Relatively little work has been done on comparing the effects of religion and ethnicity on group behavior, apart from their simple juxtaposition (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2013).Footnote 1 Ethnicity, as common ancestry and language-based identity, and religion are often so intertwined that they are assumed to have the same effect on groups (Barth Reference Barth and Barth1969; Rothschild Reference Rothschild1981).Footnote 2 Ethnicity, for example, has been defined as an umbrella identity that includes “color, religion, language, or some other attribute of common origin" (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, 41). Identity is situational, as individuals choose to affiliate with specific identities in particular contexts (e.g., during war or heated political competitions; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2008).

Recent research at macro and micro levels of analysis suggests that ethnic and religious identities sometimes compete, clash with each other, and have distinctly different social manifestation patterns. Ethnicity and religion may have a substantively different impact on individual and group behavior, depending on exogenous triggers for each type of identification (Moskalenko, McCauley, and Rozin Reference Moskalenko, McCauley and Rozin2006; McCauley Reference McCauley2014; Siroky, Mueller, and Hechter Reference Siroky, Mueller and Hechter2017). Some researchers have argued that religious cleavages are more likely to cause intrastate conflict and persist throughout it (Juergensmeyer Reference Juergensmeyer1993; Laitin Reference Laitin2000; Toft and Zhukov Reference Toft and Zhukov2015), while others showed that language cleavages are more likely to do so (Bormann, Cederman, and Vogt Reference Bormann, Cederman and Vogt2017). This study strives to elucidate the differential effects of ethnic and religious components of cultural identities based on the social roles of ethnicity and religion.

Building on previous research on group solidarity, religion and ethnicity (Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Hechter Reference Hechter1978, Reference Hechter2000; Olson Reference Olson1965; McCauley Reference McCauley2014; Zolberg and Woon Reference Zolberg and Woon1999), this article strives to provide a novel, parsimonious explanation for the identity choice of individuals and formation of cultural groups. The theory emphasizes three primary factors that explain the logic of individual membership in religious and ethnic identity groups: economic status of the individual, the social role of the cultural group, and the number of available ethnic and religious identity slots in the society.

It has been noted that industrial societies tend to have a cultural division of labor (CDL), whereby social groups defined by common religious and ethnic identities, or a combination of both, acquire occupational specialization (Hechter Reference Hechter1978; Olzak Reference Olzak1983; Onokerhoraye Reference Onokerhoraye1977; Wright and Ellis Reference Wright and Ellis2000). Ethnicity is, on average, a more numerous grouping category than religion. For example, there are more languages in the world than religions.Footnote 3 This makes the language marker more suitable as the principle of distinction for establishing and maintaining a cultural division of labor in society. Religion is less useful as an identity marker for a cultural division of labor than language because the number of religions is far smaller than the number of ethnic groups. Therefore, religion is also less likely to serve as a base for organizing economic life than ethnicity inasmuch it concerns functional economic collectivities. If religion is associated with economic life to a lesser extent than ethnicity, religion-based groups should be able to accommodate a greater variation of incomes among its members than ethnicity-based identity groups.

Besides structural and rational choice factors, ideological factors play a role. Religious scriptures provide the basis for toleration of income inequalities and support for the poor, while ethnic myths emphasize the unity of the ethnic group and the equality of its members.

The case of the Russian North Caucasus presented here is illuminating because the region has a variety of ethnic groups and religions. The region also transformed from the dominance of ethnic identities in the 1980s and 1990s to the rise of religious identities from the 2000s onward. The variation of identities and rapid changes in the region provide an appropriate venue for the study of the interaction of ethnic and religious identities.

The Competition of Religion and Ethnicity

When societies move past the agrarian stage, individuals start specializing in their economic activities (Durkheim [1893] Reference Durkheim1960). The rise of cities where people go for work means that different cultural groups intermix (Gellner [1983] Reference Gellner2008). In some societies, occupation and economic status become tied with the ethnic identity of individuals (Hechter Reference Hechter1978). I argue that when such specialization happens and both ethnic and religious identities are present, individuals are more likely to organize their economic activities along ethnic lines than religious lines. This happens because, on average, there are more ethnic group slots available than religious slots. As a marker for distinguishing in-group individuals from out-group individuals, ethnicity is more functional than religion in most cases (Bourdieu and Nice Reference Bourdieu and Nice1987).

The association of economic activities with ethnic group membership leads to greater emphasis of members of such groups on income equality. The occupational character of ethnic groups presumes a relatively high level of in-group equality to avoid the free-rider problem (Olson Reference Olson1965).

Due to their association with material activities and emphasis on equality, ethnic identity groups are most likely to lose their members from both ends of the income spectrum. The least affluent and the most affluent individuals will respectively be excluded from ethnic, occupational organizations or choose to distance themselves from them.Footnote 4 The excluded and self-excluded individuals are likely to flock to religious solidarity groups, which serve as an alternative to ethnic identity groups. Religious groups reduce individuals’ uncertainty in the complex social world in much the same way as ethnic groups do and can provide a support framework for the individuals in the societies where the state is relatively weak (Corstange Reference Corstange2012; Hale Reference Hale2008; Wickham Reference Wickham2002).Footnote 5

Religious groups tend to be more inclusive than ethnic groups, partly because their ability to exclude individuals is limited relative to ethnic identity groups.Footnote 6 Ethnicity-based occupational groups usually require individuals to be born into a group, which limits the pool of possible members of such groups, while religious groups, in many instances, accept conversion. For example, there are clear procedures for religious conversion, while ethnic assimilation is usually a much less formalized, lengthy, and arduous process (Chiswick Reference Chiswick2009; Walters, Phythian, and Anisef Reference Walters, Phythian, Kelli and Anisef2007).

Religious groups provide more inclusive membership criteria that attract less affluent individuals who are excluded from ethnic solidarity groups based on their low-income statuses. Individuals from the high-income strata are attracted to religious groups by the relatively low demand for income equality among the group members and by group benefits at a relatively low price. In democracies, the religious rich tend to form coalitions with the religious poor. The former category gains lower taxes and the latter gains greater redistribution while the nonreligious poor are excluded (Huber and Stanig Reference Huber and Stanig2011).

Moral and psychological components also play a role. For an affluent individual, it may be easier to contribute to an idealized abstraction rather than to the fellow coethnic who is often far from being an ideal person (Shariff and Norenzayan Reference Shariff and Norenzayan2007). To the poor, religion offers immaterial solace through well-developed doctrines, which ethnic groups normally lack.

Cultural division of labor (CDL), whereby division of labor in the multicultural society happens along ethnic division lines, is often attributed to immigrant societies, where CDL is a reaction of an excluded minority to discrimination and a way of promoting in-group solidarity. Empirical research suggests that some level of discrimination based on cultural differences is inherent even in advanced democracies (Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010; Feldman Reference Feldman2018; Wright and Ellis Reference Wright and Ellis2000). In this study, I make more general use of CDL theory to include cases in which ethnic and economic identity groups form due to the presence of multiple ethnic identity slots and few religious ones. Rather than being conflictual and adversarial, I suggest the division of labor happens naturally due to demographic conditions and individuals’ needs for distinct identities (Bourdieu and Nice Reference Bourdieu and Nice1987).

This line of argument does not imply that transition is possible only from ethnic group affiliations to religious group affiliations. The example of the Russian North Caucasus suggests that the salience of religious and ethnic identities depend on the degree of the economic inequality in society.

In the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, the North Caucasus was known as a territory where ethnic cleavages manifested themselves in violent conflict. Various secessionist movements that sought congruence of ethnic settlement areas with national borders spread across the region. Most researchers have focused on the Russian-Chechen wars in 1994–1996 and 1999–2000 (Schaefer Reference Schaefer2010). However, there was also a short Ossetian-Ingush armed conflict in 1992 and many other ethnicity-based violent conflicts in Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachay-Cherkessia.

As the 1990s ended and the 2000s ensued, ethnic identities became less salient and conflicts less frequent in the North Caucasus. This process coincided with the rise of religious identities in the region. Existing nationalist conflicts, such as the Russian-Chechen conflict, transformed into a cleavage with distinct religious overtones, which then spread to other republics of the North Caucasus (O’Loughlin, Holland, and Witmer Reference O’Loughlin, Holland and Witmer2011). The rise of religion also manifested itself in the number of newly built mosques, churches, and temples (Nichol Reference Nichol2011). State officials paid tribute to the new trend by aligning with one or another religion. The government designated traditional and nontraditional religions, supporting the former and suppressing the latter.

The shift from ethnicity-based to religion-based affiliations coincided with the great economic transition in the North Caucasus and across Russia—from the socialist economic model to capitalism. A rapid rise of economic inequalities in the society ensued. This signifies a possible link between economic redistribution and salience of identities. It appears that ethnic identities are the strongest when there is relatively little economic inequality in the society, and they tend to crumble when inequality grows, which is consistent with the expectations laid out in the extant literature (Hechter Reference Hechter1978). As ethnic identities decline in power, however, religion becomes more salient, and some division lines in the society are reconfigured along religious affiliations.

Member Discrimination in Ethnic Groups

Ethnic mobilization was a widespread phenomenon across the North Caucasus in the 1980s and 1990s. Most ethnic groups had organizations that purported to represent them. Apart from violent clashes, representatives of ethnic groups often engaged in public protests and other collective actions (Lankina Reference Lankina2006). Both violent and nonviolent conflicts during this period took place between different ethnic groups. As economic inequality became more evident in the North Caucasus, infighting within ethnic groups became more frequent, while conflicts between ethnic groups decreased.

Members of ethnic groups in the North Caucasus are normally defined by language. Unlike ethnic groups in the Balkans, for example, religion is not a defining factor for any indigenous ethnic group in the region. Some ethnic groups in the area have traditionally been subdivided along religious lines, such as Abkhazians, Kabardins, and Ossetians (Gammer Reference Gammer2007). Other groups have become religiously more fragmented recently due to proselytism of Christian and Muslim groups, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses in Dagestan (Magomedov Reference Magomedov2019).

A person instantly becomes a member of an ethnic group based on the family and language group that a person is born into, not based on the income that they will earn as an adult. However, as an adult, the person might belong to an ethnicity-based occupational group or fall out from it and join, for example, a religion-based group. Also, membership in both types of groups simultaneously might happen, which will be discussed later.

As economic inequality spreads within the ethnic group, its solidarity usually drops (Hechter Reference Hechter1987). Ethnic groups should display stronger selection bias and preferences for individuals within the existing pool of potential members, thus turning into collectivities of ethnic occupational groups. The amount of resources a potential member can contribute to the group is likely to determine how valuable they will be considered by the group.

Ethnic identity groups put an especially strong emphasis on the equality of all members of the group for two main reasons, ideological and material. The ideological foundation for the demand for material equality within the ethnic group comes from the belief that all members of the same ethnicity have the same ancestry. Fictive kin ties inspire group members to assist each other in finding jobs, granting slots in educational institutions, and providing all manner of in-group privileges and exceptions, while denying the same to out-group individuals. The actual or imagined common ancestry is often cited as a key element of ethnic identity in the literature (Chandra Reference Chandra2006; Wimmer, Cederman, and Min Reference Wimmer, Cederman and Min2009). Derivation from the same ancestor presumes equality among the members of the group and implies that ethnic solidarity groups should put a high premium on in-group equality compared to religious groups.

The material reason for higher equality among groups that emphasize ethnic identity is informed by the way CDL operates. If the work activities of individuals are organized along ethnic lines, members of such networks are likely to, (1) value the ethnic principle of association and (2) be especially sensitive to income inequality within their networks as a way of avoiding the free-rider problem. The second proposition suggests that poorer coethnics, who cannot participate in these networks with their own capital, superior work skills, or other valuable resources, will be excluded through the policy of not employing them and refusing to have business with them. The more affluent coethnics will choose to leave such networks because of the excessive demand for equality in the close-knit collectivities of individuals that are geared toward receiving material gain. Exclusion from ethnic solidarity groups will not necessarily mean exclusion from the ethnic group as such. Rather, it will mean the exclusion of the poor and the departure of the rich from ethnicity-based economic (and some other social) activities.

While in some societies this process might take generations, in the Russian North Caucasus it was accelerated by the rapid transition from the socialist command economy to a capitalist market economy in the 1990s. Fast economic changes made the downfall of ethnic solidarity groups and the rise of religious solidarity groups more easily observable.

Both Christians and Muslims often emphasize the supra-ethnic nature of their religions, attracting the poor and the disenfranchised individuals from various ethnic groups along with some rich people.Footnote 7 The larger the group, the greater the material inequality in it becomes, thereby reducing the group’s ability to provide “an optimal amount of public good” (Olson Reference Olson1965, 35). This notion implies that ethnic occupational groups that are organized for material gain should be relatively small.Footnote 8

This discussion leads to my first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The relationship between personal income and the likelihood of affiliation with the ethnic identity will be concave: individuals with middle income will be more likely to affiliate with the ethnic group than individuals in the lowest and the highest income categories.

Religion and Ethnicity

Religious groups are less discriminating against people on the basis of their low personal income than ethnic groups. At the same time, wealthy individuals may feel more protected in a religious group than in a group that emphasizes ethnicity because religion is more tolerant toward inequality between its members than ethnic groups (Botero et al. Reference Botero, Gardner, Kirby, Bulbulia, Gavin and Gray2014; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2013). Besides, the rich who contribute to the religious organization receive something in return for their contributions, such as the promise of salvation. In ethnic groups, the immaterial benefit of contributing is much less formalized and conceptualized. Religious groups can also outcompete ethnic groups in terms of having greater group solidarity because of claiming high moral ground.Footnote 9

Another reason for the rich individuals to join religious groups may be related to the demand for social order (McGuire Reference McGuire2008). When the state is weak, the protection of individual wealth and an elevated social status becomes an important motivation for the individual’s choice of group identity. Affiliation with an ethnic group only protects the person within one’s ethnicity-based organization or wider ethnic group. Affiliation with a religious identity provides protection for the individual among a larger number of people and groups and may be preferable to wealthy individuals. Personal protection is especially relevant under the conditions of the secular state that cannot reliably uphold social order.

The Russian state in the North Caucasus and elsewhere in the periphery was relatively weak in the 1990s. This is also the period when regions enjoyed the highest degree of autonomy. Chechnya was a quasi-independent country before the war with Russia that started in 1994 and during the interwar period in 1996–1999. In the 2000s, the situation started to change as the policy of centralization ensued in the country. It was partly due to the growing revenues of the Russian state, which allowed Moscow to improve the financing of the central government, provide incentives for the regional authorities, and strengthen control over them.

Despite the increased state capacity, affluent individuals still faced numerous security risks in the North Caucasus. In particular, news reports about the extortion of money from businesspeople and government officials by Islamist insurgents were common (Fuller Reference Fuller2013). One way for vulnerable individuals to defend themselves was to associate with a strong religious group and religion in general, as shariah courts proliferated (Comins-Richmond Reference Comins-Richmond2004; Bobrovnikov Reference Bobrovnikov2000). For the poor, religion also provided some protection against the powerful and charity handouts (Yemelianova Reference Yemelianova2014).

This is not to say that religion is antithetical to economic activities. Some researchers have explained the historical rise and spread of Islam, in part, by the ability of its adherents to mitigate social tensions between unequal societies and facilitate long-distance trade (Michalopoulos, Naghavi, and Prarolo Reference Michalopoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo2012; Michalopoulos, Naghavi, and Prarolo Reference Michalopoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo2016). Religious rich and poor may also join forces for electoral victories in pursuit of lower taxes for the rich and greater redistribution toward the (religious) poor (Huber and Stanig Reference Huber and Stanig2011). Again, this symbiotic relationship ties together religious rich and religious poor, leaving out the middle-income individuals.

Compared to ethnic groups, religious groups have two primary advantages, ideological and material, which allow religion to accommodate the interests of individual members with disparate income statuses. Religious groups have, on average, a much stronger ethical basis than ethnic groups. Ethics are literally enshrined in the holy texts. Faith helps to overcome the free-rider problem among religious groups (Warner et al. Reference Warner, Kılınç, Hale, Cohen and Johnson2015). Religions tend to proclaim the protection of the poor as one of their objectives, but they also accept material inequality. The spread of moralizing religions has been shown to coincide with harsh climatic conditions, which indicates the importance of ethical and group solidarity component in the advent of religion (Botero et al. Reference Botero, Gardner, Kirby, Bulbulia, Gavin and Gray2014).

Ethnic groups rarely have specific texts that provide moral guidance to the group members and exercise authority over them, although they might have unwritten codes of conduct. Lack of authoritative texts is more evident in ethnicity-based occupational organizations that focus on performing relatively limited day-to-day economic operations. Receiving material benefits and solace from religion motivates the poor (Immerzeel and Tubergen Reference Immerzeel and van Tubergen2013). The pursuit of social protections for their high social status that the religion offers at a lower price and of wider scope than ethnic groups motivates the wealthy.

The way religious groups are organized explains the material foundations of tolerance of religious groups for material inequality. Religious congregations, as a rule, are not organized for material gain or at least are not associated with daily economic activities. So, members of religious groups are relatively removed from their material interests, while ethnic groups tend to be immersed in such interests. Compared to ethnic groups, therefore, religious groups should have a relatively small proportion of the middle class that will be incorporated into ethnic groups and a relatively large proportion of the poor and the wealthy.

Accordingly, my next hypothesis posits:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between personal income and the probability of affiliation with a religious group will be convex: individuals with the lowest and the highest income will be more likely to affiliate with the religious group than individuals in the middle-income category.

Identities are layered rather than exclusive, and individuals maintain and condition behavior upon their various identities (Kosta Reference Kosta2019). So, a theory on ethnic and religious identities should account for the large pool of individuals with a mixture of religious and language-based identities.

When a society faces an economic crisis, the middle class, the core of ethnic groups, tends to collapse (Lopez-Calva and Ortiz-Juarez Reference Lopez-Calva and Ortiz-Juarez2014). This results in a contraction of ethnic solidarity groups and the expansion of religious ones. Alternatively, the breakdown of ethnic collectivities could also result in the expansion of the state, but economic collapse often means that the state is also not doing well. So, religion is more likely to come to the forefront at the time of economic upheavals (Immerzeel and Tubergen Reference Immerzeel and van Tubergen2013).

It follows that during economic transition times, religion-based groups should have an upward trend, while ethnicity-based groups should have a downward trend. This expectation is consistent with the Durkheimian notion of anomie that reflects the breakdown or significant change of social norms at the time of economic cataclysms (Durkheim [1897] Reference Durkheim2005; Hierro and Rico Reference Hierro and Rico2019).

Theoretical and empirical works suggest that mixed identities will tend to be more like religion-based groups than ethnicity-based groups.

When economies are stable, wealth redistribution is high, and income inequality is low, ethnicity-based groups are likely to have an upward trend and religion-based groups a downward trend. In such societies, mixed groups are more likely to behave as ethnicity-based groups. At times of economic transitions, low wealth redistribution, and high levels of income inequality, religion-based groups are more likely to prevail at the expense of ethnicity-based groups.

Hence, my third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The relationship between personal income and the probability of affiliation with a mixed ethnic-religious group will be convex in societies experiencing economic transition, high income inequality, and low rates of wealth redistribution. Individuals with middle income will be less likely to affiliate with the mixed ethnic-religious group than individuals in the lowest and the highest income categories.

Russian North Caucasus: From Ethnic Revival to Religious Zeal

The demise of the USSR in 1991 and the decline of the central state’s capacity was associated with the rise of the salience of ethnic identities and a series of ethnic and center-periphery conflicts (Zhirukhina Reference Zhirukhina2018). It is important to note that as the end of the union drew closer, the economic equality in the country was relatively high, even though it was far from the proclaimed socialist ideal (Alexeev and Gaddy Reference Alexeev and Gaddy1993; Bergson Reference Bergson1984; Matthews Reference Matthews1985; McAuley Reference McAuley1977). After the breakup of the union state, Russia experienced a massive rise in income inequality (Galbraith, Krytynskaia, and Wang Reference Galbraith, Krytynskaia and Wang2004).

Russian North Caucasus also transitioned from the state of relative material equality to the state of high material inequality. The region is home to dozens of ethnic groups and seven officially designated ethnic republics that are also ethnically heterogeneous. The region long became associated with ethnic and religious tensions in the Russian Federation, but by the time of this study no significant ethnic tensions took place (O’Loughlin, Kolossov, and Radvanyi Reference O’Loughlin, Kolossov and Radvanyi2007).

The largest republic with a single titular ethnicity in the region, Chechnya, proclaimed its independence from the Soviet Union and Russia in 1991. However, the Chechens’ quest for national sovereignty was mired in two bloody wars with the central government in Moscow and was eventually crushed. The Russian government blessed the rule of an authoritarian leader over the restive republic (Souleimanov, Abbasov, and Siroky Reference Souleimanov, Abbasov and Siroky2019). Ethnicity-based movements were not limited to Chechnya. Strong ethnic movements proliferated across the North Caucasus in the 1990s. Strengthening of ethnic identities manifested itself in tensions between ethnic Kabardins and Balkars, ethnic Cherkes and Karachays, and ethnic Ossetians and Ingushes. Multiple conflicts between ethnic and religious groups took place in Dagestan. The ethnically representative republican government became an explicit practice in the largest and the most diverse republic of the North Caucasus, Dagestan (Ware and Kisriev Reference Ware and Kisriev2009).

The political salience of ethnic solidarity groups did not triumph for long, though. By 2007 Chechnya’s nationalist quest for independence transitioned to a religious goal of building an Islamic caliphate across the North Caucasus. The self-styled Islamist organization Caucasus Emirate was proclaimed in October 2007. Apart from the shift in the insurgency movement, the North Caucasus, in general, experienced a decline of politically salient ethnic organizations and the proliferation of religious networks (Dunlop and Menon Reference Dunlop and Menon2006; Sagramoso Reference Sagramoso2007). The construction of mosques, churches, and temples was complemented by the rise of grassroots religious groups (Nichol Reference Nichol2011). Ethnicity-based social and political activism transitioned to religion-based activism in the Russian North Caucasus, which coincided with the spread of income inequality after a long period of moderate income differences.Footnote 10

The relationship between ethnic and religious solidarity groups sometimes turned quite conflictual. For example, Islamist insurgents in the Muslim-majority republic of Kabardino-Balkaria claimed responsibility for the 2010 murder of a well-known Circassian ethnographer and activist, Aslan Tsipinov, who promoted Circassian ethnic values (Fuller Reference Fuller2011a). An Islamic radical in the Muslim-minority North Ossetia murdered an Ossetian poet in 2011 for writing a so-called “blasphemous” poem that sent waves of anti-Islamic sentiment across the republic, creating tensions between the Ossetian ethnic identity and religious identities of Ossetians that include Muslim, Christian, and others (Fuller Reference Fuller2011b). Ethnic and religious identities do not always and necessarily clash, but signs of competition between the two are easy to detect in the North Caucasus.

A cultural division of labor is especially evident in some parts of the North Caucasus. Dagestan is the republic where an ethnic division of labor is arguably most evident, probably because the territory is the most ethnically diverse place in the North Caucasus. Dagestan is a territory with largely Muslim population and dozens of distinct languages. Muslims are not monolithic in Dagestan or the wider North Caucasus. For example, there are competing Islamic juridical schools and teachings (Yemelianova Reference Yemelianova2001). Still, the number of religious teachings arguably is smaller than the number of tongues (Catford Reference Catford1977). So, ethnicity (language), not religion, plays the role of a distinctive marker when it comes to organizing economic activities.

Ethnic specialization has historical roots in the ethnically diverse society, and some of the ancient ethnic specializations have carried in Dagestan into the present day, such as manufacturing certain arts and crafts (Musaev Reference Musaev2011). Moreover, ethnic division of labor in Dagestan is quite evident in its modern cities, where, for example, ethnic Laks are known for controlling the shadowy shoemaking industry in the republic (Musaev Reference Musaev2013). A subethnic group of Dargins, Kubachins are known for their artisan jewelry and embroidered weapon trades (Magomedov Reference Magomedov2014).

Even though land ownership is formally regulated by state laws, unofficial but powerful rules have governed ethnic land ownership in the North Caucasus (Lanzillotti Reference Lanzillotti2016). The land is one of the primary material resources in the area, and agricultural use of land is built on an ethnic basis. Therefore, ethnic groups have an important economic meaning across the region because one of the major income sources—agricultural land—is often worked by groups of ethnic kin (Starodubrovskaya et al. Reference Starodubrovskaya, Zubarevich, Sokolov, Intigrinova, Mironova and Magomedov2011). As a rule, redistribution of land in the North Caucasus is not based on religious identities of groups but on their ethnic affiliations (Meduza 2019). This implies the practicality of ethnic identities and a relative irrelevance of religion for the economic activities of groups.

Public visibility and political importance of ethnic solidarity movements in the North Caucasus appears to have receded with the strengthening of the central state in Russia. The Russian central state’s capacity increased dramatically in the 2000s (Allison Reference Allison2008). The demise of ethnic organizations in the North Caucasus could be explained by the strengthening of the central government in Moscow, which instilled law and order and thus removed the need for ethnic mobilization. However, if this explanation held, it would still not account for the rise of religion in the region.

The lifting of religious restrictions in Russia after the fall of the USSR in 1991 could be another alternative explanation for the advent of religion and a retreat of ethnic solidarity groups. The logic then would be that religion only claimed what belonged to it after the strict government constraints were removed or the government knowingly introduced religion to fill in the void after the fall of communism. Vastly greater freedom of conscience certainly had an impact on the ability of religious organizations to seek followers and spread their influence in the post-Soviet North Caucasus. However, this still does not explain why ethnic solidarity organizations lost their appeal to the public and shrank. Besides, some religious organizations violently opposed the government authorities, so they were far away from having amiable relations with the state. In fact, some researchers suggest that young people in the largest Muslim-majority republic of the North Caucasus, Dagestan, became less religious during the post-Soviet period for a time (Abdulagatov Reference Abdulagatov2012). A more plausible explanation is that ethnic solidarity groups transitioned into religious solidarity networks, as the material inequality in the society rose.

Data Description

The survey data for examining the conjectures advanced in this study come from the Russian North Caucasus, which is the most ethnically diverse part of the country. In 2008, a subsidiary of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Socio-Political Research, conducted a survey with over 1,700 respondents in seven republics of the North Caucasus using stratified probability sampling (Dzutsev Reference Dzutsev2012). The emphasis of the study was on the administrative units—republics rather than on ethnic groups—but the survey sample still included 56 ethnic groups.Footnote 11

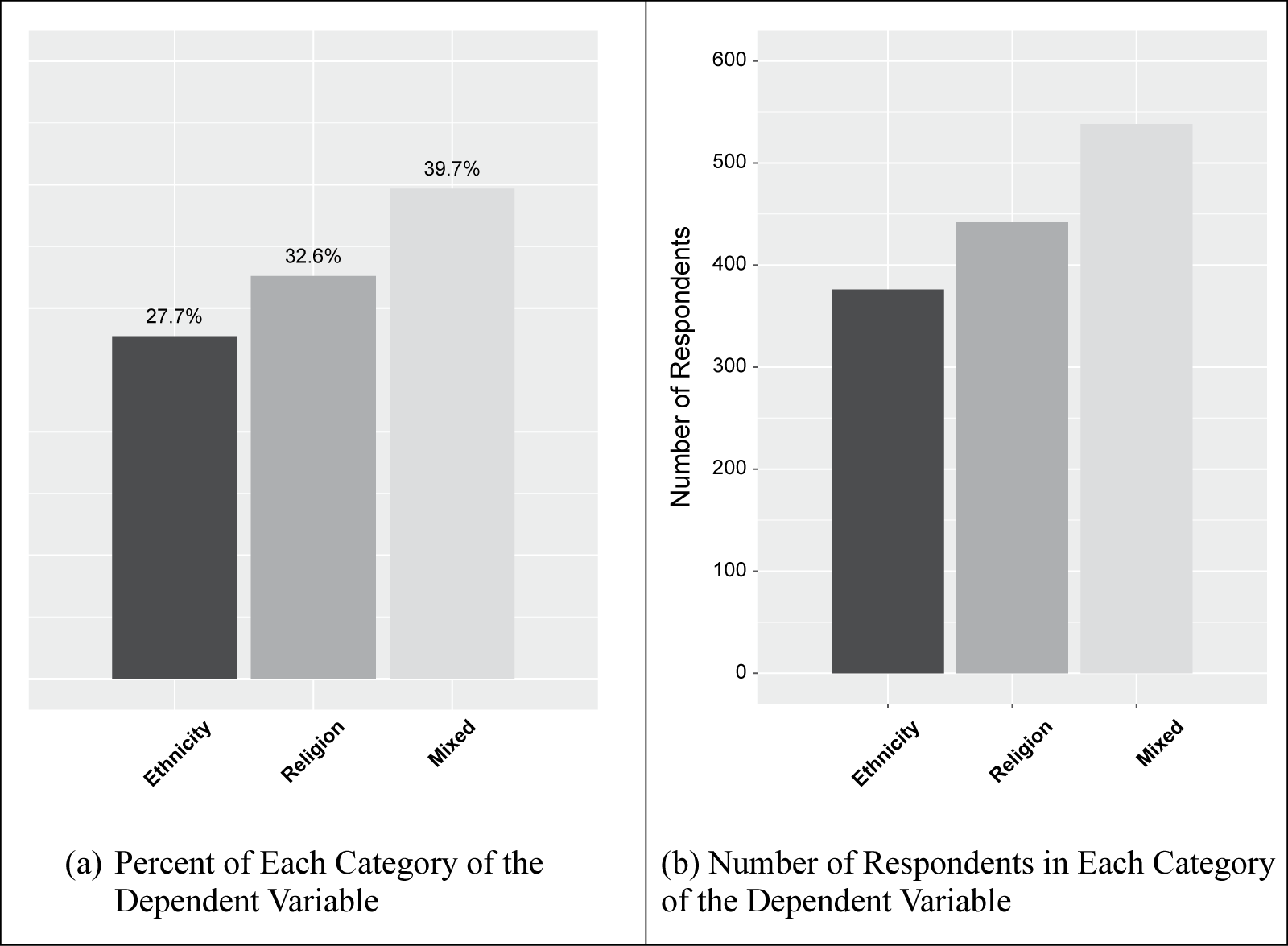

My dependent variable is a three-point nominal indicator that identifies an individual’s primary affiliation with ethnic, religious, and mixed (ethnic and religious) groups. Since there were no questions directly measuring respondents’ affiliation(s) with ethnic or religious groups, several closely related questions in the survey were used to construct the dependent variable—six questions for the ethnic identity and five questions for the religious identity. The choice of variables was informed by the attempt to account for a general positive attitude to one’s ethnic group and the manifestation of identities in the public sphere (Marsiglia et al. Reference Marsiglia, Kulis, Hecht and Sills2004; Upadhyayula et al. Reference Upadhyayula, Ramaswamy, Chalise, Daniels and Freudenberg2017). As the questions were measured on different scales, they were converted to dummy variables, which then were used to create ethnic and religious scores by taking the average for each respondent. Respondents who scored 0.5 or more on ethnic identity and less than 0.5 on religious identity were coded as an ethnic identity group. Respondents who scored 0.5 or more on religious identity and less than 0.5 on ethnic identity were coded as a religious identity group. Finally, respondents who scored 0.5 or more on both ethnic and religious identity affiliation were coded as a mixed group. Respondents whose score was low on both scales were excluded from the analysis (ca. 23% of the sample). The structure of the resulting variable is shown in figure 1.Footnote 12

Figure 1. The Structure of the Dependent Variable – Cultural Group Affiliation.

The first question gauged the ethnic identity of respondents and asked if they had friends among other ethnic groups. The second question measured the political component of the ethnic identity by asking if the respondent wished that each ethnic group receive government positions proportional to its percentage in the general population. The third question asked if newcomers in the respondent’s village or town should adopt local customs and traditions or keep their own. The fourth question evaluated respondent’s satisfaction with the state of affairs in the republic. Two other questions assessed attitudes of respondents to power relations between the republic and the federal authorities.

Respondents who had no friends outside their ethnic group, supported ethnic quotas in the government, and wanted the newcomers to adopt traditions and customs of their town or village were coded as “1.” In addition, respondents who simultaneously belonged to a dominant ethnic group and were in favor of increasing the powers of their republic were coded as “1” and so were those who had high esteem for the overall situation in their republic. Ethnic Russians received the code of “1” when they were in favor of increasing the powers of the federal authorities. Respondents with opposite attitudes were coded as “0.” In several questions, medium coding “0.5” was appropriate.Footnote 13 Distributions of ethnic groups in the survey are shown in figure 2. Overall, data for at least 54 ethnic groups were used in the analysis. Note that individuals whose ethnicity was not recorded still had a chance to be associated with ethnic groups rather than with religious groups.

Figure 2. Ethnic Composition of the Data.

Positive responses to these questions reflect a degree of importance of ethnic identity in the person’s worldview and life. I assume that if the person is not part of a group that emphasizes ethnic identity, it becomes less important to them. Therefore, they should not mention it in such questions. It is possible that the respondent may live in an area where there are no other ethnic groups around and be confined to interactions only with the members of their ethnic group. Questions on political attitudes are important and relevant to ethnic identities in the North Caucasus because dominant ethnic groups tend to regard republics as their ethnic homes. Hence, greater support for the republican autonomy reflects greater regard for one’s ethnic group. Coupled with the absence of religious affiliation (see below), this still means that ethnic identity plays a large role in the person’s worldview and life. It may not necessarily be the individual’s choice to be part of the ethnic group but their life situation.

Five other questions were used to construct the religious category. The first two questions measured the strength of the religious identity of respondents, asking how conscientiously they followed primary religious rituals and how often they read religious texts. The next two questions asked whether respondents supported religious organizations’ involvement in government affairs and school education. The fifth question asked if respondents wanted to live in a secular or sharia state. All answer choices were converted to dummy variables, and scores were calculated for individuals by taking the average of their responses.Footnote 14

Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 are tested using the nonmonetary indicator of respondent’s household income and its squared term, respectively called Income and Income Sq. Respondents are asked to put their families into one of the five categories: “Not enough money for food”(1); “Enough money for food, but not for clothing”(2); “Enough money for food and clothing” (3); “Sometimes we can buy expensive items” (4); or “We can afford everything” (5) (see fig. 3).

Figure 3. Distribution of Income Categories.

I also include several control variables. Age is an interval variable that ranges from 1 for the respondents aged 18–24 and up to 6 for the individuals aged 60 and above. The age of respondents is an important variable to control for because residents of the Russian North Caucasus have seen significant changes across a short period of time. Variable Male is a binary indicator of sex of the respondent, 0 for females and 1 for males. Gender of respondents has been found an important determinant of the social and political behavior of individuals in Muslim countries (Robinson Reference Robinson2008). Variable Urban is a binary indicator that takes the value of 0 when the respondent is from the rural area and 1 when the respondent is from the city. This is used to check for the confounding effect of more settled rural population versus more mobile city dwellers. Distrust strangers measures respondents’ trust toward strangers and is used to check for the effect of anomie, which is known to be widespread in societies that undergo rapid economic change (Zhao and Cao Reference Zhao and Cao2010).

To account for possible confounding effects of ethnic domination, I include two variables. Russian is a dummy indicator for ethnic Russians (1 for ethnic Russians and 0 for all others) as the country majority and dominant group at the national, but not necessarily at the regional, level. Dominant ethnicity is another dummy variable that accounts for the ethnic domination in each of the seven regions in the sample. This predictor takes the value of 1 when the ethnic self-identification of the respondent coincided with that of the governor’s of the region at the time of the survey in 2008 and 0 when it was different.Footnote 15

Two republic-level variables are included in the full models: average salary based on government statistics for 2008 and the number of killed individuals in the insurgency and counterinsurgency campaigns for the same year.

The Statistical Analysis

I estimate two pairs of multinomial regression logistic models on the response variable, comprised of ethnic, religious, and mixed affiliations.Footnote 16 Table 1 includes only the hypothesis variables, Income and Income sq. Table 2 adds all control variables.Footnote 17

Table 1. Ethnicity, Religion, and Economic Status. Hypothesis Multinomial Models.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Table 2. Ethnicity, Religion, and Economic Status. Full Multinomial Models.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Religion is the reference category in the first model, table 1a and table 2a, which means that the rest of the categories, Ethnicity and Mixed, are compared to the category Religion. Income and its squared terms for the Ethnicity category are statistically significant, showing that respondents’ personal income has a concave, inverted U-type relationship with the probability of associating with ethnic identity. As Hypothesis 1 expects, individuals in the middle-income category appear more likely to associate themselves with ethnic identity groups, as compared to individuals in the lowest and highest income strata.

Table 1b and table 2b show the results of the same regression, except the reference category is switched to Ethnicity. So, the remaining categories are compared to it. In accordance with the expectation in Hypothesis 2, individuals in the lowest and highest income strata appear to have a greater probability of maintaining membership in religious groups, as compared to the middle-income category.

The mixed category also indicates the same type of behavior as predicted in Hypothesis 3, but its statistical significance appears to be lower than that of the religious category. In other words, the Mixed category behaves similarly to the category Religion—the lowest and the highest income strata appear to have a greater probability to be in such a category, but it is more heterogenous than the religious category.

Older respondents tend to have a higher probability of choosing ethnic identification than younger respondents. The religious radicalization of the North Caucasian youth has been noted previously (Gerber and Mendelson Reference Gerber and Mendelson2009). Respondents who emphasize their religiosity rather than ethnic affiliation are not necessarily radicals, but they are certainly more likely to associate themselves with religious identities. Also, it appears that respondents who belong to dominant ethnicities are more likely to support an ethnic identification. This likely reflects the trend that members of dominant ethnic groups either materially benefit from belonging to such groups or expect to do so. The way the dependent variable was constructed also may have affected the relationship between the affiliation with ethnicity and belonging to the dominant ethnic group.

Marginal Effects

Predicted probabilities of belonging to one of the groups—ethnic, religious, or mixed—given low and high values of the variable of interest while holding all other variables constant at their means, help to visualize substantive relationships in the logistic statistical models. Figure 4a depicts the effect of income on the probability of an individual being a member of ethnic networks. Figure 4b shows the effect of income on the probability of an individual being a member of religious networks.

Figure 4. Marginal Effects Based on Multinomial Models. Gini Coefficients.

As the combination of income with its quadratic term indicates, there is a concave, inverted U-type, the relationship between the income of the individual and the probability of affiliation with an ethnic group. Respondents in the middle-income category are more likely to associate themselves with ethnic identity than the lowest and highest income category respondents. The relationship between the income of the individual and the probability of affiliation with a religious group is, on the contrary, convex, of U-type character. Respondents in the lowest and the highest income categories are more likely to associate themselves with religious identity than the middle-income category respondents.

The Gini coefficient of the groups analyzed here is also close to the expectations outlined earlier, although the substantive differences are relatively modest, given the sample size and the ordinal measurement of income. The Gini coefficient estimates inequality in a population. The higher its value, the greater the degree of inequality is in the population. Figure 4d shows that the Gini coefficient is at its lowest among the respondents who affiliate with ethnic groups.Footnote 18 The Gini coefficient rises in the group with religious identities and reaches its highest point in the mixed group. As a check on the primary Gini measurement, I also randomly select 50 individuals from each group—ethnic, religious, and mixed—to see if the inequality is driven by the number of individuals in each group. Figure 4e indicates that the relationships hold.

Bayesian Estimation of Multiethnic and Monoethnic Republics

The Russian North Caucasus is a complex region. Each of the seven republics that are present in the survey is unique. For example, Dagestan is known for its high ethnic diversity. Chechnya became known for two bloody wars that the Russian government waged against its self-determination movement. In Adygea, the dominant ethnic group are ethnic Adygeans (Circassians), even though ethnic Russians comprise the majority of the republican population.

Separate analysis of each republic would help to clarify the scope conditions of the proposed theory of identity choice. However, the sample size is quite small, especially as the primary explanatory variable is used via an interaction effect. The distribution of income in such a small sample indicates that percentages of individuals in low- and high-income categories are relatively small (see fig. 3). Nevertheless, one of the possible ways to explore the effect of different contexts on the validity of the theory is to subdivide the survey data into two subsets.

One subset is made up of the two most monoethnic republics in the North Caucasus—Chechnya and Ingushetia. The other subset is made up of the remaining five republics, Adygea, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, and North Ossetia.

According to the Russian census of 2010, ethnic Ingush comprised about 93.5% of the population of Ingushetia. Chechens, who are closely related to the Ingush people, made up another 4.5% of Ingushetia’s population. Ethnic Chechens comprised 95.1% of Chechnya proper during the same year. The second-largest group in the republic, ethnic Russians, amounted to 1.9%. The closest to Chechnya and Ingushetia in ethnic homogeneity among others came North Ossetia, where ethnic Ossetians comprised 64.5% of the republican population.

The theory predicts that individuals in the middle-income category will be more likely to have a strong ethnic identity while individuals in low-income and high-income rungs will be more likely to have a strong religious identity. One of the main explanations for this outcome is the structural argument. Cultural division of labor happens along ethnic lines, not religious lines, because, on average, there are more ethnic groups than religious groups. Hence, ethnicity turns out to be a more useful marker for the differentiation of in-group individuals from out-group individuals.

As Chechnya and Ingushetia are ethnically quite homogeneous, it is very likely that the cultural division of labor there will be different from more ethnically heterogeneous places.

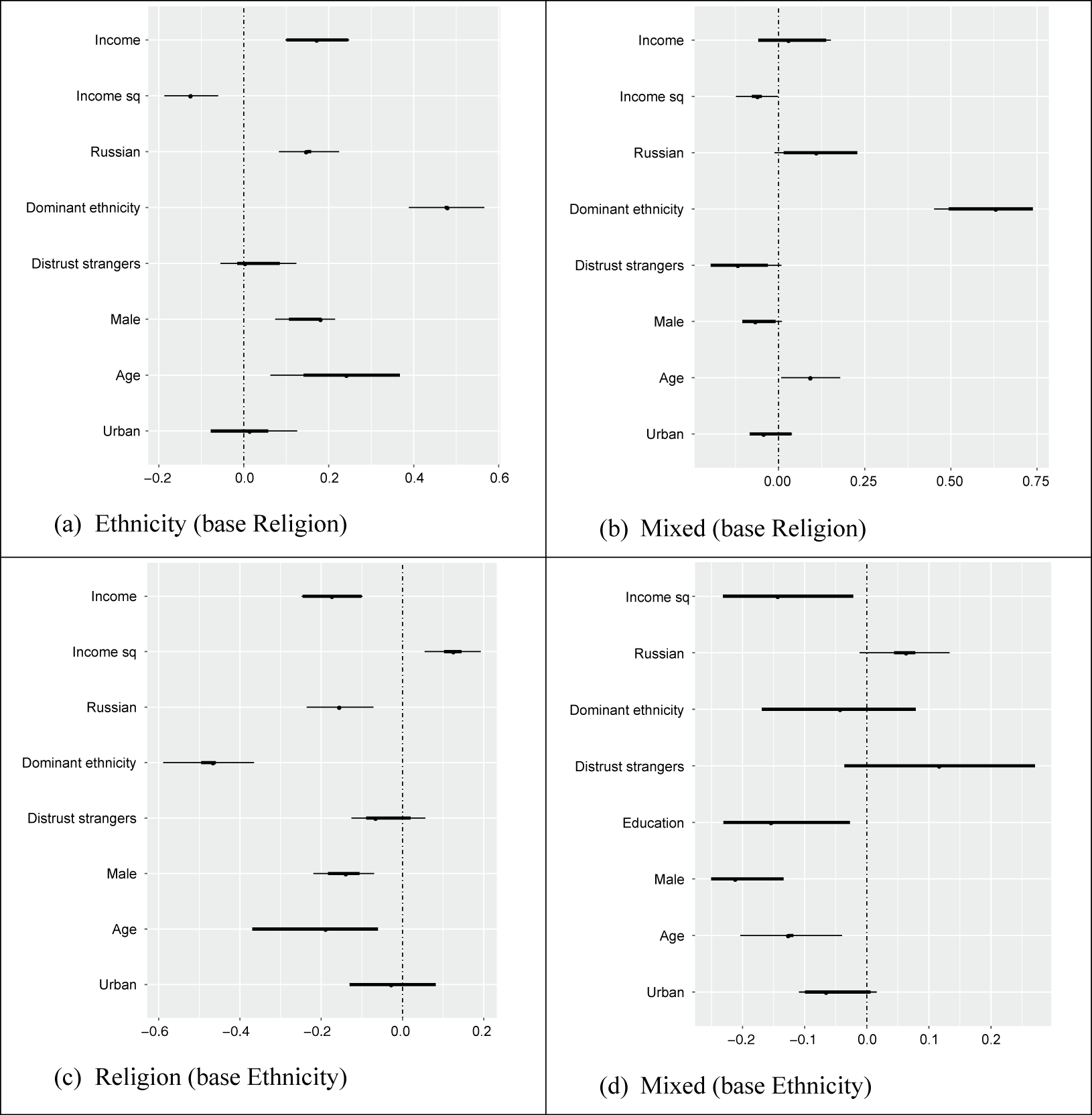

I apply Bayesian estimation to the two subsets of survey data—monoethnic and multiethnic republics. I also center and scale most independent variables by region to improve convergence and contextualize the data.Footnote 19 This process turns the independent variables into quasi-continuous predictors. Republic-level variables are removed from the analysis. The results of the analysis are shown in figures 3 and 4.Footnote 20 When thin whiskers do not cross the vertical dotted zero line, such indicators are significant at the equivalent of the 95% confidence interval (i.e., p < 0.05). Thick lines represent a 90% level of Bayesian credible intervals (i.e., p < 0.1).

The results of the analysis of the multiethnic subset are displayed in figure 5 (see the corresponding tables in the appendix). They broadly correspond to the results of the main analysis in table 2. Respondents from the middle-income category tend to affiliate with ethnic identities, while respondents from the low- and high-income categories affiliate with religious identities. However, the analysis of the monoethnic subset shown in figure 6 indicates a very different picture (see the corresponding tables in the appendix). The directions of relationships are consistent with the proposed hypothesis, but they fail on statistical significance in the monoethnic republics.

Figure 5. Bayes Estimation. Multinomial Model in Multiethnic Republics.

Figure 6. Bayes Estimation. Multinomial Model with Base Ethnicity in Monoethnic Republics.

Given the conditions of Chechnya and Ingushetia, the expectation would be that the middle-income category would be more likely to have religious affiliation. Low-income and high-income categories would be more likely to have ethnic affiliation. Both republics are highly monoethnic, which warrants the possibility of organizing a cultural division of labor along ethnic lines. Both republics are also known for internal religious rifts with the strong presence of Salafi and Sufi teachings, as well as some divisions within these groups (e.g., an influential group comprised by the followers of Sheikh Batal-haji Belkharoyev).

The survey data do not account for religious divisions in the North Caucasus, which does not allow for appropriate testing of the theory in monoethnic republics. For example, the category of dominant ethnicity that was used in constructing the dependent variable above should be replaced with the dominant religious teaching in Chechnya and Ingushetia. As a suppressed religious group in Chechnya, Salafis may not be in favor of greater involvement of religious groups in schools and government affairs because they will assume that the officially supported Sufism will dominate these processes.

Another possible reason for the divergent results is a general misrepresentation among Muslims in Chechnya and Ingushetia due to high security risks to respondents in 2008. Some respondents may not have reported their religious activities due to the fear that they might be targeted as radicals. Both Chechnya and Ingushetia were quite unsafe for civilians at the time of the survey implementation in 2008. Besides, due to the low numbers of lowest and highest income quantiles (see fig. 3), the results of the analysis in smaller subsets are fragile.

Discussion

Results of the analysis of the data from the North Caucasus provide support to the proposed theory of identity choice. Middle-income individuals appear to be more likely in the ethnic group category. The lowest and highest income individuals appear to be more likely in the religious group category. The mixed identity category indicates the same relationship with income as the religious group, but it is less robust.

The scope conditions for this relationship to hold include three primary provisions—two structural ones and one contextual. First, there must be a range of ethnic and religious groups so that they play a role in the cultural division of labor. Second, when the number of ethnic groups is significantly larger than the number of religious groups, the division of labor will be drawn along the ethnic lines. This will happen because it will be more practical to build such division lines using multiple ethnic rather than few religious categories.

The third provision is the state of society. When the society is transitioning from an egalitarian to an unequal condition, members of the mixed group category will be more likely to behave as members of the religious group category. This will happen because of the prevalent trend in the society in which ethnic solidarity groups will crumble and their members flock to religious groups.

As any model of society, this is a vastly simplified model of human behavior. Under different conditions, humans and their groups may behave differently. For example, the totalitarian government or other unusual labor market conditions might affect the labor matrix and actors’ payoffs. Severe and protracted civil conflicts might change the preferences of individuals.

If ethnic and religious preferences were measured in Chechnya prior to the First Russian-Chechen War in 1993, it is likely that they would have been different from the situation in 2000—at the height of the Second Russian-Chechen War. Even if other republics of the North Caucasus did not experience war-related hardship as Chechnya, preferences for group formations in them likely changed significantly from the Soviet era to the era of modern Russia. The rapid rise of income inequality should have had a particularly strong impact on the changes in group preferences.

Implications and Further Research

This study suggests that the variation in individual affiliation with ethnic (based on common language and a belief in common ancestry) and religious groups stems from material interests of their potential and existing members, as well as the ethnic-religious matrix of the society. In particular, the findings of the study indicate that the lowest and highest income categories are less likely to affiliate with ethnic identity groups. The relationship is reversed among religious groups, which tend to attract more people from the poorest and wealthiest strata of society.

The differential probability of individual adherence to ethnic and religious networks is explained by ideological differences between ethnicity and religion and by the divergent social roles of ethnic and religious groups. Ethnic solidarity groups are focused on economic activities. Religious identity groups specialize in ethical issues and broader social life.

Ethnicity-based organizations’ proclivity to economic homogeneity translates into the same attitudes among broader ethnic groups that are not necessarily based on joint economic activities but instead are large collectivities of ethnic organizations. This happens, for example, through the projection of the worldview of the individuals engaged in ethnicity-based organizations onto the larger society. It means that societies with a higher degree of ethnicity-based nationalism should display a greater degree of income redistribution and overall material equality. By the same token, a higher level of religiosity should be observed in societies with higher income inequality.

The less an individual is involved in ethnic group activities and networks, the less they can benefit from the group. Why would a rational individual not want to benefit from a package of benefits provided by the group?Footnote 21 There may be several reasons, perhaps a principal one being that there is a cost associated with receiving group benefits. Some individuals may not be willing to pay that price and prefer to opt out (Olson Reference Olson1965). Opting out of individuals should be most widespread among the highest income stratum of the group. On average, the individuals with higher income should not want to contribute to the group’s activities because their cost-benefit calculations should indicate that they are losing out in such a group. High-income individuals should prefer to join another type of group, or affiliate with the state, which provides the same group benefits at a lower cost to the high-income individual.

Individuals from the lowest income strata should be affected in the opposite way. They want to receive benefits from the group. Yet, since they require more favors from the group than they can return, they tend to be excluded from the group. The poor do not stop belonging to a certain ethnic group. Rather, they stop their participation in the cultural (based on ethnicity) division of labor in the society and have to seek benefits from religion-based organizations, rely only on the state, or seek other opportunities.

So, wealthy individuals opt out from the ethnic identity groups because of the high costs relative to the expected benefits, while the poorest individuals are forced out of the ethnic occupational groups because of the burden they put on them by demanding much and contributing little.Footnote 22 Therefore, ethnic solidarity groups should, on average, be groups of equals, nurtured and sustained primarily by the middle class.

Relative to ethnicity, religion is able to accommodate a greater variation of differences among its constituents (Botero et al. Reference Botero, Gardner, Kirby, Bulbulia, Gavin and Gray2014; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2013). Religious group affiliation is likely to have the opposite relationship with personal income when compared to ethnic group affiliation. The least affluent and the most affluent individuals should be more likely to affiliate with a religious group than the individuals in the middle-income category. Religious groups are likely to be more accommodating toward both the poor and the rich than ethnic groups. Religion shows greater tolerance toward the poor and, at the same time, toward income inequality, which attracts the rich. Religious rich and religious poor are likely to form political coalitions in electoral democracies (Huber and Stanig Reference Huber and Stanig2011).

The theory in this study points to possible applications in research on conflict processes. For example, regarding violent conflict, ethnicity-based conflicts should have a greater emphasis on the scramble for material resources, while religion-based conflicts should emphasize existential values. This will likely increase the incidence of ethnicity-based conflicts but make them shorter. Religion-based conflicts will be less likely to happen, but once they start, they will be harder to stop.

The statistical analysis of the survey data presented here supports the relationship between personal income and the probability of adhering to an ethnic or religious principle of group formation. However, some limitations are worth noting. Strength of each identity is measured as a self-declared personal attitude rather than actual mobilization of individuals based on such identities. The statistical analysis section does not provide the test of changes over time, although the qualitative case study of the Russian North Caucasus points to the transition of people from ethnic identities to religious ones while material inequality in the society also increased. The research is also limited to one particular region of a country and a limited set of religious and ethnic identities. These findings should be tested in other countries, with other ethnic and religious groups and using longitudinal data.

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments on the article, I thank Mikhail Alexeev, Michael Hechter, Kyle Marquardt, David Siroky, and the anonymous reviewers of Nationalities Papers. I am also thankful for the survey data used in the study to Khasan Dzutsev. The article greatly benefited from feedback at ASEEES 2014, ASN 2016, and ASREC 2016 panels.

Financial Support

This research was supported by Arizona State University’s Center for the Study of Economic Liberty (CSEL). Research supported by CSEL reflect the views of the authors and not necessarily CSEL.

Disclosure

The author has nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.26.