Introduction

A thriving international tourism industry has formed in Georgia over the past few years (GNTA 2016), pulling into its orbit Khevsureti, a small region of about 1000 square kilometers on Georgia’s northern border with Chechnya. Cafés, restaurants, and guesthouses have recently popped up along the mountain road and around popular destinations. In the capital, bargain travel offers in Russian and English are seen superimposed on images of famous Khevsureti attractions in the windows of tourism agencies and on rugged vehicles for hire.

From Tbilisi, a drive to Khevsureti takes less than two hours, with another two and a half hours on dirt roads to its most famous site, the fortress village of Shatili on the Georgia-Chechnya border. This makes Khevsureti a convenient jaunt for tourists aching to take in old defensive towers and castles, snowy peaks, and sweeping mountain vistas with less than 48 hours to spare.

Khevsureti is also the historic home of the Khevsurs, Kartvelian highlanders often romanticized because of their stone fortresses and towers, their beautifully embroidered clothes, their tradition of dueling, raiding, and blood feuds, and for the much-discussed fact they carried swords and owned chainmail. Thanks to these features and to their wonderful mythology, their heartbreaking love traditions (Manning Reference Manning2015), and their so-called pagan religious customs, Footnote 1 the Khevsurs have long been a popular subject for articles, guidebooks, blogs, research, and ethnographies.

As anthropologist Paul Manning (Reference Manning2010, 416) points out, the Khevsurs have become “the prototypical object of Georgian folklore and ethnography since the 19th century,” one result of which has been an eclipsing of neighboring peoples. This popular attention to Khevsureti has also resulted in much distortion, such as cartoonish beer-swilling Khevsurs in television advertisements, a web of Internet speculation, and an exaggerated place in the promotional materials of a mushrooming tourism sector.

Yet of all the misrepresentations of Khevsureti and the Khevsurs, one long-standing example stands out as the most tenacious, pseudoacademic, Occidental, and ahistorical: the widespread speculation that the Khevsurs are the descendants of a band of lost European knights from the Crusades. With the popularity of the region growing, this unfortunate meme has found new life in recent years.

This article not only will thoroughly discredit this recurring story but also will trace the formation of this fantasy and examine how it has propagated itself throughout its history and into the present day. It analyzes the features of this story in terms of invented histories and the misappropriation of culture, showing it to be another projection of Western European ethnicity into Georgia. Finally, it concludes that, while this story ought to be put in its right place, as of yet it has done little to hurt Khevsur culture or history. On the contrary, it offers many instructive points about the nature of pseudoarchaeology and the romantic ambush of imaginations.

The Holy Crusader Meme in Popular Sources Today

The Caucasus have long provided bountiful raw material for Western and Russian storytelling as well as a stage for modern political posturing, a foil for national identities, spaces for biblical extrapolations, backdrops for European historical fiction, and a plethora of stock and staple material for academic dissertation. Thus, we find here the heroes of Russian literature losing and discovering themselves. We read of the moral fretting of Russian elites over their government’s genocidal border policies. We encounter pseudoscientific speculations of Caucasian racial origins. We see a carefully staged photograph of John McCain with a gift basket reaching out to a villager over a barbed-wire fence with paternal democratic concern. We read the Greek myths of Prometheus, Jason and the Argonauts, and Medea in the strange lands across the Black Sea. And we watch popular works of Soviet cinema using empty fortress villages as movie sets.

This article narrows its scope to Khevsureti and to the widespread “Crusader myth.” In its most popular version, the story tells of a band of forlorn knights, lost or chased or abandoning their cause and who find themselves in a far-flung corner of the Caucasus where they settle down, find women from neighboring villages, and make the best of it. These men, so the story goes, are the forefathers of the Khevsurs of Khevsureti. Their secret history has fallen into obscurity for nearly a millennium, all but lost until sharp-eyed travelers detected remnants of the Crusader heritage in the habits and dress of a degenerated progeny.

Today tourism guides promise the full medieval experience, embellishing their services with an (often copypasted) Crusader story. Blogposts and message boards abound, discussing the “Lost Crusader” origin story as a “hypothesis” and a “theory,” referencing “the experts” and “the evidence” of ethnographic and historical sources (see, for example, World Historia n.d.; Greenacre Reference Greenacre2016).

It gets worse. In November 2018, a Google search for the innocuous terms “Khevsur” and “history” returned a list of pages, seven out of the first ten of which devoted space to serious treatment of the story. A newspaper article by Bill Donahue (Washington Post, March 20, 2014) states as fact that in Khevsureti, one finds “nature-worshiping Christians descended from the last Crusaders of Europe.” Historical fiction author Jody Andrews of Westminster, Colorado, describes his yet-to-be-published novel The Wolf and the Lion on his blog as “inspired by the real-life discovery of descendants of 12th century French Crusaders in the mountains of the former Soviet Union” (Andrews Reference Andrews2014). Across the entries of several languages, Khevsur-related articles found on Wikipedia also treat the story as a credible theory.

The fact that Georgia is a small, remote, and ancient country lends it to unchecked romancing in the West today just as it did for writers of popular books and articles in the past. Only a few online resources exist to counter the Internet misrepresentations. Most notable are the efforts of Caucasus expert Alexander Bainbridge, whose excellent website www.batsav.com offers detailed and well-researched information about the peoples of the Caucasus, including personal communications with scholars and his own translations into English of much material (Bainbridge 2006–Reference Bainbridge2015).

Evolution of the Khevsur-Crusader Meme

For the English-speaking world, Richard Halliburton (1900–1939) is the writer most responsible for popularizing the idea that a remote tribe of the Caucasus is the far-flung lineage of knights from the Crusades. Halliburton reports to have made the journey in the 1930s with his assistant Fritz, traveling from the Black Sea to Tbilisi and then up to the lone trail that leads to Khevsureti. After strapping iron crampons to their boots and glancing at the sky with apprehension, the pair braved the snowy cliff paths far above the icy river and six hours later reached the first Khevsur village.

This account is found in the chapter entitled “The Last of the Crusaders” in his 1935 book Seven League Boots (Halliburton Reference Halliburton1935a). According to Halliburton, legend has it that the Khevsurs originally hailed from the German-French region of Lorraine and headed east in the service of Frankish knight Godfrey of Bouillon (ca. 1060–1100). For support, he cites the Khevsurs’ French-style armor, noting that their “otherwise incomprehensible speech still contains six or eight good German words” (Halliburton Reference Halliburton1935a, 211). Whether the knights had arrived as explorers or were fleeing for their lives is not known. What is known, he explains, is that they entered the Caucasus and did not emerge again until 1915 when their descendants heard rumors of a great war, donned the armor of their forebearers, and rode to Tbilisi to join the good fight.

Across the United States, Halliburton’s (Reference Halliburton1935b, Reference Halliburton1935c, Reference Halliburton1935d) articles about Khevsureti were snatched up by restless newspaper editors eager to wow their audiences with his discovery. On February 3, 1935, several outlets ran with the story. “Haliburton Finds Knights in Armor,” reported the Daily Boston Globe with the subhead, “Crusaders, Stranded in a Caucasus Fastness, Left a Colony Where Money Is Unknown, Where Dueling Is the Only Sport, and Barbarities of the 12th Century Persist Today.” For readers of the Tribune Media and The Baltimore Sun: “The Last Crusaders: Living in Twelfth-Century Atmousphere, the Khevsoors Duel in Armor.” The Pittsburg Press reported “Last of Crusaders Found in Remote Caucasus.”

Haliburton never mentions how he first learned of the Khevsur-Crusader story before traveling there himself to research his new “believe-it-or-not” adventure book. Quite possibly he came across a short article in the Christian Science Monitor which ran on October 8, 1926, entitled “Descendants of Crusader Inhabit Caucasus Mountains.” This piece lists its author as “Moscow (Special Correspondence)” and reports a meeting on the Georgian Military Road between a “Miss Anna J. Haines of Moorestown, N J.” an “affable” Khevsur dressed in armor, with a short sword, round shield, and crosses embroidered on his cloak. The report then claims that the “Hev-Souri” are believed to be “descendants of the Crusader who captured Constantinople early in the thirteenth century.” This is the earliest example of the meme in English I have been able to find.

Just a few years before Halliburton’s account was published, Lev Nussimbaum (1905–1942), writing in German under the penname Essad Bey, offered his own account of the Khevsurs’ Crusader origins in his 1931 book Twelve Secrets in the Caucasus (Bey [1931] Reference Bey2008) in the chapter entitled “Christians Who Do Not Know the Name of Christ.” Like Halliburton, Nussimbaum cites their manner of dueling, their armor, and the inscriptions on their swords and shields. Unlike Halliburton, however, Nussimbaum equivocates, stating only, “Who can the Khevsurs be, the proud wearers of the Maltese cross, the cavaliers arrayed in steel? Crusaders, perhaps, driven from Palestine and forced back into the mountains, where they have gone wild, as the legends of the Caucasus will obstinately testify” (Bey [1931] Reference Bey2008, 92).

Halliburton struggled to be taken seriously in his own time and was accused of rampant exaggeration (Alt Reference Alt2014, 193), but unlike Nussimbaum, he visited Khevsureti, and his well-coordinated research and writing lends the tale a superficial plausibility. For example, he briefly mentions that the French knights hailed from Lorraine and were followers of Godfrey de Bouillon. This was not pure invention but a clever coupling of obscure relevant associations: Godfrey de Bouillon was from a French-German province and is buried in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, a church that holds a special place in the Georgian Orthodox tradition.Footnote 2 In the hands of a good storyteller like Halliburton, details such as these were collected and delivered in a bewitching and head-scratching style.

Nussimbaum did not go to Khevsureti and appears to have borrowed heavily from an account by Russian serviceman and ethnographer Arnold Zisserman (1824–1897) that first appeared as a series of articles the Tbilisi Russian-language newspaper Kavkaz (March 20, 1851). While Halliburton and Nussimbaum are far better-known literary figures, today it is Zisserman who is most often quoted as the founder of the story and as an authoritative ethnographic source.

Nussimbaum’s chapter about the Khevsurs contains several paragraphs that are little more than rewrites of passages in Zisserman, including descriptions of Khevsur manners of dress, personal conduct, details of swordplay, religious practices, the same Latin phrase found on swords as recorded by Zisserman, and even Zisserman’s odd note that Khevsur women were in the habit of washing themselves in cow urine (Bey [1931] Reference Bey2008, 196). As for their alleged Crusader link, Nussimbaum’s thoughts imitate Zisserman’s not only in precise detail but also in tone, right down to the tentative manner in which Zisserman first speculates about the resemblances.

Plagiarizing large sections of someone else’s work was not an isolated incident for Nussimbaum, who posthumously has become infamous for his skill at reinventing himself and borrowing heavily from unattributed translations (Reiss Reference Reiss2005, 48). Most noteworthy is the beloved 1937 novel Ali and Nino: A Love Story, believed to have been written by Nussimbaum under the penname Kurban Said, with sections of it thought to have been plagiarized from Georgian writer Grigol Robakidze’s (1880–1962) book The Snake’s Shirt (Robakidze Reference Robakidze1928; Injia Reference Injia2009).

Another Khevsur-Crusader speculation, also in German, can be found in a 1906 article by geographer N. A. Busch, published in Germany’s prestigious Dr. A. Petermann’s Mitteilungen, a journal focusing on botanical study and in which a short digression into ungrounded ethnospeculation was apparently no cause for concern. What makes Busch’s account interesting is that he had himself visited Khevsureti and references Zisserman’s proposition before adding his own original reasons for thinking that the Khevsurs descended from the Crusaders. Not only do their weapons suggest this connection, Busch writes, but so too does the presence of tall, blond men; their veneration of the cross; a tradition of brewing sacred beer; and their use of silver cups depicting gothic buildings (Busch Reference Busch1906, 224).

In 1917, 11 years after Busch’s publication, the notorious American sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross (1866–1951) had his own encounter with the Khevsurs, who were apparently taking part in a show in the streets of Tbilisi. Impressed with their knightly appearance, Ross made inquiries and was told of their supposed medieval European ancestral connections. This account appears in his 1918 book Russia in Upheaval, where he reports these rumors were relayed to him by Prince Orbeliani, “cousin to the present heir of the Georgian kings” (Ross Reference Ross1918, 65).

According to Ross (Reference Ross1918, 65), Orbeliani told him the ancestors of the Khevsurs had fled the Holy Land and had “settled in one of the high valleys of the Caucasus.” To this, Orbeliani apparently added an incredible level of detail, such as that the original 13 Crusaders included eight Frenchmen, one Englishman, two Italians, and two Spaniards, and that two old Frankish surnames were still to be found among the Khevsurs. He also stated that Khevsurs cherished as heirlooms “certain heavy, two-handed swords that were wielded in Palestine by the forefathers of the tribe” (Ross Reference Ross1918, 65).

Although greatly taken by the tale, to his credit Ross did not let the matter lie there. He brought the story to the attention of “the scholarly director of the Georgian Museum” (Ross Reference Ross1918, 65). This clear-headed man informed Ross that the Khevsurs were not descendants of Crusaders, and that the nonsensical story began when a French writer speculated about a Crusader origin based on the crosses the Khevsurs wore on their garments. With this detail, we seem to be only one step from the first recorded instance of the Crusader story. This French writer is likely Edouard Taitbout, whose version appeared in 1821 (30 years before Zisserman’s Kavkaz articles) in what is the earliest instance of the Khevsur Crusader story I have been able to find.

Taitbout was a businessman and scribbler, who first showed up in Georgia in 1813 seeking commercial ties to Circassia. In 1821, he published Voyages en Circassie, in which he says a “fairly common opinion” holds that it was Crusaders who had been the first to preach Christianity to the mountain people of the Caucasus, having just escaped a worse fate in their holy war (Taitbout [1821] 1836, 74). These cultural traces, he explains, appear in the form of a Maltese cross worn by Khevsurs on their clothes and on their shields and in the French surnames they still bear, such as “Devilete, Guillot, etc”Footnote 3 (Taitbout [1821] 1836, 73). In explaining how he came by this extraordinary information, he simply informs the reader in a footnote that it was relayed to him by fellow Frenchman “M. Hauy major du Génie” (Taitbout [1821] 1836 n. 1).

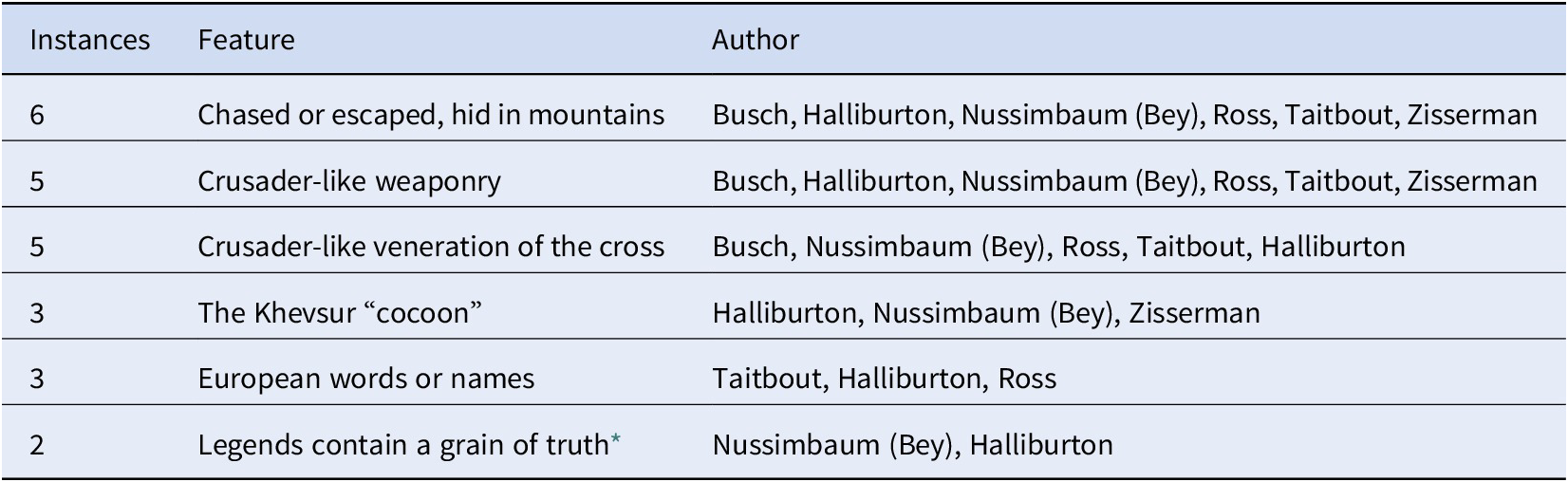

Throughout these many versions of the Khevsur-Crusader meme, several common features recur, and new features are introduced and repeated. These features play progressively more important roles as the story evolved with most compelling become major plot elements in the overall narrative. I have included them as Table 1.

Table 1. Recurring Plot Elements in Early Examples of the Crusader Meme.

* This later feature emerged after the Crusader fiction had been around long enough to be recast as legendary and is now common in Internet speculation about Crusaders in Khevsureti.

Criticism of the Crusader Meme from Contemporary and Historical Scholars

Since Busch and Zisserman, the Crusader question has received almost no serious academic attention. If mentioned by any scholar, it is raised only long enough to dismiss. Caucasus scholars Shorena Kurtsikidze and Vakhtang Chikovani, however, have found this out-of-hand dismissal itself problematic. They object that, while so many denounce “the lost crusader theory of the Khevsurs” as baseless, “no one tries to prove the opposite!” (Kurtsikidze and Chikovani Reference Kurtsikidze and Chikovani2010, 323).

This remark was made in a response to Manning’s (Reference Manning2010) review of their book Ethnography and Folklore of the Georgia-Chechnya Border: Images, Customs, Myths, and Folk Tales of the Peripheries (Kurtsikidze and Chikovani Reference Kurtsikidze and Chikovani2008). In his review, Manning takes issue with the title of the book’s first section, “The Last Crusaders and their Neighbors,” writing “it is ironic that this book, which takes Khevsur mythology as its object, would reproduce what is surely the most marginal of all romantic mythologizations of the Khevsurs… . Soviet-era scholars, and even pre-Soviet ones, had treated this particular theory of Khevsur origins as being an example of tendentious Occidentalism” (Manning Reference Manning2010, 416).

One such Soviet scholar was Sergi Makalatia (1983–1974), a Georgian ethnographer who after briefly mentioning the Crusader speculation writes, “These hypotheses are based upon merely accidental similarities of external features. Unfortunately, these mistaken views on the Khevsurs are widespread today both in Russian and in foreign literature” (Makalatia [1930] Reference Makalatia1984, 20).

Similarly, the German naturalist and explorer Gustav Radde (1831–1903) merely bristles at Zisserman’s Crusader suggestion (Radde Reference Radde1878, 40), noting with dismay its notoriety before turning his attention to Raphael Eristavi (1824–1901), who makes a case for a shared Kartvelian origin of the Khevsurs based on comparative linguistics in his 1855 book The Tush-Pshav-Khevsur District. Eristavi (Reference Eristavi1855, 76) notes that Zisserman had recently published interesting articles about Khevsureti in Kavkaz yet does not raise Zisserman’s Crusader idea, apparently judging it too irrelevant for discussion.

While Manning is correct in saying that the Crusader notion has been largely rejected by scholars, perhaps it is also fair for Kurtsikidze and Chikovani (Reference Kurtsikidze and Chikovani2008) to think that “the lost crusader theory of the Khevsurs” deserves more than an appeal to authority before dismissal. Yet to say the Crusader story deserves a systematic analysis based on the merits of its evidence is still too much. Instead, a careful deconstruction and repudiation will be useful for first for helping remove the story from serious discussions of cultural heritage in Khevsureti, and for showing how historical memes and popular examples of pseudoarcheology can form, spread, and capture imaginations.

A Systematic Repudiation of the Crusader Origin Story

The repudiation that follows shows that the Khevsur-Crusader myth is based on a few dubious details in circulation since the early 19th century that have created the illusion of a legend and a body of evidence. Likewise, it shows that supposed Crusader paraphernalia in Khevsureti has been misrepresented and exaggerated, and that the presence of such items is neither mysterious nor suggestive of Crusaders. Furthermore, crucial to the Crusader story is a depiction of Khevsureti as a sort of time capsule or cocoon with nonporous borders. Once this mischaracterization of Khevsureti is corrected, the story becomes increasingly incoherent.

Finally, this section shows that Zisserman (the story’s most cited supporter) has been incorrectly identified as the story’s originator and, to his credit, gave it far less credence than is stated by both critics and sympathizers.

How Western Writers Created a Fantasy Khevsureti

For the Crusader story to work, Khevsureti must be depicted as a semipermeable time capsule. We must not only plant far-flung Western Europeans into the Caucasus but also keep them there in conditions sufficiently isolated so that they retain elements of their ancient past, such as Crusader armor and symbols, Western European religious and linguistic features, European surnames, and cultural practices or objects.

Halliburton (Reference Halliburton1935a, 211–212) characterizes Khevsureti as “one of the most rugged and unapproachable corners of the Caucuses,” where the Khevsurs were “walled off from the world” and who “have continued to occupy their hidden corner for over eight centuries” from which they would “emerge” in 1905 in full armor to fight in World War I. Over the centuries, Halliburton continues, the Khevsurs’ “otherwise incomprehensible speech [retained] six or eight good German words” (Halliburton Reference Halliburton1935a, 211). Halliburton, conveniently, does not record these words and also fails to mention what he would have almost certainly learned from Georgians or written sources: the Khevsurs speak a dialect of Georgian, albeit one that is difficult to understand.Footnote 4 This vague detail is similar to a rumor noted by Ross (Reference Ross1918, 65) a few years before, suggesting the nearby Ossetians were likely “Ostrogoths in origin, because their language contains various pure Germanic words.”

Yet Halliburton seems to be winking at us while telling his story. A careful reader will notice it takes him and his companion only six hours to reach the first Khevsur village from the road they drove up on. The pass they enter is open only seven months of the year. These inconvenient details are buried under imagery of dangerous snow cliffs and mountain peaks, and Halliburton takes care to conserve facts even as he obscures them. All this suggests that Halliburton was primarily interested in telling an exciting tall-tale based in part on his real experiences and staring himself as a swashbuckling adventurer—a suggestion borne out by his own statements.Footnote 5 If the suspension of disbelief was an understood premise of his books and articles, this is lost on many readers today.

Nussimbaum (Bey) shows even less restraint when depicting an almost cartoonish cocoonlike Khevsureti. He does not claim to have traveled to Khevsureti, yet his account begins with the absurd claim that “a gigantic wall of rock surrounds Khevsuria,” and that the region is only accessible by use of a rope hanging down the face of a cliff (Bey [1931] Reference Bey2008, 90).Footnote 6 For only one month of the year, he writes, it is possible to cross that same treacherous pass through which the “original inhabitants must have first entered” (Bey [1931] Reference Bey2008, 90).

Unlike Halliburton and Nussimbaum, the amateur ethnographer Zisserman respects basic geographical facts and maintains a pretense of impartiality. The Khevsureti cocoon he portrays in Kavkaz relies on implication and vagaries. Phrases like “having entered this isolated realm,” a “place of dwelling protected by nature,” and “forced to stay here forever” (Kavkaz, March 20, 1851) do the work of conjuring the impression of a cloistered existence.

In all its versions, this cocoon-like time capsule for the Khevsurs is itself an ad hoc misrepresentation. In fact, Khevsureti has not suffered from centuries of isolation, as is apparent in any analysis of the region’s folklore, religious practices, social customs, history, or geography. Take, for example, Manning’s (Reference Manning2015) ethnography of love in Khevsureti and Pshavi, which explores the similar Khevsur and Pshav love customs. Or consider Kiknadze’s (Reference Kiknadze2009) concepts of andrezi and sakmo in the Khevsureti-Pshavi regions to describe the organizing principles of place as yoked to local demigods. These fascinating relationships to land are shared by many highland tribes of Northeastern Georgia, and are described by almost all ethnographers of the region.Footnote 7 One might also look at Kevin Tuite’s (Reference Tuite, Tandaschwili and Pourtskhvanidze2011) discussions of “Pxovian ‘cosmological feudalism’” or his analysis of the similar customs concerning people struck by lightning among Khevurs, Pshavs, Tushs, Ossetians, and Kists (Tuite Reference Tuite2004).

A reading of Makalatia’s ([1930] 1984) ethnographic study Khevsureti also immediately dispels the cocoon illusion. Khevsurs have long interacted economically with the lowlands, and Makalatia describes in detail the wars in which they fought alongside lowland Georgians throughout the 17th and 18th centuries (37–40) and their mission to protect Georgia from northern aggressors in the 17th century (29–30). In the early 19th century, they also united with their fellow highlanders against the Russian military (41–45) well before Zisserman entered the “isolated realm” with his imagination and notebook. In short, none of this scholarly work is compatible with a Khevsureti having remained largely isolated since the middle ages.

The Origin of the Crusader Origin Story

Zisserman is widely considered to be both a defender and the originator of the Khevsur-Crusader theory. Manning, Kurtsikidze and Chikovani, Grigolia, Makalatia, Radde, and Busch all refer to him as such but are in error on this point.

In Custom and Justice in the Caucasus: The Georgian Highlanders (1939), Alexander GrigoliaFootnote 8 takes time to treat the Khevsur-Crusader connection with a special contempt and shows how Frenchmen, Germans, and Russians have all taken turns to catch glimpses of their own cultures in the Khevsurs. He (1939, 91–94) cites as examples passages from the writings of Zisserman, Taitbout, Busch, and the archeologist P. S. Uvarov. Yet in making this excellent point, Grigolia follows Makalatia ([1930] 1984) and Radde (Reference Radde1878) in identifying Zisserman as the originator of Khevsur-Crusader connection. He seems to have simply overlooked the dates of his own reference to Taitbout whose Crusader story preceded Zisserman’s by more than 30 years.

Taitbout had been in the region as early as 1813 and rose to prominence as the Dutch vice-consul in Odessa for the Black Sea by 1821 (Hewitt Reference Hewitt and Speake2003). In Voyages en Circassie, he writes that a “fairly common opinion” holds the Crusaders had preached Christianity to the mountain people after having been displaced from their holy wars (Taitbout [1821] 1836, 73).

With Taitbout, we may finally be only one degree of separation from the first Khevsur-Crusader speculation: Taitbout informs us in a footnote that this information was relayed to him by a personal acquaintance: “I owe this information to M. Hauy major du Génie, who may be the only European to have penetrated Khevsur society, where chance has led him, and where he was admitted on account of his being French” (Taitbout [1821] 1836, 74 n. 1).Footnote 9

Why then does Zisserman take credit for the Crusader idea? It is easy to imagine that Zisserman was aware of Taitbout, an important figure in Georgia, and easier still to think Zisserman had, like Taitbout, also heard loose talk about a supposed Khevsur-Crusader connection. Yet Zisserman would have his reader believe his speculation about Crusaders was the result of his own thoughtful observation and a keen historical perspective. Perhaps Zisserman’s posturing was only meant to emphasize himself as a firsthand, authoritative version for readers of local newspapers already vaguely familiar with the Crusader idea.

Whatever the case, Ross’s 1917 meeting with the “scholarly director” shows us that even 66 years after the Zisserman newspaper article (Kavkaz, March 20, 1851), Zisserman was not universally considered the originator of the Crusader story. Instead we meet a museum director having to explain away yet again the persistent Crusader-rumor introduced by a Frenchman and his active imagination. Here we encounter another feature of this meme: like today, it was most fertile in expatriate circles—a Frenchman tells a Frenchman, creating a rumor that influences a Russian, impresses an American, and so on. Of those Soviet-era and pre-Soviet writers to whom the Crusader story sounded plausible, we have only Russians, West Europeans, and Americans. Experienced scholars and certainly all the Georgians—Eristavi, Makalatia, Grigolia, and the famous Vasil Barnovi who wrote a series of articles about Khevsureti in Reference Barnovi1878—have not thought it worth discussing.

Zisserman’s Own Uncertainty

The thoughtful and reflective tone in which Zisserman wrote has helped buoy his credibility as an ethnographer in discussions the Khevsur-Crusader story. Yet did Zisserman have confidence in his own proposition? Academics have cast him in a variety of postures on this point. Makalatia ([1930] 1984, 20) refers to his Crusader notion as an “unfounded hypothesis” unworthy of further discussion. Radde (Reference Radde1878, 64) calls his opinions conjecture. Busch (Reference Busch1906, 222) goes so far as to say that Zisserman believed that the Khevsurs were of German descent, but Grigolia (Reference Grigolia1939, 10) characterizes him as expressing only an opinion of possible origin. More recently, Kurtsikidze and Chikovani (Reference Kurtsikidze and Chikovani2008, 322) have written that Zisserman “believed the Khevsurs to be the descendants of an army of crusaders,” while Manning (Reference Manning2010, 416) impatiently calls him a Russian romantic, “who in the early 19th century, upon seeing the Khevsurs dressed in chain mail with Frankish swords, decided that they were a group of lost crusaders.”

My first readings of Zisserman’s original Kavkaz passages were anticlimactic—I had been looking forward to disapproving of his carelessness and lack of scholarly scruples. Yet Zisserman, with his doubt and broad qualifications, took the wind out of my war banners. As silly as his musings may have been, he deserves some credit for emphasizing their speculative nature.

Nothing should deflate the Khevsur-Crusader fantasy more quickly than its main author’s own serious misgivings and faulty memory. For this purpose, I present translations of the two offending sections.Footnote 10 The most commonly cited source for the Crusader story is Zisserman’s Reference Zisserman1876 memoirs, 25 Years in the Caucasus, yet earlier instance appeared in one of a series of articles Zisserman wrote for the Tbilisi newspaper Kavkaz in 1851. A comparison of these texts shows how tentative his opinions were from the beginning and helps explain why his name has become the nucleus around which this romance has grown. In his 1876 memoirs, he writes:

Judging from these costumes, armor, and many swords with the engraving: “Solingen, vivat Husar, vivat Stephan Вatory, Gloria Dei,” and also from many of their habits and customs, I came to the ask the question, of course in speculation, are the Khevsurs perhaps the descendants of crusaders, some of whom could have been lost in these Caucasian mountain ranges and been forced to stay here forever? Afterwards, they inter-married with nearby mountain Georgian tribes, they adapted themselves and adopted their language. Detailed descriptions of these extremely original people, I placed into the newspaper Kavkaz in 1847, I think. I don’t find it appropriate to repeat it here; such long digression would completely halt the thread of my memories, but the descriptions of the traditions and manners of these mountain dwellers, told in those dedicated pieces, are quite interesting

(Zisserman Reference Zisserman1876, 190).Footnote 11This cursory treatment in his memoirs largely defers to his earlier articles and leaves the reader with the impression that this Khevsur-Crusader connection is better explored therein. In any case, his self-citation was off by four years, perhaps confused with the founding year of Kavkaz, which was in 1847. The relevant 1851 section reads:

Otherwise, I have often wondered if they are not descendants of the Crusaders, which have been scattered over the whole world. Is it not possible a couple of them got left behind by their comrades, or else marched with the Georgian kings in the crusades, or else due to unfortunate events were scattered in the East and having entered this isolated realm, chose it as their place of dwelling, and perhaps married with neighbor mountain people, with Kists, Pshavs and Tushs and founded a powerful military society, which was protected by nature, and their number perhaps gradually was added to from other refugees and resettled peoples?

For this hypothesis, which is not any less strange than [the Khevsurs own origin story], serves to explain the close similarities between the manner of dress and armament of Khevsurs and the Crusaders, which do not look like those of any of the local tribes. They have square hats, with hanging leather straps wrapped in strips of cloth, the ends of which hang like cockades. They have chokhas the bottoms of which along the hem, are cut like strips of cloth, and scrunched sleeves. Iron shields, straight swords, all of them are covered with this inscription: “Genua Souvenir Vivat Stephan Batory, Vivat Husar, So lingen,” and depictions of eagles, horseman and crowns. Women wear bracelets, earrings, dresses with several wrinkled layers which widen at the bottom into hoops, similar to the layers of a petticoat, they have wide woolen belts with two big tassels, on their heads they wear turban like wraps, necklaces, long socks instead of pants, and many other small things. All of this inadvertently reminds us of middle ages, of a time of knights who fought for their faith… . But I repeat, this is merely a proposition, not fact

(Kavkaz, March 20, 1851).In spite of the implication in his memoirs, the original article offers little to add in way of support of his Crusader speculations. Instead, we find a few details about their clothes, along with more romance, more imagination, but also more skepticism. Importantly, Zisserman had originally taken care to drive home its speculative nature: it is not facts but his impressions that “inadvertently reminds us” of Crusaders. It is “merely a proposition, not fact.” Unsurprisingly, the propagation of the story today has depended upon the later version which is both more vague and more confident.

The Khevsurs’ Medieval Weapons

Thirty years later, when writing in his memoirs about his time with the Khevsurs, it speaks to the power of meme that Zisserman believed he had initially better supported his idea. Evidently, he did not have a copy of his original article on hand, as in addition to misremembering the year, one will notice that the text of the inscription found on the swords has also changed. This inscription covering the “iron shields” and “straight swords” is a central detail in both of Zisserman’s accounts and has been most faithfully cited by others discussing his discovery of Crusader-era weapons.

In both passages, the reported inscription includes the phrase “Vivat Husar”Footnote 12 and a reference to a Stephen Báthory. In fact, Báthory is the family name of a line of Hungarian nobles, who rose to prominence in the 1400s. The inscription likely refers to the most famous of the family’s Stephens, who was a prince of Transylvania and a king of Poland (1533–1586) (Encyclopedia Britannica Online 2018), well after the Crusades ended.

We can forgive the 27-year-old Zisserman his wishful thinking and for not having the resources to research the Báthory line. More problematic is that in order to make his speculation sound more credible, he seems to have exaggerated the inscription’s frequency. No other visitor to Khevsureti has recorded it. Unable to find it, Busch (Reference Busch1906, 224) writes, “On the swords I could decipher only two words: ‘Ducat rex …’, on another stood: ‘S. D. Venetiae,’ on a third was only the date ‘1715.’” It is here that Zisserman seems to have prevaricated. By recording only a Crusader-sounding Latin inscription and intimating (but not actually stating) that it covered many Khevsur weapons, he created the impression of a mass of weaponry, suggestive of a single common pathway: a Crusader event.

In fact, Khevsureti was full of old weapons from different places, many of which can be viewed today in the Georgian National Museum. If not so preoccupied with Crusaders, Zisserman might have made interesting inductive points and helpful notes. Makalatia ([1930] 1984, 61, 70), for example, uses the preponderance of old weapons to illustrate his observation that Khevsurs had little use for money and that if a Khevsur man were to get hold of any, he would spend it all on the carpets or weapons from the lowlands that brought with them respect and influence. E.G. Astvatsaturyan (Reference Astvatsaturyan1995, 136) offers detailed descriptions and photographs of many weapons from Khevsureti and includes examples of old Russian and Iranian swords found in the region. In the end, the only specific detail offered by Zisserman—the inscription which has since been repeated in every sympathetic occurrence of the Crusader story—turns out to be, at best, immaterial.

Geographer N. A. Busch: The Only Other Scholarly Treatment

Finding even a few serious academic treatments of the Khevsur-Crusader origin story is difficult. The popularly cited Halliburton and Nussimbaum (Bey) were commercial storytellers prone to invention and hyperbole and who offer no sources or evidence. Neither Ross nor Taitbout were Caucasus scholars, and both merely mention the story in passing as a curiosity and matter of hearsay. Of those 20th-century scholars who mention the idea, Makalatia, Radde, and Grigolia all thoroughly reject it. More recent scholars who have written about the region, such as Georges Charachidze (1968), Kiknadze (Reference Kiknadze2009), and Tuite (Reference Tuite2004, Reference Tuite, Tandaschwili and Pourtskhvanidze2011), do not mention these supposed Crusaders at all. Manning (Reference Manning2010, Reference Manning2015) discusses it only with disdain and frustration. Finally, while Kurtsikidze and Chikovani harbor a fondness for the tale and use it as a unifying theme in their Ethnography and Folklore of the Georgia-Chechnya Border (2008), as early as 2002 even they say that “this theory, of course, cannot withstand academic criticism” (Kurtsikidze and Chikovani Reference Kurtsikidze and Chikovani2002, 34). In sum, only two semi-scholarly works argue in favor of a Crusader origin: Zisserman in 1851 and Busch in 1906. Both writers qualify their historical speculations with much uncertainty. As we have already dealt with Zisserman, Busch is the final loose end.

As noted above, Busch’s (Reference Busch1906) account appears in the German geographical journal Dr. A. Petermann’s Mitteilungen. The passage reads:

Since almost every Khevsur has to contend with others thanks to hereditary blood-revenge, everyone carries weapons with them. In addition to the usual weapons of the Caucasian mountain people—the dagger and sometimes shotgun—they very often have a complete knight’s equipment—armor, shield, helmet, sword and gloves. It is obviously ancient. The owners value it highly, and it is inherited from generation to generation.

On the swords I could not decipher but two words: “Ducat rex …”, on another stood: “S. D. Venetiae,” on a third was only the date “1715.” Evidently these swords are of West European origin. Because of these swords and the particular cross-worshiping, some researchers (Zisserman) believe that the Khevsureans are of a largely Georgian [sic Footnote 13] origin, that their ancestors took part in the Crusades, and sought refuge in this rocky, remote area after failing, and now have become quite wild. Whether these ideas are correct, remains questionable. Radde thinks they are unlikely

(Busch Reference Busch1906, 224).Busch was on good ground up to this point. His account includes new details, including inscriptions he saw on swords. He echoes Makalatia ([1930] 1984) on the point that Khevsurs had a great fondness for weapons for protection and as symbols of prestige. He also mentions Zisserman’s speculation and Radde’s (Reference Radde1878) summary dismissal. Yet (as if unable to help himself!) at the end of his discussion, he adds in a footnote: “I am far from deciding this question and I only wish to express my personal opinion… . I would like to go even further and assume that among the Khevsur people were Germans, for example refugees from the Crusaders. In addition to the knight's equipment, 1) the presence of tall blond men among them speaks for it; 2) the crucifixion and its venerations, which are reminiscent of Catholic usage; 3) the sacred beer, which is otherwise quite foreign in the Caucasus; 4) the goblet in which are engraved gothic buildings” (Busch Reference Busch1906, 224 n. 1).

These points are not difficult to answer. Being tall or blond are obviously not exclusively German traits, and in any case, old photographs of Khevsurs do not bear out this observation. Little can be said about the uses of crucifixes, as he gives no examples, except to point out that, of course, the Georgian Orthodox tradition also includes “the crucifixion and its venerations.” As for goblets with Gothic buildings, if indeed Busch had uncovered any German medieval relics, it is unreasonable to suppose they were taken to Khevsureti by Germans 600 years prior who then became ancestors of the locals.Footnote 14

Grigolia (Reference Grigolia1939) also takes up Busch’s account and dismisses these first three evidences as so nonsensical as to be not worthy of comment. For Grigolia, only one point made by Busch rose to the merit of being falsifiable: that the Khevsur tradition of brewing beer pointed to a possible historical connection between the Khevsurs and the Germans, another beer-brewing people. To answer this Grigolia (Reference Grigolia1939, 10) simply points out that even if indeed the Khevsurs’ knowledge stretched back to the time of the Crusades (and there is no reason to think it did), beer brewing was already practiced in the Caucasus region and so is in no way suggestive of German transplants.

These points hardly need to be stated. What is most interesting about this passage is simply that after a cursory, reasonable discussion of the issue, Busch’s imagination was helplessly ambushed by the Crusader meme in a footnote. Suddenly it as if he glimpse traces of Crusader knights everywhere he looks.

The Khevsurs’ Traditional Origin Story is Meaningful and Plausible

Several versions of the Khevsurs’ traditional origin story have been recorded. This example is from Eristavi:

A long time ago, a peasant from a Kakheti landlord, a resident of the settlement of Magrani, having committed offense against his master, fled to the Pshavi Gorge and settled in the town of Apsho. Here he lived and hunted animals with his son barely able to support his family. One day his son went far beyond their lands up into the gorge, to where now sits the village of Gudani, and here he killed a wild goat. His father, upon seeing how fat it was, turned to his son with these words: “My son! This land we live on is poor and does not reward our labors. These mountains are barren and empty and the do not produce grasses. Let us leave this rocky place and settle to the place where you hunted. Where a goat could become so fat, at such a place a person can also live.”

His son was however was partial to the beautiful surroundings of Apsho. He had become attached to this region and so met his father’s suggestion with silence. “I see, my son,” the old man continued, “that you are torn. You do not want to leave your home in Apsho, but you see how difficult it is for us to live here.” Then the old man gave his son a bag with wheat and said: “Go, sow this wheat where you killed the goat and we will make our decision based on what happens.” The son did as he was told, and the harvest was extraordinary. From a handful of wheat they received a full bag, and so they decided to move there, calling this place Gudani. Here God gave the son two children: Araba and Ch’inch’ara who became the clans of Arbauli and Ch’inch’arauli (Eristavi Reference Eristavi1855, 80).

Similar accounts are found in Makalatia ([1930] 1984, 72) and Zisserman (Reference Zisserman1851, Reference Zisserman1876). Other versions include a third son, Gogoch’uri (see Tedoradzei 1930). Both versions are found in Kiknadze (Reference Kiknadze2009, 15–18), a collection of examples of Khevsureti folklore as told by locals.

Zisserman’s worst moment may be when he suppresses the folkloric Khevsur tradition to promote a pet Crusader speculation. He writes, “[My Crusader] hypothesis, which is not any less strange [than the Khevsurs’ own origin story], serves to explain the close similarities between the manner of dress and armament of Khevsurs and the Crusaders” (Kavkaz, March 20, 1851).

Contrary to Zisserman’s suggestion, it would be hard to invent a more genuine-sounding origin story than that found in the Khevsur tradition. It not only roots Khevsur identity in upland agriculture, hunting, independence from lowland barons, and Khevsureti itself, but it also tracks geography, history, tradition, and even the livelihood constraints that play into migration patterns. This folklore also conserves the historical fact that the Khevsurs and the neighboring Pshavs were originally one and the same, inhabiting a region known as Pkhovi, now separated into Khevsureti and Pshavi (Makalatia [1930] 1984, 22).

The Crusader Invented History and Implications for Ethnicity

The Khevsur-Crusader fiction is not simply a fantastic tale conjured from thin air and retold by the credulous. On the contrary, these misinterpretations draw heavily on established themes in the context of a loaded history.

The silhouette of such a knight on the Chechen border with Frankish sword raised echoes a dialectic between Islam and Christianity and between the East and West that Georgia has long lived out. With its long history of incursions by the Ottoman empire and the dynasties of Iran, Georgia is often depicted as one of the oldest and most resilient Orthodox countries. The impulse to mythologize Khevsurs as holy protectors of the north is a continuation of this narrative, overlapping with 19th-century Russia campaigns to subdue Muslim highlanders, often via its “Orthodox protectorate” Georgia (Rayfield Reference Rayfield2012, 256).

As Manning (Reference Manning2010, 416–417) notes, this historical opposition seems to be what Kurtsikidze and Chikovani (Reference Kurtsikidze and Chikovani2008, xi) have in mind when they portray the Khevsurs as distinguished by a “local version of a war ideology” as lived out on the border of Chechnya. Elsewhere, Chikovani goes so far as to assert that the “customs, institutions, and mythology” of the Khevsurs were shaped after the 11th century “under the influence of pro-crusade politics” (Chikovani Reference Chikovani2004), although he provides no references.

Sourcing worries aside, Kurtsikidze and Chikovani’ Crusader connections are reminiscent of important historical sources. For example, the Georgian Chronicles (1955) directly connect the flourishing of the Golden Era under King David the Builder to the weakening of Georgia’s oppressors during the First Crusades: “During this time, the Franks took Jerusalem and Antioch, and by the help of God, the country of Kartli [East Georgia] flourished. David became stronger and multiplied his army. He ceased paying tribute to the Sultan and the Turks were no longer able to winter in Kartli” (Georgian Chronicles 1955, 210). Even more on point, historians of the time Matthew of Edessa and Walter the Chancellor both mention Crusaders being present at the famous Battle of Didgori near Tbilisi in 1121, where King David the Builder won a decisive victory for Georgia against the Seljuks and Persians (Tinikashvili and Kazaryan Reference Tinikashvili and Kazaryan2014, 33–34). Especially relevant are the efforts to Christianize the Kartvelian highlanders, which was in part based in the Georgian palace’s need to establish a shared ideology with the Khevsurs to secure their northern borders which were constantly vulnerable to raids by tribes professing Islam from the Northern Caucasus (Gogochuri Reference Gogochuri2013, 31).

European Ethnicity Projected into Georgia

We should vigorously resist calling the Crusader meme a myth or a legend. It is neither. This story does not derive from meaningful traditions or old stories playing important roles in cultural heritage and identity. The mythic quality attributed to the Khevsur-Crusader fiction is itself part of the fiction and a feature of a meme attempting to connect medieval Europeans to ancient Georgia.

This fiction is not the first time European pseudoscience and storytelling has felt compelled to link European and Georgian ethnicities. Thanks to another much broader attempt, we owe the continued existence of the regrettable racial category “Caucasian.” This classification was popularized by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840) in his essay “On the Natural Varieties of Mankind” (Blumenbach [1775] 1865), which saw several editions and expansions from 1775 to 1795. A well-received publication in its time, this essay asserted it was possible by a comparison of skull shapes to trace the origin of humankind to that “most beautiful race of men” with “the most beautiful form of the skull” on the southern slopes of the Caucasus (Blumenbach [1775] 1865, 296). Blumenbach’s conjecture was in harmony with accepted wisdom that held that Noah’s son Ham wandered south with his cursed son to become the father of Africans,Footnote 15 while Noah’s son Japheth tended north from Ararat toward the Caucasus and became the father of the Europeans.Footnote 16 As early as the 5th century, the most revered scholar of the ancient west, Saint Isidore of Seville (ca. 560–636), commented on the popularity of these biblically informed global migration schemes, noting the direct line often drawn from Japheth’s son Magog to the Goths (Isadore, IX.ii.89; Trans. Barnet et al. 2006).

These pre-medieval and medieval suppositions persisted through the Renaissance and into the modern era, such as in John Thomas Painter’s influential 1880 book Ethnology: Or the History & Genealogy of the Human Race, which explains global racial distributions with Noetic genealogies and tracks the movement of Japheth’s offspring north from Noah’s Ark’s resting place on Mount Ararat. Likewise, linguistic giants such as the Welshman William Jones (1746–1794) and the Danish Rasmus Rask (1787–1832) adopted the label “Japhetic” to designate what is now called Proto-Indo-European, taking their cue from the terminology of Leibniz (1646–1716) and Theodore Bibliander (1504–1564), all in deference to a mythical Japheth said to be the progenitor of Europeans.

The Khevsur-Crusader Fiction as a Mostly Harmless Invented History

The Khevsur-Crusader fiction stands out as a typical example of an invented history based in pseudoarchaeology. While modern archaeology proceeds by consolidating information and artifacts into bodies of evidence to interpret, pseudoarchaeology relies on the persistent popular perception of archaeologists as itinerant discovers of the past. As a methodology, pseudoarchaeology proceeds by employing old, outmoded approaches and a presentation of materials that emphasize enigma and cryptic artifacts, often ignoring or disparaging contemporary scholarship to bolster their problematic claims (Card Reference Card, Card and Anderson2016, 19–21). According to Holtorf (Reference Holtorf, Petersson and Holtorf2017, 177), the common denominator between former modes of archaeology and present-day pseudoarchaeology is a subjective epiphanic experience of excitement that acts as a validating criterion. He calls this the “visceral sensation in the stomach.”

Indeed, the office of the archaeologist has been fixed in the popular imagination as an oracle of mystical secular authority. My earliest recollection of this phenomenon is from the 1990s in my favorite childhood computer game. The pixilated archaeology professor, Indiana Jones, is shown struggling through a throng of anxious students to his office door. Once safely inside, the player is able to wander around the fantastical chambers, examining ancient tablets and stones, crystal shards, a meteor oozing purple slime, a totem pole from a Brazilian tribe, and a mask given to the professor by an African shaman near Kinshasa.

The pseudoarcheology in the Khevsur-Crusader fiction reaches a degree of fantasy on par with Dr. Jones and his otherworldly office. Here we find scientifically-minded explorers, our Zissermans and Halliburtons, penetrating isolated realms and discovering obscure mysteries in the cryptic images and writings on ancient armor, swords, symbols, and vessels. This romance has been since snatched up by purveyors of fantastic facts, from newspaper editors to Internet bloggers and has served to activate the “visceral sensations” of the stomachs of readers for more than a hundred years.

Yet Holtorf (Reference Holtorf, Petersson and Holtorf2017, 177) cautions us that before we condemn this fiction masquerading as fact too harshly, we should understand that this sort of romanticizing is a natural and even necessary stage toward more mature approaches. As even Edward Said (Reference Said2003) points out, “all” representation involves a slanting, a reinterpretation, and an inevitable distortion. He continues: “There is nothing especially controversial or reprehensible about such domestications of the exotic; they take place between all cultures, certainly, and between all men” (Said Reference Said2003, 60).

Here the insights from the philosopher James O. Young are useful. In his book-length analysis of cultural appropriation, Young (Reference Young2008, 114) argues that subject matters are not something one can own, nor should we want them to be. On the contrary, if we truly wished to maximize the principle that only members of a particular culture can write and represent that culture, all other representations being egregious thefts, we would have to throw out most of our cannon, cancel our Netflix subscriptions, and make sure any music we enjoy is played by musicians of the same cultural background as the composer. While subject appropriation may sometimes be problematic, for example by reinforcing negative stereotypes, it is not appropriation of subjects itself that is causing harm.

Yet some instances of cultural appropriation are profoundly offensive, continues Young (Reference Young2008, 134), when the representation occurs against a background of real harm. These sorts of offensives occur in the context of a much greater theft, an oppression, a genocide. In turn, it is the cavalier attitude and ignorance of those who would wear headdresses or continue to profit from destroyed Native American sites (such as Manitou Cliff Dwellings) that should bother us. That is, we should take issue with these instances of cultural appropriation because they are symptomatic, and we have deep moral concerns about the situation as a whole.

This brings us to the critical differences between the Crusader fiction and more problematic examples of cultural appropriation. The Crusader fiction is not an affront to ethnicity because (1) it does not line up, support, or lend credence to dominant narratives that might seriously undermine Khevsur ethnicity as Kartvelian; (2) it does not generate or maintain stereotypes that operate in a larger framework of subjugation; and (3) it is not reminiscent of the negative portrayals of Georgians used by dominant cultures to justify inflicting harm on Georgia.

While it may be frustrating because of its silliness and persistence, the Khevsur-Crusader story is not without its perks: (1) it provides us with a historic example of how easily misconceptions can spread; (2) it helpfully illustrates the natural propensity of people to romanticize other cultures in an instance that can be easily disproven; (3) it encourages us to reflect on our own propensity to be captured by the imagination, saving us future mistakes and embarrassments; and (4) when properly presented as European fantasy, it offers an instructive contribution to possible future programs of meaningful cultural heritage interpretation about Khevsureti.

Conclusions: How the Khevsur-Crusader Meme Spreads

The Internet contains a growing string of blogs, threads, and comments from people whose imaginations have been ambushed by the story of a lost band of Crusaders in the Caucasus. Most examples follow a similar pattern: they encounter “the legend” (often in an old copy of Halliburton), excitement builds, cursory research follows, the same exotic 19th-century portraits of Khevsurs wearing chainmail are found, and finally they read excerpts of the authoritative Zisserman, feeling they have stumbled upon an old mystery. Inevitably, the post or advertisement ends with something like, “No one knows for sure. We may never know—yet in every legend, is there not some grain of truth?” As Halliburton (Reference Halliburton1935a, 210) writes: “No historian has found any reason to believe that the legend is not based entirely on fact.” In his account, Ross (Reference Ross1918, 65) captures the same ambush of the romantic perfectly: “A jewel of a story that! How it fires the imagination!”

This article has gone to great lengths to deconstruct and discredit every aspect of this fiction, yet it should be emphasized that there was never good reason to give it any credit in the first place. The story that a lost band of Crusaders has inhabited a corner of the Caucasus for centuries is so curious and compelling for many that the very hope that it might be true becomes an unconscious principle by which material is selected, combined, and organized. Even once thoroughly disproven, the illusion itself seems to remain intact, floating unaffected above reality.

Consider this counterfactual scenario: a historical source emerges this year showing that in the 11th century a Crusader knight did indeed end up in Georgia and settled in the mountains in Khevsureti. Does this mean anything? Does it constitute new evidence to help support Zisserman’s Khevsur-Crusader origin theory? The answer is no. The evidence put forward by Zisserman or any of the other writers remains immaterial. The strength of the illusion itself is revealed in a feeling this new source somehow would have to be connected to the Crusader story somewhere in the black box of history.

In an illustrative example of the adaptative nature of memes, Internet discussions now cite for support the medieval historians Matthew of Edessa and Walter the Chancellor who briefly mentioned the presence of a few Crusaders in Georgia. This “new” detail has attached itself to and spreads with the meme, adding another immaterial piece of evidence which contributes to the meme’s survival. We can answer this new worry just as easily: true, it is not impossible that a Crusader ran up into the mountains and settled there, just as anyone else in Georgia at the time might have done so. But there is no reason to suspect this in the first place. This is the problem with trying to disprove wishful thinking: it generates its own ad hoc evidence rather than being based on evidences. In this case, the wishful thinking hidden in the illusion is what makes this historical proximity and possibility seem relevant, and that is all.

Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene ([1976] 2006) coined the term “meme” to describe how ideas, like genes, pass themselves from one vehicle to another, beating competing memes, growing more resilient through adaptation, and spreading throughout a population. In this model, the human mind is the medium of the meme, which works backwards, subtly selecting or rejecting ideas, facts, or rumors, and making connections at points of coincidence. In the case of the Khevsur- Crusader meme, this is experienced in the vehicles as an ambush of imagination. In a sense, it is the story itself that “sees” evidence of a Crusader ancestry in incidental Latin phrases, armor, beer, religious symbols like crosses, overheard words believed to be French or German, engravings on goblets, or tall, blond men.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks go to Maia and Davit Tserediani, Alexander Bainbridge, Paul Manning, Arthur Bright, Timothy Blauvelt and the attendees and organizers of the Works-in-Progress Series in Tbilisi, and Artur Gorokh for their help with source materials and comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.