Introduction

During the eighteenth century, the East India Company and its merchants adopted Mughal symbols and customs to legitimate their administration while also accommodating ‘Indian forms of rule’.Footnote 1 With the consolidation of British imperialism in the nineteenth century, however, a discursive shift occurred. During this time, the British increasingly justified their political intervention by establishing themselves as a moral and judicial counterpoint to South Asian power structures and court culture. In this political strategy of differentiation, the British undertook the project of ‘civilizing’ indigenous courts such as the nawabs of Avadh, India.

This new imperial turn is evident in the historiographical and artistic reception of the last nawab of Avadh, Wajid ‘Ali Shah. Wajid ‘Ali Shah was continually earmarked as an alien ‘other’, and his artistic practices have been scrutinized in accordance with this view. He reigned for only a short time, from 1847 to 1856. He shepherded the nawabate to its closure in 1856 after refusing to sign a demeaning treaty with the British government, which responded by officially annexing Avadh, forcing Wajid ‘Ali to abdicate and driving him into exile. In part stemming from his decision not to engage in a physical confrontation with the British during his dethronement, Wajid ‘Ali is remembered as little more than an ‘oriental prince’ who prioritized his sexual pleasures over proper governance.

Visual substantiation of this narrative is provided by an infamous oil painting of Wajid ‘Ali, in which he appears grossly corpulent and baring his left nipple.Footnote 2 This image has been deployed as part of the colonial narrative that Wajid ‘Ali transgressed proper bodily regulation to express his deviant subjectivity and, by extension, establish a deviant government.Footnote 3 Besides the charge of notable decadence, the painting also speaks to Wajid ‘Ali Shah's sponsorship of the arts, as he patronized oil painting and the book arts during his reign. In particular, he was interested in theatrical performances, devising musical dramas and writing plays both in Lucknow, where his court was located when he was officially king, and in Calcutta, where he relocated during his exile.Footnote 4 Wajid ‘Ali wrote his own poetry under the takhallus (pen name) of Akhtar. Forty-three books are attributed to him.Footnote 5

Wajid ‘Ali Shah is therefore remembered in two ways: as an Oriental prince and as a devotee of the arts. These two facets come together in the ‘Ishqnama manuscript, completed in 1849, which was a versified semi-autobiography of Wajid ‘Ali's life.Footnote 6 Over the course of 131 dastans (episodes) and 103 accompanying miniatures, the ‘Ishqnama manuscript recounts how Wajid ‘Ali maintained his lovers, how he wisely disposed of them, and the lovesickness wrought by his affairs. The ‘Ishqnama also delineates important ceremonial rituals such as the enthronement of his father, Nawab Amjad ‘Ali Shah, and provides information on everyday household governance such as the role of eunuchs and his lovers in the court.Footnote 7

Historians have perpetuated the idea of the ‘Ishqnama as a perverse text by quoting it by way of a so-called translation into Urdu known as the Parikhana, which elides the ‘Ishqnama's original Urdu poetic structure and its 103 images by transforming the masnavi (narrative poetry) format into prose.Footnote 8 These authors purport to translate the ‘Ishqnama from Persian into Urdu. In actuality, the ‘Ishqnama is written in Urdu and contains Persian chapter titles with some Persian lexicon. Because the ‘Ishqnama is almost never viewed in its original manuscript format and is instead read through the Parikhana's simplified prose, Wajid ‘Ali Shah has been read as decadent, sexually excessive, and in a state of moral decay.Footnote 9 Such a reading is dependent on colonial norms for how sexuality ought to be expressed and ‘what constitutes sexuality’.Footnote 10 From a colonial vantage point, the expression of sexual desire is taken to be a private affair. Because the ‘Ishqnama was widely circulated, the manuscript can be taken as a sign of Wajid ‘Ali Shah ‘confessing’ his private matters to a public audience.Footnote 11 Such an analysis adds a layer of social stigma both to the ‘Ishqnama and to Wajid ‘Ali Shah. By focusing on these later translations and lithograph copies known as the Parikhana, we can trace the life of this manuscript and the various linguistic and visual transformations it underwent.

The manuscript is known as the ‘Ishqnama because of a Persian label attached to its front cover. The label reads ‘nazm ‘Ishqnāma hindī bā tasvīrāt’, which translates into ‘verses of the story of love in Hindi with images’.Footnote 12 The root of the title ‘Ishqnama is the word ‘ishq, which is defined ‘as comprising a number of feelings, both sacred and profane, and a complex of emotions centring on madness and violent obsession’.Footnote 13 The word has a Persian and Arabic etymology and is a frequent theme in mystical Sufi literature. As bookends, the first dastan in the ‘Ishqnama opens with Wajid ‘Ali's first love affair, which commences at the tender age of eight, and one of the ‘Ishqnama's final half-verses also harkens back to the title, stating: ‘This love, a story of women, has concluded.’Footnote 14 This arc is central to understanding the texts and images within. Contrary to present criticism that disparages the ‘Ishqnama and its author as obscene, as a whole, the manuscript projects Wajid ‘Ali's sovereignty. For instance, it discusses Wajid ‘Ali's sexual affair within a palace setting, positioning the community and the spatial arrangements of the household at the centre of the narrative. Titles of rank and ancestral ties are important details included throughout the manuscript. Wajid ‘Ali also reflects on his ability to control and punish his sexual partners. As a result, his lovers’ bodies and the space of his sexual encounters act as symbols of his power. This becomes evident once scholars engage with the original manuscript with its visual imagery rather than the reworked versions.

The genre of the masnavi taps into an erotology that has Indo-Persianate connections with courtly literature, mysticism, and politics.Footnote 15 Since the ‘Ishqnama is consistent with the masnavi framework both structurally and thematically, Wajid ‘Ali Shah is able to more forcefully focus on the concept of erotics and of ‘ishq, blending historical reality and fiction. Structurally masnavis typically begin with a bismillah (introductory formula), followed by hamd (praise to Allah), na't (eulogy of the Prophet Muhammad), and madh (laudation to a particular ruler or donor).Footnote 16 The ‘Ishqnama follows this standard masnavi opening by retaining the bismillah, hamd, and na't.Footnote 17 The madh is not present because Wajid ‘Ali Shah is both the supposed author of this text and also its patron. He does not praise himself, but praises the rights of ‘ishq and of God.Footnote 18 In one of the first hemistiches, Wajid ‘Ali engulfs his life and the entire world with ‘ishq: ‘[He is] love in the earth and love in the sky.’Footnote 19 Throughout this beginning verse, the earth, sky, past literary lovers, and other elemental objects are relationally connected through ‘ishq and through God's love. The line could also be translated as ‘Earth is love. Sky is love’, which is a standard trope in mystical Islam and its ‘all-embracing notion of love’.Footnote 20 Thus, the poetry in the ‘Ishqnama can be said to be deeply connected to Sufi principles of God's all-encompassing love. The initial invocation of the ‘Ishqnama also thematically sustains an engagement with the concept of erotics present within the masnavi genre by citing famous lovers from the masnavi canon such as Layla and Majnun, and Farhad and Shirin. By braiding these past literary characters into his present historical reality of amorous relationships, Wajid ‘Ali Shah creates a hybrid text that seeks to transcend the line between fiction and non-fiction. The reader of the ‘Ishqnama manuscript must contend with these multilayered meaning of erotics in which ‘ishq is a Sufic, political, fictional, and materially present concept. It is worth mentioning that the later ‘Ishqnama copies in lithograph and print form excised this opening poetry because it did not translate well into prose.

The ‘Ishqnama has formulaic principles similar to those of another genre category: the vaqa'i (text of historical events). A vaqa'i chronicles the life and events of a historical person. As such, the word has been translated into English as autobiography.Footnote 21 The core principle of an autobiography is that it is a life story narrated and written by the person who experienced it. Autobiography as a genre has the sheen of ‘authenticity’.Footnote 22 In that sense, autobiographies purport to be truth-telling and their veracity stems mainly from the author ‘speaking directly’ to their audience.Footnote 23 The form of the autobiography is also malleable, and it is not necessarily mutually exclusive to fiction. As Paul de Man has argued, the line between autobiography and fiction is ‘undecisive’.Footnote 24 Paul de Man further differentiates between these two modes by setting a limit on the extent to which the material traces of fiction can interact with the truthfulness of autobiography, stating that ‘autobiography seems to depend on actual and potentially verifiable events in a less ambivalent way than fiction does’.Footnote 25 The ‘Ishqnama seems to be autobiographical, as Wajid Ali Shah declares the text an act of self-representation through his use of the first-person singular. By adopting the ‘I’ form, Wajid ‘Ali Shah declares himself the subject of this manuscript, which gives the text a rhetorical force of truthfulness.Footnote 26 It does veer into fiction, however, as, although the events portrayed in the ‘Ishqnama are verifiable, at the same time, it draws metaphors, plot points, and allusions from literary characters who inhabit the fictional world of various masnavis. As mentioned, the characters of Layla and Majnun are directly and indirectly cited in the ‘Ishqnama text. As such, Wajid ‘Ali Shah and the events that take place in the ‘Ishqnama are both historical and fictional, the boundaries of which seem more blurred than in more conventional autobiographies. Hence, I have labelled the text semi-autobiographical. Even when I renarrativize the history of the ‘Ishqnama and its copies, it has been difficult to distinguish Wajid ‘Ali Shah, the historical figure, from Wajid ‘Ali Shah, the literary persona of a masnavi and vaqa'i manuscript. This conflation occurs even more easily in the copies since the literary components of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's character are concealed by the prose format.

This article proceeds in three steps. The following section introduces the ‘Ishqnama into its historical context in order to reconstruct Wajid ‘Ali Shah's political intentions in sponsoring this manuscript. I provide a brief history of the production of the ‘Ishqnama before turning to how Wajid ‘Ali's courtly self-image was connected to his mastery over the management of his lovers and courtiers. I call this an ‘erotics of sovereignty’, in which desirous attachments become the cornerstone of how Wajid ‘Ali Shah creates affective and political relationships within his court. As a result, in his scheme of erotics, in which his political and personal interactions are imbued with desire and sex, power operates in a strict hierarchical fashion, with him at the top, rather than in a dispersive or horizontal manner through a web of relationships. He does so by placing his corporeal body, and thereby loyalty to his body, at centre stage. This allows Wajid ‘Ali Shah to flatten the complexities of his relationships, as the personal details of his female companions are provided only to service Wajid ‘Ali Shah's power as a ruler and as a lover.

The last two sections are about the discursive constraints placed on the ‘Ishqnama since it has been read mostly through its print and lithograph copies, produced from 1848 to 1965, which are colloquially known as Parikhana. In the third section, by turning to the copies of the ‘Ishqnama, I trace the various textual and visual transformations in the Parikhana, including the complete omission of the ‘Ishqnama's paintings. The fourth section reviews how the sexuality of Wajid ‘Ali Shah was a site of offence under the colonial gaze. As such, scholars have been less likely to focus on the intimacy conveyed in the ‘Ishqnama's text, not so much because the text was devoid of politics, but because it seemingly echoes the colonial narrative. In this light, I reassess how the ‘Ishqnama has been received in academic discourse and popular culture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, either diverging from or enhancing this colonial framework of debauchery. The heart of this article is about the afterlife of the ‘Ishqnama manuscript: the practices of transmission that have flattened the ‘Ishqnama's political nuances and glossed it into little more than a sexual autobiography.

Ur-manuscript of the ‘Ishqnama

In this section, I seek to address the structure of the ‘Ishqnama and its politics of intimacy and sex. First I consider the ‘Ishqnama and its relationship to other similar historical and literary texts such as Wajid ‘Ali Shah's Divan. In rereading the ‘Ishqnama, I argue that Wajid ‘Ali Shah deployed the text and visuals to showcase his sovereignty through the depiction of truthful events such as the punishment of his lovers and management of his estate. Factual historical events are only one feature of the manuscript as Wajid ‘Ali Shah weaves intimate sexual moments into his narrative in a hyperbolic, emotive language to emphasize how his management of his household mirrors his handling of the Avadh state. Wajid ‘Ali Shah undertakes such a balance by utilizing Urdu poetry to assert his connection to an Indo-Persianate past and to align himself with Indo-Persianate rules of proper comportment for leaders, such as justice. Thus, the manuscript does not disavow pleasure and desire, but instead constrains them within the bounds of Persian and Urdu poetry. My brief foray into the structure of the ‘Ishqnama demonstrates that the language and aesthetics of sexual practices were a foundational component of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's political stagecraft.

Wajid ‘Ali Shah was born in 1822 and was named heir apparent by his father, Amjad ‘Ali Shah (r. 1842–47), in 1842 when the father bypassed his eldest son in favour of the younger brother. The complete ‘Ishqnama with painting and handwritten calligraphy was completed in 1849, when Wajid ‘Ali Shah was 27 years old and had been on the throne for two years. It is unclear whether Wajid ‘Ali Shah began the manuscript while still a prince or immediately after he ascended to power. The event with which the ‘Ishqnama begins is, as stated previously, Wajid ‘Ali Shah's embarking on his first sexual affair at age eight. Throughout this opening vignette and the rest of the historically specific episodes, the reader cannot be certain whether Wajid ‘Ali Shah kept a diary of his sexual behaviour and then mined this diary for his literary source material, or whether he created a new childhood narrative for himself in 1849. Compounding this confusion is the fact that Wajid ‘Ali Shah prevented any worker credit, as there is no signature of a calligrapher or artist to be found within the manuscript. As the manuscript's sole author and poet, Wajid ‘Ali Shah seemingly has complete narrative control, which leaves open the question of time. When exactly did Wajid ‘Ali Shah create this manuscript, and who exactly was his intended audience?

The year 1849 was an important one for Wajid ‘Ali Shah. He completed two immensely elaborate manuscripts: the ‘Ishqnama and the Divan (a collection of poems). Both manuscripts are physically quite large: the ‘Ishqnama is approximately 46.2 by 30.2 centimetres, while the Divan measures 41.2 by 26 centimetres. Their sizes indicate that, when the manuscripts were displayed in a courtly setting, only a few courtiers could huddle around them, forcing an intimate viewing experience. In addition, they both have the same cream-coloured paper and hashiya (border) design of gold and red. The Divan even includes a miniature of Wajid ‘Ali Shah sitting on his throne that bears an uncanny resemblance to throne scenes in the ‘Ishqnama.Footnote 27 Because of their visual resonances, the ‘Ishqnama and Divan should be seen together as part of Wajid ‘Ali's early imperial message. That both manuscripts are written in a poetic register speaks to the fact that Wajid ‘Ali considered poetry to enhance his sovereignty and the perfect means for conveying his authority. Moreover, in 1849, he minted a new coin. And, on a personal note, he witnessed the death of one of his sons from smallpox.

That same year also saw the arrival of a cantankerous British Resident, William Henry Sleeman, who, within his first five weeks as acting British Resident, had pushed for Wajid ‘Ali's removal.Footnote 28 Sleeman travelled through the Avadhi countryside collecting information for his report, which ended up accusing Wajid ‘Ali Shah and his administration of devastating Avadh financially and socially. In his two-volume memoir, Sleeman states that he witnessed a proliferation of crime, bribery, and extortion throughout Avadh. Wajid ‘Ali was described as ‘a crazy imbecile who is led like a child’ by the hands of a few ‘fiddlers, eunuchs, and poetasters’.Footnote 29 Sleeman suggested, in other words, that Wajid ‘Ali Shah was more interested in poets, eunuchs, and dancers than in running a responsible administration. The British government would later use Sleeman's report to justify its complete absorption of Avadhi territory.

While it would be tempting to suggest that Wajid ‘Ali created his manuscript to provide a direct counterpoint to Sleeman's account, manuscript production was too intensive a process to have been completed in the span of a few months. Given the high quality of the images and the elaborate hashiya, the ‘Ishqnama's production must have started at least a year before Sleeman's arrival, though Wajid ‘Ali Shah could have expedited the process once news circulated that Sleeman planned to submit such an antagonistic report. Indeed, a copy of the ‘Ishqnama currently in a depository in Pakistan contains the date of 1848, which suggests that the ‘Ishqnama was most likely planned out a year before Sleeman's arrival (see the third section of this article). In either case, Wajid ‘Ali Shah commissioned two manuscripts in a poetic register that espoused intimacy and intimate bonds as foundational to his rule, which was at odds with Sleeman's account. While Sleeman saw the members of his court as a liability, Wajid ‘Ali himself saw these dancers, musicians, and lovers as an asset to his power.

The ‘Ishqnama, as mentioned, has been read as an autobiographical text and has been taken as a chronicle of the true events of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's life. While ‘Ishqnama does follow principles of the vaqa'i genre by centring on the historical life of Wajid ‘Ali Shah, it also contains elements of the genre of the masnavi (literary narrative), especially in its opening lines and its thematic emphasis on the sacrality of love.Footnote 30 In tandem with the parameters of these multiple genre categories, the ‘Ishqnama positions Wajid ‘Ali Shah's personal and sexual life as an affective bond for his courtly politics. Wajid ‘Ali Shah reveals details of his life at court such as the enforcement of social and courtly hierarchies, the aggrandizement of his masculinity vis-à-vis his heterosexuality, and the disciplining and punishment of members of his court, all with varying shades of veracity.

In the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah never establishes a direct connection between his manuscript and older historical memoirs, but he does provide a genealogy of his royal investments for proper comportment. In the ‘Ishqnama, during a musical celebration, Wajid ‘Ali Shah makes note of historical figures who have influenced his courtly practices. He states:

If I heavily drink red wine / Then the foundation of pleasure (‘ishrat) has been laid

The heart of desire is prepared in this world / Through the beautiful agreeable Parīkhāna

Bygone (sābiq) sovereigns (salātīn) are celebrated / Because of their great many customs and manners (sha‘ār)

Such as Muḥammad Shāh of Delhi / Barāhīm ‘Adil Shāh [of Bijapur], who were renowned

Even though they were both kings (bādshāh) / By holding celebratory parties (maḥfil), they had a path of pleasure (‘ishrat)

… Every year they continuously gave their gifts (‘atā) / Thousands of gifts (bilak) they gave. A hundred thousand.

To the beautiful women who were cheerful and enchanting / They gave them an education in the sciences (‘ilm) of dance and other riches (g̠anā)

They titled these women ‘envy of the moon’ / They were all notable (mushtahar) singers.Footnote 31

Here, Wajid ‘Ali Shah is creating a historical lineage of proper manners (sha‘ār) and behaviour by recalling Indo-Muslim rulers who favoured the arts, such as Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah II (r. 1580–1627) and Muhammad Shah (r. 1719–48). These citations validate Wajid ‘Ali Shah's artistic and courtly investments in pleasure and support his creation of the music school, the Parīkhāna. Outside the ‘Ishqnama, Aloys Sprenger notably catalogued the library of the nawabs between 1848 and 1850, and compiled a list of major manuscripts in Persian, Arabic, and Hindi circulating in the court.Footnote 32 Within this catalogue, neither works authored by Adil Shah nor those of Muhammad Shah are directly mentioned. Therefore, a complete literary genealogy of the ‘Ishqnama may be impossible to reconstruct. While that front may remain opaque, Wajid ‘Ali Shah makes it quite clear that he is aligning himself with the norms of Ibrahim ‘Adil Shah II and Muhmmad Shah, notable musical patrons and poets who patronized aural poetics featuring sensual tropes to enhance their power.Footnote 33 With these investments in mind, it is no wonder that ‘Ishqnama was completed in a poetic register and positions the emotional power of desire as a cornerstone of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's sovereignty.

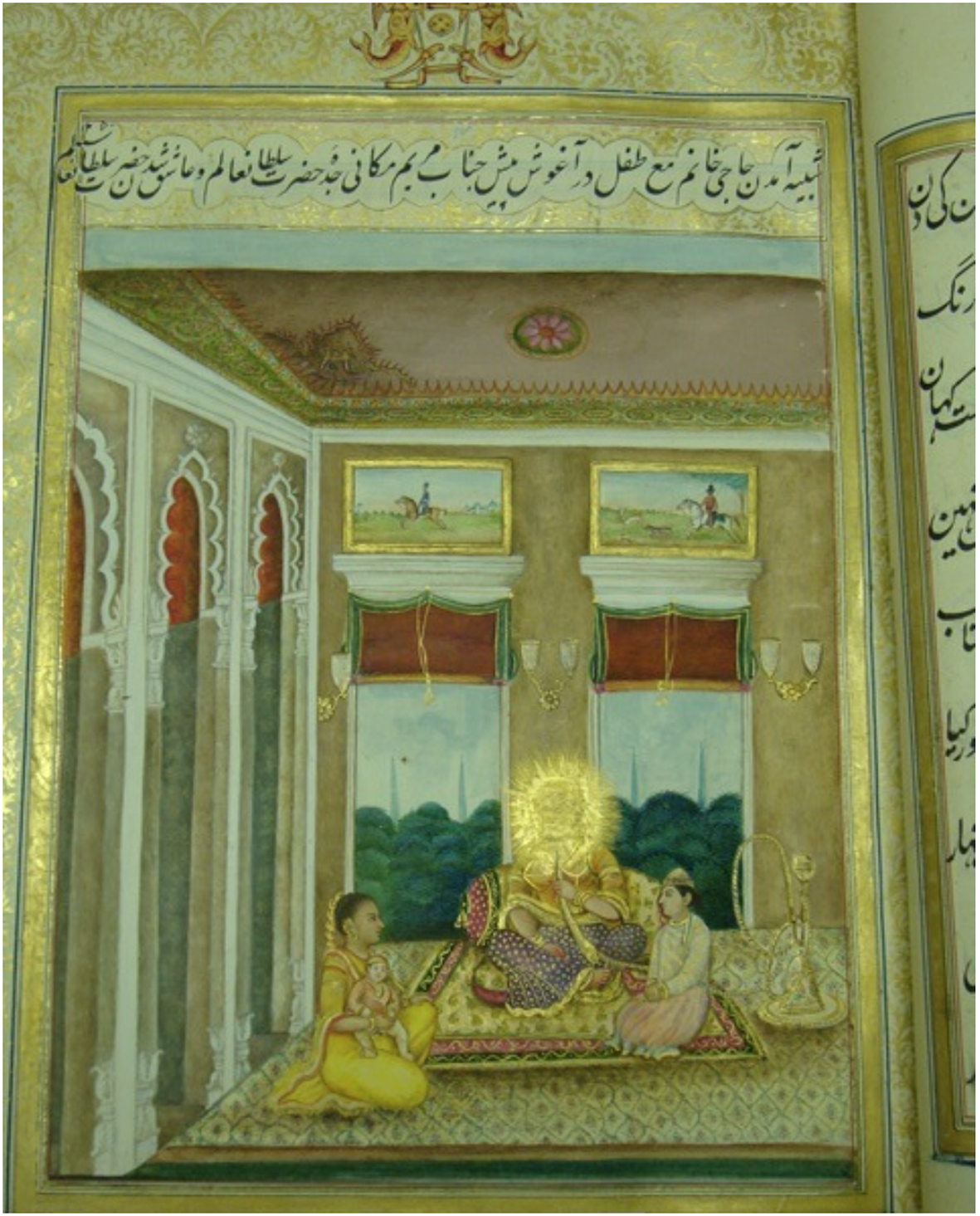

An important detail of the ‘Ishqnama text is the rumination on anecdotal accounts of servants’ physical appearances as a means to reinforcing Wajid ‘Ali Shah's dominance. Wajid ‘Ali Shah in the ‘Ishqnama surveys the bodies around him, stating, for example, that one lover, Rehiman, ‘is not beautiful, nor is her face insipid’.Footnote 34 He discloses personalized descriptions to both create and evince intimate bonds with his courtiers. While furnishing intimate details of the real-life women in Wajid ‘Ali's court, the ‘Ishqnama also visually represents them in a strict social hierarchy that reinforces the centrality of Wajid ‘Ali's power. Throughout the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah is the one of the few figures who is depicted with a halo. There is also a clear hierarchy among the females in his zenana. Wajid ‘Ali mentions that the stipends and allowances he gives to the women in his court are distributed according to rank. At times, women received a ‘hundred-rupee monthly allowance’.Footnote 35 In one dastan, Wajid ‘Ali Shah provides a full list of his lovers’ names and the new names he conferred on them once he was on the throne. Their names vary slightly, but the appellations affixed at the end are always bēgum, parī, or sahiba, which indicate their place within his court.Footnote 36 For exalted women in the ‘Ishqnama, their faces are hidden behind screens and plants. Take, for instance, the miniature of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's grandmother, Maryam Markani, whose face is shielded by a halo (Figure 1).Footnote 37 This is one of many images in which women of high stature are given licence to shield their faces from the painter's brush.

Figure 1. ‘Ishqnama, folio 12r. The prince falls in love with a visitor, Hajji Khanum, who has an infant child, while in the company of Maryam Markani. 1250/1834–35. RCIN 1005035. Source: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020.

When Wajid ‘Ali introduces a new woman or lover in his manuscript, he includes information about her rank and social status. If she is a servant, he lists the family that she is employed under. Social and filial relations are stressed. Regarding one of his servants, Bandi Umda Wali, Wajid ‘Ali mentions that he met her before he was crowned king (takht shāhī pe), when she worked in the house of Jahan (Numa).Footnote 38 He later decides to give Bandi Umda Wali the proper name (riẓā) of Matlub al-Sultan Hazrat Begum and to pay her a monthly salary of Rs 2,500.Footnote 39 For another servant, Wajid ‘Ali states he caught a glimpse of Amer Baksh while she was living in Hazoor Bagh. Through the intercession of Chote Khan, one of the drummers in Wajid ‘Ali's theatre, Amer Baksh is able to communicate with Wajid ‘Ali and to be given signs of his faith (‘aqīdat).Footnote 40 After that, Wajid ‘Ali finally is able to meet Amer Baksh in person. Wajid ‘Ali Shah emphasizes these social and filial relations to show that these women are vetted and that they have some kind of pre-existing relationship with members of his court before he allows them into his home.

In an effort to preserve a genealogy with his father's and grandfather's courts, Wajid ‘Ali retains members of their staff.Footnote 41 Because of this, Wajid ‘Ali decides to marry some of his late father's servants while freeing others. One such servant, Paro, who was previously employed in an exalted (ḵẖalad) house in Faizabad, enters Wajid ‘Ali's protection and is addressed thereafter as Arghawan Pari. In the later Parikhana copies, scribes suggest that Paro was the servant of none other than the Mirza Nasir al-din Haidar's late mother, Nawab Badshah Begum.Footnote 42 In the ‘Ishqnama, the name of Nawab Badshah Begum is never evoked, but only inferred. Through this act of employment, Wajid ‘Ali positions himself closer to the nawabi bloodline and its past courtly structure. In another instance, a courtier, Mir Muhammad Mehdi, recommends Umrao Begum as the new superintendent officer (‘ahd-darog̠a) for Wajid ‘Ali Shah's palace. Wajid ‘Ali accepts Mir Muhammad Mehdi's request because Umrao Begum is the sister of Nasir al-din Haidar's wife, Qudsia Begum, and her brother is Wafa Beg.Footnote 43 Despite her impressive lineage, Wajid ‘Ali is dismissive of her as his servant because of her corpulent (farbih) physique and the large number of moles on her face. Against his own sexual desires, Wajid ‘Ali Shah keeps Umrao Begum in his employ because she preserves the relationship between his father's cousin and his elite courtier. Wajid ‘Ali Shah even mentions that he permitted some of the female servants who were in his late grandfather's zenana to go to Karbala.Footnote 44

Notably, he discusses when the people in his household are connected to the Prophet or to Quranic and noble ancestors. In describing his first nikah marriage, to Naik Akhtar, who would later be titled Nawab Khas Mahal, Wajid ‘Ali notes that she was from the noble (ashraf) and exalted (buland) household of al-Daula ‘Ali, also known as Ahmad ‘Ali Khan. Jani Khanam, the grandmother of Wajid ‘Ali Shah, was the first to introduce Naik Akhtar as a possible match for Wajid ‘Ali because of her lineage (nisbat).Footnote 45 In another dastan, Wajid ‘Ali mentions that his uncle-in-law, ‘Ali Naqi Khan, was a sayyid—a title that suggests he was descended from the Prophet Muhammad.Footnote 46 Wajid ‘Ali extends these noble connections to his servants. He states that Insha Allah Khan, who was a great poet (shā‘ir) of the imagination and an eloquent poet (suḵẖun-dān) with intelligence (suḵẖun-fahm) and a sweet voice (shīrīn-maqāl), had three happy daughters. The eldest was Hederi Begum Muba Husain, the middle child was Muhammadi Begum, and the youngest (ḵẖurd-tar) was Nanhi Begum. They were escorted into the service of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's mother, where they recited marsiya during Muharram and the Urdu play of the Hindu god Indra.Footnote 47 Thus, these three sisters and their connection to Wajid ‘Ali Shah's court are first connected to Insha Allah Khan, a famous polyglot poet in Lucknow with ties to the Mughal court.

Through his marriages and by employing household servants, Wajid ‘Ali Shah links himself to Islamicate symbols of power such as descendants of the Prophet. As Gail Minault argues, Muslim men were subject to new pressures both political and socio-economic in nature throughout the nineteenth century as a result of colonial encounters. Consequently, the term sharif, which translates into ‘noble’ and which had a prior connotation of ‘birthright to position or wealth’, was subsequently transformed into a description of good character.Footnote 48 Therefore, in the nineteenth century, ashraf, the plural form of sharif, denoted respectability in terms of birth, religion, material resources, and caste. In the ‘Ishqnama, a lineage that goes back to the Prophet Muhammad could be a claim about Wajid ‘Ali Shah's piety or his noble character; in another sense, furthermore, it allows Wajid ‘Ali Shah to elevate the caste standing of the women in his court into ashraf.Footnote 49 Colonial officers consistently remarked on how many low-caste subjects made up Wajid ‘Ali Shah's retinue.Footnote 50 By providing citational claims of the ties between the women of his court and the Prophet, Wajid ‘Ali Shah rebuts these charges by making them members of an elevated status group. At the same time, Wajid ‘Ali Shah rewrites the record by blurring the gradations of power among the women of his court by indicating that were all of a high social status when in fact they came from various socio-economic positions.Footnote 51 In reality, given their unequal social roles, these women must have experienced a range of different forms of physical and psychic violence.

Throughout the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah casts only females as objects of desire. The heterosexualization of the pictorial motifs in the ‘Ishqnama was a response to the colonial discourse that sought to undermine Wajid ‘Ali Shah and previous nawabs through the accusation of homosexuality (see the fourth section of this article). In a different context, Afsaneh Najmabadi has argued that, during Iranian nationalism, there was a disappearance of the young boy as the site of romantic and mystical desire as a direct result of contact with Europeans.Footnote 52 The case of the ‘Ishqnama and Wajid ‘Ali Shah reinforces Najmabadi's argument. Because of the colonial discourse surrounding previous nawabs, Wajid ‘Ali Shah selected only females as his lovers, not only out of his personal predilection, but also to combat the colonial discourse of effeminization and homoeroticism. The only males who figure predominately in the ‘Ishqnama are eunuchs. Unlike the females in his zenana, the eunuchs continue to swear their loyalty to Wajid ‘Ali Shah. For Wajid ‘Ali Shah, they are never desired, and they are highly trusted.

Wajid ‘Ali Shah incorporates different female bedfellows from a range of classes and races into his court and zenana. By doing so, he stages his marriages and sexual affairs to showcase his virility and imperial power.Footnote 53 Each lover adds to Wajid ‘Ali Shah's power, since ‘symbolically the world, like his lovers’, is considered ‘under his protection’.Footnote 54 To adopt an adage, the personal was political. This is especially true for rulers like Wajid ‘Ali Shah, whose sexuality needed to be mastered, since it translated into an ‘idealised masculinity of kingship’.Footnote 55 In the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah makes sure to differentiate between mut'a, short-term marriages, and nikah marriages, which are permanent. He is emphatic that his lovers are under his protection, which ultimately displays and reinforces his kingship. However, Wajid ‘Ali Shah is very specific about who exactly is granted the benefits of his royal guardianship.

Throughout the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah performs his political sovereignty by emphasizing and idealizing his heterosexuality. This is evident in the dastan featuring Sahiba Khanum, an older servant in the employ of the nawabi court.Footnote 56 At this point, Wajid ‘Ali Shah is 19 years old and is married to his first wife, Naik Akhtar. A love blossoms between Wajid ‘Ali Shah and Sahiba Khanum as she sings ghazals and dances for him, and they revel in their shared affection for ganjifa cards.Footnote 57 During the course of his love affair with Sahiba Khanum, his wife suffers a miscarriage of their daughter, Murtaza Begum. The section, which directly follows the news of Murtaza Begum's death, is a matla’ ghazal that is devoted neither to his wife nor to his deceased daughter, but to Sahiba Khanum. Wajid ‘Ali Shah actively silences his wife's sorrow within the ‘Ishqnama's narrative structure in order to centre the narrative on himself and his sexual prowess. According to Wajid ‘Ali Shah's account, after his daughter's death, his wife, Naik Akhtar, acquiesces to his affair with Sahiba Khanum and decides Wajid ‘Ali Shah's desires (ḵẖẉāhish) should become hers as well.Footnote 58

The miniature of folio 32v shows Sahiba Khanum displaying her thigh. Sahiba Khanum heated a part of a sitar (guitar) and struck her left thigh multiple times, causing fresh wounds (zaḵẖm). In the dastan, she dresses the wound herself and then proceeds to limp toward Wajid ‘Ali Shah so that he can tend to her maimed (lang) leg (Figure 2). This narrative of self-branding is repeated a few times in the ‘Ishqnama. As a motif, it allows Wajid ‘Ali Shah to gain complete control over his lovers’ submissive bodies and showcase the intensity of his own emotions. The physical act of disfigurement is reinforced by the ‘Ishqnama's poetic vocabulary. In the case of Sahiba Khanum, her state is described as heated (garm) from her eyes to her physical well-being, which becomes fatigued (ta‘ab) under her inflamed passion. Instead of reading the Sahiba Khanum dastan as merely describing Wajid ‘Ali Shah's cruel behaviour toward his wife and daughter, the narrative structure is in place so that the emotional ties between him and his lovers become synonymous with the dependency of a court on their king and a king on his court.

Figure 2. ‘Ishqnama, folio 32v. Sahiba Khanum, a singer, shows the prince the burn on her thigh and receives sympathy. 1257 (1841–42). RCIN 1005035. Source: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020.

As in the Sahiba Khanum dastan, throughout the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah is accompanied by females. He is usually the only man in each pictorial scene. In this folio and in many others scattered throughout the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali constructs his sovereign subjectivity as an individual who pines after love. As in the Sahiba Khanum account, he is rarely pictorialized as actively engaging in bureaucratic matters. Expressing desire is not inimical to or an escape from rational governance. By reconsidering the politics of the ‘Ishqnama, we see that Wajid ‘Ali's governance occurs through his control of women such as Sahiba Khanum. His household, which includes his lovers, serves as a reflection of his state and his right to rule.

In another reading, however, the ‘Ishqnama offers varying levels of truthfulness about self-harm in the interest of aggrandizing the principal hero figure, Wajid ‘Ali Shah. The emotions of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's lovers are the most exaggerated. There are multiple instances in which his lovers become so jealous that they go beyond cases of self-harm such as the Sahiba Khanum dastan and move into the realm of attempted suicide. For instance, at his Chatterwala palace, one of his lovers, Nanhi Begum, goes to the top of a tower (burj) to end her life because she is jealous (rushk) of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's other lovers. Before she can commit suicide, Wajid ‘Ali Shah arrives and lectures her on her ‘irrational’ decision (‘āqil dūr).Footnote 59 He claims that suicide is born out of ignorance (jahālat) and brings ‘disgrace’ (ruswā).Footnote 60 She decides not to jump. Previously, Wajid ‘Ali did attempt suicide. He never labels his own actions as being against God, instead reserving such a judgement only for his lovers. In another dastan, the servant Hedari Begum attempts suicide (jān apnī dēnī pe ḥāẓir) by eating crushed (kūtā) glass because her desire (ārzū) for Wajid ‘Ali Shah is unrequited.Footnote 61 In the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah possesses such charisma that his lovers are bound to him and willing to sacrifice their lives. In the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali Shah's lovers are so enchanted by and in thrall to Wajid ‘Ali Shah that they no longer operate according to an austere ‘strategy of conduct’.Footnote 62 His magnetism is what binds his lovers, courtiers, and court to his rule.

In the ‘Ishqnama poetic narrative, one could argue that Wajid ‘Ali Shah's wives and lovers have some degree of power. When one of Wajid ‘Ali's servants and lovers, Umda Begum, attempts to leave the court, Naik Akhtar, Wajid ‘Ali's wife, argues that Umda cannot quit of her own volition because she was given by God and, as such, must abide by different rules.Footnote 63 Although Naik Akhtar appears to have some agency in confronting Umda, her actions ultimately benefit Wajid ‘Ali Shah, as Umda Begum is his lover. To this end, various lovers physically display their devotion to Wajid ‘Ali Shah through their suicide attempts, displaying their frenzied love for him. These macabre displays of affection evince how some of these women operated with a bit of agency. They are rewarded with more money and freedom after each unsuccessful attempt.

In the ‘Ishqnama, even when his wives disobey him, the bedroom still remains an extension of Wajid ‘Ali's rule and power. Throughout the ‘Ishqnama, it appears that Wajid ‘Ali Shah is overwrought with emotions. He is jealous. His lovers deceive him and run off with other men. In dastan 75, this exact scenario plays out with one of his lovers, Sar-faraz Pari, who betrays him by seeking the company of other men. As a result of his heartbreak (dard-e jigar), he becomes melancholic (shiddat g̠am).Footnote 64 His emotional pain manifests itself in his body. He is afflicted with (satānā) buboes (ḵẖiyārak), which are huge blisters on the lymph nodes. He is unable to stand properly and is extremely helpless (ma‘ẓūr). Through the course of his lovesickness for Sar-faraz Pari, he is driven to such a state of grief that he loses (farāmosh) his physical and emotional senses.Footnote 65 Shortly thereafter, he strikes his left thigh with a heated hookah pipe (qaliyān), which in effect duplicates the behaviour of his lovers who underwent similar trials and burned themselves out of love. When Wajid ‘Ali Shah reveals his scars (dāg̠) to Sar-faraz Pari, she frivolously (‘abs) laughs at his pain.Footnote 66 As this dastan illustrates, Wajid ‘Ali Shah's management of his household is not devoid of emotions. He expresses deep anguish at having to part with his lovers. They, in turn, do not always comply with his desires.

According to Wajid ‘Ali Shah, his effusive emotions are not a sign of weakness. Through the affective language of ‘ishq, Wajid ‘Ali Shah positions himself as the most esteemed ashiq, lover, for his court and his household. Further along in the ‘Ishqnama, Sar-faraz Pari becomes jealous, attempts suicide, and undergoes a self-imposed exile from the palace.Footnote 67 She returns to Wajid ‘Ali Shah after a short period of time and apologizes (‘uẓr). As a result, their ardent love (ātish shauq) resumes once again.Footnote 68 Wajid ‘Ali Shah uses this incident in which he seemingly loses control of his emotions and burns himself to showcase his emotional investment in his lovers and other courtly relationships. In addition, unlike some of his lovers, Wajid ‘Ali Shah always recovers from his passion. In a later dastan, Sar-faraz attempts suicide by consuming a diamond (almās) from a ring (nigīn).Footnote 69 In the narrative, Sar-faraz suffers more than Wajid ‘Ali. She even miscarries. The exact line is: ‘She fell out of pregnancy. And I [Wajid ‘Ali Shah] suffered.’Footnote 70 In the end, Wajid ‘Ali regains control over Sar-faraz by showcasing her misfortunes (muṣībat) and shifting the story back to his own emotions. Through narrative plot points such as his attempts at suicide and deep depression, Wajid ‘Ali shows that he grieves while at the same time these moments show his resilience. Through it all, he remains the central figure on which the entire narrative and the household pivot. Ultimately, Wajid ‘Ali Shah's suffering is part of his moral advancement that allows him to become a more just ruler, while the women are mere narrative devices so that he can attain emotional mastery over the emotions of others.

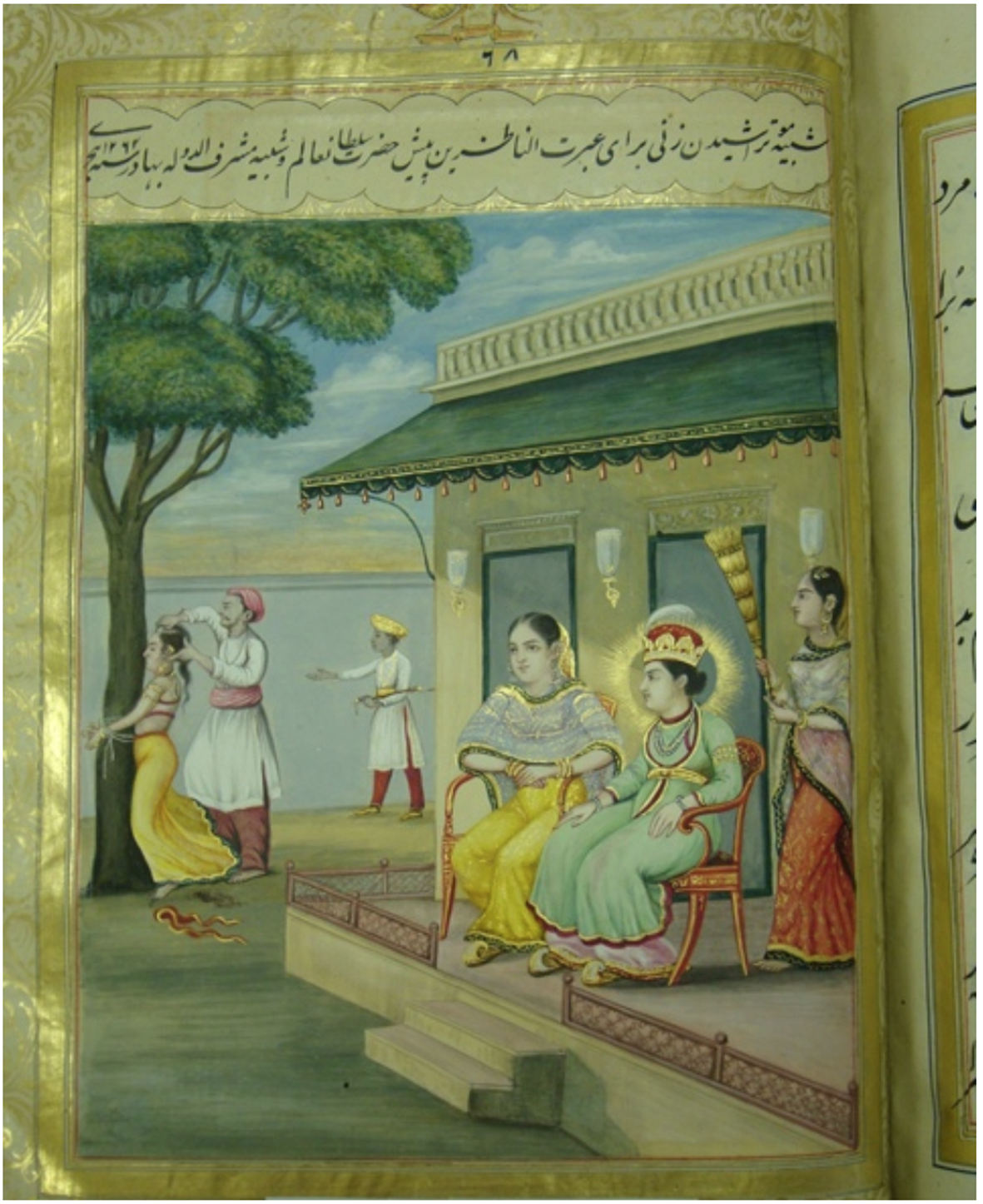

There are two dastans in the ‘Ishqnama that have been excised in later lithographs: dastan 66 and dastan 89. Focusing on one of them reveals the political subtleties at play in the original manuscript that have been lost in the later Parikhana copies. Dastan 66, which was excised from later Parikhana lithograph copies, is centred on a measured act of discipline, which ultimately highlights Wajid ‘Ali Shah's equanimity. In this dastan, Wajid ‘Ali doles out punishment to one of his female soldiers. His jurisprudence and measured response are symbolic of how he governs his court and his people.Footnote 71 Earlier on in the ‘Ishqnama, Wajid ‘Ali narrates that he created an army of women to protect himself, which consisted of mostly Turkish females. Previously, Wajid ‘Ali had attempted to reform his regular army, constituted of male soldiers, by introducing new disciplinary techniques. The East India Company put an end to his reforms and forced him to reduce the army.Footnote 72 By employing women, Wajid ‘Ali circumvents the colonial decrees meant to undermine his rule. For a short time, these Turkish women were his personal guards in his palace. Because of colonial regulations, Wajid ‘Ali Shah could not exert his authority over a touring army, but he had the means to discipline his intimate familiars.

In dastan 66, a member of his special troop is accused of deceitfulness (dagā). When he inquires after her (taḥqīq kiyā), members of his court reveal her relationship with a bath attendant (ḥammāmī). Wajid ‘Ali Shah's anger quickens at ‘her spreading lies’ (jhūt bātil) and he decides to use her as an example (ibrat) for his zenana. He consults shari‘a law (sharī‘at) and resolves to punish her by shaving her head (Figure 3).Footnote 73 In the miniature, the scene of punishment appears tranquil. Wajid ‘Ali Shah oversees her punishment with cool detachment. By punishing the Turk solider, Wajid ‘Ali demonstrates his ability to discipline those in his zenana. These scenes symbolically demonstrate how he treated his other courtly relationships. He was just and ethical by following the rules of shari‘a law, as in the case of the solider.

Figure 3. ‘Ishqnama, dastan 66, folio 233r. RCIN 1005035. Source: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020.

Here, it must be noted that many of his lovers were of Turkish or African descent, pointing explicitly to the question of slavery in Wajid ‘Ali Shah's court. The mechanism by which Wajid ‘Ali Shah recruited and enslaved these women who in effect served as reproductive pools needs further study. While many of these figures are marginal within the story, the ‘Ishqnama shines light on many of these lower-class women who were culled from local Indo-African households and recruited from Africa. Particularly, their specific geographic locale is pinpointed by their names, which are affixed with terms such as sīdī and zangī. In conjunction, generic markers such as colour further indicate that some of these women were of African descent. Indigenous terms associated with slavery, such as ghulām, bandī, and kanīz, are employed in the ‘Ishqnama not only to discuss these African women, but also to describe other women and men at Wajid ‘Ali Shah's court. In this case, slavery is not industrialized (i.e. chattel status). Instead, slavery in Avadh can be defined using the Richard Eaton's rubric of ‘the condition of uprooted outsiders, impoverished insiders—or the descendants of either—serving persons or institutions on which they are wholly dependent’.Footnote 74 In this case, the slave or courtier has total dependency on the court and on their master, Wajid ‘Ali Shah. Thus, the relationship is a ‘reciprocal, contractual’ one in which ‘the slave owe[s] obedience and loyalty as well as service and labor to the master, while the latter owe[s] protection and support to the slave’.Footnote 75 In thinking through these bonded sexual relationships in the ‘Ishqnama through the lens of slavery, the status differentials between Wajid Ali Shah and these women are emphasized. Thus, the concept of an erotics of sovereignty that I argue undergirds the ‘Ishqnama seeks to obfuscate the issue of consent and forced bondedness by focusing on love and desire as the driving forces behind Wajid ‘Ali Shah's relationships rather than coerced servitude. One productive aspect of the ‘Ishqnama manuscript is that it provides portraits of these enslaved women, which grants them a semblance of personhood. This differs from the copies, which further dehumanizes enslaved men and women by removing their images and visible presence.

Manuscripts were a costly enterprise. In this regard, Wajid ‘Ali Shah spared no expense, and the ‘Ishqnama was the most extravagant manuscript completed during his reign. Wajid ‘Ali Shah was not ashamed of his sexual history; he unabashedly circulated copies of the ‘Ishqnama during his exile in Calcutta. Copies were completed in both lithograph and handwritten forms, and news of the ‘Ishqnama's production likely travelled to other neighbouring courts through word-of-mouth transmission.Footnote 76

The Parikhana and the other copies

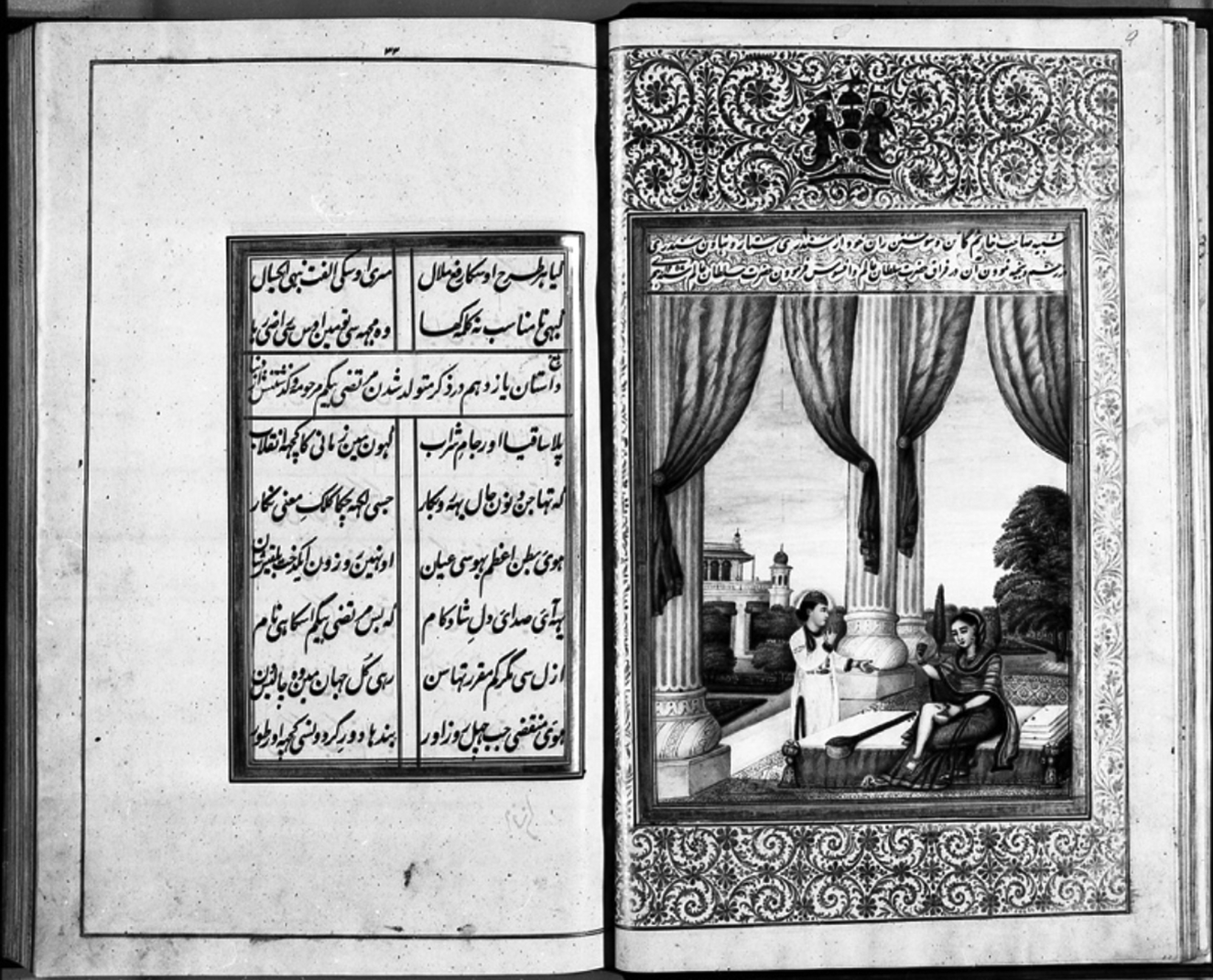

Up to this point, for simplicity, I have referred to the lithograph copies as the Parikhana. Although this was the title of one of the lithographs, the history of their transmission entails a knottier story. There were various copies published with various titles, undertaken by various translators. Scribes first copied the ‘Ishqnama in 1848, prior to the manuscript's completion in 1849. This copy will hitherto be referred to as the Lahore Manuscript. It was the first copy to transform the ‘Ishqnama's poetry into prose. After that, there are scattered references to now missing copies that were printed in poetic verse during Wajid ‘Ali Shah's exile in Calcutta from 1856 to 1887. Two other lithograph copies, entitled Mahal Khana Shahi (The Royal King's House) and Parikhana (Fairy House), followed. These later copies made a number of narrative and linguistic changes over the course of their publication from 1914 to 1965. By following this chain of transmission, the elisions of some of the ‘Ishqnama manuscript's dastans along with the removal of the poetic format and the images can be interrogated more thoroughly. This section moves in a schematic and chronological order to trace the evolution of these copies and their differences from the ‘Ishqnama manuscript.

The Lahore Manuscript was crafted as a handwritten facsimile in 1848 and is currently located in the Punjab University Library in Lahore. It is the earliest datable copy of the ‘Ishqnama manuscript, the only one to be completed purely in Persian, the first to transform the ‘Ishqnama's verse form into prose, and the first to remove all visual material. The Lahore Manuscript is identifiable as the first reproduction because of its textual contents. First, it contains the following poetry on its last folios: ‘To history, the hemistiches of Akhtar are spoken. From my opportunity [to observe] the conditions of women’ (Be tārīḵẖ in guftah miṣra‘-i aḵẖtar. Az aḥvāl naswān kardim furṣat).Footnote 77 These four lines do not appear in the ‘Ishqnama. They are found only in the Lahore Manuscript. The lines were later reprinted in the Mahal Khana Shahi (1914) and the Parikhana (1965) with minor edits.Footnote 78 Since the Mahal Khana Shahi and Parikhana retain these lines, it is clear that the respective authors of the Parikhana copies had access to either the Lahore Manuscript or some version of it such as the Mahal Khana Shahi.Footnote 79 Moreover, the Lahore Manuscript is the only version besides the ‘Ishqnama to mention the illustrations. Although the Lahore Manuscript does not contain any paintings, it does indicate when a picture appears, stating ‘a picture has been prepared’ (shabah taiyār shud). Such phrasing indicates that the writer(s) of the Lahore Manuscript either had direct access to the completed ‘Ishqnama or composed the Lahore Manuscript simultaneously with the creation of the paintings and manuscript of the ‘Ishqnama.

The Lahore Manuscript also contains the two dastans, namely dastans 66 and 89, found in the ‘Ishqnama that were later excised from lithograph copies of the Mahal Khana Shahi and Parikhana. One of the dastans, as mentioned in the previous section, describes Wajid ‘Ali Shah's ordering that one of his soldiers be whipped and her hair shaved. Given this inclusion, the scribes of the Lahore Manuscript must have read the original ‘Ishqnama, in which this dastan is illustrated and narrated (Figure 3). In the Lahore Manuscript, dastans 66 and 89 do not appear in sequential order with the rest of the dastans. A line is marked below the colophon, the last lines of the text, and the two dastans are written underneath as if the copyist realized his mistake and added them in haste. A subsequent copyist—for instance, the author of Mahal Khana Shahi of the 1914 edition—must have committed an error by not copying dastans 66 and 89, since they did not occur sequentially in the Lahore Manuscript. Another possibility is that the Mahal Khana Shahi author deliberately chose to excise this story.

Besides structural clues to the dating of the Lahore Manuscript, there is also an exact date in the colophon, which reads 1265/1848. The year 1849 is what is inscribed in the colophon of the ‘Ishqnama. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the ‘Ishqnama was initiated, at the latest, in 1848 and completed in 1849, during the first two years of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's rule. This means that either the scribe of the Lahore Manuscript obtained a version of the ‘Ishqnama before the calligrapher had finished the manuscript in 1849 or he copied the date in error. This date of 1265/1848 also appears in later copies, including the Mahal Khana Shahi and Parikhana. In the Mahal Khana Shahi, the lithograph bears the date of 1914, when it was completed, and the Hijra date of 1265, which aligns with the Lahore Manuscript and not the ‘Ishqnama.

The inclusion of elements of the Lahore Manuscript in later reproductions such as Mahal Khana Shahi and Parikhana—for instance, the same poetic language—bears witness to Wajid ‘Ali Shah's history of rebellion and exile. After the illustrated ‘Ishqnama was completed in 1849, Wajid ‘Ali Shah kept it in his possession until 1858, when British-allied soldiers raided his Lucknow palace. The soldiers subsequently gave the manuscript to their commanding superior, Sir John Lawrence, who presented it to Queen Victoria in 1859.Footnote 80 In a letter addressing the ‘Ishqnama manuscript, Sir John Lawrence states:

This book is curious and interesting from two circumstances. It was prepared in the Palace of Lucknow under the direction of the King of Oude, and is of course a faithful illustration of the life and dress of the highest Mahomedan families in India. Secondly, it was taken by some Seikhs [Sikhs] of one of the Punjabee Regiments at the time the Palace of Lucknow was stormed—they gave it to their commanding officer, who was good enough to present it to me, as the Corps was raised under my orders.Footnote 81

In 1859, Sir John Lawrence was already deeming the ‘Ishqnama a ‘faithful illustration of [Wajid ‘Ali Shah's] life’. He underscored the idea that the ‘Ishqnama had historical veracity. To this day, the manuscript resides in the Queen's library in Windsor Castle. Unlike some of the other Indian manuscripts housed there, this manuscript was never intended to be given to the English.Footnote 82 Since the ‘Ishqnama was taken from India in 1858, the only means for its story to continue circulating after 1858 was through an already extant copy such as the Lahore Manuscript. One might thus speculate that scribes utilized the Lahore Manuscript rather than the ‘Ishqnama because it was the only source of reference available in northern India.

The Lahore Manuscript is the only reproduction to be handwritten and not in a lithograph format, and its composition resembles an akhbarat (a proto-newspaper) containing a number of Persian scripts by different scribal hands with varying degrees of legibility. The visual aspect of this copy was an afterthought. It is completed in the shikasta and naskh scripts, which expedite writing, rather than the neat, clean nastaliq script used throughout the ‘Ishqnama. Furthermore, throughout the Lahore Manuscript, sentences and phrases are repeatedly crossed out. Given its perfunctory appearance, the Lahore Manuscript was most likely produced simultaneously with the ‘Ishqnama, serving as a kind of rough draft for Wajid ‘Ali Shah's artisans in his kitabkhana, hence its early date of 1265/1848. In the Lahore Manuscript's colophon, a title, ‘A Piece of History [qita‘ tārīkh]’, is included—a phrase that concludes both the Mahal Khana Shahi and the Parikhana copies, much like the specific phrasing of ‘To history, the hemistiches of Akhtar are spoken’. As mentioned, unlike these later copies, the Lahore Manuscript does not end there. The appearance of the two appended dastans suggests that the scribe copied the colophon too quickly before completing the correct order of the dastans. This likelihood reinforces the notion that the Lahore Manuscript served as a draft form of the ‘Ishqnama. Much of the commentary in the margins of the Lahore Manuscript contains potential chapter titles for the dastans and indicates when paintings appear. They also contain brief asides. The margins of the Lahore Manuscript thus point to another possible point of circulation. The presence of the marginalia may mean that various readers had access to the Lahore Manuscript and spent enough time studying it to offer commentary. In many cases, akhbarat were not only distributed textually in bound book form, but also orally disseminated. As with akhbarat, the appearance of the Lahore Manuscript was secondary because the orator would have read it out loud to a group of listeners who could not visually perceive the text. Wajid ‘Ali Shah may have elected to have two types of texts produced: one a handwritten copy that would have gained a wider audience through oral transmission and the other a luxurious manuscript copy for his own private courtly use.

There were also political and technological reasons for Wajid ‘Ali Shah's decision to disseminate both the ‘Ishqnama and the Lahore Manuscript in a handwritten form and not through a lithograph press. By 1820, Nawab Ghazi al-din Haidar (r. 1814–27) had established a lithograph printing press in Lucknow.Footnote 83 Aloys Sprenger, who catalogued the Lucknow Palace Library, noted that, by 1830, there was an active printing press, which increased the availability ‘of periodical and light literature’.Footnote 84 By 1849, 700 books had been lithographed in Lucknow and the nearby city of Cawnpore.Footnote 85 After a series of events, Wajid ‘Ali Shah abolished both the lithograph and printing presses from 1849 until 1857. He also closed down the Lucknow Observatory in 1849.Footnote 86 In his official statement on the matter, Wajid ‘Ali Shah argued that his court could no longer bear the expense and upkeep of both presses and the observatory. Yet British Resident Sleeman accused Wajid ‘Ali Shah of shutting down the press because it had printed and distributed an unflattering text: Qaisar ut-Tawārīkh. The author of Qaisar ut-Tawārīkh, Sayyid Kamal ud din Haidar, happened to be a ‘superintendent of the Avad observatory office’.Footnote 87 According to Sleeman, Wajid ‘Ali Shah closed down the press and observatory to take a stand against those who had undermined his authority. In either case, with the press no longer operational, Wajid ‘Ali Shah elected to transcribe and circulate the ‘Ishqnama as the handwritten Lahore Manuscript instead of reversing his earlier decree.

The question becomes this: why did Wajid ‘Ali Shah transform the ‘Ishqnama's Urdu poetry into Persian prose in the Lahore Manuscript? To take it from a different angle: as a poet himself, why did Wajid ‘Ali Shah elect to summarize the ‘Ishqnama in Persian prose? I propose that the dissemination of the Lahore Manuscript was somewhat accidental and not the only means for his story to circulate. Wajid ‘Ali Shah intended the Lahore Manuscript to be a rough draft of his ‘Ishqnama manuscript and only after the ‘Ishqnama manuscript was carried off in 1858 did he rely on the Lahore Manuscript as his only means of recalling the story. This would explain the Lahore Manuscript's sloppy appearance and its haphazard assembly. It is unclear whether Wajid ‘Ali Shah circulated the Lahore Manuscript in an akhbarat style of transmission before or after the ‘Ishqnama was forcibly removed from India in 1858. Another possibility is that, with the Lahore Manuscript as his guide, soon afterward, Wajid ‘Ali Shah lithographed the ‘Ishqnama in verse.

After the rebellion and while in exile in Calcutta, Wajid ‘Ali Shah was given a sizable pension of about a ‘hundred thousand rupees’. He spent some of his funds constructing a housing complex in Garden Reach (Matiya Burj), Calcutta, and re-establishing a printing press, Matba-e Sultani, in the area. Matba-e Sultani literally translates into ‘royal printing press’. Many of the books published by Matba-e Sultani were distributed free of charge from 1860 to 1885.Footnote 88 Wajid ‘Ali Shah thereby enabled a wider audience to gain access to his library collection and his writings.Footnote 89 Reversing his earlier order on the printing press, Wajid ‘Ali Shah published many of his poetry collections and novels through lithography during his exile in Calcutta.Footnote 90

I have so far been unable to locate the lithographed form of the ‘Ishqnama in poetic verse. Scant references to its existence appear in both Urdu and English.Footnote 91 The most intriguing citation is in the History of Avadh written by Najm ul-Ghani in 1919. In his fifth and final volume, Najm ul-Ghani utilizes the ‘Ishqnama extensively to reconstruct Wajid ‘Ali Shah's life and rule.Footnote 92 Najm ul-Ghani reproduces exact poetic verses that appear in the ‘Ishqnama manuscript and, I assume, in the missing lithographed copy. Before launching into a long quotation and summary of the ‘Ishqnama's Urdu poetry, Najm ul-Ghani states: ‘Wajid ‘Ali Shah (bādshāh) versified (mauzūn) in a mansavi the conditions (kaifīyat) of his youthfulness (shabāb).’ Further down, he demarcates the various versions of the ‘Ishqnama, stating: ‘[A]nd here and there (kahīṅ-kahīṅ) Wajid ‘Ali Shah's poetry (sher) on his palatial abode (maḥal) will also be copied (naql) word for word (bi-‘ainihi).’Footnote 93 Even though this versified copy (naql) that Najm ul-Ghani Rampuri refers to has not been located, it is clear that historians and a larger public as early as 1919 had access to it in a lithographed form. As such, the Lahore Manuscript, with its Persian prose, was not the primary mode by which readers consumed and comprehended the ‘Ishqnama. Instead, I contend that this missing lithograph copy of the ‘Ishqnama in poetic verse (mauzūn) served as the main material format for the Urdu-speaking public sphere from the 1860s to the 1910s. In preserving the poetry in this missing lithograph copy, Wajid ‘Ali Shah must have perceived that a reading public could understand the subtleties of his Urdu poetry. Significantly, at this point, Najm ul-Ghani Rampuri does not mention the retention of any signs of painting or hashiya decorations in the print copies. In only 50 years, the aesthetics of the print book had already greatly changed the original ‘Ishqnama manuscript.

Beyond the ‘Ishqnama copies, in Calcutta, lithography was an important technology for Wajid ‘Ali Shah, as the format allowed him to dispute many of the colonial myths that circulated about him. In one of his printed poems, entitled ‘From Lucknow to Kolkata’, Wajid ‘Ali Shah comments directly on the unfair treatment he has received from the British. He cites the toxicity of the Bengal landscape and the inescapable ecology of exile as his evidence. In one line, he ruminates: ‘Bengal is hot, it is charmingly barren (lūn) and it intensely (tapish) eats up everything.’Footnote 94 He further elaborates that ‘to whoever was alive (jānwar), he/it opened his/its mouth to him’.Footnote 95 In this poem, bodies both animal and human in the barren landscape of Bengal function as testimonials, bearing witness to the trauma, injustice, violence, and pain of exile. He dramatizes the inherent otherness of Bengal, suggesting that his own body is being transformed by the new landscape. He is ‘eaten up’ by Bengal. Noticeably, in the poem, Wajid ‘Ali Shah has no qualms about using his press to comment on politically charged topics in the poetic register.Footnote 96

‘Abdul Halim Sharar (1860–1926), who lived in the same area of Calcutta as Wajid ‘Ali Shah, attests to the fact that ‘Ishqnama copies circulated in the city in poetic verse.Footnote 97 As part of the ‘Muslim education and reform movement’, Sharar had a very low opinion of Wajid ‘Ali Shah and his ‘Ishqnama text, since it was of little educational value.Footnote 98 In a series of articles written in around 1913, Sharar penned his response to reading the ‘Ishqnama, stating:

The trouble was that the language of his [Mirza Shauq's] masnavīs was so beautiful, frank, pure, and clean in spite of its erotic allure (āshiqāna jaẓbāt), that even honorable and decent people could not abstain from reading and enjoying it. Wajid ‘Ali Shah also read these masnavīs, and because he was a poet himself, he adopted this style and versified (mauzūn) his love affairs and hundreds of the amorous escapades (rindāna ěʻtidālin) of his early youth. He made them public throughout the country and became to a conventional, moral, world a self-confessed criminal (mujrim). Few ministers and nobles in their early youth have not given full rein to their sexual desires (shahwat-parast).Footnote 99

Sharar states that he read a text of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's ‘love-affairs and hundreds of the amorous escapades (rindāna e‘tidālin) of his early youth’ that was completed in the ‘[masnavī] style and versified (mauzūn)’ form. Shahar's description of the ‘Ishqnama as a poetic copy is similar to Najm ul-Ghani Rampuri's specific terminology referring to a ‘versified masnavi’. Besides the charge of obscenity, Sharar's response also makes it evident that the lithograph press afforded Wajid ‘Ali Shah the opportunity to recover his poetic voice and distribute his poems and books to a large reading audience during his exile. With Shahar's and Najm ul-Ghani Rampur's strong testimonials, the existence of an ‘Ishqnama copy in poetic verse also validates Orsini's profound argument that earlier commercial publishers in northern India selected ‘texts of pleasure’—those that had resonance with an oral performative past.Footnote 100 Clearly, at the start of the twentieth century, the poetics of the ‘Ishqnama were still viable and were inherently a pleasurable part of the reading and listening experience for consuming the story. Wajid ‘Ali Shah's poetics, as Sharar's response strongly indicates, was judged for its aesthetic message and measured against those of other poets.

After the Lahore Manuscript and the missing poetic copy, the next extant ‘Ishqnama copies are from 1914 and 1926. Both are entitled Mahal Khana Shahi and are printed in Urdu, not Persian. They were circulated during the rise of vernacular print in India and under the auspices of the new obscenity laws that passed in the Indian Penal Code, section 292, which banned the distribution and sale of obscene books. Administrators began to enforce the code in 1862, but the law had wide-reaching effects only after the 1940s. This was also the period of British Repression in India that spanned 1907–47. These laws had very little effect on the distribution of the ‘Ishqnama copies, since British administrators did not disapprove of it. Only a handful of readers such as ‘Abdul Halim Sharar, not government officials, considered the text obscene (ashlil).

During the period when the Mahal Khana Shahi was published, obscene materials in Hindi were part of the ‘publishing boom’ in the area around Uttar Pradesh.Footnote 101 According to Charu Gupta: ‘The number of presses in Uttar Pradesh had risen from 177 in 1878–79 to 568 in 1901–02 and 743 in 1925–26.’Footnote 102 She states: ‘By the early twentieth century, wide-ranging pulp and popular literature—semi-pornographic sex manuals and romances in colloquial Hindi, thin tracts and small formats of songs and poems in Braj, flooded the market in Uttar Pradesh.’Footnote 103 The Mahal Khana Shahi operated for a slightly different public audience than these Hindi tracts because it was completed in Urdu. Nevertheless, Gupta's observations stand. Obscenity laws did little to curb the publication of erotic texts, since the term ‘obscene’ encompassed such a vast amount of literature. Only a few books were publicly vilified at the time. In 1927, Pandey Becan Sharma ‘Ugra's Chaklet was published—a story that ‘dealt with issues of sodomy, sexual acts between adult males and adolescent boys, and other aspects of male homosexuality’.Footnote 104 It garnered the most public and governmental ire. While readers such as Sharar might have disapproved of Mahal Khana Shahi, the text was never under state surveillance.

The debacca (introductions) of the Mahal Khana Shahi editions contain further information on the book's public reception. Abdahkar Mirza Fiza ‘Ali Khanjar, who created the first Mahal Khana Shahi copy in 1914, states in the foreword:

First off, ‘Ali Janāb Sheikh Muḥammad Yusuf Hussain Khān Sāhab Bahādar, who is a barrister of law in the noble city of Lucknow, should be thanked since he presented me with the gift of the ‘History of the Parikhana’, which was in his library. And through this celebrated (mamdūḥ) man's kindness, I was able to preserve and affirm my vision and desire for this book. From this a special type of excitement was born in my heart. And I picked up my pen on behalf of my translation. … I translated this disorganised (bē-tarattub) book and words completed in the shikasta script with little delicacy or excellence (faḵẖr).Footnote 105

Like other future copyists, Khanjar names the space in which he initially discovered the ‘Ishqnama text. He found a lithograph copy in the library of the lawyer Muhammad Yusuf Hussain Khan Sahab Bahadar, which speaks to the fact that the book had currency in middle- and upper-class Urdu-speaking circles. Khanjar further states:

This history (tārīḵẖ) of a society (ṣuḥbat) is not a society of a respectful lineage (nisbat). I must give a valuable request. Enough has occurred to know that his house (bait) is not the house (bait) of the world (jag). This man's misfortune (wāqiʻat) was that he was pleasure loving (‘aish pasand). In this manner of misfortune, my pen closed upon these events since the official (manṣab) duty (farẓ) of a historian (muwarraḵẖ) is to be faithful (rāst-bāz).Footnote 106

Khanjar positions himself as a historian whose duty (farẓ) is to honestly translate Wajid ‘Ali Shah's text. Khanjar's analysis of the ‘Ishqnama as a truthful history deviates slightly from Sharar's earlier stance positing the ‘Ishqnama as a history but also as a poetic descendant of Urdu poets such as Shauq. Sharar, unlike Khanjar, may have seen the ‘Ishqnama as part of Lucknow's Urdu repertoire because he read the text in the poetic format. By 1914, Khanjar may have had access only to a copy in prose. The only indication of which format Khanjar read is his comment that he read the book History of the Parikhana—a title that so far has not surfaced on a lithographed copy. In either case, whether Khanjar had access to the prose or the poetic copy, he considered the book a truthful representation of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's royal family and judged them to be obsessed with sex and pleasure (‘aish).

In response to Mahal Khana Shahi's popularity, Nami Press in Lucknow published a second edition in 1926 under the same title, and Abdahkar Mirza Fida Ali Khanjar is still credited as the author. The Mahal Khana Shahi copies of 1914 and 1926 mark the moment at which the ‘Ishqnama copies came to be distributed exclusively in a legible Urdu prose format. While the majority of the sentences are in prose, Mahal Khana Shahi does gesture to the ‘Ishqnama's poetic past by including a few ghazals. They appear at the end of certain dastans. However, these ghazals are not from the original ‘Ishqnama manuscript and appear to be Abdahkar Mirza Fida Ali Khanjar's invention. Many historians writing in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries utilized these two editions of 1914 and 1926 as references when researching and completing their books on the nawabate of Avadh.Footnote 107 But it is with these editions that the ‘Ishqnama and the reading public forsook the poetic register, as these copies were exclusively printed primarily in prose.

In 1965, the writer Tehsen Sarwari undertook the next ‘Ishqnama edition, entitled Parikhana. In the text, he made a number of linguistic edits.Footnote 108 First, as in the introduction of the Mahal Khana Shahi, there is a narrative of discovery to justify his translations. Tehsen Sarwari states:

One day, I went [to the house] of the Urdu author (Mulana Mufti Intizam Allah Sahib). There I saw a large (ḥajm) manuscript (qalamī kitāb) that needed new (jadīd) writing (ḵẖatt). However, the writing was written clearly and was in good shape. I took the book to privately study (mutāla‘a) it. After which, I knew that this was a rare (nā-yāb) manuscript copy (nusḵẖa) of the Persian language and that its name was the Parīkhāna written by the king (tāj-dār) of Avadh Wajid ‘Ali Shah Akhtar. As I continued to the read the book, my interest in it increased. An idea came to mind: this book should be in the Urdu language to respect its subject matter. Wajid ‘Ali Shah was attached to the Urdu language and manners (adab). In this regard, he composed a memorial of the Urdu language [in his writings]. Considering this, one has to ask why did Wajid ‘Ali Shah write and present [this manuscript] in Persian? No special reason comes to mind. Perhaps by doing so, Wajid ‘Ali Shah could transmit a state of royalty.Footnote 109

Like Khanjar before him, Tehsen Sarwari felt compelled to translate this text from Persian into Urdu. Later in his introduction, Tehsen Sarwari reveals that he was not translating from a pure Persian text, but was in fact reading a subsequent Urdu copy:

In Wajid ‘Ali Shah's book, he dispersed and mixed in short Persian poetic couplets that were not from Iran. Rather, in this manner, he wanted to reserve the Persian only for personal pronouns and verbs. The rest of the sections (ḥissa) are in Urdu. For this reason, I did not feel like I spent a lot of time translating the manuscript.Footnote 110

This description makes it clear that Tehsen Sarwari worked from some version of the Mahal Khana Shahi. He did not translate between languages, but modified the Urdu linguistic register from a florid Persianized Urdu into a simplified Urdu with a few Persian verbs. The simplification in Tehsen Sarwari's translation implies that there must have been a shift in audience and audience expectations for Urdu novels by the 1960s. The Mahal Khana Shahi's literary Urdu, which includes Persian terminology and metaphoric speech, gives way to the Parikhana's accessible Urdu register, which is very plain and direct. In the Parikhana, Tehsen Sarwari retains only half of the ghazals found in the Mahal Khana Shahi, further reducing the role of poetry in Wajid ‘Ali Shah's original manuscript and in his political thought.

Much like his prose, Tehsen Sarwari's analysis of the ‘Ishqnama is quite dry. He states:

From studying this book, I definitely knew that this was a story (dāstān) about an individual who became sick from engaging in and thinking about sex (jinsi marīẓ) for two years. Despite being king (bādshāh), he was a slave (gulām) to his desires (ḵẖẉāhishāt), and he was a weak (majbūr) and powerless (be-bas) person.Footnote 111

By the 1960s, as Tehsen Sarwari's introduction testifies, Wajid ‘Ali Shah and his text were disparaged for concentrating on the subject of sexual pleasure.Footnote 112

By focusing on the form of the ‘Ishqnama copies, we can better understand why Wajid ‘Ali and his book were considered deviant. For instance, the switch from poetry to prose in the copies masks the connections of the ‘Ishqnama to Indo-Persianate rules of comportment and justice. To this end, many of the translators of the ‘Ishqnama copies elide this connection and, in their introductory remarks, describe the ‘Ishqnama as historical non-fiction. Such a claim bolsters the idea that, during his tenure as nawab, Wajid ‘Ali Shah was so consumed by love and sex that he neglected statecraft.

Discomfort with the ‘Ishqnama manuscript

The ‘Ishqnama manuscript has received very little scholarly attention. And the few cultural figures who have remarked on the manuscript, including ‘Abdul Halim Sharar (1860–1926), Mildred Archer (1911–2005), and the director Satyajit Ray (1921–92), all equate the ‘Ishqnama with perversity and decadency. Beyond these few cases, there has been a general amnesia about the art historical, historical, and literary significance of the ‘Ishqnama manuscript. Just as importantly, when it does enter academic discourse, historians have drawn from the Urdu copies and not from the original manuscript.

Before turning to these figures, a word must be said about the archiving principle of non-normativity within the nawabi bloodline, which affected the reception of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's poems and his sexual practices. A discourse of native sexual non-normativity emerged under the British and was part and parcel of the British imperial and colonial project to undermine the political sovereignty of the nawabs and other native princes. The roots of this discourse began in the eighteenth century and stretched to the sunset of the nawabs’ reign in 1856. Colonial and imperial officers disparaged the role of women in the nawabi court, the nawabs’ clothing, their femininity, and their non-normative sexuality for the following nawabs: Shuja‘ al-Daula (r. 1754–75), Asaf al-Daula (r. 1775–97), Ghazi al-din Haidar (r. 1814–27), Nasir al-din Haidar (r. 1827–37), Muhammad ‘Ali Shah (r. 1837–42), and Amjad ‘Ali Shah (r. 1842–47). The last nawab, Wajid ‘Ali Shah (r. 1847–56), accrued all of his forefathers’ deviant signifiers. The role of empire and colonialism in characterizing the nawabs and their sexuality as excessive must not be forgotten when examining the reception of Wajid ‘Ali Shah's ‘Ishqnama.

A snapshot of this is found in the words of Captain Shakespeare, a British officer stationed in Avadh who wrote a dismissive report about Wajid ‘Ali Shah (r. 1847–56) to the governor general of India on 29 September 1845, stating:

The prospect that the present reign offers is truly a melancholy one and in case of anything happening to the King [Amjad ‘Ali Shah], I should much dread that the future will become still more clouded. The heir-apparent's [Wajid ‘Ali Shah] character holds out no promise of good. By all accounts his temper is capricious, and fickle, his days and nights are past in the female apartments and he appears wholly to have resigned himself to debauchery, dissipation and low pursuits, and for some time past has been on distant terms with his father [Amjad ‘Ali Shah].Footnote 113

For Shakespeare, Wajid ‘Ali Shah strayed far beyond the line of propriety in terms of his decorum and sexual practices. Shakespeare's authoritative text served as a technique of the modern British empire to impose its sovereignty and forcefully seize desired territory. His statement was later utilized in the 1855 Outram report, which justified the annexation of Avadh by depicting Wajid ‘Ali Shah as an unfit ruler. The report was named after James Outram, who served as the final British Resident of Avadh from 1854 to 1856. Much of Outram's rhetoric was an extension of Shakespeare's and Dalhousie's writings. Dalhousie, who had a low opinion of Wajid ‘Ali Shah, was appointed governor general of India from 1848 to 1856.Footnote 114 Together, these officers’ writings formed a citational chain that attempted to justify the deposal of Avadhi courtly culture.

After British annexation, Wajid ‘Ali Shah settled permanently in Calcutta, where he sought to recreate the former glory of his Lucknow court. One of the many inhabitants of Garden Reach (Matiya Burj), as the new courtly space came to be known, was ‘Abdul Halim Sharar, a historian, novelist, and reformer. Sharar's opinions about morality and state governance are quite visible in his literary output. The premise of one of his novels, Firdaus-i Birin (Paradise on Earth), for instance, centres on the dangers of superstitions to show the virtues of reason—a quality that Sharar believed Wajid ‘Ali Shah lacked.

Sharar was the first author to link Wajid ‘Ali Shah's debauchery with the ‘Ishqnama manuscript. In Hindustān men Mashriqī Tamaddun kā ākhirī Namūnah, originally printed as a series of articles around 1913, Sharar reserves his most scathing remarks for the last nawab, stating he was a ‘criminal (mujrim)’ for engaging in sexual affairs and publishing details on them.Footnote 115 He further explains his revulsion for the ‘Ishqnama, stating:

Wajid ‘Ali Shah has made public his sensuous transgressions (be-sharmi ki jarā’im). Wajid ‘Ali Shah could not outdo Nawab Mirza [Shauq] in the realm of poetry, so he decided to surpass him by proclaiming to the world his unchaste predilections (jaẓbāt), thoughts, and deeds. He even had no hesitation in showing shamefully (bāzāri mizāq) low taste (mubtaẓal) and in using obscene language (fāḥish alfāẓ). He would fall in love with female palanquin-bearers, courtesans (raṇḍī), domestic servants (ḵẖawās) and women who came in and out of the palace, in short with hundreds of women, and because he was heir to the throne, he had great success with his love-affairs, the shameful accounts (sharm-nāk dāstānin) of which can be read in his poems, writings and books. His character, therefore, appears to be one of the most dubious (nā-pāk) in all the records of history.Footnote 116