Introduction

Considerable academic interest is devoted to investigating the transformation of post-communist societies into competitive and representative democracies. The democratic survival (Svolik Reference Svolik2008, 153) of the post-communist area is becoming increasingly dubious, thus inspiring a growing body of research on de-democratization (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2018, 1481), democratic backsliding (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016), setbacks (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2015), and the rise of defective democracies (Merkel Reference Merkel2004). Academic debates seek to identify factors that enhance or restrict democratic consolidation, a concept understood as the ability to secure democracy “against authoritarian regression” (Schedler Reference Schedler1998, 103), while other authors emphasize “behavioral and attitudinal foundations of democracy” (Plasser, Ulram, and Waldrauch Reference Plasser, Ulram and Waldrauch2016, 8) that contribute to regime legitimation (Lovell Reference Lovell2017).

The introduction of a multiparty system has brought the concept of representation to newly formed democracies (Alonso, Keane, Merkel and Reference Alonso, Keane and Merkel2011; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2007), where it is vital to observe “government replaceability” (Komar and Živković Reference Komar and Živković2016, 785) as one of democracies’ central characteristics. Yet, despite adopting political pluralism, some post-communist countries have not experienced the basics of representative democracy, namely, competitiveness (Sartori Reference Sartori2005) and regular overturn of power.Footnote 1 The question is this: Why today, decades after the collapse of communism, do some countries still struggle to achieve competitiveness, while others succeed in a competitive democratic organization?

I analyze this question with the case of Montenegro, the only post-communist country in Southeast Europe that has not experienced any democratic overturn of power since the collapse of communism (Morrison Reference Morrison2009b; Vuković Reference Vuković2015). With almost three decades of uninterrupted domination by the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), this country exemplifies a “predominant party system” (Sartori Reference Sartori2005, 171), where the same party has controlled “national government without interruption since the 1990s” (Komar Reference Komar2019, 64), winning every election since the regime transformation, either alone or as the most potent party in a coalition government (Živković Reference Živković2017, 6). This is the most peculiar characteristic of the Montenegrin predominant party system; it lacks “ex-ante uncertainty” (Przeworski Reference Przeworski, Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub and Limongi2000, 16), or the possibility that the electoral outcome will be unknown in advance.

Various scholars have examined ex-ante uncertainty and identified conditions that prevent regular democratic overturn in post-communist societies, such as dysfunctional institutions and underdeveloped civil liberties (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002, 56), ineffective party organization and political opposition (Kopecký and Spirova Reference Kopecký and Spirova2008; Catón Reference Catón2007; Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002), or the “weakening and insufficient power” (Bieber Reference Bieber2018, 337) of external actors – predominantly the EU, which led to “the promise of competitive authoritarian stability” (Bieber Reference Bieber2018, 349). This article does not question these approaches and their undebatable contributions, but instead focuses on mechanisms of internal societal control that are often neglected in post-communist democratization literature. It argues for authoritarian submission—a psychological construct that presents uncritical obedience to political authority (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996)—as an important precondition for the democratic performance of post-communist societies. That is, the dependent relationship between leaders and followers is detrimental for democracy (Passini Reference Passini2017; McAllister Reference McAllister, Dalton and Klingemann2007; Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser Reference Padilla, Hogan and Kaiser2007) and actively changes contemporary political dynamics (Grundholm Reference Grundholm2020, 16). Individuals are not “merely passive vessels of whatever beliefs and opinions they have” (Jost Reference Jost2017, 167); instead, their psychological characteristics resonate with the political decisions that have profound consequences for democracy. Submissive individuals thus make political choices from a subordinate position, a mechanism that prevents democratic political organization. Democracy relies on a twofold relation between citizens and representatives, to which it is central that the “rulers know they will be held to account” (Schmitter Reference Schmitter2015, 36).

Building upon evolutionary modernization theory (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017), this article argues that submissive tendencies, although originating in authoritarian upbringing, are dominantly reinforced in a conducive environment, where unstable socioeconomic factors serve as leading causes of authoritarian behavior and firm adherence to leaders (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017). The study demonstrates how economic factors and ethnic cleavages, in the context of Montenegro, only reproduce submissive behavior, originally acquired through authoritarian parental upbringing. This developed submission consequently contributes to the lack of competitiveness in Montenegrin politics. The article, therefore, exposes the formation of submissive habits and examines their potential to affect voting for the predominant DPS.

The argument about the relevance of authoritarian submission to post-communist democratization analysis has the following theoretical and methodological implications. First, authoritarian submission is an understudied, but extremely important factor for post-communist societies accustomed to strong leadership. This particular dimension of authoritarianism reveals the nature of individual relation to political authority that is established within a particular society (Harms et al. Reference Harms, Wood, Landay, Lester and Lester2018). Democratic success does not depend solely on political transition—without the transition in consciousness among the citizenry (Ethier Reference Ethier2016), obedience is still valued as a proper behavioral response to political authority, and democracy is harder to achieve.

Second, the distinct effects of authoritarian submission are absent from the traditional unidimensional concept of authoritarianism.Footnote 2 Namely, an authoritarian mindset is a set of enduring personal characteristics that make an individual (1) rigid and conventional in their beliefs and values (conventionalism); (2) submissive to people with superior status (authoritarian submission); and (3) aggressive and oppressive to individuals perceived as inferior (authoritarian aggression) (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950; Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996). Instead of a classic unidimensional approach, this study relies on Passini’s (Reference Passini2017) novel three-dimensional model of authoritarianism that conceptualizes authoritarian submission, aggression, and conventionalism as three separate dimensions. Treating authoritarianism as a unidimensional syndrome masks the different influences that each dimension may have. The tripartite approach enables the proper assessment of authoritarian submission compared to the other dimensions of authoritarianism. This article presents the first application of Passini’s (Reference Passini2017) three-dimensional authoritarianism model on party preferences and measures the impact of each dimension, both separately and jointly, using survey data from the Montenegrin National Elections Study (2016) and a self-designed student survey (see appendix 2).

Third, the study takes the case of Montenegro as the only Southeast European country that has not changed the major structure of its leadership since regime change (Morrison Reference Morrison2009b): the DPS and its leader, Milo Đukanović, remained at the center of the system. Moreover, Montenegro is especially suited for studying submissive mindsets—75% of Montenegrin citizens consider a strong leader, unconcerned with parliaments and elections, as a very good or fairly good political solution (Gedeshi et al. Reference Gedeshi, Kritzinger, Poghosyan, Rotman, Pachulia, Fotev and Kolenović-Đapo2020), while comparative data includes this country in the top 25% of most submissive societies (Komar Reference Komar2013, 156–157; see table 1).

Table 1. Authoritarian Submission across States

Source: Komar (Reference Komar2013, 155–157). Note: The countries listed in the table were included in the European Values Study - 2008 (Komar Reference Komar2013, 155–157). Authoritarian submission indicators measured the preference for strong leadership and military rule, and obedience as the child’s most important virtue (Komar Reference Komar2013, 155).

The majority of countries in table 1 belong to the post-communist area with interrelated contextual conditions. None can be labeled a functional liberal democracy, compared to Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland, which are some of the least submissive societies (Komar Reference Komar2013, 156) and which belong in the top 10% of most democratic regimes (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Maerz, Grahn, Alizada, Gastaldi, Hellmeier, Hindle and Lindberg2020, 24). Furthermore, Romania, the only EU country in the table, currently ranks as a case with “significant or substantial autocratization” (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Maerz, Grahn, Alizada, Gastaldi, Hellmeier, Hindle and Lindberg2020, 24). Table 1 demonstrates the prevalence of submissive traits among nondemocratic societies or dysfunctional democracies, thus indicating the necessity for a more profound analysis of the relationship between personality types and political outcomes.

Finally, this article is structured as follows: the first section conceptualizes authoritarian submission through a multidimensional approach to authoritarianism and exposes different developmental stages of submissive habits, namely, authoritarian upbringing and conducive environment. The second section focuses on the applicability of the concept of submission to the Montenegrin case, while the third section examines the influence of this authoritarianism dimension on voting preferences with two surveys, the Montenegrin National Elections Study (MNES 2016) and a self-designed survey of Montenegrin students (see appendix 2). In the last section, I summarize the results and discuss the implications of this research.

Authoritarian Submission: Exposing the Concept

Authoritarian submission is defined as “a high degree of submission to the authorities who are perceived to be established and legitimate in the society in which one lives” (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996, 7). The impact of authoritarian submission was often neglected in the traditional and unidimensional understanding of the authoritarian personality structure (APS), based on Adorno et al. (Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950). Adorno and colleagues constructed the well-known F-scale (fascism scale), with 39 items measuring authoritarianism as a “single syndrome [or] […] enduring structure in the person” (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950, 228; italics added) that would explain attachment to antidemocratic tendencies. The F-scale contains nine components of APS, from sexual deviation to authoritarian aggression (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950, 228). The unidimensional authoritarianism model in Adorno et al. (Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950) does not address the difference between distinct components, thus disabling the investigation of separate influence that authoritarian submission may have.

Bob Altemeyer (Reference Altemeyer1996) revised the traditional approach to APS with the study of right-wing authoritarianism (RWA). He reduced the nine components of APS to three: conventionalism, authoritarian submission, and authoritarian aggression. Altemeyer’s model made the Adorno et al. version of authoritarianism more applicable to substantive research questions. However, Altemeyer’s scale was still criticized as measuring the three components through a unidimensional approach, all of which fall under the umbrella of authoritarianism (Passini Reference Passini2017). Critics argued there is a grounded risk that analyzing conventionalism, authoritarian aggression, and authoritarian submission, all together, erases their differences (Funke Reference Funke2005). This created an urge for a novel, three-dimensional approach to authoritarianism that treats authoritarian submission, conventionalism, and authoritarian aggression as three distinct structures. Passini recognized that the distinctiveness between the three dimensions would become masked by “the global authoritarianism score” (Passini Reference Passini2008, 57) with the unidimensional approach. Namely, while conventionalism and authoritarian aggression are more applicable to conservative ideological identification (Dunwoody and Funke Reference Dunwoody and Funke2016), authoritarian submission measures relation to authority without ideological constraints. This actually means that individuals who are obedient and submissive to authority are not necessarily conservative or rightist in their worldviews (Passini Reference Passini2017). Authoritarian submission is able to recognize those voters that are not aggressive; however, they are equally destructive for democracy (Passini Reference Passini2017, 83). Submissive individuals are preoccupied with their role of compliant followers and infatuated with the authority they obey.

Moreover, individuals falling into this category do not readily accept change; instead, they are resistant to it (Jost Reference Jost2015). Submissive minds are used to thinking in narrow categories, and requiring them to let go of their attachment to authority would be a demanding and slow process (Bridges and Mitchell Reference Bridges and Mitchell2000, 31). Submissive voters are unidentifiable with the analysis of the joint effects of authoritarianism dimensions, which warrants treating these dimensions separately.

The Formation of Submissive Habits

An equally important line of discussion examines the origins of authoritarian submission, which typically begin with the upbringing process. Accordingly, parents are the first authoritative figures that affect a child’s general perceptions about preferable values and beliefs, as well as dominance and subordination, in later stages of his/her life. Individuals who experience authoritarian behavior from their parents are more prone to authoritarian personal characteristics that further shape their “social and personal behavior both toward those with power and those without it” (Frenkel-Brunswik in Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950, 350). Authoritarian parents believe that obedience and respect to authority “are important virtues that children should be taught, and if children stray from these principles, parents have a duty to get them back in line” (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996, 9). Individuals subjected to obedience and authority in the upbringing process are more likely to develop the same behavioral pattern in the political world. However, upbringing is not the only factor that matters in the development of authoritarian submission, since the influence of authoritarian parenting might diminish when an individual is socialized in a progressive surrounding. In line with evolutionary modernization theory (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017), I argue for the importance of an additional element called conducive environment (Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser Reference Padilla, Hogan and Kaiser2007, 185). That is, evolutionary modernization theory claims that individuals have “relatively high or low levels of authoritarianism, in so far as they have been raised under low or high levels of existential security” (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017, 137). Unstable socioeconomic environments create an “authoritarian reflex” (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017, 137), a self-defense strategy of obedience to political authority. Individuals living in a state of socioeconomic insecurity trust the established authorities “even if abuse of this trust occasionally occurs” (Miller, Collins, and Brief Reference Miller, Collins and Brief1995, 8), and they are convinced that the strong authority presents the best political solution—the only one truly capable of bringing decisions about political future. Figure 1 shows these different developmental phases of authoritarian submission:

Figure 1. Development of the Authoritarian SubmissionFootnote 3

Authoritarian upbringing is the first stage, but the conducive environment presents a crucial mediating factor, which increases the likelihood of submissive behavior to those with political power. The conducive environment serves as a state of prolonged socioeconomic anxiety, which transforms obedience as a value into obedience as action. I argue for economic and ethnic conditions as influential factors in creating a conducive environment or an “existential security” (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017, 137), as a situation where the virtues of obedience and respect to authority, taught in the upbringing process, become applicable. On the one hand, economic underdevelopment makes people insecure about their basic needs and, consequently, unable to evaluate the political authority properly. Ethnic belonging, on the other hand, presents a very significant line of identification, with increasing political salience in post-communist societies that experienced identity-based turmoil (Wylegała Reference Wylegała2017; Džankić Reference Džankić2014; Harris Reference Harris2012). Namely, ethnicity is a societal dimension derived from the historical legacy. Once it is transformed into party cleavage, this societal dimension stays “‘frozen’ over extended periods of time, even though the underlying societal conflicts may subside” (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1995, 448; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Economic and ethnic disturbances, thus, present long-term contextual factors that only enhance submissive tendencies, which, consequently, contribute to the endurance of pre-dominant systems. The conducive environment reinforces authoritarian submission, initially taught in the upbringing process, and strong leadership then becomes a long-term urge for obedient individuals that seek security and direction. Submissive individuals, thus, demonstrate a preference for the firm and uninterrupted leadership, as suggested in the general hypothesis for this research: more submissive societies will show more preference for strong leadership and no change of the incumbent government.

The Case of Montenegro

The suitability of the Montenegrin case for analyzing authoritarian submission begins with the upbringing process. First, an extensive United Nations Children’s Fund study (UNICEF 2013) revealed that 40% of Montenegrin citizens think of the traditional and rigid model of upbringing as the best option of raising a child.Footnote 4 New data demonstrates an increasing tendency: more than 63% of Montenegrins agree with obedience and respect to authority as the most important virtues children should learn (MNES 2016). Moreover, UNICEF reported that four out of ten Montenegrin children personally experienced violent discipline, where 45% of them encountered physical punishment (UNICEF 2013). From a comparative perspective, Montenegro fits well into the general Southeast European preference for strict upbringing (Albania, 61%; Macedonia, 52%; Bosnia and Herzegovina, 40%; Serbia, 37%) (UNICEF 2014, 2).

Interestingly enough, a later UNICEF study (2017) found a lesser percentage of Montenegrin citizens who disagree with the physical punishment having a negative effect on their upbringing (25% in 2016; 31% in 2013; see UNICEF 2017, 2013), while the level of agreement with the physical penalty as a positive upbringing measure remained unchanged (47% in 2016; 47% in 2013; see UNICEF 2017, 2013). Furthermore, these respondents have dominantly applied the same pattern in their families (UNICEF 2017), which indicates that the traditional punishing educational models persist in this country. As table 2 shows, Montenegrin respondents still score highly (3.09 out of 5) on the measure of the authoritarian perception of the upbringing process: “Today’s society is immoral partly since both teachers and parents forgot that physical punishment is still the best way of upbringing” (MNES 2016).

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics: Authoritarian Perception of the Upbringing Process in Montenegro

Source: MNES (2016).

The role of strict upbringing is also present in the political context. More than 60% of young Montenegrins (16–28) argue about parents’ political attitudes as resonating with their own (WFD 2020, 17), while 31% of them think it is not fine or normal to have different political views from parents (WFD 2020, 17). The family also presents one of the most influential factors in deciding for whom to vote (MNES 2016).

The preference for an authoritarian upbringing presents the first stage; however, I claim that the submission of Montenegrin citizens dominantly stems from a conducive environment, a complex interaction between several socioeconomic situational factors, which makes obedience the enduring behavioral pattern to personalized rule. In line with the evolutionary modernization theory argument, widespread socioeconomic insecurity and distress make citizens seek a strong state authority that will resolve all of their problems. The economic continuum of the DPS, together with the clear ethnic detachment from Milošević’s politics in 1997 (Džankić and Keil Reference Džankić and Keil2017, 407), portrayed the party and its ruler, Milo Đukanović, as a Montenegrin savior (Džankić and Keil Reference Džankić and Keil2017, 410) or “pragmatic reformer” (Bieber Reference Bieber2018, 342).

Economic crisis, manifesting after the turbulent Yugoslav separation, transformed into a “very deep and very prolonged recession” (Popović Reference Popović, Drašković, Minović and Hanić2018, 316) blocking the industrial output (Đurić Reference Đurić and Bieber2003, 141). Montenegrin GDP per capita reached its lowest point (40%) in 1993, with an inability for significant economic growth for more than a decade (Popović Reference Popović, Drašković, Minović and Hanić2018, 315-316). The DPS, as a successor of the Montenegrin League of Communists, had enviable continuity in access to economic resources, which evolved in a crisis setting. After the breakdown of Yugoslavia, the party controlled the Montenegrin economy together with the black market, which provided incentives otherwise impossible to receive while the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was under sanctions (Džankić and Keil Reference Džankić and Keil2017, 408). Đukanović’s counterparts labeled him a “magician” (Morrison Reference Morrison2009a, 33), referring to his achievements during the recession period since the DPS managed to become the leading employer (Vuković Reference Vuković2014), despite the economic collapse, and develop “strong patronage and clientelistic networks” (Džankić and Keil Reference Džankić and Keil2017, 408). Đukanović himself admitted, “I have no doubt that we had a serious advantage over our political competitors” (Vuković Reference Vuković2015, 77).

Moderate levels of economic development, combined with established clientelism, enabled the citizen-authority dependency—one significant step closer to authoritarian submission. Montenegro belongs to one-third of the EuropeanFootnote 5 countries with the highest poverty risk rate (above 20%) between 2013 and 2017 (MONSTAT 2018, 45–50). The unemployment rate is still considered high, with an average of 17.27% between 2010 and 2018 (European Commission 2019, 44), while public debt reached the record of 70% (European Commission 2019, 44). Clientelism still presents a functional political medium (Džankić and Keil Reference Džankić and Keil2017); DPS voters dominantly agree with the idea of having a job as a legit result of supporting this party (Komar Reference Komar2013, 187), while more than 46% of young people anticipate employment as an outcome of party membership (WFD 2020, 18).

Another important contextual element is the ethnic dimension—which is highly ranked in the DPS agenda—and it transformed into a persisting characteristic of contemporary Montenegrin party politics, where declaring yourself as Montenegrin or Serb presents a precondition for political identity (Stankov Reference Stankov2016). Namely, unlike other Yugoslav republics, Montenegro had an ethnic trajectory that did not coincide with Yugoslav separation. 1997 saw the split in the DPS (Bieber Reference Bieber2003, 11) when Đukanović became explicitly associated with Montenegrin independence and identity, while the competing branch—the Socialist People’s Party of Montenegro (Socijalistička narodna partija Crne Gore; SNP)—emphasized the Serbian ancestry of Montenegrin citizens and unification with Serbia (Džankić Reference Džankić2014, 45). The ethnic question and the sensitivity of Montenegrin nationhood date back to 1918 when Montenegro was violently incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Pavlović Reference Pavlović1999, 157). The country finally gained back its independence during the referenda in 2006 (Darmanović Reference Darmanović2007), with the pro-independent stream led by Đukanović’s DPS and several minority parties, while the second block was pro-unionist, dominantly supported by the SNP (Džankić Reference Džankić2015).

The ethnic dimension was opened again when the DPS initiated the question of the Montenegrin Orthodox Church, which lost its autocephalous status with the annexation to the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1920, two years after Montenegro was merged to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Venice Commission 2019). The Montenegrin parliament recently adopted the Law on Freedom of Religion or Beliefs and Legal Status of Religious Communities that requires registration of all religious buildings and lands that belonged to the state of Montenegro before 1918, including those from the Serbian Orthodox Church.Footnote 6 The protest rallies, as a reaction to the new law, were, in Đukanović’s words, intended to “question Montenegrin independence” (Vasović Reference Vasović2020).

The two (economic and ethnic) factors created a beneficial context for the atypical longevity of the DPS. They transformed obedience as a parental value into obedience as a logical behavior to political authority. The conducive environment helped Đukanović emerge as a potent politician that was able to survive all waves of changes in Montenegrin politics while nurturing a cult of strong and charismatic leadership.Footnote 7 The 29-year domination of this party would be highly debatable without Đukanović’s personalized leadership that “greatly contributed to the rule of DPS in Montenegro” (Džankić and Keil Reference Džankić and Keil2017, 413). There is no European country dominated by the same individual for so long, “not Putin, not Lukashenko, not even Bavaria” (Bieber Reference Bieber2018). The repeated domination of one person demonstrates the tendency within post-communist societies to be resistant to change (recall that this is an important implication of authoritarian submission)Footnote 8 and support a strong leader that will provide them with a sense of clarity and direction (Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser Reference Padilla, Hogan and Kaiser2007).

Consequently, citizens’ preference for paternalistic and authoritarian leadership sustains. Every second Montenegrin respondent agreed with the statement “without a leader, every nation is like a man without a head” (Krivokapić Reference Krivokapić2014, quoted in Krivokapić and Ćeranić Reference Krivokapić and Ćeranić2014, 207). One-third of Montenegrin citizens think that “having a strong leader in government is beneficial for Montenegro, even if the leader bypasses the rules to do the job successfully” (MNES 2016). Further, 42% of young Montenegrins support authoritarian and paternalistic rule, and qualitative research reveals a leader’s charisma as a decisive factor for joining the political party (WFD 2020, 11).

The follower-leader dependency has substantive consequences for the democratic capacity of a post-communist state. Table 3 shows a limited percentage of so-called strong democrats in Montenegro that support democratic political organization and resist the leader’s unlimited authority as a preferable rule.

Table 3. Democratic Political Culture Index

Source: Klingemann, Fuchs, and Zielonka (Reference Klingemann, Fuchs and Zielonka2006, 5) and Komar (Reference Komar2013, 115–116). Note: Four indicators were used for the democratic political culture index: (1) democracy may have problems, but it is better than any other form of government; (2) preference for having a powerful leader in government who bypasses the parliament and elections; (3) preference for military rule; (4) preference for democratic rule (Komar Reference Komar2013, 115).

The Montenegrin case bears resemblance with Belarus, Ukraine, and Bulgaria as post-communist countries whose political culture did not follow the system transformation (Komar Reference Komar2013, 116). New data demonstrates that Montenegro scores below 4.93 (on a scale of 1–10) Eastern European average in political culture, a measure that involves perceptions of leadership (Economist Intelligence Unit Reference Unit2019, 30).Footnote 9 When compared with the former Yugoslav region, Montenegro ranks fourth, behind Slovenia, Croatia, and Serbia (see table 4).

Table 4. Political Culture Index in Former Yugoslav Countries

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (Reference Unit2019, 30).

The analysis recognizes “‘strongmen’ who bypass political institutions” as one of the leading causes for underdeveloped political culture and the “democratic malaise” in Eastern Europe (Economist Intelligence Unit Reference Unit2019, 53).

I have argued here that the submissive habits of Montenegrin citizens originate in authoritarian upbringing, but these are reinforced in a prolonged conducive environment where citizens amid economic and ethnic disturbances formed a habit of continuous reliance on strong authority as a panacea. This research, thus, introduces authoritarian submission as an important addition to the current study of the democratic pace in post-communist societies, which I test as a substantial factor for understanding the Montenegrin predominant party system through the following hypotheses: (1) authoritarian submission will have a positive effect on voting for the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), compared to voting for other parties; and (2) authoritarian submission will present the best predictor of vote choice (voting for the DPS versus voting for other parties) compared to other authoritarianism dimensions that will show no effect on the response variable.

Finally, although economic and ethnic circumstances serve as significant contextual factors for enhancing submissive tendencies, it is important to attest whether they also have an isolated influence on voting for the DPS, given the importance of economic and ethnic conditions in Montenegrin political history. This research examines whether the effects of authoritarian submission are sustained when confronted with economic and ethnic indicators in order to demonstrate that this psychological construct is a valid explanation for DPS rule compared with other influential variables.

Analysis and Results

Let us now turn to testing the relationship between submission and voting preferences empirically, with the data from the Montenegrin National Election Study (2016) —and a self-designed student survey (see appendix 2). The first part of the section provides the MNES (2016) findings, while the concluding part summarizes inferences from both the national and the student survey.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

The MNES data was gathered in 2016, on a national sample representative for Montenegro—1,213 respondents with the +/-2.81% margin of error for 50% of the reported percentage (MNES 2016). The sample distribution of sex is roughly uniform (women at 51.07%, men at 48.93%). Respondents with high school education (48.43%) dominate the sample; college-educated individuals comprise 27.89% of the sample, while 23.68% finished elementary school or less. There is a proper distribution of age: 35.90% of the respondents are middle-aged (35–54); 31.01% are in the category of young (18–34); and 33.08% of respondents are categorized as old (55 or older).

The ethnic composition of the sample did not show wide discrepancies compared to the census data presented in parentheses. Montenegrins consist of 56.23% (45%) of the sample, Serbs 22.64% (28%), Bosniaks 8.65% (9%), Albanians 4.32% (5%), and respondents of other nationalities are the remainder 8.16% (9%) (MONSTAT 2011). The demographic structure of the sample does not show notable deviations from the structure in the general population. This is very important, given that severely biased ethnic, age, or educational distribution can distort the results of any analysis.

Measurements

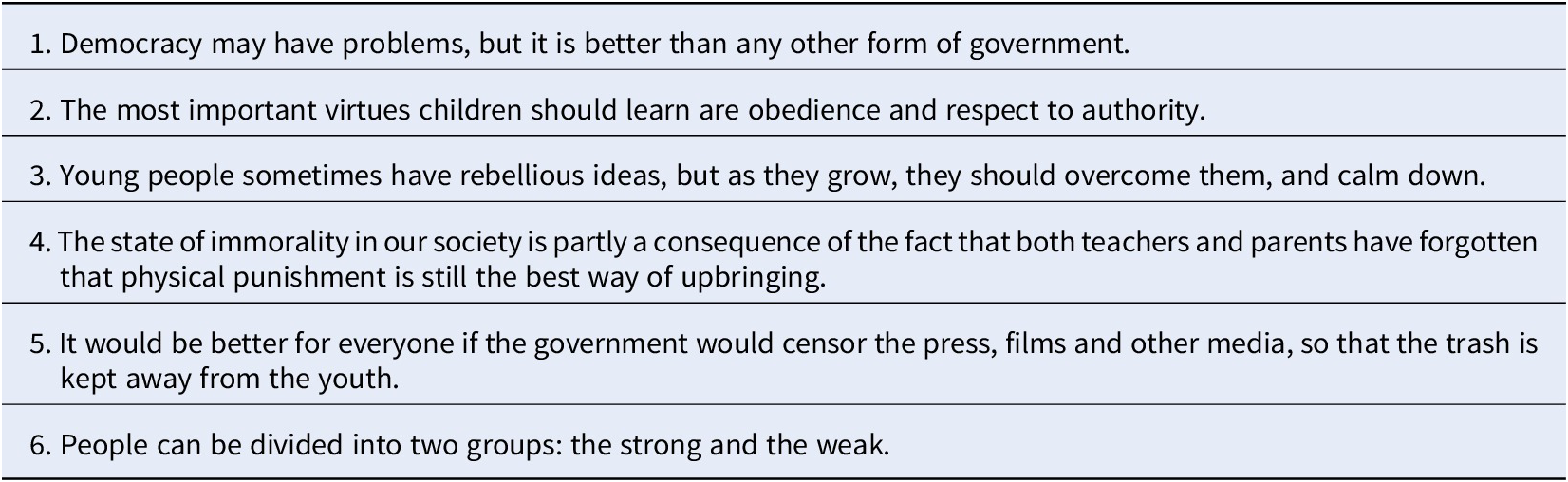

I operationalize authoritarian submission, as the major explanatory variable, from the set of six survey items that measure authoritarianism (Cronbach’s Alpha=0.76). Items were selected from the Adorno et al. F-scale and Altemeyer’s RWA scale. On each of these items, respondents indicated a level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale (see table 5).

Vote choice is operationalized through a post-election vote question “For whom did you vote on last elections” survey item. Self-reported vote choice might be a problematic indicator, especially for respondents lacking a sense of anonymity. However, it is still widely used in survey research as the most common method of analyzing a voting process that is not prone to direct observation.

Control Variables

I include several control variables to measure the effects of the explanatory variable properly.

Age and education serve as important demographic factors explaining individual propensity to authoritarian tendencies. Namely, individuals that grew up in authoritarian political surroundings are less likely to let go of the values and beliefs they employed there (McAllister Reference McAllister, Dalton and Klingemann2007). Additionally, higher education levels are supposed to modify and weaken authoritarian tendencies (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Pratt, Olsen and Alisat2016).

As argued before, ethnicity presents another significant demographic variable. Given the Montenegrin-Serb polarization in Montenegrin parties and society, controlling for this variable will enable me to analyze the effects of authoritarian submission more accurately. The analysis includes two dummy variables representing Montenegrin and Serb ethnic belonging. These indicators capture the ethnic polarization in Montenegrin society, since the mere ethnic identification is proven to have political relevance (Džankić Reference Džankić2014) and continuously affect voting preferences in this country (Komar and Živković Reference Komar and Živković2016; Komar Reference Komar2013), even in an experimental setting (Stankov Reference Stankov2016).

I include two more variables as controls. The first is political interest as a measure of political sophistication. Sophisticated individuals are less prone to rely on attachments to the leader when deciding whom to support (Bittner Reference Bittner2011).

The second control variable is satisfaction with the economy. Respondents were asked whether the “Montenegrin economy greatly improved, somewhat improved, remained the same, got somewhat worse or worsened completely, during the last twelve months” (MNES 2016). This variable measures subjective economic perceptions since individuals enjoying the advantage of the DPS rule might perceive the economy as enhanced, even though objective indicators demonstrate otherwise. Moreover, subjective indicators provide better insight into “one’s sense of existential security” (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2017, 141). To measure the relationship of both subjective and objective indicators, I include employment status, given the continuously modest employment and activity rates in Montenegro (European Commission 2019).

The Gist of the Story: Submissiveness and Party Preferences

Before I test the hypotheses through regression analysis, I conduct an exploratory factor analysis to reveal the multidimensionality of the authoritarianism scale. I apply the principal axis factoring method with oblimin rotation. The factor analysis extracted authoritarian submission as the first factor. As table 6, shows, this factor loads on three items measuring authoritarian submission (0.66, 0.91, 0.31). The second factor the analysis extracted I named conventional aggression; the items this factor recognized (0.77, 0.50, 0.81) originate in both conventionalism and authoritarian aggression dimensions of the F-scale and RWA scale. The two factors explain 43% of the variance.

To test my hypotheses, I performed logistic regression, which I consider the method with the least disadvantages for several reasons. First, out of authoritarian submission and conventional aggression items, I have created two separate additive indices, followed by the items that the factor analysis extracted. Additionally, my major explanatory variables (authoritarian submission and conventional aggression) are of a continuous nature, and my response variable is dichotomous, which is a necessary precondition for logistic regression. Second, logistic regression allows me to see how each variable in the model individually affects the response, enabling me to quantify the strengths of these effects properly. Finally, the hypothesized relationship among variables indicates that a one-unit increase in authoritarian submission (on a five-point scale) affects the probability of voting for the DPS, as indicated in the following formula:

$$ \ln \left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right)={\beta}_0+{\beta}_1 AuthS+{\beta}_2 ConAgg+{\beta}_3 MNE+{\beta}_4 SERB+{\beta}_5 Age+{\beta}_6 Edu+{\beta}_7 Sex+{\beta}_8 PolInter+{\beta}_9 Eco+{\beta}_{10} Emp $$

$$ \ln \left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right)={\beta}_0+{\beta}_1 AuthS+{\beta}_2 ConAgg+{\beta}_3 MNE+{\beta}_4 SERB+{\beta}_5 Age+{\beta}_6 Edu+{\beta}_7 Sex+{\beta}_8 PolInter+{\beta}_9 Eco+{\beta}_{10} Emp $$

Namely, the log odds ratio -

![]() $ \mathit{\ln}\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right) $

of the binary outcome (1-vote DPS, 0-vote other partiesFootnote

10) is presented here as a function of several explanatory variables (from β1AuthS to β10Emp, where β presents a coefficient for each explanatory variable). β0 presents an intercept of the logistic regression; it determines the outcome when all the predictor variables equal zero (Gravetter and Wallnau Reference Gravetter and Wallnau2016, 450).

$ \mathit{\ln}\left(\frac{p}{1-p}\right) $

of the binary outcome (1-vote DPS, 0-vote other partiesFootnote

10) is presented here as a function of several explanatory variables (from β1AuthS to β10Emp, where β presents a coefficient for each explanatory variable). β0 presents an intercept of the logistic regression; it determines the outcome when all the predictor variables equal zero (Gravetter and Wallnau Reference Gravetter and Wallnau2016, 450).

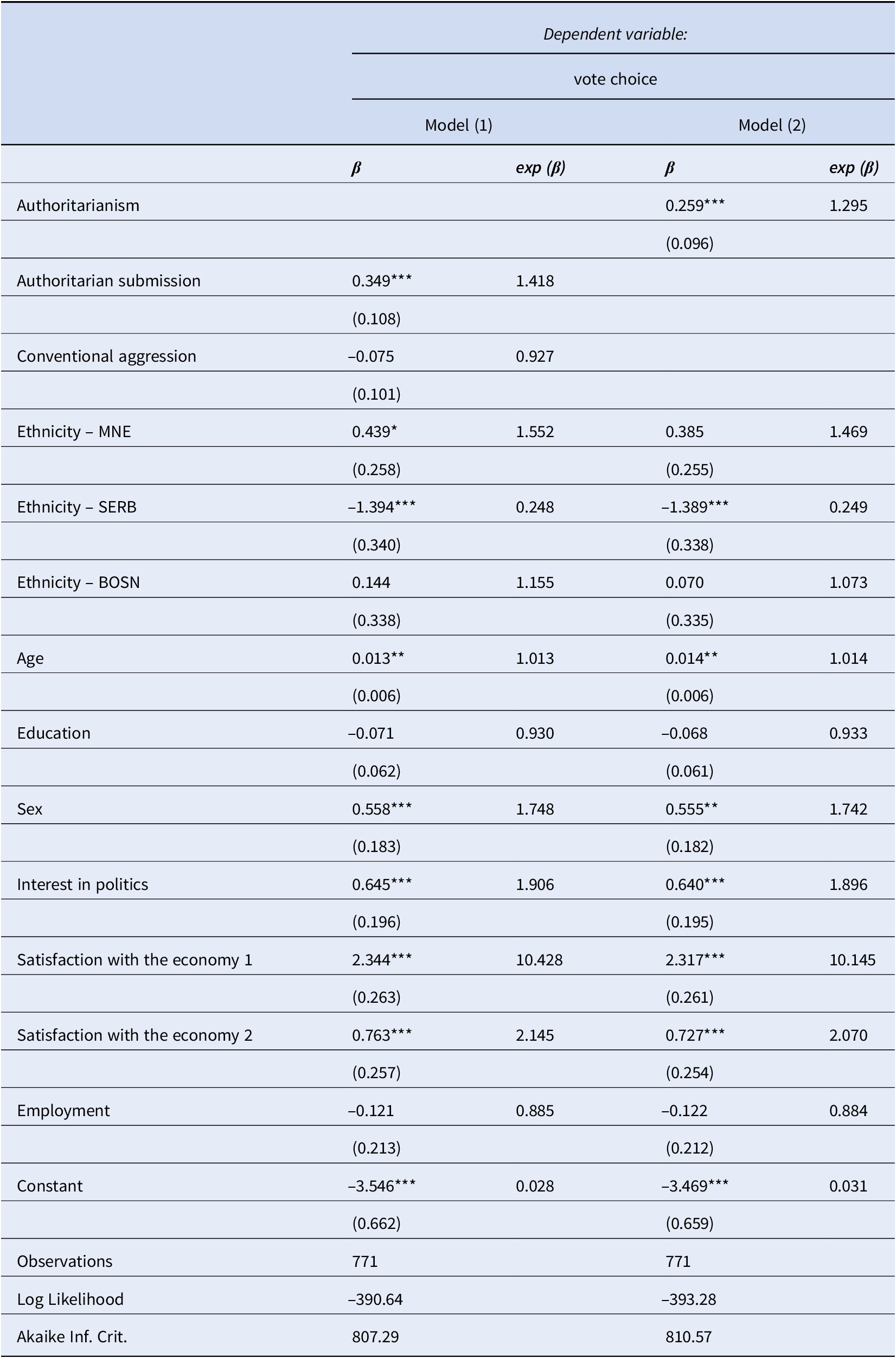

Table 7 shows the test of two models: the separate effects of authoritarian submission (AS) and conventional aggression (CA) on vote choice (Model 1); and the overall effect of authoritarianism on vote choice (Model 2). The results of Model 1 unambiguously show the positive effect of authoritarian submission on the individual propensity to vote DPS. As presented in table 7, with a one-unit increase in authoritarian submission (on a five-point scale), individual likelihood to vote DPS, compared to voting for other parties, increases by 41% (β=0.349).

Table 7. Logistic Regression Analysis Results

Note: ∗p<0.1; ∗∗p<0.05; ∗∗∗p<0.01; standard errors in parentheses. Each model was validated with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test of model fit and a classification table, which presents the percentage of correctly classified cases by the model. Model 1: X2 (8)= 8.6309, p-value = 0.37, correctly classified cases: 75.6%. Model 2: X2 (8)= 7.9444, df = 8, p-value = 0.43, correctly classified cases: 75.6%.

Furthermore, these results provide support for my second hypothesis: conventional aggression is not a statistically significant predictor for vote choice.

Additionally, I have estimated regression coefficients with standardized independent variables, and the effects present in table 7 were sustained.Footnote 11 Thus, the results from Model 1 are in accordance with my expectations that authoritarian submission will have a positive predictive power for voting DPS, compared to voting for other parties, but prior to all, that the multi-dimensionality of authoritarianism scale must be revealed for proper interpretation of its effects. If a researcher did not acknowledge the different authoritarianism dimensions, they would be mistakenly led by the overall result, without identifying which parts of the authoritarianism scale are relevant. The unidimensional authoritarianism measure, created out of authoritarian submission and conventional aggression items (Model 2, with all other parameters kept the same), has a statistically significant result: a one-unit increase in authoritarianism (on a five-point scale) increases individual odds for voting DPS, compared to voting for other parties, by 29% (β=0.259, p<0.01). This result could be interpreted as the existence of the overall effect of authoritarianism, but as shown, we can argue only for the substantive and stronger effect of authoritarian submission.

Further, table 7 (Model 1) reveals a significant contribution of several control variables to vote choice. In order to capture Montenegrin/Serb polarization, I have included two dummy ethnicity variables in the model. As previously noted, the DPS is clearly associated with Montenegrin ethnic belonging. Voters dominantly recognize this party as representing pro-Montenegrin politics. As expected, ethnic belonging presents an important factor—Montenegrins are 55% (β=0.439) more likely to vote DPS than voters of other ethnicities. Intuitively, respondents who declare themselves as Serbs are 67% (β=-1.394) less likely to vote DPS than voters belonging to other ethnic groups. These results reflect the ethnic polarization in Montenegrin society. Ethnic Montenegrins have a stable likelihood of voting DPS, compared to ethnic Serbs.

Additionally, the analysis shows that females are 74% (β=0.558) more likely to vote DPS than other parties. Women account for 51% of voters in Montenegro (UNDP 2012). Additionally, 58.59% of women voted for the DPS, compared to 49.33% of men (CSES 2012). In the context of authoritarian submission, it would be pretentious to assume that sex as such determines submission (correlation between the two variables is marginal; Polyserial correlation: r=0.05). However, when I run frequencies on individual leadership measures, the result is somewhat different.Footnote 12 40% of women support the idea of having a strong leader in the Montenegrin government “even if the leader bypasses the rules to do the job successfully” (MNES 2016), compared to 33% of men. Cross-tabulation of sex and age revealed that 52.57% of females in the sample are young (aged 18–34), while the Westminster Foundation for Democracy found that young Montenegrin women demonstrate a higher level of institutional trust and more reliance on leader and ideology as factors “decisive for voting” (WFD 2020, 43). The additional data shows that the influence of biological measure of sex has more profound social implications. Simultaneously, the relationship established in this article requires further scrutiny with the central role of demographic indicators.

Furthermore, although age has a statistical significance, the effect is not substantive. With every additional life decade, the individual likelihood for voting DPS, compared to voting for other parties, increases only by 1% (β=0.013).

Finally, those who are interested in politics are 90% (β=0.645) more likely to vote DPS. The interpretation of this result relates to voters’ motivation and the DPS’s “image of invincibility” (Komar and Živković Reference Komar and Živković2016, 785). Voters tend to be on the winner’s side (Anderson and LoTempio Reference Anderson and LoTempio2002), and the DPS, with its uninterrupted dominance, created an atmosphere where its supporters are permanently motivated to vote (Živković Reference Živković2017). Komar and Živković (Reference Komar and Živković2016, 800) found that the image of invincibility increases the likelihood for voting DPS by 19 times. The political interest variable in this research confirms that the constant dominance of the DPS brings constant voting motivation to its electorate.

Further, an individual perception that the Montenegrin economic situation is improving in the last 12 months also functions as a good predictor: respondents with such perception are 10.42 (β=2.344) times more likely to vote DPS, compared to individuals that perceive the economic situation as worse. Further, individuals who think that the economic situation remained unchanged are 2.14 (β=0.763) times more likely to vote DPS than those who think that the economic situation has worsened. Namely, subjective indicators are in question, while objective indicators, such as employment, do not have any influence on vote choice. Thus, this high result refers only to those who think that everything is turning out well and those who argue that nothing changed dramatically. Given the clientelist networks of the DPS, optimist and neutral voters intuitively associate economic improvements with the incumbent government that has the largest share in economic issues and the greatest access to resources. This is especially the case if voters personally experienced some benefits, which in turn makes them perceive the overall situation as better or unchanged.

The results presented here show that individual votes for the DPS can be interpreted as a function of submissive tendencies, positive perceptions about the economic situation in Montenegro, and the ethnic cleavage. Additional control indicators have shown that females and those interested in politics dominate the electoral body of the DPS. Simultaneously, submissive tendencies are meaningfully increasing individual odds of choosing DPS over other parties. The most important finding is that the relationship between authoritarian submission and vote choice is sustained under controls, especially the ethnic divide and economic preferences. Additionally, the analysis confirms that other dimensions of authoritarianism (in this case, conventional aggression) do not present potent factors in individual tendency to vote for the incumbent party.

However, the MNES research did not include proper measures of the other authoritarianism dimensions; therefore, I scrutinized this finding with another survey—a student sample, where I designed particular questions to capture the authoritarian submission.Footnote 13 The overall inference from MNES and the student survey is that DPS voters do not show intergenerational differences in submission. Linear regression analysis indicated the positive effect of authoritarian submission on the individual propensity to vote DPS.Footnote 14 Further, 67.44% of students support the idea of having “fewer laws and agencies, and more courageous, tireless, devoted leaders whom the people can put their faith in” (see appendix 2). Every second student respondent believes that obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn (56.25%). Simultaneously, 49% of students show paternalistic tendencies—they agree that the government should take more responsibility to secure them, instead of making an individual effort to secure themselves.

The specifically designed survey questions allow for a more refined analysis of authoritarian aggression and conventionalism, but the tests confirm the hypothesis that these do not affect the propensity to vote DPS. Again, this conclusion could not be derived if authoritarianism would be treated as a unidimensional syndrome. Without revealing the underlying structure of authoritarianism, one could mistakenly argue for the importance of this personality structure as a whole, while the authoritarian submission is the only dimension that affects the vote choice.

The effects of ethnicity are also sustained, where Serbian ethnic belonging shows the strongest negative influence on the propensity to vote DPS.Footnote 15 These results are an additional confirmation that DPS supporters still associate this party with its pro-Montenegrin politics, and they experience it as a protégé of Montenegrin independence. In the context of satisfaction with the Montenegrin economy, students are more dissatisfied than the nationally representative sample. In the MNES data, 27.57% of respondents think that the economic situation is getting better in the past ten months, and 30.51% of those disagree and argue that the economic situation has worsened. In parallel, only 7.69% of student respondents reported being very or somewhat satisfied with the economy, while 71.49% expressed dissatisfaction. These differences have a social and political dimension. Students are mainly an unemployed or partially employed population, usually still economically dependent on their parents. Second, students themselves experience anxiety for their future employment. The 2017 United Nations Development Programme report acknowledges the high unemployment rate of the youth (35%–40%), with “almost 10,000 unemployed young people in Montenegro” (Katnić Reference Katnić2017, 9). Students whose family members personally experienced economic disturbance might be more dissatisfied with the economy, compared to those who did not. Namely, 76% percent of dissatisfied students stated they would never vote DPS if the elections were held next week, supporting the intersection between the economic situation in Montenegro and voting preferences.

Conclusion

I introduced authoritarian submission as one of three dimensions of authoritarianism (together with conventionalism and authoritarian aggression) that describes individual relations to authority. I argued that submissive habits, originally adopted in the upbringing process but reinforced in a conducive socioeconomic environment, positively affect the dominance of the DPS. The two surveys, conducted in a nationally representative sample (MNES 2016) and a student sample (see appendix 2), showed that authoritarian submission could explain citizens voting for the DPS. The effects of submissive preferences are sustained, even when confronted with ethnic and economic variables, which act as important contextual conditions and influential voting factors. Both the MNES and the student survey confirmed that supporters of the DPS still recognize the party as an emanation of Montenegrin orientation and autonomy, while subjective perceptions about the improved economic situation increase the individual propensity for voting this party, thus indicating an association between economic perceptions and party preferences.

The student survey demonstrates that submissive tendencies matter for voter choice even for the young and educated, which further points to the relevance of the development of authoritarian submission. Young people are presupposed to be the most unlikely group to exhibit authoritarian submission, since these respondents are young enough not to hold memories (and values) of the 1990s. However, authoritarian upbringing, together with unstable economic and divisive ethnic conditions in Montenegro, enabled the transmission of submissive behavior to the younger population. This mechanism helps the endurance of obedience. We can observe this argument in an economic context as well—students are mainly dissatisfied with the economy, but still expect the government to secure their future. This seemingly ambivalent attitude reveals a preference for paternalistic rule, another indicator of a dependent relationship to authority.

The persistent attachment to authority, together with a lack of individual interest in scrutinizing political decisions, prevents the development of democracy. More attention should be dedicated to unraveling and analyzing the less palpable dimensions of authoritarianism that are nevertheless relevant for democratic performance. As Passini argues, those who are submissive but not aggressive are “not […] less dangerous for democracy” (Passini Reference Passini2017, 83). This research points to attitudinal democratization as one of the core conditions for building vibrant democracies in the post-communist area. If democratic changes fail to penetrate individual mindsets or the psychological mechanisms of submission persist, the speed, character, and future of democratic progress remain questionable for post-communist societies.

An additional essential finding of this research demonstrated that analyzing authoritarianism, as a unidimensional concept, is highly misleading. Without separating the three underlying dimensions, one would fail to map those individuals that are susceptible to political authority, but not hostile to others or conventional in their beliefs (Passini Reference Passini2017, 74). Authoritarian submission is less visible than aggression, but not less important. Passini (Reference Passini2017, 83) further recognized that the focus is always on those who are louder; however, ignoring or overlooking those who are silent is equally problematic. The three-dimensional authoritarianism model, tested in this article, provides a better understanding of an electorate that supports strong leaders. Uncritical submission challenges the essence of democracy reflected in individual engagement and active involvement in (re)questioning the existing power-relations.

Finally, it is important to note that this study is characterized by several limitations that could serve as a direction for further research. First, internal validity is a disadvantage of survey research as a method. The control level is lower compared to experimental studies, thus enabling the researcher to argue the contribution of the explanatory variables, but not their causal effect. In parallel, survey research can generalize results to a broader population with an increased external validity that is dubious in experimental research. Second, when confronted with interpersonal survey settings, submissive individuals may have reported voting DPS, even if that was not their original choice. Disadvantages of survey research must be acknowledged, although this method presents the most common analysis of the voting process.

Additional analyses should investigate the influence of authoritarian submission from a comparative perspective. Namely, the obvious limitation that follows case studies is their inability to generalize to other cases. This article demonstrated that psychological factors, such as authoritarian submission, are an important addition to the analysis of the post-communist societies that experienced a turbulent political past. Thus, further research should investigate how the authoritarian submission model presented here behaves in a broader post-communist perspective. The psychological perspective exposed in this article presents a mechanism of inner control and the internal legitimacy of the dominating party. Further research should complement this perspective with examination of the strategies that leaders of post-communist countries use for external legitimation. Both internal and external analyses have the potential to reveal the success of democratic adaptation of post-communist societies.

Acknowledgements

I am profoundly grateful to Professor Robert Sata, whose generous and invaluable assistance made this article possible. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback, which substantively improved the article.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Central European University Foundation of Budapest, under Grant BPF/2017/18.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.61.