Introduction

It is commonplace to encounter an ascetic in a spiritual place, but few expect a middle-aged errant with overgrown fingernails and shredded socks on necrotized toes to be found on a university campus in India's capital. Even fewer imagine him to be caught claiming that with the advent of communism, madness in the world is coming to an end (Vidrohi in Bhasin Reference Bhasin2015). However, in the years 2014–15 it was an everyday experience for student activists at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) to pass by the ‘secular ascetic’ par excellence of campus politics. Ramashankar Yadav, commonly known as Vidrohi (the rebel), attended all campus protests, never missing any occasion to harangue the public and recite eccentric poems in Hindi and Awadhi. Although his landed and relatively wealthy family from a middle-caste background (Shah Reference Shah2012) regularly offered support to him (Akbar, interview 2015), he had voluntarily lived as a vagrant at this notoriously leftist university since the 1980s, sleeping in the Students’ Union office or out in the open. He was often called ‘comrade’ by the majority of socialist and Marxist-inspired campus activists, and he would incite students to get involved in political activities (Singh Reference Singh2015). Once a JNU student, Vidrohi refused the assistance of relatives and subsisted on food and cigarettes provided by the students. Arguably one of the best-known mascots of left activism in New Delhi, it did not come as a surprise when, a few days after his sudden death on 8 December 2015, a eulogy was released by the mouthpiece of a communist party: ‘Vidrohi died as he had lived—surrounded by students out on a protest march’ (Krishnan Reference Krishnan2016).Footnote 1 Ahead of a cremation ceremony that reverberated with slogans chanted by JNU students, the then president of the Students’ Union spoke about the only place Vidrohi belonged: campus activism.

When the JNUSU [JNU Students’ Union] results were declared, he told me one thing. As we know that he didn't keep books, notebooks or pen, but he had a small pocket diary, he came to me and said, Azad [anonymized], please write your number in this diary. He said, ‘now I can stay one more year in the union office.’ He looked sad but there was a hope and belief in his eyes. The way he lived his life, his departure was also spectacular [he had a cardiac arrest during a sit-in]. Those who want to go for his cremation they can go, but we also must take one responsibility. Comrade Vidrohi, whenever and wherever … he never used to miss protests and marches. The march will be incomplete if we don't fulfil his dreams.

While scholarship on Marxism in India places emphasis on the economic sphere, it rarely scrutinizes the subjective routine and empirical ambitions of resolutely leftist politicians and activists such as Vidrohi. Not only do the aspirations of controversial secular ascetics interrogate how participant cohorts challenge structures of domination in Indian society, they also question the way in which the understanding of such domination prompts attempts to transform oneself. These ‘technologies of the self’, described by Michel Foucault as ascetic practices of self-transformation (Foucault Reference Foucault, Hurley and Rabinow1997: 282), can be seen in the case of Vidrohi both as the expression of ideological world views and as ways to embody an ethical form of political activism (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2012). Such processes of subjectivation, enabling modes of understanding of oneself (Greenblatt Reference Greenblatt1980: 2), are at the core of this article's enquiry. Concentrating its focus on the realm of left political leadership, this article examines how the adoption of such an identifiable set of political practices and selective self-presentations (Goffman Reference Goffman1978, De Certeau Reference Certeau1990) and self-actions (Wagner Reference Wagner and Battaglia1995) aim at successfully representing Indians from various sociological backgrounds, in particular the weakest sections of political society.

The argument is based on 16 months of ethnographic fieldwork at JNU in 2014–2015,Footnote 2 complemented by shorter, follow-up field visits between 2016 and 2020. I contend that it is by engaging with oneself, through what left campus activists call declassed practices, that one acquires the legitimacy to claim representation of the collective whole, including its subaltern sections. As empirical analysis will illustrate, declassing comprises a form of biographical reconfiguration—temporary or long-lasting—involving a symbolic forfeiting of one's social status. Thus, here to declass means to eliminate one's perceived class. By delving into the semantic matrix of the word in practice, I understand class in a broad way—as a metonymic notion that includes class in the Marxist sense as well as alternative forms of social stratification based on caste and gender. The gradual changes leading to identification with a ‘subaltern identity’ (Guha Reference Guha1982)—that is, with the identity of subordinated sections of the Indian population—can also be described as a ‘minoritizing process’ involving a rejection of the identities included in the dominant categories of society (Brun and Galonnier Reference Brun and Galonnier2016).

This study describes how declassing involves the use of practical techniques—somatic, aesthetic, oratory, territorial, and intellectual—in order to renegotiate one's status and erase signs and habits attached to economic and social privileges. Seven elements at the core of this activist practice are introduced: dress-code refashioning, segregation of space, anger against society, martyr identification, nonconformist career aspirations, induced risks of political disengagement, and fasting. I present their demanding commitments and their compromises as life-changing experiences that are also burdened with doubts, material constraints, and moral rewards during a period of transition in these activists’ lives. In line with the anthropological epistemic community, I embrace the view that the political attitudes of campus activists—for the most part young people—are negotiated rather than determined during infancy, thus leading to the development of prefigurative and idiosyncratic views of the world (Nisbett Reference Nisbett2007, Jeffrey and Dyson Reference Jeffrey and Dyson2016).

To make sense of the political efficiency of the declassing practice, the analysis engages with its ability to draw creatively on ascetic and sacrificial tropes. My understanding of asceticism is both empirical and theoretical. An ascetic is broadly defined as a person ‘characterized by or suggesting the practice of severe self-discipline and abstention from all forms of indulgence’ (The Oxford Dictionary of English 2016). Detaching asceticism from the religious realm, here the term is used in a secular fashion, as an enduring performance of bodily practices (Freiberger Reference Freiberger2006) comprising frugality in public spaces and the display of a set of restrictive moral postures. Such postures include an expression of repugnance for contemporary material culture (Miller Reference Miller2001) and for signs of caste and class hierarchy. Built upon a leftist cult of sacrificial martyrs and a Marxist pro-poor aesthetic, such an approach also aims at garnering political benefits.

Conceptually, ascetic maceration is understood broadly as work applied to the self or, even more straightforwardly, as the ‘politics of ourselves’ (Foucault Reference Foucault and Rabinow1984: 340–344, Foucault Reference Foucault1993: 199–223). While grounding asceticism of sections of the Indian left within the cultural framework of South Asian politics and its vibrant history of democratic participation, I am referring to the term ‘ascetic’ and its attributes (cf. infra) in a broad sense, rather than to its specifically Indian conception. This implies that activists are not considered religious specialists (Gupta Reference Gupta1974), either irreversibly contemplative, reclusive world renouncers (Dumont Reference Dumont1960), sexually abstinent (Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke, Paul and Vanaik2002), or followers of the path of a religious guru, nor am I depicting them as particularly interested in embracing monastic careers—either prior to or while pursuing their political activities (Hausner Reference Hausner2007). Furthermore, here the term ‘asceticism’ does not suggest material conditions such as itinerancy or sedentariness in a religious site (Bouillier Reference Bouillier2015), which may lead to significant wealth accumulation (Van der Veer Reference Van der Veer1989: 459) and the gaining of political leverage through securing party tickets.

By portraying declassing as an essential socializing and political tool, this article stresses specifically the sociocultural and socio-economic tensions of this practice. It shows that declassing is widely adopted by the upper and middle classes along with upper and middle castes, while such notions are questioned—and sometimes rejected—by those at the bottom of the social ladder. The latter, including sections of the former Untouchable Dalit community and marginalized Muslims, prefer to emphasize social assertiveness alongside material aspirations for themselves as a way to achieve social justice. This suggests that for left political organizations, the meaning of declassing, and the representative call attached to it, is not universal and largely depends on one's social background. The term ‘representation’ will be understood not in terms of an achieved state of affairs (such as electorally based representation) but as micro and everyday claims of being representative by political actors (Saward Reference Saward2006, Tawa Lama-Rewal Reference Lama-Rewal2016). Therefore, representative claim-making consists of proposals that ‘might or might not be accepted, rejected or rearticulated by the represented’ (Dutoya and Hayat Reference Dutoya and Hayat2016).

The argument is based on the assumption that it is possible to look beyond the simmering political cleavages of left politics in India. Indeed, this rich nebula has a long tradition of factionalism and sectarianism, based on regional, ideological, and tactical divides.Footnote 3 The article mainly understands the Indian left through the lens of its activists who are part of the broad umbrella of communist movements. Although the degree and significance of left fashioning for the production of representative claims might vary from one left organization to another, I suggest that such practices are relevant, widely shared, and constitutive of the left modality of politics in India at large.

Left politics is presented here in a holistic manner and, although many functional differences exist between left parties and their various front organizations, I hypothesize that left self-fashioning in general can be grasped by looking at the politics of its student organizations. Because of historical developments, which I will go on to survey, I posit that campus activism at Jawaharlal Nehru University can be the eye of the needle through which to observe the wider political implications of self-transformations for left politics in India. Although the elitist academic standards of the university make JNU pedagogically quite singular, the pan-Indian reach of the university as well as the inclusive nature of its admission policy ensures high levels of regional, caste, and class diversity. Additionally, it is probably one of the few spaces in India that encapsulates such a rich and diverse range of competing left politics.

The first two sections of the article establish the background of the study. The first draws upon approaches to left refashioning in South Asia and underlines their relevance for the study of Indian politics. I then profile the actors involved in JNU student politics and unravel their historical relationship with the Indian left at large. The third section examines how the ‘middle classness’ of many activists at JNU is negotiated in light of the notion of declassing, and how such ideas are challenged by politically active sections of Dalits and Muslims. It acknowledges the polyphony of declassing practices through surveying their oratory, visual, spatial, identificational, gendered, linguistic, moral, emotional, and corporeal components. The section also engages with the long-lasting consequences of left self-fashioning through a discussion of activist disengagement and their professional trajectories after their JNU years. While it recognizes that left self-fashioning can be renounced—thus leading individuals to quit activism—it also shows that their sustained political commitments have left a durable impact on their lives. Notably, former JNU student activists espouse academia and turn their backs on careers in the private sector and non-educational administration. In the final section I engage with the declassed expressions of feminist assertiveness and the moral injunctions towards defeminization that they entail for left female activists. The article explains how, overall, the social practice under study differs from religious and Hindu nationalist forms of political asceticism, and how it ultimately serves as a legitimizing political device in the eyes of the larger political community.

Self-fashioning, declassification, and the Indian left: a theoretical perspective

The micro-practices of subject-formation are central in understanding sociopolitical transformations. As noted by Ong (Reference Ong1996: 738), the process of becoming a subject is entangled in a dual process of self-making and being-made, occurring within ‘webs of power’ connected to civil society, the state, and political upbringing. The post-colonial canvas against which Indian ‘subject-ifications’ unfold has been researched extensively by Subaltern studies scholars (for example, Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee1986, Reference Chatterjee1989; Kaviraj Reference Kaviraj2005). Enriching this approach, a growing body of literature substantiates the study of self-making by looking at the way in which identity formation engages with post-colonial political ideologies such as Hindu nationalism, Nehruvian socialism, and economic liberalization (Chandra and Majumder Reference Chandra and Majumder2013).

Along with those three political fixtures of Indian modernity, Marxism historically constitutes a vigorous political force in the post-independence Indian landscape. Its locally embedded political machinery (Bhattacharyya Reference Bhattacharyya2009) as well as its hegemonic political culture (Joshi and Josh Reference Joshi and Josh2011) led many—sympathizers, cadres, activists, leaders—to become a communist (Dasgupta Reference Dasgupta, Nigam, Menon and Palshikar2014). Notwithstanding its internal discords and the decline of its influence nationally, competing streams of communism in India have produced a distinctive and enduring Marxist discourse in various locations throughout the country, in and beyond the states of West Bengal, Kerala, and Tripura where communist governments have been in power for an extended period of time.

The effects of such historical developments are likely to have contributed to the formation of a distinctive Marxist political modality in India. As noted by Dasgupta (Reference Dasgupta2005), the collective embracing of Marxism in Bengal could not have taken place without a contextual convergence of politics and culture. However, the doctrinaire stress of Marxism on labour and the state superstructure blinds it to the idiographic emergence of Marxist selves locally. Thus, conventional accounts undermine the ways by which the subjective concerns of Marxist selves help to legitimize communist narratives and representations in the context of India.

Since shared identification with communist figures is informative about the imagination and aspirations of its followers, such affective processes constitute an analytical entry point into the contemporary political relevance of Marxist self-making. For instance, Jaoul (Reference Jaoul2011), who in his study of the agricultural wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI(ML)) in the state of Bihar, exemplifies how the appropriation of the Party by the poor and vice versa is achieved locally through subjective identification with sacrificial workers, peasants, and party cadres. One of them was Manju Devi, a young female activist who was murdered by a landlord militia and for whom a statue was commissioned. The account indicates that such figures encourage Party workers to change themselves and live the frugal life of a rural peasant to build ‘a long-term relation with the poor’ (ibid.: 369) and fight landed and wealthy oppressors.

As the case of Manju Devi indicates, a feature of various leftist movements in South Asia is the secular devotion towards martyrs, which provide exemplary role models in the pursuit of activists’ self-fashioning. They are described in the literature as ‘pure’ examples of self-sacrifice for a just cause (Lecomte-Tilouine Reference Lecomte-Tilouine2006) and exemplary figures involved in the efforts to determine historical truth (Verdery Reference Verdery2013, Vaidik Reference Vaidik2013). Ram (Reference Ram2016), locating martyrdom (rakthasakshithvam) practices among the youth wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) in the southern state of Kerala, underlines their inherent non-religious nature and their relevance as sociocultural institutions. Left self-fashioning thus nurtures close ties with leading sacrificial figures. As illustrated by Moffat (Reference Moffat2018), the great martyrs (shaheed-e-azam) such as the communist freedom fighter Bhagat Singh—executed by the British Raj—act as ‘historical spectres’ for future generations of activists, haunting contemporary political selves to complete the revolution left unfinished at Indian Independence.

Accounts of Maoist-led civil war in Nepal (1996–2006) also emphasize the importance of emulating selfless martyrs in order to become subjectively a dedicated member of the revolutionary community. Lecomte-Tilouine (Reference Lecomte-Tilouine2006) insists on the thaumaturgic effect of sacrifice in Maobadi guerrilla groups; through her anthropological study she shows how violence and sacrifice for the cause is omnipresent in the accounts produced by the wartime Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), and how such behaviour is attached to a privileged modality, either Brahmanic or kingly. Ramirez (Reference Ramirez2002) notes that the Nepalese Maoist guerrilla relies on the heroism of martyrdom to develop a sense of personal offering to the high end of revolution. Even in a post-conflict context, this sense of internal struggle, battle against selfishness, and continuous experience of self-improvement was found in the psyche and recruitment strategies of Nepalese activists of the Young Communist League (the Maoist youth wing) (Hirslund Reference Hirslund2012). In a similar fashion, Snellinger (Reference Snellinger2012) notes that it is the narrative of suffering and sacrifice that underpins the notion of political public service for Nepali student activists (see also Zharkevich Reference Zharkevich2009).

The ascetic moulds of self-transformation generated through secular leftist politics can be further evidenced through a consideration of the fighting practices of former separatist guerrillas in Sri Lanka, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). While many of its ideologues were both Marxist-Leninists and secular Tamil nationalists, the leadership requested supporters to venerate deceased fighters as ascetics (sannyasis) who fought for a common cause, thus renouncing egoistic personal desires (Chandrakanthan Reference Chandrakanthan and Wilson2000, Shalk Reference Shalk1997). Natali (Reference Natali2004, Reference Natali2008) indicates that the veneration of Great Heroes (Maavenaar) is made through the establishment of graveyards which are compared to Hindu temples and in which ‘gods are seeded’. Roberts (Reference Roberts2005) suggests the existence of a form of cross-fertilization between religious idioms and LTTE secularism, in which ‘enchantment’ is nestled amid rational discourses. At a more general level, such cross-fertilization draws on the more general ability to appropriate and reinterpret dominant cultural idioms to envision a ‘new man’ (Sorensen Reference Sorensen and Sorensen2007: 27–33, Tromly Reference Tromly2012, Salton-Cox Reference Salton-Cox2013), whether it is nested in Marxist Christianism (Dussel Reference Dussel2003), Marxist Protestantism (Crossley Reference Crossley2018), Black Marxism (Robinson Reference Robinson1983), or Feminist Marxism (Barrett Reference Barrett2014).

Left biographical reconfigurations in India do not always unfold in conditions of war, internal or external (Menon Reference Menon2016). Dasgupta (Reference Dasgupta, Nigam, Menon and Palshikar2014), for instance, examines how the ‘body-politics of asceticism’ is constitutive of the self-making of CPI(M) Bengali communists who ruled the state from 1977 to 2011. While communist activists ‘simply cannot stand holy men’ (Reference Dasgupta, Nigam, Menon and Palshikar2014: 85), their ascetic self-styling is depicted as a secular reconfiguration of a theological political culture in circulation in South Asia. Their memoirs—many but not all from CPI(M)—reveal a form of conversion to a new kind of ascetic subjectivity, based on severe self-cultivation, physical regimentation, body deprivation, and firm control over desires (Reference Dasgupta, Nigam, Menon and Palshikar2014: 78–79).

Left self-fashioning in the literature on South Asia is often described as a practice of a certain social elite or cultured middle class, which is traditionally over-represented in the ruling sections of ‘radical’ political organizations (Kennedy and King Reference Kennedy and King2013). This is exemplified again by Dasgupta (Reference Dasgupta2005), who shows how Marxism, embraced by the pre-independence Bengali middle-class gentry (madhyabitta bhadralok), was inspired by the redeeming praises of intellectuals and poets such as the bohemian Marxist Samar Sen (1916–87). The ecstatic and dark romantic culture of the social group, comprising upper-caste Hindu landed elite, petty landowners, traders, and indigent literati, shaped the expression of Marxism in Bengal, making the ‘rebellion merge with revolution’ (ibid.: 87).

Armed guerrillas are not the only ones embracing the figure of the renouncer. Chandra (Reference Chandra2013) describes how several indigenous rights activists in India's tribal belt developed a ‘radical bourgeois self’ in order to disavow privileges of birth and the ordinary temptations of middle-class life. He notes, ‘the radical bourgeois self … sacrifices the ordinary householder's existence to pursue a distinctively Indian kind of individualism and freedom’ (ibid.: 2). Through examining their self-narratives, he suggests that the activist ascetic renunciation and the Marxian biographical reconfiguration can be understood as an exchange of capital, in which the Indian bourgeois exchanges economic capital in the form of material privileges for symbolic capital in the form of status and rank (ibid.: 4). The subaltern speaking in the name of deprived tribal populations becomes for the activist a tool for a personal post-materialist quest (ibid.: 41), which can lead to a misrepresentation of the actual grievances of local populations (Mawdsley Reference Mawdsley1998, Shah Reference Shah2012).

Clearly, left self-fashioning is associated with a language of self-renunciation that underlines paradoxical, yet striking, similarities with another form of self-fashioning: Hindu asceticism. Kaviraj (Reference Kaviraj, Strauss and O'Brien2007), who draws parallels between a class-/caste-based cultural production and the deployment of Marxism in South Asia, approaches the issue from a theoretical standpoint. He compares the erudite mastery of Marxist literature and historiography (in English mostly) by communist political leaders to the esoteric Sanskrit scholarship dominated by Brahman castes—who had the monopoly over religious exegesis. He argues that the assimilation of the abstract language of Western enlightenment, along with the willingness to understand the imported notion of class—and not the India-specific one of caste—as the universal grammar of social inequality gave Indian Marxism ‘Brahmanical’ overtones. As a result, the biographies of upper caste left leaders are full of references to their determined frugal morale.Footnote 4

Others insist on the self-fashioning politics of moral purification developed by radical left political figures. An example can be found in the ethnography of contemporary Maoist armed insurgency in the Indian states of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh by Shah (Reference Shah2012). She argues that the fixed imaginary of Maoist renunciation embraced by veteran guerrillas, based on the concept of semi-feudal and semi-colonial exploitation, is no longer in tune with the political economy of mining in occupied areas. She gives the example of Gyan (see also Shah Reference Shah2014), an old-time Maoist leader who was known as a Hindu renouncer, ‘poring over Vedic texts [Hindu scriptures] and sitting on the Ganges's banks for hours’, before turning to armed communist militancy. Through the example of Gyan, Shah underlines how material renunciation continues into militancy, thus highlighting the ideological importance of the figure of the renouncer for the making of dedicated communist revolutionaries (ibid.: 342).

In these accounts, the outcome of political movements is largely unaffected by activists’ biographical reconfigurations. Self-fashioning appears as a by-product of activists’ ideologically informed attitudes and commitments, yet little is known about the legitimizing effects of such self-fashioning. A theoretical insight to make sense of biographical reconfigurations in shaping left representative claims is the concept of declassifying developed by Jacques Rancière (1940–). In the sociological tradition, to declass refers to a process, real or perceived, of descending in social mobility (Goblot Reference Goblot2015 [1925]). In this sense, being declassed is either the result of the eroding value of academic diplomas in a climate of mass education or due to the inability of new generations to attain a social status equivalent to that of their parents (Eckert Reference Eckert2014).

Departing from such approaches, Rancière defines the twin notion of declassification and disidentification as processes by which individuals abandon their predetermined social roles, enabling them to take up the cause of others (Rancière Reference Rancière1998: 212, 219–220, Blechman et al. Reference Blechman, Chari and Hasan2005: 288). Declassification is the way in which citizens escape the determinism of a social order that he calls the police, in which individuals’ distribution of places and roles is clearly identified and legitimized (Rancière Reference Rancière1999: 28). Processes of disidentification lead to the formation of political subjects who claim identities at odds with those defined by the social categories to which they belong—according to the police order (ibid.: 38).

Rancière theorizes a practice of self-fashioning that involves a rejection of one's socially fixed identity. Tassin (Reference Tassin2014: 158) understands this as an écart à soi (deviation from yourself), a transgression that enables individuals to bridge the gap between themselves and those displaying different pre-identifications based on gender, class, race, and so on (Rancière Reference Rancière and Rancière2004, Panopoulos Reference Panopoulos, Cornu and Vermeren2006). This overcoming of historically contingent social configurations is, for Rancière (Reference Rancière2005: 56), the definition of both politics and democracy as it produces egalitarian claims in which a universally shared meaning is produced (ibid.: 49). The practice of declassification leads to the inclusion of the ‘uncounted and the stigmatized’ (Rancière Reference Rancière2008: 560), not through identity politics and self-representation (Girola et al. Reference Girola, Leibovici, Murard and Tassin2014: 11), but through collectively claiming the impossibility of a particular form of identification. In return, discourses of disidentification—of breaking from an extant order—enable individuals to embrace subaltern identities and create political bonds (Norval Reference Norval2012).Footnote 5 Because social divisions imply that a section of a given community presents itself as the expression of the group as a whole, a ‘certain particularity’ has to assume a function of universal political representation (Laclau Reference Laclau and Panizza2005: 40–49). Such particularity carries the potential to challenge the social order precisely because it is capable of producing a political discourse under which discrete groups are ‘made equivalent’, thus facilitating collective mobilization (Laclau Reference Laclau1996: 70).

Keeping in mind the context of the study, I understand disidentification as a modality by which the Indian left claims, within the democratic public arena (Cefaï Reference Cefaï2016), universalistic representation against political adversaries (Mouffe Reference Mouffe2013). I specifically show how Rancière's concept offers an analytical lens through which we can comprehend the attempt by left activists—in particular those from non-subaltern backgrounds—to squander the social capital associated with their class, caste, and gender in the effort to claim representation for the downtrodden.

In a political space marked by abysmal inequalities, disidentification could be a powerful way for social elites to make the miscounted visible (Lievens Reference Lievens2014: 12) and affirm equality in the name of all. In a vernacularized democratic space in which assertions of caste, religion, ethnicity, and language constitute the backbone of its polity, disidentification constitutes a missing analytical link. It helps qualify and clarify the conflict over political representation between the left and proponents of identity politics in its various forms, who advocate recognition and redistribution while fighting against both invisibility and voicelessness. Through a case study of left politics on the JNU campus, the following sections show the reality of this tension and the political success of the practice of disidentification/declassification.

The voice of the left: student activism, academic elitism, and middle classness at JNU

JNU is a prestigious, English-medium, residential university (JNU 2018–19) with a long-running left culture and a vibrant student politics scene, in which the student wings of several regional and national left political streams are showcased (Singh and Dasgupta Reference Singh and Dasgupta2019). Neither apolitical nor grievance-based, student participation at JNU is, to follow Altbach's terminology (Reference Altbach1968, Reference Altbach, Forest and Altbach2006), primarily value oriented. Because campus activism at JNU revolves around ideational debates and not solely around material demands (Thapar Reference Thapar2016), it shares a similar strand of youth politics with the University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad Central University (Telangana), Jadavpur University, Presidency University (West Bengal), Allahabad University (Uttar Pradesh), and the Film and Television Institute of India (Maharashtra) (Garalytė Reference Garalytė2015, Deshpande Reference Deshpande2016, Pathania Reference Pathania2018). Like JNU, most of the politicized institutions of higher education are public, centrally funded, postgraduate-oriented, and teach predominantly social sciences and humanities subjects (Martelli and Garalytė Reference Martelli and Garalytė2020a). The emphasis on values is also visible in other niche educational spaces where liberal and post-materialist assertions such as autonomy, self-expression, and quality of life are made (Martelli Reference Martelli2017, Savory Fuller Reference Savory Fuller2018).

Broadly speaking, the type of activism at JNU contrasts with two other forms of student public participation. One revolves mainly around welfare, administrative, and campus-specific issues (Hazary Reference Hazary1987, Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey, Price and Ruud2010a). Such politics, led by brokers and local political entrepreneurs, is often motivated by prospects of personal gains (Jeffrey and Young Reference Jeffrey and Young2012, Reference Jeffrey and Young2014). While it tends to be more violent (Oommen Reference Oommen1974, Ullekh Reference Ullekh2018), it reproduces existing social hierarchies, whether woven around caste, class (Jeffrey Reference Jeffrey2010b, Kumar Reference Kumar2014), or gender (Lukose Reference Lukose2009). While different in nature, ideological and non-ideological student activism both have solid ties with off-campus party politics; universities therefore often serve as pools for the recruitment of cadres as well as springboards for aspiring netas (leaders) (Hazary Reference Hazary1987, Baruah Reference Baruah2013).

The third type of Indian student politics, somewhat paradoxically, relies on an anti-political discourse. Following the trail of privatization of higher education, such politics of anti-politics demands the ban of protests in the public space (Lukose Reference Lukose2009) and labels organized politics only in terms of corruption (Sitapati Reference Sitapati2011, Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2012), unruliness, and time-wasting. Congruent with the disciplining public discourse on political activities in educational institutions (Lyngdoh Reference Lyngdoh2006, Teltumbde Reference Teltumbde and Bhattacharya2019), such attitudes are developed mainly by upper middle-class cohorts (Jaffrelot and Van der Veer Reference Jaffrelot and Van der Veer2008, Kumar Reference Kumar2017) across study disciplines, with particular acuteness among STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) students (Fernandez Reference Fernandez2018). Averse and acrimonious understandings of contentious politics put substantial emphasis on civic order, safety, and consumption rather than on dissent, justice, and redistribution. They also replace notions of social justice such as inclusiveness with those of individual merit (Subramanian Reference Subramanian2015, Henry and Ferry Reference Henry and Ferry2017).

The establishment of JNU in 1969 as a flagship postgraduate university in the social sciences first reflected the ambitions of the socialist left at the centre, structured around an alliance between the Communist Party of India (CPI) and the Indian National Congress (INC) (Batabyal Reference Batabyal2015). In 1971, a generation of upper-class students created and strengthened a Students’ Union (Pattnaik Reference Pattnaik1982). The Union, which was intended to be an instrument of politicizing the campus, was deeply influenced by Marxist thought, and it took direct part in the affairs of the university from the very beginning. After the state of emergency declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (1975–1977), the Union reflected more clearly the regional domination of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) in West Bengal and Kerala (1977–2004) (JNUSU office bearers 2004). Finally, in the last 15 years, it has been promoting the student wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI(ML)), a formerly anti-parliamentary Bihari-centric organization that converted to electoral democracy in the early 1990s (Jaoul Reference Jaoul, Gayer and Jaffrelot2008). Today, a non-negligible section of the younger generation of CPI(ML) office bearers are JNU graduates. Post-2016, state-sponsored and coordinated attacks on anti-government student activism in the country have triggered alliances between various oppositional student groups, causing a united front of left political outfits to emerge on the JNU campus (Martelli Reference Martelli2020).

Biographical accounts of former activists and professors (Souvenirs 2008–2010) are vivid testimonies to the leftist ethos of the university, as exemplified during the major protests that followed the arrest of Kanhaiya Kumar, the left (that is, member of the CPI) president of the Students’ Union on 12 February 2016, on charges of sedition (Scroll.in 2016). The reaction to this, and the arrest of two Maoist sympathizer activists over alleged anti-India speeches, was followed by daily meetings in the administration bloc, renamed ‘Freedom Square’ for the occasion (Youth Ki Awaaz 2016).

As with the Jawaharlal Nehru University Teachers Association (JNUTA), student organizations affiliated with leading left parties have dominated JNU student politics and won most of the Students' Union elections on campus. As exemplified by Figure 1 below, since its creation an overwhelming majority (85 per cent) of JNU Students' Union (JNUSU) elected representatives have been members of a Marxist student group: 81 of them were part of the Students’ Federation of India (SFI), the student wing of CPI(M); 34 from the All India Students’ Association (AISA), the student mass organization of CPI(ML); and 19 from the All India Students’ Federation (AISF), the student body of CPI. I focus mainly on the activists in these three student organizations along with two smaller ones: the Democratic Students’ Union (DSU),Footnote 6 supporter of the Communist Party of India Maoist (CPI(Maoist)), and the Democratic Students’ Federation (DSF), a splinter group of the SFI.

Figure 1. Weighted map of political affiliations of JNU Students’ Union representatives (1971–2017). Source: Author's fieldwork.Footnote 7

(1) Marxist student organizations

SFI: Students’ Federation of India, student wing of the Communist Party of India Marxist (CPI(M)).

AISA: All India Students Association, student wing of the Communist Party of India Marxist-Leninist (CPI(ML)).

AISF: All India Students Federation, student wing of the Communist Party of India (CPI).

DSF: Democratic Students’ Federation, splinter group of the SFI, associated with the Left Collective in West Bengal.

Rev. SFI: Revolutionary SFI is another splinter group of the SFI.

DSU: Democratic Students’ Union, supporter of the Communist Party of India Maoist (CPI(Maoist)). It usually does not contest JNU student elections.

(2) Other left student organizations

FT: Free Thinkers, a defunct non-affiliated socialist platform inspired by the ideas of Jayaprakash Narayan.

Ind.: Independent candidates with no official political affiliation.

STY: Solidarity, a defunct non-affiliated socialist platform named in the wake of the Solidarność movement in Poland.

SYS: Samata Yuvajan Sabha (Equal Youth Assembly), the youth wing of the defunct Samyukta Socialist Party (United Socialist Party).

(3) Non-left student organizations

NSUI: National Students’ Union of India, student wing of the Indian National Congress.

ABVP: Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (All Indian Student Council), student wing of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteer Corps, RSS). Strongly supports the current Hindu nationalist party in power, the Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People's Party, BJP).

UDSF: United Dalit Students’ Forum, sympathizer of the Bahujan Samaj Party (Majority People's Party, BSP). It does not contest JNU student elections.

BAPSA: The Birsa Ambedkar Phule Students Association is a splinter group of the UDSF. Unlike the latter, it has contested elections since 2016.

While activists are a minority among JNU students, their numbers are not negligible. Among the 1,224 students I surveyed in 2014–2015 as part of my doctoral thesis (see also Martelli and Ari Reference Martelli and Ari2018, Martelli and Parkar Reference Martelli and Parkar2018), 33 per cent declared that they participated at least once a month in political activities and 23.1 per cent were members of a student organization on campus. Among those disclosing their political affiliation, 71.3 per cent were part of a Marxist student organization.

While the overwhelmingly leftist section of politically active students at JNU reflects, to a certain extent, the socioeconomic diversity found on campus, such groups have the tendency to over-represent middle-class profiles rather than upper-class ones (Martelli and Ari Reference Martelli and Ari2018). I point out the middle classness of JNU activists by showing their tendency to display a comparatively lower socio-economic status (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2006, Mishra and Parmar Reference Mishra and Parmar2017) when compared to the average JNU student. At a general level, the entrance policy of JNU—which implements affirmative action mechanisms—ensures higher levels of socio-economic diversity than other institutions in the country (Martelli and Parkar Reference Martelli and Parkar2018). As per the JNU Annual report 2014–15, 44.3 per cent of JNU students did not benefit from any government reservation scheme.

Among activists, more male participants and a higher proportion of non-elite profiles can be found, proxied by the background information of parents such as income, profession, education, and place of residence (Martelli and Ari Reference Martelli and Ari2018). As indicated in the survey, on average a higher proportion of political activists and political participants received their previous education in a language other than English when compared to non-activist cohorts, indicating humbler educational backgrounds—but not necessarily deprived ones. Amid its inclusiveness, student politics at JNU attracts middle castes in higher proportions (many of whom are from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar) who have pursued secondary education away from the main Indian metros (see Appendix). This highlights the dissonance between the middle-class upbringing of activists and the deprived backgrounds of those at the centre of leftist discourses. I turn now to the analysis of how such dissonance is addressed by Marxist activists through the practice of self-fashioning.

Squandering the heritage through declassing and the production of representative claims

When you live with humble people, you have to live like them.

(Berhampuri, interview 2014)

Some evidence of JNU activists’ self-fashioning does exist in the gender studies literature and constitutes a good analytical departure point. Barkaia (Reference Barkaia2014), for instance, indicates in her doctoral dissertation that several left female activists attempted to transcend their gendered experience by veering away from what they considered ‘bourgeois morality’ (Shivani, cited in ibid.: 108). She gives the example of Vanessa, a pro-Maoist activist who decided not to keep her hair very short in order to disassociate herself from the ‘urban elite’ (ibid.: 100). Similarly, Shipurkar (Reference Shipurkar2016) confirms that politically active women on campus do ‘look different’, for example, they wear kurtas (loose collarless shirts). Desquesnes (Reference Desquesnes2009: 79) provides additional evidence of this, mentioning the guilt of several female activists such as Isha, who tries to renounce ‘western practices’, such as wearing eyeliner (kajal), but finds it difficult to do so, and using predominantly English in her daily vocabulary. In line with these accounts, I found that activists’ fashion sense contrasted with the ‘average’ JNU student outfit.

Declassing vs asserting dress code: apologia and critique of left self-fashioning

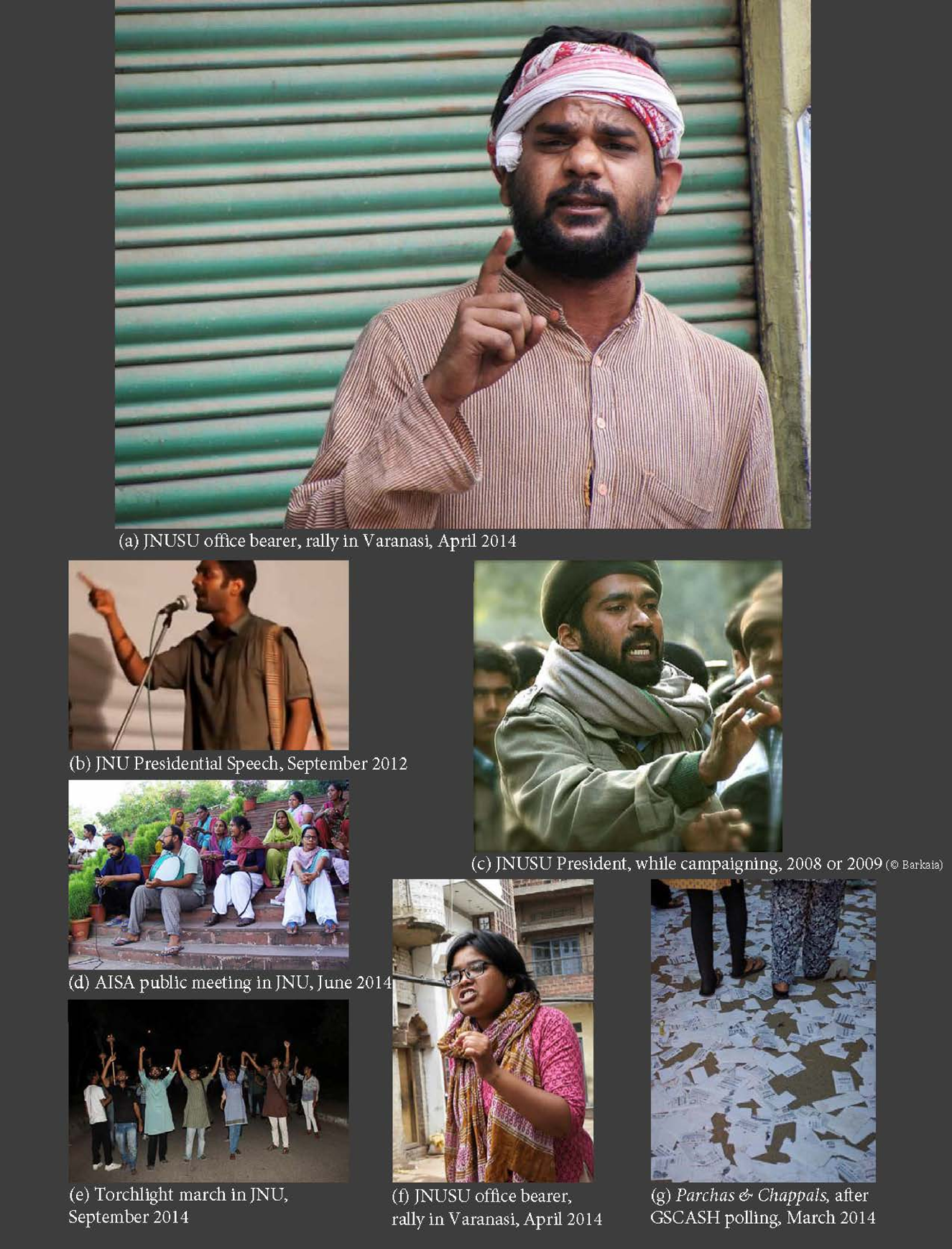

Once on the JNU campus, the aesthetic array of the left leader is highly identifiable. It comprises an unshaved beard for men, an unwashed, old, drab-coloured kurta, chappals (flip-flops) even in winter, gamcha (thin cotton towel to protect from the sun) in summer, and a jhola (jute shoulder bag) (see Figure 2). When attending rallies with activists, Drumi, a JNU PhD student used to speak sarcastically about their fashion sense: ‘It makes students think that activists are going to work with the masses by bus just after their speech … just as if they were always in movement, busy, so that they have to keep their things always with them.’

Figure 2. Contact print of different speeches by JNU activists. Source: Photos by author and K. Parkar, 2014.Footnote 8

The situated political significance of such activist chic becomes clearer when interrogating activists about the panoply of meaning they attach to the notion of ‘declassing’, which they often referred to as voluntary trajectories of social downlift. Sundar, a former JNU Students’ Union president (2012–13), was unequivocal about what to ascribe to this phenomenon: ‘Is being declassed a relevant question? Obviously yes, the problem of party leadership is that they have lost ground; lost touch with people … declassing is a very important thing, to communicate with people you need to be humble. My father is a factory worker … I do not need to declass that much, but in a sense we are all middle-class’ (Sundar, interview 2014). The following vignette, citing several statements about declassing, shows the pervasiveness of declassing idioms among the left at JNU, while being understood both as a fight against the economic elite and a challenge to the dominant elite.

-

[1] Leaders also have to fight against their own origin. The most difficult is to fight against yourself (Dipen, interview 2014).

-

[2] Without declassing you cannot reach the masses. You get corrupt if you have something to lose or to gain; if you have ambition. But I had only one ambition, the one of setting up and strengthening SFI and DYSF [youth wing of CPI(M)] … Declass is the way you should show the path … be exemplary. The personal is very important. You have to be exemplary and throw yourself into struggles (Akhil, interview 2014).

-

[3] We are all [he points at another comrade, Chandauli] middle-class and we need to declass, we have to follow the model of Chandrasekhar [a martyr]. But to declass is very tough because you have to relate with the working class (Barthi and Chandauli, interview 2014).

-

[4] Consumerist culture has penetrated the campus … and declassing, this is utopian, has to go with deculturing yourself … decolonizing the mind. It does not make any sense to raise expensive coffee and continue the fight. We come from a feudal society, we carry our past and have to break from it … there is always a mind to mimic someone upper than you … you can be lower caste and being casteist … you can be subaltern and aspire for power. The right thing is the aspiration to be humane (Tausiq, interview 2014).

-

[5] DSU comrades are deliberately not claiming scholarships, is this part of the declassing process? (Karim, interview 2014).

The centrality of the ‘declassing’ practice among the left on campus was recounted to me by Jitendra, a former activist for ‘Backward Classes’ at JNU (Anjaiah and Kumar Reference Anjaiah and Kumar2011), who had lost faith in the ability of current Indian left politicians to root out their ‘Brahmanical identity’. According to Jitendra, Puchalapalli Sundarayya (born Sundararami Reddy, 1913–85), one of the founder members of the CPI(M) in the state of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana, was the exception that proved the rule, as ‘he renounced his Reddy [upper caste] name, gave up his 5,000 acres [circa 20 square kilometres] of land and decided to castrate himself in order not to have Brahman descent’.

Another critical insight was provided by a senior professor at JNU who claimed that Marxism in India had incorporated the Gandhian visual of self-denial. ‘Well, Marxists are in a way sadhus [religious ascetics] in secular uniforms,’ he stated. This line of argument about the sacrificial leanings of the declassing practice was later substantiated when I encountered Pratap, a former All India Students’ Association campus leader. Pratap was elected in 2007 as president of the Students’ Union and has a deep knowledge of the kinds of frugality that total activist engagement entails.

Youth from middle-class background … urban class … when they start to associate themselves with the poor of the poor, you feel this connection, this need to declass. I used to have this kind of feeling, that I cannot eat costly food. No-one tells you that directly, it is a very unsaid thing. Actually it is a very unconscious dominance of Gandhi. He gave a particular image of politicians you know. It's culturally loaded. Moral guilt is there … It stays in your mind, where do you belong? To declass … sometimes this theoretical question has been taken at a superficial level. We wear unwashed kurta pyjama and dirty jeans, uncombed hairs, smoking cigarette … this framework of the revolutionary … Gandhi was the one who introduced peasantry in the freedom movement. Before it was elite, ruling-class … Gandhi introduced mass movement with this idea that he is a fakir, that he owns nothing and wants nothing … that image of him fighting for us. Particularly for the left … this idea of sacrificing everything got in their mind. If you are involved in a movement, automatically the movement gives you a form of living … but suppose he [the activist] is not part of the deprived … suppose he is middle-class … In Indian left movement, they are a lot of mass leaders who technically belong to the rich, to the upper crust. But the force, the energy of the movement you are part of … actually it inculcates to you a specific form of lifestyle. Because you are too much into it. You are an agrarian leader, you are not living like a contractor with car, you have to be there with the people. So declass is very necessary (Pratap, interview 2014).

His account is revealing in two respects. First, it confirms that declassing can be understood as a form of disidentification in which left activists try to divorce their middle-cum-higher-class selves. Second, it argues that the sacrificial modality of left self-fashioning resonates with the broader cultural repertoire of asceticism in India. Pratap's mention of the fakir (Muslim ascetic) also directs attention to Gandhi's austere discipline of non-attachment to material possessions and brahmachariya, understood as self-discipline, chastity, and sacrifice (Devji Reference Devji2010, Chakrabarty and Majumdar Reference Chakrabarty and Majumdar2010, Mehta Reference Mehta2010). I do not wish to claim that Gandhi directly inspires the ‘political technology’ of Marxist declassing. However, in line with Pratap, I want to suggest that Gandhi popularized the idea that intimate practices, especially body practices, expressed sincere alliance with the masses. Gandhi welded together ascetic language and popular politics. This connection was soon reinterpreted by Indian Marxist practitioners, while attracting sharp critique from sections of oppressed communities.

Keeping in mind the fact that declassing is a dominant modality of JNU campus politics, such practice sparks more ambiguous feelings among activists from Muslim and Dalit backgrounds. Because these politicized students fight against the common perception that they rank low in the social ladder, the idea of declassing was seen by them as a reinforcement of their already downgraded social status. In such cases, declassing discourses were complemented—and at times replaced—by assertive claims. Below are examples of how uneasy the compromise is between the politics of recognition and the politics of declassing.

-

[1] I am not supposed to go down, I am supposed to go up. Because of my unprivileged background [Muslim from a rural area of West Bengal] I find all this idea to declass ridiculous, though it was not the case when I was active in DSU … you have to take my activist commitment in an historical perspective, I wore jhole [jute bags] because I was imitating my peers, I was emulating. Now that I have stepped out I wear the jhole on particular occasions, at least I am aware of its symbol. You know, I still have 20 kurtas in my room, I have them but I don't wear them (Karim, interview 2014).

-

[2] This was in 2007. That Dalit fellow went on stage for his speech with an impeccable shirt, the Ambedkarite [Ambedkar is a Dalit figure] jacket and glasses. He tried to look smart. Still ABVP [a Hindu nationalist student organization] goons tried to destabilize him, use abuse words like ‘chocolate’ [in reference to his skin colour] (Lino, interview 2014).

-

[3] Class struggle is my class interest … my father is handicapped and we have only three acres of land. I would say I am lower-middle-class so I do not need to declass … rather I need to improve my standard of living. But I also need to decaste, you can see these things in the way you are eating … it is a difficult process because it's subconscious. Then I can become a shaheed [a martyr], where you eliminate yourself, eliminate your values (Venu, interview 2014).

For many activists from deprived sections of the population, to transform one's identification to a humbler social background would appear to contradict their aspirations, so the idea of squandering one's heritage was, in part, a narrative that was difficult to defend. In such cases, through discarding declassing practices, for some left activism became a way to affirm one's marginalized identity and avenge perceived forms of degradation. For example, Sumbul, a female candidate from AISF in the 2014 student elections, would claim on stage to be part of the pasmanda (most marginalized) section of the Muslim community before shouting, ‘Long live revolution … long live social justice’. Alongside declassing claims, assertive leftist claims often involved more personal experiences; for instance, a former JNUSU president would discreetly ascribe part of his activism to a reaction against an experience of perceived humiliation. An activist from the Backward Class category recalls being stopped by a supervisor at an entrance examination for an Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) because he could not afford a proper shirt (Venu, interview 2014).

Bearing in mind the emancipatory motto of the Dalit reformist Ambedkar (1891–1956), lower caste activists I encountered did claim that political assertiveness implied breaking the association between poverty and the stigma of inherited caste pollution, and for this reason some rejected the idea of declassing altogether. For instance, Hilsari, a Dalit involved in the CPI(M)-affiliated student organization SFI, was very clear about the inappropriateness of declassing:

After my MPhil submission I will have to work and send back some money home. I cannot afford to declass; I need to look assertive. Malls and Café Coffee Days [a popular coffee chain] are around you, why should you avoid them? See, when you want to look poor is that you are actually from a privileged background. I think it is quite irresponsible, I cannot afford that. Look at Ambedkar, he tried to dress up smartly, assert his own [Dalit identity] while people wanted him to remain dirty (Hilsari, interview 2015).

This statement underlines the contingent and situated nature of the concept of declassing for left activists: its relevance depends on the social origin of its upholders. Assertiveness instead of declassing is, in the words of many Dalits, a choice rooted into their personal experiences of social humiliation. I was troubled by the large number of examples provided by respondents. Tulsi, an office bearer of the United Dalit Students’ Forum (UDSF), a Dalit cultural organization, mentioned to me an event at which his professor had prevented him—but not his other classmates—from entering his home after he was asked to pick garden flowers.

Another instance of such humiliation was given by Patani, a member of the Birsa Ambedkar Phule Students Association (BAPSA), a Dalit political group. He told me the story of a conflict with his roommate who tried to avoid caste-based pollution by refusing to drink water from the same glass as him. Gradually emerging as the main anti-left platform on campus in 2016, the newly formed BAPSA challenged the assertion that the left was the most legitimate to represent the cause of the oppressed. Labelling left politics on campus as a ‘gallery space to patronize Dalits’ (Tulsi, interview 2015), BAPSA and UDSF challenged declassing politics by invoking an assertive ‘Ambedkarite politics’ (Kumar Reference Kumar2018, Pallikonda Reference Pallikonda2018).

The acceptability of the ‘left declassing’ discourse by the student population varies. With a few notable exceptions,Footnote 9 I encountered only a few JNU students who were completely alien to campus politics dominated by the left. While almost half of freshers declare that they do not participate in political activities, this number falls to under 10 per cent after completing five years of study (Martelli and Ari Reference Martelli and Ari2018, Martelli and Parkar Reference Martelli and Parkar2018). The normalization of left political language and its declassing tropes is visible on the night of the JNU Students’ Union election vote counting. Traditional left naras (slogans) are chanted but also parodied, and the ways of the activists are affectionately mocked. Laughter is not only there to express anti-left sentiments, but for one night to deride the seriousness of the dominant ideologies of JNU student politics. The content of the jokes shouted is not anecdotal, for it reveals how rooted the leftist political culture is at JNU. The jokes do not point primarily at a sexual or religious imaginary, they concentrate on the political folklore of the campus and the declassing culture it entails. For instance, two of the parodical tongue-in-cheek slogans take on the self-negligence of left activists by rephrasing two of their slogans: Nahi nahane wale ko ek dhakka aur do (Those who don't take bath, push them once more) and Lifebuoy bhi lal hai (Lifebuoy [India's best-selling red-coloured brand of soap] is also red), uttered after Pura campus lal hai (All campus is red).

To conclude, the Dalit and Muslim discourses on self-fashioning can be very different from those developed by other politically dominant sections among Marxist activists. The accounts presented above are a reminder that declassed meaning-making varies greatly according to one's social background and lived experience. Yet, precisely because it is contested, this form of self-fashioning shows its relevance in contemporary left student politics. It exemplifies how the left uses biographical reconfiguration—whether at substantive or superficial levels—to legitimize the claim that it represents the cause of the Indian underbelly. To map out further such representative claims, the next section delves into the additional everyday practices at the core of left self-fashioning.

The routinization of left self-fashioning: the day-to-day legitimation of representative claims

The decades-long dominance of left politics at JNU is an indication of the political legitimacy activists derive though mobilizing the declassed representative claim. As for many social phenomena, the activists' devotion to this political modality cannot be credible unless the practice of declassing is carried out repeatedly and over an extended period of time. Considering the centrality of day-to-day in situ socialization in the circulation of political attitudes at JNU (Martelli and Ari Reference Martelli and Ari2018, Martelli Reference Martelli2020), the efficacy of left self-fashioning relies on its everyday routinization in a shared living space where such practices are made visible. Thus, below I survey various ways in which declassing practices are made pervasive and are inherent to JNU campus politics. These routinized practices, introduced below, are: space segregation, martyr identification, anger emotionality, and fasting.

Nested within the competitive field of campus activism, these processes of individual fashioning accompany the daily trail of political activities organized on campus. While activists’ collective actions often focus on the general welfare of students and on admission inclusiveness, on other occasions they engage more widely with the socio-economic conditions of India's weaker sections of society, thus making the declassing claims congruent with political actions taken on campus. Thus, engaging and expressing ‘solidarity’ with the issues concerning the deprived inform and legitimize declassing claims.

Such instances are many. They include: calls by left student organizations for a demonstration in support of the workers of the automobile manufacturer Maruti Suzuki; after launching strikes in 2012, which led to the burning-to-death of a manager in Manesar (Haryana), 147 of them were jailed (Nowak Reference Nowak2014). Other cases comprise protests against communal riots that took place in Muzaffarnagar (a district of Uttar Pradesh) in 2013, which led to the displacement of tens of thousands of individuals and to the deaths of 42 Muslims and 20 Hindus (Berenschot Reference Berenschot2014). The Students’ Union sent a ‘fact-finding’ team to collect evidence and to provide assistance to the victims. Additional initiatives include commemoration of the anniversary of the gang rape of Nirbhaya (‘fearless one’), a pseudonym given to the physiotherapy intern who was attacked on a bus in Delhi on 16 December 2012. Support is systematically ‘extended’ after the suicides of members of weaker sections of Indian society, such as Dalits and farmers. For illustrative purposes, below are four JNU pamphlets by four different left student organizations, vividly protesting in support of Dalits, Kashmiris, and poor famers (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Four JNU pamphlets, 2012–2018. Source: Compilation by author.

Top left-corner: SFI congratulating the Kisan (farmer) long march, a large-scale protest organized by a sister organization in the state of Maharashtra (11 March 2018).

Top-right corner: AISA commemorating the denial of justice surrounding the 1996 case of the killing of 21 Dalit labourers in Bathani Tola in Bhojpur, Bihar, by Hindu militia, the Ranvir Sena (14 July 2012).

Bottom-left corner: DSU calling for a protest after the suspension of Kashmiri students who cheered for Pakistan in a cricket match (7 March 2014).

Bottom-right corner: BASO (splinter group of the DSU) protest call against anti-Dalit violence on the commemorative ground of the battle of Bhima Koregaon, Maharashtra (2 January 2018).

While the practice of declassing is tied to participation in political activities in support of the downtrodden, the moral injunctions it entails include refraining from visiting certain places. As indicated in the preceding account of Hilsari, this practice suggests that, along with the focus on visuality, left self-fashioning also involves strong spatial components. During my time on campus, I found that many left activists tended to circumvent commercialized areas and those that are perceived as ‘dirty’ living spaces. JNU Marxists tended to avoid being seen or visiting places where the ownership of costly objects such as a smartphone or a motorbike ‘have to be reflected upon’ (Berhampuri, interview 2014), thus boycotting the settings of ‘shining India’: malls, food chains, and branded coffee shops associated with the triumphant consumerism of the Indian middle class.

As a result, the spatial politics of activists leads to the superimposition of an ideological layer onto the actual map of the city, causing them to redraw territorial hierarchies. Contrary to commercialized areas, select food-stalls (dhabas) within the campus are seen as more compatible with a declassed way of life. One in particular, called Ganga Dhaba, was perceived by Pratap (interview 2015) as a refuge from the areas polluted by consumerism, an opinion he also expressed in an interview with The Indian Express:

With its thorny babools [acacia trees], rocks for chairs and tables, and deep pits and mounds, Ganga dhaba is a critique of today's glittering commercialized times … It is a symbol of free thought and open exchange of ideas, with its uncontrolled space where any number of people can huddle anyhow around any stone. Here, students have planned revolution as well as found romance. But now, it is not the locus of life on the campus that it used to be. If you walk a little ahead, you will find another eatery, the 24/7 dhaba, which seems to be what the Ganga dhaba is a critique of. Here, you will find tables and chairs, a well-ordered space, a bigger menu and fewer people in JNU chic—jeans and kurta. Ganga dhaba and the 24/7 dhaba spatialise the slow shift from Marx to market which has become visible on the campus (Pratap in Kumar Reference Kumar2013).

In contrast, malls and food chains were the least reputable spaces to be seen by left activists concerned about their political and public reputation. I vividly recall a revealing anecdote that manifested the taboo attached to glittering spaces. The 2015 April heat in Delhi was at its peak and I had promised Arpita, an active member of AISF, to treat her to a pizza as she had craved one during her most recent 10-day-long hunger strike. One evening, I finally convinced her and her comrade-friend Azad to go to a restaurant chain in the fashionable market next to campus. They claimed they had never been there before and accordingly much discussion focused on what they saw from the dining table. They concentrated their indignant comments on overweight customers and on waiters who expressed condescension towards customers ordering too little. As we were finishing our meal, the unexpected happened: three activists from a rival Marxist organization entered Pizza Hut to eat. After a fleeting moment of astonishment and awkward salutations, Hariti, Jitendra, and Priya disappeared from sight and went to eat on the lower floor. Making sure he could not be heard, Azad started laughing, ‘You know what they call me?’ he asked, but before I could respond he was already answering, ‘A revisionist. They are supposed to be real revolutionaries, radical ones. But what I find crazy is that their personal life goes against the principles they claim in public. Their private life is going against their political principles.’

The meeting of five Marxist leaders from two rival organizations at Pizza Hut was a truly incongruous moment: they were witness to each other's political sacrilege at odds with their understanding of the declassing code of conducts. Aside from the comical overtone of the example, it underlines how important the notion of exemplarity—real or claimed—is to the conduct of left politics. As shown here, the political legitimacy of self-fashioning is inseparable from this notion of exemplarity, whether applied directly to the self or when projected onto the commendable life of deceased martyrs.

Focusing on activists’ invocation of shaheeds, I now discuss their instrumental role in providing historical depth to the declassing practice. I suggest that the personification an ideal type of a declassed figure is the consecrated martyr, which facilitates activists’ personal identification with a political movement and the public display of their intimate appropriation of pro-people rationales. Because martyrs are admirable and irreproachable beings, they can—in the case of Indian communism—be ‘good to think with’ as symbols of declassed individuals who commit to their cause until death and enable comrades to show the masses the way forward.

On campus, several public celebrations of martyrs are organized annually. Organizations such as DSU and SFI organize memorial lectures in remembrance of the killing of several iconic party workers (Third Comrade Naveen Babu lecture 2014; SFI Central Executive Committee 2016). AISA also holds an annual celebration of the martyrdom of ‘Chandu’, alias Comrade Chandrashekhar (JNUSU president 1994–1996), and screens a homage documentary called Ek Minute Ka Maun (A Minute of Silence) on a JNU lawn (Basu and De Reference Basu and De2007?). Every last week of March, during the commemoration of his assassination,Footnote 10 Chandrashekhar is presented as a declassed communist who sacrificed his life for the fight against injustice and caste oppression in India. An AISA activist recounts that Chandu ‘led many agitations, he would interest anybody with his speeches … and Chandu could interest through his practice … of his life … declassed life in fact. … He didn't pay attention to what he is wearing … he never minded’ (Akbar, interview 2014). By rival organizations’ own admission, AISA—through constantly reclaiming Chandu's legacy—manages to appear to new students as a sincere, committed, and radical student organization on campus (Gowda, interview 2015).

When it comes to achieving political mobilization, the invocation of Chandrashekhar's sacrificial self is by no means insignificant. Chandu is not only an inspiring figure for activists, but also a political totem instrumental to galvanizing, recruiting, and persuading ordinary students to join protests and participate in political activities. As displayed in the quotes from six AISA pamphlets (see Figure 4), Chandu's martyrdom captures the universe of social suffering that prevails outside of the microcosm of campus. Consequently, his sacrifice enables students to enlarge their political imaginary and locate current student politics within the larger historical framework of anti-class and anti-caste struggles.

Figure 4. Six concordances of words associated with Martyr Chandrashekhar in JNU pamphlets. Source: Compiled by author.Footnote 11

While the political significance of commemorating martyrs is not entirely encapsulated in the social phenomenon of self-fashioning, the credibility of left activists depends in part on their ability to harness an ideal version of declassing—the one imagined and embodied in the sacrificial lives of left martyrs—in their daily politics. The political ecology of left martyrology is important in building a legitimacy based on sincerity and emotional resonance (Traïni and Terry Reference Traïni and Terry2010), which in turn play an important role in the emergence and decline of student movements.

While not specific to Marxist activism, I envision anger against perceived injustice as a contributing factor to the declassing practices described above, as it entails the practice of emotional association with the suffering classes and castes. In outlining the inequality between the rich and the poor, and the consumerist heartlessness of the ‘bourgeois middle class’, activists regularly find ways to trigger affect, in particular emotions associated with social conflict over land, labour, love, or dignity.

In order to locate such embodied emotionality, I will now refer to the distinctive visual culture of JNU student politics, in particular its poster culture. Every year in summer,Footnote 12 each student organization mobilizes local artists in their ranks to draw posters several metres long and paste them on the campus's administrative and academic buildings. The result of this process is a saturation of political messages everywhere students look. Most of the 392 posters pasted on campus walls in 2014 were pictorial representations of the social oppression of workers, peasants, and so on. Three poster-making campaigns later, when questioned about the relevance of the display of raped women and massacred Dalits in his posters, Souradeep, an AISA male artist-cum-activist declared that:

… even though a woman is not part of my country, even though she is not my mother, my partner, or my sister … even though we don't know the actual experience of pain they face, all [these women] are in my landscape. How can you ignore? If you are engaged with the people, you can't ignore, even if you are an upper class. You have to take part in Dalits’ movements, because it's part of your landscape. We have to liberate each and every one. We are part of the same structure we call society. We are all, in a way, secondary order witnesses. So my posters and paintings, are spaces of morbidity … there are no other options, it's about the representation of politics … on the one hand, it is about criticizing society, and on the other, it is about criticizing yourself as well (Souradeep, interview 2017).

The ability to feel the suffering of the oppressed women and Dalits who surround him is crucial to Souradeep, who consequently uses this expressed emotion to ‘criticize himself’ as an elite member of Indian society. Later in the interview, he associates this privilege with his Hindu identity, which contrasts with the marginalized condition of Muslims in contemporary India. In his posters, self-reflexivity is mediated through the depiction of morbid subjects such as women aborting, agonized animals, half-starved farmers, or a couple of murdered valentines massacred by Hindu vigilantes for being engaged in inter-faith love.

The embedded aesthetic of pain on JNU posters is exemplified by the four-metre acrylic poster inspired by Picasso's 1937 Guernica and a 1947 sketch by modernist artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915–1978) (see Figure 5). It was painted by Souradeep with the assistance of another student and pasted on a wall in front of an academic building. It displays a similar morbid aesthetic to his more recent 10-metre panoramic ink-on-canvas composition (see Figure 5) displayed as a scroll and commissioned for the ‘Memories of Change’ exhibition on student politics (Martelli Reference Martelli2019). The title ‘When nothing works then serious shit happens’ is inspired by a slogan against a 2013 bill regulating land evictions; it reflects on the violence endured by farmers when the state acquires their means of subsistence.

Figure 5. Two panoramic compositions by student activist artist Souradeep [anonymized], (2014, 2019). Source: Photos by the author.

Many elements representing class oppression can be found in the JNU poster. The dominance of the rich is symbolized by the enormous steamroller/tank. It is mounted by capitalists holding a newspaper with the headline ‘Towards a richer life’. Different categories of oppressed individuals are crushed under the weight of the oppressor class. The man holding the ear of wheat is the Indian peasant and the slender but muscled bodies lying on the floor represent workers’ corpses, contrasting with the fat capitalist. The grievances of the peasant-worker class are written on the sign held by a woman: ‘Fair wages, food, health, education’. The blue colour of the smashed individuals is an indication of their low caste identity. In India, symbols and colours have an acute political meaning, and blue connotes Dalit identity (Jaoul Reference Jaoul2006, Reference Jaoul2016). The ideological interpretation of the picture is provided in the corners of the poster though a verse from the poem ‘Dark Times’ (1937) by the dramatist Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956): ‘When the great powers joined forces against workers … why were the poets silent?’ The sense of this in the context of India is: ‘If Indian society is so unfair and violent, why are you not doing anything about it?’

As indicated by Souradeep, felt emotionality enables the artist to go beyond his privileged experience and join in the suffering of the toiling masses in order to represent them. By unfolding an aesthetic that encapsulates indictment and pleas, Souradeep's pamphleteer and graphic discourses use pathos to denounce, accuse, and incriminate the ‘bad people’ identified with India's crony capitalists, the zamindars (big landowners), imperial forces (the United States), neo-colonizers (Israel), and the corrupt Indian state.

Similarly, a pro-Maoist senior supporter will never miss an opportunity to recall the state of affairs in the country: ‘Don't you see the unbearable exploitation of the masses … see among them there is despair; people have the choice between dying alone or dying fighting’ (Sharad, interview 2015). Through calling upon mimetic grief, the activist allegorically becomes the deprived: he is therefore capable of political empathy. Declassing—the sincere attempt to side with those suffering—is a practice that enables activists to unleash a universe of negative feelings that command indignation and call for action. Such rallying cries are part of a rich set of means that activists have at their disposal to make political claims. Within such a repertoire of contention, one practice strikes me as particularly relevant to the study of left biographical reconfiguration: fasting.

Activists’ self-fashioning on campus is anchored to a daily political routine which involves organizing and participating in many public events.Footnote 13 One particular way of protesting—the hunger strike—engages with self-centred corporeal practices in support of the cause of needy students. I describe such practices as important for inserting the question of self-sacrifice into the realm of less political issues that affect students involving mostly infrastructural and administrative shortcomings on campus. Obviously, fasts belong to the wider ‘toolkit’ of South Asian politics (Reddy Reference Reddy2009) and many of them might have little to do with expressing empathy for the depressed classes. Within the left repertoire of contention, some JNU activists even admit favouring gheraos (blockades) over fasts (Desquesnes Reference Desquesnes2009). However, tied to a communist political agenda, fasts can become a fully fledged means of promoting one's selfless personal commitment while addressing the grievances of students, thus claiming effective representation.

Along with being an instrument to satisfy student demands and gain leverage in negotiations with the JNU administration, fasting allows activists to put pressure on decision-makers in the name of distressed people—that is, poor students without on-campus accommodation or students unable to afford living costs. Because fasts demonstrate one's commitment to student welfare, political organizations usually ask future candidates for the Students' Union elections to participate in the hunger strikes organized on campus. A former JNUSU president acknowledges the relevance of hunger strikes in the following way: