There is, for now, enough room in the world for everyone. It is a matter of dividing up the available space in an amicable way. Discoveries, modern inventions and the progress of mechanisation have revolutionised social life with respect to what it was only a few years ago. Everyone pursues the accumulation of wealth in order to gain the greatest possible amount of well-being but, just as in an individual person's life, so also in the life of nations, real well-being comes from the prosperity of all, not that obtained at the expense of others, because in the long term that leads to conflicts that destroy every benefit.

Francesco De Pinedo 1927, 194; our translationFootnote 1

Introduction

Francesco De Pinedo's (1890–1933) record-breaking long-distance flights to Australia and Japan in 1925 and the Americas in 1927 (see De Pinedo Reference De Pinedo1927, Reference De Pinedo1928a, Reference De Pinedo1928b) made important contributions to the promotion of fascist modernity in Italy. Mussolini lauded him as an exemplary modern Italian citizen, he was celebrated in the Italian and international media as the ‘Lord of Distances’, and his exploits were related in readers for Italian school children (e.g. Cappelli Bajocco Reference Cappelli Bajocco1930). De Pinedo's flight to Australia and Japan differs from the Americas flight in that the latter was explicitly motivated by the propaganda aims of the Fascist regime. The enduring powerful association of Italian aviation with Fascism possibly explains why the earlier trip has received little scholarly attention, within Italy or elsewhere – particularly when compared to the 1927 feat.

Figure 1. Article on De Pinedo in Punch (Melbourne) 25 June 1925

In this essay we examine De Pinedo's personal account of the return flight to Asia in 1925 (published in 1927) and the reception of that achievement in Australia at the time. We explore De Pinedo's observations of an emerging Australian modernity and its implications for his own view of the desirable development of a modern citizen. The model fascist Italian that Mussolini saw in De Pinedo contrasts with the man represented in De Pinedo's diary. In pursuing our subject we place on the record an example of an emerging modern, liberal, transnational citizen consistent with the widely held view at the time that aviation might bring the disparate peoples of the world together and facilitate a new, peaceful, technologically enabled form of cosmopolitan life. This version of the new Italian has more in common with attempts to claim the progress towards modernity in Italy as an achievement inspired by liberal values associated with the Renaissance, and the centrality of the dignity and liberty of the individual to Italian understandings of civilisation, than it does with Fascist appropriations of the technology (Forlenza and Thomassen Reference Forlenza and Thomassen2016; Carter Reference Carter2011). De Pinedo's example suggests that there are alternative visions of Italian modernity in the 1920s, which are stimulated rather than confined by transnational encounters made possible by new technologies of travel (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2002).

The Australian response to the Italian's achievement demonstrates the challenges abroad for the Italian diaspora. The tightening of North American immigration policies after the Great War greatly reduced Italian migration there and resulted in a significant increase in the numbers coming to Australia (Macdonald and Macdonald Reference MacDonald and MacDonald1969). Debates about the effects of Italian migration to Australia, particularly in relation to the North Queensland sugar industry, resulted in changes to immigration policy and a Royal Commission into ‘the social and economic effect of increase in number of aliens in North Queensland’ which released its report while the Italian aviator was in Australia. Australia's reception of De Pinedo is inflected by these contemporary debates in which Italian Australians sought to convince an anxious, white, and British Australia of the benefits of more cosmopolitan versions of modernity.

The aviator as fascist exemplar or liberal internationalist

In the period between the wars mastery of aviation technology was widely promoted as a sign of the progress of the nation (see Fritzsche Reference Fritzsche1992, Reference Fritzsche1993; Palmer Reference Palmer1995). Italy's modernity was spectacularly figured through its flying displays and Mussolini's Fascist Government specifically claimed them as a sign that it was returning Italy to a preeminent position amongst the modern nations of the world, a position not seen since the glory days of Imperial Rome (Wohl Reference Wohl2005; Caprotti Reference Caprotti2008, Reference Caprotti2011; Esposito Reference Esposito2012). In reaching beyond the boundaries of the nation – especially through Italo Balbo's transatlantic formation flights in the 1930s – the Fascists sought to reclaim emigrants as enthusiastic admirers and supporters of Fascist achievement (Finchelstein Reference Finchelstein2010; Carter Reference Carter2019). The flights in the decade preceding the Second World War were made possible by Francesco De Pinedo's achievements in the 1920s.

Federico Finchelstein, in his study of transatlantic fascism between 1919 and 1945, characterises De Pinedo as a fascist exemplar on the basis of his role in these pioneering transnational exhibition flights (2010, 91). De Pinedo's 1927 ‘four continents’ flight from Europe through North Africa and across the Atlantic to the Americas was part of a specific strategy to counter anti-fascist protests and stimulate transnational allegiance amongst the Italian diaspora. The Argentinian leg of this journey, for example, was applauded by Mussolini as ‘an affirmation of the vitality of our Latin race’ and as opening a ‘new and grandiose path between Italy and Argentina’ (93). Though racially motivated, those sentiments were conventional in the sense that they reproduced the claims that long-distance British flyers made about their own achievements in bringing the margins of the British Empire closer to the imperial centre (Taylor Reference Taylor1935; Mackersey Reference Mackersey1998).

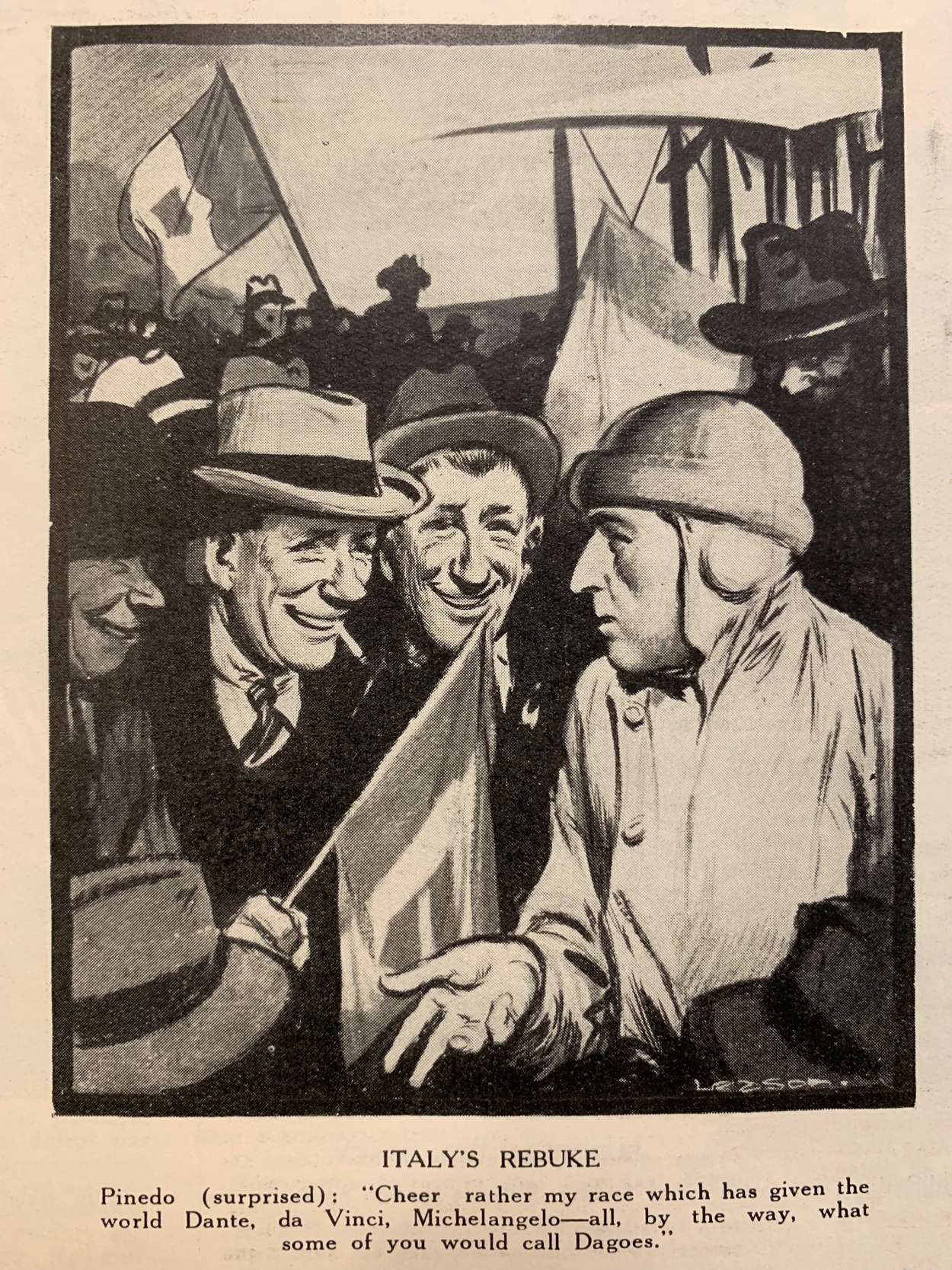

Figure 2. Cartoon by Percy Leason in Punch (Melbourne) 18 June 1925

Aviation was central to the Fascist credo and its reimagining of Italian identity. The aviation historian Robert Wohl (Reference Wohl2005) describes how Mussolini grasped the opportunity provided by public enthusiasm for the spectacle of aviation. Flying allowed pilots to command space with technology and daring, and made them exemplars of the qualities required for modern life and the governance of a nation of admiring, modern citizens. Mussolini's determination to make Italians an air-minded people did not simply reflect concern to develop military prowess; it was a project to affirm the ideal Italian as disciplined, purposeful, energetic, and daring. On gaining power in October 1922 he established a central commissariat of aviation, dramatically increased the budget for new aircraft, aviators and infrastructure, and began to support and promote Italian achievements in aviation design, manufacture, and display (Mussolini Reference Mussolini1928, 291).

In 1925, however, when De Pinedo planned and carried out his great flight to Australia and Japan, the glory days of fascist Italian aviation belonged to the future. While Mussolini supported De Pinedo's initiative, a shortage of funds led the aviator to offer a personal surety for the aircraft in order to secure an official clearance (Ferrante Reference Ferrante2005). There is no doubt, however, that Mussolini approved the flight because he saw it as an opportunity to promote fascism. The socialists were critical of an earlier (1920) flight from Rome to Tokyo which saw ten of the 11 aircraft involved fail in the endeavour, and decried such expeditions as dangerous, expensive, and covertly militaristic (Ludovico Reference Ludovico1970). Mussolini was keen to make a point of difference between his fascists and the socialists and liberals with respect to support for Italian aviation and the new, vigorous, and youthful Italian it was meant to bring into being (Dogliani Reference Dogliani2000). Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi (1997), in her study of fascist spectacle, claims that Mussolini was intent on establishing a new order of citizen soldiers ‘aimed at remodeling the Italians’ style, their way of living, attitudes, habits, and character’ (89) and she refers, in support of this view, to Mussolini's closing address to the 1925 Fascist Congress. That speech, given while De Pinedo was in Australia, lauds the aviator as an exemplary ‘new Italian':

Today fascism is a party, a militia, a corporation. That is not enough. It must become … a way of life. … Only by creating a way of life – that is, a way of living – will we be able to make our mark on the pages of history and not just the daily newspapers. And what is this way of life? Courage, above all, intrepidity, love of risk, repugnance for pacifism and peacemongering, readiness to dare, in our individual lives as in our collective life, and abhorrence of all that is sedentary; in relationships, the greatest of candour, meetings for discussion rather than clandestine, anonymous, petty gossiping; pride in being Italians at every moment of the day; discipline at work, respect for authority. The new Italian: I can already see an exemplar, it is De Pinedo. (Mussolini Reference Mussolini1926, 106; our translation)

Joe Jackson (Reference Jackson2012) takes a different view to Finchelstein by wryly presenting the Italian aviator as a rather reluctant fascist fellow traveller. He suggests that De Pinedo's modest, technical, professional approach to aviation marked a contrast with the heroic adventurous images proffered by the British, French, and American aviators of the period. This reserve defied British stereotypes of the Italian type and won him admirers in Australia, though fascist propagandists such as Balbo put it to more grandiose uses: ‘De Pinedo does not talk, De Pinedo does not write, De Pinedo flies’ (quoted in Finchelstein Reference Finchelstein2010, 92).

De Pinedo appears to be motivated by a desire – perhaps a little before its time – to show that modern aviation technology could domesticate flying as a more quotidian event within modern life (Jackson Reference Jackson2012, 177–178; Courtwright Reference Courtwright2005, 132–150). He wanted to prove that flying boats were the fastest and most reliable means of transnational travel, and he planned his 1925 route to show that they could operate in a range of climates and geographies between the 40-degree latitudes. In choosing Japan as a destination he was taking advantage of the co-operation and some of the logistics put in place for the Italian group flight which had drawn the ire of the socialists. That earlier larger scale venture was the initiative of the Japanese Renaissance scholar, and later fascist propagandist, Shimoi Harukichi, who sought to use it to interest the avant-garde poet Gabriele D'Annunzio in a visit to his native country (Adamson Reference Adamson1993). The book that De Pinedo published based upon his 1925 personal diary, however, avoids the masculine bravado and Futurist hyperbole which his friend D'Annunzio bequeathed to the fascist imagination (see Adamson Reference Adamson1993, 13–22; Wohl Reference Wohl2005, 52–60).

The American literary historian Laurence Goldstein (Reference Goldstein1986, 207) argues that the wider discourses of aviation in the twentieth century are marked by a tension between technocratic reason, which is interested in engineering and logistics, and a less disciplined form of the imagination which offers the transcendent ideals and affective experiences associated with an imagined community (Anderson Reference Anderson1991). Goldstein describes two distinct if sometimes coincident subjects in relation to these dispositions: one is the rational subject of action who is concerned with the mastery of a technology; the other a subject of imagination and feeling who communicates inspirational affect, philosophical reflection, and a disturbing grand narrative of manifest destiny. The fascist seeks to conjoin the two by claiming a prosperous, adventurous, and distinguished place within modernity, which manages nonetheless to preserve the order, reason, authority, and hence stability of the old world (Ben-Ghiat Reference Ben-Ghiat2001; see also Pesman Cooper 1993b, 351). De Pinedo's 1925 journal represents a departure because it is characterised by a more modest sense of restraint, which comes from a more considered awareness of limitations, rather than the speculative daring and grand sense of transgression which distinguishes the narcissistic glories of fascist propaganda.

De Pinedo appears in the journal not as Mussolini's fascist exemplar but as a more liberal version of a modern, transnational citizen who might have little difficulty conversing on like terms with those described in recent research into transnational and indeed Pacific networks of British, Australian and US intellectuals between the wars (see Anderson Reference Anderson2015). De Pinedo was an aviator and not an intellectual or a policy maker, but his presence in Australia in the 1920s provided the occasion for some symptomatic commentary on the modern condition of Italians and their co-habitation with Australians. The Italian aviator makes no reference in his journal to fascist daring or the glorious affects associated with flight, but he is inevitably drawn to comment on the mix of gender, race, and class which he considers appropriate for the development of a modern, multi-racial nation in what he calls ‘the new world’.

De Pinedo came from a patrician family with a long and distinguished military history. He excelled at school (liceo classico) and then the Naval Academy, and was decorated for bravery during the First World War. His biographer, Ovidio Ferrante (2005), claims that his pre-war training voyages in the Navy ‘predisposed him to a cosmopolitan vision of the world and reinforced his conviction that “the best culture that a man can develop is that of travelling and coming into contact with peoples and things that interest his spirit”’ (17–18; our translation). The principal cities of the north-eastern United States impressed him during a visit in 1909 where ‘he was struck by the vast size of these metropolises, the enormous technological progress, the incessant flow of people and cars at all hours, the high standard of living, the frenetic pulsing of life’ (Ferrante Reference Ferrante2005, 18; our translation). His 1925 Australian journal observes the progress of the former British colonies now united as an emerging modern, independent nation which he could compare with Italy or the United States.

De Pinedo's impressions of Australia and Australia's reception of the modern Italian

De Pinedo and his mechanic Ernesto Campanelli left Rome on 27 April 1925, arriving in Australia at Broome on the remote north-western coastline on 31 May. From there the two Italians circumnavigated most of the continent, flying south along the Western Australian coastline, then east across the Great Australian Bight via Adelaide to Melbourne, then north along the east coast visiting Sydney and Brisbane and departing from Cooktown on 13 August for Papua and New Guinea. They reached Tokyo on 26 September, departed there on 17 October, and returned to Rome and great fanfare on 7 November. It was the longest distance flight in the world at the time and the first return flight from Europe to Asia. It was also the first flight to Australia from Europe by someone from outside the British Empire, and the first by a single-engine aircraft (De Pinedo Reference De Pinedo1927).

The Australian media construed De Pinedo's visit as an encounter with European modernity, and this prompted reflection upon Australia's and the wider British Empire's own standing in relation to progress and technology. The Italian expressed his surprise at Melbourne journalists’ interest in his opinion on modern questions beyond aviation, commenting in particular on a reporter who sought his response to the ways in which the city managed its automobile traffic. While in Melbourne De Pinedo attended the opening of the Federal Parliament and paid particular attention to the Immigration Bill, which had an especial relevance for the Italian communities in Australia. He noted that Australians were ‘against immigration of coloured people’ and expressed surprise that Italians were generally not recognised as civilised and cultured Europeans (De Pinedo Reference De Pinedo1927, 105–106; our translation). Roslyn Pesman Cooper describes how Italian visitors to Australia have responded to Australians’ ignorance regarding Italy by commenting in turn on the unsophisticated, lazy, and materialistic character of Australian society (1993a, 176). She also argues that the superior British Australian attitude contributed to the level of support for Mussolini in the Australian community during the 1920s and 1930s:

The endorsement of Fascism in Italy rested in Australia as in Britain on assumptions about Italian inferiority and political immaturity. Italians were emotional, disorderly, melodramatic, volatile, child-like – in fact children. As such they were not yet ready for the responsibilities and duties of liberal democracy and both needed and desired strong leadership. (1993b, 351)

This patronising view of Italians inspires De Pinedo to comment on the value of his flight in ‘opening many people's eyes’, given that it had been preceded by only two, much slower, trips from Europe, both by Australian aircraft (1927, 106; our translation).

His analysis of the proposed immigration legislation is profoundly influenced by the geographical imagination made possible by his long flight along the remote Australian coastline. He understands the country as the successful product of waves of European migration which are now seen, in respect to the Italians at least, to threaten the favourable working conditions of the labouring classes. The tension between labour and capital is particularly sensitive in relation to the increasing presence of unskilled Italian workers in the sugar industry of North Queensland, home to by far the greatest concentration of Italians in Australia. De Pinedo is discreet in his account of this sensitive issue but he considers the sparsely populated country he has flown over as an undeniable indication of the need for wider European migration. The availability of land provides an opportunity for Italian migrants who are well equipped to ‘contribute enormously to the progress of this immense and magnificent region’ (1927, 107; our translation).

De Pinedo's assessment of an emerging Australian society discerns a welcome evolutionary divergence from the British source which might benefit from the contribution of other races in general and the emigrant Italians in particular. He notes that:

The absence of traditional prejudices, the love of independence from any kind of tie, of sports and a free life in the open air, and a frank and generous heart, give the Australian people a distinct appearance which inspires very great hopes for their future. (1927, 107; our translation)

One might read here an indication of changing Italian views of the ‘unparalleled superiority’ of the British Empire (Cerasi Reference Cerasi2014, 421; also Forlenza and Thomassen Reference Forlenza and Thomassen2016, 30). Laura Cerasi (Reference Cerasi2014) attributes a newfound sense in Italy of the decline of the British Empire to the transition from the liberal period into Fascism, and associates it with Fascist Italy's belated interest in acquiring its own imperial possessions. De Pinedo's interest in the departure of the Australian example from the British stock, however, is not shared – at least publicly – by the Italian Consul, Antonio Grossardi. He makes it clear in his address to the Australian Prime Minister and the group of distinguished Australians assembled to honour the aviators’ achievements that Australia was seen as a part of the British Empire and that Australians were considered a British people. For Grossardi the benefit of the Italians’ achievement was a strengthening of the bonds between the empires of Great Britain and Italy (‘Italian Aviators’ 1925, 3).

For De Pinedo, however, a significant driver of the divergence of the Australian from the British type, and one cause of the labour tensions that affect the immigration issue in Australia, is the high standard of education and associated level of literacy amongst the general Australian population. This educated populace promises a future of independence rather than colonial servitude. Pesman Cooper notes that Italian visitors to Australia typically considered Australians uneducated and that low levels of awareness of international affairs, while not restricted to Australia, were related to the small size of the intellectual class (1993a, 161). Yet De Pinedo (Reference De Pinedo1927, 108) notes that the relatively high level of general education makes it difficult to find workers for harsh manual labour. The existence of this educated, upwardly mobile working class drives up the cost of living and at the same time provides the illiterate Italian workers emigrating to North Queensland with a labour market advantage.

The aviator interpreted improved social conditions for women as another result of the Australians’ relative freedom from ‘social prejudices':

The young women conduct completely independent lives. They devote themselves to sport with passion and are treated fraternally by the men as real comrades. They are confident and intelligent, beautiful in their health and strength. This freedom from constraints and independence leads to greater frankness and less hypocrisy in social relations. The men are concerned firstly with their sports and then with their women friends, and the malicious gossip about young women which is a real scourge in other countries does not exist there. (1927, 108; our translation)

Pesman Cooper makes the point that De Pinedo's sense of the gender equality of Australia is more of a comment on the low position of women in Italy than an endorsement of the Australian situation (1993a, 173). As Jill Julius Matthews (2005) has shown, however, Australian women from all classes took advantage of the new commodities, technologies, entertainments, and opportunities on offer between the wars, and they understood these patterns of consumption as new conditions of an emerging modern relation with a wider world beyond the Empire.

This relative freedom of social expression is a modern condition which De Pinedo associates in rather conventional Australian terms with accelerated rates of suburbanisation. He views the dispersal of the population on separate blocks of land, as opposed to their concentration in blocks of flats, as an important influence on this emerging society. The spread is made possible by ‘rapid and well organised means of communication, wide and well paved roads’ (1927, 108–109; our translation), which recall both the Melbourne journalist's interest in foreign reactions to the system of traffic management and the younger De Pinedo's excitement at the bustle of New York. The Australia that the Italian aviator describes is an exemplary modern society in which ‘all the modern discoveries of science are appreciated and taken up with enthusiasm. There is no home – even a humble one – without a small radiotelephonic device’ (1927, 109; our translation). This interest in technology takes special notice of the effects of the modern on the working classes. So, his appreciation of the widespread parks and sports grounds notes how floodlit tennis courts provide evening access to recreation for working people who are committed to their employers during the daylight hours (1927, 109).

Mussolini's communication with the Australian Prime Minister Stanley Bruce in relation to De Pinedo's achievement makes a point of recognising Australia's ‘notable … social and civil progress’ (‘Mussolini Sends Greetings’ 1925, 7). The recognition of Melbourne as a world famous modern metropolis is also a theme of the Mayor of Rome's communication with his counterpart in Melbourne (‘Commander De Pinedo’ 1925, 7). Aviation is clearly configured here as a means of connecting the great modern cities of the world who share in traffic and exchange on the basis of their progressive embrace of modernity. The Melbourne Punch exemplified this view when it ran a series of cartoons and articles linking De Pinedo's visit with Australian attitudes to Italian immigration, and the promotion of international trade in the modern commodities of Britain, Europe, and the United States. Beside the prominently placed Leason cartoon that heads this essay it printed an article that made a point of associating the goodwill visits of foreign militaries with the promotion of their export industries in modern commodities (‘The Week in Politics’ 1925, 8).

Comparisons with prior British achievement and the USA's Pacific fleet

In Sydney, as elsewhere, De Pinedo was welcomed and fêted by a representative assembly of the body politic in the form of politicians, members of the judiciary, representatives of the public service, the military, commerce, industry and the churches, as well as what he refers to as the ‘Italian Colony’ (1927, 112). The capitalisation represents the Italian migrants as a significant grouping within Sydney society. Engine trouble delayed the aviators in Sydney and the Italian Consul there convinced De Pinedo to await the much-anticipated arrival of the United States Navy's Pacific fleet. He describes in his journal the spectacle of seven American dreadnoughts entering Sydney harbour amongst the smaller private craft chopping up the water and the over-flight of Australian and American ship-based aircraft which he elected to join. The occasion prompts him to reflect upon the way in which new technologies such as the aircraft and submarine have changed the tactical significance of capital ships in the Navy (1927, 114–115). The massive display of American industrial power in the form of their great warships and accompanying aircraft was specifically planned to assert American strategic interests in the Pacific. The powerful spectacle of this assembled technology upon and above Sydney harbour, however, is called into question from the elevated vantage point of one small Italian flying boat, as De Pinedo recognises the vulnerability of naval power to attack from the air. It is a point that his ultimate destination, Japan, will prove to the world when its aircraft cripple the American fleet at Pearl Harbour in 1942 (Sales Reference Sales1991, 41).

Departing Sydney on the same day as the US fleet enabled De Pinedo to claim fraternity with the Americans on the basis that they were military representatives on similar missions: ‘bearing from the east and the west the greetings of two nations that are friends of the industrious and dynamic Australian people’ (1927, 119; our translation). A comparison of the official welcome of his visit with that bestowed upon the Americans, however, reveals the ways in which racism constrained a white Australia and its openness to the more cosmopolitan forms of modernity espoused by both De Pinedo and the Italian Australian press.

The Australian Prime Minister Bruce hailed the Italians on arrival as the first aviators from outside the British Empire to fly to Australia from Europe. But he made sure to point out that British Australians had preceded them in this achievement (‘Prime Minister's Congratulations’ 1925, 19). Both the Prime Minister and the metropolitan Australian press admired the ‘unheralded’, ‘matter-of-fact’ nature of the Italians’ flight, which quietly and confidently assumed and executed its own success without any apparent need for advance publicity or extravagant display:

He came almost by surprise – untrumpeted, at any rate, by that voluminous stream of preliminary notices which nowadays familiarises us in advance with imminent events. His flight has been a matter-of-fact, service affair, to all appearance entirely confident from the outset – a good, clean, modest performance, without display, and, save for the slightest of incidents, without mishap. (‘The Italian Flight’ 1925, 8)

The acknowledgment of these qualities in the aviators runs against the vein of prejudice which construes Italians as ‘emotional, disorderly, melodramatic, volatile, child-like’ (Pesman Cooper Reference Cooper1993b, 351), and the Italo-Australian newspaper is quick to promote the ‘modesty’, which ‘has enhanced [Australians’] love of [De Pinedo]’ insisting that through his example ‘Old prejudices are forgotten. New ties are forged’ (‘A Great National Hero’ 1925, 1). The direction of this argument sits a little uneasily, however, alongside the paper's enthusiastic account of the vainglorious tribute paid by the inaugural president of the Italian Australian Association, Virgilio Lancellotti. The paper praised the ‘warm and prophetic eloquence of the sworn fascist’ – Lancellotti – who had been sent to Australia in November 1924 to prepare a report on the resident Italians for Mussolini (O'Connor Reference O'Connor1996, 143). Lancellotti's speech to the reception ‘boasts of the valour and intellect of [the Italian] race’ and acknowledges the aviators’ ‘audacity’ and ‘the tenacity with which they pursue their virile objectives’. It goes on to laud ‘the great and strong Man [Mussolini] who sets in motion and bears upon his shoulders the destinies of the Fatherland’ (‘I nostri bravi aviatori’ 1925, 2; our translation). The diction and rhetoric of the enthusiastic fascist could not have made a more pronounced contrast with the modest reserve of the distinguished aviator.

The Sydney Morning Herald qualifies its own admiration of Italian achievement by attributing their aviators’ undemonstrative self-assurance to the pioneering work already done on the route by British flyers before them, and the logistical support provided by British infrastructure along the way.Footnote 2 The Italians’ modesty is necessary and appropriate because it is made possible by prior British imperial achievement. Ross and Keith Smith's 1919 flight is therefore ‘more spectacular’, Raymond Parer's and John McIntosh's 1920 effort ‘more adventurous’ and, as a result, the ‘achievement of the Italian airmen has certainly been the smoothest and easiest of all’ (‘The Italian Flight’ 1925, 8).

In the Italian Australian press the reports of the aviators’ achievements are flanked by paid articles and even a poem extolling the role of Castrol oil and Shell fuel in enabling the successful conclusion of the flight.Footnote 3 One such article pointed out that ‘[t]he British-owned lubricant “Castrol” has been used in the world's greatest air achievements by pilots of all nations’. The company's Wakefield laboratories are as a consequence called upon to ‘fill big contracts with the aeroplane builders and users in Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, South America, Holland, China and Japan’ (‘Castrol’ 1925, 4). In the next column a poem titled ‘The Spirit of the Universe’ celebrates a ‘spirit … imprisoned through the ages’ that is ‘set free by man’ giving birth to ‘new dreams of Speed and Power’; this ‘marks man's triumph over time and space’ and ‘melt[s] away’ the ‘ancient barriers’ to ‘fashion bonds of brotherhood’ between the ‘airman, seaman, and the overlander’ whose ‘common bond’ is ‘the symbol of the Shell’ oil company.

So some of these commercial advertisements were willing to acclaim the Italian's membership of a distinguished international class of explorers, which they associated with the history of European imperialism and its modern commercial companies and interests. The commercial exploitation of the visit made a virtue of a multinational investment, which gave those companies a stake in multiple modernities (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2002). De Pinedo's associations with the Italian, French, and British automobile industries were exploited in large advertisements with FIAT and Italy prominent. Packard used its own connections with the visit of the US Fleet to promote an American alternative, while Rickenbacker exploited its brand association with the famous American fighter ace and race car driver (See Punch May-August 1925; Cauli Reference Cauli2019).

If De Pinedo offers Australia a point of connection to a new Italy associated with a developing international market for modern technologies, it is a connection that is qualified by a British racial emphasis, which is considered synonymous with a White Australia and its associated capacity for liberal self government. Reports in the Italian Australian press of the speeches made at the gala dinner in honour of the aviators qualify the parochialism of Australian reports in the metropolitan newspapers. Bruce is described by the Italo-Australian as sheepishly apologising for the ‘disgusting insularity’ which requires the Italians to speak in English, and as observing that Australians’ need for their own prior achievement before they are able to fully appreciate similar distinctions by another country is a ‘selfish’ trait (‘Commander De Pinedo’ 1925, 7; ‘Italian Aviators’ 1925, 3). On show here are the different modes of address used in an exclusive gathering of the body politic, which might claim ‘culture’ as a common ground with distinguished visitors, and in the more populist statements presented through the press to a wider public, which might claim empire, race, and nation as points of difference.

Figure 3. Advertisement for Lorraine-Dietrich engines citing De Pinedo

The Italo-Australian recognises the significance of this distinction in an article criticising the proposed changes to immigration laws which is set in the columns beside the report of De Pinedo's gala reception. The article, ‘European Immigrants’, cautions against political appeals to ‘the crowd’ as against ‘the best interests of Australian progress’. It then goes on to identify an Italian contribution to Australian democracy through Raffaello Carboni's involvement in the Eureka uprising. From there it moves to argue for racial hybridity and cosmopolitanism as the sources of cultural progression by describing the rise of Ancient Greece and the Elizabethan period in England as products of racial mixing, which in the case of Greece included ‘Europeans, Asiatics and Africans’ (‘European Immigrants’ 1925, 3–4). A front page article in the next issue headlined ‘The New Immigration Bill’ develops these arguments by making a distinction between the radical section of the Labor party, which called for the restriction of Italian labour, and the more supportive views of moderate Labor and Bruce's Nationalist Party Government. The proposed bill was to provide governments with the power to restrict the immigration of ‘aliens of any specified nationality, class, race or occupation’ and the Italo-Australian expressed its concerns about how a future government might wield that power against the Italians (‘The New Immigration Bill’ 1925, 1).

The manner in which these different formulations of race and nation are adapted to form associations and invoke distinctions can also be discerned in the welcome speech delivered by the Federal Treasurer Earle Page to the American naval personnel in Sydney. Page insisted that the Americans and the Australians were bound together by their shared inheritance of British blood:

You are not foreigners to us in Australia. Through us all the crimson thread of kinship runs. We are sprung from the same stock, and are partakers of the same nature. We look on your publicists and statesmen, like Hamilton, Washington, Lincoln, and Roosevelt, as essentially belonging, not merely to the American people alone, but to the whole English-speaking race, and we take pride in their achievements as displaying the genius of that race for developing and operating self-governing institutions. (‘Federal and State Dinner’ 1925, 13)

The link between language, blood, and democracy shows how fascism might be considered appropriate for Italy without being necessary for a wider settled, more modern, and more civilised, ‘English-speaking’ race. The Italian Australian press shows its sensitivity to these views by pointing out that a history of large-scale Italian migration to the US already meant that Italian blood ran in American veins and was therefore in part responsible for modern American prosperity (‘The New Immigration Bill’ 1925, 1; ‘The American Fleet’ 1925, 1; ‘European Immigrants’ 1925, 3–4).

Race and the question of labour and migration

De Pinedo's flight north into Queensland took him into the centre of the racial conflict involving the Italians in the sugar industry, and the Catholic Archbishop James Duhig was on the Brisbane River to welcome him in Italian. Duhig was an outspoken supporter of Mussolini and an apologist for Fascism, who developed a reputation in the 1920s and 1930s as a friend of Rome by frequently interceding on behalf of Queensland's Italian community.Footnote 4 His sympathetic biographer Thomas Boland (Reference Boland1986) describes him as at times a de facto Consul working to defuse the racial tensions by encouraging North Queensland's Italians into other occupations and promoting wider settlement. In a 1925 speech he sought to counter anti-Italian sentiment whipped up by some sections of the Australian Workers Union (AWU) by opining that ‘Italians are industrious, they develop rural industries, they provide the population the country needs, they are law-abiding people, … they become as good Australians as anyone else’ (quoted in Boland Reference Boland1986, 217). Duhig's control of elements of the Catholic press and his awareness of Australians’ ignorance about Italians make him an interesting contact for De Pinedo.

The AWU, which was agitating against the Italian workers in the sugar industry over concerns about their co-operative syndication and intense work ethic, was important to the then Labor Government of the State of Queensland. The premier, W.N. Gillies, was a canegrower and AWU member who represented the electorate of Eacham in North Queensland. Eacham was a British-Australian dominated sugar-growing area, but Gillies, one of the founders of anti-alien campaigns against non-European labour, was nevertheless a supporter of the Italians. He instigated the 1925 Royal Commission conducted by Thomas Ferry investigating concerns that ‘alien’ labour in the sugar industry was breaching working conditions, lowering living standards, and disadvantaging British workers. The Ferry Report made Italian immigration a national issue during De Pinedo's visit and, according to Boland (Reference Boland1986), the Italian aviators were used as ‘an argument for the clever and cultured Italians’. Archbishop Duhig is quoted in the Brisbane newspaper welcoming De Pinedo and Campanelli as allies in the Great War and countrymen of the man who conceived ‘the first idea of a flying machine': Leonardo da Vinci. According to Duhig:

in Italy, to which the whole human race is a debtor, religion, the arts, and sciences, and all the other elements of a civilization, ancient and venerable, still flourish with a luminous glory which, by the blessing of Heaven, shall never be extinguished. (‘A Fast Trip’ 1925, 7)

The Ferry Royal Commission found that the (northern) Italians in North Queensland were reliable workers who complied with Union conditions. It reached this position, however, only by officially recognising a racist distinction between white northern Italians and dark southern Italians, which ultimately attributed the problematic behaviours to the ‘coloured’ workers (Dewhirst Reference Dewhirst2014). When Prime Minister Bruce addressed workers in North Queensland on the Federal Government's response to the Ferry Report, he had to make a point of confirming the white European status of the Italian people.

Conclusion

De Pinedo does not pursue the contradictions between what impresses him about Australian modernity and what he understands as its problems and constraints. Nor does he use them to critically examine developments within his own country. His reflection on the Australian Italian community upon his departure returns to the importance of his flight for raising their standing in their adopted country and by so doing encouraging a patriotic but not necessarily fascist sense of fealty:

I left Innisfail amid applause and well-wishing by the Italians, those good people who through a life of struggle and sacrifice were laying the foundations of their future prosperity. The distant fatherland was alive in the hearts of those sons who had gone to the ends of the Earth. They considered the aircraft a vital piece of their native soil, and some watched over it the whole night through as if it was a sacred object. My presence in Innisfail meant that the fatherland cared about them and had not forgotten them. It was a sign, an invisible bond of love and trust carried by the wind over thousands and thousands of kilometres. (1927 127; our translation)

The aviator's experience and reception in Australia bear out David Brown's (Reference Brown2008) argument that support for fascism amongst Queensland's Italian community between the wars was less a commitment to politics and ideology than a response to the Fascist Government's interest and intervention in relation to the condition of Italian emigrants in Australia. Italian Australians received De Pinedo and Campanelli and their technological achievement as a welcome connection with Italy and its people, which might reaffirm them as worthy contributors to an evolving Australian society (Brown Reference Brown2008; Cresciani Reference Cresciani2003, 4–5; Pesman Cooper Reference Pesman Cooper1993a). De Pinedo is interested in Italy's distinction, but in a reserved, modest manner, prompted as much by Australian racial misconceptions as pride in Italian greatness. The aviator assumes that his achievement is a vindication of the modern Italian but in the interests of ‘harmony’ he does not insist upon it (‘Our Fine Aviators’ 1925, 2). He shows little awareness of Mussolini's preoccupation with Italy's fascist greatness and his own expectations of a modern Australia include a liberal interest in the improvement of the position of women, indigenous Australians, and a well-educated working class. This liberal interest is compromised by his belief in the progressivism of European imperialism in Africa, the Middle East, India, Asia, and the Pacific, but it is a more reserved and reflective position than that articulated by Mussolini when he cited De Pinedo as a model ‘new Italian’ in his 1925 speech to the Fascist Congress. De Pinedo's diary is characterised by the dispositions of the engineer and the diplomat rather than the politician or propagandist. The cosmopolitan self-confidence that he seems to draw from a combination of his privileged class background, liberal education, Italian heritage, and international travel, together with the new geographical imagination made possible by aviation technology, afford him another view of the threats and opportunities that modernity offers to the movement, co-settlement, and development of different peoples.

Notes on contributors

Christopher Lee is a professor of English at Griffith University. He has published widely on postcolonial and Australian literary culture and has a special interest in the social and political purchase of Australian cultural mythologies. His most recent books are an edited collection of essays and interviews entitled Trauma and Public Memory with Jane Goodall (Palgrave 2015) and an interdisciplinary study of the career and work of Roger McDonald, Postcolonial Heritage and Settler Well-Being (Cambria Press 2018). He is currently repatriating the work of Frank Hurley among the villages of the Gulf region in Papua New Guinea with Lara Lamb and writing a book on Aviation and Modernity.

Claire Kennedy is an adjunct senior lecturer in Italian Studies at Griffith University. Her current research on the Italian presence in Australia involves projects addressing the intergenerational impact of internment during the Second World War, with Catherine Dewhirst, and the significance of the Australian visit by aviator Francesco De Pinedo, with Christopher Lee. She is also investigating issues in the translation of language about violence with Luciana d'Arcangeli, as part of a project on the representation in the arts of violence against women.