Introduction

As a movement, Russian cosmism (Russky kosmizm) emerged in Russia in the early twentieth century, a time when an idealistic belief in the omnipotence of science was spreading fast among scholars, scientists, writers, political elites, and the general public. Marked by ground-breaking scientific discoveries such as radioactivity, superconductivity, the theory of special relativity, continental drifts, the discovery of new galaxies, and so on, not to mention break-neck developments in technology, this period also saw social unrest and revolutions that swept across Europe and beyond. This included, of course, the two Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 which ushered in Russian society's transition to industrialized capitalism and socialism. On the waves of the scientific, cultural, and social revolutions that opened up new horizons and expanded the universe beyond all recognition, Russian cosmism emerged to deal with a host of scientific-philosophical questions. Those concerning the cosmos and the fate of technologically advancing humankind within it are of central importance in this article.

The relationship of Russian cosmism to the mainstream scientific community generally, and the Russian state in particular, was always fraught with controversy. Despite the movement's claim to be a ‘science’, from the late 1920s, when the Soviet state imposed its strictly materialistic understanding of science, many of the ideas promulgated by Russian cosmism—especially those related to the occult, the resurrection of the dead, and ‘intelligent’ cosmic layers and waves—were incompatible with the Soviet doctrine and were denied. However, some of the movement's less controversial ideas concerning scientific progress were incorporated into Soviet philosophy, art, and literature. Denied its ‘proper scientific’ status and driven underground, Russian cosmism as a whole came to constitute what the Soviet philosopher Vladimir Filatov calls an ‘alternative science’.Footnote 1 It operated in opposition to mainstream Soviet science, or Marxism-Leninism, which purported to explain everything by constructing a ‘super-science’, as it were, out of all legitimate disciplines.Footnote 2 One can argue that this was symptomatic of wider developments that took place in the Soviet Union when all political and economic power became centralized in the Kremlin. In this climate, no rivals or alternatives were tolerated. Banned for most of the Soviet period, Russian cosmism, however, survived in the shadows in many guises: in the secretive healing practices of psychics who used cosmic energies, in stories about UFO sightings, in underground circles discussing the paranormal, in samizdat manuscripts, in artworks, and in the names of the movement's founding fathers who happened to be the leading philosophers of the Soviet space exploration project.

It was not until the beginning of perestroika, marked by decentralization, relaxation of religious beliefs, and the consequent repudiation of Marxism-Leninism as a dominant scientific paradigm, that Russian cosmism re-emerged in all its occult diversity. Not only did it aim to reclaim its status but also to explain the essence of everything by uniting science with dukhovnost’.

The term dukhovnost’ derives from dukh meaning ‘soul’ and is often translated into English as ‘spirituality’, but in Russian this term has several overlapping meanings. First, it connotes that which is intangible or invisible, that is, in our psyche or thoughts. Hence the expression dukhovnaya kul'tura is translated into English as ‘intangible culture’ (which includes folklore, music, and so on). Second, dukhovnost’ implies one's eagerness to learn the truth about the workings of the universe and to live accordingly. Such people are said to be interested in existential questions such as ‘Who am I?’, ‘What is the meaning of life?’, and ‘How should I live?’ This search does not necessarily lead to God. Hence a dukhovnyi chelovek is not necessarily a religious person but one who thinks about existential questions, seeks the truth, and wants to improve themselves. Its third meaning is religious—it connotes a ‘moral’ life that is believed to be guided by the Holy Spirit.

Unlike spiritual movements that emphasize inner well-being and passive commemoration, Russian cosmism, which positions itself as dukhovnaya nauka (which can be translated as ‘science of the truth, of soul-searching’), puts a strong emphasis on thought as a call for action to radically transform humanity on a global scale.Footnote 3 Russian cosmism's ambition to provide answers to questions about all that is ‘out there’, both visible and invisible, by uniting all ‘legitimate’ explanatory methods, is nothing new in Russia, given the Soviet experience of trying to establish a single super-science that purported to be capable of explaining everything there is. In fact, Russian cosmism's over-arching ambition and its ‘call for action’ predate those of Soviet ideology, or science, and it is still an open question as to the extent to which the former influenced the latter. It is worth noting that some of the most prominent early Soviet scientists, as will be discussed, were cosmists. The story of Russian cosmism—with its persecutions, hidings, transformations, survival, and eventual proliferation—is as much a story of science in Russia in general as it is a tale about this particular movement.

This article is about Russian cosmism and its current status in Kalmykia, a small Buddhist republic in southwest Russia. Today Russian cosmism is an all-Russian cultural-philosophical movement engaged in all areas, from icon painting to yoga, to Kantian philosophy, to ethnic questions, to the ozone layer.Footnote 4 It combines various elements of theosophy, philosophy, poetry, theories of evolution and energy, astrology, cosmology, ecology, and even science fiction. In this article I will focus upon its more central, cosmic topics—those related to outer space, cosmic energies, and alien visitations—as well as local responses to these ideas in Kalmykia. In particular, I will discuss how Russian cosmism has been perceived and practised by some high-ranking politicians, intellectuals, and religious practitioners in this part of Russia.

Russian cosmism, as many cosmists contend, cannot be described as a religion in the conventional sense of this term—hence it lacks the concepts of hell, paradise, angels, divine punishment. Its dukhovnost’ component, or ceaseless search for the ultimate cosmic truth and morality (which at the same time legitimizes mystery and the idea of the ‘unknown’), attracts ‘soul-searching’ people who are not difficult to find among politicians, artists, poets, religious practitioners, or simply curious individuals. Russia has a long tradition of ideas about ‘soul-searching’ and an ‘eternal spiritual journey’ as attested to by the works of great Russian writers, artists, and musicians such as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Rachmaninov, and others. Encompassing a wide variety of research concerning humanity and its dukhovnyi well-being, Russian cosmism employs a host of ways in which to analyse reality. Having developed, as Kurakina points out, various levels of attaining sensual reality through ‘biocosmism’, ‘energocosmism’, ‘anthropocosmism’, ‘astrocosmism’, ‘teocosmism’, ‘sofiocosmism’, ‘hierarchocosmism’, and ‘sociocosmism’,Footnote 5 Russian cosmism offers a planetarian concept to address the global threats and challenges that humanity faces, including economic, political, and spiritual crises; ecological catastrophes; and terrorism.Footnote 6 Despite its ambition to create a comprehensive ‘scientific’ paradigm that reconciles modern science with dukhovnost’, the movement does not present a unified system of ideas, theories, or methods. In fact, owing to its expansive and eclectic character, many of the movement's adherents do not agree with each other on a host of issues, with some even arguing that cosmism is myshlenie, ‘a way of thinking’, and not dvizhenie, ‘a movement’. It is also prone to generate bizarre offshoots, some of which will be discussed later in the context of Kalmykia.Footnote 7

Aiming to engage with the topic of Russian cosmism within the narrow context of stories of alien visitations and cosmic energies, this article opens with an account of the first reports of alien abductions and visitations in Kalmykia, then discusses the founding fathers of Russian cosmism, Eurasianism as a theory of cosmic energies, UFO sightings and the revival of Russian cosmism in Russia, and concludes with cosmism in post-Soviet Kalmykia.

First alien abductions and visitations in Kalmykia

In Moscow in 1997 a high-profile politician shocked the political establishment and the whole of Russia with the incredible claim that he had been abducted by aliens. Here is his account of the abduction as told to the popular Channel One Russian television host Vladimir Pozner on 26 April 2010:

In September 1997 I was planning to go back to Kalmykia and in the evening returned to my flat, it is on the Leontevsky Alley, here in Moscow. That evening I read a newspaper, watched TV, went to bed. And later on, perhaps, I had already fallen asleep and felt that the balcony opened and somebody was calling me. I approached and saw a half transparent tube. I went into the tube and saw humanoids in yellow spacesuits. I am often asked, ‘What language did you speak?’ Perhaps telepathically, for I felt an oxygen shortage […] Then they showed me around the spaceship. They even told me, ‘We'll have to take samples from one planet.’ Then we had a conversation. [I asked] ‘Why don't you appear on live channels and tell that you are here? Look, [you should] communicate with us.’ [They] replied that, ‘We are not ready for the contact’, and then returned me [to Earth].

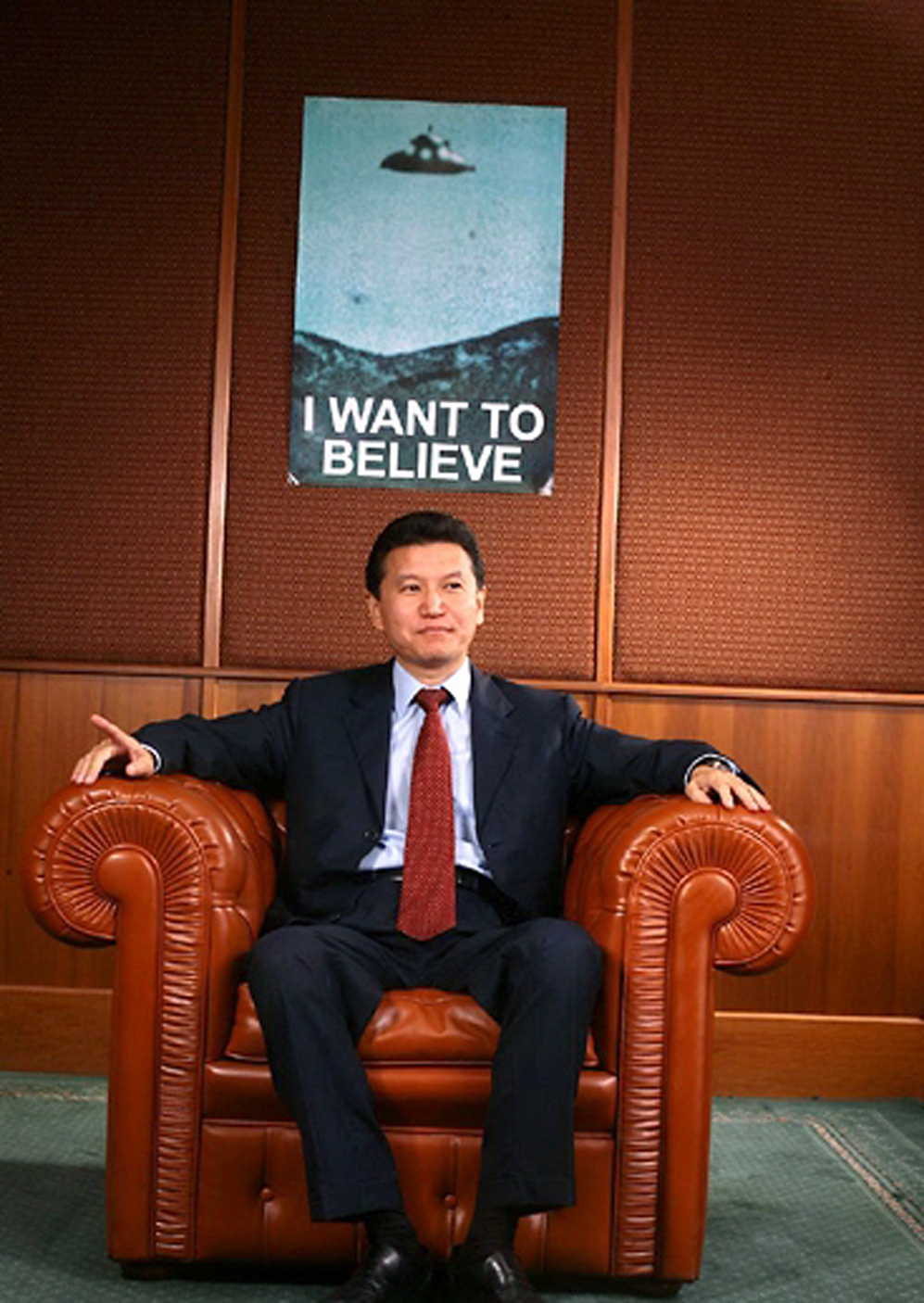

The victim of the abduction was Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, the eccentric president of Kalmykia (see Figure 1). The Kalmyks, numbering fewer than 150,000 and the titular population of the republic, are a Buddhist people of Oirat-Mongol origin. They settled in the region of the Lower Volga and established the Kalmyk Khanate at the beginning of the seventeenth century, having migrated from Dzungaria (today the northern half of China's Xinjiang province, western Mongolia, and eastern Kazakhstan). Having served as vassals to the tsar, the Kalmyks were soon incorporated into Russia following the abolition of the Khanate in 1771. According to Ilyumzhinov, following the incident, he approached Russia's president Boris Yeltsin and was advised to keep the story low profile and carry on working. Despite his superior's advice, Ilyumzhinov relayed his story to Russian and foreign journalists, including those from The Independent and The Guardian in the United Kingdom and TIME magazine in the United States. When Ilyumzhinov appeared on Pozner's television programme in April 2010, a concerned Russian MP, Andrei Lebedev, wrote a letter to the then-president of Russia Dmitry Medvedev urging him to investigate Ilyumzhinov's claims and look into the possibility that he had revealed state secrets to the aliens. The letter also enquired about official guidelines for what high-ranking officials should do if they were contacted by aliens. In 2012 Medvedev himself made the following strange comments to a Russian reporter who asked him about aliens, which was not broadcast on state-controlled TV channels but found its way onto YouTube:

I am telling you this the first and the last time. Along with the briefcase with nuclear codes, the president of the country [Russia] is given a special top-secret folder. This folder in its entirety contains information about aliens who visited our planet.Footnote 8

Although many Russian viewers regarded it as a joke and mocked the president, many cosmists took Medvedev's comments at face value.

Figure 1. Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, former president of Kalmykia and president of the World Chess Federation (FIDE).

The tale of Ilyumzhinov's historical abduction did not occur out of the blue. Prior to this, one evening in May 1992 an extraordinary thing happened in the eighth micro-district of Elista, the capital of Kalmykia, which was witnessed by several people. One of them was Valery Dorzhinov, a Kalmyk man in his mid-thirties, a construction worker by profession. Here is his account:

It was the third week of May, 1992, Friday. It was calm. May was nearing its end. I came home after the working day, changed my clothes, and looked into the kitchen. My wife was preparing dinner. While waiting for dinner, I laid down on the bed with a newspaper in my hand. From the open window came the voices of neighbours […] All of sudden my daughters—thirteen-year-old Tanya and seven-year-old Toma—rushed into the flat.

‘Papa, papa! Hurry up, let's go outside,’ called out Tanya, ‘There, aliens have arrived’.

‘Hurry up, hurry up! Quickly put on clothes and let's go, otherwise you'll miss them, they will fly away,’ my youngest was urging me.

Having put on a shirt, I rushed out of the flat into the street. Once on the street, I lifted my head and started looking for the alien guests. And above a five-storey residential house number 31, I saw a huge globe of yellowish-greenish-bluish colour. At that moment, the globe started moving away, gradually disappearing, and in six or seven minutes it completely disappeared. I could only see it off with my eyes […] I turned to look at the reaction of my neighbours. They had already come to their senses from the shock and started a discussion […] I looked at my watch; it was 8:25 pm.Footnote 9

According to Dorzhinov's account, after this extraordinary event he began travelling with the aliens to different galaxies and receiving important information about the origin and the future of humanity. He shared his revelations with his friends and co-workers. This story would probably have been forgotten sooner or later, had Dorzhinov not begun publishing articles about his telepathic, intergalactic journeys and about imminent physical contact with the alien ancestors in the state-controlled newspaper Hal'mg Unn (Kalmyk Truth). The same year, he even wrote a best-seller entitled Visits to the Motherland of Ancestors.Footnote 10 Not surprisingly, excited citizens soon began sighting UFOs all over Kalmykia. Thus, in the article ‘Did the aliens visit us? It seems that thousands of people in Kalmykia witnessed UFOs’, the correspondents write:

In response to our article ‘In the night sky above Elista’ published on 2 June, all of a sudden our newspaper office was flooded with telephone calls from the readers. In order to process all the incoming information, our workers had to wait at the phone machine in turns. Being in a hurry to share what they saw, people phoned us not only from Elista but also from the remotest corners of Kalmykia. And this in spite of the high cost of intercity calls! Thank you, dear friends! From all the stories we have recorded so far, we tried to select the most, in our view, interesting and colourful ones.Footnote 11

The article published 25 eyewitness accounts of UFOs. This mass excitement, no doubt induced to a large extent by Dorzhinov's sensational publications, affected not only ordinary citizens but the leaders of the Republic as well. Having discussed the situation with Dorzhinov, on 11 November 1995, in an interview with Izvestiya, President Ilyumzhinov announced that the world was on the eve of meeting with aliens. Two years later, his prophecy was fulfilled and he was abducted by extra-terrestrials while on a business trip in Moscow.

Founding fathers of Russian cosmism

Ideas about the existence of extra-terrestrial civilizations and the connection of humanity with outer space have long been a topic of discussion among prominent Soviet philosophers and scientists associated with Russian cosmism. Concerned about the fate of humankind in the cosmos, Hagemeister notes that this movement's particularity is its holistic and anthropocentric view of the universe, in which human beings appear destined to become a decisive force in cosmic evolution, that is, a source of collective cosmic self-consciousness, active agent, and potential perfecter.Footnote 12 Filled with an endless variety of life forms, evolution in the universe is dependent upon human action and, by failing to fulfil its fated cosmic role, humankind dooms the world, as well as itself, to catastrophe.

Cosmism, which reflects an idealistic belief in science and the power of humankind to tame and change nature, has deeper and older roots in traditional folk cosmology and the occult. As in folk cosmology, cosmism offers its own explanation of the workings of the universe and astral objects from a perspective in which humans are of central importance. Both traditions are also moralistic in the sense that they teach about morality and duty. Although both assume the world to be a rational entity, they differ. Whereas in folk cosmologies supernatural beings—gods, angels, spirits, and demons—control everything (and demand offerings, rituals of subordination, and so on), in cosmism these supernatural powers are replaced by physical laws, cosmic energies, vibrations, extra-terrestrial beings, and human intellect that render the world a meaningful, interconnected, and controllable place. Since, according to cosmism's mechanistic vision, there is no divine plan for saving the universe, cosmists acknowledge the threat of humanity's self-destruction and strive to define the role of humankind in this profane cosmos. By appointing itself the ‘perfecter of the universe’ and endowing itself with powers of creation and destruction, humanity—whose ‘cosmic duty’ it is to pursue scientific progress by eradicating disease, freeing itself from biological limitations, and attaining immortality—takes up the role ascribed in folk cosmologies to gods. By worshipping humanity and its science (instead of gods), cosmism is essentially a humanistic movement. Hence, according to cosmism, it is not gods but human experiences that endow the cosmos with meaning.

This is not to say that cosmism is a science, as the term is generally understood, for it does not utilize experimental methodology (involving control groups, equipment, and the like) and its underlying belief in the omnipotence of science and technology, as Hagemeister points out, is rooted in the idea of the magic power of occult knowledge. The cosmist idea of the realization of immortality and the revival of the dead, with the help of science, for example, has a long occult and Gnostic heritage, aside from the fact that the conceptions of the cosmists contain theosophic and pan-psychic influences.Footnote 13

Although many cosmists trace the genealogy of cosmic views to Russian sources—hence cosmism's self-propagation as otechestvenny or a ‘domestic, patriotic’ movement—during its formative years in the early twentieth century, the movement was influenced by many foreign sources, including the theosophic writings of Madame Blavatsky and her followers. These were translated into Russian by the Russian Theosophic Society based in Kaluga, a provincial town that happened to be the place where some of the early cosmists lived. No wonder then that the main theosophic tenets—including its vision to create a universal brotherhood of humanity, encouragement to study both science and spirituality/religions, exploration of unexplained laws and powers, speculations about the latent human abilities, and so on—were, in one form or another, incorporated into cosmist ways of thinking and practices. But, most importantly, theosophy's attempt to create a single science (by bridging the abyss between science and religion, between reason and faith) was in tune with cosmism's own mission to establish a universal science of the truth. According to cosmism, humans, who constitute a universal wholeness with the cosmos, are interconnected with each other and outer space via all sorts of intelligent energies, waves, and rays that permeate the very fabric of the universe. Many cosmists say that this claim is supported by modern quantum physics, astronomy, and related disciplines which they hold in high regard. In cosmists’ vision, through their power to create technology, humans are destined to attain omnipotence and control all biological as well as non-biological processes.

The fundamental ideas of Russian cosmism can be traced in the works of the founding fathers of the movement who were all polymaths with odd personalities, including Nikolai Fedorov, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (who held Madame Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine in high regard), Vladimir Vernadsky, and Alexandr Chizhevsky, on whose theories and speculations the post-Soviet cosmists build their explanatory models. As mentioned, these founders’ ideas should be understood in the context of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when great discoveries were made in many fields, the full significance of which was far from clear. Also, startling discoveries that are all but invisible to the human eye—including X-rays, wireless telegraphy, evolution unfolding over generations, galaxies spiralling millions of light years away, elements forming out of dying stars, and continents shifting over millions of years—only convinced the early cosmists that there is more to the world than the eye sees. This period, characterized by the growing cult of science in Russia, was also a time of diminishing belief in traditional religions, on the one hand, and increasing occultism, humanism (that is, worship of humanity), belief in telepathy, growing nationalism, and millennial intellectual outpourings, on the other, that sought rational explanation. The genius of the founding fathers of cosmism was that they offered seemingly rational, systematized answers to these diverse phenomena from a particular global, or cosmic, angle. In place of diminishing religious morality and God's authority, the movement also offered its own alternative—to build an ideal society and give the super-interconnected universe a new meaning by means of upgrading humanity to an immortal, godly status. Russian cosmism was born from these complex encounters and systematizing ideas in which the appeal to science and technology was its primary legitimizing strategy. In this sense, cosmism can be seen as a techno-philosophy or even a techno-religion in the making.

Nikolai Fedorov (1829–1903), regarded as the father of the Soviet space project and a precursor of transhumanism, was one of the most enigmatic cult figures in pre-revolutionary Russia. An illegitimate child of a Gagarin prince and an unknown neighbour, Fedorov, a deeply pious Orthodox Christian, grew up on both sides of the Russian social divide. After leaving his paternal home, he lived his life as an ascetic bachelor in a small room, wore the same shabby clothes in both winter and summer, ate poorly, and was easily mistaken for a tramp by strangers. Well-read, erudite, quarrelsome, and eccentric, he was known among a small but influential circle of Russian intellectuals, including the writer Nikolai Tolstoy. Having served as a school teacher in various locations in Central Russia, Fedorov worked for many years as a librarian in the Rumyantsev Museum (today the Russian State Library) where he met and took under his tutelage the young Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who came to study there. Opposed to the idea of the ownership of books and intellectual ideas, Fedorov rarely published during his lifetime, and what little he published was all written either anonymously or under pseudonyms. His main articles were published posthumously by his followers. Among Fedorov's ideas that were most ridiculed during his lifetime include the gradual prolongation of human life and his call for space travel.Footnote 14

Fedorov's main philosophical idea is as follows. Via its shared knowledge, scientific methods, and hard work, humanity is destined not only to design its own evolution but to actively change nature itself. By controlling ‘all atoms and molecules of the world’ and mastering ‘the forces of decay and fragmentation’, the human race will resurrect the dead, colonize the cosmos, and attain cosmic immortality, while changing the cosmos itself. While the role of science and technology is of paramount importance in Fedorov's vision, the most important ‘common task’ of humanity is to improve and perfect human intelligence and the body. In Fedorov's imagination the perfect future human is a self-nourishing, upgraded, immortal organism that has a perpetual mode of energy exchange with the environment. Fedorov's post-human is as different from us as we are from amoebas.

Fedorov's follower Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935), who is regarded as the founder of Soviet rocketry and astronautic theory, was the first to use the term ‘cosmic philosophy’ in Russia. His work influenced the leading Soviet spaceship builders Sergei Korolyov, Valentin Glushko, as well as cosmonauts, including Yury Gagarin. A recluse by nature and seen as a strange figure by the townsfolk, Tsiolkovsky spent most of his life in poverty and oblivion in his provincial town of Kaluga. During his lifetime, he published more than 90 works on aerodynamic and rocket theory, space travel, intelligent forces of the universe, and related subjects. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 was a turning point in his life. For his support of the Revolution, Tsiolkovsky was elected a member of the Socialist Academy in 1918 and in 1921 he was even granted a lifetime pension. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet propaganda machine turned the Kaluga eccentric, who happened to have a convenient proletarian background, into a national hero. In 1932 he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour, the highest civilian order of the USSR, and in 1967 a museum of the history of cosmonautics in Kaluga was named after him. Apart from his great accomplishments as a scientist, Tsiolkovsky speculated extensively about man's relationship to the cosmos and believed that humanity was spiritually and biologically connected to an outer space supposedly teeming with extra-terrestrial forms of life. He also defended the idea that all matter in the universe is not only interconnected but also has a mental aspect and sensibility.Footnote 15 In his article ‘Cosmic philosophy’ Tsiolkovsky writes:

At least a million billion planets have life and intelligence not less advanced than [that on] our planet […] In a thousand million years nothing imperfect, such as contemporary fauna, flora and human beings, will be existing on Earth. Only the best will remain, [and] our intelligence and its power will ultimately bring us [to this perfect state] […] On [other] developed, mature planets, evolution goes a million times faster than on Earth. By the way, this is regulated according to will: if a perfect population is needed—it is produced quickly and in any number. Visiting neighbouring infantile worlds with primitive life forms, they [i.e. developed civilizations] destroy them as painlessly as possible, and replace [them] with their own perfect species. Is it good, and not cruel? If it was not for their intervention, then the painful self-destruction of animals [on various planets in the universe] would have continued for millions of years, just as it is happening on Earth […] What does it mean? It means that in the cosmos there is no place for imperfect, suffering life: intelligent and advanced planets annihilate such life forms.Footnote 16

Tsiolkovsky, who called himself a biocosmist, referred to the cosmos as an ‘animal being’ (zhivotnoe) and saw it as an enormous, soul-endowed organism. He also promulgated the idea that all nations should become a single political system governed by the most advanced specimens of humanity.

Tsiolkovsky's idea of the conscious universe is complemented by the notion of ‘noosphere’ (noosfera) propounded by cosmist Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945), another intellectual giant of the early Soviet scientific establishment. He was a founder of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences and of ecology, a holistic discipline that studies interactions between organisms and their environment. Lectured by such great Russian minds as Dmitry Mendeleev and Alexander Butlerov at St Petersburg University, Vernadsky started his career as a mineralogist. Having acquired from these men the idea that the earth is in constant flux, its elements flowing and spiralling through its crust, he came to the realization that minerology, as a science of change and energy transfer, could connect cosmic history with the history of life itself.Footnote 17 Vernadsky argued that living organisms were the geological force that shaped Earth. According to him, Earth's biological life, or the biosphere (biosfera), developed from inanimate matter or, in other words, from the geosphere (geosfera). The biosphere is irreversibly entering into the third phase of the earth's development—the noosphere or the ‘sphere of intelligence’ (geosphere ⇒ biosphere ⇒ noosphere). Just as the emergence of life fundamentally changed the geosphere, the emergence of human civilization and powerful technology fundamentally transformed the biosphere into the noosphere. In this sense, by changing the earth's ecosystem, human cognition is a geological force that is ushering the planet into a new state of existence. The noosphere, according to Vernadsky, is a state in which humanity has total power over nature and is able to control the weather, change landscapes, and manage the evolution of all living organisms on a global scale. The chaotic evolution of life on earth will be replaced by an orderly one controlled by human intelligence. In Vernadsky's noospheric view, not only are such natural phenomena as ‘life’, ‘matter’, ‘radiation’, and ‘energy’ all interconnected, but humans, who are an important part of Earth's ecosystem, are responsible for all that is happening on the planet, including earthquakes, droughts, and hunger. Although arrested several times by Soviet secret services and suffering at their hands, in 1943 Vernadsky was awarded the Stalin Prize, the Soviet Union's state honour. Subsequently, his notion of the noosphere in its strictly materialist sense was successfully integrated into mainstream Soviet philosophy. In his foreword to Vernadsky's collection of articles, the influential Soviet academician Aleksandr Yanshin writes:

The teachings of V. I. Vernadsky about the ultimate transformation of the biosphere of Earth into […] the noosphere—a sphere rebuilt by collective intelligence and labour of humanity to satisfy all its needs—fits in its scientific-historical aspect the teachings of Marxism-Leninism about the ultimate construction of the communist society on Earth.Footnote 18

Apart from the official Soviet interpretation, the notion of ‘collective intelligence’ has several metaphysical meanings, one of the most popular being the idea that the noosphere is a higher ‘intelligent’ energetic field, or sphere, that floats around the earth and uploads human thoughts, memories, and other information. Some cosmists also argue that it is in the noosphere that ‘universal wisdom’ (razum) dwells. To use a modern computer metaphor, the noosphere can be imagined as a natural cloud technology that does not need computers and programmers to run. According to cosmism, people who are connected to this boundless source of intelligence and collective wisdom tend to be geniuses.

The biophysicist, painter, and poet Alexandr Chizhevsky (1897–1964) established another branch of cosmist enquiry and is regarded as the founder of solar-earth research. Throughout his life, Chizhevsky was noted not only for his many talents, but also for an exceptional sensitivity to the weather, vibrations, and fluctuations in the natural and social atmosphere. According to his autobiography, he had a constant sensation of fever, a burning as if of an inner sun, which he directed outwards in a never-ending passion to learn about society, including the study of solar and other cosmic influences on human behaviour.Footnote 19 Born in the town of Tsekhanovets, Chizhevsky spent his childhood and teenage years in Kaluga where he met Tsiolkovsky with whom he later worked in the Soviet experimental field of space biology (which is the study of the origin and evolution of life in the universe). Chizhevsky's main contribution to Russian cosmism was his theory of the influence of cosmic solar radiation on the behaviour of organized human masses as well as on universal historical processes. In 1918 Chizhevsky presented his doctoral thesis on universal history in Moscow where he defended the idea that the sun's activity has an effect on many phenomena in the biosphere, including changes in crops, diseases, and human psychology. In his ‘sunspot cycle’ theory, the change in solar activity was identified as the main trigger of historical events, including political and economic crises, wars, and revolutions. Chizhevsky later published his theory in the book Physical Factors of the Historical Processes (1924), which brought him fame. But as his ideas contradicted Soviet theories of the reasons for the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, Chizhevskiy was denounced in 1942 and sent to gulag. After spending 16 years in prison camps and exile, he was released and never again wrote on solar cycle theory, but he made his name with other theories, the most important being that of aero-ionization and hemodynamics.Footnote 20

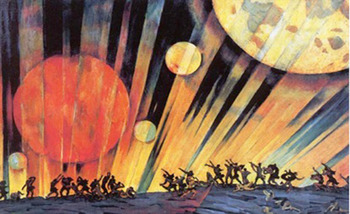

Cosmic concepts such as the ‘noosphere’, ‘cosmic philosophy’, ‘evolution of cosmic life’, and ‘solar-earth unity’ opened up a space for several important ideas to develop. These included cosmic energy (kosmicheskaya energiya that transfers various miraculous properties, defines human lives, and connects them with the universe), cosmic ethics (kosmicheskaya etika that describes our role and moral duty in controlling and perfecting the universe and not destroying or harming it), and the unity of humanity with both the earth and the limitless expanses of outer space inhabited by innumerable alien civilizations. By upgrading our bodies and achieving a godly status of immortality in the technological age of the noosphere, humankind—homo immortalis—is destined to unite politically, establish paradise on earth, and give a new meaning to the universe. In the early decades of the Soviet Union, when the Bolsheviks were still experimenting with all sorts of ideas, it is not difficult to imagine that cosmism's activist approach to all life's problems and its way of thinking—full of idealism, zeal, and energy—offered a source of inspiration to early Soviet literature, poetry,Footnote 21 philosophy, art, and even science (see Figure 2). But as scientific disciplines quickly consolidated under the umbrella of Marxism-Leninism, the occult and pseudo-scientific side of cosmism was suppressed by the state. Nevertheless, the fathers of the movement were heroes of Soviet propaganda for other reasons and some of their idealistic ideas about the possibility of conquering the cosmos and the power of collective intelligence to change the world were incorporated into Soviet mainstream thinking, albeit under different names. Forced into an underground existence, Russian cosmism as a whole not only mixed with and developed many themes analogous to other alternative movements, it also influenced them, including Eurasianism (Evrazystvo), a pseudo-science offering a continental, if not global, perspective on the fate of Russia-Eurasia/the Soviet Union.

Figure 2. ‘New Planet’ by Konstantin Yuon (1921) shows the 1917 Revolution as the result of a cosmic catastrophe. This painting is on display at the New Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Eurasianism as a theory of cosmic energies

Any discussion of Russian cosmism would be incomplete without an account of the idea of Eurasia popularized by the dissident Soviet historian Lev Gumilev (1912–1992). Gumilev's account has its roots in a theory of Eurasia first proposed by Russian émigrés in Sofia, Bulgaria, in the 1920s. The first proponents of this theory, who fled Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution and rejected Europe's individualistic and materialistic spirit,Footnote 22 argued that Russian civilization did not belong to any ‘European’ category but is a unique civilization in its own right. It is neither European nor Asian but something in-between—Eurasian. The Eurasianism of the émigrés—also referred to in the literature as ‘classical Eurasianism’—was a system of ideas based on the argument that Russia-Eurasia is a unique civilization shaped by its ‘homogeneous’ geographical location.Footnote 23 Owing to this geographical unity, Eurasia, which encompassed myriad peoples with different languages, cultures, and histories, was historically predestined by nature itself to form a single civilization, a single state unit. By using the notion of geographical causation to theorize the behaviour of various populations inhabiting a vast territory, the Eurasianists set out to explain not only the evolution and character of Russia-Eurasia but also to predict its future in order to determine imperatives for Russia's development. In their view, geography, human psychology, and history were inseparable categories. Being opposed to militant atheism and Bolshevik ideas, the majority of them nevertheless saw the 1917 Revolution as a necessary reaction to the rapid modernization of Russian society and firmly believed that, in time, the Bolshevik government would evolve into a new national, Orthodox-Christian government. Being an emotional rather than an intellectual movement that wished to see Russia-Eurasia as a religiously regenerated, non-European, and non-Bolshevik country, Eurasianism had lost its appeal by the time the Bolsheviks emerged from the Russian Civil War as the absolute victors. Impatient to meet the future, little did the early Eurasianists know that it would take another 70 or so years for their dream to be fulfilled.

This movement's ideas about geographical determinism, however, were later picked up and developed in the Soviet Union by Gumilev in his theory of Eurasia. Gumilev, who also saw the Soviet Union as neither European nor Asian but a unique Eurasian civilization, argued, in the spirit of classical Eurasianism, that the defining element of human groupings in Eurasia is not so much genetics as their link with landscape or geography. Nevertheless what sets Gumilev apart from the classical Eurasianists is his concept of ‘passionarity’ (passionarnost) which explains the genesis and evolution of ethnoses in the context of geographical determinism. In his view, the history of Eurasia and its diverse peoples are part of an uninterrupted process in which energy, called ‘passionarity’, gives birth to new ethnoses and civilizations; ultimately, when the energy is depleted, the ethnos/civilization dies out, giving way to the next. In his book, Gumilev explains ‘passionarity’ as follows:

Usually, people, like other living organisms, have as much energy as is needed for sustaining life. If a person is able to ‘absorb’ energy from the environment more than is ever needed, then that person forms bonds with other people, which allows [him/her] to use this energy in any direction [he/she] chooses […] Using this excessive energy in organizing and managing their compatriots at all levels of social hierarchy, they [i.e. passionarians, or people who have ‘super-abundant’ energy], though with hardship, set up new stereotypes of behaviour, forcing others to adopt it, and in this way bring into existence a new ethnic system, a new ethnos.Footnote 24

In its turn, ‘passionarity’, according to Gumilev, originates from cosmic rays which are absorbed by a landscape. In other words, it is cosmic energy from outer space that ultimately shapes terrestrial human civilizations:

During its geological existence, our planet has been enriched with energies, absorbing: (1) solar energy; (2) atomic energy of radioactive decomposition inside Earth; (3) cosmic energy […] from our Galaxy […] Therefore, our planet gets from the cosmos more energy that is needed to sustain an equilibrium in the biosphere, which leads to excesses that bring about […] passionarian pushes, or ethnogenesis [i.e. birth of new ethnoses].Footnote 25

Passionarity is not equally distributed across the globe. According to Gumilev, Western Europe and the Atlantic powers (including the United States) not only have low levels of passionarity, but are also constantly losing this vital energy, while Russia-Eurasia and the Middle East are blessed with rising passionarity. Gumilev shares his predecessors’ anti-Western prejudices, but, unlike them, he is close enough to the Russian cosmism movement for his theory of ethnogenesis and passionarity to be described by some scholars as a ‘biocosmic theory’.Footnote 26 What Gumilev did was to ‘energize’ human history and trace the energy stored in the landscape (which unites various peoples and brings about civilizations) back to its cosmic origin. Influenced by cosmism, in his works Gumilev draws upon the theories of some important cosmists, including Vernadsky's ideas of the biosphere and noosphere, and Chizhevsky's thoughts about the influence of solar energy on human history.Footnote 27

Although Gumilev's ideas about geographical determinism and a landscape which absorbs excessive and transformative cosmic energy were rejected as ‘unscientific’ and most of his monographs were banned from official publication, he attracted much publicity in the perestroika years, as did various scholars of Russian cosmism. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, his ideas, as Humphrey notes,Footnote 28 became very popular in many parts of Russia, especially among ethnic minorities, not least because Eurasianism offered them a new post-Soviet identity and non-Marxist ways of reimagining their past, present, and future.

In Kalmykia, Gumilev's books, along with those of the rediscovered Kalmyk Eurasianist Erenzhen Khara-Davan,Footnote 29 have achieved huge popularity among people from all walks of life. ‘Eurasia’, ‘Eurasian civilization’, and ‘passionarity’ became widely used terms in official speeches and everyday parlance alike. Seeing themselves as neither Soviet nor European, nor even Asian, many Kalmyks not only embraced their new identity as a unique Eurasian people but were also inspired by the expectation of a ‘passionarian push’ (passionarnyi tolchok) that would initiate the development of the Kalmyk nation within Russia. In the strict Gumilevian interpretation, for a passionarian development to occur, what was needed first of all was a leader with ‘super-abundant cosmic energy’ or passionarity. That, at least, was the way in which many Kalmyk cosmists and philosophers interpreted the situation. This leader was found in the person of Kirsan Ilyumzhinov who was elected the first president of post-Soviet Kalmykia in 1993 on a wave of popular Eurasianist-cosmist euphoria.

UFO sightings and the revival of Russian cosmism

In his influential book Flying Saucers, Carl Gustav Jung argues that the UFO phenomenon is a myth-in-the-making and a projection of modern technological and salvationist fantasies.Footnote 30 The UFO phenomenon, according to Jung, is connected with universal anxieties generated by the mechanized conflicts of the Second World War and the Cold War. It has become a psychological substitute for God in secular Western societies in which religious belief has diminished or become lost. People in these technological societies have become sceptical about supernatural beings, as depicted in traditional myths and holy books, and have been inclined to interpret the signs in the sky as machines from a world with technology more advanced than ours. Jung also notes that the first ‘flying saucer’ stories appeared in 1947 in the United States, two years after the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the atomic era. Perhaps not coincidentally, the most important of the early UFO stories emerged near Roswell, New Mexico, not far from Alamogordo where the first atomic bomb was tested. Such stories intensified in the United States as tension with the Soviet Union grew and the fear of war grew ever greater. In the first UFO stories from the early Cold War period, the extra-terrestrials were usually benevolent and there was the hope that they might bring peace to our world.

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union—a country which had developed the largest and best-funded scientific establishment in history and was taking huge strides in developing rocket technologies—stories about unidentified flying objects or apparatuses rarely appeared in the state-controlled mass media. The founding fathers of Russian cosmism focused more on ideas about humans visiting other planets or advanced alien civilizations controlling evolution in the universe. Nevertheless, during the Soviet period, occasional stories in the media about ‘flying saucers’ and ‘flying pans’ were treated either as bourgeois propagandaFootnote 31 or explained away as atmospheric phenomena or folklore-based mass fantasies.Footnote 32 That said, with differing degrees of scrutiny, the Soviet authorities always kept an eye on such reports. During the Khrushchev Thaw, marked by the general relaxation of censorship, which coincided with the beginning of the Soviet space exploration programme, scientists felt relatively free to discuss various topics. For example, in 1955 Felix Zigel, a professor at the Moscow Aviation Institute, was permitted to set up a group consisting of top Soviet scientists and cosmonauts who were interested in UFOs. However, censorship was reintroduced at the beginning of the Brezhnev era (1964–1982) and in the ensuing years UFO sightings were mentioned in the media only to debunk the possible extra-terrestrial origins of the flying objects.Footnote 33

But this does not mean that the authorities did not study the phenomenon behind closed doors, with various theories in mind. The first Soviet state-sponsored programme to study ‘paranormal phenomena’ in the skies was approved in 1977 at the level of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and was included in five-year research plans. Special teams were set up at the Soviet Ministry of Defence and the Soviet Academy of Sciences with three major lines of investigation: the possibility of UFOs being a product (1) of human activity and technologies (rocket launches, enemy aircraft, etcetera), (2) of atmospheric processes, and (3) of extra-terrestrial origin. Although this research was highly classified, public interest in UFOs and in cosmic topics in general did not diminish, not least because of how information was collected in the Soviet Union. In the case of Soviet military intelligence-gathering, any personnel who witnessed an inexplicable phenomenon in the skies was obliged by a directive from the Ministry of Defence to write a report to the head of their unit. In some urgent cases such reports bypassed normal bureaucratic procedures to end up on the table of the chief of general staff himself. Stationed in all parts of the Soviet Union and with obligatory conscription, Soviet armed forces not only provided a large-scale observational capability but also proved to be a significant source of various cosmic rumours when soldiers left the army and returned to civilian life. The Academy of Sciences also cast a wide net, gathering information from meteorological stations dotted across the country, research institutes, eyewitness accounts, and various publications. During the 13 years of the programme, which was closed down in 1990, the Academy of Sciences, for example, had independently collected 3,000 related reports, of which 400 were labelled ‘extraordinary’ and ‘paranormal’.Footnote 34

While the UFO phenomenon was secretly studied by Soviet scientists in two state organizations and discussed in closed circles of cosmists, psychics, and other interested parties, the first serious works chronicling extra-terrestrial visits only appeared on the shelves of bookshops from the beginning of perestroika and glasnost, a development accompanied by mass sightings of UFOs in many parts of the Soviet Union. As in the United States, UFOs also seemed most likely to be sighted near military bases, atomic electricity plants, and other strategic locations. Spectacular landings of UFOs in Voronezh near a major Soviet military installation in 1989, a UFO sighting over Leningrad's Sosnovy Bor nuclear power station in 1991, a similar sighting over the Chernobyl atomic plant in 1991, and a report of UFOs flying over Chelyabinsk, a Soviet military bomber training base, are probably the most celebrated incidents disseminated through central news agencies and newspapers across the Soviet Union. The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) reported on the Voronezh incident in its 9 October 1989 issue in sensational terms:

Aliens visited the place [a park in Voronezh] after dark, at least three times, locals report. A large shining ball or disc was seen hovering above the park. It then landed, a hatch opened, and one, two, or three creatures similar to humans and a small robot came out. The aliens were three or even four metres high, but with very small heads.

Many local newspapers also reported sightings in small and not very strategically important localities in increasing numbers. Simultaneously, the number of open UFOlogy groups mushroomed across the Soviet Union. A survey conducted in the early 1990s revealed that 70 per cent of respondents believed in UFOs.Footnote 35 It would not be too far-fetched to assert that the first reported UFO sightings and abductions in Kalmykia were bound to occur sooner rather than later.

The beginning of perestroika was also a turning point for these hitherto suppressed ideas and movements, including Russian cosmism which was revived and then openly proliferated. Although cosmist ideas had invariably circulated among various underground circles involved in all sorts of ‘alternative’ practices, including astrology, extrasensory perception, paranormal phenomena, sorcery, and even alternative historiography (recall that the dissident historian Lev Gumilev was influenced by cosmist ideas), during perestroika cosmist ideas reached and resonated with a wider audience. Given the popularity of cosmos-related topics and projects in the Soviet Union—not to mention the widespread anxiety caused by Ronald Reagan's ‘Star Wars’ initiativeFootnote 36—the ideas of Russian cosmism fell on fertile soil and quickly captured the public imagination. During this period, when the state's hold on religion was relaxed and a revived spirituality swept across the country—and when science as such was still broadly respected—cosmism came to be promulgated as dukhovnaya nauka (‘science of the truth, soul-searching’), and purported to address hitherto suppressed psychic, spiritual, and paranormal issues and anxieties from a global, cosmic perspective. The fact that the movement was also propagated as a unique product of the Russian mind—hence the label ‘Russian cosmism’—only helped sustain its popularity against the backdrop of growing nationalism that swept across the country. Beginning in 1988, conferences and seminars on Russian cosmism became regular and a substantial literature has since emerged.

Cosmism in post-Soviet Kalmykia

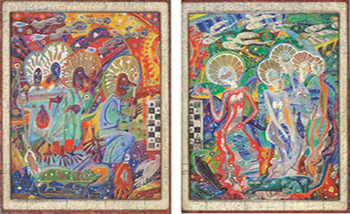

Perestroika and the subsequent demise of the Soviet Union opened the door to a variety of ‘alternative’ movements, ideas, and practices, including theosophy, agni-yoga, psychics, energy vampirism, demonology, sorcery, astrology,Footnote 37 neo-paganism, cosmism, Eurasianism, not to mention traditional religions. One of the first cosmism-related groups to emerge in Kalmykia was the so-called Eurasian Academy of Life established in Elista in 1990 by enthusiasts comprising Eurasianists, cosmists, historians, psychics, and fortune-tellers. A discussion club called Aribut was founded by Valery Dorzhinov following his famous encounter with aliens in 1992. He later also organized a series of exhibitions of his cosmic paintings, thereby contributing to the proliferation of cosmism in Kalmykia. Other notable names worth mentioning in this regard are the famous Kalmyk artist Dmitry Sandjiev, a self-proclaimed alien abductee who paints cosmic art (see Figure 3); the architect Jangar Pyurveev, who has edited several books on cosmism;Footnote 38 and Zoya Boschaeva, professor of economics at Kalmyk State University, who writes on solar-earth theory. Like many cosmists, these individuals claim to be connected to the noosphere from where they say they receive novel ideas, visions, and the truth about the cosmos. Dmitry Sandjiev explained to me:

There is cosmic energy and there is the noosphere about which Vernadsky talked, right? I think that all ideas that I receive [from the cosmos] come from the noosphere. It is where all human thoughts have been deposited for many centuries. I have a small antenna in my head and that is how I receive the information. [As a result] I have no problems whatsoever with coming up with new ideas regarding my artwork. All [novel] ideas come to me momentarily.Footnote 39

Figure 3. ‘Chess duel’ (2006) by the Kalmyk artist Dmitry Sandjiev depicts aliens playing chess. Source: Reproduced with kind permission of the artist.

The former anaesthetist Alexei Nuskhaev, who was a state ideologist in Kalmykia until around 2000, deserves special mention. Having worked at the reanimation unit in a hospital in Elista, in 1991 Nuskhaev was made redundant. This enabled him to pursue his interests. Being a curious, spiritually tormented, and poetically inclined man, he came to be interested in many previously suppressed movements, including cosmism, Eurasianism, and especially Russian neo-pagan ideas.Footnote 40 Influenced by Russian neo-paganism in its most mystical and occult form, he talked and wrote extensively on the ‘deep’ prehistoric past, on the ‘Vedic’ wisdom of the ‘Great Kalmyk Ancestors’, on flying Vedic pyramids and extra-terrestrials, and on the ways in which Russia-Eurasia could be preserved. When the Eurasian Academy of Life was established in Elista, Nuskhaev joined its team in the capacity of ‘Great Teacher’ to conduct research into the history of two Eurasian peoples—the Russians and the Kalmyks. In the best tradition of Russian neo-paganism, in which personal spiritual experience is considered an important technique for studying the world, Nuskhaev ‘spiritually’ researched dark, unknown pre-history by using his imagination and by discovering ‘glorious facts’ in Russian and Kalmyk folklore. He also claimed to be connected with cosmic aliens.

Impressed by his Eurasian-Russian patriotism, occult knowledge, and cosmic ideas, in 1995 President Ilyumzhinov invited Nuskhaev to become his personal adviser and for this purpose created the post of state secretary for ideology (Gossekretar po Ideologii). The former anaesthetist accepted the offer and set about resuscitating the spiritual energy of the Kalmyk nation instead of the unconscious bodies of mortals. Given Russian cosmism is an action-oriented world view, Ilyumzhinov tasked his state ideologist with helping him to formulate a new state ideology that would transform the Kalmyks from a peripheral people into the banner holders of Russia and humanity as a whole. In his pamphlet Nuskhaev writes:

In recent times President [Ilyumzhinov] has often talked about the planetarian way of thinking (planetarnoe myshlenie) […] Further economic development, its perspectives, viability as well as a modern way of thinking cannot progress in a state of territorial borders. The final phase of this process will be the liquidation of all borders all over the world […] A thought is a stream of energy. The energy of thought does not accept limited space and [therefore] naturally our thoughts are what the planetary energetic space—i.e. the [noo]sphere of Vernadsky—consist of. The thoughts of the Kalmyks, who live in Kalmykia but who think in the united energetic space, automatically enter the planetary energetic space through ‘energy [carrying] arteries’ and become its structural component. In other words, planetarian thinking will inevitably lead any leader to achievements in economy, information, politics and culture at a global level.Footnote 41

During his career as state ideologist, Nuskhaev produced a long list of works, about 24 short books in total. This pleased Ilyumzhinov, who often boasts of his own ability to utilize ‘planetarian thinking’.

Ilyumzhinov was in charge of Kalmykia from 1993 to 2010. During his tenure, he never stopped amazing citizens not only with his ‘excessive cosmic energy’—which he claims to absorb from the surrounding landscape in Kalmykia in the best tradition of Gumilevian neo-Eurasianism—but also with his projects, each more bizarre than the last. Some examples include: a project to build a space launch facility in Kalmykia; the reburial of the stuffed carcasses of the first Soviet canine cosmonauts Belka and Strelka in the Central Buddhist Monastery in Elista; and the building of a mausoleum in Elista in order to repatriate Lenin's mummy on the grounds that his grandmother was a Kalmyk. In Ilyumzhinov's words, his interest in the supernatural and ‘alternative ideas’ first developed in the late 1980s when he was studying at university in Moscow. But unlike other like-minded individuals in his position, Ilyumzhinov did not set up a spiritual community but went further. After his success in the Kalmyk presidential election in 1993, he officially reunited religion and state, thus constitutionally enabling himself to conduct realpolitik with the help of astrology and cosmic energy. To the Steppe Code (new Kalmyk Constitution) Ilyumzhinov added a Vernadskian-type clause that ‘all citizens of Kalmykia are responsible for what is happening on Earth’. According to Ilyumzhinov, all Kalmyks, including ‘children are responsible for hunger in Africa, a tsunami in Indonesia, the ozone hole over the Antarctica’, because ‘we are all Earthlings, children of the cosmos’. Imposing new global responsibility on ordinary Kalmyks was not his only strategy. ‘You know, no matter what I say to [local] people, I hypnotize them at the unconscious level. I do the same with Russians from other regions. Around the republic I create a positive extra-sensorial field, and it helps me in all I do,’ Ilyumzhinov boasted to an Izvestiya correspondent in 1995.Footnote 42 Below is an extract from another interview he gave in 1995:

Correspondent: Do you have astrologists?

Ilyumzhinov: Both in Moscow and here [in Kalmykia] I have dozens of them. All come to me: communists, anarchists, and those who are connected with the cosmos. I always receive them. Baba VangaFootnote 43 is an honorary citizen of Kalmykia. She foretold how many factories we would build. She also showed where would be a petrol-processing plant: she is blind, but like this she was drawing with a pen on the map and put a dot. Later on, scientists discovered that she got it right. Baba Vanga's niece is a professor-parapsychologist, she opened the biggest windmill here.

Correspondent: Who is that strange man who has just left your office?

Ilyumzhinov: He is Aizen, a French offspring from Chechnya, and he is a new messiah. In a month or two he will announce about himself to the world. Over there is Ivan Yakovlevich from Rostov oblast. Would you like to see him?

(Correspondent's observation): Ivan Yakovlevich, a man with a mysterious, drunken look, is laying out on the table some shabby papers on which are drawn circles and arrows. He confides that this system was given to him from above. ‘He is enlightened, a Teacher descends upon him from the skies,’ explains the president. Mid October, according to the clairvoyant, is an auspicious time for elections.Footnote 44

On the advice of Ivan Yakovlevich, Ilyumzhinov—to universal puzzlement—announced a new presidential election to be held on 15 October 1995, although his first term had two more years to run. Making sure that he was the only candidate to run for the post, Ilyumzhinov effectively re-elected himself for another seven years,Footnote 45 thus securing his presidency until 2002. In fact, in that same year Ilyumzhinov was busy arranging another election, this time to FIDE (the World Chess Federation). According to Ilyumzhinov, Baba Vanga also foretold that he would become the president of FIDE:

Everything that she [Baba Vanga] had foretold was realized. For example, half a year prior to my being elected President of FIDE, in April 1995 she said, ‘I see two Kirsan [Ilyumzhinovs]’, and laughed. [Then] she said, ‘So tiny, thin, but you are sitting on two arm-chairs, two presidents, [you] became double’ […] In November I became President of FIDE, and now, as an exception, occupy two posts at the same time.Footnote 46

Following his claim that he was abducted by extra-terrestrials, in 1997 Ilyumzhinov made a sensational announcement in TIME magazine that earth was set to collide with the planet Nibiru, killing everyone, unless people cleansed their aura by playing chess, which he claims to be a game of extra-terrestrial origin. Not coincidentally, Ilyumzhinov made chess a compulsory lesson in secondary schools in Kalmykia. For him, a planetary perspective is useful not only for understanding global problems and threats but also for the micromanagement of his small republic. When Ilyumzhinov was asked by a journalist about how he planned economic policy, he replied:

I meditate. By meditation I gradually rise up to the astral level of the cosmos. As I rise up everything gets smaller, the people, the houses, become tiny, I see the land and then the continent, and from up there I look down on the planet Earth. Everything then becomes clear and understandable.Footnote 47

Having ruled Kalmykia for 17 years, in 2010 Kirsan Ilyumzhinov had to resign from his post. This was not because of his occult ideas or his cosmic mismanagement of the republic, which, according to Russian surveys, is one of the poorest places in the country, but because of a new law passed by then-president Dmitry Medvedev prohibiting regional leaders from staying in power for too long. Kirsan Ilyumzhinov is a well-known figure in Russia due to his media appearances during which he often talks about his cosmic experiences.

Today Russian cosmism is a diverse, eclectic, and growing movement with increasingly blurred boundaries, producing strange offshoots in various places across Russia. Posing as a movement to unite science with dukhovnost’ (the intangible, soul-searching), it parallels Marxism-Leninism in terms of its all-encompassing vision, ambition, and readiness to act. Fields in which cosmism is said to be applicable range from the economy to arts, from sciences to politics and ecology, albeit with no guaranteed success, as seen in the case of Kalmykia. Having a firm footing in the realm of the intangible, Russian cosmism, which positions itself as a non-religion, can even influence religions.

In Kalmykia many folk healers, who practise folk Buddhism, extensively use various energies in their healing practices, including cosmic energy (kosmicheskaya energiya) which they claim to absorb from their environment or receive from Buddhist gods. Some even say that they receive this energy directly from the cosmos and are connected with intelligent extra-terrestrial beings. The most prominent belong to a community called Vozrozhdenie (Revival), led by a charismatic folk healer, Galina Muzaeva, who appropriately describes her belief as ‘cosmic Buddhism’ (kosmichesky Buddhizm). Apart from healing sick people by means of traditional methods (such as reading Buddhist mantras, using herbs, and so on), the community, which consists of 16 ‘cosmic Buddhists’, carries out cosmic projects in collaboration with extra-terrestrial powers. Members of the community communicate with the cosmos and receive celestial maps, diagrams, and instructions on how to create ‘energy corridors’ (energeticheskie koridory) for UFOs to beam down cosmic rays. Once these spots have absorbed sufficient cosmic energy, Galina Muzaeva assured me, they would begin to radiate with enough power to turn the entire planet into an earthly paradise where diseases would be eradicated and all religions and nations united in a ‘cosmic union’ under the leadership of the ‘spiritually powerful’ Kalmyks. In the early 2000s, Galina performed a series of ‘cosmic rituals’ for President Ilyumzhinov in order to connect his body to ‘intelligent’ energies, or the noosphere, floating in outer space. Galina told me that the rituals were successful, which hardly seems surprising, given Ilyumzhinov's subsequent cosmic claims and projects.

Conclusion

It is a scientific fact that our planet is closely connected with the cosmos. Few would deny the benevolent effects of solar warmth on life, or the influence of the moon on the earth's tides, or the harmfulness of cosmic radiation on living organisms. The list can be easily expanded. While such earth-cosmic connections may not be very obvious, most of us are sure about these pronouncements because that is what modern science teaches us. In Kalmykia, as in other parts of Russia, many people take this one step further and believe that the universe, with its uncountable galaxies and life forms, is more interlinked than mainstream science acknowledges or is capable of verifying. According to this view, the universe consists of energy flows and humans are intimately connected not only with their planet but with the endless expanse of the universe through myriad cosmic energies and waves that transfer not just heat but many other miraculous qualities such as collective intelligence, memories, wisdom, healing powers, and even sensibilities. Some even believe the universe to be a gigantic living organism. Although the majority of such energies are yet to be discovered by science, according to the cosmist view we need to use all available methods and sources at our disposal, including those that are controversial—and even personal experience—in this endeavour.

In Kalmykia, as elsewhere in Russia, believing in ‘alternative’ ideas does not necessarily contradict what one learns from mainstream science. Furthermore, many in Kalmykia even say that these two paradigms complement each other. This favourable attitude towards ‘alternative’ knowledge stems partly from a particular Soviet experience of science after Marxism-Leninism failed in its promise to construct a ‘super-science’ that would explain everything. The repudiation of Marxism-Leninism as a dominant explanatory paradigm resulted not only in the blurring of the line between science and its alternatives, but it also shattered a firm belief in the omniscience of the mainstream science with which Marxism-Leninism tried so hard to associate itself. As a result of this paradigm shift (which led to the creative reinterpretation of science itself, not to mention the opening up of the hitherto banned areas to ‘scientific’ investigation), a variety of alternative belief systems emerged to assert their ‘scientific’ credentials. In popular understanding, science is that which correctly describes reality. A strategy to enhance legitimacy by appealing to the authority of science is peculiar not only to religious movements,Footnote 48 but also to a wider range of alternative knowledge systems that purport to describe reality in all its manifestations, both visible and invisible, known and unknown. One of them is Russian cosmism, a movement that positions itself as dukhovnaya nauka, or ‘a science of the truth, of soul-searching’, which emphasizes that throughout the cosmos much more is unknown than known, and more is invisible than visible. This accounts for the movement's openness to all sorts of research methods, both pseudo-scientific and modern.

Apart from its self-proclaimed ‘scientific’ credentials, Russian cosmism, which is in a perpetual state of inventing itself, owes its growing popularity to its promotion as an original product of the Russian mind as opposed to ‘Western-Atlanticist’ one. Staunchly nationalist, many Russian cosmists are also openly anti-Western. In fact, such sentiments are widely shared by many movements that are gaining popularity in today's Russia. Another major factor that makes cosmism attractive is its association with the names of its founding fathers, who have acquired celebrity status. Fully rehabilitated, Fedorov, Tsiolkovsky, Vernadsky, Chizhevsky, and others are more popular in Russia today than ever before. Many of their works and ideas that were suppressed during the Soviet period—especially those related to the occult and pseudo-science—have become popular knowledge and their names have been given to institutes, funds, organizations, and museums. For example, the Fund of V. I. Vernadsky, established in 1995, is one of the biggest charity organizations in Russia to support ecologically oriented educational projects. The Fund organizes competitions, study groups, and seminars, often in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and the Russian Academy of Sciences. The Russian Academy of Cosmonautics, named after Tsiolkovsky, was also founded in 1991. In Kaluga the annual Tsiolkovsky Lectures have become a platform to discuss his ideas as well as theories connected with pseudo-science and the occult. In 2008 Tsiolkovsky was posthumously awarded the Symbol of Science medal for ‘the creation of the basis for all projects related to the exploration of new cosmic spaces’. Chizhevsky and Fedorov have also been honoured in Russia: a science centre bearing Chizhevsky's name and a museum-library named after Fedorov were opened in Kaluga and Moscow respectively. Conferences, lectures, and exhibits are also regularly organized to popularize their ideas, which are often reported in major Russian newspapers and broadcast on television.

The founding fathers of Russian cosmism should, first of all, be understood in the context of their time, an era characterized by the growing cult of science and humanism. What they did was to attempt to systematize new ground-breaking discoveries (concerning the tiniest particles, such as atoms, to the largest, such as galaxies, and everything in between) and offer a new unifying account. In place of diminishing religious authority and values, cosmists also offered a new source of meaning and authority: human experiences and feelings. According to them, the universe was to derive its meaning not from the dying gods but from humanity itself. Given the circumstances of the time, their knowledge and explanations were bound to be as speculative as they were emotional. It is no wonder then that Russian cosmism emerged as a cultural-intellectual movement that promulgated speculative ideas about the nature of humanity, its projected evolution, and its place in the universe—and this trend continues to this day. Although attaining immortality is seen as a task for all humanity, this endeavour has to be managed by strong leaders. In Federov's vision this leading role is assigned to ‘a Russian autocrat’; in Tsiolkovsky's and Vernadsky's views, to ‘a team of leading scientists’. According to other cosmists, it has to be ‘the godman’ himself that must direct the masses—a view that seems to be in tune with the political preferences of many Russians. Due to its open-ended, eclectic, and all-embracing nature which seeks to connect anything with everything else, cosmism attracts all sorts of intellectuals, including nationalists, scientific immortalists, conspiracy theorists, religious critics, spiritualists, environmentalists, not to mention eccentric people who are simply open to ‘alternative’ ideas. That said, some of the ideas associated with cosmism have proved to be truly inspirational and ahead of their time. The science of ecology was first conceived in Russia by Vernadsky who also developed the concept of the ‘noosphere’ to denote an idea that we live in a new epoch marked by human activities on the planet, long before Eugene F. Stoermer proposed his ‘anthropocene’ in the 1980s, denoting essentially the same idea. Vernadsky's notion itself found its way into intellectual circles in the West via the French philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin who has had a profound influence on New Age movements. Fedorov is regarded as a precursor of transhumanism, which today is also an international intellectual movement that aims to enhance human physiology with the help of modern technologies, with the ultimate aim of attaining immortality. Inspired by developments in genetic engineering, nanotechnology, regenerative medicine, and similar fields, ambitious life-extending projects are gaining pace, with Google alone investing millions of dollars in this vision. Not only did Tsiolkovsky put the foundations in place for the Soviet space exploration programme, he also influenced Wernher von Braun who is acknowledged as the father of space science and rocketry in the United States, a country whose rivalry with the Soviet Union pushed space exploration forward.

Russian cosmism first emerged as a movement purporting to explain, transform, and bring universal order to a world in which the power of the gods was diminishing. Owing to the socially transformative period in which an idealistic belief in science, humanity, and utopian expectations of social justice prevailed, in the early twentieth century the movement focused more upon its ideas of (r)evolutionary transformation and human domination of the cosmos. Having survived an esoteric and pseudo-scientific underground existence during the Soviet period, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian cosmism became more fixed in its ideas about maintaining cosmic order, harmony, and averting catastrophes and regression. As the country is still undergoing deep transformations, this trend continues in Russia to this day. The Kalmyk cosmist Jangar Pyurveev reflects this spirit, maintaining that:

Humanity is changing the face of the planet because the actions of people, which are full of anthropocentrism, are already affecting the Solar system, pushing it to catastrophe […] Perhaps we still underestimate our link with the universal intellect (razum), with the universal cosmic space, which tries to help us out, to make us change the pace of evolution on Earth which we have distorted ourselves.Footnote 49

His solution to this existential problem is:

Humankind, burdened by its past, has to set itself free from the past and take on a new [body]—not a local geopolitical, but a planetarian-noospheric body […] to integrate [itself] into a single planetarian system […] In order to get out of the deadlock, what is urgently needed are constructive ideas on a planetary scale as well as leader-countries capable of uniting the whole of humankind for the collective and purposeful realization of these ideas.Footnote 50

In Kalmykia solutions to this challenge have been offered not only by philosophers (such as Pyurveev) and politicians (President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov and his secretary for ideology Alexei Nuskhaev), but by religious specialists as well. Vozrozhdenie, whose members identify themselves as followers of ‘cosmic Buddhism’, perform special rituals to heal the earth and unite its inhabitants by means of cosmic energy that they claim to receive directly from UFOs and deposit in Kalmykia's landscape. Given the high number of UFO sightings and healing rituals involving cosmic energies, it can be said that in post-Soviet Kalmykia, where the former president happens to be a famous cosmist himself, certain aspects of Russian cosmism have become part of popular culture.

By positioning itself as a universal ‘science’, Russian cosmism also has parallels with other ambitious, all-embracing movements that are rising from the ashes of Soviet science and totalitarian ideology. One of them is Eurasianism, which offers a systematized explanation of the fate of a large territory which coincides with the border of the former Soviet Union and which is inhabited by myriad sedentary and nomadic peoples with different languages, histories, and cultures. Whereas in the Soviet period this political-geographical union was legitimized by the Marxist-Leninist theory of social evolution by stages, today its most promising substitute is Eurasianism, which postulates the idea of fixed primordial civilizational clusters that exist in opposition to one another, rather than social evolution. By emphasizing the uniqueness of Russia-Eurasia, Eurasianism is also an anti-Western world view. Despite being based on an esoteric Gumilevian idea of passionarity (passionarnost)—that cosmic energies absorbed by the landscape bring about strong leaders who then unite various peoples and shape civilizations—Eurasianism, in its ideological and most pragmatic sense, has attracted the attention of the intelligentsia and nationalists as well as that of powerful politicians. The most prominent among them is President Putin who supports the idea of Eurasian civilization and is himself a banner holder of the Eurasian integration project. On 1 September 2017, he gave an open day speech for pupils in secondary school in the town of Yaroslavl which was broadcast by the main TV channels in Russia. In a bid to inspire and energize the younger generation, the president gave them the following task:

Your task is not only to make something new but to take a principally new step. Look at how the world develops today. There are countries that have incommensurably larger populations than ours. There are states that have technologies and modern ways of management that far surpass those of ours. But a question arises: If we [Eurasian people] have existed for more than a thousand years and have been actively developing and strengthening ourselves, does it not mean that we have something that is conducive to this? This ‘something’ is the ‘nuclear reactor’ inside our people—[ethnic] Russians [and] people who are Russian [citizens]—that allows us to move forward. This is passionarity that Gumilev wrote about, which pushes our people forward. And all of you, who are starting an active life, need to take this into account and achieve qualitatively better results.

In the Soviet Union, the cult of science laid the foundation of Soviet rule. In post-Soviet Russia, many ideas inherited from the previous period still have a powerful appeal, and science as such still enjoys enormous popularity. It remains to be seen whether Russian cosmism or Eurasianism—or any other system of ideas—will attain proper ‘scientific’ status (that is, will be taught as reflecting the infallible laws of nature and the universe) and where this will lead.