Photographs do not need translation. They cross barriers of language and illiteracy to bring their message to people everywhere.

Ahmed Bokhári, under secretary of the United Nations, Photo-Monde (1955)Footnote 1

In 1955, the French National Commission to UNESCO hosted an international colloquium in Paris. Delegates from museums and organizations around the world debated the role of visual material in contemporary life and recommended the establishment of the Centre international de la photographie (fixe et animée).Footnote 2 Though never realized, the mooted international centre for the still and moving image was founded in a widely held belief in the ability of photography (and visual media derived from this technology, like film and television) to communicate across boundaries of language and nation. This essay examines the conception of photography as a universal language and its significance in the field of postwar international relations through the campaigns and publications of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The preamble to UNESCO's constitution famously asserts that, “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed”.Footnote 3 The organization reflected explicitly on the various media available to communicate and achieve this objective. This self-reflexive approach was enshrined in Article I of the Constitution, which stated that UNESCO would “collaborate in the work of advancing the mutual knowledge and understanding of peoples, through all means of mass communication and to that end recommend such international agreements as may be necessary to promote the free flow of ideas by word and image”.Footnote 4 In the early years, UNESCO thus represented a concerted effort to shape what Glenda Sluga has termed “a newly constituted and self-consciously international public sphere”.Footnote 5 The task was peace; the means, mutual understanding; the challenge, communication.

This utopian project was conceived and articulated in the historically conditioned culture of Western Europe in the 1940s and 1950s—a culture saturated with visual material, the most pervasive mode of representation being photography. As implied by the constitution's explicit emphasis on “word and image”, photography played a formative part in both the conception and the pursuit of this effort to establish an international public sphere. Jay Winter argues that any utopian discourse is expressed at a particular historical moment and is consequently bound up with “contemporary conditions and language”.Footnote 6 However, it is not only contemporary conditions and language that are important in assessing UNESCO's utopian project in the postwar moment. Visual culture is also central to such an assessment. The title of the French photo-magazine which published a special edition on “The Human Community” to mark the tenth anniversary of the UN suggests the ubiquity of the medium and the need to analyse its impact; Photo-Monde implies not simply photography of the world, but a world constituted by photography. A historical understanding of the pursuit of an internationalist agenda in the postwar world must address the intertwining of language, visual culture and ideas.

To do so, this essay analyses two ideas mobilized as part of UNESCO's early efforts to shape a postwar international public sphere (world culture and world citizenship) alongside two key publications (the Human Rights Exhibition Album and Children of Europe). First of all, an examination of the visual culture of the postwar moment is required (with reference to the photo-magazine UNESCO Courier) in order to explain how UNESCO's deployment of mass communication technologies had its roots in a wartime experience which gave rise to a discourse of international relations permeated with visual terms and figures of speech. This broader visual discourse includes one of the most widely discussed phenomena in the history of postwar photography, The Family of Man, curated by Edward Steichen (who attended the UNESCO-sponsored colloquium on photography in 1955) and critiqued by Roland Barthes. However, as will be demonstrated, this prominent example and its familiar critique are insufficient models for a fine-grained historical analysis of the work of UNESCO. While in principle it is possible to commit to internationalism (a belief in the merits of organizing international cooperation to address issues of human welfare) without committing to universalism (the belief that certain ideas, ideals or actions have universal validity), examination of the conception and deployment of photography as a universal language reveals that internationalism and universalism had a problematic relationship in the postwar debates and early campaigns of UNESCO. Overlapping and sometimes contradictory internationalist ideals expressed by the organization and promoted through its strategy of mass communication entailed specific universalizing assumptions or particular universal claims.

MASS COMMUNICATION IN THE POSTWAR MOMENT: THE MIRROR AND THE WINDOW

Benedict Anderson highlighted the printed word as fundamental to the establishment of national identities up to the nineteenth century by promoting a shared, standardized language.Footnote 7 At the start of the twentieth century, the advent of affordable reproduction of photographs greatly added to the resources of “print-capitalism” (the deployment of the printing press within a capitalist society) in creating “imagined communities” (intellectual and emotional bonds between individuals who may never meet, but consider themselves part of the same collective). The political mobilization of modern media techniques was refined and advanced during the century's early decades. (Indeed, Hanno Hardt suggests the term “mass communication” may have been coined in the early 1940s “in the context of government work related to propaganda activities”).Footnote 8 And as a consequence of public-information campaigns during the Second World War, mass communication became an increasingly salient feature in the postwar relationship between a state and its subjects. As Francis Williams (controller of news and censorship at the British Ministry of Information from 1941) argued, a “new conception of Government Public Relations . . . developed during the war”.Footnote 9 Photographically illustrated products became commonplace to the extent that, when it came to re-establishing a public sphere in defeated Germany, one of many public-information initiatives undertaken by occupying Allied forces was the establishment of a photo-magazine, Heute.Footnote 10 Mass communication initiatives were not limited to meeting national agendas, however; in the postwar period mass communication played an important role in international relations, as noted in one of the first histories of UNESCO.Footnote 11 Uniquely for an international organization at the time, UNESCO debated the role of mass communication in meeting its constitutional aims from the start.Footnote 12

The postwar moment represents a watershed in political, technological and cultural terms. Owing to the political will to establish a new world order (exemplified in the creation of the United Nations), the years after 1945 marked what Jürgen Osterhammel and Niels P. Petersson characterize as “a global turning point” in terms of international relations.Footnote 13 The period was also marked by the further development and increased availability of technologies affecting impressions of space and time, such as faster transport and more pervasive communications media. Related to these political and technological issues producing easier and more rapid movement of people, products and ideas around the globe was a concerted effort to imagine various transnational communities. The postwar moment thus entailed an epochal shift from the monopoly of national identities to an increased sense of the world beyond national boundaries—what Manfred B. Steger terms the rise of the “global imaginary”.Footnote 14 Internationalism and the establishment of a global imagined community became a concerted intellectual project in the postwar moment, as the concept of the nation state and the establishment of national imagined communities had been previously. The establishment of UNESCO did not inaugurate thinking about the problem of peace as a lack of knowledge hindered by differences of language and of culture. What differentiated the postwar effort from previous initiatives was the increased political will for and technological possibilities of promoting such an idea.

Photography—the technological innovation underpinning modern visual culture—was a key facet of this internationalist project. Developments in image-making, telecommunications and printing, and the efficient transmission and affordable reproduction of photography, represented a further influence on (to paraphrase Anderson) the manner in which people thought about themselves and related themselves to others, helping to reshape imagined communities from national to potentially transnational entities.Footnote 15 Media like radio and television were eagerly mobilized to meet UNESCO's objectives along with the printed word, but in the organization's first decade, photo-books, photographic exhibitions, photo-magazines and other illustrated ephemera offered a particularly compelling means to overcome barriers of nation, language and even illiteracy.Footnote 16 Two examples illustrate this point. In 1950, Leigh Ashton, director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, wrote a preface to UNESCO's bilingual Répertoire international des archives photographiques d’oeuvres d’art (1950), in which he argued for the photograph as a neutral and transparent medium valuable to scholars and students. Ashton described the photographic reproduction of works of art as “the guide and counsellor of all study”, able to speak with “an International Voice” and “act as an Ambassador”.Footnote 17 Likewise, the development and publication by the Department of Mass Communication of UNESCO's own photo-magazine, Courier, demonstrates the considerable value placed on photography. Originally a newsletter published from 1948 in a newspaper format, Courier was refashioned and relaunched in 1954 in a format resembling the successful photo-magazines of the time, such as Picture Post (1938–57), Life (1936–72) and Paris Match (1948–).Footnote 18 The editorial stated that the publication would “serve as a window opening on the world of education, science and culture through which the schoolteacher in particular—for whom this publication is primarily conceived and prepared—and other readers in general can look out on to wide global horizons”.Footnote 19 Ashton's comment on photography's ambassadorial potential employs a diplomatic metaphor to assert the importance of the medium to postwar cultural diplomacy, while the editorial's articulation in visual terms of education, international relations and peace implies that if one views the world from the right perspective, the rectitude of an internationalist standpoint is self-evident or plain to see.

Photography did not simply offer itself as an available means to meet the ends of an independently conceived internationalist agenda; it also held a central position in UNESCO's conception of its diplomatic mission pursued through mass communication. The conception of what photography was (a universal language) and of what cultural diplomacy should strive to achieve (mutual understanding) dovetailed, because ways of thinking about the medium and the internationalist challenge were co-constitutive or mutually dependent.Footnote 20 The prominent role of visual culture in the public-information material produced by all sides in the Second World War fostered a conviction in the potency of images on a global stage, bringing mass communication to the top of UNESCO's agenda. Vision—both metaphors employing visual terms like the “window on the world” and photographs themselves—was threaded through the project of securing peace in the postwar decade. In the historical and cultural context in which UNESCO was established, mutual understanding meant facilitating the right way of looking at the world and its problems—a way of looking which needed to be actively promoted and created. The many official UNESCO publications designed to promote the organization's work and popularize its utopian aspirations (including magazines, exhibition materials and photo-books) constitute a collection of “image-over-text” publications in which the photograph is the main operative or communicative element.Footnote 21 These publications were informed by a discourse that united peace and vision through photography.

This discourse encompassed The Family of Man, a renowned photographic exhibition seen by over nine million people in thirty-eight countries which also drew heavily on the imagery and conventions of the photo-magazines of the time.Footnote 22 The exhibition is frequently discussed as the most salient example of the conception of photography as a universal means of communication, but although the exposure it received was unparalleled it was by no means unique.Footnote 23 The exhibition's commitment to photography as a universal language mobilized in the service of peace was shared by many other lesser-known photographic initiatives of the 1940s and 1950s, including UNESCO-backed projects aimed at promoting mutual understanding. Roland Barthes famously criticized Steichen's exhibition for evading questions of history and injustice: “Everything here, the content and appeal of the pictures, the discourse which justifies them, aims to suppress the determining weight of History.”Footnote 24 According to Barthes, Steichen's vision—and by implication UNESCO's too—meant that viewers were “held back at the surface”, prevented from understanding individual situations by a sentimental rendering of human experience. This critique could be levelled at the cover image of the first magazine-format issue of Courier (Fig. 1). Used with very little accompanying text, the closely cropped photograph of a young girl's face can be taken to represent something other than the individual's experience, or that of a particular community or country. This mode of visual and verbal representation works to decontextualize the experience of a particular individual, projecting it instead onto a supranational plain. Determinate choices frame the image, not as that of a particular young girl in a particular time and place, but as a metonym for human experience. Thus the image of the girl is not so much universally comprehensible to all individuals through the universal language of photography; rather the individual's experience is universalized. The young girl on the cover symbolizes human experience, but, in this process of universalizing, the specific details of her past, present and future fall away.

Fig. 1. Young girl of unknown country (described on contents page as a “young Indian girl of the Amazon”). Cover of UNESCO Courier, 1 (1954). Photographer unknown. Reprinted from UNESCO Courier. See http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0007/000781/078140eo.pdf.

Barthes's evaluation of this postwar visual discourse is compelling, but it has become a one-size-fits-all critique of humanist photography. This mode of representing is not simply facile or limiting, as Barthes suggests. At a UNESCO-sponsored event in 1955, writer and curator André Chamson expressed grave concern regarding an apparent public thirst for images. For Chamson, the invention of photography marked a radical shift in society's self-representation and self-conception, comparable to the invention of the printing press, but with devastating potential. He described a tidal wave engulfing humanity which threatened to break down the individual's capacity to understand their world.Footnote 25 The ubiquity of photography, Chamson argued, results not in mutual understanding, but in a fracturing of comprehension through the medium's capability of bringing together objects and people distant in time and space. Understanding the role of photography in the work of UNESCO in its first decade demands an examination of the implications of Chamson's concerns regarding the organization's “image-over-text publications”. The photography mobilized by curators and editors for UNESCO exhibitions and publications does not simply occlude or frustrate understanding (Barthes's “holding back at the surface”); it potentially produces new ways of perceiving and conceiving the world. It is not simply reductive; it is potentially productive of new attitudes and intellectual standpoints.Footnote 26

In his introductory essay for the catalogue, Steichen (who had worked in aerial reconnaissance in the First and Second World Wars) stated his belief that photography could offer “a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world”.Footnote 27 Like the window on the world of Courier, Steichen's mirror metaphor highlights how various internationalisms of the postwar period were shot through with questions of vision. Together these figures of speech are indicative of two distinctive representational strategies examined in the following sections: one depicting cultural artefacts, the other picturing the human face. UNESCO publications sought to frame cultural artefacts in a manner that would imply a shared heritage for a global imagined community (the window). UNESCO also used images of individuals to conjure a sense of shared humanity, presenting the human face and inviting identification with or recognition of it (the mirror). These metaphors reveal the inescapable partiality or agency of modes of visualization. An image is never simply a transparent medium or a faithful reflection. The window, like photography, frames a scene, excluding elements and accentuating that which is included. Similarly, the mirror distorts that which it depicts, reflecting a reversed image and reducing three dimensions to two. Both metaphoric characterizations of photography inadvertently highlight the constructed nature of the photograph, deconstructing the conception of photography as a universal language and suggesting instead that photography is a mode of visualizing which produces constructed and intentional images. This discourse on photography as a universal language was underpinned by the conviction that photography was both a transparent and a universally comprehensible means of expression. In actuality, this discourse entailed a constant slippage or cross-fertilization between the circulation of visual material and figures of speech characterizing the challenge of postwar peace-building in visual terms.

WORLD CULTURE AND HUMAN RIGHTS: LANDMARKS OF CIVILIZATION

Working alongside the UN Commission on the Rights of Man, UNESCO had established a committee chaired by historian E. H. Carr to consider the content of a charter.Footnote 28 Following the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on 10 December 1948 by the UN General Assembly, UNESCO adopted its own resolution to promote the Declaration. From October to December of 1949, UNESCO held an exhibition at the Musée Galliéra in Paris.Footnote 29 Using material selected for this exhibition, the following year the organization's Department of Mass Communication produced and disseminated 12,000 copies of the Human Rights Exhibition Album.Footnote 30 Aimed at facilitating exhibitions in member countries, it consisted of 110 loose-leaf, monochrome, large-format plates carrying either photographs or photographic reproductions of paintings and engravings. This visual material was accompanied by mountable titles and captions; a text titled “A Short History of Human Rights”, designed to assist those hosting complementary events or tours; and a small pamphlet detailing alternative ways in which to present the album, with sketches illustrating ways to “improve the presentation and visualization” of the narrative and themes depicted in the plates and captions.

While the majority of illustrations are divided into fourteen themes (each covering the historical struggle for a particular right or set of rights), the first two dozen images offer a preamble. From prehistory to the postwar period, Plates 2 to 25 employ imagery ranging from the fossilized footprint of a cave-dweller to the Parisian debating hall in which the UN first met. Within this context, images of architecture are used to symbolize the high-water marks of previous cultures. Plate 13 (Fig. 2), for instance, shows the ruined Temple of Poseidon next to a photograph of a bust of Socrates, while Plate 17 shows a photographic reproduction of an engraving of the destruction of the Bastille in July 1789. Widely differing cultures and histories are, by their distillation into a few select images, offered up as comparable or equivalent steps in a continuous history. The “Short History” booklet encapsulates this use of architectural imagery with various spatial metaphors. Describing the achievements of past cultures as “landmarks”, it also states that “the illustrations mark the stages along the road leading from the cave-man . . . to the free citizen of a modern democracy”. Thus, the Human Rights Exhibition Album works to universalize icons such as the Bastille or a Greek temple, glossing the contradictions and conflicts of the past under the image of a shared heritage for an imagined global community with which viewers were invited to identify. The universalizing tendency immanent in the promotion of this internationalist concept of world culture is also reflected in the organization's choice of a Greek temple as its logo, and like the imagery of the exhibition album the choice of logo highlights a Eurocentric view of the principal stages of human development.Footnote 31

Fig. 2. Two photographs depicting an antique bust of Socrates (Louvre) and the ruined Temple of Poseidon (Cape Sounion). Plate 13 in Human Rights Exhibition Album, “Science and Conscience”, © UNESCO 1950. Photographers: unknown and Antoine Bon. Used by permission of UNESCO. Reproduced courtesy of Katrine Bregengaard.

Architectural imagery is also pressed into service in the visualization of individual rights in the second part of the exhibition album. The city is represented as the place in which legitimate debate occurs, in which the free citizen exercises his rights. Under the theme “Freedom of Thought and Opinion”, Plate 77 (Fig. 3) offers a depiction of political activism. It shows an orator at Speakers Corner, Hyde Park, and rally posters on a Parisian wall. Under the theme “Freedom of Religion”, Plate 73 (Fig. 4) again represents Parisian streets. The viewer is offered a selection of nine religious buildings (including a mosque, a synagogue and churches of various denominations), with a caption that reads, “Freedom today is enjoyed by almost all religious bodies, and there is nothing to prevent different religions from existing peacefully side by side in one city.” Thus Paris (where UNESCO was and is based) stands for the city in general. In turn, this abstract city is presented as the site at which tolerance is realized in the modern world, as if urbanization and freedom of thought are mutually supporting phenomena. There is a dark irony in these visualizations of liberty. Despite the depiction of religious tolerance through juxtaposed Parisian religious buildings in Plate 73, the city was the site, in July 1942, of the rounding up and deportation of over 13,000 members of the Parisian Jewish population. Prior to deportation, they were held in the same velodrome—the Vel d’Hiv—referenced in a poster picture in photograph C, Plate 77. Notwithstanding such unintentional references, there is a subtle but persistent idealizing of architecture and city space in the visualization of the struggle for human rights which reveals a value judgement at the core of the exhibition: civilization and, by implication, the pursuit of human rights find their ultimate expression in urban life. The urban imagery of the Human Rights Exhibition Album mobilizes the image of the city as an icon of an imagined global community—albeit that less than thirty percent of the global population lived in urban areas in 1950.Footnote 32

Fig. 3. Four photographs representing political activism including (upper left) a procession during the US presidential campaign, 1944; (lower left) public reading of a newspaper “among the Kirghiz”; (upper right) political posters on a Paris wall; and (lower right) a meeting in Hyde Park. Plate 77, in Human Rights Exhibition Album, “Freedom of Thought and Opinion”, © UNESCO 1950. Photographer unknown. Used by permission of UNESCO. Reproduced courtesy of Katrine Bregengaard.

Fig. 4. Nine photographs of places of worship in Paris, captioned as follows: “Religious buildings in Paris. (Reading from the top, and from left to right): Moslem faith. Mosque (Place du Puits de l'Ermite). Greek Eastern Church (Rue Georges-Bizet). Apse of Notre-Dame./Armenian Church (Rue Jean-Goujon). Maronite (Rue d'Ulm). Protestant: L'Oratoire (Rue de Rivoli)./Jewish Synagogue (Rue de la Victoire). Russian Orthodox (Rue Daru). Church of St. Julien-le-Pauvre.” Plate 73, in Human Rights Exhibition Album, “Freedom of Religion”, © UNESCO 1950. Photographer unknown. Used by permission of UNESCO. Reproduced courtesy of Katrine Bregengaard.

Architecture and urbanism, however, are not the only sources of imagery in the exhibition album. Culture generally conceived is the principal subject, architecture and urban experience being just one privileged instance. Photography is used to picture diverse artefacts from diverse cultures, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics and other utensils or devices. From prehistoric tools to the modern press, the changing artefacts of everyday life are pictured in such a manner as to represent a narrative of progress which is the visual correlate of the human rights struggle. This narrative of continuous progress was an idealized view—as Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann characterizes it, the history of human rights is “marked more by ruptures than continuities”Footnote 33—and there are notable exclusions from the available examples of the struggle for rights. The catalogue of objects on display includes seminal texts like the British Magna Carta (1215) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), but the Russian Declaration of the Rights of the Toiling and Exploited People (1918), for instance, is not mentioned. The Soviet Union is, in a sense, the exhibition's unconscious; while not explicitly referenced, the threat of nuclear war animated much of postwar visual culture.Footnote 34 Images of Nazism, on the contrary, are mobilized in the Human Rights Exhibition Album as a foil to the image of world culture. Photographs of adulation of Hitler, the burning of books and Buchenwald concentration camp are used to assert that the denial of rights is barbarism. The abolition of slavery offers another micro-narrative of the triumph of justice over injustice, subsumed in the overall trajectory of human development. Yet communism—like the vexed ideological questions raised by colonization and decolonization—is notable by its absence, edited out to facilitate the visualization of civilization's progress as a unified narrative.Footnote 35

The diverse images and captions of the album oscillate between two different conceptions of culture: as a collection of material objects and as a shared way of life. Both demonstrate the instrumentalization of the concept of culture in pursuit of UNESCO's peace aims. Photography facilitates the comparison of cultures distant in time and space, bringing them together through metonymic representations to forge a picture of human civilization in which each culture is simply a component part. Plate 92 (Fig. 5) and Plate 93, for instance, come under the theme “Liberty of Creative Work”. The caption for Plate 92 reads, “The heritage of civilizations consists in the work of its artists, scientists and thinkers. Every civilization creates a new vision of man which is the mark of its contribution to history.” These photographs of carved, painted and mosaicked faces work to humanize diverse cultures, representing them through recognizably human faces. Thus the image of world culture forged by the exhibition album—like reference to “the human family” in the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—collapses difference and projects oneness. Representations of diverse artefacts play a role in creating an image of this world culture, universally participated in by all nations and historical periods and possessing a democratic teleology.

Fig. 5. Four photographs of sculpted heads from different historical cultures, captioned as follows: “A. Negro art. B. Buddhist art. C. Egyptian art (Head of a colossal statue of Amenophis IV, Karnak). D. Totonacan art (Terra-cotta)”. Plate 92, in Human Rights Exhibition Album, “Liberty of Creative Work”, © UNESCO 1950. Photographer unknown. Used by permission of UNESCO. Reproduced courtesy of Katrine Bregengaard.

This construction of a universal conception of culture was a vital enabling concept in UNESCO's campaign to promote the Universal Declaration: the concept of world culture implies a shared ground (and historical goal) constituting the global public sphere in which a declaration of human rights can have universal application. The role of photography and photographic reproduction in this process of visualizing culture and history is not incidental; it is foundational, as becomes apparent from considering André Malraux's contemporaneous argument regarding photography's creation of a “museum without walls”.Footnote 36 Malraux contended that photography changed the way art was thought about, transforming art history into “the history of that which can be photographed”.Footnote 37 While the museum divorced art from its original context and function (be it religious devotion or signification of status), the use of photographic reproduction added to this decontextualization, implying that all works are comparable and thus part of the same narrative of development. Indeed, according to Malraux photography does not simply facilitate comparisons of diverse styles and movements; it demands them, framing all works (whatever separates them in terms of distance and time) as contiguous parts of a whole and engendering an attitude to culture as a shared patrimony. The medium, in Malraux's view, is a dynamic, productive influence, since the “specious unity imposed by photographic reproduction on a multiplicity of objects” makes art “for the first time the common heritage of all mankind”.Footnote 38 In the case of the campaign to promote the human rights agenda, not only is photography a means by which the cultures of the world can be synthesized into a world culture; its history of reproducing cultural artefacts also implicates the medium in the very possibility of conceptualizing world culture.

But what are the ramifications of this visualization of world culture, of synthesizing through photography diverse cultural artefacts in an effort to forge an imagined global community? In short, culture is reified. It is viewed not as lived experience, but as a set of objects available for arrangement and exhibition. This is a decontextualizing view of culture; photography is both a condition of its possibility and a tool of its realization. Culture, refracted through the prism of photography, becomes a set of musealized artefacts, divorced from everyday life of 13,000 BC and AD 1950 alike. This conception entails an appropriation of culture and subsumes it into the categories of the museum: the implication is that it can only be understood and appreciated within this context, and that understanding and appreciation are the appropriate operations when faced with diverse cultures. However, in decontextualizing cultural artefacts and placing them in a relation of equivalence with one another, the museum without walls created by the exhibition album does not respect diverse cultures or accommodate difference. UNESCO's instrumentalization of cultural artefacts in the visualization of a world culture rather imposes the divorce of culture from its bases in individual experience, suggesting particular fixed cultural identities as represented by the material on display. Synthesizing diverse artefacts and ways of life into a unified visual narrative of civilization's progress thus effectively denies both meaningful differences between communities and any change within them, in favour of the universal ideal.

As Alain Finkielkraut observes, a notion like world culture can have ramifications quite different from the emancipatory and peace-building intent which animated it:

At the same time in effect we [Westerners] granted the “other” man his culture, we robbed him of his liberty. His very name vanished into the name of the community. He became nothing more than an interchangeable unit in a whole class of cultural beings. He was supposed to be receiving an unconditional acceptance; in fact he was being denied any margin of manoeuvre, any means of escape.Footnote 39

The visualization of world culture may have been an effort to circumvent the dangerous nationalisms seen to be at the root of conflict and to underpin the promotion of the Universal Declaration. Its upshot, however, was not necessarily the construction of peace in the minds of men, but the questionable appropriation and instrumentalization of culture. Moreover, not only do cultural identities become fixed, they are also reduced to their visual aspects. In transforming diverse artefacts from diverse cultures into a catalogue of analogous images, rather than establishing a global museum, this photographic project ends up undermining its own enterprise. The album does not simply effect the “mass distribution” of the original exhibition; the artefacts themselves undergo a transformation in being reproduced as and reduced to images. In 1961, Hannah Arendt decried a crisis of culture precipitated by the advent of mass society. She criticized in particular the efforts of “a special kind of intellectuals, often well read and well informed, whose sole function is to organize, disseminate, and change cultural objects in order to persuade the masses that Hamlet can be as entertaining as My Fair Lady, and perhaps educational as well”.Footnote 40 The resultant cultural products, Arendt feared, amounted not to education, but to the takeover by the central attitude of mass society—“the attitude of consumption”—and the production of “mass entertainment, feeding on the cultural objects of the world”.Footnote 41 Circulated around the world a decade previously, UNESCO's Human Rights Exhibition Album exemplifies this crisis, realizing what Arendt termed the ransacking of culture, in pursuit of a visual reference point for a global imagined community which might underpin promotion of the Universal Declaration.

At the same time, however, explicit discussion within the organization was moving away from the universalism of internationalist ideals like world culture. This can be seen in the contrasting speeches given by the outgoing and incoming directors-general during UNESCO's Annual General Conference in December 1948 (at which the resolution to promote the Universal Declaration was adopted).Footnote 42 In his retirement address, Julian Huxley (a former trustee of the Council for Education in World Citizenship) spoke of the “One World of the human mind”.Footnote 43 He asked delegates, “Have you looked at your problems from a Unesco Angle—that is to say not merely as national problems but as part of a single world problem?”Footnote 44 In contrast the incoming head of the organization, Jaime Torres Bodet (a former minister for education for Mexico), was more pessimistic and less didactic, advocating a pluralist approach:

We can no longer accept, unmodified, the idea of man and of culture that classical humanism bequeathed. . . . Classical humanism was at one time restricted to the Mediterranean region. Modern humanism must know no frontiers. It is Unesco's supreme task to help to bring this new type of humanism to birth.Footnote 45

Rather than world culture, Torres Bodet spoke in more measured terms of “international understanding” and of the “friendly association between cultures in an atmosphere of peace”.Footnote 46 In UNESCO's first decade, there was a plurality of internationalist positions held by those supportive of the organization, from the hardline one-worlders to more pragmatic individuals who looked for a community of nations. The organization's movement along this spectrum, however, was at odds with the implications of the photographic imagery it mobilized in its work to establish an international public sphere. The Human Rights Exhibition Album told a unidirectional narrative of the struggle for recognition of human rights in which the privileging of urban space suggests a Western-centred notion of progress and diverse cultures are reduced to static and equivalent parts of a homogeneous world culture.

WORLD CITIZENSHIP, YOUTH AND EDUCATION: CITIZENS OF TOMORROW

A close connection was drawn in the discourse of postwar reconstruction between a secure global peace and the education of the individual. This issue was a key motivation in establishing UNESCO, prompting the original Conference of Allied Ministers of Education which first met in London on 16 November 1942 and from which the organization resulted. In February 1947, UNESCO hosted a meeting of international voluntary organizations, the Temporary International Council for Education Reconstruction (TICER). By the end of the 1940s, this effort towards educational reconstruction encompassed over two hundred organizations, and had raised and distributed $100 million.Footnote 47 Predictably, in the publications which accompanied this effort, photographs of children were prominent, and the postwar city was a setting particularly rich with significance. As Tara Zahra has noted, “Children were at the symbolic heart of efforts to reconstruct Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War.”Footnote 48 UNESCO's campaigns in the postwar decade to raise funds and awareness regarding educational reconstruction and the plight of children in war-devastated countries demonstrate a very different style of address from the intellectual appeal made by the Human Rights Exhibition Album—one founded on identification through the figure of the face, rather than a shared world culture.

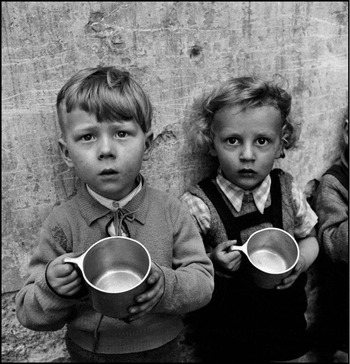

The most important example of such imagery, owing to its wide circulation, is a set of photographs commissioned by UNESCO from photographer and Magnum Photos founder member David (“Chim”) Seymour and published as Children of Europe.Footnote 49 Comprising fifty photographs with trilingual captions, three versions of Children of Europe were published with a title and preface in English (Fig. 6), French and Spanish. The photographs are populated by children whose frank stares and desperate situations set the tone for this short photo-book, ten thousand copies of which had been produced by 1951.Footnote 50 Seymour's photographs were also used in Courier, in other UNESCO publications and in UNESCO-sponsored exhibitions of the period.Footnote 51 The first image in the original photo-book (Fig. 7) shows three boys walking along a road bounded on both sides by rubble. Behind them, dominating the top two-thirds of the image, are the jagged walls of war-ruined houses. Like the image's composition, the trilingual caption emphasizes the devastated urban setting. It reads tersely, “Millions of children first knew life amid death and destruction.” In another image, two children turn their empty cups to the camera questioningly (Fig. 8). The eyes of the children stare out from the book's pages with imploring expressions which give the impression of meeting the viewer's gaze uncompromisingly. Through both the ruined setting and the children's faces, the images make a direct, emotional appeal, evoking sympathy and inviting the audience to identify with the children pictured. Captions in the first person plural echo the address of the images, commanding the viewer's attention by suggesting relationships of responsibility between the children (“we”) and the viewer (“you”). One reads, “Orphaned, abandoned and bombed out . . . we struggle to live in the wreckage you have left us.” The emotional appeal of the children's faces is also seconded by the book's preface. Described as a letter written by a seventeen-year-old, the text details the experience and the extent of the deprivation suffered by an estimated thirteen million children in war-devastated countries of the postwar period.Footnote 52 The suggestion of a series of one-to-one encounters (through image and text) works to forge a sense of community with attendant notions of responsibility, helping fulfil the photo-book's function as a fundraising document.Footnote 53

Fig. 6. Two young destitute children. Cover of David Seymour, Children of Europe (Paris, 1949). Photographer: David Seymour. Used by permission of Magnum Photos. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland. See http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001332/133216eb.pdf.

Fig. 7. Three boys walking down a street lined with ruined buildings (Monte Cassino). Trilingual caption in French, English and Spanish: “Millions of children first knew life amongst death and destruction.” Seymour, Children of Europe, n.p. Photographer: David Seymour. Reproduced by permission of Magnum Photos.

Fig. 8. Two children holding empty cups up to the camera (Vienna). Trilingual caption: “Milk for the children sometimes, but they need it every day.” Seymour, Children of Europe, n.p. Photographer: David Seymour. Reproduced by permission of Magnum Photos.

In addition to this emotional appeal, the images of children had two important characteristics. First, the child is framed as a symbol of the future. Despite the entreating expressions and desperate circumstances pictured, a positive tone ultimately prevails. Following a visual adumbration of the problems, the imagery turns towards a positive look at solutions. Pictures of classes held under a tree or in the shadow of a burnt-out facade illustrate the state of makeshift schooling (Fig. 9), while other photographs depict children themselves engaged in the work of rebuilding schools. The privileged solution to the problem of youth postwar is education. The final caption appears between a photograph of children dancing on the banks of a river across from new high-rise housing blocks and children's drawings on the back cover. It reads, “Share your world with us. We too shall be grown-up people in a few years. Do not abandon us a second time and make us lose forever our faith in the ideals for which you fought.” Thus Children of Europe charts a transition of the ruined cityscapes, from manifestations of past trauma to sites of potential. Against this symbolic backdrop, children represent the opportunity for a peaceful postwar future.

Second, the youth question is represented as being outside, above or somehow disassociated from a given nation. Crucially, the attempt to establish relationships between viewer and viewed is based on a one-to-one encounter, not mediated by associations of nation and nationality. The children are never identified solely as citizens of a particular nation. Rather, they are pictured undergoing a common difficult experience, somehow outside national boundaries. The effort to universalize the image of children as symbols of the future disconnected from a particular nation promotes an internationalism predicated on recognition or identification between individuals, simultaneously shelving national concerns or histories and working to replace the difficult symbolism of war-damaged urban space with a redemptive character and a sense of possibility.

Fig. 9. Two photographs: children attend a lesson outside (“Children's Town”, Hajdúhadház, Hungary) and children link hands and play in front of a background of ruins. Seymour, Children of Europe, n.p. (penultimate double-page spread). Photographer: David Seymour. Used by permission of Magnum Photos. Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

This photographic representation of children's postwar situation chimes with the concurrent discussion of world citizenship within UNESCO forums and publications. This idea was posited as a key tenet of education and also an attitude to be fostered amongst UNESCO's audiences. World citizenship was viewed as a means of ensuring peace through social justice and entailed the nurturing of the individual so that he or she may share in and contribute to society's achievements. A brief manifesto in Courier proclaimed the internationalist and universalizing character of this ideal: “A world citizen is loyal to his community and to his country, but his primary loyalty is to humanity.”Footnote 54 Seeking likewise to deconstruct or overwrite associations of nationalism and nationality which defined both the wartime period and the tensions of the Cold War, UNESCO publications drew on a mode of photography which could evoke a general sense of community through images of specific individuals—that is, one which effectively deterritorialized the individual to evoke the idea of a universal citizenry composed of individual world citizens, as opposed to citizens of different nations. The denationalized and future-focused framing of youth is captured in the theme of a special edition of Photo-Monde, published in 1956 and sponsored by UNESCO: “Today's Children . . . Tomorrow's Citizens”.Footnote 55 The idea of being a citizen of tomorrow posited by the title neatly divorced citizenship from national association and linked the image of the child with the idea of the future.

The cover of a special edition of Courier published in December 1956 to celebrate the organization's ten-year anniversary provides another striking example of the visualization of internationalized youth (Fig. 10). It depicts three children standing in front of a large globe outside the Babson Institute of Business Administration in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Curved along one of the lines of longitude is the title, “1946–1956: Ten Years of UNESCO”.Footnote 56 The photograph suggests a relation between the youth question and the international community through the straightforward juxtaposition of the one (symbolized by the three children) with the other (symbolized by the globe). It also offers a vision of children outside the confines of one nation or another. They are literally removed from any particular geographic—and hence national—ties. Above all, the photograph works to transfer positive associations from the gaze of the children to the internationalist perspective. The children (representing hope, potential and the future) have the much-vaunted global perspective, while the person picking up the magazine also sees the world in its entirety. In that shared object of vision is the possibility of a transfer of positive associations which the children carry to the global perspective that the viewer shares.Footnote 57

Fig. 10. Children and globe at Babson Institute of Business Administration, Wellesley, MA. Cover of UNESCO Courier, 12 (1956). Photographer: Roy F. Whitehouse. Reprinted from UNESCO Courier. Reproduced courtesy of the Babson College Archives. See http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0006/000689/068941eo.pdf.

As the cover of the tenth-anniversary issue of UNESCO's flagship publication, Figure 10 demonstrates the importance placed by UNESCO on the capacities of photography to visualize the organization's utopian ambitions through a strategy of mass communication. Likewise, a sense of excitement about the capacities of the camera to achieve an internationalist vision of youth was evident when Seymour's images were reproduced in Courier. The accompanying text foregrounded the role of the photographer and the medium through such interjections as, “A photographer highlights the drama of post-war youngsters” and “Through the eye of the camera”.Footnote 58 Notwithstanding such enthusiasm, this mode of image-making had ideological implications beyond those aims. The European children in Seymour's volume and the American children on the cover of Courier present a partial view of the world's youth. As in the Human Rights Exhibition Album, there is a Western- or Euro-centric dimension to the representations used in the campaigns regarding educational reconstruction. Despite the manner in which questions of youth and education are placed on an international footing, these publications existed in a world of very specific relations between specific nation states. The internationalist point of view promoted by UNESCO through the photography of children is indelibly marked by prewar history (colonialism) and postwar circumstances (the dominance of transatlantic nations in the field of cultural production). The list of photographers is dominated by Europeans, for instance, while the languages of publication are the three main colonial languages. Moreover, white children in urban settings dominate. Visualization of questions of youth and education thus entailed a privileging or universalizing of Western and urban modes of existence. Again, internationalism spills over into universalism and photography is implicated in the process.

The image of the child used in UNESCO publications of the time fulfilled an important function by acting as a mediator of the organization's aims.Footnote 59 Encouraging viewers’ emotional engagement, the visualization of UNESCO's programme through the image of the child's face works to elicit a sense of community or obligation and thereby encourage support. These widely circulated images in the concerned mode thus constituted the face of UNESCO; or, perhaps more accurately, these photographs epitomized Huxley's vaunted UNESCO point of view. They invited the viewer to acknowledge the child and recognize their plight, and in doing so the images worked to recruit people to a way of looking at and thinking about youth in the postwar period as a pressing and personalized concern. Children of Europe created an identity for UNESCO by performing a concerned gaze with which the organization could be associated. Albeit quite distinct from the logo of the universalized Greek temple which looked to the past, Seymour's future-focused photographs constituted another public image of UNESCO in the conception and execution of which photographic representation was integral. Like the young girl on the cover of the first photo-magazine-format issue of Courier, the children captured by Seymour as published in Children of Europe have become symbols rather than citizens. They are symbolic of need; they are a means to elicit funds; they facilitate the performance of the concerned gaze of UNESCO. But they are not themselves. Even the letter which served as preface, one suspects, is ghostwritten.

Moreover, while the emotional appeal of the images is direct, the role that the viewer can play in righting the injustice depicted is far from obvious. The implied idea of world citizenship as a means to forge a global imaged community is problematic. Citizenship suggests a set of rights assured by a sovereign state or other governmental body in exchange for the satisfaction of certain obligations on the part of the citizen. However, the discourse of world citizenship provides no clear framework for such a form of social justice. (What and how are obligations to be discharged? Who or what is to secure rights?) It was an internationalist and universalizing ideal without secure grounding in the new world order represented by the UN. As a member-state organization, the rhetoric of this visual culture was also at odds with the political structure of UNESCO. Certainly, wartime education debates were the genesis of the organization's creation. Following the establishment of UNESCO, many of the National Committees which formed the bridge between the organization in Paris and the governments of the various member states were affiliated to government departments of education. However, the inspirational vision of an internationalist future articulated in wartime met certain real-world obstacles in the first postwar years. It was not until UNESCO's General Conference in 1949, for instance, that member states decided to “extend parts of UNESCO's programme to Germany and Japan”.Footnote 60 West Germany did not become a UNESCO member state until 1951. The Soviet Union did not join UNESCO until 1954, owing to unease about press freedoms which the organization promoted. This exclusion of former Axis nations (and the reticence of Allied ones) existed alongside the organization's promotion of world citizenship through the use of concerned photography. The emphasis on the internationalized youth of tomorrow was a reaction to a moment of increasing tension between polarized nations, but it was more the visual expression of a desire than it was the depiction of a reality. The viewing of youth as an international concern on which the future depended was projected through UNESCO publications as a cornerstone of the task of forging peace in the minds of men, notwithstanding the contradictions in such an image for a member-state organization operating in a Cold War context.

* * *

UNESCO had numerous critics in its first decade. Novelist Hermann Hesse was sceptical concerning the value of increased understanding between nations, since French and German intellectuals’ understanding of each other's culture had had no positive bearing on the course of peace.Footnote 61 Academic Hans Morgenthau was dismissive of UNESCO's efforts in his study of international politics first published in 1948. Highlighting that Americans read Dostoyevsky and Russian theatres staged Shakespeare, he considered culture incidental to international cooperation: “The problem of world community is a moral and political and not an intellectual and esthetic one. The world community is a community of moral judgments and political actions, not of intellectual endowments and esthetic appreciations.”Footnote 62 Examination of UNESCO's use of photographic representation, however, highlights the inadequate seriousness with which a critique like Morgenthau's takes the task of cultural analysis. Shaped by and promoted through visual material, the internationalist ideals of world culture and world citizenship were moral judgements against nationalism, held responsible for the death and destruction of the past world war; they were intended as political actions against the threat of a future war which could be avoided by redefining what the international community consisted in.

As former colonized nations achieved independence and UNESCO membership grew throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the one-world rhetoric was replaced by talk of mutual or intercultural understanding. References to world culture or world citizenship became less prominent, as did other terms not explicitly addressed here such as world society and world understanding. Today, of all the initiatives promoted by UNESCO it is the World Heritage List chronicling sites of cultural or natural importance that is central to the organization's public image. This discourse of world heritage is less closely aligned with that of human rights than was the concept of world culture in UNESCO's postwar exhibition album. Moreover, the unofficial discourse of human rights has now overtaken the official one, with NGOs working to communicate with a global public and put pressure on governments and international organizations like the UN. Samuel Moyn has charted this movement from the postwar primacy of national self-determination to recognition that national sovereignty has to be intruded on to secure human rights. This “move from the politics of the state to the morality of the globe” has seen NGOs help redefine rights talk, aligning it much more closely with the sort of humanitarian initiative represented by the reconstruction effort with which Children of Europe was associated.Footnote 63 Arguably, to fully account for the course and impact of the human rights agenda since the Universal Declaration in 1948, it would be necessary to trace its relation to genres of image-making. As Susie Linfield suggests, “photography has been central to fostering the idea that the individual citizen and the ‘international community,’ not the nation-state, is the final arbiter of human-rights crimes. It's impossible to imagine transnational groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, or Doctors without Borders in the pre-photographic age”.Footnote 64 The uses of photographic imagery by UNESCO and other organizations operating on an international stage emphasize that a cultural practice like photography—contrary to Morgenthau's assertion—is not incidental; it can play a formative role in shaping debate in the public sphere.

In its early years, photography held for UNESCO the promise of a visual culture that could overcome barriers of nation, language and even illiteracy. The conception of photography as a universal language was woven through the objectives and the efforts of the organization. However, as discussed here, such an instrumentalization of photography was not ideologically innocent. Emerging from a period of political and personal turmoil defined by the First and Second World Wars, into the tensions of the Cold War and the violent conflicts of decolonization, the manner in which Europe was presented in international debates as the birthplace and long-time home of democracy is conspicuous, to say the least. This essay has analysed how the campaigning work of UNESCO in its early years was underpinned by what Mark Mazower has termed “a sense of European civilizational superiority”.Footnote 65 A comprehensive history of UNESCO and visual culture in the first postwar decade would have to cast the net wider, including topics such as the promotion by UNESCO of art in its utopian project, the debate about visual aids in primary education, and the use of film and film strips in the many public-information campaigns. What has been prioritized here is analysis of the vital part played by the medium in shaping the aims of UNESCO and animating its campaigns, which resulted from the conception of photography as a universal language. What has been argued is that photography was neither a transparent window nor an impassive mirror; the marshalling of photographs of artefacts, individuals and architecture was less the valuable use of a universal language suited to the needs of UNESCO than the universalizing of certain values in the pursuit of UNESCO's effort to build peace.

This essay is not intended as an iconoclastic attack on internationalism, on UNESCO, on human rights or on the importance of children in post-conflict situations. The achievements of the postwar period (the effort towards educational reconstruction, the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) should not necessarily be undermined by revelation of various prejudices attendant on UNESCO's early work. Questioning the latter is not synonymous with rejecting the former. Nor is this article a denial of the social and political purpose that photography can fulfil. The work of Ariella Azoulay offers a different model for examining the photograph as a historic document from the one undertaken here. Azoulay aims to resist “the abstraction and naturalization of the visible”, working to ascertain the conditions under which a photograph is taken “by cross-referencing the information that is registered in it with extra-photographic information” to understand the social and political context in which photography as a practice is utilized.Footnote 66 I have sought, instead, to examine that process by which photographs of artefacts and individuals can become decontextualized, fixed images or abstract symbols. Emphasizing “the civil potential of photography” and the importance of “taking photography seriously as an encounter”, Azoulay also emphasizes the political responsibility of the viewer.Footnote 67 Without denying the intersubjective encounter offered by the photograph of an individual, I have sought rather to evaluate the ideological implications of the address by UNESCO's image-over-text publications. This is not to repudiate the social and political recognition demanded by the viewing of individuals in photographs, but rather to analyse the manner in which UNESCO's historically constituted visual projects framed people and cultures in ways that worked to sideline or frustrate the social and political demands that Azoulay underlines.

From the standpoint of intellectual history, it is necessary to examine the permeation of internationalist thinking with questions of vision in the postwar world, and to understand the presumption of a correct way of seeing the problems of human welfare which underpinned the postwar deployment of mass communication. Explicit debate within UNESCO became sensitized to these issues early on, as evidenced by the contrast between Huxley's “One World of the human mind” and Torres Bodet's broader conception of “international understanding”. A unified or uniform internationalism did not exist within the organization in its first decade. Rather, UNESCO grappled with the overlapping approaches to internationalism in relation to the creation of an international public sphere, and the persistence of conflict in the postwar moment. Nonetheless, the effort to create such a public sphere was a visual as well as a verbal one. Attention must be paid to the visual culture of the period and its capacity to influence ideas and shape debate.