Introduction

Never in its existence did the Qing legation in London attract more criticism than in the fiasco in October 1896, when Counsellor Halliday Macartney detained Sun Yat-sen, a fugitive who had planned an insurrection in Canton in 1895, on legation grounds for deportation back to China.Footnote 1 How the story unravelled is well known: Sun gained the sympathy of an English servant, who delivered a message to his mentor, Dr James Cantlie. He was eventually released when the British government applied diplomatic pressure to the legation. The publication of Sun's sensational narrative Kidnapped in London upon his release instantly captured the British imagination and solidified the image of the Qing's London legation as ‘an embodiment of retrograde orientalism’.Footnote 2

Many have followed Sun's cue and seen the legation's actions as an all-too familiar sign of Oriental despotism and the political backwardness of the Qing, but Sun's detention was not a uniquely ‘Oriental’ practice unknown to the republican and democratic countries of the Western world. The last decades of the nineteenth century saw a concerted effort by nation states to control their borders, regulate immigrants, and extend jurisdictions beyond their national boundaries, whether by legal means or the exercise of irregular justice.Footnote 3 For example, in 1886, the American government resorted to forcible extraterritorial abduction to bring a fugitive in Peru to justice—an act against which the US Supreme Court raised no objection.Footnote 4 The Qing legation's actions did not appear obviously unlawful to judges and jurists of the time, and a number of critical details about the case had to be rewritten for the court of law to deem it an illegal act.Footnote 5

Far from a sign of ‘Oriental despotism’, the legation's detention of Sun exemplifies the legal activism of Qing diplomats on the international stage and shows that Qing legations assumed the role of recovering judicial sovereignty that had been compromised by the presence of extraterritoriality and colonialism.Footnote 6 This is underscored by the fact that the diplomats who tracked down Sun's movements in Washington, DC and London were also responsible for governing, policing, and protecting overseas and transborder populations.Footnote 7 The Qing's London legation began to redress China's loss of sovereignty at its inception in 1876 and its members negotiated for the extradition of Chinese fugitives from British colonies in half a dozen cases in the next two decades. Indeed, extradition was just one of several diplomatic tasks that the legation undertook to further China's sovereignty within the rubrics of treaties and international law.

This article proposes a historiographical intervention in our understanding of the Qing's engagement with international law by analysing an important and oft-neglected overseas office: the London legation. Only a decade ago, the scholarship on Qing diplomacy was still dominated by studies on the origins and development of the domestic Zongli Yamen, the Qing's central office in charge of foreign affairs in Beijing.Footnote 8 In the last few years, there has been a growing body of literature on overseas Qing diplomats’ role in treaty negotiations, protection of overseas Chinese, cultural diplomacy, and intelligence gathering.Footnote 9 But most of the existing works have centred on the performance of individual diplomats and the bureaucratic conventions of their selections and promotions; no study has focused on the legal and diplomatic functions of the legations. Compared to the rich body of recent scholarship on the mediating roles of Europeans in Asia, the way in which Qing legations mediated between the Zongli Yamen and foreign ministries to assert the Qing's interests has remained poorly understood.Footnote 10 Legations and overseas diplomats turn up at specific historical moments, such as the Margary Affair, the Sino-French War, and the detention of Sun Yat-sen, but their work has more often been understood in the contingency of the moment, and their institutional roles have often been acknowledged rather than explained.

In this article, I examine how Qing legations represented the Qing dynasty in its London legation from its inception in 1876 to the Boxer Protocol of 1901, and argue that overseas legations and their diplomatic representation abroad were essential to the construction and imagination of China as a sovereign state. The Qing's London legation did not merely provide ancillary support to the Zongli Yamen; it constituted a site where the Qing empire's legal status and sovereign claims were upheld by Anglo-Chinese diplomats—men who worked in concert with their domestic colleagues and their counterparts stationed in other foreign cities and capitals. Ultimately, I argue that the legation helped to create and disseminate a new way of understanding ‘China’ as a legal entity independent from the imperial dynasty.

Methodologically, my analysis differs from a narrative dominated by the political negotiations of great men or the agencies they headed. The last three decades have witnessed the field of diplomatic history reinventing itself as ‘international history’, as historians have increasingly paid attention to what Akira Iriye has termed ‘the sharing and transmission of memory, ideology, emotions, life-styles, scholarly and artistic works, and other symbols’.Footnote 11 To show just how short-sighted G. M. Young was when he wrote ‘what passes for diplomatic history is little more than the record of what one clerk said to another clerk’, this new body of scholarship shows that the cultural context also mattered—the ‘where, when, and how the two clerks corresponded’ and the broader changes in diplomatic communication.Footnote 12 Recent scholarship on international law has also challenged the assumption that it was of purely Western origin and recovered the agency of non-Western actors in appropriating and interpreting international law to reclaim their own sovereignty and resist foreign domination.Footnote 13 Instead of assuming that states had fixed cultural modes that dictated their approaches to diplomatic engagements, these new works seek to globalize the history of international law and examine the changing meanings embedded in the form and protocol of diplomatic representation.

Most of these new studies, however, have been written by historians of Europe, the Americas, and Japan. Studies of late Qing engagement with international law have mostly stayed within a developmental framework and emphasized the Qing's reluctant coming to terms with international law and shedding its traditional identities. For example, Maria Adele Carrai has recently characterized late Qing reformers and statesmen as ‘still embedded in the traditional worldview’, using international law ‘temporarily in order to deal with foreigners, but [believing] soon the natural order of things would be restored’.Footnote 14 This study of the Qing legation—its diplomatic communication and representation of China in international law—seeks to use diplomatic archives to demonstrate that the Qing's engagement with international law was more than superficial and perfunctory.

I structure my analysis in four parts: first, I examine the institutional status of the legation as a mediator and collaborator between the Qing's central government and the British Foreign Office. Crucial to the legation's performance was its physical proximity to the British Foreign Office and its ability to render the Qing government's claims into a standard diplomatic form written directly in English. In the second part, I offer an analysis of how the Qing legation worked in tandem with the Zongli Yamen and provincial officials to resolve legal, judicial, and political conundrums that had met a dead end between domestic Chinese officials and foreign diplomats. This is demonstrated in how the legation led the way in establishing a Chinese consulate general in Singapore—a goal that had long eluded the Zongli Yamen: by reframing the Qing's security and political concerns into a claim for China's treaty rights as guaranteed in international law.

In the third and fourth sections of this article, I use two case studies, drawn from 1881–85 and 1900–01, respectively, to demonstrate how the London legation upheld China's sovereignty abroad. The first case study centres on the legation's mediation in the extradition of 13 Cantonese fugitives who had fled to Hong Kong. This case serves as an important precedent for contextualizing how the legation understood its action when its members detained Sun Yat-sen in 1896—as a rectification of China's exclusion from the international extradition regime. The second case examines how the legation worked at mediating between provincial officials and the British Foreign Office during the Boxer Uprising of 1900 to bypass the anti-foreign court and reach a rapprochement. It shows that the London legation provided the physical condition enabling alternative channels of communications; it was through these overseas channels of communication that a new construct of China as a legal entity independent from the Qing dynasty emerged in diplomatic documents.

In sum, the article uncovers how the Qing's London legation represented a broad range of interests of China through diplomatic negotiations and legal mediation. The diplomats of the London legation used international law to project the Qing as a legitimate member of the family of nations. In this process, the concept of ‘China’ became separated from the Manchu dynasty, and gained coherence and continuity.Footnote 15

The legation as mediator and collaborator

Qing legations stood in an ambiguous relationship with the Zongli Yamen. In many ways, they were functionally and administratively subordinate to it—after all, the latter was responsible for the legations’ creation, maintenance, and regulation. But legations also existed on the same institutional footing as the Zongli Yamen. Whereas the Zongli Yamen was charged with handling diplomatic affairs from within China, legations were conceptualized as parallel outposts beyond the Qing's frontier and both were directly beholden to the ultimate authority of the imperial throne. In the Zongli Yamen's original 12-point guidelines on the organization of the legations, a great deal of discretion was granted to the ministers to appoint the secretaries, counsellors, interpreters, and other secretarial staff of the legation.Footnote 16 Whenever important matters arose in their diplomatic dealings, legation ministers memorialized the throne promptly. Although they were not required to report all matters to the Zongli Yamen, legation ministers worked closely with Yamen ministers to coordinate their responses to foreign diplomatic institutions.

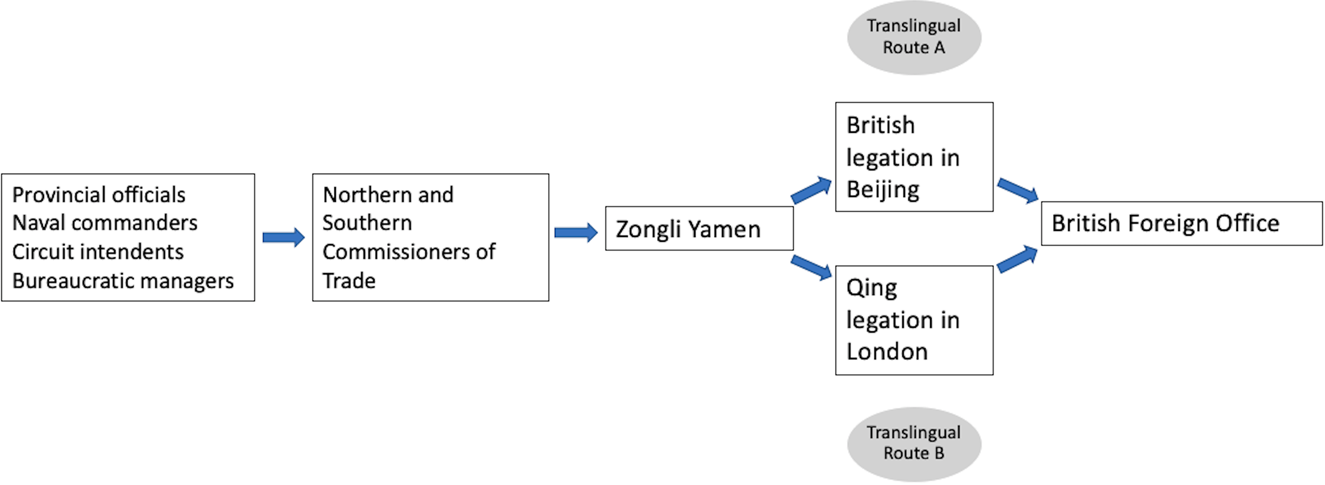

The communication routes between the Zongli Yamen, the London legation, and the British Foreign Office offer a particularly illuminating example of the mediating role played by the Qing legations. Figure 1 shows two official communication routes between China and Britain (Route A: Zongli Yamen—British Minister in Beijing—British Foreign Office; Route B: Zongli Yamen—Qing legation in London—British Foreign Office).

Figure 1. Two communication routes (A and B) between the Zongli Yamen and the British Foreign Office.

These two routes of communication transmitted diplomatic notes following different translingual paths. In Route A, the Zongli Yamen's Chinese letters (or verbal exchanges with foreign ministers in the Yamen) were translated into English by the Chinese-language secretaries of the British legation in Beijing based on their understanding of the Chinese language.Footnote 17 The translation was usually handled by British interpreters who had spent some years training in the Chinese language. Because of their richness and accessibility, this body of sources has been the most well-known primary source for the study of Sino-Western diplomatic history.

The textual representations of the Zongli Yamen (and other Qing officials) produced through British translators (via Route A) deserve critical scrutiny in light of what Antony Anghie has termed ‘dynamic of difference’ in colonial confrontations—‘the endless process of creating a gap between two cultures, demarcating one as “universal” and civilized and the other as “particular and uncivilized, and seeking to bridge the gap by developing techniques to normalize the aberrant society”’.Footnote 18 With respect to British colonial encounters with China, historians have shown how the ‘dynamic of difference’ animated representations of China in British intelligence reports and legal correspondence.Footnote 19 In his study of Euro-American discourse on Chinese law, historian Teemu Ruskola calls attention to Western representation of Chinese law as ‘essentially particular, in contrast to the universal qualities of “real” law’ and how this view became ‘the ground for a series of exclusions from the universal order of legal modernity’.Footnote 20 Historian Li Chen has similarly characterized British diplomats’ understanding of the Chinese legal texts as the ‘collective imperial knowledge that conditioned the modern image of China’.Footnote 21 Often frustrated with their encounter with Chinese officials, British diplomats wrote reports and dispatches that highlighted their view of the incompatibility of the two legal systems and the idiosyncratic character of the Chinese judicial system.

In Route B, the Qing legation in London, rather than the British diplomats in Beijing, became the mediator between the Zongli Yamen and the Foreign Office. This translingual route turned that imperial logic of exclusion on its head by directly rendering the Chinese government's intentions into legal claims grounded in international law. In the London legation's first 30 years, this task was most often performed by Halliday Macartney, the legation's English secretary in close consultation with his superior, the Qing minister to England.Footnote 22 The legation saw the Qing empire as a sovereign state deserving the full range of rights guaranteed under international law, with the exception of particular compromises provided in treaties that the throne had specifically agreed upon. They adopted a positivist legal discourse grounded in law and evidence-based reasoning in negotiation with the Foreign Office. This style of reasoning, according to Arnulf Becker Lorca, was not unique to China, but a ‘common professional style or legal consciousness’ shared among many non-European jurists and diplomats of the late nineteenth century.Footnote 23 A precise interpretation of the Qing's treaty rights, along with foreign countries’ obligations to the Qing under the treaties, became the legation's most effective weapon to combat the exclusion of China from the universal order under international law.

How this process worked is best illustrated by a case in 1884, when the German minister Max Von Brandt attempted to call on all foreign ministers in China to collectively demand the rights for treaty powers to set up manufactories in treaty ports. In response to their demand, the London legation presented the British Foreign Office with a memorandum on the Qing government's views on the matter. The memorandum not only provided a semantic interpretation of the relevant language in the Treaty of Tianjin in defence of the Qing's position; it also examined all pertinent clauses in the treaty and demonstrated that it was never the intention of their original framers to permit foreign manufacturers in treaty ports: ‘Neither in the Treaties themselves, nor in the negotiations which led to them, is there the slightest proof that such an eventuality as the opening of manufacturing establishments in the Concessions was ever contemplated.’ The memorandum pointed out, for example, that the treaty made ‘no provision for the Factories being supplied with raw material, but actually contained stipulations which would have the effect of preventing it from being procured’. In addition, the treaty gave specific permission to the kinds of establishments foreigners could build, rent, or construct, and yet nowhere did it permit manufacturing establishments. It concluded with a declaration of China's sovereign rights:

As China has never abandoned her sovereign rights with regard to manufacture, to her still pertains the right of either according or refusing permission to open manufacturing establishments in the Foreign Settlements, and further that whatever factories the Imperial Government may have permitted, or may yet permit to be opened by Foreigners at the Treaty Ports, must be taken as concessions due to considerations of expediency and political economy, and not as the recognition of any right acquired by them in virtue of the Treaties.Footnote 24

As usual, the legation provided both the Chinese and English copies of this communication to the Foreign Office. In his cover letter to the Foreign Office, Qing minister Zeng Jize claimed that the memorandum was drafted by the Zongli Yamen and then forwarded to him to be transmitted. A comparison between the Chinese and English versions, however, reveals that the English letter was produced first and the Chinese second. The content of the Chinese text was much shorter, strictly derivative of the English text, and adopted so many neologisms and novel arrangements of terms that many parts were nearly ungrammatical in Chinese. When we consider the fact that no trace of this letter can be found in the Chinese archives or in any of the personal collections of the Zongli Yamen officials or provincial officials, it seems even more probable that the legation took on the responsibility of framing the Zongli Yamen's objections to the German minister's demands, drafting its response in English, and presenting the Chinese translation as if it had originally come from the Zongli Yamen.

This contrast between the textual representations of the Zongli Yamen and the London legation cannot be attributed entirely to the different persons occupying domestic and foreign positions, but must be understood in light of their different communication processes and translingual practices. It is well known that the Treaty of Tianjin specified that ‘in the event of there being any difference of meaning between the English and Chinese text, the English Government will hold the sense as expressed in the English text to be the correct sense’.Footnote 25 The Zongli Yamen, the Qing's central diplomatic office, was staffed by classically trained ministers who held regular meetings and exchanged correspondence with the British diplomats stationed in Beijing. These Zongli Yamen ministers were assisted by zhangjing (secretarial staff) with specialized knowledge in treaties but, since none of them was fluent in English, the office was unable to fully articulate their ideas when disagreements with foreign diplomats arose.Footnote 26 This incapacity of the Zongli Yamen to produce English translations of their communications undermined their ability to control how their claims were represented to the British Foreign Office: all communications were translated by their diplomatic opponents: the British diplomats stationed in Beijing.

In contrast, the Qing's London legation was supported by a bilingual staff conversant in international law and it issued documents directly in English (the production of the Chinese versions came second). Furthermore, its location at 49 Portland Place, less than three miles from Whitehall, gave its diplomats immediate access to the flow of foreign policy elite, lawyers, and officials whose opinions on current affairs often influenced British foreign policy.Footnote 27 Through the mediation of Halliday Macartney, the Qing legation was brought into the interests and concerns that made up what T. G. Otte calls the ‘British Foreign Office Mind’.Footnote 28

The diplomatic representation by the legation can be seen as a special case of collaboration between imperialist powers and non-Western local agents—a theory first proposed by Ronald Robinson and later developed by Jürgen Osterhammel in the context of ‘informal empires’.Footnote 29 More recently, Anne Reinhardt has refined the theory in the context of steam navigation of the late Qing that ‘collaborative mechanisms could support the exercise of indigenous sovereignty and agency, but always within the unequal framework of the mechanism’.Footnote 30 The collaboration between the Qing minister, the English secretary, and the Chinese interpreters can be understood within this framework: by mediating diplomatic communications between two languages and two distinct bureaucratic and legal conventions, they essentially ‘perform[ed] one set of functions in the external or “modern sector” yet “square[d]” them with another and more crucial set in the indigenous society’.Footnote 31 Instead of identifying the legation as an isolated agent of mediation, it might be more useful to think of the legation as what Hans Van de ven has called ‘a nodal point in a network of transnational elites’ between foreign powers and Chinese society.Footnote 32 If we see Robert Hart and Gustav Detring as the mediators between Chinese officials and Western diplomats in China, as Van de ven has demonstrated, then the legation accomplished a similar function abroad of paving a channel of communication between the British Foreign Office and the Zongli Yamen. This ‘squaring’ function of the legation, as we shall see next, was achieved by the intimate collaboration between the legation's Chinese and English staff on the one hand and between the minister of the legation (usually a classically trained scholar-official of high ranking) and the Zongli Yamen on the other.

The London legation's diplomatic representation

Generally, the Qing's London legation issued diplomatic communications on several conditions: (1) upon a request from the Zongli Yamen, the Commissioners of Trade of Northern and Southern Ports, or the provincial civil or military authority to approach the Foreign Office on diplomatic issues that could not be resolved in China; (2) on the minister's own initiative, when he saw an opportunity to advance an agenda or when he encountered rumours about impending policies inimical to China's interests; (3) in response to a query made by the British Foreign Office to clarify certain positions of the Qing court or to seek further answers from other branches of the government; and (4) in response to a direct petition from Qing subjects overseas.

Even though the legation's letters were drafted by Macartney and followed European diplomatic and legal usage, their content was determined in close consultation with the Qing minister who presided over the legation, who in turn was in frequent communication with the Zongli Yamen, provincial officials, and Robert Hart, the inspector general of the Maritime Customs. After minister Zeng Jize assumed leadership of the legation in 1879, the London legation routinely used the telegraph to communicate with the Zongli Yamen and began to tackle negotiations that required timely exchanges of opinions with the British Foreign Office.Footnote 33 As a result, from 1879 onward, the London legation began to take a lead in resolving standing diplomatic conundrums that had met a dead end in China, such as treaty negotiations, the extradition of criminals from Hong Kong, and border demarcation between China and Burma.Footnote 34

In all these cases, the legation occupied a unique node where information from a wide range of institutional sources was gathered, synthesized, and represented in a legal language intelligible to the British Foreign Office. This process can be illustrated by how the legation finally secured the Foreign Office's support in 1890 to establish a consulate general for the Straits Settlements despite resistance from the colonial government. From the 1870s onwards, the Qing had become interested in offering diplomatic protection to and collecting information on overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, but their requests for new consulates beyond Singapore were persistently rebuffed. During the Sino-French War of 1884–85, Zhang Zhidong, the governor general of Liangguang, dispatched a commission to investigate the state of Chinese communities throughout Southeast Asia. Their report convinced Zhang that a general consulate overseeing branches in all islands—not just in Singapore—was necessary to protect the diverse Chinese interests in the region and consolidate their support for the Qing.Footnote 35 This was echoed by another petition that came from Ding Ruchang, commander of the Beiyang Navy, who sailed around the Straits Settlements on his fleet of cruisers in the winter of 1889.Footnote 36 Ding's superior, Li Hongzhang, consulted the Zongli Yamen on the matter and the latter issued a request to Xue Fucheng, the minister of the London legation, to formally bring up the request with the British Foreign Office.

Xue Fucheng searched the legation's archives and discovered that the British Foreign Office had refused similar requests made by his predecessors.Footnote 37 His letter to the Foreign Office (drafted in English by Macartney) called attention to the ‘anomaly’ that, despite China's openness to foreign residents, commerce, and consuls, Singapore was the only place where the Chinese government had a consul in a British dominion. In anticipation of the Foreign Office's objection, as they did before, on the basis of China's self-imposed exclusion from the ‘Comity of Nations’, Xue's letter pointed out that China had allowed, in more than 20 ports and places, foreigners to ‘reside and carry on Commerce on condition which, as compared to what takes place in the territories of many of the Treaty Powers, may almost be considered Free Trade’. To forestall the colonial government's objection, Xue framed the matter as a principle of sovereign rights and promised that China ‘would not take advantage of it to any great extent at present’.Footnote 38 In this way, the legation represented the Qing's political and security concern into a sovereign claim in adherence to international law.

Under what circumstances did the Zongli Yamen outsource an issue to the legation rather than tackling it domestically with foreign resident diplomats in Beijing? Both timing and the nature of the affair played into how diplomatic duties were partitioned and delegated. It seems to be the case that communication route A (through a British Minister in Beijing) was the more common path for matters with significant political impact, especially those with a perceived negative outcome for China. Therefore, this domestic route transmitted the vast number of diplomatic negotiations where the Qing government took a defensive position in response to claims advanced by foreign diplomats stationed in China. In contrast, the Qing's London legation took over cases in which the Chinese government asserted its positive rights, such as when they believed that their treaty rights were being violated by British subjects or diplomats in China, or when British representatives in Beijing were being uncooperative.Footnote 39

To be sure, the power imbalance between the Qing and the treaty powers determined that Chinese legation ministers lacked military support to buttress their diplomatic claims. The cases managed by the legation therefore were mostly concerned with enforcing the Qing's existing treaty rights and sovereignty, arguing for the fair treatment of China or Chinese subjects according to international law, and reducing misunderstanding between the two governments. In fulfilling these functions, the legation was in regular communication with the Zongli Yamen and provincial officials; they also consulted their own legal advisers, corresponded with Robert Hart, the inspector general of the Maritime Customs, and relied on their personal relationship with the undersecretaries of the Foreign Office to gain valuable insights into the shifting winds of British foreign policy. It became an office where information gathered from a wide range of sources was consolidated and channelled into effective diplomatic and legal claims.

The ambition, talent, and personal networks of the Qing minister also influenced how often legations took over the responsibility of diplomatic representation. An overview of a 30-year period from the inception of the Qing legation shows that, during the tenures of Guo Songtao (1876–78), Zeng Jize (1879–86), and Xue Fucheng (1890–94), the office managed a greater number of complex and high-stakes cases. On the other hand, during the tenures of Liu Ruifen (1896–90), Gong Zhaoyuan (1894–97), and Luo Fenglu (1897–1902), the Qing legation often served as a bridge for passing messages between the British Foreign Office and domestic authorities.Footnote 40 Macartney undoubtedly played a key role in maintaining the diplomatic function of the legation and advising this sequence of ministers, but it would be an exaggeration to say that he was the only reason for the success of the legation.Footnote 41 Despite the fact that he served as the English secretary throughout this period, the effect of his work varied significantly, depending on the minister.Footnote 42 The Chinese minister's official network and personal views were crucial in rallying domestic support for the legation's policies.

Due to the unevenness of the minister's performance and their varying relationship with the Zongli Yamen, the legation was not always entrusted with important diplomatic negotiations and the result of legation activism was not always successful. Many of its functions during the tenures of Liu Ruifen and Gong Zhaoyuan, such as the bestowals of the Orders of the Double Dragon on foreigners and the transmission of telegrams between heads of state on important occasions, appear more ceremonial than diplomatic. But even these were important symbolic language signalling China's status of inclusion into the comity of nations. These gestures, ritual, and mimicry, as Susanne Schattenberg has observed, performed the task of ‘ensuring security of expectations and protecting the dignity and honor of both countries’.Footnote 43 The existence of this London channel of communication between the two countries created, for the first time, a legal representation of China on a distant land in the mother tongue of European diplomats. This legal representation allowed the Qing government to bypass obstreperous foreign diplomats and colonial officials to reach their home governments directly; more importantly, it gave a diplomatic voice to the Qing government in the linguistic complexes native to these foreign powers. In all these cases, the geographical location, diplomatic expertise, and bilingual capacity of the legation empowered it to exercise a degree of independent agency unimaginable in the pre-legation era.

Fugitive offenders and extradition from Hong Kong

The rendition of fugitives who had escaped to foreign colonies or territories exemplifies a class of diplomatic and legal battles where China's inclusion and exclusion in international law were fought. In this section, I examine the legation's representation of the Qing in the rendition of 13 fugitives from the British colony of Hong Kong to the nearby province of Canton.Footnote 44 By reconstructing one of the most prolonged controversies it engaged in (1881–85), I use the case to show the possibilities, constraints, and inner workings of the legation's diplomatic representation. To the extent that extradition is both a diplomatic and a legal question, the case also shows how the legation upheld the Qing's judicial sovereignty in its support of the Canton government's request for Chinese offenders who had committed criminal offences in China and subsequently fled to Hong Kong. Although the legation's defence of the Qing's judicial sovereignty in this case was not successful, in the process of articulating China's rights and status, the legation's correspondence with the British Foreign Office revealed the loopholes, prejudices, and contradictions within Britain's extradition regime. It also opens up further avenues for re-examining the legation's detention of Sun Yat-sen in 1896 in the context of its ongoing efforts to assert the Qing's sovereign rights to bring fugitives back to China for trial.

On 22 November 1880, three members of the Yang family, natives of the Guishan County in Guangdong Province, were gunned down by a group of their distant relatives (also surnamed Yang) numbering about 20.Footnote 45 The magistrate of Guishan examined the bodies, held an inquest, and issued an order to apprehend the group of suspects, who had escaped into Hong Kong. The family of the deceased tracked down the group of 13 fugitives and requested the Hong Kong police to have them arrested and detained.Footnote 46

The legal basis on the extradition of Chinese fugitives was laid out in Article 21 of the Sino-British Treaty of Tianjin:

If criminals, subjects of China, shall take refuge in Hongkong, or on board the British ships there, they shall, upon due requisition by the Chinese authorities, be searched for, and, on proof of their guilt, be delivered up. In like manner, if Chinese offenders take refuge in the houses or on board the vessels of British subjects at the open Ports, they shall not be harbored or concealed, but shall be delivered up, on due requisition by the Chinese authorities, addressed to the British consul.

As Ivan Lee has argued, between 1843 and 1873, the colonial authority of Hong Kong generally resorted to the practice of ‘justice on the cheap’, giving up Chinese fugitives to the Qing authority when prima facie evidence of guilt could be established against the prisoners. This liberal attitude towards rendition was largely due to the resource limitation of the Hong Kong judicial system and the belief held by British colonial authority that ‘many punishments in English law were impractical and ineffective’ for Chinese offenders.Footnote 47

From the 1860s, periodic complaints about the vague provision of Article 21 could be heard in the press and colonial correspondence. When alarming reports about China's use of judicial torture on surrendered criminals in the mid-1860s emerged, the Foreign Office examined into the issue and held a series of meetings with the Zongli Yamen. It was hastily agreed, by diplomats on both sides eager to continue the practice of extradition, that a guarantee not to use torture by the local government in China would meet the satisfaction of the colonial government.Footnote 48 Yet, as the British Foreign Office acknowledged, even though the Canton authority had always promised not to use torture on the surrendered fugitives, they had no legal obligation to fulfil such promises.

Following the procedure of extradition as agreed upon in Article 21 of the Treaty of Tianjin, Governor General Zhang Shusheng wrote to the British Consul in Canton, Archer Rotch Hewlett, to request that the governor of Hong Kong, Pope Hennessy (1877–82), surrender the 13 captives, promising not to use torture on them.Footnote 49 While Consul Hewlett complied with Zhang's request, he registered a private objection in his letter to the governor of Hong Kong against extradition. Citing rumours that he had heard that the previous governor general, Liu Kunyi, had broken his promise not to use torture in 1879, Hewlett could not ‘for one moment believe that it will ever be given effect to’.Footnote 50 Governor Hennessy contested the consul's characterization of the Canton authority and claimed that he was unable to find ‘a single instance in which a written promise given by the Viceroy of Canton or by the Chinese Government to any of my predecessors had been broken’.Footnote 51 He believed that Consul Hewlett was misled in his characterization of the governor general of Liangguang.

In the early months of 1881, the deadlocked case was forwarded to higher levels in both governments, the Foreign Office and the Zongli Yamen. On the British side, foreign minister Lord Granville received the affirmation from Consul Hewlett of his belief that all 13 fugitives, if extradited, would be punished by a form of slow and painful execution known as ‘death by a thousand cuts’.Footnote 52 To the Qing court, however, the matter was a hindrance to the exercise of local justice in Guangdong, not primarily of a diplomatic nature.

Following memorialization of the provincial judge, the Qing court instructed the Zongli Yamen to pass the case to Zeng Jize, the Qing's resident minister in London, who would request that the British government abide by its treaty obligation and surrender the prisoners. The legation was supported by frequent telegraphic transmission with the Zongli Yamen and the Canton authorities, which permitted the office to legally represent the Zongli Yamen and respond to any inquiries from the British government promptly and decisively.Footnote 53

On 30 July 1881, the legation's English Secretary Halliday Macartney relayed a message from minister Zeng Jize stating that the Zongli Yamen enabled the legation to deny formally ‘in the name of his government’ that any torture had been inflicted on fugitives previously surrendered by the Hong Kong government in violation of the undertaking given by the Viceroy of Canton.Footnote 54 Three days later, Zeng visited Under Secretary Dilke and explained that the fugitives were charged not with parricide, but with the murder of distant relatives, and assured the Foreign Office that punishment by lingering death was not applicable by Chinese law to the crimes that the 13 were charged with, since they were only distantly related to the deceased.Footnote 55 He also made a tentative suggestion on the appointment of a Chinese consul in Hong Kong ‘with the power (in minor cases) to deal with criminals surrendered to him by summary trial and punishment’.Footnote 56 Finally, Zeng provided the local context for the urgency of a prompt resolution: numerous witnesses had been detained in custody pending the trial and the delay had caused suffering and agitation.

The legation's explanations led the under secretary of the Foreign Office to telegraph the Hong Kong governor requesting the immediate surrender of the fugitives provided that the Viceroy of Canton could give a written assurance not to use torture.Footnote 57 But, due to the British Minister Thomas Wade's strong objection to the validity of these assurances, the release of the prisoners was delayed by over half a year. This long delay gave the fugitives months to rally legal and political support within the colony, and they were eventually released on a writ of habeas corpus. Governor Hennessy, clearly taken aback by the decision, claimed personal responsibility for failing to detect the legal informalities and called it a ‘miscarriage of justice’.Footnote 58

Although the Foreign Office considered the case closed by the end of 1882, it was far from being settled to the Qing government's satisfaction. Following an imperial edict, Zeng's legation lodged a formal complaint on 22 July 1882 with the Foreign Office. It reminded Lord Granville of Zeng's conversation with Under Secretary Dilke the previous year, in which the latter had accepted Zeng's explanations and telegraphed Hong Kong ordering the immediate surrender of the fugitives. The letter also challenged the Supreme Court of Hong Kong's decision to release the prisoners on a writ of habeas corpus, arguing instead that the evidence provided by the Hong Kong magistrate against the prisoners was sufficient for extradition purposes. In a concluding statement, the communication returned to the letter of the Treaty of Tianjin, protested the introduction of conditions extraneous to the treaty, and drew the Foreign Office's attention to the ‘constant miscarriage of justice’ this had led to.Footnote 59

The legation's protests, together with the sympathies of the Foreign Office, played no small part in the colonial authority's re-arresting the 13 fugitives in 1883.Footnote 60 The attorney general of Hong Kong, having examined the documents a second time, confirmed that there was a ‘prima facie case’ against 11 of the 13 fugitives and that there was no ‘legal impediment to their being surrendered to the Chinese authorities under Article 21 of the Tianjin Treaty’. He also cited Zeng's letter to the Foreign Office (which the latter had copied to all offices involved) that ‘the security and good order of’ China rendered it ‘desirable that crime should not go unpunished’ in Hong Kong, as it was feared by the Hong Kong community that, without stringent enforcement of extradition rules, the island might become ‘a haven for the disorderly classes’. He acknowledged, however, a serious complicating factor introduced by the Roman Catholic Church of Hong Kong, led by Bishop Monsignor Raimondi, and admitted that the Executive Council was unable to make a final decision on the case. The ball was back in the Foreign Office's court.Footnote 61

The fugitives’ ability to rally the Roman Catholic Church's support to establish their credibility in the court of law must be understood in the particular context of colonial Hong Kong's judicial system. As Christopher Munn has shown, judicial opinions in colonial Hong Kong were often influenced by the perceived respectability of the defendant, especially on ‘whom he could produce to vouch for his credibility’.Footnote 62 The unexpected involvement of the Church, which had played no part in the case prior to this, proved the decisive factor in shifting judicial opinions regarding the case. Led by Timoleon Raimondi, the Vicar Apostolic of Hong Kong, the Church employed its network of clergy in Canton and its connection to the London-based Aborigines Protection Society to mobilize a campaign against the surrender of the 11 fugitives. The Bishop insisted that the men were falsely accused by powerful local magnates. His testimony contained no direct evidence based on his knowledge about the prisoners, but an appeal to what he believed to be the common knowledge about Chinese culture: ‘everyone possessing any knowledge of the Chinese of the Southern provinces … knows there is hardly another place where the old saying might is right’, where ‘the weaker party have either to submit to their oppressors or to meet with almost certain death’.Footnote 63 According to this logic, the very fact that the fugitives were under persecution proved their innocence.

Under renewed pressure from the Colonial Office, the Hong Kong governor, Sir George Bowen, ordered the case reopened. It soon attracted public opinion and, in April 1884, a series of letters to the editor of North-China Herald by a certain ‘Fiat Justitia’ characterized the Qing's request for rendition as nothing less than anti-Christian persecution. Most significantly, the letters called attention to a recent book by Dr Erskine Holland, Professor of International Law and Diplomacy at Oxford, in which he argued that ‘international law can subsist only between states which sufficiently resemble each other’ and should not be applied to a country that ‘glories in repudiating [natural precepts of the human race] by considering all people outside “the four seas” barbarians’.Footnote 64

Unable to decide, the Foreign Office referred the case to the law officers of the Crown. Their questions were given in three parts: (1) whether the law officers considered the proof of guilt to be sufficient to render extradition; (2) whether the Hong Kong government would be justified in refusing the extradition; (3) whether the British government should be satisfied with the Chinese government's promise in writing that no torture would be inflicted. In their response on 18 September 1884, the three law officers of the Crown, Henry James, Farrer Herschell, and J. Parker Deane, stated with some reluctance that ‘Her Majesty's Government cannot of strict right refuse to deliver a criminal on the ground that there is reason for suspecting that torture will be applied to such criminal’. In what seems to be a statement leaning towards extradition, the law officers emphasized that the Hong Kong government ‘should be instructed to consider the best practical means of maintaining communication with prisoners who have been rendered so as to ascertain if torture has or has not been inflicted’.Footnote 65 With regard to the 11 fugitives, however, the law officers did not ‘feel competent to review the opinion’ of the Executive Council of Hong Kong that the prisoners should be released.

The law officers’ opinions, ambiguous and guarded as they were, gave the Foreign Office enough confidence that they could order the Hong Kong government to release the 11 prisoners. This decision was a compromise, informed as much by legal advice of the Law Office as by following a path of least resistance around the Hong Kong government and the Roman Catholic Church. By agreeing to revert back to the principle of accepting extradition requests upon a written promise by the Chinese authority, this decision essentially preserved the status quo for future extradition cases. The case of the 11 prisoners would be treated as an exception and they were released not because of the Canton government's use of judicial torture, but because the governor of Hong Kong had reopened the case, retroactively accepted the missionaries’ testimonies, and determined that there was not enough evidence for extradition.

We might observe that, at this point, the legation had won its most important battle: the initial challenge to the principle of extradition upon the Chinese government's presentation of prima facie evidence, as well as its renunciation of judicial torture, was essentially dead after this point. The credibility of the Chinese government was no longer an issue. Nevertheless, the discharge of the 11 fugitives failed to satisfy the Qing legation and, on 8 December 1884, Zeng persisted in his request to rearrest of the fugitives.Footnote 66 Zeng's first argument was based on his interpretation of proper judicial procedure. He determined that ‘after the Judicial Authorities had decided that the evidence of criminality was such as to justify the extradition of the prisoners’, the executive branch of the government was not empowered to overrule that decision. Second, even if the governor had such power to overrule, the administrative authority could not ‘legally receive fresh evidence … without the Chinese Government being given an opportunity of rebutting it by Counsel’. Third, Zeng argued that the ‘proof of guilt’ contained in the Treaty of Tianjin was not ‘intended to be taken in … an absolute sense, or to signify other than that presumptive proof of guilt—which is usually required in Extradition cases’. To support his claims, Zeng cited Ordinance II of 1850 and the Imperial Extradition Acts of 1870 to argue that, once the magistrate of Hong Kong had found probable cause, the decision of extradition was final and ‘it is not given to the Executive, or to any Authority whatever, either to review the decision of the Magistrate, or … to refuse to issue the Warrant of Surrender’, except in the case of political crimes.Footnote 67

Zeng's final point addressed the belief held by Dr Erskine Holland and other leading jurists regarding the barbarity of the Chinese penal code and that China should be excluded from the concord of civilized nations. His argument holds no legal weight (and is therefore never responded to by the Foreign Office), but it is worth quoting in length because it strikes at the heart of Western representations of Chinese law as a barbaric aberration from the standard of civilization—an interpretation that British diplomats and jurists had used to justify the exclusion of China from international law.

Her Majesty's Government need be under no apprehension of their ever being asked by the imperial government to do anything inconsistent with the dictates of humanity—that sentiment which, in different ages, sometimes comparatively recently, has manifested itself in such different ways that the humanity of today has often become the barbarism of the morrow. It is not long since a criminal code, not unlike that of China, was considered not inconsistent with the dictates of humanity in some of the most advanced European countries and perhaps it will not be long before capital punishment, which they still consider to be indispensable, will be viewed with the same aversion as some of those punishments contained in the Criminal Code of China but that are so rarely inflicted that the imperial government has made no difficulty in giving a guarantee that they shall not be applied to prisoners extradited from Hong Kong, for whom, in the treaty, there is no stipulation.

The Foreign Office consulted the law officers of the Crown about the issues raised by Zeng's letter on two separate occasions, specifically regarding (1) whether the governor of Hong Kong should have any discretionary power over the judicial opinion of the magistrate according to the Colonial Ordinances of 1850 and 1871; and (2) whether the ‘proof of guilt’ that the Treaty of Tianjin specified as the condition for extradition should be probable cause or whether, as claimed by the Executive Council of Hong Kong, it should be sufficient to support a final conviction.

In their final response, the law officers appeared split in their opinions. Richard E. Webster and J. E. Gorst cautiously agreed with Qing legation on each of these issues, expressing ‘with great reluctance’ their opinion that ‘the Chinese Government have done what is requisite to entitle them under the Treaty of Tien-tsin to surrender the person in question’. On the other hand, J. Parker Deane stressed the governor of Hong Kong's ultimate authority over the magistrate.Footnote 68 In the end, the Foreign Office sided with Deane and refused the legation's request to rearrest the fugitives. They reasoned that, since the British Extradition Act of 1870 was never adopted for China, Britain was not obligated to apply principles contained in the Act in dealing with China. According to Article 21 of the Treaty of Tianjin, the only legal document governing extradition cases, the governor of Hong Kong had the ultimate authority over extradition cases irrespective of the magistrate's ruling.

The controversy and dissatisfaction surrounding the case contributed to the joint efforts between the Foreign Office and the Qing legation to exchange their views on formulating an extradition treaty. In 1884 and 1885, Halliday Macartney and Julian Pauncefote, the under secretary of state for Foreign Affairs, after preliminary discussions, drafted an extradition treaty based on the model of the British–Spanish extradition treaty of 1878.Footnote 69 However, upon Zeng's leaving England in 1886, his successor, Liu Ruifen, did not follow up on the negotiation and the matter was quietly dropped. In response to Lord Salisbury's request to continue the negotiation, Liu replied that he needed to ask the Zongli Yamen first, but gave no follow-up correspondence on this matter.Footnote 70 We can imagine that, if Zeng's successor had been one who matched his vision and connection, these discussions might have ultimately led to the signing of an extradition treaty.

The legation's representation of the case was not ultimately successful, but we cannot ignore its effects in counter-balancing the influence of British diplomats and colonial officials in Hong Kong. It educated the Foreign Office on the discrepancy between the Chinese government's point of view and British diplomats’ representations of China. These communications rested upon a level of trust and mutual understanding gradually established by the legation's past engagements with the Foreign Office. Both the Qing legation and the British government understood that the continuation of the existing extradition practice was most convenient to both China and Hong Kong. For the latter, it would keep away from the colony an influx of troublemakers or fugitives whom it would otherwise either accept or expel. On multiple occasions, and especially on the use of torture, the Foreign Office appeared sympathetic to the legation's views. Despite the release of the 11 prisoners, the Qing government was able to continue receiving surrendered fugitives with a written guarantee not to use torture. To the extent that the legation failed to convince the Foreign Office that China deserved equal treatment under Britain's Extradition Acts of 1870, the legation's representation of the Qing as a sovereign nation state was both enabled and circumscribed by the regime of unequal treaties over which it exerted limited interpretive authority.

Representing China during the Boxer Uprising

As the previous sections have shown, the independent agency of the legation in pursuing their diplomatic agenda largely depended on a successful collaboration between the resident Qing minister and Halliday Macartney, on the one hand, and the position and connection of the minister within the Qing officialdom, on the other. From 1894 onward, the legation was presided over by bureaucrats less politically ambitious and whose connections to the Zongli Yamen and the Qing court were much weaker, and Macartney, near retirement, contemplated a retreat from fulltime management of legation affairs. From 1896 to 1901, minister Luo Fenglu took over most of the legation's daily affairs. A former legation secretary and veteran of the Beiyang Navy, Luo was fully conversant in English, but held no civil-service-examination degrees and gained the position largely due to powerful patrons such as Li HongzhangFootnote 71:

In this context, the legation's connection to the Zongli Yamen and the Qing court weakened and its diplomatic role changed accordingly—it became a channel of communication between the various domestic authorities in China and the British Foreign Office. Although these changes have been seen by some scholars as evidence of the immaturity of the Qing's diplomatic bureaucracy, I argue that they reveal the versatility, indispensability, and functional independence of the legation. In this section, we shall examine how the legation performed its mediating role during the diplomatic crisis of 1900.

The first clear indication of legation involvement in the Boxer crisis was its letter to the Foreign Office on 10 January 1900 on the killing of British missionary, S. P. Brooks, on 31 December 1899. The legation expressed the ‘profound regret at the lamentable occurrence’ by the emperor, the empress dowager, and the Zongli Yamen, and informed the Foreign Office of the steps they followed to punish the perpetrators and the local officials in charge.Footnote 72 From early 1900 to the height of the conflict in the summer months, the legation carefully skirted the hawkish opinions of the imperial court and followed the principle of civility and reason in its exchanges with the Foreign Office. Although this rational image of China was undermined by a disproportionally large volume of letters, reports, and cartoons by foreigners depicting the Chinese to a contrary effect, the Qing London legation, as well as other legations stationed in all major powers, continued to function as usual. Their diplomatic standing was not compromised by the Qing court's declaration of war against the powers and their prerogative in representing the Chinese government was never revoked. They became messengers for provincial or metropolitan officials who disagreed with the Qing court's declaration of war upon foreign powers, including Li Hongzhang (governor general of Liangguang), Liu Kunyi (governor general of Liangjiang), Wang Zhichun (governor of Anhui), and Yuan Shikai (governor of Shandong).Footnote 73

The London legation often invited the British Foreign Office to weigh in on the decisions of British consuls that Qing officials disagreed with, which might have played no small part in keeping the latter from deploying military and naval forces in the Yangzi region.Footnote 74 For instance, on 19 June, the legation forwarded a telegram from Zhang Zhidong, governor general of Huguang, in response to the British Consul's ‘offer of assistance’ in preserving order in the provinces. He promised London that the province had ‘very sufficient, well-equipped and well-disciplined Forces, on which they can implicitly depend; and these they will so dispose and employ as to give the fullest measure of protection to all residing with their respective jurisdictions, whether natives or foreigners and of whatever religion’.Footnote 75 In response, Lord Salisbury issued an explicit instruction to British diplomats in China to withhold military deployment and this delay bought valuable time for negotiation between British consuls and Qing provincial authorities.Footnote 76 On 26 June, these talks resulted in the famous nine-point neutrality pact wherein the responsibility for protecting foreign residents was divided up between the treaty powers (responsible only for Shanghai) and the provincial governments (responsible for the rest of the Yangzi valley and other treaty ports); it also limited the movements of foreign ships of war on the Chinese coast.Footnote 77 Again, in early August, when Admiral Seymore proposed to Liu Kunyi, governor general of Liangjiang, to land an alarmingly large force of 2,000 troops in Shanghai, the latter petitioned through the London legation to have it reduced to several hundred, citing ‘a great apprehension’ that the news had excited in Chinese merchants and people. The Foreign Office approved Liu's request and ordered the landing force in Shanghai to be reduced to several hundred and, according to Liu's report: ‘Rumors have been stopped. The people have been pacified.’Footnote 78

How each of the Qing's legations in England, Germany, France, Japan, and the United States of America aligned themselves with the intricate networks of political patronage during the Boxer Uprising is beyond the scope of this article but, if we take the London legation's communications as a significance case, it seems clear that legations had a certain filtering effect in transmitting proclamations from the imperial government to the foreign ministries of the treaty powers. Among the letters and telegrams from the London legation to the British Foreign Office in 1900, we find no trace of the bellicose edicts issued from the pro-Boxer empress dowager or imperial clansmen. Instead, they featured voices of moderation, compromise, and regret, depicting the Qing court as being staunchly against the Boxers and doing everything within its capacity to bring order back to North China.

The legations in London and other foreign capitals were not only instrumental in linking anti-Boxer officials and foreign governments; for the months of July and August, they were the only linkage between besieged foreign communities in North China and their home governments after the Boxers cut telegraphic lines in Tianjin in July. In early August, the Zongli Yamen, whose telegraphic lines remained intact, refused to deliver coded telegrams from foreign governments to the besieged foreigners or vice versa.Footnote 79 The legations’ telegraphic connection to Shanghai (safe under the treaty powers’ protection) became the only site where information about the safety of foreigners in the North could be transmitted to their home governments.Footnote 80 As the allied forces entered Beijing in late August and the imperial family fled to Xi'an, the London legation forwarded many telegrams expressing the provincial officials’ collective desire to immediately cease hostilities and convene for conference.Footnote 81 Since these telegrams were often addressed to all Qing resident diplomats in foreign capitals, we know that the London legation's pattern of communication applied to other legations as well.

In his analysis of British foreign policy during the Boxer Uprising, T. G. Otte described the Foreign Office's ‘sense of the constraints … on Britain's ability to deal with a crisis in China’ and, in particular, Lord Salisbury's ‘wait-and-see’ attitude and his failure to enunciate a clear foreign strategy to the frustration of the younger generation of diplomats.Footnote 82 It is possible to explain British foreign policy from the perspective of political personality and generational differences, but we should not discount the positive steps taken by Chinese officials and diplomats to influence and counterbalance the interests of foreign governments. The highly efficient Sino-British telegraphic network provided important perspectives that conditioned Salisbury's response to the Boxer crisis. On at least two separate occasions during the negotiation, the London legation obtained the Foreign Office's consent to retain the service of British diplomats whose views appeared in alignment with those of the Qing government.Footnote 83 It was through these telegrams mediated by the London legation that provincial officials articulated their own anti-Boxer stance, pledged to cooperate with foreign peacekeeping forces, and effectively sidelined the radicals around the Empress Dowager Cixi.

What does the legation's work during the Boxer Uprising tell us about how it represented China and, more importantly, how did its work of diplomatically representing the polity change the meaning of ‘Qing/China’? Until now, we have used ‘Qing’ and ‘China’ interchangeably. This loose pairing was adopted by Qing diplomats themselves as they glided between ‘imperial government’ and ‘China’ in their written communications. The fact that the regime of collaboration between the Qing government and foreign governments continued even when the court was openly at war with treaty powers suggests a disassociation between the legal concept of ‘China’ and the Manchu ruling house. This disassociation was made possible partly by the sinews of political connections that the legation had cultivated with provincial officials and foreign governments, and partly by its parallel status to the Zongli Yamen. The fact that the Qing minister was authorized to memorialize to the throne directly, and that it could cooperate with provincial authorities on foreign affairs without the interference of the Zongli Yamen and the Grand Council, made it possible for the provincial officials to step in and speak for the ‘imperial government’ when diplomatic relationship between the Qing court and foreign powers broke down.

Throughout the Boxer Uprising, the legation shielded the British Foreign Office from receiving messages of open bellicosity and promulgated an alternative set of Qing policies that emphasized restraint, mutual respect, and swift restoration of peace. To be sure, messages from the legation were only one of many channels of information available to the Foreign Office and we should by no means assume that Lord Salisbury trusted the Qing minister in London more than British diplomats. The gains made by the legation were small compared to the calamitous effects of the Boxer Protocol. But the consistency of the legation's representation provided assurance to treaty powers that their relationships with local Chinese interests were more enduring than the dynasty itself and collaboration continued with a different group—the provincial officials—rather than the imperial court.

Finally, we see that, in the summer months of 1900, the contrast between the two images of China—one transmitted from foreign diplomats and the other represented by Qing diplomats—reached a glaring degree. It is futile to ask which one is a more ‘truthful’ representation, but it might be possible to think of the former as representative of the ‘Qing dynasty’ and the latter as the legal abstract ‘China’ constructed by treaties and international law. While these meanings coexisted prior to 1900, the latter understanding of China would outlast and ultimately replace the former sense.Footnote 84

Conclusion

The Qing legation in London and its overseas staff had many double characteristics that defy simple categorization. They were integrated into both the European diplomatic order and the Qing's imperial bureaucracy. They were under the management of the Zongli Yamen and yet stood parallel to that office before the throne. They managed complex extradition cases with a keen understanding of treaty rights and international law. Their work in defending the Qing's judicial sovereignty over Chinese fugitives resembles that of modern lawyers but, when they applied these skills to deport political fugitives such as Sun Yat-sen, they suddenly look like the tendril of a despotic regime. Overall, their work in upholding the sovereignty and treaty rights of the Qing was both indispensable and largely invisible to most domestic officials because of their geographical distance and adoption of foreign languages as their primary mode of communication.

The invisibility of the Qing legation diminished for a brief period in the early 1890s when minister Xue Fucheng published nearly all legation communications that the legation produced under his supervision: memorials, diplomatic notes, his own lengthy journals, and letters to the Zongli Yamen, provincial officials, and consulates. The Qing's overseas work suddenly became intelligible to the officials and literati at large. This revelation of the inner workings of the legation's diplomatic representation, along with the minister's thoughtful synthesis of Western learning, became a major source of inspiration for scholars of many persuasions, ranging from treaty-port intellectuals such as Zheng Guanying and Wang Tao to New Text Confucianists such as Liao Ping and Kang Youwei.Footnote 85 The idea of establishing multiple semi-sovereign ‘Chinese colonies’ overseas, which Xue had first developed as a theory to gain domestic support for consulate expansion, likely inspired Kang Youwei to briefly champion the colonialization of Brazil in order to establish a ‘new China’.Footnote 86

The London legation's work helped bring about the post-1895 intellectual ferment so well known to Chinese historians, but its multifaceted roles have seldom been acknowledged due to the Qing's information control, archival dislocation, and the legation's bad publicity following their failed attempts at bringing judicial sovereignty to overseas fugitives. This article does not intend to exaggerate the political or diplomatic function of the legation. Rather, the significance of the legation's diplomatic representation lies in how it created and disseminated a new meaning for understanding ‘China’ as a legal entity independent from the imperial dynasty. The degree of this notional separation was implicit in many of the legation's communications prior to 1900, but became most apparent during the Boxer Uprising, when the dynasty's rulers fled the capital and provincial officials used the legation to bypass the Empress Dowager Cixi and upheld a different set of policies in the name of the imperial government. Without the physical site it occupied and the network of Sino-Western offices it straddled, the messages from China might never have reached foreign governments, and the expedition forces might have behaved even more recklessly and presented a fait accompli to the governments of the treaty powers as in the case of the First Opium War. Overall, the legation's diplomatic representation in the security of foreign capitals during the last 40 years of the Qing had the effect of recreating China as a legitimate member of the international system aspiring to the status of equality with other powers. Even though its claims were not always accepted by foreign governments for a variety of reasons, these discursive attempts were important legal precedents for Chinese diplomats of a later time.