentrated in very specific constructions characterized by discontinuous and elliptical scope and when more than one adjunct can be the focus. The detection of these disagreements has allowed us to correct them in the last revision of the corpus.

After a revision of the criteria adopted, the updating of the guidelines, and a discussion of the problematic cases, a second inter-annotator agreement test was conducted, in which a total average of 97.25% of observed agreement (0.94 kappa) was obtained, which is almost perfect following Landis and Koch kappa’s benchmark scale (Landis and Koch Reference Landis and Koch1977), given the complexity of the task (see Table 4). We found 26 cases of disagreement, half of which corresponded to the identification of the focus, especially when there were two possible candidates to be the focus (48).

We can conclude that weekly meetings definitely helped annotators reach a higher agreement, as problematic cases were widely discussed. However, we have not measured the impact of these meetings on inter-annotator agreement, although we are certain that they were useful for training the annotators and helped us to establish clearer criteria, especially when dealing with cases of pleonastic focus, elliptic scope, and how to identify the focus.

We used the AnCoraPipe Footnote n tool for the annotation of the NewsCom corpus and the corpora texts annotated were XML documents with UTF-8 encoding.

5.1 Quantitative analysis

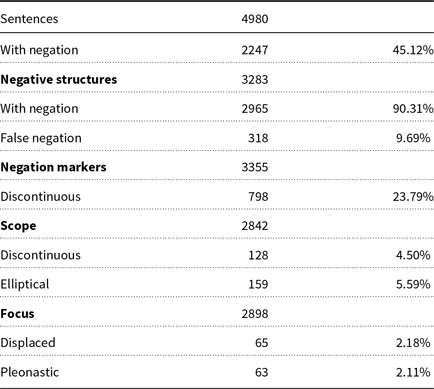

In Table 5, we present relevant data resulting from the annotation of negation.

Table 5. Distribution of negative structures, negation markers, scope, and focus

The NewsCom corpus contains 4980 sentences, of which 2247 (45.12%) contain at least one negative structure. The total number of negative structures is higher than the number of negative sentences because some sentences contain more than one negative expression. It is worth noting that 7.69% of the negative structures do not express a negative meaning. For instance (49) and (50):

49. Pues no os queda por tragar todavía.

“There is a lot more to come.”

50. No hay ideología más criminal que el neoliberalismo.

“There is no ideology more criminal than neoliberalism.”

In these examples, negation markers in these contexts do not have a negative value but rather a rhetorical one as in (49) or are part of a comparative construction as in (50) (see Jiménez et al. 2018).

The number of negation markers (3355) is higher than the number of negative structures because some of these markers are discontinuous (23.79%) and contain two or more negation markers (see Section 4.1.4). Table 6 contains the most frequent negation markers and discontinuous negation markers in the corpus.

Table 6. Top 10 negation markers

Regarding the scope, 5.59% of cases are elliptical, meaning that the focus (as part of the scope) is located in one of the previous or following sentences. Whereas the scope is discontinuous in 4.50% of the cases, that is, part of the scope (but not the focus) is located in one of the previous or following sentences (see Section 4.3).

Finally, the NewsCom corpus contains a total number of 2898 foci of which 65 (2.18%) correspond to displaced focus and 63 (2.12%) to pleonastic focus.

In order to get a clearer idea of the frequency of each phenomenon related to the focus of negation, we have calculated how the focus is expressed in a sample of the corpus. To do so, we have selected four topics: economy, refugees, terrorism, and technology. This sample includes 1197 negative structures that contain a focus (we have excluded from our consideration negative structures that do not express negation). We offer, for each topic, the relative frequency of each type of focus in relation to the total number of negative structures that include a focus.

Tables 7 and 8 show the distribution of the explicit and implicit focus, respectively.

Table 7. Distribution of explicit focus

Table 8. Distribution of implicit focus

As we can see in Table 7, explicit focus is much less frequent than implicit focus in all the topics we have analyzed. If we take into account typographic clues, for example, we can see that it is a very residual phenomenon. It is worth noting that reinforcement is the most common explicit focus type. In contrast, the majority of focus are implicitly expressed in negative structures (Table 8). A relevant number of negative structures show an adjunct as the focus of negation (although this number can vary from 7.27% in the economy domain to 1.26% in the terrorism domain) and, lastly, all topics show a clear preference for expressing the focus through an argument. Thus, around 60% of the negative structures show an argument (such as the direct or indirect object) as the focus of negation. Examples where the focus of negation is in constructions without a verbal predicate are also very scarce.

6. Conclusions and future work

In this article, we have presented the criteria for the identification of the focus of negation in Spanish. We have distinguished between explicit and implicit focus, guided by whether formal explicit markers are used to emphasize the relevant information (explicit focus) or not (implicit focus). When these markers are not present, we apply the criterion of the most oblique argument, as long as context does not provide any other information, with adjuncts being more oblique than arguments. We have also taken into account the positive meaning criterion when possible.

We tested the adequacy of these criteria by annotating the NewsCom corpus. The annotation process involved an in-depth linguistic analysis of the focus of negation through which we identified some 10 different types of specific criteria that cover a wide variety of constructions containing negative expressions. This corpus is a new linguistic resource containing 2955 comments, 1780 of which contain at least one negative structure. We assume that with this number of negative structures we have covered the main phenomena involved in the expression of negation in Spanish.

The annotation of the corpus was tested by applying inter-annotator agreement tests in the training phase of the annotation process, which obtained a total average of 97.25% of observed agreement (0.89 kappa), which is almost perfect following Landis and Koch kappa’s benchmark scale (Landis and Koch Reference Landis and Koch1977). The criteria were applied to Spanish, but we believe that they could also be useful for other languages.

Although the identification of the focus of negation is crucial in several NLP applications, especially for obtaining reliable information, it has received scant attention in NLP. Our aim is to contribute to the study of focus by creating a new linguistic resource, the NewsCom corpus, on which the criteria we developed were applied. This new resource provides empirical data that can be used for theoretical studies and for training systems in the identification of focus of negation.

As future work, we will first take advantage of the knowledge acquired to develop an automatic system for the detection of negation including the negation marker, scope, and focus. Second, we will analyze the relationship between negation and factuality.

Acknowledgments and Financial support

This work was supported by the MISMIS-Language project (PGC2018-096212-B-C33), which receive financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, and by the 2017 SGR 341 project from the Generalitat de Catalunya (AGAUR).