Introduction

Today, a large portion of Upper Silesia is in Poland and (along with the rest of the state) has seen the transformation of the political system in the Republic of Poland. This transformation took place in 1989, which also marks the rise of the modern Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement. The organizations comprising the movement were initially established mostly as associations and foundations, and then shifted to the goal of representing the political interests of Upper Silesian society. Since 2002, organizations engaged in the movement have taken part in regional and statewide elections. In 2004, Ruch Autonomii Śląska (hereafter RAŚ; Silesian Autonomy Movement) has become a member party of the European Free Alliance. In its early years (2002–2018), the association created electoral committees of voters for elections. As RAŚ took part in most of the elections during this period, repeating platforms across elections and running candidates, it can be classified as a proto-party. In 2018, Śląska Partia Regionalna (hereafter ŚPR; Silesian Regional Party) and Ślonzki Razem (hereafter ŚR; Silesians Together) officially registered as political parties.

The Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement has been studied mostly in Polish scholarly literature. The social science works of Sekuła (Reference Sekuła2009), Sołdra-Gwiżdż (Reference Sołdra-Gwiżdż2010), and Wódz and Wódz (Reference Wódz, Wódz and Nijakowski2004), as well as the cultural studies by Gerlich (Reference Gerlich2010), Kamusella (Reference Kamusella2007), and Szmeja (Reference Szmeja2017), are the most well-known. Muś (Reference Muś2019), Myśliwiec (Reference Myśliwiec2013), and Trosiak (Reference Trosiak2016) are among the few political science scholars who have shown interest in the topic. Although scholars have studied the tension between ethnicity and politics, especially among the political behaviors of Upper Silesian society, the question remains: How has Silesian ethnic identity become politicized?

The role of ethnicity in the creation of political interest groups and, consequently, possible political opposition toward the state policy has been extensively studied from two main approaches: Lijphart’s consociationalism (Reference Lijphart1977) and Horowitz’s theory of conflict (Reference Horowitz1985). Lake and Rothchild (Reference Lake and Rothchild1996), Gurr (Reference Gurr and Gurr2000), and Cordell and Wolff (Reference Cordell, Wolff, Karl and Stefan2010) studied these topics later. Studies show that, especially in times of political change or distress (in the case of Upper Silesia, during the interwar period and after 1989), people tend to organize themselves in groups based on ethnicity, which then become oppositional in political conflict. It is then hard to undoubtedly categorize this as a conflict over identity or resources, such as power (Wolff Reference Wolff2006). Still, protagonists of the respective groups invoke ethnic identity and its elements to demand rights for their group and, at the same time, to consolidate the group (Petsinis Reference Petsinis and Makarychev2020). Especially in the case of nondominant groups, demands are based on distinguishing characteristics of the ethnic group and a cultural security dilemma, which leads to the need for protection for the nondominant (minority) culture (Marko Reference Marko and Coradetti2012).

If regionalist demands are raised as well, the movement can be categorized as ethnoregionalist, and, indeed, in Europe usually this is the case. Ethnoregionalists focus on strengthening the population of the region vis-à-vis the population of the state as the whole. They usually focus on the territorial dimension as well as the (distinguishing) characteristics of the population, which may be of cultural or socioeconomic character (Heinisch, Massetti, and Mazzoleni Reference Heinisch, Massetti, Mazzoleni, Heinisch, Reinhard, Mazzoleni, Massetti and Mazzoleni2019). In the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement, we can find all three focus points: territory, ethnicity, and socioeconomic specificities (Solska Reference Solska, Heinisch, Massetti and Mazzoleni2019).

The first goal of this article is to identify the elements that are considered particular to and essential for Silesian society. The next goal is to study the ways they are exploited to appeal to an ethnic group and how they distinguish that group in the regional political sphere. James Fearon’s theory inspired this approach: “Ethnicity is socially relevant when people notice and condition their actions on ethnic distinctions in everyday life. Ethnicity is politicized when political coalitions are organized along ethnic lines, or when access to political or economic benefits depends on ethnicity” (Fearon Reference Fearon, Wittman and Weingast2006, 853). Politicization in this article has two closely related meanings. First, it is a process in which ethnicity influences the political process (decision making, law making, campaigns, and elections) and a process in which the political process (mostly campaigns and political programs) influences ethnicity. Second, it is a process in which the political coalitions and voters align along ethnic lines. The units of analysis in this study are activities of organizations classified as active in the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement that identify as representatives of the Silesian ethnic group and that engage in political behaviors.

In some cases, another question becomes relevant: To what extent are the elements of the modern Silesian ethnic identity influenced by the protagonists within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement? Ethnic identity, for the purpose of this study, is understood as individual identification with a certain ethnic group based on some objective criteria, such as culture, presumed ancestry, or national origin (Yang Reference Yang2000, 40).

The hypothesis of this article is that the elements of modern Silesian ethnic identity, which are perceived as important among Silesians, and the activities of organizations constituting the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement are closely related. More specifically, the organizations within the movement exploit existing conditions, recreate them, and come up with a narrative that emphasizes opposition toward majority and centralized political groups.

Study

This study was conducted using the Sequential Mixed Approach Design. First, the researcher applied a qualitative method, focus group interviews, using a unified scenario. The study examined members of the chosen organizations belonging to the Upper Silesia Council (umbrella organization, which gathers organizations and can be classified as ethnoregionalist). The researcher interviewed six organizations (5–10 interlocutors in each): Fundacja “Silesia” (April 11, 2018); Niemiecka Wspólnota “Przyszłość i Pojednanie” (March 9, 2018); Pro Loquela Silesiana (April 3, 2018); Ruch Autonomii Śląska (November 20, 2017); Ślōnskŏ Ferajna (June 28, 2018); Związek Górnośląski (October 10, 2017). Due to an agreement between the researcher and interlocutors, quotations by respondents are anonymous.

Later, the researcher applied a quantitative method: a survey questionnaire. This method measured the popularity of the views of the members of the chosen organizations among the inhabitants of Upper Silesia. The number of questionnaires administered corresponded to the population of districts. The questionnaire sample was chosen based on the nonprobability, stratified sampling method (based on the population ratios between the chosen districts and on quotas, such as gender and age). This approach enabled the researcher to select a sample that meets the requirement of typological representativeness.Footnote 1

The study results singled out seven elements of Silesian identity (based on their popularity and their relation to auto-identification). The most important elements of Silesian identity are presented differently by ethnoregionalist organizations and respondents in the quantitative study. On the one hand, the members of ethnoregionalist organizations stressed the role of language, territorial bond, customs and traditions, and collective memory distinctive from the history known to the dominant culture. On the other hand,the respondents in the quantitative study emphasized: categorization of Silesians as a group, familial bond to the region, the declared role of the region in the respondents’ lives, and customs and traditions.

Next, I examined programs and activities of ethnoregionalist organizations by looking at the presentations of these elements and the roles they play in society. This part of the study was based on a content analysis of written programs, websites, and articles in the newspapers published by the organizations studied here. All translations, data and calculations are mine.

Elements Chosen by the Members of Ethnoregionalist Organizations and Ways of Their Politicization

Language

A different language from that of the majority population is perceived as one of the main indicators of the existence of a separate ethnic group. Displaying distinctive linguistic characteristics also is suggested in many definitions of the term national minority, which was created in the works of United Nations (Capotorti Reference Capotorti1977, 96; Chernichenko Reference Chernichenko1997) and the Council of Europe (Parliamentary Assembly CoE, 1993).

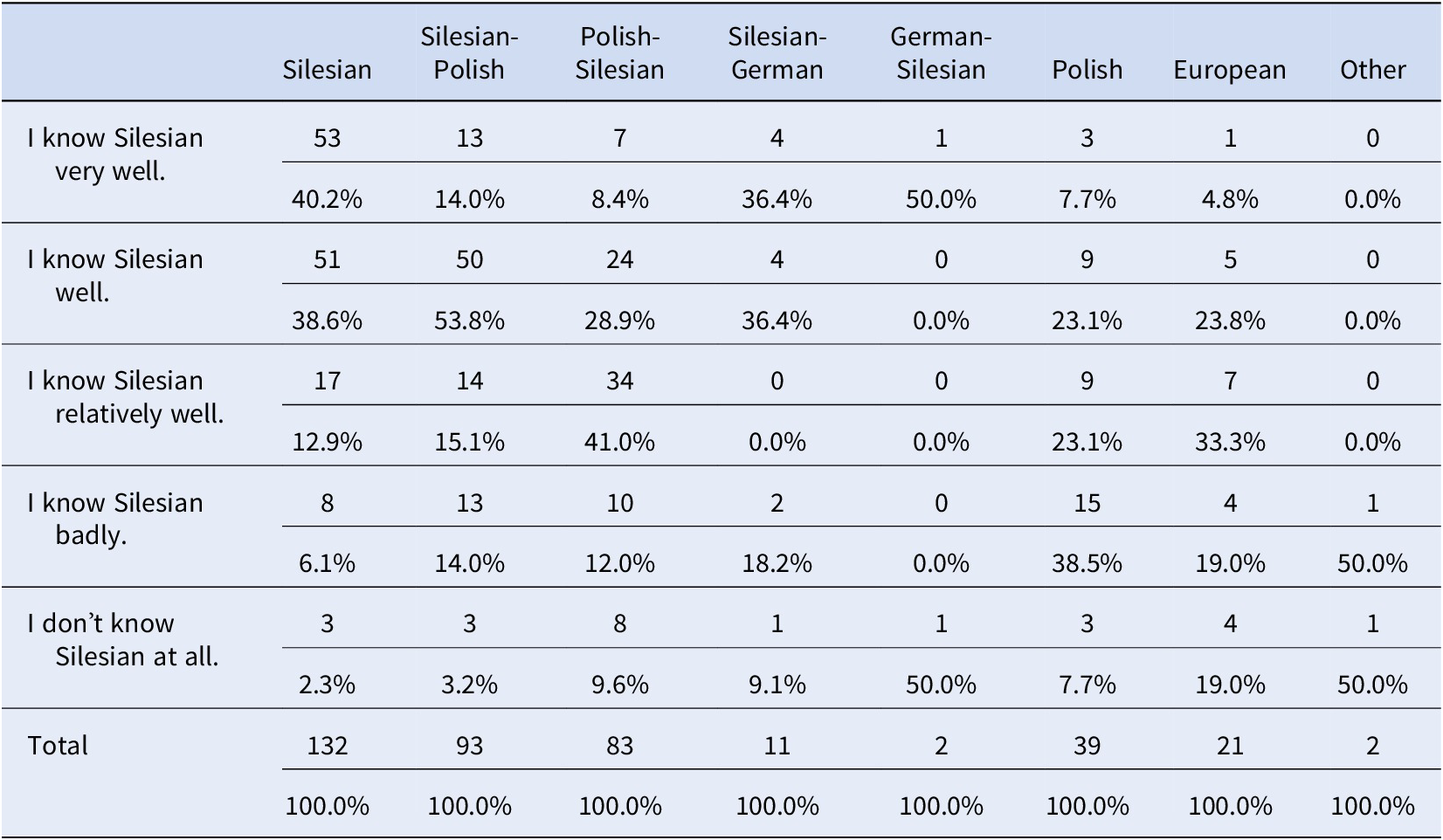

For members of the studied organizations, in most cases, Silesian is seen as a separate language; for others it is a dialect of the Polish language. About 21% (21.4%) of respondents to the second part of the study said they know the language very well, 37.2% well, 21.4% relatively well, 13.8% poorly, and 6.2% not at all (table 1). Furthermore, using V-Cramer Correlation in SPSS, the results established a correlation between auto-identification and knowledge of Silesian language (table 2). The crosstab suggests that this correlation is a positive one: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that a respondent knows the Silesian language (table 3).

Table 1. Silesian language knowledge

Note: n=384.

Table 2. Correlation. Auto-identification and knowledge of language

Table 3. CrossTable. Auto-identification and knowledge of language

Politically, Silesian language became important on at least two levels. In October 2010, a group of parliament members (including Marek Plura, a Silesian himself) presented a legislative initiative to modify the National and Ethnic Minorities and Regional Language Act of January 6, 2005, by adding Silesian as a regional language (Polish Sejm 2011). But it failed. On August 27, 2014, a citizens’ legislative initiative on the modification of the same Act was presented to the Sejm. This initiative would codify recognition of the Silesian ethnic minority and the Silesian language as a minority language (Polish Sejm, n.d). The initiative was prepared by organizations belonging to the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement, including RAŚ. This initiative failed as well. Furthermore, during the election campaign for elections to self-government bodies (Sejmik Województwa Śląskiego) in Poland in 2018, two ethnoregionalist parties, ŚPR and ŚR, called for the preservation and recognition of Silesian language. In the program of ŚPR, one of the main points, identity, included preservation and codification of the Silesian language. The program of ŚR popularized the Silesian language and stressed the role of teaching it at schools (Ślonzoki Razem, “Nasze cele polityczne,” n.d.).

To summarize, the recognition of the Silesian language is the most important policy demand to the state by the Silesians. However, this demand also plays a role in regional politics, as it has become one of the programs of ethnoregionalist parties.

Territorial Bond to the Region

The connection to the region in the case of Upper Silesians relates to tangible and spiritual realities. In the case of the former, it suggests a connection to the territory. Connection to the region can be forged in different ways, but mostly by being born there or by living there. As to the spiritual bond, it refers to genius loci of the region: the bond to territory means accepting and understanding its heritage and collective memory of its inhabitants as well as particular characteristics of the community living there and its relation to the region.

This kind of connection was described by one of the interlocutors in the qualitative study: “Silesian patriotism is space-related patriotism rather than blood-related patriotism. The patriotism of ‘Heimat’ [Motherland].”

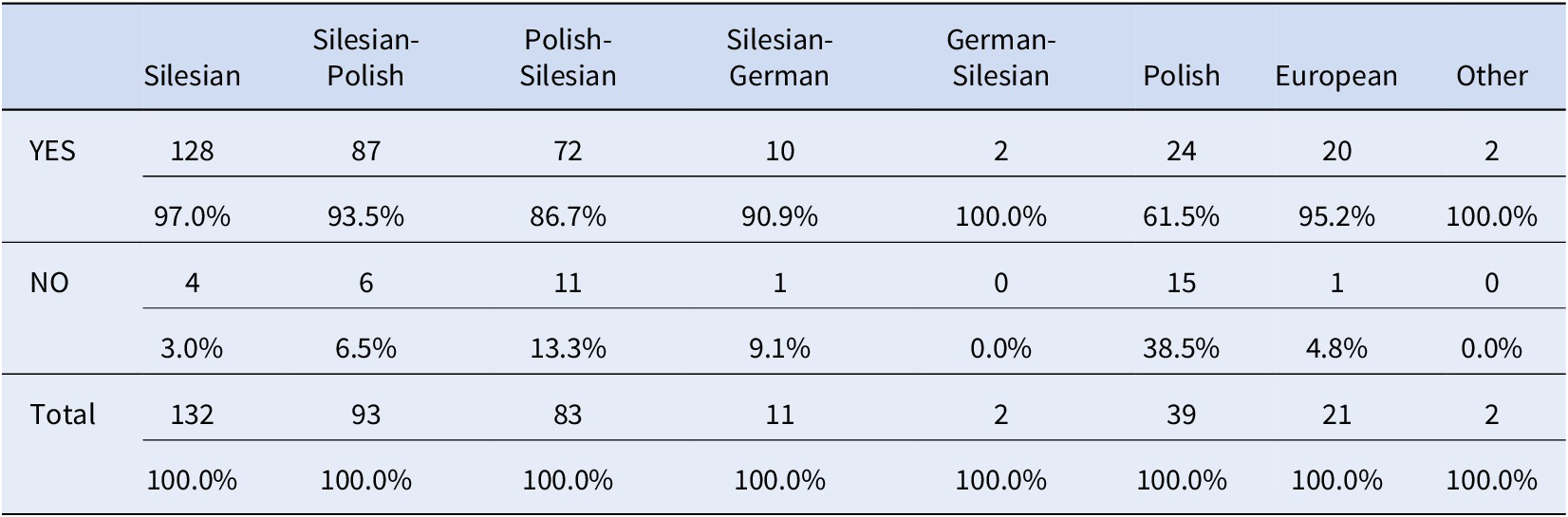

Most members of the studied organizations agree. Respondents in the second part of the study lived in the Silesia region. The question was posed whether they were born there as well. The study has shown that 90.1% of respondents were born there as well, while 9.9% were not (table 4). Furthermore, the V-Cramer Correlation in SPSS established a correlation between auto-identification and being born in Silesia (table 5). The crosstab suggests that this correlation is a positive one: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that a respondent was born in Silesia (table 6).

Table 4. Ties (territorial) to the region

Table 5. Correlation. Auto-identification and territorial and familial bonds

Table 6. CrossTable. Auto-identification and I was born in Silesia

This space-related patriotism is used in different ways in politics. It is a more inclusive definition of Silesian identity, as it is used to widen membership and support. Second, ŚPR especially stressed that decisions about the region should be made in the region (Śląska Partia Regionalna 2018a). Third, ŚR emphasized that its leaders were born and lived their whole lives in the region (Ślonzoki Razem, “Nasze cele polityczne,” n.d.). These emphases suggest they know the region and its inhabitants, along with their needs; this kind of native leadership has already been recognized as typical for ethnoregionalist parties (Winter Reference de Winter, de Winter and Türsan1998, 222). Fourth, the program of ŚPR made revitalization of the city centers and cultural heritage (mostly postindustrial buildings) one of its main political goals (Śląska Partia Regionalna 2018b).

Territorial bond to the region is one of the main components of so-called Silesianism, the set of characteristics typical for members of the Silesian ethnic group. It is also a reason for its relative inclusiveness and plays diverse roles in politics, but mostly it is used to strengthen the support for the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement within its target group, Upper Silesians.

Customs and Traditions

Specific Silesian culture and traditions must be studied in three groups: archaic, historical but current, and new. As examples of archaic traditions, we can list traditional outfits and the greeting Szczęść Boże! (God bless you!), which has its roots among miners but was used quite commonly in the areas where mines were situated. Inhabitants of the Upper Silesian Industrial Area place a high value on the mines. Related to historical, but still observed, traditions, we can list typical, regional festivities: for Christmas Eve 89.8% of respondents still prepare traditional poppy seed bread pudding (makówki); on the first day of a child’s first year of primary school, 91.8% of respondents give their children school cones called tyta; and 92.4% of respondents tell their children that the gifts on the Christmas Eve are brought by Dzieciątko (Baby Jesus). Orlewski (Reference Orlewski2019, 80) also has noted the strong attachment to the typical Silesian traditions. So-called new traditions’ are emerging in the region. For example, July 15, 2011, became the Day of Silesian Flag. Since then, in most Silesian cities, blue-yellow flags are displayed on that day. This day is connected also to the Days of Upper Silesian Self-Government: July 15–17 and the Autonomy March, organized on the first Saturday after or on July 15, if it is Saturday. Furthermore, in 2009, the last Sunday in January became the Day of Commemoration of the Upper Silesian Tragedy. Both new traditions were created as a result of actions of ethnoregionalist organizations, including RAŚ—an ethnoregionalist proto-party—and started to be organized in the 90s.

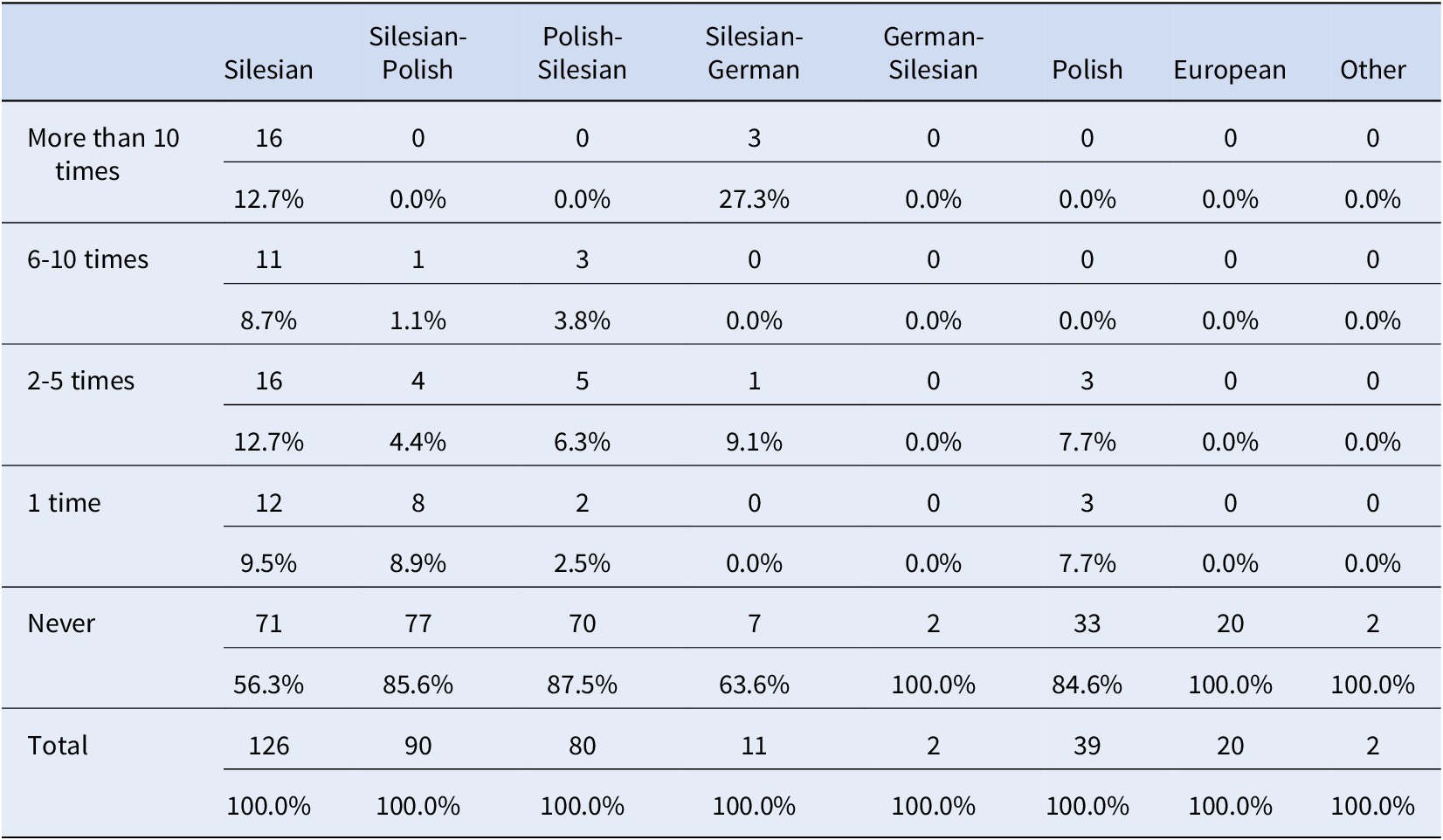

Members of the studied organizations stressed stable religiosity among members of the Upper Silesian community. The region not only has a strong Catholic community but also a Protestant community, mostly the Evangelic Church of Augsburg Confession. Respondents were asked about observance of traditions. For 40.1% of respondents, Silesian traditions are very important, while for 38.5% they are important. Only 17.0% of respondents declared that they are irrelevant and even less said they are unimportant (2.9%) or not important at all (1.5%) (table 7). Additionally, the V-Cramer correlation in SPSS established a correlation between auto-identification and declared observance of traditions (table 8). The crosstab suggests that this correlation is a positive one: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that a respondent believes Silesian traditions are important (table 9). As to the so-called new traditions, most of the respondents do not take part in them (76.3%) while some respondents declare otherwise: one time (6.7%), 2–5 times (7.8%), 6–10 times (4.0%) and more (5.1%) (table 10). Additionally, the V-Cramer correlation in SPSS established a correlation between auto-identification and participation in initiatives organized by ethnoregionalist organizations (table 11). The crosstab suggests this correlation is a positive one as well: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that a respondent participated in initiatives organized by ethnoregionalist organizations (table 12).

Table 7. Attitude toward Silesian traditions

Note: n=382 missing values=2.

Table 8. Correlation. Auto-identification and the role of traditions

Table 9. CrossTable. Auto-identification and attitude toward Silesian traditions

Table 10. Participation in initiatives organized by ethnoregionalist organizations

Note: n=374 missing values=10; n=371 missing values=13.

Table 11. Correlation. Auto-identification and participation in initiatives organized by ethnoregionalist organizations

Table 12. CrossTable. Auto-identification and participation in initiatives organized by ethnoregionalist organizations

The relation of the ethnoregionalist movement to the so-called new traditions have been already established in this research. Still, the old traditions are impacted by the movement as well. For example, while presenting its program in the field of education, ŚPR used the metaphor of tyta (Śląska Partia Regionalna 2018c). Furthermore, for many years RAŚ has given the tyta to children from disadvantaged families as a form of charity (Ruch Autonomi Śląska in Chorzów, “Tyta,” n.d.).

Collective Memory

Collective memory is understood as a narration about the past, a process of reproduction and interpretation (Kansteiner Reference Kansteiner2002, 188). In recent years, the differences between Polish narration about the history of the Upper Silesian region and the narration stemming from the Silesian community itself have gained more scholarly attention (Jaskułowski and Majewski Reference Jaskułowski and Majewski2020). The scholarship speaks about “Silesian harm” (also called “Silesian injustice”), which is described as a feeling of harm, injustice, disappointment, believing to be misunderstood, humiliated and judged due to different cultural and collective memory of the Silesian community (Gerlich Reference Gerlich1994, 5; Wanatowicz Reference Wanatowicz2004, 150; Smolorz Reference Smolorz2012, 118) and can be categorized as a grievance typical for ethnic mobilization. Moreover, Maria Szmeja (Reference Szmeja2017, 175–201) examined the Silesian Uprisings as a case study that shows how the narration in Polish dominant culture differs from the narration of the Silesian community.

In focus group interviews, several differences in the narration about the past can be noted. Many controversies are connected to the fact that during World War II Silesians served mostly in the German Army:

I come to someone’s home, and I see a portrait of a man in a uniform of the Wehrmacht. […] But for us this is something that is ours. And we are not ashamed. And I speak to someone, and he shows me a picture of his grandfather in the Kriegsmarine. If he would show it to a Pole, he would say: “Are you proud that your grandfather was in the German army?” And the answer is no. But they were part of a state; they were citizens of Germany, and they had a duty. And understanding this is something we have in common.

Many families that have lived in the region for generations have the same experience. In numerous cases, their ancestors did not choose to serve in the army but were enrolled and fulfilled their duty.

This problem became part of a wider controversy in Polish public debate. The term grandfather from Wehrmacht became famous in 2005 when Jacek Kurski, a politician from PiS (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość; Law and Justice) said that the grandfather of the presidential candidate from the opposite party, Donald Tusk from the PO (Platforma Obywatelska, Civic Platform), was a soldier in the German army. The man himself came from Kashubia (also called Pomerania). It was meant as an insult, as evidence of the betrayal of the Polish Nation. But the truth has been well known by the inhabitants of Silesia and Kashubia: these lands were incorporated into Germany in 1939, and many of its inhabitants were given German citizenship, which, inevitably, led to enrolment in the army.

The end of World War II brought only new differences. The most vivid example of the opposition between the official state memory policy and the Silesian collective memory was a monument on Wolności Square (Freedom Square) in Katowice. The Monument of Gratitude for the Red Army, the army which took over Silesia in 1945 at the end of the Nazi regime, was erected in 1945. However, many Silesians did not view the period (1945–1950) as a time to be grateful for but rather a time of the Upper Silesian Tragedy, caused partially by the Red Army. The monument was moved in 2014 to the Russian Military Cemetery in Katowice-Brynów. Since then, there is no monument on Wolności Square, but RAŚ promotes the idea of erecting a monument of the Upper Silesian Tragedy in this place, though with scant support of the local authorities. Some politicians, mostly from statewide Polish parties, suggest that a monument of the late US president Ronald Regan should be located there.

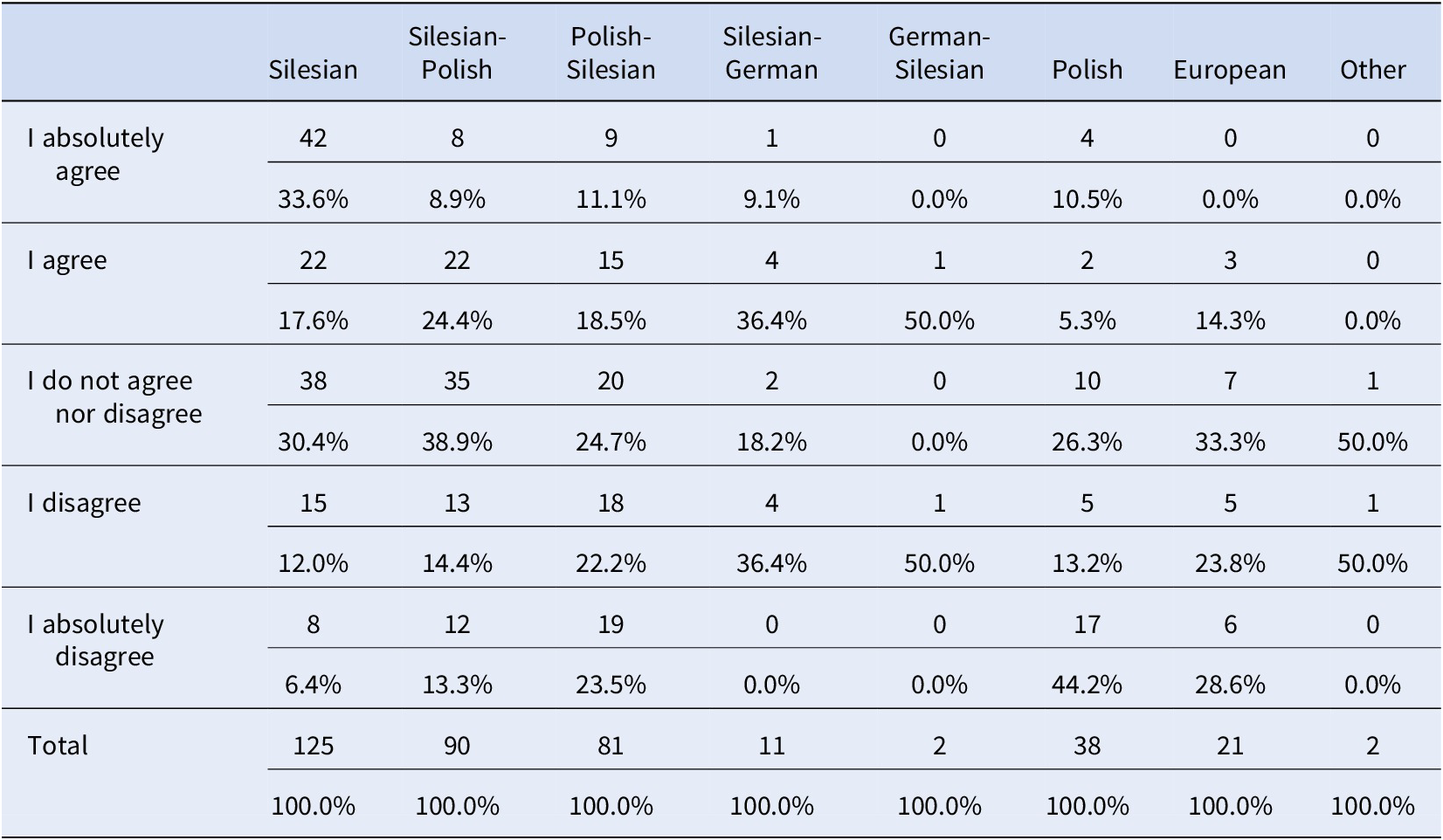

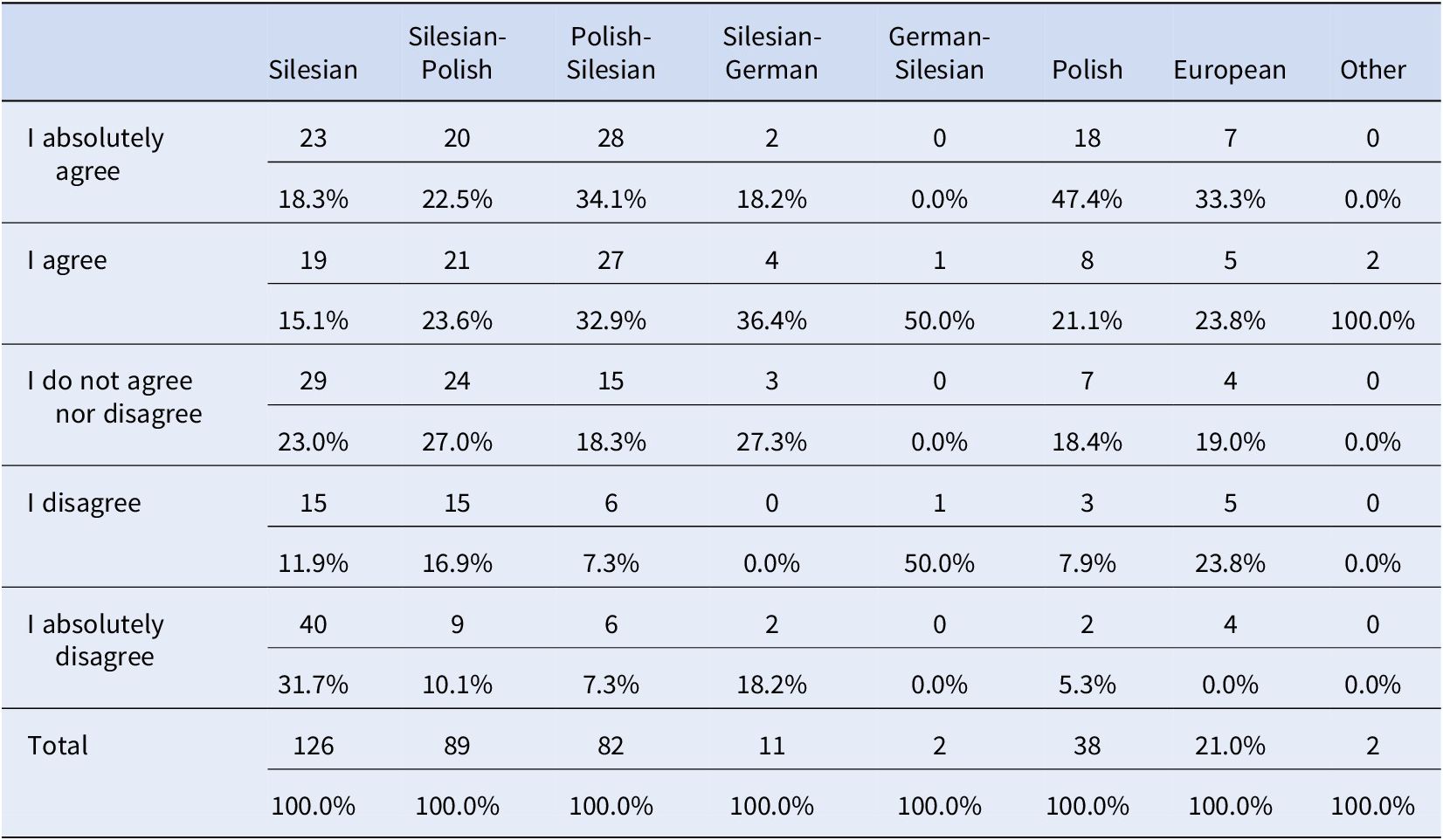

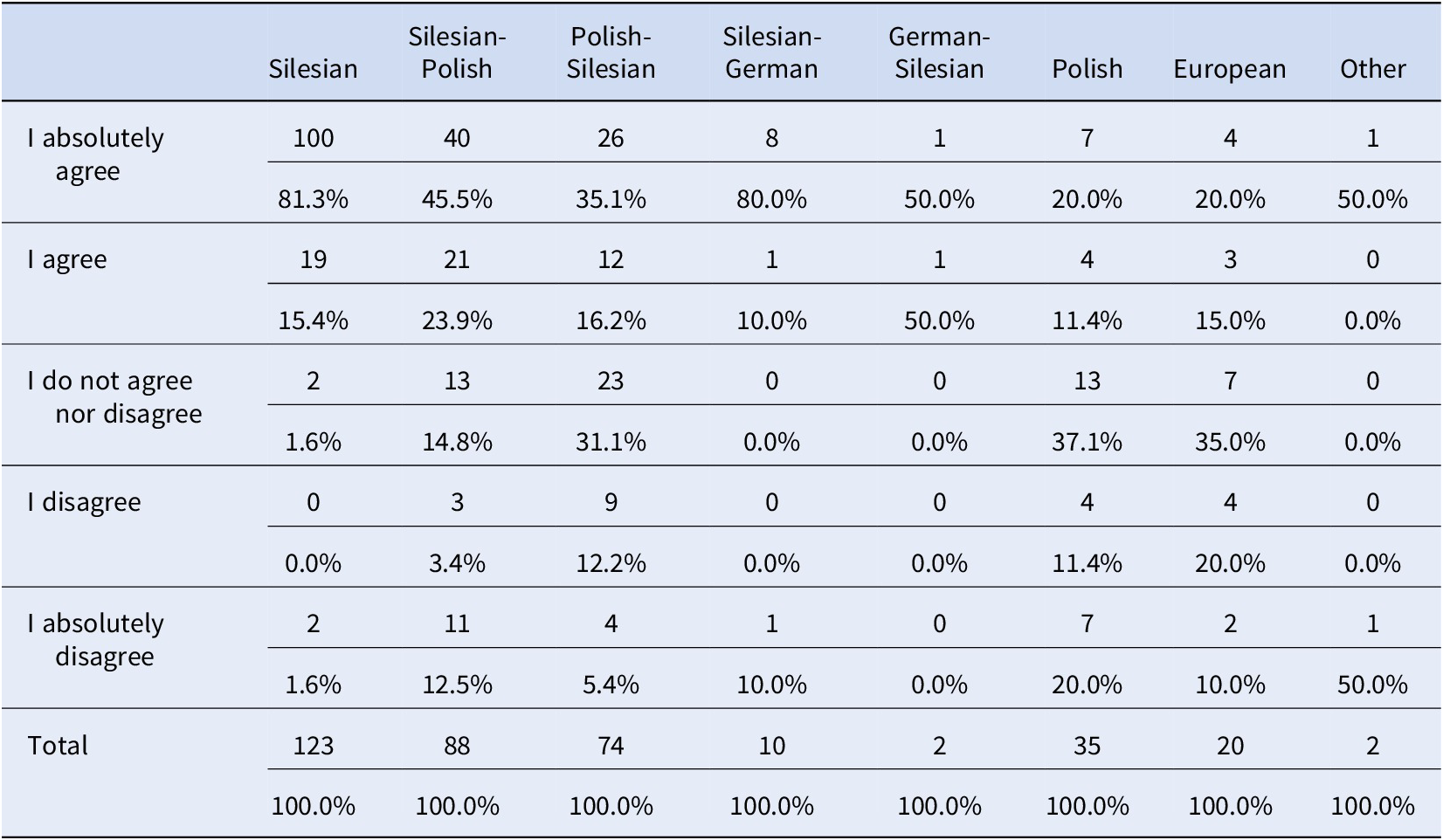

In the quantitative study, it was hard to frame the question that would help discover these differences. In the end, the narration about the so-called Silesian Uprisings, armed conflicts in Upper Silesia between 1919 and 1921, was used for that purpose. In the official narration of the dominant culture, these conflicts were Polish Uprisings in Upper Silesia. In the narration of some of the organizations within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement, they are categorized as civil war. In the last few years, another narrative has emerged on account of historians. Historian Ryszard Kaczmarek (Reference Kaczmarek2019, 5–15) openly calls these conflicts as an undeclared war between Poland and Germany. Among the respondents, 26.3% absolutely agree and 23.4% agree that these conflicts were Polish National Uprisings, while 22.3% neither agree nor disagree. 12.1% of respondents disagree with that statement, and 15.9% absolutely disagree. Among respondents, 17.3% absolutely agree and 18.6% agree, while 30.7% neither agree nor disagree, with the statement that these conflicts were a civil war. Among the respondents, 16.7% disagree with that statement and 16.7% absolutely disagree. As to the statement that these conflicts were an undeclared Polish-German war, 17.9% of respondents absolutely agree and 20.1% agree, while 35% neither agree nor disagree. 13.9% disagree with the statement and 13.1% absolutely disagree (table 13). There is a correlation between declared auto-identification and answers given to the first and the second questions (table 14). The crosstab suggests that the first correlation is a negative one: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the lower the statistical possibility that a respondent agrees that the armed conflicts from 1919 to 1921 were Polish National Uprisings (table 15). The next crosstab suggests that the second correlation is a positive one: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that a respondent agrees that the armed conflicts between 1919 and 1921 constitute a civil war (table 16). Meanwhile, the third stand (these conflicts were an undeclared Polish-German war) seems to have no correlation to auto-identification.

Table 13. Narration about armed conflicts in 1919, 1920, and 1921

Note: n=371 missing values=13; n=372 missing values=12; n=374 missing values=10.

Table 14. Correlation. Auto-identification and narration about armed conflicts in 1919, 1920 and 1921

Table 15. CrossTable. Auto-identification and armed conflicts in 1919, 1920 and 1921 were a civil war

Table 16. CrossTable. Auto-identification and armed conflicts in 1919, 1920 and 1921 were Polish national Uprisings

In the public debate, the narrative about these armed conflicts resurfaces mostly around anniversaries. For example, during the 2016 95th Anniversary of the Third Silesian Uprising, the Sejmik Województwa Śląskiego (Regional Council) adopted a resolution to commemorate all the participants in these events. Some politicians objected to commemorating the participants on both sides of the conflict, instead of praising only those fighting to bring this region under Polish rule. The same politicians called the resolution “the victory of historical policy promoted by RAŚ” (Krzyk Reference Krzyk2016).

Elements Chosen by the Respondents

Categorization of Silesians as a Group

The categorization of Silesians as a group is a controversial issue. Opinions on the matter vary from one extreme to another: they are a stateless nation or they are Poles (part of Polish nation). If nationhood is understood as citizenship, Silesians are citizens of Poland and legally part of the Polish Nation, according to the Preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, from April 2, 1997 (National Assembly, Reference Assembly1997). If nationhood is understood in ethnic terms, as belonging to a group with linguistic, cultural, and sociopolitical features, the answer is not so simple. Many Polish scholars perceive Silesians as a separate ethnic group (Nijakowski Reference Nijakowski and Nijakowski2004, 155; Szczepański Reference Szczepański and Nijakowski2004, 114; Wanatowicz Reference Wanatowicz2004, 212; Kijonka Reference Kijonka2016, 8). Consequently, their culture would need to be categorized as a nondominant culture, and they should be seen as a minority group.

In the focus group interviews study, the opinions of the members of organizations were divided. There is consensus that Silesian culture is separate from Polish culture, but the consequences of this fact are seen differently. For members of some organizations, Silesians constitute a cultural minority within the Polish Nation. For the others, they are an ethnic group or even a stateless nation, and they should be recognized as a minority pursuant to Polish law.

In the quantitative study, mostly positive answers were given to the statement that Silesians are part of the Polish Nation (62.4%). 43.5% of respondents agree that they are an ethnic group. A smaller percentage of respondents agree that they are a separate nation (21.6%) (table 17). One categorization was chosen by 271 respondents (71.9%). Two categorizations were chosen by 98 (26.0%). All three categorizations were chosen by 5 respondents (1.3%). These results indicate that for more than a quarter of respondents it is possible to categorize Silesians in more than one way, such as part of the Polish Nation and as a separate ethnic group. There is a correlation between the declared auto-identification and answers given to the first and the third questions (table 18). This correlation is a negative one in the former case: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the lower the statistical possibility that a respondent will choose to categorize Silesians as a part of the Polish Nation, except respondents declaring themselves as Poles (table 19). However, the correlation is a positive one in the latter: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that a respondent will choose to categorize Silesians as a separate nation. The exceptions are respondents declaring themselves as Poles (table 20). The second stand, Silesians as constituting an ethnic group, seems to have no correlation to auto-identification.

Table 17. Categorization made by the respondents

Table 18. Correlation. Auto-identification and categorization

Table 19. CrossTable. Auto-identification and Silesians are a part of the Polish Nation

Table 20. CrossTable. Auto-identification and Silesians are a separate nation

The problem of categorization of Silesians became evident when the results of the National Census from 2002 and 2011 were analyzed. The term nationality was introduced into the public debate about the status of Silesians during the census in 2002. It was understood as belonging to a national or ethnic group. Some scholars and politicians strongly contested this definition as too wide and encompassing too many different identities with different statuses (e.g., Popieliński Reference Popieliński2014; Kijonka Reference Kijonka2016). The same term was used in the 2011 census. The total population of Silesians in Poland in 2011 was determined to be 846,719 (2.2% of the total population of Poland; 15% of the total population of Śląskie voivodship, and 10% of the total population of Opolskie voivodship) (GUS 2015, tab. 54). Of those surveyed, 376,600 (45% of all Silesian responses) said they were of Silesian nationality exclusively. The rest chose double identification, with Polish or German identification. Since 2002, when 173,153 citizens (0.4%) declared Silesian identity, this number increased almost fivefold (GUS 2004, 35). There may be few reasons for that situation. In the 2002 census, every person could choose only one national or ethnic identification. In the 2011 census, every person could choose two (complex identity—55% of all Silesian auto-identifications). Moreover, many social and cultural organizations of minorities conducted information programs and agitated to choose a minority identification (Gudaszewski Reference Gudaszewski, Łodziński, Warmińska and Gudaszewski2015, 75–76). The census questions in the 2002 and 2011 censuses were quite similar: “To which nationality do you belong?” (2002) and “What is your nationality?” (2011).

Furthermore, the citizens’ legislation initiative on modification of the National and Ethnic Minorities and Regional Language Act from January 6, 2005 (Polish Parliament, 2005), which was submitted to the Sejm on August 27, 2014 (Polish Sejm, n.d.), should be seen as a consequence of categorization of Silesians as a separate group. Most of the organizations within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement were engaged in collecting signatures under the project of this amendment, which aimed at introducing Silesians as the fifth ethnic minority recognized by Polish law. Sejm rejected the amendment in 2016, and the legal status of Silesians remains unclear. The EU Network of Independent Experts on Fundamental Rights stated that “other Member States, some of which, while accepting that minorities exist on their territory, restrict the notion only to certain groups […] while other groups are being excluded from that notion which, arguably, should be recognized as applicable to them (for instance […] the Silesian minority in Poland)” (E.U. Network of Independent Experts on Fundamental Rights 2005, 10–11). Furthermore, the Third Opinion on Poland, adopted on November 28, 2013, by the Advisory Committee of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (2014), highlights that “diverging opinions remain as to the options available regarding protection of the Silesian identity and language” (par. 206).

According to the results of the quantitative methods in this research, most respondents absolutely agree (37.4%) or agree (24.9%) that Silesians should be recognized as the ethnic minority. Some respondents (18.8%) neither agree nor disagree. Less than a quarter of respondents (11.1%) disagree or absolutely disagree (7.7%) (table 21).

Table 21. Recognition of the ethnic minority

Note: n=377 missing values=7; n=379 missing values=5.

Familial Bond to the Region

Familial bond to the region is understood as the descent from parents (mother, father or both) who are Silesians. Silesian identity, sometimes referred to as Silesianism, is the central problem of the ethnicity. Scholars have attempted to define Silesianism as “a state of mind, related to time and space, historical experience and habits” (Kunce and Kadłubek Reference Kunce and Kadłubek2007, 67). It can be argued that it is a collection of the elements of culture encompassing traditions, heritage, language, and habits. If so, it is acquired in the process of socialization. This is the reason why people whose early stages of socialization is connected to Silesian culture have stronger bonds to it.

In the qualitative study, respondents stressed that belonging to the Silesian ethnic group is based on descent, to some extent, but that personal choice is more important. The question “What does it mean to be Silesian?” was posed. One of the answers was very specific but used general terms, which were very inclusive: “We have a definition, which we have been promoting for years: […] everyone who was born in Silesia or his/her ancestors come from here, identifies himself/herself with the culture, and, most importantly, declares to be Silesian.”

The role of the familial bond was confirmed in the quantitative portion of this research. Most of the respondents’ mothers (79.8%) and fathers (74.5%) came from Silesia (table 22). Furthermore, there is a strong correlation between declared auto-identification and place of birth of the respondents’ mothers (table 23). This correlation is a positive one: the more dominant Silesian identification is, the higher the statistical possibility that the respondent’s mother comes from Silesia. The exception here is the respondent who identify as European (table 24). Although taking into consideration what was stated above, that Silesian identity is developed in the process of socialization, especially at its early stages, this statement may plausibly be reversed: if a respondent’s mother comes from Silesia, there is a higher statistical possibility that the respondent declares themselves as Silesian.

Table 22. Ties (familial) to the region

Table 23. Correlation. Auto-identification and familial bonds

Table 24. CrossTable. Auto-identification and my mother comes from Silesia

It can be assumed that Silesian identity is connected to living (and being born) in Silesia (territorial bond), but it is also connected to their descending from inhabitants of the region (familial bond). The first few passages of the ŚR Political Manifesto is translated as follows:

“Modern Silesia is a land where its indigenous population is treated more often as citizens of a ‘second category.’ We are not respected either in Poland or in the Czech Republic: neither our culture, identity, history nor different way to govern” (Ślonzoki Razem,“Manifest,” n.d.).

Two points of these passages are particularly interesting. First, Silesians are referred to as an indigenous population. Regardless of many diverse definitions of this term developed in scholarly literature, it usually encompasses populations that have been living on their native territory for generations, before other groups arrived there (Popova-Gosart Reference Popova-Gosart, Berthier-Foglar, Collingwood-Whittick and Tolazzi2012). This term is used to display the connection between Silesians and the region as well as the originality of Silesian culture, even if Silesians as a group fully embrace modernity and even if most of their traditions stem from the industrial era. It is also used to stress Silesians’ role as the hosts of the region. The last argument was made in the program of ŚPR as well. Second, it is an example of the argument that Silesian culture, which is a nondominant culture, is not respected by representatives of the dominant culture. In this way, both parties (ŚPR and ŚR) present themselves as representatives of the ethnic group, which is seen as wrongfully deprived of its position and rights (discriminated against).

This grievance is present in the collective memory of the indigenous population of Upper Silesia, Silesians (the region historically referred to as Prussian Upper Silesia, and later as Polish Upper Silesia). Silesians call this grievance Silesian harm or Silesian injustice. It is described as follows:

Tadeusz Kijonka, a local poet and—what is important for us—an activist engaged in the protection of Silesian culture, long ago expressed his views about the issue, stating that: “the so-called Silesian harm” […], one can long talk about old resentments, complexes and complications of this issue. It is not a new issue, and even more, it is not a problem that is easy to solve. Because of this, it is worth revisiting accurate and thorough diagnoses […] from the years before World War II […] warning of the impending downfall. This can be followed by an assessment of the old prejudices and accusations of separatism. Afterwards, the war added fire to old accusations of separatism, particularism, and national indifference of a significant part of the population, which created new dramatic barriers, resentments, and divisions, perfidiously exploited by manipulators and dodgers […]. It was accompanied by […] a neglecting attitude toward local traditions, expressed by different sorts of kulturtragers.

(Kijonka 1988 after Gerlich Reference Gerlich1994, 5)Kulturtrager is a name used in Upper Silesia and comes from the German word Kulturträger, meaning carrier of culture. It is a person who imposes culture and values on other communities; also, it is a person who transmits culture.

Role of the Region in Respondents’ Lives

The role of the region seems to be the most elusive element of the Silesian identity. It encompasses two problems. First, it is important to inhabitants of the region to declare the role that the region plays in their lives. Second, the region is seen as Motherland, or rather the little Motherland, private/intimate homeland, or even ideological homeland (Ossowski Reference Ossowski1947). In my article, the term Heimat is used to describe this. Furthermore, this problem raises questions about the possible existence of the opposition centre-periphery. Are the problems of the region more important than those of the state for Silesians? Is the region more important for its inhabitants than the state?

In the quantitative portion of this study, when prompted with the statement “Silesia is important for you,” most (67%) of the respondents absolutely agreed or agreed (22.4%). A minority of respondents selected “I do not agree nor disagree” (9.2%). Only a little more than 1% said they disagree or absolutely disagree (table 25). Most respondents (52.7%) absolutely agree. About 17% (17.2% agree) that Silesia is their Heimat. Some 16.6% do not agree nor disagree with that statement, while 5.6% disagree and 7.9% absolutely disagree (table 25). Furthermore, there is a strong correlation between declared auto-identification and answers to both questions (table 26). This correlation is positive in both cases, though with some differences. Still, the more dominant the Silesian auto-identification, the more statistically possible it is that the answers for both questions will be strongly positive (table 27 and table 28).

Table 25. Attitude toward the role of the region in respondents’ lives

Note: n=379 missing values=5; n=355; missing values=29.

Table 26. Correlation. Auto-identification and role of the region

Table 27. CrossTable. Auto-identification and Silesia is important to me

Table 28. CrossTable. Auto-identification and Silesia is my Heimat

Both aspects of attachment of the inhabitants to their region are exploited by political parties. They do so by choosing as their main goal to represent the political interests of the region and the regional inhabitants. For example, ŚPR has written, “We create the program for Silesia. […] We are open for all inhabitants of the region. We come from here. We do not have instruction from Warsaw [the center]” (Śląska Partia Regionalna, n.d.). Similarly, in the description of ŚR we read, “The goals of party Ślonzoki Razem are based on the well-being and development of Silesians and Silesia” (Ślonzoki Razem, “O nas,” n.d.). Furthermore, the attachment of the politicians to the region is pointed out by ŚPR: “The councillors of Śląska Partia Regionalna will not run from Silesia [to the center, the Polish Parliament]. They won’t disappoint the voters because they treat their duties and work for Silesia seriously” (Śląska Partia Regionalna 2018d).

Three features within these descriptions should be highlighted. First, both parties present themselves as representatives of the region and its inhabitants. Second, both parties create programs for the development of the region regardless of statewide context. Their programs are created in Silesia and for Silesia. ŚPR especially stresses the development of the programs for Silesia and by Silesia by denying any connection to central policy-making actors and institutions. Third, for ŚPR representatives, strong political influence in the region is the main goal in their political careers.

The respondents’ attachments to the region is reflected in the programs and declarations made by activists from both parties within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement. Activists’ demonstration of attachment to the region has two goals: (1) to present the parties as representatives of the Silesian people and (2) to make themselves appear more reliable in the eyes of their target group.

Furthermore, as pointed out above, the parties highlight the opposition between the center (Warsaw) and the periphery (Silesia). ŚPR representatives point out, for example, that central policy making and statewide political goals do not drive them. They present themselves as representatives of the Silesian people and the region of Silesia, but of no one and nothing else.

The role of the region shows up in the demands to change its political status (table 29). The question was posed in the form of a multiple-choice question. The biggest group of respondents (46.8%) believe that the regional status should not change. Still, this group is a minority. The second biggest group (46.5%) believes that the voivodship should become one of the autonomous regions in Poland. The next group (36.4%) believes that it should be a voivodship with broader competences (functions) than today (only administrative). The fourth group (34.5%) believes that the region should be a state within a federation. The smallest group (32.2%) chose the answer that this region should be the only autonomous region in Poland. Support for the autonomy of the region resembles the support described by Orlewski (Reference Orlewski2019, 82).

Table 29. Preferred legal status of the Silesian voivodship in the future

Multiple choices were possible.

ŚPR did not refer to the demand for autonomy (Śląska Partia Regionalna, “Program,” n.d.). However, ŚR considered it as a possible solution but did not see it as a main political goal (Ślonzoki Razem,“Manifest,” n.d.).

Commentary

Based on the results presented in this study, Silesian ethnic identity has become politicized in many ways. Programs, campaigns, and political actions of the organizations within the Silesian ethnoregionalist movement tend to adjust to the expectations of their target group, native Upper Silesians.

First, symbols of Silesian culture are used in the rhetoric of the organizations, especially among the parties. The language of the campaigns and programs also invoke the bond between the community and those who desire to be its political representatives. Second, Silesian ethnic identity is exploited by the Silesian ethnoregionalist movement in politics. Many political initiatives and protests are connected to the collective memory of Silesians and categorization of Silesians as a group. Third, the role of the region for Silesians and the role of Silesians for the region are used as common grounds for organizations (parties) and their supporters (electorate).

The biggest differences between the organizations and the community are the roles they assign to territorial bonds and familial bonds to the region. While it is obvious that organizations within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement and Silesian parties define Silesians by territorial bonds, members of the community itself believe that familial bonds are as important, if not more.

To a very limited extent, it can be said that the Silesian ethnoregionalist movement has influenced Silesian ethnic identity. The so-called new traditions are not widely popular, even if they are slowly gaining a place in the life of the regional community. Furthermore, narration of the past in the form of collective memory is indeed more open today and has become part of public debate, but it was not changed by the ideology presented by the ethnoregionalist movement. Still, not so long ago, the collective memory of Silesians was described as a “secretive, concealed memory,” hidden from public discourse (Hajduk-Nijakowska Reference Hajduk-Nijakowska, Szczepański, Nawrocki and Niesporek2010, 74). Today, it is voiced aloud and fiercely debated in the public sphere. The same can be stated about the usage of the Silesian language, which slowly fights its way into the public space. This change can be connected to the phenomenon recognized by Elżbieta Anna Sekuła as the emergence of the “RAŚ generation” (Reference Sekuła2009, 358). In Silesia, being Silesian has become somewhat fashionable; shops specialize in selling products connected to Silesian culture and language. Every year more names of cafes, restaurants, and other facilities are translated into Silesian (or created in this language). To conclude, one of the most important effects of the existence of the Silesian ethnoregionalist movement is the openness with which Silesianism is displayed today in public spaces.

Undoubtedly, being Silesian (in the perception of Silesians) to some extent shapes the social status of the individual. This discrimination is called Silesian harm. In some cases, it is even further assumed that being Silesian leads to being seen as the “citizens of the second category” (see also Kijonka Reference Kijonka2016). Additionally, the scope of programs and the nature of organizational campaigns within the Silesian ethnoregionalist movement lead to the conclusion that ethnic identity can be invoked to gain the support of voters. The target group of both political parties is clear-cut. The parties almost exclusively appeal to the ethnic bond between the community and its potential political representatives. It can be stated that in the case of Silesians, ethnicity is both socially and politically relevant.

The analysis of the programs by two political parties in the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement, Śląska Partia Regionalna (ŚPR) and Ślonzki Razem (ŚR), leads to one further conclusion. Historically, observers could identify one intragroup conflict within the movement: between regionalists (Związek Górnośląski [Upper Silesian Union] and others) and autonomists (Ruch Autonomii Śląska and others). The former supported the preservation of Silesian culture without emphasis on its separateness or recognition. They also supported further decentralization of the state but did not go as far as to demand autonomous status for the region. The latter group demanded both legal recognition for the Silesian ethnic minority and the introduction of some form of political autonomy for the region. Results in this study showed that both stances have almost equal support among respondents.

Since 2017, when the parties were created, a new split has taken place within the autonomists between the progressive and conservative groups. ŚPR is an example of the progressive group. The party created a program to develop the region in baby steps and slowly install the regionalist agenda (“spill-over effect”). ŚR is an example of a conservative group. Its program, which has been present in Upper Silesia since 1989, focuses on ethnicity and recognition but also mentions the possibility of regional autonomy in the future. The results of the elections in Poland in 2018 proved that both stances have almost equal support among voters. In the elections to Sejmik Województwa Śląskiego (Regional Council), ŚPR received 54,092 (3.1%) votes, while ŚR received 56,388 (3.2%) votes (Państwowa Komisja Wyborcza n.d). Still, support for ethnoregionalist parties in the Silesian region is limited but has been stable since 2010.

What remains now is to place the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement into a wider, European context. Ethnoregionalist movements, especially across EU Member States, have become a wide-spread phenomenon, and in almost every state at least one movement is active. Many of the movements (and parties) stem from border regions (e.g. Friuli, Occitania, Schleswig, and Upper Silesia). The most obvious difference between the movement in Poland and Western European movements is its late appearance; however, a similar movement had existed in the interwar period. As to the program, there are further similarities to other movements. Protection of minority language was from the very beginning one of core goals of Welsh Plaid Cymru and Union Démocratique Bretonne, similar to the Upper Silesian movement. But, as the Silesian language plays a smaller role for ordinary Silesians than their bond to their little Motherland, the movement has adopted the model of “points of focus,” closer to the position of the Scottish National Party. However, the Upper Silesian movement cannot be considered nationalist because it lays no claim to a separate state, only for autonomy within an existing one. Silesian ethnoregionalists perceive the EU as an ally in their fight for minority rights, which is typical for many ethnoregionalist parties (Stefanova Reference Stefanova2014). At the same time, similarly to Lega Nord in the past, they make a clear distinction between the modernized economic power of their own region and the poor, anachronistic rest of the state. With the Catalan and Basque movements, the Upper Silesian movement shares the weight given to civic action, the right of the people (host of the region) to decide, and the use of a center-periphery opposition. However, contrary to Catalans and Basques, most Silesians categorize themselves as members of an ethnic group, not as a separate nation.

Summary

The Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement exploits all seven elements of modern Silesian ethnic identity. They use Silesian language in political campaigns to represent organizations and their programs. Furthermore, one of the main political postulates of the organizations within the movement is the codification and legal recognition of the Silesian language as a minority or regional language. Territorial bonds of the inhabitants to the region are used in the narrative to support codification and recognition. The narrative portrays party members as representatives of the population, who care about the development of the land and its people. These territorial bonds are also used to promote the inclusive definition of who is Silesian and, subsequently, who belongs to the target electorate group of the ethnoregionalist parties. Customs and traditions are used as symbols in political campaigns. Furthermore, so-called new traditions are being created to promote the awareness of certain events connected to the collective memory of Silesians. A distinct collective memory has become one of the most recognized features of Silesianism. Consequently, organizations within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement eagerly use it in public debate to evoke opposition between the dominant and nondominant cultures and to influence voters along ethnic lines.

Familial bonds to the region are one of the main features constituting Silesian ethnicity. They are exploited mostly by stressing the native (indigenous) character of Silesians in the region. Moreover, they serve to present political representatives of the ethnic group as the hosts of the region, who should be allowed to take part in decision-making processes, at least at the regional level. They are also the main transmission line of the grievance of “Silesian harm”, which invokes the need for separate political representation of this minority. Categorization of Silesians as a group strengthens the split between the majority and the minority. Additionally, it is the main reason behind the claim for the recognition of Silesians as an ethnic minority, one of the most important goals of organizations within the Upper Silesian ethnoregionalist movement. Lastly, the role of the region in respondents’ lives is used in the campaigns and political programs. Its use enables organizations within the ethnoregionalist movement to gain support for changing the political status of the region, which is one of the main demands related to center-periphery opposition. The opposition is also used to make the representatives of the ethnoregionalist movement more reliable in the eyes of their target group, Silesians.

In summary, organizations, especially political parties within the Silesian ethnoregionalist movement, exploit ethnic identity by using symbols and by strengthening the Silesian narrative. There are three main goals behind these actions. First, they are evoking two oppositions: center versus periphery and dominant versus non-dominant culture. Second, they are stressing the lines which emerge from these oppositions and mobilizing the electorate by voicing the separate interests of the ethnic group. Third, they appeal to these needs by creating campaigns, programs, and demands, which are proposed to satisfy them.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.