Introduction

Over the past decade, the literature about national-cultural or nonterritorial autonomy (NTA) regimes has grown, involving analysis from comparative-historical, normative-theoretical, and practical perspectives (Coakley Reference Coakley2017; Cordell and Smith Reference Smith and Cordell2008; Malloy, Osipov, and Vizi Reference Malloy, Osipov and Vizi2015; Malloy and Palermo Reference Malloy and Palermo2015; Nimni Reference Nimni2005; Nimni, Osipov, and Smith Reference Smith2013; Salat, Constantin, Osipov, and Székely Reference Beretka, Levente, Sergiu, Alexander and István Gergő2014; Smith and Hiden Reference Smith and Hiden2012), and including regimes of this kind established in various Central and Eastern European countries after the fall of Communism. In contrast to territorial forms of minority self-governance, this kind of autonomy has a strong focus on individual participation and may be particularly suitable for territorially dispersed and relatively small minorities. Since the model is designed to include those who belong to certain groups irrespective of their place of residence and population size, it requires at least one institution at a national or lower level that seeks to unite, organize, and represent potential group members, established either under public or private law. In Central and Eastern Europe, despite the existing dominance of the nation-state model (as well as the Communist legacy) whereby public institutions have been widely viewed and often still function as the almost exclusive property of the titular nations (Agarin and Cordell Reference Agarin and Cordell2016; Cordell, Agarin, and Osipov Reference Cordell, Agarin and Osipov2015), several countries (primarily Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Kosovo, Latvia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, Russia, and Ukraine) started to create autonomy frameworks for their domestic minorities from the early 1990s onward.Footnote 1 About half of these countries—namely Estonia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia—opted for elected forms of NTA, which grant voluntarily registered minority voters the right to establish minority councils or self-governments by direct or indirect elections at various levels.

In the course of the 20th century a basic consensus emerged regarding the minimal conditions under which general elections should take place in democracies. The institutional design of electoral systems and their effects on voters and party systems in both established democracies and democratizing states have also been extensively covered in comparative research. Very little, however, is known about the role of NTA elections in shaping the intra-community relations of minorities in the aforementioned countries of Central and Eastern Europe.Footnote 2 The key guiding questions that arise are whether and, if so, how the functions and policy consequences of regular parliamentary and municipal elections can be conceptualized in these special minority contexts: which of the possible functions and effects of elections make sense and are of particular relevance at this level, and how can the major findings of the electoral literature be applied to these special configurations?

Elections certainly raise a number of issues central to understanding how minorities become engaged in processes of representation and, conversely, how the institutional arrangements in question affect the respective minority groups. This article, however, adopts a narrower focus by exploring, in a comparative manner, the general patterns of NTA elections in the five countries concerned. After giving a brief theoretical and historical overview of the main features of post-communist NTA regimes, it primarily concentrates on the major goals and functions of elections identified in the relevant literature, using these as analytical tools for assessing whether and how minority elections perform the most prevalent functions and meet the requirements of democratic elections. Taking the types and different levels of elections into account, the crucial questions are: how eligible voters and organizations are defined and registered in the electoral process; and consequently, how and to what extent the minority elections increase legitimacy and accountability, contribute to the channeling of debates, the creation of effective representative structures and the selection of representatives; and whether they encourage voter participation. The article also considers how these aspects can be conceptualized and understood in these special minority contexts. Accordingly, the article, from a theoretical perspective, but supported with electoral statistics and country experiences, aims to contribute to an enhanced understanding of the role of elections in minority contexts and whether such elections can be considered successful forms of diversity management and minority integration.

The Theoretical Challenges and Historical Background of Minority Elections

Almost three decades after the fall of Communism, a considerable number of Central and Eastern European countries give prominence to NTA in their legislation and policies. Where this commitment has resulted in new institutional arrangements, in one group of countries and most prominently in Russia, it implies that special associations are endowed with public functions such as maintaining educational and cultural institutions. In practice, this idea has barely been implemented in the Russian case (Osipov Reference Osipov2010). Similarly, in Latvia, pursuant to the 1991 law on cultural autonomy, so-called national societies have the right to develop their own educational institutions.Footnote 3 Since membership in such associations is voluntary, this approach immediately raises at least two issues related to legitimacy: for a voluntary organization it is more difficult to reach less active and committed members of the ethnic group; furthermore, the potentially large number of associations might easily undermine the possibility for the autonomous organizations to represent the minority in interactions with state authorities (Brunner and Küpper Reference Brunner, Küpper and Kinga2002, 27).

By creating specific and elected institutions, the other group, consisting of the above-mentioned five countries, follows a different model, while there are also other intermediate cases that cannot be grouped together with these two main types of associational and elected systems. In Montenegro, as a result of the 2007 amendment to the country’s 2006 minority law, minority councils are partly elected through electoral assemblies, in which citizens can participate who have previously declared their affiliation, although they are not registered.Footnote 4 In addition, some key representatives of the communities, such as minority members of parliament (MPs), ethnic party leaders, or local mayors of municipalities in which the minority population constitutes a local majority, can be ex officio members, too, and in certain cases their number is greater than that of the elected members.Footnote 5 The mostly elected “peoples’ congresses” in Russia also lack a mechanism for voter registration (Osipov Reference Osipov2011). The Mejlis, the elected, representative-executive body of the Crimean Tatars was outlawed by the Russian authorities in 2016. Since these cases only partly fit the latter category, they are excluded from the present analysis.

From a historical perspective, the idea of attaching voting rights separately to different ethnic communities can be traced back to the late period of the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy: the Moravian Compromise of 1905 divided the electorate into two parts (Czech and German) in the province, while four years later a similar arrangement in Bukovina established separate polling lists for the local Romanian, Ruthenian, Polish, German, and Jewish populations. Finally, the 1914 compromise between the Polish and Ruthenian population of Galicia could not be realized at all due to the outbreak of World War I (Kuzmany Reference Kuzmany2016; Stourzh Reference Stourzh and Gerard2007). Nevertheless, these arrangements at the beginning of the 20th century had a crucial theoretical impact. The Austro-Marxist theorists of NTA, most notably Karl Renner (Reference Renner and Ephraim2005, 26), regarded elections as central components in the process of establishing nonterritorial cultural autonomy. The idea of NTA emerged as a demand among several Jewish political forces already in tsarist Russia (Pinkus Reference Pinkus1988, 43–44), later extending to other minorities at the time of the revolutions and civil war (Bowring Reference Bowring and Nimni2005, 166–168). This demand also affected the decisions of the Ukrainian Central Rada, which adopted a law on non-territorial autonomy in January 1918—the earliest known legal example. However, the law was not implemented and was soon superseded (Liber Reference Liber1987).

The model also continued to be quite influential in the interwar Baltic States, where Lithuania’s 1920 law on Jewish cultural autonomy created elected councils at a local level. More often cited is the 1925 minority law in Estonia, which enabled the German and Jewish communities to establish functioning cultural councils on the basis of elections (Smith and Hiden Reference Smith and Hiden2012, 26–61). NTA, however, later became easy prey for Communism in the region, while only in the Slovenian republic did the two small and non-Slavic communities, the Hungarians and Italians, create state-controlled, elected organs in the middle of the 1970s (loosely related to the all-embracing idea of Yugoslav self-management). Meanwhile, similar solutions were not introduced to other parts of Yugoslavia.

The findings that have been published regarding the aforementioned extensive array of post-communist, nonterritorial models underscore the tension between, on the one hand, the continued dominance of the nation-state model and expansion of state control of minority issues and, on the other, the positive expectations that led to the spread of various NTA regimes in the region. Focusing on a continuum of the degree of power-sharing, Malloy (Reference Malloy, Osipov and Vizi2015, 3–4) finds that four out of the five cases (Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, and Slovenia) give minorities a voice by allowing them to make decisions or participate in relevant decision-making processes; the exception here is Estonia, where the role of minority councils is rather symbolic. In examining the competences of these bodies, however, Salat (Reference Salat, Tove, Osipov and Vizi2015, 260–261) concludes that all of the cases in question involve only symbolic power, despite their strong legal background. It can indeed be suggested that these institutional examples were more likely created in a top-down way so as to offer minority groups only symbolic and apolitical (educational and cultural) power, thereby preventing and neutralizing any potential territorial claims. The emphasis on cultural issues and weakening of the competences of the minority institutions is especially notable in the case of the Roma, given the minimal effort that states have invested in improving the socio-economic inclusion of one of the region’s largest ethnic groups (for Hungary, see e.g. Vizi Reference Vizi and Rechel2009, 128–131).

Yet surprisingly little research has been conducted to assess the extent to which these regimes meet minority demands, effectively empower and strengthen capacities for public participation and promote integration while reflecting intra-group pluralism. In highlighting how the implementation and practice of NTA and competences of the relevant organizations vary across states, some research has emphasized the need to support bottom-up activities and strengthen democratic accountability and effective representation (Osipov Reference Osipov2010, Reference Osipov2013; Smith Reference Smith, Keith and O’Neill2010, Reference Smith2013a). On this basis, the authors in question call for further research on how minority members and minority representatives perceive and use their own autonomy-promoting organizations in reality, as well as how they view themselves, their identities and their role within the organizations, particularly in the context of the nation- and state-building processes of the region.

The aforementioned analyses all suggest that normative assumptions about social justice and tackling diversity were not the main considerations when it came to establishing NTA regimes in the countries concerned. Instead, it is argued, their creation was more motivated by other, instrumentalist considerations, such as international pressure, compliance with external standards, or internally driven expectations of reciprocity. With regard to the latter, it is widely accepted that Hungary’s 1993 minority law was adopted with an eye to the Hungarian minorities who live in neighboring countries and similarly, that Slovenian legislation was created with attention to the situation of co-ethnics in Austria and Italy (Komac and Roter Reference Komac, Roter, Tove, Osipov and Vizi2015, 96). The Estonian act (also adopted in the early 1990s) served to bolster the country’s unfavorable external image in relation to its citizenship policies toward Soviet-era migrants (Smith Reference Smith2013b, 125). Lastly, facing pressure from the Council of Europe and the European Union (EU), both Croatia and Serbia had to develop systems of minority protection after the death of Franjo Tudjman in 1999 (Dicosola Reference Dicosola, Balázs, Tóth and Dobos2017, 86–87), and the fall of the Slobodan Milošević regime in 2000 (Korhecz Reference Korhecz, Tove, Osipov and Vizi2015, 74–75).

The above factors support the idea that minority elections are a potential tool for identifying and critically assessing intra-group dynamics. In this respect, electoral systems, including those of the present NTA cases, may be understood as political institutions and products of the political process: both causes and effects of political outcomes that in many cases can hardly be isolated (Birch Reference Birch2003, 17). They involve a complex set of structuring factors that provide opportunities and create institutional barriers to alternatives (Herron Reference Herron2009, 30–31). As a result, the electoral system has long been considered – to quote Sartori – “the most manipulative instrument of politics” (Grofman and Lijphart Reference Grofman, Lijphart, Bernard and Lijphart2003, 2). Various actors, including voters, candidates, and nominating parties, may use elections strategically to accomplish their specific goals, to influence and even to manipulate electoral rules and institutions; yet, at the same time, these rules and institutions have crucial effects. Electoral systems and rules are not democratic per se, and are in fact far from neutral; all of them have a political or social bias, favoring certain groups over others. The issue is particularly important, since many scholars have pointed out that choosing or reforming an electoral system not only involves the electoral process, but is also about competing normative values and preferences (Benoit Reference Benoit2007). As such, the related decisions are among the most important in the democratic process.

These decisions do not only involve adopting or combining majoritarian and proportional electoral formulas, for it is generally agreed that in every democratic political setting the function of elections goes beyond simply filling posts with candidates. In this regard, the relevant literature usually emphasizes goals such as legitimization, elite recruitment, the possibility of controlling leaders, aggregating voter preferences, and exercising political accountability.Footnote 6 Accordingly, elections, both in theory and practice, may fulfill a variety of functions that are highly context-specific, depending first and foremost on the type of regime,Footnote 7 the nature of the elected body (collegial or singular character, level of elections, competences, resources) and the electoral formulae that are adopted (majoritarian, proportional, or mixed). The relative importance and impact of their potential functions may also change over time and vary from one political setting to another (Wojtasik Reference Wojtasik2013, 26). In addition, some functions are hardly consistent with each other, especially if elections are viewed as a mechanism of accountability and voting is based on past performance, or if the aim is that the representative body should represent the diverse interests of the electorate (Herron Reference Herron2009, 3; Thomassen Reference Thomassen and Thomassen2014).

Furthermore, and as noted above, electoral systems not only fulfill various functions, but may also have numerous effects on electoral participation, nomination, and party competition, among which Duverger (Reference Duverger1951) has distinguished mechanical and psychological effects. The former concerns impacts on the party system in particular, since they involve how electoral rules translate votes into seats. Duverger argues that in plurality systems these effects reduce the number and types of viable parties, while list-proportional systems provide greater access to legislatures, even for smaller parties. The psychological effect refers to how electoral systems incentivize voters to engage in strategic voting over time. In addition to Duverger’s classic and much-discussed findings and study of the impact of the most significant components of electoral systems (electoral formula, ballot structure, district magnitude), in the present cases of NTA elections other institutional factors seem to be equally decisive in explaining effects. These include voter registration, how voters and organizations access the electoral process, perceived legitimacy, and even the date of elections (Grofman and Lijphart Reference Grofman, Lijphart, Bernard and Lijphart2003, 2–3).

NTA Elections: Defining Legal Entities

Each of the analyzed NTA systems has a somewhat different function and faces different challenges depending primarily on the domestic institutional context and the circumstances of the minorities concerned. In all five countries, minority bodies are typically elected directly by the registered voters, even in Serbia where the national minority councils were elected indirectly until 2010.Footnote 8 Organs of representation are also created indirectly at various levels in other countries, such as the national and regional minority self-governments (MSGs) in Hungary until 2014, the (national) coordination of MSGs in Croatia, and the highest body of self-governing ethnic communities in Slovenia. In Estonia and Serbia, autonomous bodies are elected only at the national level by proportional electoral systems, while Croatia and Slovenia have adopted majoritarian systems even at the local level. In three cases NTA bodies are elected for four years, in Estonia their mandate is only for three, and in Hungary it has been five years since 2014. In all the countries concerned, it was not the minorities that determined the rules of minority elections, but the government (Estonia) or parliament, in such a manner that either the relevant provisions of the law on local elections now have to be applied to NTA elections (Croatia, Slovenia), or a separate law determines their conditions (Hungary, Serbia, see Table 1).

Table 1. The main institutional features of NTA elections in the five countries.

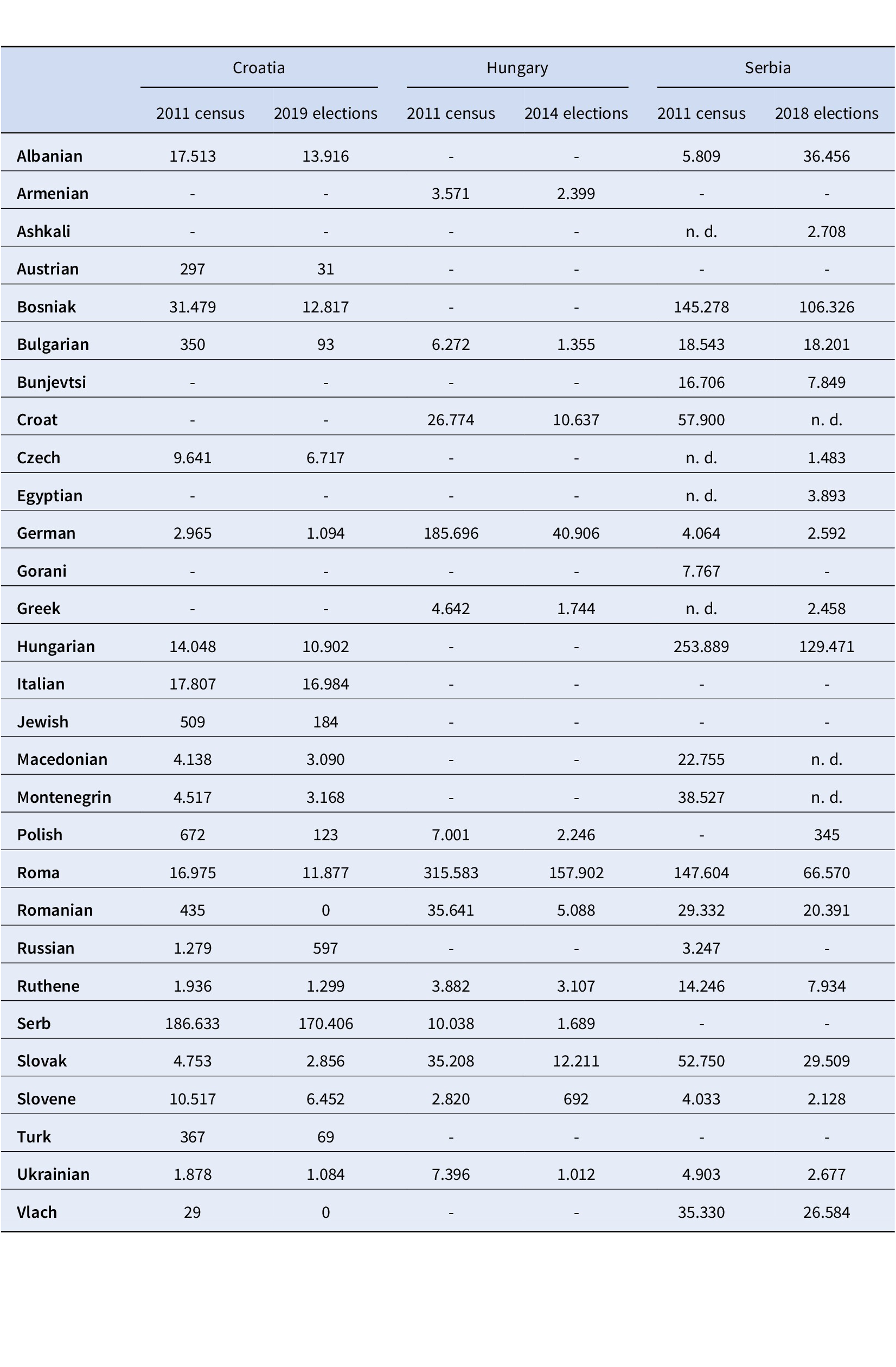

There is a crucial difference between two groups of countries: it is only in Estonia and Slovenia where minorities themselves have the right to compile and administer electoral registers of their own voters and establish their own election management bodies to supervise the electoral process, while in the other three cases state and municipal electoral commissions are in charge of monitoring, and registers are administered by state authorities (Croatia, Hungary, and Serbia). The list of recognized minorities which are entitled to create autonomous bodies can usually be found in the relevant legal acts: in the country’s constitution or minority law. In Estonia and Croatia, NTA has in practice been applied only to two small communities in each case, namely to Ingrian Finns and Swedes in the former, and Hungarians and Italians in the latter. In Hungary, meanwhile, the law covers 13 officially recognized communities, while in both Croatia and Serbia elections are typically held for almost 20 national and ethnic groups. However, the overwhelming majority of groups concerned are relatively small and scattered throughout the countries in question, and are at an advanced stage of cultural-linguistic assimilation. Only a few of them have become politically mobilized along ethnic lines and managed to create their own ethnic parties, mostly in Croatia and Serbia where the political mobilization of specific, usually larger and territorially more concentrated communities can be traced back to the time of the violent breakup of Yugoslavia, thus preceding the creation of later arrangements for autonomy. Among them, only the number of Serbs in Croatia, Bosniaks, Hungarians, and Roma in Serbia, and Germans and Roma in Hungary exceeds 100,000 according to the official census (Table 2).

Table 2. Minorities that had at least one election between 1994 and 2019 in the five NTA systems.

i Since the 2010 introduction of direct elections of national councils.

As to the right to vote, the analytical point of departure is the well-known and complex condition of “free and fair elections” in democratic political settings, referring basically to the fact that every eligible adult citizen shall have the right to vote and be elected on a nondiscriminatory basis (freedom of voters), and on the other hand to the possibility of choice in the form of competition between parties and candidates (Hermet Reference Hermet, Guy, Rose and Rouquie1978). However, this kind of institutional setting almost inevitably raises questions and dilemmas, both in theory and in practice. These revolve around the process of establishing community boundaries (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2001)—who belongs to the given minority and who does not—and how this belonging should be appraised (i.e. whether and how group members should be defined and registered). Inherent to this process are the “politicization” of ethnicity and the framing of identity as a compulsory, dividing, and prescribing category. In practice, however, the groups concerned are often at an advanced stage of assimilation, and possess multiple, blurred or even contested identities, where clear-cut boundaries can be hardly drawn. Consequently, it can be argued that the need both to register themselves and to go and cast their votes usually on different days to general elections and in separate polling stations could mean higher costs for group members (Birnir Reference Birnir2007, 223).

In addition, members of some minorities are still coming to terms with historical traumas resulting from earlier incidences of ethnic discrimination, or continue to face negative attitudes and prejudices, as is the case with the Roma. Under such circumstances, the need to declare their identities and register themselves may even have a demobilizing effect. As a result, significant parts of these communities may abstain from minority elections. To illustrate this fact, the data presented in Table 3 show that in the overwhelming majority of cases in the three more heterogeneous countries, the number of registered minority voters during the most recent elections was consistently lower than the number of those who had declared themselves as belonging to the officially recognized minority communities during the latest censuses – the cases of Albanians in Serbia (most of them boycotted the 2011 census) and Serbs in Croatia were rather exceptional. The former number was even less than the estimated number of the ethnic group within the population (taking note of the fact that census results included those such as minors who did not have the right to participate in minority elections).

Table 3. Number of individuals belonging to national and ethnic minorities in Croatia, Hungary and Serbia according to the censuses of 2011, and the number of registered minority voters at the latest NTA elections.ii

ii Sources: Croatian Bureau of Statistics: Population by ethnicity, by towns/municipalities (Census 2011). www.dzs.hr/Eng/censuses/census2011/results/xls/Grad_02_EN.xls Electoral statistics: www.izbori.hr Hungarian Central Statistical Office: 2.1.6.1 Population by nationality, age group, highest education completed and sex, 2011 www.ksh.hu/nepszamlalas/docs/tables/regional/00/00_2_1_6_1_en.xls Electoral statistics: www.valasztas.hu Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Population by etnicity and sex, by municipalities and cities (2011): media.popis2011.stat.rs/2014/eksel/Opstine/1_Stanovnistvo%20prema%20nacionalnoj%20pripadnosti%20i%20polu,%20po%20opstinama&gradovima.xls Electoral statistics: http://www.rik.parlament.gov.rs/latinica/izbori-za-nsnm-neposredni-2018-ukupni-rezultati.php (accessed November 20, 2018).

In most cases, the right to vote is granted to adult, resident voters belonging to the officially recognized national and ethnic minorities who have previously declared their affiliation to the relevant minority group and registered themselves on special electoral lists. With the exception of Slovenia and Hungary,Footnote 9 access to minority rights and institutions, and consequently to minority elections, has been traditionally reserved only for citizens of the countries concerned. The requirement of permanent residence poses a serious challenge especially to the majority of Estonian Swedes who moved to Sweden at the end of World War II but for whom it was possible to vote abroad as Estonian citizens.Footnote 10 In addition to the subjective declaration of ethnic affiliation, it is rather rare to find either more or less detailed objective criteria for appraising whether applicants belong to the given community: in Slovenia, for instance, according to the 2013 law on voter registration, an individual may only be included on the list if they have been on any of the previous lists, maintain long-lasting ties with the minority, aim to preserve minority characteristics, or have family connections with someone belonging to the group (Komac and Roter Reference Komac, Roter, Tove, Osipov and Vizi2015, 107). The preconditions for minority elections are in most cases dependent on official census results: for example, in Croatia elections of local minority-self-governments in towns and municipalities can be held if the local share of the minority population is at least 1.5% or there is a minimum of 200 group members. In Serbia, the direct elections of national councils are permitted if at least 40% of the group members are registered on the electoral lists. Interestingly, although the main objectives of the autonomy arrangements are basically the same in all cases (to preserve and develop minority identities), defining the membership of the community seems to have adverse effects: in Estonia and Slovenia, minorities seek to attract and mobilize the more assimilated and less committed members, while on the other hand, the lack of objective criteria and group control has led to electoral abuses in the three other countries, most notably in Hungary, where the vague nature and different forms of identities often give rise to debates about group boundaries. In addition, by further modifying and constantly restricting electoral rules especially on the basis of the struggle against electoral abuse commonly known as ‘ethnobusiness,’ recent Hungarian legislation may have had a demobilizing effect in certain cases, discouraging voters from participating in minority elections.

The Elements and Functions of Elections in NTA regimes

Nomination

It is not only voters but also organizations that are faced with institutional barriers to entry at NTA elections. The right to be elected is open to anyone who possesses voting rights. However, the right to nominate candidates is reserved for minority organizations (in Serbia also political parties) and – with the exception of Hungary – groups of voters of a specified size/a specified number of voters who can also field independent candidates on the basis of collecting the required number of signatures. In Hungary, as part of attempts to address electoral abuses, candidates were required not only to declare their identity but from the latest 2014 elections also affirm that they had not stood as candidates for any other minority communities in the previous two minority elections.

Number of Contenders, Electoral Competition

Closely related to the issue of nomination, a further crucial question on the supply side of NTA elections involves whether voters, in delegating political representation or awarding representatives power through votes for the purpose of making more efficient decisions, should have the option not only to support those who have been pre-selected by nominating organizations (by electing them), but to select representatives with appropriate skills and with whom they share some views and values. In other words, the question is whether voters should be given the possibility to choose from alternatives and actually select among different objectives and various rival candidates and parties (Rahat Reference Rahat, Cross and Katz2013, 143). In the absence of such representation, the process refers more to representatives mirroring a sample of the electorate. In this regard, the crucial question is whether real competition can be expected at all in terms of the main subjects of the NTA regimes, given that the relatively small and dispersed minority groups are often at an advanced stage of assimilation. This consideration, furthermore, is closely related to another issue: that of elite selection and recruitment.

Overall, by the 2010s, the number of candidates standing for elections had attained a stable level under both plurality and proportional regimes in successive elections, although it has obviously varied over time and across the various minority contexts. Regarding the relation between the number of candidates and the electoral formula adopted, one can hardly claim that there is a strong correlation between them. NTA elections are on the whole highly noncompetitive with the degree of electoral competition more likely to be determined by factors such as group size, intra-group rivalry, degree of territorial concentration, perceived efficacy (competences and resources of NTA bodies) and individuals’ rational cost-benefit calculation as to whether to stand as a candidate. In majoritarian systems (Croatia, Hungary at the local level, and Slovenia), voters are often required to choose from the same number of – or one or two more – candidates than the number of available seats. In Hungary where the number of representatives for election in a local MSG was four in 2010 and candidates needed to obtain a relative majority of votes to win seats (bloc vote), real choice among different, contending organizations and candidates only occurred in communities divided along various political-ideological as well as cultural-linguistic lines (such as the Roma) or between longer-established autochthonous minority grouping and more recent arrivals (such as the Romanians) (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average number of candidates for local MSG elections in Hungary, 2010.

The Slovenian case, however, shows that territorial concentration and local size seem to matter: the smaller and less organized Italian community concentrated in the urban centers along the Adriatic Sea was able to field more candidates than the numerically larger, more organized Hungarian community who live in rural areas alongside the Hungarian border (Table 4).

Table 4. Number of candidates and mandates at the 2014 elections of councils of self-governing ethnic communities in Slovenia.

In another group of cases in which the list-proportional formula was adopted, minority voters could often vote for only one list of candidates: for instance, at the latest elections of the Swedish Cultural Council in Estonia (in 2016) there were 22 candidates for 21 seats,Footnote 11 although earlier, in 2007, Swedish autonomy was created by more than 10 minority organizations (Smith Reference Smith, Levente, Constantin, Osipov and Székely2014, 313). But, if one takes the example of more numerous minorities, such as those participating in earlier elections to national MSGs in Hungary, electors could vote for one or two lists; interestingly, as the system switched to direct elections in 2014, this altered the balance of organizations only in a smaller number of groups, so a greater number of contenders did not necessarily lead to a higher level of competitiveness, and vice-versa. As a result, national MSGs in Hungary (with a 5% electoral threshold) are either dominated by the most influential organizations, or larger and smaller organizations are almost equally represented. In Serbia, by contrast, greater competition (and the lack of an electoral threshold) resulted in more balanced representation among minority organizations.

Ballot Structure

There is a growing body of literature on the impact of ballot structure, especially on the psychological effects of choice on voters’ behavior. A number of studies have demonstrated in various electoral contexts that being listed first has had a significant effect on the vote shares of candidates (Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick1998). In all of the cases analyzed here and at each level, categorical ballots are used whereby voters are expected to opt either for an individual candidate or for a party list. In proportional systems (Estonia and Serbia), the list of candidates and parties is sorted according to the date of their nomination. In majoritarian systems, the order of candidates is either decided by lot (Slovenia, Hungary local level since 2006) or based on their position in the alphabet (Croatia, Hungary until 2006). Some local case studies from Hungary suggest that alphabetical ordering has had a serious distorting effect, since in the analyzed municipalities, the overwhelming majority of those whose surname started with the first letters of the alphabet received a larger number of votes than others (Rátkai Reference Rátkai2000). In 2002, for instance, name-order effect or ‘alphabet-preference’ advantaged those listed first by an average of 18% when compared with the average total of valid votes cast per candidate. When special minority electoral lists were introduced four years later and the order of candidates became decided by lot, this effect seemed to weaken or even disappear in certain cases.

Legitimization and Accountability

It is widely assumed that elected forms of representation increase and provide democratic legitimacy to those elected to power, in great part due to the belief in the fairness of their procedural mechanisms responsible for selecting leaders (Beetham Reference Beetham1991). Thus, in several cases, the need for legitimate authority to act on behalf of group members was an important consideration when opting for NTAs based on competitive elections. Although it is evident that the formal electoral procedure itself lends some legitimacy to the elected bodies by ensuring a peaceful transition of power, the term “legitimacy” gains additional meaning when applied to community legitimacy in minority contexts. Here, it also relates to how and whether minority constituents perceive their representatives as legitimate – taking into account the fact that group identities and boundaries can often become contested, and that even small and scattered groups may have a high level of internal diversity, especially in the broader context of the nation- and state-building projects of nationalizing states in the region. The issue of group legitimacy has become especially striking and significant in the Hungarian case, where, since minorities originally rejected any kind of registration, until 2006 every Hungarian voter had the right to vote and be elected to MSGs. As a result, the number of votes that were cast was more than the estimated number of members of the respective communities, while on the other hand persons were also successfully elected who obviously or presumably did not belong to the specific ethnic group. The latter phenomenon of ethnobusiness seriously eroded the community legitimacy of the minority bodies.

Similar concerns about ethnobusiness have also been raised in Serbia, where, until the adoption of the 2009 law on national minority councils and the switch to direct elections, the legitimacy of minority bodies was also highly contested, but from a different perspective. In this case there was no official system of registration, and only minority MPs, minority provincial and local councilors, and nominated representatives had the right to form an electoral assembly. Nowadays, however, following the introduction of direct elections, minority political parties fear the possibility that the autonomous councils may be hijacked by mainstream political actors, by Serbian majority parties which may find their own candidates and sponsor their own lists (Beretka Reference Beretka, Levente, Sergiu, Alexander and István Gergő2014, 264–265).

The issue of legitimacy has also been raised in Croatia from yet another perspective. In this case, extremely low turnouts were recorded, probably because of the absence of appropriate capacities and results as well as the unclear mandate of the MSGs, the lack of willingness of municipalities to support these minority bodies, and, not least, the fact that minority elections were not on the same day as local elections (Petričušić Reference Petričušić, Tove, Osipov and Vizi2015, 63–64; see Table 5).Footnote 12

Table 5. Voter turnout at elections of national minority councils in Croatia, 2003-2011 (%).iii

iii Source: http://www.izbori.hr (accessed November 20, 2018).

The function of providing legitimacy is closely related to other factors such as the control that is granted over those who are elected. Since many view representation as a cyclical process involving three key elements (authorization, representation, and accountability), enforcing political accountability is also a crucial, yet usually the weakest, component of elections.

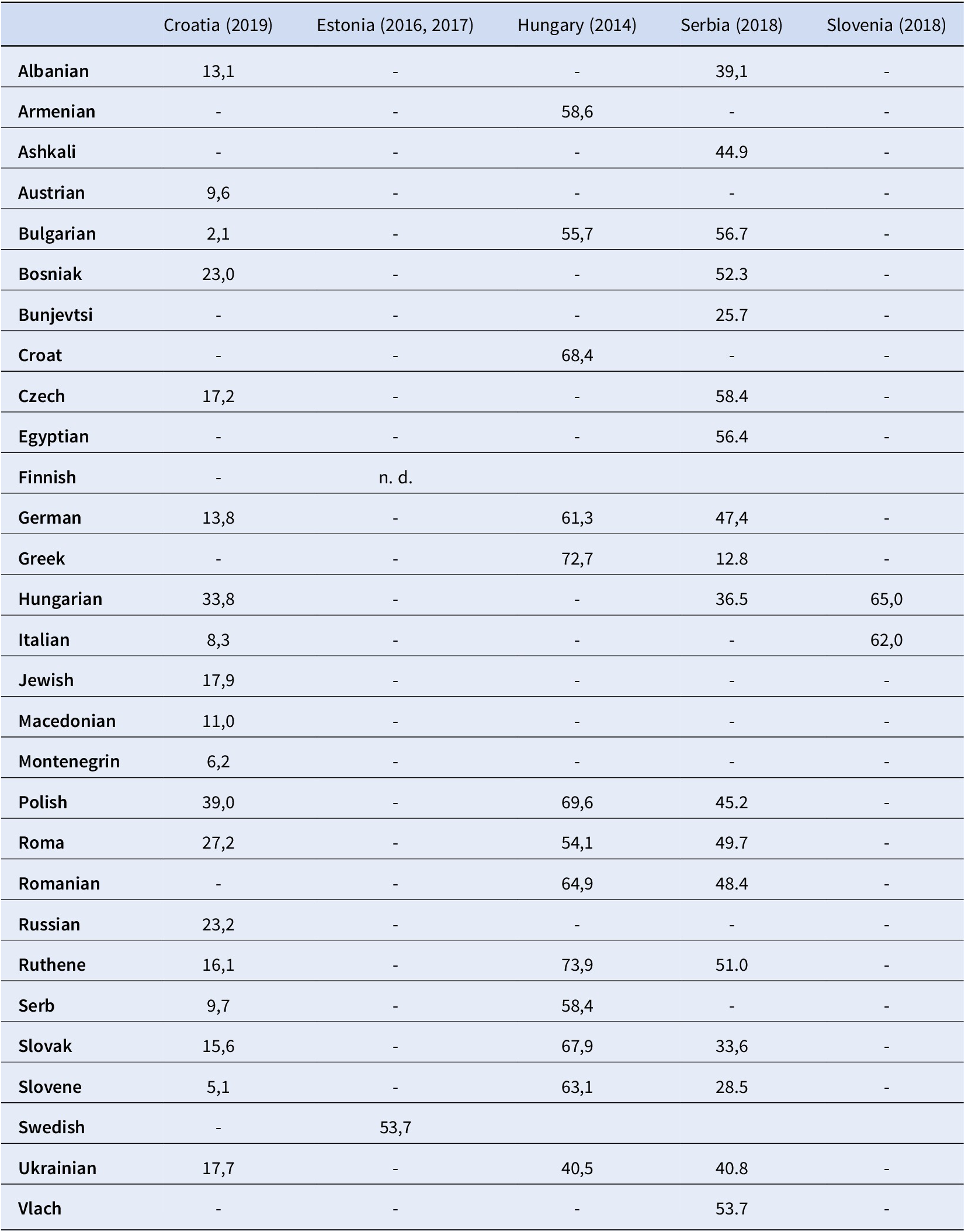

Electoral Participation

Both legitimacy and accountability are closely intertwined with the assumption that voters are encouraged and required to participate in elections primarily by registering themselves and casting their votes. The idea is that elections may create more accountable, effective, transparent, and potentially more visible organizations that have the maximum potential to unite and mobilize communities. In practice, however, relatively low voter turnouts have been recorded, especially in the first elections of minority councils in Croatia (Table 5). Even in Hungary, which has probably seen the highest turnouts, the data indicate a decline in most cases from one election to the next. Nonetheless, minority voters in Hungary were more active than in Serbia, where the average voter turnout was well below 50% in the latest 2018 minority elections (Table 6).

Table 6. Voter turnouts at the latest (direct) NTA elections in Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Serbia and Slovenia (%).iv

iv Sources: Croatia: http://www.izbori.hr Estonia: http://www.eestirootslane.ee/sv/2016 Hungary: www.valasztas.hu Serbia: Republic Electoral Commission. Izbori za članove nacionalnih saveta nacionalnih manjina, 2018. godine. http://www.rik.parlament.gov.rs/latinica/izbori-za-nsnm-2018.php Slovenia: municipal websites (accessed November 20, 2018).

The behavior of voters is certainly influenced by a number of factors, including individual-level variables. Nevertheless, it is particularly important to assess how electoral systems affect people and how institutions constrain them, with special emphasis on the procedures of electoral registration and their perceived efficacy, the utility of voting (voter turnout), as well as on the impact on supporters of both large and small parties. In this regard, it is often held that list-proportional electoral systems are more likely to result in higher turnouts, since they encourage greater competition, parties are more interested in contesting elections, and, not least, voters become more motivated to vote (Birch Reference Birch2003, 79). However, in 2014 only a weak correlation between the number of lists and voter turnout could be identified in the case of Serbia (0,18), and a moderate one (0,45) for the elections of national MSGs in Hungary. Therefore, it is not only important to understand how community leaders, ethnic activists, and minority organizations seek to mobilize support and integrate less-committed members, but also whether voters rationally calculate potential utilities, the extent to which voters identify themselves with certain minority organizations, whether they perceive that that participation is of real value, and whether the forces of demand and supply meet in these contexts. The socio-demographic and economic background of voters seems to matter: for instance, low educational level, low income or unemployment, and poor living conditions are usually associated with lower rates of political participation. The relatively low turnout of the marginalized Roma communities in both Hungary and Serbia might support this assumption.

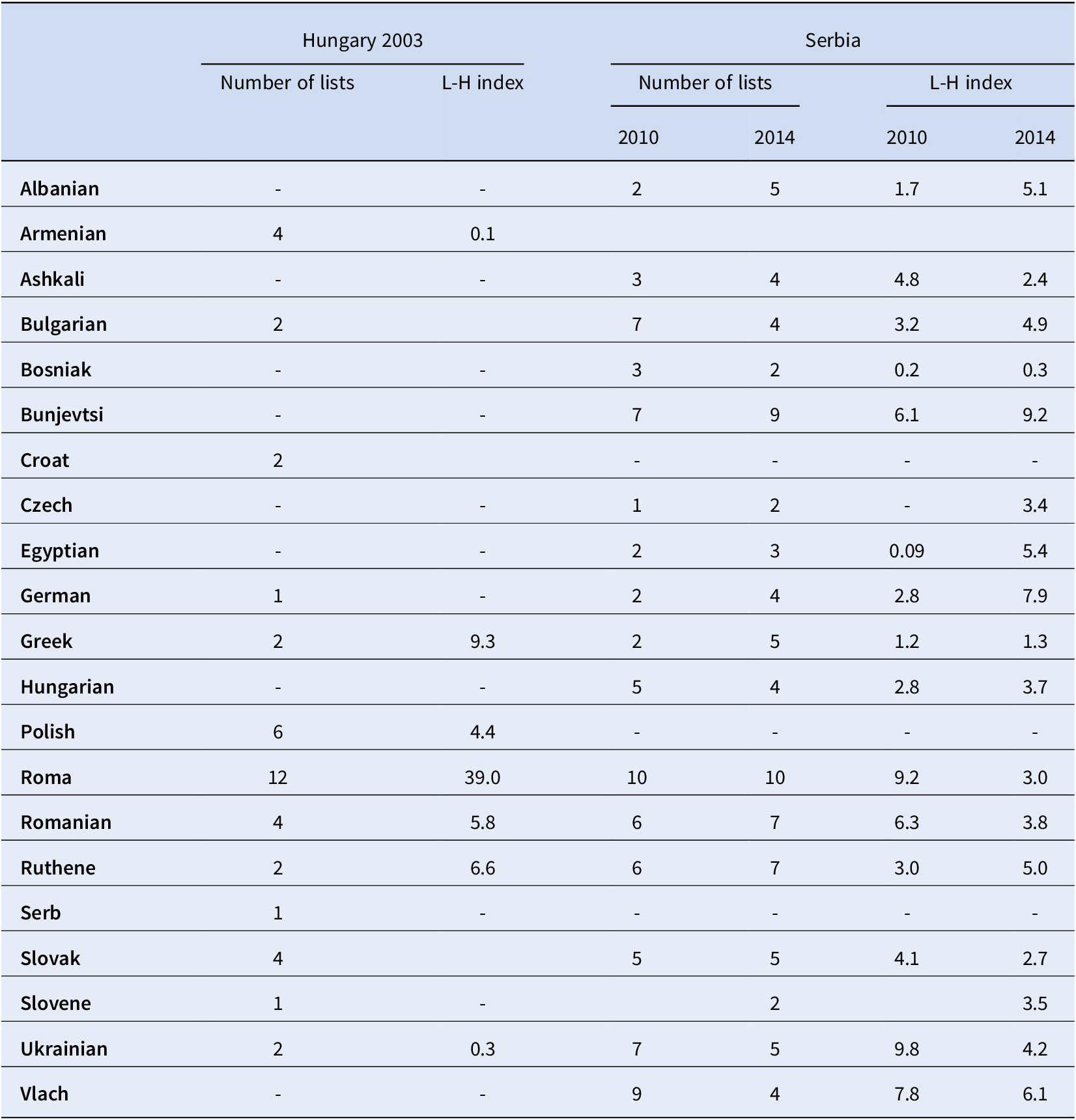

Electoral Formula

Last but not least, attention must be given to one of the main components of electoral systems – namely, the extent to which elections reflect voters’ preferences and patterns of potential internal cleavages – and the resultant configuration of minority parties and organizations. Given that most of the groups under analysis live scattered across the countries in which they live, one has to consider not only whether and to what extent election results reflect accurately their territorial distribution, but also the impact of the adopted electoral formula (majoritarian, proportional, or mixed): in other words, whether proportional electoral systems really are more representative and can more effectively reduce intra-community rivalries or whether, as noted above, they foster differences among subgroups (Norris Reference Norris2004), including ethnic outbidding. Understanding this issue requires an analysis of whether and how the electoral systems force parties to express or aggregate diverse opinions, strengthen partisan attachments, offer greater choice, whether they lead to more fragmented party structures and electoral results, and whether they benefit more entrenched parties and foster durable coalitions. In Hungary, for instance, the majoritarian elections at a national level between 1995 and 2006 resulted in highly disproportionate minority bodies (especially when compared with the Serbian proportional results) in which quite divided communities, such as the Roma, relatively large segments of civil society and other influential organizations that received a significant amount of votes were only able to obtain a few seats or none at all, as demonstrated by the Loosemore-Hanby index (Table 7).Footnote 13 The switch to list-proportional elections after 2006 resulted in a more proportional composition of representative bodies, although the total number of competing organizations has constantly increased over time.

Table 7. The 2003 elections of selected national MSGs in Hungary and the 2010 and 2014 elections of national councils in Serbia (Loosemore-Hanby index).

Conclusions

This article has sought to highlight and address the question of whether and how some of the main functions of elections can be conceptualized and understood in special minority contexts. Concerning the elected NTA regimes of Central and South Eastern Europe, very little research has been carried out to explore key and closely intertwined features and effects of minority elections on intra-community dynamics and voters’ behavior. These include features such as special voter registration, electoral formula (proportionality/disproportionality), ballot structure and voter turnout, taking into account also the sensitive nature of ethnic data, the relatively high level of cultural-linguistic assimilation, and the internal democracy of the minority communities. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to fill the existing gap in the literature at least in part, by identifying and examining the practical operation of NTA elections. A more in-depth analysis of the important elements of electoral processes requires further research. In this regard, important future areas of enquiry could relate to the logic and process of candidate selection and the relationship between minority constituents and representatives. Moreover, there is a significant lack of data about how the electoral systems and their incentives shape voters’ perceptions of electoral systems as well as parties’ behavior and strategies, on how proportionality/disproportionality and competitiveness affect efficacy and voter turnout, how these influence the number of competing and elected parties, whether they generate a more stable or divided leadership, and whether they moderate or encourage competition and internal rivalry. Taken together, these factors have a crucial influence on effective voter participation, as well as on the future prospects of minority communities.

Acknowledgements.

Earlier versions and parts of the article were presented in talks at the 22nd (New York, Columbia University, May 4–6, 2017) and the 23rd ASN World Conventions (New York, Columbia University, May 3–5, 2018), and the conference “National Minority Rights and Democratic Political Community” organized jointly by the University of Glasgow and the Babes-Bolyai University (Cluj-Napoca, May 19–20 2017). I would like to thank you Stephen Deets, Philip Howe, Benjamin McClelland, Alexander Osipov, David Smith, Christina Zuber, and the anonymous referees for their very helpful comments. I also thank the numerous people who supported my field research in Estonia, Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, and Slovenia and all my interview partners for their time. The field research was financially supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office–NKFIH (under grant number PD/116168).

Financial Support.

This work was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Disclosure.

Author has nothing to disclose.