Introduction: Italy's troubled colonial memory

In July 1960, the ten-year Italian trusteeship of Somalia (Amministrazione Fiduciaria Italiana della Somalia – AFIS) ended, putting an end to Italy's formal presence in the now former colony. Ten years later, the last remaining Italian settlers were forcibly expelled from Gaddafi's Libya. Such episodes indicate the protracted span and complex results of Italy's decolonisation. Yet, these anniversaries have become even more significant today, in light of the wave of protests against the material as well as cultural traces of the colonial period, which highlight the problematic and partially unacknowledged presence of those legacies in Italian society. Historiography agrees upon the fact that the peculiar configuration of Italian decolonisation inhibited an overarching assessment of the previous colonial period (Morone Reference Morone2019; Deplano and Pes Reference Deplano and Pes2014; Baratieri Reference Baratieri2010; Triulzi Reference Triulzi2006). Nonetheless, this article contends that the loss of the colonies did not simply erase the memories of the most violent side of the Italian presence in Africa. Rather, political discourses and cultural practices evoked an uncritical and indulgent image of the Italians’ impact in Africa. This is particularly evident in certain footage produced by private companies indirectly supported by the Italian governments. Accordingly, this article is going to tackle a specific corpus of documents, which have been dealt with only partially in colonial and postcolonial film studies: newsreels and short documentaries about Italian decolonisation, indirectly sustained by the Italian government (Zinni Reference Zinni2016; Ottaviano Reference Ottaviano2010).Footnote 1 These films reflected the political and social changes Italy was experiencing, as well as a shifting balance between state propaganda and the officially independent perspectives through which the footage envisioned Italian and global postwar realities (Forgacs and Gundle Reference Forgacs and Gundle2007). This article will thus centre on the equivocal relationship of these short films with hegemonic actors (the government, but also industrial groups and foreign institutions) and on the reality of the former colonial space that this footage conveyed during the few minutes of screening.Footnote 2 The film's mediated gaze on the former colonial world therefore offers a valuable means to understand the puzzling articulation of Italian colonial memories.

The loss of the colonies in postwar Italy

On 5 May 1941, five years after the Fascist commander Mario Badoglio had seized the city, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia returned to Addis Ababa, escorted by the English troops (Asserate Reference Asserate2015; Del Boca Reference Del Boca1984). Allied troops had defeated Italy in Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea between February and May 1941. The British Military Administration (BMA) had seized control over Eritrea and Somalia and was awaiting the decision of the victors of the Second World War (USA, USSR, France, Great Britain) about the future rule of these regions. In Libya, the El-Alamein battle (November 1942) resulted in British forces taking control over the Mediterranean regions of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, while the desert region of Fezzan fell under the authority of France (Morone Reference Morone2019; Calchi Novati Reference Calchi Novati2011).

The end of the Italian empire of East Africa intersected with the most significant period of turmoil occurring in modern Italy, that is, the fall of Fascism and the national reconstruction following the Second World War. The interweaving of events like Fascism's collapse, Italy's military defeat and the consequent loss of colonies, the anti-Fascist formation of the new Italian political forces and the changing international situation might lead one to think that the brutal crimes that characterised the previous colonial period would have promptly been challenged. In spite of the genuine anti-Fascist ethos that inspired the Governi d'unità Nazionale (National Unity Cabinet), and notwithstanding the feeble international role of Italy, the new Italian governments requested that the colonies acquired before Fascism be returned to Italy (Pes Reference Pes2017; Borruso Reference Borruso2015). Between 1945 and 1947, Italy's diplomatic efforts aimed at regaining a form of direct control over Libya, Eritrea and Somalia, but the results fell far below expectations. On 10 February 1947, Italy signed the Treaty of Peace; Article 23 established that Italy had to renounce to its former colonies, though without defining the precise modalities of their decolonisation. Such practical decisions were devolved to the victorious powers, which failed, however, to reach an agreement. Due to the ensuing deadlock, in 1949 the Italian diplomatic strategy suddenly changed: Italy supported the immediate independence of Libya, Eritrea and Somalia, in this latter case after a transitory period of ten years (Morone Reference Morone2019; Pastorelli Reference Pastorelli2009). Eventually, Italy was appointed as trustee administrator of Somalia (1950–60). Italian decolonisation was further complicated by the fact that the African Office (Ministero dell'Africa italiana – MAI) wasn't disbanded until 1953, and that Italian communities continued to play a pivotal role in the economic and social life of the former colonies (Calchi Novati Reference Calchi Novati2011; Labanca Reference Labanca2002).

These political and diplomatic actions reflected the prolonged and incomplete nature of the Italian decolonial process insofar as, within that time span, the colonial past was neither completely erased, nor relegated to the political and diplomatic sphere (Deplano and Pes Reference Deplano and Pes2014; Ben-Ghiat and Fuller Reference Ben-Ghiat and Fuller2005). This is because the government's agenda as well as the destiny of those Italians who remained in the former colonies still found a place in public debates and in related cultural productions (Zaccaria Reference Zaccaria and Morone2019). The rhetoric concerning the claims for a return to Africa drew on the supposed benevolence of the Italian presence in the colonies as well as on the assumption that the formerly colonised population was willing to accept it. As a side effect, though, both the Italian governments and the pro-colonial milieu deliberately avoided questioning the most brutal sides of Italy's colonial past (Jedlowsky Reference Jedlowsky2011; Morone Reference Morone2010).

These political processes and mnemonic mechanisms became visually and aurally tangible on several occasions, whose significance is acknowledged by a substantial number of scholarly works (Zaccaria Reference Zaccaria and Morone2019; Deplano, Pes Reference Deplano and Pes2014; Baratieri Reference Baratieri2010; Andall and Duncan Reference Andall and Duncan2005). In this article, the choice to focus on newsreels and documentaries is motivated by two equally important factors. On the one hand, they were highly privileged tools to envision the new social and cultural configuration of postwar Italy, mostly centred on the values typical of the hegemonic forces that were governing the process of reconstruction (Sainati Reference Sainati2001). On the other hand, I argue the importance of closely investigating these films for their implicit assertion to offer a representation of this reality as truthfully as possible. The indexical relationship they aimed to establish with what happened in front of the camera made them instrumental in delivering political messages, whether directly or in more surreptitious ways (Bonifazio Reference Bonifazio2014).

Filming the end of the Italian empire

The dismantling of the state monopoly over non-fiction films, which had been inherited from the ventennio, was all but easy.Footnote 3 Postwar political and economic elites still conceived of those short films as powerful tools to address Italian society (Sainati Reference Sainati2001). The study of the films dealing specifically with Italian decolonisation offers a privileged vantage point from which to assess the passage from a Fascist, state-controlled industry to an officially private one, which nonetheless remained subtly directed by the Italian government. Royal Decree n. 678 (1945) solemnly proclaimed that ‘film production is free’; nevertheless, since 1947 Giulio Andreotti – the undersecretary of the newly established Central Office for Cinematography at the Prime Minister's Office – had been working on an institutional framework in which documentaries and newsreels produced by private companies were still supported by the government.Footnote 4 This framework, though formally repealing the Fascist monopolistic control over non-fiction films, de facto established that private companies needed the Central Office for Cinematography's authorisation to project their films in movie theatres. Moreover, laws n. 379 (1947) and n. 958 (1949) granted the possibility for documentaries and cine-news to obtain a subvention from 3 per cent up to 5 per cent of the tassa erariale, the global tax revenues of a film's distribution. As a result, any film shorter than 30 minutes and containing some realistic content could be supported by the state (Quaglietti Reference Quaglietti1980).

This twofold mechanism of control and funding was complemented by legal provisions regarding the obligatory ‘pairing’ initiative (abbinamento), which imposed the mandatory screening of a newsreel or a documentary prior to the feature film show, as happened during the ventennio. Accordingly, the audience had to put up with a newsreel and a documentary in addition to the movies they had paid for. This observation invites us to reflect on the circulation and reception of non-fiction films. The majority of scholars maintain that postwar non-fiction films were appreciated by the audience, because their style was more vibrant than previous Fascist footage. However, since propaganda films came to be regarded as outdated due to the spread of television in the late 1950s, the screening of political newsreels and documentaries began to be perceived as an unnecessary interruption (Argentieri Reference Argentieri and Taviani2008; Sainati Reference Sainati2001). Such a growing aversion to mandatory screening ultimately resulted in less favourable legislative support for non-fiction films (through Law n. 897, 1956). Nonetheless, between 1945 and 1956 the institutional setting allowed the state to indirectly control non-fiction film production while private companies gradually bowed to the government's needs in order to obtain protection and funding.

The vicissitudes that affected two documentaries about the claims over the former colonies (Lavoro Italiano in Africa and Giustizia per le colonie) epitomised this politically biased scenario. The former film was produced in 1947 by a private company (Generalcine), which sought the government's support to solve a small issue related to its diffusion.Footnote 5 It was subsequently used by the Foreign Office (MAE) to support the Italian claims over the colonies among Italian communities abroad.Footnote 6 The latter film was equally produced by a private company (CEN film), which requested and obtained state funds to finalise the footage on the condition that some improvements suggested by the MAI personnel would be adopted.Footnote 7

As far as the newsreel market is concerned, direct and indirect forms of government influence in film production created a rather peculiar scenario: despite the growing number of private companies that were desperate for state funding, only a few companies – like Industria Cortometraggi Milano (INCOM), Documento Film and Astra Cinematografica – thrived.Footnote 8 Further appraisal reveals that INCOM practically monopolised this oligopolistic configuration, because of its ideological affinity with the political and economic elites (Sainati Reference Sainati2001). For almost two decades, the Settimana INCOM obtained the majority of state prizes allocated for non-fiction productions, thus becoming the privileged tool through which the government conveyed ideas about Italy's renewed presence in Africa.Footnote 9

Questioning decolonial traumas: the Mogadishu massacre (1948)

Films about Italian decolonisation dealt with diverse topics: the Paris Peace Conference; the Italian communities still living in Ethiopia, Libya, Eritrea and Somalia; the new diplomatic relationship with Ethiopia; the Italian Trusteeship in Somalia. During this rather long period of about 15 years, the footage spread images of Italy's positive impact on the former colonies while carefully avoiding any public repentance for, and reconciliation with, colonial crimes. Such representations, on the one hand, assumed that former colonial subjects did not suffer any traumatic experiences during Italian rule; on the other hand, the films tried to somatise the long and intersecting collective traumas Italy was facing during the 1940s. Any disturbing consequences of that experience were meant to vanish in the images of the benevolent impact Italians had had on Africans, and in the representation of Italy's engagement in the future development of the former colonies.

This perspective opens up a more fluid recognition of the traumatic experience related to the loss of the colonies. By enlarging the perspective from a specific and event-based approach toward a collective and fluid process, composed of numerous events and practices, Italian decolonial trauma can be viewed as being delocalised in time and space, and not wholly ascribable within the syllogism between cause (i.e. loss of the colonies) and effect (i.e. ailment/colonial amnesia) (Visser Reference Visser2015; Craps Reference Craps2013). Italian decolonisation is a case in point to address a scattered yet repressed form of colonial trauma, since it was a protracted process, and a blurred one within the broader transition from Fascism to the Republic. However, despite the attempts to shape an untroubled colonial memory, there was an event in which the painful reality of decolonial struggles clearly surfaced: the massacre in Mogadishu, in 1948, when the capital was still being controlled by the BMA. On 11 January, following the arrival of members of the UN mission, two opposite rallies collided. The demonstration organised by the Somali Youth League (SYL), which was adamant about rejecting any involvement of Italy in the country's future, clashed with an unauthorised, pro-Italian parade supported by the Italian community. At the end of the riots, 52 Italians had been killed and 48 badly wounded, against 14 Somalis being killed and 43 wounded (Urbano and Varsori Reference Urbano and Varsori2019).

A number of Italian newsreels and documentaries have dealt with this event. Two Settimana INCOM films focused on the culprit of the massacre.Footnote 10 Newsreel 114 describes the SYL as a chauvinist movement that contrasted with the opinion of the majority of Somali people, who instead wanted Italy to stay in order to lead the transition toward independence. The film is divided into two parts, both characterised by an extremely gloomy atmosphere. The first scenes are shot in a church in Rome where a memorial service for the Italian victims is taking place. The camera pans across the church, where some important Italian politicians (De Gasperi, Corbellini, Togni) are praying for the victims, while the voice-over states that the same rite is taking place in Asmara and Mogadishu. This commentary suggests that three cities are still bonded by a spiritual union. The shrilling of an oboe suddenly dissolves the atmosphere of mourning and introduces a more vibrant section of the film, featuring shorter takes of the pro-Italian protesters in Mogadishu (Fig. 1). Such a dynamic cut proves that the entire Somali society wanted Italy to guide the process towards independence. Hence, the footage dismisses the stressful effects of decolonisation by exorcising the direct confrontation with the former subjects.

Figure 1. Still from the Settimana INCOM 114. ⓒ Archivio Storico Istituto Luce, Rome.

Another film that makes reference to the Mogadishu incident was aired in March 1948. It recounts the arrival of the ship Sparta in the harbour of Naples, transporting those who had escaped from Somalia following the massacre of 11 January back to Italy.Footnote 11 The atmosphere is even more solemn than that of the previous film. Camera movements are slow, and close-ups of the crying people on the boat convey their sense of helplessness while facing the return to Italy. Guido Notari's voice-over is deeply emotional, and it struggles to find the right words to describe that wretched situation. As soon as the focus shifts to Giuseppe Brusasca, the Italian undersecretary for Foreign Affairs who played a major role in managing the issues concerning the former colonies, the commentary and the images convey a slightly different feeling: the undersecretary announces that the boat people will stay in Italy only temporarily, because they will go back to their homes in Africa. Accordingly, this part of the footage argues that the traumatic events they experienced on 11 January 1948 could be overcome by returning to Somalia and resuming their ‘civilising’ work.

Although starting from different assumptions, these films share the determination to work through the trauma of losing the colonies by focusing on the suffering of the Italians, who would be deprived of their overseas territory and thus of the potential to realise their industriousness. African people, instead, are portrayed as eagerly accepting guidance by Italy in their development. Against this backdrop, the images of the Mogadishu massacre seem to describe a gloomy omen for both Africans and Italians. For the former, it represented the moment of chaos that would have anticipated the dreadful scenario engendered by the Italians’ departure. For the latter, it was the traumatic end that interrupted their work in Africa. The decolonial trauma seems to be disarticulated: the pain is provoked not so much by the riots, but by the indirect action of the international community, which satisfied neither the Italians nor the Africans, who wanted an Italian protectorate over the former colony.

The films about the Mogadishu incident are fascinating examples of colonial memories that must be understood against the background of a disturbing experience. However, the discursive and aesthetic strategies they refer to aimed at resolving this trauma, since Italy presented itself as a trustworthy power, which did not deserve the ultimate loss of its role in Africa. Against this backdrop, the footage contributed to configuring a specific form of memory, which might be defined as a-traumatic insofar as it camouflaged the loss of the colonies. This form of a-traumatic memory conceptually questions the amnesic removal of colonial discourses (Saadi-Nikro Reference Saadi-Nikro2014); these films are prime examples of the fact that, even if the empire no longer existed, its rhetoric still fed the representation of Italy's future projection in the now former colonial space. As such, rather than addressing a collective silence about that experience, the film representations ‘both elicit and elude recognition of how colonial histories matter and how colonial pasts become muffled or manifest’ (Stoler Reference Stoler2016, 122–73) during the end of the empire, and within the broader process of national rebuilding following the Second World War.

From amnesia to aphasia

The prolonged and delocalised trauma of Italian decolonisation only partially allows the paradigm of amnesia to tackle the issue of the country's troubled colonial memory (De Cesari Reference De Cesari2012; Andall, Burdett, Duncan Reference Andall, Burdett and Duncan2003). After 1945, the collective memory of Italian colonialism started to be characterised by a persistent and inescapable dichotomy: the simultaneous presence and absence of the colonial past, which was ‘concealed at some moments and revealed at others’, as part of an inconsistent ‘cartography of recollection’ able to build a certain public memory of that experience (Winter Reference Winter, Ben-Ze'ev, Ginio and Winter2010, 3–6). This contradiction is common to the majority of post-imperial metropolitan centres, which have made ‘colonial history alternately irretrievable and accessible, at once selectively available and out of reach’, according to diverse political and cultural stances (Bijl Reference Bijl2012).

The pivotal work of Ann Laura Stoler sheds a fascinating light on the composite mechanisms through which the contradictory memories of colonialism spread in the metropolitan centres. Following the research of psychologists who have studied the disruptions in the comprehension and production of language in oral and written forms, Stoler suggests that aphasia can address the ‘comprehension deficit’ of the post-colonial scenario, due to a partial knowledge loss concerning the colonial past (Stoler Reference Stoler2011; Reference Stoler2016). Against this backdrop, the indulgent and positive image of the Italians’ impact in Africa – which was crafted during and, most peculiarly, after the colonial presence – effectively inhibited the articulation of a serious debate about the most shameful sides of the colonial past. Accordingly, more than ‘forgetting’, aphasia emphasises that knowledge of the colonial past was not merely present or absent at a societal level. Rather, it was occluded, or blocked, ‘disabled and deadened to reflective life, shorn of the capacity to make connections’, as happens in any aphasic condition (Stoler Reference Stoler2016, 122–73).

Aphasia is directly linked to memorability, because the inability to articulate meaningful sentences may obstruct the production of a comprehensive discourse about the past. Hence, the language those films used, the very words they deployed and the ways in which the commentary intermingled with the images can be considered indicative of the active strategies through which the colonial past was reworked and exploited for the debate about postwar national qualities (Rothermund Reference Rothermund2015). The footage about Italian decolonisation was rarely filmed on the spot; the films were more often crafted by editing found footage, and by combining it with footage coming from commercial exchanges with foreign companies (Pallavicini Reference Pallavicini1962). The film scripts simply consisted of the text of the commentary, which was added extra-diegetically. Between 1946 and the late 1950s, INCOM film scripts were written by Giacomo Debenedetti, a left-wing intellectual who was supervised by other members of INCOM, namely its president, Sandro Pallavicini, and the chief editor, Domenico Paolella: the latter intervened in order to calibrate the sentences that Guido Notari's voice would pronounce in every cinema (Folli Reference Folli2020; Frandini Reference Frandini2001).Footnote 12 It is worth pointing out that Pallavicini, Paolella and Notari were involved in the previous Fascist propaganda system to varying degrees. In 1938, Pallavicini founded the INCOM company, whose main aim was to challenge the Istituto Luce's monopoly by creating a series of non-fiction films inspired by American footage, such as The March of Times. During the ventennio, Domenico Paolella – who became a famous director in the 1940s and the 1950s – called for Luce films to be more overtly attuned to the racial laws (Marrese Reference Marrese2014).Footnote 13 Moreover, the very voice that gave a strong propaganda ethos to Luce's footage – namely that of Guido Notari – also provided the commentary for subsequent INCOM films.

These biographical trajectories exemplify the quite remarkable continuity between Fascist and postwar films, which also pertains to the ways in which the films conveyed narratives and discourses about the ambiguous decolonial transition. In this respect, the spoken words and the scripts that inspired them deserve detailed attention insofar as they are the strongest components of non-fiction films. This is because the commentary is where ideological and discursive structures are located and a certain social meaning concerning the images is generated. The voice-over of the analysed footage employs different registers and roles, alternating the embodied authoritativeness of state power with a more familiar, sympathetic and ironic tone, which brings the commentary closer to the audience (Sainati Reference Sainati2000). This is clear, for instance, if we look at the Settimana INCOM 48, the first newsreel dealing with Ethiopia after the end of the Fascist empire.Footnote 14 The film is about a military parade held in Addis Ababa in 1947. In all likelihood, the footage comes from a foreign company, since the INCOM did not send any crews to Ethiopia in 1947 (Pallavicini Reference Pallavicini1962). The images of well-arranged troops are interspersed with low-angle medium shots of Haile Selassie. As a whole, the mise en scène gives dignity to the emperor's portrayal and to the Ethiopian forces, whereas any form of exoticism is absent.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, the extra-diegetic INCOM commentary and the soundtrack, featuring marimbas and tribal-like percussions, completely change the atmosphere that the images alone would have conveyed. In the first scene, when Haile Selassie gets out of his car, Notari's voice puts an emphasis on the presence of the cagnolino – a small dog, hardly visible in the images – that, according to the commentary, always accompanies the emperor (Fig. 2). In so doing, the voice defuses the emperor's dignity as reflected by the images alone, redirecting the audience's attention to the presence of the pet and away from the ceremonies of an independent country.

Figure 2. Still from the Settimana INCOM 48. ⓒ Archivio Storico Istituto Luce, Rome.

When the camera lingers on the military parade, the voice-over drawls significantly to describe some soldiers as they march, following the ‘passo dello struzzo addormentato’ (the sleeping ostrich step), which was allegedly invented by the Ethiopian generals, who were envious of the more martial goose step. The commentary then mocks the African soldiers, who would be better off doing parades than fighting, as happened ‘in recent wars’: the reference to the Ethiopian war of 1935–6 is obvious. What is noteworthy here is not so much the complete silence about Fascist crimes, which are obliquely evoked when commenting on the Ethiopians’ inability to fight, but the mockery of Ethiopian people, who are depicted as simply imitating Western models, but without succeeding. Such a botched mimicry does not undermine the hiatus separating white and black people and cultures. Rather, it reinforces the dominance of Western models in the African post-colonial context.

Although the Settimana INCOM 48 is rather short, it nonetheless reveals another extremely interesting aspect of the commentary: the use of what might be regarded as the sung motto of the Ethiopian war, Faccetta Nera. Written in 1935, this marching chant exalts the invasion of Ethiopia as the moment in which (male) Italian soldiers set the ‘little black faces’ free. Faccetta Nera was composed before the promulgation of the racial laws, which banned interracial unions; the song's allusion to the sexual conquest of the Ethiopian women did not please Mussolini, and the lyrics were changed accordingly (Pinkus Reference Pinkus1995). In spite of this, the original version remained more famous during and after the imperial period; since the 1950s, it has addressed a kind of nostalgia, especially in certain right-wing circles, by recalling the ‘good old days’ of a virile and predatory understanding of national ethos (O'Healy Reference O'Healy2009). Nevertheless, one of the first re-articulations of Faccetta Nera happened exactly in the film under discussion. Although the camera portrays a military parade, the voice-over says that the soldiers want to impress the ‘faccette nere occhieggianti tra il pubblico’ (‘ogling little black faces in the audience’); the word occhieggianti is meant to replicate the trope of African women as loose and tempting the white males. Yet, the sarcastic mockery with which the voice-over had previously described the Ethiopian soldiers now aims to portray them as incapable of properly satisfying the desires of the faccette nere. As a result, the ogling of Ethiopian females is very much addressed at the Italian audience. This representation of the former colonies relies on a discursive map whose coordinates oscillate between the use of irony, nostalgia, racism and exotic backwardness. These elements also feature in the Settimana INCOM 323, about a sporting event held in Addis Ababa.Footnote 16 The film's text (Fig. 3) hints at the contrast between the white clothes of the Ethiopians and their skin colour.Footnote 17 Next, they are epitomised as ‘negri’, who are doing exercises that are more similar to those the Italians had taught them in the past than to those typical of the so-called ‘paese delle arube’ (the country of arubas). Although the word negro/negri had a quite neutral meaning at the time (Faloppa Reference Faloppa2004), the words paese delle arube deserve further attention. Their exact meaning is unclear (Aruba is an island in the Netherlands Antilles), but they were used here so as to underline the backwardness and exoticism of Ethiopia.

Figure 3. Script of the Settimana INCOM 323, ASL, Rome

These two films (Settimana INCOM 48 and 323) contributed to making the memory of the controversial relationship between Italy and Ethiopia increasingly indefinable and irretrievable. Any form of metanoia, understood as the attitude that former imperial countries might have adopted by showing respect for the former colonised cultures and by admitting that the mission civilisatrice was a sign of usurpation, is avoided (Khaznadar Reference Khaznadar2012). In this context, the voice-over commentary inhibited the mnemonic process through which to critically recollect the previous Fascist presence in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, although silencing any direct references to Fascist crimes, the scripts still used the racist, deceitful and scornful vocabulary of Fascism, and consequently remained in an ‘active register’ (Stoler Reference Stoler2011).

A changing lexicon that reframes colonial discourses

A biased portrayal of the colonial period, and of its end, is blatant in films dealing with the government's attempts to gain a new influence in Somalia, Eritrea and Libya. Italy wanted to sustain a form of hegemonic presence in each of these countries, by advocating a long-lasting relationship which could be traced back until well before Fascist colonialism (Pes Reference Pes2017; Calchi Novati Reference Calchi Novati2011). One of the most interesting examples of such discourse features in the commentary of the Settimana INCOM 410.Footnote 18 The film, produced in 1950, is about the Italian troops getting ready to depart to Mogadishu for the beginning of the AFIS. The shots of well-arranged units are indeed reminiscent of older Fascist parade films. Nevertheless, as the transcription of the written commentary shows (Fig. 4), the INCOM management decided to erase the sentence ‘troops on parade: a cadenced step that will take them far’, as it could have been considered too evocative of previous imperial discourses.Footnote 19

Figure 4. Script of the Settimana INCOM 410, ASL, Rome

A few other sentences that indirectly recalled Fascist propaganda, in the second part of the script, were also omitted. The footage portrays Brusasca and De Gasperi standing on the dock along with a large crowd, while the soldiers are boarding the San Giorgio ship. Guido Notari's voice reports De Gasperi's words: ‘Yours is the mission of peace and civilisation’. Next, the prime minister makes clear that the ship – and Italy as a whole – does not seek new colonial ventures (‘non drizza la prora verso le avventure coloniali’) but is going to Somalia to show its moral values. In so doing, the film eliminates the colonial past from the representation of the new Italian presence in Africa, which is, instead, portrayed as instrumental in proving the political reliability of a nation that has left Fascism behind. This element is epitomised by the replacement of the word ambe, used in the original script. It spread in Italy between the end of the nineteenth and the middle of the twentieth century, with reference to the massive mountains and plateaus of Ethiopia where the most violent battles between Italian and Ethiopian armies took place, both in 1896 and in 1936 (Labanca Reference Labanca2015).Footnote 20 In all likelihood, the substitution of the word ambe with the more neutral altipiani (plateaus) represented an attempt to avoid any reference to these battles. The script puts much emphasis on the paradigm shift that inspired the new Italian presence in Africa. The former colonial domination is transfigured in the renewed ‘sense of democratic measure and international cooperation’. Thus, previous colonial discourses are latently re-articulated through the use of a more polished lexicon, which intermingles with emotional images (Fig. 5) that attempt to disguise a new political and economic conquest of Africa.

Figure 5. Still from the Settimana INCOM 410. ⓒ Archivio Storico Istituto Luce (Rome)

The film Ritorno in Africa. Primo aereo per la Somalia conveys an even more mystifying vocabulary concerning the beginning of the AFIS.Footnote 21 This newsreel is about the departure of the AFIS commissioner Mario Pompeo Gorini, along with other political as well as business delegates, from Ciampino airport in Rome. The narrative structure unfolds in the contraposition between dark shots of people boarding the plane for a night flight to Mogadishu and a commentary that, in contrast, exalts the new dawn of the Italian presence in Somalia. The film ends with Notari's voice solemnly uttering the following words: ‘the sun will rise during this journey, as an omen of our work’. Such a metaphor implies that the opaque period of Italian presence in Africa was the Fascist period, which seems dead and buried. Hence, the ‘excellent colonial administration’ mentioned in the script refers to an older and pre-Fascist phase, when the connection with Somalia was established.Footnote 22

Two films about the visit Brusasca paid to the Horn of Africa (1951) provide further examples of the extent to which film commentary disguised any critical readings of previous colonial activities.Footnote 23 Brusasca in Africa is about the first leg of the undersecretary's visit. As a whole, the film is organised in three quite distinct sections, dealing respectively with Brusasca's departure, the description of Asmara and Mogadishu as cities still connected with Italy, and the Mogadishu massacre. The commentary and the images follow this tripartite structure consistently. The first two parts feature a montage aiming to bring the audience into the ‘exotic atmosphere’ of Africa by alternating images of noisy markets, tribal dances and black people cheering the Italian delegates. Yet, at one point the voice-over says that ‘Asmara still speaks Italian’, and the camera instantly shifts to Italian bars, restaurants, a cinema and other buildings. The tone of the film becomes more emotional as soon as the voice-over mentions the brutal events of January 1948, with the commentary saying that Mogadishu remains an appendage of Italy because of the sacrifice of its sons, who died on that occasion. The original script (Fig. 6) and its corrections reveal the extent to which the process of collective memory-making was influenced by the government's new political agenda in the now former colonies.Footnote 24

Figure 6. Script of the Settimana INCOM 638, ASL, Rome

The omitted parts in the first paragraphs make the film's pace more vibrant, allowing for a perfect synchronisation between the visible and audible dimension of the footage. However, the strike-through in the sentence ‘this land's problem is drought’ could be interpreted slightly differently. This omitted part, more than acting as a mere stylistic refinement of the film's pace, in fact conceals a problem still present in Somalia. If the voice-over had admitted the lack of water, it would have discredited the rhetoric of the good Italian workers who solved the Africans’ problems, a rhetoric that both previous and coeval footage spread widely in order to justify the Italian presence after decolonisation.

The break (pausa) indicates the passage to the saddest part of the film. De Benedetti's text here evokes the Mogadishu massacre in order to reactivate the memory of this traumatic experience. This passage creates an emotional connection between the official voice of the government (which was simultaneously embodied by Brusasca and disembodied in the voice-over) and the common feeling of an audience that was inevitably forgetting the colonial topics (Labanca Reference Labanca2002; Del Boca Reference Del Boca1984). Moreover, the passionate response the film seeks to evoke among the audience epitomises the difficult effort to detach Eritrea and Somalia from the emotional map of Italian belongings that had characterised the previous representation of the empire (Ben-Ghiat Reference Ben-Ghiat2015; Mancosu Reference Mancosu, Cortini and Scarnati2020).

The aphasic disconnection between past, present and future

The medium-length documentary Torniamo in Etiopia con un messaggio di pace. Servizio speciale sulla missione dell'on. Brusasca in Africa is a case in point to observe the silencing of the uncomfortable sides of Italy's colonial past and the articulation of the new Italian presence in its former territories.Footnote 25 The first scenes offer a recollection of old colonial tropes, which are recast in order to describe the now independent countries. The camera, after portraying dusty roads with wide-angle framings, increasingly zooms in on some Somali people wearing ‘traditional’ clothes and playing handmade percussions and seashell horns; they are singing and playing music to express their supposed happiness at the arrival of Brusasca. Such visual tropes had been broadly applied in previous Fascist productions, especially in propaganda documentaries produced on the occasion of the Ethiopian war (Mancosu Reference Mancosu, Cortini and Scarnati2020). In all likelihood, a significant part of the Italians who saw the footage about the loss of Italy's colonies had watched films with similar images some years before. This evocative familiarity in terms of iconographic discourses is only partially undermined by the new commentary: the original script (Fig. 7), in fact, proves that a relevant part of the description of this exotic welcoming – ‘some of them are dancing, others are waving their spears to greet [Brusasca]’ – was subsequently removed.Footnote 26

Figure 7. Script of the Settimana INCOM 648 (folio 1), ASL, Rome

Such a choice may have been made with the aim of defusing the film's authoritative stance by letting the exotic images speak for themselves: in fact, exoticism clearly stands out, especially when the camera lingers on the details of Somali dresses and on the smiling faces of dancing girls. The rationale behind this choice is twofold: firstly, it gives the film a lighter touch, capable of attracting the audience's attention; secondly, it reactivates and reframes a sense of exotic backwardness by implying that Italy led the path toward the African country's modernisation ever since the previous colonial period.

Two handwritten comments are noteworthy insofar as they put additional emphasis on the future independence of Somalia (‘making the generous Somalia a new state’ and ‘helping the legitimate evolution of Somali people toward independence’). Moreover, the script points out that Italy's presence in this country continued under the aegis of the United Nations, rather than being motivated by mere national interests. These messages – directed both at Italian audiences and at other UN countries for whom the trusteeship remained a necessary tool for the ‘civilisation’ of the former colonial world – might suggest that the representation of the Italian action in Africa started to be projected onto the future. It thus began to be read against the background of Italy's new international position within the UN. However, such a forward-looking gaze did not alter the persistent portrayal of African people. Rather, this exotic backwardness kept Africans’ political and individual subjectivity anchored in colonial narratives, which had to justify the superiority of white people. It is not surprising that there is no room for any critical reflection on the colonial past. Instead, the footage pays significant attention to the compulsive exaltation of Italian industriousness, which now addresses the future economic possibilities of those Italians who had invested in Africa. Roads, bridges, dams, buildings and agricultural plants are no longer portrayed as mere remains of the former imperial presence; rather, they represent the tangible support for the Italians’ ongoing presence in the Horn of Africa.

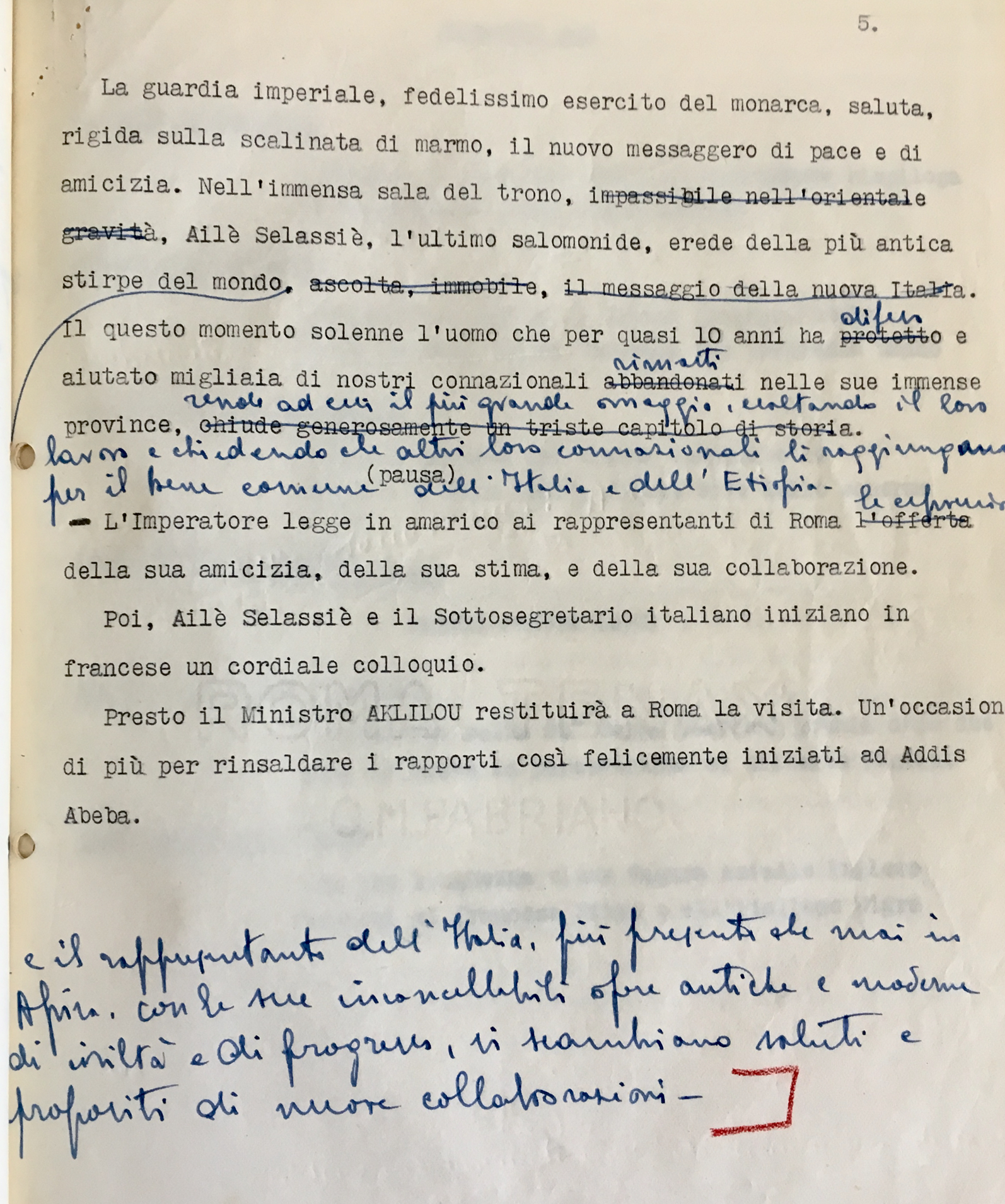

The film's concluding section is about the meeting between Brusasca and Haile Selassie, held in Addis Ababa on 7 September 1951. On that occasion, the emperor offered Italy official reconciliation and the resumption of diplomatic relationships (Del Boca Reference Del Boca1984). The exoticism that permeated the first part of the film is dissolved in this second part, so as to give institutional dignity to the emperor's words, through which he praises the Italians’ work and asks that ‘other Italians could join them in Ethiopia for the common good of both Italy and Ethiopia’. This sentence encapsulates how the footage selectively uses the figure of the emperor to avoid any form of repentance for what the Italians had done to the Ethiopians. If he does not criticise the colonial past, why should Italy do any differently? This unspoken rhetorical question inspires the documentary's concluding part. The handwritten note added at the end of the script leads the voice-over to say that Italy is more present in Africa than ever, with its ‘enduring activity of civilisation and progress’, evoking the obsessive exaltation of the myth of the lavoro italiano and the ‘aims of new collaboration’ (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Script of the Settimana INCOM 648 (folio 2), ASL, Rome

The disconnection between the colonial past and any critical judgment of Italian responsibility for the crimes committed in Ethiopia also characterises the newsreel Ailé Selassié stronca una congiura di palazzo, aired in late December 1960.Footnote 27 It is about a palace coup that was foiled by the emperor. As a whole, the footage expresses a sense of distance between the depicted episode and the Italian audience; INCOM certainly didn't produce the images in-house, and the commentary is a simple description of events that happened far away. Of course, almost 20 years had passed since Italy's defeat in Ethiopia, and the stylistic choices reflected that significant caesura. Such a drab style makes an interesting passage almost go unnoticed. At a later point, the commentary states that ‘the Negus is the Emperor of the oldest independent nation in Africa’, and ‘the world took notice of the Lion of Judah when, in 1936, he strived to defend Ethiopia from Italian occupation’. This is a remarkable passage: for the first time (as late as 1960), a non-fiction film admits that the Italian presence in Ethiopia was a military occupation of an independent and sovereign country.

Conclusion: disremembering, amnesty and the interruption of postcoloniality

The praise of Haile Selassie that features in the film I have analysed above is one of the first attempts the film corpus makes to reconcile Italian society with the memory of the invasion of Ethiopia. Nevertheless, throughout the footage, the critical appraisal of Italy's colonial past remains elusive, ambiguously oscillating between the repression and recontextualisation of previous discourses. In spite of the fact that the new presence in Africa was described as being inspired by values such as international cooperation, democracy and self-determination, the films resorted to a lexicon typical of the mission civilisatrice, which praised Italian industriousness and reproposed the exotic backwardness of Africans, who were unable to take care of themselves. In so doing, the footage ‘dismembers’ the historical result of the past relationship between Italy and its former colonies by portraying only the allegedly positive results. Such a selective re-articulation suggests that a controversial past was finally mastered through the disconnection between what had happened back then and Italy's new presence in Africa (De Cesari Reference De Cesari2012).

The verb ‘to dismember’ sounds very much like ‘disremember’: the metaphorical juxtaposition of these two words exemplifies the critical pathway that allows us to address the aphasic nature of Italian colonial memory. Colonial forgetfulness was sustained by the dismembering of the discourses through which Italy had previously justified its colonial endeavours. The debris of such a disarticulation was recomposed in the aftermath of the Second World War, in order to express a new discourse about the relationship with the former colonies. In other words, the pieces that composed the puzzle of the old colonial propaganda were not merely obliterated; rather, they were put back together but without using those pieces that did not fit into the new, positive portrayal of postwar national identity.

The process of selective memory and the omissions that characterise the uncertain vocabulary to describe the loss of Italy's colonies do not reflect a consistent act of silencing. Instead, the formation of colonial memory has hinged on a contradictory semantic field, in which divergent political utterances composed an a-grammatic discourse typical of any aphasic condition. The silences in the transmission of colonial memories are therefore unnatural: they are audible, tangible and intentional. This is consistent with what Dietmar Rothermund calls ‘conspiracy of silence’, which might be caused by a ‘feeling of shame or discomfort, an unwillingness to articulate repentance for deeds which one may not have done but which one had tolerated’ (Rothermund Reference Rothermund2015). This paradigm fittingly applies to the uncertain recollection of the imperial past that the footage conveys, in which the acts of silencing and dealing with the colonial period are peculiarly intertwined (Winter Reference Winter, Ben-Ze'ev, Ginio and Winter2010; Huyssen Reference Huyssen2003). The voice commentary orchestrated such a re-articulation: the several registers used in the films, the corrections, the added notes, the strike-throughs – all epitomise the fact that artistic and political stances went hand in hand. Accordingly, the voice-over concealed the wounds that a critical assessment of the most dishonourable aspects of overseas expansions would have opened. However, as a side-effect, this biased recollection engendered a disarticulated grammar of decolonisation, which made it extremely difficult to overtly question both colonial crimes and the more surreptitious occasions in which colonial discourses were retrieved and revitalised.

The reluctance to critically assess the Italian presence in Africa, which was palpable during the time span of decolonisation, materialised in an inadequate awareness about the colonial past and its related legacies. For these reasons, Italian colonial memory nowadays still seems scattered and weak, yet latently present in the subconscious of the nation. Alessandro Triulzi describes these mnemonic dynamics as confused and self-exculpatory, a kind of ‘backup file which can be accessed according to convenience or factuality’ (2006). Against this backdrop, aphasia has convincingly explained the artificial disconnection ‘between what happened back then and its contemporary legacies, be it transnational migration or the … alliances between postcolonial national elites’ (De Cesari Reference De Cesari2012). It thus points out the self-exculpatory strategies that eluded any repentance and made a real decolonisation of Italian memory and material culture difficult to achieve and unintelligible. As such, this concept merges with the metaphorical amnesty for colonial crimes and usurpation (Del Boca Reference Del Boca1982). Amnesty implies that legal authorities take no actions against a specified offence during a given period. The word has the same Greek origin as amnesia, and both refer to the idea of dimenticanza/forgetfulness. Nevertheless, if amnesia reflects a deficit of memory due to brain damage or psychological trauma, amnesty denotes the remission of certain illegal actions. It thus addresses a voluntary, legal and deliberate set of actions that cancel previous crimes.

The films examined here were part of that conglomeration of political practices that actively composed the conspiracy of silence about colonial crimes, which made the memory of the Italian presence in Africa biased, unproblematic and vague. This analysis has questioned concepts like amnesia and the removal of colonial history by exposing how the footage contributed both to disable the critical assessment of that past and to avoid the destabilising effects of a thorough post-colonial critique in postwar Italy. The combination of a rather ambiguous scenario of film production with the – no less uncertain – decolonial process allowed these films to play an effective role in the resurgence of a colonial way of envisioning the soon-to-be former colonial world. This footage has thus contributed to repress and disarticulate – more than to erase – the recollection of the colonial past. Accordingly, the intricate memory of that period has not simply evaporated. Rather, it seems to have become indecipherable yet present, detached from the main narrative of national history yet concealed in the ways through which to reimagine postwar subjectivities and collective identities.

Note on contributor

Gianmarco Mancosu received his first doctorate in Italian Colonial History at the University of Cagliari (2015) and has successfully defended his second doctoral thesis at the University of Warwick (2020). His research interests deal mostly with Italian colonial history and culture, film production about the Fascist empire and decolonisation, the post-colonial presence of Italian communities in Africa, and the memories and legacies of colonialism in modern and contemporary Italy. He has published extensively on these topics. He is currently working on a monograph about Fascist film propaganda about the Ethiopian war. He was ‘Luisa Selis’ Research Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory (School of Advanced Studies – University of London, 2018), and Research Assistant on the project ‘The Dialectics of Modernity. Modernism, Modernization, and the Arts Under European Dictatorships’ (University of Manchester, 2018). He is currently postdoctoral researcher in Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Cagliari.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions. In the preparation of this article, I have benefited greatly from the comments from Jennifer Burns, Derek Duncan, Stephen Gundle, Charles Burdett, Mary Jane Dempsey, Valeria Deplano, and Alessandro Pes. I am grateful to Patrizia Cacciani and Enrico Bufalini (Istituto Luce) for having granted me permission to use INCOM film stills. My gratitude goes also to Georgia Wall and Andrea Hajek for having edited this work.