Introduction

After its defeat in the Crimean War (1853–1856), the Russian Empire sought to reassert its presence in the areas surrounding the Black Sea. Narratives of the suppression of Slavic peoples in the areas governed by the Ottoman Empire gave the Russian Empire a reason to challenge the contemporary political situation in the 1870s. The problems experienced by the Bulgarians in the areas governed by the Turks represented a final catalyst for Tsar Alexander II to get involved. The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, a conflict involving the Ottoman Empire and the Eastern Orthodox coalition of the Russian Empire and several Balkan states, involved strong ideological-religious undercurrents. The rising nationalism in the Balkan area, combined with the discrimination experienced by Christians in the Ottoman Empire and the pan-Slavistic ideas of shared Slavic and Orthodox consciousness created a situation that served as a justification for Russia to promote more pragmatic goals, too. (See Kivelson and Suny [Reference Kivelson and Suny2017, 194–199] and Pavlowitch [Reference Pavlowitch1999, 110–115] for a general overview of the background of the war.)

The uprisings of Balkan Slavs from 1875 onward, and especially the Serbo-Turkish War preceding the military involvement of Russians, raised notable interest in Russia. In addition to fund-raising coordinated by the Slavic Committees, Russian volunteers joined the Serbian army before the official declaration of war. The interest of the people in the “Eastern question” was fed by information published in newspapers on the events in the Balkans. The descriptions of what was going on also added pressure on the government to get involved (Nikitin Reference Nikitin1960, 302–306; Hosking Reference Hosking1998, 333).

In addition to newspapers and journal articles, a wide array of popular lubok images (or lubki, to use the Russian plural) were printed and distributed concerning the events in the Balkans. In general, lubok prints consisted of illustrations of religious or secular topics, often with some explanatory text. People bought these pictures from itinerant peddlers to decorate the walls of their houses. The lubok images illustrating the Russo-Turkish War celebrated military gains by the Slavs, highlighted their heroic deeds (especially those of the Russians), and emphasized the idea of the religious nature of the war, Orthodox Christians defending themselves against the Islamic threat (Norris Reference Norris2006, 83–97; Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 62–67; Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2011, 257–258).

Alongside printed pictures, cheap popular booklets concerning the events in the Balkans emerged, their production peaking in 1877–78. Popular literature in general had emerged simultaneously with the growing literacy rate in 19th century Russia, and the number of copies sold rose rapidly during the latter half of the century. Jeffrey Brooks uses the concept “the literature of the lubok” to describe these cheap, crudely printed booklets. Popular-historical accounts and scientific publications intended for common readers, as well as propagandistic material, were printed, along with romantic stories, folkloric tales, and other fiction (Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 67–80).

The popular publications concerning the Russo-Turkish War seem to fall between propaganda and stories written to entertain rather than educate. Although the events inspired authors to write fictive stories, too, most of the publications concerning the Balkan issue described the events and politics preceding and causing the war and military proceedings during the campaign. These popular accounts were, nevertheless, far shorter and less detailed—and more emotional and dramatic in style—than were, for instance, books published by military personnel and volunteers who had participated in the war. The booklets were also published and distributed by important producers of cheap popular literature, such as Sharapov and Morozov in Moscow (Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 95). Therefore, it is appropriate to include these popular historical-political publications, commenting on contemporary issues, in the literature of the lubok.

The booklets aimed at general readers were mostly produced by anonymous authors. In general, writing lubok literature was not considered an especially worthy pastime, and many authors had a peasant background and were not members of the educated elite (Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 80–82). When it comes to the authorship of texts concerning the Russo-Turkish War, there were some exceptions, and in general, it can be assumed that writing persuasive historical-political pamphlets required more education and feeling of purpose than did, say, adapting folk tales.Footnote 1

What is important to keep in mind, however, is that no matter the identity or individual opinions of the authors, the censoring process during the 19th century ensured that ideas expressed in the publications were more or less aligned with the empire’s official views of the issues, or at least not blatantly contradictory to them. Because both church and state officials considered crucial the question of what common people should or should not read, the production and distribution of printed works was monitored, and writers were required to submit their works to censors prior to publication (Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 60, 100; Norris Reference Norris2006, 9. For more about practices of censorship, see Balmuth [Reference Balmuth1979, 59–79]. As Hosking [Reference Hosking1998, 331] points out, lubok booklets were not included in the material for which censorship was ended after 1865).

Therefore, the publications can be claimed to represent the contemporary conceptions of the war and the events connected to it—not those of individuals (those would be quite impossible to examine, apart from certain exceptions, the authors who chose to write about them under their own names), but the collective ones. The information about the events in the Balkans as published in the popular booklets could also be defined as a proposed ideological framework for approaching the issue. The booklets—like the lubok pictures—not only reflected but also created, consolidated, and disseminated a certain collective image, or imagery, of what was going on in the Balkans and the role of Russia in the conflict (Norris Reference Norris2006, 8).Footnote 2 But unlike pictures—usually depicting a certain military event—the textual form enabled the producers to effectively contextualize the events (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cover, Vladimir Suvorov, Krovoprolitnaia bor’ba s musul’manami ili russo-turetskaia voina. Sovremennyi ocherk (1877). National Library of Russia.

While accessible publications concerning the contemporary military events undoubtedly were of some interest to any literate and at least semi-educated Russian, for those potentially involved in military activities they conveyed a special persuasive message: that of inspiration, motivation and the feeling of greater purpose (Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 60). These kinds of booklets had educative, persuasive, and even propagandistic functions. The publications produced before 1878 emphasized the importance of collective sacrifice for the common cause (civilians were urged to donate money for military efforts), while those published after the peace treaty brought forth the victorious campaign fought by the Russian army and the “Slavic brothers.” Apparently, Russians did need persuasion: for some of them the events in the Balkans were equated with the Polish uprising against Russian domination in 1863, and as such, revolt against the legitimate power (Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2016, 198). Moreover, the imagery (re)produced and disseminated through the publications was linked to contemporary internal issues concerning Muslim societies of the Russian Empire.Footnote 3

In general, it is very difficult—if not altogether impossible—to examine the reception of the imagery among masses, for instance, to study how the ordinary people, having access to more or less propagandistic material, actually perceived military events and their context. In the case of the Russo-Turkish War, however, some 19th-century accounts by contemporaries did examine the peasants’ ideas of the events. They indicate that people even in the countryside—getting information mainly from newspapers and local priests—had some kind of patriotic feeling about the war and that they considered the conflict primarily as a struggle of the Christian faith against infidels (Buganov Reference Buganov1987; see also Norris Reference Norris2006, 97–102).

Nevertheless, by studying the imagery of the popular booklets, we can learn about the producers of the images: their choices, interests, and goals for producing certain kinds of representations of a certain issue. Reception is implicitly included, as Stephen Norris has formulated: “the national and patriotic identities espoused in the war lubki represent both an elite attempt to inspire loyalty to symbols and myths of the Russian nation and a popular attempt to understand them” (Norris Reference Norris2006, 9).

In this article, I examine the kinds of issues and images the authors of the booklets wanted to convey to their readers regarding the historical-political context and moral justification of the war, and why. Due to its wide distribution and the censoring process, material that was available for—and intentionally aimed at—common people is especially valuable in examining the ideological atmosphere surrounding the Balkan campaign during the war, and the collective images of the ethnic and religious groups involved. Instead of focusing on the descriptions of the military events and manoeuvers (quite straightforward as such) we might ask how the authors chose to represent the historical context of the conflict. What kinds of attributes were applied to diverse ethnic groups, especially Balkan Slavs and Turks, involved in the events? How were the roles of Russia and other nations represented? With these questions, we can probe issues—such as the use of established ideas of the national past in contextualizing contemporary events—and conceptions concerning Russia’s geopolitical position, the Russian nation, and “Russian-ness” in the 1870s.

Popular booklets were by no means the only media taking a stand on the topical “Eastern question.” In addition to the lubok pictures were books depicting experiences of Russian volunteers in the Balkans. Liberal newspapers, such as Novoe vremia (New Age) and Golos (Voice) published on the issue, as did the more conservative, pan-Slavistic Russkii mir (Russian World), one of the publishers of which was General M. G. Cherniaev (1828–1898), the commander in chief of the Serbian army in the Serbo-Turkish War (Nikitin Reference Nikitin1960, 294–302). Further, certain journals dealing with history, politics, and literature, such as Vestnik Evropy (The Messenger of Europe) and Russkii vestnik (Russian Messenger) among others, published numerous articles in 1877–78 concerning the events in the Balkans. One especially devoted writer publishing in Russkii vestnik was Aleksandr Nikolaevich Pypin (1833–1904), who wrote numerous articles on the Balkan and Slavic issues using either his whole name or (presumably) his initials “A. N.” (Entsiklopedicheskii slovar’ Brokgauza i Efrona, T. 25A 1898, 92–94).

Explicitly pan-Slavistic viewpoints were brought out by N. I. Danilevskii (1822–1885), a versatile scientist, historian, and philosopher, who published both before and after the war on contemporary issues. He published articles in the newspaper, Russkii mir, and wrote a compilation, Rossiia i Evropa, of his views concerning Russia’s historical destiny (Woodburn Reference Woodburn, Danilevskii and Woodburn2013, xiv–xv; see also Thaden Reference Thaden1964, 99–115). Writers such as Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky also pondered on the events in the Balkans in their writings, to mention but a few (Milojković-Djurić Reference Milojković-Djurić2006, 1–16; Thaden Reference Thaden1964, 83–85).

Against this context, I focus on the contemporary popular booklets dealing with the Russo-Turkish War for the following reasons: First, the material was produced specifically for spreading information about the military events in the Balkans. Second, the publications supposedly had a relatively wide distribution among common people with no explicit political preferences. Their treatment of the topic was in general more emotional and dramatic than that of the articles published in journals; one presumes that the journals—the tone of which was analytical rather than persuasive—were aimed primarily at intelligentsia, while the readership of popular publications was, like that of school textbooks, a more diverse strata of Russian society. In addition, concentrating on a limited group of sources enables close reading with proper contextualization, aiming to form a conception of the treatment of a certain subject in a limited amount of texts.Footnote 4

“Mohammedan Yoke”: Historical Background

Creating a historical context for the military events was the starting point for many of the publications I examined. The authors of the booklets put a lot of effort into describing the background of the events in the Balkans in the 1870s. Some of them, like the writer of “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence,” began their accounts by describing the history of the Slavic peoples in the area (Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 6–58). Others started by depicting the beginning of the Turkish domination in the area. For instance, after pointing out the special role of the Russians in the matters of Slavs and Europe as a whole, the author of “The War between the Russians and Turks, 1877” wrote, “difficult times dawned on the Christians of the Balkan Peninsula in the middle of the fifteenth century: a terrible army of Turks from Asia Minor invaded the center of the whole Orthodox world, and the impact caused her to fall” (Voina russkikh s turkami 1877, 4).Footnote 5

Some of the authors explicitly depicted the conflict as a part of the continuum of struggle between Christianity and Islam, in which Rus’/Russia had a central role. For instance, the anonymous author of the booklet “The Russo-Turkish War and the Peace of Russia with Turkey in 1878, a Historical Viewpoint” noted that the Russian-Turkish War had been going on for centuries, and that even though other European countries had had their share of conflicts with the Muslims, Russia alone had a special position—“a great historical task”— regarding them: “On Russian people fell a difficult and great task in this gigantic war, and it had to carry on its shoulders the victory of light over barbarism, of development over stagnation, of freedom over slavery, and the glory of Christianity over slavery” (Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 3–4).

The author further describes the “first period” of the fight of the Rus’ with the Muslims. According to him, all the conflicts with the Tatars up to the 17th century were about protecting Orthodox Christianity; as explicit examples, he mentions the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 and the stand by the Ugra River by Ivan III’s troops. He compares the Tatar domination in Rus’ with that of the Turks in the Balkans, concluding that those in Rus’ suffered less than did the southern Slavs, because the Tatars were not a united enemy; they ended up quarrelling with each other, while Rus’ was a relatively strong state (Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 31–35).

In his booklet, Vladimir Suvorov also connects the contemporary war with the previous conflicts by mentioning that “this battle started long before our days, and it will go on now” (Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 20). In the beginning of his publication he explains how “400 years have passed since Rus’ was under a Mohammedan yoke. In order to be liberated from it, she had to use all her strength, and finally she managed to get rid of it in 1480. From that time onwards, roles changed. Previously the Russian people were assaulted by Tatars, now they began to assault them” (Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 5).

This development, according to Suvorov, gradually brought Russians into contact with Turks due to their interests in the Crimean Peninsula (Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 5–6). He also points out that while Russia’s primary motivation was to defend Christianity, rulers such as Peter I also wanted to ensure the empire’s access to the shores of the Black Sea for trading purposes (Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 37). A. I. Berens, too, depicts the historical problems experienced by Russians in encounters with Tatars, first emphasizing the early development of administration and trade in Rus’: “The Mongol invasion, with all its consequences, withholds the development of internal and external power of Rus’, and the warfare of Turks on the Balkan Peninsula in the 14th and 15th centuries sets an iron yoke of slavery on the Slavs of the Balkans” (Berens Reference Berens1877, 6–8).

Emphasizing the historical problems of Russians in their fight with Muslims was an especially effective starting point for the authors. It anchored the contemporary events mentally in the flow of time and contextualized them in both the Russian national narrative—formulated and consolidated during the 18th and 19th centuries—and the narrative embracing all Orthodox Slavic peoples. By the 1870s, the extent of the Russian schooling system was quite inclusive, with numerous sorts of elementary schools (Brooks Reference Brooks2003, 36–42). Because teaching Russian history was a part of the curricula, we assume that a large number of people already had some kind of understanding of events that were considered nationally important. Among these was the Battle of Kulikovo, which was hailed as a culmination point in the liberation of Russians from the “Tatar yoke.” (The anniversary of the battle was celebrated lavishly in 1880, and several publications that were published on the issue also touched on the contemporary Balkan questions and recent war [Parppei Reference Parppei2017, 157–180]).

Moreover, Suvorov emphasizes the national importance of the contemporary conflict by noting, “in the historical life of peoples there are not many such great events. Two or three times before this [the Russo-Turkish War] did the Russian people experience such remarkable events” and went on to list the Battle of Kulikovo, the Battle of Moscow during the Polish-Muscovite War (1612) and Napoleon’s invasion to Russia in 1812 (Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 24). The first two events had been similarly used to contextualize Napoleon’s campaigns in texts published from 1812 to 1814 (Parppei Reference Parppei2019, 153–159).

Comparing the liberation of Russians from the Tatars, and Balkan Slavs from the Turks—the Turks were presented as heirs of the Tatars in the texts—was an especially effective tool to enhance the importance of the contemporary mission and the significance of Russians in the events. It emphasized the idea of resistance as a historical duty; something that the readers’ ancestors had had to deal with, and the same task befalling the generation now in charge of making decisions. Focusing on early history and broad parallels helped the authors simplify the setting into a religious-ideological campaign with historical justification, and to avoid more complicated military and political turns and interests of the more recent past. For instance, the more recent and politically more relevant Crimean War was not an issue pondered upon in the publications.

Further, graphic depictions of the troubles of Slavs in the Balkans was something all the authors put a lot of effort into, even those who did not explicitly create a connection between historical events and the contemporary situation. For instance, in the booklet “The War with the Turks. Contemporary-Historical Viewpoint,” the anonymous author notes how “With terrifying power Turks emerged in Europe in the middle of the 15th century, and the first strikes were dealt to the Bulgarian-Serbian Kingdom [tsarstvo]” (Voina s turkami 1877, 5). According to the author, instead of resisting them, European nations gradually began to use the Turks to advance their own interests, and the Slavs of the Balkan area were left to survive on their own: “Unfortunate, forgotten, those Christian tribes, for longer than one century were forced to endure all the horrors of the Mohammedan yoke” (Voina s turkami 1877, 6).

Those horrors, according to the writers, included systematic persecution of Christians in the areas governed by the Turkish Empire, which they described in detail. The authors explained how the Orthodox Slavs faced pressure to convert to Islam; their property and food supplies were confiscated or stolen; women and girls were raped and many were killed or forced to become slaves; priests and teachers were persecuted with special fervor. Further, according to the texts, Christians were not able to seek justice in court, because only Muslims were eligible to act as witnesses (see Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 1–12; Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 40–54; Voina s turkami 1877, 7–13).

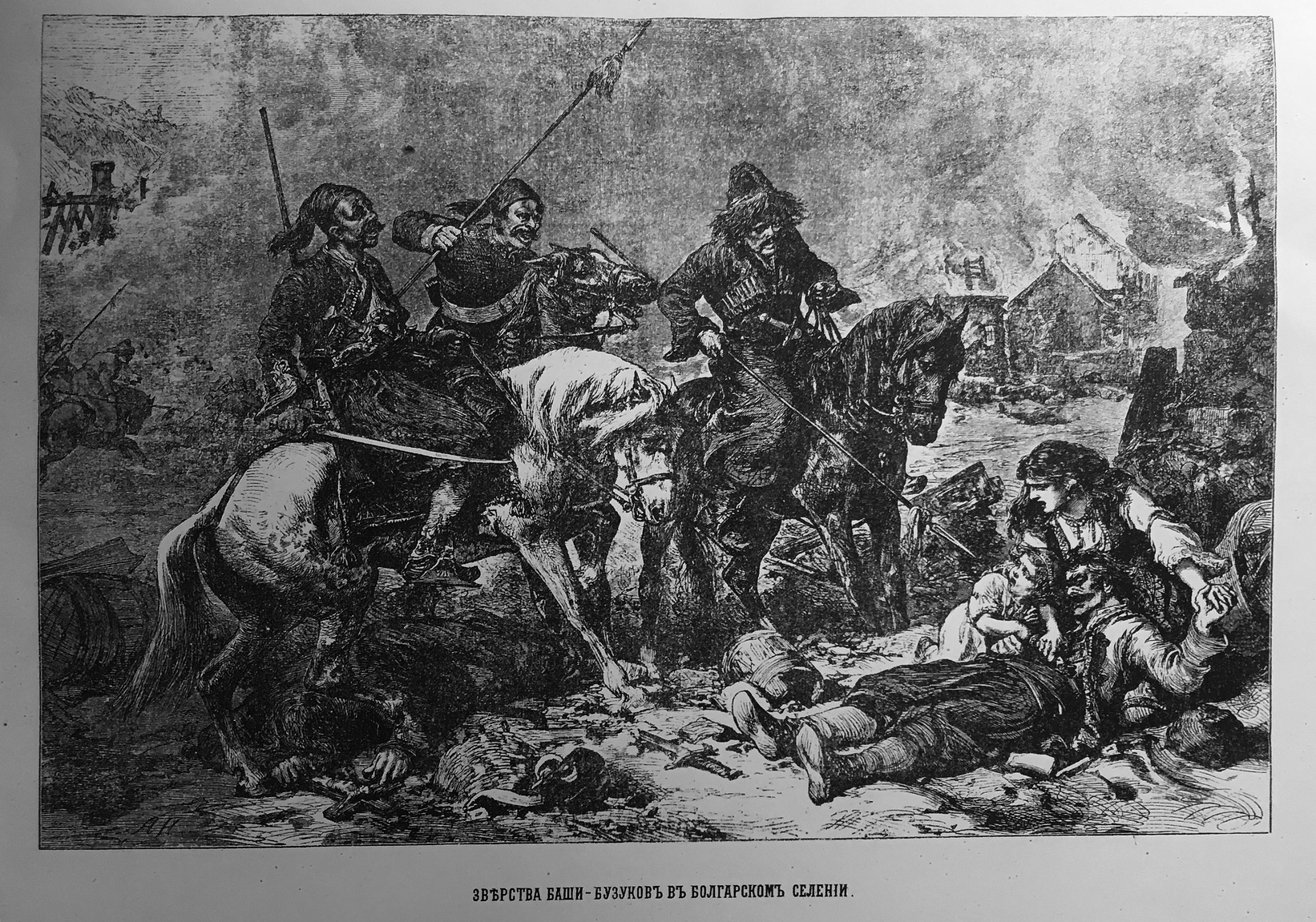

Mercenaries of varied ethnic backgrounds, called bashibazouks, were especially infamous for their alleged brutality toward Balkan Christians during the 1870s. This was noted by the authors. For instance, in “The War of Serbs, Herzegovinians and Montenegrins, or the Battle of Slavs with Turks,” the author describes how they “burned unarmed Christian villages, mercilessly slaughtering Slavs” (Voina serbov, gertsegovintsev i chernogortsev 1877, 7; see also Pavlowitch Reference Pavlowitch1999, 109). Some of the depictions of violence were very detailed and brutal, as this one describing the sufferings of Bulgarians in M. Malykhin’s “The War with the Turks in 1877”:

from one, eyes were gouged out, and from others ears, hands, or feet ripped off, and so on. Close to them a woman was lying, still half-alive, wriggling in agony preceding death and holding in her hand the head of her killed child. On the road, close to a fence, laid a woman with a severed head, and her six-months-old child was sucking her breast. Noticing this, one of the soldiers guffawed and, taking his rifle, pierced the child’s stomach; the unfortunate little one began to cry.

(Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 11)Such emotional and graphic descriptions of the sufferings of innocent Slavs in the hands of infidels were undoubtedly very effective in justifying the involvement of Russia in the Balkan area. The scenes were, apparently, far too gruesome to be printed as lubok pictures—for which Russia’s military gains were a more appropriate and uplifting topic—but textual depictions of the horrors created equally vivid images in the readers’ minds (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Illustration of bazhibazouks harassing Bulgarian villagers. Slavianskaia voina za nezavisimost’ (1876). National Library of Russia.

Some authors were lavish in their use of narrative devices to convey their message. For instance, a combination of emotional fictive story and political-historical pamphlet, “The Salvation of a Christian Woman by Russians, or the Eastern War,” depicted a beautiful Bulgarian maiden being stolen from her home village on the eve of her wedding and ending up in a Turkish pasha’s harem as a slave. The narrative, with undeniably symbolic overtones, begins and ends with a tragedy: the maiden, whose fiancé was killed in the invasion, is finally rescued by Russian troops, but too late; she perishes missing her homeland (Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877).

A very similar, deeply symbolic story with a slightly happier ending—the Bulgarian girl survives and marries her Russian rescuer—was “The White Russian General, or the Saved Bulgarian. A Story from the Russo-Turkish War” (Belyi russkii general’ ili spasennaia bolgarka Reference Leont’ev1878). These fictional stories represent the persuasive and propagandistically effective imagery of masculine and capable Russian soldiers stepping in to protect feminized South Slavs, often represented by “damsels in distress” (Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2011, 251–263).

“Brothers in Tribe”: The Slavic Groups Involved

Pan-Slavism—a movement that originated in the western Slavic countries after the Napoleonic Wars and was intertwined with Slavophilistic thinking in Russia—was not openly supported by the empire, for the idea of a union of all Slavic people was considered too provocative an approach in relation to western European countries (Milojković-Djurić Reference Milojković-Djurić2006, 39; as Vovchenko [Reference Vovchenko2016, 92] points out, pan-Slavism was originally a concept coined by western journalists). Nevertheless, pan-Slavistic undertones could be detected in the Russian imperialistic thinking and the empire’s politics with the Ottoman administration, even though the main motives for declaring war were apparently dictated by realpolitik rather than any ideology. “Slavic Committees” in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and some other larger cities were founded after the Crimean War in order to support Slavic peoples living in the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires. Pan-Slavistic—and pan-Orthodox—ideas were peaking in Russia right before the Russo-Turkish War; however, disappointments concerning the consequences of the war resulted in the loss of pan-Slavism’s popularity by the turn of the 1880s. (For more information about pan-Slavism in Russia, see Gülseven Reference Gülseven2017, 333–336; Gerd Reference Gerd2014, 3; Pavlowitch Reference Pavlowitch1999, 115. For a comprehensive account of the complex religious-political setting and turns preceding the Russo-Turkish War, see Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2016).

In the lubok booklets, the detailed descriptions of the historical sufferings of the Slavs were seamlessly intertwined with depictions of the ethno-religious setting in the Balkan area. Pan-Slavistic tendencies were the firm foundation on which all the depictions were built: Balkan Slavs were represented, for instance, as Russians’ “brothers in tribe [po plemeni] and in faith” in the publication “Slavic War for Independence” (Slavianskaia voina za nezavisimost’ 1876, “Obiavlenie”)Footnote 6 or “our Balkan co-believers” in “The Feat of a Russian General or Russo-Turkish War” (Podvig russkago generala 1877, 10). For instance, Malykhin begins his booklet with this note:

About five hundred years ago, Turks arrived from the steppes of Asia and conquered Slavic peoples, Serbs, Bulgarians and others, which lived by the river Danube and its tributary Sava. All these peoples are our relatives, because they derive from the same Slavic tribe as we Russians, and pray to the same Orthodox God as we do; therefore, they have a right to count us among their brothers and trust in our assistance.

(Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 1)The anonymous author of “The War between the Russians and Turks” also confirmed the common descendance of Slavic peoples: “With Byzantium, it [Russian people] was united by one religion, and with Slavic tribes also by general tribal kinship: because Russian people were descendants of those Slavs, who also produced Serbs and Bulgarians and Czechs, and other Slavic tribes” (Voina russkikh s turkami 1877, 11).

In Russian pan-Slavistic thinking, Russia’s role was crucial in bringing forth the heyday of the Slavs (see Kivelson and Suny Reference Kivelson and Suny2017, 196). The authors of the publications did not in any way suggest political domination by the Russian Empire over other Slavic realms or areas, but instead, they applied the idea in depicting Russia as the older brother, the one with the responsibility of giving a good example among the “brethren of Slavs” (Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 12) and “our Balkan co-believers” (Podvig russkago generala 1877, 10). In the “Slavic War for Independence,” the author announces, “Rus’, you, powerful, wide, hospitable, to you belongs the right of seniority. For the time being, be an example to your brothers in your steadfastness and composure. Hold the sign of Slavism, let it be seen by all the scattered Slavs” (Slavianskaia voina za nezavisimost’ 1876, 6).

Ethnographic descriptions and attributes of Slavic groups as such are quite scarce in the booklets. They are represented together and separately primarily through their innocence and suffering under the Turkish reign. Some features are, nevertheless, mentioned. For instance, the bravery, simple-heartedness, and friendliness of Serbs and the courage of Montenegrins are explicitly pointed out, as is the hardworking nature of Serbs and Bulgarians (Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 12; Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 13, 27–28, 32). Of the Bulgarians, one author also writes, “their habits have a lot in common with their deadly enemies—the Turks and Greeks. Anyway, the Slavic faith and traditions were preserved among them from the ancient times. This unfortunate Slavic tribe has been suppressed, enslaved, defeated, despite some 7 million inhabitants, the basic features of which are love for the fatherland, for independence, brotherly love to tribesmen, and patriarchality of traditions” (Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 6).

The worldview represented in the popular publications seems, therefore, to include Balkan Slavs loosely into the category of “us” (versus “them”): they are Orthodox Slavic peoples and therefore considered especially close to Russians. Here we might apply—fully aware of certain anachronistic dangers—Thomas Hylland Eriksen’s suggestion concerning anthropological categorization: instead of clear-cut boundaries defining “us” from “them,” some groups can be considered closer to us than the others, “almost like ourselves.” Eriksen calls this approach analogue as opposed to digital, in which categories of otherness are unambiguous and fixed (Eriksen Reference Eriksen2010, 79). In the texts, Russian “brothers” are granted the role of seniority and certain symbolic authority in the family of Slavs, the rest of whom, according to the authors, do not have especially remarkable history, notable historical events or reforms (see Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 6; note that Danilevskii [Reference Danilevskii1995, 22] uses the argument of “a people that does not have a history” to justify the Russian administration in, for example, Finland).

Regarding Muslim or Catholic Slavs, the somewhat troubling issue challenging the religion-based wing of pan-Slavist thinking right from the 1850s (Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2016, 296–328), most of the authors did not mention them. In the binary worldview of the lubok publications, being a Slav was a synonym for confessing the Orthodox faith. However, for instance, in “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence,” it is neutrally noted that even though most Bulgarians are Orthodox, some are Catholic or Muslims; it is also pointed out that already by the 15th century some Bulgarians were converted into Islam. Regarding Croatians, the author of “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence” mentions their Catholic faith, which he actually considers fortunate for them, for they avoided the Muslim dominion (Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 6, 10). It can be assumed that for the ideological message of the publications, which, as I discuss below, was to emphasize the essential juxtaposition of Muslims and Orthodox Slavs, these groups were considered irrelevant and marginal; including them would have confused readers and obscured the black-and-white viewpoint preferred by the authors.

In general, the popular booklets do not bring forth any complexities in the relationships between Russians and their “Slavic brothers,” or problematize the questions concerning the liberation of the Balkan Slavs any further. Instead, the Balkan Slavs are represented solely in the context of their role as Orthodox victims of Ottoman administration and violence, dependent on the assistance of Russians. This lack of any critical analysis of the situation, combined with graphic and emotional descriptions of the problems caused by Ottoman administration, give the booklets a propagandistic rather than discursive or scholarly tone.Footnote 7

Within the category “almost like us,” the Cossacks can also be counted. The author of “The Russo-Turkish War and Peace between Russia and Turkey in 1878” praised them as the pioneers in the fight against the Turks. According to him, the Cossacks fought “a battle not to live, but to die for the Orthodox faith and for the liberation of the Christian prisoners” (Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 36; about the roles and images of Cossacks in the 19th century literary production, see Kornblatt Reference Kornblatt1992, 3–96).

Representations of Turks

Besides the descriptions of the horrors of the Ottoman administration, the propagandistic purposes of authors are most obvious in their representations of the Turks. Instead of explicitly emphasizing the positive features of the Slavs, the negative attributes of Turks were lavishly scorned by the authors. This creates the typical juxtaposition in the formation of collective identities: by describing “them” in pejorative terms, the authors are also implicitly describing the positive qualities of “us”; their own reference group—which, in this case, can be seen to have referred primarily to Russians and secondarily to the “Slavic tribe” in general (see Vuorinen Reference Vuorinen and Vuorinen2012, 1–3; Baár Reference Baár2011, 256–257).

One of the most popular attributes connected to the Turks, used to refer to enemies (vragi), foes (nepriiately) and those of other tribes (inoplemenniki), is fanatism (see Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 36, 49, 60; Slavianskaia voina za nezavisimost’ 1876, “Dlia nachala,” “Ob’iavlenie.”). For instance, one author mentions “Muslim fanaticism and crude Asian fanaticism” (Voina s turkami 1877, 8). Other characteristics used to describe Turks are, for instance, barbarism, faithlessness (nevernost’), belligerence, and wildness (dikost’) (see Malykhin Reference Malykhin1878, 63–64; Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877, 5, 9; Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 64; Russko-turetskaia voina i mir 1878, 4, 7, 9–10; Voina serbov, gertsegovintsev i chernogortsev 1877, 8, 14).

Wildness is sometimes explicitly connected to general disorder in the texts. For instance, in the fictive story “The Salvation of a Christian Woman by Russians” a group of bashibazouks coming to raid a village is described in a way that conveys to the reader an image of a brutal and disorganized group (as an effective contrast to the peaceful village and beautiful maidens preparing for a wedding feast):

From behind the hills came a glimpse of the fur hat of a bashi-buzuk: behind him another one was seen, and a third one, and suddenly on the field appeared thirty horsemen armed from head to foot. Their clothing was very diverse. One had a red blouse, another wore a ripped beshmet, yet another a shirt in tatters; one had on his waist a pair of long pistols, on another protruded a sabre, and everyone had a long spear in their hands. The physiognomy of this irregular Turkish cavalry was wild and sinister.

(Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877, 6–7)In the same booklet, the young Turkish pasha who chooses the Bulgarian maiden as his favorite wife is described as intelligent and having traveled Europe (“his external appearance reminded much of that of a civilized European”); however, as a public servant, he was nevertheless corrupt and expressed other typical vices of Turkish culture and administration (Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877, 20–21). In this particular chapter, the reader might detect traces of warning: according to the author, even the most civilized Turk is nevertheless a Turk, and one should not be deceived by his appearance. The image of western European countries in the texts was not favorable, either, and they were openly blamed for fraternizing with the Turks, as I discuss below. The detail might also be contextualized in the contemporary emergence of Muslim intelligentsia in Russia, which was adding to the concerns of officials and challenging the old stereotypes of stagnancy connected to Islam (Campbell Reference Campbell2015, 71–83).

A notable attribute of the Turks in the texts concerning the war of 1877–78 is their laziness, adding to the idea of a certain disorder and degradation brought on by the enemy in the areas conquered by them. This is explicitly emphasized by numerous authors, contrasting the hard-working nature of the Balkan Slavs, and explaining the decline in the areas governed by the Turks. For instance, the author of “The Russo-Turkish War and Peace between Russia and Turkey in 1878” announces that “facts show us that where Turks are ruling, only laziness and desertion exist, and the occupancy declines and decreases; vice versa, when Christian population increases. Wherever a Mohammedan Turk is governing, wonderful and fertile lands turn into deserts, blooming villages vanish without a trace, people become impoverished and turn from permanent dwellers into half-wild nomads” (Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 13).

The author of “The War of Serbs, Herzegovinians and Montenegrins, or the Battle of Slavs with Turks” concludes that Turks are “lazy, wastrels, and contaminated with all the vices, which in the case of poverty, stick out even stronger and more disgusting” (Voina serbov, gertsegovintsev i chernogortsev Reference Leont’ev1878, 11–12). The author of “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence” notes that “for Turks, it is convenient to govern hard-working Bulgarians, because they themselves are lazy. All this wealth of nature gives nothing to an enslaved Bulgarian, but gives a Turk even more possibilities to enjoy his laziness and his beastly life, and to spend his life in idleness” (Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1878, 13–14; see also Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 7–8; Voina russkikh s turkami 1877, 13–14, 21; Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877, 26).

Some authors also compare not just Turks and Slavs, but Islam and Christianity; for instance, the writer of “The War of Russians with Turks” announces that “thus began the perverted connection of Russian people with Mohammedanism, progress with stagnation, freedom with slavery; because from the very kernel of the teachings of Islam derives the sprout of all that resents the spiritual development of a human being, defining his life once and for all by setting rules and borders. Whoever compares the teachings of Christianity with Mohammedanism well knows and understands this” (Voina russkikh s turkami 1877, 7–8).

Likewise, the author of “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence” begins his work by explaining, how, “according to the teachings of Mohammed only those who live according to Muslim religion belong to that society and are entitled to its rights; the rest are not considered any more or less than despicable giauras and slaves. They are enemies of the prophet, in the power of whom, according to teachings of whom, it is allowed to destroy them with fire and sword” (Voina serbov, gertsegovintsev i chernogortsev 1877, 1; see also Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 6. Giaura is a word that, according to the writers, refers to a dog and which Turks used for Christians).

One of the causes, as well as an indicator, of Turkish decline and decadence deriving from the teachings of Islam was, according to some authors, “harem life,” creating a juxtaposition for implicitly referring to the moral superiority of Orthodox Christian Slavs (see Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 19, 27). In “The Salvation of a Christian Woman by Russians,” the author brings his Bulgarian heroine into a Turkish seraglio, letting her notice the apathetic looks of the numerous wives of the pasha. The author ponders, “Polygamy, or a man having many wives, degraded the Eastern woman on the grade of the animal kingdom—In Mohammedan seraglio … because of the deterioration and slackening of the mind, develops a passion for charade and fawn, lies and wild jealousy, and therefore nowhere grows such secret intrigue than in the seraglic life of any Muslim” (Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877, 16–17, 18–20).

Practically all of the conceptions and ideas described above underline the dualistic contrast of innocent Orthodox believers and the wild Muslims harassing them. Since the medieval chronicle texts, this had been the basic template for representing the relationship between Orthodox Christians and their enemies. Moreover, the descriptions implicitly reflect the medieval idea of Christian divine order and devil-inspired disorder (see Lotman and Uspenskij Reference Lotman Ju, Uspenskij and Shukman1984, 4–11). The authors emphasized this idea by depicting the contemporary conflict as a part of a historical continuum, as noted above.

Following Eriksen’s ideas of categories of others (see the previous section), the image of Muslims in the texts—historically mostly represented by Tatars and Turks—seems to be very “digital”, that is, with no shades or nuances in the representation, and no suggestion of compromises (in reality, though, the relations between diverse groups, let alone individuals, have been diverse and multifaceted [Eriksen Reference Eriksen2010, 79; Crews Reference Crews2006, 4–5; Cross Reference Cross, Franklin and Widdis2004, 75]). Religion has traditionally been depicted as the dividing line in conflicts between Russians and their antagonists, and so it continues to be in these publications (see Lotman and Uspenskij Reference Lotman Ju, Uspenskij and Shukman1984, 3–28; Parppei Reference Parppei2019, 149–151, 160–162).

Moreover, the depictions of Turks in the popular booklets are woven from negative features of universal enemy images, with the reverse side consisting of the good qualities of “us.” As Marja Vuorinen has put it, “Goodness, honesty, righteousness, purity, proper manners, hard work, right religion, high but not over-ripe culture and decency are the hallmarks of the Self, while the Other is accused of being evil, untruthful, crooked, impure, ill-mannered, lazy, superstitious, barbaric or decadent, and immoral” (Vuorinen Reference Vuorinen and Vuorinen2012, 2).

The essential dualism of the situation is a typical feature of war propaganda, distributed by mass media. If we assume that the target audience for the popular publications concerning the Russo-Turkish War included those potentially taking part in military actions, the polarized imagery served as legitimation of getting involved in the war in the faraway Balkans. Fighting such a despicable enemy was represented as a rational and humane thing to do (Vuorinen Reference Vuorinen and Vuorinen2012, 4). Legitimizing the military involvement was important for Russian society in general, both in anticipation of potential losses and for raising funds. This legitimization is what these booklets earnestly offered.

The relationships with Muslims were acute for Russia and Russians in the context of the imperial expansion in the Caucasus and in Central Asia; for instance, in 1877, simultaneously with the Russo-Turkish War, the empire had to face yet another rebellion in the Eastern Caucasus. In the annexed areas, Russian officials faced the challenge of assimilating the resident Muslim minorities. However, the religious and cultural differences between civilized Russians and savage, fanatical Muslims—note the similarity of the concepts with the lubok rhetoric—were often considered difficult or even impossible to overcome (see Jersild Reference Jersild, Brower and Lazzerini2001, 101–111; Brower Reference Brower, Brower and Lazzerini2001; Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2011, 269–270; see also Crews Reference Crews2006, 241–292, 354–358). Also, the Tatars of Crimea and the Volga region were treated with suspicion by officials—especially in times of war—when it came to their loyalty to the Russian Empire. One of the worries was apostasy: baptized Tatars (re)joining the Muslim community, and another was so-called Islamicization or Tatarization as a force competing with Russification in non-Orthodox areas. Accusations of “fanaticism” of Muslims were formulated in this context, too (Campbell Reference Campbell2015, 21–53, 63–71).

The depictions of Turks and Muslims reflected and reproduced the discourse and dilemmas concerning the challenges of a multi-ethnic empire. The multifaceted Islamic “other” was externalized and simplified to serve the purpose of wartime propaganda, but at the same time the depictions served internal religious-political purposes, which may have included informing the reading public of the dangers represented by Islam and Muslims in general. For all of these purposes, representing Muslims as a homogenous, stereotypical group, despite their ethnic and doctrinal diversities, was the most efficient and effective option.

Other Non-Slavs in the Texts

Of other ethnic groups, Jews are mentioned in “The Salvation of a Christian Woman by Russians,” in which they are depicted as slave traders; or to be exact, the traders are described to “look like Jews,” which in itself undoubtedly evoked certain imagery and connotations in the contemporary readers’ minds (Spasenie russkimi khristianki 1877, 10; about the discourse on Jews in Russia, see Klier Reference Klier and Branch2009, 299–311). In “The War of Serbs, Herzegovinians and Montenegrins, or Battle of Slavs with Turks,” Jews, Greeks, and Armenians—all ethnic or religious “others” in relation to resident Slavic groups and Russians—are mentioned as assistants of the Ottoman administration: “the collectors of taxes, usually chosen from among Greeks, Armenians, and Jews, acted as they wished” (Voina serbov, gertsegovintsev i chernogortsev 1877, 12).

As an ethnic group, Greeks in general are viewed with some ambivalence in the publications: most importantly, they are Orthodox, like Russians, and they had, in their turn, fought in a “heroic war for freedom and nationality [narodnost’]” against Turks in the 1820s, thus bringing hope for Balkan Slavs (Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 43; see also Voina russkikh s turkami 1877, 25–26; Voina s turkami 1877, 23). It is also appreciated that Greeks produced “an amazing metamorphosis” in the areas previously governed by Turks, by developing their villages in earnest, whereas the neighboring Turkish villages are represented as declining due to the laziness and indifference of their inhabitants (Voina s turkami 1877, 23–25).

On the other hand, together with the Turks they are called the Bulgarians’ “deadly enemies” by the author of “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence”: “also Greeks, brothers in faith, can be counted the suppressors of Bulgarians along with the Turks” (Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 6–7). The author further analyzes the issue from the historical viewpoint:

Brothers in faith, oppressed by new misfortunes and persecution, it would look like Slavs, represented by Serbs and Bulgarians, would have befriended with Greeks, for both were equally enslaved, but that was not the case; the Slavs could not act in unison against their common enemy, because the most important spiritual [Greek] figures, who had influence on believers, found it convenient for themselves to fawn the Sultan with various means, and therefore the main figures among Greeks in Constantinople deserved the goodwill of the Sultan, and profited from numerous benefits… The patriarchs and the most prominent figures of the Greeks fawned and conformed with the Turks, assuring them that they themselves hate the restless Slavs. (Voina serbov i chernogortsev 1877, 9–10).

Greeks, therefore, seem to be located somewhere between Balkan Slavs and Turks in the categorization of “them” in the texts. However, while most of the authors treat the Greeks quite neutrally, some of the texts reveal echoes of the discourse that took place from 1858 to 1860, when Bulgarian nationalists, in addition to the Muslims, began to represent the Greeks as the enemy of their country and people. The underlying issue was the struggle of the Bulgarians to form an ecclesiastic organization, independent or at least autonomous of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The author of “The War of Serbs and Montenegrins (Slavs) with Turkey for Independence” apparently repeats the claims adopted by numerous pan-Slavistic authors in Russia at the end of the 1850s; however, those claims were quickly criticized by writers who were emphasizing the importance of Orthodox unity rather than any ethno-nationalist goals in the Balkans. Moreover, Russian censorship had put an end to the anti-Greek press campaign at the request of the Patriarchate of Constantinople (Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2016, 93–105).

Russia and Western Europe

Yet another crucial actor in the military-historical theater of the Balkans, as presented by the authors of the popular publications, were so-called Western countries, referring to European nations with interests in the area. Their role in the events was intertwined with that of Russia, forming yet another clear juxtaposition. Initially, the distress of the Balkan Christians had drawn the attention of European powers, but once the collective negotiations with the Ottoman leadership failed, Russia alone ended up declaring the war on Turkey, to strengthen the empire’s political and military status and its influence in the area. This decision gave the authors of popular publications good reason to emphasize the exceptional morality of Russia (see, for example, Vovchenko Reference Vovchenko2016, 197–200).

For instance, Suvorov compared the choice of Russians to the choice of the Serbian prince Lazar prior to the battle at Kosovo Field in 1389. According to legend, the prince, who was killed by the Turks in the battle, was asked whether he wanted to gain an earthly or heavenly kingdom. According to Suvorov, Russia, as personified by Prince Lazar, chose the latter and thus accepted a heavy responsibility:

With the power of historical events, the Russian people were placed in a special position compared to other realms of Europe in relation to the Turks. Its historical fate defined it alone to be the warrior and protector of Christianity against the spreading of Mohammedanism, the protector of the just cause and the rebuilder of the freedom of the enslaved, the one who returns to the human being his trampled rights, and establishes the progress and development of humankind.

(Suvorov Reference Suvorov1877, 19)This ethos and emphasis on Russia’s exclusive role was further underlined by describing the indifference shown by Western European nations toward the sufferings of Balkan Slavs. For instance, the author of “The War with the Turks” took a firm stand on the issue: “The unfortunate Christians in vain searched for protection from the Western peoples, but none of them had interest in defending the oppressed, when instead of improving their position they only had the preservation of the integrity of the Ottoman Empire on their mind” (Voina s turkami 1877, 20). Further, he spared no words in counting the wrongdoings of each country concerning the contemporary situation in the Balkans:

When the Russian tsar valiantly persuaded the Port to grant the complete enforcement of that which he considers the right of Eastern Christians, at the same time England, so actively supporting the spreading of Christianity in the Far East, destroying the slave trade in Zanzibar not so long ago, stands on the side of Mohammedans in the fight against Christianity and cold-bloodedly watches the situation of Christians, which only barely differs from that of African slaves; France—that privileged country of liberalism and humanitarian ideas—supports through its publishers the preserving of disgusting habits on the Balkan Peninsula; Austria-Hungary wavers between the wish to grab its Slavic neighborhood and the fear that such grabbing would involve deadly poison, and Hungarian students openly say that Turkish Slavs should not be granted independence, forgetting, that thirty years ago their fathers courageously defended the independence of the fatherland; and Germany, like the rest of them, did not show such humanly love and pity toward a Christian of Turkey, as might have been expected from a country which leads European culture.

(Voina s turkami 1877, 27)The author of “The Russo-Turkish War and Peace of Russia with Turkey in 1878” ironically pointed out that when it came to Serbs, “until now, the defeated tribe had had not many friends in the civilized and enlightened Europe,” and emphasized that the war of Russians with the Turks had a “highly humane character, and did not aim to any acquisitions of land, as they were guessing in the West, but to improvement of the life and situation of Christians, still governed by Turkey” (Russko-turetskaia voina i mir Reference Leont’ev1878, 46).

The image of the Russian Empire alone defending a righteous cause for noble reasons was by no means a novelty. During and right after the Napoleonic Wars the Russian idea of certain exceptionalism had been formulated and the idea of Russia as the lonely savior of Europe brought forth. This concept was intertwined with the question of Russia’s geopolitical position between Europe and Asia, which also grew more acute in the Russian discourse after 1812. The idea of morally superior Russia was adapted and applied to the Balkan campaign, combined with the long-established idea of the historical resistance of Orthodox Russia toward Islam (see Carleton Reference Carleton2017, 41–79). While Napoleon’s campaign to Russia inspired contemporary authors to express their disappointment with France and French culture, the events in the Balkans were interpreted in the light of the indifference of the hypocritical “West”—mockingly called “civilized” and “enlightened”—toward the sufferings of peoples ruled by Ottoman administration. Not surprisingly, bitter announcements concerning the untrustworthiness of the western European countries had been made after crucial losses in the Crimean War, the result of which was the defeat and humiliation of Russia (see Garianov Reference Garianov1855). The issue also reflected the ongoing dispute and discourse concerning Russia’s role and “national identity” in relation to the rest of Europe.Footnote 8

Conclusion

The popular publications examined here were, with some exceptions, written by anonymous authors, and without doubt, they were aimed at a wide audience of ordinary readers, probably including soldiers, or potential soldiers, and other people potentially supporting the cause. Due to the censoring process, it is also safe to assume the publications did not include material that the administrative circles of the Russian Empire would have considered improper and not safe to be published and distributed. Therefore, the popular booklets offer a valuable possibility to study the images and ideas conveyed to ordinary Russians about the events in the Balkans.

The booklets can be examined from the same viewpoint as the contemporary lubok pictures, only the textual form gave the authors more freedom for depicting the events’ historical background and political context. Like the popular pictorial depictions, the booklets transmitted to the audience a very simplified and dichotomous imagery of the complicated process of events and causalities that had been unraveling in the Balkans.

The contemporary conflict was represented primarily as a part of a historical continuum of the competition between Christianity—and more explicitly, Orthodox Christianity—and Islam. According to the writers, Russians had been pioneers in this ongoing battle. By the 1870s, a Russian national narrative, with celebrated military events, such as the Battle of Kulikovo, was familiar to a large number of people. In the booklets, the historical “archenemies,” such as Tatars, were replaced by contemporary Islamic antagonists. Mentally connecting Russian national history and the national narrative to the contemporary events in the Balkans was an effective and persuasive tool to justify the importance of the involvement of Russians in the military conflict—more effective than explaining the realpolitik and Russia’s political and economic interests in the area in the light of more recent events.

Another way to persuade the reader to support the campaign was to vividly describe the alleged horrors Balkan Slavs had to endure under Ottoman administration and arbitrary rule. These depictions were intertwined with dualistic representations of ethnic groups involved. The features of Orthodox Slavs, according to the authors, included diligence, friendliness, courage, and love for the fatherland. Turks were represented as lazy, prone to idleness, uncivilized, and immoral; these features were, according to the authors, caused or fed by their Islamic faith. The result was a very stereotypical and propagandistic image of the enemy. The juxtaposition was thus created to feed the motivation of readers to defend the righteous cause by either joining the troops or supporting it on the home front.

At the same time, the relations between diverse Slavic groups were not problematized any further in the material; instead, the issue was represented in a straightforward and simplified way, appealing to readers’ emotions rather than their reason. By avoiding discussing future scenarios or recent historical and political developments affecting Russia’s interests in the area, the authors lifted Russia’s campaign in the Balkans above realpolitik, to the sphere of religious-national mythmaking and propaganda toned with pan-Slavistic ideas.

Through their pejorative depictions of Muslims, the booklets implicitly took a stand in the contemporary discourse on Islam inside the Russian Empire, in the annexed areas of the Caucasus and Central Asia, and in the areas inhabited by the Tatars, such as Crimea and the Volga region. The black-and-white contrasts served these purposes and as wartime propaganda, representing Islam and Muslims as essentially suspicious and morally inferior compared to Orthodox Christianity and its practitioners.

Yet another juxtaposition was created in the context of European countries: the authors represented Russia as the only selfless actor dealing with Turkey. Any political interests of the Russian Empire in the Balkans and Black Sea region were ignored, and Russia’s motives for helping the Slavs were presented as purely humane. This attribution of motives, emphasizing the lonely task of Russia and to some extent echoing the context of the Napoleonic Wars, further persuaded readers to support the righteous cause militarily, financially, or in spirit.

Despite minor differences in emphasis, the sample of popular publications examined here are quite homogeneous when it comes to the issues and approaches the authors and publishers wanted to share with their readers. In other words, whichever of these booklets was bought and read by an individual reader, the imagery conveyed concerning the events in the Balkans was relatively consistent. While we cannot examine the exact reception of that imagery among contemporary readers, we can assume that the material did affect the conceptions and ideas they had about what was going on in the Balkans and about Russia’s role in the events.

Further, I suggest the popular publications contributed to a certain generalization of the discourse concerning the historical and geopolitical role and place of Russia, which had been formed in the context of national history writing and military events—especially such as Napoleon’s campaign and the Crimean War—during the 19th century. Dealings with Turkey and the Balkan Slavs formed an important layer in the multifaceted discourse that has been intertwined with the national narrative of Russia all the way to the present, with certain features—such as echoes of pan-Slavistic ideas, questions of Russian-ness in ethnic and religious contexts, and the idea of Russia as a non-aggressive nation suffering from discrimination by “Western countries”—popping up in various contexts.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland under Academy Research Fellow Grant number 298805.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.