‘… that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead’ (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 9)

The photographic lives and deaths of Moro and Pasolini

One of the key ways in which Pier Paolo Pasolini and Aldo Moro are remembered in Italian culture is through photography. Photographs were infamously essential to the story of Moro’s 1978 kidnapping and murder by the Red Brigades and its many retellings. These pictures – particularly the black and white newspaper reproductions of the polaroids taken by the kidnappers to show they had Moro alive, published on 19 March and 21 April 1978, and the news photographs of his dead body in the boot of the Renault 4 in via Caetani on 9 May 1978 – are deeply embedded in Italians’ historical memory not only of the ‘affaire Moro,’ as Leonardo Sciascia called it, but of the whole period of political violence in Italy in the 1970s.Footnote 1 Writing in 2008, Marco Belpoliti noted that the ‘terrible photo of his corpse in the Renault 4’ was ‘one of the most-seen photos of the last thirty years’ (2008, 27).Footnote 2 The photographs of the discovery of Moro’s body are iconic in that they have become ‘images that symbolise and identify, unequivocally, [a] significant moment ... in the season of armed political struggle in Italy in the 1970s’ (Mignemi Reference Mignemi2003, 89). If, as Alan O’Leary argues, Moro’s death has come to stand as a metonym for all ‘the other deaths of the anni di piombo’ (Reference O’Leary2012, 155), then it can be argued that the iconic power of these photographs both depends upon and helped shaped that metonymic status.

Ilenia Imperi writes that ‘it is significant and at the same time surprising how much even at the time there was already a clear perception of the “doubleness” of the events connected to the Moro affair, of their being “facts” and at the same time “messages”’(2015, 834). But it is perhaps not so surprising that Italian commentators responded immediately to the spectacular and mediatic aspects of the Moro kidnapping and murder.Footnote 3 By the late 1970s the theoretical engagement with photography and other forms of mass media that had been developing in Italy since the 1960s had built up into a significant body of work, as evidenced by the historical, sociological and semiological writings of authors such as Giulio Bollati, Franco Ferrarotti and Umberto Eco, to name a few.Footnote 4 Italian thinking about photography and the mass media in general were informed also by international debates and by the work of thinkers like Roland Barthes, Daniel Boorstin, Guy Debord and Marshall McLuhan, not to mention Pasolini’s own writings on what he saw as the consumer ‘inferno’ of Italy in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 5

The photographic record of Pasolini’s last weeks and death has received less critical attention, but, like those of Moro’s corpse in the Renault 4, the images of the poet’s battered body lying in a dirt field near the seaplane base at Ostia on the morning of 2 November 1975 have entered into Italians’ collective memory of the 1970s. Even when not reproduced alongside images of Pasolini during his life, the photographs of his violently murdered body haunt the visual record of his life. As Adriano Sofri (whose own life was profoundly marked by the violence of that period) wrote in an article published in 2000, ‘it is photographs of Pasolini, in this past quarter century, that have been his most common commemoration’ (Sofri Reference Sofri2000). Robert Gordon describes how Pasolini’s murder ‘was immediately interpreted as a highly symbolic event, read and reread in a symptomatically excessive and overdetermined manner’ (Reference Gordon2007, 153). While in the immediate aftermath of Pasolini’s death, little emphasis was given to the context of ‘contemporary political (and criminal) violence of the “years of lead”’ (Gordon Reference Gordon2007, 156), by 1978 Leonardo Sciascia would describe Pasolini’s murder as a ‘prefigurazione dell’affaire Moro’ (Sciascia Reference Sciascia2002).Footnote 6 Like Moro’s, Pasolini’s murder is one of the ‘traumatic events that are never really overcome’ and are ‘revisited in different guises as though through a Freudian repetition compulsion’ (Lombardi Reference Lombardi2007, 398). Pierpaolo Antonello notes that the deaths of Pasolini and Moro are ‘two of the most symbolically charged murders of post-war Italian history’, which became ‘critical turning points in the collective understanding of the shortcomings of radical political violence’ (2009, 30). In both cases, photography documented the horrific effects of such violence and was itself accused of enacting a cruel post-mortem attack on the image of the dead men that helped enshrine both as sacrificial victims of a period of violent political crisis.Footnote 7

Photography, celebrity and violence after the economic boom

The role photography has played in the compulsive return to the trauma of those years is partly a result of key shifts in uses and understandings of photography in Italy in the decades following the Second World War. The Italian economic boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s introduced new forms of photography onto the Italian cultural scene, dramatically altering photographic practices and understandings of the medium.Footnote 8 Two seemingly unrelated forms of photography of the human body experienced a boom during these years and have continued to flourish: paparazzi photographs of the famous caught unawares and graphic images of victims of violence. A symptom and product of consumer modernity, the new photographies expanded the boundaries of what was considered photographable while enforcing new norms of visibility and accepted visual identities. Public figures of all varieties found themselves in a symbiotic relationship with forms of image production based on creating and feeding a consumer demand for images of celebrity, while greater economic prosperity meant ordinary Italians increasingly used photography to emulate this exposure, posing as the stars of their own lives. Fame also arrived through violent death, with notorious cases such as the death of Wilma Montesi in 1953 making such victims household names. The potent mixture of a newly invasive photography, celebrity and violence created an unprecedented appetite for forms of photographic exposure as a product for sale and consumption.

Italy’s public intellectuals and politicians were not exempt from this visibility, as mass media images of Pasolini and Aldo Moro in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrate. A hugely controversial figure and a director often in the spotlight alongside film celebrities, Pasolini was acutely aware of how public figures were co-opted into the consumer logic of the society of the spectacle. As he wrote, ‘[i]t is a kind of game, whose rules are accepted by both sides: on the one side the exploiters, producers, publishers, directors of bourgeois magazines, whoever they are – on the other the exploited, that is, the person who had the misfortune to be successful’ (Reference Pasolini1999, 911). Gian Maria Annovi notes that Pasolini’s ‘apparent resistance to accepting his new status as icon of the mass imagination is also part of the construction of a public persona, that of an author who is the unwitting victim of the media and of his own success’ (Reference Annovi2016, 215).

Yet even before entering the image-conscious world of cinema, Pasolini had long been the subject of invasive photographic practices. Portraits made with his permission depicted him as an intellectual, gazing intently into the camera or deep in thought, but as John Di Stefano argues, mass media representations ‘lynched Pasolini over and over’, portraying him ‘as a subversive, a troublemaker, a pervert, a corrupter, a homosexual’, rather than as an artist and intellectual, in a ‘continuous blemishing of his public image [that] made the mere mention of his name synonymous with scandal, difference and marginality’ (1997, 19). Typical of the sort of image of Pasolini promulgated by right-wing dailies like Il Tempo and illustrated magazines such as Il Borghese over a period of many years is the photograph on the cover of the scandal weekly Lo Specchio (edited by former fascist Giorgio Nelson Page) from 23 September 1962 (figure 1). It shows Pasolini about to punch a neofascist youth, who had shouted abuse at him at the Roman premiere of Mamma Roma. The immediacy, crowded space and cut-off figures at the edge of the image recall paparazzi shots depicting celebrities in moments of rage or macho posturing. But as Pasolini later wrote, ‘the newspapers that reported the episode switched it around (illustrating it with misleading photographs) so that it looked like I was the one beaten up’ (Reference Pasolini1977, xi). The Lo Specchio headline ‘Schiaffoni per Pasolini’ (Hard Slaps for Pasolini) and the title ‘Hanno applaudito Mamma Roma sulla faccia del regista’ (they applauded Mamma Roma on the director’s face) deliberately tie the picture to well-established nationalist-conservative media depictions of Pasolini as effete and/or morally degenerate.Footnote 9

Figure 1 Cover photograph from Lo Specchio, 23 September, 1962.

In contrast, Moro’s public photographic identity largely conformed to the institutional identity of refined, cerebral statesman presented in his formal portraits, which show him in poses of thoughtful contemplation or concentration. Even in less formal images he is elegantly clad in suit and tie, punctiliously carrying out his duties and often paired with other politicians, underscoring his role as a power broker and negotiator.Footnote 10 Although much less exposed than Pasolini, the intense media scrutiny to which Moro was nevertheless subject is encapsulated in the famous photograph from 28 June 1977 of him shaking hands with Enrico Berlinguer, co-author of the ‘historic compromise’ that sought to bring the Italian Communist Party into a democratic alliance with the Christian Democrats and that was destroyed with Moro’s kidnap and murder (figure 2). Surrounded by photographers, with the boom of a TV microphone hovering to the left of the image, Moro and Berlinguer shake hands on an agreement that is both historic and mediatic. The symbolic significance of the handshake is magnified by the presence of the cameras, even as it is absorbed into a continuum of photographic flashes that indiscriminately offer up movie stars, murder victims and political figures as a spectacle for consumption.

Figure 2 Handshake between Enrico Berlinguer and Aldo Moro. Rome, 28 June, 1977.

Photographic exposure

As a controversial public intellectual and a high-profile politician, Pasolini and Moro were regularly photographed during their lives and continue to be remembered through a wide range of public photographs. But both were also photographically laid bare – literally and metaphorically – in dramatic ways just prior to their deaths. In Pasolini’s case, this occurred through the series of nude photographs of himself he had Dino Pedriali take at the poet’s house in Chia a month before his death (Pedriali Reference Pedriali2011). They were designed to look as though taken by a paparazzo-like hidden observer whose gaze invades the private space where the poet reads or walks about. In their aesthetic full-frontal display of the naked body of Italy’s most controversial openly homosexual artist, however, they deliberately overturn the marketability that is the raison d’être of the paparazzo shot. They show Pasolini’s awareness of photography’s implication in consumer culture and his interest in creating a ‘scandalous’ photographic identity not readily assimilated into that culture (Hill Reference Hill2014, 237–241). They are also a deliberate visual riposte to the ‘degenerate’ Pasolini most often portrayed in the media over the previous twenty years. Pedriali’s beautiful and carefully constructed photographs can be read as a forceful rejection of ‘the notion that [Pasolini’s] (gay) body is separable from his intellect, or that the (gay) body perverts the mind of an otherwise brilliant poet and filmmaker’ (Di Stefano Reference Di Stefano1997, 22).Footnote 11 They are a deliberate assertion of a self-constructed identity that resists the ‘disciplining of the subject’ (Lury Reference Lury1998, 77) enacted by what Alan Sekula characterises as forms of photography designed ‘to establish and delimit the terrain of the other, to define both the generalized look – the typology – and the contingent instance of deviance and social pathology’ (Sekula Reference Sekula1989, 345).

In violent contrast, Moro is laid bare to the camera not in the service of undermining the conventions and misrepresentations of commercial or institutional photography, but rather through their conscious use for propagandistic ends. Armando Massarenti notes that post-war politicians like Moro ‘after the Mussolinian overdose disliked showing themselves in public or being photographed’ (Reference Massarenti2008, 34).Footnote 12 Indeed, as discussed earlier, Moro’s public image was one that emphasised his political role and responsibilities (Barzaghi 854). The Red Brigades therefore used the polaroids of Moro not only to demonstrate that he was still alive, but also as a kind of ecce homo that displays him exposed to an intentionally humiliating photographic gaze. The polaroids embody the photographic experience ‘as a decisive, ready-for-consumption, violent (hence speechless) moment’ (Hill and Minghelli Reference Hill and Minghelli2014, 20) that silences the persuasive orator and political strategist and reduces him to ‘a weak creature stripped by the terrorists of his “royal” clothes’, (Uva Reference Uva2014, 247). For Belpoliti, the Moro polaroids take on the role of ‘an advertising photograph’ whose aim is to win supporters for the Red Brigades (2008, 6). They evidence photography’s status as a consumer product in post-war Italian society even in such an unexpected context: the staged event and the image taken without its subject’s consent brought to their most brutal extreme.

Iconic images, multiple images

The image of a dishevelled Aldo Moro beneath the Red Brigade star is often recalled as the iconic image that comes to mind in relation to that troubled period in Italy’s history. An icon is by its nature singular and iconic photographs are generally discussed as single images that symbolise a particular historical event, movement or period.Footnote 13 A polaroid might seem to be a perfect example of such a singular image, since, as Christian Uva points out, it has ‘a particularly marked indexical value’ because of its uniqueness and immediate usability (2014, 259). Like the daguerreotype, each polaroid is a unique image whose production requires that it be physically in the presence of its subject, although in contrast it appears almost instantaneously, prefiguring the digital photograph. It could thus be said to embody Susan Sontag’s argument that every photograph is ‘a trace, something directly stencilled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask’ (1979, 154). But the difference between the photograph and the death mask (and the polaroid) lies in the former’s infinite reproducibility and thus in the range and impact of its distribution, within the logic and economy of consumer culture and image production. While iconic photographs are often refered to in the singular, in fact no photograph can become iconic without being reproduced, so like all polaroids, those of Moro could not become iconic in their original, unique, and full-colour form. Only when they entered into circulation as black-and-white newspaper reproductions could they begin to achieve iconic status.Footnote 14

A further issue that arises in considering Moro’s Red Brigades image as singularly iconic is that, as noted above, there are actually two of them (figures 3 and 4).Footnote 15 Furthermore, the photographs that have come to represent not only the murders of Pasolini and Moro but also the whole cultural and historical context of criminal and political violence in the 1970s are also multiple. Multiple in the sense of being almost obsessively reproduced in illustration of the many historical and cultural rewritings of the murders, but also in terms of the number of photographs that were made and distributed. The Red Brigades circulated two polaroids of Moro, and two photographers (Rolando Fava and Gianni Giansanti) recorded the discovery of his body in multiple shots. Pedriali took multiple photographs of Pasolini shortly before his death and the police took photographs of Pasolini’s dead body from multiple angles. Multiple images of both men’s autopsies found their way into the press.

Figure 3 Newsprint photograph from the Red Brigade Polaroid of Aldo Moro published on 18 March 1978.

Figure 4 Newsprint photograph from the Red Brigade Polaroid of Aldo Moro published on 21 April 1978.

In Italy, all these images are inevitably read through the cultural and visual memory of the two men’s murders. Layered on top of this kaleidoscope of photographs like a ghostly double image are those of a bloodied body stretched out on a dusty patch of earth (figure 5) and another awkwardly curled into the boot of a car (figure 6). These photographs haunt the ceaseless production of books, articles and films on the deaths of the poet and the politician and are reproduced obsessively in one form or another as symbols of the many unresolved ‘misteri d’Italia’.Footnote 16 This obsessive repetition creates a different kind of iconic imagery, one that functions through a kind of metaphorical double exposure, overlaying the image of violent death onto every picture of the two men during their lives.

Figure 5 Rolando Fava, Aldo Moro’s body. Rome, 9 May 1978. © ANSA.

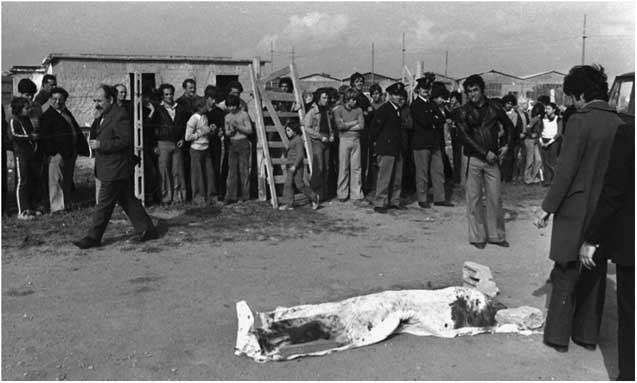

Figure 6 Pasolini’s body near the seaplane base at Ostia. 2 November 1975. © ANSA.

The double mortality of the photographic subject

By the time the photographs of the bodies of Pasolini and Moro entered circulation, the notion of the heightened mortality of the photographic subject was already a well-known trope of writings on photography, both within Italy and beyond. As early as 1945, André Bazin argued in ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’ that photography is the perfect expression of the ‘mummy complex’ that unites the figurative arts in attempting to create an illusory victory over death. It is a partial and distorting victory, however, since to preserve life photography ‘embalms time, rescuing it simply from its proper corruption’ (Reference Bazin1980, 242). Writing in Italy in 1949 in a similar but grimly satirical vein, Leo Longanesi made the claim that there was no great difference between photographs of the living and the dead, since ‘flesh … in photography, is always flesh by weight, butchered’ (Reference Longanesi1988, 30). The notion of photography as a kind of killing returns again and again in writing on the medium.

In the two most famous and influential meditations on photography to emerge from the 1970s, Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida and Susan Sontag’s On Photography (written between 1973 and 1977 and first published two years after Pasolini’s murder and a year before Moro’s), the essence of photography’s connection to death lies in the apparent proof it offers of a past existence, and thus that it is past. At the moment the photograph is taken, the photographic subject becomes a lifeless object. Photography thus creates an ‘image which produces Death while trying to preserve life’ (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 92). In this sense, wrote Sontag, ‘[a]ll photographs are memento mori,’ since ‘[t]o take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’ (Sontag Reference Sontag1979, 15). This slicing and freezing of moments of time like anatomical samples enables photography to function as ‘the inventory of mortality’. As such, ‘[p]hotographs state the innocence, the vulnerability of lives heading toward their own destruction, and this link between photography and death haunts all photographs of people’ (1979, 70). For Barthes, this haunting effect becomes even more painfully apparent when the viewer knows the subject ‘is dead and … is going to die’ as he writes of Alexander Gardner’s 1865 portrait of Lewis Payne awaiting execution (1981, 96). In photographs like Gardner’s, the viewer is confronted with ‘an anterior future of which death is the stake’ (Barthes Reference Barthes1981, 96). As Uva notes, this is precisely the ‘anterior future’ embodied in the Red Brigades polaroids of Moro, which presage the death that awaits the politician even as their immediate function was to demonstrate his continued existence (2014 244). While Pedriali’s photographs of Pasolini lack the immediacy and explicit violence of the polaroids of Moro, their deliberate exposure of the artist’s body to an unknown gaze nevertheless implies a threat (Hill Reference Hill2014, 238–239). In both cases, the men photographed share an anterior future of which not just death but brutal murder is the stake.

Doubly dead: the photographed cadaver

What are the implications of Bazin’s embalming, Sontag’s slicing and freezing, or Barthes’ anterior future for photographs that show death itself, in the form of dead bodies, rather than symbolising it through stilling the living? As Sontag wrote in her last book on photography, the medium has literally ‘kept company with death’ since its invention (Reference Sontag2003, 24). One of photography’s first uses was recording the image of the dead as a memento for the living, as in the vast body of nineteenth-century photographs of dead children and other family members posed as though sleeping (Orlando Reference Orlando2013). While the earliest of these post-mortem photographs were dignified, cherished images of departed family members or leaders, artfully arranged and surrounded by the accoutrements of mourning and preserved in the altar-like setting of the living room mantelpiece, the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the widespread entry into the public domain of brutally frank photographs of the dead, especially in the context of photography of war and its aftermath.Footnote 17 Photography maintained its status as a technology of mourning, but it was also a technology of repression, as the photographic iconography of dead bandits in the South of Italy, Cesare Lombroso’s embalmed and photographed heads, and the burgeoning role of criminal identity photography and crime scene photography all attest. Since the Second World War in particular, media images of death and destruction, for all their ubiquity, have provoked and continue to provoke widespread debate about the rights and wrongs of making and looking at photographs of the dead.Footnote 18

In contrast to the photographs of the dead taken before death, photographs which show dead bodies as unequivocally and violently dead (rather than illusionistically ‘sleeping’) disturb what Christian Metz called photography’s ‘compromise between conservation and death,’ since what they conserve is a literal rather than a metaphorical image of death (Reference Metz2003, 141). They brutally reveal what is repressed in photographs of the living, which, like fetishes, mask absence with the illusion of presence, enabling viewers to avert their eyes from what has been cut off. The photograph selected for a tombstone or a mantelpiece provides an image of the dead as the living wish to remember them, or believe they would have wished to be remembered, preserving an embalmed image of them in life. But photographs of corpses that violate the convention of ‘death as sleep’ make present the brutal and unspeakable finality of death, no longer hidden or disguised. Barthes’ ‘strange tense of the photograph’ (the impending catastrophe that has already happened) resolves itself into a simple past – that of a life – inextricably coupled with a simple present – the fixed condition of death.

This unrelentingly present death means that while photographs of the dead when alive may operate as part of what Freud called ‘the work of mourning’, photographs of their abused bodies violently interrupt that work. Images of the dead portrayed without disguise as dead haunt the living, since they recall the ancient horror of the unburied dead. For Freud, the belief in ghosts is tightly bound up with the inability to separate oneself from the recently dead, evidence that ‘[m]ourning has a very distinct psychic task to perform, namely, to detach the memories and expectations of the survivors from the dead’ (Reference Freud2009, 87). In the cases of Pasolini and Moro, the continuous and almost obsessive presence of the photographic images of the two men’s violently murdered corpses in Italian history, media, literature and film about the 1970s is both symptom and cause of the impossibility of separating collective ‘memories and expectations’ from the symbolic power of those two abused and abject bodies.Footnote 19

The spectacle of death

Figures 5 and 6 show the two most widely reproduced photographs of the bodies of Moro and Pasolini. Rolando Fava, a professional photographer, took the photograph of Moro’s body, while that of Pasolini’s was the work of an anonymous police photographer. But any differences in the quality of the photographs as photographs aside, the two images reflect the spectacular nature of the discovery of both bodies. Furthermore, the iconographical differences between the two pictures are representative of the differences in how the two deaths were treated and remembered.

Fava’s photograph of Moro’s body in the back of the Renault 4 was the photograph selected by the greatest number of Italian newspapers on 10 May 1978 to accompany the headlines announcing the murder (figure 5). La Repubblica, Corriere della Sera and La Stampa all used the image, cropped to varying degrees, on their front pages, as did numerous other national and international papers. Shot from slightly above, it shows Moro’s body surrounded by men in uniform or in jackets and ties, all but three gazing towards the body. In the uncropped version of the image reproduced here, the agitated gestures of the crowd recall the imagery and composition of paintings of the deposition of Christ. However, whereas in most depositions mourners touch, lift or support the body of Christ, in Fava’s picture the onlookers stand back a little from the car as though in horror or shock, the body isolated from them. The boot of the Renault 4 yawns like a cavernous mouth, and the eye is drawn to Moro’s white right hand against the dark fabric of his jacket at the absolute centre of the image (a Barthesian punctum, as many commentators have noted) and his face, twisted at an unnatural angle. In their separation from the body but concentrated attention towards the dark square of the Renault’s boot, the onlookers seem almost as though they are gazing at another polaroid, composed and arranged by the Red Brigades for maximum visual impact, ready to be re-photographed and reproduced. Isolated in death as he was in the last 54 days of his life, Moro’s body lies elevated as though on an altar towards which the crowd gazes.

Figure 6 shows the image that appeared on the cover of Il Corriere della Sera (for which Pasolini had written) on 3 November 1975, the most widely reprinted photograph of Pasolini’s body. While Moro’s body is the literal and figurative centre of attention in Fava’s picture, Pasolini’s body is covered by a white but gruesomely bloodied sheet held down with pieces of rubble and occupies the lowest point of the image. It is regarded with seeming indifference or merely morbid curiosity by the onlookers in the photograph, many of whom gaze off in other directions. One of the police investigators (in other shots shown with a uniformed police officer, smiling as he crouches over the body) smokes a cigarette, while another walks by seemingly oblivious to the grisly sight to his left. Apart from two other officials and two uniformed police, the rest of the onlookers are informally dressed and mostly male. The casualness of the crowd recalls the chilling photographs of white crowds gathered below the bodies of lynched black men in the American South in the first decades of the twentieth century. This visual link lends itself to the long-standing and on-going current of interpretations of Pasolini’s death discussed above that sees it as a literal or figurative lynching that continued after his death through the circulation of multiple much more graphic images of his corpse, as in the photograph printed in the conservative Bologna paper Il Resto del Carlino on 3 November 1975, which shows the white sheet pulled back to reveal the poet’s horrific injuries and crushed head: a literal effacement (figure 7).Footnote 20 The headlines make no mention of his intellectual and artistic work, instead summing up his life as a series of ‘legal charges, trials, scandals, insults’.

Figure 7 The front page of Il Resto del Carlino. Bologna, 3 November 1975.

Offensive images?

The shock of images of violently murdered bodies bears no relation to the elegiac nostalgia provoked by photographs of the dead taken during their lives. This is the shock Di Stefano expresses in describing the gruesomeness of the images of Pasolini’s body and what he sees as the insensitivity of the police and press who made them available (23), the shock Bellezza articulates when he describes the ‘obscenity’ of the photographs of Pasolini’s body on the autopsy table, ‘nude, exposed, with all the macabre wounds of his “sacred” martyrdom exhibited’ (Reference Bellezza1981, 50). It is the shock Mario Luzi expresses in the poem inspired by the photograph of Moro’s body ‘acciambellato in quella sconcia stiva’ (‘curled up in that indecent hold’), in which the ‘capo di cinque governi / punto fisso o stratega di almeno dieci altri, / la mente fina, il maestro / sottile / di metodica pazienza’ (‘head of five governments, fixed point or strategist of at least ten others, the fine mind, the subtle master of methodical patience’) is reduced to an ‘abbiosciato / sacco di già oscura carne / fuori da ogni possibile rispondenza / col suo passato’ (‘slumped bag of already darkened meat / outside of any possible connection with his past’) (Reference Luzi1998, 531). The poem’s last line, ‘la superinseguita gibigianna’ (‘the much-pursued flash’) that is too brief to provide understanding, suggests a fleeting illumination, but also points to the illusion of understanding that photographs can supply: iconic images appear to sum up a person, event or historic moment, even as they alter, fix and obscure meaning. The suggestion is that like death itself, the photograph transforms a rich and complex identity into so much meat.

In the 1949 article mentioned above, Longanesi expressed precisely this idea, arguing that photography is a kind of visual slaughterhouse, and thus:

The cadaver is its preferred theme; the murder victim is its true still life. The beautiful in photography found its realm in violent death. And we, too, have ended up getting used to seeing cadavers, to admiring their tragic positions, and uncovering with morbid curiosity their grimaces and sneers. (1988, 29)

Longanesi wrote in a post-war context of ‘shared visual horrors’, as Robert Gordon puts it, that saw publication of numerous shocking photographs of violent death and disfigurement, including the devastating photographic evidence of the unthinkable scale of the Nazis’ genocidal destruction (Reference Gordon2012, 45). These shared horrors brought new urgency to a question that would become even more pressing culturally and legislatively in the decades to come: at what point is the value of graphic images of death as a call to action or as journalistic, historical, scientific, or juridical evidence superseded by their potential to descend into what Geoffrey Gorer called ‘the pornography of death’ (Reference Gorer1955)?

In Italy, article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech and information and forbids censorship, nevertheless prohibits ‘[p]ublications, performances, and other exhibits offensive to public morality’.Footnote 21 Article 15 of law 47/1948 makes punishable by between three months to three years of imprisonment the publication of ‘printed materials that describe or illustrate, with disturbing or horrifying details, real or imaginary events, in such a way as to be able to disturb the common sense of morality or family order or to cause the spread of suicide or crimes’ (Ordine dei Giornalisti 2016). Autopsy photographs continue to be one of the most controversial and taboo forms of photography to which this legal framework has been applied and the arguments for showing them remain contentious.Footnote 22

In April 1979, the then director of the weekly L’Europeo, Giovanni Valentini, published the autopsy photographs of Moro’s corpse, setting off a firestorm of scandalised commentary. He was sanctioned by the Order of Journalists, which found the photographs to be ‘disturbing’ under the terms of article 15 of law 47/1948, and saw their publication as deeply disrespectful towards the dead man and his family. Yet in February of the same year, when the photographs of Pasolini’s body on the autopsy table were published in issue 6 of L’Espresso, no such sanctions were imposed. Bellezza later described the publication of these photographs as a ‘second killing’ perpetrated against a defenceless victim, explicitly comparing the aftermath of their publication with that of the post-mortem photographs of Moro just a few months later (Reference Bellezza1981, 50). For other commentators, however, both represent a legitimate use of photography. Stefano Rodotà, himself a politician and eminent jurist, has argued that the Moro case

was of such public significance that limits on publication could not be justified. For Pasolini’s body, legitimacy of publication was analogous to the more recent case of Stefano Cucchi: the photograph of the body made it doubtful that just one person could have killed the poet (quoted in Panza Reference Panza2009, 21).

Perhaps most interesting is the apparent inconsistency with which the law was applied, while its application matched the ways in which the media tended to portray the two men during their lives. This in turn is one of the factors that have continued to affect the different ways in which the murders and their photographic record are remembered. The photographs of the bodies of Pasolini and Moro as they were discovered occupy a grey zone of visibility and reproducibility that challenges the viewer to consider the ideological implications of ‘the common sense of morality or family order’ that the photographs may or may not disturb.

Haunting images

The haunting and harrowing photographs of Pasolini and of Aldo Moro, alive and dead, reflect a broader metaphorical haunting that is now a trope of much critical writing on the two men. O’Leary notes that ‘Moro appears as the ambivalently admired and resented totemic figure who refuses to stay dead and continues to haunt the living’ (2009, 2008, 53). More recently he described how ‘[t]he notion of “haunting” has become a commonplace in writing about the figure of Aldo Moro’ (2012, 156). The same applies to much commentary on Pasolini’s life and death. Twenty years after Pasolini’s murder, Enzo Golino commented on the difficulty of separating the work of that ‘cumbersome ghost’ from his myth (Golino Reference Golino1995, 84:18).Footnote 23 The flood of books published in 2015 on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the writer’s death suggests that this haunting and its attendant difficulties are far from over. In the words of Stefania Benini, ‘Pasolini troubles Italians with his unassimilable body-corpse: a tragic reminder of a nation born out of the Resistance and deeply wounded by the state terrorism known as the “strategy of tension”’ (Reference Benini2015, 16). Comparing the two men directly, Marco Belpoliti notes that ‘[t]he cumbersome body of Pier Paolo Pasolini is still symbolically unburied, like that of Aldo Moro, two illustrious and in many ways mysterious corpses, around which politicians, intellectuals, investigators, critics, writers and poets continue to bustle’ (Reference Belpoliti2010b). The photographs of Pasolini and Moro discussed here highlight the most problematic aspects of how iconic images of the illustrious dead enter into circulation and interact with post-mortem constructions of their historical identities.

Amidst all this bustling, who or what do the photographs of Pasolini and Moro, living and dead, identify? One answer is that they identify the fissures and fault lines in Italian collective memories of the violence of the 1970s and the radical transformations of a society. All these images are inserted into historical narratives that reflect long-standing ‘divided memories’ of the period (Foot Reference Foot2009) and the complex afterlife of two of its most emblematic figures. They also identify profound shifts in what could be made visible in the Italy in which they were produced and in which they have continued to circulate. The post-mortem photographs of Pasolini and Moro may be read as a deliberate attempt to annul a specific, inconvenient identity, a prurient betrayal of the constitutionally guaranteed right to the dignity of the individual, or as a refusal to bury evidence that might reveal hidden truths. These multiple meanings are perhaps the most significant way in which these photographs function as iconic images of their time.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the two anonymous peer reviewers of this article for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Notes on contributor

Sarah (Sally) Patricia Hill is Senior Lecturer in Italian and Head of the School of Languages and Cultures at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Her work focuses on intersections among Italian literature, cinema and visual culture, with a particular interest in photography and film. She is the co-editor (with Giuliana Minghelli) of Stillness in Motion: Italy, Photography, and the Meanings of Modernity (University of Toronto Press, 2014) and is currently working on representations of disability in Italian cinema.