“All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players …”

William Shakespeare, As You Like ItThe Ukraine crisis, which led to president Yanukovych’s flight from Ukraine, the subsequent Russian annexation of Crimea, and the conflict in Donbas, provides an excellent illustration of how narratives are exploited in political dialogues. The report on the panel of eminent persons held under the auspices of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe admitted that there had been often “diametrically opposed narratives” among the West, Russia, and the states in-between (Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine) (OSCE 2015, 2).Footnote 1

Similarly, scholars adhere to contradicting narratives on the Donbas war, which have been formulated based on their assessment of the degrees of local separatism and Russian participation in the armed conflict. Some stress endogenous causes, arguing that “the armed separatist movement emerged in direct response to the violent regime change that took place in Kyiv” (Kudelia Reference Kudelia2014, 1), and that the “Russia factor” is “a contextual variable” that only aggravated “long-lasting structural deficiencies of the Ukrainian political system” (Sotiriou Reference Sotiriou2016, 57). Matveeva (Reference Matveeva2016), Suslov (Reference Suslov2017), and Matsuzato (Reference Matsuzato2017) also focus on the indigenous actors and processes of “Novorossiya” (New Russia) and the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic” (the DPR) and “Luhansk People’s Republic” (the LPR). In contrast, Umland (Reference Umland2014) contends that the Donbas insurgency was “an only partially domestic event.” Wilson (Reference Wilson2016) likewise maintains that “there is a world of difference between joining in a civil conflict or civil war and either starting it or enabling its escalation,” (632) while admitting the fact that two-thirds of civil wars involved foreign intervention.

This article explores the role of the Kremlin in the development of the conflict in eastern Ukraine by analyzing the leaked communications of Putin’s aide on Ukraine, Vladislav Surkov, and other covert actors. Surkov was a deputy chief of the Presidential Administration from 1999 to 2011, known as the “supreme PR man” (Wilson Reference Wilson2005, 51) and the ideologue of “sovereign democracy.” Etkind believes that Surkov’s mission is to present “Russia’s people of all classes and ethnicities as intrinsically violent and ultimately incapable of democratic self-rule” and “the twenty-first-century’s modernity as the rule of secret conspiracies and managed simulacra” (Etkind Reference Etkind2013, 238).

Based on an empirical description of Surkov’s political technology methods with specific projects tailored to ensure Moscow’s plausible deniability in the conflict, I argue that Russian policy toward Ukraine is an extension of its “virtual” domestic politics (Wilson Reference Wilson2005). The findings will provide a basis for understanding contemporary Russian hybrid warfare that makes full use of its political technology methods.

The article begins with an overview of sources and approach of the research, including the background of the Surkov and Frolov leaks. Next, the article examines the preparatory phase of the Kremlin’s Donbas policy, highlighting the establishment of Surkov’s team in 2013 and its scope of interest. Importantly, Surkov’s instruments were not limited to within his official competence; resources of a Russian oligarch and sponsor of the Russian Orthodox Church Konstantin Malofeev appeared to have been incorporated into the expanded Surkov team by the end of 2013. The following section details the implementation of Russian clandestine activities to “raise up people” in the southeast of Ukraine in spring 2014. Although the early attempts of destabilization were supervised by Putin’s adviser on Eurasian integration Sergey Glazyev, these operations could be seen as integral parts of Surkov’s scenario because Glazyev had been hierarchically put under control of Surkov in the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy as early as September 2013 (Hosaka Reference Hosaka2018, 346–347). The article further elaborates on Surkov’s management of the DPR/LPR in terms of human resources, economy, and media, as well as promotion of the myth of Novorossiya. In particular, this article scrutinizes how Moscow modified its rhetoric on the southeast of Ukraine as it invaded the Ukrainian Donbas in August 2014 and, simultaneously, launched efforts to create the image of a strong Donbas leader. The final section summarizes the findings on Surkov’s political technology methods to ensure plausible deniability and discusses implications for tactics and strategic goals of the Kremlin in the Donbas.

Sources and Approach

In the fall of 2016, email accounts allegedly belonging to Surkov were made public by patriotic Ukrainian hackers. The leaked communications have been triangulated with other open-source information and verified by multiple independent experts.Footnote 2 The leak was done in three installments. The first leak dated October 23, 2016 only publicized a screenshot of the electronic message and attached documents allegedly sent from a Pavlov to Surkov’s webmail account dated August 26, 2016 (“Kiberkhunta peredaet privet Surkovu” 2016). The second leak came out a few days later with a data dump of the official account of Surkov (prm_surkova@gov.ru), amounting to 1 GB, including more than 2,400 email messages during the period from September 2013 to November 2014 (“Den’ Surka” Reference Surka2016).Footnote 3 The third leak that appeared in the following month covered the correspondence of another webmail account (pochta_mg@mail.ru) attributed to Surkov, including 435 emails (340 MB) from 2015 to 2016.Footnote 4 Following the Surkov leaks, in December 2016, an email box of Kirill Frolov, a religious expert of the Institute of CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) Countries headed by the Russian State Duma deputy Konstantin Zatulin, was disclosed in a similar manner.Footnote 5

Most of the communications contained in the Surkov leaks are regular media monitoring reports circulated in the Presidential Administration, and we are not able to find any “super-secret plans.” But the leaks also contain dozens of meeting agendas and participant lists, as well as project proposals offered to Surkov. To understand Surkov’s work methods, one could refer to Peter Pomerantsev, a British journalist of Russian origin, who worked as a TV producer in Moscow during the 2000s:

… Surkov has directed Russian society like one great reality show. He claps once and a new political party appears. He claps again and creates Nashi, the Russian equivalent of the Hitler Youth…. As deputy head of the administration he would meet once a week with the heads of the television channels in his Kremlin office, instructing them on whom to attack and whom to defend, who is allowed on TV and who is banned, how the President is to be presented, and the very language and categories the country thinks and feels in….

(Pomerantsev Reference Pomerantsev2014, 65)The Surkov leaks have confirmed the observations of Pomerantsev. As shown in the leaks, Surkov hosts a meeting and gives key parameters to the participants, and after a while, the future “curators” (project managers) propose specific projects to Surkov. Collation and comparison of the leaked communications with open-source information allow us to analyze project coordination processes, and hint Surkov’s intentions behind each project, contributing to the understanding of the Kremlin’s tactical and strategic insights into Ukraine at the time of the correspondence.

Although the Surkov leaks are vast primary source collections that provide us valuable insight, little comprehensive research has been done on this body of sources so far.Footnote 6 This article examines the leaked correspondence with a view to illuminating Surkov’s roles in the Donbas, focusing on the period from the fall of 2013 through 2014, with partial reference to his activities in 2015–2016. As a matter of fact, Surkov’s influence operations were not limited to the boundaries of the Donbas, but included other cities and areas of the country (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Zakarpattia, etc.); however, this article confines itself to analyzing his activities in the Donbas.

Team Building in 2013

Surkov and His Domestic Politics Team

In May 2013, Surkov was dismissed from the position of deputy prime minister reportedly for taking exception to Putin’s economic policy, but in September the same year he came back to the Kremlin as the Presidential Aide to supervise the Presidential Directorate for Social and Economic Cooperation with the CIS Member Countries, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Soon after the appointment, Surkov called his former domestic politics team back to staff his directorate. First, on October 11, Putin appointed Oleg Govorun, Surkov’s right hand, who served as head of the Presidential Domestic Policy Directorate (2006–2011) and Minister of Regional Development (2011), as new head of Surkov’s directorate (President of Russia 2013). Further, on November 21, Boris Rapoport, who had gained experience in domestic politics under Surkov and Govorun over ten years, was appointed deputy to Govorun and placed in charge of political issues in Ukraine.Footnote 7 Another one of Govorun’s deputies, Mikhail Mamonov, is a former head of the international department of Rosmolodezh, the Federal Agency on Youth Issues (managed by a faithful henchman of Surkov, Vasily Yakemenko), who joined Surkov’s directorate not later than the beginning of October.Footnote 8 In addition, Surkov invited the director of the Center for Current Politics, Alexey Chesnakov, a former deputy head of the Presidential Domestic Policy Directorate (2001–2008) to monitor and frame public opinion on the Ukraine crisis. In September 2013, calling the appointment of Surkov to the position of Presidential Aide “strategic,” Chesnakov told the media: “Obviously, Russia’s policy toward Ukraine and Georgia should be more variable and more creative, because there are some dead ends” (The New Times, September 21, 2013). The leaks show that Chesnakov did not hold an official position in the Kremlin, but indeed attended important meetings together with Surkov’s directorate’s staff. In mid-November 2013, there were still vacancies in the directorate.Footnote 9 Surkov took part in the discussion event held at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations on December 19, and recruited one of the young talented participants, the head of the Russian youth delegation to the G20, Inal Ardzinba.Footnote 10

Scope of Interest of the Directorate

The office entrusted to Surkov’s management, Directorate for Social and Economic Cooperation with the CIS Member Countries, the Republic of Abkhazia, and the Republic of South Ossetia, was established upon the start of Putin’s third presidential term in the spring of 2012. Then ex-health minister Tatiyana Golikova was appointed the Presidential Aide to supervise this new directorate. The official name of the directorate gives a false impression that it engages with all CIS countries in addition to Abkhazia and South Ossetia; this is only true in the legal documents on the establishment of the office.Footnote 11 Before Surkov came in, this directorate mainly dealt with the two regions of Georgia—Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which Russia recognized as independent states during the Russo-Georgian war in 2008—whereas Ukraine and other CIS countries were said to remain within the responsibilities of the Directorate for Interregional and Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries headed by Vladimir Chernov (Il’ya Ponomarev 2017; Surnacheva, Gabuev, and Sidorenko Reference Surnacheva, Gabuev and Sidorenko2014).

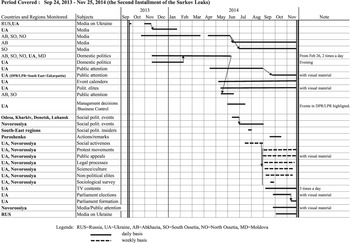

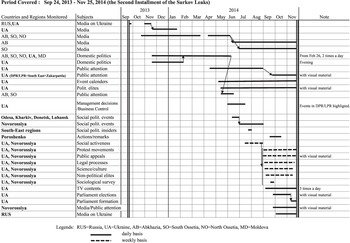

In the Surkov leaks, we can identify multiple monitoring reports made by the Kremlin’s in-house and outsourced experts regarding the social and political circumstances of their target countries and regions—valuable clues that help us to identify major focuses of the directorate and their shifts at specific time periods (see Figure 1). The combination of countries and regions to be monitored confirms that Surkov’s new office was primarily engaged in Ukraine, together with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, but did not follow events of any other CIS countries except Moldova. The Surkov leaks contain little evidence of active involvement of the directorate in Chișinău’s issues, but Surkov’s meeting with President of the “Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic”, Evgeny Shevchuk, on December 25, 2013, hints that he was interested not in Moldova proper but in its breakaway republic.Footnote 12 It is thus noteworthy that as early as summer 2013, when there were no signs of “separatism” and no one could imagine “disintegration” of Ukraine, Surkov was appointed the Presidential Aide to supervise the directorate that de-facto deals with the internationally unrecognized republics in the post-Soviet space, with the renewed focus on Ukraine.

Figure 1. Regular monitoring activities of the Directorate for Cooperation with the CIS Countries, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia.

Unofficial Resources of the Kremlin

Surkov’s instruments were not limited to the official competence of the directorate. In the course of the Ukraine crisis, Konstantin Malofeev, president of the Moscow-based investment fund Capital Partners, first surfaced in the media coverage in May 2014, when Alexander Borodai and Igor Girkin (Strelkov), who Malofeev present as a “consultant” and the “security chief” of his company, appeared in Eastern Ukraine as “prime minister” and “defense minister” of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic”. Scholars often wonder whether Malofeev acted on behalf of Moscow, or if he acted independently (see Kofman et al. Reference Kofman, Migacheva, Nichiporuk, Radin, Tkacheva and Oberholtzer2017, 60), but the Frolov leaks suggest that Malofeev’s resources had been counted on by the Kremlin, and specifically by Surkov, as covert instruments for its operations in Crimea as well as the Donbas. On September 12, 2013, Malofeev’s assistant Alexei Komov told Frolov that Malofeev “has concrete proposals and resources” and offered to arrange a meeting with Frolov’s supervisor Glazyev in order to discuss “the salvation of Ukraine from the homo euro of integration.”Footnote 13 Frolov communicated this proposal to Glazyev: “This is Rostelecom’s chief. He has financial and media resources.”Footnote 14 Glazyev visited Malofeev in his Moscow office on September 16.Footnote 15 More to the point, having learned that Malofeev would visit Surkov regarding “Orthodox issues in Ukraine” in mid-November 2013, Frolov insisted that Glazyev seize the initiative and recommend Malofeev to Surkov directly.Footnote 16 Thus, by the end of 2013, Malofeev and his resources seemed to have become part of Surkov’s expanded team—an assumption which was confirmed by Malofeev’s visit to Crimea with Russia Duma deputy Dmitry Sablin at the end of January 2014. Disguised as a religious tour, the visit aimed to co-opt the leadership of the Crimea Autonomous Republic (Hosaka Reference Hosaka2018, 361).

The Donbas Theater

“Raise Up People” in the Southeast

The content of the Frolov leaks is highly congruent with the intercepted telephone records of Putin’s advisor Glazyev, which were publicized by the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office in August 2016 (the so-called “Glazyev tapes”). According to the Glazyev tapes, on February 27, 2014, soon after the Euromaidan revolution and the ouster of president Yanukovych, Glazyev discussed immediate organization of mass protests with the director of the Institute for CIS Countries, Konstantin Zatulin, and the latter named “Oplot” (Kharkiv) and “Odesskaya druzhina” (Odesa) as local organizations suitable for this task. On March 1, Glazyev told an agent named “Anatoly Petrovich” from Zaporizhia, “I have an order of the leadership to raise up people [podnimat’ lyudei] in Ukraine, wherever we can,” and added, “the president already signed the order.” (On March 1, the Federation Council of Russia rubber-stamped Putin’s decision on the possible use of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine.) Glazyev stressed the importance of mass appeals to Putin for protection from Ukrainian nationalists as well as resolutions of Zaporizhia’s oblast council on the non-recognition of the legitimacy of Kyiv authorities. He further urged the agent to take control of the building of the oblast council, forcing regional deputies to vote for necessary resolutions. On the same day (March 1), Glazyev had a similar conversation with Frolov and the leader of “Odesskaya druzhina,” Denis Yatsyuk (Conflict Intelligence Team 2016).

It is no wonder that the Russian Orthodox Church, which in tandem with the Kremlin took a firm stance against Ukraine’s EU integration course in 2013,Footnote 17 continued to participate in the Kremlin’s adventure in the southeast of Ukraine.Footnote 18 According to the Frolov leaks, on March 4, 2014, Frolov wrote to Odesa’s Orthodox priest Andrey Novikov: “We held a meeting with the big bosses. No refusal to deployment of the troops. But you need maximum activation of regions. Now I have become a curator of Odesa and Mykolaiv regions. Personally, in front of me, the KFZ [Konstantin Zatulin] negotiated to help Odesa.”Footnote 19

Frolov urged Novikov to make someone appeal to Putin with the public statement of the following content: “The junta [Ukrainian government] took the Church of the Moscow Patriarchate hostage” and “the majority of Orthodox believers of Ukraine are waiting for the Russian [military] contingent.” Furthermore, Frolov tried to assure Novikov of the strong support of the highest clergy of Moscow: “o. Vsevolod [Speaker of the Russian Orthodox Church] showed it [the text of the statement] to BOSS [Patriarch Kirill] and received the blessing to make it an appeal of the Orthodox public organizations to VVP [Putin].”Footnote 20

Odesa and Mykolaiv: Failed Attempts

However, the Kremlin’s staging of “mass protests” did not bring about the desired effects. The leaks show how the quick and firm responses of the Ukrainian law-enforcement agencies intimidated a handful of fringe pro-Russian activists in the region. On March 4, Novikov complained to Frolov that Ukraine’s security service and prosecutor office were threatening organizers of the March 6 occupation of the Odesa oblast council with arrests.Footnote 21 On March 6, Novikov heard that the Ukrainian new authorities stormed the Donetsk oblast state administration and arrested the self-proclaimed “people’s governor” Pavel Gubarev and dozens of activists occupying the building. Apparently, Novikov got scared by this news, and wrote to Frolov: “In Donetsk, they did everything in accordance with the Russian instructions, as Sergey Yu-ch [Glazyev] told us to do. Now this is the moment of truth. Will Putin, as he promised, come with the army ‘in case of repression against Russian-speaking citizens’ to release Gubarev and 70 Russian-speaking activists thrown into jail[?]”Footnote 22 Novikov soon halted his participation in the project and fled to Russia.

According to the Glazyev tapes, on March 3, 2014, Odesa’s pro-Russian activist Valery Kaurov made a phone call to Glazyev’s office. Having said that he had stormed the Odesa oblast council, Kaurov repeatedly requested immediate assistance from Moscow (Conflict Intelligence Team 2016). The needed assistance, however, appeared not to have been provided to Kaurov. As the Frolov leaks show, the next day (March 4) Kaurov complained to Frolov in writing about the appointment of the new regional governor and heads of law enforcement agencies, as well as a lack of his interaction with the structures of another leader in Odesa, Anton Davidchenko, and stated that “without help from other regions incl. the Crimea, we can not do anything serious here.” Nevertheless, he argued that the next council session scheduled for March 6 would be the last chance to “legitimately press the deputies and achieve the desired results,” adding, “repeating the events of Monday [March 3] with the street forces—it makes no sense and it will not lead to success.”Footnote 23 But the attempts ended up in vain, and Kaurov fled to Moscow, where in mid-April he declared himself the “people’s president” of “Odesa People’s Republic,”Footnote 24 “acting based on instructions [vvodnye] from Moscow.”Footnote 25 According to Frolov’s message to Glazyev, another local pro-Russian leader “Davidchenko ‘lay’ in the hospital, to escape from the interrogation by the SBU [the Security Service of Ukraine], leaving Kulikovo square [Central Square in Odesa] unattended, and no one even approaches the microphone.”Footnote 26

For Mykolaiv, another oblast that Frolov was placed in charge of, he was recommended by Odesa’s priest Novikov to contact his brother Yury Riske, a key anti-Maidan activist in Mykolaiv.Footnote 27 On March 6, Riske reported to Frolov: “on March 1 there was a large rally (for Mykolaiv), more than 10 thousand people. They chanted: ‘Russia’, ‘Sevastopol’ and anti-fascist slogans, marched down the central street.” Riske recommended to Frolov “Konstantin” as “the most active leader” who is “able to manage a crowd.”Footnote 28

On March 13, Frolov hurried his supervisor Glazyev over the implementation of a “people’s referendum” scheduled on March 16 in Mykolaiv, sending electronic data of ballot that, he says, should be in print within hours. The original ballot included two questions: “1. Do you support the federal structure of Ukraine?” and “2. Do you support the establishment of Novorossiya Federal Area [federativnyi okrug] including Mykolaiv, Odesa and Kherson oblasti within Ukraine?”Footnote 29 In a few hours, Glazyev’s assistant Sergey Tkachuk sent back the file, replacing the second question with the more moderate one: “Do you support Ukraine’s accession to the Customs Union with Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia?”Footnote 30 In fact, there was skepticism from the beginning; some colleagues of Frolov said that there was “no chance in the southeast” because locals were “all pro-Ukraine.”Footnote 31 The initial “Novorossiya” project was thus postponed by Glazyev or possibly Surkov, who stood behind him.

On March 14, “the protest movement is calming down” in Mykolaiv. Riske wrote to Frolov, “There are no new forces. Konstantin (local organizer) was taken to the SBU on March 13 just from the hall before the press conference.”Footnote 32 Instead of the arrested leader, Frolov got in touch with the head of the local branch of the Russian Bloc, Evgeniya Bondarenko, who was “preparing the campaign of the People’s Referendum on March 16” in Mykolaiv,Footnote 33 and advised her to call Tkachuk or Marat Musin (the founder of ANNA News, the pro-Kremlin news site covering the wars in Syria and Ukraine) so that they could send their TV crews to cover the “referendum.”Footnote 34 According to a local paper, the referendum took place, but only 600 people took part in the rally held in the center of the city (“‘Narodnyi referendum’ v Nikolaeve sobral do 600 chelovek” March 16, 2014).

Donetsk and Luhansk: Radicalization under “Coordinator of Donbas”

After the failure to organize mass protests in southern oblasti, the Kremlin switched to more sophisticated approach. On March 16, 2014, Tkachuk wrote to Frolov, “In addition to the tactical tasks in the southeast, at this stage it is important for us to raise the issue of unconstitutionality and block the intentions of the so-called Kyiv government to sign the political part of the Association Agreement with the EU on March 21. It is important to promote this topic.”Footnote 35 Tkachuk sought Frolov’s advice as to who could help them so oblast councils can adopt resolutions on unconstitutionality.Footnote 36Attaching a draft resolution of the Luhansk oblast council, Tkachuk added, “Kirill, receive the draft for Irina Shablovskaya [Luhansk activist; later representative of the LPR in Moscow]. The head of the oblast council already has this paper, but it is important that it should become one of the pillars for the social movement from below.”Footnote 37 It is evident that the Kremlin hoped to refer to fake “local initiatives” to put harder pressure on Ukraine and appeal to the international community. In the middle of March, via international news agencies, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov managed to disseminate narratives calling for international support for “constitutional reforms” in Ukraine (Watanabe Reference Watanabe2017).

At first, it seemed highly unlikely that the draft resolutions written by Moscow would be passed in any of the local lawmakers’ assemblies. On March 23, the Luhansk activist Shablovskaya informed Frolov that Luhansk elites were in fact anti-Russian internally: “All local authorities in business (managers, deputies of all levels; Verkhovna Rada, oblast, city) are deadly afraid of any presence of Russia, even of the Customs Union. They will hold on for independence to the end.”Footnote 38 Not less important is Shabloskaya’s observation that “almost all the intelligentsia, university teachers, television workers, writers, artists, etc. [were] extremely aggressive toward Russia, even with hatred” and “they hate[d] Putin.”Footnote 39 Similarly, in Donetsk, as Matsuzato describes, even under the ultimatum of the so-called “coordinating council” supposedly convened by protesters after the arrest of Gubarev, most of the Donetsk oblast council deputies did not appear in the session on April 7 to adopt a resolution requesting the federalization of Ukraine (Matsuzato Reference Matsuzato2017, 190–191).

However, fringe pro-Russian groups suddenly turned to mainstream politics of the region. According to official Russian narratives, on April 7, the protesters in Donetsk announced the establishment of “people’s council of Donetsk oblast,” which in its capacity declared its intention to establish “the Donetsk Republic” and join the Russian Federation after a referendum to be held “not later than May 11,” and adopted an appeal to Russia with a request to introduce the peacekeeping contingent. In Luhansk, on April 10, the deputies of the oblast council allegedly demanded that Verkhovna Rada and the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine announce a referendum to address the issues of the state structure of Ukraine and the status of the Russian language.Footnote 40

What brought such a drastic change to the local politics in the Donbas in such a short period of time? Did the protesters impose the people’s will on the local deputies? One must stop and wonder where the aforementioned “coordinating council” emerged. An analysis paper made by “Coordinator of Donbas” Konstantin Goloskokov copied to Frolov on March 13 reported that “a coordinating council of pro-Russian actions consisting of 50 people has been formed (uniting 20 public organizations, representatives of intellectuals, university teachers, etc.),” and that they “have steady contacts with the Donetsk city council,” through which “it is possible to jam decisions.”Footnote 41 The paper further suggested supporting the protest movement with the following measures: “(1) formation of a permanently active tent camp,” “(2) supply of activists with equipment for protective and offensive operations,” and “(3) taking control of strategically important city objects and patrolling the streets.” On March 16, Frolov told Tkachuk that Goloskokov was going to “raise up Donetsk” and he had “a lot of important ideas for neutralizing [Donetsk oblast governor appointed by Acting President Turchinov] Taruta and [Donetsk oligarch] Akhmetov.”Footnote 42

Who is Goloskokov? He was originally a commissary of the pro-Kremlin youth patriotic movement Nashi. In one of his papers sent to Frolov, he introduced himself: “Goloskokov … supervised foreign policy work in the movement ‘Nashi’ in 2006–2010, including activity in Ukraine.” He further stated that he “engages in activities in Donetsk, Kherson and Mykolaiv regions and Kyiv” and that “today’s protest leaders of Donetsk, Odesa and Mykolaiv (Gubarev, Davidchenko, Evgenia Bondarenko, etc.) were trained in Seliger [Russian youth camps held by Nashi at lake Seliger] in 2009.”Footnote 43 Goloskokov also headed the monitoring group of the Nashi movement during the war in South Ossetia, and monitored elections in Georgia, Ukraine, Serbia, and Iraq. In March 2016, the Security Service of Ukraine published a fragment of the phone conversation between Goloskokov and a Ukrainian collaborator that took place on April 9, 2014, regarding the detention of a Russian saboteur, Maria Koleda. The security service suspected the former Nashi commissary was a case officer of the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, who engaged in recruitment and subversive activities in Ukraine (“SBU opublikovala novuyu zapis’ razgovora Krasnova s ‘rossiyskim kuratorom’” 2016). The Frolov leaks partially confirm the claim of the Ukrainian intelligence: on April 14, 2014, Goloskokov sent Frolov an “application for lawyers” with an attempt to release Koleda and other detainers.Footnote 44

Political technologists did their jobs. People “rebelled against the government” in Ukraine; Surkov’s drama was set into motion. While the four-party talks on the settlement of the conflict in eastern Ukraine (Russia, Ukraine, the EU, the US) were taking place in Geneva on April 17, 2014, Putin told the media that Kyiv “should talk with people and with their real representatives, with those whom people trust” (President of Russia 2014a). After the meeting, Russian foreign minister Lavrov said, “We have an understanding that the task of carrying out the [constitutional] reform will be carried out to the end and that within the framework of this reform the rights of all regions, all ethnic groups, all language minorities will be fully ensured” (“V Zheneve dogovorilis’ perepisat’ Konstitutsiyu Ukrainy” 2014).

Human Resources Control

Despite Putin’s public appeal to the “representatives of southeast Ukraine and supporters of federalization to hold off the referendum scheduled for May 11” (President of Russia 2014b), both “people’s republics” proceeded with the referendums and allegedly made Putin lose face. The leaks, however, show that Surkov was consulted in advance and was able to influence the composition of the DPR leadership. On May 13, Malofeev’s assistant sent Surkov’s secretary an email flagged “High Importance” with “List of candidates to the government of Donetsk Republic,” asking her to pass the document to Surkov at the earliest possible time.Footnote 45 The list includes 20 candidates to fill the various “ministerial” posts, with the trustworthiness of each individual checked by Malofeev’s team (possibly by Alexander Borodai). The document leaves the “prime minister” candidate blank, but offers “special recommendations to A. Khodokovsky, A. Purgin, and A. Zakharchenko (the last can be considered to the role of prime minister),” and adds that “only Khodokovsky and Zakharchenko own real armed resources in the city. The most powerful and organized is Khodokovsky’s.” A few days later, the roles were distributed to the candidates as proposed by Malofeev: “supreme council speaker” to D. Pushilin, “defense minister” to I. Strelkov, “vice prime minister” to A. Purgin, and “state security service director” to A. Khodokovsky (Naberezhnov, Sotnikova, and Artem’yv Reference Naberezhnov, Sotnikova and Artem’yv2014). The only yet significant correction made by Moscow is that commander of “Oplot” Zakharchenko was appointed military commandant of Donetsk, while the role of “prime minister” was given to Alexander Borodai, Russian citizen and political consultant of Malofeev, who had not been on Malofeev’s list. One might wonder why Surkov endorsed Borodai as “prime minister” instead of the local candidate Zakharchenko, if the latter could have given the Kremlin more plausible deniability. A possible explanation is that Surkov thought Moscow political technologist Borodai to be more easily manageable than a local unknown. It would be also convenient for the Kremlin to terminate the technical “government” at any moment, by sacking Russians, if Kyiv were to finally accept Moscow’s terms on the federalization. Igor Girkin (Strelkov), Borodai’s colleague, later testified that in the early 2000s Borodai provided a black-PR consultancy service to the Kremlin and had a working relationship with Alexander Chesnakov, who then dealt with domestic politics under Surkov,Footnote 46 and that Zakharchenko returned to Donetsk as “prime minister” after the meeting with Surkov in Rostov (Strelkov Reference Strelkov2014). Apparently, Girkin is not a trusted member of “Surkov’s theater”; Surkov’s experts continued to monitor Girkin’s statementsFootnote 47 and attempted to discredit him by using pro-Kremlin bloggers.Footnote 48 Put differently, Girkin’s public statements are useful to counterbalance those of Surkov’s people and to assess the real activities of Surkov.

Whereas the DPR was assigned to Borodai, the LPR was said to be trusted to a “Pavlov,” who later turned out to be Pavel Karpov, a member of the public chamber of Moscow and, more importantly, colleague of Borodai on the ultra-right newspaper Zavtra (Dobrov Reference Dobrov2015). The Surkov leaks contain less information on his activities in Luhansk, but at the end of 2015, the new “cabinet members” of the LPR were also recommended to Surkov with possible alternative candidates for selection.Footnote 49

Project “Novorossiya”

Despite the obvious debacle in the southeast of Ukraine in March 2014, the Kremlin continued to seek the imagined “Novorossiya” there. Putin’s reference to southeastern regions of Ukraine as Novorossiya during the televised dialogue with the nation on April 17 (President of Russia 2014a) cheered up local agents again.Footnote 50 An email Surkov’s assistant forgot to delete shows that on May 14, three days after the referenda of the DPR/LPR, which had been conducted despite the opposition expressed by Putin, Surkov and his assistant discussed the text of the “Declaration on the Establishment of the Union of People’s Republics”—Novorossiya.Footnote 51 On May 16, an Iryna Yarmak supposedly living in Kharkiv sent Surkov an Excel table of travel expenses necessary for 36 representatives of various fringe pro-Russian groups from eight eastern oblasti of Ukraine (that must be, according to the Kremlin’s narrative, part of Novorossiya) to participate in the conference to be held in Donetsk or Luhansk.Footnote 52 A few days later, the same person sent “a list (additional)” that enumerates 25 pro-Russian activists.Footnote 53 On the same day (May 19), Rapoport, the political director of the Directorate, sent Surkov a draft of “Abstracts for the Forum on May 24,” including the following talking points:

• Dialogue with Kyiv, which some international structures (OSCE) call upon …, is impossible after what happened in Odesa [fire of Trade Union House on May 2], Mariupol [clash on May 9]….

• After the adoption of the declarations of independence of the Luhansk People’s Republic and the Donetsk People’s Republic, the parliament elections should be held.

• With the decision of the parliaments, form the full-fledged governments of the DPR and the LPR.

• Following Luhansk and Donetsk, such principles should be realized in all regions—from Kharkiv to Odesa.

• We will not recognize the presidential election on May 25 and call for all potential regions of Novorossiya to join us in this protest.

• We are creating a united people’s front of Novorossiya, and we are sure that our allies in the world are the overwhelming majority.Footnote 54

On May 24, the declaration on “the unification into the Union of People’s Republics—Novorossiya” was signed by the representatives of the DPR/LPR at the Congress of People’s Representatives of the South-East of Ukraine held in Donetsk. At the same congress, Ukrainian parliamentarian Oleg Tsarev announced the creation of the socio-political association People’s Front of the southeastern regions (“Na yugo-vostoke Ukrainy sozdano dvizhenie ‘Narodnyi front’” 2014).

Moscow, however, gave a clear signal for avoiding the excessive engagement in Novorossiya, perhaps considering the huge financial burden Russia might bear (see Section “Economic Control”). On June 5, Chesnakov sent Surkov a four-page document titled “the Path of Novorossiya. Toward Victory and a Better Life,” the main points of which were that the Russian leadership is doing everything to stop the war initiated by “fascist” Kyiv against Novorossiya, but the direct annexation of Novorossiya may hamper the peace settlement process, therefore “at this tactical moment, there is no such opportunity.”Footnote 55 The following day (June 6), Rapoport arranged Surkov’s meeting with co-chairs of the People’s Front of Novorossiya, Tsarev and Konstantin Dolgov.Footnote 56

On June 10, the former Nashi leader Vasily Yakemenko visited Surkov with ex-Nashi members as well as a Ukrainian citizen.Footnote 57 The meeting agenda was not provided in the leaks, but it can be safely assumed that Novorossiya was a central topic; shortly after the meeting, one of the participants sent Surkov a project proposal called “Action to Create the Newest Historical Policy (Object—Novorossiya).”Footnote 58 The project describes one of its purposes as “formation of the newest historical policy of Russia in relation to Novorossiya.” In addition, for the visit to the premises of the Presidential Administration, access to which is under strict control,Footnote 59 Yakemenko’s secretary asked for permission for “Car Toyota O978AK150 + computer” in advance. The preparation of the computer for the meeting with Surkov reminds us of intensive cooperation between the Kremlin and Nashi ex-members to conquer domestic cyber space with social media and viral videos around 2011,Footnote 60 suggesting that such methods would be further applied with a focus on Ukraine.

Surkov occasionally used nationalists to create a myth and stage enthusiasm for Novorossiya. On June 27, Chesnakov sent to Surkov a draft article on the interview with Alexander Prokhanov, editor-in-chief of Russia’s ultra-nationalistic newspaper Zavtra. The draft titled “Novorossiya Is a Delightful and Unique State” glorifies and mythologizes Novorossiya. This interview was then edited and published on the web on July 1 with a different title: “It Is Not Time and Not Reasonable to Incorporate Novorossiya into Russia”.Footnote 61 Project Novorossiya was constantly gaining momentum in Surkov’s directorate: beginning on July 2, the daily monitoring reports on “Odesa, Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Luhansk oblasti” were renamed to the reports on “Novorossiya”. On July 14, editor-in-chief of Ekspert magazine, Valery Fadeev, facilitated a round table called “History and Culture of Novorossiya” at the Museum-Reserve “Tsaritsyno” with the assistance of the Russian Historical Society.Footnote 62 The conference was inspired by “the political discourse of the toponym Novorossiya as a designation for the union of the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk republics,” and stresses that “self-identification that dates back to the historical Novorossiya is relevant for a large part of the inhabitants of several regions of the southeast of Ukraine.” On July 28, Chesnakov sent Surkov two emails on the advertisement of Novorossiya. One is a synopsis of Moscow State University professor of philosophy Andrei Ashkerev’s book Novorossiya: Russian Utopia, which proposes “the transformation of Crimea into Russian Hong Kong, Odesa into a free city and the ‘port-franco,’ Donetsk and Luhansk—into the national feudal republics.”Footnote 63 The other is a draft article on the interview with the film director Vladimir Khotinenko titled “Events in Novorossiya Are a Test for Russia.” It argues that Novorossiya will no longer be part of Ukraine, but not necessarily a part of Russia either, because the latter will cause a negative reaction in the world, and that Russia is exercising maximum restraint toward Novorossiya.Footnote 64 Khotinenko’s article was uploaded on the Kremlin-affiliated website on August 1,Footnote 65 but the publication of Ashkerev’s book was not confirmed. The fever of Novorossiya subsided toward the end of summer.

Economic Control

As the daily reports on “Management decision/Business control” in Figure 1 shows, from June to mid-July, Surkov’s priority was to take control of local business in the Donbas. In Surkov’s directorate, economic issues of the DPR/LPR were handled by Vladimir Avdeenko, head of the department of financial and infrastructure issues, an official of the Ministry of Industry and Trade. On May 25, Petro Poroshenko, who rejected the idea of federalization of the state and insisted on continuing the antiterrorist operations in the east, won the Ukrainian presidential election. The next day, Avdeenko sent Surkov the estimation of the annual budgets of the DPR/LPR, including such expenditures as “law enforcement agencies,” “youth support,” and “expenses of the pension fund.” The annual cost to run the two “people’s republics” was estimated to reach 300 billion Russian rubles per year (approx. 8.6 billion USD).Footnote 66 Interestingly, the future expenses were inflation-indexed for the period until 2017. Although Surkov’s task was believed to return the DPR/LPR to Ukraine with political leverages kept in hands of the Kremlin (see Zygar’ Reference Zygar’2016, 355–356), he also envisioned a prolonged scenario.

A couple of hours later, Surkov was sobered by another message sent by Avdeenko. The document, titled “Summary of Revenues and Expenditures in 2013,” showed that the income of the Donetsk region in the past fiscal year was only 20.5 billion UAH (2.6 billion USD), while the expenses exceeded 46 billion UAH (5.7 billion USD). For the Luhansk region, the corresponding figures were 11.1 billion UAH (1.4 billion USD) and 23.2 billion UAH (2.9 billion USD).Footnote 67

The popular discourse “the Donbas feeds Ukraine” turned out to be wrong, forcing Surkov to seek local financial sources in order to maintain the republics. Earlier, on May 20, the DPR “parliament speaker” Denis Pushilin announced the beginning of nationalization in the region, citing as its reason the reluctance of local oligarchs to pay taxes to the DPR budget. Pushilin condemned Donetsk oligarch Rinat Akhmetov for calling for protests by the Donbas enterprises against the activities of the DPR, and stated that the DPR would not conduct further negotiations with Akhmetov.Footnote 68 After Avdeenko’s estimation, however, Surkov softened his attitude to Akhmetov and tried to co-opt him. On May 31, the DPR Prime Minister Borodai not only denied “nationalization” for the Donetsk oligarch but also flattered Akhmetov with statements such as these: “We do not talk about [Akhmetov’s enterprises’] nationalization, we have nothing to do with the communists …”;Akhmetov “is not Kolomoisky [Dnipropetrovsk oligarch and governor, who stood firmly against Russian interventions]”; and he “did a lot for the Donbas, enjoying prestige here” (RIA Novosti. May 31, 2014). This statement of Borodai’s was highlighted in Chesnakov’s first report on “Management Decisions of Ukraine and Novorossiya.”Footnote 69

Surkov enlisted support of Kremlin-loyal bankers to blackmail the Donetsk oligarch. On the same day of Avdeenko’s budget estimation for the DPR/LPR, Russian VTB Bank president Andrey Kostin reported to Surkov on “the total exposure of VTB Group on the SKM,” which shows the loan amounts with their due dates (totally 942 million USD) the VTB banks provided to the enterprises of Akhmetov’s System Capital Management group (DTEK, Metinvest, etc.).Footnote 70

On June 4, Surkov’s interest in “‘Russian’ business in the southeastern regions” was revealed in the document that lists industrial companies of Donbas and other southeastern regions, whose stocks were believed to belong to Russian billionaires such as Aleksandr Frolov, Roman Abramovich, Usman Alisher, Oleg Deripaska, and Viktor Vekselberg.Footnote 71 In the middle of June, Avdeenko sent Surkov the document titled “On the Risks of the Economic Blockade of the LPR and DPR,” which envisages alternative raw material and electricity supplies to the Donbas from Russia upon the economic blockade imposed by Ukraine.Footnote 72 Humanitarian assistance to the southeast of Ukraine, which was allegedly started in June by the Federation Council’s initiative, was also controlled by Surkov’s directorate.Footnote 73

Agenda Control and Media Manipulation

Surkov’s attention to the media coverage in Ukraine appeared as soon as he assumed the position of Presidential Aide (Hosaka Reference Hosaka2018, 347–349). After the eruption of the Euromaidan, director general of Channel One (Russia) Konstantin Ernst sent Surkov a report titled “TV Space of Ukraine”—Ukrainian TV channels magnates, domestic shares, financial status, and main target audiences,Footnote 74 and in mid-December Surkov met one of the media magnates, Victor Pinchuk of Star Light Media group.Footnote 75

The Russian political technology practices of “expert meetings” and “jeans” (paid articles) flourished during the Ukraine crisis.Footnote 76 In the middle of February 2014, between his frequent trips to Ukraine, Surkov held his first “expert meeting” to shape the information agenda on Ukraine.Footnote 77 The meeting was arranged by Chesnakov, and participants included Oleg Bondarenko, Evgeny Minchenko, and Sergey Mikheev. With the escalation of the Euromaidan, these political technologists disseminated their “expert” opinions in the media to pollute information space with the Kremlin’s favorite interpretations as well as diversionary narratives: “an active geopolitical struggle is taking place around Ukraine, involving not only Russia, the United States and European countries, but even China” (“Evropa vpervie za poslednie 25 let uvidela Rossiyu takoi, kakoi ona dolzhna byt’—sil’noi” 2014); “this is a real civil war…. Lviv radicals will organize a punitive campaign to the east in the style of Bandera actions to force eastern people live ‘correctly,’” (“Tochka nevozvrata proidena: Sergei Mikheev o situatsii na Ukraine” 2014); Maidan is “a revolution of oligarchs” (“Oligarkhicheskaya revolyutsiya: komu byl vygoden Evromaidan?” 2014). The similar meetings were held in May with the almost same members,Footnote 78 and in June, with the addition of editor-in-chief of Russkii Reporter magazine Vitaly Leybin, his colleague and editor-in-chief of Ekspert magazine Valery Fadeev (for Fadeev, see Section “Project ‘Novorossiya’”), and Alexander Kazakov (for Kazakov, see Section “Project ‘Zakharchenko’”).Footnote 79 In the latter half of 2015, the responsibility for media expert meetings on Ukraine was delegated from Chesnakov to Bondarenko, who convened such meetings with attendance of the contributors to anti-Ukrainian news sites (half of them are Ukrainian citizens) on a monthly basis.Footnote 80

In the DPR/LPR, the Kremlin’s political technologists tried to create the “media vertical” system, which goes alongside the administrative vertical of the newly created virtual “states.”Footnote 81 On June 16, the DPR “parliament speaker” Denis Pushilin, who was on a visit to Moscow to meet Surkov, Matvienko (Chairperson of the Federation Council), and Malofeev, sent Surkov an Excel file titled “estimation of the ministry, press center, newspaper” with calculations of salaries and equipment to create a “ministry of information and mass communications.”Footnote 82 The planned “ministry” would consist of, among others, “department of media regulation” and “department of formation and promotion of state ideology.” Furthermore, on June 30, Chesnakov’s staff sent Surkov a “List of Media of the DPR/LPR,” which classifies existing TV channels and newspapers in Donetsk and Luhansk into three categories based on their loyalty to the Kremlin: “ours,” “neutral/we fight for,” and “not ours.”Footnote 83

After the annexation of Crimea, the Russian state-sponsored TV channels and news agencies had finally lost trust among the Ukrainian viewers (Szotek Reference Szotek2014). In response, Moscow intensified efforts to spread its narratives through social media. On May 23, Chesnakov reported to Surkov about pro-Russian bloggers in Ukraine,Footnote 84 some of whom—Alexander Chalenko and Pavel Dulman—later became frequent visitors to the expert meetings hosted by Surkov. Surkov also started to create quasi pro-Ukrainian news sites as renewed instruments to influence the public opinion in Ukraine. In July, for this purpose, he recruited a pro-Russian political technologist from Zaporizhia, Pavel Broide, through vice president of Russian Wrestling Federation Georgy Bryusov, and developed plans for various news websites tailored to manipulate the propaganda-resistant Ukrainian audience, with their ties to the Kremlin sophisticatedly concealed (“war news site VOINA-UA,” regional information portals, “anti-war site,” “pro-European, national-democratic oriented site”).Footnote 85 However, according to Broide, the promotion of such new media outlets should be coupled with the efforts to “reorient the media that already have consistently high rates of access in the Ukrainian segment of the Internet and authority among readers.” In the middle of July, Bryusov suggested that a key to the success would largely depend on the use of influential local media resources of Ukrainian Media Holding, owned by Sergey Kurchenko, a young oligarch and Yanukovych’s closest ally, who defected to Russia after the Euromaidan.Footnote 86 Later in the month, Surkov met with Kurchenko, who was under the guardianship of an officer of the Federal Security Service of Russia (FSB).Footnote 87

On July 17, the Malaysia Airlines plane MH17 was shot down in Donetsk region, killing 298 people on board. The news swept the world with headlines suspecting the Donbas separatists as being responsible for the tragedy, requiring immediate intervention from the Kremlin. The next day, Chesnakov sent Surkov lists of over 50 Ukrainian journalists and commentators with indication of “status personalities,” “personalities of average efficiency,” and “reserve (new personalities).”Footnote 88 Another document attached to the email is titled “thematic lines on work with the political network for July 20–27, 2014”—so-called temnik, or detailed instructions to the media representatives on how to cover events in their news programs and blogs. Some of the listed topics and conspiracies were voiced by pro-Kremlin bloggers to blame Kyiv on the plane crash in the Donbas.Footnote 89

The MH17 tragedy revived international attention to the conflict in eastern Ukraine to the detriment of Moscow. A document called “Analysis of the main publications in the English-language press devoted to ‘People’s Republics’ from July 18 to 26,” which was prepared by Chesnakov’s young analyst Anton Grishanov for Surkov, noted that after the temporary fall of the media attention against the backdrop of events in the Middle East, the Ukraine conflict returned as “one of the dominant topics in the English-language media.”Footnote 90 The analysis states that “in the DPR the most interesting figures are Russians—A. Borodai, who gave a number of significant interviews, and, to a lesser extent, I. Strelkov (Girkin),” whereas “the indigenous inhabitants of the Donbas, participating in the conflict (P. Gubarev, A. Purgin, D. Pushilin), often do not draw the interest of authors and interviewers.” It is then recommended to “establish stable channels of communication with Western journalists working in the region and form an informal media pool with permanent access to key militia figures,” as well as “involve speakers of Donbas natives” with a view to “reducing the damage from attacks by the Ukrainian authorities and the press supportive of them” and “starting the process of communicating alternative views to the general public.”

Project “Donbas” and Invasion

In the beginning of August, Russian citizens Borodai and Girkin were called back to Moscow, handing over their roles to Donetsk-born Zakharchenko, who had been regarded a possible candidate for “prime minister” in May. This reshuffle completed the indigenization process, though only superficial, of the DPR. Meanwhile, on August 7, Chesnakov sent Surkov an analysis paper on Ukrainian political parties, through which Surkov must have become acquainted with a prediction that there was little chance for any parties with pro-Russian rhetoric, including remnants of the Party of Regions and the Communist Party, to overcome the 5 percent barrier to gain representation in the upcoming parliamentary election.Footnote 91 For the Kremlin, that would mean the continued loss of its political leverage with Ukraine.Footnote 92 Surkov needed to “clap” again and launched a new political project to restrain Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations. A document Surkov received on August 18 explained the historical process of changing administrative boundaries of Donbas in the 20th century, starting from Donetsk-Krivoi Rog Soviet Republic of 1918.Footnote 93 This implies a shift of Surkov’s interest from the flawed Novorossiya to the new Donbas project.

The political boundaries of the imagined Donbas were further enforced by Russian military forces. In June and July, the Ukrainian antiterrorist operations restored control of Slovyansk and Kramatorsk, cities taken earlier by the DPR, and the insurgents retreated to Donetsk city. The Russian full-fledged invasion started on the week of Ukraine’s Independence Day (August 24), and the dissolution of the Parliament for early elections (August 25). Amid these tensions, on August 25, a draft statement titled “Immediately Stop the War! Appeal of the Peaceful Inhabitants of Donbas to the Ukrainian Public” was sent by Govorun to Surkov for his consideration.Footnote 94 The text, initially drafted by Leybin on August 21, accused the Ukrainian army of destruction and civilian victims, and required Kyiv to halt the antiterrorist operations in the Donbas. On September 2, almost the same text in a form of the NGO appeal was published in Leybin’s magazine Russkii Reporter, and it was cited not only by the Russian media outlets but also by some Ukrainian news sites controlled by a Ukrainian oligarch in exile, Kurchenko (“Nemedlenno ostanovit’ voinu! Obrashchenie obshchestvennoi organizatsii Grazhdanskaya initsiativa Donbassa” 2014). Comparison between the early draft and the published article makes it clear that they deleted text that reads “some of us [peaceful inhabitants of Donbas] voted in the referendum on May 11, others did not; some support the leaders of the DPR and LPR and others oppose to it.” The new version also removed the phrases that imply the “unity of Ukraine” inclusive of the DPR/LPRFootnote 95—a scenario Moscow preferred in case of Kyiv’s concessions. This suggests a dramatic change of Surkov’s script on the DPR/LPR at the end of August; Moscow abandoned, though temporarily, the scenario of pushing the DPR/LPR back to Kyiv, and began to pose its puppets as representatives of the imagined “Donbas” that desperately wants to secede from Ukraine. The invasion thus marked the end of Moscow’s ambiguous policy toward eastern Ukraine.

Project “Zakharchenko”

Beginning in September 2014, Alexander Kazakov, known as the Russian language advocate close to Dmitry Rogozin, functioned as director of the Center for Strategic Planning under the “Parliament of Novorossiya”. In October that year, he uploaded to his social media account a picture taken in Luhansk with the Russian best-selling writer Zakhar Prilepin.Footnote 96 A year later, on September 11, 2015, he asked for a meeting with Surkov to discuss “some of the fundamentally important parameters” of the project “na zemle [on the ground]” including “the virtual space.”Footnote 97 A week later he wrote to Surkov, “Zakhar Prilepin agreed. In a week we’ll begin to compile a synopsis of the book. A working title: ‘Two Zakhars: Dialogues about the past, present and future,’”Footnote 98 to which Surkov shortly replied, “Excellent. Thanks. Keep in touch.”Footnote 99 On November 17, Kazakov visited Surkov together with Prilepin. He reported the repeated blockings of the DPR leader’s Facebook account, and discussed Prilepin’s upcoming book to create a new myth of “our Donbas leader” Zakharchenko.Footnote 100 The book, titled All That Must Be Resolved … Chronicle of the Ongoing War, was presented at a press conference in June 2016 and hit the shelves of bookstores in Russia and the occupied Donbas.

On November 25, 2015, Kazakov wrote to Surkov, “I think this is an indirect assessment of the beginning of my job on the image))) [sic] If I had the opportunity—I myself would order a couple of such articles in the mainstream media in the West,” with the link to Alexander J. Motyl’s article “When Ukraine Lost Donetsk: The World According to Alexander Zakharchenko,” which was published in Foreign Affairs on November 22 (Motyl Reference Motyl2015).Footnote 101 Citing Zakharchenko’s statements published on a Russian propaganda website, the article argues that peace in eastern Ukraine depends not only on Vladimir Putin but also on the DPR leader. Motyl further contends that “Zakharchenko’s fanaticism” might worry Moscow, taking at face value his statement: “‘the fate of the Donbas’ is decided in the Donbas, not in Moscow, Washington, Berlin, or Paris”; and “I [Zakharchenko] personally do not intend to be a puppet in anyone’s hands.” As Kazakov bragged, this is a successful case of Surkov’s manipulation on the artificially created image of Donbas leader Zakharchenko, which reached a broad international audience, including policy makers, via one of the world’s most influential magazines.

In the beginning of 2016, Kazakov repeatedly asked Surkov to spare him time for an urgent meeting to “discuss the tasks in new circumstances, including political ones,”Footnote 102 as well as “new information received from Zakhar Prilepin.”Footnote 103 Surkov, however, remained lukewarm to these requests, which apparently embarrassed Kazakov, who described this as “unpaid leave.”Footnote 104 On March 16, Kazakov asked Surkov’s secretary to remind her boss of his request for the meeting, adding, “On Friday, March 11, A.Z. [Alexander Zakharchenko] told me that I should meet VYU [Surkov] to receive new instructions on the job in the territory [the DPR].”Footnote 105 Surkov’s low-key attitude to the Donbas exhibited in the correspondence might be connected to the temporary decrease of the Kremlin’s disinformation activities regarding Ukraine during the Syrian campaign period (NATO StratCom COE 2016, 11–12). Nevertheless, Kazakov continued his job as liaison between Surkov and two “Zakhars,” and Prilepin assumed the position of deputy commander of the DPR battalion in October 2016 (“Zakhar Prilepin stal zamestitelem komandira batal’ona DNR” 2017).

Conclusions

What Ensures the Kremlin’s Plausible Deniability?

Suslov argues that the DPR and LPR leaderships switched their focus from Novorossiya to Donbas, and that this refocus became particularly evident after the Minsk agreements, “when the two self-declared peoples’ republics had stabilized their borderline with Ukraine” (Suslov Reference Suslov2017, 208). But the leaks suggest an opposite causal relationship: the Donbas project was first designed by the Kremlin in August 2014 upon the failure of Novorossiya, and then its borderline was fixed by military force of the Russian army.

Surkov is an excellent dramaturg; he writes scripts, casts actors, analyzes their performances and narratives, runs promotions, and puts the repertoire into motion to achieve the intended reactions of the target audience (foreign governments, politicians, diplomats, journalists, researchers, and the public). His task was to compromise the Ukrainian government and to disguise the Russian aggression of Ukraine as “a civil war.” Most of his efforts are directed toward manipulating public opinion, and the methods and resources employed against Ukraine have much in common with the domestic political technology that utilizes pseudo-experts, technical parties, fake civic organizations and youth movements such as Nashi, and covert media techniques. As Wilson notes, the hybrid war in Ukraine is “the latest bastard offshoot of political technology, with the same ultra-cynical and often self-defeating methodology” (2014, 192). The fact that Surkov’s team was staffed with his former colleagues and experts specialized in domestic politics, or simply political technology, confirms that the Russian policy toward Ukraine is an extension of its “virtual” domestic politics, but not traditional diplomacy at all. For example, Surkov’s attempt to pose Zakharchenko as an independent leader reminds us of the concept of “tribune of the people,” an opposition leader who is covertly financed by the regime and actually has no intention of challenging it (Wilson Reference Wilson2005, 187).

Multiple actors and gadgets are at Surkov’s disposal, and he pulls each string resourcefully depending on the circumstances. In hybrid warfare, Russia mobilizes not only politicians, bureaucrats, and regular/irregular army troops, but also scholars, journalists, politologs (Russian political experts), priests, philanthropists, bankers, lawyers, writers, singers, athletes, bikers, youth, and other human resources available to the totalitarian regime. The list of Surkov’s actors includes Ukrainians in exileFootnote 106 as well as Ukrainian parliamentarians in Kyiv.Footnote 107 Their roles are flexible, temporary, and project-based (“curator” system), and some actors are engaged in projects outside their professional scope (for example, Bryusov from the Russian Wrestling Federation). Some enthusiastic political technologists behave autonomously and proactively, believing that supply creates its own demand (Wilson Reference Wilson2005, 61–62), but never cross a red line and harmonize their individual and operational goals with tactics and strategy of the upper curators (see, for example, Frolov’s interactions with his curators on “people’s referendum” in Mykolaiv and “unconstitutionality” issue). Perhaps, the vertical power structure allows the Kremlin to be the sole client for all political technologists.

According to Gleb Pavlovsky, “traditionally separate roles—businessman and politician, lobbyist and politician—don’t really apply in Russia.” The financial resource for projects can therefore be provided by various actors other than the government.Footnote 108 But in the Russian kleptocracy system, the ultimate sponsor is always the State; “philanthropists,” such as Malofeev, who in fact has a proven track record for the Kremlin, support allegedly nongovernmental initiatives with funds embezzled from the State.Footnote 109 Unofficial resources provided by oligarchs are attractive for the Kremlin because such a scheme serves as a smokescreen for state-sponsored, often unlawful, operations, ensuring plausible deniability in international conflicts in which Russia is covertly involved.

Probably no one except Surkov sees the entire picture of the influence operations deployed in Ukraine, and there are duplications of tasks either within his own work or with the activities of other agencies. For example, in November 2015, Alexander Kazakov requested a clarification from Surkov as to why his colleagues received a task that intersects with his own job.Footnote 110 Similarly, in June 2015, Russian Duma Deputy and Surkov’s close friend Mikhail Markelov reported to Surkov a possible duplication of destabilization tasks in Kharkiv.Footnote 111 Furthermore, Borodai’s sudden departure from the Donbas and Kazakov’s “unpaid leave” suggest that Surkov uses his agents occasionally, giving each of them a respite depending on the dynamics of international and domestic media attention to Ukraine.

Artificially Created “Separatism” in the Donbas

It is widely known that the pro-Kremlin youth movement Nashi was a political project created by Surkov, who was then in charge of domestic politics in the presidential administration. Surkov’s ally and an experienced political technologist, Sergey Markov, clearly predicted the usefulness of this youth movement in Russian “near abroad” in 2007:

You know that the Nashi movement was created to oppose the Orange Revolution, and that I am a teacher for this Nashi movement. I tell them: “I am a big supporter of the Orange Revolution. But the Orange Revolution is not what Americans should make in Ukraine, but what we should make!” And it’s a storm of applause every time!

(Wilson Reference Wilson2014, 35)In this context, the fact that the pioneers of the 2014 “separatism” in the southeast of Ukraine were trained by the Nashi commissary Goloskokov at the Kremlin’s youth camp as far back as 2009 suggests that Moscow incubated possible interventions to Ukraine to thwart what they believe to be color revolutions plotted by American instructors.

But this did not necessarily mean that Moscow had been truly devoted to pro-Russian separatist agendas. In May 2015, Leybin sent Surkov’s secretary a text titled “Donbas Wins,” which, he wrote, had been “discussed with VYu[Surkov].” The piece argued that in case of Kyiv’s resumption of active military actions, both “republics” would be recognized at least by Russia, in other words, “the Russian Federation will not abandon them.”Footnote 112 The identical article was published in Ekspert magazine ten days later. Comparing it with a similar article sent by Chesnakov to Surkov a year before—“the Path of Novorossiya. Toward Victory and a Better Life” (see Section “Project ‘Novorossiya’”)—suggests that Moscow has been just toying with these pseudo-historical projects, and that it does not actually matter to the Kremlin whether it is about Novorossiya, Donbas, or whatever else; it is never too late for political technologists to give substance to any virtual entities. Another fresh example is the project “Malorossiya” [Little Russia] Surkov attempted to stage through Zakharchenko and Kazakov in summer 2017 (“Surkov:‘khaip’ vokrug Malorossii polezen” 2017). The Kremlin has no serious intention to promote the agenda of Russian nationalists in Ukraine, but just tactically promoted Novorossiya—later the circumstances forced Surkov to replace it with Donbas—to give false credibility to “separatists” who would block any attempts of Ukraine’s westward drift in its stead, creating an illusion in the domestic and international audience that they are not puppets of Moscow but desperately fighting against Kyiv junta for their localized identity, and Russia is just there to offer a helping hand.

Acknowledgments.

The author expresses a sincere gratitude to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Disclosure.

Author has nothing to disclose.