Introduction

Research on textbooks has shown how education, and particularly history education, can be a tool for peace and nation-building. Indeed, scholars have largely emphasized how elites use educational policies in these two processes: advancing peaceful and inclusive societies (Pingel Reference Pingel2010, 50) or sowing division and differentiation (Baranovicé Reference Baranovicé2001; Lange Reference Lange2012). History textbooks have been presented as a means for elites to “justify and underpin a nationalist discourse” (Germen-Janmaat Reference Germen-Janmaat2004, 8) or reinforce the claims of a group on a territory (Baranovicé Reference Baranovicé2001, 16). They are also analyzed as “sources of collective memory” (Crawford Reference Crawford2003, 5; Kirmanj Reference Kirmanj2014, 372; Repoussi and Tutiaux-Guillo Reference Repoussi and Tutiaux-Guillon2010, 156) that contribute to creating collective identities by promoting categories of identification. As a socialization tool, education influences the way we see the world and the way we perceive others and ourselves in our societies (Dimou Reference Dimou2009, 162; Korostelina Reference Korostelina2010, 130). It also contributes to delineating the boundaries of the nation.

Despite their central contribution to identity building and nationalism studies, research on textbooks overlooks their reception by the populations for which they have been designed. They tend to present the relation between the narratives contained in the textbooks and the pupils reading the textbooks as top-down and unidirectional without addressing the potential influence of the environment on the reception of these narratives. This article includes the geographical (Brachet Reference Brachet2005; Guimond Reference Guimond2006), demographic (Toft Reference Toft2002), and symbolic (Billig Reference Billig1995; Pinos Reference Pinos2009; Kolstø Reference Kolstø2006) features of a territory and the events that pervade the living context of the community and generate specific dynamics that have an impact on the building of identity. Events, as part of a group environment, usually tend to be disregarded in favor of territorial geographical, demographic, or symbolic features. However, as I show in this analysis, they constitute a central element in the understanding of group identity and in the way the textbooks’ narratives permeate the community.

I focus here on the specific case of Kosovo Serbs who live in Serbian enclavesFootnote 1 in Kosovo. This case is particularly relevant for at least three reasons. First, Kosovo’s educational system segregates students into Serb and Albanian schools, with each community learning a different history, and Serbian pupils there use the same history textbooks as those used by Serbian pupils in Serbia.Footnote 2 Second, contrary to the narratives contained in Serbian official discourses or the media, history textbooks do not present the Serbs in Kosovo as a distinct category. This has contributed to the promotion of Serbs as a unique nation. As stressed by Dubravka Stojanović (Reference Stojanović2007), the Serbian elite use history textbooks to achieve political goals. Nevertheless, and this is the third point, Serbs in Kosovo live in an environment quite distinct from that of the Serbian pupils from Serbia. The enclaved territories are characterized by their concentration of a homogeneous group of people who live isolated from the mainland but still have some relations with it (Bojan Reference Bojan2013; Massey, Hodson, and Sekulic Reference Massey, Hodson and Sekulic1999; Nies Reference Nies2003; Vinokurov Reference Vinokurov2007). These relations materialized through the presence of Serbian parallel administrations (municipalities, schools) but also through access to Serbian media (television and newspapers) in the Serbian enclaves.

The creation of enclaves began before the 1990s, but the process has accelerated since that period until today (Bataković Reference Bataković2008). Within these territories, Serbs in Kosovo have experienced four major events: the Kosovo war in 1999, the March pogroms in 2004, the unilateral declaration of Kosovo independence in 2008, and the dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo under the guidance of the European Union since 2013. In this article, I argue that the interaction between the environment and the textbooks’ narratives contributes to creating a dialogic relation between past and present, which leads Kosovo Serbs to strengthen their religious identity and comprehend the enclaves as ethnoscapes (Smith Reference Smith1999a).

Using an iterative approach based on the UNESCO guide (Pingel Reference Pingel2010), I analyzed the textbooks used by Kosovo Serbs in four Serbian enclaves in Kosovo—Štrpce, Gračanica, Velika Hoča, and the Serbian quarter of Orahovac—and then studied them in interaction with the enclaved environment and the four major events identified above. I relied on secondhand material and participant observation, as well as interviews conducted during fieldwork. I used the chosen trauma framework developed by Volkan (Reference Volkan1997; Reference Volkan2013) as it provides the tools to analyze the current context of living within a historical perspective and highlights how the textbooks’ narratives constitute bridges between past and present.

The developments described below I first present the analytical framework of this article. I then focus on the enclave environment—enclaves’ features and events—and the specific dynamics it engenders. Relying on socio-psychological theories, this discussion helps operationalize the dynamics through which chosen traumas are reactivated. The events have been selected as they emerged as significant from the extensive fieldwork I conducted in December 2016 and between August 2017 and April 2018 within the four enclaves. I then provide an analysis of the history textbooks. I close with a discussion of the interaction between textbooks’ narratives and the four events, showing how they contribute to the emergence of enclaves as ethnoscapes.

Enclaves as Ethnoscapes

A Territorialized Understanding of Ethnoscapes

The concept of ethnoscape appeared for the first time in Anjun Apparudai’s (Reference Apparudai1990) works. Noting the globalized nature of the world, Apparudai understood the concept especially in terms of deterritorialization and movement (Sian Reference Sian2013, 83). He defines ethnoscape as a “landscape of persons who constitute the shifting world in which we live; tourists, immigrants, refugees, exiles, guest workers and other moving groups and persons constitute an essential feature of the world and appear to affect the politics of (and between) nations to a hitherto unprecedented degree” (Apparudai Reference Apparudai1990, 297). His concept was notably used (and still is) to study the reconfiguration of diasporic identities (Zanforlin Reference Zanforlin2016; Vaughan Reference Vaughan2016). Contrary to Apparudai, Anthony Smith proposes a more territorialized understanding of the concept of ethnoscape, which he defines as “sites that possess a special symbolic and mythic meaning … endowed with a sacred and extraordinary quality, generating powerful feelings of reverence and belonging” (Smith Reference Smith1999a, 149–50). Smith explains that ethnoscapes are created throughout three associations made by the inhabitants of a land and contribute to what he calls the “territorialisation of memory” (1999b, 17). These associations consist of viewing the land as a territory where “events and experiences that moulded” and have an impact on the development of the community took place. The territory is also regarded as a “witness to the survival of the ethnie” (Smith Reference Smith1999b, 16–17). These associations instill a “sense of continuity” that links territory and the people through a mutual belongingness. Following Smith, the territorialization of memory also implies a sacralization of the territory that can occur in three different ways: by engendering “a community of believers,” through “holy deeds of heroic ancestors,” and finally as “a result of a quest for liberation and utopia” (1999b, 20).

The Chosen Trauma: The Dialogic Relation between Past and Present

The concept of “chosen trauma” developed by Vamik Volkan in 1997 helps to understand the particular relation a community maintains and/or develops with a territory. Focusing on a psychological perspective, the concept of chosen trauma is defined as “the shared mental representation of an event in large group’s history in which the group suffered catastrophic loss, humiliation, and helplessness at the hands of its enemies” (Volkan Reference Volkan2013, 231). Volkan notes that traumas are more effective than glories for creating and perpetuating group identity (1997, 43). It may seem contradictory to consider a traumatic event a foundation on which the identity of a nation is built. As Daniel Bar-Tal underlines, however, “groups need to have a past as it is an important element in their collective identity showing that there is continuity in their existence and that they have a firm foundation for their uniqueness and solidarity” (2013, 172). This relation between the chosen trauma and the destiny of a nation gives the “community its distinctive character” (Smith 1999b, 17) and is a necessary component of the process of territorializing memory, which contributes to the formation of an ethnoscape. One particularity of the chosen traumas is that they can be reactivated in current contexts as people may perceive certain events as repetitions or manifestations of the past (Ramanathapillai Reference Ramanathapillai2012, 835; Takei Reference Takei1998, 62). These traumatic experiences “provide the key evaluative measure which enables us to assess other events in the group history” (Bar-Tal Reference Bar-Tal2014, 9).

1999 to 2013 in the Kosovo Serbs’ Enclaves: Insights from Socio-psychological Theories

In the discussion below, I first present the four events that emerged as central during my fieldwork and then focus on the specific features of the enclaved environment. I rely on socio-psychological theories in order to show how these events and characteristics influence the building of Kosovo Serb identity in these areas. Socio-psychological theories help us to understand and operationalize the reactivation of the chosen trauma.

1999–2013: Uncertainty as a Way of Life

Four major events have affected the Serbian community in Kosovo since 1999.Footnote 3 The importance of these events emerged during the fieldwork I conducted in December 2016 and between August 2017 and April 2018 in the four Serbian enclaves of Štrpce, Gračanica, Velika Hoča, and the Serbian quarter of Orahovac. All of these Serbian places are located in the Southern part of the Kosovo territory and it must be noted here that, depending on the enclave, the importance of events varies. For example, in Orahovac, Velika Hoča, and Štrpce, the inhabitants emphasized the NATO bombing in 1999, whereas the March 2004 pogroms appeared more relevant in Gračanica. In Orahovac and Velika Hoča, the bombing is described as aggression, whereas it is mostly defined as a war in Gračanica. Also, I do not presume here that these specific events did not have any emotional impact on the Serbian community in Serbia or even within the Serbian diaspora. However, they did not affect the Serbs in Serbia as they did the Serbs in Kosovo.

Studying the discursive construction of identity of Kosovo Serbs in southeastern Kosovo, Sanja Zlatanović (Reference Zlatanović2011) reveals that 1999 emerges as a temporal rupture in the discourses of those she interviewed. There is a “pre-1999 and post-1999, dividing so the time into ‘our’ and ‘their.’ Generally, the 1990’s, when Kosovo was under control of the Belgrade regime, are marked as ‘our time,’ while the period after 1999—as ‘their time’ (that is, Albanian)” (92). She states that the postwar era raised questions within the Serbian community in Kosovo, as people did not know whether they wanted to move or to stay in the territory. These concerns triggered a “feeling of vulnerability” (92). Those who decided to stay gathered in “enclaves” and still live within these territories today. Within these small pieces of land, the Serbian community has had to face, several challenges since 1999 that have impacted their well-being, self-esteem, and security. As Chris van der Borgh (Reference Van der Borgh2012, 37) notes, the riots that took place in 2004 nurtured a sense of insecurity which persists even now, partly because of the ongoing negotiations between Belgrade and Pristina under the guidance of the European Union. These negotiations “induced fear and a sense of insecurity in the Serbian community in Kosovo” (NGO Aktiv Reference Aktiv2016, 6) as they do not allow Kosovo Serbs to project themselves into the future. A report produced in 2015 stresses that one of the most striking issues for Kosovo Serbs—whether they live in the northern or the southern part of Kosovo—remains their physical security (Balkans Policy Research Group 2015, 5).Footnote 4 However, a study conducted by Orli Fridman (Reference Fridman2015) shows the Serbs’ willingness to overcome their fear and accept their new reality (mostly in the south of Kosovo) as it seems to be the only way to live and stay in this new entity. A resident of the Serbian enclave of Gračanica explained in 2009 that they have to participate in the political process to “protect themselves from Pristina’s repression, terror and discrimination” (Jovanovic and Alic Reference Jovanovic and Alic2018)

Enclavement and Marginalization Dynamics

Regardless of whether feelings of repression, discrimination, and insecurity are real or perceived, the perception alone is enough to start a cognitive process. Roger Petersen (Reference Petersen2002, 19) develops a theory of ethnic conflict based on emotion through which he explains that groups who experience status inversions and become a minority may tend to develop resentment as they lose their advantages. Also, the isolation inherent to Serbian enclavement might influence Serbs’ perception of marginalization as they are confronted with the difficulty of geographical isolation, notably due to the few means of transportation connecting them to other Kosovo Serbs cities or to Serbia, particularly in the enclaves situated in the southwestern part of the Kosovo territory. If Serbs decide to cross the border to enter into Serbian territory, they have to face a border control. Kosovo Serbs can also be easily identified by “foreign” and Serbian authorities because of the inscription Koordinaciona uprava (coordination directorate) on their official Serbian passports. Because of this inscription, they cannot benefit from traveling privileges such as those granted to Serbs from Serbia, and instead usually need a visa. These constraints exacerbate the perception of enclavement (Brachet Reference Brachet2005), as well as their psychological distance from Serbia (Oldberg Reference Oldberg2000, 6) and sense of marginalization.

Isolation may also be cultural, referring to a “minority linguistic, cultural, social, economic or political situation” (Guimond Reference Guimond2006, 1). As Claus Offe (Reference Offe1998, 2) notes, living in a minority context creates uncertainty and perception of marginalization by the dominant group. As the literature explains, when confronted with uncertainty, marginalization, discrimination, or what people perceive as being marginalization or discrimination, people lose their self-esteem and seek to mitigate these negative affects by categorizing themselves as members of another group (Turner et al. Reference Turner and A. Hogg1987; Verkuyten and Yildiz Reference Verkuyten and Yildiz2007, 1450; Hogg and Mullin Reference Hogg and Mullin1999, 249–279) that has a stronger internal cohesion. This stronger internal cohesion can notably be found in the religion that forms “an important meaning system for making sense of existence” (Greenberg, Solomon, and Pyszczynski 1997) and thus reduce uncertainty (Hogg Reference Hogg, Hogg and Blaylock2011).

The contributions of social psychology literature are particularly insightful here. It allows us to understand how the context within which Kosovo Serbs have lived since 1999 has led to the emergence of feelings of uncertainty and fear that impact intra- and intergroup processes. In order to analyze the interaction between these psycho-sociological dynamics and the textbooks’ narratives, I present the textbook narratives in the following section.

Serbian History Textbooks from 2008 to Today: Strengthening a Serbian Religious Identity

My research included analysis of eight public school history textbooks from primary schools located in the four Kosovo Serb enclaves of Štrpce, Gračanica, Velika Hoča, and the Serbian quarter of Orahovac, as well as participant observations and interviews conducted in these four Serbian areas during my field work in December 2016 and between August 2017 and April 2018. Below, I briefly explain the fieldwork methodology before presenting the analysis of history textbooks.

Fieldwork Research

In December 2016, I spent two weeks in Kosovo in order to evaluate the accessibility of my fieldwork and make some contacts with the local population. At this time I collected the textbooks.Footnote 5 The informal talks I had at this time led me to revise my research plan to focus on the four Serbian areas as I found that they reflect the various situations within which Serbs live in Kosovo. Štrpce and Gračanica are the biggest enclaves in Kosovo and constitute Serbian majoritarian municipalities. However, while Štrpce is naturally isolated in the mountains, Gračanica is close to Pristina, capital city of Kosovo, which, while Albanian, is also the administrative and cultural center for Kosovo Serbs. As in Gračanica, Serbs who live in the Serbian quarter of Orahovac live close to Kosovo Albanians but constitute a minority within the Albanian municipality of Orahovac, where Serbs from Velika Hoča also originate. In Velika Hoča, however, Serbs are more isolated than in Orahovac because of the contined existence of a protective zone implemented after 1999.Footnote 6

Between August 2017 and April 2018, I spent five months in Orahovac and Velika Hoča and two months in Gračanica and Štrpce. I chose to live with the Serbs in order to experience their living conditions, the challenges they faced, and the internal dynamics that pervade the community.Footnote 7 This also gave me not only privileged access to observations of the symbolic landscape during celebrations and political events, but also more awareness of the tensions that exist within the community and between the two major groups, the Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians.Footnote 8 Twelve interviews were conducted in Orahovac and Velika Hoča—with seven men and five women—which were complemented by many informal talks with locals. Ten interviews were conducted in Gračanica—with nine men and one woman—and seven in Štrpce—with six men and one woman. The ages of the interviewees ranged from mid-20s to 70 years old. The sample included interviews with political, religious, and cultural elites but also the local population. The interviews were semi-structured and focused on various themes: education, religion, politics, employment, and relations with Serbia. They were conducted mostly in English—sometimes with an interpreter, sometimes without—or in Serbian in some cases.Footnote 9 The language limitations on the parts of both the researcher and the interviewees when the interviews were conducted in English without an interpreter must be taken into account, as they affect the results presented in this analysis. Indeed, my language limitations have hindered a deeper contextual study of the textbook material.

Iterative Approach as Methodological Framework

The fieldwork observations and interviews constitute a fundamental part of this analysis as they reveal the perceptions and feelings that arise from the local enclaved population. However, I use them here only as examples of the environmental dynamics that pervade the Serbian enclaved community.Footnote 10 The primary sources were the eight public school history textbooks from two different publishers—Zavod za uzbenike and Logos—that are used from grades five to eight in primary schools located in Štrpce, Gračanica, Velika Hoča, and the Serbian quarter of Orahovac.Footnote 11

Elementary school is composed of a total of eight grades, for children ages 7 to 15. The ninth grade constitutes the first year of secondary school, which includes four additional grades beyond that (and can be vocational), for youth ages 15 to 19. I focused on the four grades of history education in elementary school, grades five through nine (for students 11 to 15), because they constitute a common basis of teaching and learning.

The Zavod textbooks are produced by the Serbian state publishing house, whereas the edition of Logos textbooks is produced by private publishers or nongovernmental organizations. Even though education in the Serbian areas of Kosovo is officially under the control of the Kosovo Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, created in 2002, the Ahtisaari PlanFootnote 12 provides the Serbian municipalities with the ability to cooperate with Serbia, particularly in the field of education (Pierre Reference Pierre2015, 126; Arraiza Reference Arraiza2014, 22; Di Lellio et al. Reference Di Lellio, Fridman, Hercigonja and Hoxha2017, 21). In the Serbian places that are not situated within Serbian municipalities, Kosovo Serbs manage to procure the textbooks (interview by author, Orahovac, December 2016). The selected textbooks were published between 2008 and 2016 and cover a period of time ranging from the prehistoric age to the disintegration of Yugoslavia, and they are built around a table of content that is very similar. Their average number of pages is 185, and they have been written by a variety of authors.

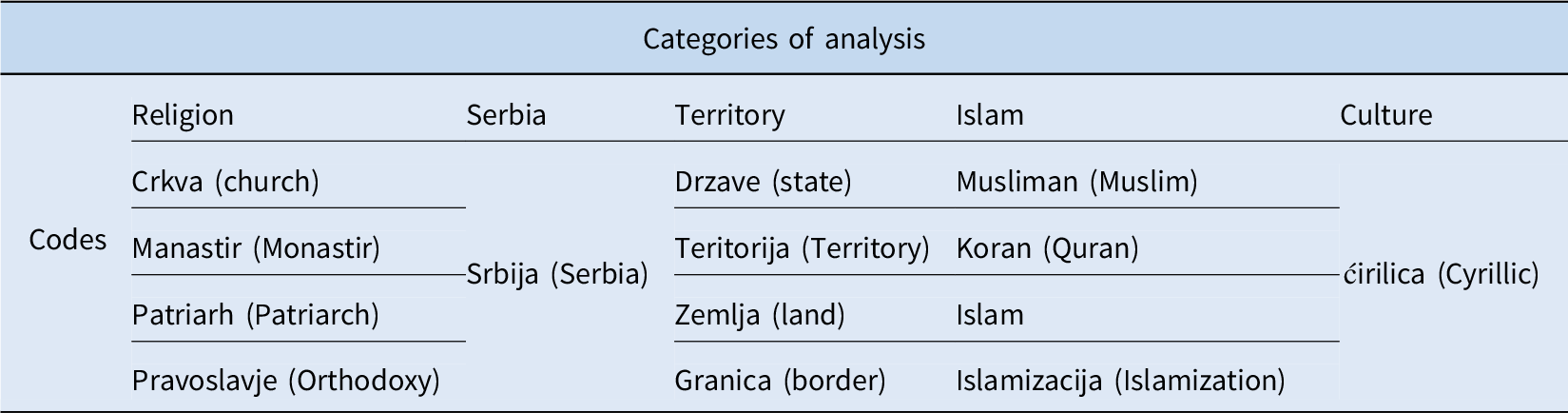

To carry out this study, I used a two-step approach combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Using an iterative approach, I started by personally coding 10 percent of each chapter—representing one to four pages—of the eight textbooks to reveal categories of analysis that I then used to code the entire textbooks. Eight categories emerged (see Table 1)Footnote 13: religion, conflict, Serbia, territory, Islam, culture, historical figures, and “Others.” These categories were chosen because of their repeated appearance in the texts or because they are particularly relevant to the research question. Throughout this phase, some terms were added to the coding process, but others were also removed. For example, within the religion category, I first coded all the terms related to religion together, including those in relation to Christianity and Islam. Because of the particular emphasis on Ottoman Turks—who are Muslim—throughout the textbooks, and also because Albanians—also Muslim—now constitute the majority of the Kosovo territory, I finally decided to create a separate Islam category. I also confined the religion category to Orthodoxy and removed the terms related to Christianity more broadly. The category of culture excludes religion. I wanted to study the importance of language or traditions within the textbooks. It appeared that this category was not so relevant. Serbia is a category by itself, as I only coded the noun Serbia. It was presented so many times that it seemed impossible not to include it. The categories of historical figures and “Others” were very wide as I coded all the historical figures and “Others” I found in the textbooks. I decided to use this strategy as I wanted to reveal who were those emphasized and those (almost) ignored. As a result, larger entities of which Serbia was a part of were coded as “Others.” This choice is consistent with research that seeks to understand the Serbian community, which also means analyzing how relations with other groups within these entities are presented. Lastly, I withdrew the category dedicated to conflict vocabulary, because the analysis was focused on history textbooks and history is mostly composed of conflicts. It thus seemed normal that the vocabulary of conflict composed a large part of each book.Footnote 14 This category, however, was useful during the second part of the study.

Table 1 Categories of analysis except historical figures and “Others”20

Results of the Analysis: Ruptures and Continuities

I then continued with an in-depth analysis of the categories that were revealed during the first phase. I measured their importance by focusing on the frequency of the codes’ occurrence. I also analyzed sentences or paragraphs when codes appeared several times within them or when they were associated several times with vocabularies of violence and conflict. The results highlight ruptures and continuities with the previous Serbian history textbooks.

Notably, the results show a balanced point of view regarding Yugoslavia, as Serbian history is included in chapters dedicated to Yugoslav history in the eighth-grade history textbooks. This contrasts with the narratives presented after the fall of Milošević. At that time, the reforms that took place in 2000 promoted “a strong anti-Yugoslav and anti-communist interpretation of events” (George Reference George2014, 33; Stojanović Reference Stojanović2009, 143), in order to sustain the new reality of Serbia independence (Di Lellio et al. Reference Di Lellio, Fridman, Hercigonja and Hoxha2017, 21–22). The nationalistic focus is, however, maintained as Serbian history (and Yugoslav history) is studied separately from world history. In the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades, Serbian (or Yugoslav) history accounts about 50 percent of the different books, with two exceptions: Zavod grades six and seven, where Serbian content respectively accounts for about 62.5 percent and 39.8 percent of each book. For grade five, Zavod’s textbook devotes one chapter and one sub-chapter to Serbian history, whereas Logos’s textbook refers to Serbia only in some pages and a sub-chapter. An analysis of chapters dealing with Serbian people or Serbian land balanced this last tendency: Logos’s textbooks are the ones focusing mainly on Serbia, and the word appears more often.Footnote 15

Probably linked to this observation, the preliminary analysis reveals that the Logos textbooks also emphasize territory, whereas the Zavod textbooks focus on religion. This finding shows the strengthening of the religious category. (This issue is discussed below.) It has to be noted here that Islam is also more preeminent in the Zavod textbooks than it is in the Logos textbooks and contributes to supporting the preeminence of the religion in the material for these grades.

The Albanians, who were presented as the main enemies in previous history textbooks, are almost absent in the textbooks analyzed here. Indeed, during the Milošević period, Albanians became the main enemy, as history textbooks emphasized “Albanian crimes against Kosovo Serbs” among others (Janjetović Reference Janjetović2002, 247–252). This depiction of Albanians in history textbooks has continued despite the fall of Milošević and the introduction of reforms in 2000. In the present analysis, however, Albanian or Albanian nouns appear 47 times in Logos’s textbooks and 27 times in Zavod’s. The Albanian uprisings that took place from 1830 to 1912 are totally ignored, just as Serbian textbooks are silent, for example, on the lack of Albanians schools in the 18th century (Gashi Reference Gashi2016, 51–65). Albanians are also presented in relation to the crimes they committed against Kosovo Serbs.Footnote 16 Nonetheless, four main “Others” may be identified in the textbooks: the Slavic people, the Ottomans, the Turks, and Yugoslavia. Greece is particularly emphasized in both collections destined for grade five.

The preeminence of Yugoslavia needs to be nuanced. Indeed, the noun Yugoslavia appears 235 times in Logos’s textbooks compared to 159 times in Zavod’s. This result is consistent with the emphasis put on Tito’s figure in the Logos textbooks—Tito appears 51 times in the Logos textbooks but 13 times in the Zavod textbooks. Tamara Pavasović Trošt (Reference Trošt2014) presents the various trends regarding Tito’s representation within the Serbian history textbooks from the socialist era until 2010. She shows that during the socialist period Tito was described in positive terms but was gradually removed from the textbooks during the ethno-nationalist period. She stresses the use of a neutral tone which coincides with the reintroduction of Tito’s figure in the textbooks published between 2001 and 2005. After 2005, Tito is mostly presented through his role on the world stage (152–158).

The victimization and suffering of the Serbian people is also an enduring theme clearly linked to the struggles experienced by Serbs. As is the case for many nations, Serbian history consists largely of successive struggles linked to the delimitation of Serbian borders and these events are reported and presented in history textbooks. In this matter, the succession of wars and battles in Serbian history textbooks may appear understandable. However, this emphasis on conflicts emerged after the disintegration of Yugoslavia that led to a dilution of elements of unity previously created under communist rule (Koulouri Reference Koulouri2002, 25). A more detailed observation also reveals that textbooks include a significant number of images that depict bloody fights. These struggles for territorial control are often associated with the domination and submission of the Serbian nation by and to the victors. This tendency begins with the Arab conquest and is later pursued under the subjects of Bulgarian and Ottoman rule. For example, Serbs during the Arab conquest in 556 CE are presented in Logos’s grade six book as forced to cooperate by the Arabs (61). In the same chapter, the term forced is used again, associated with submission (70) or slavery (72) in relation to the Bulgarian state. The Serbian nation also continues to be depicted as suffering under foreign oppression during World War II, when it faced Croatian massacres of its people. The Battle of Kosovo Polje that took place in 1389 and that was mentioned at the end of the grade six books marks the onset of the period of domination. Gashi notes that “after the end of the rule of King Dušan in 1355, no episode from Serbian rule in Kosovo, which lasted until 1415, is presented other than the Battle of Kosovo in 1389” (2016, 35). The absence of other episodes that took place during this period reveals the central significance of this battle for the Serbian identity.Footnote 17 The Battle of Kosovo Polje is a turning point in Serbian history as it signifies the end of the Serbian Golden Age, but also the beginning of centuries of oppression and submission under Ottoman rule. Even if the Serbian nation has faced other historical defeats on the battlefield and other nations at certain points in time can be identified as significant “Others,” the “Muslim Turks” remain, throughout history, the “Other” group from “which the Serbian identity was defined” (Khan Reference Khan1996, 50).

Strengthening of a Religious Identity

After the Kosovo Polje battle, the Serbian Orthodox Church was the only Serbian institution that existed and through which Serbian identity, language, and culture was maintained. In the textbooks, the religious dimension of Serbian identity develops a perspective that diverges from submission and domination. For example, monasteries are depicted as fortresses, and historical figures who are related to this category do not harbor any notion of sacrifice. In fact, it is quite the contrary, as they highlight the survival—but also the magnificence—of the Serbian nation. In the first place, I note the high volume of the material in the textbooks that is dedicated to religion, particularly in grade six. For this grade, textbooks are almost entirely dedicated to the religious wars that tore southeastern Europe apart during the Middle Ages. The cover of Zavod’s Istorija 6 (Rade Reference Rade2008) is an image of Stefan Nemanja and the cover of Logos’s Istorija 6 (Vekić-Kočić, Kočić, and Lopandić Reference Vekić-Kočić, Kočić and Lopandić2016) depicts the monastery of Gračanica. For the chapters dedicated to Serbian history, the analysis reveals that Nemanja is one of the five most-cited historical figures in the textbooks; the others are Stefan Dušan, King Lazar, Karađorđe, and Tito. Nemanja was canonized by the Serbian Church (Khan Reference Khan1996, 50) and is presented as the founder of the Serbian nation. He was also the father of Sveti Sava (Saint Sava), the creator of the Serbian Orthodox Church (autocephaly). An entire chapter in each Istorija 7, the two grade seven books, is also dedicated to the patriarchate of Peć, a town on Kosovo territory, who was the first patriarchate of the Serbian Orthodox Church (Antić and Bondžić Reference Antić and Bondžić2012, 56–59; Dušan 2009, 61–65). The religious dimension of Serbian identity is thus extremely linked to the territory of Kosovo and highlights two other aspects of Serbian identity: its survival and its magnificence.Footnote 18

Discussion

Orthodoxy and Serbian identity are tightly coupled, according to Darko Tanasković, a philology professor and a religious analyst cited by Natalija Sako (Reference Sako2013), who explains that in the Balkans there is a close interconnection between religion and culture. Orthodoxy does not always refer to a faith but rather is intrinsically linked to the definition of who they are as Serbs. Sako also cites Miroljub Jevtić, a professor of the politics of religion, who argues that religion was the only thing that differentiated people within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Sako Reference Sako2013, 3). When the federation broke down, the nationalities emerged deeply related to the religious ones.

The religious character of the Serbian community is deeply related to the territory of Kosovo, which is regarded as the cradle of the Serbian nation. Orthodox religion is also connected to the idea of survival within the textbooks, which is particularly relevant to the uncertainty that pervades the Serbian community in Kosovo. Later, I address the interaction between the environment in which Kosovo Serbs have lived since 1999 and the narratives promoted through the history textbooks, showing how this interaction has led to the emergence of enclaves as ethnoscapes and also how it has contributed to anchoring a religious identity.

For the Serbs, the loss of the battle of Kosovo Polje constitutes a “chosen trauma.” The history textbooks analyzed in this article emphasize this battle, making it the sole event mentioned for the period between 1355 and 1415 (Gashi Reference Gashi2016, 35). The silencing of other historical events underscores the preeminence of this battle and its centrality in Serbian history. It represents a turning point in Serbian history; and it signals the important relationship between the Serbian community and the Kosovo territory, as Kosovo represents both the worst and the best of Serbian history. This territory is thus intrinsically related to the destiny of the Serbian nation and thus gives the “community its distinctive character” (Smith 1999b, 17), which is a necessary component of the process of territorializing memory, which contributes to the formation of an “ethnoscape.”

Analyzing the Battle of Kosovo Polje as a chosen trauma means that Kosovo Serbs in Kosovo evaluate the current context within which they live in relation to this traumatic event, which is relayed and maintained through textbooks narratives that emphasize centuries of submission and domination. Indeed, the NATO bombing in 1999, the 2004 riots during which several orthodox churches were destroyed or burned, the 2008 unilateral declaration of Kosovo’s independence that definitely enshrined the separation of Kosovo Serbs from their homeland (Serbia) and their minority situation in Kosovo territory, and finally the intensification of negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia since 2013, from which Kosovo Serbs are still excluded (although these negotiations concern them deeply): all of these events contribute to reactivating the trauma of domination presented in the textbooks.

The current context within which Kosovo Serbs live can be understood as a reactivation of a traumatic collective memory, which usually “triggers an unconscious defense mechanism” (Ramanathapillai Reference Ramanathapillai2012, 835). Regarding the connotation of survival that is attached to the Serbian Orthodox Church in the history textbooks used by Serbian pupils in Kosovo, we may think that the environment and the uncertainty attached to it reinforces the Serbian Orthodox Church as the guardian of Serbian identity in Kosovo. During my fieldwork within the four Serbian enclaves in Kosovo, religion appeared to be central. The religious character of the Serbian identity, particularly in Kosovo, was stressed by a resident of an enclaved territory in an interview conducted in December 2016. The existence of churches within every place where Serbs live in Kosovo is the most important element that constitutes the enclaved landscape. Throughout the interviews, they were described as places to meet, to gather as reflections of Kosovo Albanian violence—related to the March pogroms in 2004—or places that give the Serbian community the strength to stay. In Orahovac and Velika Hoča, the Orthodox faith and its practices were key arguments that led the Kosovo Serb Orthodox believers to oppose the perceived Kosovo Albanian nonbelievers. Religious faith and practices thus delineate who is included and excluded within the community.

The connotations of survival but also of magnificence attached to the Serbian Orthodox Church in the textbooks strengthen religion both as a way of reducing uncertainty and recovering self-esteem. For centuries, the Serbian Orthodox Church has asserted itself as the only effective protection of Serbian identity. In times of crisis, when identity benchmarks are blurred, the idea of survival becomes important and religion, as the last fortress, gains a central significance. The favorable way in which religion and the Serbian Orthodox Church are presented in textbooks also allows people to positively categorize themselves. The cognitive processes that reorient the Kosovo Serb identity in terms of religion are strengthened throughout the history textbooks, which validate the role of the Serbian Orthodox Church as the guardian of Serbian identity. The dynamics generated by the environment within which Kosovo Serbs have lived since 1999 echo the content of the history textbooks and particularly the religious dimension of identity they promote. Kosovo Serbs’ current living context is viewed as a continuation of the tragic Serbian destiny, with the enclaves as the last territories within which Serbian communities survive in Kosovo. This therefore contributes to the emergence of ethnoscapes. Here, the understanding of ethnoscapes and the territorialization of memory are deeply linked to the religious dimension of identity. This relation between territory and religion gives a symbolic power to enclaved territories insofar as Kosovo Serbs may define themselves positively through their belonging to these pieces of land.

Conclusion

The analysis presented in this article reveals religion as a central pillar on which Serbian identity is built and this result is sustained through the interviews conducted by the researcher during fieldwork in Kosovo Serb enclaves. Orthodoxy helps to distinguish the self from the others and enables the group to improve its self-esteem. The reminder of the traumatic events in the textbooks allow for the gathering of the Serbian community around the same shared values, but also helps in that they focus on the same “Other.” The emphasis on the religious character of the Serbian identity in the history textbooks analyzed here is consistent with a more general trend we can observe within the Serbian public sphere at large since the 1990s. However, it acquires a specific resonance for Kosovo Serbs.

If the living environment does not totally transform the narratives contained in the textbooks, it certainly reinforces them. However, the relation between the environment and the narratives analyzed in this article has to be balanced with the various contexts within which Kosovo Serbs live in Kosovo. Whether they are located in the northern part of Kosovo or in the south, Kosovo Serbs have experienced events previously stressed quite differently. Regarding the isolation, it is, for example, easier to go to Serbia from Gračanica than from Orahovac, Velika Hoča, or Štrpce, as Gračanica is very close to Pristina, the capital city of Kosovo, and is often presented as the administrative center of the Kosovo entity. These variations are important to note and necessarily balance the results of the present analysis.

It must be considered also that textbooks only constitute one among media available to the government to promote its narratives and that these other channels—television, newspapers, political discourses, and literature—obviously interact with the narratives promoted throughout textbooks. This is particularly important in the case of Kosovo Serbs as, even if they live within the Kosovo territory, they still watch the Serbian news (RTS1; Pink TV, notably) and are thus exposed to other narratives from Serbia. Besides, religious elites or artists appear as actors able to promote narratives alongside the government. The interactions among these various media could strengthen or, on the contrary, soften the influence of history textbook narratives. The teaching of history as well as the children’s prior knowledge of historical events are elements that mediate the reception of history textbooks narratives as well. Children “do not come to the classroom as blank slates. They bring with them the attitudes, values and behaviour of their societies beyond the classroom walls” (Bush and Saltarelli Reference Bush and Saltarelli2000, 3). So do the teachers. In their report published in 2017, Di Lellio et al. show how the personal trajectories of teachers—Serbian and Albanian teachers in Kosovo—influence the events which they decide to emphasize.

Including all these variations, however, goes beyond the scope of its article, which particularly aims to highlight the key significance of the temporal continuity within which the territory and its memory are embedded and highlights the importance of taking into account the environment within which textbooks’ narratives are implemented in order to understand their effective influence on the identity building of a community. This approach could also be applied to other narratives (news media, for example). However, I stress the need to analyze these environmental dynamics in the historical trajectory within which they are embedded. Studying the interaction between the enclaved environment and the narratives within a historical perspective allows us to understand the centrality of Kosovo and Orthodox religion for Kosovo Serbs and how these two elements contribute to distinguishing them from the others.

The significance of Kosovo and Orthodox religion for the Serbian community has often been presented in the literature as an unquestioned reality. This situation has led to overlooking the dynamics that participate in the construction of this reality and the potential impact they have on the building of a community. By addressing some of these dynamics, I hope to bridge that gap.

The emergence of enclaves as an ethnoscape grounded notably in the centrality of religion seems particularly important for understanding the relations between Kosovo Serbs and Kosovo Albanians in Kosovo, as religion appears to be a fundamental element in the process of delineating the boundaries of the Serbian community in Kosovo in relation to both the Kosovo Albanians and the Serbs from Serbia. The emergence of these pieces of lands as ethnoscapes participates in this exclusionary process. As I stress in the introduction to this article, Serbian history textbooks do not present Kosovo Serbs as an autonomous category, but rather as part of the Serbian nation. However, my analysis reveals that their implementation within the enclaved environment contributes to creating or reinforcing the distinction between Serbs from Serbia and Kosovo Serbs.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to the journal’s reviewers for their insightful comments. I also thank Philippe Beauregard and Cecile Robert for their proofreading of earlier drafts and Michael Rossi and the Association for the Study of Nationalities for their useful advice, which helped me to improve the first version of this article.

Disclosures

The author has nothing to disclose.