The famine in Kazakstan during the first half of the 1930s was the most severe of the Soviet regional famines triggered by collectivization.Footnote 1 Approximately one-quarter of the total victims of the Soviet collectivization famines lived in Kazakstan: up to 1.5 million people (Davies and Wheatcroft Reference Davies and Wheatcroft2004, 415). Approximately one-third of the Kazak population died, while one-fifth of Ukrainians perished during the famine. At that time, the Kazaks were officially considered a nomadic population in the USSR, and approximately three-quarters of them practiced mobile pastoralism. Historiography of the famine has focused on the different factors that led to the food crisis in the region (Cameron Reference Cameron2018; Kindler Reference Kindler2018; Ohayon Reference Ohayon2006; Omarbekov Reference Omarbekov1994, Reference Omarbekov1997; Pianciola Reference Pianciola2009, Reference Pianciola2018). Forced state procurements of grain (starting in the winter of 1927–1928) and livestock (especially since the summer of 1930) were the most important factors. A drought in the northern oblasts of Kazakstan during the summer of 1931 contributed to the deepening of the crisis in part of the region (Cameron Reference Cameron2018, 118, 193–194), while the sedentarization campaign was less important, if at all, in unleashing the famine. Given the mass immigration of Slavic peasants during the last decades of the Tsarist Empire, the specificity of Kazakstan was that it was a region that was at the same time a grain-producer (mostly by the Slavic peasants, one-third of the region’s population at the eve of the famine) and a grain-consumer. Grain was also consumed by the Kazak pastoralists, who depended in no small measure on exchanges with the peasants. Grain procurements that targeted both the Slavic peasants and the Kazaks, followed by livestock procurements that primarily targeted the Kazaks, led to a subsistence crisis that found its victims mostly among those who were in a weaker economic and alimentary condition, such as the herdsmen. Existing research is lacking in two respects. First, unlike studies devoted to Soviet policies toward nomads during the 1920s (Thomas Reference Thomas2017), or to Kazak violent resistance during collectivization (Allaniiazov Reference Allaniiazov1999; Allaniiazov and Taukenov Reference Allaniiazov and Taukenov2000; Nabiev Reference Nabiev2010; Pianciola Reference Pianciola2013), regional studies of the famine are virtually absent. Second, comparative studies of the collectivization crisis in nomadic areas other than Kazakstan are also rare. Comparative analyses are needed because, although similar policies of collectivization, grain and livestock procurement, and sedentarization were launched for all the nomadic peoples of the Soviet Union, only the Kazaks were devastated by the famine.

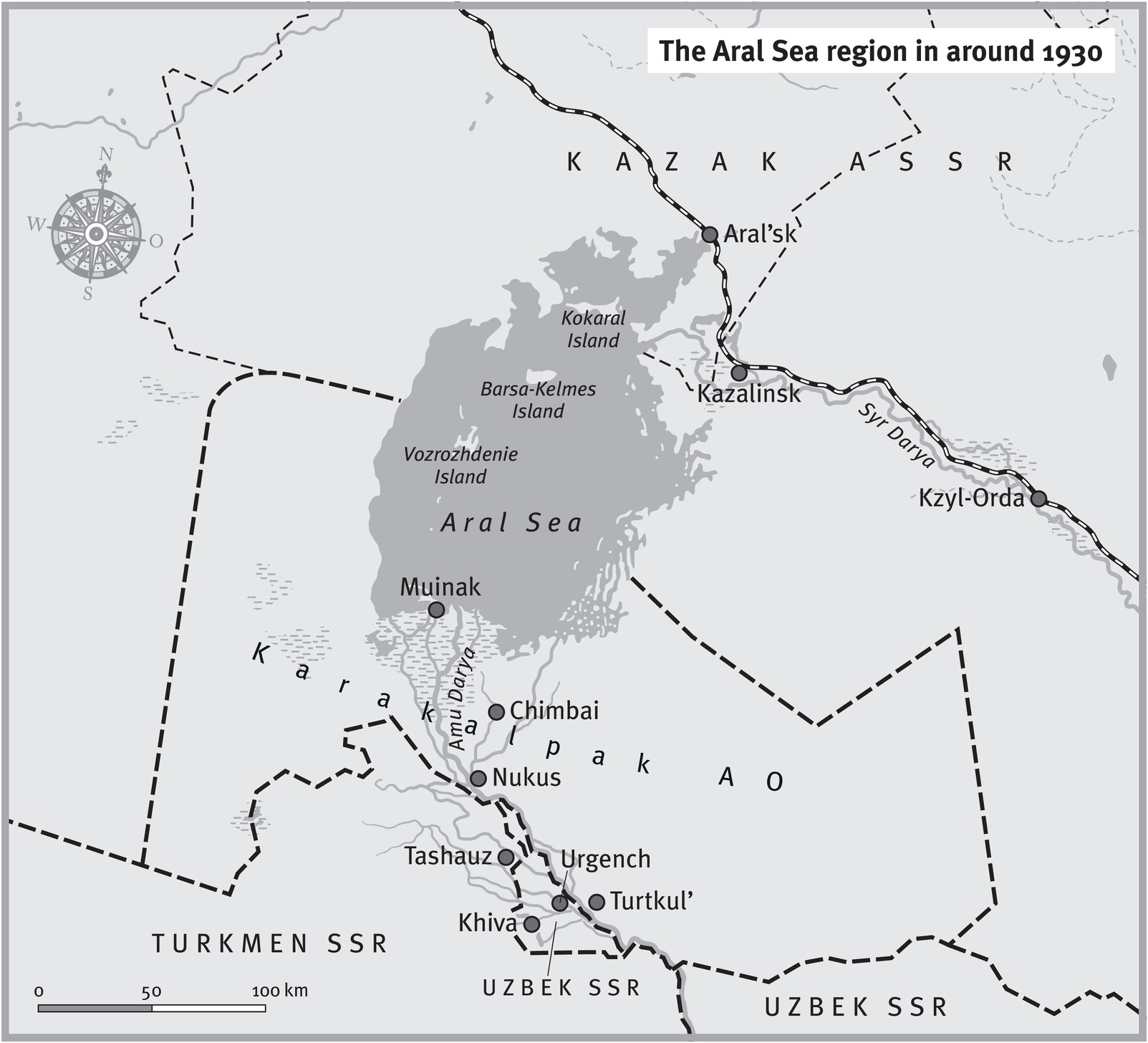

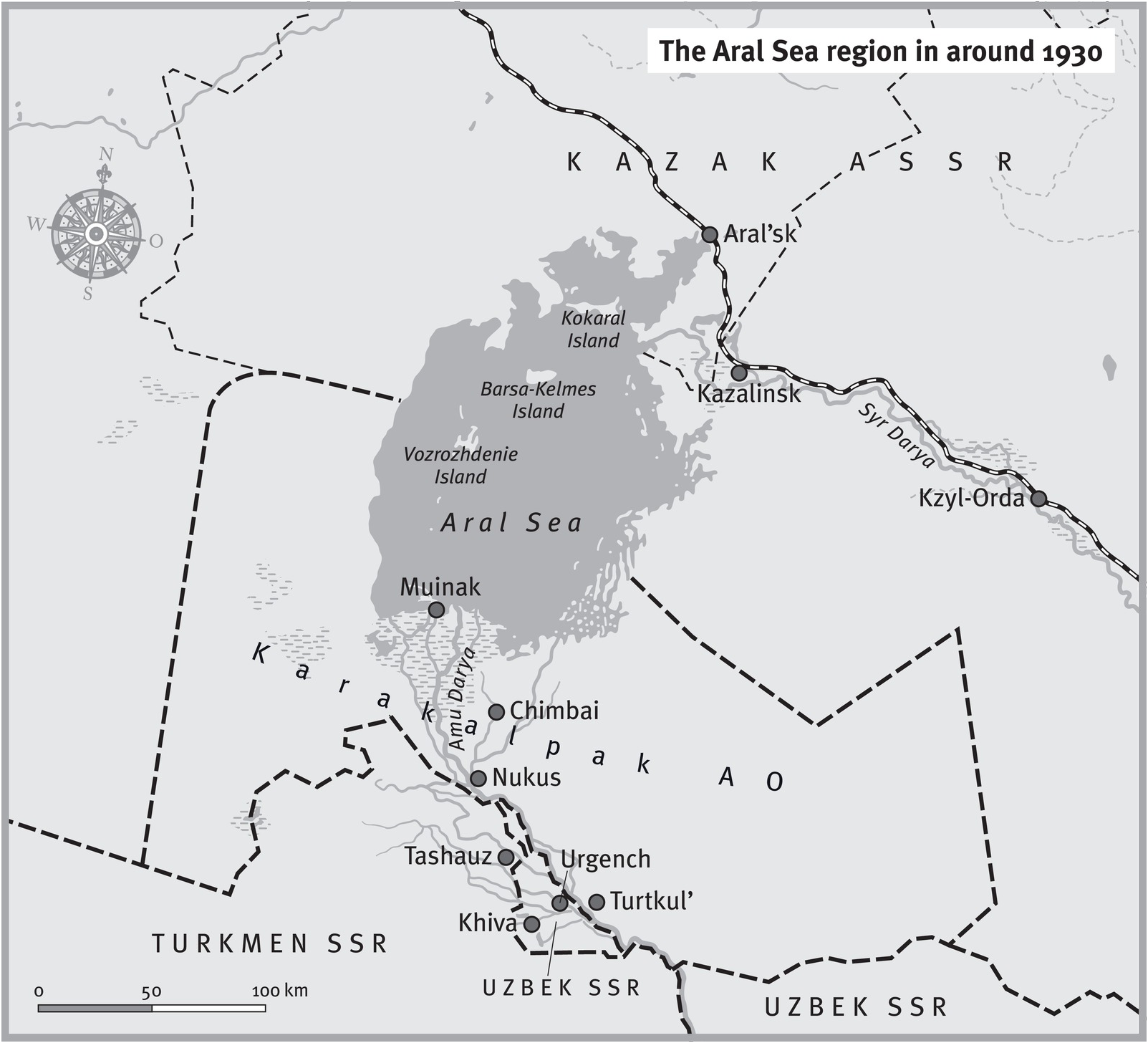

This article is a contribution in both these directions of research: it is an attempt at a regional history during the famine, and, at the same time, it aims to compare how Kazaks and Karakalpaks of the Aral Sea region went through the period of collectivization, famine, and sedentarization (the three events form a causal and temporal sequence). In geographical terms, I focus on the Karakalpak region (present-day Karakalpakstan, a special administrative unit within Uzbekistan), the lower Syr Darya area (Kazalinsk province of Kazakstan), and the Aral’sk province of Kazakstan (see Figure 1).Footnote 2

Figure 1. The Aral Sea region in around 1930. Map by Peter Palm.

These were and still are the most populated areas around the sea. The population was mostly rural, and there was a marked ethnic difference between towns and countryside, with the very few Russians and other Europeans concentrated in the towns. In the Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast’ (AO), in 1926 Russians and other Europeans accounted for only 2.2 percent of the population.Footnote 3 In the Aral’sk districtFootnote 4 of Kazakstan, in 1930 Russians comprised 9.8 percent of the population, mostly concentrated in the town of Aral’sk, which had a population of 3,780 in 1925.Footnote 5 The two main towns of the lower Syr Darya Valley were Kazalinsk (population: 6,623 in 1923) and Kzyl-Orda (8,499 in 1923). The latter was the capital of Kazakstan between 1925 and 1929.Footnote 6

The southern shore of the sea, mostly inhabited by Karakalpaks, was not hit directly by the great famine of 1931–1933. While the Kazak population of the Soviet Union decreased by 22 percent between the two censuses of 1926 and 1939, the Karakalpak population increased by 27 percent.Footnote 7 Unlike the Karakalpaks, the Kazak population living on the eastern and northern shores of the Aral Sea was especially devastated: the rural population in the Aral’sk district of Kazakstan decreased by 75 percent between 1930 and 1933. This regional imbalance requires an explanation, especially since the Karakalpak AO was part of Kazakstan until the summer of 1930, when it was detached from the latter and directly subjected to Moscow, as part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), of which Kazakstan itself was an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR). In March 1932, the Karakalpak AO was promoted to the status of Autonomous SSR, a higher position within the Soviet administrative hierarchy of ethnonational pseudo-statehood. Eventually, the Karakalpak ASSR was transferred from the RSFSR to the Uzbek SSR in 1936.

As this article shows, the administrative territorial reorganization in 1930 was, in fact, functional for the needs of the command economy. Significantly, the decisions of detaching the Karakalpak region from Kazakstan, and of forcing Soviet livestock and meat procurements from Kazakstan to make up for the plunge in livestock numbers brought about by collectivization everywhere in the Soviet Union, were taken during the same Politburo meeting in mid-July 1930. It is most likely that the shift was decided because of the absence of efficient transportation connections between the southern Aral Sea and Russia, at the precise moment when Moscow launched a campaign of extreme procurements of the steppe’s livestock. The Orenburg-Tashkent railway, completed in 1906, crossed the Aral Sea region in the north (a station on the railway was located in the newly built port of Aral’sk). The railway was the foremost Tsarist imperial infrastructure in Central Asia, and it was instrumental in the funneling of livestock and grains out of Kazakstan during collectivization. At the same time, Soviet planners were pushing for an increase in cotton production in Central Asia, including in the Karakalpak AO, which had to be more strictly linked via railway to Uzbekistan. Thus, transportation infrastructure was an important factor in the series of political decisions that led to the eventual detachment of the Karakalpaks from Kazakstan, and to their incorporation within Uzbekistan.

In addition, this article investigates the economic consequences of the famine for the Aral Sea’s economy. The main consequence of the famine in the region was the inversion of the economic significance of the northern and the southern parts of the sea. Before the crisis, the northern part of the sea was by far the most important in terms of fishing activity; the crisis, which was much harsher in the north, reversed this balance. I argue that this was also largely due to the connection of the northern (Kazak) shore to the center of the Soviet state via the railway. In the context of the ruthless extraction of resources from the Steppe between the summer of 1930 and summer of 1932, and their transportation to central Russia by train, the difference in the transport infrastructure between the Kazak and the Karakalpak “halves” of the Aral region was the key factor in how the famine unfolded.

The difference in the policies implemented toward Kazaks and Karakalpaks was mirrored by the different official scientific discourses used to characterize the two peoples. The discursive construction of the Kazaks as backward nomads in need of a rapid socialist modernization to be brought about by sedentarization was instrumental in justifying callous policies of livestock and grain procurements. Despite the fact that the Karakalpaks also practiced a mobile “multiresource” economy, contemporary Soviet analyses of Karakalpak society and economy were more nuanced. This, I argue, was in part a consequence of their economic marginality, by virtue of their isolated location in the economic geography of the Soviet Union.

The Southern Region and the Karakalpaks

The region around the Aral Sea was not evenly populated: the population was concentrated in the northeastern, eastern, and southern shores. This was due in part to the orography of the shores themselves: shores were low in the northern, eastern, and southern part of the sea, whereas high cliffs from the Ustyurt plateau lined the sea in the west. Most importantly, the eastern and southern areas of the sea had the highest fertility, since these areas contained the mouths of the two biggest rivers in Central Asia, the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya. Of the two, the Amu Darya carried by far the most water, 59.30 cubic kilometers per year according to estimates at the beginning of the 1930s, while the Syr Darya only carried 15.05 cubic kilometers.Footnote 8 In early modern times, until the beginning of the 18th century, the Karakalpaks inhabited the entire lower course of the Syr Darya, from the area around the town of Turkestan to the delta (Tolstov, Zhdanko, Kamalov, Kosbergenov, and Tolstova 1964, 134–141). During the upheavals brought about by the Junghar invasion in the 1720s and 1730s, the Kazak Junior Horde moved westward, invading the territory inhabited by the Karakalpaks. During the 1740s, the latter group migrated south, to the delta of the Amu Darya, under nominal Khivan sovereignty, with a small part moving to the Ferghana Valley, under the khanate of Kokand (S. Jacquesson Reference Jacquesson2002, 57–58). Groups of Karakalpaks remained in the Syr Darya delta for a few more decades. Most moved south at the beginning of the 19th century, while smaller groups lived in other regions on Bukharan and Kokandi territory, and north of the Caspian Sea (Tolstova Reference Tolstova1963, 15–71). Before the Karakalpaks’ arrival, agricultural communities dominated by Uzbek military chiefs inhabited the delta together with Turkmen herdsmen and peasants. As Ulfatbek Abdurasulov (Reference Abdurasulov2016) has shown, the delta region was de facto independent from Khivan domination until the beginning of the 19th century, when Muhammad Rahim Khan (r. 1806–1825), of the newly established Qunghrat dynasty, subdued the region south of the Aral Sea. Rahim Khan was able to bring the region under permanent Khivan control by forcibly resettling part of the Karakalpak population, as well as groups of Uzbeks, into lands that had recently become suitable for cultivation in the Amu Darya delta due to an abrupt shift in the river course. The Qunghrat khan forced the resettled Karakalpaks to increase their agricultural output in order to pay taxes to his treasury (Abdurasulov Reference Abdurasulov2016). Before the resettlement, the Karakalpaks practiced a multi-resource economy (Glavnoe Upravlenie Zemleustroistva i Zemledeliia, Pereselencheskoe Upravlenie 1915, 144–50, 190–202; Salzman Reference Salzman, Irons and Dyson-Hudson1972). They undertook irrigated agriculture, livestock breeding, and fishing, as had the previous inhabitants of the lower courses of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya for thousands of years before them (Kamalov Reference Kamalov1968, 25; Tolstov Reference Tolstov1962, 136–204). Karakalpaks were usually described as “semi-nomadic.” Their agro-pastoral economy was functional to the exploitation of a very mutable environment, constantly reshaped by the Amu Darya. The river was extremely unpredictable because its water levels varied sharply depending on the seasonal melting of the Pamir and Tian Shan glaciers. The river carried abundant deposits of silt and sand downstream (1–1.5 kg per cubic meter of water) that often congested irrigation systems and reshaped the delta hydrology (Teichmann Reference Teichmann, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2018, 100–103). The deltaic dwellers adapted to the unpredictability and ever-changing course of the terminal Amu Darya distributary channels: as Davletjarov and Günther (Reference Davletjarov, Günther, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2013, 59) put it, “it was the water that moved the people.”

Junior Horde Kazaks remained in the occupied Syr Darya delta region long after the Junghar threat had faded. In 1873, after the Tsarist conquest of Central Asia and the defeat of the Khivan khanate, the eastern bank of the Amu Darya came under Tsarist direct control. The same year, the new situation was sanctioned by an agreement between the Khivan khanate—by then a Russian protectorate—and St. Petersburg (Abdurasulov and Sartori Reference Abdurasulov and Sartori2016). Groups of Ural Cossacks were exiled in the region shortly afterward, during the 1870s (Kalbanova Reference Kalbanova2002). From 1873 to the collapse of the Tsarist Empire, the Karakalpak population was divided between the Amu Darya otdel’ in Turkestan, on the eastern bank of the river, and the Khanate of Khiva on the western bank. After the Bolshevik military conquest of Khiva in 1920, the khanate-protectorate became the Khorezm People’s Republic. In 1924, under the framework of the “national delimitation” of Central Asia and the creation of the ethnically designated Soviet administrative units, the Soviet government created a Karakalpak Autonomous Oblast’ (AO) that united the population on the two banks of the lower Amu Darya, except for the district around Khiva. Historian Arne Haugen (Reference Haugen2003) has suggested that the creation of the Karakalpak administrative unit resulted from the decision of Khorezmian administrators to implement an internal ethnonational administrative division in 1923, as a defensive measure against Moscow’s plan to dismantle their Republic. That year, a “Kazak-Karakalpak oblast’” was created within the Khorezm People’s Republic. This did not prevent the latter’s undoing, but created an ethnonational territorial unit and made it possible for Karakalpak communists to take part in the decision-making process of delimitation. Allaiar Dosnazarov, the Karakalpak member of the Commission for the national delimitation of Central Asia, vocally defended the Karakalpak right to “their own” administrative unit (Haugen Reference Haugen2003, 172–179). The oblast’ that was eventually created had an area of 206,353 sq. km, greater than Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan combined. The Kyzyl Kum sand desert covered 43 percent of the oblast’s territory.Footnote 9 According to the 1926 census, of the 146,317 Karakalpaks living in the Soviet Union, 116,125 were concentrated in the Karakalpak AO, and approximately 10,000 inhabited other regions of Uzbekistan (mostly the Ferghana Valley). Only 1,305 lived in Khorezm, the historic center of the Khivan khanate just south of the Amu Darya delta (Tolstova Reference Tolstova1963, 11).

The Karakalpak AO was initially included within the Kazak Autonomous SSR (itself part of the RSFSR), and not within the Uzbek SSR, which incorporated the Khorezm oasis, including the former capital of Khiva. During the delimitation process, both Uzbek and Kazak communist leaders claimed that the Karakalpaks were most closely related culturally to their own respective nations, and that they therefore should be included in their republic (Khalid Reference Khalid2015, 274). The region’s ethnic composition was not the motivation for the final decision in favor of Kazakstan. The Uzbeks, who were about 30 percent of the population in 1921, were more numerous than the Kazaks (about 22 percent) in the Karakalpak AO, while Karakalpaks made up 39 percent of the total population.Footnote 10 It is possible that the linguistic affinity between the Karakalpak and Kazak languages helped in tipping the consensus in favor of the Kazaks. One scholar who played an important role in early Soviet cultural policies regarding Central Asia, linguist Aleksandr Samoilovich (at the time rector of the Leningrad Institute of Oriental Studies), classified Karakalpak as a Kazak dialect (Bustanov Reference Bustanov2015, 1–35; F. Jacquesson Reference Jacquesson2002, 94). Most likely, as suggested by Karakalpak historian Askar Dzhumashev (Reference Dzhumashev and Bugai2006, 133–139), the crucial factor was that administrators both in Moscow and locally believed that the most important economic resource of the region, the Aral Sea fisheries, needed to be managed as an economic unit, without creating different administrative organizations for the north and the south of the sea. This issue was hotly debated a few years later, as we will see. As the historiography on the 1924 “state-national delimitation” has shown, the only criteria that could counter the main “ethnographic paradigm” in border-making were economic expediency and, to a lesser degree, administrative efficiency (Gorshenina Reference Gorshenina2012, 214–238; Haugen Reference Haugen2003, 180–210; Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005, 62–64, 160–165). Shortly before, in December 1923, a newly created Aral Sea Fishing Inspectorate located in Kazakstan (in the town of Aral’sk) had been tasked with the regulation of fishing activities in the entire sea and in the deltaic areas of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya. As a matter of fact, in the mid-1920s the inspectorate was unable to exercise effective control over the southern fisheries in the Karakalpak AO, where instead provincial (uezd) administrations used the fisheries as an informal fiscal resource (Berg Reference Berg1926, 8–9, 149–151). Nonetheless, the political choice was made in favor of a unitary management. A similar dynamic was at play with the Khorezm irrigation network. Its administrative partition between the newly created Uzbek SSR, Turkmen SSR, and the Karakalpak AO allowed control of irrigation to pass to the Administrations for Water Management within the People’s Commissariats of Agriculture of each new republic. This splitting was counterbalanced, on paper, by the coordination provided by the Central Asian Water Administration in Tashkent, under the direct supervision of the party’s Central Asian Bureau (Obertreis Reference Obertreis2017, 157; Teichmann Reference Teichmann, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2013, 80). As for the fisheries, the “hydrological delimitation” de facto entrenched and magnified water conflicts during the 1920s (Teichmann Reference Teichmann, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2018, 104). Thus, even if the Karakalpak AO fisheries were formally under the control and supervision of Kazakstan, and its irrigation network under the control of Tashkent, in reality the local administration enjoyed a substantial autonomy in economic matters during the 1920s (Teichmann Reference Teichmann, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2013, 82–83). This peculiar Karakalpak administrative bifurcation was mirrored by the region’s split dependence under the party and state administrative pyramids. The Karakalpak AO Communist Party structure was under Tashkent’s Central Asian Bureau, while its Soviet (state) bureaucracy was part of Kazakstan. However, in July 1930, after the first wave of total collectivization, the Karakalpak AO was administratively detached from Kazakstan and incorporated directly into the RSFSR in the state administrative pyramid. At the same time, the Party organization of the Karakalpak AO remained under the Central Asian Bureau. In Central Asia, only the Kyrgyz ASSR was in the same unusual administrative situation.

Connectivity

No study has convincingly explained why the Karakalpak AO was separated from Kazakstan in 1930 and assigned to Uzbekistan six years later (Ubiria Reference Ubiria2016, 124). Once the Karakalpaks were recognized as a separate nationality in the original delimitation of 1924, their further collocation within the Soviet administrative structure became detached from any consideration of cultural or linguistic affinity to contiguous nations. In other words, the ethnographic factor faded, and economic and administrative expediency became paramount. We know that tensions between Kazak and Karakalpak Communist administrators were present during the 1920s, but we have no evidence that they were significant enough to play a role in the territorial detachment.Footnote 11 The economic factor seems more relevant, as suggested also by the timing of the decision. Stalinist industrialization and collectivization led to a reorganization of Soviet economic regionalization (Pianciola Reference Pianciola2017). The Central Asian economic region, administered by the Communist Party Central Asian bureau in Tashkent, was tasked with expanding cotton cultivation and provision for Soviet industry (Teichmann Reference Teichmann, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2016). During the 1930s, Kazakstan, administered by the Communist Party of Kazakstan in Alma-Ata, was instead treated as a reserve of livestock and meat to feed the main Soviet industrial and political centers (Pianciola Reference Pianciola2018). In terms of economic specialization, before World War I and the revolution, cotton cultivation expanded in the region, making the Karakalpak AO a potentially coherent part of the cotton-producing Central Asian economic region. In the mid-1920s, 17 percent of the sown area of the region was cultivated with cotton (Teichmann Reference Teichmann, Dzhumashev, Günther and Loy2013, 83). However, cotton was not the decisive factor per se, as cotton cultivation was also present in the lower Syr Darya Valley in Kazakstan. In other words, the economic specialization of the Karakalpak AO was not dissimilar to Kazakstan’s Aral Sea region districts: livestock breeding, cotton, and fisheries. It is likely, instead, that the decisive factor was the Karakalpaks’ economic marginality, and the projected connectivity of their area within the Soviet space.

For both Alma-Ata and Moscow, the Karakalpak AO featured only marginally in state procurements plans. The Karakalpak AO provided a tiny fraction of the grain collected by state organizations in Kazakstan. During the first forced procurement campaign after the end of the New Economic Policy in the 1928–1929 economic year, the Karakalpak AO was supposed to turn in 100,000 puds (1,638 tons) of grain to the state, out of 70 million puds (1.15 million tons) for the entirety of Kazakstan. It was by far the least productive administrative region of Kazakstan (the second to last was supposed to produce 20 times more grain than the Karakalpak AO in 1928–1929).Footnote 12 The region was also relatively marginal in terms of livestock breeding; approximately 5 percent of Kazakstan’s total livestock lived in the Karakalpak oblast’. Most importantly, a 1928 report described Karakalpak livestock breeding as totally “outside the sphere of market influence” (as in, the Karakalpaks did not exchange livestock products for grain), their economy functioned as a “natural economy,” and livestock breeding for them “essentially has an auxiliary character in connection to agriculture; or, when it is self-sustained, it is only used for consumption [by the herdsmen themselves].”Footnote 13 Even if we cannot take this analysis at face value, its conclusions were very different from contemporary studies of Kazak livestock breeding, which was often described as deeply integrated, through barter and monetized market exchanges, with the agricultural sector (Pianciola Reference Pianciola2009, 214–218).

No railways existed in the region. Its then–main administrative center, Turtkul’, was 400 km from the closest railway station on the Orenburg-Tashkent railway. The closest town on the same railway, Kazalinsk, was 700 km away, linked to the region only by caravan routes. The same distance separated Turtkul’ from Aral’sk, which could be reached via boat by descending the Amu Darya and then crossing the Aral Sea (but not between November and mid-April, when the sea was frozen). Inside the Karakalpak AO, connections with the lower administrative centers were granted during the summer by navigation on the Amu Darya and on the biggest canal of the region, named the Kegeili. During winter (when state livestock procurements were mostly carried out), only caravans connected the different areas of the lower Amu Darya region; no cars or trucks were available in the region at the beginning of the 1930s. Mail service between the region’s two main towns, Turtkul’ and Chimbai, took 10–12 days, on camels. Motorboats were also lacking. The main freight transports were still large boats (able to carry 3.3 to 24.6 tons) moved by oars or sails following the river flow, or pulled by oxen against the flow (with the flow they were able to cover 50–80 km per day, against the flow around 25). The changing course of the Amu Darya distributary channels in the delta region, where large sandbanks could form over a matter of months, made navigation unpredictable and difficult.Footnote 14 No matter how unreliable the big river was, it connected the Karakalpak AO with central Uzbekistan, not with Kazakstan. Moreover, the Soviet government was planning the construction of a 400-km-long railway following the Amu Darya from Urgench in the Khorezm oasis to Chardzhui, a town in Turkmenistan that was already connected with Tashkent by railway. The planned railway was conceived as a way to make the transportation of cotton from Khorezm and Karakalpak AO to central Uzbekistan much easier. Still in 1930, this railway was planned to be the largest investment in Uzbekistan’s transportation infrastructure during the First Five-Year Plan (Gosplan Reference Gosplan1930, 351). Eventually, though, the priority shifted toward shorter railways in the Ferghana Valley, the central district of Soviet cotton production, which were completed before 1933. The railway between Chardzhui and Karakalpakstan was ultimately only built after World War II.Footnote 15

The timing of the decision to detach the Karakalpak AO from Kazakstan is meaningful: the Politburo decreed it on July 15, 1930.Footnote 16 During the same Politburo session, in which the Kazakstan Party Secretary Goloshchekin took part, the Stalinist leadership decided to turn Kazakstan into an emergency reserve for livestock and meat extraction, sharply separating its functionality for the Soviet economy from the Central Asian economic region—at least until the crisis situation of Soviet agriculture and food provisioning was to have receded. It is likely that the marginality of the Karakalpak region for the livestock and grain procurement campaigns, its partial cotton specialization, and the existing and projected connectivity that linked it with Uzbekistan were the factors that led the Kremlin to detach the Karakalpak AO from Kazakstan. Therefore, its relative well-being during the famine can mostly be explained by the remoteness of the region from the communication lines connecting it to Moscow and the Russian industrial centers that were the main recipients of livestock procurements during collectivization.

Collectivizing Herdsmen and Fishermen

The Aral Sea region in its entirety, not just the Karakalpak AO, was a marginal area of food production for the Soviet economy. The region was especially marginal in terms of grain production. Before collectivization, the Syr Darya guberniia Footnote 17 (the uezds of Kazalinsk and Kzyl-Orda) was a grain net consumer region within Kazakstan. The grain deficit was higher in the areas close to the Aral Sea. In the last quarter of the 19th century, the Kazalinsk uezd imported grain from Khiva every year, and from the uezds of Turkestan, Tashkent, and Khujand (Dingel’shtedt Reference Dingel’shtedt1893, 332). The 1925 harvest data show that the entire Syr Darya guberniia imported a quantity of grain equal to 74.6 percent of its annual production.Footnote 18 1925 was a particularly bad year, since the guberniia was hit by a drought in its southeastern part,Footnote 19 but even in normal years the total production did not provide surplus for export. Grain procurement data for 1928–1929 show that only 2.5 million puds (40,950 tons) out of a total of 70 million puds for Kazakstan were collected in the lower Syr Darya Valley. Kzyl-Orda okrug was third from last in terms of grain procurement in Kazakstan.Footnote 20 In terms of livestock breeding, the region was relatively more significant for the Soviet economy. Data for the mid-1930s show that 20 percent of Kazakstan’s livestock was raised in the Aktiubinsk and South Kazakstan oblasts, which bordered the sea.Footnote 21 However, livestock tended to be less concentrated in districts immediately bordering the Aral Sea (its very arid northern and western shores) and the swamps and lakes in the Syr Darya delta. The region’s fishing sector was significant for Central Asia, but marginal within the Soviet Union. Out of a total annual Soviet plan of 2.1 million tons of fish in 1931, less than 2 percent was caught in the Aral Sea.Footnote 22

This fragile food production base started to be hit by the upheavals brought about by the total collectivization campaign in 1930 and 1931. The total collectivization of agriculture started in 1930, but most of the peasantry of the region was still outside of the collective farms when the famine hit. In the Aral’sk district, after the first total collectivization wave, during the summer of 1930 only 12.4 percent of the rural population worked in the newly formed collective farms.Footnote 23 The 1929–1930 forced procurements campaign that mutated into the campaign of total collectivization caused widespread uprisings in both the Karakalpak and Kazak regions around the Aral Sea. Violent resistance to Soviet policies united the southern and northern shores of the sea. In autumn 1929, revolts broke out in the northern Karakalpak AO. Armed uprisings that targeted local representatives of Soviet power swept through different regions of Kazakstan during the late winter and spring of 1930. The Red Army and the troops of the political police promptly crushed them, massacring thousands of rebels. In September 1930, a massive rebellion of more than 1,000 Kazaks broke out in the Kazalinsk district and was bloodily repressed by the Red Army (Allaniiazov Reference Allaniiazov1999; Kindler Reference Kindler2018, 125–129).

As everywhere in the Soviet Union, collectivization in the region brought about the forced resettlement of the population to larger production units that allowed increased state control over both the rural population and its produce. In the Aral Sea region, this was accomplished by forcefully moving 1,000 households (more than 4,000 people) of fishermen from the Syr Darya delta lakes to the Aral Sea shores, where fish production could be more easily transferred to the railway network.Footnote 24 In September 1929, approximately 3,500 Cossacks had already been moved from the Karakalpak AO in the south of the Aral Sea closer to Aral’sk in the north, where two collective farms were created.Footnote 25 Peasants were deported from Russia as kulaks and forced to become fishermen. In February 1930, the Kazakstan Party committee was planning to settle 3,000 households of deported peasants along the shores of the sea and on its islands.Footnote 26 During the same year, approximately 1,000 fishermen were transferred on a voluntary basis from the Azov and Black Seas (these were the main areas for the emigration of fishermen to the Aral Sea before 1914) in order to be employed in fishing in the deepest areas of the sea, between its western shore and Vozrozhdenie Island.Footnote 27 This migration was part of a government plan for the resettlement of fishermen to the less populated eastern and northern regions of the Soviet Union (especially the Murmansk area, Kamchatka, Sakhalin, and the Far East Pacific coast—but also, to a lesser extent, Kazakstan). For 1931 and 1932, the government planned to resettle a total of 68,500 fishermen (including their family members) in the Soviet Union. Of these, 2,000–2,500 (500 households) had to be moved from the Ural River, therefore from within Kazakstan’s borders, to the Aral Sea; the same number had to move from the Ural River to Lake Balkhash in southeastern Kazakstan.Footnote 28 The newly formed collective farms of the Aral’sk district continued the multiresource economy of the seashore villages, made up of both herdsmen and fishermen. The state imposed a rule of division of labor on the households. The plan for the recruitment of labor from collective farms “for the needs of the fishing industry” at the beginning of 1930 required that one member of each family, and where possible two, should be employed in fishing every year.Footnote 29 In 1931, in the entire Aral Sea region, 8,970 fishermen were counted, of whom 2,800 were Karakalpak.Footnote 30

The fishing sector was at the center of bitter territorial disputes between Kazak and Karakalpak administrators in mid-1930, after Moscow decreed the separation of the Karakalpak AO from Kazakstan. In July 1930, the Politburo left it to the Committee on Nationalities Affairs of the RSFSR’s Central Executive Committee to decide whether the detachment of the Karakalpak AO from Kazakstan would also entail a change in the existing administrative borders. The Committee decreed five days later that the Karakalpak AO should be detached from Kazakstan without modifying the existing borders.Footnote 31 However, both Kazak and Karakalpak representatives in the Central Executive Committee’s Presidium protested the decision. The Kazaks were the most vocal, and at the end of July the Kazak representatives requested the creation of a commission charged with the drawing of the border.Footnote 32 The commission was created in October under the presidency of Pëtr Smidovich, and included representatives from both Kazakstan and the Karakalpak AO.Footnote 33 The main issue at stake was that Kazakstan wanted to detach the entire Aral Sea shore, plus the Tamdy district, from the Karakalpak AO. According to a report by Koptileu Nurmukhamedov, the president of the Karakalpak Executive Committee and the Karakalpak representative in the borders commission, Tamdy district enticed Kazakstan’s administrators because it was a center of Karakul sheep-breeding. Just in case the Central Executive Committee rejected their requested border changes, the Kazaks were planning to move 10,400 Karakul sheep deep into Kazakstan from a Karakalpak sheep-breeding state farm of the district, at the risk of killing many of them during their transfer across the Karakum desert. This large-scale administrative sheep robbery was prevented by Moscow, after vigorous protests from the Karakalpak side.Footnote 34 Eventually, the Karakalpaks successfully argued with Moscow that the district was much more connected with the main centers in the Karakalpak AO than with the distant towns and transport lines of Kazakstan.

The main argument put forward by Kazak administrators for keeping the Aral Sea’s southern shore inside Kazakstan was that its separation would have meant the splitting up of the institutions overseeing the Aral Sea fishing industry, thereby causing disruptions in the exploitation of this important economic resource. As we have seen, this argument had been crucial in including the Karakalpak AO within Kazakstan in 1924. Now it was revived as a rationale for its partition. Kazak administrators were also claiming that the southern Aral Sea shore was underutilized (these predictions proved true, given the increase in fishing output from the Karakalpak shore in the following two decades). To this, Nurmukhamedov and the other Karakalpak administrators replied that the Kazaks had deliberately marginalized Karakalpak fishermen in the distribution of resources over the previous years. The system of credits put in place in the second half of the 1920s was mainly concentrated in the Aral’sk region, in the north, and, therefore, the underperformance of the Karakalpak fishing industry was a direct consequence of Kazak mismanagement and discrimination. Moreover, they argued that the Kazaks had not even been able to develop fishing on the seashore of the Aktiubinsk region in the north, which was completely depopulated.

Karakalpak administrators also put forth the ethnic composition argument in their attempt at keeping the area; Nurmukhamedov underscored the preponderance of Karakalpaks both among fishermen and in the population of the seashore district. In 1930, among the fishermen registered in collective farms on the Karakalpak shore of the Aral Sea, 51 percent were Karakalpak, 30 percent Kazak, 18 percent Russian, and 1 percent Ural Cossacks (most of the Cossacks had already been deported to the northern shore by this point). Fishermen on the Karakalpak shore of the Aral Sea were concentrated in the Karauziak district, the population of which was 67 percent Karakalpak, 26 percent Kazak, 5 percent Russian, and 2 percent of other nationalities. Fishermen and their families were approximately one-quarter of the total population of 41,065. Kazak administrators requested the dissolution of the district, the carving out of the seashore, and its annexation to Kazakstan.Footnote 35 Eventually, Moscow sided with the Karakalpaks and vetoed the district’s dissolution.

Sedentarization

Fishing was one economic sector in which former nomads had to be settled according to the total sedentarization plans for the Kazak population. The first plan was drafted in 1929: in the Aral’sk district, 2,000 Kazak households had to be turned into fishermen during 1930 and 1931. Another 2,000 households were to be settled on the Caspian Sea shore (Mangistau district), with 1,000 on Lake Balkhash and the remaining 1,000 on lakes and rivers of the Alma-Ata and Semipalatinsk regions.Footnote 36 However, this sedentarization drive existed only on paper, and it was only in February 1931 that the Aral’sk district administration started to select the “sedentarization points” where households had to be concentrated.Footnote 37 In late summer 1931, this is how the Fishermen’s Union in Aral’sk replied to a request from Alma-Ata to report on the progress of house construction under the framework of sedentarization:

Your request regarding the construction of residential houses for the fishermen of our district in the process of being sedentarized is extremely surprising. How is it possible to ask for similar reports given the frequency (four times) of changes in the construction plan, and given that you did not send for the construction a single plank of wood or other construction materials, such as nails, iron, glass, etc.? You also did not send a single kopeck of credit, nor the instruments (needed as air is needed to humans) to direct the technical part of the construction works (you promised to send them already in April)…. No construction has been carried out so far in the chosen sedentarization points for the fishermen.Footnote 38

Sedentarization was then disrupted by the outbreak of the famine, which depopulated the region. The most interesting aspect in relation to sedentarization in the region is the markedly different official Soviet discourse about sedentarization among the Karakalpaks and among the Kazaks, as shown by the reports of the Karakalpak interdisciplinary expedition of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. The expedition members, who did fieldwork among the Karakalpaks during 1932, described the Karakalpaks as having been mostly sedentarized already before the revolution. Researchers reported that between 1868 and 1917 in the Chimbai district (one of the areas where their fieldwork took place), the nomadic population decreased from 92 percent to 4.5 percent. In the whole Amu Darya delta region, nomads went from 77.1 percent of the population to 10.8 percent in the same period, while the number of households working in agriculture more than doubled between 1875 and 1896. The cultivated area expanded by 22.7 percent, while the composition of Karakalpak livestock also changed. Between 1893 and 1912, cattle increased from 16 percent to 30.8 percent, while sheep and goats decreased from 69.1 percent to 50 percent (camels and horses completed the region’s livestock).Footnote 39 Researchers of the Academy of Sciences linked these transformations to the expansion of the cotton economy. The authors of the report concluded: “By 1912, the sedentarization of the Karakalpaks was basically completed.”Footnote 40

This was in contradiction to contemporary administrative estimates of the number of nomadic and seminomadic Karakalpak households, which were put at 15,500 on the eve of total collectivization.Footnote 41 In 1932, the Karakalpaks were 37.7 percent of the Karakalpak AO’s total population, so approximately 150,000 (150,800 if we trust Gosplan’s estimate, which put the total population at 400,100 in the same year).Footnote 42 Therefore, in the hypothesis that the average number of persons per household was between 4 and 4.5, the percentage of nomadic and seminomadic Karakalpaks should have been between 41 percent and 46 percent of their total population.Footnote 43 The members of the expedition of the Academy of Sciences studying pastoral practices pointed out that they actually observed nomadic movements (kochevki) among the Karakalpaks, but these were mere “survivals,” connected to survivals of the “tribal social organization.”Footnote 44 Among the Kazaks, official estimates of the late 1920s claimed that approximately 70 percent were nomadic and semi-nomadic. Among the Kazaks living close to the Aral Sea in the Syr Darya delta region, this percentage was already lower before the crisis of the pastoral economy brought about by World War I and the Civil War. In 1890, of the more than 100,000 Kazaks counted as living in the Kazalinsk uezd, 51 percent practiced only irrigated agriculture, while 43 percent were pastoral nomads (the same percentage of the Karakalpaks in the early 1930s; Dingel’shtedt Reference Dingel’shtedt1893, 326).Footnote 45

The Karakalpaks, a much smaller population than the Kazaks, inhabited a far smaller area with less environmental diversity. Their economy and mobility patterns were adapted to the great deltas and lower courses of the rivers of the Aral Sea basin. If compared with the Kazaks of the open steppes, or to the Kazaks and Kyrgyz grazing their herds on alpine pastures, among the Karakalpaks the practice of agriculture was more widespread, and they were more at the mercy of a rapidly changing environment. However, the Karakalpaks’ multiresource economy was largely similar to that of the Kazaks inhabiting the lower course of the Syr Darya and the Syr Darya delta. The Kazaks in the Syr Darya region had been building irrigation canals from the river since at least the late 18th century (Dingel’shtedt Reference Dingel’shtedt1893, 444–463), and agriculture was well-developed among them, with a part of their communities staying in winter quarters all year long (Pianciola Reference Pianciola2009, 205–227; Sokolovskii Reference Sokolovskii1926). Fishing was also an auxiliary economic activity among the Aral Sea Kazaks, as it was for the Karakalpaks. Kazaks and Karakalpaks of the Aral Sea basin were subjected to different procurement policies, and their administrative territories were reorganized on the basis of the presence or absence of transport infrastructure linking their regions with the center of the Soviet state. Moscow’s priorities subjected all the Kazaks indiscriminately to policies of harsh procurements, including those Kazak communities whose economic activities were similar to those of the Karakalpaks.

The Great Famine in the Aral Sea Region

In 1930, increased livestock and meat requisitions in Kazakstan were added to the forced procurements that had been carried out since 1928, and which were hitting the pastoralists particularly hard. These factors led to the most severe regional famine in Soviet history. As in Kazakstan in general, the 1930–1931 procurement campaign in the Aral’sk district dealt a great blow to livestock breeding. Of a total of 170,148 heads of livestock at the beginning of 1931, 78,298 (46 percent) had been requisitioned by the end of May (the annual plan was already 95 percent fulfilled). The requisitions of cattle and small livestock were especially harsh: 15,881 (78.3 percent) heads of cattle out of 20,289 were requisitioned, along with 62,417 (61.2 percent) sheep and goats out of a total of 101,999.Footnote 46 These percentages are higher than those for Kazakstan as a whole over the same period, and this may relate to the fact that the district was close to the railway used to transport meat and livestock to Russia.

The livestock population was wiped out first by state procurement, then by famine. A telling document from 1933 gives an indication of the situation at the end of the process. M. Nikolaev, secretary of the Aral’sk district Party committee, replied to the Aktiubinsk oblast’ Party committee that livestock procurement quotas for the year were completely unrealistic:

In addition to my letter concerning the situation with livestock, I submit to you for the second time the request of freeing Aral’sk district from meat procurement. Try to finally understand (poimite zhe nakonets) that we have 2,165 households that can be taxed, of those 878 edinolichniki and 1,287 kolkhozniki. On the basis of preliminary calculations, we should take from them 60 tons of live weight [of livestock]. However, in the district we only have 451 heads of cattle and 54 heads of small livestock that could be used for meat procurement. From this it is evident that should we have to complete meat procurement, we would need to give literally all the livestock that is left. The district lacks other kinds of animals that could be used to fulfill the meat procurement quota. Rabbit and chicken breeding are not developed at all. I ask a realistic response.Footnote 47

Nikolaev also made clear that between 1930 and 1933 the population in the countryside of the district had decreased by approximately 75 percent, and that only 59.4 percent of the households were in collective farms.Footnote 48

In areas with relatively low grain production output, such as the Syr Darya oblast’, the system of state rationing and food distribution was particularly important. In livestock-rearing regions of Kazakstan, grain and other goods were supposed to be purchased by the population with the money received from the selling of the region’s produce. However, the provision of goods was a complete catastrophe: useless goods were sent to the localities, while grain was not delivered in sufficient quantities.Footnote 49 Given the situation with the food supply, the fishermen were forced to abandon their work and their tools and to move southwards in search of food. As a result, in 1932, the Aral Sea could fulfill only 68 percent of the fish procurements plan.Footnote 50 The population of entire collective farms left their villages. The exodus began in 1930 (the district population in 1931 was 6.7 percent lower than in 1930),Footnote 51 and intensified in 1931 and 1932. Data from two kolkhozes, Bugun’ and Karachalan, show that between early January and late October 1931, approximately 1,000 people left the two collective farms, about one-third of the total.Footnote 52 Local administrative organs registered partial data about collective farmers who had fled. A list names 210 fishermen with their families who had abandoned seven villages in the Kazakstan area of the sea by August 1932. Most of them (all but 13 heads of household) were Kazaks. Many fled, taking one horse or one camel from the collective farm (they could therefore have been indicted on the basis of the law of August 7, 1932, against the theft of “socialist property”). During spring and summer, some even fled on the collective farms’ barges, probably following the Syr Darya eastward, or trying to reach the Karakalpak region, crossing the sea “to buy grain on the market,” as one report remarked.Footnote 53 During the famine, the Karakalpak region became first an area of refuge for Kazak famine refugees, then a transit hub for their return from Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to Kazakstan.Footnote 54

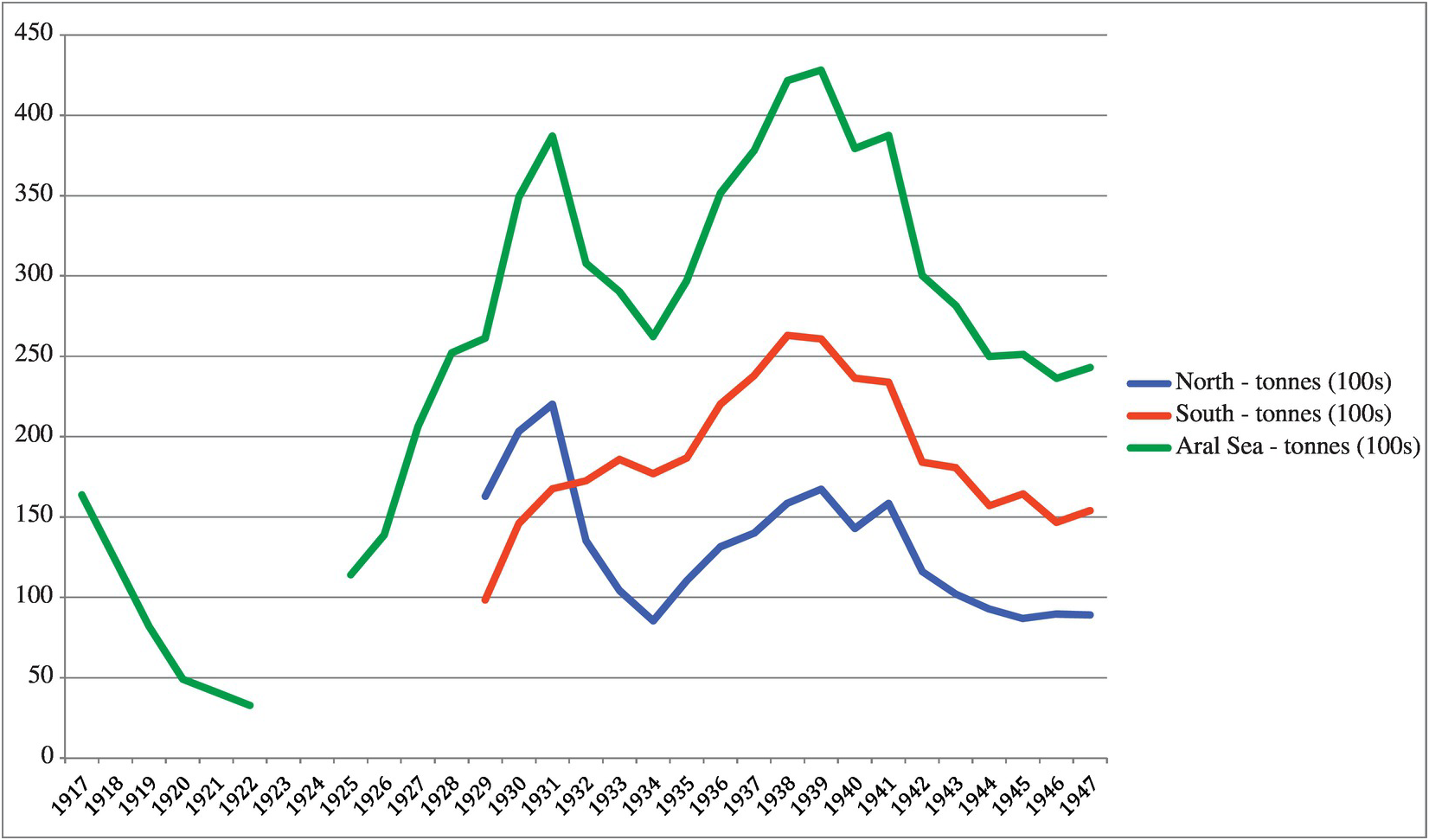

For the fishing industry, the main long-term consequence of the great famine was the shift of the major productive area of the sea from the north to the south. Figure 2 shows the quantity of fish annually caught in the sea, divided into the northern and southern parts. These data should not be taken at face value, since this records only the amount of the catch that the state could monitor (fish consumed locally, either by the fishermen themselves or marketed in the region, probably escaped official counting). However, the data are significant as indicators of both the general trend, and for the relative importance of the northern and southern “halves” of the sea. A strong decline in overall production from 1932 to 1934 is apparent; the decline was concentrated in the northern region, which experienced a serious collapse (1934 marked a 61.2 percent decrease from 1931). Things did not change after the famine: the South remained the most productive area during the following decades, until the Aral Sea eventually dried up.

Figure 2. Fish Catches in the Aral Sea, 1917–1947. Sources: GARF, R5446/81/1515/40, Spravka o sostoianii rybolovstva, vosproizvodstva promyslovykh ryb v yuzhnoi chasti Aral’skogo moria i meropriatiakh pomelioratsii del’ty Amu-Dar’i - Nachalnik Glavrybproma pri Sovete Ministrov UzSSR, F. Erozidi; Nachalnik Aralrybvoda, A. Zharkovskij; Starshii Nauchnyi Sotrudnik Aral’skoj Stantsii VNIRO, M. Fortunatov [no date, but 1947–1949]; GARF, A406/8/360/13, Tsentrsoyuz, rybnyi otdel – Zam. Narkomtorga RSFSR tov. Chukhrite, 02.10.1928; GARF, A259/9b/325/17, Spravka k zased. Ekoso RSFSR o meropriyatiyakh dlia vosstanovleniia rybnoi promyshlennosti v Aral’skom more, 14.02.1925; APRK, 141/1/3747, Operativnyi otchet “Aralso” za pervoe polugode1931 g.

Conclusion

The construction of the Orenburg-Tashkent railway in 1906 had a huge impact on the economic geography of the Aral Sea region. The latter’s connection with the markets and European urban centers of the Tsarist Empire made possible the immigration of fishermen from European Russia and Ukraine, the growth of fishing in the northern half of the sea, and an increase in the economic significance of the Aral Sea for the Tsarist economy. This connection also had the consequence of making the Aral Sea area more susceptible to economic crises, and more affected by political decisions made at the center of the Empire. In the lower Aral Sea basin, connectivity and risk were not evenly distributed: they were concentrated much more in the northern (Kazak) half of the sea than in the southern (Karakalpak) half. State extraction of resources from the area during the crises caused by World War I and the Stalinist Great Turn led to regional famines, unevenly distributed in the region also depending on the closeness to communication routes. The Orenburg-Tashkent railway was the only railway connecting Central Asia to Central Russia until early 1931, when the Turksib (the newly constructed railway connecting Alma-Ata to Siberia) became fully operational. During the early 1930s, the Aral region was marginal in terms of livestock and meat production, but very important as a communication route between Central Asia and the center of the Soviet state. Moreover, it was a region where fishing, and not grain or meat production, was the main economic activity. This sector of the economy was one into which the government planned to distribute former Kazak nomads during the total sedentarization campaign, along with peasants deported from Russia.

Focusing on the Aral Sea region, the article highlights four main points. First, demographic and economic upheavals caused by the Stalinist Great Turn led to a long-term shift, in terms of economic weight, from the northern (Kazak) region of the sea to the southern (Karakalpak) region. Second, the reorganization of production and a stable redistribution of the population were achieved only after the famine, since the measures taken during the first waves of the collectivization were detrimental to the fishing industry. Third, the study of the Aral region, divided between Kazakstan and Karakalpakstan, shows the difference between policies followed in Kazakstan and policies followed in other regions of Central Asia, where mobile pastoralism was the main sector of the economy, and how Soviet official discourse mirrored this difference. The fact that studies of the Karakalpak economy and way of life during early Stalinism were more nuanced than those regarding the Kazaks was arguably more a consequence of the different place they occupied in the Stalinist economic geography and procurement plans than a conclusion derived from a comparative assessment of the Karakalpaks’ and Kazaks’ multiresource economic activities. Finally, the administrative detachment of the Karakalpaks from Kazakstan in 1930 was most likely driven by economic considerations, and by the reorganization of the economic geography of the Soviet Union during the deep crisis brought about by the total collectivization of agriculture.

Acknowledgments.

I would like to thank Ulfat Abdurasulov, Beatrice Penati, and William Wheeler for insightful comments to earlier versions of the article; and Maureen Buja and Andrew Straw for editing assistance.

Financial Support.

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council under the General Research Fund, project number 341612.

Disclosure.

Author has nothing to disclose.

Archives

- AFGAKOO

Aral’sk Branch of the State Archive of the Kyzylorda Oblast’ (Aral’sk, Kazakhstan)

- APRK

Archive of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Almaty, Kazakhstan)

- ARAN

Archive of the Ruesian Academy of Sciences (Moscow, Russia)

- ARAN SP

Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg Branch (Saint Petersburg, Russia)

- GAKhK

State Archive of the Khabarovsk Krai (Khabarovsk, Russia)

- GAKOO

State Archive of the Kyzylorda Oblast’ (Kyzylorda, Kazakhstan)

- GARF

State Archive of the Russian Federation (Moscow, Russia)

- RGASPI

Russian State Archive of Social and Political History (Moscow, Russia)

- TsGARK

Central State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Almaty, Kazakhstan)