Introduction

Discussing the (re)invented character of the nation is not a novel idea. Several historians and researchers of nationalism have focussed on this subject for many years. Neither is it unusual to talk about the role of history as a source of legitimacy in this nation-building. However, few people have studied the role that monarchy played in all of this. This despite the fact that, as Michael Billig stressed, “the recreation of monarchy in its popular, constitutional form was directly related to the formation of the national state” (Reference Billig1992, 25). The institution possessed the authority and legitimacy conferred by tradition. Nevertheless, it had to transform itself to survive in the nascent liberal, nationalist postrevolutionary world.

In this article, I argue that nationalism had a noticeable function in the monarchy’s survival. However, the institution also served liberal nationalism as an element of legitimacy, which led them to nationalize it and to appropriate its background. The key element that connected both processes was history. Focusing on the Spanish case, I reason that the monarchy’s history was intensively used in Isabel II’s reign (1833–1868) by monarchs and nationalist elites to justify their presence. In the end, the crown’s inherent connection with the past achieved two main purposes: to anchor the nation in the mists of time and to generate national emotions of a collective sense of belonging. The monarchy acted as a living reminder, a personification, and a performance of an idealized past that generated national experiences to encourage their present regeneration.

This article starts from current discussions and uses the vast and fertile range of sources characteristic of the cultural history of politics to formulate its proposal. I first locate the problem in a much more general context, one that touched all European crowned heads. I then analyze the two central sources used for the nationalisation of the monarchy’s past: comparisons with glorious, age-old examples and the search for an idealized, heroic golden age in the Middle Ages.

The Monarchy and the Nationalization of the Past

Historians demonstrated long ago the constructed or invented nature of the nation. With new or old materials, nationalisms provided a sense to a new political subject through symbols, traditions, and myths that were steadily being reformulated. History had a privileged place among them all. As Ernest Renan said, “A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle” formed by “the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories” and “the desire to live together” (Reference Renan1887, 306). In the end, nationalism is “a form of historicist culture” that pursues “an abstract community of history and destiny” (Smith Reference Smith1991, 91). Nations thus had their roots in the mists of time, following a fixed scheme that included a lost golden age that must be recovered. As Anthony D. Smith said, the nation must not only “boast a distant past on which to base its promise of immortality; it must be able to unfold a glorious past, a golden age of saints and heroes, to give meaning to its promise of restoration and dignity” (161).

The monarchy would serve nationalism remarkably well in this imagining of the national past. As Michael Billig pointed out, the crown enabled it to be imagined as a community and conferred “an imagined antiquity” (Reference Billig1992, 26) on the state based on its ancient lineage. So, as Benedict Anderson stressed, “It was obviously tempting to decipher the community’s past in antique dynasties” (Reference Anderson1983, 109) to these imagined communities that regarded themselves as somehow ancient. Antiquity was above all the longed-for historical legitimacy by liberalism. Eventually, as Eric J. Hobsbawm noted, the monarchy was one of those “proto-national bonds” that produced “the consciousness of belonging or having belonged to a lasting political entity” (Reference Hobsbawm1990, 73). As an “autonomous or intermediate instance,” the institution provided “citizen loyalty to, and identification with, the state and ruling system” (82). Nevertheless, it was first necessary to provide it with a “national cachet” (Anderson Reference Anderson1983, 22), “a new, or at least a supplementary, national foundation” (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1990, 84) to its traditional legitimacy that justified its permanence in the liberal system (Langewiesche Reference Langewiesche2013; Banerjee, Backerra, and Sarti Reference Banerjee, Backerra and Sarti2017; Sellin Reference Sellin2018). Nationalized dynasties thus served nationalism as a source of legitimacy and permanent remembrance of the nation’s greatness.

The most representative and best-studied case on these issues is probably that of Queen Victoria. The assumption of her national identity was relatively early. On June 23, 1837, three days after her coronation, her uncle, King Leopold II of the Belgians, advised her avowedly to highlight the fact that she was born in England. On the basis that the English “are really almost ridiculous in their own exaggerated praise of themselves,” he advised Victoria that “being very national is highly important” (Benson and Esher Reference Benson and Esher1908, 1:78–79). The result was more than satisfactory. Despite her Germanic origin, Victoria would represent and condense all Englishness’s virtues (Williams Reference Williams1997, 153–189). Thus, she personified “the highest type of English lady, English wife, and English mother” (Morning Post, January 26, 1858). In this way, the monarchy, the queen, and the royal family were identified with the nation and, consequently, with its honor, its pride, and its grandeur. Prince Albert’s death in 1861 would accelerate this allegorical fusion insomuch as he was closely associated with the Germanic world, especially after the Crimean War (1853–1856). This fact—combined with the imperialism that dominated the European fin de siècle—led to the merging of Queen Victoria and the British nation, even in an iconographic way (Bell Reference Bell2006). The process would reach the point of mixing the concepts of the Victorian and the narratives of Englishness (Langland Reference Langland, Homans and Munich1997).

Beyond stressing this historical process, the decisive role that the history of the monarchy and its historical actors played must be pointed out. In the end, one of the main arguments employed by liberalism to justify the monarchy’s permanence in the modern world was precisely its ability to anchor and legitimate the nation in the past. So, the crown served to Romantic nationalism in its search for national foundations in glorious, past times (Mandler Reference Mandler, Brockliss and Eastwood1996; Kumar Reference Kumar2015). To do so, it used two main mechanisms. Firstly, the crown appealed to historical precedents in the form of exemplary monarchs. The fact that she was a reigning queen made Victoria and the Victorians turn their attention early to her immediate precedent, Elizabeth I, so that “Victoria’s queenship could be legitimated and elaborated by this powerful fantasy of Gloriana” (Watson Reference Watson, Homans and Munich1997, 81). Consequently, the Elizabethan era was constructed as a mirror reflecting the Victorian present, justifying and legitimating its national-imperial plan. Queen Elizabeth’s two bodies were dissected by contemporary biographies and history painting, removing her natural body as a woman—a bit tricky to be integrated into 19th-century, middle-class domesticity—and focusing on the glorious one as a national idol (Langland Reference Langland, Homans and Munich1997, 27–29). Victoria was thus identified with Elizabeth, and the Victorian reign was presented as the zenith of a process of technical modernization, imperial expansion, and domination of the seas that had its roots in Elizabethan times. The monarchy appeared as the guarantor of national greatness, as a conveyor belt that anchored the nation to ancient and glorious times.

This comparison between the queens was integrated into a nationalist discourse that praised the medieval past in a hunt for national roots (Girouard Reference Girouard1985; Barczewki Reference Barczewki2000). For example, the construction and decoration of the new Parliament reproduced it in stone and canvas. The pictorial and sculptural decorations recreated this national idealism based on Arthurian legends. In all of them, chivalry was modernized and presented as an ideal of service to the monarchy, which appeared like a living memory of that glorious past (Mancoff Reference Mancoff, Riding and Riding2000). This discourse went beyond images to enter a performative level. Without leaving the parliament, Queen Victoria staged in the State Opening of Parliament a theatrical play of power in which she represented the legitimating force of national history. With the monarchy in the center, the ceremony performed the British constitution—putting “the three estates of the realm on parade”—and depicted “the pageant of the nation’s history,” complementing the images and sculptures that were filling the palace walls (Cannadine Reference Cannadine, Riding and Riding2000, 16–17). In that performative sense, the strength that the historical fancy-dress ball had in the 19th century cannot be overlooked. This popular entertainment of Victorian elites was connecting nationalism, history, and its internalization (Thrush Reference Thrush and Felber2007). On May 12, 1842, Victoria and Albert gave a ball to promote the declining silk industry. The historical theme was not innocent but referred precisely to medieval times. Dressed as Edward III—Order of the Garter founder, based on Arthurian legends—and Philippa of Hainaut, the royal couple were identified with this retrospective nationalism that found in the chivalry of medieval England a splendorous and ancient origin.

The use of the national past as a legitimating mechanism for the monarchy was not only reduced to English nationalism; it found an echo in other territories with particular identities. Leaving Queen Victoria’s problems with Celtic regions aside (Davies Reference Davies, Jenkins and Smith1988; Loughlin Reference Loughlin2007), her special connection with Scotland reproduced some of these patterns. The monarchy was closely identified with Highlandism (Morrison Reference Morrison and Marsden2010), a movement that essentialized Scottishness in the Highlands and the tartanry. The whole royal family, and particularly the heir, used to appear in public wearing tartan even in London, as happened at the Great Exhibition opening (1851). Their annual visits to Balmoral castle made a notable contribution to this cultural fusion. Nevertheless, these practices added to a historical reflection that presented Victoria as “the historical outcome of the Union of the Crowns” (Finlay Reference Finlay, Cowan and Finlay2002, 219). Visiting significant historical places for Scottish history and incorporating “many of the Jacobite myths into her own sense of Scottish identity,” Victoria’s reign succeeded in adapting her “to the threads of Scottish history” and configuring “the appearance of historical continuity” (219).

Likewise, Queen Victoria was not an exception among her European cousins. The use of history from theory and performance as a mechanism of national legitimation was common to all 19th-century monarchies, whether old or new. Among the first, the Austrian Empire is particularly interesting for its multinational state dynamics and continued self-reinvention. The neoabsolutist offensive promoted by Emperor Franz Joseph after his ascension to the throne (1848) sought precisely to secure its legitimacy in the history and imperial tradition of the 17th century against revolution (Unowsky Reference Unowsky2005). Successive military defeats forced the emperor to liberalize the regimen and to form a new state in 1867, the Dual Monarchy, between Austria and Hungary, a new state notion with different national loyalties in which the monarchy–particularly the Empress Elizabeth—played a crucial unifying role with the resource, once again, of the history. The coronation ceremony as monarchs of Hungary (1867) and the millennial celebrations of the Magyar nation (1896) witnessed the performance of the archaic symbols and rituals reinvented in the national remembrance. Equally, Empress Elizabeth—an authentic Magyarophile and fully implicated with the Hungarian cause—was equated with St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207–1231), the medieval princess of Thuringia associated with charity and political mediation (Freifeld Reference Freifeld, Cole and Unowsky2009; Szapor Reference Szapor and Schwartz2010).

The use of history is perhaps most evident among those new monarchies’ need for greater legitimacy. Napoleon III did not hesitate to establish his power on the medieval elective monarchy and the imperial memory of his uncle. But he also used history to build the modernity of his reign against the despotic and archaic Bourbons (Truesdell Reference Truesdell1997, 74–80; Glikman Reference Glikman2013, 394–411). The German and Italian unifications in the 1870s forced the new national dynasties to turn to their histories to demonstrate just how German (Hanisch Reference Hanisch, Birke and Kettenacker1989; Giloi Reference Giloi2013) and Italian (Mazzonis Reference Mazzonis2003; Brice Reference Brice2010) they were. Even in Mexico, the foreign Emperor Maximilian had to incorporate Mexican historical roots to the new imperial symbolic system (Pani Reference Pani1995, 439–54). For that purpose, the Austrian-born imperial family made special efforts to show themselves as purely Mexicans, speaking, dressing, eating, and behaving as such.

The Spanish monarchy was integrated into this much more general process that touched all crowned heads (San Narciso, Barral-Martínez, and Armenteros Reference San Narciso, Barral-Martínez and Armenteros2021). The assertion that “the monarchy hindered the Spaniard’s nationalisation and the crown’s identification with the Spanish nation” (Riquer Reference Borja de2001, 53–54) needs at least some clarification. During Isabel II’s reign, the crown had to adapt to the liberal challenges and undergo nationalism (Romeo and Millán Reference Romeo and Millán2013; Sánchez Reference Sánchez2019b; San Narciso Reference San Narciso2020). On the one hand, the monarchy was actively involved in the definition and transmission of Spanish national identity. Its resources were numerous and diverse, from travels and ceremonies to cultural patronage and symbolic gestures. However, the fact is that it acted as a national agency; it powerfully communicated a national narrative that ended up associating the monarchy with national symbols. Equally, liberal nationalism appropriated the institution in its political and cultural dimensions (García-Monerris, Moreno, and Marcuello Reference García-Monerris, Moreno and Marcuello2013). The integration in its structures and social world view entailed using the monarchy’s historical authority and exploiting its image, symbols, and rituals. Tomás Pérez-Vejo (Reference Pérez-Vejo2015) has clearly showed it in the cultural policy supported by both conservative and progressive governments. History painting commissioned or rewarded in National Exhibitions emphasized the monarchy’s presence as the main protagonist or symbolic marker. A similar thing can be observed in the banal use of the queen’s image in coins and stamps (Sánchez Reference Sánchez2019a). Liberal historiography has also followed a similar path. As Roberto López-Vela wrote, the monarchy “condensed Spanish political unity, the head and institutional incarnation of the Spanish people, and even its awareness” in the general histories (Reference López-Vela and García-Cárcel2004, 224). These visual and academic discourses represented prominent episodes in the national history, mixing the monarchy and the nation’s past.

Medieval Monarchs for a Romantic Nationalism

As many European nationalisms, the Spanish liberalism located its foundational myths in an idealized image of the medieval era (Nieto Reference Nieto2007; Evans and Marchal Reference Evans and Marchal2011). From historiographical theory and practice, authors saw then a dreamland of lost freedoms that branded the Spanish character (Cirujano, Elorriaga and Pérez-Garzón Reference Cirujano, Elorriaga and Pérez-Garzón1985; Esteban Reference Esteban, Morales, Fusi and de Blas2013; Álvarez-Junco and Fuente Reference Álvarez-Junco and de la Fuente2017). The ensuing story was a titanic fight of a people struggling for their freedom and independence from external subjects, be they the Muslims of 711 or the Napoleonic French of 1808. Despite essentializing the Spanish nation in the mists of time, liberal historiography dated the birth of a national state to the Visigoth monarchy after the fall of Rome. Those Barbarians, merged with primitive Spaniards, would provide a threefold unity—territorial, legal, and religious—that gave entity to the nation. As Modesto Lafuente wrote, “The Visigoths were those who founded a nation in Spain, declared the same cult that subsists today, gave the people laws that are still revered, held assemblies that will always be admired and respected, the same ones, in short, who bequeathed to the kings of Spain their most glorious title” (Reference Lafuente1887, 2:37)

The Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula dynamited that glorious edifice and withdrew the Spanish Christians to the Asturian mountains, the nation’s last bastion. The Reconquest would be glossed as an epic fight for Spain to regain its territorial unity, its independence, and its political freedoms, that is, for its national identity (Ríos Reference Ríos2011). All these historical assertions had their consequent political translation. Liberalism legitimized its current demands for liberty, independence, and political representation in Spain’s history. Therefore, they presented the liberal struggle as a fight to recapture the national essence, located in a medieval past that united the Visigoth monarchy with the Catholic Monarchs (Álvarez-Alonso Reference Álvarez-Alonso2000). The crown thus played a crucial role in these political and historiographical dimensions.

Maria Cristina’s regency period (1833–1840) was especially eloquent in the use of these past references. With the death of Fernando VII in 1833, a three-year-old girl became queen, Isabel II. This succession was contested by her uncle, Prince Carlos Maria Isidro, in a cruel civil war (1833–1840) that confronted liberalism and absolutism. In this complicated military situation and contested legitimacy, the queen regent used history painting as a propaganda weapon to reinforce her daughter’s legitimacy and her role as a regent (Díez-García Reference Díez-García2010, 29–32). Thus, a variety of political and moral references were sought in the past to show the vigour of the monarchy as a national guardian. For there was no lack “in Spain of examples of princes who disputed the crown with their kings” nor others of “the pleasure with which females have ruled these kingdoms several times” (Revista Española, October 25, 1833). To this end, shortly after assuming the regency, she commissioned a series of paintings whose topic revolved around two women regents of Castile, Berenguela (1180–1246) and Maria de Molina (1259–1321), at essential moments in the consolidation of their sons’ power.Footnote 1

Maria Cristina’s identification with these two former queens went beyond the monarchy’s own agency, and it was widely diffused within liberalism. The queen governor would invariably be described by the liberal press as “the Berenguela of our times” or “our new Maria de Molina” (El Español, April 25, 1837). To give her these nicknames implied associating her with all the background and values that her medieval counterparts embodied in the liberal nationalist imaginary. Maria Cristina has to fulfil some personal attributes as “a virtuous and devoted wife, a merciful queen, and lover of her people” who “knows how to combine the charming affability of her sex, the dignity, and significance of her high class” (Revista Española, April 27, 1836). To these personal traits were added other political ones, linked mainly to the civil war and the nation’s providential destiny. The past examples of these queens projected on Spain a peaceful, unitary, and fortunate future through the monarchy’s agency because “the glory of H. M. surges in the whole nation” (Revista Española, October 12, 1835). As that same newspaper recalled, “many queens whom history reveres fairly as heroines of their century, have found themselves in such critical circumstances […]. Berenguela and Isabel of Castile came to power in a period of civil crisis. The famous Maria de Molina resisted all the rage of the popular agitations” (Revista Española, October 12, 1835). Just as the nation did then, now with Maria Cristina, it would regain its unity and glory.

These discourses were echoed within liberalism in different formats. For example, to celebrate the queen regent’s birthday in 1837, the drama Doña María de Molina, written by the liberal-conservative Marquis de Molins, was premiered. But the words that he put in the past had much more force in his present. The play steadily draws a parallel between the biographies of the two queen regents. However, the major appeals are around two issues. Firstly, the fratricidal struggle experienced at the end of the 13th century and that which was then taking place with the First Carlist War (1833–1840). The comparisons were smooth between the queen regents (Maria de Molina and Maria Cristina), the uncles who dispute the throne (Princes Juan de Castilla and Carlos Maria Isidro), and the younger heirs (Fernando IV and Isabel II). Likewise, the most common trope appears with the defence of liberalism, hence anchoring modern liberties in the medieval era. Criticizing her opponent’s despotism, Maria de Molina says that “there are also kings who hock their crowns in defence of liberty and the exalted Pelayo’s throne” (Roca de Togores Reference Roca de Togores1837, 47). She even states that the people “defend their sacred laws alongside the sons of their kings, because throne and liberty are the same today; that is why they will triumph” (48). The final scene perfectly sums up the thread that united the past and present with the monarchy. The deputy Alfonso Martínez recommends Maria de Molina to educate the young king on the precept “that he does not owe life, throne, and freedom to courtiers but honest citizens” (148). The meaning that the words took on was greater in the present of 1837 than in the idealized past of 1296. The interesting thing is the broad agreement generated on these forceful ideas. Progressive liberalism recognized in this debut a convenient choice because “the Castilian people fighting for freedom and their legitimate king present exactly the animated picture of our glorious revolution” (Eco del Comercio, July 29, 1837).

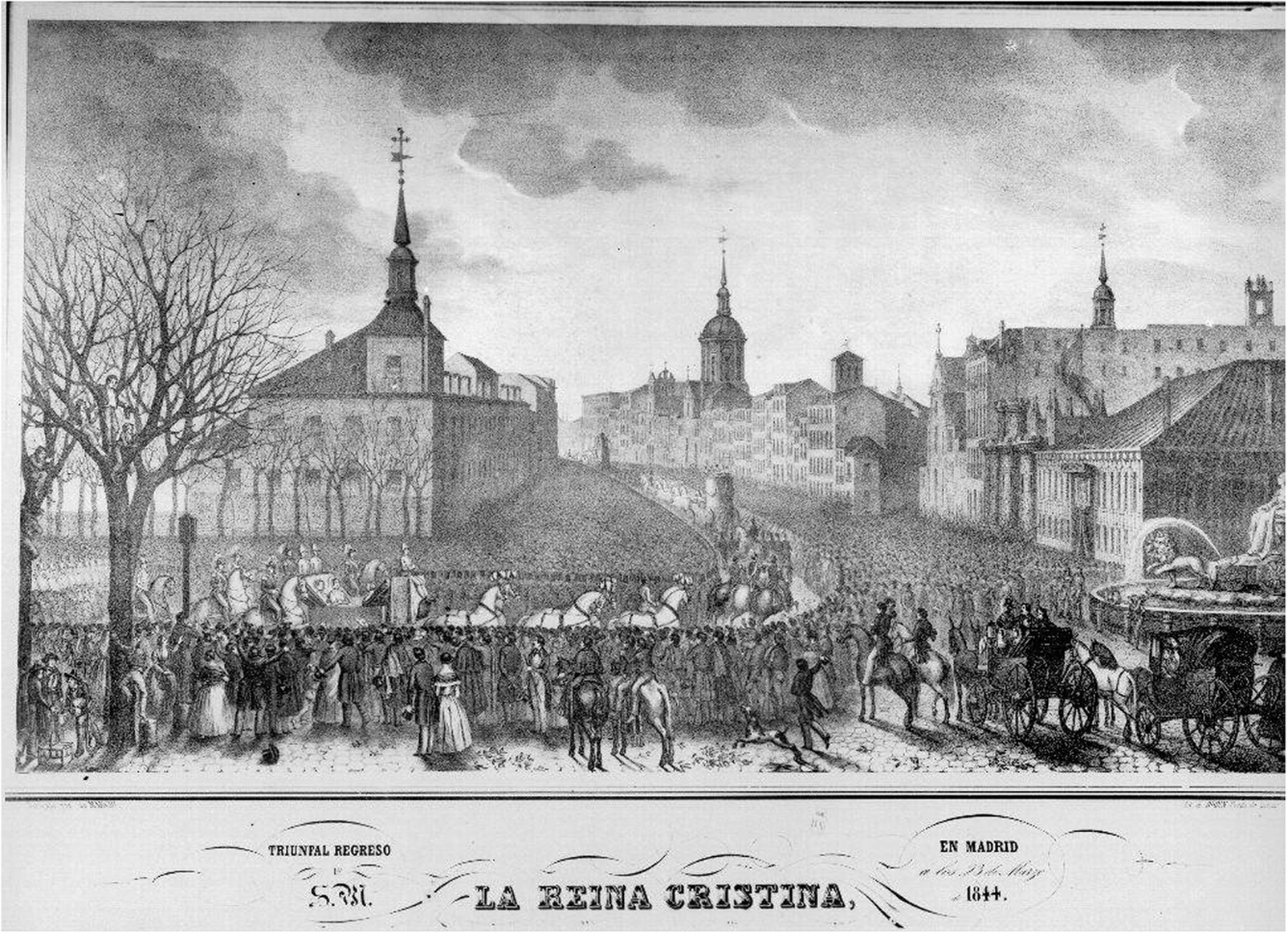

Figure 1. Triumphal return of Maria Cristina, Madrid History Museum, Sig. 152853.

This association would remain, albeit dimly, during the first years of Isabel II’s reign (1843–1868). Following the variety of formats expressed, the representation developed in the public ceremonies of the queens in the 1840s is illustrative. The return of Maria Cristina to Madrid in 1844 from her exile [figure 1] took place amid a medieval fantasy that covered the facades, triumphal arches, and decorations of the main streets.Footnote 2 As in other parts of Europe, the Gothic style was recognized in these sceneries to be the national one because it referred to a splendorous past and condensed Spanishness (Panadero Reference Panadero1992). One of those palaces was reconverted into Segovia’s medieval castle, with its towers, battlements, and walls. Dominating those Gothic pavilions were “the portraits of Ms. Berenguela and Ms. Maria, queen governors, worthy of Spaniards’ respect, and of the reputation they enjoy for the wisdom and prudence with which they saved the State in the conflict of civil disagreements, fostered by the monarch’s minorities” (Semanario Pintoresco, April 7, 1844).

The recourse to the medieval past was not limited only to the queen regent but also extended to Isabel II. Besides Isabel the Catholic, some women associated with the monarchy in the Middle Ages were taken as references. Among them was the figure of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary. Her image was closely linked to the pictorial projects promoted by Isabel II within the royal palace or the churches intimately related to the Spanish monarchy (Díez-García Reference Díez-García2010, 76–84). Linked partially to this princess, and the virtues of compassion and Christian charity associated with her, was the biblical figure of Queen Esther. Thus, they maintained the rhetorical model, used as an ideal prototype for queens during the Middle Ages, in which she stood out as an intercessor between the king and his people. Isabel disguised herself as her for a historical fancy-dress ball at the Duke of Fernán-Nuñez’s palace [figure 2], where a troupe inspired by the Catholic Monarchs’ days marched in front of her (La Época, April 15, 1863). The queen appeared thus dressed in “the garment that best suited her noble and kind heart, that of Esther, a queen and liberator of an oppressed people” (Bravo and Sancho Reference Bravo and Sancho1884, 6).

Figure 2. Isable II dresssed as Queen Esther. Colección Fernández-Rivero

Beyond these references, the link of Isabel II with the medieval past will be significant in the national integration process of some regions with strong, particular identities. Undoubtedly, it was included in the regionalist historicism that was developing in Catalonia alongside Romanticism (Smith Reference Smith2014, 70–97). On her visit to Barcelona in 1860, the queen exhibited in a hand-kissing the county crown “in which Barcelona’s arms were embellished with the well-known Catalonia bands and big pearls on the tops” (La Época, September 27, 1860). Clothed as a medieval Countess of Barcelona, with the Berenguer crown built under the queen’s order and direction [figure 3], she came out to the main balcony to greet a crowd that went crazy when they saw her dressed with the traditional attributes of power (Flores Reference Flores1861, 325). This action was read in different ways. The conservative forces praised the ability to “harmonize historical and traditional memories with the demands of fashion, [linking] the past and the present” in this quest for the legitimacy of the monarchy in history (La España, September 28, 1860). The progressive press lauded it as a symbol of “the resurrection of national freedoms” and the defence of representative institutions anchored in medieval times (La Corona, September 24, 1860). However, in both cases, the monarchy appeared as a guarantor of the nation’s continuity, as an ever-present reminder of its greatness and vitality.

Figure 3. Isabel II dressed as medieval Countess of Barcelona, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Sig. 17/240/57.

These strategies of legitimization continued throughout the whole period and appeared on different occasions to the monarchy’s rescue. A clear example would be the uses given to Prince Alfonso, heir to the throne. His birth in 1857 took place within a convoluted political circumstance, where the role of Isabel II as a constitutional queen was questioned and her symbolic capital was gravely depleted by her political interference and reactionary inclinations (Burdiel Reference Burdiel2010, 488–575). In this climate, the monarchy would use the past to justify its current liberal position and offer a hopeful and empowering future. The name decided for the heir was included in these identity debates and historical interpretations. As one newspaper said, “The name of Alfonso is glorious in national history because it recalls the most prominent times of the Reconquest and the monarchs who contributed most to restoring our nationality and uplifting it with great noble deeds” (La Época, November 28, 1865). So, the choice was linked to “the intimate and firm hope that this name will come to represent for future generations another period of prosperity and glory” (La Época, November 28, 1865). The newborn had to combine in his person the virtues of the previous three medieval Alfonsos to become “one day a Catholic, Chaste, and Great King” (Juventud Ovetense Reference Ovetense1858). This discourse lasted a long time. Several years later, in the final crisis of Isabel II’s reign, it would appear again vigorously. In the press’s opinion, “the throne and the people make the historical commonwealth of our past times and will also determine the model of our future times” (La Época, January 23, 1865). So, they wished the young Alfonso “the glory and knowledge of his illustrious ancestors, the inspiration in his exemplary virtues to practice one day the constitutional monarchy” (La Época, January 23, 1865).

Nevertheless, the highest levels of usage were seen a few months later when the royal family travelled to Asturias to visit the Virgin of Covadonga’s sanctuary, a place with an enormous symbolic significance because Christians there, under Don Pelayo’s orders, halted the Muslim advance in 722. Within the centrality that the Reconquest had in the historicist narrative of Spanish nationalism, the region emerges as the “repository of our faith, traditions, and customs” where “the three great events that decided Spain’s fate [occurred]: the last and most stubborn uprising against the Romans, the first victory against the Saracens, and the spirited challenge to death to Napoleon” (Caunedo Reference Caunedo1858, 39). In this way, the journey was “a pious pilgrimage to the places where the faith revived, and the glories of the restoration began; to the cradle of the monarchy with the exalted Alfonso, the country’s hope, and an example for the future of his illustrious grandparents” (Boletín Oficial de La Coruña, September 15, 1858). Agreement was such that when the queen descended from the mountain, displaying “the tender prince from her carriage,” she “said to the people: behold him, he has been confirmed in Covadonga, and he also bears the name of Pelayo” (Rada Reference Juan de la1860, 564). According to the chronicles, this situation caused an outburst of public enthusiasm all the way to her palace in Gijon and obliged the queen and the prince to appear many times on the balcony amid the general jubilation.

The medieval past also played a prominent role in an essential function of the heir: the region’s integration within the nation. Through Alfonso, the monarchy achieved to incorporate the different regional identities into the Spanish national metaphors. The example of Galicia is paradigmatic in this respect. During their visit in 1858, it resorted to the local history, traditional sites of memory, and the myths and symbols that Romanticism was developing in a regionalist tone (Beramendi Reference Beramendi2007). But they were integrated into a nationalist interpretation that linked their present with the medieval struggle for freedom through the crown (Barral-Martínez Reference Barral-Martínez2015). Accordingly, the regional authorities and the Santiago de Compostela’s city council gave the prince “a beautiful golden crown” following “the ancient custom that declared governors and kings of Galicia to those who today hold the prince of Asturias title” (Rada Reference Juan de la1860, 755). In 1858, as in 1833, the appeal to the medieval past as a discursive strategy continued to maintain its strength as a mechanism to justify the monarchy in Spanish nationalism and to generate feelings of adherence through emotional appeal.

Land of Faith and Glory: The Remembrance of Isabel the Catholic

In the discourses on monarchy’s legitimation through its glorious national past, the figure of Isabel the Catholic (1451–1504) held a prominent position. Comparisons between her and Isabel II had such a quantitative and qualitative impact throughout the reign that they deserve a specific section. The homonymy certainly favored comparisons. But added to this was the interpretation that liberalism built of Queen Isabel I and the Catholic Monarchs’ period as a golden age of the Spanish nation. The paradigm was constructed at the beginning of the 19th century and would remain fixed throughout the century, being shared by an extensive ideological spectrum that even involved republicanism (López-Vela Reference López-Vela and García-Cárcel2004, 227–235; Álvarez-Junco and Fuente Reference Álvarez-Junco and de la Fuente2017, 265–287). Beyond the controversies about the creation of the Inquisition and the expulsion of the Jews, liberal nationalism understood the Catholic Monarchs’ reign as the culmination of the medieval myth of the nation. Isabel and Fernando had come by chance to the thrones of Castile and Aragon, managed to dominate their lands, and created a national unit, mainly in Castile, “the mother monarchy,” where it had reached “such a sorrowful state of decomposition, anarchy, and gloom that it seemed threatened by dissolution” (Lafuente Reference Lafuente1887, 8:3).

Thus, their marriage would mean the definitive unification of Spain—completing the Reconquest—and the nation’s reaching its highest point with the discovery of America and its predominance in Europe. As the progressive politician, Victor Balaguer even wrote, “Spain’s history begins with the Catholic Monarchs […] because what preceded these monarchs is the particular history of each of the nationalities or kingdoms located in the region of Spain” (Reference Balaguer1892, 1:3). The reign’s result was a nation, Spain, regenerated, unified, and glorious. As Modesto Lafuente wrote, under the Catholic Monarchs’ direction “the laborious restoration of 8 centuries [of reconquest] has been completed,” and Spain has regained “its desired independence.” Moreover, the division had “disappeared with the work of unity,” and a “wise, prudent, and efficient administration” had been established. But Spain also had “extended its power across both seas” and possessed “empires by provinces in both hemispheres” (Reference Lafuente1887, 8:36). It was the culmination of the nation’s heroic deed.

In this interpretation, the liberals considered Isabel and Fernando very differently, demonstrating a clear preference for the former. Even leading republicans, such as Emilio Castelar, wrote that “Isabel was a supernatural mystery,” and “although they were both outstanding, her greatness was plainer and more apparent” (Reference Castelar1892, 206). The queen was portrayed as a host of political and moral virtues that elevated her if not to saintliness, clearly to the first place of Spanish monarchs (Álvarez-Junco Reference Álvarez-Junco and Valdeón2004; López-Vela Reference López-Vela2007). Qualifying adjectives followed each other to the point of exhaustion. Besides being “the most discreet and sensible queen who has ever occupied the throne of Castile” (Lafuente Reference Lafuente1887, 8:15), Isabel combined all the domestic virtues, adapting it to the gender categories of liberal womanliness. So, she was “manly without being a degenerate female” (Juderías Reference Juderías1859, 68), and “if she took the strength from the other sex, she retained the decency and modesty from her own” (Clemencin Reference Clemencin1821, 37). As José Zorrilla summarized in a poem:

Isabel, in whose generous soul / God placed human goodness / pure, modest, noble, and pious, / was the greatest Queen on Earth. / Sweet and tender as well as vigorous, / diligent in peace, wise in war, / she rewarded the good, consoled the unhappy, / and she was a model of ladies and queens. / She gave her royal breath to Spain, / glory to her sex, and decorum to her epoch. (Reference Zorrilla1852, 2:48–49)

But among her accomplishments, these authors highlighted her effort to achieve national unity and build the state. It was a popular trope to see her as the creator of the Spanish nation, for she “extended the little kingdom that she had inherited in disgrace, and raised it, by herself, to the rank of a first-rate power” (Juderías Reference Juderías1859, 69). Modesto Lafuente even said she was the main executor of national unity due to “her prudent mixture of gentleness and severity, of temperance and rigor, of reward and punishment” (Reference Lafuente1887, 8:19). But there was also a central element: her deep respect for Cortes, which these authors saw in modern, national terms. Therefore, Isabel needed to “rely on the ordinary people to strengthen the throne’s authority” facing up to the aristocracy, opening up “to merit, talent, and virtue the paths of wealth and honour” (8:19). For Victor Balaguer, even Isabel’s authority emanated “from a revolutionary assembly, which could well have been of national sovereignty and so could be called national as well” (Reference Balaguer1892, 1: 5). Once again, their present resonated stronger here than the historical evidence.

This liberal myth of Isabel the Catholic enjoyed great popularity and, at times, achieved enormous vigor during the whole of Isabel II’s reign. It was activated from Isabel’s birth (1830) to reinforce the historical legitimacy of female succession.Footnote 3 In the public celebrations organized then, it was unquestionably the leading motif of the decorations that festooned Madrid. For example, the city council erected a pavilion with a matron representing Spain, who supported Isabel and offered her religion and the four moral virtues. A Ventura de la Vega’s poem stressed its meaning:

An Isabel, the pride of Castile, / red crosses fluttered in Granada, / expelling the Moor to the African seashore. / The one longed for by the homeland that today is born, / heaven destines for the paternal throne. / Holy religion, you will accompany her, / and the century of Isabel will be reborn in Spain. (El Correo, November 22, 1830)

These same tropes were seen in several poems printed and distributed then. For example, during the royal show at the Cruz Theatre, a Mariano José de Larra poem could be read that said, “God has fulfilled / the vow that faithful Spain made, / and sends us a new Isabel / to leave the Catholic one forgotten” (El Correo, November 22, 1830).

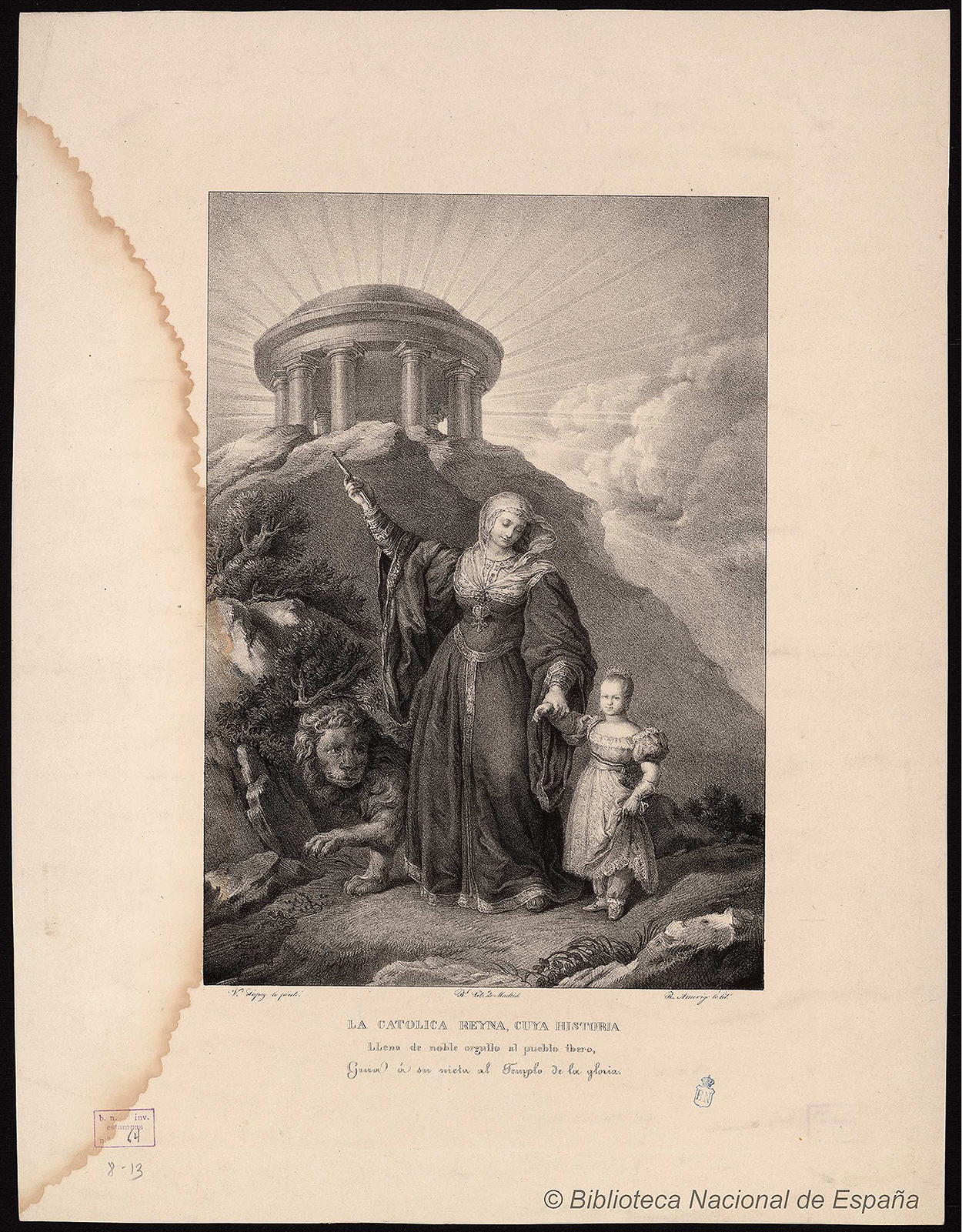

This comparison emerged vigorously at three significant moments of Isabel II’s power recognition and consolidation. History returned as a central element in the justification of a reigning queen, showing the glorious national past generated by Isabel the Catholic, and thus projecting a hopeful future for Spain. Her myth hovered over all the public celebrations that took place in the ceremony of her swearing in as the heiress to the throne in the summer of 1833. The goal was always the same. In a play written for the event, Manuel Bretón de Los Herreros put it in Don Pelayo’s mouth when he said to Isabel the Catholic, “Distinguished queen, / from Olympus on high where your chosen spirit dwells, / infuse your adorable successor / with the unselfish virtues that one day / inspired my glory to your heart” (Reference Bretón de Los Herreros1833a, 27). On the stage that turned Madrid into a Romantic Gothic dream, the facade of one palace stood out. On Gothic-arabesque latticework and between the pillars of Hercules—Spain’s heraldic symbols—there was a Vicente López painting representing “Isabel the Catholic, pointing to her granddaughter the second Isabel, the temple of immortality” and showing “at its base the text of the succession law” contained in the medieval Partidas (El Correo, June 21, 1833).Footnote 4 The image circulated in lithographs and became very famous [figure 4]. But the simile was analogously present in different formats. For example, the final scene of another Bretón de Los Herreros’ allegorical drama will eloquently stage this image. After the uncovering of the temple of glory presided by Isabel the Catholic’s statue, the figure of Time tells the Spanish people, “Ennobled by her throne, / rewarding your vassals’ love, / you will also know how to tread the arduous path / that led the eminent heroine / to the temple of glory” (Reference Bretón de Los Herreros1833b, 23).

Figure 4. Isabel the Catholic guides her granddaughter. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Sig. INVENT/27937.

These same images and narratives were used in Isabel’s proclamation ceremony as queen after Fernando VII’s death (October 24, 1833) and her oath of the constitution when she was declared of age (November 10, 1843). On this last occasion, Madrid’s progressive city council chose the adornments stressing these same tropes despite the ten-year gap. For example, on the decorations of the Paseo del Prado fountain, this could be read: “Isabel I’s elation / transmits to you today, oh queen, her halo / woven with the laurels of Granada / and the immortal palm of Cerignola” (El Heraldo, December 4, 1843). Equally, the main monument in the Plaza Mayor was adorned with verses: “If under Isabel I’s sceptre / we carry the banners of Castile, / now victorious over the fierce Moor, / to the remote American seashore, / today that you occupy / with its virtues, Isabel, the royal chair, / God keeps for your highest feat, / the union, peace, and freedom of Spain” (El Corresponsal, December 3, 1843). The French republican historian, Edgar Quinet, was travelling in Spain then and recorded his impressions. Among the events that took place, at the Principe Theatre he attended the play entitled The Shadow of Isabel I. Impressed by the metaphorical language and historical references, he admired the ordinary people’s “ability to understand these abstractions and to love them” (Quinet Reference Quinet1846, 39). But he especially highlighted the excitement caused by the “final appearance of the great Isabel the Catholic, who rose from her tomb with the book of the Constitution [of 1837] in her hand” (40).

Undeniably, the figure of Isabel the Catholic held enormous symbolic capital. Moreover, the queen occupied a leading role in the propaganda counterattack that the monarchy undertook in the profound crisis of political and symbolic legitimacy that followed the 1854 Revolution, which almost expelled Isabel II from the throne. In its attempt to become popular for liberalism, the monarchy would not hesitate to rescue her ancestor and use the past to justify its presence in a liberal nation. In that context, a pamphlet was published drawing a parallel between the queens. Written by José Güell, brother-in-law of the monarchs and linked to progressive liberalism, its aim was clear: to vindicate Isabel II’s reign by comparing it with that of Isabel the Catholic. Among the facts and works that the author reviews, two ideas took a prominent place. Firstly, if Isabel I built Spain as a political organization, Isabel II had achieved its union as a nation. Therefore, although Isabel the Catholic “made these three peoples [Castile, Aragon, and Navarre] a crown on her head, […] she did not unite the spirit of the natives into one nationality” (Güell Reference Güell1858, 48). Her heir, Isabel II, had “united those kingdoms separated by customs and immense distances,” verifying “the close national union that Isabel I could never achieve” (49). To this, he added the firm liberal foundation of both queens. In his opinion, Isabel I “was a queen created by national sovereignty.” In gratitude, she “gave the people the importance and favor that it has retained ever since” (81–83). Anchoring liberalism in the national history through the monarchy, he argued that “from the 15th century to the present, our liberal constitutional system [survived], more or less wholly in its structure, but entirely in essence” (97). This agreement was based on “the nation’s consent obtained in Parliament,” which was only violated by absolutism when “the homeland ceased to be a nation and became a king’s property” (94).

But this integration of the queens with the national liberal past was especially marked by the war between Spain and Morocco (1859–1861). The overblown so-called Africa War was an exercise in nationalist exaltation that sought to generate social consensus and provide stability to the government of the Liberal Union (Jover Reference Jover1991). With a strong emotional appeal, the war succeeded in mobilizing a very dissimilar nationalist discourse around a common foreign enemy (Álvarez-Junco Reference Álvarez-Junco2001, 511–516; Inarejos Reference Inarejos2007, 15–42; Blanco Reference Blanco2012, 27–47). Consensus, certainly, encompassed the whole political spectrum. Salustiano Olózaga, the leader of the progressive opposition, did not hesitate to support the government in Parliament. In his opinion, it was not the time for discussion, it was “the day to feel the immense pleasure of being all Spaniards and nothing but Spanish.”Footnote 5 Meanwhile, the conservative opposition also supported the government with similar arguments. As Luis González-Bravo said, Spain was “more than a nation, it was a race that awakens and marches to manfully achieve its destiny.”Footnote 6 Neither personal nor party interests were above all. The only important thing was “that Spain and our flag may triumph, that the dignity and the eminent interests of our nation are saving.”Footnote 7 The war, indeed, enjoyed an immense public popularity in all social layers, even in territories where noticeable regionalisms were developing (García-Balañà Reference García-Balañà and Martín2002; Cajal Reference Cajal, Esteban and de la Calle2010).

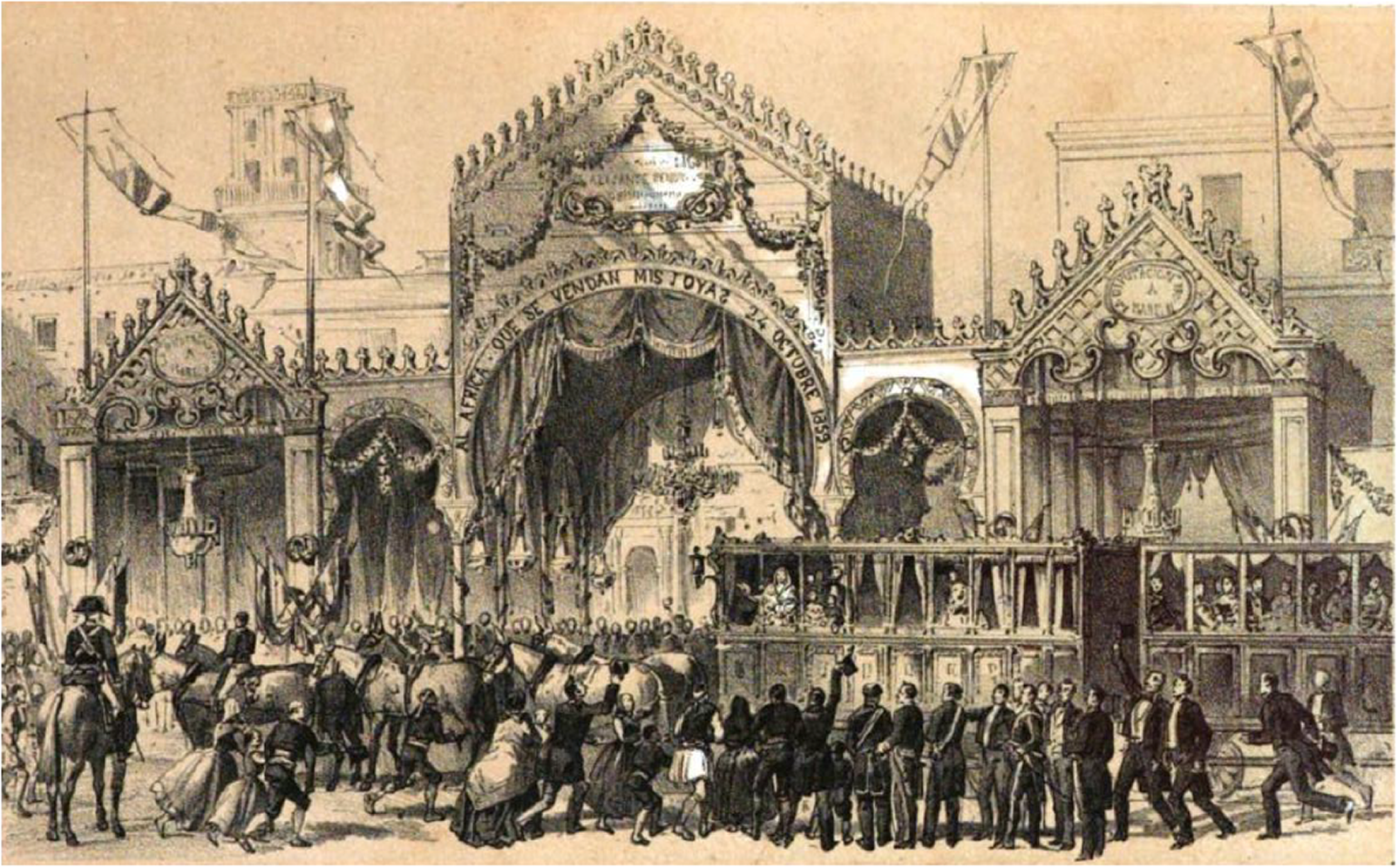

In this nationalist mobilization, the appeal to the Reconquest was a pivotal component. The war with Morocco thus became a contemporary manifestation of the glorious national past [figure 5]. As the British ambassador wrote to his government, “It would be impossible to do more to excite popular enthusiasm than Spanish public writers and public functionaries are now doing to make the nation believe that a link is being forged which is to unite a new era of power and glory with the days of past Spanish greatness.”Footnote 8 His French colleague would agree in reporting that “some of the enthusiasm shown by the population” was due to this historicist nature.Footnote 9 In short, “the war against the Moors is the remembrance of the Spanish monarchy’s ancient days, whose memory has been passed down from generation to generation to the current descendants of the Spaniards of Fernando and Isabel’s time.” In that way, soldiers “have only in their mouths the old Spanish cry from the great Isabel’s time: death to the Moors.”Footnote 10

Figure 5. El Mundo Pintoresco, October 23, 1859.

Liberalism gave, in this revival of the Reconquest, a leading role to Isabel I as its principal executor, with the occupation of Granada (1492) as the most memorable event. Two scenes from national history were repeatedly brought up: her decision to sell her jewellery to finance the conquest of Granada and the instruction she left in her will for her successors. On these core ideas, speeches followed one another in an endeavour to equate the queens. As the progressive politician Pedro Calvo-Asensio, said, “Providence guides Spain to go where the testament of a queen, celebrated for both her Catholicism and heroism, marked the path of Spain’s progress.”Footnote 11 In the Cabinet meeting headed by the queen to weigh the war declaration, Isabel II seems to have said that if “the nation’s honor and the future of the noble cause that the Spanish army is going to defend in Africa demand extraordinary sacrifices, she was willing to sacrifice her jewels and patrimony to cover the war necessities” (La Época, October 21, Reference Segura1859). It was a gesture, “worthy of a princess who occupies the RecaredoFootnote 12 throne,” which “involuntarily recalled another act by Isabel the Catholic when she tried to bring the light of Christianity and the shining Castilian banner to the New World” (La Época, October 21, Reference Segura1859). These tropes went beyond political discourses to acquire an enormous dissemination in widely popular formats. For example, Diego Segura’s patriotic drama included a scene in which, to celebrate a military victory, the courageous protagonist shouts out to his comrade-in-arms, “Magnanimous queen! Worthy emulator of Isabel the Catholic! Let my jewels be sold, let my pomp diminish, and my patrimony be available she said. A humble ribbon will shine on my neck better than threads of diamonds if these can serve to defend and raise the fame of our Spain. God save the queen!” (Reference Segura1859, 36).

The aim was always the same. The remembrance of Isabel the Catholic was brought to their present to cover Isabel II with her hopeful and glorious aura. So, by imitating the queen, the nation’s greatness would return. As one of the many proclamations made by the municipal institutions synthesized, “The 80 days campaign will figure in the history of our homeland as a worthy epilogue of the 8 centuries war” since “the heart of the first Isabel beats in Isabel II’s breast” (Boletín Oficial de Ciudad Real, February 7, 1860).

These ideas of equating both queens would become so strong in the imaginary from then on that they would remain intensely throughout the rest of the reign. The topic was especially visible in the tours that the monarchs took all over the country since 1858. For example, during her trip to the Basque Country, the local authorities organized a visit to Arriaga on September 12, 1865, the same day and place where Isabel the Catholic swore in 1473 “to respect and to make respect the holy Fueros” (Ortiz de Zárate Reference Ortiz de Zárate1865, 24).Footnote 13 It was also a repeated motif in the ephemeral ornaments that decorated cities next to the national flags. For example, on their trip to Alicante, the provincial government built a train station where it could be read [figure 6], “To Africa! Let my jewels be sold: October 24, 1859. To the sea! Let my jewellery be sold: August 3, 1492. The spirit of the Granada and Columbus Lady spread her wings: her encouragement gave life to Isabel II, and the former owner of the world regained her greatness” (Flores Reference Flores1861, 26).

Figure 6. The arrival of HH.MM. to the railway station. Photograph from Flores (Reference Flores1861, 25).

But it acquired a special significance during her trip to Granada in 1862, providing an eloquent performative sense. The remembrance of the Catholic Monarchs was present from their entrance into the city, which as the French ambassador said, reproduced “a magnificent parade representing the Catholic Monarchs’ entrance into Granada after their victory over the Moors” in 1492.Footnote 14 The next day, the queen’s birthday, the strategy of merging both queens was more evident than ever. In the morning, the university offered the queen a gold crown imitating that of Isabel the Catholic, preserved in the Royal Chapel of the cathedral. Quickly, Isabel II announced that “she would not wear another crown for the solemn ceremonies of that day” (Cos-Gayón Reference Cos-Gayón1863, 236). After the reception, the monarchs visited the cathedral and the Catholic Monarchs’ tomb, surrounded by the banners taken from the Moorish enemy. In the afternoon, public ceremonies continued. As the British ambassador confirms, Queen Isabel “wore the crown which had just been presented” in the vast hand kissing of authorities and dignitaries.Footnote 15 The queen also showed off this jewel that night in the spectacular ball that took place in the Alhambra Palace. As Ambassador Crampton emphasiszd, “Ages have elapsed since such a solemnity has been held by a Spanish Sovereign on this historic site.”Footnote 16 So, this event was seen as “a revival of the glorious recollections attached to the memory of a namesake and predecessor of the present Sovereign Isabel I.”Footnote 17 For this purpose, “repainting and regilding some of the Moorish Court and apartments was contemplated, but want of time fortunately prevented the completion of this act of barbarism.”Footnote 18 Instead, they attempted to reconstruct with modern furniture and objects the atmosphere of Isabel I’s time with “an absence of good taste on the part of those charged with the arrangement” and “a tawdry and unsatisfactory effect.”Footnote 19 However, the core of the event was the “colossal statue” of Isabel the Catholic built “on an islet,” inside the Arrayanes courtyard reservoir (La Época, October 14, 1862). Furthermore, on that day the queen, “always caring about the conservation of national glories,” signed a decree to restore the historical monument in commemoration of her first “visit to the Alhambra palace, a conquest of the first Isabel” (Boletín Oficial de Granada, October 10, 1862). The link established between the Alhambra, Isabel I, and national glory with the figure of Isabel II could not be more noticeable.

The mythical remembrance of Isabel the Catholic remained vigorous, and long lasting, as an archetype of the virtuous queen. She was a model of emulation by which the nation would regain the greatness that liberal nationalism ascribed to her reign. However, the comparison was not only done in favorable terms. The 1868 Revolution, which expelled Isabel II from the throne, appealed to this liberal myth as a counterpoint to the depraved and excessive queen (Burdiel Reference Burdiel2004). As the liberal-progressive politician Carlos Rubio said, the conservatives’ politicians “had persuaded Isabel II that Isabel I was the dawn, and she was the sun” (Reference Rubio1869, 1:203). However, circumstances and persons were significantly different, and the queen’s abilities were much poorer. Years later, in the transient and contentious Amadeo I’s reign (1871–1873), the acclaimed writer Benito Pérez-Galdós defended Queen Maria Victoria from Bourbon critics using the same arguments.Footnote 20 After all, “her virtues and domestic sense” had restored “to the nation’s highest home the prestige it enjoyed several years ago, in times of illustrious and haunting queens” (Revista de España, May 26, 1872). The criticism of the immoral Isabel II and the glorious spectre of Isabel the Catholic were hidden in his words. Thus, the example managed to locate the queen in the “middle-class tragedy” constructed by the liberal historicist memory (Schulte Reference Schulte2002). But it also integrated her into the liberal nationalist drama that insistently sought a lasting national tradition to legitimize itself.

Conclusion

In 1864, the historian, journalist, and politician Gregorio Cruzada wrote a sharp critique under a pseudonym of the exhibitions of the National Exhibition of Fine Arts. Reviewing the in-vogue history painting section, he protested about the overuse that artists were giving to certain characters: “So much exploiting the queen’s bones in paintings and scenes made me think,” but he could clearly understand it when he “remembered that today an Isabel is the successor to the throne of the other” (Orbaneja 1865, 14). The change in the art market, with increasing state patronage, had prompted “artists to offer the life of her ancestor to the current queen as a painted memorial” (14) The same thing had happened with “Alfonso the Wise and other Alfonsos.” The subject unfolding was evident: “Years ago he studied geography and now he writes the Partidas, a natural progression if we consider the current debate on Prince Alfonso’s education” (14). Had the author made a retrospective criticism, he would surely have said the same about Maria Cristina’s arts policy and the memory of the medieval queen’s regent Berenguela and Maria de Molina.

Those painted, represented, and even acoustic memorials were integrated into a general process that understood the past as a source of legitimacy. In this way, certain historical characters and passages of the monarchy were used in nation-building. The repetition of these arguments, tropes, and images for so long and in such a wide range of formats provides eloquent testimony to the effectiveness of the discourse. Liberal nationalism thus succeeded in anchoring itself to a long-lasting, glorious national tradition that linked its present with an immemorial fight for freedom, liberty, and independence. The names of the men involved are a veritable pantheon of outstanding liberals: historians such as Modesto Lafuente; writers of the stature of Manuel Bretón de Los Herreros, José Zorrilla, and Benito Pérez-Galdós; painters such as Vicente López and Federico Madrazo; even politicians as diverse as Victor Balaguer, Mariano Roca de Togores, and Pedro Calvo-Asensio. They all belonged to the same nationalist, cultural background and concluded by determining, spreading, and recalling the national narrative of history. Neither did they hesitate to use monarchy in the search for their own legitimacy.

This strategy was also shared by the crown to adapt to the liberal world using the national arguments through its history. Not by chance, Maria Cristina began her cultural policy of arts patronage, in particular history painting, with Berenguela and Maria de Molina, just as she assumed the regency. Nor were the names chosen for the heirs a coincidence, or the journey to Asturias to visit Pelayo’s grave. Equally, Isabel II consented with pleasure to wear the Barcelona county and Isabel the Catholic’s crowns, to be disguised as Queen Esther or a medieval countess, and to perform evocative historicist scenes, as occurred in Granada. Thus, the crown found in history a perfect argument for its legitimacy, where nationalism, provincialism, and romanticism crossed. The nation’s essentialization into medieval history made the monarchy serve as a stage on which to project these liberal nationalist dramas into the mists of time. Likewise, based on the double patriotism (Fradera Reference Fradera2003) that prevailed in territories where provincialist movements were developing, the monarchy managed to introduce the regions into national metaphors. For that purpose, it identified with local traditions, symbols, and rituals that the Catalan, Basque, and Galician provincialism were developing in regions with a protonational tone. It also turned to the region’s history, emphasizing the medieval past and the monarchy’s role in defending ancient freedoms and representative institutions.

From 1833 to 1868, there were competing and complementary discourses within liberalism and the monarchy. But the purpose was often the same: to justify both presences. Resources were numerous and variable: from successful plays and novels to exhaustive historical works, from political and press discourses to public representations. And consequences were notable: the mixing of the monarchy and the nation. Combining them, it managed to confuse them until they could neither be distinguished between nor individually questioned.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia y Universidades, MICIU (Spain) under Grant PGC2018-093698-B-I00, as well as the Universidad Complutense de Madrid – Banco Santander under Grant CT27/16-CT28/16.

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.