Introduction

This article focuses on the ways in which Italian migration to the United States both affected and was affected by the process of nation-building in the newly constituted Kingdom of Italy. In particular, it examines the meanings that were presented to migrants about their consumption of food and drink produced for export – one of the issues that bound the political and commercial interests of Italy's ruling class most strongly together. The cultural experience of Italian migration is analysed by employing a transnational approach, which helps us to see how migrants played an active part in building links both within their host country and with their country of origin. The integration of migrants by no means represented a complete break with the world that they had left behind, even when their migration was definitive, not least because their countries of origin discerned their potential as a convenient means of lobbying or an entry point for commercial and political expansion (Gozzini Reference Gozzini2005; Portes, Guarnizo and Landolt Reference Portes, Guarnizo and Landolt1999; Gabaccia Reference Gabaccia1999; Nyberg-Sørensen, Van Hear and Engberg-Pedersen Reference Nyberg-Sørensen, Van Hear and Engberg-Pedersen2002). These developments and strategies have been referred to as ‘deterritorialised nation-state building’: processes whereby nation-building transcends the state's political and geographical borders and members of the diaspora have ties to two worlds without being fully part of either (Basch, Schiller and Szanton Blanc Reference Basch, Schiller and Szanton Blanc1994; Choate Reference Choate2008; Waldinger Reference Waldinger2015). Ewa Morawska (Reference Morawska, Gerstle and Mollenkopf2001) and Nancy Foner (Reference Foner and Foner2005) have both shown how the inherent duality of this phenomenon makes migrants both im-migrants and e-migrants.

In the Italian case, emigration generated not only a deterritorialised nation but also deterritorialised nationalism, an idea explored more generally by Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1996); in other words, the nation, and national sentiment, was present wherever its members lived, whether inside or outside Italy's formal borders. Moreover, a form of state-sponsored transnationalism was in operation; in this, the state used policies on citizenship, based on the concept of ius sanguinis, either to encourage return migration or to maintain legal connections with emigrants, who were regarded as working externally rather than as permanently departed (Douki Reference Douki, Bishop, Green and Waldinger2016). As Mark Choate (Reference Choate2007) points out, Italians were the largest contingent of transatlantic migrants, and unlike the other large groups – the Irish, Poles, and Jews – they came from a national state, rather than from multinational empires. While these empires recognised the existence of ethnic minorities within their territory (Jacobson Reference Jacobson1995), the Italian state was the relatively recent outcome of the unification of regional states, which had launched a slow process of giving Italians a sense of national belonging. Emigration clearly had the potential to jeopardise the construction of the idea of ‘italianità’ (Italianness), but at the same time represented an opportunity and a challenge in the determination of the Kingdom of Italy's role in the international context. As a result, mass migration to the United States affected the nation-building process, which then had implications for the fortunes of transatlantic migrants. Italy could be described as both an ‘emigrant nation’, something that covers a population both inside and outside national borders, and a ‘patria espatriata’ (‘fatherland abroad’), which refers instead to the continuing loyalty that the country expected from its emigrants (Franzina Reference Franzina2006). In the first few decades after Italian unification things went further, with the development of a concept of the nation-state related to a community by descent, and thus closely linked to blood and kinship (Banti Reference Banti2011); membership of the national community was understood as being determined by birth rather than resulting from free personal choice, making the concept of a ‘nation’ biological as well as political.

While labour history, like political history, has demonstrated the wide circulation of both people and ideas, the history of consumption has been experiencing a particular proliferation of research since the later 1990s. Building on the idea that practices of consumption reflect collective as well as personal identities, and national identities on a broader front, studies have explored a wide range of phenomena within different disciplines, from economics to political, social and cultural studies (Trentmann Reference Trentmann2016; Cavazza and Scarpellini Reference Cavazza and Scarpellini2018; Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua1981; Gabaccia Reference Gabaccia1998; Cinotto Reference Cinotto2001, Reference Cinotto2008; Luconi Reference Luconi2002, Reference Luconi2005; Zanoni Reference Zanoni2010, Reference Zanoni2012, Reference Zanoni and Cinotto2014, Reference Zanoni2018). Food and dietary practices, specifically, are very important for an understanding of the transnational developments under way in migration processes. Diet, alongside language and religion, is one of the most important elements that characterises a group. Although diet can be subject to change and hybridisation, the illusion of tradition can be generated by myths about the authentic origins of food and food practices; this illusion moulds and is at the same time reinforced by their fixed nature over time. Many different factors affect modes of consumption, over and above what is available to eat or drink. Regarding any specific dish, there are the issues of when, where, why, and with whom it would or would not be eaten. Sociocultural bridges and barriers are thus established by the acceptance or rejection of specific foods, whose meanings and modes of consumption change over time and across space in the dialogue between the producers, traders and advertisers who present foods to the market and their consumers. These processes create strong links between national identity and transnational consumption (Bernhard Reference Bernhard2005; Long Reference Long2015; Belasco Reference Belasco2008).

The debate regarding migration, ‘Greater Italy’ and the turning point of 1896

From the 1880s and 1890s onwards, emigration was an issue central to political discourse in the newly created Kingdom of Italy. Debate quickly polarised around two positions: the first, which expressed the perspective of circles linked to the commercial world, favoured free emigration; the second, which reflected the interests of the landowning bourgeoisie, was hostile, believing that this would lead to a decline in the rural population and a consequent increase in labour costs (Tintori Reference Tintori and Collyer2013). The ruling class of the 1880s generally regarded migration as an issue relating to public order, and entrusted responsibility for it to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The perspective depicted by all the legislative measures then in force inclined towards the management and suppression of offences, rather than care for the emigrant; there was no evidence of ‘sufficient awareness of the complexity of the problems posed by emigration, which had become a way of life for a sizeable proportion of the Italian population’ (Manzotti Reference Manzotti1962, 35). The debate over emigration intensified in the light of the contribution by Rocco De Zerbi, the spokesperson for the parliamentary commission on emigrant living and working conditions, which drew attention to the important connections between economic opportunities and migration. The need to identify outlets for Italian products, which had been hard hit by the escalation of the customs war with France in the late 1880s, drove people to consider emigration in relation to economic and trade issues; at that point, however, political perspectives on migration were still split into different schools of thought that were typically characterised by imperialism (Sori Reference Sori and Bezza1983). The turning point came in 1896, after Italy's defeat at Adua by Ethiopian forces, when Francesco Crispi's policy of military expansionism fell apart (Labanca Reference Labanca2002, 57–94), sidelining Africa and military conquests as central aims of Italian foreign policy. There was a similarly profound shift in the strategies of the Istituto Coloniale Italiano and the Società d'Esplorazione Commerciale in Africa (Milanini Kemény Reference Milanini Kemény1973). Diplomacy came to the fore, and an important aspect of this was the approach to emigration:

[This] became the essential element in imperialist thinking and in the approach, in consequence, to Italy's role in the international system. The issue of emigration became the lens through which the colonialist movement observed the relationship between the national and the international, and generated its development of an expansionist approach that was closely linked to an authoritarian conception of the state. (Monina Reference Monina2002, 14)

Emigrants were allotted responsibilities:

The task of these new champions of Italianness will be to penetrate the country's commercial world, see which ventures offer the best guarantees of success, and which interests should be cultivated, in relation to trade with the mother country, and call in Italian involvement. The workers invited must in some way be selected: the weaker elements, as well as bringing their country into disrepute, will never make their fortune and will go back poorer than before. … The economic advantages will be no less than the cultural advantages, because settlers who remember their own country, in their soul, will also remember it in their material aspirations. They will consume Italian products and will seek to extend the consumption of these among the host population; they will want to introduce the products of their activity abroad to Italy; and because goods are exchanged for goods, our commerce and our industries will profit. It would be wonderful … if we were to see the fruits of Italic energies all contributing to the benefit of our stock and increasing our potential for expansion. (Terzolo Reference Terzolo1914, 175)

An alternative model of colonialism was thus appearing. In the wake of Adua, this had been set out in the journal Riforma Sociale by Luigi Einaudi. In his view, which represented feelings widely held in Turin's middle-class circles, the real colonisers were not the military conquerors of barbarian or semi-barbarian territory but the people who successfully employed the energy of industry and trade to extract profit from regions whose riches had not yet been appreciated by their backward resident populations. Industry and commerce were the arenas in which a ‘Greater Italy’ should be developed, with its strength based on culture, the market and civil society, rather than on military conquest. The state should assist, guide and educate its emigrants, and thus create this Greater Italy by means of cultural, financial and commercial institutions (Nani Reference Nani2006). The idea of a network of institutes and associations started to take shape; these would promote Italianness abroad in order to ensure that Italian emigrants, still closely tied to their country of origin, would constitute an important pressure group in their host country. The success of the strategy set out by Einaudi in his well-known Un principe mercante (Reference Einaudi1900), which combined economic and political elements, depended on an awareness that the export of Italian goods was part of an overarching national mission rather than a merely commercial development: exporters, importers and consumers all needed to share the vision of an economic and commercial Greater Italy. Migrants, whether or not they were aware of this, were charged with representing Italy abroad by laying the foundations for the economic links that would benefit their homeland (Choate Reference Choate, Embry and Cannon2014).

The efforts to imbue Italian emigration with a national spirit led to a reconsideration of national identity within Italy's political borders. The need for this had also been confirmed by publication of the first enquiries into the living conditions of the lower classes, which had forced Italy's process of nation-building to take race, gender and class into account; in particular, they described the contrast between northern Italians – seen as racially superior – and southerners. This contrast also became apparent overseas, at the gates of Ellis Island, where American officials categorised northerners and southerners differently, and thus confirmed for the former that they were further up the North American racial hierarchy than their southern compatriots. In the US Immigration Commission's report of 1911, Italians were in fact divided into two distinct ethnic and linguistic groups; with reference made to the studies by Giuseppe Sergi and Alfredo Niceforo, northern Italians were placed in the ‘Keltic’ group and southerners in the ‘Iberic’. In addition, the report's ‘Dictionary of Races or Peoples’ included entries for ‘Sicilian’ and ‘Calabrian’, which although not regarded as two distinct ethnic groups were still seen as elements meriting their own description and characterisation (Perlmann Reference Perlmann2018, 29–31; Benton-Cohen Reference Benton-Cohen2018, 168–99; Folkmar and Folkmar Reference Folkmar and Folkmar1911, 29, 81–5, 127–8).

Food and drink consumption, national mission and Italian identity

Italy ‘outside Italy’ and the ethnicity of Italian-Americans were above all constructed through the circulation of newspapers, whose readers became conscious of their membership of a community from sharing rituals and a collective imaginary. As Benedict Anderson has said, ‘the newspaper reader, observing exact replicas of his own paper being consumed by his subway, barbershop, or residential neighbours, is continually reassured that the imagined world is visibly rooted in everyday life’ (Reference Anderson1991, 35–6). In the interwar period, alongside the press, means of communication such as the radio and cinema were central both to product promotion and to the success of particular companies. Radio could reach out to people with a limited education, including many immigrants, engaging them with an oral style of communication, and entering ‘into the privacy of their domestic life, which in turn emerged remodelled in both its routines and its practices’ (Fasce Reference Fasce2012, 84; see also Goodman Reference Goodman2011, Craig Reference Craig2000, and Newman Reference Newman2004). Various studies have argued that the radio stations of the 1920s and 1930s, which ranged from non-profit bodies to organisations whose principal focus was advertising, were crucial elements in the public's transformation into Americanised consumers, who as a result were less tied to their respective ethnic groups (Cohen Reference Cohen2008; McChesney Reference McChesney1993; Smulyan Reference Smulyan1994). In the Italian case, the growth of commercial radio stations actually strengthened Italian-American identity rather than weakening it (Luconi Reference Luconi, Giunta and Patti1998). Many businesses sponsored radio programmes as well as placing advertising during broadcasts, in a system that crossed over with print media. The Italian Reveries Broadcasting Company, for example, which started life in March 1933 and just a few months later became the Italo-American Broadcasting Company, listed Lodovico Caminita, editor of the newspaper Il Minatore in Scranton, Pennsylvania, among its founders. The firms that bought advertising time during the station's ‘Italian-American Variety’ show could claim corresponding space at no extra cost in the paper. This advertising ‘helped to maintain the ties of Italian Americans to their traditional ethnic food and cuisine because they effectively advertised Italian-oriented alternatives to US large-scale brands’ (Luconi Reference Luconi, Giunta and Patti1998, 62); the financial crisis, especially, saw the growth of American chain stores at the expense of small local ethnic shops, but not in the ‘Little Italies’ of cities like Philadelphia, or at least not until after the Second World War. Moreover, companies like Prince Macaroni, in Boston, launched initiatives that were just for Italians, such as the competition started in February 1935 in the Gazzetta del Massachusetts and the Italian News, which offered Italians in Boston the chance to appear on the radio. To take part, consumers had to send a wrapper from a Prince Macaroni product to the radio station offices, indicating the nature of their performance. There was to be a weekly ten-dollar prize awarded on the basis of the number of votes cast by listeners, and an overall prize of 50 dollars for the best entry from all the weekly winners, with the chance of being signed up for further radio concerts:

Can you sing? Do you play an instrument? Can you act? Are you a storyteller? Do you know any traditional songs? Whether you sing in English or Italian, if you have artistic inclinations this is your chance to enter a weekly competition and win a radio contract. ANY ADULT ITALIAN CAN COMPETE. The ‘Prince Macaroni Company’ offers you this auspicious opportunity to take the first steps towards fame … money … and the privilege of taking part in high-quality Italian radio programs in the future.Footnote 1

A key strategy of this company, managed by Gaetano LaMarca, was to promote Italian-American culture by offering compatriots in the Boston area the opportunity to highlight their ethnicity within the context of the American dream (Newton Reference Newton1966). As we see, the competition also envisaged active involvement of the public at home: people could vote to determine a competitor's victory or defeat. Radio listeners were particularly responsive to these messages and engaged in active exchanges with the producers, as illustrated by the letter that Joseph Valinote of Philadelphia wrote to Ralph Borelli, the director of Italian programmes for Station WRAX, thanking him for his advice on which stores he should use for his shopping (Luconi Reference Luconi2002).

Within this general context, the Italian state started to redetermine both its own role and that of Italians inside and outside its political borders. There was a growing tendency to equate migrants with the great explorers of the past like Columbus, and traders were increasingly often represented as present-day warriors and apostles of Italian civilisation and industriousness. In the second half of the nineteenth century, stereotypes had developed that portrayed Italians as a weak and racially inferior people; now, in response, they were to be seen as a population led by the merchant princes described by Einaudi, worthy of respect from the nations of the West. In a publication printed in Rome in 1918 to celebrate US involvement in the First World War alongside Italy and against the Central Powers – with the Columbus Day celebrations providing the occasion – the image that Italy needed to project abroad, especially in its economic and trade relations with the United States, was clearly set out:

In the future, Italy cannot be just any other country for America, outside the orbit of its political and economic operations. We are now linked to America by the ties of our experience of the current war and by financial ties, not to mention – as in the past – the ties of emigration. We must value these ties as much as all our moral and material strengths, in order that the great American people hold us in esteem and join us in our future history. Let us remember that if not for the war the features of the twentieth-century world might not have been notably Americanised, but in fact the stream and pulse of American life, through the contacts required by the war, has powerfully penetrated the weakened old Europe. … In the face of actual reality, those romantic understandings of Italy, from the timeworn opinions of French, English and German writers and whomsoever else, will have to be permanently eradicated, or at least confined to the desk drawers of literati. Americans should no longer talk about the ‘garden of Europe’ as a destination for honeymoons and educational or health tours, but as one for business, trade, powerful transformation and mutual transfusion of capital and labour, humanity and learning, for a quicker and better route towards development. The American Union now wishes to dedicate a day to the Italian Christopher Columbus, one of the greatest men of our richest historical period, the Italian Renaissance, which has left its indelible marks across the world in an enduring and constantly renewed impression; his lofty spirit perhaps oversees his country's new fortunes, not, we hope, at the point when his sceptical and traditionalist city ignored his offer of power and wealth, but at the more auspicious moment when America calls to mind, remembers and acknowledges its ancient mother. Let us not squander this providential occasion.Footnote 2

Italians, it was felt, needed to present themselves as a united people, heirs to the great explorers and traders, who now had strong leaders – white and male – behind them and should no longer be subjected to the derision and discrimination of the previous period. Starting from this position, the nascent advertising industry provided essential help to traders in creating associations that connected everyday migrant life to an Italy represented either by politicians and impressive historical figures, or by news events that had been given extensive coverage in the United States and had led to the construction of a shared sense of belonging. Food and drink products were often linked to images of the Italian royal family, as in the choice of name and symbol for the ‘Savoy Wine & Importing Company’, an import business in Boston, which established a link between the goods they were trading, including the Branca, Martini & Rossi, Bisleri, Gancia and Cinzano brands, and the Savoy dynasty (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Advertisement for the Savoy Wine & Importing Company, La Gazzetta del Massachusetts, Boston, 14 August 1909. Source: IHRCA.

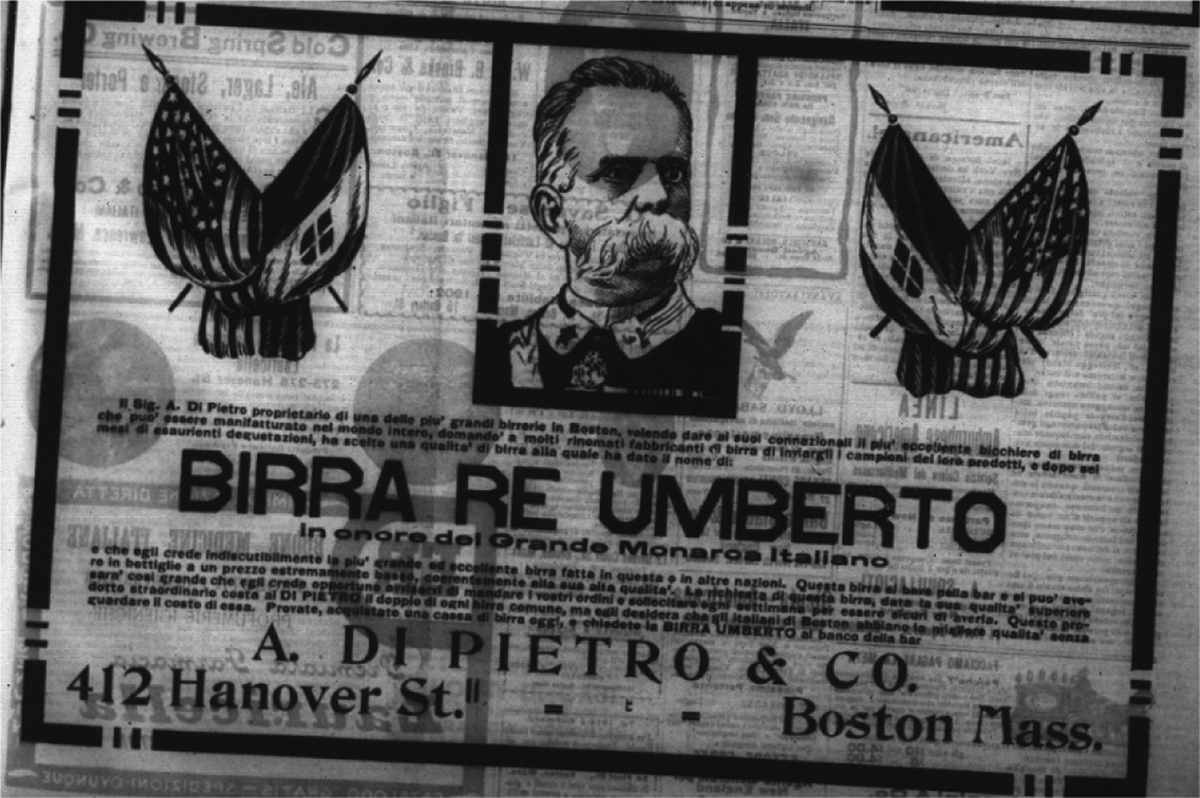

The brewers A. Di Pietro & Company, also in Boston, created a brand in honour of Umberto I of Savoy. The advertising for this beer featured both a picture of the king and the flags of Italy and the United States (see Figure 2); by consuming this company's product, its promotion suggested, Italian emigrants could maintain links with their country of origin.

Figure 2. Advertisement for ‘Birra Re Umberto’, La Gazzetta del Massachusetts, Boston, n.d. (1890s?). Source: IHRCA.

Linked to use of the figure of the king was the idea of an Italian community, both part of the Italian nation and its representative abroad, which had a guide and father still watching over it even though it found itself outside the homeland's borders. On the one hand he was entrusting Italy's migrants with a mission, the spread of Italianness in political, commercial and cultural arenas, and on the other he was offering them an image that could give them succour in the midst of America's racist society. At the same time, however, there was the need to energetically re-establish respect for the Italian ruling class. In the preceding period this had been subjected to wounding attacks by the mainstream American press and elite, exemplified by the double illustration published on 12 April 1891 in the Philadelphia Inquirer, at the height of the tension and controversy that followed the lynching of 11 Italian-Americans in New Orleans the previous month.Footnote 3 The pictures mocked the Italian king, the minister for foreign affairs and the ambassador, who were all depicted using the racist stereotypes customarily reserved for Italian immigrants: Rudinì, the minister, appears as an organ grinder, while King Umberto is a peanut vendor accompanied by Ambassador Fava as a monkey, carrying a collecting bowl. In the first, US Secretary of State Blaine, taking some peanuts from the barrow, causes the king to fall over; in the second, we see the reaction from King Umberto and Rudinì, who are busy sharpening a stiletto – the stereotypical mafia weapon – in readiness for their encounter with Uncle Sam (Salvetti Reference Salvetti2003, 22–3).

The linkage of product consumption to the greatness of Italy and its expansion also applied to particular brands, such as Fernet-Branca, which was presented as ‘the glory of the Italian nation, because it carries the name of Italy, admired and respected, to all corners of the globe’.Footnote 4 The figure of Christopher Columbus also served to promote a new era of Italian economic and cultural imperialism, made possible by emigration. Previously, this Genoese navigator had been celebrated in the United States as having helped to bring Christianity and civilisation to America, without any emphasis on his being Italian. Members of the Knights of Columbus were actually primarily of Irish origin, and remained so even during the period of mass emigration from Italy; when the ‘Columbian Exposition’ was held in Chicago in 1892–3, the group organising the celebrations was of ‘WASP’ rather than Italian background (Connell Reference Connell2013; Bushman Reference Bushman1992). At around this time, the growing body of migrants from Italy started to place increased emphasis on Columbus's Italianness; Columbus Day, given official recognition by the US authorities, was claimed as a day of Italian pride, and statues and monuments to the explorer were unveiled in locations that were emblematic of the Italian presence in American cities. In these ways, people attempted to create memories and narratives that allowed Italianness to be credited as having contributed to the process of American nation-building (Michaud Reference Michaud2011). This annual celebration had a double significance. Firstly, it was given formal recognition, whose import was well expressed in the 1918 ‘Columbus Day’ pamphlet quoted earlier:

President Wilson has declared Columbus Day a national federal holiday across all the US states, while before it was only celebrated in 33 states of the North American Union. This auspicious date, an Italian glory, now establishes the closest bond between the two nations, the United States and Italy, in that it connects the history of the past to the no less glorious and momentous story of current events.Footnote 5

Secondly, when celebrations, whether secular or religious, took place in a city, they served to highlight the presence of the Italian community in particular streets and districts. As a result, advertisers also tried to link the consumption of specific products to images that referenced Italian traditions such as the Viareggio Carnival, using their meanings and associations to indicate the correct way to perform these same traditions.Footnote 6 In the public arena, such performances delineated the cultural boundaries between Italian districts and those occupied by the ‘others’, especially from the 1930s onwards. Furthermore, some companies took advantage of these occasions to promote their own goods: during the festival of St Anthony, the Torino Bakery in Chicago, for example, handed out slices of bread that were then blessed by the priest at the altar and distributed to the faithful.Footnote 7 Then there were the district markets and shops that depicted the ‘dietary panorama’ (Cinotto Reference Cinotto2001, 184) that existed in the memories of second-generation Italian-Americans, not just through their physical presence but also thanks to the advertising, which emphasised the necessity of frequenting the places that offered the products of ‘tradition’ in order to experience these festivals with proper respect for Italian culture. In this regard, Atlantic Macaroni did all it could to emphasise how essential its products were to the proper celebration of every event, including the festival of the local patron saint, birthdays, New Year's Day, Christmas and Easter.Footnote 8

The purchase and consumption of specific goods was also linked to important figures of the Italian Risorgimento, especially Giuseppe Garibaldi, pictures and representations of whom were offered as free gifts, and whose name was adopted by businesses (see Figure 3), and Ettore Fieramosca, who had become a sort of iconic Risorgimento hero thanks to the novel by Massimo d'Azeglio, Ettore Fieramosca, o La disfida di Barletta (Reference d'Azeglio1833).Footnote 9 The figure of Garibaldi, as Lucy Riall argues, was used as ‘the physical embodiment of a series of values and truths with which Italians should identify and so construct a sense of national community’ (Reference Riall2007, 7), and on his death he was also celebrated by British newspapers such as The Times, which noted that Garibaldi's adventures had fascinated people right around the globe (Riall Reference Riall2007, 388). Some products were placed at the heart of the process of Italian unification, like the Florio brand of Marsala wine: its advertising stated that ‘Garibaldi, before marching on Naples, landed with the Thousand at Marsala; after a brief stop he felt so refreshed that he no longer doubted his forces, and we know that some days later he entered Naples in triumph’.Footnote 10 Florio Marsala thus claimed for itself the legacy of the exploits of the Thousand: its consumption could therefore meld Italian consumers who had emigrated to the United States into a united and respected community.

Figure 3. Advertisement for ‘Cyrilla’ olive oil from the Garibaldi Company, Il Risveglio, Des Moines, 1923.

Source: IHRCA

There was also no shortage of references to contemporary celebrities, such as Enrico Caruso and Gabriele d'Annunzio. An olive oil produced by the Southern Olive Oil Company of New York and, notably, one of Atlantic Macaroni's types of pasta, were associated with Caruso, while Busalacchi Brothers Macaroni of Milwaukee dedicated another type to d'Annunzio a few months after his death.Footnote 11 In the early 1920s a brand of pasta was even named after Benito Mussolini, by the Indiana Macaroni Company: this initiative ended up under attack from the San Francisco newspaper Il Corriere del Popolo, which made its view crystal clear:

Let us add neither cheese, nor tomato sauce, nor comment to ‘Mussolini Brand Maccheroni’, to avoid an encounter with the noble wrath and the noble tastes of the dictator, whose order to seize the republican Corriere might be extended across the seas and over the mountains, or who might have us given a generous measure of ‘Mussolini Brand’ oil, making it very hard for us to digest the tasty ‘Mussolini Brand’ maccheroni.Footnote 12

Italy's entry into the First World War saw the emergence of brands that laid fresh claim to the Latin heritage of Italians, such as ‘Lucullus’ olive oil, advertised by the Gusmano Brothers firm in Chicago.Footnote 13 Subsequently, in the 1920s, there was an increasing number of specific references to Romanness; the Ajello-Bozza company of Naples, for example, presented ‘Romolo’ (Romulus) olive oil, while the branding of ‘Claudia Roman Imperial Mineral Water’ of New York suggested that the Roman emperors had already availed themselves of its product.Footnote 14 Perhaps the most interesting case is the publicity for Ferro China Roma liqueur by the New York company Thomas Pipitone. In the first of two advertisements the product is not pictured at all, but a close relationship between the Capitoline wolf and the Pipitone company is established; in the second, the liqueur bottle stands alongside a Roman legionary and the caption declares that ‘you can acquire energy and health and also make your children grow up healthy and strong, like the ancient Romans, by always drinking Ferro China Roma’.Footnote 15 These specific references to Romanness corresponded with developments in Italian nationalist circles from the first decade of the twentieth century onwards, when first Libya and subsequently the territory beyond Italy's north-eastern border became pressing issues on their agenda. Latinness and Romanness were qualities to be contrasted with the barbarism of the Slavs and Bolsheviks of the East, and also suggested a historical justification for the conquest of Libya and the return of Italy's aspirations to an empire (Roccucci Reference Roccucci2001).

Fascism took this process to a new level, by not stopping at a simple reclamation of the past but using it as the basis for constructing a new civilisation; in Emilio Gentile's words, ‘the “new Italians” that Fascism wanted to forge were supposed to be the Romans of modernity’ (Reference Gentile, Dingee and Pudney2009, 149). The Italian emigrant therefore clearly needed to be represented as heir to the legionaries who had created not just the Roman Empire but also Romanness, a concept that went beyond the borders of the Italian state and projected Fascism into a universal dimension, ‘so as to impress the brand of Italian genius on a new era of modern civilisation’ (149). During the Fascist dictatorship, there were numerous attempts by Mussolini to exploit the Italian masses in the United States, both politically and economically, as a pressure group that could provide support to Italy's economic, military and political plans. The regime's propaganda, however, mainly focused on extolling the virtues of Italianness, Italian culture and blood ties, which the Italian ruling class believed should persuade first- and second-generation Italian-Americans to favour goods imported from Italy. As a result, images that referred directly to Mussolini's regime were rare other than at times of major political and patriotic mobilisation such as the Ethiopian campaign.

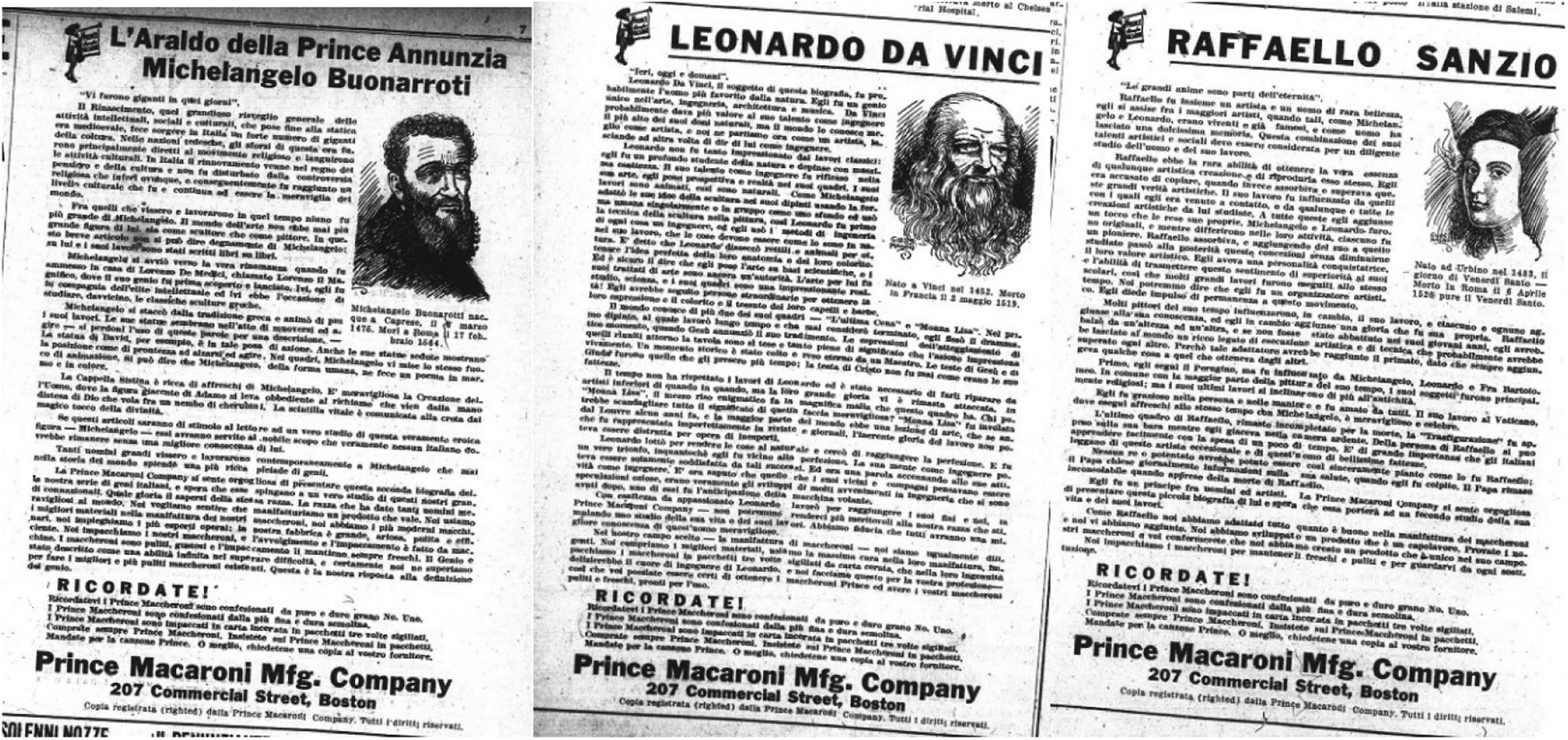

Alongside the reprise of Latinness and Romanness, there was the enlistment of literary giants like Dante (Audeh and Havely Reference Audeh and Havely2012; Looney Reference Looney, Connell and Pugliese2018). The poet's name was adopted by, for example, a restaurant in San Francisco, which also linked the home-made character of Italian cuisine to his image, and was applied to an olive oil produced in Italy by a Genoese company, Giacomo Costa, but sold on in the United States by Schroeder Brothers of New York.Footnote 16 The only female historical figure in use, linked to Dante, was Beatrice: ‘Donna Beatrice’ olive oil was available from Beatrice Distributing of Brooklyn from the 1930s onwards.Footnote 17 The images linked with Italian products thus tended to negate time and space, suggesting the existence of a nation and a people before this had actually come into being. Historical figures, removed from their context, could be used in a way that served to represent the greatness of a people that had rediscovered its supposed ancient unity and strength. These figures worked to create a sense of continuity that linked the emigrants’ Italian ethnicity to a race with inherent qualities that had been passed down over the centuries. An excellent example is the campaign regarding ‘Italian genius’ launched by Boston's Prince Macaroni in August 1933, which involved the publication of short biographies of great Renaissance men such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael (see Figure 4). The qualities and traits of each character were then attributed to the company and its products, emphasising Italian pride in belonging to ‘the same race … that has given so many wonderful men to the world’.

Figure 4. Advertisements by the Prince Macaroni Manufacturing Company, La Gazzetta del Massachusetts, Boston, 12, 19 and 26 August 1933. Source: IHRCA.

Leonardo thus played his part:

With the precision of the impassioned, Leonardo worked to attain his goals: we – the Prince Macaroni Company – could not be of better service to our race than by encouraging study of his life and works …. In our chosen field – the manufacture of pasta – we are just as conscientious. We buy the best ingredients, use the greatest care in their processing, and pack the macaroni in waxed-paper wrapping sealed three times, the ingenuity of which would have elated Leonardo the engineer; we do this for your protection, so that you can be sure of getting your Prince macaroni and having it clean and fresh, ready for use.

With Raphael, the emphasis was placed on his capacity for improving on the wealth of artistic knowledge he acquired over time. Prince Macaroni claimed similar abilities:

Like Raphael, we have adapted everything good about the manufacture of macaroni and added to it. We have developed a product that is a masterpiece. Try our macaroni, and you will confirm that we have created a product unique in its field. We pack the macaroni to keep it fresh and clean, and to protect you from any substitution.

Italian businessmen, from producers to dealers and importers, became increasingly important as points of reference and intermediaries through whom the Italian-American ethnic community could be reached. Some companies started as basic home-based businesses, often set up in basements with very rough and ready hygiene and working conditions, but then adopted an American model for organising their production, which in due course, in the case of pasta for example, almost entirely superseded imports of the same product from Italy. Although imports of Italian products initially increased in volume (Italian Chamber of Commerce 1937), in a direct relationship with the large influxes of migrants to the United States, subsequently ‘Italian-style’ goods played a crucial part in the construction of an Italian identity, rather than a regional one, in the United States. Italian-American producers grasped the fact that the demand for Italian food did not necessarily mean that food produced in Italy was needed, and ‘the need for symbolic consumption that some foods answered could be satisfied with astute advertising, presentation and packaging, as these imitators of “ethnic” foodstuffs well realised’ (Cinotto Reference Cinotto2001, 352).

Conclusion

While the governments of Liberal Italy strove to create an ‘Italy outside Italy’ and concentrated on instilling national sentiment in Italians, both at home and abroad, Fascism demanded that Italians should remain Italians and keep faith with their country of origin. Mussolini's regime took to their extremes some developments already apparent in Liberal Italy, especially in the ideas of Cavour and Edmondo De Amicis that shifted the genealogical discourse regarding membership of the nation closer towards its description directly in terms of race. Italians were no longer seen as emigrants but as ‘Italians abroad’, with nationality increasingly linked to a belonging by blood – and therefore by race – that should automatically have led Italian-Americans into expressing their loyalty to Italy and Fascism. The 1920s and 1930s saw the launch of various campaigns regarding support for Italy, including one in 1925–6 on payment of the war debt and one in 1935–6 on support for the Ethiopian campaign, which had resulted in the League of Nations imposing sanctions on the country. On both these occasions, Italian-Americans were strongly encouraged to buy Italian goods, thus linking the activity of consumption to patriotic action for their country of origin. In Fascist discourse the nation retained its spiritual quality, but also became something very material. Studies by both Gentile and Alberto Banti have drawn attention to the role of the idea of racial stock, which was an element of Augusto Turati's formulation within the Fascist catechism: ‘more than 50 million Italians who have the same language, the same customs, the same blood, the same destiny, and the same interests: a moral, political and economic unit that is totally fulfilled in the Fascist state: that is the nation’ (Turati Reference Turati1929, 18).

In contrast with Liberal Italy's governments, Fascism was operating in an American environment where, firstly, there was a growing impetus towards limiting immigration, expressed in the restrictive legislation of 1921 and 1924, which appreciably curtailed the fluidity and temporary nature of much transatlantic emigration; secondly, the second generation of Italian-Americans now outnumbered the first. The regime therefore had to reckon with a cohort, often disparagingly described as a ‘hyphenated generation’, that had never known Italy other than through their parents’ stories or images presented in the mass media. Maintaining loyalties to the country of origin therefore became a more complex task and engendered a political strategy based on ‘parallel diplomacy’ (Luconi Reference Luconi2000), which aimed to make use of Italian-Americans as a lobbying force in the United States. After the collapse of the Fascist League of North America (Pretelli Reference Pretelli2005a, Reference Pretelli, Pretelli and Ferro2005b, Reference Pretelli2006, Reference Pretelli2008), various important bodies that had been promoting Italy and Italianness, among other Americans as well as Italian emigrants, were reorganised and ‘Fascistised’ with the purpose of creating an international climate favouring Fascism. The use of images relating directly to Mussolini's regime was seen as counterproductive, as it would have encouraged suspicions that a foreign country was interfering in American politics and society. However, the outbreak of the Second World War and the consequences of Italy's alliance with Germany, lining it up against the United States, exposed the superficial nature of Italian-American support for the Mussolinian project, despite the earlier general enthusiasm over the invasion of Ethiopia and proclamation of the Italian Empire, which had generated tension with the African American community (Venturini Reference Venturini1990; Ventresco Reference Ventresco1980).

In this brief contribution we have seen how the process of constructing national belonging was shaped around the lives and life experiences of migrants, taking account of the socio-economic environment of the host country, the United States, where the culture of consumption was more developed than in Italy. The integration of migrants in this context was used by businesses and advertising agencies to aid pursuit of the political, economic and commercial objectives of the Italian ruling class, by attempting to construct a strong sense of expatriate Italianness that would coalesce around a shared idea of the Italian nation and spirit. This attempt was only partly successful, because although Italian-Americans laid claim to their Italianness in the face of other ethnic groups, they still maintained their regional divisions within the Italian community. As consumers, they continued to respect internal regional differences, especially in the comparison between North and South.Footnote 18 Ernesto Dalle Molle, for example, remembered how his daily meals were conditioned by his parents’ origins in northern Italy, and as a result his diet differed from that of his southern compatriots, which to him seemed alien. Another second-generation Italian-American, Rosamond Mirabella, noted a change in the style of ravioli, the traditional holiday food, when a particular regional group – Tuscans – arrived and introduced the use of a meat filling alongside the familiar ricotta.Footnote 19 Italian expatriate identity can thus be understood as being both transnational and translocal, with the sense of national belonging often overlapping with awareness of a more local identity through the maintenance of affective, cultural and economic ties.

Translated by Stuart Oglethorpe

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors of the journal, Stuart Oglethorpe for the translation and the anonymous referees for their thoughtful suggestions. I am also grateful to the organisers and participants at the 2019 ASMI Postgraduate Summer School, which gave me the opportunity to improve my article.

Note on contributor

Federico Chiaricati teaches at the Istituto storico Parri in Bologna. He obtained his PhD in 2019 at the University of Trieste, with a dissertation on the role played by food consumption among Italian-Americans in building a cultural, economic and political transnational network. His principal research interests are the history of Italian migration and food history, and his most recent publication is ‘Terra di Fame e di Abbondanza, tra storia dell'alimentazione e public history’, Clionet. Per un senso del tempo e dei luoghi 3 (2019).