Introduction

Known as the warlord period in modern Chinese history, the years following the death of President Yuan Shikai in 1916 witnessed the rise and fall of political factions and military groups vying for dominance under the Republican government in Beijing, prior to the establishment of the Nationalist government in Nanjing as a national regime in 1928. The activities of individual warlords in different parts of the country have been the subjects of many studies in the past.Footnote 1 Positive signs of development undoubtedly emerged under the warlord regimes, such as industrial growth, the freedom of the press, the flourishing of cultural institutions, the introduction of parliamentary rule despite its overall dysfunctionality, and the impressive quality of Cabinet members, as some studies have documented.Footnote 2 Nevertheless, the dominant image in the writings on this period remains the one of extreme fragmentation and chaos in domestic politics, recurring war and social disorder, countless taxes on the people, and national humiliations at the hands of foreign powers.

To explain the success or failure of the warlords, scholars have typically emphasized the role of personal ties or factionalism, especially when discussing the old-fashioned warlords in North China.Footnote 3 Others pay more attention to the importance of ideological propagation and party organization when accounting for the rise of the Nationalist (or Guomindang) forces in the southern provinces.Footnote 4 But this juxtaposition between the northern and southern forces should be taken with caution. As it turns out, some of warlord leaders or regimes in North China displayed a clear nationalist stance when handling foreign conflicts for the sake of national interests or their personal fame.Footnote 5 By contrast, Sun Yat-sen, as the early leader of the Guomindang, actually went further than the northern warlords in seeking support from Japan at the cost of China's sovereignty regardless of his anti-imperialist rhetoric, and his successor, Chiang Kai-shek, was equally dependent on old-styled, private relations in building his leadership and personal control of the Nationalist state.Footnote 6

Instead of discussing factionalism, ideology, or war efforts, this article focuses on an analysis of geopolitical and fiscal factors that have been understudied in the past, to distinguish the ‘winners’, or the regional forces that survived the prolonged competition and even came to dominate the central government, from the ‘losers’, or the vast majority of contenders who were subjugated and eventually eliminated or incorporated by the winners. It aims to offer a new interpretation of the dynamics of military rivalry among the warlord cliques, and to explain the extent to which the state-building efforts of regional contenders in China resembled, or deviated from, the experiences of nation states in early modern and modern Europe.

Methodologically, this article examines warlordism in China from the perspective of state formation or modern state-making. Unlike the studies of political development or modernization that tended to conceptualize—and indeed oversimplify—the path to modern nation states on the basis of teleological assumptions, research on the formation of modern European states, which emerged as a new field in the 1970s, underscored the role of war in the actual process of state-making. The constant rivalry and wars among the states, it is argued, drove each of them to rebuild state apparatuses for efficient extraction of economic resources to sustain war efforts, thus making the government system increasingly centralized and bureaucratized, and turning the armed forces from one of predominantly mercenaries to standardized and regularized standing armies strengthened by a military revolution.Footnote 7 As a result of intensified war and annexation of the losers by the winners in interstate rivalry, the number of states decreased from hundreds in different forms and sizes in the fifteenth century to only a few dozens in the nineteenth century. What shaped the course and results of interstate competition, as the more recent studies have demonstrated, are the peculiar geopolitical setting that confronted each state and its socio-economic conditions, in particular, its fiscal constitution (namely, the sources and magnitude of the revenues and expenditure of a given state), which ultimately determined the country's military strength and survival abilities. Thus, the states that emerged in early modern and modern Europe are commonly termed as ‘fiscal-military states’.Footnote 8

Geopolitical settings and fiscal constitution are also the key factors shaping the results of military competition among the regional forces in different parts of China. Central to my arguments that follow is the concept of ‘centralized regionalism’. In other words, what characterizes warlord politics in Republican China is first of all regionalism. The individual provincial governors or regional leaders formed different warlord cliques to dominate one or several provinces and establish their exclusive control of local administrative, fiscal, and military resources, while the central government in Beijing was reduced to a nominal authority, having lost entirely or in large measure its control of those provinces. What determines the abilities of the individual warlords to compete with one another and distinguishes the winners from the losers in such rivalries, however, is first of all how the warlord regime centralized itself, or the effectiveness of the mechanisms through which it mobilized and utilized the resources available from the region under its control to build its fiscal and military strengths. Geopolitical and socio-economic conditions also mattered. Those who enjoyed a relatively secured geopolitical position and at the same time established a centralized apparatus for resource extraction, especially the taxation of commence and urban economy, and had access to the modern means of financing would be able to build a more powerful fiscal-military regime and prevail in the competition for national dominance. The most competitive force, therefore, was invariably the one that possessed not only a well-endowed and secured region, but also a highly centralized machine of control and extraction. In contrast, those who failed to establish their stable control of a region and a centralized regime would inevitably lose the competition and be wiped out or subjugated by the winner.

The making of the modern Chinese state, therefore, took the form of centralization of regional regimes vying for national dominance through military competition. This regional-to-national or bottom-up process of state-building contrasts sharply with the top-down path found in the history of first-comers in state-making, most notably England and France, where a pre-existing central government asserted its authority throughout the country by unifying and bureaucratizing the administrative system and eliminating local religious or other governing institutions that had resisted the state. China's experiences in the early Republican period resembled more or less the bottom-up path prevailing among the latecomers such as Germany, Italy, or late Tokugawa Japan, where regional powers played a leading role in building a centralized and unified state.

Winners and losers in warlord competition

The central government crippled

The emergence of warring regional cliques in early Republican China can be traced to the decentralization of fiscal and military power since the late 1850s, when the Metropolitan and Coordinate Remittance systems—a device used by the central government to centrally control the revenues generated by local authorities—collapsed because of the Taiping Rebellion. Consequently, provincial governments were allowed to keep the remainder of whatever they had collected and controlled after fulfilling two basic categories of obligations: (1) zhuanxiang jingfei, or fixed quotas of annual remittance to the central government for specific civilian and military purposes, and (2) tanpai, or the compulsory sharing of foreign debt and war indemnities, which first occurred in 1895 after the Sino-Japanese War and dramatically increased after 1901.Footnote 9 The Qing court, to be sure, attempted repeatedly to formalize and recentralize the provincial governments’ collection and management of taxes, customs, and fees in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Especially noteworthy was its systematic efforts in the last few years of the dynasty to investigate the fiscal condition of provincial authorities, which resulted in dramatic increases in the formally reported quantity of local revenues, to centralize its control of the salt tax, which soon surpassed the land tax and maritime customs to be the largest source of revenue, and to establish a modern budget system.Footnote 10 The outbreak of the Revolution of 1911, however, interrupted all these progressions toward fiscal centralization.

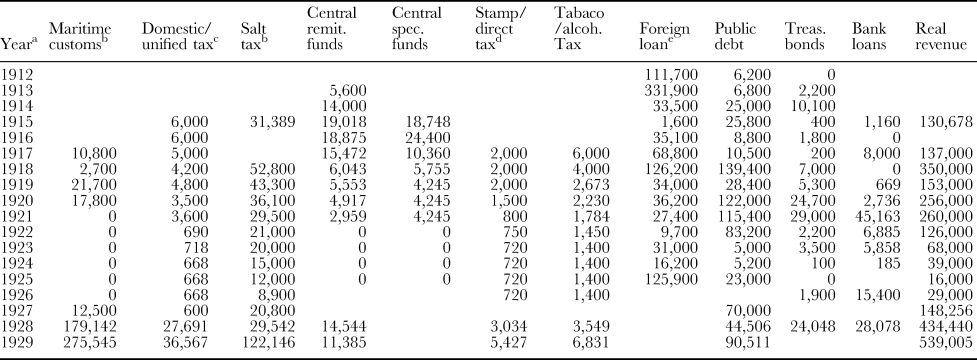

The Republic government in Beijing, therefore, had only a few million yuan annually at its disposal, mostly from the salt taxes and domestic customs from adjacent provinces in 1912 and 1913, whereas its administrative and military expenses amounted to 4 to 5 millions a month.Footnote 11 The only way to meet the state's fiscal needs was seeking foreign loans and issuing government bonds, the largest of which was the so-called ‘grand debt for postwar rehabilitation’ (shanhou da jiekuan) of 25 million pounds (equivalent to 248.3 million yuan), made by the banking groups of five foreign countries to the central government under President Yuan Shikai in April 1913.Footnote 12 In the following years, as Yuan Shikai gradually consolidated his power over individual provinces, he was able to re-establish the revenue-sharing system and provincial governments had to submit to Beijing a fixed quantity of local tax funds. The remittance of the shared tax funds (zhongyang jiekuan) increased from 5.6 million yuan in 1913 to 14 million in 1914 and 19.02 million in 1915, when Yuan was at the height of his political influences (see Table 1). In addition, the Yuan government was also able to obtain from individual provinces a growing amount of tax income that was designated as revenues belonging exclusively to the central government (known as zhongyang zhuankuan), including the taxes on deeds, stamps, salt and tobacco sales and licences, and sales commissions; Beijing government's revenue from this source increased to more than 18.7 million in 1915 and 24.4 million in 1916 (Table 1). Combined, the revenues that the Yuan government obtained from the provinces reached nearly 38 million yuan in 1915 and more than 43 million yuan (equivalent to roughly 30 million taels) in 1916, which were more than the special funds that the provinces owed to the Qing court in the late nineteenth century (22 million taels).Footnote 13 This was undoubtedly a considerable achievement toward the goal of fiscal and military recentralization, to which the Yuan Administration had committed. In the absence of serious challenges after suppressing the rebellion in the southern provinces, Yuan indeed appeared to be the most competent leader to re-establish political order in China.

Table 1. Revenue of the central government of the Republic, 1912–29 (in 1,000 yuan)

aData from 1912 to 1926 are in silver dollars (yin yuan). Statistics of the years from 1938 to 1945 are recalculated into the amounts in the fixed value of the fabi (legal tender) in 1937 (see Yang Yinpu 1985: 159). bMaritime customs and salt taxes before 1928 were the remainders of the custom dues (guanyu) and remainder of salt taxes (yanyu). cThe data under ‘domestic/general tax’ before 1928 are the amounts of domestic regular taxes (changguanshui) and the data after 1928 are the amounts of the unified tax (tongshui 統稅). dThe numbers under ‘stamp/direct taxes’ refer to stamp tax before 1940 and various direct taxes (including stamp tax, income tax, and sales tax, and so on) (see Yang Yinpu 1985: 112). eForeign loans in 1938–42 and 1944 were in US dollars (Yang Yinpu 1985: 153).

Sources: Yang Yinfu 楊蔭溥 (1985), Minguo caizheng shi 民國財政史 [A Fiscal History of the Republic of China], Zhongguo caizheng jingji chubanshe, Beijing, pp. 7–8, 10, 12, 15–16, 22, 45, 47, 64, 104, 107, 109, 112, 150; Jia Shiyi 賈士毅 (1932), Minguo xu caizheng shi (1) 民國續財政史(一)[Supplement to the Fiscal History of the Republic of China], vol. 1, Shangwu yinshuguan, Shanghai, pp. 55–63, 158–159; Jia Shiyi (1933), Minguo xu caizheng shi (2) 民國續財政史(二)[Supplement to the Fiscal History of the Republic of China], vol. 2, Shangwu yinshuguan, Shanghai, pp. 160–170, 199–206, 296–299, 409–410, 556–559; Jia Shiyi (1934), Minguo caizheng shi 民國財政史 [A Fiscal History of the Republic of China], Shangwu yinshuguan, Shanghai, pp. 60–61.

Unfortunately, Yuan's failure to establish an imperial regime and his subsequent death in June 1916 opened the door for the recurrence of political chaos and military rivalry among the different cliques of power contenders in the next decade. A central government continued to exist, but it was fiscally weak, due to the disappearance of provincial contributions (jiekuan and zhongyang zhuankuan) after 1922, which had been the major sources of the government's regular revenues during Yuan's presidency, and due to the ending of its revenues from the ‘maritime customs surplus’ (guanyu) (most of the maritime customs had been retained by the Maritime Customs Service as repayment of foreign debts and war indemnities) after 1921. The ‘salt taxes surplus’ (yanyu), the largest source of domestic revenues in the 1910s (again, most of the salt taxes had been retained as payment of foreign debts since 1913), also diminished in the 1920s, to less than 9 million yuan by 1926.Footnote 14 Thus, the Beijing government had to rely increasingly on foreign loans and government bonds, which brought its total revenue to as high as 350 million yuan in 1918. As the central government's borrowing abilities dwindled in the following years, however, its annual revenue also decreased to 126 million yuan in 1922 and only 29 million yuan by 1926 (Table 1).

In sharp contrast with the poor and feeble government in Beijing was the steady build-up of fiscal and military strength of provincial warlords in the 1910s and 1920s. Three major cliques of warlords prevailed in North China. Although the territories of each clique varied over time, the situation in June 1920 prior to the outbreak of the war between the Anhui and Zhili cliques gives a good idea of their main base areas.Footnote 15 The Anhui clique controlled eight provinces (Shanxi, Shaanxi, Shandong, Anhui, Zhejiang, Fujian, Gansu, and Xinjiang as well as two special administrative zones, Rehe and Chahar). The Zhili clique occupied five provinces (Zhili, Jiangsu, Henan, Hubei, and Jiangxi as well as Suiyuan and Ningxia). The Fengtian clique ruled three north-eastern provinces (Fengtian, Jilin, and Heilongjiang). In addition, there were minor warlord factions including the Guangxi clique that occupied Guangxi and Guangdong, and the Yunnan clique that dominated Yunnan and Guizhou.

The weakness of the Anhui and Zhili cliques

In terms of their fiscal strength, the first two cliques were quite comparable to each other: the revenues of the eight provinces and two zones of the Anhui clique totalled about 54 million yuan, while the five provinces and two zones of the Zhili clique generated a total of nearly 51 million yuan.Footnote 16 The resemblance between the Anhui and Zhili cliques in total amounts of revenues explained at least in part their rough equivalence in military forces on the eve of the war between them in June 1920: 55,000 men on the Anhui side and 56,000 men on the Zhili side.Footnote 17 On the other hand, the Fengtian clique appeared to be much weaker, having only 26 million yuan as its total revenue. But the Anhui and Zhili cliques had their own weakness. Duan Qirui and Feng Guozhang, the respective leaders of the two cliques, had been Yuan's two most capable and trusted subordinates, but Duan and Feng had competed with each other while Yuan was alive. After Yuan died, Duan controlled the central government as the premier of the state council and much of North China through the military governors loyal to him; Feng, for his part, prevailed in South China by serving as the military governor of the most prosperous Jiangsu province and allying with other governors in the Yangzi River region while also serving as the vice president and the acting president of the Beijing government until October 1918. But the military governors of individual provinces formed a clique under Duan or under Feng (or Cao Kuan after Feng's death in late 1919) only on the basis of their personal relationship with either of the two clique leaders.Footnote 18 In other words, Duan or Feng (or Cao) built their respective factions only by taking advantage of their position as leaders of Beijing government to appoint or recommend their trusted followers or friends as the military governors to different provinces within their reach of power; when they had conflicts in appointing the governors, Duan and Feng had to bargain with each other to achieve a gross balance between the appointments that each of them had proposed.

Such personal networks and loyalty to the factional leaders did matter when the two factions had a war; for the military governors, to join the war was the best way to protect their own positions and military forces. Nevertheless, neither Duan nor Feng (and other Zhili leaders) had succeeded in turning the individual provinces of their respective cliques into a solid fiscal-military entity. Each of the military governors controlled their own armies and were responsible for raising enough monies to feed their soldiers; they also largely controlled the tax revenues generated within their own provinces, and generally refused to contribute any part of their revenues to the central government regardless of their personal loyalty to the clique leader who held a key position in the central government. Both the Anhui and Zhili cliques, in a word, were essentially a confederation of warlords who were loosely brought together by their personal loyalty to the clique leader; there was no centralized administrative or military mechanisms to keep them together as members of a political and military body with a high level of group solidarity. Later in 1926 and 1927, the Zhili clique lost their control of the provinces in the Yangzi River region precisely because the key leaders of the group in different provinces (most notably, Wu Peifu in Hubei and Sun Chuanfang in Jiangsu) failed to act together and help each other to fight their shared enemy, the Guomindang force from the south, and the latter had no difficulty in defeating each of them one after another.Footnote 19

The rise of the Fengtian clique

The lack of group solidarity on the part of the Anhui and Zhili groups was in sharp contrast to the centralized administrative and military organizations that undergirded the Fengtian clique in Manchuria. In fact, one of the reasons that prevented the Anhui or Zhili clique from building a centralized fiscal and military entity of their own had to do with the fact that the member provinces of these cliques were geographically scattered in different areas of the country and were interwoven with the member provinces of the opposite clique. This scatteredness not only exposed each province to military attacks from its enemy, but also prevented the member provinces of each clique from mobilizing their resources to build a centralized political and military body of their own.

The situation of the Fengtian clique was very different. Zhang Zuolin (1875–1928), the head of this clique, started building his power base with his control of the 27th division of the New Army that garrisoned Fengtian province after the Revolution of 1911, which enabled him to further seize the positions of the military governor and the provincial governor of Fengtian, and to create the new 29th division and take control of the 28th division of the army after 1916. After establishing his complete control of Fengtian, Zhang extended his reach into the neighbouring Heilongjiang province in 1917 by recommending Bao Guiqian, his relative by marriage, to be the new military governor of the province. Zhang himself also received Beijing government's appointment as the Inspecting Commissioner of the Three Northeastern Provinces (Dongshansheng xunyueshi) in 1918, which made him the official administrative and military ruler of the three provinces.Footnote 20 To the extent that Zhang controlled the neighbouring two provinces by appointing his trusted men as their military governors, he was no different from the leaders of the Anhui and Zhili cliques in building their respective factional groups. What made Zhang distinctive and successful in the end in the rivalry among the warlords under the Beijing government was that he took advantage of the geographical isolation of Manchuria to turn the three north-eastern provinces into an independent and highly centralized political, fiscal, and military entity.

To achieve this goal, Zhang first cut off the political ties of his three provinces with the Zhili-clique-controlled central government by declaring his independence from Beijing, after he lost the war against the Zhili clique in April 1922 and failed to expand his influence into the interior provinces. He further made efforts to modernize the administrative system in Manchuria by introducing the civil-service examination system in September 1922 to recruit government officials at different levels on the basis of their merits. Zhang also rebuilt his troops, replacing most of the lower- and middle-ranking military officers of bandit backgrounds with graduates from the military academies in Japan or Beijing; he also expanded the size of the Northeastern Military Academy to train his own military officers and held training sessions for high-school graduates to prepare them for military service. To root out the personal networks (mostly in the form of sworn brotherhood among the high-ranking military commanders) from the military, Zhang reorganized the three divisions (the 27th, 28th, and 29th) and an additional new division he had established into 27 infantry brigades and other units, and appointed his trusted subordinates to lead them.Footnote 21 The administrative and military unification in Manchuria meant a lot for the Fengtian clique: it prevented internal strife among the three provinces, ensured political stability and social order, freed Manchuria from the recurrent warfare that plagued the interior provinces, and enabled Zhang to mobilize the resources from all of the three provinces for his strategic goals.

To enlarge and maintain his military forces, Zhang generated revenues through several channels. In addition to the collection of land, industrial, and commercial taxes, the Fengtian clique made government investments on a large scale, which ranged from mining and lumbering to textile manufacturing, power generation, sugar production, the defence industry, and, most importantly, the construction of a railroad network. It also developed financial tools to generate additional revenues, such as the issuance of government bonds and the printing of paper notes, known as fengpiao, which were widely accepted and circulated in Manchuria because of its stable value from 1917 to early 1924.Footnote 22

The strength of the Fengtian clique, in a word, lay in its ability to integrate the three north-eastern provinces into a single administrative, fiscal, and military entity that was centralized under one single strongman. Individually, none of the three provinces was the most prosperous in the entire country. In 1925, for instance, Jiangsu province had a budgeted revenue of 16.6 million yuan, which was much higher than the revenue of Fengtian, the richest of the three north-eastern provinces; another two interior provinces, Sichuan and Guangdong, again had an annual revenue higher than or close to Fengtian's (see Table 2). But the problem for the warlord cliques who controlled a number of the interior provinces was that the fiscal resources in each of the provinces fell into the hands of the military governor who controlled that province; as a result, no clique leader was able to single-handedly control the resources from all of the provinces of his clique. In sharp contrast, by establishing his tight control over Manchuria, Zhang Zuolin was able to extract fiscal resources from all of the three provinces for his military build-up; combined, the annual revenues from the three provinces totalled 27.3 million yuan (Table 2), which was in addition to the revenues he generated through issuing public bonds and printing paper currencies. His fiscal power, in a word, surpassed that of any of the military governors of the interior provinces.

Table 2. Budgeted revenue and expenditure of individual provinces, 1925 (in silver yuan)

Source: Jia Shiyi 賈士毅 (1932), Minguo xu caizheng shi (1) 民國續財政史(一)[Supplement to the Fiscal History of the Republic of China], vol. 1, Shangwu yinshuguan, Shanghai, pp. 146–152.

The geographical isolation of Manchuria from the rest of China also contributed to Zhang's success in competing with the warlord cliques of the interior provinces. After establishing his control of the three north-eastern provinces, Zhang was able to join the rivalry among the warlords in North and East China and thereby to extend his military and political reach there. He started his military operations down to the interior when the warlord cliques there were fighting with each other. When he failed in this venture, he could easily withdraw from the interior while keeping his home base in Manchuria intact. He could then concentrate on building his fiscal and military muscle in Manchuria and wait for another chance to venture into the interior, ultimately succeeding after the interior warlords had exhausted their resources after years of battles. This geopolitical advantage, together with the difference between the Fengtian clique and the major cliques of the interior provinces (Anhui and later Zhili) in their respective fiscal constitutions, was more important than any other factors (political or military) in explaining why the Fengtian clique eventually won the rivalry among the northern warlords and came to dominate the Beijing government in October 1924.

Small provinces, powerful contenders

The Fengtian clique, in fact, was not the only case that took advantage of its geographical isolation to build a highly centralized fiscal and military entity and compete successfully with other cliques. Another example is Shanxi province, which was small in territory but strategically important in national politics throughout the Republican era. Located in north-west China, Shanxi was a plateau fenced by the Taihang Mountains in the east and the Yellow River in the south, while its northern border was backed with Gobi desert and its western border was lined with mountains. Historically, the province was known for being ‘easy to defend and difficult (for external enemies) to attack’ (yi shou nan gong). For the entire Republican period, it was under the consistent control of warlord Yan Xishan (1883–1960). Yan began his rule in Shanxi as its military governor right after the Revolution of 1911 and controlled all of the military forces within the province by 1917. Like all other warlords, Yan built his power base by vigorously expanding his army, which grew from merely 7,000 men before 1916 to roughly 100,000 around 1923; he thus became one of the few local strongmen in North China who had a nationwide influence.Footnote 23

Key to Yan's survival and longevity in Shanxi were his abilities to establish and maintain an efficient and highly centralized political and military system in the entire province, which made the province largely free of instability and warfare before the Japanese invasion. He filled the key positions in the military with his trusted followers, mostly originating from Wutai, his home county, or from Shanxi, to a larger extent. But he also paid attention to the merits of government and military officials and thus recruited qualified candidates regardless of their geographical origins; many of them were thus promoted from the rank and file to higher positions and owed a lifetime debt to Yan. A contemporary thus noted that ‘the military and administrative circles throughout Shanxi province look like a big family, with Mr. Yan as the patriarch and all of the cadres as his disciples’.Footnote 24 To put the rural area under his effective control, Yan promoted the so-called ‘village-based governance’ (cunben zhengzhi), by which the rural communities were reorganized into administrative villages (biancun), each consisting of roughly 300 houses, which were divided into a number of neighbourhoods or lü, with each lü further divided into five lin and each lin having five households. Leaders of these organizations shouldered the duties of policing local residents, collecting taxes and levies, and assisting the government to recruit soldiers. The goal of the village-based governance was the so-called ‘combining farming with warring’ (bing nong heyi) or militarizing the rural society in preparation for war.Footnote 25

Equally important for Yan's build-up of an independent administrative and military system in Shanxi was his effort to develop the local economy and ensure its sustainability and self-sufficiency. Part of his goals in rural Shanxi was the so-called ‘six measures’ (liu zheng, namely water control, tree planting, sericulture, a ban on opium smoking, a ban on foot-binding for women, and pigtail-cutting for men) and ‘three matters’ (san shi, namely cotton cultivation, foresting, and husbandry), which aimed to promote prosperity in the village communities.Footnote 26 His government invested massively in modern industry and transportation, which later formed the basis of the Northwestern Industrial Corporation—a conglomerate founded in the early 1930s that encompassed a wide range of enterprises, including mines, smelters, power plants, and factories producing machinery, chemicals, construction materials, textile and leather products, and consumer goods. But the most important and successful project was the famous Taiyuan Arsenal, which was one of the three major arsenals in China in the 1920s and 1930s (the other two were located in Hanyang of Hubei province and Shenyang of Fengtian province) and produced a wide variety of guns and canons and a large quality of ammunition.Footnote 27 Given his ability to mobilize the rural population and the capacity of his arsenal, Yan's army stood out as one of the three major forces in North China by the end of the 1920s, the other two being the forces under Zhang Zuolin and Feng Yuxiang, who will be described shortly.

The importance of geopolitical security and centralized control of territory for warlords’ survival and strengthening is also seen in yet another case in Guangxi province. Located in the south-western border of China and dominated by mountains, Guanxi was never a target for warlords in other parts of China to compete for, yet its remoteness and relative isolation also offered the necessary conditions for ambitious local strongmen to build their independent domain and use it as a power base to vie for national influence when they became strong enough. The first military strongman in Republican Guangxi was Lu Rongting (1859–1928), who ruled the province as its military governor right after 1911 for ten years and was later remembered by local people for his ability to weed out bandits and keep the land at peace. At the peak of his influence, Lu was able to defeat his rival in Guangdong in 1917 and dominated the neighbouring province for three years.Footnote 28 Although the limited resources from the poverty-stricken Guangxi constrained his military build-up and explain in large part—in addition to the fatal defection by a key commander of his army—his loss in confronting the newly rising forces in Guangdong, the new warlords who replaced him to rule Guangxi after 1924 turned out to be even more successful.

Unlike the warlords in other provinces who tended to fight each other for exclusive control of a given area, the new strongmen in Guangxi, namely Li Zongren (1891–1969), Bai Chongxi (1893–1966), and Huang Shaohong (1895–1966), proved to be exceptionally collaborative with one another in building a unitary political and military force. In fact, the limited territory and resources of Guangxi made it unaffordable for any of them to fight with each other; the best strategy for them to survive, therefore, was to work together as a single, unified entity.Footnote 29 Knowing well the limited revenues of the poor province that greatly curtailed their military potential, the New Guangxi clique adopted an approach to build their fiscal and military strength that was essentially no different from Yan Xishan's methods in Shanxi. Summarized as the ‘Three-Self Policies’ (san zi zhengce), this approach contained three goals. The first was ‘self-defence’ (ziwei) or military build-up. Lacking enough tax revenues to raise a sizeable standing army, they chose to militarize the society under the so-called ‘Three Build-in Policies’ (san yu zhengce), namely to build the military by establishing local militia throughout the province (yu bing yu tuan), to train military officers directly among school students (yu jiang yu xue), and to recruit soldiers directly from the registered male adults of the reorganized villages (yu zheng yu mu). Not surprisingly, after the outbreak of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937 that signalled the beginning of a full-scale war of resistance against Japan, Guangxi province turned out to be the fastest among all provinces in military mobilization; it recruited enough soldiers to create four army corps and 48 regiments in a matter of two months.Footnote 30 The second goal was ‘self-government’ (zizhi), which aimed to establish a clean and efficient government by purging corrupt officials, training qualified cadres, and, most importantly, restructuring the rural society under the baojia system, in which the head of a township or a village also served as the school principal and the militia leader at the same level. To achieve the third goal of ‘self-sufficiency’ (ziji), the Guangxi clique was committed to investing in a wide range of manufacturing, mining, and transportation projects, promoting compulsory and higher education, and developing forestry and agriculture.Footnote 31

Winners and losers

The success of the Fengtian, Shanxi, and Guangxi cliques, therefore, lay primarily in their fiscal strength; they used all kinds of methods to generate as much revenues as they could. In addition to the traditional methods of taxing the land and commercial goods, they all made systematic efforts to invest in a modern industry and transportation system, and they all utilized modern financial tools for additional incomes. But the sharp contrasts between Fengtian and the other two cliques in geographic and economic sizes meant that there were significant differences between them in their respective approaches to state- and military-building. The rapid development of modern industry and transportation and the large amount of industrial output in the vast area of Manchuria made it possible for the Fengtian clique to rely mainly on the taxes from commerce rather than the taxes on the land. As a result, its budgeted revenue from the taxes on goods and other non-agricultural sectors amounted to 19.6 million yuan in 1925, or more than 2.5 times its revenue from land taxation (Table 2). In sharp contrast, despite their efforts to industrialize, the economies in Shanxi and Guangxi remained largely agricultural. The revenue from goods and other non-agricultural sectors in Guangxi, therefore, was only about 73 per cent of its land taxes and, in Shanxi, only 23 per cent (Table 2). Even more striking was the contrast between them in the absolute amount of annual revenues. The three provinces of the Fengtian clique had a total of 27.3 million yuan in 1925, whereas the Shanxi clique had only about 7.3 million and the Guangxi clique had even less, at 4.1 million yuan (Table 2). All these, to be sure, were budgeted rather than actual figures, but they nevertheless suggest the gap between them. Not surprisingly, the Fengtian clique was able to spend more on its military, and its total budget in this regard amounted to more than 21 million yuan in 1925, which was roughly three times the military spending in Shanxi and Guangxi (Table 2). For the two smaller cliques, in the absence of sufficient funding on the military, a better, more cost-saving approach to military-building, therefore, was to militarize the society by reorganizing the rural population into strictly controlled units, widely establishing militia, and making them readily available for mobilization and recruitment.

In sharp contrast with the winners are the warlord cliques or provinces that failed because of their lack of the advantages that the former had. The first is warlord Feng Yuxiang (1882–1948), whose forces grew to more than 400,000 men and dominated large areas of North and Northwest China at the peak of his career in the late 1920s. Feng's biggest weakness, however, was his lack of a stable and solvent base area to support his army. He thus faced exceptional and constant difficulties in feeding his soldiers, despite the various efforts he tried, such as retaining the salt taxes, raising the rates of railroad shipment of cargos, and selling public bonds by force in its occupied areas.Footnote 32 The reason Feng was able to expand his forces and survive for more than a decade until the eventual collapse of his clique in 1930 had to do in part with his highly speculative strategies that led to his frequent defection, alliance, breakup, and realignment with other competing cliques, and in part with the generous support from the Soviet Union after 1925.Footnote 33 After the Soviet Union cut off its supplies, Feng's competitiveness quickly deteriorated. In addition to its fiscal insolvency, equally fatal to his clique was that Feng never made serious efforts to centralize his control of the various corps, divisions, and brigades that he had created, due to the scatteredness of their occupied areas where the individual forces had developed.Footnote 34

A second example that contrasted with the successful cliques is the warlords in Sichuan province. Sichuan, in fact, had the perfect conditions to support a powerful warlord able to compete nationally. Located in the south-west frontier, it is relatively isolated from other provinces by the mountains surrounding it, while the vast basin area within it was one of the most fertile in China, giving rise to a highly developed agriculture and a high density of population. Therefore, among all of the provinces in China, Sichuan had the largest area of cultivated land (151 million mu) and the largest population (47 million). The government's budgeted annual revenue in this province was consistently the second highest in the entire country, at around 12.5 million taels in the late 1910s and 1920s, only next to Jiangsu province (Table 2).Footnote 35 Precisely because it was so large in size and so important as a huge source of revenues and soldiers, however, warlords inside and outside the province competed for a piece of it, and no one was able to control the entire province alone. Thus, after years of rivalry and chaos following the Revolution of 1911, by 1918 and 1919, the province had become extremely fragmented as a result of the rise in the so-called ‘garrison-area system’ (fangqu zhi) in the province. Under this system, the province was divided into 15 or more garrison areas, each containing a number of counties (varying from nine or ten to as many as 33 counties), and the military force in each garrison area was responsible for supporting itself with the revenue from within the area. Most of the garrison areas in southern Sichuan and around the city of Chengdu fell into the hands of warlord forces from the neighbouring Yunnan and Guizhou provinces, while the rest of the garrison areas belonged to local Sichuan forces. Despite the existence of a provincial government, the warlord force of each garrison area turned the territory it occupied into an independent domain subject to its exclusive control by appointing its own government officials, collecting taxes, and retaining the revenues that should have been remitted to the provincial or central government.Footnote 36 To enlarge or protect their garrison areas, the warlord forces fought with each other year after year; therefore, military expenditure in Sichuan was also the highest in the entire country, reaching more than 26 million yuan in 1925, or more than twice its budgeted revenues for the same year (Table 2). The division and chaos in Sichuan persisted until 1935, when the province came under the unified control of the Nationalist government.Footnote 37 Before that point, the administrative and military fragmentation excluded the possibility of any warlord from Sichuan playing a role in national politics commensurate with its wealth and population.

Finally, let us look at Jiangsu, the richest province in imperial and Republican China. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, its budgeted revenue was more than 16 million yuan, well above all other provinces, and its real revenue was not too different from the budget, at about 15 million yuan a year, after maritime customs and salt taxes, totalling more than 20 million yuan, were diverted from the province.Footnote 38 But two factors prevented the province from becoming a powerful military contender in the country. The first was geopolitical. Located in the lower Yangzi region and dominated by plains, the province is open to all other provinces without any geographic barrier to separate and protect it. As the most prosperous area in China, it was the target for external warlords to complete for control; there was no single warlord who could rule Jiangsu for a prolonged time because of the fierce competitions among the warlords of different cliques for this area. A second factor that made warlords’ centralized control of Jiangsu difficult was the existence of a strong gentry-merchant class in this province and its resistance to the warlord's excessive extraction of revenues from the province through their control of the provincial assembly. Throughout the early Republican years to 1927, the warlords who ruled Jiangsu consistently paid particular attention to the public opinion of the local elites in order to maintain their legitimacy and yielded from time to time to the demand from the latter for ‘the separation of the military from the civilian’ (junmin fenzhi) and ‘government of Jiangsu by people of Jiangsu’ (Su ren zhi Su), which meant preventing the military governor from interfering with the administrative affairs in the province, especially the appointment of key positions of the provincial government, including the governor and financial department head, which they insisted should be filled by the natives of Jiangsu, rather than by the warlords’ men.Footnote 39 The strong resistance from the gentry-merchant class in Jiangsu greatly limited the room for the warlords to extract local resources and expand their forces; it also accounted for the fact that, despite its highest level of revenue among all provinces in China, the budgeted military spending was limited to only 3.9 million yuan or 23 per cent of its revenue in 1919 and 6.1 million yuan or 36 per cent of its revenue in 1925 (or 23 per cent of the military spending in Sichuan in the same year), whereas, in the country as a whole, military spending was 46 per cent and 105 per cent of government revenue in 1919 and 1925, respectively.Footnote 40

All these instances suggest that each of the three factors (namely geopolitical setting, socio-economic conditions, and fiscal-military organization) is indispensable for any regional force to build its competitive advantage. While stable and secured control of a given region served as the very precondition for long-term military build-up, socio-economic conditions of the region determined the nature and scope of economic and financial resources available for extraction. Whether or not such resources could be turned from potential into real competitive strength, however, ultimately depended on the regional force's ability to build a centralized and unified fiscal apparatus.

Why did the Nationalists win?

Now let us look at the situation in Guangdong—a southern province that was only next to Jiangsu in economic prosperity and government revenue. Until his death in March 1925, Sun Yat-sen, the Grand Marshall of the Military Government beginning in August 1917 and later the ‘extraordinary president’ of the Republic after April 1921 that ruled only Guangdong and Guangxi, struggled to build an army strong enough to eliminate the warlords and unify the country, but he failed repeatedly.Footnote 41 He never expected, and indeed no one else could anticipate, that, only a year after his death, the Nationalist Revolutionary Army's Northern Expedition started and, even more surprisingly, defeated the warlords in the middle and lower Yangzi regions in less than ten months, wiped out the Fengtian-clique forces from the interior provinces, and overthrew the Beijing government in June 1928. The unification of China, which Sun could only dream of, came true in December 1928 when Zhang Xueliang (1901–2001), the warlord of Manchuria, declared his allegiance to the newly established Nationalist government in Nanjing.

The Nationalist Army was unlike any of the warlord forces in that it emphasized ideological indoctrination among the soldiers and military officers at different levels under the control of the Nationalist Party, and hence known as the ‘party army’ (dangjun). It thus exhibited an unusual degree of solidarity and high morale when compared to the warlord forces.Footnote 42 But the role of nationalist propaganda in the Nationalists’ military-building should not be overemphasized. There were, in fact, significant continuities between the Beijing government and the Nationalist state in their commitments to nationalism and subsequent foreign policies.Footnote 43 The most important reason behind the Nationalists’ triumph over the warlords, as shown below, is its unparalleled fiscal strength, which was developed through three key steps. The first was, of course, the making of a solid fiscal-military state in Guangdong, which enabled the Guomindang force to launch the Northern Expedition and occupy most of South China and the middle and lower Yangzi regions in a few months. The second was its alliance with the financiers in Shanghai after occupying the city, which made it possible for the Guomindang force to dramatically increase its revenues by borrowing from the bankers and selling government bonds. The revenues thus generated fuelled the Guomindang's continuous Northern Expedition in North China, which finished in June 1928 when its troops occupied Beijing. The third step was its decision to restore China's autonomy in maritime customs in December 1928 after unifying the country, which quickly made maritime customs the most importance source of the central government's revenue (accounting for about 60 per cent of its total income in the late 1920s and early 1930s; see Table 1).

Guangdong and the Northern Expedition

The reasons behind Sun's frustrations lay partly in his reliance on warlord forces in the absence of a military force under his own control. He first sought support from the warlords of Guangxi, who, however, came to control the Military Government and turned Sun into a figurehead; later, he turned to warlord Chen Jiongming (1878–1933), who nevertheless firmly opposed Sun's idea of a Northern Expedition and only wanted to build his stronghold locally. Sun also attempted in late 1922 to ally with the Fengtian clique to attack Zhili clique, and later with Feng Yuxiang after Feng defeated warlord Wu Peifu in October 1924 and terminated the Zhili clique's control of the Beijing government. It was on his trip to Beijing at the invitation of Feng and other strongmen in seeking the unification of China that Sun died, leaving behind a will to remind his followers that ‘the revolution has not been successfully concluded’.Footnote 44

A more fundamental reason leading to Sun's failures, however, was the inability of his government to generate enough revenues before 1925, which in turn had to do with the fragmented political map of Guangdong in the early 1920s. When he came back to Guangzhou in February 1923 after defeating Chen Jiongming with the help of the Guangxi and Yunan armies, Sun found that the only place where his orders were effective was Guangzhou itself, and the rest of Guangdong remained in the hands of either Chen's forces or the troops from Yunnan, Guangxi, Hunan, or as far as Henan. As a result, his government only collected 4.6 million yuan in revenue in the first half of 1924 mostly by farming out tax collection to merchants. The financial ministers of his government stepped down one after another because of the huge difficulties in raising enough revenue.Footnote 45

A turning point in Sun's military build-up was the financial aid and military supplies that he received from the Soviet Russia after May 1923, which included a loan of 2 million rubles in 1924, various aids in the amount of 2.8 million rubles in 1925, and at least 2.84 million rubles in 1926.Footnote 46 The Soviet aid made it possible for Sun to establish the Whampoa Military Academy in May 1924 and to deploy his newly established forces, including students from the academy, for two ‘Eastern Expeditions’ in February and October 1925, respectively, which eventually subjugated the forces of Chen Jiongming and other local warlords and brought the entire province under the Nationalist government.

The two years following the unification of Guangdong saw the explosion of the Nationalist government's revenue. Its tax incomes in 1925, for example, increased from about 4 million yuan in the first half of the year to 12.2 million yuan in the second half, when the Nationalist government quickly expanded its control of the province, thus bringing its annual tax revenue in the entire year to more than 16 million yuan, which nearly doubled its 1924 level (8.6 million yuan). The growth of the Nationalist government's tax revenues in Guangdong was even more dramatic in the following two years, to 69 million yuan in 1926 and 122.6 million yuan in 1927, which was more than 14 times its 1924 level and 3.3 times Guangdong province's annual revenue (37.4 million taels) in the last years of the Qing.Footnote 47 Therefore, the province's unification alone cannot explain the skyrocketing of its revenue. More important to Guangdong's fiscal strength were the measures taken by Song Ziwen (Tse-ven Soong or T. V. Soong) (1894–1971), a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University, who began his service as the financial minister of the Nationalist government and the head of the financial department of Guangdong province in September 1925.Footnote 48 The measures he implemented fell into the following categories:

1 centralizing the collection and management of government revenues, such as

• taking over the power of tax collection from military forces in the localities they stationed,

• terminating the practice of farming out tax collection to merchants,

• prohibiting the retaining of tax monies by the military or any civilian institutions, and

• dispatching personnel to the newly occupied areas to establish local financial, offices directly answering to the provincial government;

2 bureaucratizing the tax collecting agencies, such as

• incorporating the preexisting separate institutions for collecting taxes on stamps, gambling, and opium prohibition into a unified system under the financial ministry,

• creating the statistics department within the ministry to enhance its accounting and auditing abilities,

• building a province-wide force against the smuggling of commodities, and

• most importantly, recruiting civil servants of the ministry through examinations to open to the public and punishing their involvement in corruption;

3 consolidating the major sources of tax revenues, such as

• reorganizing the channels for stamps sales, extending the collection of stamp taxes to alcohol and firecrackers, standardizing the use of stamps on all commodities (together, these measures brought the annual income from stamp taxes from 0.6 million to 3.04 million yuan in 1926),

• collecting a special tax on kerosene (which generated more than 2 million yuan in the second half of 1926),

• surveying and taxing the sand fields along the coast (which resulted in an increase by more than a million yuan annually),

• monopolizing the sales of opium through the prohibition of its smuggling (as a result, the six-month income from this source increased from 2 million yuan in 1925 to more than 9 million yuan next year),

• surveying and auditing the collection of lijin on all domestic commodities and increasing its collection rate by 20 percent in January 1926 and an additional 30 percent the next month (the annual revenue from this source along thus increased by 2 times to nearly 16 million yuan in 1926),

• collecting a ‘domestic tax’ on all goods at the rate of 2.5 percent on ordinary items and 5 percent on luxury items (which began in late 1926 and generated about five million yuan annually), and

• selling public bonds (totalling 24.28 million yuan by September 1926) instead of issuing extra amount of paper currency by the Central Bank to safeguard its creditability and avoid runaway price inflation.Footnote 49

This is an impressive list. Together, these measures produced a centralized, efficient bureaucracy able to fully tap into the financial resources of a province that was only next to Jiangsu in economic prosperity and even more developed in domestic and foreign trading than the latter. The results of these measures were surprising. In a matter of only two years since Song's tenure as the financial minister, Guangdong province's annual tax revenue, as noted earlier, multiplied to more than 122 million yuan by 1927, which made the Nationalist force the financially most solvent among all competing military forces throughout the country.

For years, the Fengtian clique had been the most affluent force, with an annual revenue of more than 27 million yuan from its three Manchurian provinces in the mid-1920s, which militarily made the clique the most competitive among all warlord forces. With no challengers in North China after defeating the Zhili clique, it came to control Beijing government in 1924. But the rise of the Nationalist force in Guangdong changed this situation. What backed the Nationalist force's meteoric rise was the building of a centralized and efficient fiscal machine engineered by Song Ziwen that mobilized the province's financial resources to its fullest extent.

Song's financial policies in Guangdong were exorbitant. The lijin and ‘miscellaneous taxes’, which accounted for the largest portion of the province's revenue, covered almost all kinds of goods and services at a collection rate unseen before. Li Zongren, who ruled Guangxi after 1925 and later joined the Northern Expedition, thus honestly described Song's measures in Guangdong as ‘draining the pond to catch all the fish’ (jiezeeryu) and ‘ruthless taxation and extortionate collection’ (hengzhengbaolian).Footnote 50 Nevertheless, Song's policies worked. The ample revenue they generated provided an indispensable fiscal base on which the Nationalist force started the Northern Expedition in June 1926 and succeeded swiftly on the battleground. According to Song Ziwen's report on the Nationalist government's fiscal condition during the year from October 1925 to September 1926, the total revenue of the Nationalist government in Guangdong reached 80.2 million yuan, and its expenditure also expanded to 78.3 million yuan, of which 61.3 million yuan (78.3 per cent) was spent on the military.Footnote 51 Until as late as November 1926, when the Nationalist force had fully occupied Hunan, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Hubei province, and were ready to march up to Henan province and down to the lower Yangzi region, Guangdong province was the only source from which the Nationalist force derived its revenue. And the monthly spending on the military and war increased by 7.3 million yuan as the Northern Expedition extended into Henan, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu provinces.Footnote 52 As Song proudly stated: ‘as the revolutionary base, Guangdong province alone shouldered the expenses of a countrywide revolution in China. The recent military campaigns across central China as well as the cost of Northern Expedition have all relied on Guangdong.’Footnote 53 The success of the Northern Expedition, to be sure, had to do with multiple factors, including the high morale and strict discipline of the Nationalist forces and popular support to them, as well as the collaboration of the forces from Guangxi and Feng Yuxiang's army from the north-west and, on the other hand, the lack of coordination among the warlords in the middle and lower Yangzi regions. But key to the Nationalist force's combat capabilities and triumph on the battleground were its quick expansion from 130,000 soldiers at the beginning of the expedition to 550,000 men by early 1927, the ample supply of weapons and ammunition for it, and generous stipends on its soldiersFootnote 54—all these would not happen without the unparalleled revenue from Guangdong province that sustained the Nationalist force until early 1927.

The plight of the Nationalist government in Wuhan

The Nationalist forces’ control of Hubei in late 1926 and, more importantly, their occupation of Shanghai in March 1927 changed the way the Northern Expedition was fuelled. Shortly after the relocation of the Nationalist government from Guangzhou to Wuhan in January 1927, Hubei replaced Guangdong as the primary source of its revenue. In the view of Financial Minister Song Ziwen, Guangdong had been ‘extremely vulnerable and completely exhausted’ (kongxu ji yi, luojue ju qiong) after supporting the Northern Expedition for a year; it was imperative, therefore, for other provinces that had come under the Nationalist government to share the financial burden with Guangdong.Footnote 55 With Guangdong no longer a viable major source of its revenue and other provinces reluctant to contribute their revenues to it before financial unification in the occupied areas, the Nationalist government in Wuhan had to rely on Hubei province as the major source of its tax incomes. Song tried some of the measures in Hubei that he had successfully done in Guangdong to maximize his government's revenues. Unfortunately, Hubei was very different. Having endured successive wars between different forces for more than a decade, the economy in the province was yet to recover from prolonged recession; thus, despite the same measures enforced in Hubei as in Guangdong, the Nationalist government in Wuhan was only able to collect about 19 million yuan from various taxes from September 1926 to September 1927, which was only about 34 per cent of the annual revenue that the Guangdong government had generated through taxation prior to September 1926.Footnote 56 As a result, the Wuhan government had to rely on issuing public bonds, borrowing from banks, and printing paper currency as the major sources of its revenue (accounting for 84.5 per cent of its total revenue during the same period).Footnote 57

Having not firmly controlled the province, however, the Nationalist government in Wuhan found it difficult to gain full collaboration from local business and financial elites. Its growing tension with the Nationalist force in Nanjing and the subsequent embargo by the latter only worsened its insolvency. The Wuhan government thus had to introduce the radical policy of freezing the outflow of cash from Wuhan and banning the use of currencies other than the paper notes it printed, which only alienated local business elites and caused runaway inflation and further economic recession.Footnote 58 Having lost its financial creditability, the Wuhan government found it increasingly difficult to raise funds through public borrowing or printing paper notes, and it would soon give up in its competition with both the warlords in North China and the Nationalist force in the lower Yangzi region.

Re-energizing the Northern Expedition

The schism between the left and right wings among the Nationalists started well before the Northern Expedition. By and large, the leftists assembled around Wang Jingwei (1883–1944), head of the Nationalist government in Guangdong after July 1925 and later the president of the Nationalist government in Wuhan after his trip from France in April 1927, who insisted on collaborating with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in his government and the military, while Chiang Kai-shek, the generalissimo of the Nationalist Army, led the rightist group that opposed the CCP's radicalism and the Guomindang's united front with it. The tension between the two sides mounted over the course of the Northern Expedition, especially after the occupation of Shanghai in March 1927, and developed into open confrontation between the Nationalist government in Wuhan and another Nationalist government started by Chiang in Nanjing on 18 April 1927, who ruthlessly purged the communists from the cities he controlled. Chiang eventually prevailed over the left-wing Nationalists, after a few months of power consolidation within the Guomindang in late 1927 that allowed him to resume his position as the generalissimo in January 1928 and to restart the Northern Expedition three months later.Footnote 59

The most important reason behind Chiang's rise as the new leader of the Nationalists and his success in competing with the left-wing opponents within the Guomindang and defeating the warlords in North China during the second phase of the Northern Expedition was his control of Shanghai and the lower Yangzi region, the most prosperous area of the country, which allowed him to take advantage of the abundance of financial resources in this area.

Chiang's personal background as a native of Zhejiang and his earlier career in 1920–21 as a broker for Shanghai Securities and Commodity Exchange run by Yu Qiaqing (1867–1945), once a leader of the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce, were key to his success in connecting himself to the financiers in Shanghai, who mostly originated from his home province. To collaborate with Chiang, Yu soon created the Shanghai Association of Commerce in March 1927 to replace the disorganized Shanghai Chamber of Commerce that had sided with warlord Sun Chuanfang and to show his open support for Chiang's Nationalist force. After his arrival in Shanghai, Chiang took action to purge the communists by arresting and killing hundreds of them. Two days after establishing the Nationalist government in Nanjing in April 1927, Chiang officially set up the Jiangsu and Shanghai Financial Committee, with ten of its 15 members appointed from the business and financial leaders in Shanghai and Jiangsu, and headed by Chen Guangfu (K. P. Chen, 1880–1976), president of Shanghai Banking Association, whose primary duty was to raise funds for the Nationalist government. In exchange, Chiang granted the committee complete authority in appointing and managing all of the financial institutions of the Nationalist government.Footnote 60 The committee's first action was to make a short-term loan of 3 million yuan and another loan of 3 million yuan for Chiang in April 1927.Footnote 61 A bigger step it took was to assist the Nationalist government in issuing 30 million yuan of government bonds in May 1927, to be guaranteed by the government's additional revenue in the future through an increase in maritime customs by 2.5 per cent)Footnote 62; to that end, another committee consisting of 14 members—mostly business leaders from Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai—was created to manage the funds raised through the bonds.Footnote 63 In October 1927, the Nationalist government issued another 24 million yuan of government bonds, again guaranteed by the government's revenue from increased maritime customs.Footnote 64

The sale of large amounts of government bonds, however, turned out to be a huge challenge to both Chiang and buyers. For Chiang, raising enough money in a timely manner through the sales of government bonds was ‘where the lifeblood of all the affairs of the army, the government, and the party lie’. So desperate was his need for funds for the newly established government in Nanjing and the consolidation of his military control in Jiangsu and Zhejiang that he pleaded for help in his letter to Chen Guangfu in May 1927 with these words: ‘the life and death of the party and the state, as well as the glory and shame of the nation, all depend on this [the sales of government bonds].’Footnote 65 The bankers and business owners, for their part, tried to reduce or delay under various excuses their purchase of the bonds that had been apportioned among them. Chiang, therefore, repeatedly turned to compulsory measures. For instance, to compel the Shanghai branch of the Bank of China to advance 10 million yuan to satisfy the urgent needs of military spending when the sales of the bonds proceeded slowly, Chiang threatened the branch's manager, who had financed the Nationalist government in Wuhan, with the accusation of ‘blockading the revolution’ (zuai gemeng) and ‘intending to side with the rebels’ (youyi funi).Footnote 66 He ordered the arrest of the businessmen or their family members and the confiscation of their properties under the excuse of their counter-revolutionary activities in assisting warlords before, when the latter failed to buy the required amount of bonds.Footnote 67 Such threats and compulsions could be temporarily effective in obtaining the funds he wanted, but could not be counted on as a regular means to generate the needed money. Therefore, the sales of another 40 million yuan of bonds in October 1927 was exceptionally sluggish when the purchase of them was intended to be voluntary. Trapped in his prolonged confrontation with the Nationalist government in Wuhan, his defeat by the northern warlord force in Xuzhou, and the retreat of the Nationalist Army back to the south of the Yangzi River, Chiang stepped down from his generalissimo position in August 1927, to allow time for a reconciliation between Wuhan and Nanjing and for his own rebuilding of personal connections with financial leaders in Shanghai.Footnote 68

As anticipated, Chiang came back to power in January 1928 when he faced a new situation: the Nationalist government in Wuhan had been relocated to Nanjing to join the Nationalist government there, Chiang himself had married Soong Meiling in December 1927 and thus became Song Ziwen's brother-in-law, and, most importantly, Song Ziwen had accepted the position of the Minister of Finance in the Nanjing government right before Chiang's resumption of the generalissimo position. With Song's help, the Nanjing government's fiscal situation quickly improved in 1928. In a matter of six months after he became the financial minister of the Nanjing government, Song raised a total of 190 million yuan (!) through bank loans, sales of government bonds, and taxation.Footnote 69 This generous funding made it possible for Chiang to restart the Northern Expedition and launch a full-scale campaign against the Fengtian-clique forces in the northern provinces in April 1928. During the height of the war, Song was required to provide 1.6 million yuan every five days. He did the job and, in fact, generated much more than the required amount.Footnote 70

The Northern Expedition culminated in the Nationalist force's occupation of Beijing in June. The Nationalist government in Nanjing thus formally declared the unification of China on 15 June 1928. This, however, reflected more of the Nationalists’ political determination than the reality in the country, because the Fengtian clique, who had withdrawn from Beijing, still controlled the three north-eastern provinces. To march into the vast area of Manchuria and defeat the military forces of the Fengtian clique would be the most challenging task for the Nationalists. Fortunately, after Zhang Zuolin, who had resisted the Japanese pressure for further control of Manchuria, died of an explosion planned by the Japanese Kwantung Army on 4 June 1928, his son Zhang Xueliang, as the new leader of the Fengtian clique, accepted the leadership of the Nanjing government on 29 December 1928 and thus made all of the Chinese provinces officially unified.Footnote 71

China as a latecomer: from regional to national in state-making

To sum up, what propelled the rise of regional fiscal-military states in Republican China was the dynamics of centralized regionalism. It originated from regionalized centralism of the late-Qing period; one can easily identify the various direct or indirect links between the regionalization of military, fiscal, and administrative power after the 1850s on the one hand and the rise of provincial strongmen and warlord cliques in the early Republican years on the other. However, the centralized regionalism of the early Republican era was essentially different from the regionalized centralism of the late-Qing decades. First, the regional powers of the early Republican years were highly independent of the central government's military, fiscal, and even administrative systems, and their independence was often openly justified; the military strongmen of different regions used the rhetoric or concepts they invented to legitimize the various civil and military programmes in areas under their exclusive control, unlike the provincial governors or governors general of the late-Qing period who had to keep their informal or non-statutory practices in generating and spending extra revenues in a hidden or disguised manner, and whose regionalized measures usually appeared as expedient solutions to the crises that confronted them.

Second, and more importantly, the relationship between the central government and regional forces in early Republican years was fundamentally different from that in the late-Qing period. Under regionalized centralism, the Qing court, though unable to put regional resources and civil or military positions (especially those of the newly created institutions) under its complete control, effectively dominated individual provinces by making or revoking appointments to key positions at the provincial level. It also had the ultimate power to reallocate the revenues generated and officially reported by provincial authorities and, most importantly, to deploy all of the military units stationed throughout the country—a situation that remained true until the last years of the Qing. The provincial civil and military leaders could only exercise their discretion and autonomy within the scope allowed by the centre; by no means could they openly challenge the authority and legality of the imperial court. Centralism, in a word, was the most defining characteristic of the relationship between the central and regional authorities in the late-Qing period; regional autonomy existed and functioned within, rather than outside, the framework of a highly centralized government system.

In sharp contrast, the regional strongmen and warlord leaders of the early Republican years had complete control of the military and fiscal resources as well as the administrative system within the areas they occupied. Instead of submitting to the authority of the central government, they often openly challenged the latter and even used violence to oust their opponents from the top positions of the government; they were essentially a force of regionalism in nature.

Finally, and most importantly, late-Qing regionalized centralism, while allowing the dynasty to survive domestic turmoil and foreign intrusions and even witness a three-decade restoration, also undermined the central government's control of regional resources and institutions; once the Han elites who generated and managed such resources lost their allegiance to the imperial house, the latter would become extremely fragile, as seen in the last few months of the Qing when the provincial authorities declared their independence from the imperial court one after another. The regional leaders of the early Republic, for their part, did not seek the independence of their provinces from the central government, despite their defiance of the authority of both Beijing before 1927 or Nanjing afterwards. Quite the reverse—whenever a warlord launched a military campaign against his enemy, his excuse was precisely to defend China's political unity and national interests or to maintain peace and order in the country.Footnote 72 As a matter of fact, national unification was not merely a rhetoric disguising the warlords’ abuse of violence for self-aggrandizement; to engage in war and defeat their competitors was also the best way for the most ambitious warlords to survive the competition and strengthen themselves.

To make sense of the Chinese path to modern nation state, let us put it in the larger context of state-making in world history. By and large, we can distinguish between two different paths to the rise of a centralized and unified national state. One is found among the first-comers, such as England, France, and some other West and Northwestern European states. These countries first achieved the goal of expanding and consolidating their territories from as early as the tenth to the thirteenth centuries through conquest and thereby formed a centralized national monarchy; in the following centuries, they further consolidated state power by turning the monarch's indirect rule of the country into direct rule—that is, to eliminate the autonomy of intermediary forces such as priests, landed aristocrats, urban oligarchs, or privileged warriors while establishing a standing army to replace the mercenaries and enlarging the government bureaucracy to enhance its abilities of tax extraction and hence military build-up. The other path prevailed among the latecomers to the modern national states, such as Germany and Italy, as well as the Asian states that survived Western colonialism in the nineteenth century. The biggest challenge for these countries in the course of modern state-making was the existence of multiple regional states in a fragmented territory and the predominance of, or direct occupation by, foreign power over parts of their territories. State-making for the latecomers, therefore, meant first of all eliminating foreign dominance and building the territorial foundation for a future, unified state. Thus, instead of the penetration of a national state down to the regional level as seen among the first-comers, here state-making typically unfolded from the regional to the national level, beginning with the competition among regional fiscal-military states, each of which aimed to centralize state power and modernize the military, and culminating in the rise of the most powerful regional state that established its national dominance after defeating all other regional competitors and/or recovering its territory from foreign occupation. By accident, both Germany and Italy finished the task of territorial unification in 1871; in the same year, all of the regional daimyos in Japan returned their territories to the newly established central government. For the latecomers, the regional powers (Prussia for Germany, Piedmont for Italy, and Satsuma-Choshu for Japan) played the most decisive role in the making of a modern national state.

By and large, China took the bottom-up path of state-making, but it was different from other latecomers in at least three ways. First, it was huge geographically, which meant that there were necessarily more domestic competitors for national hegemony than in any other countries of small size; defeating the rivals and achieving the goals of national unification and power centralization was more difficult for the Chinese state-makers. Second, China was confronted with a geopolitical environment that was much harsher than that of the other latecomers, because of the threats from foreign powers that all appeared to be stronger and wealthier than China and, in particular, because of the existence of a militarily aggressive neighbour (Japan) that turned out to be the biggest barrier to China's quest for a centralized, unitary state. Third, unlike Germany or Italy, which had built a strong and centralized regional state before they embarked on the course of territorial expansion and national unification, the regional states in early Republican China, for all their efforts in military build-up, economic reconstruction, and power consolidation at home, remained in the rudimentary stage of state-making; there was still a long way for each of them to go before building a strong economy, an efficient bureaucracy, and a powerful military machine. For the Guomindang state that established its national dominance in the late 1920s, how to consolidate its rule and turn China into a truly unified and centralized nation state remained the most challenging task in the decades to come.