Introduction

On 14 April 1923, Molly Ellis, an English teenager, was awakened at around 2 a.m. by the sound of her mother calling out for her. In the dim light of a hurricane lamp, Molly barely made out the figures of two men struggling with her mother—one of them was holding a dagger. Molly's father, Major Archibald Ellis, was away on duty at the time. On nights when it was just the two of them, Molly and her mother Ellen slept in the same bedroom under a large mosquito net. Since arriving on India's North-West Frontier several months prior, Mrs Ellis had been afraid that something terrible might happen to her and her family in the Kohat Cantonment where they were posted. Her husband gave her a whistle to blow three times in the event of an emergency. He instructed the guard, positioned a few hundred yards away, not to approach the family's quarters unless summoned by the blast of the whistle.

In the adjacent bungalow, Captain Hyland and his wife were roused from sleep by the growling of their two dogs. As soon as he heard the guard yelling ‘daku! daku!’ (thief! thief!), Captain Hyland grabbed his pistol and rushed next door. Mrs Hyland stayed behind, nervously clutching one dog on either side of her. When he entered the Ellis's bedroom, Captain Hyland found Mrs Ellis dead, her throat cut. He grabbed the whistle and handed it to a servant, who blew it sharply three times. The guard hurried over but it was too late—the intruders had already escaped with several rugs, two animal skins, a camera, a watch, and Molly, who was 17 years old at the time.

When the news reached him, Kohat Deputy Commissioner C. E. Bruce dispatched a terse priority telegram to Sir John Maffey, the chief commissioner of the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP): ‘Regret to report Mrs. Ellis murdered about 2 a.m. and appears Miss Ellis carried off. No shots fired. Troops turned out. Will report fully later.’Footnote 1 Calls were placed to the Frontier Constabulary posts along the Kohat Pass advising them to look out for the kidnappers on all paths into semi-independent tribal territory where the Government of India had no legal jurisdiction.Footnote 2 The local Afridi and Orakzai tribes were warned that they would be held collectively culpable for the crime if they gave the group shelter or safe passage. In a longer report sent a few days later, Bruce observed:

The most horrible crime which in savagery and brutality more than vies with the foul murder of Colonel and Mrs. Foulkes in Kohat in 1920 was committed in Kohat Cantonment when poor Mrs. Ellis, the wife of Major Ellis, D.S.O., of the Border Regiment, was foully done to death and her daughter Miss Ellis, of about 18 years of age, was kidnapped and carried off (at least we must surmise this as she was found to be missing). It was at about 2:30 to 2:45 am that the Superintendent of Police sent his motor to my bungalow informing me shortly of what had occurred. I quickly slipped into some clothes and proceeded in motor to the spot.Footnote 3

The abduction of Molly Ellis was an international scandal charged with symbolic significance. From the British perspective, the intimately gendered dimension of this particular attack—a white woman killed and her daughter kidnapped from the bedroom of a colonial military bungalow—provoked heightened anger and anxiety. Contemporary English-language newspapers printed sensational accounts of the incident. A London Times headline read: ‘ANOTHER FRONTIER OUTRAGE: one lady killed and one kidnapped.’Footnote 4 The New York Times declared: ‘CAPTIVE ENGLISH GIRL IS SEEN WITH SAVAGES’,Footnote 5 above an article that described the kidnappers as ‘primitive savages—big, rawboned, devil-may-care fellows of great strength and hardihood, many of whom devote their whole existence to hunting, fighting, and brigandage’. Another New York Times article referred to the anxiety produced by recent attacks in the region, while noting that ‘[t]he abduction of Miss Ellis and the cold-blooded murder of her mother stirred Europeans in India more than many other outrage by tribesmen in recent years’.Footnote 6

Stories about the kidnapping of Molly Ellis and the murder of her mother by Ajab Khan Afridi and his three accomplices have been told in many languages, disciplines, and media for almost a century. In the colonial archive, the incident figures as an extreme example of the mortal danger presented by what British officials called ‘frontier fanaticism’ and ‘tribal turbulence’.Footnote 7 Within this narrative framework, the kidnapping was an ‘outrage’ that demonstrated the lawlessness of people and the threat they posed to the lives of Britons in the region and to the stability of the Indian empire more broadly. The episode is mentioned in most popular English-language histories and personal memoirs of British colonial-frontier life, in several historical and anthropological studies, and in a broad assortment of other accounts.Footnote 8 In May 1978, as part of director/producer Stephen Peet's ‘Yesterday's Witness’ documentary series about British social history, the BBC aired a segment entitled ‘Frontier Outrage’, featuring interviews with several eyewitnesses to the event, including Molly Ellis. After the so-called US ‘war on terror’ was launched in 2001, Ajab Khan began to make appearances in American counter-insurgency literature. David Kilcullen, former counter-insurgency adviser to General David Petraeus and Special Advisor for Counterinsurgency to then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, published a book in which he drew a link between Osama bin Laden's ‘ability to spread contagion via globalization pathways’ and the ‘long line of charismatic extremist fugitive leaders who have hidden out in remote mountain areas and waged guerilla warfare against local authorities’, including Ajab Khan.Footnote 9

The legend of Ajab Khan Afridi endures in local collective memory and cultural forms that portray him as a valiant son of the soil who courageously challenged the alien government to defend of the honour of his people. For decades, tales of Ajab's heroic defiance were told and retold in Pashto poems and ballads that were performed in village hujras (male gatherings) and sold as audio recordings in Peshawar's Khissa Khwani Bazaar.Footnote 10 Several film versions of the story were produced, beginning with Khalil Kaiser's 1961 Urdu-language hit, Ajab Khan. Punjabi- and Pashto-language versions soon followed. In 1991, the Kabul-based Khushal Cultural Society published a collection of articles in Pashto commemorating the life of Ajab Khan Afridi.Footnote 11 In 2012, Dr A. Q. Khan, a founding father of Pakistan's nuclear programme, published an admiring article about Ajab Khan and the ‘wily British’ in Pakistan's English-language daily The News.Footnote 12 The line separating verifiable facts from storied rumours about the incident has always been blurred; living relatives of several figures connected to the story wrote to Dr Khan to correct certain factual errors in his column. To this day, Ajab's memory is celebrated on blogs, Facebook posts, and online animations. In spite of the widespread and enduring popular interest in the story of Ajab Khan, the history of the kidnapping has received limited scholarly attention.

Although the kidnapping of a white girl and the murder of her mother would have horrified British colonial society anywhere in the empire, the site of this particular incident was especially significant. Colonial authorities framed India's North-West Frontier as a space of hyper-masculinity where ‘lean and keen’Footnote 13 Britons faced off against the ‘barbarism of a fine manly and courageous people’.Footnote 14 Successive generations of colonial officials insisted that no ‘signs of weakness’Footnote 15 could be shown before the region's ‘fierce and bloodthirsty’Footnote 16 people and characterized the ‘troublesome tribes’Footnote 17 as wild beasts who roamed across an archaic landscape. The racialization of the tribes justified the relentless colonial violence directed against them. As one British official ominously remarked: ‘we cannot rein wild horses with silken braids.’Footnote 18 Brutes were to be treated brutally. Civil servant Alfred Lyall coolly captured the violence embedded in colonial-frontier discourse when he observed: ‘we treated the line of savage tribes as a quickset hedge.’Footnote 19 Humans conceived of as hedges could be cut back or even pruned to the ground when they became too unruly.

This article argues that the frontier was a racialized zone of competing masculinities where challenges to state power were met with violence of various kinds. Sociologist Robb Willer theorizes that ‘men react to masculinity threats with extreme demonstrations of masculinity’.Footnote 20 According to Willer's ‘masculine overcompensation thesis’, such reactions tend to involve hyper-masculine traits and behaviours, especially violence. Willer observes that ‘masculine overcompensation’ reveals feelings of underlying insecurity held by men who attempt to ‘pass’ as being something they are not. This article draws on Willer's theory to reframe our understanding of the colonial obsession with frontier security as an example of ‘masculine overcompensation’. The need to preserve a fictive image of white, male invincibility on the frontier, to sustain the ‘“bluff” that was colonialism’Footnote 21 in the face of perceived ‘masculinity threats’, led colonial officials to ‘overdo gender’ in ways that led to extreme violence.

The abduction of Molly Ellis was interpreted by colonial officials as an assault on British honour. They worried that the failure to promptly arrest and punish Ajab Khan and his ‘Kohat gang’ would damage colonial prestige by revealing ‘the apparent powerlessness of the authorities to protect British officers and their wives even in their bungalows’.Footnote 22 In the ‘white man's world’Footnote 23 of empire, the inability to protect ‘their women’, and the inversion of power it signified, had dangerous implications. Real and imagined acts of native violence were perceived to pose a significant threat to the colonial system.Footnote 24 This was especially true on this strategically significant and contested colonial borderland where British authority was tenuous, uncertain, and constantly confronting challenges of different kinds. If Britain's manliest men could not protect ‘their women’ in the militarized space of a cantonment bedroom, what did this say about the purported strength of imperial masculinity and the invincibility of the empire it claimed to represent?

Colonial violence on the racial frontier

The annexation of the Punjab in 1849 extended Britain's Indian empire to its north-western limits. British officials viewed the North-West Frontier in military and strategic terms as key to the defence of British India and the empire more broadly.Footnote 25 ‘The frontier’—as it was generically known—was governed by the Punjab provincial government until 1901, when the Government of India created a separate North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) under its immediate charge and supervision. The NWFP comprised administered settled districts (where taxes were collected) and un-administered tribal tracts that formed a narrow, mountainous strip of territory separating British India from neighbouring Afghanistan. The settled districts in the plains were marked off from the tribal tracts in the hills by an internal administrative boundary, making ‘the frontier’Footnote 26 a zone delineated by an interior and an exterior border.Footnote 27 Colonial officials often referred to this geographical zone as Yaghistan, ‘land of the rebels’.Footnote 28 The Kohat Cantonment, where the Ellis family were posted, sat right on the edge of the administrative boundary.

The British claimed political control but no legal authority over people in the semi-independent tribal tracts. They sought to maintain a ‘buffer’Footnote 29 zone to guard British India from foreign invasion, promising the transborder tribes ‘non-interference’ in their internal affairs in exchange for their cooperation in protecting British subjects in the settled districts from transborder raids, robbery, kidnapping, and other crimes. Continuous engagement with the transborder tribes was required to manage (rather than govern) them under a system of indirect rule. Written agreements with the colonial state offered the tribes an annual allowance in exchange for the promise of ‘peaceful and friendly relations’ with the government. The majority of transborder tribes entered into such agreements in the decades following annexation. The typical agreement detailed the services demanded by the state (such as border security, control of raiders, denial of sanctuary to and surrender of criminals) and the terms of the allowance. The allowances (known as muwajib), generally paid in guns and money, were part of the coercive machinery designed to induce compliance (what was paternalistically called ‘good behaviour’) and to minimize what colonial officials euphemistically dubbed ‘tribal disturbances’.Footnote 30

If the agreements and allowances represented the conciliatory hand of British power along the frontier, the other hand presented a gloves-off approach that used force and violence to achieve colonial objectives.Footnote 31 The state's punitive machinery rested on a theory of collective, tribal responsibility according to which the tribe as a whole was held accountable for the actions of one member.Footnote 32 The idea of communal responsibility derived from the British interpretation of the principles and practices of tribal culture.Footnote 33 Working through the personal influence of its political officers and the agency of local jirgas (councils), the state took punitive action against the tribes using precolonial methods such as bandish (reverse blockades that economically pressured people into submission by cutting off access to markets, trade, and grazing land) and barampta (hostage-taking reprisals involving seizure of people, animals, and property).Footnote 34

The state also inflicted colonial methods of punishment, including punitive expeditions. A variant of the ‘small wars’Footnote 35 waged in colonial borderlands in Africa, Asia, and Australia,Footnote 36 punitive expeditions involved sudden, short, and spectacular displays of violence followed by the prompt withdrawal of troops. They were carefully choreographed to terrify and terrorize, performing the overwhelming strength of colonial power and impressing upon people the futility of resistance.Footnote 37 Frontier officials described the punitive expedition as a form of just retribution against ‘predatory barbarians’Footnote 38 who existed in ‘a state of war by nature’Footnote 39 in ‘countries which had never before known law and order’.Footnote 40 Punitive expeditions were deployed in response to a perceived crisis or ‘outrage’, such as an assault on a European or a raid on a police or military arsenal.Footnote 41 As Punjab Lieutenant Governor Fitzpatrick observed in 1901, the punitive expedition also served a pedagogical function: ‘When we first took over the Punjab, the frontier tribes had been in the habit of raiding pretty much at their good will and pleasure. They had to be taught what our strength was and one of the most effectual ways of teaching them was by punitive expeditions.’Footnote 42 In the 50 years following annexation, British officials dispatched 50 punitive expeditions in which entire villages, terraced fields, trees, crops, and livestock were destroyed by colonial troops, whether burned to the ground or ploughed with salt.Footnote 43 The imperial treasury spent another Rs 290,000,000 on punitive expeditions in the first two decades of the twentieth century before aerial bombing became the preferred method of controlling tribal populations.Footnote 44 As Philip Mason, a colonial officer-turned-historian, observed:

the tribes were still treated like tigers in a national park. They could kill what deer they liked in the park; they risked a bullet if they came outside and took the village cattle. That had been the position in 1900 and it was still a fair description in 1947.Footnote 45

Colonial knowledge about the frontier relied upon and reproduced an essentialized and static understanding of tribal society structured by a rigid, immutable cultural code and ‘barbarous and blood-thirsty customs’.Footnote 46 As a result, colonial ideas about an unchanging, primitive people acquired a timeless quality.Footnote 47 There may have been policy shifts over time but the ‘frontier problem’—framed as a problem of ‘primitive human nature’Footnote 48—remained constant. In the archive of what Nicholas Dirks calls the ‘ethnographic state’,Footnote 49 the tribesmen appear as ‘refractory savages’Footnote 50 with ‘an excitable and revengeful temperament’Footnote 51 who were ‘utterly reckless of human life’Footnote 52 and destined by religion, culture, and geography to commit acts of murderous violence and menacing ‘depredations’ of various kinds. According to a mimetic logic that weaponized colonial knowledge about Pushtun culture, ‘rude and savage’Footnote 53 men driven by codes of honour and revenge to ‘quarrel, kill and plunder’Footnote 54 had to be taught a ‘lesson of obedience’Footnote 55 in the only language they supposedly understood: the language of force.Footnote 56

Colonial violence on India's North-West Frontier reflected broader ideological shifts across the empire in the second half of the nineteenth century as the liberal civilizing mission gave way to a hardened view about populations deemed ‘too savage’ to be civilized.Footnote 57 A majority Muslim population occupied the frontier and fear of an Islamic threat played a role in shaping British attitudes in the region, particularly after 1857.Footnote 58 The discursive positioning of the tribes in anterior time was central to the argument that modern methods of discipline and punishment were ‘a garment that did not fit’.Footnote 59 A ‘population whose ethics are those of the dark ages’Footnote 60 were deemed by the colonial rulers to require special measures.Footnote 61 Thus, at around the same time as the Government of India was establishing a uniform code of laws for its modern political order in British India, it instituted a parallel system of law suitable to ‘the wants of a barbarous frontier’.Footnote 62

I first came across the case of Ajab Khan Afridi while conducting research about one of these special frontier laws: the Punjab Murderous Outrages Act of 1867 (MOA).Footnote 63 The MOA applied to ‘fanatics’ who murdered or attempted to murder ‘servants of the Queen and other persons in the frontier districts’.Footnote 64 Local authorities could summarily try and execute so-called ‘fanatics’ in unrecorded proceedings in which the accused had no right to legal representation or appeal. After conviction and execution, the body and property of the fanatic could be disposed of as the state saw fit. The most common method was to burn the corpse. Two days after Molly Ellis was abducted, the undersecretary of state for India informed members of parliament that, while vigorous measures were being taken to secure Molly's release, such ‘outrages’ could not be entirely prevented because: ‘The barren hills are the home of fanaticism and of fierce revenge. The village mullahs excite the young men with the promise of a great reward to be gained hereafter by the killing of an infidel and the youths go off in a state of frenzy seeking a victim.’Footnote 65 By rhetorically framing the incident in fanatical terms, the state had issued itself a ‘license to kill’.Footnote 66

Frontier masculinity and imperial insecurity

On the basis of rumours that the kidnappers had taken Molly to Tirah, a mountainous region in the semi-independent tribal tracts just south of the Khyber Pass (see Figure 1), Chief Commissioner Maffey assembled a search-and-rescue team. The team included his Indian personal assistant, the Assistant Political Agent in Kurram (Khan Bahadur Kuli Khan), and an English medical missionary named Lillian Starr. By sending Starr, who spoke Pashto among other languages, Maffey intended to extend a soft hand of power in lieu of a military expedition that might have threatened Molly's safety. As The Times correspondent reported from Peshawar:

The universal longing to strike a blow in retribution for this foul outrage is held in check by the recognition that rescue is the immediate and essential aim, and that nothing should be done to prejudice it. Once this has been achieved there is every reason to expect prompt punitive action.Footnote 67

Figure 1. This line map shows the route from Kohat (where Molly was kidnapped) to Khanki Bazar (where she was rescued). It was published in Lilian Starr's account above the caption, ‘Map of the Rescue Adventure’.

The involvement of a British woman in a critical mission at the hyper-masculine edge of empire is a noteworthy feature of the story that we will return to later in this article.

There were certain known facts about the ‘Kohat gang’ that were causing the prefabricated narrative of frontier fanaticism to fall apart even as it was being stitched together. A ‘murderous outrage’ supposedly involved an irrational and religiously motivated actor whose blind devotion to faith caused him to murder without provocation. However, British officials were aware that Ajab Khan was at least partly motivated by rational and strategic reasons that were connected to a ‘chain of tribal events’.Footnote 68 As such, history and politics could not be entirely leached out of the explanatory framework for understanding the incident.

The first event in this chain involved a prior attack on the Kohat Cantonment on 15 November 1920, when 44 armed tribesmen entered and ransacked the bungalow of Lieutenant Colonel T. N. Foulkes of the Indian Medical Service. In addition to stealing property worth Rs 5,000, they shot and killed Colonel Foulkes and attempted to abduct his wife.Footnote 69 When the men realized that Mrs Foulkes was mortally wounded, they released her. (Mrs Foulkes died three weeks later.) An English woman had never been murdered on the frontier before and authorities collectively held the Tirah Jowaki Afridis responsible for the crime, imposing heavy fines and a blockade on certain villages in the neighbourhood of Kohat. Nine months later, one of the suspects was arrested and executed under the provisions of the MOA. The others remained at large.Footnote 70 Collection of the Rs 12,000 fine had been scheduled for 16 April 1923 and some officials theorized that the invasion of the Ellis's bungalow was staged by Ajab Khan to ‘get the Afridis badnamed and thereby stop any settlement’.Footnote 71 (The Foulkes case was finally closed on 24 May 1923, when the Afridis paid the fine in full. A large portion of the fine was sent to the Foulkes's daughter as diyat or ‘blood money’.Footnote 72)

A second link in the ‘chain of tribal events’ involved a theft of rifles. On 14 February 1923, 46 Enfield rifles were stolen from the Kohat police lines. Thefts of rifles and other firearms from frontier cantonments were a constant problem and speak to the importance of weapons both to the colonial state and to the local people over whom it sought to exercise control. The expansion of the British empire resulted in a massive infusion of modern firearms in the region.Footnote 73 Arms made their way into the hands of local people from raids on colonial arsenals, from a Persian Gulf arms trade, and from the official practice of paying allowances in guns. A major Government of India enquiry conducted in early 1922 concluded that the arming of the transborder tribesmen had ‘left the British exposed like sheep to wolves’.Footnote 74

On 4 March 1923, Frontier Constabulary commander E. C. Handyside led a ‘counter-raid’ on Ajab Khan's village in Bosti Khel valley to recover the stolen rifles.Footnote 75 There, Handyside found 33 rifles from an underground cellar and stolen property that he claimed ‘established in the clearest manner the complicity of Ajab Khan in the murder of Col. and Mrs. Foulkes’.Footnote 76 During the ‘counter-raid’, the burqas of Ajab's female relatives were allegedly removed, violating their purdah. According to Maffey, ‘[Ajab's] mother reproached him and he swore to her on the Koran to commit such a crime as had never been committed before. The story is true and among the many factors at work is not the least important’.Footnote 77 Colonial officials reasoned that Ajab and his men had kidnapped Molly Ellis to avenge the honour of ‘their women’.Footnote 78

In the British empire, the idea of the frontier signified a racial line dividing civilization from savagery.Footnote 79 It was also a gendered construct. Literary scholars and historians of masculinity argue that a discourse of manliness developed ‘at home’ in Victorian Britain emphasizing the virtues of integrity, endurance, and hard work was enacted abroad in the empire.Footnote 80 Colonial frontiers provided a site for ‘extreme feats of masculine bravado’Footnote 81 and the performance of ‘muscular virtues’ such as courage, perseverance, and physical prowess. In his famous 1907 lecture on ‘Frontiers’, India's former Viceroy Lord Curzon described India's North-West Frontier as ‘the most important and the most delicately poised in the world’. He admiringly detailed the ‘types of manhood thrown up by Frontier life, savage, chivalrous, desperate, adventurous, alluring’, lauding the many manly qualities cultivated in Britons who served on colonial frontiers, including ‘courage and conciliation’, ‘patience and tact’, ‘initiative and self-restraint’, and ‘a powerful physique’. Curzon characterized the frontier as a ‘nursery of character’ where ‘the moral fibre of our race’ could be strengthened against the decaying influence of modern civilization and British masculinity could be reinvigorated ‘in the furnace of responsibility and on the anvil of self-reliance’.

Curzon described the frontier as a source of ‘chronic anxiety’Footnote 82 to the Government of India and waxed poetic about ‘the manly spirit and the courage of the border tribesmen’,Footnote 83 who had long evoked both fear and respect in the minds of colonial administrators.Footnote 84 Civil servant Denzil Ibbetson captured the Briton's love–hate relationship with tribal masculinity when he observed that:

The true Pathan is perhaps the most barbaric of all the races with which we are brought into contact in the Punjab …. He is bloodthirsty, cruel and vindictive in the highest degree …. For centuries he has been, on our frontier at least, subject to no man. He leads a wild, free, active life in the ruggedness of his mountains; and there is an air of masculine independence about him, which is refreshing in a country like India.Footnote 85

The figure of the ‘fine, manly and courageous’Footnote 86 frontier tribesman stood in stark contrast to the soft and ‘effeminate Bengali’ derided by colonial officials since the eighteenth century.Footnote 87 The fact that these ‘wild and lawless, but brave and manly’Footnote 88 men inhabited a strategically important frontier was a source of both consternation and comfort. On the one hand, fiercely independent and manly men do not readily submit to orders from other men. On the other hand, such men were ideally positioned to guard the region from foreign invasion: ‘India has cause indeed to be thankful that it has a race as manly and as staunch as the Pathan that holds the ramparts for her on this historically vulnerable frontier.’Footnote 89

The Kohat border was a site of continuous struggle. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed history of colonial interventions in the region, it is important to frame the kidnapping of Molly Ellis within the longer history of efforts to establish colonial dominance on the frontier and the geopolitics of the particular conjuncture of events in and around April 1923 when the kidnapping occurred. Shortly after annexation in March 1849, the Afridis signed a written agreement with the British promising to protect the Peshawar-Kohat Road in exchange for an annual allowance. When several Afridis attacked and killed members of a group of colonial surveyors dispatched to the region, the British launched the first of several punitive expeditions in February 1850. The Afridis signed a new agreement with the British after the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–80), accepting an annual allowance in return for protection of the Khyber and a promise not to engage in political relations with the Amir of Afghanistan.

The demarcation of the Durand Line in 1893 aimed to create a firm Indo-Afghan border, establishing formal spheres of influence and the expansion of railways, roads, and the movement of troops to advance colonial military and strategic interests in the transborder tracts. Efforts to control a border that arbitrarily divided people made the British, as one scholar puts it, ‘almost irrationally anxious’.Footnote 90 After local tribesmen killed or wounded all British military officers in Tochi in June 1897, people along the frontier (including the Afridis) rose up in arms against an expanding colonial regime. General William Lockhart led an unprecedented military attack on the Afridis with an army of 40,000 troops during the legendary ‘Tirah Campaign’. In 1898, the Afridis entered into a new agreement with colonial authorities, pledging no objection to the government's construction of railways or roads through the Khyber Pass. A few years later, the government considered (but decided against) a proposal to forcefully extend British political control over an Afridi tract at the Kohat border, reasoning that to do so would require ‘holding down, in the most difficult of countries, some of the fiercest, most treacherous, and most fanatical people in the world’.Footnote 91 As the Khyber Pass grew in strategic importance, the Afridis became even more critical to frontier-security policy. In 1915, NWFP Chief Commissioner George Roos-Keppel called the Afridis ‘the keystone of the frontier arch’.Footnote 92

Beginning in 1901, colonial officials began to observe a steady annual increase in crime in the settled districts.Footnote 93 In 1919, a sharp escalation in the incidence of serious crimes was attributed to a variety of explanatory factors, including ‘the general disregard for human life in the minds of many who had fought in the Great War’; the scarcity and high prices that were a legacy of the war; the exponential increase of arms in the region; and the ease with which criminals and outlaws could jump the internal boundary and find asylum in the tribal tracts and across the Durand Line in Afghanistan.Footnote 94 An ongoing source of tension between the Government of India and the Amir of Afghanistan was the problem of frontier crime—raids, robberies, murders, kidnappings for ransom—and the difficulty of arresting perpetrators who escaped through the tribal tracts into Afghanistan.

The Third Anglo-Afghan War, though short, led to a marked increase in tribal resistance and what colonial officials generically called ‘lawlessness’. India's Foreign Secretary Denys Bray referred to the ‘orgy of kidnapping’Footnote 95 of mostly Hindu subjects that ultimately led to military operations against Waziristan, beginning in late 1919 and lasting for four years. Punitive expeditions and aerial bombings were met with fierce opposition and armed attacks, a number of which were aimed specifically at colonial personnel (including the murder of the Foulkeses in November 1920). A few weeks before Molly Ellis was kidnapped, Majors N. C. Orr and F. Anderson of the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders were shot dead while walking along the Mullagori Road in Landi Kotal in Khyber.Footnote 96 One of the officers was wearing a white solar topi (hat), the quintessential sartorial symbol of colonial power. The murderers were later seen wearing the topi, which the British likely interpreted as a triumphant display of a successful headhunting expedition.Footnote 97 This combination of factors had the Kohat border in what one official called a ‘disturbed state’.Footnote 98 John Maffey described the region as being in a ‘state of siege’.Footnote 99 It was within this atmosphere of violence, fear, insecurity, and alarm that British officers and their families were practically confined to the cantonments.

A heroine's tale of maternal imperialism

During the long journey into tribal territory, Molly walked, rode a donkey, and was carried on the backs of the men who had kidnapped her and killed her mother. Leaving the cantonment, the group moved west, criss-crossing the hills and riverbeds, travelling mostly at night and laying low during the day. Wearing her nightgown, a coat, shawl, and the leather-soled socks that the men gave her, Molly could see cars, troops, and cavalry passing along the Peshawar-Kohat Road—an artery marked by a history of colonial conflict. They travelled 80 miles over six days, arriving at dawn in what Molly later described as a ‘lovely valley’ with quaint villages, pine trees, and wild flowers. This was Khanki Bazar. From there, Molly was taken six miles farther to the house of Sultan Mir, where a group of women lay her on a charpoy and massaged her from head to toe before feeding her boiled eggs and chapati (bread). For the next three days, according to Molly, ‘they used to spend most of the day staring at me through the open door of a smaller, inner room on which there was an armed guard all the time’.Footnote 100

Lilian Starr, a nurse at the Peshawar Mission Hospital, nervously tended to her patients in the days following Molly's abduction: ‘As we looked first at one patient, then another, into facts, some strong and manly, some coarse and even brutal, we would say to one another: “Think of her in the hands of that one—or that”.’Footnote 101 On 19 April, a letter arrived from Sir John Maffey summoning her to the Government House. When she arrived, Maffey expressed his concern that sending a military force would cause the group to harm Molly or to take her farther into tribal territory. He asked her ‘to go simply as a trained nurse, to get to her if possible, and to stay with her wherever she was until she could be rescued’. Mrs Starr noted that ‘[h]e warned me of the risks, but I was naturally most anxious to go’.Footnote 102

On 20 April, Mrs Starr departed with Maffey in a motorcade. She had packed Afridi dresses for herself and Molly, as well as medical equipment, biscuits, chocolates, tinned food, a camera, and 25 gold sovereigns that Maffey gave her to use in case of emergency. She kept a diary of her journey, which formed the basis for her published account entitled ‘An Errand of Mercy: The Search for Miss Ellis among the Afridi’.Footnote 103 In the account, Starr describes the search-and-rescue mission from multiple perspectives—hers, Kuli Khan's, and Molly's. Her narrative provides a rich and detailed description of the landscape, the architecture, the plant and animal life, and the people she encountered along the way. The text is filled with many familiar colonial stereotypes about a culture-bound people stuck in what literary theorist Anne McClintock calls ‘anachronistic space’.Footnote 104 She describes the tribes ‘living today in the customs and habits of some six hundred years back’Footnote 105 as

fierce and lawless, wild and masterless, yet in their reckless fashion they are brave—true highlanders with an inborn love of fighting, and a pluck and hardiness one cannot but admire … treacherous and cruel, capable sometimes of strong affection, often of a deep hatred, and an unrivalled tenacity in holding to his highest ideal, which is revenge.Footnote 106

At the administrative border, Starr left Maffey behind and proceeded by horseback into semi-independent tribal territory with his Indian personal assistant Khan Bahadur Risaldar Moghal Baz Khan (an Afridi) and a jirga of 40 tribesmen on foot. Mrs Starr's was the first peaceful visit of a Briton to Tirah since Lockhart's brutal military campaign in 1897. ‘They only come fighting,’ one man told her along the way.Footnote 107 As they travelled through each distinct tribal territory, one jirga would pass the group on to the next, ‘the men running alongside our horses to conduct us through their area and to hand us over to the next’.Footnote 108 At the Risaldar's insistence, Mrs Starr covered her khaki solar topi with a white pagri (turban) and cloaked her khaki riding kit in the typical Afridi woman's black-and-red-bordered black chaddar to disguise her identity as an ‘English sahib’. This, he reasoned, would protect her from snipers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. This photograph of the successful search-and-rescue mission was taken in Khanki Bazar before the group returned to British territory on 22 April 1923. Lilian Starr stands in the rear, her head covered by an Afridi chaddar. Molly Ellis is seated at front wrapped in a similar chaddar brought by Mrs Starr from Peshawar. Source: © British Library Board (Photo 627/76).

Khan Bahadur Kuli Khan reached Khanki Bazar before Mrs Starr did. On 21 April, he met with Ajab Khan, his brother Shahzada, and Mullah Mahmud Akhundzada, a local religious figure, to negotiate terms for Molly's release. The following day, as punitive forces advanced—‘Our houses are burned. Our women are killed,’ Shahzada lamentedFootnote 109—Ajab and his men agreed to let Molly go in exchange for the promise of their freedom, the release of two Bosti Khel Afridis imprisoned for theft in the Kohat jail, and a pledge that no future punitive fines or action would be taken as retribution.Footnote 110 Mullah Akhundzada was promised payment of Rs 15,000 for ‘expenses’ incurred, although great pains were later taken by colonial officials to ensure that this payment was not seen as a ransom.

When Mrs Starr first met Molly in Khanki Bazar, she was ‘lying on a charpoy looking white and played out, though physically absolutely uninjured and scarcely even bruised’.Footnote 111 On the morning of 23 April, the two women travelled 30 miles back to the Shinawari Fort in British territory, where they were reunited with Maffey and Molly's father, Major Ellis (see Figure 3). In addition to a variety of written narratives, there is a compelling visual archive documenting this event. A series of 25 ‘Photographs taken by Mrs. Starr in Tirah’ were printed by a government press in Peshawar. Many of these photographs appear in Mrs Starr's published account and in contemporary newspaper reports. The full series (and more) were preserved by the viceroy's wife, Lady Hardinge, some loose in boxes and others glued into a scrapbook with descriptive captions.Footnote 112 Unfortunately, we do not know more about the conditions under which the photographs were taken, printed, and circulated.

Figure 3. This photograph was taken on 23 April 1923, the day Molly returned from tribal territory to Shinawari Fort. Recovered and re-Anglicized, she is dressed in Mrs Starr's white sun hat and stands next to Moghul Baz Khan, a hybrid figure in a necktie, turban, and overcoat. Lilian Starr, back in British territory, is also dressed in British clothes, donning a khaki solar topi and riding kit as she clutches a notebook to her chest. At the far right, Chief Commissioner Sir John Maffey and Major Ellis (smoking a cigarette) oversee the group as symbolic white fathers in solar topis. Source: © British Library Board (Photo 627/76).

The English-language stories and newspaper reporting about Molly Ellis's kidnapping and rescue reflect the generic structure of an imperial adventure narrative: a perilous journey presented a series of obstacles that culminated in a decisive face-off between the hero and his enemy.Footnote 113 In tales of imperial adventure, the typical hero was a man.Footnote 114 Lilian Starr's involvement in this particular imperial ‘adventure’ is somewhat unusual, as is the fact that she authored her own tale. Starr's account has all of the usual narrative elements found in an adventure tale: a quest, bad guys, a brooding mystic, and a fearless hero who sets off into the wild with derring-do and dutiful conviction.

The heroism that Lillian Starr demonstrated in Molly's rescue did not conform to the imperial ideal of a chivalric masculine adventure. Whereas the iconic imperial hero was a ‘lean and keen’Footnote 115 man who used physical force to advance and defend imperial interests, Lilian Starr portrays herself as a compassionate and conciliatory character who connected with local people at every step of her dangerous journey. Displaying the masculine virtues of courage and self-sacrifice, she emerges from her own story as a peacemaker and bridge-builder who managed to win over even her staunchest sceptic, the Mullah Akhundzada. According to Starr, before leaving Khanki Bazar, she provided medical care to almost 30 people, including members of Mullah Akhundzada's family. As she and Molly rode past on horseback, women and children called out, ‘Come again some day’.Footnote 116

The life of Lilian Starr reveals how white women in the empire both conformed to and stretched normative gender roles and expectations. As historian Mary Procida once observed, ‘[t]he empire may have been masculine, but it was certainly not exclusively male’.Footnote 117 Born in India, Lilian Starr worked alongside her husband, Dr Vernon Starr, at the Peshawar Mission Hospital. She vaccinated children; removed bullets from the shattered limbs of men, women, and children; and with ‘gentle hands’Footnote 118 provided care to the sick, the injured, and the sometimes mutilated bodies of those who fell victim to ‘blood feud’. After a ‘fanatic’ stabbed her husband to death in their home in Peshawar, Mrs Starr worked as a military nurse in Cairo during the First World War, performing the feminine duty of tending to male soldiers in service to empire and nation. She returned to Peshawar in 1920 to serve in the city where her father had once worked.Footnote 119

In a space where the display of British power was muscularly masculine and the emphasis on projecting overwhelming strength and dominance was unyielding, Lilian Starr's role as an agent of empire was cast in the tradition of maternal imperialism.Footnote 120 Mrs Starr, who had no children of her own, assumed the duty of maternal protector after Mrs Ellis died defending her daughter. She put her life on the line to achieve ‘the impossible’, valiantly retrieving Molly ‘unharmed’ from ‘the wilds of Tirah’.Footnote 121 As Maffey observed: ‘With the charm of her fair face and a woman's courage, she [Mrs Starr] made a mark on the heart of Tirah better than all the drums and tramplings of an army corps.’Footnote 122 Contemporary newspaper accounts highlighted Starr's heroic bravery and courage in the face of ‘hair-raising’ conditions.Footnote 123 Under the headline ‘Woman's Heroic Mission’, The Times described ‘the element of romantic heroism [that] has been introduced into the rescue operations by Mrs. Starr … the one woman who could do this’.Footnote 124 The Viceroy awarded Mrs Starr the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for Public Service in recognition of her ‘heroic endeavor’ (see Figure 4).Footnote 125

Figure 4. Lilian Starr wearing the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for Public Service in India awarded to her by the viceroy in 1923.

As soon as Mrs Starr had fulfilled her soft role in the rescue mission, the hard hand of imperial retribution came crashing down, leaving much of the valley (as she herself put it) ‘in smoking ruins’.Footnote 126 Local lashkars entered the villages of Ajab Khan and Sultan Mir and destroyed their houses.Footnote 127 Maffey was eager to move quickly and exact vengeance: ‘We strike now while the iron is hot.’Footnote 128 It was Ramadan and he wanted to seize the strategic advantage: ‘There is no war spirit whatsoever in the tribes at present.’Footnote 129 On 8 May, the Royal Air Force flew 15 aeroplanes in formation over Khanki Bazar at such low altitude that onlookers could see the pilots’ faces. The air demonstration was choreographed to frighten the tribes with the spectre of aerial bombing just days before Maffey's scheduled jirga with the Afridi and Orakzai tribes.

On 13 May, Maffey presented the tribes with an agreement that declared Ajab Khan and his accomplices as ‘our own enemies’. The men were banished from the region and the tribes bound to arrest and surrender them to the government should they return. The agreement gave the government ‘authority (by aeroplanes or otherwise) to take such action as may be suitable’ if any members of the tribes gave ‘passage or harborage’ to them.Footnote 130 As Maffey noted in an official telegram: ‘The Jirga was conducted throughout in a stern spirit with Tirah under immediate threat of reprisals and war. The proper atmosphere for very straight talking was thus produced.’Footnote 131 As was often the case with punitive expeditions, the government used the kidnapping as an opportunity to expand the state's material interests in the name of imperial security.Footnote 132 At a second jirga held with the Kohat Pass Afridis on 21 May, an agreement was signed that permitted the construction of telegraph and telephone lines through the Kohat Pass from Peshawar to Kohat with intermediate telephone stations and the placement of frontier police posts to guard them.Footnote 133

The others’ side of the story

In a series of letters written—or at least inspired—by Ajab Khan, he defied official efforts to disappear him by telling his side of the story.Footnote 134 Ajab Khan's written correspondence represented an act of resistance in a region where, after a century of British occupation, only 6 per cent of men and 1 per cent of women in the settled districts were literate (and even fewer in the tribal tracts).Footnote 135 Ajab Khan was one of the few ‘fanatics’ who was never captured, much less killed, by colonial authorities. Living to tell his tale gave Ajab epistolary agency and made it possible for other storylines to emerge, including his own.

Ajab's letters present a chronology and rationale for his actions that are similar but not identical to those outlined by colonial authorities. ‘It is known to you,’ he writes to Kuli Khan, ‘that the quarrel and the case that I have against the British Government is a revengeful one.’Footnote 136 According to Ajab, his badla with the British government began in 1920 when ‘the tyrannical officers of the frontier’ implicated him ‘without any proof’ in a theft of 120 rifles from the Kohat Lancers and prohibited his entry into the settled districts: ‘For two years I cried that my guilt should be proved.’Footnote 137 In 1922, he personally handed ‘the Viceroy’ a letter asserting his innocence, ‘but the frontier officers paid no heed to this and began to worry me all the more. They auctioned my goats and [then] I took away 46 rifles from the Police Lines in retaliation’.Footnote 138 (Presumably, Ajab handed the letter to Foreign Secretary Denys Bray, who toured the tribal tracts in the spring of 1922 as head of the North West Frontier Enquiry Committee.) Ajab makes no mention in his letters of any involvement in the Foulkes's murder, just as colonial officials make no mention in their records of Ajab's implication in a 1920 rifle raid, his banishment from the settled districts, his encounter with Bray, or the seizure of his goats.

Ajab frames the kidnapping of Molly Ellis as a proportional act of badla (revenge) against a disproportional act of zulm (oppression). By his account, the murder of Mrs Ellis was unintentional. Expressing outrage at the ‘cowardly night attack on our free country’ (namely Handyside's counter-raid), he charges frontier authorities with ‘exceed[ing] the limit of moderation’, ‘overaw[ing] the innocent women folk’, and ‘carr[ying] off a few of our Moslem brothers in custody’.Footnote 139 Ajab highlights the asymmetry between the honourable way in which he treated Molly ‘like a respectable guest’ and the dishonourable way in which the colonial government abrogated the ‘solemn promise and written agreement’ offered in exchange for her release.Footnote 140

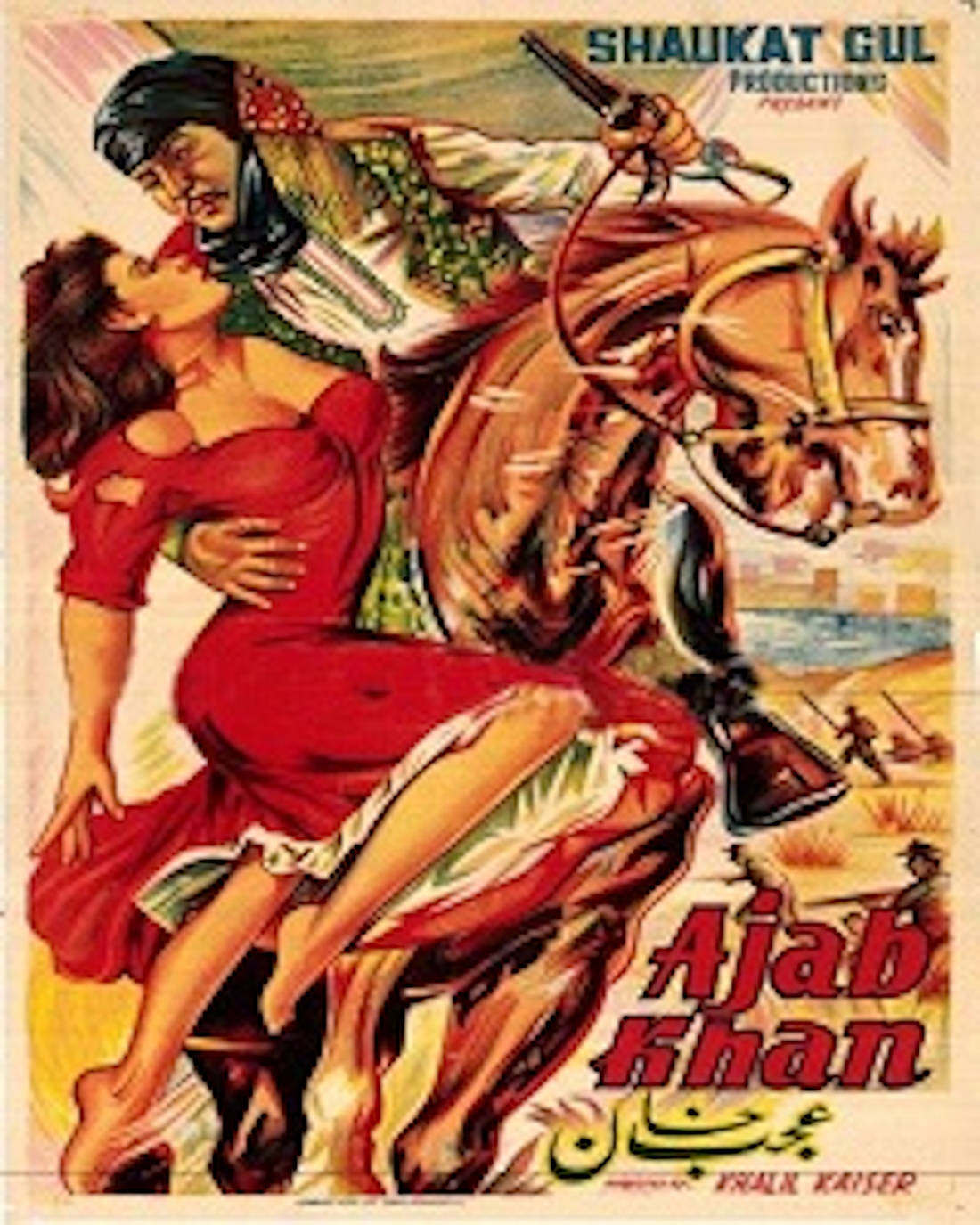

The vernacular stories that circulate about Ajab Khan in Pakistan and Afghanistan take aim at the structural violence of empire and position Ajab as an avenger of the wrongs of the colonial system. A recurring feature in these accounts is the contrast between Ajab's protection of Molly's honour—there are clear sexual connotations in the repeated assertion that Molly was rescued with ‘her honour intact’—and the disrespect shown by colonial officials during Handyside's counter-raid. Muhammad Ibrahim Athaee writes: ‘Though Ajab Khan killed British soldiers, he kept the honor of Molly Ellis, the lady he kidnapped.’Footnote 141 Ajab Khan is imagined not only as a brave Pashtun hero who stood up to British tyranny, but also as a valiant masculine hero and guardian of female virtue. Many film versions of the story emphasize a steamy, romantic plot line with Molly falling in love with Ajab and expressing her desire to stay in the mountains with him forever.Footnote 142 The poster for Khalil Kaiser's 1961 hit Ajab Khan represents Molly as a bodacious Hollywood siren in a figure-hugging, low-cut red dress. She gazes up longingly at her captor, who holds her tightly to him with one arm as he clutches a rifle and steers a bucking bronco with the other (see Figure 5). The sexy imagery notwithstanding, the films (along with other Afghan narratives of the story) place great emphasis on the fact that Molly's ‘honour’ (virginity) was protected when she was in Ajab's custody.Footnote 143

Figure 5. This racy film poster for the Khalil Kaiser's 1961 Urdu-language film hit Ajab Khan sexualizes the incident even though most written vernacular accounts emphasize that Molly's ‘honour’ was not violated.

The figure of the violated Pushtun woman is a repeated trope in the ballads and films that celebrate Ajab Khan's heroism. In the Pashto-language verse narrative published by Jamshed of Topi in 1964, Ajab's defence of his mother's honour is a prominent theme. Jamshed's narrator notes:

When Ajab Khan came home, he greeted his mother respectfully. His mother said, ‘Keep out of my sight, you're a disgrace, may black earth be heaped upon you! I can't hold up my head before our tribe and I sit reproached by high and low. The British took from us our honor and they vilely exposed the women. The tyrants unveiled our young girls and they took away the young men's rifles too. If in truth you are my son, you will openly take revenge on the British. If there's any cowardice in you, my son, I'll shed no tears about your death. I won't look upon your face in its shroud, and I won't allow your grave on our land either. Among Pathans, it's only when you bring forth brave offspring that ancestors’ names are recalled with honor.’ The women and girls surrounded Ajab Khan and they wept and told him the whole story. They said to him, ‘There's been a great wrong done to us and there's no one to complain to except you. We long for revenge to be taken, for living with lowered eyes is very difficult.’ His mother also cried, weeping and wailing and her face was as red as a pomegranate flower with rage. O Jamshed, Ajab Khan was silent before them! Honor had set his body boiling.Footnote 144

In Jamshed's narrative, the kidnapping represented an assertion of Pushtun masculinity: ‘He was a valiant Pashtun whose manliness was not doubted!’ Jamshed represents Ajab Khan in explicitly gendered terms as a ‘real man’:

My friends, all the British are thorns in my eyes! I resent it when we are humiliated and when the Englishmen consider us as slaves. When Pashtuns salute the British, it is like falcons being servants to crows. Thinking about this to myself, it makes me weep, for lions have become obedient to jackals! Those Pashtuns who used to smash the enemy's teeth are now beneath the earth. But my heart is set on fighting with the British and I'll make the tyrants open up their eyes. I won't pass my life with eyes lowered, that's a promise! And I'll be remembered as a real man until the Resurrection.Footnote 145

In colloquial terms: real men resist the emasculation of empire.

In both the honour culture of the colonizer and that of his tribal nemesis, acts of gendered violence restored masculine authority. In Ajab's case, the attacks and raids that led to counter-raids and punitive expeditions were triggered by male aggression against women in intimate, domestic spaces. The assault on the women of Bosti Khel transpired in front of their village homes and involved a disrobing of sorts. The abduction of Molly Ellis and the murder of her mother occurred in the bedroom of their official household. Just as Ajab Khan decried the violation of his mother's purdah, the British condemned the laying of hands on ‘their women’ as the ultimate attack on what Commissioner Maffey called ‘British life and honour’.Footnote 146

Conclusion

India's North-West Frontier was defined by successive generations of colonial officials as a primitive space populated by savage tribes who only understood the language of force. In 1924, the Government of India published specific guidelines for the ‘Employment of Aircraft on the North-West Frontier of India’. The document opened with typical observations on the ‘special’ nature of ‘The Frontier Problem’:

The problem of controlling the tribal country on the North-West Frontier of India has always needed special treatment by reason of the psychology, social organization and mode of life of the tribesmen and the nature of the country they inhabit …. Hesitation or delay in dealing with uncivilized enemies are invariably interpreted as signs of weakness.Footnote 147

The sociological theory of masculine overcompensation helps to explain the colonial concern with displaying ‘no signs of weakness’ in a region where they were both terrified and terrifying.Footnote 148 Colonial violence on the frontier was not simply about protecting a vulnerable geopolitical space; it also aimed to assert white masculinity and fortify the race–gender hierarchy upon which the empire was built. Such violence was often embedded in local forms, including barampta, bandish, and badla. When John Maffey convened the Afridi jirga on 13 May, he told them: ‘we had now cause for a badla (feud) with them of the worst type—the badla over a woman, which by their own custom must be paid in blood.’Footnote 149 The idea of a badla aimed at righting a particular wrong contradicted the colonial notion of a murderous outrage prompted by irrational religious fanaticism.Footnote 150

White women appeared in this space of security theatre to perform official comfort and confidence. Prior to Molly's abduction, precautionary measures had been taken to protect the wives of British officers on the frontier—restricting their movement, surrounding the cantonments with barbed wire, installing night guards, and prohibiting the entry of women and children in certain areas. However, the state was hesitant to adopt too much extra security lest it give an impression of fear, vulnerability, and effeminacy.Footnote 151 A Permanent Standing Order prohibited officers from having guards stand directly over their bungalows, which is why Major Ellis had given his wife a whistle to blow in the event of an emergency.Footnote 152

Colonial ideas about frontier fanaticism were so durable that, even where rational political motivations were well known, as in Ajab Khan's case, high-level officials continued to insist that ‘behind individual motives lies the spirit of fanaticism’.Footnote 153 In November 1923, another ‘outrage’ occurred in Parachinar, a small cantonment in the Kurram valley, just 35 miles north-west of Khanki Bazar. In the middle of the night, Captain Edward Watts and his wife Elsie were killed in their bungalow. No valuables were taken. No alarm was raised. Not even the dogs budged. Although the perpetrators left no clues, authorities connected the incident to Ajab's ‘Kohat gang’. Shortly after the murder, Mrs Ella Giles, Elsie Watts's mother, wrote a letter to the editors of the Daily News. Under the headline ‘Murdered White Women’, Mrs Giles inquired: ‘Why does the Indian Government allow British women in these places? Greater precautions should have been taken at Parachinar where Captain and Mrs. Watts were murdered …. What has the Indian Government to say? The greatest insult a native can give a white man is to abduct his womenfolk.’Footnote 154 Members of parliament discussed the ‘safety of European ladies’ on the frontier and wondered whether the time had come for them to go.Footnote 155 One official warned that ‘a panic measure of this description would be absolutely fatal to British prestige’.Footnote 156 In a secret dispatch to the Government of India, frontier authorities speculated about why the tribes had recently begun to target English women:

One theory to which publicity has been given, and for which the authority of local knowledge is claimed, is that the frequent use of aeroplanes for what amounts to police rather than military work, and the resultant indiscriminate bombing of men, women, and children in tribal country, is responsible for the adoption by the tribesmen of what is in their eyes a policy of retaliation.Footnote 157

The abduction and murder of British women were thus interpreted as an indigenous version of the ‘punitive expedition’—a quick and spectacular method of sending a strong message to punish a perceived wrong.

Ajab's case caused an acute crisis in British diplomatic relations with Afghanistan where he and his brother were rumoured to have taken refuge. British authorities insisted that ‘in accordance with the usage of civilized nations’,Footnote 158 the men should be denied harbourage. However, their demand had little traction because the Government of India and the Amir of Afghanistan did not have a mutual extradition treaty. The anomalous legal status of the tribal tracts made a reciprocal agreement for the exchange of criminals impossible, as colonial authorities had no legal jurisdiction over people beyond their internal administrative boundary. In December 1923, British women were withdrawn from the legation in Kabul in a diplomatic move intended (unsuccessfully) to pressure the Afghans to turn over Ajab and his brother.

The colonial government persevered for a decade in a relentless pursuit of Ajab Khan and the ‘Kohat gang’. Of the four members, only one was captured. Gul Akbar was arrested in Peshawar City on 9 May 1927 and hanged two days later.Footnote 159 Ajab Khan and his brother Shahzada both escaped to Afghanistan. Shahzada died in Mazar-i-Sharif in 1958. Ajab died there several years later. Sultan Mir's fate remains unknown. Although the case was officially closed in March 1983, following Molly Ellis's trip to Kohat to visit the gravesite of her mother, memories of the incident endure.