Introduction

Before examining the use of iconic images in Italian political communication, it is worth quoting the definition given by the leading art historian Martin Kemp in his book Christ to Coke. How Images Become Icon:

An iconic image is one that has achieved exceptional levels of widespread recognisability and has come to carry a rich series of varied associations for very large numbers of people across time and cultures, such that it has to a greater or lesser degree transgressed the parameters of its initial making, function, context and meaning. (Kemp Reference Kemp2011, 3)

In the light of this definition, while focusing mostly on Italian iconic images as they are employed in Italian propaganda, I shall also deal with the question of their migration to entirely different geographical and cultural contexts to serve other ends.

This article will begin by considering religious works of art for propaganda purposes in Italy in the early post-war period, and discuss the revival of this practice during the referenda campaigns of 1974 and 1981. It will then comment on the political symbols that Italian parties used for decades to visually characterise themselves, their near-disappearance in the early 1990s and their replacement with new motifs. The phenomenon of the appropriation of both traditional and new left-wing icons by right-wing and far-right parties will then be investigated. Lastly, the article will deal with the persistence of fascist, and even Nazi, imagery in the publicity of some contemporary political organisations.

Before dealing with the subject of icons in detail, it is worth remarking that images have always played a major role in political communication. This is because they are more immediate than words, and also vaguer, thus more apt to affect us emotionally than rationally. Moreover, because our visual literacy tends to be less developed than our verbal one – visual studies plays little or no part in school curricula, which privilege the written word – we are more likely to succumb to the mysterious fascination of pictorial artefacts.

Another general point that needs to be made is that graphic artists often draw from a repertoire of well-established images because the latter’s visual impact has been proven. Iconic images are potentially effective, even when they are ‘borrowed’ in a revised form, because what is already familiar to us, consciously or subliminally, can be absorbed more easily. It should also be noted that graphic designers often turn to ready-made, second-hand materials, instead of creating new ones, out of practical necessity: because they are required to produce visual artefacts quickly, to respond to social and political events.

Religious art for Christian-Democrat propaganda

Great works of art are eye catchers and, through the cultural prestige they enjoy, can help legitimise messages. Even when they deal with religious themes, or precisely because they do, famous works of art may prove useful to political parties. Christian iconography is Manichean in character; as such, it lends itself to being exploited for propaganda purposes since the argumentation of political parties is largely based on the dialectics of conflict between opposite views.

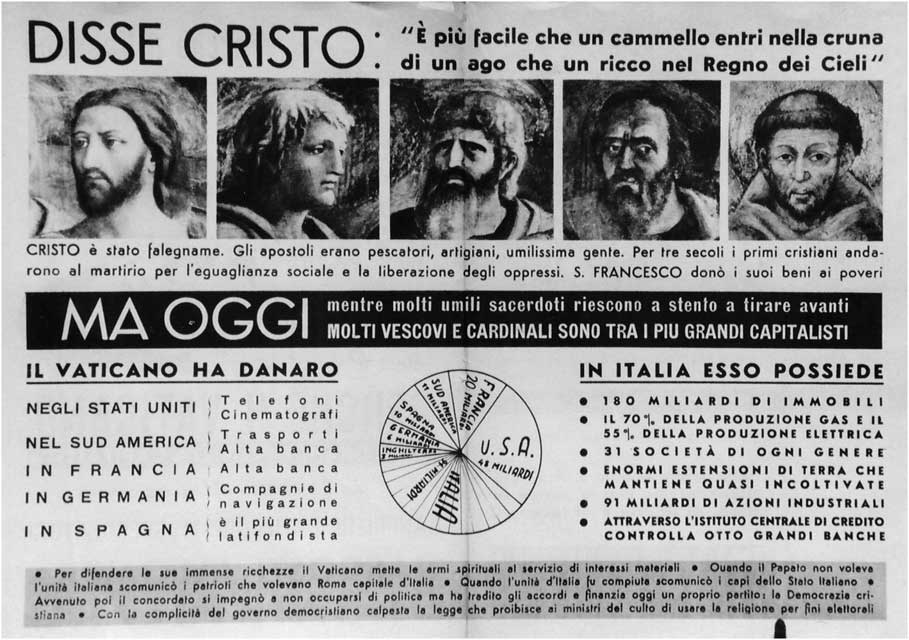

In the late 1940s and in the 1950s, Renaissance works of art depicting religious themes, or images based on their iconography, frequently featured in political posters, especially those of the Christian-Democrat party (DC) and of the organisations that supported it. Their main purpose was to characterise them as Christian. A 1946 poster inviting the public to vote for the DC relied on a Madonna-and-Child typology to depict a woman holding a little boy; another poster, produced by the Catholic ‘task force’ Comitati civici for the 1953 election campaign, featured a Christian worker crushing two monsters that represented ‘comunismo’ and ‘capitalismo’ in the pose of St Michael/St George slaying the dragon. Equally interesting, although intended for mostly internal use, is a poster produced by the DC shortly before the local elections of 1956 to announce a national meeting to discuss strategies to ‘Liberare i comuni dai fiduciari di Mosca’ (free town councils from Moscow’s agents): it is illustrated with a detail from the Expulsion of the Devils from Arezzo, part of the fresco attributed to Giotto that decorates the Upper Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi (Fig. 1). Left-wing parties, too, occasionally depicted masterpieces of religious images on their printed publicity: their aim was to fight their opponents using their arguments or to suggest affinities between Christianity and socialism in order to refute the traditional accusations of atheism (Various Authors s.d. [but 1983], 226–229; Novelli Reference Novelli2000, 46–47). A leaflet issued by the Fronte Democratico Popolare (the Communist-Socialist electoral alliance) in 1948 reproduced the portraits of Christ and three of the apostles painted by Masaccio and Masolino in the Brancacci Chapel (Chiesa del Carmine, Florence), as well as Cimabue’s portrait of San Francis (Lower Basilica of Saint Francis, Assisi), together with Christ’s words ‘It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God’ (Mark 10:25), in order to denounce the ‘capitalism of the Vatican’ (Fig. 2).Footnote 1

Figure 1 ‘Free the town councils from Moscow’s agents!’. DC poster announcing a national meeting intended to discuss the programme for the approaching local elections, 1956

Figure 2 ‘Christ said: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God”’. Fronte Democratico Popolare brochure, 1948

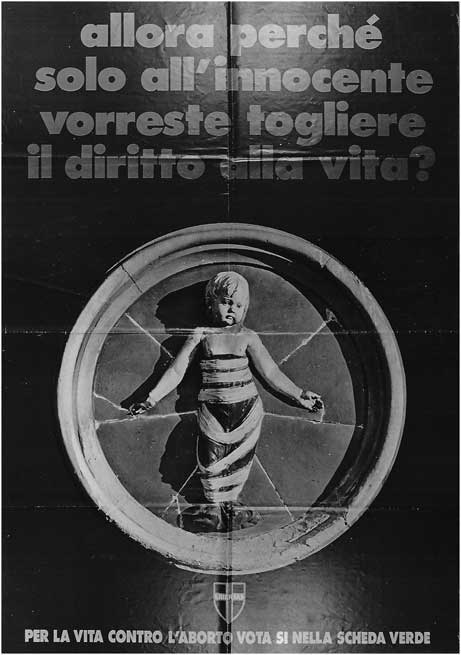

The practice of using religious images gradually disappeared with the growing secularisation of Italy, but enjoyed a revival during the campaigns for the referenda on divorce (1974) and abortion (1981). A DC anti-divorce poster depicting a dejected mother with a baby on her lap and an older child leaning on her knees (Fig. 3) is based, albeit in reverse, on the Leonardo cartoon for the Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John (National Gallery, London). Another poster, issued by the Movimento per la Vita (Pro-Life movement) and designed by the artist Pietro Annigoni (well known in Britain for his portraits of Queen Elizabeth II), depicts a woman in intimate eye contact with her baby (Fig. 4) – a composition modelled on Donatello’s so-called Pazzi Madonna (Bode Museum, Berlin). Here too, the source has been used in reverse. A further example is the Christian-Democrat poster of 1981 reproducing a glazed terracotta roundel by Andrea della Robbia (Fig. 5). The swaddling baby featured on it is not a specifically religious motif; the choice of this work serves the DC’s anti-abortion stance well because this roundel is part of a series that features on the façade of Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence, one of the first orphanages of Europe. The purpose of these artistic appropriations is to attribute the institution of the family and conception a sacred character, and to suggest that divorce and abortion are totally alien to Italian civilisation. Della Robbia’s swaddling babies may not have been universally known, but in Florence, where the poster was designed and disseminated, this motif would have struck a chord.

Figure 3 ‘The law on divorce harms the weakest: the children’. DC poster, referendum on divorce, 1974

Figure 4 ‘Say YES to life’. Pro-Life movement poster, referendum on abortion, 1981. Drawing by Pietro Annigoni

Figure 5 ‘So why do you only wish to deprive an innocent being of the right to life?’. DC poster, referendum on abortion, 1981

Religious art for secular ends

Renaissance masterpieces depicting religious subjects have not been adopted only to connote political movements as Christian. In Italy and elsewhere, civil right and political organisations have at times used them secularly, exploiting their generic symbolism, to depict events or situations they wish to censure.

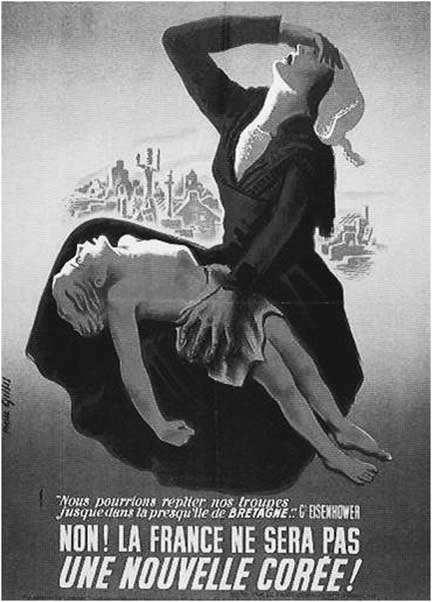

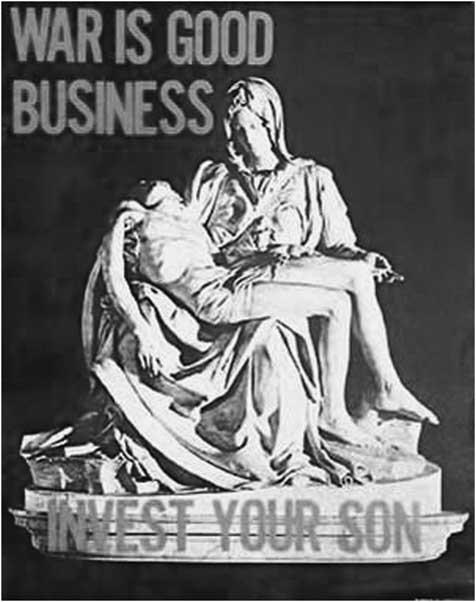

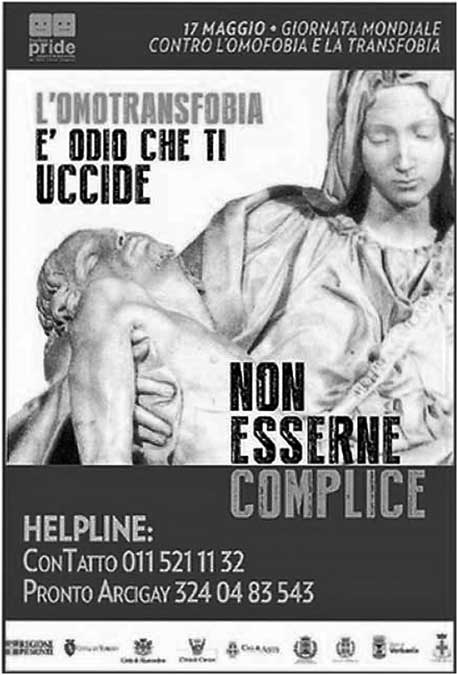

By far the most represented work of art is Michelangelo’s Vatican Pietà. Across cultures, this powerful image has come to represent emblematically the slaughter or harassment of innocent people. It was used, for instance, in a French Communist Party poster of 1951 attacking American intervention in Korea and the plan envisaged by General Eisenhower to remilitarise Northern France (Fig. 6), in a pacifist poster produced in 1969 by the International Solidarity Movement to demand an end to American involvement in the Vietnam war (Fig. 7), and in a poster of 2003 to denounce the massacre of Palestinian youths perpetrated by Israeli soldiers (Fig. 8). The Pietà was also reproduced in 2015 on a poster issued by the Piedmont Region on the occasion of the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia (17 May) (Fig. 9). Monica Cerrutti, assessore ai diritti (chair of the civil rights committee) explained: ‘[the Pietà] is a work of art that belongs to the whole of humankind. The message it wishes to express is also universal: compassion, exactly the opposite of what homophobia and transphobia are for us’.Footnote 2

Figure 6 ‘Our troops could return [to France] and go as far as the Brittany peninsula’ (General Eisenhower). ‘No! France will not be a new Korea!’. French Communist Party poster, 1951, designed by Paul Gilles

Figure 7 International Solidarity Movement, anti-Vietnam war poster, 1969

Figure 8 Poster denouncing the massacre of Palestinian youths perpetrated by Israeli soldiers, 2003

Figure 9 ‘Homophobia and transphobia is a hate that kills. Don’t be part of it’. Piedmont region poster, 2015

Michelangelo’s Pietà is universally so famous that it occasionally features in totally extraneous cultural contexts. For instance, an Indian print that was diffused in Calcutta in 1948 shortly after Gandhi’s assassination depicted Bharat Mata, the Hindu goddess who embodies the Indian nation, mourning Bapuji, the Father of the Nation, in the pose of Michelangelo’s Virgin holding her Son (Fig. 10).Footnote 3

Figure 10 Bharat Mata, goddess of the Indian nation, mourning Gandhi. Print, 1948

Other famous Renaissance works have also been used in social and political graphics. Michelangelo’s iconic image of the near-touching hands, which represents God breathing life into Adam (Sistine Chapel, Rome) is the obvious source of a French Communist Party poster (c.1980) that depicts the hands of an employer and of a worker to call for the creation of jobs (Fig. 11). The graphic designer has thought it appropriate to ascribe the right side, God’s side, to the worker, rather than to the employer. In another French poster (c. 1990), produced by the anti-racist organisation SOS Racisme, the motif of the two hands has been used to depict emotional intimacy between two people, as the slogan ‘J’aime qui je veux’ (I love whoever I want) attests (Fig. 12). Here too the position of the two hands in relation to each other has been thoughtfully worked out: the black person’s hand occupies the superior right side. A British Labour Party billboard (c. 1988) used the same motif, together with the slogan ‘Tory Health Policy. More Plastic Surgeons’, to denounce the Tories’ private health policies: the life-creating hand of the surgeon draws near the hand of his patient to take his credit card before treating him (Fig. 13). The Sistine Chapel detail also appears in a poster designed by the students of the Academy of Fine Arts of Beijing to accompany a text honouring the young people who went on a hunger strike on 13 May 1989 to demand democracy (Fig. 14): the near-touching hands are here intended to represent the determination of New Democracy supporters, whom the regime has repressed and dispersed, to keep in touch with one another.Footnote 4

Figure 11 ‘Employment’. French Communist Party poster, c. 1980

Figure 12 ‘I love whoever I want’. SOS Racisme poster advertising an anti-racist rally in Paris, c. 1990

Figure 13 Labour Party billboard at a Lancaster car-park, c. 1988

Figure 14 ‘The people united. To the youths who went on a hunger strike on 13 May 1989 to defend democracy’. New Democracy poster produced by the Academy of Fine Arts of Beijing, 1989

Political masterpieces for social and political campaigning

Modern works of art feature more rarely in the literature of political parties. However, one Italian painting that has repeatedly been used is Pellizza da Volpedo’s Quarto Stato (Fourth Estate, 1901, Museo del Novecento, Milan). This iconic work spells political activism, social reform, workers’ rights and women’s rights, and is mostly associated with the Socialist Party, PSI, which promoted it through its press shortly after it was realised (Various Authors 2001; Nano, Ellena and Scavino Reference Nani, Ellena and Scavino2002).

Portraits and symbols as political icons

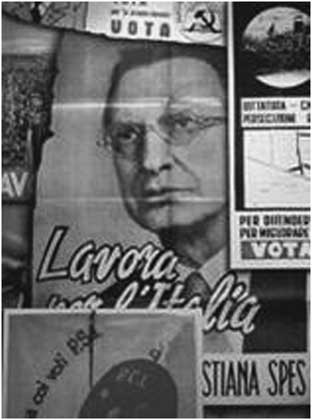

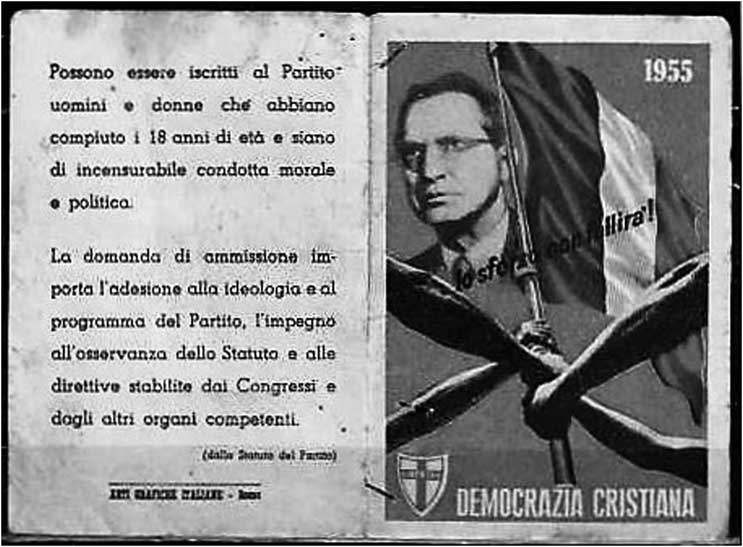

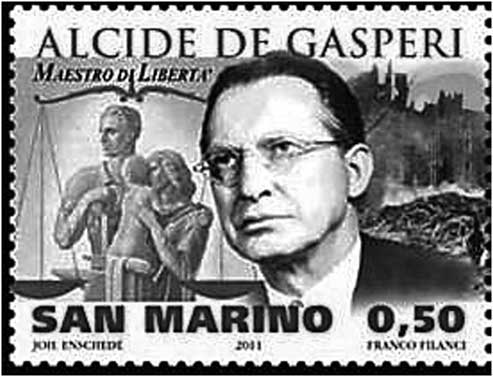

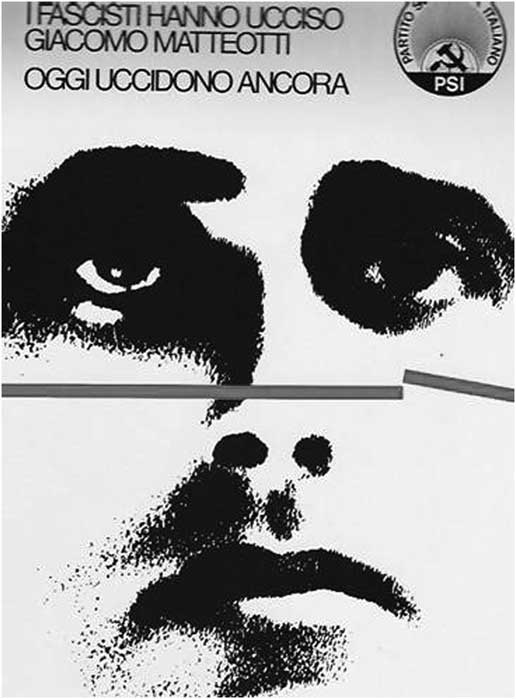

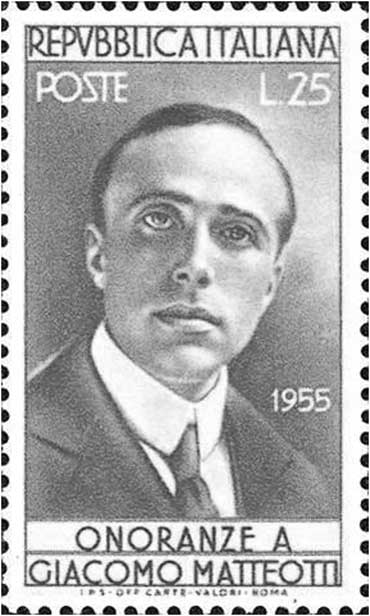

Of course works of art are not the only type of iconic imagery that political parties have relied upon to strengthen their identity. Suffice it to recall such symbolic motifs as the red flag, the clenched fist, the hammer and sickle, the rising sun and the crossed shield, as well as the portraits of personalities such as Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Gramsci, Giacomo Matteotti, the Socialist deputy murdered by the fascists, Che Guevara, the DC leader Alcide De Gasperi and the PCI leader Enrico Berlinguer.Footnote 5 The effigies of these seminal figures may be referred to as icons not only because they are immediately recognised by many people, but because of the parties’ tendency to use the same portraits logo-fashion in their publicity. Portraits tend to be selected on the basis of their capacity to project specific images of the leaders. For instance, the image of De Gasperi with an austere expression, that was first used in the propaganda posters of the parliamentary elections of 1953 and later repeatedly reproduced in the literature of the DC, evoked the rigour and determination of the man who, allegedly, had led Italy out of economic catastrophe. De Gasperi’s gaze fixed above him characterised him as a visionary and spiritual leader (Figs. 15–16).Footnote 6 Socialist publicity represented Matteotti with a sad expression and eyes looking upwards (Caretti Reference Caretti2004) following the iconography of the Christian martyr who turns his eyes towards God (Figs. 18, 19, 21). These effigies became so well established as to transcend party boundaries: for instance, both have been reproduced on commemorative stamps (Figs. 17, 20).

Figure 15 ‘[De Gasperi] works for Italy’. DC poster, parliamentary elections, 1953

Figure 16 DC membership card featuring De Gasperi’s portrait, 1955

The end of traditional political icons and the Quarto Stato’s new lives

In the early 1990s, with the collapse of the DC and PSI following the judicial investigations into political corruption, the so-called Mani pulite (Clean Hands) trials, and the evolution of the Communist Party, PCI, into an avowedly social-democratic party (Partito Democratico della Sinistra, PDS, later Democratici di Sinistra, DS), which allied itself with the former left-wing faction of the DC, and eventually (2007) merged with it to form the Partito Democratico, PD, many of the well-established, ideologically-charged symbols and historical figures virtually disappeared from the visual publicity of the main parties. The Quarto Stato, deprived of a specific party association, continued to be used, but almost exclusively by social organisations (pressure groups, trade unions etc.) as a generic symbol of social and political commitment.Footnote 7 For instance, a poster produced by the left-wing recreational association Arcigay in 1992 to campaign for safer sex features a cartoon drawing of a group of marching men, one of whom holds a baby in the pose of the mother and child of Pellizza da Volpedo’s masterpiece, together with the slogan ‘Uniti contro l’AIDS’ (Cheles 1995a, 66).

When political parties do use the Quarto Stato in their literature now, it is usually to satirise it by subverting its original political message. A Forza Italia billboard promoting the candidature of Ivan Benussi to the mayorship of Bolzano in 2005 reproduces the painting with words from the Italian Communist anthem Bandiera rossa (Red Flag) (Fig. 22) – an obvious act of provocation, given Benussi’s strong fascist and neo-fascist pedigree, well known locally: his father was a member of the Decima MAS (the commando frogman unit created during the Fascist regime) and later a local councillor for the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI (Fregona Reference Fregona2013). Another Forza Italia poster, issued during the general election campaign of 2001, satirises the Quarto Stato more subtly. It depicts a woman with a baby before a row of people in contemporary garments representing various professions: an architect, a doctor, an airline pilot, a worker, a (black) cook etc. Unlike the original painting, which represents the demands of the proletariat and their class solidarity, the poster celebrates a contented inter-classist society, ready to entrust Berlusconi with the solution of Italy’s employment problem.Footnote 8

The Quarto Stato is little known to the general public outside Italy,Footnote 9 but traces of it may be found in political artefacts far afield.

The first example we shall consider is the mural Justice of the Plains, painted in 1938 by the Regionalist artist John Steuart Curry in the Department of Justice Building in Washington, DC as part of the Federal Art Project launched by President Roosevelt to provide employment to artists and boost the morale of the country (Fig. 23).Footnote 10 It depicts families of pioneers with their covered wagons and cattle confronting the attack of two masked outlaws, and features a striding woman with a baby in her arms that seems indebted to the female figure painted by Pellizza da Volpedo. Since Curry was strongly interested in political art – such an interest had led him to spend an extended period in Paris in 1926 to study the works of Gustave Courbet and Honoré Daumier (Junker and Adams Reference Junker and Adams1998) – it is not implausible to presume that he was acquainted with the Quarto Stato and treat the near-quotation of a detail from this painting as a private homage to a socially committed artist.

Another striking example is provided by a banknote issued by the Central Bank of Iran in the early 1980s (Fig. 24). Its obverse side represents a group of people marching in support of Ayatollah Khomeini that is based on the Quarto Stato, as is suggested by the special emphasis placed on the small group of figures at the head of the march, by the presence of a woman on the right and by the shadows they all cast. The Italian painting must have been thought of as an appropriate source of inspiration for a picture celebrating the recently-established Islamic revolution. The Quarto Stato could have been known to some Iranian artists because the regime of the Shah was considerably open to Western culture. That Western art is at times used as a source of inspiration to promote revolutionary Iran is also attested by a poster that depicts the apotheosis of Khomeini, blatantly based on a Madonna painting by the seventeenth-century Spanish artist Murillo (Chelkowski and Dabashi Reference Chelkowski and Dabashi2000, 172–174).Footnote 11

New icons

To return to Italian political iconography, the old icons have been superseded by new ones, such as the rainbow flag with the word ‘Pace’ (Peace) in its centre and the ‘Hope’ poster designed by Shepard Fairey in support Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign (Fairey and Gross Reference Fairey and Gross2009), which, in view of the popularity they enjoyed, have been at times appropriated by right-wing politicians. A subtly deceitful right-wing use of the rainbow flag is the billboard produced in 2005 to advertise the candidature of Giovanni Pace, an MP representing the ‘post-fascist’ party Alleanza Nazionale, AN, to the governorship of the Abbruzzo Region. The candidate’s surname, the choice of the font and the coloured strips motif were all used to evoke the Peace flag. The aim was to conceal his far-right convictions and present a modern, progressive image that might appeal to (ill-informed) left-wing voters too (Cheles Reference Cheles2012, 144–146).

Similar appropriations of left-wing icons by right-wing and conservative parties and movements are current elsewhere too. In France, during the campaign for the 2012 presidential election, the leader of the Front National Marine le Pen advertised a meeting at Paris-Dauphine university with a stylised portrait of herself clearly inspired by Barak Obama’s ‘Hope’ poster (Cheles Reference Cheles2012, 128, 141). In 2014, campaigners protesting against the Mariage pour tous (Marriage for All) Bill granting equal rights to same-sex and heterosexual couples, used graphics that were modelled on those of May ’68 in order to project a libertarian and transgressive image (Figs. 25–26) (Zeller and Wandrille 2013). To attract media interest, their massive demonstrations even featured the presence of the ‘Homen’, a specially created group of young men with painted slogans on their bare chests, that were intended as the male equivalent of the Ukrainian protest group Femen (though, curiously, unlike the latter, they wore masks to conceal their identity) (Cusset Reference Cusset2013, 21; Ackerman Reference Ackerman2013). The protesters were trying to persuade young people, the vast majority of whom approved of the Bill, that their marriage-for-straights-only message was ‘très cool’. The proponents of the Bill responded by enlisting the support of the ultimate French icon, Marianne, shown in posters kissing a female companion (Figs. 27–28).

The far right’s enduring symbols

I argued earlier that the images that were part and parcel of the identity of the parties of the First Republic have virtually vanished with them. This may true of the DC, PSI and PCI, but not of the far right. In 1995 the MSI notably transformed itself into Alleanza Nazionale, AN, an allegedly moderate and modern right-wing party. Yet, despite claims that fascism had been relinquished – hence the party’s definition of itself as ‘post-fascist’ – AN relentlessly clung to its roots, as is evidenced by the many iconic motifs drawn from the rich fascist and neo-fascist repertoire which regularly featured in its graphic output hidden in plain sight. Some examples will illustrate this practice.Footnote 12

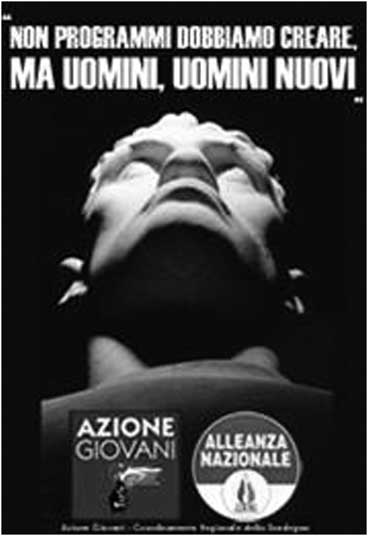

The logo of the university movement of AN, Azione Universitaria, made up of an open book with a superimposed feluca (the traditional cocked hat of Italian university students) was modelled on the insignia of the Gruppi Universitari Fascisti, GUF (Figs. 29–30). The acronym of AN’s youth group, Azione Giovani, led by Giorgia Meloni from 2000 to 2009 (as co-ordinator first, and president later), appears in some publicity as a stylised amalgamation of the Celtic Cross and the swastika: it has a whirling movement and hooked edges (Figs. 31–33).Footnote 13 It so features, for instance, on the armband worn over a black shirt by a female activist, depicted on a recruitment poster of 2007(Fig. 34). This attire is strongly reminiscent of that worn by the Hitler youth and other Nazi paramilitary and military organisations. A sticker bearing the logos of AN and Azione Giovani, c. 2004, reproduces a sculpted portrait of a figure with Mussolini’s traits, together with the slogan ‘Non programmi dobbiamo creare, ma uomini, uomini nuovi’ (It is not programmes that we must create, but men, new men) (Fig. 35), which is none other than a quotation from a text by the Romanian fascist politician Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, the founder of the Iron Guard:

The country is dying for want of men, not for want of programmes. That is our opinion. And that is why it is not programmes that we must create but men, new men. Because the men of today, educated by politicos and infected by Jewish influence, would compromise the most splendid programme (Codreanu Reference Codreanu1936, 286).Footnote 14

Fascist symbols were not relinquished by Alleanza Nazionale leaders when their party merged with Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà, PDL, in 2009. Giorgia Meloni, who was entrusted with the leadership of Giovane Italia, the PDL’s youth movement, and Gianni Alemanno, during his period of office as mayor of Rome (2008–2013), did not miss opportunities to use them. A recruitment advert for Giovane Italia, c. 2010, featured two membership cards so composed as to form Mussolini’s monogram (Fig. 36) – a motif that was ubiquitously represented during the Ventennio (Fig. 38). The advert’s design may have been inspired by an MSI card of 1972 (Fig. 37) to subtly suggest a continuity with the past. The logos Alemanno chose in 2010 for the Formula Uno race that was to take place in Rome and in 2012 for the city’s new emblem both integrated the Duce’s iconic ‘M’ in the word ‘Roma’. In the first motif, which included a stylised rendering of the Palazzo della Civilità – the highlight of the fascist-built EUR district –, the letter was emphasised through the use of red colour; in the second by turning it into the shaft of the pillar on which rests the Roman she-wolf (Figs 39–40). Neither symbols were ultimately adopted because the Formula Uno project was scrapped and the Rome emblem was found to be aesthetically poor.Footnote 15

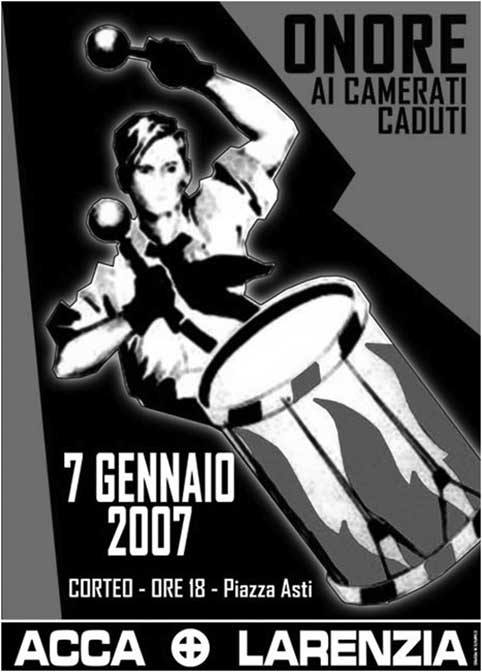

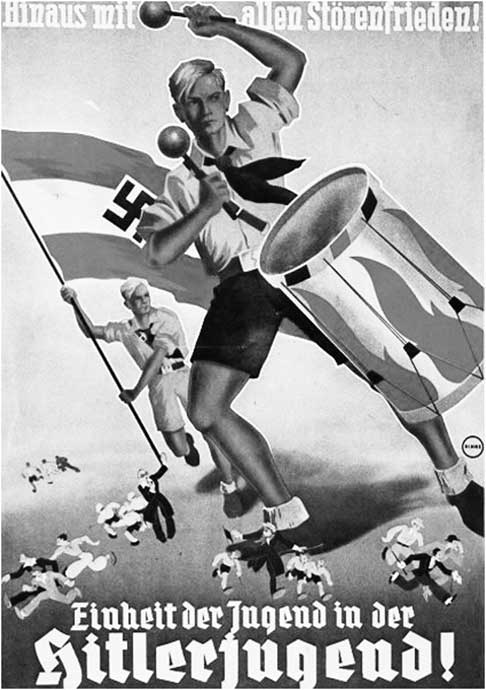

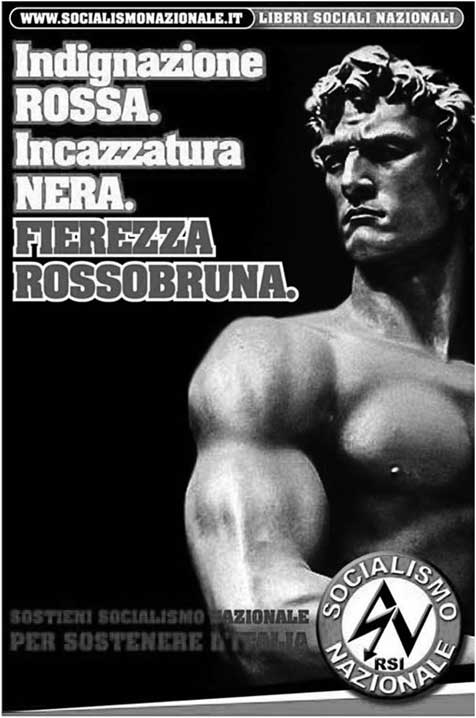

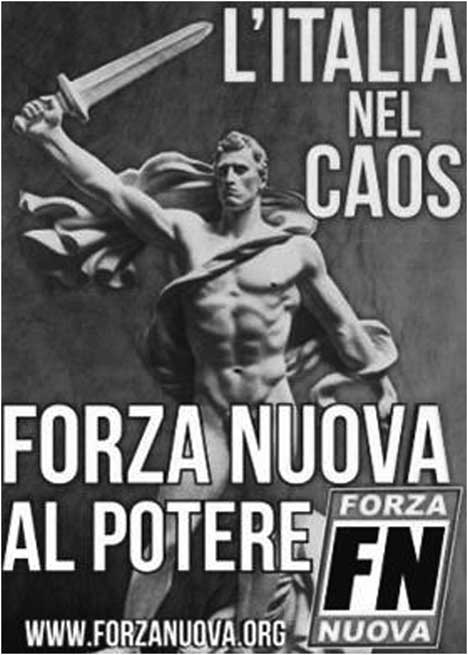

Iconic images from Nazi art and propaganda also feature regularly in the publicity of far-right organisations. A poster of 2007 bearing no party logo commemorated the killing of three young MSI activists in via Acca Laurenzia, in the popular Tuscolano district of Rome, in 1978,Footnote 16 using a Hitler Youth recruitment poster (late 1930s) in slightly adapted form (Figs 41–42). The larger-than-life statues of Arno Breker, who was ‘Official State Sculptor’ of the Third Reich, have repeatedly been cited visually in the literature of extreme right groups: for instance, Bereitschaft (Readiness, 1939, Arno Breker Museum, Nörvenich, Germany) featured in 2011 on a poster produced by the Nazi-Maoist group Socialismo Nazionale (Fig. 43), while Aufbruch der Kämpfer (The Warrior’s Departure, 1941, Arno Breker Museum, Nörvenich), was reproduced on Forza Nuova’s propaganda for the 2013 parliamentary elections (Fig. 44).Footnote 17

Conclusion

This paper began by quoting Martin Kemp’s definition of ‘iconic image’. I would argue that, at least in the domain of propaganda, his definition needs to be qualified. An icon need not be an image that is immediately recognisable by a large public across times and cultures. It may be a picture well known in a specific cultural context, which is chosen by a graphic artist belonging to a totally different one in order to exploit its proven visual impact, regardless of the intended public’s familiarity or lack of familiarity with it. The Pietà image in the Gandhi poster was unlikely to have been perceived as such by the majority of the Indian population; it must have been adopted solely in view of its strong emotional appeal. Moreover, certain images may be viewed as iconic only by those who are acquainted with the culture that generated them, and with which they feel in agreement. The drum-beating youth and the herculean warriors depicted in the posters referred to above are cases in point: they no doubt struck a chord with far-right activists, but the absence of any public outrage suggests that the references to Nazism completely escaped the vast majority of the population, as no doubt they were meant to do.

The examples discussed in this article attest to the sophisticated use many graphic artists make of iconic motifs when designing political artefacts. On account of their strength, these images are employed to bolster a political identity or promote such values as compassion and solidarity. They may also function as vehicles of censure and attack, and be appropriated by political organisations from their opponents for satirical ends, or to confuse and deceive the public. Lastly, some iconic motifs are used surreptitiously by radical groups to evoke ideological allegiances that would be deemed outright unlawful if stated overtly.

Credits

Fig. 23: Carol M. Highsmith Archive/Prints and Photographs Division/Library of Congress, Washington DC

Fig. 30: Archivio Storico, University of Bologna

Note on contributor

Luciano Cheles’s researches have focused on Renaissance iconography and its impact on contemporary culture, and on visual propaganda in Italy and France. Recent publications include L’Image recyclée, co-edited with G. Roque (BUPPA, 2013) and the essays ‘Piero e l’arte americana’ and ‘Piero e la cultura di massa’, both in the exhibition catalogue Piero della Francesca: indagine su un mito (Silvana, 2016). He has curated several exhibitions on Italian political and social graphics. Grafica Utile, first shown at the Design Museum, London, has toured several venues in Britain and France.

Figure 17 De Gasperi. Commemorative stamp, Republic of San Marino, 2011

Figure 18 ‘Giacomo Matteotti, kidnapped and murdered by the fascist secret police on 10 June 1924. On the second anniversary of this horrendous crime, honest Italians of all political affiliations mournfully and respectfully salute the great MARTYR’. Clandestine leaflet, 1926

Figure 19 Matteotti. PSI poster and postcard, 1974. Design by Ettore Vitale

Figure 20 Matteotti. Commemorative stamp, 1955

Figure 21 Saint Francis Xavier, holy image, date unknown

Figure 22 ‘Avanti popolo…Defend your vote! … and Benussi will triumph!’. Forza Italia billboard, local elections, Bolzano, 2005

Figure 23 John Steuart Curry, Justice of the Plains, 1938, mural painting. Department of Justice Building, Washington, DC

Figure 24 Iranian banknote, early 1980s

Figure 25 ‘Hands off marriage. Sort out the unemployment problem’. ‘All born from a man and a woman’. Anti-gay marriage poster, 2013

Figure 26 ‘We want jobs, not gay marriage’. Anti-gay marriage poster, 2013

Figure 27 ‘Freedom. Equality. Fraternity. No more, no less’. Pro-gay marriage poster, 2013

Figure 28 ‘Say YES to marriage for all’. Pro-gay marriage poster, 2013

Figure 29 ‘Italy in our hearts’. Azione Universitaria (AN) sticker, c. 2005

Figure 30 ‘I will not break, I will not bend’. Medal with the insignia of the Gruppi Universitari Fascisti, Florence, 1929

Figure 31 Logo of Azione Giovani (AN)

Figure 32 Celtic Cross

Figure 33 Swastika

Figure 34 ‘Join the action. On your feet among the ruins’. Azione Giovani recruitment poster, c. 2007

Figure 35 ‘It is not programmes that we must create, but men, new men’. Azione Giovani/AN sticker, c. 2004

Figure 36 ‘We are eagles, dreamers, rebels… We are free men’. Giovane Italia (PDL) recruitment advert, 2010

Figure 37 MSI membership card, 1972

Figure 38 Mussolini’s monogram, detail from the mosaic flooring at Rome’s Foro Italico sports complex (formerly Foro Mussolini), completed in 1938

Figure 39 ‘Rome. Formula Future. 2000 years in pole position’. Logo for the Formula Uno race that Rome intended to host, 2010

Figure 40 New logo for the city of Rome (eventually abandoned), 2012

Figure 41 ‘Honour to the comrades who have fallen’. Poster advertising a rally to commemorate the right-wing victims of the Acca Larentia terrorist attack, 2007

Figure 42 ‘The youth united in the Hitler Youth movement!’ Nazi poster, late 1930s

Figure 43 ‘Red anger, black rage. Red-brown pride’. Socialismo Nazionale poster, 2013

Figure 44 ‘Italy is in chaos. Power to Forza Nuova!’ Forza Nuova poster, parliamentary elections, 2013