In recent years, the international thought of National Socialism has become the subject of renewed interest among historians and theorists. This revival has come about, in part, through efforts to apply comparative historical perspectives to the study of Nazi imperialism.Footnote 1 It has also resulted from a growing awareness that the Nazi New Order sought to justify itself not only by appealing to the idea of “living space” (Lebensraum), but also by advancing a vision, however inchoate, of an international order that would structure Germany's relations with allies, neutral countries, and other great powers.Footnote 2 This project, which encompassed a critique of the existing liberal order as well as an effort to expound an alternative, was distilled in the concept of “great spaces” (Großräume), one of the most ubiquitous catchwords of Nazi political discourse, especially during the Second World War. By invoking it, German academics, journalists, and officials expressed their conviction that the age of sovereign nation-states, free trade, and multilateral institutions was coming to an end. They believed that the world was in the process of being partitioned among a handful of supranational blocs and federated continental behemoths, the “great spaces” that constituted the future of global order.

Owing, perhaps, to the close affinity between the disciplines of political thought and legal theory, scholarship on “great spaces” has largely become synonymous with the history of international law, and more specifically with the reception of the German jurist Carl Schmitt. In the months leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War, Schmitt proposed replacing the liberal international order with an “international legal order of great spaces,” whose underlying principle of nonintervention, derived from the early nineteenth-century Monroe Doctrine, was designed to provide a bulwark against the threat of liberal universalism.Footnote 3 Schmitt's academic prominence, combined with his now nearly canonical status as a critic of liberalism, have made him the central point of reference for scholars who study the theory of “great spaces.”Footnote 4 However, by focusing primarily on the legal dimensions of this discourse, intellectual historians have neglected one of the main reasons why contemporaries found the idea of “great spaces” so compelling. As this article seeks to show, their vision of a partitioned world was rooted in an interpretation of the fate of globalization that found widespread acceptance in late Weimar and Nazi Germany: the idea that the world economy was undergoing a dialectical transformation from globalization to economic nationalism and finally a new world order of “great-space economies” (Großraumwirtschaften).Footnote 5

Between the early 1930s and the end of the Second World War, numerous German writers proposed the creation of a “great-space economy,” which would enable Germany to decouple itself from the world economy through hegemonic association with neighboring European states.Footnote 6 While historians have studied the reorientation of trade towards Southeastern Europe during the Third Reich, there have been few attempts to reconstruct the theoretical presuppositions that underwrote it.Footnote 7 The characteristic feature of the discourse of “great-space economy,” as this article will argue, was its ability to combine seemingly opposing perspectives on globalization into a single developmental narrative. Proponents of “great-space economy” believed that globalization had unleashed economic, political, and ecological dynamics that would ultimately bring about its own destruction. Yet even as they prophesied international economic disintegration, they maintained that the world was experiencing convergence—not in terms of commodity or factor prices, but through the proliferation of common forms of economic and political integration at the sub-global level. The transformation of the world economy would not eventuate in isolated blocs, they argued, but in global relationships among “great spaces” that yielded a more stable and sustainable form of world economy. Despite its normative rejection of globalization, the economic theory of “great spaces” drew strength from the modern propensity for global thinking, the effort to make sense of local developments in terms of “a global context that can be understood structurally or even systemically.”Footnote 8 For German intellectuals, the explanatory power of a global frame of reference proved so enticing that even their attempts to partition the world availed themselves of it.

This article reconstructs the career of the preeminent theorist of “great-space economy,” an intellectual who served as one of its most important popularizers during the early 1930s and provided its most systematic apologia during the Second World War: the journalist and Nazi official Ferdinand Friedrich Zimmermann (1898–1967), better known by his nom de plume, Ferdinand Fried. Though his writings once attracted the interest of historians who studied the “conservative revolution” of the Weimar Republic, his oeuvre remains mostly unexplored.Footnote 9 Fried deserves reexamination, for he was one of the most imaginative defenders of a world order based on “great spaces,” and a theorist whose ideas anticipated, and in some cases directly impacted, the propaganda the Nazi regime employed to legitimize its hegemony over Europe. At the beginning of the 1950s, Fried resumed his journalistic career by arguing that the dawning Cold War proved him right: the world economy was fated to disaggregate into blocs under the leadership of great powers, albeit not in the way he originally expected. More clearly and consistently than any of his contemporaries, he tried to explain how visions of deglobalization and global convergence could coexist within the concept of “great spaces.” His career illustrates how the economic theory of “great spaces,” and the synchronous global comparisons it stimulated, provided a framework through which German intellectuals embraced the eclipse of liberalism.

The end of capitalism

Ferdinand Friedrich Zimmermann was born into a middle-class family in the town of Freienwalde in Brandenburg. After serving in the First World War, he began a dissertation about agricultural prices at the University of Berlin, but quit his studies during the inflation to take a job as a business correspondent for the Ullstein publishing company. In 1929, one of his colleagues, the journalist Hans Zehrer, took over the editorship of a moribund cultural journal called Die Tat (The Deed) and invited him to join. Die Tat quickly became the most important journal of the “conservative revolution,” the cultural movement whose critique of liberalism, social democracy, and parliamentarism mobilized intellectual opposition to the Weimar Republic.Footnote 10 Zimmermann, now writing under the nom de plume Ferdinand Fried, rapidly became one of Germany's most prominent economic journalists, publishing a regular stream of articles for Die Tat as well as two widely discussed books, The End of Capitalism (1931) and Autarky (1932).Footnote 11 His reputation spread far beyond the nation's borders. The End of Capitalism was translated into French, Italian, and Danish, cited by Benito Mussolini in one of his speeches, and refereed for English translation by the young Isaiah Berlin.Footnote 12

The leaders of the Nazi Party, who were searching for radical economic ideas to incorporate into their program, were enthusiastic about Fried's work. All the gauleiters and even Hitler himself were said to have read The End of Capitalism.Footnote 13 Fried later boasted about his clandestine contacts with the Nazis: “Since 1930 connection and continual contact with different circles and personalities of the N.S.D.A.P., since summer 1932 constant connection with the Reichsführer SS, Himmler, especially also during the chancellorship of Schleicher.”Footnote 14 These political connections enabled Fried to climb the professional ladder following Hitler's appointment as chancellor. After a string of journalistic promotions, he was hired by Richard Walther Darré to work at the Reich Food Estate (Reichsnährstand), the new agency tasked with setting agricultural prices and regulating food production. He joined in March 1934 as staff director for Herbert Backe, the director of Main Department A of the Staff Office, and succeeded him in November of the following year.Footnote 15 Fried propagandized on the agency's behalf, arguing that its model of economic planning should be applied to other sectors of the economy.Footnote 16 In September 1934 he was inducted into the SS in an honorary capacity and subsequently rose to the rank of Sturmbannführer in its Race and Settlement Main Office.Footnote 17

Fried owed his early professional success to his sweeping analysis of the Great Depression. In the final years of the Weimar Republic, he caused a sensation by claiming that the world economic crisis presaged the culmination of a secular trend, “the end of capitalism,” as the title of his first book declared. Echoing the views of his erstwhile teacher, the political economist Werner Sombart, Fried predicted the decline of laissez-faire capitalism, free trade, and extensive economic growth, and the end of liberalism as a guiding principle in economic life.Footnote 18 He regarded these developments as driven in large part by technological stagnation and cultural decadence. With the possible exception of the airplane, no early twentieth-century inventions could rival the epochal transformations initiated by the steam engine, locomotive, electrical generator, and combustion engine, he argued.Footnote 19 The captains of nineteenth-century industry had been succeeded by a generation of incapable sons, and the cohort of managers who took over their firms lacked the spirit of capitalism.Footnote 20 Finally, he claimed that the dynamics of a world economy based on free trade were ultimately self-destructive. As the non-European world industrialized, a phenomenon that appeared evident from the postwar trajectories of India and Japan, the demand for European manufactured goods would gradually decrease, leading to an unraveling of the global division of labor.Footnote 21

Though Fried expressed appreciation for Friedrich Engels's grim predictions about the concentration of capital and the growth of the proletariat, his sympathies lay with the fate of Germany's middle class of artisans, professionals, and white-collar workers.Footnote 22 The cure for Germany's economic ills, he believed, required embracing state planning and economic nationalism while ensuring that mid-sized private enterprises retained the freedom to organize their operations within overarching parameters.Footnote 23 He argued that Germany could regain its economic sovereignty by developing self-sufficiency in many primary products, but he accepted that its standard of living could not be maintained without importing some essential raw materials. To secure access to imports without incurring debt and dependency, he recommended that Germany divert its foreign trade towards the agricultural economies of Southeastern Europe, using a combination of preferential trade agreements and state-managed barter exchange. In doing so, he extrapolated from the currency controls, clearing agreements, and efforts at forging preferential treaties with Southeastern European countries that characterized the trade policy of the final Weimar governments, and anticipated the more radical measures that would subsequently emerge under Hjalmar Schacht's “New Plan.”Footnote 24 Fried and his fellow editors at Die Tat were among the first German writers to use the terms “great space” (Großraum) and “great-space economy” (Großraumwirtschaft) to describe the vision of an integrated economic zone incorporating Germany and Southeastern Europe.Footnote 25

Fried insisted that the formation of a German “great-space economy” was symptomatic of a global transformation. “What is presently happening is nothing other than a gradual process of decomposition or transformation,” he announced, “the collapse of the world economy into different economic spaces; a process that has been taking place for years and can still go on for years, and in which there are now and then little explosions, as we have abundantly experienced in recent times.”Footnote 26 With this allusion to a “gradual process” of economic disintegration, Fried associated himself with an older German tradition of theorizing the collapse of globalization. At the turn of the twentieth century, the global rise in protectionism, coupled with the emergence of powerful continental economies in the United States and Russia, led many observers to predict a forthcoming partition of the globe among “world empires” (Weltreiche).Footnote 27 As Fried surveyed the world in the worst years of the Great Depression, he perceived signs that the terminal disaggregation of the world economy had finally come to pass. The leading indicator, in his view, was the Ottawa Agreements (1932), in which Britain agreed to waive tariffs on most imports from its empire and impose new or higher duties on non-imperial goods, in exchange for preferential tariffs on its own exports to the Dominions and India. The fact that the former paragon of free trade was now engaged in constructing a preferential trading area signified the dawning of a new age of “economic spaces.”Footnote 28

Fried's publications stood chronologically at the beginning of an expanding popular discourse about economic “great spaces” in late Weimar and Nazi Germany. There was considerable variation in the way that writers addressed the topic. They emphasized different benefits to be gained from integration, such as increased economies of scale, insulation from business cycles, and security against blockade. Some advocated the formation of a customs union, while others believed that regional integration was better accomplished through preferential tariffs. Different authors nonetheless tended to advance a common thesis: the claim that “great-space economy” was not merely a German or Central European project, but rather a phenomenon that had to be comprehended in a global context. They saw the Ottawa Agreements as harbinger of the global proliferation of “great-space economies,” and they typically identified the United States, the Soviet Union, and the colonial empires of Japan, France, and Italy as the future blocs of the world economy.Footnote 29 They also suggested that a new kind of world economy would be forged after the collapse of global capitalism. Having attained self-sufficiency in staple commodities, “great-space economies” would not exist in isolation from each other, but would continue to exchange high-value and specialized goods to promote a rising standard of living.Footnote 30

The dialectics of deglobalization

Fried helped inaugurate the economic discourse of “great spaces” at the beginning of the 1930s. At the end of the decade, two months after the outbreak of the Second World War, he published Turning Point of the World Economy, a nearly 450-page treatise that presented the most extensive synthesis and elaboration of “great-space economy” in Nazi Germany. The path that led him away from service in the Nazi government and back to his career as a journalist began in January 1936, when he took a six-month leave from the Reich Food Estate, which he repeatedly extended before officially terminating his employment in March 1938.Footnote 31 Though a spell of illness was responsible for his initial absence, Fried reached an understanding with his employer that he would withdraw to devote more time to scholarly interests.Footnote 32 He left Berlin and eventually settled in an alpine Bavarian village, where he turned his hand to writing articles about the history of the world economy. These efforts resulted in a short tract, The Rise of the Jews, which interpreted the history of classical antiquity from the perspective of an “opposition between the Nordic and Semitic races,” and a cautionary tale about the decline of the independent peasantry, Latifundia Destroyed Rome, which attributed the rise of ancient capitalism to Semitic influences.Footnote 33 By early 1938 he had begun planning “a more extensive work about the world economy.”Footnote 34

Over the course of the next year and a half, a period in which Hitler's expansive foreign policy brought Europe to the brink of war, Fried attempted to provide the theory of “great-space economy” with a historical backstory and prospect for its future. He chronicled the rise and fall of globalization, surveyed the formation of “great spaces,” and outlined the dynamics that would govern their interactions in the future. What made his book distinctive was its effort to articulate the dialectical pattern that inhered in contemporary thinking about “great-space economy.” Turning Point of the World Economy sought to show how the collapse of the liberal world economy would lead to economic nationalism, then to large-scale blocs under the hegemony of a leading great power, and finally a new world economy comprising “great spaces.” It promised to reveal “the possibilities of future economic cooperation among the great nations [Völker] of the Earth, and the foundations for an entirely new organization of the world economy.” The book, which Fried finished writing shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, was published in early November 1939.Footnote 35

Turning Point of the World Economy presented an account that departed in important respects from Carl Schmitt's International Legal Order of Great Spaces, which appeared six months earlier.Footnote 36 Schmitt looked to the past to ground his concept of “great spaces.” He attempted to retrieve what he called the “core” meaning of the “original” Monroe Doctrine (1823) as the precedent for his new international legal order.Footnote 37 In his view, the United States had long ceased to honor its own principle of hemispheric nonintervention. The British Empire, sustained by a universalistic ideology, lacked the ideological and geographic coherence necessary for a “great space.”Footnote 38 The main protagonists of the current struggle of “great space against universalism” were Germany, Italy, and Japan.Footnote 39 While Schmitt chastised the Western powers for obstructing the rise of “great spaces,” Fried adopted a more global perspective. He tried to persuade his readers that a dialectical movement was sweeping all the nations of the world, liberal, communist, and fascist, towards the same destination: a world order composed of largely self-sufficient blocs, prone to violence along their peripheries, but ultimately capable of coexistence and mutually beneficial exchange.

Fried's book began by elaborating a counternarrative of globalization, one that argued that the liberal world economy had given rise to structural instabilities that were responsible for its destruction. Over the course of the nineteenth century, he observed, the global division of labor had created concentric zones of specialized commodity production around the industrial heartland of Northern Europe and the eastern United States, a macrocosm of the “Thünen circles” of economic activity that typically emanated from urban areas. This process had transformed previously independent economies into monocultures whose fates hinged on the vagaries of world markets. A shift in the location of production, or a collapse in prices, could spell existential disaster.Footnote 40 The production of cash crops for the world market encouraged ruthless exploitation of the soil, which precipitated dust bowls and floods in the American Midwest, desertification in Africa, and droughts in Argentina, Canada, and Australia.Footnote 41 Global capitalism was not only environmentally unsustainable; it also relied on political structures that were impossible to manage over the longer term. In anticipation of what social scientists would later call the theory of hegemonic stability, Fried claimed that any international economic order presupposed the “absolute political predominance” of a single great power. Only a hegemon could induce other nations to give up their economic independence and convince them that their needs would be met through the international division of labor. Such preeminence, while feasible on a regional level, was historically impossible to sustain on a global scale. Britain had been able to play the role of global hegemon during the nineteenth century, but it generated a host of competitors who checked its dominance in the longer term.Footnote 42

The first and most natural consequence of the collapse of globalization, Fried explained, was the reassertion of the nation-state. In the aftermath of the First World War, governments sought greater economic self-sufficiency to protect themselves against potential belligerents and uncertain world markets.Footnote 43 In the end, however, the traditional nation-state was incapable of fulfilling the productive potential of modern technology. Powerful industrial processes were generating economies of scale that demanded regional integration. The advent of the airplane, with its ability to effortlessly cross national boundaries, augured a new age of international organization. The world economy of the future would be based neither on globalization nor on radical autarky, he argued, but on “great spaces” that affirmed the economic integrity of the nation-state as well as the necessity of its incorporation into a larger economic unit.Footnote 44

Like all international economies, a “great space” could not survive without a hegemon, Fried argued. One nation (Volk) had to remain dominant in each. Yet the way that international power would be exercised in the future would be different from the imperialism of the late nineteenth century.Footnote 45 After the collapse of empires in the First World War, “no future development can any longer be based on domination [Herrschaft], but rather, as is the case for all bloc formations in the world, only on the free and equal consolidation of all individual parts to a community, or better yet, an association [Genossenschaft].”Footnote 46 Fried sought to naturalize the Nazi New Order by presenting it as essentially analogous to other forms of cooperative supranational association during the interwar period, such as the formation of the Soviet Union, or Franklin Roosevelt's “Good Neighbor Policy” towards Latin America. What particularly captured his imagination was the postwar transformation of the British Empire into a commonwealth, the granting of independence to its dominions, and its evolution “from an old imperialistic area of domination to a cooperative association.”Footnote 47 He suggested that Germany's relations with the nations of Central and Southeastern Europe would follow a similar pattern. However, in those cases where special “strategic and economic interests” came into play, Germany might treat its neighbors less like dominions and more like Egypt, Iraq, or colonial India.Footnote 48

Writing in the fall of 1939, Fried discerned seven “great economic spaces” (große Wirtschaftsräume) currently in the process of formation, led by Britain, France, Germany, Italy, the United States, Japan, and the Soviet Union.Footnote 49 Each would seek access to resources in sufficient quantities to reduce the vulnerabilities associated with the liberal world economy. This process could become violent, especially if “young spaces” were denied the chance to acquire adequate Lebensraum. Germany's “great economic space,” for example, was deficient in fats and tropical raw materials, and thus potentially in need of further expansion.Footnote 50 Yet conflicts between “great spaces” would not preclude the growth of trade among them. Here Fried expanded on an idea that had been raised by some writers in the early 1930s: the notion that “great-space economies” would continue to trade with each other, albeit mostly in high-value commodities rather than staple goods.Footnote 51 Fried made this topic a central issue of Turning Point of the World Economy, and tried to show how, in dialectical fashion, the quest for regional self-sufficiency would give rise to a world economy that brought the “great spaces” of the world together.

Fried offered several reasons to justify why intercontinental trade necessarily accompanied the formation of “great spaces.” In the short run, he argued, the striving for self-sufficiency would serve as stimulus to trade among blocs, as each sought to acquire the additional raw materials, capital goods, or labor necessary to develop its own capacities.Footnote 52 In the long run, technological progress and a rising standard of living would demand greater quantities of some raw materials than were present within the plausible boundaries of a “great space.”Footnote 53 The unequal geographical distribution of natural resources meant that “rarity monopolies” on some desirable raw materials—Canadian nickel and asbestos, Chinese tungsten, Congolese radium, or Indian jute—would persist long after the world's “great spaces” had reached the limits of their expansion. Prosperous consumers would demand goods that reflected “quality monopolies” and regional specialties, such as Egyptian cotton, Swiss watches, and German optics. Over time, intercontinental trade would gradually shift away from staple commodities towards higher-value goods that could be imported without incurring potentially existential dependencies.Footnote 54

A world where “great spaces” were constantly jostling against each other and striving to increase their control over essential economic resources, while simultaneously carrying out trade in goods of higher value, would resemble the civilizational plurality of classical antiquity, where commerce among the great land empires accompanied warfare along their peripheries.Footnote 55 Just as the Roman, Persian, Indian, and Chinese empires had once coexisted, “so can the Pax Britannica, Pax Americana, or Pax Germanica stand equally beside each other.”Footnote 56 The contrast with antiquity lay in the scale of production. Thanks to modern industrial technology, commerce in higher-value goods would benefit the lives of far greater numbers of people.Footnote 57 “It is not a unified world culture and world civilization that emerges,” he predicted, “but a manageable coexistence of different great and unique cultures in a world community.”Footnote 58 Only one group, according to Fried, would have no real future in this global order: the collapse of the liberal world economy necessitated the decline in power of the Jews, whom he portrayed as the greatest beneficiaries of the epoch of free trade.Footnote 59 But while he made an effort to associate his vision of “great spaces” with the regime's anti-Semitism, he identified race and ethnicity as only some among a number of factors that explained the internal cohesion of a “great space.”Footnote 60 Each of the world's “great spaces” possessed its own constitution and common identity, he argued. The British Empire was “in the first instance an ethnic community [eine völkische Gemeinschaft],” held together by the shared Anglo-Saxon identity of its rulers and settlers. The “space of Mitteleuropa,” in contrast, was “ethnically diverse, and held together by space and history.”Footnote 61

The world economy of “great spaces”

Published only two months after the outbreak of the Second World War, Turning Point of the World Economy articulated the contours of a new global order that was emerging in the minds of Fried's contemporaries. Though Hitler believed that Germany's economic future depended on territorial conquest rather than world trade, many Nazi officials and intellectuals came to envisage a multipolar world economy that would coalesce after the war had ended.Footnote 62 In June 1940, when France's defeat appeared imminent, the Economics Department of the Reichsbank planned for the emergence of a postwar world economy based on six “economic great spaces,” led by Germany, Italy, the Soviet Union, Japan, Britain, and the United States.Footnote 63 Walther Funk, the economics minister and president of the Reichsbank, announced that Germany would seek to maintain Europe's economic independence in times of emergency, while simultaneously pursuing overseas commerce to ensure a rising standard of living.Footnote 64 Numerous economists, executives, and officials echoed Fried's conviction that Europe would remain economically connected to other “great spaces” in the postwar global order.Footnote 65 The early German victories appeared to confirm the tendency towards violent consolidation that Fried described, but the pace of events soon rendered many of his characterizations obsolete. By the spring of 1940, two of the “great spaces” he enumerated in his book, the British and French empires, appeared slated for destruction.

In the hopes of ensuring that his broader claims remained unmuddied by contingent developments, Fried cut the sixty-two-page section that surveyed the “great economic spaces” of the world from the revised August 1940 edition of his book.Footnote 66 Yet he was unable to resist speculating about the future when other venues offered him an opportunity. In a November 1940 article, “The World Economy of Great Spaces,” he predicted the forthcoming division of the world into only four “great spaces,” led by the United States, the Soviet Union, Japan, and a German–Italian condominium. Fried depicted the wartime extension of “great spaces” into the southern hemisphere as an inevitable global phenomenon. By laying claim to the overseas colonies of their enemies, the Axis powers would acquire “supplementary spaces” (Africa for Europe, India and Southeast Asia for East Asia) that provided tropical raw materials. Meanwhile, the United States, faced with the prospect of losing access to critical sources of rubber and tin in East Asia, would increasingly turn to South America for its supplies.Footnote 67

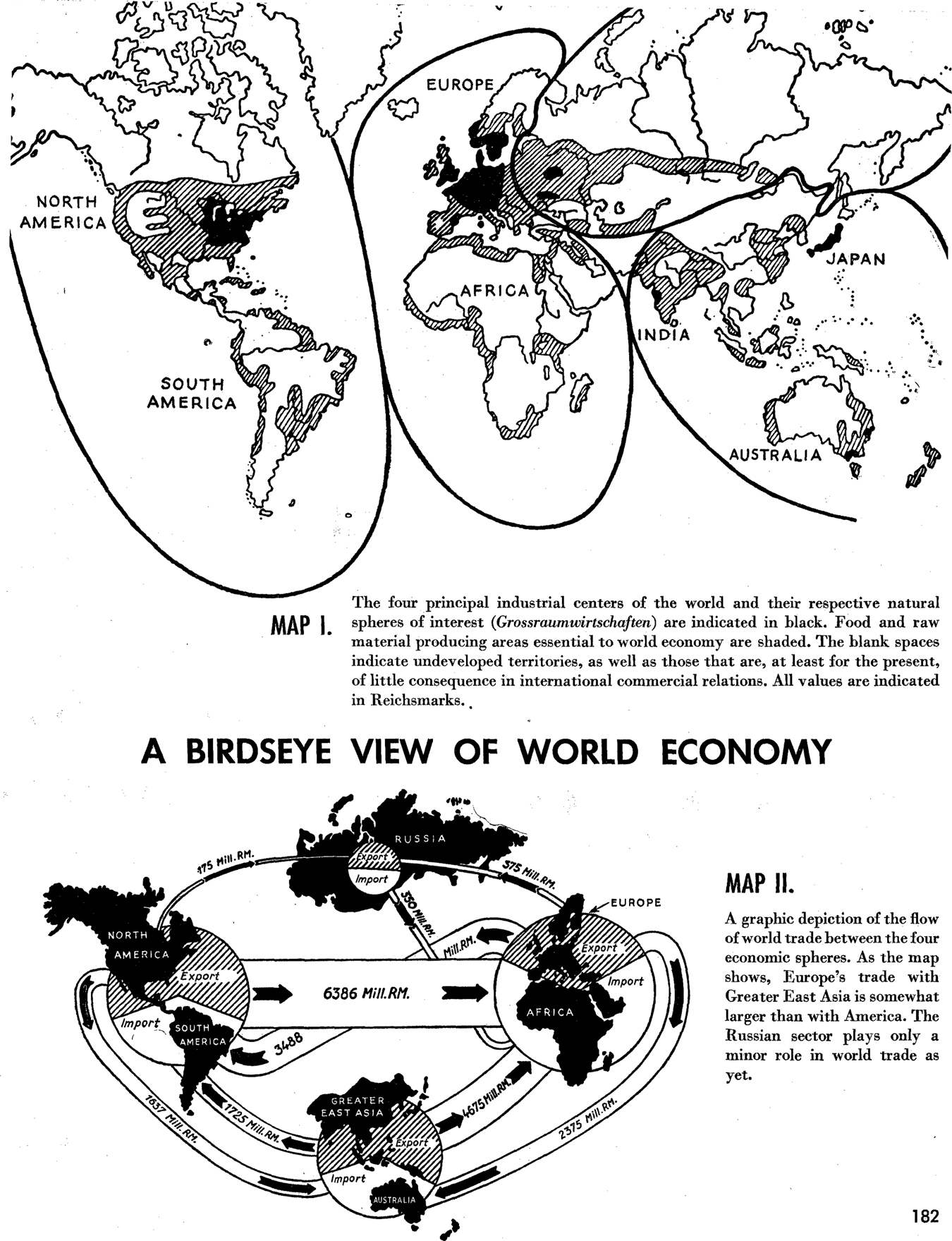

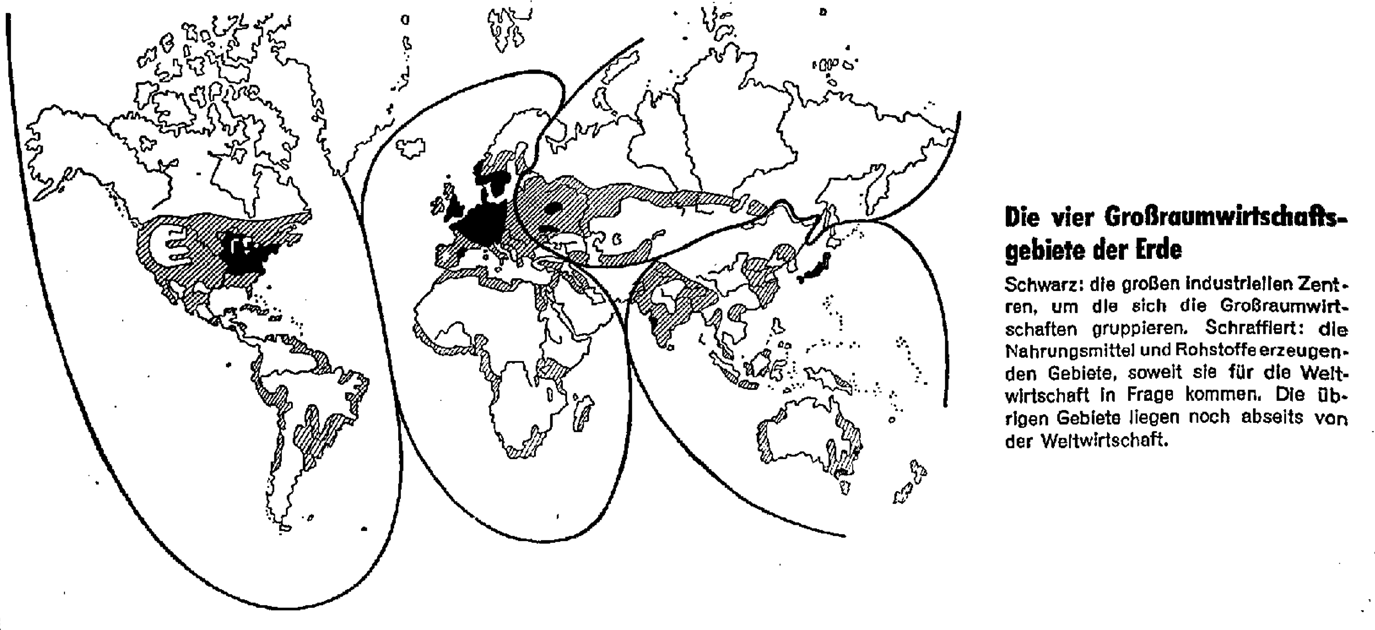

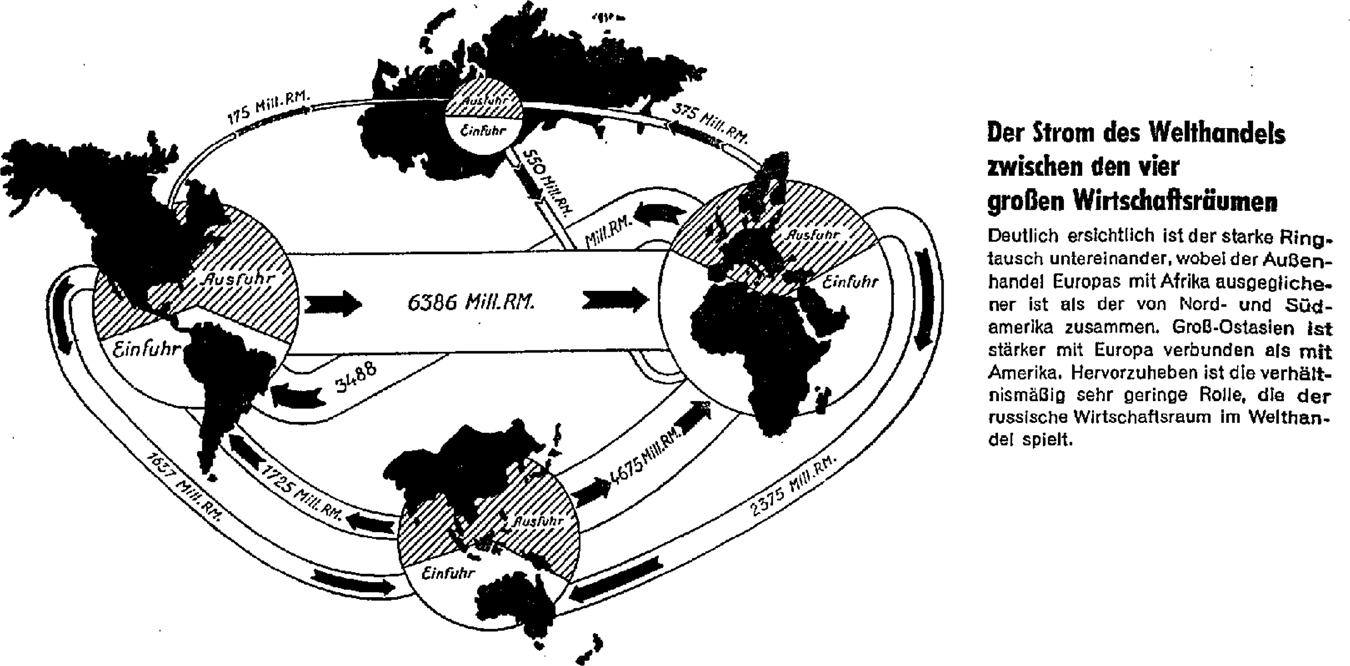

Fried not only anticipated key tenets of Nazi propaganda, but also contributed, perhaps unwittingly, to formulating them. The German Library of Information, a propaganda service affiliated with the German embassy in Washington, DC, republished portions of Fried's article to make Hitler's foreign policy more palatable to an American audience.Footnote 68 The April 1941 edition of Facts in Review, its English-language newsletter with a circulation of 100,000 readers, featured a two-page unsigned article titled “A Birdseye View of World Economy.” It consisted of five maps depicting “the four principal industrial centers of the world and their respective natural spheres of interest (Grossraumwirtschaften),” in addition to the flows of trade that connected them on the eve of the war.Footnote 69 Despite the absence of any editorial text, the general message of the article was unmistakable: the constituent elements of the world economy would be the spheres associated with the Axis powers, the Soviet Union, and the United States. By rendering the entire Western hemisphere as a single bloc, the maps implied that Germany did not threaten the regional hegemony of the United States. By depicting the flow of trade among the continental blocs of the future, they suggested that the political partitioning of the globe was compatible with a world economy in which both Europe and America played a major role (see Fig. 1). These maps have since acquired the status of classic Nazi propaganda aimed at securing American neutrality.Footnote 70 What has escaped notice, however, is that they were reproductions of the illustrations and captions that accompanied Fried's 1940 article, “The World Economy of Great Spaces” (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 1. “A Birdseye View of World Economy,” Facts in Review 3/13 (10 April 1941), 182–3, at 182.

Figure 2. Ferdinand Fried, “Die Weltwirtschaft der Großräume,” Das XX. Jahrhundert 2/8 (Nov. 1940), 311–18, at 316.

Figure 3. Ferdinand Fried, “Die Weltwirtschaft der Großräume,” Das XX. Jahrhundert 2/8 (Nov. 1940), 311–18, at 316.

Fried's ideas appeared in another notable Nazi propaganda document from the Second World War. In 1942, his former boss at the Reich Food Estate, Herbert Backe, the author of a “Hunger Plan” to starve tens of millions of Soviet citizens, published a book titled For the Food Independence of Europe: World Economy or Great Space.Footnote 71 It appeared with the same publishing house as Turning Point of the World Economy, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, and covered much of the same ground. Backe argued that “economic great spaces” represented “the inexorable conclusion of previous [historical] development.”Footnote 72 He narrated the division of the globe into “Thünen circles,” underscored the precariousness of monocultures, and advanced the thesis that free trade was self-destructive, since it degraded the natural environment and led to the industrialization of the non-European world. He portrayed the British Empire as both the chief protagonist of nineteenth-century globalization and the first mover in the formation of “great spaces.” He also held out the possibility of a “fruitful intercontinental exchange” of specialized commodities among “great spaces.”Footnote 73 Colleagues noted the similarities to Fried's work and wondered whether he was in fact the book's real author.Footnote 74

While Fried's writings helped contemporaries justify German hegemony over Europe, their popularity cannot be attributed solely to their propaganda value. His efforts to narrate the history of deglobalization from a global perspective fascinated readers and burnished his reputation as a serious intellectual.Footnote 75 Reviewers of Turning Point of the World Economy praised his resolution to “proceed not from the individual phenomenon but from the grand context” and his ability to “correctly illuminate the crisis of the world economy in a total historical framework.”Footnote 76 Fernand Braudel, one of the academic pioneers of global history, expressed enthusiasm for Fried's work despite its political content. After being captured by German troops in June 1940, the young French scholar spent two years in a camp for officers in Mainz and the remainder of the war in a camp on the outskirts of Lübeck. He subsequently became one of the most famous historians in Europe; for the time being, however, he delivered lectures to his fellow prisoners while working on the manuscript of his book about the sixteenth-century Mediterranean world.Footnote 77 In his camp lectures, Braudel referred to Turning Point of the World Economy with seriousness and at times even admiration, though he found himself unable to endorse its “pessimistic” vision.Footnote 78 Fried's sweeping narrative of the rise and fall of globalization represented, for Braudel, an exemplary mode of historiography. The best practitioners of “deep history” (histoire profonde) were not “historicizing historians,” he told his captive audience, but rather writers like the economist Ferdinand Fried, “whose advice is ‘to search for the deep meaning of events.’”Footnote 79

The most pointed rejoinder to Fried's ideas came from the German economist Wilhelm Röpke, one of the founding fathers of neoliberalism.Footnote 80 Röpke had commenced his critical dialogue with Fried in the final years of the Weimar Republic. Writing under the pseudonym Ulrich Unfried, Röpke assailed the contributors to Die Tat for what he regarded as their uninformed and irresponsible pessimism about the future of capitalism.Footnote 81 In May 1941, writing from Swiss exile, he resumed his critique by reviewing Turning Point of the World Economy in a three-part series for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Röpke made it clear that he took Fried seriously as a spokesman for important sectors of German public opinion. Turning Point of the World Economy conveyed “a far-ranging picture of notions that may count as representative for broad and influential circles,” which made its message all the more dangerous. What particularly troubled Röpke was Fried's “barely comprehensible optimism” that trade among “great spaces” would provide a more sustainable basis for the world economy.Footnote 82 There was no reason to assume that “the dinosaurs will one day lie down sated and peacefully beside each other like lambs,” he argued. It was more plausible that rival “great spaces” would continue fighting each other until one of them had achieved “uncontested world dominion.”Footnote 83 Only in a liberal world economy, where states were able to peacefully access economic resources that lay beyond their borders, could the small and large countries of the world live side by side. Röpke concluded his review essay with a call for a “third way” between “collectivism and laissez-faire.”Footnote 84

Röpke's critique was prominent enough to elicit Fried's reaction. In a front-page German newspaper article, Fried defended the “vagueness” of his vision as a mark of intellectual integrity: “Who would want to be so presumptuous to present how [a] great space should look, and how the great-space economy should function, as an exact plan to the very last detail?”Footnote 85 A more detailed response followed in the spring of 1943, when Fried embarked on a propaganda blitz across neutral Europe, delivering public lectures in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Zurich, and Geneva, and exchanging opinions with the economist and future Nobel laureate Bertil Ohlin in the pages of a Swedish newspaper.Footnote 86 Through these interventions he attempted to convince his audience that the postwar economic order would be based neither on free trade nor on economic nationalism, but on “great spaces,” the real “third way,” he claimed, appropriating Röpke's catchphrase. Fried was eager to convince his audiences that his vision of a “world economy of great spaces” was not a peculiarly Nazi idea, but rather the object of an emerging global consensus.

Only the “third way” remains for us … which is nothing other than the Hegelian synthesis between the thesis of the generally free world economy and the antithesis of autarky. I mean the integration of nations or national economies into larger living communities. In Germany we have coined the expression “great space” for this, and this word has lost its meaning and significance abroad through the political conflict. But that should not obscure the fact that the actual content of this concept is an objective condition of our world, and that the English were the first to try to realize it in practice, when, after the collapse of the free world economy, they provided the British Commonwealth with an economic foundation at the Imperial Conference of Ottawa in 1931 [sic]. “Commonwealth of nations”—that is also a designation for these new, natural living communities that are forming all over the world, for which the Americans have also already coined their own name, “cooperation.”Footnote 87

Fried pointed to a recent book, The Reconstruction of World Trade, by the former League of Nations economist J. B. Condliffe, to prove that his vision of a “world economy of great spaces” was hardly a “German quirk.” He quoted Condliffe, who speculated that “the creation of great economic regions … may prove to be the units between which international relations must be organized.”Footnote 88 Condliffe shared Fried's view that hegemony was essential for a liberal trading system. “If an international system is to be restored,” Condliffe declared, “it must be an American-dominated system, based on a Pax Americana.”Footnote 89 Fried regarded this outcome as highly unlikely. Barely a month after the German defeat at Stalingrad, he publicly acknowledged that the Soviet Union would remain a great power in world politics. If the United States tried to establish its global hegemony at the end of the war, he argued, the Soviet Union would surely rise to contest it. Any postwar attempt to restore the liberal international economy would founder on the clash of the new superpowers.Footnote 90

Fried made these pronouncements at a time when the discourse of “great spaces” was falling into disrepute. In September 1942, the Nazi propaganda official Walter Tießler began complaining about the ubiquity of the terms “great space” and “great-space economy.” While Tießler appreciated the need to inculcate “an understanding of global contexts” (ein Verständnis für Weltzusammenhänge) into the German population, he objected to any attempts at anticipating postwar outcomes that preempted the Führer's decisions.Footnote 91 Having received approval from the Party Chancellery, Tießler distributed guidelines that advised journalists and propagandists to refrain from any speculation about how the world might be divided.Footnote 92 Despite this campaign to suppress public discussion of “great spaces,” Fried was able to lecture on the postwar world economy throughout the spring of 1943. When he ultimately ran afoul of the Nazi authorities, it was because his interpretation of domestic affairs, not foreign policy, caught the attention of Party censors.

In the fall of 1942, Fried published a short book, The Social Revolution, which attributed the “social crisis” of modern times to the consequences of industrial technology and population growth. The solution to these issues, he argued, required that Germans embrace a new community based on the Volk, a planned economy, and an interventionist state. What ruffled the feathers of Nazi ideologues was not so much Fried's familiar prognosis as the technological determinism that appeared to undergird it. He portrayed the rise of the modern ethno-state as an inexorable outcome of industrial technology: “If the modern Volk is the level of community that corresponds to the state of technology, then technology provides the corresponding tool for actually managing such a large community.”Footnote 93 To his critics this sounded very much like an attempt to derive the superstructure of Nazi ideology from a materialist base. In March 1943, the journal National Socialist Economic Policy, published by the Nazi Party Chancellery, denounced Fried as a historical materialist who was drawn to National Socialism for all the wrong reasons.Footnote 94 Instead of encouraging “mankind” to come to terms with the challenges of modern technology, he ought to have declared war against the “Jewish world conspiracy.”Footnote 95 In the wake of this official condemnation, the Propaganda Ministry suppressed The Social Revolution and denied paper allotments for further printings of Turning Point of the World Economy. Fried's journalistic career in Nazi Germany had come to an end.Footnote 96

The partitioned postwar world

Fried was arrested by officers of the US Army Counter Intelligence Corps in his Bavarian village in November 1945. Though his rank as SS Sturmbannführer was sufficient grounds for detainment, Fried was also a person of interest to the occupation authorities on account of his erstwhile service as Darré's “right hand man.”Footnote 97 After spending a year and a half in a succession of internment camps, he was brought to Nuremberg in May 1947 for interrogation by Robert Kempner, the assistant US chief counsel at the International Military Tribunal. When asked about his literary activities, Fried proudly referred to Turning Point of the World Economy as “a thick book that was translated into several languages.” Kempner wanted to know whether it was a work of propaganda.

Q: Is it a National Socialist affair?

A: No. Not entirely.

Q: Only half?

A: Yes, perhaps half. It was reviewed altogether respectfully by Mr. Roepke in a Swiss newspaper.Footnote 98

Kempner informed Fried that he would not face charges from the Nuremberg military tribunals. What he wanted was information that could aid future prosecutions.Footnote 99 Despite the efforts to intimidate and flatter him, Fried chose to defend his patron in the Reich Food Estate. When Darré was tried at a military tribunal in the following year, Fried wrote an affidavit emphasizing Darré's outrage at the November 1938 pogrom and his rejection of the “imperialistic course” of Hitler's foreign policy.Footnote 100

After his stay in Nuremberg, Fried was returned to the internment camp at Regensburg to complete his denazification process. The public prosecutor sought to have him classified as a “major offender” (Hauptschuldiger).Footnote 101 Fried was able to muster a collection of affidavits from friends, neighbors, and colleagues, attesting to his scorn for the Nazi regime and his connections to elements of the resistance. The local curate and baker reported that Fried refused to give the “Hitler greeting” and eschewed any affiliation with the local Nazis.Footnote 102 A journalist declared that Fried had helped intelligence officers in Admiral Canaris's circle make contacts with interlocutors in neutral countries. An economist who was arrested after the 20 July 1944 assassination attempt on Hitler said that Fried intervened to save his life.Footnote 103 After considering this exculpatory evidence, the tribunal classified Fried as a “lesser offender” (Minderbelasteter) and sentenced him to a three-year probationary period, during which he was barred from working as a writer or editor.Footnote 104 In April 1948 he was released from his sojourn in “the pedagogical provinces of the twentieth century, where one is resmelted and purified under high pressure and strong flame,” as he ironically described his internment to Ernst Jünger.Footnote 105 On appeal, his probation was prematurely ended, and in July 1949 he was reclassified as a “fellow traveler” (Mitläufer), the lowest level of legal culpability.Footnote 106

It is difficult to determine how much truth there was, if any, to the testimonials Fried presented at his denazification tribunal. Many former Nazis and collaborators with dubious pasts were able to produce similar Persilscheine (“laundry tickets”). Fried's reputation as an opponent of the regime was strong enough, in any case, to persist well into the postwar decades. In 1964, the chairman of the Christian Social Union and former defense minister, Franz Josef Strauß, told a television interviewer that Fried had visited his barracks in 1943/44 to surreptitiously recruit officers for a plot against Hitler.Footnote 107 But even if Fried did, in fact, come to reject National Socialism, he did not abandon the dialectical vision of the deglobalization process that he expounded throughout the Third Reich. As he confided to Darré while still in Allied detention, “Some new and very powerful [literary] plans have also emerged behind the barbed wire, in new communities, and also connected to our old ideas.”Footnote 108 What Fried called the “old ideas” of late Weimar and Nazi Germany figured prominently in the books he began composing at the end of the war.

One of Fried's first postwar publications was Changes of the World Economy (1950), a book that he billed as a revised edition of Turning Point of the World Economy. Though he removed the sections that alluded to the era of National Socialism, Fried insisted that the predictions he made in the original 1939 edition still rang true: “The fundamental idea, from which the book emerged at that time, can still be altogether justified, namely that today the world economy finds itself in transition to a different form, from freedom to segmentation.”Footnote 109 Even though the war had not ended in an Axis victory, he argued, the world would remain partitioned in a way that precluded the revival of a liberal world economy. A survey of global affairs made this outcome plain to see. In addition to the United States and the Soviet Union, new continental blocs were emerging that would determine the world economy of the future. Europeans were beginning to appreciate the necessity of “a real overcoming of the national state.”Footnote 110 Mao's China had become an independent power in its own right, alongside India, which was embarking on a policy of industrial self-sufficiency. “They will certainly be different blocs than the German conception once imagined,” he conceded, “but at the same time every prerequisite for the unification of the world is missing.”Footnote 111 Opportunities for trade, especially in capital goods, would continue to exist between the new blocs of the postwar world economy, especially in light of their “ambitious plans” for industrialization, infrastructural expansion, and agricultural mechanization.Footnote 112 While the process of postwar European integration was driven by individuals whose ideological views were very different from Fried's, his enthusiasm for the project illustrates how wartime proponents of “great spaces” could merge into the mainstream of postwar European politics without disavowing their earlier ideas.

Just as he tried to convince neutral wartime audiences that his vision of “great spaces” was not a Nazi peculiarity, Fried sought to gain credibility for his prognosis by associating it with Allied schemes for postwar regional and federal orders.Footnote 113 “One may call the contemporary forms superstates or world empires, great spaces or blocs,” he wrote. “In the Anglo-Saxon diction one likes to talk of regionalism. But in these different terminologies and languages one means everywhere the same phenomenon of our time.” Fried's preferred term was “technical-economic communities,” which emphasized the degree to which the emergence of these blocs had been shaped by universal dictates of technology and economics.Footnote 114 He suggested that the vision of a world economy of “great spaces” had emerged like a phoenix from the ashes of the Second World War, its significance intact:

Even if arrogance and the drive for conquest started the war, nevertheless, in the course of the conflict, a conception forced itself on [the Axis powers], which at least in retrospect possesses a certain meaning. They opposed the American idea of the unified world with the conception of dividing the world into great spaces, and believed that an equilibrium of great spaces, if it were sufficiently flexible, would have secured a relative measure of peace and a reconstruction of the world economy. Admittedly, this [reconstructed] world economy would not have been one of absolute free trade, but rather a segmented world economy with great opportunities for exchange.Footnote 115

Fried argued that a multipolar global order sustained by five such blocs—the USA, the USSR, China, India, and Europe—offered the only viable alternative to the “eternal tension” of Cold War bipolarity.Footnote 116 Here he was ahead of Schmitt, who put forward his own vision of a plurality of “great spaces” as an alternative to Cold War bipolarity two years later.Footnote 117

Fried restarted his journalistic career just as he began it two decades earlier: by hitching his wagon to the star of Hans Zehrer, who reemerged at the end of the Second World War to embark on a successful career in the West German media. Fried began contributing to Zehrer's Christian weekly Sonntagsblatt in 1950 and followed him to Die Welt when Zehrer was hired as its editor in chief three years later.Footnote 118 Up until the mid-1950s, Fried expressed enthusiasm for a world economy comprising separate but cooperative political blocs. He compared Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe to the regional blocs of the 1930s and welcomed the prospect of its participation in a new world economy, voicing concern that West German businesses might be politically excluded from opportunities for “eastern trade” (Osthandel) by the Allies.Footnote 119 By the end of the decade, however, he had seemingly lost confidence that a mutually beneficial trading relationship between West and East could blossom. In comparison with the dramatic growth of international trade among Western nations throughout the 1950s, interbloc commerce remained at an insignificant level. The Soviet Union had no regional specialties to offer the world economy, only massive quantities of raw materials—most notably oil from its newly opened Siberian fields, whose cheap prices threatened to entrap Western Europe in new geopolitical dependencies.Footnote 120 The world economy had been partitioned, as Fried predicted, but the opportunities for exchange remained obscured by Cold War antagonisms. The vision of a thriving “world economy of great spaces” gradually disappeared from his writings.

Fried made a new name for himself as a chronicler and analyst of West Germany's Wirtschaftswunder. Still, his earlier career did not pass entirely unremarked. After the 1959 publication of Léon Poliakov and Josef Wulf's compendium The Third Reich and Its Thinkers, which reprinted Fried's curriculum vitae from his SS file, there could be little doubt about his involvement with the Nazi regime.Footnote 121 East German critics pointed out the parallels between his wartime and postwar writings, and the Stasi regarded him as a ripe target for propaganda campaigns against the conservative publisher of Die Welt.Footnote 122 But his colleagues and admirers were prepared to gloss over his activities in the Third Reich or at most grant them an oblique reference. “Zimmermann later frankly admitted that his diagnosis had been correct, but that he had erred in his prognosis,” the author of his obituary in Die Welt calmly stated. “Today his young colleagues believe him and try to understand him. They know Zimmermann as a person, his pure character. He had many opponents—he never could have committed evil.”Footnote 123

Conclusion

During the twentieth century, the idea that universal history follows a dialectical logic was embraced not only by Marxists and Cold War liberals, but also by radical conservatives and fascists, as the career of Ferdinand Fried and the discourse of “great-space economy” illustrate.Footnote 124 Like their interlocutors at other ends of the political spectrum, right-wing German intellectuals embraced an ideology of convergence. Their vision of a shared global experience was expressed through images of partitions, segmentations, and separations, rather than the metaphors of entanglement and connectivity that feature so prominently in twenty-first-century discussions of “the global.” Behind the growing division of the world, they perceived a common structural process at work, one that rendered the forms of international organization increasingly alike, even as the ties between continents were sundered and rearranged.

Throughout the Third Reich, and especially during the early years of the Second World War, the vision of a “world economy of great spaces” played a major role, arguably the predominant one, in the regime's articulation of its foreign-policy goals. In the hands of propagandists, the theory of “great spaces” served to normalize a global order based on violence and the subordination of weaker nations. At the same time, it aimed to assuage neutral countries about the limits of German ambitions; it held out the promise of coexistence and economic cooperation between the “great spaces” of the world once their tectonic shifts had subsided. It represented what may have been, to many contemporaries, the most attractive vision of global order after an Axis victory. Not until the winter of 1942–3 did Nazi officials see fit to curb this discourse. After that point, the struggle to defeat the Soviet Army and enlist local collaborators shifted attention to questions of political organization in German-occupied Europe, and planning for the postwar global order lost its sense of urgency.Footnote 125

Fried mobilized his theory of a “world economy of great spaces” to justify the regime's unfolding wars of conquest and annihilation, but he also realized that important elements of his vision were only contingently associated with National Socialism. The collapse of globalization during the interwar years, followed by the establishment of economic and political blocs after the Second World War, meant that his vision of simultaneous disaggregation and convergence retained some measure of intellectual plausibility, regardless of its political vector. Today it is difficult to imagine professional historians citing or otherwise affiliating themselves with Fried, not least because of the moral repugnance of his political views and personal decisions. Yet there was something in his imaginative conspectus that was capable of appealing to serious scholars like Fernand Braudel. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the idea that modern global history might be interpreted in terms of a “dialectical process of greater integration and greater fragmentation—the two being interrelated,” as one historian has put it, has become accepted as a productive methodological approach.Footnote 126

Seventy-five years after the end of the Second World War, as the neoliberal world economy faces crises of its own, specters of global order based on regional blocs have once again emerged, sometimes articulated in images from that earlier, cataclysmic era. “As the US loses its appetite for supporting the global institutions that have established the ‘rules of the game,’” one observer has recently mused, “it is not impossible to imagine that the twenty-first century will increasingly be characterized by Nineteen Eighty-Four-style superpower rivalry, with Oceania dominated by the US, Eurasia by Russia and Eastasia by China.”Footnote 127 Proponents of new spheres of influence are unlikely to stake their claims on the basis of the same arguments that Fried advanced. Yet much of his skepticism about the stability of the liberal world economy under conditions of global economic crisis, geopolitical competition, and ecological devastation rings eerily familiar. His vision retains its significance as a paradigmatic global theory of deglobalization, a topic that may gain in relevance as the institutions that sustained our most recent age of internationalism encounter powerful new challenges.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was supported by a General Research Fund grant (16400514) from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council. I am grateful to Peter Baehr, Mark Hopkins, Fabienne Pellegrin, and the journal's editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions.